Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol.05 No.14(2015), Article ID:61607,5 pages

10.4236/ojog.2015.514110

Obstetric Complications Due to Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) at N’Djamena Mother and Child Hospital (Chad)

Lhagadang Foumsou1*, Richard Norbert Nglalé2, Jeanne Fouedjio3, Gédéon Ndakmissou1, Bray Madoué Gabkika1, Sadjoli Damthéou1, Philip Njotang Nana3, Abdoulaye Sépou2

1Department of Gynecolgy and Obstetric, Faculty of Human Health Sciences, University of N’Djamena, N’Djamena, Chad

2Department of Gynecolgy and Obstetric, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Bangui, Bangui, Central African Republic

3Department of Gynecolgy and Obsteric, Faculty of Biomedical Sciences and Medicine, University of Yaounde I, Yaounde, Cameroon

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

Received 22 September 2015; accepted 27 November 2015; published 30 November 2015

ABSTRACT

Background: Female genital mutilation (FGM) or female circumcision is all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genital organ or other injuries to the female genital organ whether for cultural or any other non-therapeutic reasons. Female genital mutilation causes numerous complications. Four in such cases multiplies obstetric complications. The aim of this study was to identify obstetric complications due to FGM. Patients and Material: We conducted a comparative prospective case-control study for three months, from January 1st to March 31st, 2014 in the maternity of N’Djamena Mother and Child. It focused on identifying neonatal and/or maternal complications during childbirth due to FGM. The study population consisted of pregnant women at term admitted for delivery labor. All parturients had to present the same sociodemographic and clinical profiles. A history of FGM was the main distinguishing criterion. Results: During the study period, we recorded 312 births to women with genital mutilation, among 1905 deliveries, representing a prevalence of 16.4%. One hundred ninety-one cases of circumcised women responding to the inclusion criteria were selected. Most of these women were between the ages of 20 and 29. The extreme age group was 15 and 39 (with a mean of 24.5 years). FGM was significant in age group over 20 years (Khi2 = 10.8; OR = 2.6 [1.4 - 4.9]; P = 0.001). The type II of FGM which removed a part of the clitoris and the adjacent labia minora represented 64.40% patients in the group of women with FGM. Perinea laceration was the frequent maternal complication among parturient with FGM (Khi2 = 9.8; OR = 2.2 [1.4 to 3.6]; P = 0.0007). FGM type III was associated with a high proportion of maternal complication (Khi2 = 11.2; OR = 7.3 [1.97 - 31.6]; P = 0.0001). Still births were significantly higher in the group of parturient with FGM (11.5%, P = 0.015). Conclusion: Female genital mutilation is a common cultural practice in our country; it contributes to worsening maternal and fetal complications.

Keywords:

Female Genital Mutilation, Childbirth, Maternal-Fetal Complication, N’Djamena (Chad)

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines FGM as all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genital organ or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or any other non- therapeutic reasons [1] . They are practiced in 28 countries in the world affecting more than 140 million women and girls, causing the narrowing of the vaginal opening. Over 3 million women and girls are at risk each year [1] [2] . In these countries, national prevalence among women aged 15 years and older ranges from 0.6% (Uganda, 2006) to 97.9% (Somalia, 2006) [3] . However, prevalence can vary strikingly between different ethnic groups within a single country [3] .

In Chad, according to demographic and health surveys, 45% of women aged between 14 and 49 suffered from FGM [4] . Several international texts and conventions condemn and prohibit female genital mutilation and many approaches have been developed to fight against excision in the world [5] -[8] . Despite these measures, the practice of FGM, which has traditional and cultural bases, persists. Medically, there are obstetric complications due to excisions [2] [9] -[13] . Our aim was to identify obstetric complications during childbirth due to FGM in our department.

2. Patients and Methods

We conducted a comparative prospective case-control study for three months, from January 1st to March 31st, 2014 in the maternity of N’Djamena Mother and Child hospital. It focused on identifying neonatal and/or maternal complications during childbirth due to FGM. The study population consisted of pregnant women at term admitted for delivery labor. In particular, women to term with a single pregnancy (≥37 weeks), a live fetus in cephalic presentation, HU < 36 cm and who agreed to participate in the survey. These women had the same sociodemo-graphic and clinical profiles. A history of FGM was the main distinguishing criterion. Women in the following situations were excluded from the study: preterm delivery, multiple pregnancy, large fetus (birth weight ≥ 4000 grams), other than cephalic presentation, uterine scar, fetal death in utero.

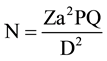

We defined prolonged expulsion duration if it lasted more than 1 hour. A newborn is considered alive if it has an APGAR score between 1 and 10 at the first minute. The sample size was calculated using Lorenz formula:

(where: N = acceptable sample size in each group [calculated value = 95.04]; a = level of

(where: N = acceptable sample size in each group [calculated value = 95.04]; a = level of

statistical significance; Za = normal distribution value = 1.96 for a = 0.05; P = FGM prevalence in Chad= 45%; Q = 1 − P; D = degree of accuracy = 10%).

The minimum acceptable sample size was 96 patients in each group. As soon as a woman suffering from FGM and in labor was admitted, the following two parturient hospitalized in the same unit, with similar sociodemographic and clinical profiles Such as the age, parity, term of pregnancy, type of presentation and the estimated fetal weight, and which had not undergone FGM was selected as witnesses. For matching reasons, we recruited 191 parturient for the group FGM against 382 parturient without FGM. The studied variables were epidemiological and clinical. The analysis was made using the EPI INFO 3.5.3 software. Comparisons were made using the statistical tests.

3. Results

Frequency: we had recorded 312 births to women with genital mutilation, of 1905 deliveries, which includes 1844 live births. The FGM prevalence compared to births is 16.4%.

Age: Age distribution of the patients varied between 15 and 39, mean 24.5 years in which more women were recorded in the age group 20 - 29. FGM was significant in age group over 20 years (Khi2 = 10.8; OR = 2.6 [1.4 - 4.9]; P = 0.001) (Table 1).

Marital status: Most of the women in both groups were married. Proportion of married women was higher in the group of parturient with FGM (Khi2 = 17.4; OR = 2.2 [1.5 to 3.1]; P = 0.00003) (Table 1).

Types of FGM: The Type II of FGM which removes a part of the clitoris and the adjacent labia minora represented more than half of patients in the group of women with FGM ( n = 123/191 i.e. 64.40%). The type I of FGM (which consist in the removal of a part or the totality of the clitoris): and type III of FGM (which consists in the removal of the clitoris, labia minora and labium majora) represented respectively 21.5% (n = 41/191) and 14.1% (n = 27/191).

Maternal complications: perinea laceration was the frequent maternal complication among parturient with FGM. (Khi2 = 9.8; OR = 2.2 [1.4 to 3.6]; P = 0.0007) (Table 2).

FGM type III was associated with a high proportion of maternal complication than the type I and II. (Khi2 = 11.2; OR = 7.3 [1.97- 31.6]; P = 0.0001).

Fetal complications: stillbirths was significantly higher in the group of parturient with FGM (11.5%, P = 0.015). Neonatal resuscitation was more performed in the group of parturient with FGM (P = 0.0032 and 0.001) (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 1. Age and marital status.

Table 2. Maternal complications.

Table 3. Complications according to type of FGM.

Table 4. Neonatal complications.

4. Discussion

We reported that 16.4% of parturient were circumcised. This proportion is lower than our national rate of FGM and previous data through the literature [11] -[13] . Factor like selection bias can explain these findings. Indeed only women in labor were included on this series.

The sociodemographic characteristics of both groups were identical. The mean age was 24.6 years. This is consistent with earlier surveys that reported an important prevalence of female genital mutilation among youth women [7] [14] - [16] .

The percentage of female circumcision was significantly lower in adolescents (P = 0.001). This reflects the reduction of this traditional practice among girls and might be explained by the intensity of the messages focusing on FGM complications. This reduction was even more significant because the study population consisted of urban women. As for marital status, the proportion of married women was significantly more important (P = 0.00032). Indeed, circumcised women have a higher chance to get married according to some Chadian traditions. Sepou et al. [12] noted that marriage is one of the reasons for this cultural practice. Apart bleeding which can cause maternal death, the most important consequence of FGM is vulvo-vaginal narrowing which depends on the type of mutilation.

More than half of the circumcised women (64.4%) had presents the Type II of FGM, followed by types I and III. These results are similar to those of Millogo [14] in 2006 in Burkina Faso. Ndiaye [15] in his survey reported a high proportion of Type I FGM. This difference can be explained by the variability of FGM, which is dependent on cultural practice and experience.

According to Carcopino [2] the severity of obstetric complications is proportional to the importance of initial mutilation.

Maternal complications noted during childbirth were: perinea tear, bleeding due to perinea tear, episiotomy practice for perinea tear prevention. These complications were more frequent in case of FGM type III.

Perinea tear remains the common complication of FGM through the literature [10] [12] [14] [16] [17] . Episiotomy was more practiced among circumcised women. This finding was not statistically significant. For preventive reason (perinea laceration), or aiming to reduce expulsive time, episiotomy is often practiced all case during labour. This correlation was confirmed by several authors [12] [14] [18] .

Prolonged expulsion is explained by the loss of perineal elasticity, the perineum becomes resistant due to perinea scar tissue fibrosis. Millogo in Burkina Faso [14] and Dolo in Mali [19] reported respectively that the risk of prolonged fetal expulsion is eight t and two times higher for circumcised women.

Newborns complications were dominated by prolonged expulsion. The proportion of stillbirths was statistically higher in newborns whose mothers were circumcised (P = 0.015). The proportion of alive newborns that clinical status need resuscitation was higher for excised mothers, with a statistically significant difference these neonatal complications were noted by several authors [12] [16] [18] . Ndiaye [15] on another survey observed a no significant association between FGM and neonatal death.

5. Conclusion

Female genital mutilations are common cultural practices in our society. They are responsible of maternal and neonatal complications such as perinea tears (the most frequent complication), extension of expulsion time, acute fetal distress needing neonatal resuscitation and neonatal death in extreme case. Sensitizations about obstetric complications linked with FGM are required to curb these practices.

Cite this paper

LhagadangFoumsou,Richard NorbertNglalé,JeanneFouedjio,GédéonNdakmissou,Bray MadouéGabkika,SadjoliDamthéou,Philip NjotangNana,AbdoulayeSépou, (2015) Obstetric Complications Due to Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) at N’Djamena Mother and Child Hospital (Chad). Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology,05,784-788. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2015.514110

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2006) Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome: WHO Collaborative Prospective Study in Six African Countries. Lancet, 367, 1835-1841.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3 - 2. Carcopino, X., Shojai, R. and Boubli, L. (2004) Female Genital Mutilation: General, Complications and Obstetric Management. Journal de Gynécologie, Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction, 33, 378-383.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0368-2315(04)96544-1 - 3. World Health Organization (2008) Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation: An Interagency Statement: OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM. WHO, Geneva, 41.

- 4. Ministry of Economy, Planning and Cooperation (2004) National Institute of Statistics, Economic and Demographic Studies (INSEED). Demographic and Health Survey, Chad, 432 p.

- 5. European Parliament (2009) Resolution of 24 March 2009 Combating Female Genital Mutilation Is in the EU 2008/2071 (INI).

- 6. Berg, R.C. and Denison, E. (2012) Interventions to Reduce the Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in African Countries. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 9.

- 7. Wuest, S., Raio, L., Wyssmueller, D., Mueller, M.D., Stadlmayr, W., Surbek, D.V. and Khun, A. (2009) Effects of Genital Mutilation Are Female Birth Outcomes in Switzerland. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116, 1204-1209.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02215.x - 8. UNICEF (2010) Legislative Reform to Supporting the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. 57.

- 9. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre (2010) The Dynamics of Social Change Reviews towards the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Five African Countries. Florence, Italy, 55 p.

- 10. Larsen, U. and Okonofua, F.E. (2002) Female Circumcision and Obstetric Complications. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 77, 255-265.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00028-0 - 11. Sepou, A., Nguémbi, E., Yanza, M.C., Kom, A., Mamadou, D., Ngbalé, R. and Nali, M.N. (2003) Obstetric Accidents Related to Motherhood Excisions of Bangui Community Hospital. Black Africa Medicine, 50, 155-158.

- 12. Sepou, A., Goddot, M., Ngbalé, R., Komayan Fangbilette, J.L. and Serdouma, E. (2009) Obstetric Complications of FGM in Bangui (Central). Black Africa Medicine, 56, 213-217.

- 13. Akotionga, M., Nikiema, A.P., Lankoandé, J., Testa, J. and Koné, B. (1998) FGM in Ouagadougou: Evolution and Epidemiology. Black Africa Medicine, 45, 485-490.

- 14. Millogo Traoré, F., Kaba, S.T.A., Thieba, B., Akotionga, M. and Lankaondé, J. (2007) Maternal and Fetal Prognosis during Childbirth in Women Excised. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 36, 393-398.

- 15. Ndiaye, P., Diongue, M., Faye, A., Drissa Ouedraogo, D. and Tal Dia, A. (2010) Female Genital Mutilation and Complications of Childbirth in the Province of Gourma (Burkina Faso). Public Health, 22, 563-570.

- 16. Kapla, A., Forbes, M., Bonhoure, I., Utzet, M., Marin, M., Manneh, M. and Ceesay, H. (2013) Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in the Gambia: Long-Term Health Consequences and Complications during Delivery and for the Newborn. International Journal of Women’s Health, 5, 323-331.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S42064 - 17. Berg, R.C. and Vigdis, U. (2013) Obstetric of Female Genital Mutilation Consequences/Cutting. A Systematic Meta-Analysis and Review. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2013, Article: ID 496564.

- 18. Hakim, L. (2001) Impact of Female Genital Mutilation on Maternal and Neonatal Outcome during Parturition. East African Medical Journal, 78, 255-258.

- 19. Dolo, A., Traoré, M., Diallo Diabata, F.S. and Diarra, I.N. (2001) Mounkoro Childbirth Excised in Women: Maternal Prognosis-Fetal. SAGO Journal, 2, 22-26.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.