Open Journal of Psychiatry

Vol.3 No.2A(2013), Article ID:29762,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ojpsych.2013.32A003

Cognitive coping strategies, emotional distress and quality of life in mothers of children with ASD and ADHD—A comparative study in a Romanian population sample

![]()

1Department of Neuroscience, Psychiatry and Pediatric Psychiatry, “IuliuHatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, ClujNapoca, Romania

2Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, “Babes Bolyai” University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Email: *elenepredescu@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2013 Elena Predescu, Roxana Şipoş. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 27 February 2013; revised 29 March 2013; accepted 10 April 2013

Keywords: Quality of Life; Emotional Distress; Cognitive Coping; ASD; ADHD

ABSTRACT

The Quality of Life (QoL) represents a dimension of the overall status and of the wellbeing that might be influenced by various factors. Mothers’ emotional and behavioral reactions, when having a child with diagnosis of mental disorder, are different depending on the emotional distress and cognitive coping strategies used. The aim of this study was to assess the cognitive coping strategies, emotional distress and the relationship between them and the quality of life in mothers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) compared to mothers of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD). Data were collected from 114 mothers of children with diagnosis of ASD or ADHD. Different psychological measurements have been used in order to assess the quality of life (Family Quality of Life Survey) cognitive coping strategies (Cognitive-Emotional Regulation Questionnaire) and emotional distress (Profile of Affective Distress) of the parents. For QOL and emotional distress, we didn’t find significant differences between the two groups. The coping strategies of the mothers of children with ASD that significantly correlated with the overall assessment of the family quality were: positive refocusing, positive reevaluation and catastrophizing. The results suggest that the use of adaptive coping strategies correlates with a higher family quality of life, while for the maladaptive ones, the relationship is reversed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Due to their prevalence explosion and major implications at the individual, family and social levels [1,2], autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are among the most studied neurodevelopmental disorders [3,4]. ASD and ADHD are both chronic mental disorder with early onset in childhood, but they are clinical entities with different evolution and intervention possibilities. The recovery process requires significant human and material resources for both disorders. Quality of life (QOL) is a philosophically derived concept. In recent years, QOL is increasingly cited in medicine, as diagnosis or treatment gold standard [5]. Therefore, the concept was also adopted in pediatric psychiatry and it is used in both individualized clinical assessment and monitoring the effectiveness of various psychological or pharmacological interventions. QOL can be conceptualized based on the following principles: is multidimensional, being influenced by personal and environmental factors and the interaction between them; has the same basic components for all individuals; is both subjective and objective and is improved by self-determination, resources, purpose in life and sense of belonging [6,7]. Parents’ adjustment to child diagnosis of ASD can be quantified by the accurate assessment and identification of the factors described above. Thus, interventions addressed to parents should focus primarily on the quality of life improvement [5].

The impact of raising a child with ASD on parents or main caregivers’ quality of life is not yet fully understood. Most studies described various aspects of parents and caregivers’ quality of life compared to the general population. The factors identified as influencing the quality of life are linked to child’s pathology, parents’ psychological characteristics and social environment [8-10]. Quality of life was not significantly associated with the diagnosis of ASD or child intellectual abilities, but was significantly influenced by his internalizing/externalizing problems, stereotyped behaviors, social skills or adaptive behavior [8]. A lower quality of life was associated with the child’s functioning impairment, the social support received and the use of non-adaptive coping mechanisms [9] or dysfunctional parenting styles [10]. Parents of children with ASD reported more family problems and are at a higher risk for developing physical or psychological problems [11]. Parental stress may have a negative impact on the effectiveness of different educational interventions at cognitive and behavioral level [12-14]. However, the results of the studies regarding the topic of quality of life of families with ASD children are rather inconclusive and further investigations are needed. In general, studies were conducted on small samples and used different instruments for quality of life assessment, which makes it difficult to replicate the procedure on other groups of interest. Another possible confusing aspect is the combination between different levels of analyses, such as: individual, familial or environmental factors. One factor that can significantly influence the quality of life is the distress perceived by the parents. On the other way, the perceived distress is determined by theirs cognitive coping strategies.

Garnefski et al. (2001) introduced the concept of cognitive emotion regulation which refers to the assumption that thinking and acting are different processes and cognitive strategies which are separate from behavioral strategies [15]. For ASD, there are only a few studies on cognitive coping strategies used by parents, despite the evidences regarding the direct connection between them and the caregiver adjustment to the chronic diagnosis situation [16,17]. Parents of children with ASD use both adaptative and maladaptative strategies [18]. The maladaptive strategies include self-blaming, escape/avoidance, withdrawal, and helplessness. In studies, they correlate with low positive emotions [19-21]. Among the adaptive strategies, which predict high levels of positive emotions are: problem focused, social support, positive reframing, emotional regulation, compromised coping. However, so far there is little data on quality of life and cognitive coping strategies to support their coherent inclusion in effective intervention programs [22,23].

A relatively large number of studies assessed the quality of life of children with ADHD and their parents. The results of these studies showed significant differences compared with the general population [24,25]. In a previously published study, we used The Family Quality of Life Survey (FQoL) to assess the family quality of life between two groups, families of children with ASD versus those of children with ADHD. We found no statistically significant differences between the two groups for the nine areas of FQoL (health, financial well-being, family relationships, support from others, support from services, values influence, career, leisure and recreational activities, community), the overall assessment of the family quality of life and overall satisfaction with the family quality of life [26]. Our results were consistent with those of The International Family Quality of Life Project. This study was conducted in 8 countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Israel, Japan, Nigeria, Slovenia and USA) and included families with at least one member with intellectual disabilities [27,28].

The aim of this study was to assess the cognitive coping strategies, emotional distress and the relationship between them and the quality of life in mothers of children with ASD compared with mothers of children with ADHD. We focused on mothers because they are primarily involved in child daily care and the therapeutic process. From our knowledge, no study addressed so far, comparatively, for ASD and ADHD, the parents’ quality of life and its relationship with their emotional distress or cognitive coping strategies.

2. METHOD

2.1. Sample

The data were collected from 114 mothers of children diagnosed according to DSM IV-TR international criteria with either ASD or ADHD. General information and questionnaires were filled in by mothers. Children included in the study were patients at Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic from ClujNapoca, Romania or followed a therapy program in various specialized centers in the country. Children diagnosed and treated in this clinic come from all parts of the region and are diverse in terms of socioeconomic status. Inclusion criteria were: mother of children aged 2 to 14 years, with a diagnosis of ASD or ADHD, according to DSM IV-TR criteria; the mother’s consent to participate in the study after they have been explained and they understood the clinical protocol. Exclusion criteria were: mother of children with a known serious medical condition, injury or major stressor in the last 6 months, children in foster care.

2.2. Instruments

The Family Quality of Life Survey (FQoL) was used to assess the family quality of life. FQoL is an instrument designed to assess the quality of life of the families that includes one or more members with intellectual or developmental disability. The instrument was used in an international study on family quality of life and the results can be compared with those obtained in the other eight countries that participated in the study [28].

Cognitive-Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) was used to assess cognitive coping strategies. CERQ is a multidimensional questionnaire, designed to identify cognitive coping strategies that a person uses when experiencing negative events or situations. It has 36 items and assesses nine cognitive coping strategies: 1) Selfblame: thoughts of putting the blame for what you have experienced on yourself; 2) Other-blame: thoughts of putting the blame for what you have experienced on the environment or another person; 3) Rumination: thinking about the feelings and thoughts associated with the negative event; 4) Catastrophizing: thoughts of explicitly emphasizing the terror of what you have experienced; 5) Putting into perspective: thoughts of brushing aside the seriousness of the event/emphasizing the relativity when comparing it to other events; 6) Positive refocusing: thinking about joyful and pleasant issues instead of thinking about the actual event; 7) Positive reappraisal: thoughts of creating a positive meaning to the event in terms of personal growth; 8) Acceptance: thoughts of accepting what you have experienced and resigning yourself to what has happened; 9) Refocus on planning: to thinking about what steps to take and how to handle the negative event [15,29].

Profile of Affective Distress (PAD) was used to assess emotions. It has 39 items and assesses the subjective dimension of negative emotions (functional and dysfunctional) [30].

The demographic data were obtained through a questionnaire containing questions about the patient (age, sex, age at diagnosis, psychotherapy or medication interventions) and his family (mother and father’s age, marital status, education level, occupation).

2.3. Design

The study is cross-sectional and was carried out between January 2011 and November 2011. Parents and children, who agreed to participate in the study, received additional information and signed the informed consent. For all the children included in the study we required and obtained the consent to use medical data, ensuring the privacy and subject’s identity protection. Psychiatric and somatic assessments were performed to establish the subjects’ eligibility and to review the diagnosis according to DSM IV-TR criteria. After the clinical interview, each parent filled in the questionnaires CERQ, PAD and FQoL. Data were supplemented with information from the patients’ charts and other medical documents. The questionnaires were filled in by the mothers for all children included in the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were collected into a SPSS database (version 17). Univariate statistical analysis was used to describe the studied population and the FQoL data. Bivariate statistical analysis (Pearson correlation, t test for independent samples) was used to identify significant associations between groups. The statistically significant differences between the correlation coefficients, obtained for the two groups at CERQ, were tested using t-test, for the interaction effect between each coping strategy and group, on the overall assessment of the family quality of life.

2.5. Ethical Aspects

The study was carried according to the law concerning the conduct of clinical trials, including abidance by international ethical standards foreseen in the Helsinki Declaration of Human Rights, updated. We obtained the approval of the Local Ethics Committee to conduct the study. Parents and children who agreed to participate in the study signed the informed consent.

3. RESULTS

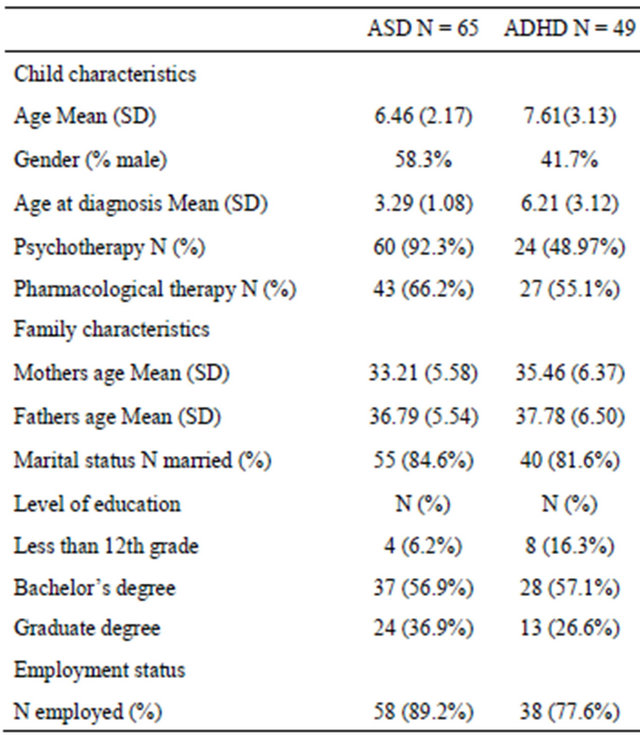

Data on child characteristics (age, gender, age at diagnosis, psychotherapy or medication interventions) and family (mother and father’s age, marital status, education level, occupation) were collected from 65 mothers in the ASD group and 49 mothers in the ADHD group (Table 1). Most of the children included in the study were boys. The mean age for ASD group was 6.46 years, respectively 7.61 years for ADHD group. Most children received psychological or pharmacological therapy. The

Table 1. Samples demographic description.

mothers mean age was 33.21 years for ASD group and 35.46 years for ADHD group. Fathers’ age was higher, with a mean age of 36.79 years for ASD group and 37.78 years for ADHD group. In both groups most mothers were married, with secondary education and employed. For the overall assessment of family quality of life, the mean values were 2.89 for the ASD group and 2.61 for the ADHD group.

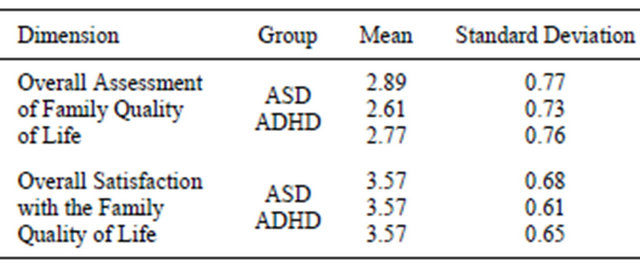

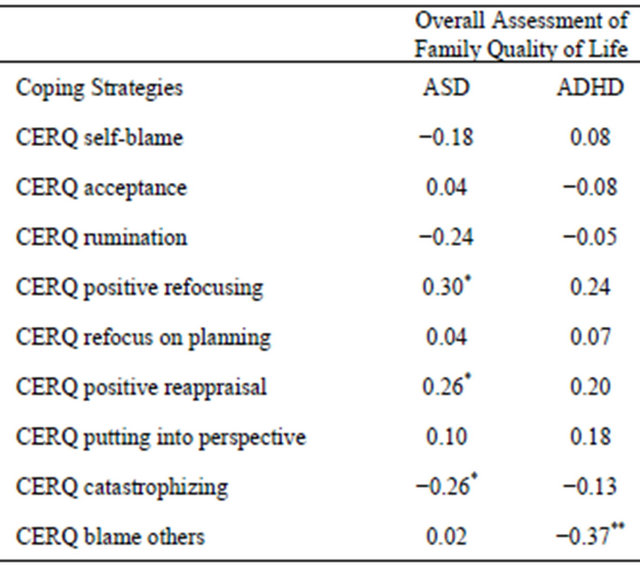

For the overall satisfaction with the family quality of life, the mean was 3.57 for both groups (Table 2). Statistical analysis comparing the results obtained on the nine areas of family quality of life assessed by FQoL, between the families of children with ASD and ADHD, showed lack of statistically significance. In the next step we decided to analyze the cognitive coping strategies in relation to the overall assessment of the family quality of life (Table 3). For ASD group, the significant correlates of the overall assessment of the family quality of life were: CERQ positive refocusing (r = 0.30, p < 0.05), positive reappraisal CERQ (r = 0.26, p < 0.05), respectively CERQ catastrophizing (r = −0.26, p <0.05), all values being moderate. CERQ rumination showed a moderate value (r = −0.24), but with no statistically signifiTable 2. Mean and standard deviation of the overall dimensions of the family quality of life (FQoL) in ASD and ADHD groups.

Table 3. Mothers coping strategies correlation with the overall assessment of the family quality of life.

*significant correlation at p < 0.05; **significant correlation at p < 0.01.

cance for the analyzed sample (N = 65). For the ADHD group, the significant correlate was just the strategy CERQ blame others (r = −0.37, p < 0.01), correlation of medium intensity. Following these results, we examine whether there are statistically significant differences between the correlation coefficients obtained for the two groups. The results showed a lack of statistically significant differences for the following strategies: CERQ selfblame (t = 1.47, p > 0.05), CERQ acceptance (t = −0.65, p > 0.05), CERQ rumination (t = 0.85, p > 0.05), CERQ positive refocusing (t = −0.41, p > 0.05), CERQ refocus on planning (t = 0.10, p > 0.05), CERQ positive reappraisal (t = 0.47, p > 0.05), CERQ putting into perspective (t = 0.29, p > 0.05), respectively CERQ catastrophizing (t = 0.54, p > 0.05). CERQ blame others (t = −2.13, p = 0.03) was the only coping strategy, whose relationship with the overall assessment of the family quality of life was moderated by the diagnostic category. The same type of analysis was performed for the emotional distress and its components (negative dysfunctional emotions, worry/anxiety dysfunctional emotions and sadness/depression dysfunctional emotions) assessed by PAD (Table 4).

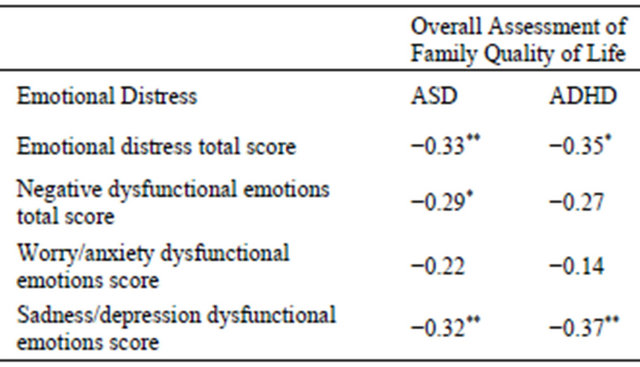

For the ASD group, the significant correlates of the overall assessment of the family quality of life were: the emotional distress total score (r = −0.33, p < 0.01), negative dysfunctional emotions total score (r = −0.29, p < 0.05) and sadness/depression dysfunctional emotions score (r = −0.32, p < 0.01). For the ADHD group, significant correlations were obtained for the emotional distress total score (r = −0.35, p < 0.05) and sadness/ depression dysfunctional emotions score (r = −0.37, p < 0.01). When analyzing the overall assessment of the family quality of life correlations with the parents emotional distress differences between the two groups, we found no significant differences for: emotional distress total score (t = 0.44, p > 0.05), negative dysfunctional emotions score (t = 0.78, p > 0.05), worry/anxiety dysfunctional emotions score (t = 1.05, p > 0.05) and sadness/depression dysfunctional emotions score (t = 0.39, p > 0.05).

Table 4. Mothers emotional distress correlation with the overall assessment of the family quality of life.

*significant correlation at p < 0.05; **significant correlation at p < 0.01.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Main Findings

There is clear evidence regarding the quality of life impairment in parents who have a child with ASD or ADHD. The available data suggest a higher level of family stress for parents of children with ASD or ADHD [8- 10,16,22,24], compared with nonclinical population. However, there are very few studies that compared the quality of life of parents who have a child with ASD to that of parents who have a child with another type of pathology (somatic or psychiatric) [11,31]. In a previously published study, we found no statistically significant differences between the two groups for the FQoL dimensions: health, financial well-being, family relationships, support from others, support from services, values influence, career, leisure and recreational activities, community. The only dimension of the FQoL that showed a difference very close to statistical significance was family satisfaction; families of children with ADHD reported lower levels of satisfaction on family relationships [26].

In our study, parents’ cognitive coping strategies, measured by CERQ were tested in relation to the overall assessment of family quality of life, separately for ASD and ADHD groups. For the ASD group, the overall assessment of family quality of life correlated positively with positive refocusing and positive reappraisal strategies and negatively with catastrophising strategy. At a sample N = 70, the rumination strategy correlation coefficient would have become statistically significant, at p < 0.05. For the ADHD group, the only strategy that correlated negatively with the overall assessment of family quality of life was the blame others strategy. The results are consistent with other studies, suggesting that the use of adaptive coping strategies correlate with a higher family quality of life, while for the maladaptive ones, the relationship is reversed. Stuart and McGrew (2009) reported a protective effect for social support and a negative one for the maladaptive coping strategies on the difficulty experienced by parents of children with autism [21]. Similar results were described by Altiere and von Kluge (2009). They found a greater use of adaptive coping mechanisms and social support for parents of children with autism with good family relationships, than for those with family problems or separated [18]. However, these studies focused on coping in general, including in terms of behavior and were not limited exclusively to cognitive coping. Veek et al. (2009) evaluated particularly the cognitive coping strategies, in a study on children with Down syndrome. Acceptance, positive reappraisal and catastrophizing strategies were predictors of parental stress, while blame others strategy was not emphasized as influencing the parental stress [32]. In our study, the only coping strategy whose relationship with the overall assessment of the family quality of life was moderated by diagnostic category, was blame others. The correlation was significantly higher for the ADHD group, a negative relationship, meaning that less usage of blame others coping strategy associates with higher perceived quality of life.

Parents of children with ASD have often depression or anxiety symptoms of subclinical or clinical intensity [20, 23]. Our results are consistent with the literature and highlight the relationship between quality of life and global distress. The overall assessment of family quality of life correlated with emotional distress, negative dysfunctional emotions and sadness/depression dysfunctional emotions, but, surprisingly, did not correlated with worry/anxiety dysfunctional emotions. In 2008, Smith et al. found that more than one-third of the mothers of children and adolescents with autism had depression symptoms higher than the clinical cut-off [33]. In 2005, Hastings et al. reported that most studies consider the child with autism a source of stress affecting the other family members’ wellbeing. This view describes only unidirectional the relationship between children with ASD and family members. This relationship can be also bidirectional, meaning that family members may also influence the children with ASD [23]. In our study, the diagnosis category did not moderate the intensity and/or the relationship between parents’ emotional distress and the overall assessment of the family quality of life. The assessment pressure felt by the mothers may explain these results. ASD and ADHD are chronic psychiatric conditions affecting pervasive all areas of functioning and require multimodal interventions. The parents, mostly the mothers, are involved in child care routine, but also in the long term forms of therapy and education. In these circumstances, the parents related factors influencing the quality of life are of special importance (the emotional distress and coping strategies used).

In ASD and ADHD, the scientifically validated psychological interventions address both children and caregivers, and consist of cognitive behavioral approaches. Emotional distress and its relationship with the cognitive coping strategies play a decisive role in emotional regulation and type of adjustment to negative life events. Therefore, correct identification of specific cognitive coping strategies and their relationship with quality of life (that became the main therapeutic outcome) are essential for therapy efficiency.

4.2. Study Limits

The study is cross-sectional and the correlation nature of the results does not allow a causal relationship deduction. An important limit is represented by the relatively small size of the clinical sample. The psychometric instruments were filled in by mothers and reflect their perception on the family quality of life, at the time the assessment was made. In this circumstance, the reporting accuracy might be affected and can lead to data bias.

5. CONCLUSION/RECOMMENDATIONS

The overall assessment of family quality of life correlated with the negative dysfunctional emotions and sadness/depression dysfunctional emotions scores, in both groups. Although we didn’t found significant differences between the ASD and ADHD groups for the FQoL dimensions assessed by the mothers, we found differences in their use of cognitive coping strategies. Comparative studies between different pathologies are useful to identify pathology specific elements that affect the quality of life. Future studies should investigate the pattern of cognitive strategies used by the parents of children with various disorders. These studies should be longitudinal and involving large clinical samples. Thus, quality of life could be more easily and accurately assessed in the diagnosis, establishing and monitoring the therapeutic outcomes processes.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was possible with the financial support of the Sectoral Operational Program for Human Resources Development 2007-2013, cofinanced by the European Social Fund, within the project POSDRU 89/1.5/S/60189 with the title “Postdoctoral Programs for Sustainable Development in a Knowledge Based Society”.

REFERENCES

- Tsay, L.Y. (2004) Autistic disorder. In: Wiener, J.M. and Dulcan, M.K., Eds., Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, 261, 264, 268-273.

- Faraone, S.V. (2010) How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Research, 177, 299-304. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010

- Fombonne, E. (2009) Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatric Research, 65, 591-598. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e7203

- Polanczyk, G., de Lima, M.S., Horta, B.L., Biederman, J. and Rohde, L.A. (2007) The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 942-948. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.942

- Lee, L., Harrington, R.A., Louie, B.B. and Newschaffer, C.J. (2008) Children with autism: Quality of life and parental concerns. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1147-1160. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0491-0

- Cummins, R.A. (2005) Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 699-706. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00738.x

- Verdugo, M.A., Schalock, R.L., Keith, K.D. and Stancliffe, R.J. (2005) Quality of life and its measurement: Important principles and guidelines. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 707-717. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00739.x

- Kuhlthau, K., Orlich, F., Hall, T.A., Sikora, D., Kovacs, E.A., Delahaye, J. and Clemons, T.E. (2010) Health-related quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorders: Results from the autism treatment network. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 721-729. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0921-2

- Khanna, R., Madhavan, S.S., Smith, M.J., Patrick, J.H., Tworek, C. and Becker-Cottrill, B. (2011) Assessment of health-related quality of life among primary caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1214-1227. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1140-6

- Meirsschaut, M., Roeyers, H. and Warreyn, P. (2010) Parenting in families with a child with autism spectrum disorder and a typically developing child: Mothers’ experiences and cognitions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 661-669. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.01.002

- Hayes, S.A. and Watson, S.L. (2013) The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 629. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y

- Cappe, E. (2012) Effect of social and school inclusion on adjustment and quality of life of parents with a child having an autism spectrum disorder. Annales Medico-Psychologiques, 170, 471-475. doi:10.1016/j.amp.2012.06.015

- Karst, J.S. and Van Hecke, A.V. (2012) Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: A review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 247-277. doi:10.1007/s10567-012-0119-6

- Osborne, L.A., McHugh, L., Saunders, J. and Reed, P. (2008) Parenting stress reduces the effectiveness of early teaching interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1092- 1103. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0497-7

- Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V. and Spinhoven, P. (2001) Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 1311-1327. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6

- Pottie, C. and Ingram, K. (2008) Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: A multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 855-864. doi:10.1037/a0013604

- Weiss, J.A., Cappadocia, M.C., MacMullin, J.A., Viecili, M. and Lunsky, Y. (2012) The impact of child problem behaviors of children with ASD on parent mental health: The mediating role of acceptance and empowerment. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 16, 261-274. doi:10.1177/1362361311422708

- Altiere, M.J. and von Kluge, S. (2009) Family functioning and coping behaviors in parents of children with autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 83-92. doi:10.1007/s10826-008-9209-y

- Pisula, E. and Kossakowska, Z. (2010) Sense of coherence and coping with stress among mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1485-1494. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1001-3

- Benson, P.R. (2010) Coping, distress, and well-being in mothers of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 217-228. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.008

- Stuart, M. and McGrew, J.H. (2009) Caregiver burden after receiving a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorder, 3, 86-97. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.04.006

- Cappe, E., Wolff, M., Bobet, R. and Adrien, J. (2011) Quality of life: A key variable to consider in the evaluation of adjustment in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and in the development of relevant support and assistance programmes. Quality of Life Research, 20, 1279-1294. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9861-3

- Hastings, R.P., Kovshoff, H., Brown, T., Ward, N.J., Espinosa, F.D. and Remington, B. (2005) Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism, 9, 377-391. doi:10.1177/1362361305056078

- Spira, E.G. and Fischel, J.E. (2005) The impact of preschool inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity on social and academic development: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 46, 755-773. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01466.x

- Strine, T.W., Lesesne, C.A., Okoro, C.A., McGuire, L.C., Chapman, D.P. and Balluz, L.S. (2006) Emotional and behavioral difficulties and impairments in everyday functioning among children with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3, A52.

- Sipos, R., Predescu, E., Muresan, G. and Iftene, F. (2012) The evaluation of family quality of life of children with autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Applied Medical Informatics, 30, 1-8.

- Isaacs, B.J., Brown, I., Brown, R.I., Baum, N., Myerscough, T., Neikrug, S., Roth, D., Shearer, J. and Wang, M. (2007) The international family quality of life project: Goals and description of a survey tool. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 4, 177-185. doi:10.1111/j.1741-1130.2007.00116.x

- Brown, I. (2008) Comparison of trends in eight countries. Inspire, Muki Baum Treatmment Centres, 2, 9-13.

- Garnefski, N., van den Kommer, T., Kraaij, V., Teerds, J., Legerstee, J. and Onstein, E. (2002) The relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems. European Journal of Personality, 16, 403-420. doi:10.1002/per.458

- Opris, D. and Macavei, B. (2007) The profile of emotional distress; norms for the romanian population. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 7, 139- 157.

- Brereton, A.V., Tonge, B.J. and Einfeld, S.L. (2006) Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 863-870. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0125-y

- van der Veek, S., Kraaij, V. and Garnefski, N. (2009) Cognitive coping strategies and stress in parents of children with down syndrome: A prospective study. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 47, 295-306. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-47.4.295

- Smith, L.E., Seltzer, M.M., Tager-Flusberg, H., Greenberg, J.S. and Carter, A.S. (2008) A comparative analysis of well-being and coping among mothers of toddlers and mothers of adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 876-889. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0461-6

NOTES

*Corresponding author.