Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications

Vol.1 No.3(2011), Article ID:7245,5 pages DOI:10.4236/jcdsa.2011.13010

Early and Visible Improvements after Application of K101 in the Appearance of Nails Discoloured and Deformed by Onychomycosis

![]()

1Department of Dermatology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; 2Möllevångens Husläkargrupp, Malmö, Sweden; 3Moberg Derma AB, Bromma, Sweden.

Email: jan.faergemann@derm.gu.se

Received June 9th, 2011; revised July 14th, 2011; accepted July 19th, 2011.

Keywords: K101, Onychomycosis, Early Effects, Topical

ABSTRACT

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nails of the fingers and toes and is difficult to cure. A previous 24-week, placebo-controlled study demonstrated that a solution containing propylene glycol, urea and lactic acid (K101) was well-tolerated and effective in the treatment of onychomycosis. Patients who received K101 judged that their condition had improved from Week 2 of treatment onwards. The aim of the current study was to further evaluate and document early visible effects on nail appearance after application of topical K101 in an 8-week baseline-controlled study in 75 patients. Patients graded the appearance of their nail compared with baseline using a four-point scale. Compared with baseline, 91.8% (67/73; 95% confidence interval (CI): 83.0%, 96.9%) of the patients experienced at least some improvement in their target nail after 8 weeks of treatment. At Week 2, the proportion showing some improvement was 76.7% (56/73; 95% CI: 65.4%, 85.8%) with this number increasing to 87.7% (64/73; 95% CI: 77.9%, 94.2%) at Week 4. Proportions of patients reporting less thickened, less discoloured, less brittle and softer nails increased over the course of the study. No safety issues were identified. In conclusion, K101 provided early visible improvements in nails affected by onychomycosis.

1. Introduction

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection that affects the nails of the hand and foot. Infection rates in Western adult populations range from 2% to 14%, although onychomycosis may affect up to 50% of people over 70 years of age [1]. Prevalence of onychomycosis is also higher in the immuno-compromised, children with Down’s syndrome and patients with diseases that affect the peripheral circulation, such as diabetes mellitus [2,3]. Onychomycosis is often associated with pain and discomfort coupled with a significant negative impact on emotional health and social image [4,5].

Onychomycosis can be treated pharmacologically with both systemic and topical agents [6]. Systemic antifungal drugs such as terbinafine and itraconazole are effective treatments; although their use must be balanced against the risk of unpleasant side-effects that include gastrointestinal disorders, skin rashes and headache [5,7]. Serious side-effects occur in less than 1% of patients, but these can include fatal liver toxicity [8]. Topical agents are usually formulated as lacquers that adhere to the nail plate and include antifungal drugs such as amorolfine, tioconazole and ciclopirox 8% [5,7]. Topical application allows targeted delivery to infected areas, minimising the risk of secondary effects related to systemic exposure.

K101, a topical treatment for onychomycosis, is a combination of propylene glycol, urea and lactic acid. The concept of using propylene glycol solutions of urea and lactic acid to treat onychomycosis was investigated in a study of 23 patients who applied a test solution twice daily for 2 - 6 months. The solution was effective in 21 of the 23 patients treated [9]. The efficacy of K101 was confirmed in a placebo-controlled study that documented the efficacy and tolerability of K101 versus placebo in 493 patients with onychomycosis. A greater number of patients who received K101 experienced mycological cure after 26 weeks of treatment (27% versus 10%) [10]. Also, almost half the patients who received K101 considered that their condition had shown at least some improvement from Week 2, and approximately 75% from Week 8 of treatment onwards. In the light of these findings, and to investigate in more detail the early clinical effects of K101, we conducted an 8-week study in patients with nails affected by onychomycosis.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

The study population comprised men and women aged at least 18 years with clinically diagnosed onychomycosis affecting between 25% and 75% of at least one big toenail or thumbnail. Patients were excluded if they had proximal subungual onychomycosis or other conditions known to cause abnormal nail appearance. Patients who had participated in another study with K101 or in any study with an investigational drug or device within 4 weeks of screening were ineligible, as were patients who had used topical antifungal nail treatment within 1 month or systemic antifungal treatment within 3 months of screening. Patients with a known allergy to any of the study treatment components were excluded from the study. The study was conducted at Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Gothenburg, Sweden) and Möllevångens Husläkar-grupp (Malmö, Sweden) after approval by the Regional Ethics Committee (Gothenburg, Sweden). All patients provided signed and dated informed consent prior to screening.

2.2. Study Design

This was an 8-week baseline-controlled study to assess the efficacy of K101 in improving nail appearance. At the baseline visit at the study site, patients were taught how to apply K101 by study staff. K101 is a clear, colourless liquid supplied in a 10 mL plastic tube with a silicon drop tip to ensure accurate application to the affected nail. A thin layer of the K101 solution was applied to all affected fingers and/or toenails at bedtime every day. An affected big toenail or thumbnail was selected as the target nail for all subsequent assessments. After their visit at baseline, patients returned 2, 4 and 8 weeks after starting treatment to undergo efficacy and safety evaluations. At each study visit after starting treatment, patients were asked “On average, how many days per week have you applied the test product since last visit?”.

2.3. Efficacy Assessments

The target nail was photographed in a standardised way using a digital camera and camera stand; the stand was equipped with lighting to create consistent light conditions. Care was taken to ensure that the distance between the camera and the nail was exactly the same for all patients. Photographs were taken at baseline and after 2, 4 and 8 weeks of treatment. Patients were asked the following question: “How do you perceive your target nail appearance compared to baseline?”, and then evaluated the efficacy of their treatment using a four-point Global Assessment Scale. The scores used were: 1) no improvement; 2) some improvement; 3) clear improvement; and 4) very good improvement. Patients were also asked whether the target nail had become less thickened, discoloured or brittle and whether it had softened.

2.4. Safety Assessments

Adverse events were recorded from the start of the first treatment period to the end of the study. At each study visit, investigators asked patients the following question: “Have you had any health problems since your last visit?”. The Investigator rated any reported events for intensity and relationship to study treatment.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Seventy patients were to be enrolled to provide 65 evaluable patients. With a sample size of 65, a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the proportion of patients who experienced at least some improvement in target nail appearance (who scored 2 or more according to the Global Assessment Scale) after 8 weeks’ treatment, was to extend 0.12 from the observed proportion for an expected proportion of 0.50.

The primary efficacy endpoint was an improvement in target nail appearance at 8 weeks compared with baseline, which was defined as the proportion of patients scoring at least 2 on the Global Assessment Scale. Other endpoints included the proportion of patients scoring at least 2 on the Global Assessment Scale at Week 2 and Week 4 and individual nail attributes at Week 2, Week 4 and Week 8. All efficacy endpoints were presented as point estimates with two-sided 95% CIs computed using the Clopper-Pearson (exact) method. Adherence was calculated as the percentage of maximum use of K101.

The safety analysis set comprised all randomised patients who applied study medication at least once. The per protocol set was a subset of the full analysis set and consisted of patients with 80% adherence who had not experienced major protocol violations and who had a measure of the primary endpoint. SAS® software (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Disposition

Seventy-five patients were enrolled and 72 completed the study. The mean age of the patients was 60 years. Most patients were male (63.5%) and Caucasian (97.3%). Three patients were discontinued from the study: one due to protocol non-compliance and two due to non-attendance at follow-up visits. All patients had abnormal finger and/or toenails and 22 (29.7%) had abnormal skin on hands and feet as a result of fungal infection. Overall, mean (standard deviation) adherence was 99.45 (2.3)% (full analysis set).

3.2. Efficacy Results

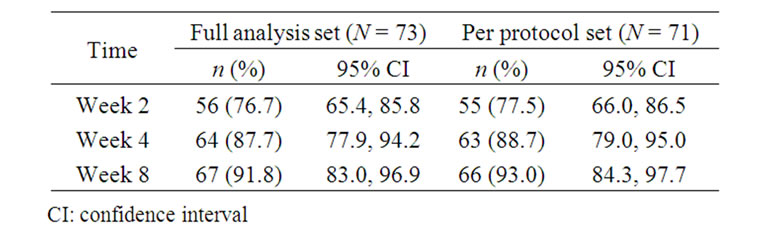

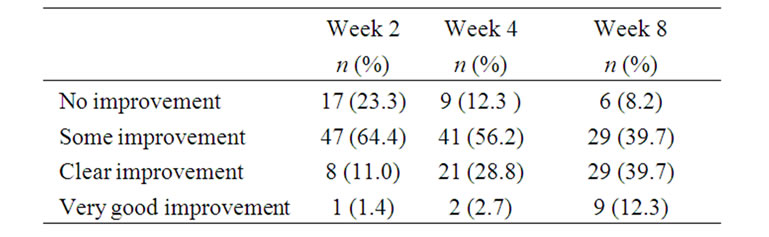

The proportion of patients experiencing at least some improvement of the target nail at 8 weeks, compared with baseline, was 91.8% (67/73 patients; 95% CI; 83.0, 96.9) (Table 1: full analysis set). After 2 weeks of treatment, 76.7% (56/73) of patients experienced at least some improvement of the target nail; this proportion increased to 87.7% (64/73) after 4 weeks. Similar results were obtained for the per protocol data set. During the treatment period, the number (%) of patients reporting clear/very good improvement of the target nail increased from nine (12.4%) at Week 2 to 38 (52.0%) at Week 8 (Table 2).

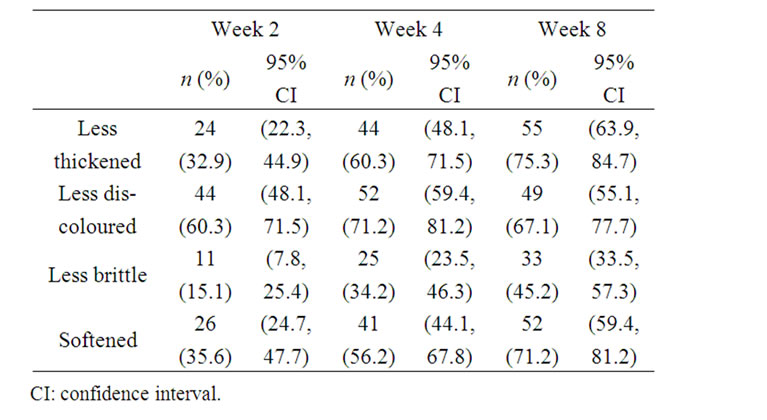

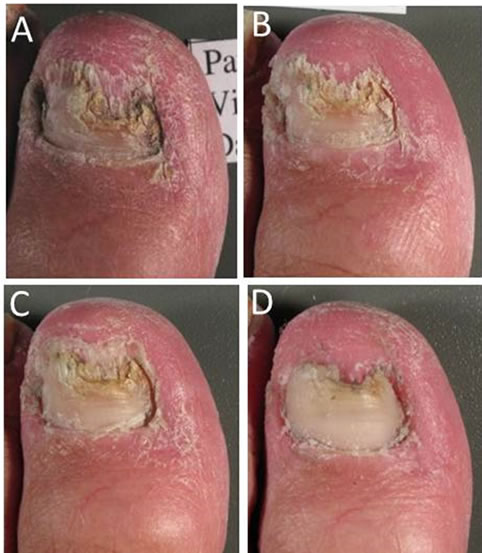

Over the 8 weeks of the study, increasing proportions of patients reported that, compared with baseline, their target nails were less thickened (from 32.9% at Week 2 to 75.3% at Week 8), less discoloured (from 60.3% to 67.1%), less brittle (from 15.1% to 45.2%) and softened (from 35.6% to 71.2%) (Table 3). Visible improvements in the condition of the target nails from baseline to Week 8 are presented in Figure 1 for a patient with infection of moderate baseline intensity and in Figure 2 for a patient with infection of severe baseline intensity. In the course of treatment, visible signs of fungal infection regressed

Table 1. Improvement in target nail (defined as a score ≥ 2 on the Global Assessment Scale).

Table 2. Patient experience of target nail appearance compared with baseline (full analysis set; N = 73).

Table 3. Patient assessment of individual nail attributes (full analysis set; N = 73).

Figure 1. Photographic sequence showing target nail appearance at baseline (Panel A), at Week 2 (Panel B), Week 4 (Panel C) and Week 8 (Panel D) for a patient with onychomycosis of moderate intensity at baseline.

Figure 2. Photographic sequence showing target nail appearance at baseline (Panel A), at Week 2 (Panel B), Week 4 (Panel C) and Week 8 (Panel D) for a patient with onychomycosis of severe intensity at baseline.

and in general, a more uniform and smooth appearance was observed throughout the nail.

3.3. Safety and Tolerability

Eight patients (10.8%) experienced nine adverse event episodes; none of these was judged to be related to K101 by the Investigator. Seven of the events were considered to be mild and two were moderate in intensity. The most frequently reported adverse event was rhinorrhoea (n = 4).

4. Discussion

This 8-week, open-label study was designed to evaluate the early clinical effects of treatment with K101 in patients with onychomycosis. Efficacy was assessed in terms of improvement from baseline in nail appearance. Standardised photographic techniques were used to document at regular intervals any changes in appearance from baseline. With just 2 weeks of treatment the proportion of patients with visible improvements in the target nail was of 76.7% and this number increased to 91.8% by Week 8 (primary endpoint). As the study progressed, treatment was associated with the retreat of typical signs of fungal nail infection such as the development of a less discoloured and smoother nail surface.

When rating the condition of their nails for thickness, discolouration, brittleness and softness, patients generally reported improvements from baseline at Week 2, Week 4 and Week 8. These data support the findings of a previous study in which half the patients enrolled (152/304 patients) perceived at least some improvement in their condition after only 2 weeks of treatment [10].

There are limited data within the scientific literature on adherence to treatment in patients with onychomycosis, with the available data generally determined in studies of oral treatments rather than topical applications. One study reported that the key determinants in patient preferences for an oral onychomycosis treatment were duration of therapy, frequency of treatment and number of drugs [11]. Another study concluded that the main reasons for patient non-adherence were adverse events, financial restraints and the premature perception by patients that the improvement in their condition was associated with cure [12]. In terms of factors known to affect patient adherence in the current study, treatment with K101 was associated with a very low incidence of adverse effects and only once daily application was required. Results from the present study clearly indicate that the majority of patients were very happy with early positive results and this encouraged them to achieve the very high levels of adherence that were observed (99%).

K101 was very well-tolerated in patients in the current study; no adverse events were judged to be treatmentrelated by the Investigator. In a 24-week long, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with K101, irritation/pain was observed in the periungual skin in 22 (6.4%) patients who received K101. In that study, K101 was applied to the nail drop-wise, which presumably increased the likelihood that the solution would contact and leach into the skin surrounding the infected nail. Also, the target nail was occluded with surgical tape for the first 4 weeks of treatment, which may have amplified skin irritation. In the current study, the applicator consisted of a tube with a silicon tip so that the K101 solution could be spread more precisely over the nail surface, thus minimising the risk for irritation or pain in the periungual skin. Photographs from the current study showed that, in some cases, the treated nails became more opaque. However, this was not reflected in the adverse event reporting indicating that patients did not consider this to be a problem.

In conclusion, data from the current study support earlier findings that clearly demonstrate rapid improvements in nail condition after application of K101; early, visible, positive effects compared with baseline were observed from 2 weeks onwards. This topically applied solution also appears to demonstrate characteristics conducive to good adherence such as an excellent tolerability profile and once daily application.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and staff who participated in the study. This study was funded by Moberg Derma AB.

REFERENCES

- B. E. Elewski and M. A. Charif, “Prevalence of Onychomycosis in Patients Attending a Dermatology Clinic in Northeastern Ohio for Other Conditions,” Archives of Dermatology, Vol. 133, No. 9, 1997, pp. 1172-1173. doi.org/10.1001/archderm.133.9.1172

- A. K. Gupta, N. Konnikov, P. MacDonald, P. Rich, N. W. Rodger, M. W. Edmonds, et al., “Prevalence and Epidemiology of Toenail Onychomycosis in Diabetic Subjects: A Multicentre Survey,” British Journal of Dermatology, Vol. 139, No. 4, 1998, pp. 665-671. doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02464.x

- E. L. Svejgaard and J. Nilsson, “Onychomycosis in Denmark: Prevalence of Fungal Nail Infection in General Practice,” Mycoses, Vol. 47, No. 3-4, 2004, pp. 131-135.

- B. Elewski, “Onychomycosis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management,” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1998, pp. 415-429.

- D. de Berker, “Clinical Practice. Fungal Nail Disease,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 360, No. 20, 2009, pp. 2108-2116. doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp0804878

- A. K. Gupta, M. Uro and E. A. Cooper, “Onychomycosis Therapy: Past, Present, Future,” Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, Vol. 9, No. 9, 2010, pp. 1109-1113.

- O. Welsh, L. Vera-Cabrera and E. Welsh, “Onychomycosis,” Clinics in Dermatology, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2010, pp. 151-159. doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.12.006

- D. P. O’Sullivan, C. A. Needham, A. Bangs, K. Atkin and F. D. Kendall, “Postmarketing Surveillance of Oral Terbinafine in the UK: Report of a Large Cohort Study,” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Vol. 42, No. 5, 1996, pp. 559-565.

- J. Faergemann and G. Swanbeck, “Treatment of Onychomycosis with a Propylene Glycol-Urea-Lactic Acid Solution,” Mycoses, Vol. 32, No. 10, 1989, pp. 536-540. doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02178.x

- L. Emtestam, T. Kaaman and K. Rensfeldt, “Treatment of Distal Subungual Onychomycosis with a Topical Preparation of Urea, Propylene Glycol and Lactic Acid: Results of a 24-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study,” Unpublished.

- S. Nolting, J. Carazo, K. Boulle and J. R. Lambert, “Oral Treatment Schedules for Onychomycosis: A Study of Patient Preference,” International Journal of Dermatology, Vol. 37, No. 6, 1998, pp. 454-456. doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00357.x

- Y. Hu, L. Yang, L. Wei, X. Y. Dai, H. K. Hua, J. Qi, et al., “Study on the Compliance and Safety of the Oral Antifungal Agents for the Treatment of Onychomycosis,” Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 26, No. 12, 2005, pp. 988-991.