Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 87-93 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.31011 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 87 Prosody and Quantifier Float in Japanese Kenji Yokota College of Industrial Technology, Nihon University, Japan Email: yokota.kenji@nihon-u.ac.jp Received December 9th, 2012; revised January 2nd, 2013; accepted January 10th, 2013 The paper investigates the information structure that licenses the Japanese floating numeral quantifier (FNQ) in terms of prosody and context from the point of view that the pitch reset on the FNQ affects the information structure and plays a crucial role in determining the interpretation of the FNQ. I will show that FNQ sentences are potentially ambiguous between an event-quantifier reading (i.e., a VP-related FNQ reading), and an object-quantifier reading (i.e., an NP-related FNQ reading) where such a reading is possible. The syntactic and semantic difference yields distinct prosodic phrasings (in accordance with in- formation-structure) which contribute to the disambiguation of the two readings (and hence the gram- maticality). Keywords: Floating Numeral Quantifiers; Japanese; Prosody; Syntax; Information Structure Introduction Discourse effects supposedly affecting the processing of the floating numeral quantifier (hereafter, FNQ) construction in Japanese is not yet known1. Through the examination of FNQ interpretation, this paper argues that the Japanese FNQ should be defined as an instance of expressing a discourse relation, with an emphasis on the nature of its prosodic realization in a given discourse2. Most previous analyses of Japanese FNQ constructions appear problematic because relevant data are given in isolation without contexts. The present study instead shows that interpretational ambiguity between distributive and non-distributive readings is affected by contextual effects. To be more specific, the important aspect of my proposal is the relation between structure (along with meaning) and intonation (along with context). Given that information structure has clear effects on FNQ interpretation, it will be premature to conclude that the FNQ construction is categorized as a VP-adverb and necessarily yields a distributive reading (Gunji & Hasida, 1998; Kobuchi, 2003; Nakanishi, 2004, among others). I instead sug- gest that much more serious attention needs to be paid to pro- sodic structure than usually exercised in conducting tests for judgments of acceptability (Fodor, 2002; Kitagawa & Fodor, 2006), which lends support to a prosodic-based account that explains in a straightforward way FNQ constructions as in- stances of information structure3. The contents of the paper are as follows: In Section 2, I describe problems and issues with previous studies. Section 3, I focus on the interpretational facts observed in FNQ constructions. Section 4 discusses effects of prosody on the construction. Section 5 concludes the paper. Issues In this section, I discuss the issues to be explored in this pa- per. There have been two major contradictory views concerning Japanese FNQs. One is that the FNQs observe syntactic locality (e.g., mutual c-command) with its associated NP (Haig, 1980; Kuroda, 1980; Miyagawa, 1981; Miyagawa & Arikawa, 2007, among others), the other is that FNQs are predicate modifiers and free from such locality (Kuno, 1978; Fukushima, 1991; Gunji & Hasida, 1998; Takami, 1998; Kobuchi, 2003; Naka- nishi, 2007, 2008, among others). The current study assumes that both insights are to be bonded to each other for the purpose of meeting the need for the adequate analysis of Japanese FNQ interpretation. What we need to consider is the fact that in some cases FNQs generate event-related readings, and in others they produce object-related readings. FNQ expressions, unlike the common assumption mentioned above, do not necessarily force a distributive interpretation in terms of reference to objects (or agenthood) or events (or situations). Under the definition rely- ing on events, in Kitagawa and Kuroda’s (1992) sense, the dis- tributive property necessarily implies the occurrence of multi- ple events as shown in 1a), while the non-distributive construal implies the occurrence of only a single event as in 1b). 1) a) Kono isshuukan no aidani shuujin ga san-nin this one week GEN during prisoner NOM three-CL nigedashita. [Distributive] escaped “There have been three jailbreaks this week.” b) Sonotoki totsuzen shuujin ga san-nin then suddenly prisoner NOM three-CL abaredashita. [Non-distributive] 1The term “float” does not have a precise self-evident definition. I will use it essentially as a convenient label (or a figurative expression) for the gram- matical phenomenon in question, partly because it is widespread in the literature. 2Unless otherwise noted, FNQs refer to Japanese subject-oriented (or sub- ect-related) FNQs in this paper. 3Information structure can, in principle, have an immediate influence on relational syntactic processing (see, e.g., Steedman, 2000). started to act violently “Then, a group of three prisoners suddenly started to act violently.” (Kitagawa & Kuroda, 1992: p. 50) Whether we define the meaning of a “distributive reading” in  K. YOKOTA terms of properties of individual objects or events, their obser- vation seems correct and still deserves careful attention. Gen- eration of non-distributive interpretations, as exemplified in 1b) suggests that the previous account assuming that all FNQs ob- ligatorily function as a verb modifier, and quantifies over ev- ents and always yields distributivity are in need of modifica- tion before it is able to incorporate these facts. In recent studies working on syntax and semantics of Japa- nese quantifier float, Nakanishi (2007, 2008) reports prosodic effects as illustrated in 2) (see also Kitagawa & Kuroda, 1992; Fujita, 1994; Kobuchi, 2003)4. There are significant semantic differences between the two. Nakanishi notes sentence 2) is ambiguous between distributive 2a) and non-distributive (e.g., collective) 2b) readings without a boundary, whereas it only allows a distributive reading with a boundary 2a). In her ac- count, the two structures are disambiguated by distinctive pitch patterns, whether or not pauses are present right after the sub- ject NP. 2) [NP Gakusei ga] (//) go-nin tsukue o mochiage-ta. student NOM five-CL desk ACC lift-Past a) “Five (of the) students lifted a desk (individually).” (Distributive interpretation) b) “Five students lifted a desk (together).” (Non-distributive interpretation) Nakanishi’s claim, however, is not sufficient to explain the nature of FNQ construal. As shown below, such ambiguity seems to be very common, and have a direct bearing on the in- formation structure. Silent reading of sentences such as 2) may permit a different range of interpretations from actually pro- nounced examples, but that range is still controlled by prosody (see Kitagawa & Fodor, 2006 for further discussion). I will show that this follows from the interaction between intonation and structure, and that prosody and context appear to be as important as syntax for the interpretation of FNQ sentences. Observations in 2) enable us to assume that intonation often determines which of the many possible bracketing permitted by the syntax of Japanese is intended, and that the interpretations of the constituents may be related to distinctions of informa- tion-structural significance among the concepts/intention that the speaker has in mind (Steedman, 2000: p. 51). I will provide a basis for this assumption in what follows. The core of my analysis developed in what follows is that in regard to the in- terpretation of FNQ sentences, semantics in principle generates both distributive and non-distributive readings, and the prefer- ence is determined by discourse factors. Syntactic and Semantic Considerations It is generally agreed that prosodic grouping is crucial in un- derstanding syntactic (licensing) relations (see, e.g., Selkirk, 1995; Steedman, 2000; Ishihara, 2011). Given this assumption, I will first provide the syntactic and semantic foundation for an analysis of Japanese FNQ constructions, which offers basic assumptions necessary for the discussion in subsequent sec- tions. Following Ishii (1998, 1999) and Yokota (2009), I propose that there are (at least) two types of FNQs in Japanese: NP- related FNQs and VP-related ones. The FNQ in 2) presumably occurs either within a nominal domain or within a verbal do- main. Note that this FNQ expression is clearly differentiated from NP-local numeral quantifiers (Non-FNQs in our terms), which has both distributive and non-distributive readings5. 3) [Go-nin no gakusei ga] tsukue o mochiage-ta. five-CL GEN student NOM desk ACC lift-Past (Distributive and Non-distributive) In her serial works, Nakanishi contends that all FNQs quan- tify over events and hence produces a distributive interpretation. However, it should be noticed that Nakanishi (2007: p. 76) only states that FNQ constructions permit collective readings (non- distributive in our terms) in certain environments. Limiting the discussion to the subject-oriented FNQ in this study, as exemplified in 2), it can be said that FNQ sentences are ambiguous between i) the event-related reading (i.e., VP- related FNQ), and ii) the object-related reading (i.e., NP-related FNQ) where possible. My claim is that the two structures can be disambiguated by distinctive pitch patterns. With regard to FNQ construal, a preferred reading is selected with the help of prosody (in accordance with the information structure) from a set of possible readings available, indicated by the characteris- tic semantic features such as (±distributive, ±partitive). Possi- ble structures that we are assuming look like 4): 4) Syntactic structures of 2): [NP Gakusei ga] (//) go-nin tsukue o mochiage-ta. (= 2)) student NOM five-CL desk ACC lift-Past a) [NP3 [NP1 gakusei ga] [NP2 go-nin]] [VP tsukue o mochiageta] ⇒ NP-related FNQ: {(−part +dist), (−part −dist)} b) [NP1 gakusei ga] [VP [NP2 go-nin] tsukue o mochiageta] ⇒ VP-related FNQ: {(+part +dist), (+part −dist)} c) [NP1 gakusei ga] [NP3 [NP2 go-nin]] [VP tsukue o mochiageta] ⇒ NP-related FNQ: {(−part −dist), (−part +dist)} As indicated in 4), the FNQ sentence in principle allows for a range of interpretations. To provide semantic basis for this syn- tactic analysis, I will argue for a two-way distinction in the interpretation of FNQs, depending on their syntactic positions, as (4a-c) illustrate. As an alternative to the FNQ-as-adverb’s view (Gunji & Hasida, 1998; Kobuchi, 2003, 2007; Nakanishi, 2004, 2007, 2008, among others), I propose that sentences like 2) potentially have more than one syntactic structure in which the FNQ forms a constituent with the host NP (hence, an NP-related reading), while it forms a constituent with the verbal predicate (hence, a VP-adverbial reading). Syntactically speaking, example 4) is ambiguous in that it has at least three syntactic structures, as shown in (4a-c). The FNQ in 4b) lies in VP as a VP-adverb and thus functions as a VP-related quantifier (and hence, quantification is computed 5I will not take a particular position on how those constructions are best analysed syntactically. Rather, our interest is in their semantic/functional roperties, and more importantly in their use by speakers for the purpose o structuring information in discourse. Note that this is not to say that syntac- tic structure is irrelevant, but rather that it is relevant only indirectly, since syntactic information is referred to in the construction of the various pro- sodic constituents above the word level (Selkirk, 1995; Steedman,2000). The main point in the current study is that an awareness of prosodic patterns can further our understanding of the use of FNQ expressions in several wa s. 4A numeral quantifier is shown in italic and its host noun in boldface throughout the paper. The abbreviation Cl stands for classifier. The symbol // indicates a pause, corresponding to a prosodic boundary (see 8). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 88  K. YOKOTA within VP) as the above-mentioned researchers claimed. The binary features [+/−part] and [+/−dist] can exhaustively define the Japanese FNQ construction that we explore. Both partitivity and distributivity play a role in the interpretation of FNQ sen- tences; four readings in principle are expected: i) (+part, +dist); ii) (+part, −dist); iii) (−part, +dist); iv) (−part, −dist), which are indicated in the second lines of the structures, as shown in (4.1a-c) below. The quantifier in 4a) is part of (larger) NP gakusei ga san-nin “three students” constituting a single syntactic constituent. That is, it is a single nominal projection headed by a quantifier (Kamio, 1977; Yatabe, 1993; Fukushima, 2007). In particular, 4c) is newly attested and argued for in this study. The structure of 4c), which is considered a variant of 4a), is essentially the same as that of 4b) in the sense that the FNQ and its associate NP are split in morphosyntactic constituency. A notable differ- ence, however, lies in that the FNQ as in 4c) is semantically responsible for NP (i.e., object-quantifier), while the FNQ as in 4b) is for VP (i.e., event-quantifier), hence giving rise to dif- ferences in interpretation. In 4c), the subject NP presumably has been fronted (or transferred) without altering its semantic content and is thus separated from the associated FNQ (hence situated outside the same nominal projection) (see Grimshaw & Mester, 1988; Yo- kota, 1999, 2005 for further discussion of the syntactic process applicable to similar constructions). Assuming this kind of displacement (or argument transfer) in Japanese, the FNQs in 4a) and 4c) are considered arguments of the verb, taking the host noun as its own argument, which are not typically taken as adverbial, but as adnominal (i.e., quantification is calculated within the nominal domain). It follows that structural represen- tations in (4a-c) indicate that we are not talking about the same structure any more. The distinction of FNQ structures is sup- ported by prosodic data rather than what is visible in the written form. Note again that the structures of 4b) and 4c) are very similar. A plausible assumption is that without further clues in the con- text from intonation, the FNQ is likely to be associated with an unmarked interpretation (i.e., VP-related FNQs), which is counted as genuinely quantificational6. In contrast, in NP-related FNQs, this marked position for the FNQ induces a special interpretive effect, that is comparable to, a sort of “referential” reading. I will still call an NP-related FNQ one of the quantifying expres- sions, though the FNQ parallels an anaphoric pronoun on the grounds that its meaning can be analyzed in terms of quantifi- cation (see Peters and Westerståhl 2006 for an extensive dis- cussion on this matter)7. Semantically speaking, as Yoshimoto et al. (2006) discuss, the FNQ is provided an entire piece of information (e.g., fo- cus/non-focus) as an independent NP, and this may stand in an anaphoric relation to its host (Yoshimoto et al., 2006: p. 110). In particular, the NP-related FNQ appears to have an “echoic” flavour. NP-related FNQs are ambiguous between referential interpretations and existential ones (see Yokota, 2009, 2010 for a detailed discussion). If this line of analysis is correct, NP- related FNQs can be accounted for in terms of an extension of the treatment of definite descriptions (see Yokota, 2009)8. For the sake of semantic completeness, let us consider possi- ble lexical representations, as exemplified in (5a-f), in which I will employ a (silent) existential quantifier, mapped onto syn- tactic structures represented in (4a-c) above. 5) Semantic representations of 2): [NP Gakusei ga] (//) go-nin tsukue o mochiage-ta. (= 2)) student NOM five-CL desk ACC lift-Past i) “Five (of the) students lifted a desk (individually).” (Distributive) ii) “Five students lifted a desk (together).” (Non-distributive) a) ∃e([∃X: *student’(X) |X|=5])(*lift.a.desk’(e) *Ag(e)=X)) ⇒ (−p, +d) b) ∃e ([∃X: *student’(X) |X|=5](*lift.a.desk’(e) *Ag(e)=↑(X))) ⇒ (−p, −d) c) ∃e ([∃X: *student’(X)])(*lift.a.desk’(e) *Ag(e)=X |X|=5)) ⇒ (+p, +d) d) ∃e ([∃X: *student’(X)](*lift.a.desk’(e) *Ag(e)=↑(X) |X|=5)) ⇒ (+p, −d) e) ∃e ([∃X: *Ag(e)=X |X|=5 *lift.a.desk’(e)] (*Ag(e)=student’(X)) ⇒ (−p, +d) f) ∃e ([∃X: *Ag(e)=↑(X) |X|=5 *lift.a.desk’(e)] (Ag*(e)=student’↑(X)) ⇒ (−p, −d) Following Link and Landman (1989, 2000), I assume that non-distributive readings are made possible by the group op- erator “↑”. In 5), it applies first in the restriction clause, and enters into the nuclear scope (see Landman, 1989, 2000; Naka- nishi, 2004, 2007; Tancredi, 2005 for related discussion). Dis- tributive construal obtains directly entering an individual sum into the pluralized domain in the nuclear scope. The distinction between partitivity and non-partitivity is reflected in the restric- tion (i.e., nominal) contents in (5c, d) the information conveyed by the FNQ is not specified there, resulting in a partitive read- ing. Assuming that the term lift.a.desk’ takes both an individual atom and group atom, at least six possible interpretations for the FNQ construction are constructed, as listed in 5); [+part, +dist] is from 5c), [+part, −dist] from 5d), [−part, +dist] from 5a) and 5e), and [−part, −dist] from 5b) and 5f). 5a) and 5b), and 5e) and 5f) (with subject-focused readings) are constructed as NP-related FNQs, while 5c) and 5d) as VP-related FNQs. When the host NP denotes a type, the type is unspecified with respect to quantity, and partitive readings do not arise from 5b). This follows from the basic assumption that topical material cannot be interpreted in the nuclear scope of a quantifier (see, e.g., Cresti, 1995; Van Valin, 2005), which is accounted for by 5). With the architecture in place as in (5a-f), the role of dis- course-pragmatics (including intonation) is utilized to select among several readings generated by the grammar. The dis- tributive reading of the FNQ, regarded as default in previous studies, hosted by the subject NP would simply follow from the information structure of the sentence in the kinds of discourse contents that the speakers could imagine for it, rather than sorts of particular lexical semantics. In light of the discussion thus far, a preferred FNQ reading is selected (in accordance with the 6This point is further confirmed by sets of intonational data in Section 4. 7Note that this view does not mean that such an FNQ cannot be analysed differently. For instance, in terms of referentiality, the speaker may intend the FNQ to refer to the (subject) host noun when such an interpretation is available (and preferred) in the utterance. 8In the unmarked case an FNQ sentence yields an existential reading, while in the other case it is considered definite, yielding a partitive/non- artitive reading. The parallelism between NP-related FNQs and definite descriptions may also be worthy of consideration, but I have to leave it for future re- sea ch. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 89  K. YOKOTA information-structure) from a set of available readings that are captured by the semantic representations, as exemplified in (5a-f), which are accordingly calculated based on the corre- sponding syntactic structures provided in (4a-c). Prosodic Considerations We have observed two types of FNQ sentences, which gives support to the assumption that an FNQ sentence does not nec- essarily require a distributive reading (contrary to Gunji & Ha- sida, 1998; Nakanishi, 2004, 2007, 2008; Kobuchi, 2003, 2007, among others): FNQ sentences in a discourse context that clash with a distributive reading as in 2) above. This indicates that there are cases where the FNQ is clearly not part of the predi- cate but rather combines syntactically with the host noun. This section argues that the two types of FNQ sentences can be de- fined in terms of prosody. It seems that the degree of accept- ability judgment of non-distributive interpretations of FNQ sentences vary slightly among speakers, presumably because the reading is (a little) more marked in that it requires much more contextual framing to be felicitous. However, as implied above, there is indeed a natural reading of non-distributive FNQs in examples like 6) (the acceptability judgment is Nakanishi’s, based on her assumption that the dis- tributive reading is not available in FNQ sentences). Despite contextual needs for non-distributive readings, only a distribu- tive reading can be assigned to the sentence where the FNQ is located within VP, resulting in unacceptability. 6) *Kodomo ga kinoo san-nin sono inu o children NOM yesterday three-CL that dog ACC koroshita. killed “Three children killed the dog.” (Nakanishi, 2007, 2008) Miyagawa and Arikawa (2007) point out that the acceptabil- ity judgment of sentence 6) may greatly improve, if a pause is put immediately after the FNQ. The acceptability of the sen- tence clearly demonstrates that the source of the ill-formedness is not purely the syntactic and semantic issue. Their account is adequate, though it contains no explicit mention of discourse- pragmatics or intonational features. In the present prosodic-based account, taking into considera- tion that the sentence processing of FNQ sentences is largely affected by contextual factors, the acceptability of 6) with an adequate intonation can be translated to that one strategy to avoid infelicitous FNQ readings is try forming a single intona- tional domain of the FNQ and its associate NP (for instance, shaded as in Kodomo ga kinoo san-nin) as a prosodic phrase having optionally a pause or other lexical items as long as the FNQ will not exhibit a “sharp F0-rise” (but show a “down- step”), resulting in a contextually appropriate interpretation9. Due to this lowering of the phrase, a non-distributive reading obtains in 6) when the denotation of the predicate is considered a singleton, as in the predicate “kill somebody”. Sentence 6) thus asserts that the quantity of children, taken as something like a single mass entity, which can be measured out as san-nin “three-Cl”. This interpretation is plausible indeed if we take into account the Japanese noun denotation consists of both “atoms” and “sums” under Link’s (1983) theory of plurality (see also Landman, 2000 for relevant discussion). I will turn to the consideration of what prosodic structures can distinguish between distributive and non-distributive FNQ readings. By way of illustrating a sensitivity of prosodic phrase to information structure, let us now consider a set of discourse settings involving a VP-related FNQ in 7a) and an NP-related FNQ in 7b), both reflecting possible information structures10. The pitch tracks, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 below, are based on tokens produced by a male Tokyo-Japanese speaker in his late thirties who is a researcher in natural language processing at a communication technology company. Every pitch-track diagram presented in Figures 1 and 2 was picked from three to four similar diagrams of the recordings. In the recording, the speaker was presented with the accompanying context, such as (7a, b) and asked to read (aloud or silently) the context sen- tences. After reading each context sentence and understanding it, the speaker produced each target sentence for the recording. In order to minimize my own biases, I have also conducted some informal comprehension tests, presenting the recordings to over ten native speakers of Japanese, including university academic staff and undergraduate students. Figure 1. Pitch contour of the target sentence in 7a). Pitch reset is observed on the FNQ roku-nin “six-Cl”. (a) 9Downstep (or F0-compression) is the process by which pitch range is re- duced after some phonological trigger. The phenomenon occurs in many dialects of Japanese, including Tokyo Japanese, where the trigger is the HL lexical accent (see Kubozono, 1993; Ishihara, 2011 for more details). 10Although there may be other phrasing patterns reflecting possible focus structure, I will not deal with all of them for reasons of simplicity. (b) Figure 2. Pitch contours of target sentences in 7b). On both (a) and (b), the F0 peak on the subject NP is raised, and the post-focal material (i.e., roku- nin) is compressed (i.e., downstepped). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 90  K. YOKOTA To facilitate explication, the interpretations in 7a) and 7b) adopt Steedman’s (2000) informational dichotomy using theme/ rheme sentence-structure assignment, accommodating a possi- ble distribution of focus (marked by pitch accent or boundary) and background (unmarked by pitch accent or boundary) com- ponents along with possible prosodic events (e.g., downstep as shown in Figures 2(a) and (b), and pitch reset as in Figure 1). The question sentences in 7) are generally assumed to unambi- guously specify the information structure and the placement of prosodic prominence pertaining to the FNQ sentence (see Sel- kirk, 1996; Kahnemuyipour, 2009 for relevant discussions). It should be noted that the contextual question sentences were given in English because it is reported that listeners” judgments are influenced by the degree of F0 height of the question word itself, i.e., the focused wh-word (see Maekawa, 1991 for discus- sion of this matter). 7) (Single prosodic units are indicated by shade. “!” and “↓” indicate a pitch reset and downstep, respectively. Each [’] in the sentences marks the place for the HL fall of a pitch accent.) a) Q: I heard that some men who happened to be there got involved in terrorism. But how many people got involved in it? A: Soko-ni iawáseta otokó ga // men who happened to be there NOM [Theme Focus ] !rokú-nin téro ni makikomáreta. six-CL in te rrorism got inv olved pitch reset [Rheme Focus ...] “Six (of the) men who happened to be there got involved in terrorism.” Sentence 7a) presupposes the existence of only one terrorism (or more than one terrorism), one for each man, which does not matter in the present discussion. More importantly, an FNQ sentence can be assigned either distributive or non-distributive. The pitch-tracking in Figures 1 and 2 illustrates that a promi- nent accent induces downstep and suppresses the lexical accent of the predicate that immediately follows it. It is noteworthy that in the answer sentence 7b), the subject NP is focused and the FNQ roku-nin “six-Cl” denotes maximality. As indicated on both contours in Figure 2, the FNQ is phrased prosodically with the preceding host noun rather than with the VP, though the sentence can be ambiguous with respect to information structure: that is, the FNQ roku-nin are grouped either a rheme- background or a theme-focus, which certainly affects the into- national tune, as can be seen in Figures 2(a) and (b). 7) b) Q: I heard that six people got involved in terrorism. But who was it that got involved in it? A: Soko-ni iawáseta otokó ga (//) men who happened to be there NOM (//) [Rheme Focus] ↓rokú-nin téro ni makikomáreta. six-CL in terrorism got involved downstep i) [Rheme Background] [Theme Focus ...] or ii) [Theme Focus …] “Six men who happened to be there got involved in terror- ism.” As already discussed earlier, the target sentence in 7b) quan- tifies over individuals, which is perfectly well-formed despite the presence of a pause (see Figure 2(a)). When it comes to FNQs that quantify over individuals, it is not clear how well the previous studies apply to them, assuming the subject-oriented FNQ must form a constituent with the VP. It cannot be claimed that such quantification obligatorily arises with all FNQs, be- cause this would falsely predict that sentences like Gakusei ga, gojuu-nin atsumatta “Fifty students gathered” are just as ill- formed as sentences like #Otoko ga, san-nin Taknaka o kor- oshita “Three men killed Tanaka” (Kobuchi, 2007: p. 110). It is worth mentioning here that the data also shows that the as- sumption by Takami (1998) that in the FNQ construction the host NP must be topic in the sentence is not correct. Note par- ticularly that a pause intervenes between the FNQ and its host NP in 7b ii), where a new independent pitch range has not been chosen at the intermediate phrase boundary before the FNQ; hence the two items are phrased together, consisting of a single intonational domain. To account for the distinctive pitch patterns as displayed in Figures 1 and 2, I assume two levels of prosodic phrasing: Accentual Phrase (AccP) and Intermediate Phrase (IntP). To recapitulate, as observed in (8a-c) there are (at least) three dis- tinct prosodic patterns with FNQs regarding narrow focus readings (8a-c). 8) a) [IntP [AccP otoko ga roku-nin]] = NP-related FNQ (e.g., 7) b.i)) b) [Int P [AccP otoko ga] [AccP roku-nin]] = NP-related FNQ (e.g., 7) b.ii)) c) [IntP [AccP otoko ga]] [IntP [AccP roku-nin]] = VP-related FNQ (e.g., 7) a)) The current view is compatible with the assumption that Japanese FNQs function either as NP-related in (8a, b), or as VP-related as in 8c). In regard to NP-related FNQs, the (partial) utterance in 8a) does not necessarily include a pause, so there is no separate boundary tone, whereas the one in 8b) does. The point to observe is that the partition of the sentence in 8) into the verb phrase and a non-standard (but interpreted) constituent, [Subject NP, FNQ], corresponding to the string otoko ga roku- nin “six men”, makes this prosody-based view structurally and semantically suited to the demands of intonational phrasing observed in FNQ constructions. It is highly likely that speakers might group the prosodic words for the NP-related FNQ in each utterance into two accentual phrases, as in shown in 8b), which, in turn, were grouped together to form a single IntP for the utterance as a whole, as in 8a). In contrast, for the utterance involving VP-related FNQs, the tone structure looks like 8c). The accentual phrase (AccP) consists of one or more word. An intermediate phrase (IntP) is a phonological unit that con- sists of one or more AccP. Tonally, it is the domain within which pitch range is specified and downstep takes place; it is also characterized by an optional phrase-final tonal movement (IntP-boundary tone) (see Pierrehumbert & Beckman, 1988 for details). I suggest treating the boundary tones of 7b) (see Fig- ures 2(a) and (b)) as an AccP-boundary tone (rather than IP- boundary tone as in 7a)), as it does not seem to be generally followed by pitch-resetting or a (long) pause (see Venditti et al., 2008 for details). Given this prosody, 7b) can be analyzed ei- ther as a single AccP formed by the host NP and the FNQ (Figure 2(a)) or separate APs by the host NP and the FNQ Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 91  K. YOKOTA (Figure 2(b)). Hence, this example can be analyzed as a “con- tinuation-fall” contour, presumably reflecting the speaker’s in- tentions with regard to the theme-rheme articulation of his/her utterance (Ladd, 1996). Importantly, Figure 2(b) shows that the syntax does not determine the intonational contour unambigu- ously. The pause observed in the Figure 2(b) is presumably treated as an AccP-boundary tone rather than IntP-boundary tone, as it does not seem to be generally followed by pitch- resetting or a (long) pause (Oshima, 2007; Venditti et al., 2008). In this connection, the difference in phrasing seems insensitive to the edges of major syntactic phrases, but rather to a level difference (e.g., a high level of the prosodic hierarchy), as can be seen in 8) of whether or not the FNQ belongs to the same prosodic unit as the subject NP it is modifying. We can main- tain that FNQ placement and interpretation is affected by pros- ody (e.g., Selkirk, 1995), and the types of prosodic boundary vary in reference to prosodic phrasing (e.g., AccP-boundary or IntP-boundary). To recapitulate, the contours observed in Figures 1 and 2 should be explained if we assume that if accentual phrasing in Japanese tends to reflect both the discourse context and the syntactic structure of an utterance. This account is consistent with the standard assumption that the focal prominence typi- cally introduces an IntP break before the focused element (Pi- errehumbert & Beckman, 1986; Nagahara, 1994, among others), the speaker can induce the percept of focal prominence even with a (fairly small) reset at the beginning of the focused ele- ment as in 7a), and the sequence the host NP and the FNQ can be marked as a syntactically conjoined sequence by the intona- tion pattern, as shown in the downsloping pattern in the figures of 7b). Examples such as 7a) and 7b ii) exemplifies a way in which the prosodic parse may be ambiguous; the segmental cues and intonation pattern inform the listener that these forms are very closely conjoined syntactically, but the IP-boundary in 7a) indicates that the two elements of the constituent are inde- pendent, so that the second or the first of them can be marked separately as a focus constituent. The descriptive generalization that follows is that NP-related FNQs can only get a contextually appropriate interpretation if they can have the F0 peak on the FNQ lowered (or compressed). Thus, in actual speech, information structure is reflected in changes in pitch register scaling (e.g., downstep or pitch reset) of prosodic domains (see Féry & Ishihara, 2009 for an exten- sive discussion). Crucially, this is different from the claim that the presence of a prosodic boundary affects the semantic inter- pretation: It is true that the different interpretations are often explained by ascribing to the insertion of a prosodic boundary (see Pierrehumbert & Beckman, 1988; Kubozono, 1993, and references therein). However, it is not sufficient, as Figure 2(b) (in which a pause is inserted between the subject and FNQ) exhibits a distinctive prosodic event involved in the construc- tion: an initial F0 compression after the prosodic boundary. The point of the discussion so far is that the partition of the sentence in Figure 2(b) into the verb phrase and a seemingly non-canonical (but fully interpreted) constituent; [Subject NP, FNQ] corresponding to the string otoko ga roku-nin “men six- Cl” makes this theory structurally and semantically suited to the demand of intonational phrasing. Taking into account that in- tonation helps to determine which of the multiple possible phrasing permitted by syntax of Japanese is intended, and that the interpretations of the constituents that arise from these phrasing patterns are closely related to the distinction between focus and non-focus. Any syntactic theory capturing FNQ con- strual should be more sensitive to the presence of intonational boundaries in actual speech (i.e., whether or not they coincide with syntactic boundaries when intonation boundaries are pre- sent), making it possible to describe two types of FNQs; NP- related as in 7b) and as VP-related as in 7a). Conclusion I finish the discussion in this paper by summarizing the main points. First, I have shown that the difference in intonational phrasing crucially lies in the information structure. I have em- phasized that in light of information structure, focus emerges as part of the interpretation of Japanese FNQs. Second, it has been demonstrated that in terms of the information-based prosody, local NP-related FNQs 4a) and non-local NP-related ones 4c) can be substantially identical if an FNQ consists of a single intonational phrase (or prosodic constituent) with the host NP, despite the difference in the surface structure (or syntactic con- stituent). This hypothesis has been ascertained by empirical evidence in 7a) and 7b). Although the exact implementation remains to be worked out, there is a correlation between pro- sodic phrasing and interpretation such that each phonetic reali- zation (e.g., distinctive pitch patterns) as a consequence of in- formation partitioning which serves to determine the preferred FNQ interpretation in a given discourse. This line of analysis is consistent with the assumption that surface structure with into- nation is the one that can be directly interpreted in terms of semantics and pragmatics (e.g., information-structure). I hope this paper suggests a fruitful direction for future studies on FNQ constructions in Japanese. REFERENCES Féry, C., & Ishihara, S. (2009). How focus and givenness shape pros- ody. In M. Zimmerman, & C. Féry (Eds.), Information structure (pp. 36-63). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Fitzpatrick, J. (2006). The syntactic and semantic roots on floating quantification. Doctoral Dissertation, Cambridge: MIT. Fodor, J. (2002). Prosodic disambiguation in silent reading. In M. Hiro- tani (Ed.), Proceedings of NELS 32 (pp. 113-132). Amherst: GLSA Publications. Fujita, N. (1994). On the nature of modification: A study of floating quantifiers and related constructions. Doctoral Dissertation, Roch- ester: University of Rochester. Gunji, T., & Hasida, K. (1998). Measurement and quantification. In T. Gunji, & K. Hasida (Eds.), Topics in constraint-based grammar of Japanese (pp. 39-79). Amsterdam: Kluwer. Ishihara, S. (2011). Japanese focus revisited: Freeing focus from pro- sodic phrasing. Lingua, 121, 1870-1889. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2011.06.008 Ishii, Y. (1998). Floating quantifiers in Japanese: NP quantifiers, VP quantifiers, or both? Researching and Verifying an Advanced Theory of Human Language, 2, 149-171. Ishii, Y. (1999). A Note on floating quantifiers in Japanese. In M. Mu- raki, & E. Iwamoto, (Eds.), Linguistics: In Search of the Human Mind.—A festschrift for Kazuko Inoue (pp. 236-267). Tokyo: Kaita- kusha. Kitagawa, Y., & Kuroda, S. (1992). Passives in Japanese. Master’s Thesis, San Diego: University of Rochester and University of Cali- fornia. Kitagawa, Y., & Fodor, J. D. (2006). Prosodic influence on syntactic judgments. In G. Fanselow, C. Fery, R. Vogel, & M. Schlesewsky (Eds.), Gradience in grammar (pp. 336-358). Oxford: Oxford Uni- versity Press. Kobuchi, M. P. (2003). Distributivity and the Japanese floating quanti- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 92  K. YOKOTA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 93 fier. Doctoral Dissertation, New York: The City University of New York. Kobuchi, M. P. (2007). Floating numerals and floating quantifiers. Lingua, 117, 814-831. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2006.03.008 Kubozono, H. (1993). The organization of Japanese prosody. Kuroshio Publishers. Ladd, R. (1996). Intonational phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press. Maekawa, K. (1991). Perception of intonational characteristics of wh and non-wh questions in Tokyo Japanese. In Proceedings of the In- ternational Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS) (pp. 202-205). Provence, France: Université de Provence. Miyagawa, S., & Arikawa, K. (2007). Locality in syntax and floating numeral quantifiers. Linguistic Inquiry, 38, 645-670. doi:10.1162/ling.2007.38.4.645 Nagahara, H. (2004). Phonological phrasing in Japanese. Doctoral Dissertation, Los Angeles: University of California. Nakanishi, K. (2004). Event quantification and distributivity. Philadel- phia: University of Pennsylvania. Nakanishi, K. (2007). Formal properties of measurement constructions. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Nakanishi, K. (2008). The syntax and semantics of floating numeral quantifiers. In S. Miyagawa, & M. Saito (Eds.), The Oxford hand- book of Japanese linguistics (pp. 287-319). Oxford: Oxford Univer- sity Press. Oshima, D. Y. (2007). Boundary tones or prominent particles? Varia- tion in Japanese focus marking contours. Berkeley Linguistics So- ciety (BLS), 31, 453-464. Pierrehumbert, J. B., & Beckman, M. E. (1988). Japanese Tone Struc- ture. MA: MIT Press. Selkirk, E. (1995). Sentence prosody: Intonation, stress and phrasing. In J. A. Goldsmith (Ed.), The handbook of phonological theory (pp. 550-569). Oxford: Blackwell. Selkirk, E., & Tateishi, K. (1991). Syntax and downstep in Japanese. In C. Georgopoulos, & R. Ishihara (Eds.), Interdisciplinary approaches to language: Essays in honor of S.-Y. Kuroda (pp. 519-543). Am- sterdam: Kluwer. Steedman, M. (2000). The syntactic process. MA: MIT Press. Sugahara, M. (2003). Downtrends and post-focus intonation in Japa- nese. Doctoral Dissertation, Amherst: University of Massachusetts. Takami, K. (1998). Nihongo no suuryooshi yuuri ni tsuite: Kinooron- teki bunseki [On quantifier floating in Japanese: A functional analy- sis]. Gekkan gengo [Language] 27(1), 86-95; 27(2), 86-95; 27(3), 98-107. Tokyo: Taishukan. Tancredi, C. (2005). Plural predicates and quantifiers. In N. Imanishi (Ed.), Gengo kenkyuu no uchuu [The World of linguistic research: A Festschrift for Kinsuke Hasegawa on the occasion of his seventieth birthday] (pp. 14-28). Tokyo: Kaitakusha. Venditti, J. J., Maekawa, K., & Beckman, M. E. (2008). Prominence marking in the Japanese intonation system. In S. Miyagawa, & M. Saito (Eds.), Handbook of Japanese linguistics (pp. 458-514). Ox- ford: Oxford University Press. Yamamori, Y. (2006). Nihongo no genryoo hyoogen no kenkyuu. To- kyo: Kazama shoboo. Yokota, K. (2009). On numeral floating quantifier in Japanese. In H. Hoshi (Ed.), The Dynamics of the language faculty: Perspectives from linguistics and cognitive neuroscience (pp. 85-109). Tokyo: Kuroshio Publishers. Yokota, K. (2010). Prosody and quantifier float. In S. Pogodalla (Ed.), Actes des 8 èmes journées sémantique et modélisation (pp. 49-51). Nancy: INRIA Nancy-Grand Est. Yoshimoto, K. et al. (2006). Processing of information structure and floating quantifiers in Japanese. In T. Washio et al. (Eds.), JSAI 2005 Workshops, LNAI 4012 (pp. 103-110). New York: Springer-Verlag.

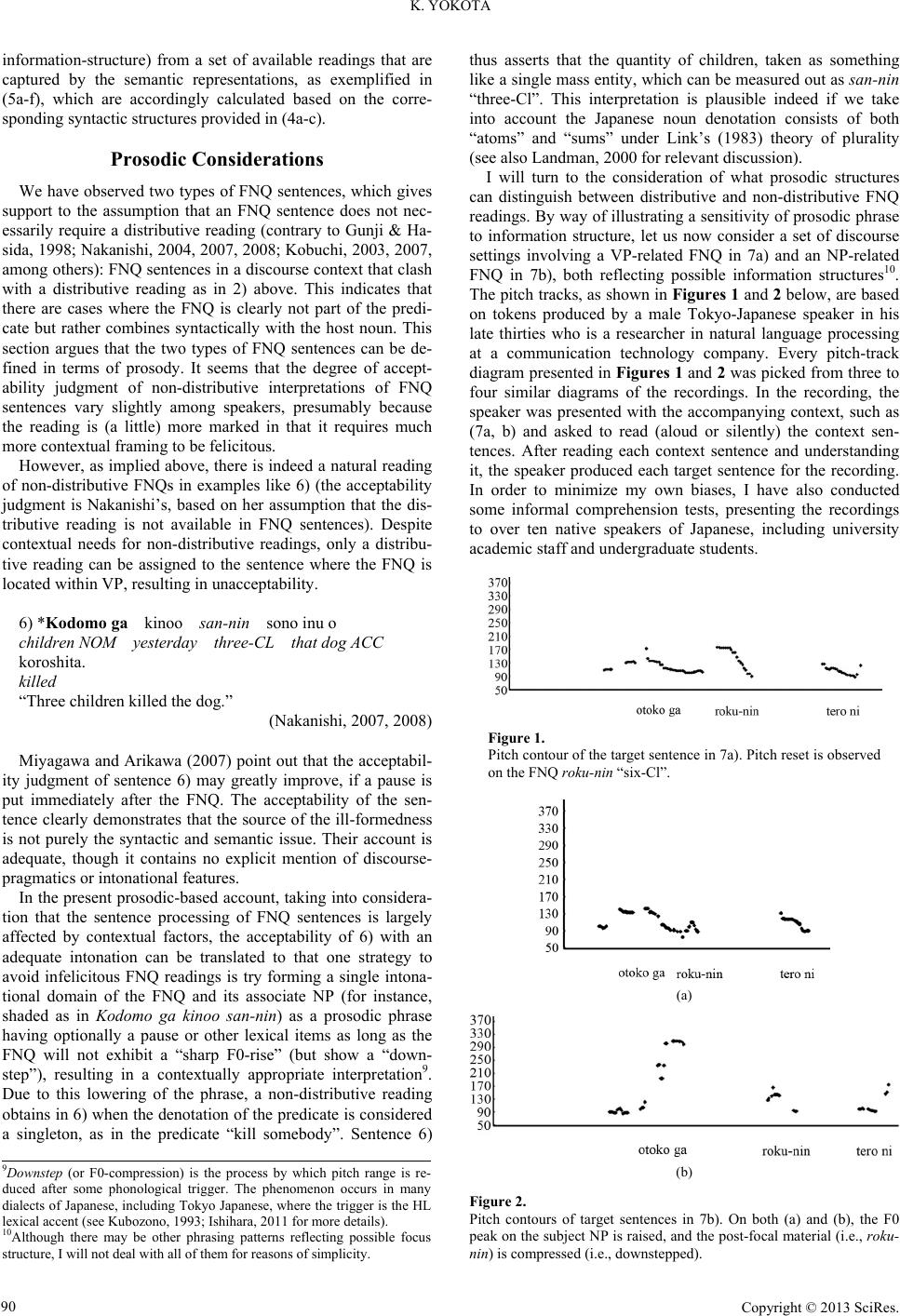

|