Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 58-68 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.31007 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 58 Spelling Errors’ Analysis of Regular and Dyslexic Bilingual Arabic-English Students Salim Abu-Rabia, Rana Sammour Faculty of Education, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel Email: Salimar@construct.haifa.ac.il Received September 3rd, 2012; revised November 12th, 2012; accepted November 20th, 2012 The present study is an investigation of spelling errors of 8th grade dyslexic students (n = 20) and a group of 5th and 6th graders (n = 21) matched to the dyslexic group according to their spelling level. All students were tested on spelling isolated words in Arabic and English. The spelling errors were classified into four categories: phonetic, semiphonetic, dysphonetic, and word omissions. The results of the present study re- vealed that phonetic errors were more prevalent in Arabic than in English, while semiphonetic errors were more prevalent in English than in Arabic. Furthermore, the dyslexic group made significantly more semi- phonetic errors in Arabic than the spelling-level matched group, while the two groups made a similar number of semiphonetic errors in English. The discussion attempts to clarify and explain the results by analyzing the specific features in Arabic and English that posed difficulty for the dyslexic and regular Arab students. A number of instructional recommendations regarding the teaching of English spelling to Arabic speakers are presented. Keywords: Bilingualism; Arabic; English; Spelling Error Analysis; Phonetic Errors; Semiphonetic Errors; Dyslexic Readers Introduction Successful English spelling performance involves the proc- esses of segmenting the spoken word into its phonemic com- ponents and then selecting the appropriate graphemes to repre- sent the phonemes. In addition, it entails learning a large num- ber of letter combination rules (orthography) and many excep- tions due to affixation, assimilation, and the inflow of new words (morphology) to the language (Varnhagen, McCallum, & Burstow, 1997). A great deal of research on spelling development supports the idea that the phonological, orthographic, and morphological knowledge and strategies that children acquire follow a se- quence of stages that are characterized according to the pre- dominant information and strategies used during that stage of development (e.g. Ehri, 1986; Frith, 1980; Gentry, 1982; Hen- derson, 1985). Gentry (1982) proposed the existence of five stages of spelling development. In the first, precommunicative stage, children combine letters and letter-like symbols in a rela- tively random manner. In the second semiphonetic stage, chil- dren represent part of the phonetic information in the word. In the phonetic stage, children systematically develop knowledge of letter-sound correspondence. In the transitional stage, chil- dren demonstrate their knowledge of English orthography in addition to their beginning understanding of the manner in which morphological information affects spelling. According to Gentry (1982), children reach the correct stage of spelling when they master the phonological, orthographic, and morphemic aspects of their written vocabulary. More recent analyses of spelling development are adding to and modifying stage approaches, putting an emphasis on the child’s employment of diverse strategies and various types of knowledge in spelling (Ehri, 1992; Rittle-Johnson & Siegler, 1999; Treiman & Bourassa, 2000; Treiman & Cassar, 1997; Varnhagen et al., 1997). Ehri (1992) argued that the stages of spelling development may be better defined in terms of sets of features rather than individual features. Varnhagen et al. (1997) conducted a study to examine whether children’s spelling de- velopment proceeds through a series of stages, as described by scholars. They argued that if spelling development can be characterized by stages, then it should be possible to observe qualitative differences in children’s spelling at different devel- opmental stages, as well as consistency in spelling within a certain stage of development. They also analyzed the spelling patterns for silent -e long vowel words and past tense mor- pheme -ed words, but did not find significant qualitative dif- ferences between first and sixth graders. Further, they showed that children of the same age group were not consistent in their spelling. Varnhagen et al. (1997) concluded that the develop- ment of children’s spelling ability at elementary school grades cannot be adequately characterized by developmental stages. Rather, children use a variety of sources of knowledge and stra- tegies in their spelling performance from a very early age. Understanding the process of spelling development is mostly based on observations of children’s spelling errors (Varnhagen et al., 1997). These errors provide interesting insights on the ways children conceive the sound and spelling system of the English language (Stage & Wagner, 1992). Error analysis has been used to infer previous knowledge and cognitive strategies that children may have employed in their spelling. It has also yielded ample information as to children’s phonological, ortho- graphic and morphological knowledge and the way they may use their knowledge in order to translate oral language into a written form (Read, 1975; Treiman, 1993). Further, error analysis has been used to identify learning disabilities; acquired and developmental dyslexia in both children and adults have been  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR diagnosed based on error patterns (Goldsmith-Phillip, 1994; Temple & Marshall, 1983). The present study aims to examine and analyze the types of spelling errors made by regular and dyslexic Arab students in Arabic as a first language (L1) and English as a foreign lan- guage (FL). Review of the Literature The Arabic Writing System Arabic is an alphabetic orthography that contains 28 conso- nantal letters, and it is written and read from right to left. Most of the Arabic letters have more than one written form, depend- ing on their position in the word. However, the essential shape of the letter is maintained in all cases (Abd El-Minem, 1987). In addition, the letters of the alphabet can be categorized on the basis of shared basic forms, and can be distinguished from each other by the number (one, two or three) and position (in, on or under the letter) of the dots, or their absence. Arabic has two forms: literary Arabic (also known as Mod- ern Standard Arabic) and non-standard spoken Arabic. Literary Arabic is taught at school along with instruction in reading and writing and is used all over the Arab world for writing and for- mal communication purposes, whereas spoken Arabic is a local dialect that has no written form. Actually, the spoken dialect is the native language of all native speakers of Arabic. However, each Arab country (or people) has a different local spoken dia- lect (or dialects). In spite of sharing a limited group of words, the two forms of Arabic are phonologically, morphologically, and syntactically different (Eviatar & Ibrahim, 2000). The Arabic language has three short vowels depicted by dia- critical marks placed beneath or above the letter. The short vowels are: 1) Fatha—a short diagonal stroke above the letter (e.g. /da/). 2) Damma—the sign above the letter (e.g. /du/). 3) Kasra—a short diagonal stroke below the letter (e.g. /di/). Arabic has also three long vowels represented by the letters Alif (e.g. /d/), Waw (e.g. /d/) and Ya (e.g. /d/). In the vowelized version of the Arabic orthography, both consonants and vowels (short and long) are represented. In the nonvowelized version, on the other hand, the diacritical marks are omitted and only the consonants and long vowels are repre- sented. This version is used in most reading materials and texts, except in reading and writing instruction, in children’s books, in the Koran, in dictionaries, and some literary materials, where the vowelized version is used. Skilled readers are expected to read texts without short vowels and use contextual clues in order to fill in the missing vowels. Reading accuracy in Arabic requires vowelizing word endings according to their grammati- cal function in the sentence, which entails an advanced phono- logical and syntactical ability (Abu-Rabia, 2001). In Arabic, as in other Semitic languages, words are con- structed by combining a root and a word pattern. This morpho- logical structure is nonlinear and constructed by interdigitating the root consonants in their designated sites in the pattern. The roots are generally triliteral or quadrilateral, that is, consisting of three or four consonants, and they carry most of the semantic information of the words. The word patterns include vowels as well as consonants and provide information about the word class and its morphological status, in addition to the complete structure of the word. Therefore, content words in Arabic are at least bi-morphemic, but none of these morphemes are words by themselves (Ibrahim, 2006). The second type of morphological structure is linear and constructed by attaching prefixes and suffixes to real words. Most grammatical markings of number, gender and person on nouns, adjectives and verbs are expressed linearly. The Status of Vowels in Arabic and English As mentioned before, short vowels in Arabic are typically omitted from written texts and can easily be filled in by skilled readers. Skilled readers use contextual clues to fill in the miss- ing vowels as they typically represent grammatical information (e.g. part of speech, person, number, tense, and voice) that can be inferred from the semantic and syntactic context and would often be redundant if presented in writing. The lack of short vowel information in Arabic texts is probably permissible be- cause short vowel patterns are highly predictable based on con- textual information (Abu-Rabia & Taha, 2004; Hayes-Harb, 2006; Taouk & Coltheart, 2004). In contrast, the overt representation of vowels is vital to Eng- lish written word processing since changing one vowel in an English word often changes the meaning of the word entirely. Therefore, in English, vowel letters provide important informa- tion for distinguishing lexical items and are not predictable based on grammatical function, as they are often in Arabic. A related difference is that in English, words with similar conso- nant structures are often not semantically related. Given these differences between the English and Arabic orthographies, the written word identification processes used by readers of English and Arabic differ in their degree of dependence on written vowel information. Since Arab readers were found to be less aware of and devote less visual attention to vowel letters rela- tive to consonants when reading English texts (Hayes-Harb, 2006; Ryan & Meara, 1991), they are expected to be less aware of vowel letters, and consequently, under-represent them in writing as well. Spelling Errors in Arabic In Arabic, few studies have analyzed the spelling errors of normal and disabled readers. Azzam (1993) examined the spell- ing errors made by children learning Arabic, aged 6 to 11 years. The spelling errors were analyzed and classified according to categories derived from linguistic and orthographic features of the Arabic script. The results showed that the misspellings of Arabic speaking children persisted through primary school, pointing to the difficulties involved in mastering the Arabic written language. The spelling errors centered around context sensitive rules, additions and omissions of letters. Abu-Rabia and Taha (2004) investigated the spelling errors of 5th grade dyslexic Arabic readers compared with age- matched and reading-level-matched young normal readers. Their spelling errors were classified into seven categories: phonetic errors, semiphonetic errors, dysphonetic errors, visual letter confusion, irregular spelling rules, word omission and func- tional word omission. Abu-Rabia and Taha (2004) found that the spelling error profiles of the dyslexic group were similar to those of the reading-level-matched group in both percentage and quality. The analysis of the spelling errors revealed that the most prominent type of spelling errors was phonetic. In addi- tion, they found that the nature of the Arabic orthography contributed to the types of spelling errors made by the different Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 59  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR groups. Based on the same spelling error categories, Abu-Rabia and Taha (2006) investigated the spelling error profiles of Ara- bic speaking students in grades 1 - 9. The results indicated that phonological spelling errors predominated in all grades over other error categories and represented 50% of the total errors. The researchers explained their finding by arguing that the phonological stage of spelling in Arabic does not end, even at grade 9, and that spellers find it difficult to pass from this stage to a more advanced level, the orthographic stage. They con- cluded that phonology poses the greatest challenge to students developing spelling skills in Arabic. Spelling Errors in English In English, as opposed to Arabic, the spelling patterns of normal and disabled readers have been widely investigated (Bruck, 1988; Carlisle, 1987; Moats, 1983, 1996) These studies reported that spelling errors of individuals with dyslexia are similar to those of younger children. Nelson (1980) analyzed the spelling errors of dyslexic and normal spelling-level-matched children and classified their errors into three categories: order errors, phonetically inaccurate er- rors, and orthographically illegal errors. In both groups, more phonetically inaccurate misspellings were made than either of the other two error types. Also, there was no significant differ- ence between the groups in the frequency of the three error types, which indicates that the quality of the dyslexic children’s spelling is essentially normal. Moats (1996) analyzed the spell- ing errors of adolescent dyslexic students. She divided the er- rors into three categories: orthographic errors—those that used the wrong symbol but that represented the speech sounds in some plausible manner (e.g. homophones), phonological errors— omissions, substitutions, additions, or errors in the way speech sounds were represented, and morphophonological error s—er- rors that occurred on inflected morphemes. She found that the poorer spellers made more errors than the better spellers on certain phonological and morphophpnological constructions. Specifically, the poorer spellers made a disproportionately large numbers of errors in their representation of liquid and nasal consonants, especially after vowels, and in their spellings of the inflections -ed and -s. Snowling, Goulandris, and Defty (1996) investigated the de- velopment of literacy skills among dyslexic children compared to reading age controls and chronological age controls. Their spelling errors were analyzed and classified into three catego- ries: first, phonetic errors—these errors were caused by the in- appropriate application of letter-sound correspondence rules (e.g. cigarette-sigaret). Second, semiphonetic errors—these er- rors contain a single phonemic error and could be created by omission of a single phoneme, addition of a phoneme and sub- stitution of one phoneme with a similar one. Third, dysphonetic errors—all other errors that did not represent the sound struc- ture of the word correctly (e.g. million-miyel). The research- ers found dysphonetic errors to be prominent among dyslexic children, suggesting that they had problems with the use of phonological spelling strategies, and they attributed this to a phonological delay. Transfer of L1 Skills to L2 The effects of first language (L1) on second language (L2) learning have been extensively investigated in the past few decades (Akamatsu, 1999, 2003; Brown & Haynes, 1985; Fender, 2003; Hakuta, 1976; Koda, 1988, 1990). Some studies used correlational analyses of ESL (or EFL) learners’ L1 skills and English literacy skills to investigate L1 influence. For example, Abu-Rabia and Siegel (2002) examined the language skills in three different orthographies, Arabic, Hebrew and English, among native Arabic speakers. They found that several L1 skills, including reading, phonological and orthographic proc- essing, working memory and spelling, correlated with English spelling. Other studies compared the literacy skills of ESL learners from different L1 backgrounds. For example, Koda (1988) in- vestigated the effects of L1 orthographic structures on cognitive processes involved in L2 reading. Experiment 1 tested the ef- fects of blocking either visual or sound information on lexical decision-making among four groups (Arabic, English, Japan- ese, and Spanish), whereas experiment 2 examined the effects of visual confusability, by using heterographic homophones (e.g. eight and ate), on reading comprehension among the same four groups. The two experiments demonstrated that L1 ortho- graphic structure exerts a significant effect on cognitive proc- esses in L2 reading, and suggested that cognitive process trans- fer occurs in L2 reading. Hayes-Harb (2006) conducted a study to determine whether native Arabic speakers approach English texts with written word identification strategies that reflect the nature of their native Arabic writing system. Specifically, she investigated whether native Arabic speakers devote less visual attention to vowels when reading English texts than speakers of other languages. In experiment 2, three groups (native Arabic speakers learning ESL, ESL learners with L1 backgrounds other than Arabic, and native English speakers) were given a letter detection task and were asked to identify all instances of a target letter while reading a text for comprehension. She found that native Arabic speakers exhibited less accurate detection of vowels relative to consonants than either of the other two groups. According to Hayes-Harb, a possible explanation for this finding may be that the relatively less prominent role of written vowel information in Arabic reading was transferred to English letter and word processing, resulting in the higher rela- tive rate of vowel detection errors for native Arabic speakers. This finding also shows that native Arabic speakers transfer visual word-processing strategies from Arabic to reading in English. Koda (1995) concluded that the native language or- thography influenced the strategies employed in L2 reading, adding that the transfer of strategies from an L1 may cause difficulties for readers when L1 and L2 have different orthog- raphies. To explain the relation between proficiency in L1 and L2, Cummins (1979) suggested the Interdependence Hypothesis (IH), which holds that L2 competence of an academic skill is partially related to L1 competence at the time L2 is being ac- quired. For instance, an ESL learner with a good spelling ability who has had several years of formal instruction in his/her L1, may have sufficient knowledge of L1 norms on which to draw upon when beginning to spell in English. On the other hand, an ESL learner who struggles with spelling and has underdevel- oped phonological and orthographic processing skills may not benefit as much from L2 transfer (Figueredo, 2006). In addition, Cummins (1981) maintained that academic skills, such as spell- ing, share an underlying proficiency across languages, even though the surface aspects of each language, such as orthogra- phy, may differ. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 60  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 61 In sum, the results of the studies mentioned previously showed that L1 orthographic features affect L2 literacy skills. Thus, it seems that in learning a second language, the nature of L1 as well as L2 orthographies play a major role in the learning proc- ess. Therefore, in the present study, the English spelling errors performed by native Arabic speakers are expected to be influ- enced by the Arabic orthography. According to the Linguistic Coding Differences Hypothesis (LCDH) suggested by Sparks and Ganschow (1991), successful FL learning is founded upon phonological, orthographic and syntactic skills in the native language. A second assumption, based on the first, is that FL failure is founded upon native language deficits (Miller-Guron & Lundberg, 2000). Studies conducted recently by Ganschow and Sparks strongly suggest that the difficulties experienced by poor FL learners are a con- sequence of weak native language skills (Ganschow, Sparks, & Schmeider, 1995). Thus, it seems as if native language weak- nesses, including dyslexia, impede the development of FL pro- ficiency. The present research compares the spelling errors of dyslexic Arab students with age-matched and spelling-level-matched regular students in two different orthographies: Arabic and English. Spelling errors’ analysis of dyslexic and regular read- ers in Arabic and English will shed light on the nature of the learning process of L1 as well as FL, respectively, among the different groups. On the grounds of the above literary review, it was hypothe- sized that: 1) The spelling errors in Arabic and English would reflect the nature of the corresponding orthography; however, the errors in English would be influenced by the Arabic orthography as well. 2) The dyslexic group and the spelling-level-matched group would show similar errors. Method Participants Sixty one students were screened out of a total of 167 who participated in this study: 20 8th grade dyslexic students, 20 8th grade regular students matched to the dyslexic group according to their age, and 21 young regular students, who were matched to the dyslexic group according to their spelling level. The stu- dents were sampled from a private school in Haifa, Israel. They were native speakers of Arabic, and most of them came from a medium socio-economic status. Bilingual students or those whose mother tongue is not Arabic were excluded from the study. The dyslexic group (14 boys and 6 girls) consisted of 8th graders who studied in a special class for disabled learners, and whose spelling level was in the 30th percentile or below, ac- cording to the Initial Spelling Test. In addition, the usual exclu- sionary criteria were applied: None of the dyslexic children had serious language impairment or a primary emotional distur- bance. They had normal hearing and vision abilities and at- tended school regularly. Their mean age was 13.58, with a standard deviation of .33. The age-matched group (13 girls and 7 boys) consisted of 8th grade students whose spelling level was in the 70th percentile or above in the Initial Spelling Test. Their mean age was 13.53, with a standard deviation of .29. The spelling-level-matched group (10 girls and 11 boys) in- cluded regular 5th and 6th grade students who matched the dys- lexic group on spelling level, which was determined according to their performance on the Initial Spelling Test. Their mean age was 11.34, with a standard deviation of .54. As shown in Table 1, there was no significant difference between the dys- lexic and the spelling-level-matched group on spelling accuracy. Nonetheless, the difference between the dyslexic and the age- matched group on the same task was significant. Materials There were a total of five basic measures. The first one—Ini- tial Spelling Test—was used to select the three groups, and the other four were used to validate the eighth graders’ division into regular and dyslexic students. Additionally, two spelling tests were administered: one in Arabic and the other in English. All tests were built especially for this study. Basic Measures Initial Spelling Test. A list of words from the basal reader of the 8th grade was used to determine the spelling level of the participants by testing their spelling accuracy. It consisted of 40 words with gradually increasing difficulty in terms of fre- quency, word length, and morphological complexity, and in- cluded elements that were likely to pose difficulty for students such as spelling rules and homophonous letters The participants were required to write short vowels at word endings ( = .82). Table 1. Means and standard deviations of all groups on the different basic measures. Basic measures Dyslexic Age-matched Spelling-level-matched M SD M SD M SD Initial spelling 26.25 4.55 36.35 1.81 28.05 2.36 Letter naming 30.45 5.38 25.95 4.31 - - Number naming 20.45 2.37 18.25 2.95 - - Phonological awareness 14.05 2.67 17.8 2.42 - - Pseudoword reading accuracy 16.9 5.64 24 5.73 - - Pseudoword reading speed 84.35 24.86 59.95 12.35 - - Word reading accuracy 32.2 4.11 35.95 2.06 - - Word reading speed 64.9 17.51 40.5 8.63 - - Note: Dashes indicate that the task was not administered to this group.  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR Error Analysis Phonological Awareness Test. Phonological awareness was measured by a phoneme deletion test. Participants were orally presented with a word and then asked to delete a single pho- neme from the beginning, middle, or end of it (e.g. ketab with- out /k/ is etab). This task consisted of 20 items ( = .80). Rapid Automatized Naming. Rapid Letter-Naming and Rapid Number-Naming Tests were administered. In both Rapid Nam- ing Tests, five rows of five letters/digits were presented to the participants. The five letters/digits in each row were arranged in different orders. Participants were required to name all the let- ters or digits in the corresponding task at the fastest possible speed. Given the very few errors made on these tasks, error rates were not included in the analyses. Reading Pseudowords. A list of 30 vowelized pseudowords was used in order to assess the participants’ phonemic decoding efficiency. The pseudowords were constructed by incorporating unreal roots that do not exist in Arabic into real word patterns. The pseudowords became increasingly difficult, depending on the number of syllables and on morphological complexity. The accuracy and speed of reading were recorded ( = .84). Reading Words. A list of 40 non-vowelized words from the basal reader of the 8th grade was presented to the participants. The words became increasingly difficult, depending on the number of syllables and on morphological complexity. The accuracy and speed of reading were recorded ( = .68). As shown in Table 1, there was a significant difference in performance between the dyslexics and the age-matched group on measures of phonological awareness, rapid automatized letter and number naming, reading pseudowords (accuracy and speed) and reading words (accuracy and speed). Spelling Tests Spelling Test in Arabic. A list of 80 isolated words from the basal reader of grade 8 was chosen for spelling. The words increased in difficulty in terms of frequency, number of sylla- bles, and morphological complexity, and included elements that were likely to pose difficulty for students such as spelling rules and homophonous letters. The participants were asked to write short vowels at the end of the words, when and where necessary. The spelling accuracy was measured and the spelling errors were analyzed. Spelling Test in English. A list of 80 words in English was chosen for spelling. The words increased in difficulty in terms of the number of syllables and frequency, and included ele- ments that were expected to pose difficulty for students such as vowel and consonant digraphs, and silent letters. In addition, the list included regular and exception words. The spelling accuracy was measured and the spelling errors were analyzed. Word Frequency In order to control for word frequency, the lists of words in Arabic and English were given to 7 Arabic and 7 English teachers, who were asked to rate the frequency of the test items on a scale of 1 - 5 (1 least frequent, 5 most frequent). Inde- pendent samples t-test comparing the ratings of the word fre- quencies in Arabic and English showed no significant differ- ences between the two languages (t(158) = .18, p = .86), with mean frequencies of words being 3.87 in Arabic and 3.85 in English. The analysis of each pupil’s spelling errors was carried out in both Arabic and English using the following criteria: 1) Phonetic errors (Snowling et al., 1996): These errors adequately portrayed the sound structure of the target word, but were created by the inappropriate application of letter-sound correspondence rules (e.g. black-blak, /yastat/- /yastat/). This mismatch between phonology and orthography is made when the writer cannot rely on lexical writing. 2) Semiphonetic errors (Snowling et al., 1996): These errors contain a single phonemic error and could be created by omis- sion of a single phoneme, addition of a phoneme or substitution of one phoneme with a similar one (danger-denger, /ram/- /rm/). In this type of errors, the major phonological- orthographic chunk of the word is preserved. 3) Dysphonetic errors (Snowling et al., 1996): This type of error occurs when words are misspelled in more than one pho- neme, and when the spelled orthographic chunk does not rep- resent most of the phonemes of the target words (e.g. continue- countine, /lisiynatih/- /liyasuntah/). 4) Word omission: Errors of omitting whole words. Procedure During the first phase of the experiment, the five basic measures (Initial Spelling Test, Phonological Awareness Test, Rapid Automatized Naming, Reading Pseudowords, and Read- ing Words) were administered individually to the 8th grade stu- dents. The order of the tests was counterbalanced across par- ticipants. Each student participated in one session that lasted 20 to 30 minutes, varying according to the level of proficiency, at a quiet location within school. Immediately prior to the testing session, participants filled out a short background questionnaire (regarding age, gender, mother tongue, and learning difficul- ties). Also, the Initial Spelling Test was collectively adminis- tered to the younger regular students in order to select the spelling-level-matched group. The first phase took place in March, 2007. During the second phase of the experiment, the Arabic and English spelling tests were each collectively administered to the 8th graders as well as to the 5th and 6th graders in one session that lasted 30 to 45 minutes, depending on the grade of the participants. The class teacher was present during testing but did not participate. This phase took place at the end of May, 2007. Results Three separate analyses of variance for repeated measures were carried out on three spelling error categories: phonetic, semiphonetic, and dysphonetic, with group (dyslexic, age-mat- ched, spelling-level-matched) as the between subject factor and language (Arabic, English) as the within subject factor. A small number of word omission errors was made in Arabic (.33 words on average) and English (.67 words on average); therefore, no statistical analysis was carried out on this type of error. Phonetic Errors Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations of pho- netic errors made by the three groups in Arabic and English. A repeated measures analysis of variance (2 languages: Arabic Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR Table 2. Means and standard deviations of phonetic spelling errors in Arabic and English among the three groups. Arabic English Group M SD M SD Dyslexic 14 4.59 9.05 3.78 Age-matched 6.8 3.56 4.9 2.71 Spelling-level-matched 16.28 4.30 8.81 3.23 and English × 3 groups) for the number of phonetic errors re- vealed a significant main effect of language (F(1, 58) = 79.53, p < .001), indicating more phonetic errors in Arabic than in English. There was a significant main effect of group (F(2, 58) = 27.2, p < .001) with significant differences in the number of errors made by the three groups. Scheffe post hoc tests indi- cated that the dyslexic group made significantly more errors than the age-matched group (p < .001). However, the difference between errors made by the dyslexic and the spelling-level- matched group was not significant (p = .58). In addition, there was a significant interaction between group and language (F(2, 58) = 8.2, p < .001). Paired-samples t-test conducted for each group separately revealed significant differences between the number of pho- netic errors in Arabic and English among all three groups (t(19) = 4.89, p < .001, t(19) = 2.51, p < .05, t(20) = 7.59, p < .001, for the dyslexic group, age-matched group and spelling-level- matched group, respectively). Analysis of variance carried out on the difference between the number of phonetic errors in Ara- bic and English revealed that the above interaction arose due to significant differences between the groups (F(2, 61) = 9.12, p < .001). Scheffe post hoc test indicated that the difference be- tween the number of phonetic errors in Arabic and English was significantly larger among the spelling-level-matched group as compared to the age-matched group (p < .001), whereas the dif- ferences between the dyslexic group and the other two groups were not significant (p = .08, p = .16, comparisons with the age-matched group and the spelling-level-matched group, re- spectively). Semiphonetic Errors Table 3 summarizes the means and standard deviations of semiphonetic errors made by the three groups in Arabic and English. A repeated measures analysis of variance (2 languages: Arabic and English × 3 groups) for the number of semiphonetic errors revealed a significant main effect of language (F(1, 58) = 31.98, p < .001), indicating more semiphonetic errors in Eng- lish than in Arabic, and a significant main effect of group (F(2, 58) = 18.44, p < .001), indicating significant differences in the number of errors between the different groups. Scheffe post hoc tests showed that the dyslexic group made significantly more errors than the age-matched group (p < .001). However, the difference between the dyslexic and the spelling-level-matched group was not significant (p = .62). There was a significant interaction between group and language (F(2, 58) = 5.58, p < .01). Paired-samples t-test conducted for each group separately showed that the above interaction occurred because the number of semiphonetic errors made by the dyslexic group was equal in Arabic and English (t(19) = 1.70, p = .11), whereas the number of semiphonetic errors made by the other two groups was sig- nificantly higher in English than in Arabic (t(19) = 3.35, p < .01, t(20) = 5.0, p < .001, for the age-matched group and spell- ing-level-matched group, respectively). In addition, Scheffe post hoc tests showed that, in English, significantly more errors were made by the dyslexic than by the age-matched group (p < .001), whereas the difference between the errors made by the dyslexic and the spelling-level-matched group was not significant (p = .63). In Arabic, however, the dyslexic group made significantly more errors than both the age-matched (p < .001) and the spelling-level-matched groups (p < .05). Dysphone ti c Er r or s Table 4 presents the means and standard deviations of dys- phonetic errors made by the three groups in Arabic and English. A repeated measures analysis of variance (2 languages: Arabic and English × 3 groups) for the number of dysphonetic errors revealed a significant main effect of language (F(1, 58) = 14.44, p < .001), indicating more dysphonetic errors in English than in Arabic. There was a main effect of group (F(2, 58) = 3.49, p < .05). Scheffe post hoc tests indicated that the dyslexic group made significantly more errors than the age-matched group (p < .05). However, there was no significant difference in the number of errors between the dyslexic and the spelling-level- matched group (p = .17). There was no interaction between group and language (F(2, 58) = 1.05, p = .36). Discussion The results of the present study reveal that more phonetic er- rors were made in Arabic than in English, while more semi- phonetic and dysphonetic errors were made in English than in Arabic. In other words, more spelling errors in Arabic ade- quately portrayed the sound structure of the target word, whereas more errors in English occurred as a result of omissions or ad- ditions of single phonemes, or substitutions of one phoneme with a similar one. In addition, more errors in English occurred as a result of misspellings that did not represent most of the phonemes of the target words. In order to better understand these results, the Arabic and English spelling errors were fur- ther analyzed by qualitatively examining the specific elements in which the students tended to err. Table 3. Means and standard deviations of semiphonetic spelling errors in Ara- bic and English among the three groups. Arabic English Group M SD M SD Dyslexic 12.05 6.02 14.85 5.05 Age-matched 4.35 2.91 7.35 3.33 Spelling-level-matched7.61 5.08 16.67 8.30 Table 4. Means and standard deviations of dysphonetic spelling errors in Arabic and English among the three groups. Arabic English Group M SD M SD Dyslexic 1.5 2.54 2.70 2.90 Age-matched .15 .37 1.0 .79 Spelling-level-matched.67 1.06 2.76 4.07 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR In Arabic, many phonetic errors occurred as a result of poor mastery of spelling rules. One of the main spelling rules in Arabic which the pupils did not master concerns the writing of the consonant “Hamza”. The Hamza has several written forms, depending on its position in the word (i.e., initial, medial, or final), and on the diacritical marks surrounding it (Azzam, 1989). For example, at the beginning of a word, the Hamza is written above the letter Alif when followed by the short vowels /a/ or /u/, and under the Alif when followed by the short vowel /i/. The pupils in this study had difficulty choosing the right form of the Hamza. Another main spelling rule in Arabic involves the writing of the consonant t at the end of words. This consonant can be written as at the end of verbs and feminine plural nouns and adjectives, and or (de- pending on the letter preceding it) in nouns and adjectives in the feminine single form (Azzam, 1989). Pupils had trouble with writing the correct form of the letter. For example, the word /almasati/, which functions as a nouns in the feminine single form, was misspelled as * /almasati/. An additional type of error occurred in the spelling of the long vowel // at the end of words, which can be represented by the letters (Alif) or (Alif Maqsura). Pupils had difficulty choosing the appropriate letter. In the case of verbs, for exam- ple, some of the pupils wrote * /da/ instead of /da/ and * /ram/ instead of /ram/. With triliteral verbs, the rule is: if the verb in the present tense ends with the letter , it is written with when in the past tense. Alternatively, if the verb in present ends with the letter , then its past tense is written with . The choice between and is also determined by the part of speech of the word (verb or noun) and the num- ber of the root letters (triliteral or quadriliteral roots). Another common spelling error involved the writing of “Hamzat-lwasl” . In Arabic, if a word begins with a Hamza, which in this position is written over or under the letter Alif ( or ), the Hamza with its vowel are pronounced only when the word is at the beginning of the sentence. In the middle of the sentence, however, the Hamza with its vowel are dropped, and a sign called “Wasla” is put over the Alif instead of the Hamza. In this case, the Alif is not pronounced and only serves to com- bine the following vowelless letter with the last vowel of the preceding word, and then the two words are read as if they were one. The Hamza changed this way is called “Hamzat-lwasl”— the Hamza of linking (Kapliwatzky, 1940-1976). Since Hamzat- lwasl is not pronounced, many pupils tended to omit it in writ- ing. For example, the word /fastayqaða/ was written as * /fastayqaða/ and the word /fastadahu/ was writ- ten as * /fastadahu/. Due to the complexity of the rules mentioned above, many students had difficulty mastering them, and therefore they made many spelling errors. According to Azzam (1989), pupils need orthographic skills to deal with most of these context sensitive rules, but they need grammatical and semantic skills to master spelling. Further, many errors occurred as a result of substitution be- tween the consonants /t/- /t/, /d/- /d/, /s/- /s/, and /ð/- /ð/ that are phonologically similar and differ in emphasis, which is an Arabic phonetic feature. For example, /s/ is an emphatic dento-alveolar fricative, while /s/ is a non-em- phatic dento-alveolar fricative (Mitchell, 1990). In addition, these emphatics influence regressively or progressively the quality of consonants and vowels at frequently considerable re- move before or after them. Consequently, whenever an em- phatic consonant occurs within a syllable, the whole syllable is emphaticized. This phenomenon is not confined to the syllable boundary, but may have an influence on the neighboring sylla- ble as well (Al-Ani, 1970). As a result of the phonological similarity between the emphatic consonants and their plain counterparts, many spelling errors were made. For instance, the word /taqs/ was misspelled as * /taqs/ and the word /faqtanas/ was incorrectly spelled as * /faqtanas/. Thus, the errors described so far in Arabic adequately repre- sented the sound structure of the target words, and therefore they were considered phonetic. This result, namely, that the most prominent error type in Arabic was phonetic, is consistent with the findings of Abu-Rabia and Taha (2004). Abu-Rabia and Taha attributed the phonetic spelling errors to a limited orthographic lexicon. The finding that phonetic errors were more prevalent in Ara- bic than in English was observed among all three groups. However, this difference between errors in the two languages was more prominent among the younger spelling-level-matched group compared to the older age-matched group. This finding implies that the difference in spelling between the two lan- guages decreases as pupils grow older. It should be noted that this difference decreased due to the improvement of spelling ability, especially in Arabic. A possible explanation for this finding is that as Arab pupils grow older, they become more and more exposed to Arabic print, since they encounter it in their daily life and in different subjects at school such as history and geography. Their exposure to English, on the other hand, is confined mainly to English lessons. In English, many errors occurred as a result of substitution, addition or omission of letters, especially vowels. One common substitution error occurred between the vowels e and i, corre- sponding to the phonemes // and /i/, respectively (for example, listen-*lesten, children-*cheldrin, ship-*shep, tell-*till). This error could be explained by the phonological similarity between the phonemes // and /i/ as both of them are front, unrounded vowels (Treiman, 1993). Children as well as adults were found to rate // and /i/ as highly similar (Fox, 1983; Read, 1973; Singh & Woods, 1971). Many errors also occurred in vowel doublets and vowel di- graphs. A doublet is a spelling of two identical letters that are adjacent and symbolize a single phoneme such as ee and oo, whereas a digraph is a group of two different letters that repre- sent one phoneme such as ei (Treiman, 1993). Vowel doublets and digraphs do not exist in Arabic, as vowel phonemes are represented by single letters, and therefore they pose difficulty for Arab pupils. Some examples of such errors were *frind for friend, *whel for wheel, *hose for house, *clin for clean, etc. An additional type of error occurred in spellings of the silent e at the end of words. In some cases, the silent e alters the pre- ceding vowel to its long sound (e.g. the vowel in sit is /i/, while the vowel in site is /ai/, the long sound of the vowel /i/). In other cases, however, the silent e has no phonetic value, as in the case of some common exception words such as have and give. The misspellings in the final silent e involved the omis- sion and the addition of silent es at the end of words such as *phon for phone, *hom for home, *dolphine for dolphin and *kile for kill. Silent e does not exist in Arabic, and therefore Arab pupils tend to omit it. However, as they become more and more exposed to the English print, they notice its common oc- currence and start using it and adding it to words, even when unnecessary. The misspellings in final silent e were also seen Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR among native speakers of Hebrew (Tal, 2005). Another error type worth mentioning was omission of vow- els, especially from words with two syllables or more. Some examples were: *orgnize instead of organize, *contnue instead of continue, *exprience instead of experience, *hpen instead of happen, and *pblish instead of publish. A possible explanation for this type of error may be related to the nature of the Arabic orthography. As mentioned earlier, short vowels in Arabic are typically omitted from written texts because they can be filled using contextual clues, and would often be redundant if pre- sented in writing. Therefore, Arab readers do not devote much attention to them while reading. Native Arabic speakers were also found to approach English texts with written word identi- fication strategies that reflect the nature of their native Arabic writing system, that is, they devote less visual attention to vowel letters as opposed to consonants when reading English (Hayes-Harb, 2006). As reading and spelling are closely related processes, and the correlation between them is high (Ehri, 2000; Zuttle & Rasinski, 1989), native Arabic speakers who do not normally pay much attention to English vowels in reading, do not pay much attention to them in writing either, and may omit them. In addition, many of the errors involved substitutions, addi- tions or omissions of consonants. One spelling error worth mentioning is the substitution of the letter p with the letter b and vice versa. The phoneme /p/ does not exist in Arabic, and therefore some pupils tended to represent it with the letter b, which has a similar sound to /p/, as both of them are bilabial stop consonants (with /b/ being voiced and /p/ being voiceless). However, it is interesting to note that errors also indicated overcompensation by the pupils, in the sense that they em- ployed the strategy of writing p where the correct spelling is b. Some examples were *bage for page, and *bublish or *puplish for publish. These findings are consistent with those of Haggan (1991). In her study, she found that Arab university students in Kuwait made spelling errors that stemmed from the problems with /p/ and of their strategy to overcompensate by putting p where the correct spelling is b. Further, many errors occurred in consonant doublets and consonant digraphs. As mentioned earlier regarding vowel dou- blets and digraphs, consonant doublets and digraph are also absent in Arabic, as consonant phonemes are represented by single letters, and thus they create difficulty for Arab students. Some common errors were *hapen for happen, *ofice for of- fice, *tree for three, and *pone for phone. To summarize, the errors described thus far in English did not adequately portray the sound structure of the word; nonetheless, the major phono- logical-orthographic chunk of the word was preserved. It should be noted, however, that some English errors did portray the sound structure of the target word properly, and therefore were considered phonetic. Most of these errors oc- curred as a result of omitting silent letters, which are repre- sented graphically but are not pronounced (e.g. *rite for write, *now for know), and as a result of substituting letters with other single letters or digraphs that may represent the same pho- neme (*weal for wheel, *kut for cut, *dolfin for dolphin, *kwit for quit, *paje for page and so forth). Treiman (1993) ascribes the complexity of the English writ- ing system to at least four factors, three of which are relevant in the present study. First, the English orthography has one-to- many relations from phonemes to graphemes, and most pho- nemes are not represented with the same grapheme every time they occur. For instance, /k/ is sometimes symbolized with k, sometimes with c, and sometimes with other graphemes. Sec- ond, for those phonemes that have more than one spelling, it is sometimes impossible to predict when each spelling occurs, and there are often exceptions to the rules that exist. Yet, a third source of complexity is that English has many-to-one relations from phonemes to graphemes. For example, // and /ð/ are both spelled with th. Although significantly more semiphonetic errors were made in English than in Arabic, this was not the case for all groups. While the age-matched and the spelling-level-matched groups did show this pattern, the dyslexic group did not, as they made an almost equal number of semiphonetic errors in Arabic and English. One possible explanation is that the dyslexic group made not only a higher number of semiphonetic errors in Eng- lish, but also in Arabic, thus reducing the difference between the two languages. It should be noted that some of the Arabic semiphonetic errors, especially among the dyslexics, were the result of confusion between the short vowels , and and their corresponding long vowels , and , which may have been occurred due to difficulties in phonological discrimination. Some examples were: /kibrit/ for /kibrt/, * /aallaa/ for /aalla/ and * /yatma/ for /yatma u/. Other semiphonetic errors in Arabic involved sub- stituting “Hamzat-lwasl” with a Hamza. For instance, the word /fantalaqat/ was written as /faintalaqat/, and the word /fastayqaða/ was written as /faistayqaða/. These errors probably occurred as a result of poor mastery of this rule in Arabic. With regard to dysphonetic errors, the study revealed that more errors were made in English than in Arabic, though the number of dysphonetic errors was low in both languages. These errors occurred because words were misspelled in more than one phoneme and the spelling did not correctly represent the sound structure of the word. Examples include: *countine for continue, *rogmnt for recommend, * /fastah/ for /fastadhu/, and * /liyasuntah/ for /lisiynatih/. According to the model Abu-Rabia and Taha (2004) suggested to account for the spelling process among native Arabic speak- ers, semiphonetic and dysphonetic errors occur when there is no reliance on lexical knowledge or, simultaneously, when the phonological routes are not developed enough due to a phono- logical lag. Then it is assumed that the phoneme-grapheme mapping strategies will not be correctly applied, leading to the performance of semiphonetic and dysphonetic errors. Snowling et al. (1996) examined the phonological spelling strategies of dyslexic children (mean age 9.65 years) as com- pared to age-matched normal readers (mean age 9.70 years) and younger reading age-matched controls (mean age 7.3 years). The researchers found that the performance of the dyslexic readers was broadly similar to that of the reading age-matched group, with dysphonetic errors being more frequent than either phonetic or semiphonetic errors among both groups. The results of the present study are at odds with those of Snowling et al.; in their study, the dyslexic children were found to make a high proportion of dysphonetic errors as compared to semiphonetic and phonetic ones. In the present study, however, the most prominent error type among the dyslexics was semiphonetic in English, whereas an equal number of phonetic and semipho- netic errors was made in Arabic. One factor that may explain the discrepancy between the findings of studies comparing dyslexic readers is the severity of the disability. Children with Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR severe dyslexia are expected to have poorer phonological abili- ties and phonological spelling strategies than dyslexics with a milder disability, resulting in the occurance of a relatively higher proportion of dysphonetic errors. In fact, in the present study, the dyslexic pupils with a severe disability (according to their extremely low performance on the Initial Spelling Test basic measure) tended to make a higher proportion of dyspho- netic errors than other dyslexics. However, this could not be examined statistically due to the small number of pupils that had a severe disability. The results of the present study also showed that the dyslexic and the spelling-level-matched group made an equal number of phonetic, semiphonetic and dysphonetic errors, and both groups made more errors than the age-matched group. However, when English and Arabic were examined separately, it was found that the dyslexic group made significantly more semiphonetic errors in Arabic than the spelling-level-matched group. This finding is inconsistent with that of Abu-Rabia and Taha’s study (2004) which indicated that the semiphonetic errors were similar among the dyslexic children and their reading-level-matched controls. It should be noted, however, that the findings of stud- ies comparing dyslexic and normal readers can be expected to vary, depending on the age and the stage of development of both the dyslexic and the normal control groups (Rack, Snowl- ing, & Olson, 1992; Snowling et al., 1996). In Abu-Rabia and Taha’s study, the mean ages of the dyslexic group and the reading-level-matched group were 11.19 and 8.04 years, re- spectively, whereas, in the present study, the mean ages of the dyslexics and the spelling-level-matched group were 13.58 and 11.34 years, respectively. The pupils in the control group in Abu-Rabia and Taha’s study were very young (grade 2), and they were still in the early stages of spelling acquisition. Their phonological and orthographic knowledge was not fully devel- oped yet, much like those of the older dyslexic pupils in the same study who had poor phonological and orthographic abili- ties, due to a developmental lag. In the present study, on the other hand, the pupils in the control group are older (grades 5 and 6), and have more advanced phonological spelling strate- gies and orthographic knowledge, unlike the dyslexic group who has poor phonological spelling abilities. These poor pho- nological abilities result in the incorrect application of pho- neme-grapheme mapping strategies and, thus, leading to more semiphonetic errors. Analyzing the Arabic semiphonetic errors revealed that most of them occurred as a result of substitution between letters that are phonologically similar, especially vow- els. Summary of Findings The aim of the present study was to examine and analyze the types of spelling errors among regular and dyslexic students in Arabic as L1 and English as FL. The results indicated that most of the spelling errors in Arabic occurred as a result of poor knowledge of spelling rules as well as substitution between the emphatic consonants and their plain counterparts, especially when the latter underwent assimilation due to the existence of an emphatic consonant in the same or in the adjacent syllable. These spelling errors did not change the sound structure of the target words, but properly represented it; therefore, they were phonetic in nature. In English, most of the spelling errors occurred as a result of substitution between letters that are phonologically similar, substitution between letters or digraphs that may represent the same phoneme, omission of letters from vowel and consonant doublets or digraphs, poor knowledge of writing conventions, and omission of vowels and silent letters. Many of these ele- ments do not exist in Arabic, and therefore they pose difficult- ties for Arab pupils. Others occurred due to apparent influence of the Arabic writing system (such as vowel omission and con- fusion between p and b). Most of the errors in English were misspellings in one phoneme that preserved the major phono- logical-orthographic chunk of the word, and therefore they were considered semiphonetic. Based on the above findings, it can be concluded that most of the elements that pose difficulties for native Arabic speakers in Arabic lead to the occurrence of phonetic errors, whereas most of the aspects that create difficulties for them in English result in the occurrence of semiphonetic errors. Put differently, some problems encountered in a language are specific to the script, and the types of errors are influenced by the nature of the writ- ing system. However, the types of errors performed in a foreign language also seem to be influenced by the nature of the first language. Another finding of the present study is the similar error pro- files that the dyslexic and the spelling-level-matched group displayed, as both of them made an equal number of phonetic, semiphonetic and dysphonetic errors. However, when Arabic and English were examined separately, the dyslexic group was found to have made significantly more semiphonetic errors in Arabic than the spelling-level-matched one. These errors re- sulted from substitution between letters that are phonologically similar, especially vowels. Future Research The dyslexic students in the present study were found to make more semiphonetic errors in Arabic than their spell- ing-level-matched controls. However, the types of errors in this study were general in nature; therefore, it was difficult to pin- point the aspects in Arabic that posed a greater difficulty for dyslexics than for younger regular spellers and whether some aspects create difficulties only for dyslexic students. In order to answer these questions, a study needs to be conducted, where error types will rely on fine-grained analysis of the Arabic or- thography, and will be categorized according to the specific aspects that are expected to pose difficulties for native Arabic speakers. The spelling error profiles of dyslexics and spell- ing-level-matched group needs to be compared. As mentioned earlier, while only few dysphonetic errors were made by all three groups, there was a tendency among the students with severe dyslexia to perform a higher proportion of dysphonetic errors than those with a milder disability. However, since only a small number of students were considered to have a severe disability, this tendency could not be examined statis- tically. Therefore, a study could be conducted in which the spelling error types of dyslexic students classified according to the severity of their disability would be compared, in order to find out whether severity has an influence on spelling error profiles. Instructional Implications Considering the results of the present study, several instruc- tional implications can be suggested for teaching English spell- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR ing to Arabic speakers. First, since many elements that were found to pose difficulty for Arab pupils do not exist in Arabic, such as silent e, doublets and digraphs, they should be given an additional instructional emphasis. This recommendation is in accordance with Treiman’s (1993) conclusion that more time and effort should be allocated to the instruction of elements that children find difficult than elements which they find easy. She explains that children will be able to master and gain knowl- edge of the easy things on their own, but they will struggle with difficult things unless the difficulties can be overcome by means of teaching. Second, as some errors were presumed to occur as a result of transfer from L1, such as vowel omission and confusion be- tween /p/ and /b/, there seems to be a need to teach spelling while emphasizing the differences that exist between Arabic and English. Pupils should understand, for example, that while vowels can be omitted from written texts in Arabic, their repre- sentation is vital in English, since changing one vowel in a word completely changes its meaning. Third, on account of the fact that English vowels are abun- dant and different from Arabic ones, special consideration should be placed on vowel discrimination in the initial stages of English acquisition. For example, the pupils in the present study had difficulty in spelling the vowels e and i. The first step that should be taken to overcome this difficulty is to work with them on the phonological difference between the phonemes // and /i/. Afterwards, they should be taught that the phonemes // and /i/ are usually symbolized with the graphemes e and i, re- spectively. REFERENCES Abd El-Minem, I. M. (1987). Elm al-Sarf [Arabic grammar]. Jeru- salem: Al-Taufik Press. (in Arabic) Abu-Rabia, S. (2001). The role of vowels in reading Semitic scripts: Data from Arabic and Hebrew. Reading and Writing: An Interdisci- plinary Journal, 14, 39-59. doi:10.1023/A:1008147606320 Abu-Rabia, S., & Siegel, L. S. (2003). Reading skills in three orthog- raphies: The case of trilingual Arabic-Hebrew-English speaking Arab children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16, 611-634. doi:10.1023/A:1025838029204 Abu-Rabia, S., & Taha, H. (2004). Reading and spelling error analysis of native Arabic dyslexic readers. Reading and Writing: An Interdis- ciplinary Journal, 17, 651-689. doi:10.1007/s11145-004-2657-x Abu-Rabia, S., & Taha, H. (2006). Phonological errors predominate in Arabic spelling across grades 1 - 9. Journal of Psycholinguistic Re- search, 35, 167-188. doi:10.1007/s10936-005-9010-7 Akamatsu, N. (1999). The effects of first language orthographic fea- tures on word-recognition processing in English as a second lan- guage. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 11, 381- 403. doi:10.1023/A:1008053520326 Akamatsu, N. (2003). The effects of first language orthographic fea- tures on second language reading in text. Language Learning, 53, 207-231. doi:10.1111/1467-9922.00216 Al-Ani, S. H. (1970). Arabic phonology: An acoustical and physiologi- cal Investigation. The Hague: Mouton. Azzam, R. (1989). Orthography and reading in the Arabic language. In P. G. Aaron, & M. Joshi (Eds.), Reading and writing disorders in dif- ferent orthographic systems (pp. 203-218). London: Kluwer Aca- demic Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-1041-6_12 Azzam, R. (1993). The nature of Arabic reading and spelling errors of young children. Reading and writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 5, 355-385. doi:10.1007/BF01043112 Brown, T., & Haynes, M. (1985). Literacy background and reading development in a second language. In H. Carr (Ed.), The develop- ment of reading skills (pp. 19-34). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Bruck, M. (1988). The word recognition and spelling of dyslexic chil- dren. Reading Research Quarterly, 23, 51-68. doi:10.2307/747904 Carlisle, J. F. (1987). The use of morphological knowledge in spelling derived forms by learning disabled and normal students. Annals of Dyslexia, 37, 90-107. doi:10.1007/BF02648061 Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49, 222-251. Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education (Eds.), Schooling and lan- guage minority students: A theoretical framework (pp. 3-49). Los Angeles: Evaluation, Dissemination, and Assessment Center, Cali- fornia State University. Ehri, L. C. (1986). Sources of difficulty in learning to spell and read. In M. L. Wolraich, & D. Routh (Eds.), Advancements in developmental and behavioral pediatrics (pp. 121-195). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Ehri, L. C. (1992). Review and commentary: Stages of spelling devel- opment. In S. Templeton, & D. R. Bear (Eds.), Development of or- thographic knowledge and the foundations of literacy: A memorial festschrift for Edmund H. Henderson (pp. 307-332). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Ehri, L. C. (2000). Learning to read and learning to spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorder, 20, 19-36. doi:10.1097/00011363-200020030-00005 Eviatar, Z., & Ibrahim, R. (2000). Bilingual is as bilingual does: Me- talinguistic abilities of Arabic-speaking children. Applied Psycho- linguistics, 21, 451-471. doi:10.1017/S0142716400004021 Fender, M. (2003). English word recognition and word integration skills of native Arabic- and Japanese-speaking learners of English as a second language. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 289-315. doi:10.1017/S014271640300016X Figueredo, L. (2006). Using the known to chart the unknown: A review of first-language influence on the development of English-as-a-sec- ond language spelling skill. Reading and Writing: An Interdiscipli- nary Journal, 19, 873-905. doi:10.1007/s11145-006-9014-1 Fox, R. A. (1983). Perceptual structure of monophthongs and diph- thongs in English. Language and Speech, 26, 21-60. Frith, U. (1980). Unexpected spelling problems. In U. Frith (Ed.), Cog- nitive processes in spelling (pp. 495-515). London: Academic Press. Ganschow, L., Sparks, R., & Schmeider, E. (1995). Learning a foreign language: Challenges for students with language learning difficulties. Dyslexia, 1, 75-95. Gentry, J. R. (1982). An analysis of developmental spelling in GNYS AT WRK. The Reading Teacher, 36, 192-200. Goldsmith-Phillips, J. (1994). Toward a research-based dyslexia as- sessment. In N. C. Jordan, & J. Goldsmith-Phillips (Eds.), Learning disabilities: New directions for assessment and intervention (pp. 85- 100). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Hagan, M. (1991). Spelling errors in native Arabic-speaking English majors: A comparison between remedial students and fourth year students. System, 19, 45-61. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(91)90007-C Hakuta, K. (1976). A case study of a Japanese child learning English as a second language. Language Lear ni ng, 26, 321-351. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1976.tb00280.x Hayes-Harb, R. (2006). Native speakers of Arabic and ESL texts: Evi- dence for the transfer of written word identification processes. TE- SOL Quarterly, 40, 321-339. doi:10.2307/40264525 Henderson, E. H. (1985). Teaching spelling. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Ibrahim, R. (2006). Morpho-phonemic similarity within and between languages: A factor to be considered in processing Arabic and He- brew. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 19, 563- 586. doi:10.1007/s11145-006-9009-y Kapliwatzky, J. (1940-1976). Arabic language and grammar. Jerusa- lem: Hemed Press. Koda, K. (1988). Cognitive process in second language reading: Trans- fer of L1 reading skills and strategies. Second Language Research, 4, 133-156. doi:10.1177/026765838800400203 Koda, K. (1990). The use of L1 reading strategies in L2 reading: Ef- fects of L1 orthographic structures on L2 phonological recoding Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67  S. ABU-RABIA, R. SAMMOUR Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68 strategies. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12, 393-410. doi:10.1017/S0272263100009499 Koda, K. (1995). Cognitive consequences of L1 and L1 orthographies. In I. Taylor, & D. R. Olson (Eds.), Scripts and literacy: Reading and learning to read alphabets, syllabaries and characters (pp. 311-326). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1162-1_20 Miller-Guron, L., & Lundberg, I. (2000). Dyslexia and second language reading: A second bite at the apple? Reading and Writing: An Inter- disciplinary Journal, 1 2, 41-61. doi:10.1023/A:1008009703641 Mitchell, T. F. (1993). Pronouncing Arabic. New York: Oxford Uni- versity Press. Moats, L. C. (1983). A comparison of the spelling errors of older dys- lexic and second-grade normal children. Annals of Dyslexia, 33, 121- 139. doi:10.1007/BF02648000 Moats, L. C. (1996). Phonological spelling errors in the writing of dyslexic adolescents. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 8, 105-119. doi:10.1007/BF00423928 Nelson, H. E. (1980). Analysis of spelling errors in normal and dyslexic children. In U. Frith (Ed.), Cognitive processes in spelling (pp. 475- 493). New York: Academic Press. Rack, J. P., Snowling, M. J., & Olson, R. K. (1992). The nonword reading deficit in dyslexia: A review. Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 29-53. doi:10.2307/747832 Read, C. (1973). Children’s judgments of phonetic similarities in rela- tion to English spelling. Language Learning, 23, 17-38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1973.tb00095.x Read, C. (1975). Children’s categorization of speech sounds in English. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, Research Re- port No. 17. Rittle-Johnson, B., & Siegler, R. S. (1999). Learning to spell: Variabil- ity, choice, and change in children’s strategy use. Child Develop- ment, 70, 332-348. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00025 Ryan, A., & Meara, P. (1991). The case of the invisible vowels: Arabic speakers reading English words. Reading in a Foreign Language, 7, 531-540. Singh, S., & Woods, D. R. (1971). Perceptual structure of 12 American English vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 49, 1861-1866. doi:10.1121/1.1912592 Snowling, M. J., Goulandris, N., & Defty, N. (1996). A longitudinal study of reading development in dyslexic children. Journal of Edu- cational Psychology, 88, 653-669. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.88.4.653 Sparks, R., & Ganschow, L. (1991). Foreign language learning difficul- ties: Affective or native language aptitude differences? Modern Lan- guage Journal, 75, 3-16. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1991.tb01076.x Stage, S. A., & Wagner, R. K. (1992). Development of young chil- dren’s phonological and orthographic knowledge as revealed by their spelling. Development Psychology, 28, 287-296. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.2.287 Tal, M. (2005). An analysis of the English spelling difficulties of native Hebrew speakers. M.A. Thesis, Haifa: University of Haifa. Taouk, M., & Coltheart, M. (2004). The cognitive processes involved in learning to read in Arabic. Reading and Writing: An Interdiscipli- nary Journal, 17, 27-57. doi:10.1023/B:READ.0000013831.91795.ec Temple, C. M., & Marshall, J. C. (1983). A case study of developmen- tal phonological dyslexia. British Journal of Psychology, 74, 517- 533. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1983.tb01883.x Treiman, R. (1993). Beginning to spell: A study of first-grade children. New York: Oxford University Press. Treiman, R., & Bourassa, D. C. (2000). The development of spelling skills. Topics in Language Disorders, 20, 1-18. doi:10.1097/00011363-200020030-00004 Treiman, R., & Cassar, M. (1997). Spelling acquisition in English. In C. A. Perfetti, L. Rieben, & M. Fayol (Eds.), Learning to spell: Re- search, theory and practice across languages (pp. 61-81). Mahwah: Erlbaum. Varnhagen, C. N., McCallum, M., & Burstow, M. (1997). Is children’s spelling naturally stage-like? Reading and Writing: An Interdiscipli- nary Journal, 9, 451-481. doi:10.1023/A:1007903330463 Zutell, J., & Rasiniski, T. (1989). Reading and spelling connections in third and fifth grade students. Reading Psychology, 10, 137-15 doi:10.1080/0270271890100203

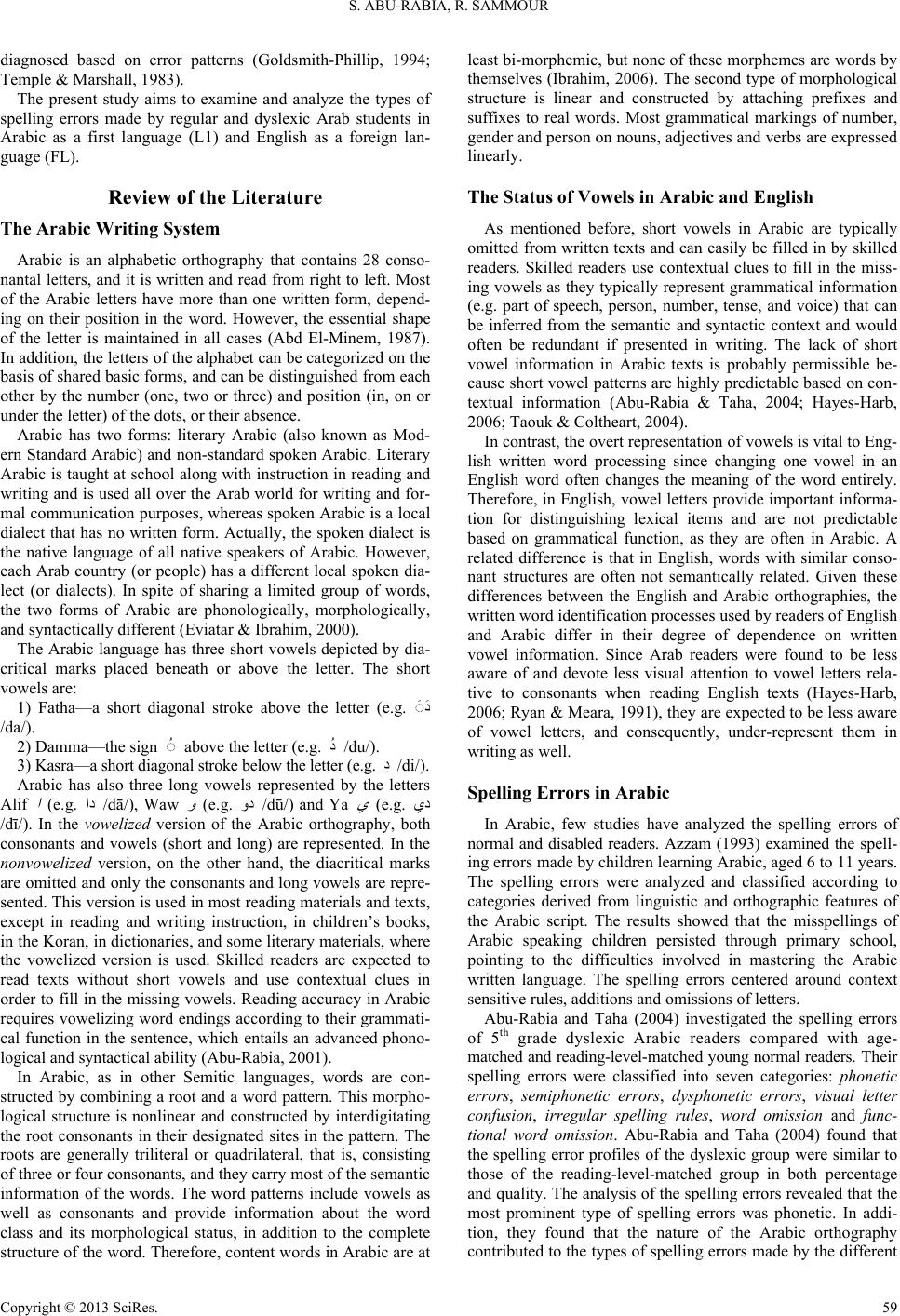

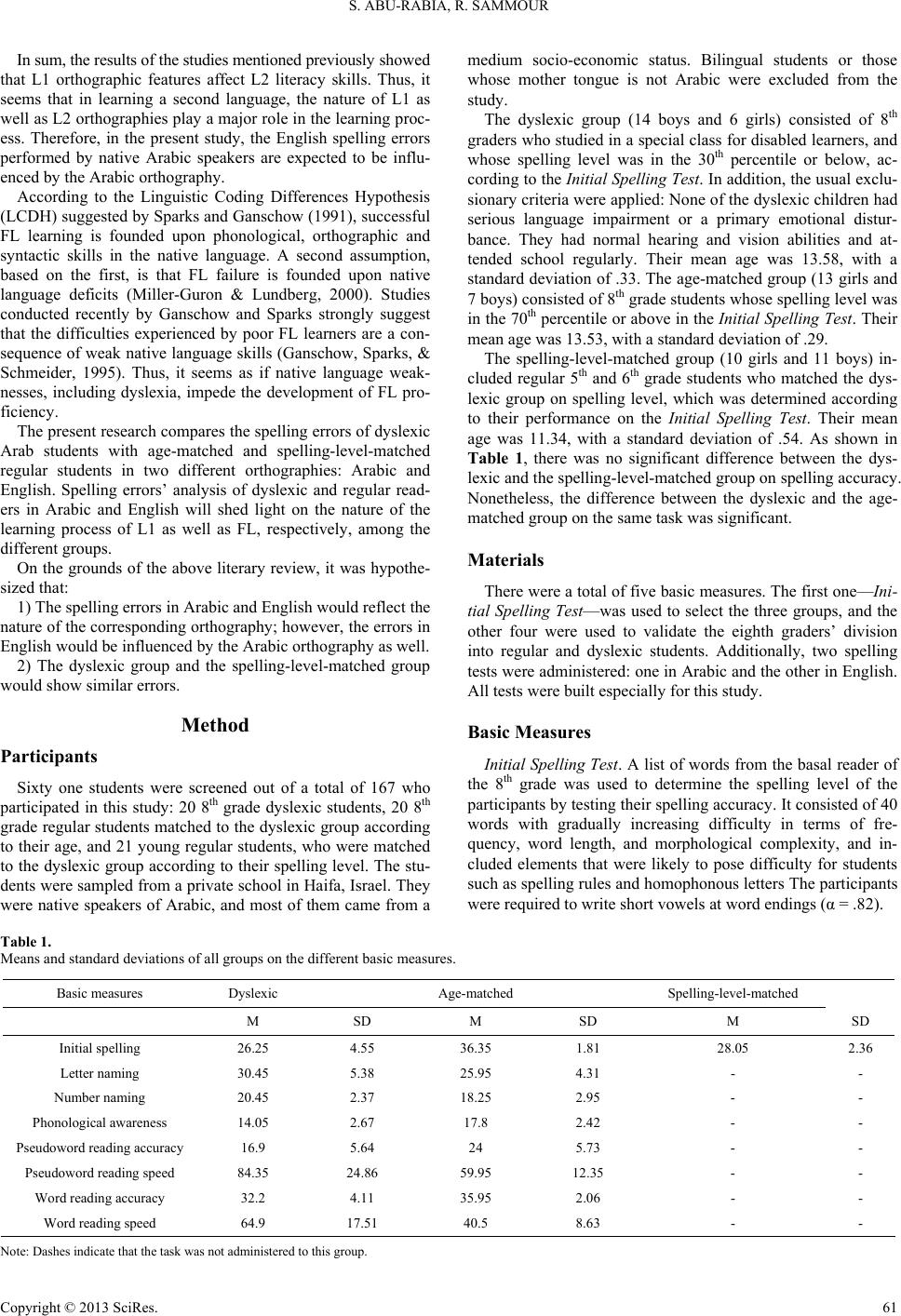

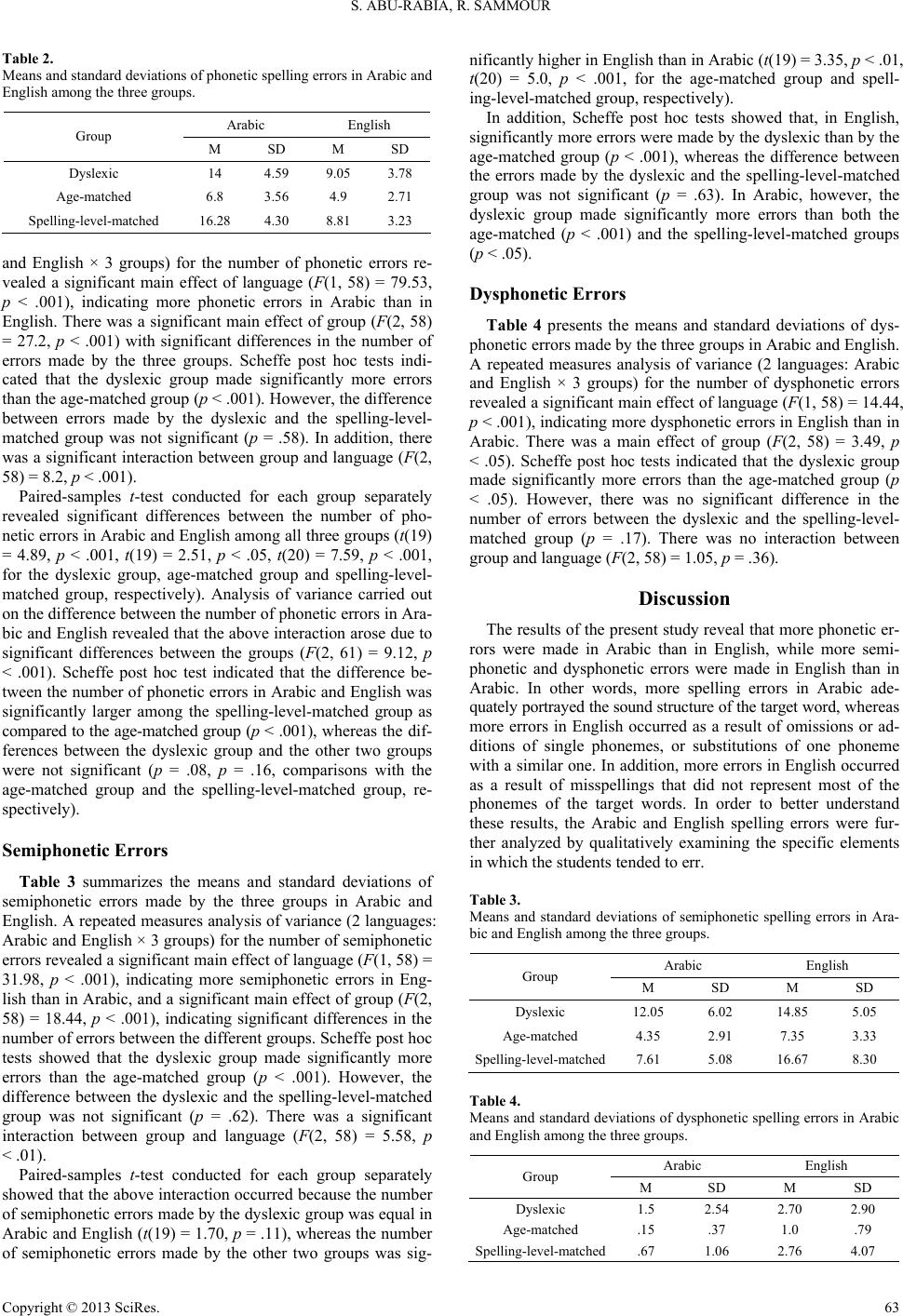

|