Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 40-46 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.31005 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 40 How Does Type of Orthography Affect Reading in Arabic and Hebrew as First and Second Languages? Raphiq Ibrahim1,2*, Asaid Khateb1,2, Haitham Taha1,2,3 1The Edmond J. Safra Brain Research Center for the Study of Learning Disabilities, Faculty of Education, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel 2Department of Learning Disabilities, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel 3Sakhnin College for Teachers’ Education, Sakhnin, Israel Email: *raphiq@psy.haifa.ac.il Received December 18th, 2012; revised January 2nd, 2013; accepted January 10th, 2013 This study aimed to examine the effects of visual characteristics of Arabic orthography on learning to read compared to Hebrew among Arabic and Hebrew bilinguals in an elementary bilingual education framework. Speed and accuracy measures were examined in reading words and non-words in Arabic and Hebrew as follows: Arabic words and non-words composed of connected and similar letters, words and non-words composed of connected and non-similar letters, and words and non-words composed of un- connected letters. In Hebrew, words and non-words composed of similar letters and non-similar letters. It was found that Arabic speakers showed an almost equal control in all reading tasks in both languages whereas, Hebrew speakers showed better performance in their mother tongue in all reading tasks. In Ara- bic, the best performance was in reading words and non-words that was unconnected. Based on these findings, it was concluded that Hebrew speakers did not succeed in transferring their good ability in read- ing their mother tongue to reading the second language, apparently due to the unique nature of the Arabic orthography. Our findings with regard to the cross-linguistic research literature as well as the specific features of Arabic language are discussed. Keywords: Reading; Arabic; Hebrew; Orthography; Visual Complexity; Diglossia Introduction Research on bilingualism over the past three decades has fo- cused on different issues including the effects of bilingualism on cognitive and linguistic development. The consensus on this issue today may be summarized thus: although bilinguals have a more complex and possibly multi-structured mental lexicon which is influenced by the idiosyncratic context in which the languages have been learned and by the structural relations between the languages (e.g., de Groot, 1992), this complexity need not result in differential cortical organization of linguistic abilities between bilinguals and monolinguals (Paradis, 2009). Bialystok (2001) claimed that exposure to more than one lan- guage at an early age results in heightened awareness of the arbitrary and phonological aspects of language. In a previous study, Arab children evince higher levels of phonological abili- ties than monolingual Hebrew speakers (Eviatar & Ibrahim, 2000). Alphabetic orthography, like English and Hebrew, pho- nological awareness is a very good predictor of success in read- ing acquisition (Share, Jorm, Maclean, & Matthhews, 1984). In turn to Arabic, the opposite finding has been reported in previ- ous study that examined the relationship between phonological abilities and various reading measures in first grade in Arabic children learning to read Arabic and in Hebrew (monolinguals) and Russian (bilinguals) children learning to read Hebrew (Ibrahim, Eviatar, & Aharon Peretz, 2007). The authors sug- gested that learning to read in Arabic is more challenging than in Hebrew. One possible answer to this is that this is an effect of the diglossia. In previous study it has been shown that skilled adult readers of Arabic also read more slowly than skilled adult readers of other languages (Azzam, 1993). There- fore, diglossia cannot be the only reason for this pattern. In addition, we wondered, what could be blocking the facilitative effect of phonological awareness. In this study, this question will be examined directly among children learning to read Arabic and Hebrew and studying in similar conditions in a bi- lingual education framework. Arabic and Hebrew Orthographic Characteristics Arabic is a typical case of diglossia. According to Saiegh- haddad (2005), modern standard Arabic (MSA) is the language used throughout the Arabic speaking world for writing and some other formal functions, such as speeches and religious sermons, while the spoken Arabic vernacular (SAV) is the lan- guage used for everyday conversation. The classical literary version is studied in school and is not acquired naturally with- out formal learning. Ibrahim (2009) reported that learning LA appears to be, in some respects, more like learning a second language than like learning the formal register of one’s native language. As opposed to the Arabic, diglossia does not exist in Hebrew. In addition to its diglossic nature, the orthography of Arabic plays essential roles in assessing reading and examining the predicative power of different processes. The unique characteristics of Arabic (and to little extent in Hebrew) orthography are many and complex, so only some, those most pertinent to the present investigation will be *Corresponding author.  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. reviewed briefly here. These are the positional variants of let- ters, the consonant diacritics, and letter ligature. Indeed, a num- ber of letters (graphemes) share the same form (derived from Nabatean which had fewer consonants) and are distinguished only by the position and the number of consonant (dot) diacrit- ics For example, the letters //, // and // represent the consonants /t/, /b/ and /th/ respectively. Some adaptations of the Arabic abjad (e.g., Sindhi in southern India), include up to 7 or even 8 diacritical variants of the identical letter-form. An addi- tional unique feature of Arabic orthography is that the majority of letters vary in shape according to position in the word; word- initial, medial or word-final position. It is worthy to emphasize that letter position also imply a change on the letter variant causing a little change ()//// or a large change (/)//// on the letter shape (for more examples see Appendix A). Six letters, however, have only two variant shapes which depend not only on the position in the word but also on the preceding letter (//r/; //z/; //d/; //th/; //w/; and //a/). This subset of letters may connect only from the right side (//Lawh/) but not from the left /(/Walad/). This sub-group of letters, there- fore, may appear to the reader as more “distinct”, because visu- ally separated from adjacent letters. Unlike the Arabic orthog- raphy, in Hebrew the majority of letters don't vary in shape according to position in the word. Only five letters, n, , m, , p, , tz, , h, have two forms depending on whether they appear in word-final or in other positions. Generally, the shal- low version of the Hebrew orthography where every phoneme is represented by either consonant or diacritical mark is ac- quired relatively easily with typically developing first grade children reaching decoding accuracy by the end of the first grade (Shatil, Share, & Levin, 1999). This is in contrast to the acquisition of basic reading skills in Arabic. Besides, the written vowelization system is considered as one of the unique features of the written Arabic. Written Arabic and Hebrew words could be vowelized by diacritical marks added above and below the letters within the word. In the case of vowelized written words, the written patterns are considered as shallow orthography, while in the case of non-vowelized writ- ten words, the orthography is considered as a deep one. In this case, the phonology is not reflected throughout the orthographic pattern alone but other context cues are needed. Deep ortho- graphic patterns usually appear in texts dedicated to adult read- ers (Abu-Rabia, 2000). Research on Orthography Within the orthographic patterns of the written words, some of the letters can be connected with former and subsequent letter, while other letter can be connected only with the former letters. As a result different types of written words can be pro- duced: 1) fully connected; 2) partially connected; and 3) non- connected words (i.e. words appearing with the basic forms of the letters). Recent findings showed that these differences of the internal connectivity of the written words in Arabic have an impact on the time course of early brain electric responses dur- ing the visual processing of letters (Ibrahim, Eviatar, & Aha- ron-Peretz, 2002; Eviatar, Ibrahim, & Ganayim, 2004) and writ- ten Arabic words (Taha, Ibrahim, & Khateb, 2012). These re- sults complement those reported by Rao, Vaid, Srinivasan and Chen (2011), where native Urdu readers read Urdu more slowly than Hindi. These authors suggested that this is due to two fac- tors: orthographic depth, where the relations between graph- emes and phonemes are more regular in Hindi than in Urdu (which has a consonantal script, like Arabic); and the greater visual complexity of Urdu orthography than Hindi orthography. A study by Taouk and Coltheart (2004), investigated learning to read in Arabic between children and adults. In one experiment they attempted to examine naming of real pronounceable “posi- tion-illegal” words; which are words written with a wrong letter variant according to its position. They found that children’s word reading was significantly impaired when incorrect posi- tional variants were substituted for the correct variants. This finding provides evidence that positional variants of letters affect word reading. A recent study by Abdelhadi, Ibrahim and Eviatar (2011) examined how orthographic complexity can af- fect vowel identification between 3rd and 6th grade. They used a vowel identification task with stimuli in Arabic and Hebrew at three levels of lexicality; real words, pseudo-words and non- letters. Each level included three categories; separated letters, ligatured or connected letters and connected letters with vowel diacritics. The participants were required to identify a specific vowel, fatHa or Patax. The highest performance was predicted for separated letters, followed by connected letters, while the poorest performance was expected on stimuli with connected letters with vowel diacritics. The results were not consistent with the hypothesis; unexpectedly, children from both grades responded faster to letter strings with connected letters (both words and pseudo-words). These results suggested that 3rd and 6th graders used a different perceptual strategy when the stimuli were more word-like (e.g., comprised of connected letters) than when they were less word-like (e.g., comprised of disconnected letters). The Linguistic Reality in Israel The education system in Israel maintains the existing de- tachment between Jews and Arabs: schools are nationally- separated. Although Arabic is considered as a formal language in the country, Jewish students are less exposed to Arabic lan- guage in particular and to Arabic culture in general than Arab students who study extensively Hebrew language, literature and culture (Al-Hag, 2003; Amara & Mar I, 2002). In Israel, bilingual schools emphasize the symmetry between the two languages, Arabic and Hebrew, in every teaching meas- ure. Therefore, reading constitutes a fundamental skill in the acquisition of every language. Reading contains the ability to connect reading symbols to meaningful word for the sake of text decoding. From theoretical view, accepted theory concern- ing the field of learning of second language and bilingualism ascribes academic success and the acquisition of second lan- guage in the level of the first language (Cummins, 1991, 2000). According to Cummins (2000), as much as the level of linguis- tic expertise in the first language increases (passes certain threshold) over certain level of skillfulness higher than in the second language (another higher threshold), appear the cogni- tive growth. The Current Study In this study we postulate that the level of performance in reading tasks (the speed and accuracy of reading) in Arabic and Hebrew language (correspondingly) may reflect the different nature of the transfer to second language. Native Hebrew speak- ers may find more difficulty in learning Arabic as a second Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 41  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 42 language than do native Arabic speakers when learning Hebrew, this difference results from the complexity of the Arabic lan- guage. According to the above mentioned postulation, an aca- demic success in learning second language is only dependent on skills acquired in first language, and therefore according to Cummins’s interdependence hypothesis, we may expect that there are no differences between the two bilingual groups in all the other influencing conditions, i.e. age, the period of exposure to second language and learning environment. In addition, this study examines the unique characteristics of Arabic orthogra- phy on the speed and accuracy measures when reading words and non-words in Arabic and Hebrew as first and second lan- guage. The hypotheses of the study: 1) As far as accuracy and speed are concerned, we predict the level of performance will be better in tests examining reading in first language than reading in the second language. According to Cummins interdependence hypothesis, academic success in learning second language is only dependent on skills acquired in the first language. 2) We predict the performance in reading tests in Hebrew will be at a similar level or even better than reading tests in Arabic beyond groups. In their study, (Ibrahim, Eviatar, & Aharon-Peretz, 2002) explained that this mostly results from two reasons: first, the orthographical complexity of the Arabic language and second, the status of written Arabic (Literary) which is considered by some authors as a second language (Ibrahim & Aharon-Peretz, 2005; Eviatar & Ibrahim, 2001; AbuRabia, 2000; Saiegh-Haddad, 2003, 2004). 3) Among native Arabic speakers, reading words with dis- connected letters in Arabic is better (in terms of accuracy and speed) than reading words with connected letters. According to Azzam (1993), the major problem is that children have to re- member tree or four shapes for each letter according to the position in the word and the child’s ability to distinguish be- tween letters based on tiny differences of a single characteristic or the position of dots in letters. Method Participants: 49 participants (32 from 3rd grade and 17 from 4th grade) with an average age of 9.3 years participated in this study. They were recruited from two bilingual schools in the north and center of the country where the study was conducted. Participants from the two groups were matched with regard to age, general ability, and the level of reading (educators chose children with commanding performance in reading in the two languages Arabic and Hebrew and none of them was diagnosed with learning disabilities). In the bilingual educational schools participated, literacy in Hebrew and literacy in Arabic is ac- quired in parallel from first grade. Children receive equal amounts of instruction in each language daily by both Hebrew and Arabic L1 teachers. Therefore the teaching method planned to be similar in two languages. Stimuli: Three types of lists of words in Arabic were con- structed: words with connected and similar letters, words with connected and non-similar letters and words non-connected letters (see Table 1 for example). In Hebrew, two lists of words were constructed: words with similar letters and words with non-similar letters (see Table 2 for example). This difference is due to the fact that Hebrew letters do not connect with each other. For each word sub-list, a list of non-words was estab- lished. This allowed examining the process of pure encoding of reading in comparison with the process of structural reading of familiar words. In all list, non similar (non-cognate) words from literary and non-literary Arabic (spoken) were chosen. This step was taken to avoid the possibility that similar shapes cause to bias scores. Before, conducting the experiment, the frequency of words in stimulus list was assessed. For this purpose, the initial word list included 240 words in Arabic (divided into three sub-lists de- fined on the basis of their orthographic characteristics) and 160 words in Hebrew (divided into two groups based on their orthographical characteristics). The initial Arabic and Hebrew word lists established with the of language teachers from other schools in the neighboring area. The words of all lists were then introduced in a questionnaire of frequency which was filled by children. Here, they had decide how frequent was each word using a scale ranging between 1 (rare) and 5 (very frequent). Based on the results of this assessment, 24 words whose mean frequency ranged between 1.5 - 3.5 points were finally retained for each sub-list. The rationale for using this middle frequency range was to neutralize as much as possible the factor of word frequency. Table 1. Experimental conditions in Arabic. Words which consist of similar letters and connected Words which consist of dissimilar letters and connected Words which consist of letters that is disconnected word non-word word non-word word non-word tantab Batnat methyaa’ thaya’am awzan azwan Table 2. Experimental conditions in Hebrew. Words which consist of similar letters Words which consist of dissimilar letters A word A non-word A word A non-word harad dahor zahov zahol  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. It should be noted that the number of syllables and length of the words were controlled between Arabic and Hebrew. As for the non-words (which also were comparable to words in length and number of syllables), they were formed by changing one or two letters in the word or by substituting the position of some letters within each real word. All together, the study included six sub-lists in Arabic (of 24 items each) and four sub-lists in Hebrew (also of items). Concerning the matter of examining the reliability of tasks, an examination of the measure reliability of different tasks was conducted based on Alfa Cronboch. (See Table 3). From Table 3, it can be inferred that beyond the language groups, grades’ reliability and speed of reading in different tasks ranged between .76 and .97. Procedure: The study took place inside the school in quiet room, individually for each participant. The meeting with each participant started with a short acquaintance aimed at creating a comfortable atmosphere while providing a brief explanation for the essence of the meeting in order to remove any concern, dis- comfort or hesitation. When the participant confirmed his readi- ness to start the tasks he/she was instructed to read ten sub-lists (hereafter tasks) in Arabic and Hebrew as fast and accurately as possible. The order of the presentation of the tasks was bal- anced across participants. Four short training lists were pre- pared so as familiarize the participants with the different tasks. Before starting each task, they were informed that their reading time of each tasks will be monitored using a stopwatch. In ad- dition, a digital recorder registered their reading during the successive tasks for assessing off-line their reading accuracy. Results The analysis of the reading accuracy and speed in the native language showed that both reveal a good reading performance among the two groups of participants (native Arabic speakers and native Hebrew speakers) concerning speed and accuracy in the different task in their native language. Furthermore, very important results were found in relation to the difference status of Arabic language for native Arabic speakers and as a second language for native Hebrew speakers. This is in comparison to the status of Hebrew language for the two groups of speakers. Decisive effect of Arabic writing characteristics on the acquisi- tion of this language was demonstrated by tyro readers. The average time of reading and percentages of accuracy in all read- ing tasks (reading separated words and reading text) in the two languages were the dependent variables. The results of each hypothesis mentioned at the introduction are separately presented as the basic question which stands at the core examination is: is learning to read in Arabic language more difficult than Hebrew? The average-time of reading and percentages of accuracy were analyzed as the native language (Arabic speakers and Hebrew speakers), the language of the test (Arabic and He- brew) and the type of the test (reading words and reading text) were served as independent variables. Regarding the issue of the two types of tasks (reading words and reading text) two analyses were conducted: In the first analysis, the variable of the type of tests included three levels of different types of words (connected and similar, connected and dissimilar, and disconnected). Examining differences in reading accuracy of native lan- guage on the basis of native language: One-way analysis of variance of the grade in reading words in native language on the basis of native language was carried out and significant results were found F(1,47) = 15.47, p < .001, 2 = .25. Native Arabic speakers are more successful (M = 97.62, SD = 1.78), than their counterparts (native Hebrew speakers) (M = 93.73, SD = 4.26). Examining difference in the speed of reading words in native language on the basis of native language: Here a one-way analysis of variance in the speed of reading words in mother language on the basis of native language was carried out and significant results were found F(1,47) = 19.80, p < .001, 2 = .30. Hebrew speakers (M = 34.40, SD = 10.68), are faster than their counterparts (Arabic speakers) (M = 50.15, SD = 13.32). It should be pointed out that compatibility in the number of syllables and the length of words in each task in the two languages (Arabic and Hebrew) was conducted. Examining differences in the speed of reading Arabic words on the basis of native language and type of words: Here are two-way analysis of variance in the speed of read- ing words in Arabic on the basis of native language and type of words was conducted with repeated measurements for type of words and significant differences were found (F(1,47) = 55.35, p < .001, 2 = .54). Arabic speakers (M = 50.15, SD = 13.32) were faster than their counterparts (Hebrew speaker) (M = 128.57, SD = 53.80). In addition differences were also found on the basis of type of words F(5,235) = 48.11, p < .001, 2 = .51. An interaction based on native language and type of words was found F(5,235) = 20.26, p < .001, 2 = .30. To examine the source of this interaction, researchers carried out a Post-Hoc test. It was found that regarding to test 5 (words with disconnected letters), Arabic speakers were faster than Hebrew speakers in comparison to other types of words. In addition, regarding test 6 (non-words with disconnected letters), Arabic speakers were faster in comparison to tests 2, 3 and 4. Further- more, it was also found that Hebrew speakers were faster in reading words 4, 5 and 6, than words 1, 2 and 3, and they were also slower in reading words from type 4 than words from types 5 and 6. Examining differences of accuracy in reading words in Ara- bic language on the basis of native language and the type of word: Table 3. Accuracy and rates in reading Arabic and Hebrew words. Total items SD Mean Task (Cronbach) 6 .97 Accuracy in reading Arabic words 81.22 22.57 6 .96 Reading rate of Arabic words 83.76 53.32 4 .76 Accuracy in reading Hebrew words 95.73 4.29 46.62 20.23 .95 4 Reading rate of Hebrew words Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 43  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Two-way analysis of variance of grade in reading words in Arabic on the basis of native language and the type of word with repeated measurements for the type of word was con- ducted. Significant differences was found accordingly F(1,47) = 34.32, p < .001, 2 = .42. Arabic speakers (M = 94.32, SD = 3.90), were more successful than Hebrew speakers (M = 67.53, SD = 23.86). In addition differences in the type of words were found F(5,235) = 30.54, p < .001, 2 = .39. Here there is an interaction based on native language and the type of word F(5,235) = 17.71, p < .001, 2 = .27. To examine the source of this interaction, a post-hoc test was carried out. It was found that Arabic speakers were more suc- cessful in words of the type 5 (words with disconnected letters) and they were also more successful in words of the type 6 (non-words with disconnected letters) in comparison to words of the type 2 (non-words with connected and similar letters. Examining difference in the speed of reading words in He- brew language based on native language and type of word: Researchers conducted a two-way analysis of variance in the speed of reading words in Hebrew based on native language and type of words with repeated measurement for the type of word. Significant differences based on native language were found F(1,47) = 18.24, p < .001, 2 = .28. Hebrew speakers (M = 34.93, SD = 10.68), were faster than Arabic speakers (M = 55.79, SD = 20.97). In addition, differences were found con- cerning the type of words F(3,141) = 18.63, p < .001, 2 = .28. Therefore, there is an interaction on the basis of native language and the type of word F(3,141) = 13.56, p < .001, 2 = .22. To examine the source of this interaction, a Post-Hoc test was carried out. It was found that among Arabic speakers, no differences were found in the speed of reading based on type of word. It was also found that Hebrew speakers were faster in reading words with dissimilar letters than reading words with similar letters or non words. They were also faster in reading words with similar letters than reading non-words with similar and dissimilar letters. Examining differences in accuracy in reading words in He- brew based on native language and type of word: Tow-way analysis of variance in the grade of reading words in Arabic based on native language and the type of word with repeated measurements for the type of word was conducted. Significant differences were found regarding native language F(1,47) = 8.22, p < .01, 2 = .15. Hebrew speakers, (M = 97.62, SD = 1.78), were more successful than Arabic speakers (M = 94.31, SD = 5.05), though no differences were found concerning the type of word F(3,141) = .74, p > .05, 2 = .02. Thus, there was no interaction on the basis of native language and type of word F(3,141) = .43, p > .05, 2 = .02. Examining differences in the speed of reading words based on native language and the language of test: Tow-way analysis of variance of the speed of reading words based on native language and the language of test with repeated measurement for the language of test was conducted. Signifi- cant differences were found regarding native language F(1,47) = 18.59, p < .001, 2 = .28. Arabic speakers (M = 52.97, SD=16.57), were faster than Hebrew speakers (M = 81.48, SD = 29.37), and here significant differences were found regarding the language of test F(1,47) = 80.43, p < .001, 2 = .63. Among all participants, it was found that they were faster in reading in Hebrew M = 45.09, SD = 20.23 than Arabic (M = 89.36, SD = 53.32), and this is beyond the native language F(1,47) = 102.22, p < .001, 2 = .69. Finally, an interaction was found based on native language and the language of test F(1,47) = 102.22, p < .001, 2 = .69. A post-hoc examination suggests that for native Arabic participants, no differences were found between reading words in Arabic (M = 50.15, SD = 13.32), and reading words in Hebrew (M = 55.78, SD = 20.97). On the other hand, for native Hebrew participants, the speed of reading words in Arabic (M = 128.57, SD = 53.80), is longer than the speed of reading words in Hebrew (M = 34.39, SD = 10.68). It was also found that native Arabic readers’ speed of reading Arabic is faster than native Hebrew readers. Conversely, native Hebrew readers’ speed of reading Hebrew is faster than the speed of native Arabic. Examining differences in accuracy of reading words based on native language and the language of test: This research reveals another important finding that is con- sistent with a line of earlier studies which suggested that the status of literary Arabic is equal to the second language for native Arabic readers. According to this finding, native Arabic rehears’ performances in Arabic reading tasks were not differ- ent from their performances in Hebrew reading tasks (Actual second language). On contrary, native Hebrew readers’ per- formance in reading Hebrew tasks was significantly better. Here, researchers conducted a tow-way analysis of variance for grade in reading words based on native language and the language of test with repeated measurement, and significant differences related to native language were found F(1,47) = 23.14, p < .001, 2 = .33. It was also found that native Arabic speakers were more successful (M = 94.31, SD = 3.94), than their Hebrew counterparts (M = 82.57, SD = 12.13). Therefore, differences related to the language of test were also found F(1,47) = 43.77, p < .001, 2 = .48 accordingly there is an interaction based on native language and the language of test F(1,47) = 43.84, p < .001, 2 = .48. Graph 5 shows the re- ceived interaction (See Figure 1). According to a Post-Hoc examination, for native Arabic par- ticipants, no differences were found in accuracy of reading words in Arabic (M = 94.32, SD = 3.90) and reading words in Hebrew (M = 94.31, SD = 5.05). On the contrary, for native Hebrew participants, the level of accuracy in reading words in Hebrew (M = 97.62, SD = 1.78), was higher than reading words in Arabic (M = 67.53, SD = 23.86). In addition, concerning reading Arabic words, native Arabic readers were better than Figure 1. Interaction of reading words accuracy by the subject native language. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 44  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. native Hebrew readers. Yet, concerning reading words in He- brew, no differences were found between the two groups. Discussion The analysis of the study’s results is conducted on the basis of Cummins’s (1979-1981) interdependence hypothesis. Ac- cording to this hypothesis a good linguistic ability in the first language predicts similar ability in the second language. Con- sequently, native Hebrew and Arabic speakers would have been expected to read in second language at a similar level (of speed and accuracy) to their native languages. Yet it was found that native Arabic speakers read significantly better in Hebrew than native Hebrew speakers read in Hebrew. These findings em- phasize that learning to read in Arabic language more chal- lenging and than reading in Hebrew even though Arabic and Hebrew have a similar nominal basis. In the course of the current study, tasks the level of perform- ance was compared with reading separated words and non- words in Arabic and Hebrew, when the unique characteristics of Arabic orthography were greatly considered from a forma- tive point of view. In this regard, the purpose was to clarify emperically whether Arabic language is more difficult in proc- essing than Hebrew. As it has been planned, the two popula- tions whose mother languages are different are simultaneously and at the same extent exposed to reading and writing in the second language in the same educational frame; two bilingual schools in Israel. The first prominent finding in this study was that reading Hebrew is faster and more accurate than reading Arabic beyond the native language (Arabs as Jews) and beyond the type of test (reading words and non-words). In this context, it is important to note, that even though acquisition of the Hebrew orthography is characterized by some level of complexity due to for example the similarity in the shape of the letters, the acquisition of the Arabic orthography is very much more complicated. Besides for the diglossia of the Arabic language, there is an additional complexity stemming from the similarity in the shape of letters, number of dots above or below, the connection between the letters, together with the changing shape of letters depending on their location within the word. Thus, our data bring additional evidence that this complexity influences both reading accuracy and reading rate among the two groups (Arabic and Hebrew speakers). This finding is important and is joined with earlier findings that dealt with the status of literary Arabic language for Arabic readers as well as the formative difficulty of Arabic orthography (Eviatar, Ibrahim, & Ganayim, 2004; Ibrahim Eviatar & Aharon Peretz, 2002; Maamouri, 1998; Saiegh-Haddad, 2003). This central finding relates to fundamental differences be- tween the two types of orthographies in Arabic (connected words versus nonconnected words) and Hebrew (words with similar versus words with dissimilar letters). In this compari- son, it was found that among Arabic speakers, reading words and non words in Arabic with disconnected letters is more ac- curate and faster than reading words and non-words with con- nected letters among either group. This finding emphasizes the difficulty in reading words and non-words composed of con- nected letters and basically of similar and connected letters—a specific quality of Arabic orthography. This finding is in line with the findings of Ibrahim et al. (2002) who compared the spatial identification of Arabic letters with Hebrew letters. Even so, in the same area (but inside participants), differences were found among native Hebrew speakers; only in the speed based on the type of word (groups of words and non-words separate by the type of the orthographical information). However, there were no differences in the accuracy of reading words and non words (with similar and dissimilar letters). Among Hebrew speakers, it was found that the speed of reading words with similar letters is slower than reading words and non words with dissimilar letters. The matter of the similarity of the shape and feature of letters was also examined in Arabic language. Shim- ron & Navon (1982), argued that in comparison to other lan- guages, all letters in Hebrew are quadrangular and similar, such as English. According to these researchers, letters in Hebrew are mostly at one line this affects the ability to identify word. When letters are more similar, it is more difficult to identify them compared to dissimilar letters (Shimron & Navon, 1982). Therefore in comparing Arabic and Hebrew, the speed of He- brew speakers in reading words with similar letters in Hebrew is faster than the speed of Arabic speakers and native Hebrew speakers in reading words with similar and connected letters. It should be noted that the similarity in the shape of letters in Hebrew leads to a relative delay in indentifying words but not making error. Although the similarity in Arabic orthography (the shape of letters, the number of dots above and under, the connection between them, together with the change of their shapes based on their positions in the word) affects the accu- racy and speed of reading among the two groups. This result is in consistency with earlier studies conducted by Eviatar and her colleagues (2004), who suggested that there are other factors which may add special difficulty when reading in Arabic leads to slower reading and making errors (Eviatar, Ibrahim, & Ga- nayim, 2004). Beyond that, at initial presentation, the connected items (which were matched for diacritical complexity) were actually read more quickly than the non-connected items. This finding is consistent with Abdelhadi et al. (2011) who also found a speed advantage for words with connecting letters among skilled adult readers of Arabic performing a visual search task. The authors attributed this advantage to the fact that most printed words in Arabic consist of ligatured letters rather than non- ligatured letters. The present data, therefore, replicates this finding and extends it to young readers perform- ing a standard word pronunciation task. In a related issue, Ibra- him and Eviatar (2012) tried to determine if the processing of Arabic orthography seems to make different demands on the cognitive system both in beginning and in skilled readers while recognizing Arabic letters compared to Hebrew letters. The re- searchers used behavioral measures of performance asymme- tries in a divided visual field paradigm. There results show that Arabic orthography specifically disallows the involvement of the RH in letter identification, even while the RH of the same participants does contribute to this process in English and in Hebrew. The results were attributed to the additional visual complexity that characterizes Arabic orthography. Conclusion and Future Research The present study investigated 3rd and 4th grade bilingual Arabic/Hebrew-speaking learners in relation to visual factors which are central to issues of second language learning. While we did not aim to propose an explanatory model of learning to read in second language, the findings of the present study sup- port previous findings suggested that measures of speed and accuracy of reading in Hebrew among Arabic speakers were Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 45  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 46 significantly higher than measures of reading in Arabic among Hebrew speakers. Our conclusion was that Hebrew speakers did not succeed in transferring their proficiency and success in reading in their mother tongue to success in reading the second language. In view of the fact that bilingual schools use similar method in teaching the two languages, this allow us to conclude that Hebrew speakers did not succeed in transferring their good ability in reading their mother tongue to reading the second language, due to the unique nature of the Arabic orthography. Turning to reading disabled (or dyslexic) children, Breznitz (2003) argued that the inefficiency of reading process in this population derives not only from problems of accuracy and timing inside a specific processing system but also from inter- action of information between systemic processes (i.e., the vi- sual-orthographical system). The findings regarding learners’ proficiencies in second language (Arabic or Hebrew) contribute to debates regarding the best methods or the strategies that might be chosen to teach learning to read second language. The findings of the present study rather suggest that, it is useful to continue to explore the cognitive and neurocognitive basis in decoding writing systems and how type of orthography might affects some hitherto neglected aspects of second language learning and L2 proficiency. REFERENCES Abdelhadi, S., Ibrahim, R., & Eviatar. Z. (2011). Perceptual load in the reading of Arabic: Effects of orthographic visual complexity on de- tection. Writing Systems Resear ch, 3, 117-127. doi:10.1093/wsr/wsr014 Abu-Rabia, S. (2000). Effects of exposure to literary Arabic on reading comprehension in a diglossic situation. Reading and Writing: An In- terdisciplinary Journal, 13, 147-157. doi:10.1023/A:1008133701024 Abu-Rabia, S., & Siegel, L. S. (1995). Different orthographies, differ- ent context effects: The effects of Arabic sentence context inskilled and poor readers. Reading Psychology: An International Quarterly, 16, 1-19. doi:10.1080/0270271950160101 Amara, M., & Mar’i, A. (2002). Language education policy: The Arab minority in Israel. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605963 Azzam, R. (1993). The nature of Arabic reading and spelling errors of young children. Reading a nd Writing, 5, 355-385. doi:10.1007/BF01043112 Breznitz, Z. (2003). Speed of phonological and orthographic processing as factors in dyslexia: Electrophysiological evidence. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs, 129, 183-206. Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic Interdependence and the Educational Development of Bilingual Children. Review of Educational Research , 49, 222-251. Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in pro- moting educational success for language minority students. In Cali- fornia State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework (pp. 3-49). Los Angeles: Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center, California State University. Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual chil- dren in the crossfire. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Eviatar, Z., & Ibrahim, R. (2001). Bilingual is as bilingual does: Me- talinguistic abilities of Arabic speaking children. Applied Psycholin- guistics, 21, 451-471. doi:10.1017/S0142716400004021 De Groot, A. M. B. (1992). Determinants of word translation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18, 1001-1018. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.18.5.1001 Ibrahim, R., & Aharon-Peretz, J. (2005). Is literary Arabic a second language for native Arab speakers: Evidence from a semantic prim- ing study. The Journal of Psycholinguistic Re s ear ch , 34, 51-70. doi:10.1007/s10936-005-3631-8 Ibrahim, R., & Eviatar, Z. (2012). Multilingualism among Israeli Arabs, and the neuropsychology of reading in different languages. Literacy Studies, 5, 57-74. Ibrahim, R., Eviatar, Z., & Aharon Peretz, J. (2002). The characteristics of the Arabic orthography slow it’s cognitive processing. Neuro- psycholgy, 16, 322-326. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.16.3.322 Ibrahim, R., Eviatar. Z., & Aharon Peretz, J. (2007). Metalinguistic awareness and reading performance: A cross language comparison. The Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 36, 297-317. doi:10.1007/s10936-006-9046-3 Ibrahim, R. (2009). The cognitive basis of diglossia in Arabic: Evi- dence from a repetition priming study within and between languages. Psychology Research and Behavior Manag em en t, 12, 95-105. Maamouri, M. (1998). Language education and human development: Arabic diglossia and its impact on the quality of education in the Arab region. The Mediterranean Development Forum. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Paradis, M. (2009). Declarative and procedural determinants of second languages (studies in bilingualism 40). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Rao, C., Vaid, J., Srinivasan, N., & Chen, H. C. (2011). Orthographic characteristics speed Hindi word naming but slow Urdu naming: Evidence from Hindi/Urdu biliterates. Reading and Writing, 24, 679- 695. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9256-9 Roman, G., & Pavard, B. (1987). A comparative study: How we read Arabic and French. In J. K. O’Regan, & A. Levy-Schoen (Eds.), Eye movements from physiology to cognition (pp. 431-440). Amsterdam: North Holland Elsevier. Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2003). Linguistic distance and initial reading ac- quisition: The case of Arabic diglossia. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 115-135. doi:10.1017/S0142716403000225 Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2004). The impact of phonemic and lexical dis- tance on the phonological analysis of words and pseudowords in a diglossic context. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25, 495-512. doi:10.1017/S0142716404001249 Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2005). Correlates of reading fluency in Arabic: Di- glossic and orthographic factors. Reading and Writing: An Interdis- ciplinary Journal: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 559-582. doi:10.1007/s11145-005-3180-4 Share, D. L., Jorm, A. F., Maclean, F., & Matthews, R. (1984). Sources of individual differences in reading acquisition. Journal of Educa- tional Psychology, 7 6, 1309-1324. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.76.6.1309 Shatil, E., Share, D. L., & Levin, I. (2000). On the contribution of kin- dergarten writing to Grade 1 literacy: A longitudinal study in He- brew. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 1-25. Shimron, J., & Navon, D. (1982). The dependence on graphemes and on their translation to phonemes in reading: A developmental per- spective. Reading Research Quarterly, 17, 210-228. doi:10.2307/747484 Taha, H., Ibrahim, R., & Khateb, A. (2012). How does Arabic ortho- graphic connectivity modulate brain activity during visual word rec- ognition: An ERP study. Brain Topography, 26, 292-302. doi:10.1007/s10548-012-0241-2 Taouk, M., & Coltheart, M. (2004). Learning to read in Arabic. Read- ing and Writing, 17, 27-57. doi:10.1023/B:READ.0000013831.91795.ec

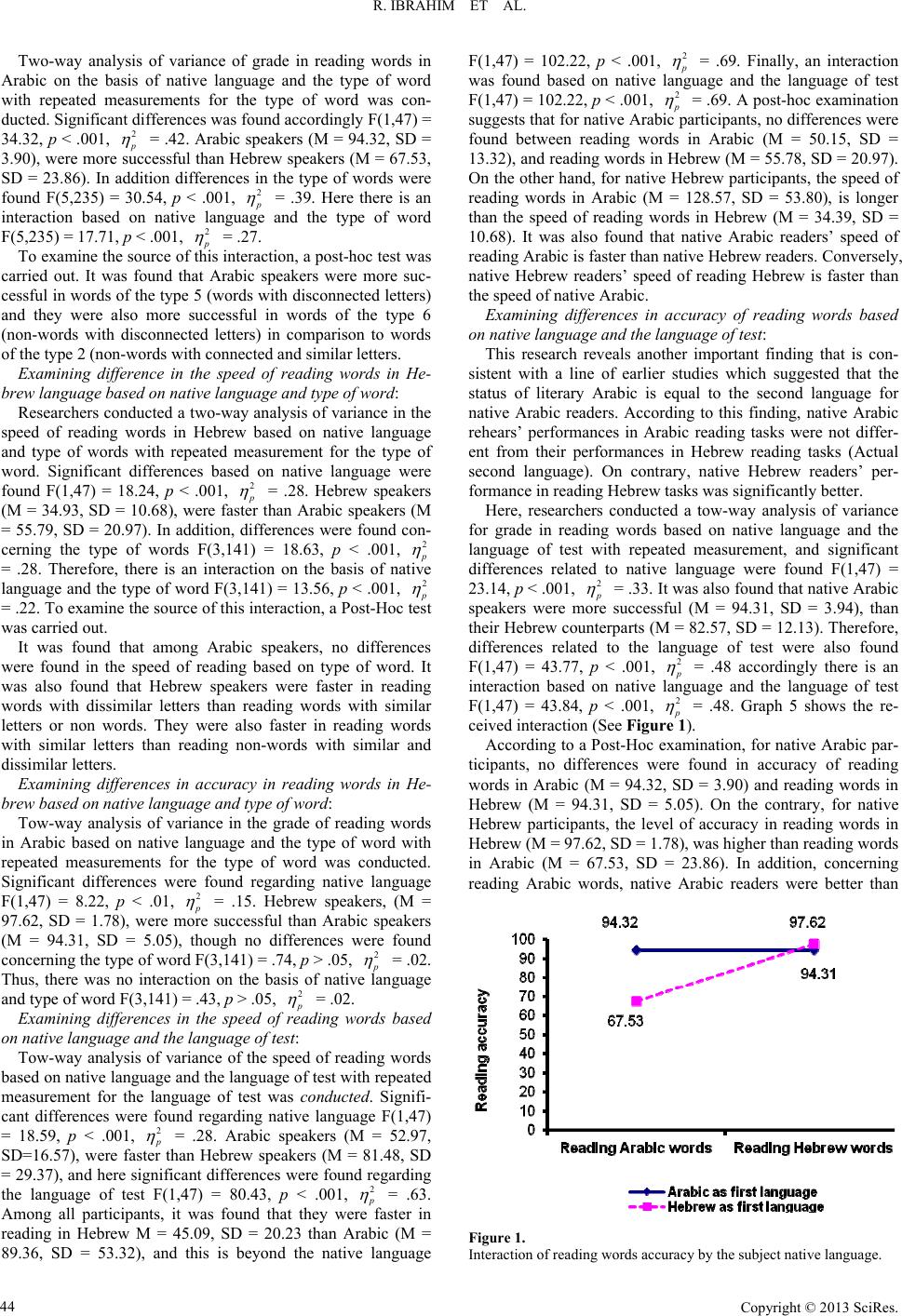

|