Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.3A, 349-355 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.43A051 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 349 Occupational Stress and Professional Burnout in Teachers of Primary and Secondary Education: The Role of Coping Strategies Alexander-Stamatios Antoniou1, Aikaterini Ploumpi2, Marina Ntalla1 1University of Athens, Athens, Greece 2Institution of Childcare G. & A. Chatzikonsta, Athens, Greece Email: info@as-antoniou.gr, katerina_ploubi@yahoo.gr, marinantalla@yahoo.gr Received December 21st, 2012; revised January 22nd, 2013; accepted February 17th, 2013 This research investigates the levels of occupational stress and professional burnout of teachers of pri- mary and secondary education. It also aims to investigate the coping strategies that they adopt, and the relationship between them. The survey involved 388 teachers who teach in public schools in Attica. Three instruments were administrated to teachers: “Teachers’ Occupational Stress” (Antoniou, Polychroni, & Vlachakis, 2006), the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1986) and the “Stress Coping Strategies Scale” (Cooper, Sloan, & Williams, 1988). The findings showed that teachers of Primary Edu- cation experience higher levels of stress compared to the teachers of Secondary Education. Female teach- ers experience more stress and lower personal accomplishment than men. Rational coping behaviors are a resource which help teachers overcome work-related stressors and burnout and achieve their valued outcomes with students, while avoidance coping predicted high level of stress and burnout. Keywords: Teachers’ Stress; Burnout; Coping Strategies Introduction Stress experienced by teachers is a subject of intense interest in recent years. Various factors have been identified linked with teacher’s occupational stress. The most important of these fac- tors are: business requirements, many different activities within the school environment, lack of professional recognition, disci- pline problems in the classroom, bureaucracy, lack of support, workload, time pressure, lack of benefits (Mearns & Chain, 2003). It has been argued that when teachers feel that they in- vest more in students, colleagues, and school than they receive from them, then they are more likely to face emotional, psy- chological and occupational difficulties (Van Horn, Schaufeli, & Taris, 2001). The sources of stress experienced by a particu- lar teacher are unique to him/her and depend on the interaction between personality, values and skills and the circumstances. All mentioned stressors have been shown to lead to teachers’ burnout. The burnout syndrome is described as emotional exhaustion which is the result of chronic stress and particularly occurs in people who are in contact with other people professionally. It comprises three components: emotional exhaustion, deperson- alization and lack of personal accomplishment/achievement (Montgomery & Rupp, 2005). There is evidence showing that newly appointed teachers who actually tend to think the resig- nation are more prone to experiencing burnout. However, many researchers argue that the intense occupational stress does not necessarily mean burnout. Among the most important factors that affect teachers is role ambiguity, role conflict (Kantas, 1995), workload, time pressure (Tsiakkiros & Piasiardis, 2002), lack of autonomy and self-motivation (Olivier & Williams, 2005), lack of participation in decision-making (Kantas, 1995), competitive relationships between the teacher and his/her col- leagues or superiors, lack of recognition of the professional role, methods of disengagement from a stressful situation (Riolli & Savicki, 2002), levels of personal satisfaction, the fulfillment or frustration of expectations and the clash of values. It has been found that changes in teachers’ perceptions of classroom over- load and students’ disruptive behavior are negatively related to changes in autonomous motivation, which in turn negatively predict changes in emotional exhaustion (Fernet, Guay, Senec- tal, & Austin, 2012). Moreover, demographic characteristics such as age, sex, class level, marital status and the cultural con- text play a significant role in teacher burnout (Schwab, Jackson, & Schuler, 1986). As far as Greek data is concerned, job demands affect burn- out (Pomaki & Anagnostopoulou, 2003) and Greek teachers experience high levels of stress (Antoniou, Polychroni, & Vla- chakis, 2006; Kantas, 2001). Overall, research shows that Greek teachers experience lower levels of burnout than colleagues in other countries (Kantas, 2001; Polychroni & Antoniou, 2006). Indeed, a study of Papastylianou, Kaila and Polychronopoulos (2009) found that teachers experience positive emotions of per- sonal accomplishment that help them cope with grief and lack of pleasure. Based on previous studies, there are gender differences in all three burnout syndromes and teachers’ occupational stress. Women teachers experience higher levels of burnout, parti- cularly emotional exhaustion (Antoniou, Polychroni, & Vala- chakis, 2006) and lack of personal achievement, but less de- personalization than male teachers (Lau, Yuen, & Chan, 2005). Moreover, Yavuz (2009) found that men experience higher depersonalization. Also, Maslach, Jackson and Leiter (1996) reported that women teachers showed higher emotional ex- haustion than men. In contrary, Zhao and Bi (2003) found no difference in the three burnout syndromes between women and men teachers of secondary education. Previous research in  A.-S. ANTONIOU ET AL. Greece indicated that female teachers experience higher levels of stress and greater job dissatisfaction that usually comes from negative classroom conditions, pupils’ behavior and the work and family interaction (Kantas, 2001). The findings that are focused on comparing levels of burnout of primary and secondary school teacher are of great interest. In Anderson and Iwanicki’s research (1984), the secondary school teachers reported higher levels of burnout as compared to pri- mary school teachers. In a survey conducted in Hong Kong, Mo (1991) found that the phenomenon of burnout was present at secondary teachers. Other studies have also confirmed that tea- chers who teach older children have lower levels of teaching performance (Polychroni & Antoniou, 2006). In addition, tea- chers of younger students experience the lowest levels of burn- out, while this is not the same for their colleagues who teach older students (Kantas, 1996). Bakker, Demerouti and Euwema (2005) stated that teachers of secondary education are less ef- fective in relation to primary school teachers. Several studies indicate that work environment is important predictor of beginning teachers’ burnout (Friedman, 2000; God- dard, O’Brien, & Goddard, 2006). According to Freidman (2000), the transition from schooling to work is often harsh, and re- flects the “shattered dreams”. The teachers’ experience at the beginning may be termed a “reality shock” as they know the school and classroom reality. The reality shock phenomenon is related to their training failed to provide them with the needed knowledge for handling student discipline problems and class- room behavior disturbances. It has been shown that the coping strategies, personality traits and the environment can affect the level of stressful situations that are recruited. According to Lazarus and Folkman stress and coping model (1984), when a person is confronted with a stressful event he/she is involved in a process of primary ap- praisal. Whether the state will be considered as stressful is de- pendent on the person and the situation. Then the person makes a secondary consideration. In this process the individual en- gages in a cognitive assessment of personal and environmental reserves to cope with the stressful event. In other words, the primary assessment refers to assessing the stressor of the situa- tion, while the secondary refers to assessing the ability of indi- viduals to cope with the situation. Both types are cognitive assessment procedures which rely heavily on personal assess- ment. Various kinds of strategies have been proposed in the litera- ture. For example, the response may relate to managing the problem that causes stress and to easing the emotional reaction to the problem. The first refers to the problem-oriented coping while the second to the emotion-oriented coping (Admiraal, Korthagen, & Wubbels, 2000). The problem-oriented coping includes coping strategies and problem solution such as prob- lem definition, identification of alternatives, evaluation of al- ternatives in terms of costs and benefits of such a choice. The emotion-oriented coping includes positive reappraisal and com- parison as well as defense strategies such as avoidance and detachment. People will adopt the emotion-oriented coping when they think they cannot do anything to change the envi- ronmental conditions. In contrast, they adopt a problem-ori- ented coping when they consider environmental conditions as malleable. Chan (1998) found that the type of coping strategies affects teachers’ emotional health. Similar results were reported in Sweden, where the use of active coping strategies seemed to mitigate the negative effects of teacher work stress (Brenner, Sorbom, & Wallius 1985). The social and emotional support by significant others has also been shown to benefit teachers under pressure (Burke, Greenglass, & Schwarzer 1996). Instead, the avoidance of the problem can aggravate pressure (Chan, 1998). A survey of Griva and Joekes (2003) showed that the use of problem-oriented strategies was associated with lower levels of depersonalization while high levels of meaning, problem-ori- ented strategies and environmental risk were associated with high levels of personal achievement. The present study aims to investigate the levels of occupa- tional stress and professional burnout and examine the coping strategies adopted by Greek teachers of public primary and secondary schools according to gender, education level and years of service. Finally, the link between stress and burnout with coping strategies related to teachers of primary and sec- ondary education is investigated. The research questions were as follows: 1) Are there differences in occupational stress, burn- out and coping strategies between teachers of primary educa- tion and teachers of junior and senior high education? 2) Are there differences in occupational stress, burnout and coping strategies between male and female teachers? 3) Are there dif- ferences in occupational stress and burnout as to the years of teaching? 4) Do the coping strategies predict occupational stress and burnout? According to our predictions, female teachers should report higher level of occupational stress and burnout. The gender dif- ferences can be explained by social theory, which refers to wo- men’s sensitivity and empathic abilities as a result of which women’s self is a self in relation with others (Pines & Ronen, 2011). The second hypothesis refers to the association between teachers’ stress, burnout and education levels, junior and senior high education. The results of different studies indicate the need for research for better understanding the different burnout pat- terns among the two education levels. From the fact that the teachers who teach older children have lower levels of teaching performance (Polychroni & Antoniou, 2006), we assumed that they have higher level of stress and burnout than their col- leagues of primary education. Third, we tried to explain any emerging difference in teachers’ occupational stress and burn- out according to the years of practicing the occupation. We assumed that teachers with few years of teaching experience could exhibit higher levels of stress and burnout that teachers with many years of teaching experience. Finally, we assumed that coping strategies should predict occupational stress and burnout. Specifically, positive approach, task strategy and ra- tional problem solving strategy should predict lower level of occupational stress and burnout and higher level of personal accomplishment. In contrary, avoidance coping should lead to higher levels of occupational stress and burnout and lower level of personal accomplishment. Method Participants The sample consisted of 388 Greek teachers (37.9% males and 62.1% females) of public primary (53.6%) and secondary (46.4%) schools working in Attica, Greece. As for age, 59.6% of teachers of primary schools were aged up to 40 years and 40.4% of teachers of secondary schools aged over 40 years. The average years of teaching experience were 16.2 with a range Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 350  A.-S. ANTONIOU ET AL. from 1 to 35 years. Specifically, the teaching experience of 55 (14.2%) teachers was from 1 - 5 years, 66 (17.1%) teachers had teaching experience from 6 - 10 years, 76 (19.6%) of all sample worked from 11 - 15 years and 190 (49.1%) of the teachers worked over 16 years. Instruments The questionnaire “Teachers’ Occupational Stress” (Antoniou et al., 2006) was used, which included 30 statements referring to the degree of stress caused by occupational stressors. Teach- ers identify the level of stress that they experience at a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “it is not stressful at all” to 6 “it is very stressful”. The occupational stressors were: a) work- ing conditions (α = 0.89); b) teachers’ workload (α = 0.88); c) pupils’ interest in learning (α = 0.76); d) support and recogni- tion from the state (α = 0.74). Professional burnout was assessed by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-ED version for teachers) developed by Mas- lach and Jackson (1986). This scale has been used before with Greek teaching populations (Antoniou et al., 2000; Kantas, 2001). It consists of 22 statements where the respondents iden- tify how often they feel professional burnout at a seven-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from 0 “never” to 6 “every day” (reliability was calculated at α = 0.68). The three dimen- sions of professional burnout assessed by this tool are: a) emo- tional exhaustion (α = 0.84); b) depersonalization (α = 0.67); c) reduced personal accomplishment (α = 0.78). The scale “Stress Coping Strategies” (from the Occupational Stress Indicator by Cooper, Sloan & Williams, 1988 translated by A-S Antoniou) was also used. Teachers identify different strategies people used to overcome stressful situations at a six-point scale ranging from 1 “I do not use this option/way” to 6 “I always use this option/way”. It consists of 28 statements which resulted in 4 factors: a) avoidance (α = 0.68); b) positive approach (α = 0.84); c) action strategies (α = 0.71); d) logical problem solving (α = 0.68). The last part of the questionnaire administered to teachers contained general questions about teachers’ sex, age, years of practicing their profession, etc. Procedure The questionnaires were administered individually in pri- mary and secondary teachers of public schools in Attica. The research team met the teachers to explain the research. The questionnaires were anonymous and the instructions given to teachers were to answer as honestly and spontaneously as possible to all questions. Necessary and very important for the completion of the questionnaires was the reassurance that researchers respect the confidentiality of their responses. After distributing the surveys and giving detailed instructions, 400 teachers completed questionnaires. After excluding individuals due to missing data on demographic variables, the final sample consisted of 388 individuals. Results Occupational Stress, Burnout and Coping Strat egies by School Level and Gender The influence of the school level (teachers of Primary School and teachers of Junior High and Senior High School) and gen- der (male and female) in occupational stress, burnout and cop- ing strategies was tested using a multivariate model using SPPS 20 version. Three multivariate analyses were conducted. The factors of occupational stress, burnout and coping strategies were the dependent variables, while school and gender were the independent variables. Occupational stress, school level and gender. According to multivariate analysis of variance teachers of primary education compared with teachers of Junior and Senior High Education reported higher level of occupational stress in all variables: workload F(1, 384) = 6.76, p < 0.01, η2 = 5% working condi- tions F(1, 384) = 56.7, p < 0.001, η2 = 13%, interest of students F(1, 384) = 5.77 p < 0.05, η2 = 1.5% and lack of support from government F(1, 384) = 26.1, p < 0.001, η2 = 6%. Women seemed to experience more workload than men F(1, 384) = 21.1, p < 0.001, η2 = 5%. They reported more problems in working conditions F(1, 384) = 18.8, p < 0.001, η2 = 4.7% and in motivation of student F(1, 384) = 20.1, p < 0.001, η2 = 5%. Finally, they reported higher level of lack of support from gov- ernment compared with teachers of junior and senior school F(1, 384) = 11.2, p < 0.01, η2 = 2.8%. Burnout, school level and gender. Only emotional exhaustion was different between teachers of Primary and teachers of Jun- ior and Senior High Education F(1, 383) = 51.7, p < 0.001, η2 = 12%. Teachers of Primary education deemed to experience higher emotional exhaustion than teachers of Junior and High Education. Again, women reported higher emotional exhaustion than men F(1, 383) = 6.58, p < 0.05, η2 = 1.7%. Coping strategies, school level and gender. Teachers of Pri- mary education reported using the avoidance strategy more than teachers of Junior and Senior High Education F(1, 384) = 22.26, p < 0.001, η2 = 5.5%. Women use positive approach F(1, 384) = 8.27, p < 0.01, η2 = 2.1% and avoidance strategy F(1, 384) = 6.05, p < 0.05, η2 = 1.6% more than men. Occupational Stress, Burnout and Coping Strat egies by Years of T eac hi ng The influence of the years of teaching was tested using a univariate model. Three one way analyses of variance were conducted. The factors of occupational stress, burnout and coping strategies were the dependent variables, while years of teaching was the independent variables (Table 2). One way analysis of variance indicated that teachers practicing their profession from 11 - 15 years reported higher scores of stress in working conditions than other teachers’ groups. Teachers prac- ticing their profession more than 16 years reported lower level score of stress in working conditions than other groups. The mean score of teachers working from 1 - 10 years is higher from the mean score of teachers practicing their profession from 11 - 15 years and lower from the mean score of teachers working in school more than 16 years F(3, 385) = 4.31, p < 0.01. Teachers practicing their profession from 11 - 15 years reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion, while teachers practicing their profession more than 15 years indicated lower level of emotional exhaustion. The mean score of teachers practicing their profession from 1 - 10 years is higher than the mean score of their colleagues working over 16 years and lower than the mean score of colleagues’ mean score working 11 - 15 years F(3, 385) = 6.91, p < 0.001. There were no differences egarding coping strategies. r Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 351  A.-S. ANTONIOU ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 352 Table 1. Means of occupational stress, burnout and coping strategies as a function of school level. School level Gender Prima Second MaleFemale Μ. Μ. F η2 Μ. Μ. F η2 Occupational stress Workload 3.45 3.22 6.76** 0.05 3.13 3.99 21.1*** 0.05 Working conditions 3.86 3.19 56.7*** 0.13 3.33 3.72 18.8*** 0.047 Interest of students 3.89 3.67 5.77* 0.015 3.58 3.99 20.1*** 0.05 Lack of support from gov/ment 3.17 2.77 26.1*** 0.06 2.84 3.10 11.2** 0.028 Burnout Emotional exhaustion 2.40 1.58 51.7*** 0.12 1.84 2.13 6.58* 0.017 Depersonalisation 1.05 0.90 2.61 0.007 1.03 0.92 1.45 0.004 Personal accomplishment 4.70 4.57 2.05 0.005 4.71 4.56 2.79 0.007 Coping strategies Positive approach 4.51 4.47 0.38 0.001 4.39 4.60 8.27** 0.021 Task strategies 4.76 4.86 1.79 0.005 4.74 4.88 3.62 0.009 Rational problem solving 4.49 4.63 3.38 0.009 4.63 4.50 2.75 0.007 Avoidance 3.47 3.13 22.26*** 0.055 3.21 3.39 6.05* 0.016 Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Table 2. Means of occupational stress, burnout and coping astrategies as a function of years of teaching. 1 - 5 6 - 10 11 - 15 Over 16 years F Μ. Μ. Μ. Μ. Occupational stress Workload 3.42 3.35 3.53 3.34 0.90 Working conditions 3.68 ab 3.66 ab 3.86 a 3.44 b 4.31** Interest of students 3.95 3.81 3.86 3.81 0.37 No support from government 3.25 3.01 3.13 2.91 3.43 Burnout Emotional exhaustion 2.03ab 2.32 ab 2.44a 1.81b 6.91*** Depersonalisation 0.95 1.15 1.01 0.88 1.61 Personal accomplishment 4.59 4.57 4.77 4.57 1.03 Coping strategies Positive approach 4.65 4.49 4.52 4.50 0.75 Task strategies 4.82 4.77 4.80 4.85 0.29 Rational problem solving 4.55 4.47 4.43 4.61 1.42 Avoidance 3.33 3.43 3.38 3.28 0.84 Note: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Means sharing a common subscript do not differ significantly according to Bonferroni post hoc criterion for α = 0.05. Regression Analyses Predicting Occupational Stress from Gender, Years of Teaching, School Level and Coping Strategies Separate regressions were performed using SPPS 20 version to examine relations between occupational stress and coping strategies. In these analyses entry order was as follows: Step 1 was “gender”, step 2 was “years of teaching”, step 3 was “school level” and step 4 was “coping strategies” (Table 3). According to results, higher rational problem solving, was re- lated to lower stress from workload β = –0.16, t = –3.07, p < 0.01 and working conditions β = –0.14, t = –2.81, p < 0.01. Higher avoidance of problems was linked to higher stress from workload β = 0.37, t = 7.54, p < 0.001, working conditions β = 0.37, t = 8.00, p < 0.001, low interest of students β = 0.24, t = 4.57, p < 0.001 and lack of support from government β = 0.16, t  A.-S. ANTONIOU ET AL. = 3.09, p < 0.01. Group of female teachers was related to higher level of stress from workload β = 0.16, t = 3.32, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.048, working conditions β = 0.14, t = 3.22, p < 0.01, R2 =0.041, low interest of students β = 0.17, t = 3.44, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.047 and lack of support from government β = 0.12, t = 2.28, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.026. Finally, teachers of primary schools re- ported more stress regarding working conditions β = 0.25, t = 5.45, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.12 and lack of support from government β = 0.18, t = 3.55, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.049. Separate regressions were performed to examine relations between burnout and coping strategies. In these analyses entry order was as follows: Step 1 was “gender”, step 2 was “years of teaching”, step 3 was “school level” and step 4 was “burnout” (Table 4). Results indicated that higher rational problem solv- ing, was related to lower emotional exhaustion β = –0.14, t = –2.70, p < 0.01 and lower depersonalization β = –0.11, t = –1.99, p < 0.05. Higher avoidance of problems was linked to higher emotional exhaustion β = 0.25, t = 5.23, p < 0.001 and depersonalization β = 0.23, t = 4.42, p < 0.001. Positive ap- proach β = 0.16, t = 2.94, p < 0.01, task strategies β = 0.15, t = 2.68, p < 0.01 and rational problem solving β = 0.15, t = 2.72, p < 0.01 were related to high level of personal accomplishment. Finally, teachers of primary schools reported higher emo- tional exhaustion β = 0.27, t = 5.1, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.13. Fe- males reported lower personal accomplishment β = –0.10, t = –2.07, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.008. Discussion In this study we investigated levels of teacher occupational stress among teachers as the consequence of task demands that teachers face in performing their professional roles and responsibilities (Steyn & Kamper, 2006), burnout and coping strategies. Our main finding is that rational coping behaviors is a resource which helps teachers overcome job-related stressors and achieve their valued outcomes with students. Previous research has shown that problem solving strategies help people obtain information about what to do and act accordingly to Table 3. Regression analyses predicting occupational stress from coping strategies Occupational stress Workload Working conditions Interest of students Lack of support Predictors β β β β 1. Gender 0.16** 0.14** 0.17*** 0.12* 2. Years of teaching 0.06 0.01 0.02 –0.05 3. School level 0.005 0.25*** 0.05 0.18*** 4. Coping strategies Positive approach 0.10 0.04 0.10 0.01 Task strategies –0.05 –0.04 –0.04 0.03 Rational problem solving –0.16** –0.14* –0.09 –0.12* Avoidance 0.37*** 0.37*** 0.24*** 0.16** Total R2 0.22 0.31 0.13 0.12 Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Table 4. Regression analyses predicting burnout from coping strategies. Burnout Emotional exhaustion Depersonalisation Personal accomplishment Predictors β β β 1. Gender 0.06 –0.09 –0.10* 2. Years of teaching –0.009 –0.06 –0.001 3. School level 0.27*** 0.01 0.08 4. Coping strategies Positive approach 0.007 –0.08 0.16** Task strategies –0.07 –0.09 0.15** Rational problem solving –0.14** –0.11* 0.15** Avoidance 0.25*** 0.23*** –0.10 Total R2 0.23 0.10 0.13 N ote: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 353  A.-S. ANTONIOU ET AL. change the situation (Lazarus, 1999). The positive correlation between avoidance coping and teachers’ occupational stress indicated that teachers denying the existence of the problem without changing the situation are ineffective in overcoming negative outcomes of numerous stressors including heavy workload, work conditions, lack of students’ motivation and low support by the government. The results indicated that levels of stress experienced by teachers may be dependent on the coping strategies that the teachers employ. Previous studies indicated that teacher with lower levels of stress used more active coping strategies while teachers with higher levels of stress used more passive coping strategies (Austin, Shah, & Muncer, 2005). Coping strategies may also be an important variable in rela- tion to burnout. Specifically, positive approach of the problem, task strategies and problem solving predict high level of per- sonal accomplishment, while avoidance of the problem is a po- sitive predictor of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Furthermore, problem solving coping appeared to contribute to the low level of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization felt by teachers. The results are consistent with a number of studies reported a relationship between teacher burnout and coping strategies (Betoret & Artiga, 2010). Avoidance coping was found to be associated with higher level of emotional exhaus- tion, and depersonalization (Austin, Shah & Munce, 2005). Moreover the study explored how stress and burnout of teachers were related to important variables, such as gender, teaching experience and school level. The findings indicated that women reported significantly higher level of occupational stress and lower level of personal accomplishment. This finding is confirmed in other studies (e.g. Rout & Rout, 2002) that refer to social role theory, gender roles and gender role expectations (Pines & Ronen, 2011). Regarding teaching experience, our study indicated that teachers with 11 - 15 years of teaching experience reported higher level of stress from working con- ditions and emotional exhaustion than teachers with 1 - 10 years and above 15 years of experience. Teachers above 15 years of teaching experience showed the low level of stress from working conditions and emotional exhaustion, while the stress and emotional exhaustion of beginning teachers is lower compared to teachers above 16 years of experience and higher compared to teachers with 11 - 15 years. Our results are not in consistence with the theory about the vulnerability of the transi- tion from being a student to being a teacher (Conroy, 2004). According to our results, the curve line reflect the teachers stress and emotional exhaustion. This could be explained by the fact that teachers who do not work for many years invest a lot of energy in order to adapt to their professional role, thus experiencing intense stress. On the other hand, after many years experience teachers feel more adapted to school environment and working conditions. Finally, teachers of Primary Education experience more stress as compared to the teachers of Secondary Education. The stressor linked to teacher stress are working conditions and low support from the government. However, there is a view (Kantas, 2001) that in recent years Greek primary schools have become a field of many changes and reforms, and new conditions cause negative emotions and stress on teachers more than in the past. Other studies indicated the same results. For example, Izgar (2003) found that levels of emotional exhaustion and deper- sonalization are higher among primary school teachers than secondary school teachers. There was no difference in personal achievement. In conclusion, it appears that the sources and the conse- quences of teachers’ occupational stress and burnout and the adoption of specific strategies for dealing with stressors in the workplace are complicated. For this reason, it is necessary that all parameters to be taken into account in the design and im- plementation of primary and secondary prevention programs addressed to teachers with the aim of preventing or reducing teacher stress. Teachers’ effective use of coping strategies could serve as a factor which helps prevent work-related stress and burnout. Further research is needed to identify more spe- cific factors that lead to occupational stress and burnout and to investigate the coping strategies that teacher use and their relation to occupational stress and burnout. Limitations and Future Research This study had several limitations that can be addressed by future research. Firsts, the sample consists only of teachers who work in public primary and secondary schools of the Capital of Greece. So, it is not representative of all teachers of primary and secondary schools. Hence, a more representative sample might yield different results; for example, a sample from dif- ferent areas of Greece might show significant interaction effects of education level and area. Second, the study of other variables, such as personality or family variables may play important role in predicting occupational stress and burnout. Thus, future research can also collect more variables related to stress and burnout of teachers. Third, the longitudinal design is important to investigate the development of stress and burnout among teachers (beginning teachers and teachers with experience over 6 years) (Goddard et al., 2006). REFERENCES Admiraal, W. F., Korthagen, F. A. J., & Wubbels, T. (2000). Effects of student-teachers’ coping behavior. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 33-52. doi:10.1348/000709900157958 Anderson, M. B., & Iwanicki, E. F. (1984). Teacher motivation and its relationship to burnout. Educational Administration Quarterly, 20, 94-132. doi:10.1177/0013161X84020002007 Antoniou, A. S., Polychroni, F., & Vlachakis, A. N. (2006). Gender and age differences in occupational stress and professional burnout be- tween primary and high-school teachers in Greece. Journal of Man- agerial Psychology, 21, 682-690. doi:10.1108/02683940610690213 Austin, V., Shah, S., & Muncer, S. (2005). Teacher stress and coping strategies used to reduce stress. Occupational Therapy International, 12, 63-80. doi:10.1002/oti.16 Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupa- tional Health Psychology, 10, 170-180. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170 Betoret, F. D., & Artiga, A. G. (2010). Barriers perceived by teachers at work, coping strategies, self-efficacy and burnout. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13, 637-654. Brenner, S. O., Sorbom, D., & Wallius, E. (1985). The stress chain: A longitudinal confirmatory study of teacher stress, coping, and social support. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58, 1-13. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1985.tb00175.x Burke, R. J., Greenglass, E. R., & Schwarzer, R. (1996). Predicting teacher burnout over time: effects of work stress, social support, and self-doubts on burnout and its consequences. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 9, 261-275. doi:10.1080/10615809608249406 Chan, D. W. (1998). Stress, Coping strategies, and psychological dis- tress among secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. American Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 354  A.-S. ANTONIOU ET AL. Educational Research Journal, 35, 145-163. Conroy, J. C. (2004). Betwixt and between: The liminal imagination, education and democracy. New York: Peter Lang. Cooper, C. L., Sloan, S. L., & Williams, S. L. (1988). Occupational stress indicator management guide. Windsor: Nfer-Nelson. Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senectal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting in- traindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Educa- tion, 28, 514-525. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013 Friedman, I. A. (2000). Burnout in teachers: Shattered dreams of im- peccable professional performance. JCLP/In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice, 56, 595-606. Goddard, R., O’Brien, P., & Goddard, M. (2006). Work environment predictors of beginning teacher burnout. British Educational Re- search Journal, 32, 857-874. doi:10.1080/01411920600989511 Griva, K., & Joekes, K. (2003). UK teachers under stress: can we pre- dict wellness on the basis of characteristics of the teaching job? Psy- chology and Health, 18, 457-471. doi:10.1080/0887044031000147193 Izgar, H. (2003). Burnout at school directors. Ankara: Nobel Yayin Dagitim. Kantas, A. (1995). Group processes-conflict-development and change- culture-occupational stress. Athens: Greek Letters. Kantas, A. (1996). The burnout syndrome of teachers and people who work to health professionals. Psychology, 3, 71-85. Kantas, A. (2001). The anxiety factors and the burnout of teachers. In E. Vasilaki, S. Triliva, & E. Besevegis (Ed.), (pp. 217-229). Athens: Greek Letters. Lau, P. S. Y. M., Yuen, M. T., & Chan, R. M. C. (2005). Do demo- graphic characteristics make a difference to burnout among Hong Kong secondary school teachers? Social Indicators Research, 71, 491- 516. doi:10.1007/s11205-004-8033-z Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer Publishing Co. Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alot, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc. Mearns, J., & Cain, J. E. (2003). Relationships between teachers’ oc- cupational stress and their burnout and distress: Roles of coping and negative mood regulation expectancies. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 16, 71-82. doi:10.1080/1061580021000057040 Mo, K. W. (1991). Teacher burnout: Relations with stress, personality, and social support. Education Journal, 19, 3-12. Montgomery, C., & Rupp, A. (2005). A meta-analysis for exploring the diverse causes and effects of stress in teachers. Canadian Journal of Education, 28, 461-488. doi:10.2307/4126479 Olivier, M., & Williams, E. (2005). Teaching the mentally handicapped child: Challenges teachers are facing. The International Journal of Special Education, 20, 19 -31. Papastylianou, A., Kaila, M., & Polychronopoulos, M. (2009). Teach- ers’ burnout, depression, role ambiguity and conflict. Social Psy- chology of Education, 12, 295-314. doi:10.1007/s11218-008-9086-7 Pines, A. M., & Ronen, S. (2011). Gender differences in burnout. In A. S. Antoniou, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), New directions in organiza- tional psychology and behavioral medicine (pp. 107-122). Burlington: Gower Publishing Company. Polychroni, F., & Antoniou, A. S. (2006). Occupational stress and burn- out of Greek teachers of primary and secondary education. In X. F. Papailiou, G. Ksanthakou, & S. Xatzichristou (Eds.), Educational and school psychology (pp. 161-186). Athens: Atrapos. Pomaki, Y., & Anagnostopoulou, T. (2003). A test and extension of the demand/control/social support model: Prediction of health- and work- related outcomes in Greek teachers. Psychology and Health, 18, 537- 550. doi:10.1080/0887044031000147256 Riolli, L., & Savicki, V. (2002). Optimism and coping as moderators of the relationship between chronic stress and burnout. Psychological Repairing, 92, 1215-1226. doi:10.2466/PR0.92.3.1215-1226 Rout, U. R., & Rout, J. K. (2002). Stress management for primary health professionals. New York: Kluwer Acadamic/Plenum Publish- ers. Schwab, R., Jackson, S., & Schuler, R. (1986). Educator burnout: Sources and consequences. Educational Research Quarterly, 10, 14-30. Steyn, G. M., & Kamper, G. D. (2006). Understanding occupational stress among educators: an overview. Africa Education Review, 3, 113-133. doi:10.1080/18146620608540446 Tsiakkiros, A., & Pasiardis, P. (2002). Occupational stress of teachers and school principals. Paidagogical Review, 33, 195-213. Van Horn, J. E., Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2001). Lack of re- ciprocity among Dutch teachers: Validation of reciprocity indices and their relation to stress and well-being. Work and Stress, 15, 191- 213. doi:10.1080/02678370110066571 Yavuz, M. (2009). An investigation of burn-out levels of teachers working in elementary and secondary educational institutions and their attitudes to classroom management. Educational Research and Reviews, 4, 642-649. Zhao, J. L., & Bi, H. H. (2003). On the completeness of logic-based workflow verification. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Workshop on Information Technologies and Systems (WITS 2003), Seattle, WA, 13-14 December, 73-78 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 355

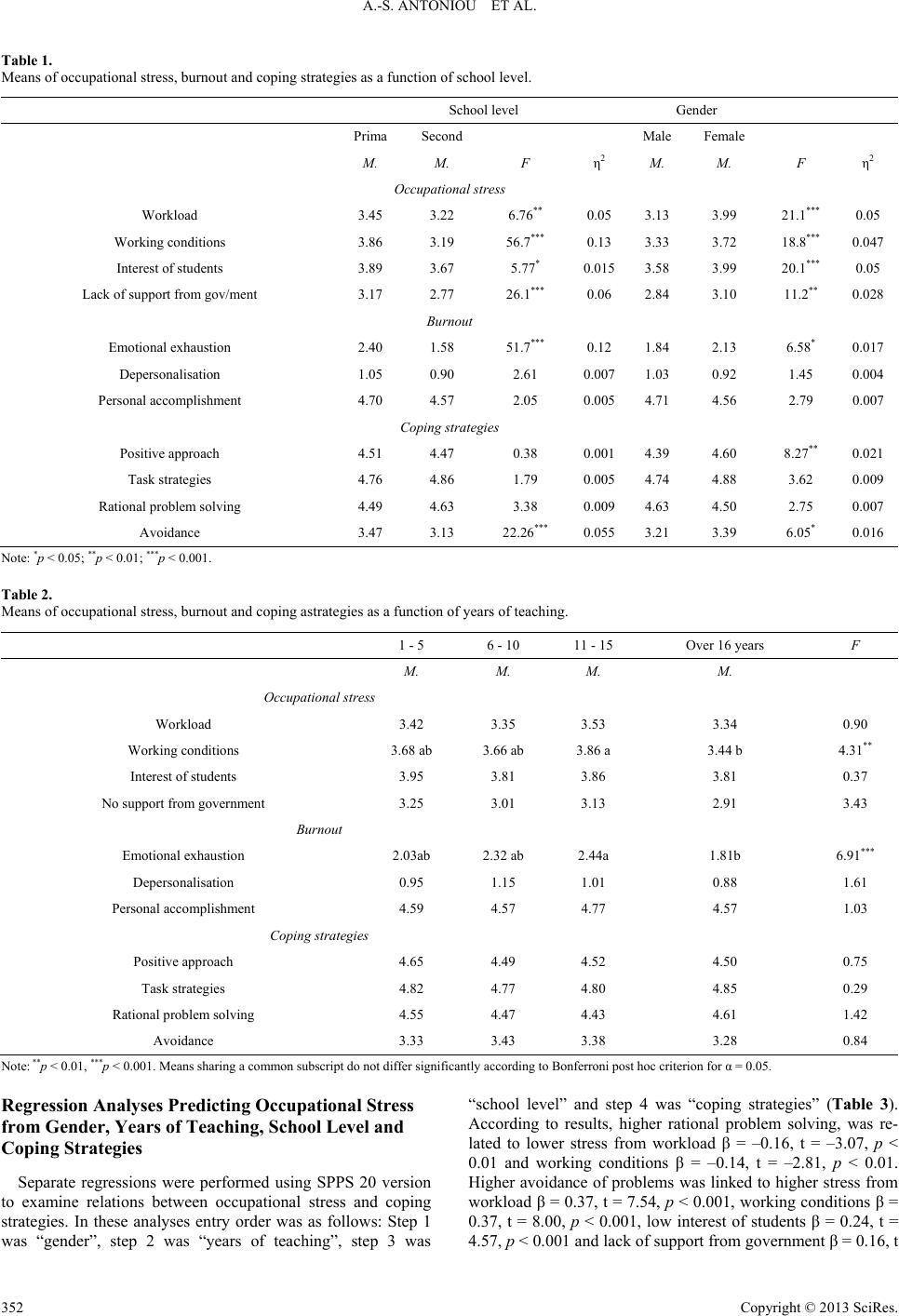

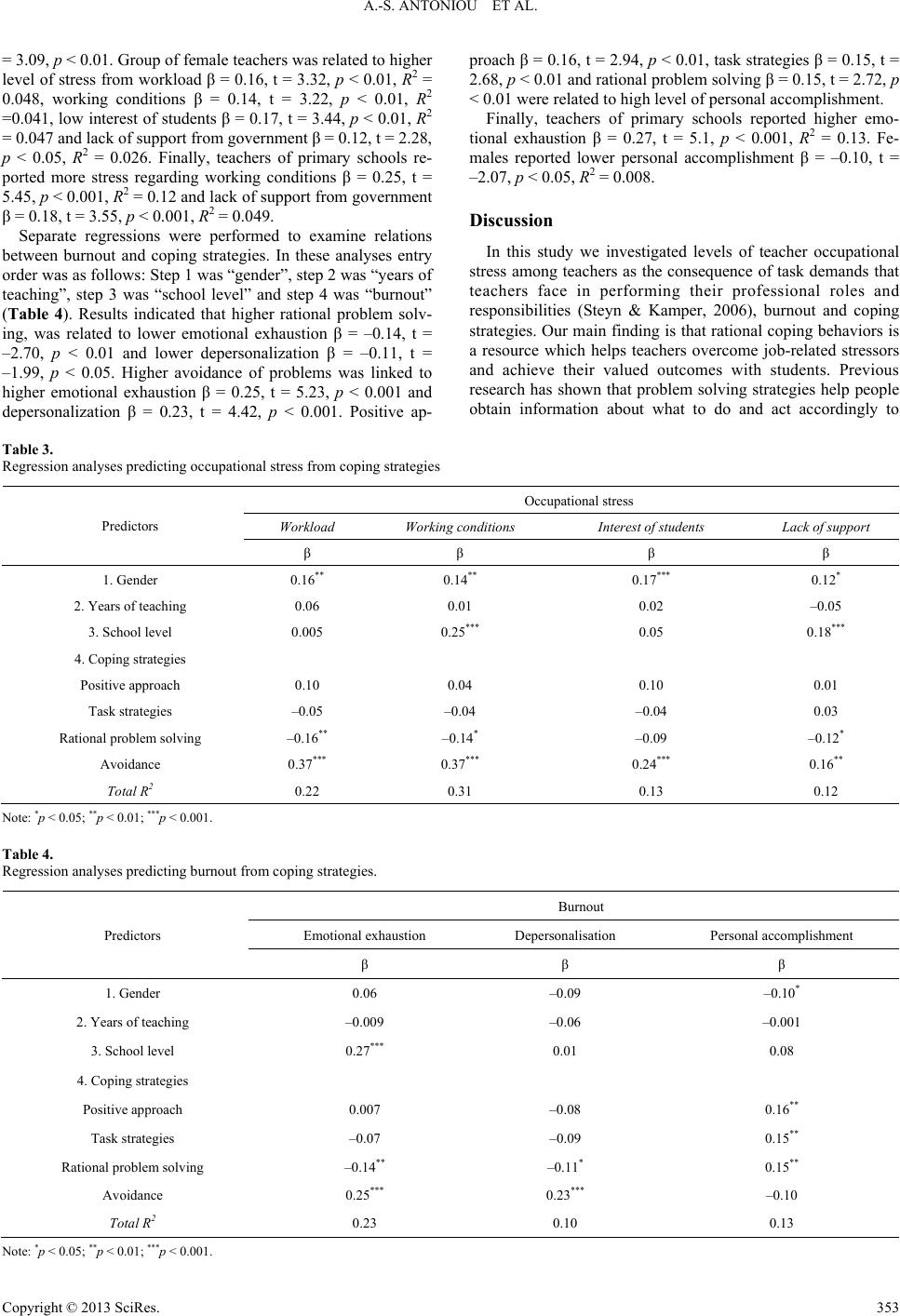

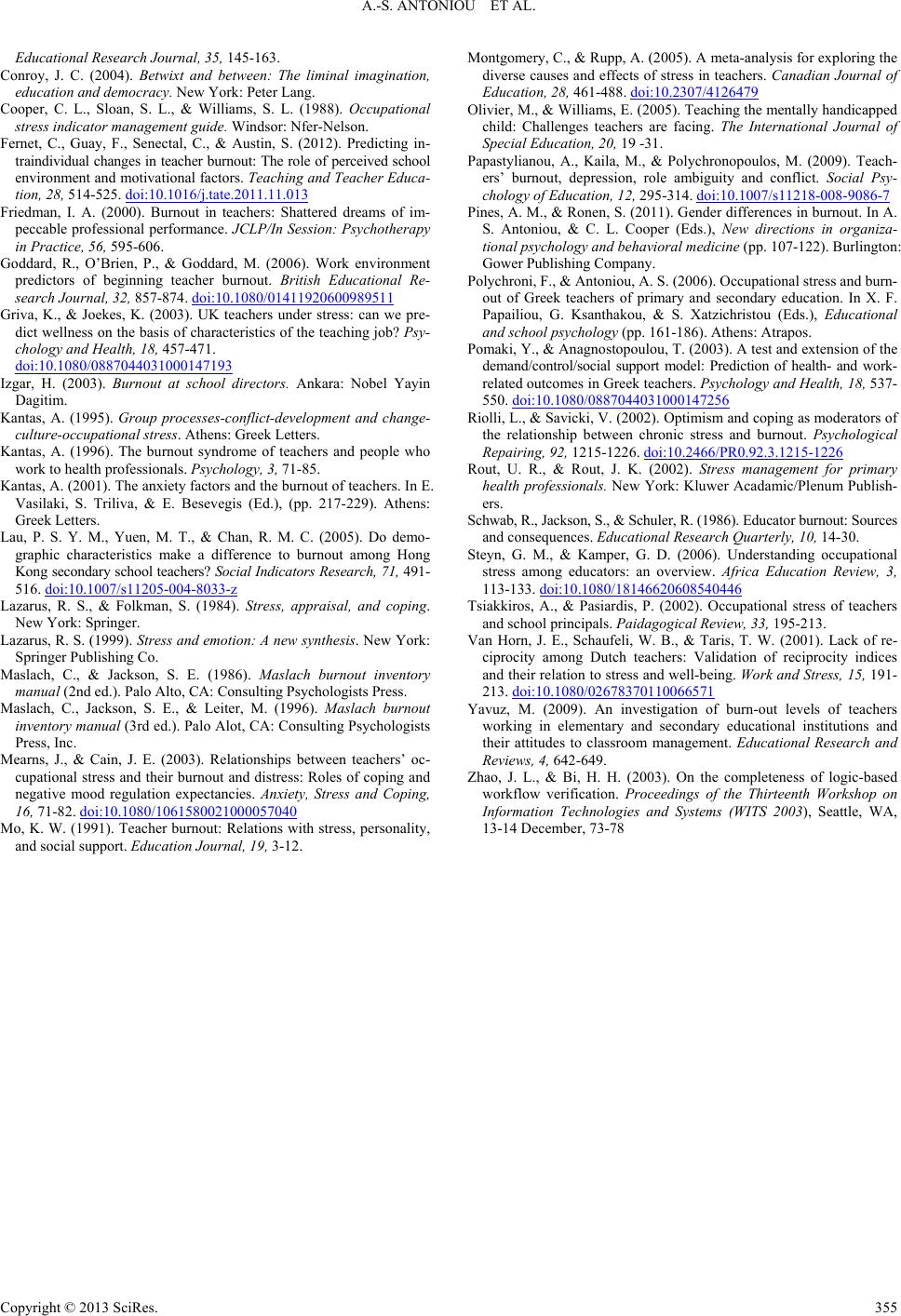

|