Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.3A, 238-245 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.43A036 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 238 Sequential Stimulus Pairing Procedure for the Students with Intellectual Disabilities Mikimasa Omori1,2*, Jun -ichi Yamamot o3 1Department of P sychology, Graduate School of Human Relations, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan 2Japan Society for the Promoti on o f S ci en c e, Tokyo, Japan 3Department of Psychology , Faculty of Letter, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan Email: *mo_carzy0219@a5.keio.jp Received December 15th, 2 0 1 2 ; revised January 16th, 2013; accepted February 14th, 2013 For most of students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and Williams syndrome (WS), a rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorder, are known to have intellectual disabilities (ID). Students with ID often show the difficulties in reading. Especially, they are difficult to acquire the equivalence relations among pictures, written letters, and sounds and to have fluent eye movement during reading. Previous research suggested that a student with autism acquired Kanji reading skills by using stimulus pairing training. However, for acquiring word reading skills, new training which facilitates the fluent eye movement is necessary and we developed sequential stimulus pairing training. In the present study, we examined the acquisition of word reading skills through sequential stimulus pairing training for three students with ID who were also diagnosed as WS and three students with ID who were not diagnosed with WS. In a trial, each letters, the word, spoken sound, and picture were presented sequentially. With 6 students, result in- dicated that they could acquire the word reading skills, and also showed the improvement of their eye movement in reading. The result suggested sequential stimulus pairing training is effective to acquire both equivalence relations and fluent eye movement for wide range of students with ID. Keywords: Sequential Stimulus Pairing Procedure; Word Reading; Student with Intellectual Disabilities Introduction Reading is complex behaviors that requires us to pronounce the letters and words accurately and fluently (Akita & Hatano, 1999), and move our eyes fluently towards the words (Rayner, 2009). The National Reading Panel (2000) in National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) introduced the five fundamental skills of the acquisition of reading skill. These are phonetic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, reading comprehension, and reading fluency. For Japanese reading, these skills are also required (Akita & Hatano, 1999). By learn- ing these skills, reading have to be taught (Shaywitz & Shay- witz, 2008). For students with intellectual disabilities (ID), they often show the reading difficulties (Allor, Mathes, Roberts, Cheatham, & Champlin, 2010; Katims, 2001). LaMalfa, Lassi, Bertelli, Salvini, and Placidi (2004) reported that 70% of per- sons with autism spectrum disorders have intellectual disabili- ties and most of individuals with Williams syndrome (WS), a rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorder, are known to have mild or moderate intellectual disabilities (Bellugi, Lichtenber- ger, Jones, Lai, & St. George, 2000). In order to acquire reading accuracy and fluency, we construct the equivalence relation among three types of stimuli, pictures, written words and spo- ken sounds (Omori, Sugasawara, & Yamamoto, 2011; Sidman, 2000; Yamamoto, 1994). However, students with ID with or without other developmental disabilities often show the diffi- culties in acquiring these equivalence relations. Previous study showed that matching-to-sample (MTS) pro- cedure is one of the most widely used procedures to facilitate acquiring reading skills and the equivalence relations (e.g. Stromer et al., 1996; Yamamoto & Shimizu, 2001). However, there are some potential difficulties for students with ID to acquire the equivalence relations by using MTS (Dube, et al., 2010; Pilgrim, Jackson, & Galizio, 2000; Serna, Dube, & Mc- Ilvane, 1997) because of their attention problems. Recent study reported that students with ID could acquire the reading skills by using Direct Instruction flashcard system (Ruwe, McLaugh- lin, Derby & Johnson, 2011) or stimulus pairing training (Ta- kahashi, Yamamoto, & Noro, 2011). In other words, it is possi- ble for students with ID to acquire reading skills by observing the visual stimuli and listening to the corresponding auditory stimuli alternatives to c l i c k i n g response. Takahashi and his colleague (2011) implemented stimulus pairing training for a student with autism to facilitate Kanji (Japanese ideogram) reading skills. In their study, a Kanji char- acter was presented on the computer at first, and then the spo- ken sound of Kanji character was immediately presented once simultaneously and other stimulus pairs followed. Through the training, the student could acquire 12 of Kanji reading and other equivalence relations. They did not use corresponding picture stimulus during the training. Other study showed that stimulus pairing procedure is even more effective to construct the equivalence relations than MTS procedure when nameable stimuli were used (Clayton & Hayes, 2004; Leader & Barnes- Holmes, 2001). And therefore, we decided to use corresponding picture stimuli. We still need to improve stimulus pairing procedure in order to facilitate the fluent and smooth eye movements toward the words. Japanese phonogram (Hiragana) usually has one-to-one *Corresponding author.  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO relationship between written letters and spoken sounds. For example, a letter “あ” is only pronounced as //a//. Reading Hi- ragana letters is not as difficult as reading phonics of English (Wydell & Butterworth, 1999). However, there are still many Japanese students struggling to read words. In Ja panese reading, students were required to move their eyes from top to bottom and right to left smoothly and fluently. For poor Japanese read- ers, when a 3-letter-word such as “かえる//kaeru//(frog)” is presented, they often don’t read a whole word but read one of three letters, such as “え//e//”. Previous research showed that poor eye movement is one of the major causes of reading diffi- culties (Shaywitz, 2003; Stein, 2003; Stein & Talcott, 1999; Rayner, 2009). Students with autism (Brenner, Turner, & Mul- ler, 2007) and WS (Braddick & Atkinson, 2011) often tend to focus on the detailed part of visual stimuli. In other words, poor readers seem to have fixed eye movement and have difficulties in moving their eyes fluently for reading. We then developed the sequential stimulus pairing procedure to fluent eye movements corresponding to letters. In this train- ing, a letter of a word was presented sequentially from top to bottom on the computer display. If we present a letter of a word in succession from top to bottom, it would be effective for stu- dents with developmental disabilities to acquire the equivalence relations and fluent eye movement for word reading skills. In this study, we examined the acquisition of equivalence re- lations between pictures, Hiragana words and spoken sounds for six students with intellectual disabilities through sequential stimulus pairing training. In the training, the pairs of Hiragana letters and spoken letters, Hiragana word and spoken word, and corresponded picture were presented automatically in succes- sion. Students were required to observe the stimulus pairs pre- sented. We required the students to read the Hiragana letters and words presented on the computer and examined whether the students could acquire the equivalence relations between Hiragana letters and words and spoken sounds. We conducted picture naming test in order to evaluate the equivalence rela- tions between Hiragana words and pictures. We also examined whether the number of training blocks needed to meet criterion varied between students with ID who were also diagnosed with WS and who were not diagnosed with WS. Method Participants Six students with intellectual disabilities participated in the present study. Three of them were diagnosed with Williams syndrome (WS), two of them were diagnosed with mental re- tardation (MR), and one of them was diagnosed with autism. Informed consent was provided to both students and their par- ents. All of them agreed to participate in the present study. For students with autism and mental retardation, their diagnosis had been provided by a doctor or clinical psychologist, individually, with the criteria of the DSM-Ⅳ-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). For students with WS, their diagnosis had been provided by a medical doctor. All students could name a lot of pictures and read some of Hiragana letters, but could not read Hiragana words. Table 1 shows the profiles of the participants. We used Kyoto Scales of Psychological Development (KSPD; Ikuzawa, Matsushita, & Nakase, 2002) to assess the students’ develop- mental quotient (DQ) because we couldn’t assess with the We- chsler Intelligence Scale for Students-Third Edition (WISC-III; Japanese edition; Wechsler, 1998) or other standardized test batteries. Their names have been changed to assumed name to protect the participants’ identities. For three students with ID and WS, MANA, GO, and AKI, their mean chronological age was 5-year-9-month-old ranging 4-year-4-month-old to 7-year- 7-month old, mean DQ in cognition and adaptation (C-A) sub- scales was 43.33 (SD ± 7.23) ranging 35 to 48, mean DQ in language and sociability (L-S) subscales was 56.00 (SD ± 10.39) ra ng i n g 4 4 t o 6 2, and mean full scale DQ was 49. 00 (SD ± 5. 20) ranging 46 to 55. Their mean verbal age measured by Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PVT-R; Ueno, Nagoshi, & Konuki, 2008) was below 3 years and 0 month old. For three students with ID and without WS, RUI, KEN, and RYO, their mean chronological age was 9 year and 3 months old ranging 6-year- 4-month-old to 10-year-3-month-old, mean C-A DQ was 45.00 (SD ± 9.85) ranging 34 to 53, mean L-S DQ was 58.00 (SD ± 7.81) ranging 53 to 67, mean full scale DQ was 51.67 (SD ± 8.50) ranging 43 to 52, and their mean verbal age was 5 years and 5 months old ranging 3-year- 6-month-old to 6-year-7- month-old. Both groups were matched with their mean full scale DQ scores with 49.00 for students with ID and WS and 51.67 for students with ID without WS. Stimulus and Ap paratus The experimental procedures for these students were con- ducted in the lab room in Keio University. A desk and a chair were used in all experimental phases. In this study, a laptop computer (Panasonic, Let’s Note CF-S8, Windows XP) was used to present stimuli. Stimulus pairs for the training phase Table 1. Profiles, DQ score, and ve rbal age of students. Name Sex Chronologic al Age (year; month) Diagnosis C-A DQL-S DQFS DQ Verbal Age (year; month) MANA Female 4; 04 Williams syndrome 35 62 46 >3; 00 GO Male 5; 03 Williams syndrome 48 44 46 >3; 00 AKI Female 7; 07 Williams syndrome 47 62 55 >3; 00 RUI Male 6; 04 Mental re tardation 53 67 60 4; 01 KEN Male 9; 00 Mental retardation 34 53 43 3; 06 RYO Male 10; 03 Autism 48 54 52 6; 07 Note: Developmental quotient (DQ) scores were measured by using Kyoto Scales of Psychological Development (KSPD; Ikuzawa, Matsushita, & Nakase, 2002). C-A = cognition and adaptation subscales, L-S = language and sociabilit y subscales and FS = full scales. Verbal age was measured by using Picture Vocabulary Test- Revised Ueno, Nagoshi, & Konuki, 2008). >3; 00 indicated that the verbal age was below 3 years and 0 month old.. All students are identified by assumed names. ( Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 239  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO were made by using Microsoft PowerPoint 2007. We prepared twelve of each 2-letter words, 3-letter words, 2-letter-con- tracted words, and 3-letter-contracted words. While 2-letter words have two letters for two sounds (e.g. “いぬ//inu//(dog)”, “い//i//” “ぬ//nu//”), 2-letter-contracted words have three letters for two sounds (e.g.”りゅ//ryu//” “う//u//”) . Like as 2-letter-contracted words, 3-letter-contracted words have four letters for three sounds (e.g.”が//ga//” “びょ//byo//” “う//u//”). We selected 12 Hiragana words that students were unable to read at the pre-assessment. Twelve pictures and spoken words corresponded to each of Hiragana words were also selected. These Hiragana words and contained Hiragana letters, spoken words, and pictures were assigned to three stimulus sets. We prepared three stimulus sets which consisted of eight or 12 Hiragana letters, four Hiragana words, spoken words and pic- tures. Number of Hiragana letters in a stimulus set varied de- pending on the 2 or 3 sounds words. Students took training from the stimulus set 1, and then set 2 and 3 in order. Procedure We conducted pre-assessment, baseline, sequential stimulus pairing and reading probe after pairing training, and follow-up for one and two weeks. Pre-assessment. First, three pictures and three Hiragana let- ters were presented on the computer one-by-one. The students were instructed to name the pictures and read letters verbally presented on the computer for pre-assessment and all students could name pictures and read letters. After that, forty eight Hiragana words were presented on the computer one-by-one. The students were instructed to read them verbally for the word reading test. The students were also required to name the forty eight pictures verbally, presented on the computer one-by-one. These pictures were corresponded to the meanings of the Hira- gana words. And then, we selected 12 Hiragana words and corresponded pictures. In addition, we prepared Hiragana let- ters that were consisted of Hiragana words. For example, when “かえる//kaeru//(frog)” was chosen as a stimulus, we also se- lected consisted letters “か//ka//,” “え//e//,” and “る//ru//” as stimuli. Twelve Hiragana words were ones that students could not read but could read some of Hiragana letters and name the corresponded picture at that time, and we prepared these as the experimental stimulus pairs. If st udents could not name at least 12 pictures, we randomly selected pictures and their corre- sponded Hiragana words in order to make three stimulus sets. Baseline. In the baseline, the students took two reading tests and one naming test. First, they were required to name the 12 pictures verbally, presented on the computer one-by-one for the picture naming test. And then, they were instructed to read 12 Hiragana words verbally, presented on the computer one- by-one for the word reading test. After that, they were in- structed read Hiragana letters consisted of each word verbally, presented on the computer one-by-one for the letter reading test. After taking a couple of blocks, they then were required to name four pictures and read Hiragana letters and four Hiragana words in a stimulus set. Only when their percentage of correct response in word reading test in a stimulus set became stable, we started sequential stimulus pairing training and otherwise, they remained taking three types of tests. Sequential stimulus pairing and reading probe after pairing. During the sequential stimulus pairing, students observed four stimulus pairs in a stimulus set. Students observed multiple stimulus pairs of Hiragana letters, spoken letters, a Hiragana word, a spoken word and a picture for four times. Each pair of stimuli was presented on the computer simultaneously, and all the stimulus pairs were presented successively. They were also required to move their eyes from top to bottom in order to fol- low the presented letters and a word, and imitate the spoken letters and a word during the training. Figure 1 shows the procedure of sequential stimulus pairing training. When the stimulus set of 3-letter-words, for example “かえる//kaeru//(frog)”, was on training, the first letter, “か”, was presented on the upper part of computer display for 2-s and also its spoken letter was presented. The second letter, “え,” was presented in the middle, the third letter, “る,” was pre- sented on the bottom and these spoken letters were also pre- sented. Finally, the word “かえる”and the spoken word were presented and the picture of “frog” followed. One trial con- sisted of the presentation of three Hiragana letters and their spoken letters for 2-s, a Hiragana word and a spoken word for 2-s, a picture for 2-s and a black screen for 1-s. Each of three stimulus pairs was presented randomly for three times making 12 trials. It took less than 3-min for students to complete train- ing block. Immediately after finishing a training block, three types of tests identical to those of the baseline phase were assessed. They are: picture naming test, word reading test, and letter reading test. Only when the students could read all four trained Hiragana words in a stimulus set for two consecutive blocks in a probe after pairing training phase, they started training for another stimulus set and repeated until they finished three stimulus sets. Otherwise, we trained the students on the same stimulus set again. Although percentages of correct responses in picture naming test and letter reading test were not 100% nor stable in reading probe after pairing phase, because our primary target was to acquire the Hiragana word reading, we didn’t conduct the further training. Follow-up phase. Follow-up tests were implemented one and two weeks after completing the sequential stimulus pairing training for a stimulus set. The students were required to take picture naming test, word reading test, and letter reading test. These tests were identical to the ones conducted in baseline and probe after pairing training. Figure 1. The procedure of sequent i a l stimulus pairing training. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 240  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO Each Hiragana letter and spoken letter and Hiragana word and spoken word were presented at the same time and then corresponded picture. Each letters is presented from top to bot- tom sequentially and successively. Experimental Design A multiple probe design across behavior (Ledford, Gast, Luscre, & Ayres, 2008) was used for the present study in or der to assess the effe cts of sequential stimulus pairing proce- dure. Dependent Variables We prepared three dependent variables in order to evaluate the emergence of equivalence relation. These were the per- centages of correct responses in word reading test, picture naming test, and letter reading test. 1) In word reading test, students were required to make same vocal responses of the Hiragana words as the corresponded spoken words presented during the training when the Hiragana word was presented on the computer; 2) In picture naming test, students were required to make same vocal responses of the picture as the corre- sponded spoken word presented during the training when the Hiragana word was presented on the computer; 3) In letter reading test, students were required to make same vocal re- sponses of the Hiragana letters as the corresponded spoken letters presented during the training when the Hiragana letter was presented on the computer. Reliability Due to the characteristics of picture naming test, letter read- ing test, and word reading test., two independent observers, including the experimenter, evaluated whether or not a correct response was made. Both listened as the students spoke and independently evaluated whether or not the response was cor- rect. The observers evaluated all trials for each participant. Trial-by-trial inter-observer agreement (IOA), calculated as the number of consistent correct responses, was used to determine interrater reliability. All of the picture naming tests, letter read- ing tests, and word reading tests in baseline, probe after pairing training, and follow-ups were evaluated and calculated. The IOA values were 100% for picture naming test, letter reading test, and word reading test in baseline, probe after pairing training, and follow-ups respectively. These values indicate satisfactory agreement. Kappa (Cohen, 1968) was calculated to measure interrater reliability for the vocal responses, and was found to be high for ratings of responses by all students scored as 1.00 respectively. Results Results of Picture Naming Test and Letter Reading Test Table 2 showed the mean percentages of correct responses in picture naming test and letter reading test for students with ID with WS and students with ID without WS. For three students with ID and WS, their mean percentages of correct responses in picture naming tests in all word sets were 50% (SD ± 0.18) in the last block of baseline, 92% (SD ± 0.18) in the training block to meet the criteria, 97% (SD ± 0.08) in the 1 week follow-up, and 75% (SD ± 0.31) in 2 week follow-up block. They also scored 61% (SD ± 0.14), 99% (SD ± 0.03), 99% (SD ± 0.03), and 94% (SD ± 0.07) respectively in letter reading tests in all word sets. For three students with ID without WS, they scored 78% (SD ± 0.15) in the last block of baseline, 100% (SD ± 0.00) in the training block to meet the criteria, 100% (SD ± 0.00) in the 1 week follow-up, and 97% (SD ± 0.08) in 2 week follow-up block in picture naming test. Their mean percentages of correct responses in letter reading tests in all word sets were 55% (SD ± 0.12), 93% (SD ± 0.11), 97% (SD ± 0.08), and 94% (SD ± 0.08) respectively in letter reading tests in all word sets. Results of Word Reading Test in Students with ID and WS Figure 2 shows the percentages of correct responses in word reading tests for students with ID and WS, the results of MANA on the top left panels, GO on the top right, and AKI on the bottom left panels. Three students took average 8.00 (SD ± 1.73) blocks to complete the three training blocks. The table on the Figure 2 was the selected stimuli for each student. In the baseline phase, MANA, on the top left panels, couldn’t read any of Hiragana words across three stimulus sets but could read some of Hiragana letters and name most of pictures. We se- lected 2-letter words as word set 1, 3-letter words as set 2, and 2-letter-contracted words as set 3 for her. She took four training blocks to meet the criteria for word set 1, two blocks for word set 2, and three blocks for word set 3. She scored 100% correct responses in all words sets at the one week follow-up phase. Her percentages of correct responses in all word sets remained 100% except set 1 (75%). She read “いす//isu// (chair)” when “りす//risu// (squirrel)” was presented. GO, on the top right panel, couldn’t read any of words but could read some of letters and name some of pictures. We se- lected 2-letter words as word set 1 and set 2, and 3-letter words as set 3 for him. He took four training blocks to meet the crite- ria for word set 1, two blocks for word set 2, and three blocks for word set 3. At the one week follow-up phase, he could read Table 2. Mean percentages of correct responses in picture naming test and letter re adi ng test for students with ID with and withou t WS. Students Test Last block of Baseline Criteria meeting block 1 week follow -up 2 weeks f ol low-up Picture na ming 50% 92% 97% 75% with WS Letter reading 61% 99% 99% 94% Picture naming 78% 100% 100% 97% without WS Lette r reading 55% 93% 97% 94% Note: Results in Criteria meeting block were the r esults of last training block i n each word sets. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 241  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO Figure 2. The results of word reading test in students with intellectual disabilities (ID) who were also diagnosed with Williams syndrome (WS). The top left panels indicated the results of MANA, top right panels indicated the results of GO, and the bottom left panels indicated the results of AKI. all trained words. In two weeks follow-up phase, his percent- ages of correct responses in all word sets remained 100% ex- cept set 1 (75%). Although he could read “し//shi//” in the 2 weeks follow-up sessions, he read “ほひ//hohi// (no meaning)” when “ほし//hoshi// (star)” was presented. AKI, on the bottom left panels, couldn’t read any of words but could read some of letters and name some of pictures. We selected 2-letter words as word set 1 and set 2, and 3-letter words as set 3 for her. She took two training blocks each to meet the criteria for all word sets. At the one and two week follow-up phase, she scored 100% correct response in all word sets. Results of Word Reading Test in Students with ID without WS Figure 3 shows the percentages of correct responses in word reading tests for students with ID who were not diagnosed with WS, the results of RUI on the top left panels, KEN on the top right, and RYO on the bottom left panels. The table on the Fig- ure 3 was the selected stimuli for each student. Three students took average 8.00 (SD ± 1.73) blocks to complete the three training blocks. In the baseline phase, all students couldn’t read any of Hiragana words across three word sets but could read some of Hiragana letters and name most of pictures. For RUI diagnose with MR, on the top left panel, we selected 3-letter Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 242  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO Figure 3. The results of word reading test in students with intellectual disabilities (ID) who were not diagnosed with WS. The top left panel indicated the results of RUI (MR), to p right panel indicated the results of KEN (MR), and the bottom left panel indicated the results of RYO (autism). words as word set 1, 2, and 3. He took three training blocks to meet the criteria for word set 1 and 2 and three blocks for word set 3. We selected 2-letter-contracted words as word set 1 and set 2, and 3-letter-contracted words as set 3 for KEN diagnosed with MR, on the top right panel. He took four training blocks to meet the criteria for word set 1 and 2 and two blocks for set 3. For RYO diagnosed autism, on the bottom left panel, we se- lected 2-letter-contracted words as word set 1 and 3-letter-con- tracted words as set 2 and 3 for him. He took three training blocks to meet the criteria for word set 1 and two blocks for set 2 and 3. For three students without WS, their percentages of correct responses in all word sets were remained 100% in one and two week follow-up phase. Discussion In this study, we examined the acquisition of equivalence re- lations among pictures, Hiragana words and spoken sounds for six students with intellectual disabilities through sequential stimulus pairing training. During the training, students were required to observe the stimulus pairs of Hiragana letters and spoken letters, Hiragana word and spoken word, and corre- sponded picture. According to Table 2, Figures 2 and 3, all students established equivalence relations between pictures, Hiragana words and spoken sounds through sequential stimulus Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 243  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO pairing training. Our results replicate the previous finding that equivalence relations (Clayton & Hayes, 2004; Leader & Bar- nes-Holmes, 2001), Kanji reading skills (Takahashi et al., 2011) and sight word reading (Ruwe et al., 2011) can be acquired by observing visual stimuli such as stimulus pairing training and flashcard training. Each student acquired t at least 12 Hiragana words reading through the training. We demonstrated that pre- senting each letter on top, middle, and bottom in order can be applied to the sequential stimulus pairing training and facili- tated the acquisition of Hiragana word reading. And we ex- tended the previous results by demonstrating that students with ID who were also diagnosed with autism, WS, and MR could acquire the multi-letters word reading skill through sequential stimulus pairing training while previous study showed a student with autism could acquire one-letter Kanji reading skill (Taka- hashi et al., 2011). We also examined whether the number of training blocks needed to meet criterion varied between students with ID who were also diagnosed with WS and who were not diagnosed with WS. Based on Figures 2 and 3, mean number of training blocks to complete the all word sets in both students with ID with and without WS was 8.00 (SD ± 1.73) blocks respectively. These results suggested that sequential stimulus pairing training was effective for students with ID even though s/he was also diag- nosed other kinds of developmental disabilities. While MTS procedure requires students to respond by clicking (e.g. Stromer et al., 1996; Yamamoto & Shimizu, 2001), sequential stimulus pairing training only required them to observe the presented visual stimuli. Without clicking responses, we can decrease the potential difficulties of acquiring equivalence relations for stu- dents with ID through MTS procedure, such as position prefer- ences and stimulus preferences. Previous studies showed that stimulus pairing training is more effective to acquire the equi- valence relations than MTS procedure when nameable stimuli were used (Clayton & Hayes, 2004; Leader & Barnes-Holmes, 2001). There are five fundamental skills of acquiring reading skills, phonetic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, reading com- prehension, and reading fluency (Akita & Hatano, 1999; NRP, 2000). Table 2 showed that our students could read about half of Hiragana letters containing in Hiragana words even at the baseline phase. They could also more than half of picture stim- uli. We still need to examine whether students with ID who could not read any of Hiragana letters containing in the words can also acquire the equivalence relations and reading skills through sequential stimulus pairing training. Although further research is necessary, letter reading skill is one of the pre re- quirement skills for acquiring Hiragana word reading and fluent eye movements like as the developmental stages of the acquisi- tion of reading skills (Akita & Hatano, 1999; NRP, 2000). Because poor eye movements is one of the major cause of reading difficulties (Stein, 2003; Stein & Talcott, 1999), our training were focusing on the not only the acquisition of equi- valence relations, but also fluent eye movement toward the words. All students could not read none of Hiragana words but some of letters at the pre assessment. For example, when these students with ID were required to read “かえる//kaeru//(frog)”, they often responded by reading only “え//e//” and others read “る//ru//” as a vocal response. According to Figure 2, MANA could acquire not only 2-letter words reading skill, but also 3-letter words and 2-letter-contracted words reading skills. AKI also extended her reading skills from 2-letter words to 3-letter words reading. While others extended their reading skills through the training, GO could only acquire 2-letter words reading skills because his L-S DQ (44) was the lowest of three. However, he did show untrained 3-letter words and 4-letter words reading skills after finishing the present study. All of students with WS could read 11 of 12 learned words even 2 weeks after the train- ings. Based on Figure 3, RUI acquired 3-letter words reading. KEN and RYO extended their reading skills from 2-letter-con- tracted words to 3-letter-contracted words. Three students with- out WS could read all of their learned words even after 2 week follow-up phase. Although students with ID often have diffi- culties in attending visual stimuli and moving their eyes flu- ently (Braddick & Atkinson, 2011; Brenner et al., 2007), they acquired at least 2-letter words reading by using sequential sti- mulus pairing procedure. MANA, KEN, and RYO even acquired contracted word reading. A contracted letter is made of one big letter and one small letter. Reading contracted word is sometimes difficult for typically-developing students because contracted letters can be discriminated only by the size of second letter. For example, MANA read “しやつ//shiyatsu//” when “しゃつ //shiatsu//(shirt)” was presented on the computer at the last block of baseline phase in word set 3. Although she had already learned how to read 3-letter words through our training, it was still hard for her to read contracted-letters and words. In order to facilitate the contracted word reading, we surrounded each normal and contracted-letters by black framed white rectangle (see Figure 1). By boxing off the each word, visual cue helped students to read a letter or a contracted-letter in a box for one sound letter. The theoretical implication of our study was that we showed the establishment of reading skills by contiguities, as well as by contingencies, normally focused using MTS procedure. During the developmental process, we suppose students learn language and literacy through contiguity in naturalistic and educational situations. Furthermore, as for an applied implication, our study with sequential stimulus pairing procedure demonstrated the efficient and effective, learning method to students: we required neither choice response nor differential responding for students’ tasks. By using our procedure, students with ID who also diag- nosed with genetic disorder, such as Williams syndrome, or developmental disabilities, such as autism could acquire the reading skills. It suggests that we can apply the sequential stimulus pairing procedure for wide range of students with ID who have some repertoires to read letters and name pictures in order to facilitate their reading skills. Future studies need to examine effective observing responses for getting students’ attention and maintain their stimulus pairing tasks. Ruwe and her colleague (2011) reported that flashcard system could fa- cilitate not only word acquisition, but also passage reading. In sequential stimulus pairing procedure, we presented each letter of the word one-by-one to extend students’ reading skills. And then we can apply the sequential stimulus pairing procedure to sentence or passage reading and comprehension by presenting each word or segment of the sentences one-by-one sequentially. In order to firm the “logical structure” of reading skills from letter reading to reading comprehension in this paradigm, we also need to clarify what prerequisites and pre-skills are neces- sary for learning. Acknowledgements This work has been supported by Global Center of Excel- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 244  M. OMORI, J. YAMAMOTO Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 245 lence (GCOE) program and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). This work was permitted by Keio University Institutional Review Board (IRB) in Faculty of Letter. REFERENCES Akita, K., & Hatano, G. (1999). Learning to read and write in Japanese. In Harris, M., & Hatano, G. (Eds.), Learning to read and write: A cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 214-234), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Allor, J. H., Mathes, P. G., Ro berts, J. K., Jones, F. G. , & Champlin, T. (2010). Teaching students with moderate intellectual disabilities to read: An experimental examination of a comprehensive reading in- tervention. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45, 3-22. http://www.daddcec.org/Portals/0/CEC/Autism_Disabilities/Researc h/Publications/Education_Training_Development_Disabilities/Full_J ournals/ETDD201003V45n1.pdf#page=6 Allor, J. H., Mathes , P. G., Rob erts, J . K., Cheath am, J., & Ch amplin, T. (2010). Comprehensive reading instruction for students with intel- lectual disabilities: Findings from the first three years of a longitude- nal study. Psychology in the Schools, 47, 445-466. doi:10.1002/pits.20482 American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington DC: Author. Bellugi, U., Lichtenberger, L., Jones, W., Lai, Z., & St. George, M. (2000). The neurocognitive profile of Williams syndrome: A com- plex pattern of strengths and weaknesses. Journal of Cognitive Neu- roscience, 12, 7-29. doi:10.1162/089892900561959 Braddick, O., & Atkinson, J. (2011). Development of human visual function. Vision Re search, 51, 1588-1600. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2011.02.018 Brenner, L. A., Turner, K. C., & Muller, R. (2007). Eye movement and visual search: Are there elementary abnormalities in autism? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disor ders, 37, 1289-1309. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0277-9 Cla yton, M., & Hayes, L. (2004). A comparison of match-to-sample and respondent-type training of equivalence classes. The Psychological Record, 54, 579-602. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/tpr/vol54/iss4/6/ Cohen, J. (1968). Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with pro- visions for scale disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulle- tin, 70, 313-320. doi:10.1037/h0026256 Dube, W. V., Dickson, C. A., Balsamo, L. M., O’Donnel, K., L., Toma- nari, G. Y., Farren, K. M., Wheeler, E. E., & McIlvane, W. J. (2010). Observing behavior and atypically restricted stimulus control. Jour- nal of the Experimental Analysis of Beh avi or, 94, 297-313. doi:10.1901/jeab.2010.94-297 Ikuzawa, M., Matsushita, Y., & Nakase, A. (2002). Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development 2001. Kyoto: Kyoto International Social Welfare Exchange Centre. LaMalfa, G., Lassi, G., Bertelli, M., Salvini, R., & Placidi, G. F. (2004). Autism and intellectual disability: A study of prevalence on a sample of the Italian population. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48, 262-267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00567.x Leader, G., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2001). Matching-to-sample and re- spondent-type training as methods for producing equivalence rela- tions: Isolating the critical variable. The Psychological Record, 51, 429-444. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/tpr/ v ol51/iss3/5/ Ledford, J. R., Gast, D. L., Luscre, D., & Ayres, K. M. (2008). Obser- vational and incidental learning by students with autism during small group instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 86-103. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0363-7 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000). Teaching students to read: An evidence-based assessment of the sci- entific literature on reading and its implications for reading instruc- tion. Washington DC: US Gover nment Printing Office. http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/upload/report.pdf Omori, M., Sugasawara, H., & Yamamoto, J. (2011). Acquisition and transfer of English as a second language through the constructional response matching-to-sample procedure for students with develop- mental disabili ties. Psychology, 2, 552- 559. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.26085 Pilgrim, C., Jackson, J., & Galizio, M. (2000). Acquisition of arbitrary conditional discriminations by young normally developing students. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 73, 177-193. doi:10.1901/jeab.2000.73-177 Rayner, K. (2009). Eye movements and attention in reading, scene per- ception, and visual search. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 1457-1506. doi:10.1080/17470210902816461 Ruwe, K., McLaughlin, T. F., Derby, K. M., & Johnson, J. (2011). The multiple effects of direct instruction flashcards on sight word acqui- sition, passage reading, and errors for three middle school students with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23, 241-255. doi:10.1007/s10882-010-9220-2 Shaywitz, S. E. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz, B. A. (2008) Paying attention to reading: The neurobiology of reading and dyslexia. Development and Psy- chopathology, 20, 1329-1349. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000631 Sidman, M. (2000). Equivalence relations and the reinforcement con- tingency. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 74, 127- 146. doi:10.1901/jeab.2000.74-127 Serna, R. W., Dube, W. V., & McIlvane, W. J. (1997). Assessing same/ different judgments in individuals with severe intellectual disabilities: A status report. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 18, 343-368. doi:10.1016/S0891-4222(97)00015-2 Stein. J. (2003). Visual motion sensitivity and reading. Neuropsycholo- gia, 41, 1785-1793. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(03)00179-9 Stein, J., & Talcott, J. (1999). Impaired neuronal timing in develop- mental dyslexia: The magnocellular hypothesis. D ys lex ia, 5, 59-77. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(199906)5:2<59::AID-DYS134>3.0.C O;2-F Stromer, R., Mackay, H. A., Howell, S. R., McVa y, A. A., & Flusser, D. (1996). Teaching computer-based spelling to individuals with devel- opmental and hearing disabilities: Transfer of stimulus control to writing tasks. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 25-42. doi:10.1901/jaba.1996.29-25 Takahashi, K., Yamamoto, J., & Noro, F. (2011). Stimulus pairing training in students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Au- tism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 547-553. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.021 Ueno, K., Nagoshi, N., & Konuki, S. (2008). Picture vocabulary test- revised manual. Tokyo : Nihon Bunka Kagakusha. Wechsler, D. (1998). Wechsler intelligence scales for students (3rd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psycholo gic al Corporation. Wydell, T. N., & Butterworth, B. L. (1 9 9 9 ). A case study o f a n English- Japanese bilingual with monolingual dyslexia. Cognition, 70, 273- 305. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00016-5 Yamamoto, J. (1994). Functional analysis of verbal behavior in handi- capped students. In S. C. Hayes, L. J. Hayes, M. Sato, & K. Ono (Eds.), Behavior analysis of language and cognition (pp. 107-122). Reno, NV: Context Press. Yamamoto, J., & Shimizu, H. (2001). Acquisition and expansion of Kanji vocabulary through computer-based teaching in a student with mental retardation: Analysis by equivalence relations. Japanese Jour- nal of Special Education, 38, 17-31. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/els/110006785555.pdf?id=ART0008730845&type= pdf&lang=jp&host=cinii&order_no=&ppv_type=0&lang_sw=&no= 1328584307&cp=

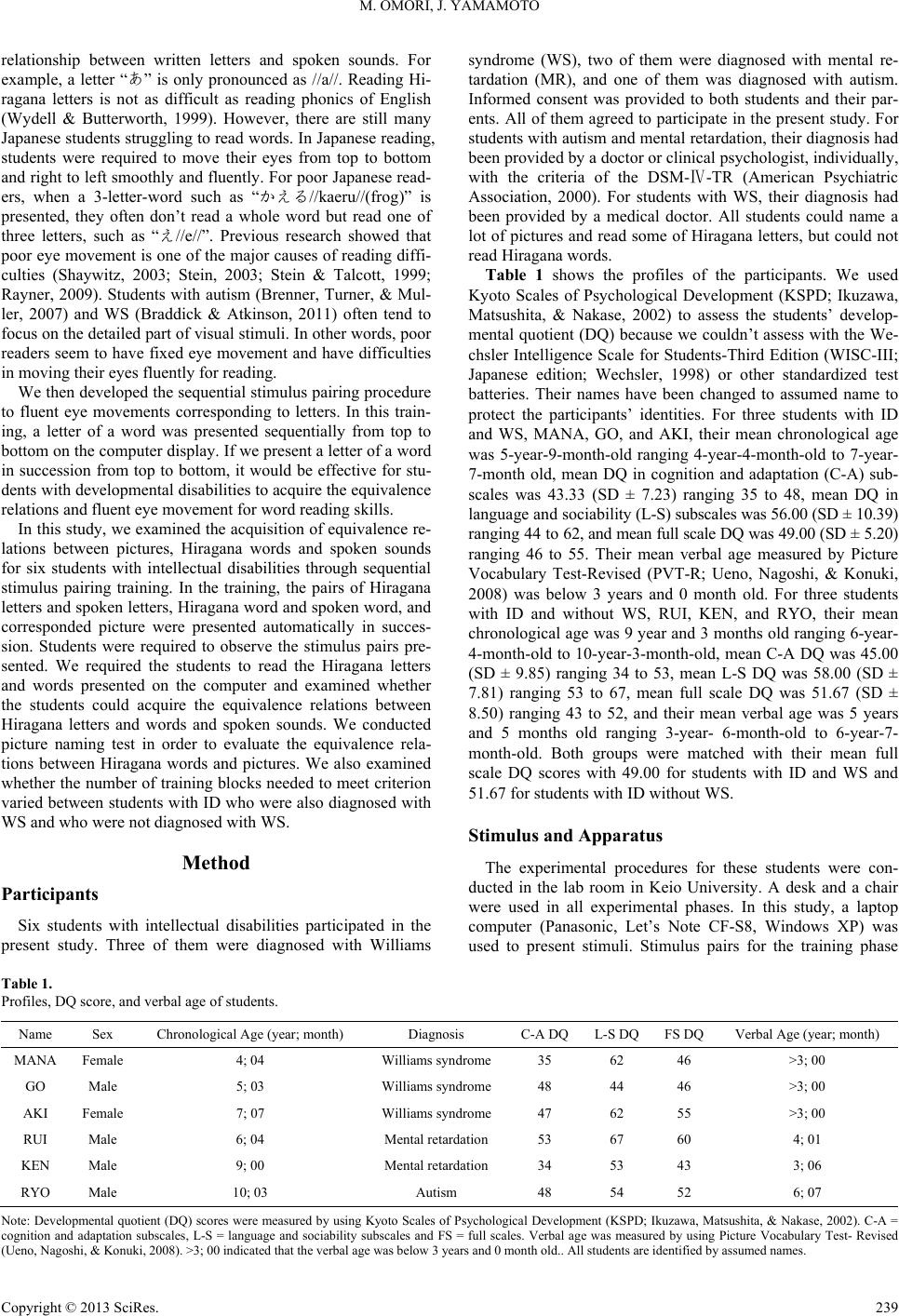

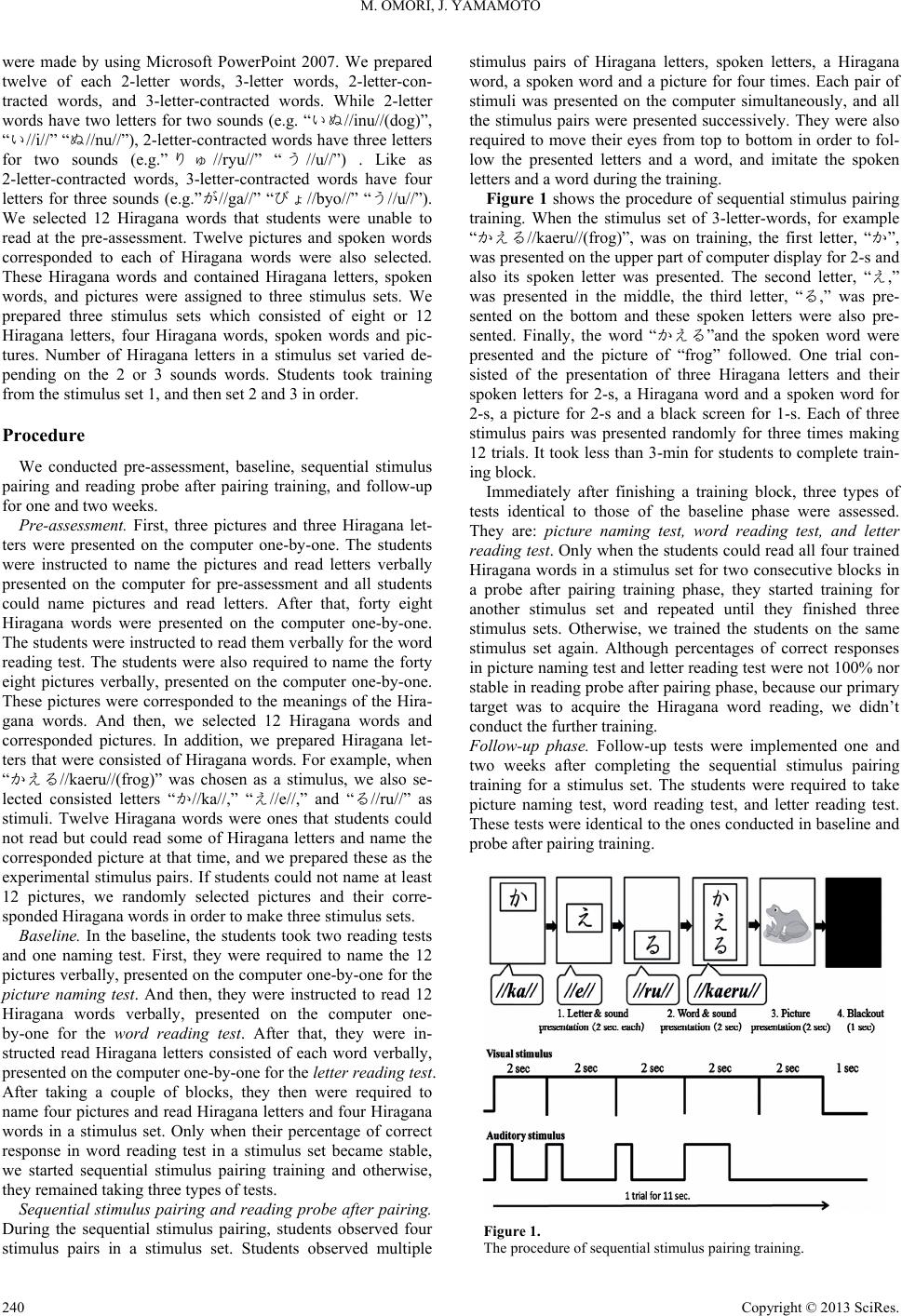

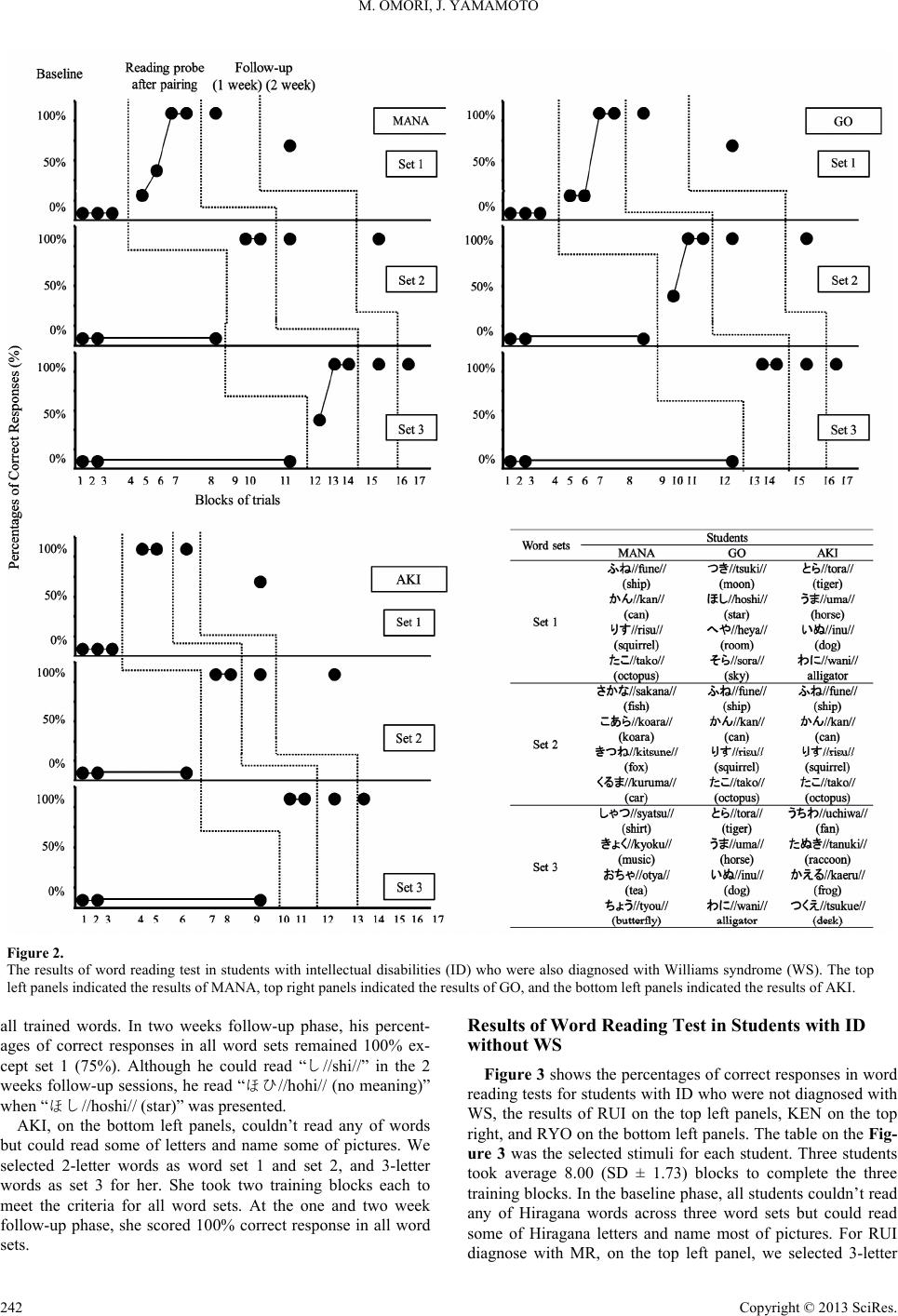

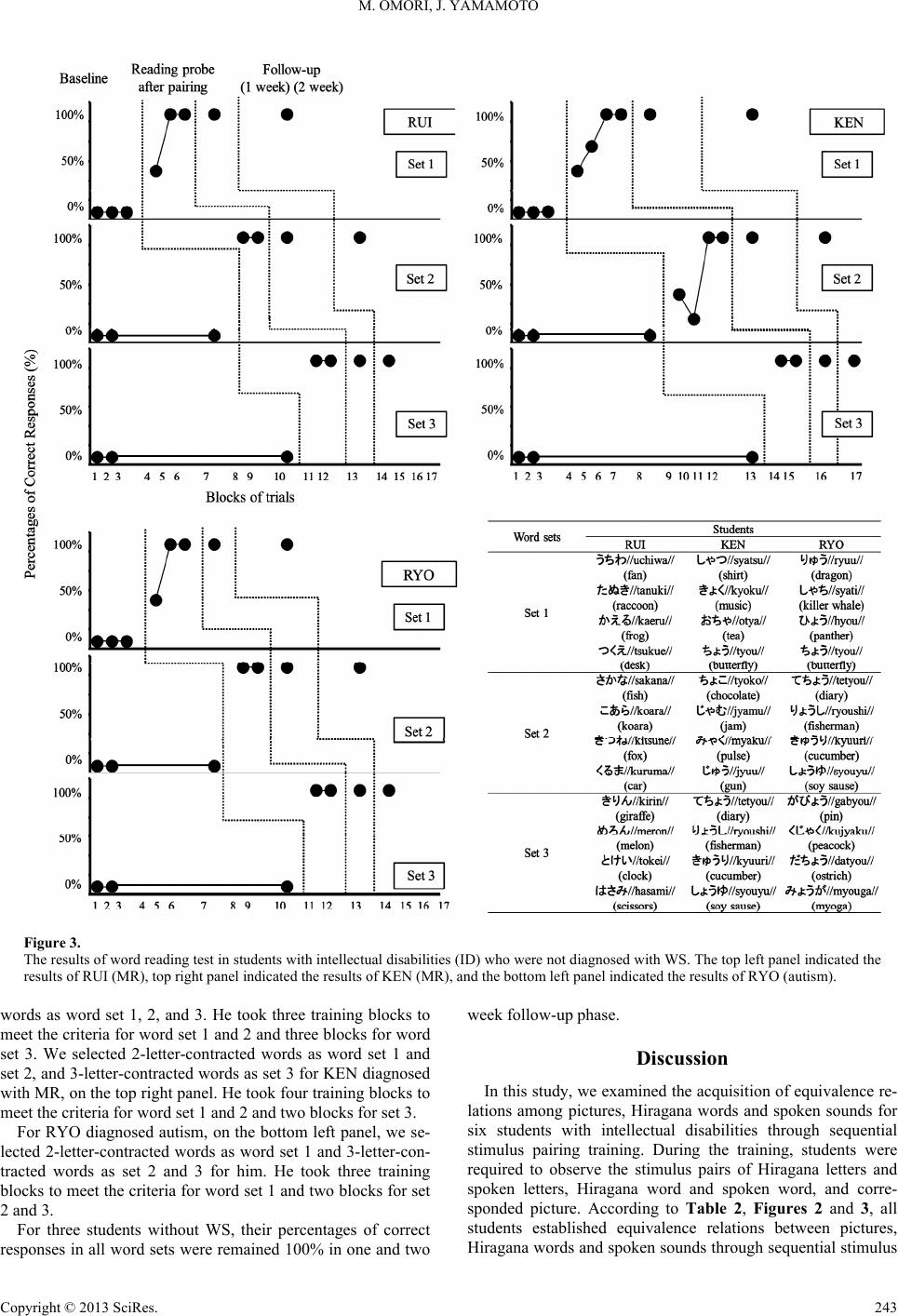

|