Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.3A, 197-204 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.43A030 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 197 The Effects of a 12-Month, Small Changes Group Intervention on Weight Loss and Menopausal Symptoms in Overweight Women Suzanne R. Daiss, Heidi A. Wayment, Sabrina Blackledge Department of Psychology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, USA Email: Suzanne.Daiss@nau.edu Received December 21st, 2012; revised January 20th, 2013; accepted February 16th, 2013 To better understand how psychological principles related to goal-setting and motivation can be applied to the problem of obesity and menopausal symptoms, we examined the effectiveness of a Small Changes In- tervention (SCI) program on forty-five overweight (BMI = 33.67 ± 7.03) women (mean age = 50.14 ± 12.16). Grounded in task motivation theory (cf. Locke & Latham, 2002), our SCI group therapy approach instituted small and maintainable steps in nutrition and physical activity to promote weight loss and a re- duction in menopausal symptoms. Body weight, Body Mass Index (BMI), and scores on the Greene Cli- macteric Scale were assessed at Baseline (pre-intervention), 3-month post-treatment, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up. By the end of the 12-month study, 20 women were still participating and had lost, on average, 6.4% of their body weight, and had experienced a significant reduction in BMI, (BMI = 30.9 ± 6.13), providing further support for the SCI approach as an effective weight loss intervention method. Cross-sectional correlational analyses found expected associations between obesity and meno- pausal symptoms at the follow-up assessments. These relationships were especially strong by the last as- sessment period. Most importantly, menopausal symptoms decreased over the duration of the intervention. Taken together, these results suggest that the longitudinal impact of SCI on weight and BMI can have a positive impact on menopausal symptoms. These findings underscore the importance of applying well- researched social psychological principles in goal setting to the problem of obesity and menopausal symptoms. Furthermore, the results obtained from the SCI approach suggest that that while obese indi- viduals may experience increased symptoms of menopause, the process of losing excess body weight through achievement of small, achievable goals has the potential to improve menopausal symptoms. Keywords: Goal Setting in Weight Loss; Task Motivation Theory; Menopausal Symptoms; Small Changes Intervention The Problem of Obesity Obesity is medically defined by the World Health Organiza- tion as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health, or more quantitatively, as the presence of a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 30 (kilograms in body weight di- vided by height in meters squared). Obesity is one of the lead- ing causes of preventable death world-wide (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). In 2008, 35% of adults world- wide over age 20 were considered overweight (BMI > 25) and 11% were considered obese (BMI > 30)). Since 1980 world- wide obesity has nearly doubled. Childhood obesity is also a serious problem with more than 40 million children age 5 and under being categorized as overweight in 2011 (World Health Organization, 2013). Unfortunately, obesity has had a negative impact on mental health and well-being. Puhl and Brownell (2003) review the stigma of obesity and summarize the research which shows that overweight individuals are viewed as having negative charac- teristics such as laziness and poor self-discipline and that they are often viewed as unattractive, and less competent and moral. It is no wonder that the psychological effects of obesity include emotional suffering and increased risk of depression (Paxman, Hall, Harden, O’Keeffee, & Simper, 2011). This effect is espe- cially strong for women and the severely obese, who are often subject to lower self esteem and poorer health-related quality of life (Fabricatore & Wadden, 2006). Behavioral modification of diet and exercise continue to re- main the most used method of weight loss. Given the negative impact of obesity on physical and psychological health as well as research demonstrating that even small reductions in weight can be beneficial (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 1998), it is surprising how ineffective most weight loss reduc- tion programs are in keeping weight off long term. Although there is much controversy in the field, a recent study of several different popular diets found no significant differences in their effectiveness (Strychar, 2006). We argue that the ability of cognitive-behavior programs to deliver long-term weight loss success may be improved by con- sideration of psychological principles related to goal-setting and motivation. In fact, research from the National Weight Control Registry (www.nwcr.ws) has recently argued that long- term weight loss is not attainable by implementing a set of es- sentially unrealistic and unsustainable goals to reduce obesity including a temporary period of strict exercise and/or diet. Rather, they conclude that long-term weight loss should be a function of change in overall lifestyle. The psychological lit- erature on goal setting and task motivation provides key in- sights into factors that can help individuals make the kind of overall lifestyle changes required for long-term weight loss.  S. R. DAISS ET AL. Applied Goal Setting and Be havior Chan ge S trategies Applying the literature on goal setting and task motivation to the problem of obesity strongly suggests that diet and exercise interventions that allow individuals to set effective goals will be more successful in promoting healthy behavior (see Locke & Latham, 2002, for review). Goal importance can be positively influenced by public commitment, having professionally guided rationale, enthusiasm, and support, and having individuals set their own goals. Other important factors for successful goal setting and attainment is a supportive group setting, receiving goal-relevant feedback, having less complex goals (Wood, Mento, & Locke, 1987), and a focus on “do-your-best” goals in the context of long-term goals (Latham & Seijts, 1999). Lutes and colleagues have applied these strategies for effec- tive goal setting into a systematic intervention they call a “Small Changes” approach to diet and exercise. A recent series of studies has found that a focus on the implementation of small, gradual changes in eating and physical activity, instead of life- style “overhauls” used by most dietary plans, have been shown to be successful in both initial weight loss, but more impor- tantly, keeping weight off (approximately 5% to 6% body weight over 6 to 9 months), even though the initial process of weight loss may take longer (Damschroder, Lutes, Goodrich, Gillon, & Lowery, 2010; Lutes, Daiss, Barger, Read, & Winett, 2012; Lutes, Daiss, Errickson, Barger, & Winett, 2012; Lutes et al., 2008). Thus, the SCI approach is an example of the effec- tiveness of applying psychological principles to the specific health problem of obesity. Obesity and Menopausal Symptoms The majority of female participants who completed earlier small change weight loss interventions led by the first author were either perimenopausal or menopausal (mean age in this study was 50.14 years). Common questions among past par- ticipants related to the relationship between weight and the physical and psychological impact of menopause. Based on the newfound success of the SCI approach with obesity, we sought to explore the efficacy of using the same program to reduce menopausal symptoms in a similar overweight and obese fe- male sample. Thus, the current study was designed as a natural progression from evaluating the effectiveness of the SCI pro- gram to evaluating how menopausal symptoms respond to this same weight loss program. Menopause is the permanent cessation of menstruation and resulting infertility as the ovaries gradually decrease production of estrogen and progesterone. Menopause may occur as early as 35 or as late as a woman’s sixties, but the average age in the US is 51 years of age. Psychological and physiological symptoms are well known in Western cultures and include symptoms such as hot flushes or flashes, mood swings, depression, anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, vaginal dryness, frequent urination, thinning skin around the vaginal walls leading to discomfort during sex- ual intercourse, and memory problems. Although menopause is a natural event in women’s lives, there are also known health threats associated with the reduc- tion of estrogen and progesterone. The relationship among obe- sity, metabolic syndrome, and depression/ anxiety is already well established, especially among women (Carpenter, Hasin, Allison, & Faith, 2000.) However, very little is known about how obesity affects one of the most important aspects of women’s health as they age: menopause. Of the many menopausal symptoms reported by Western women, hot flushes or flashes are the most frequently reported symptom in U.S. women. Up to one third of women continue to experience hot flushes up to five years past the actual cessation of menstruation (Sterns et al., 2002). Accordingly, nearly all research in the last decade examining the relationship between obesity and the frequency and intensity of menopausal symp- toms has been in the context of the severity and frequency of hot flushes (e.g., Freeman et al., 2001; Gallicchino et al., 2005; Gold et al., 2000; Gold et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2012; Schil- ling et al., 2007; Whiteman et al., 2003). For example, in a case-controlled study matching menopausal women who did not report hot flushes to women who reported hot flushes (Gal- licchino et al., 2005), BMI was positively associated with hot flushes. It was hypothesized that decreased estrogen levels from excess adipose stores is the mechanism by which this relation- ship occurs. Gallicchino et al. (2005) found that very obese women have significantly higher odds of having hot flushes and experience them more often, although the estrogen level hy- pothesis explaining this relationship was only partly supported. Schilling et al. (2007) found that Estradiol, Estrone, Progester- one, and Hormone Binding Globulin (SHGB) levels were sig- nificantly lower in obese (as compared to normal weight) wo- men, while testosterone levels were found to be higher in obese women. They also found that the association between obesity and hot flushes was no longer significant after controlling for the effects of estrogens, progesterone, and SHGB. Williams, Levine, Kalilani, Lewis, and Clark (2009) studied a large sample of American postmenopausal women, and found that the presence of menopausal symptoms had a significant impact on daily activity and led to a decreased score in quality of life. Factors such as BMI, weekly exercise, and tobacco use were found to significantly impact the quality of life. It may be that menopausal symptoms, especially hot flushes and fatigue, tend to make physical activity and other health behaviors more difficult, leading to a cyclic pattern of weight gain and in- creased menopausal symptomatology. Indeed, severity of hot flushes has also been linked to sedentariness (Chendraui et al., 2010), a state of health closely connected to BMI and obesity. A more recent study (Huang et al., 2010) examined the oc- currence and improvement of hot flushes in a group of obese, incontinent women who were participating in a clinical trial evaluating a 6-month lifestyle weight loss intervention against a health education program. Approximately half in each group reported that they were at least slightly bothered by hot flushes at baseline. For these women, the lifestyle weight loss interven- tion was correlated with higher changes in weight and BMI over 6 months as compared to the control education group. Thus, hot flushes improved over the course of the study for these participants. The authors also state that these participants’ self-reported physical activity was not associated with either increase or decrease in hot flushes, indicating that exercise was not likely the cause of the change in symptoms. In addition, calorie intake, blood pressure, and general mental and physical functioning were not associated with improved flushing. Huang et al. (2010) concluded that overweight or obese women may experience a reduction in hot flushes with behavioral weight loss programs and may benefit from enrolling in such interven- tions. They also suggest further research in both biological and psychological factors in weight loss that might affect hot flushes. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 198  S. R. DAISS ET AL. In terms of psychological factors, there seems to be an over- lap between reduced health-related quality of life in obesity and menopause. Laferrére et al. (2000) state that past studies show a decrease in health-related quality of life after menopause. De- pression and anxiety/irritability are also commonly reported as symptoms of menopause. Little research, however, actually addresses the psychological relationship between obesity and menopause. Laferrére et al. (2000) examined psychological well-being, health-related quality of life, race, and menopausal status in obese women. Participants reported being primarily middle class professional women. The investigators assessed psychological distress, including anxiety and depression, as well as satisfaction with life and self-esteem. No significant differences were found between African American and white women on these factors. However, there was a remarkable dif- ference between premenopausal and postmenopausal women, with premenopausal women reporting more life distress and less vitality than the postmenopausal women, especially in the African American group. These data are in conflict with the findings that health-related quality of life often decreases after menopause. In this sample, obese participants ranked slightly higher on anxiety and depression scores than a non-obese con- trol group, yet lower than published psychiatric norms. Life satisfaction scores fell in the same range as a normative popula- tion. It is clear that additional research is needed to clarify the impact of psychological factors in menopausal, obese women. Indeed, the physiological and psychological impact that menopause can have on women’s well-being cannot be under- estimated. It is important that we develop long-term, sustain- able psychological interventions to ameliorate symptoms ex- perienced by some during perimenopause and menopause. Study Goal s a n d H ypotheses Following evidence that the SCI approach is effective in re- ducing body weight and BMI, we sought to explore whether adult women enrolled in a small changes weight loss interven- tion program would also show a reduction in menopausal symptoms. Although it is well established that obesity can im- pact the frequency and severity of hot flushes, little is known about the impact of obesity on the full range of menopausal symptoms, not only hot flushes. Furthermore, most studies are cross-sectional in nature. Only one study to date (Huang et al., 2010) has investigated the impact of obesity on hot flushes longitudinally. Thus, for this current study, we examined the longitudinal impact of SCI weight loss program on the variety of known menopausal symptoms. We formulated three hy- potheses for the study: a) overweight and obese women would lose approximately 5% of their body weight, as this has been shown in previous small changes studies; b) overweight and obese women would show improvement in the full range of menopausal symptoms as assessed by the Green Climacteric Scale (Greene, 1998) at the end of the 12 months; and c) weight loss among overweight and obese women who completed the SCI program would be associated with lower menopausal sym- ptoms at the 12 month follow-up assessment. Method Participants The baseline sample consisted of forty-five women, age 30 and above, with a BMI of >25 (overweight or obese). They responded to newspaper advertisements posted in the commu- nity, and email advertisements posted on campus in a midsize southwestern university. Participants called the telephone number provided and were screened for the BMI requirements. If participants were unsure of their BMI, they were invited to the clinic to be weighed and measured so that BMI and eligibil- ity could be determined. If participants met BMI criteria (>25), they completed a brief screening questionnaire regarding medi- cal and psychiatric conditions and medications. Participants who reported severe depression or current anorexia or bulimia were excluded from the study, as these conditions would inter- fere with their ability to participate in the small changes weight management program. In addition, those diagnosed with any other serious medical conditions were asked to obtain a medical release from their physician to show that their condition was currently under control, otherwise they were excluded from the study. BMI was calculated at the first assessment period to validate that participants were still eligible to participate. At the first assessment meeting, participants signed both a clinic and Internal Review Board consent form. By the end of the 12- month time period, 20 participants had completed the study. Measures and Materials Demographics Demographics, including age, marital status, education, fam- ily income, and race, were assessed online via Survey Mon- key™. Height and Weight Height was measured without shoes with a height rod on a spring scale to the nearest 0.05 cm. Body weight was also as- sessed without shoes via Health-o-Meter Body Fat and Hydra- tion Monitoring electronic scales (Sunbeam Products, Boca Raton, FL, USA) to the nearest 0.1 pounds, and was then con- verted to kilograms. Each weight loss group had its own body weight scale. For height and weight, two measurements were taken and the average was used as the final score. Body mass index was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. Weight loss and percent weight change (baseline minus follow-up weight divided by baseline weight × 100) were both calculated. The Greene Climacte ri c Scale (GCS) This brief menopausal questionnaire (GCS; Greene, 1998) is a well-known, widely used, valid instrument that provides as- sessment for a diverse range of symptoms including vasomotor (i.e., hot flushes, sweating at night), somatic (e.g., headaches, muscle and joint pains), and psychological (e.g., feeling tense or nervous, feeling unhappy or depressed). On the GCS, par- ticipants were instructed to “please indicate the extent to which you were bothered at the moment by any of these symptoms by placing a tick in the appropriate box” (Green, 1998: p. 84). All items including those above were answered on a Likert scale, from: Not at all = 0, A little = 1, Quite a bit = 2, and Extremely = 3. Total scores ranged from 0 (no symptoms) to 63 (severe symptoms). Confirmatory factor analysis has demonstrated the construct validity of the GCS and items were found to have good homogeneity in measuring the scale concepts (Cronbach’s alpha > .70). Test-retest reliability for the GCS was also ade- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 199  S. R. DAISS ET AL. quate (Pearson’s r = .58, effect size = .59; N = 19; Chen, Davis, Wong, & Lam, 2010). The GCS has also been standardized on both clinical and normative population samples, and has been shown to have both content and construct validity (Greene, 1998). The GCS was also highly reliable in our sample (α = .92). The Stop Light Diet and Daily Food Logs The Stop Light Diet (Epstein & Squires, 1988) is an effective system of food categorization for weight loss originally devel- oped for children and their families (Epstein et al., 2007), but has also been shown to be successful for adults in making die- tary decisions (Borgmeier & Westenhoefer, 2009) across a con- siderably diverse population (Gorton, Mhurchu, Chen, & Dixon, 2009). Based on calorie count and fat content, food is divided up into three simple colors: green, yellow, and red. Green foods, the majority of which are fruits and vegetables, are high in nu- tritional value and low in calories and should be eaten often with no limit on quantities. Yellow foods make up the staple of a typical diet and are slightly higher calorie; they are to be eaten in moderation. Red foods tend to be very high in calories, fat, sugar, and commercial processing, and should be reduced throughout the diet’s progression. However, no food is specifi- cally forbidden, and although red foods should be minimized, they are still allowed. Stop Light Diet manuals were given to participants to code their food for their daily food logs. Food logs included space for all foods and drinks consumed each day, their stop light color, and calorie counts. Weekly Goal Sheets Weekly goal sheets detailed ideal average daily calorie intake as well as average daily number of red and green foods, which the participants tailored to their own needs and comfort level. After a baseline for daily average calories and amount of red, yellow and green foods was established during the first week, participants chose to decrease daily calories by up to, but no more than, 200 calories per day. Most participants stayed at 1500 calories or greater, and they were asked not to drop their daily calories below 1200 at any point. Design and Procedur e Five groups of 8 to 10 women were semi-randomly assigned by forming selection groups with approximately the same BMI range and randomly distributed from each selection group. This helped to ensure a diverse range of BMIs across each group. A fee of $50 was charged for the year-long program and covered the costs of basic materials. From the Baseline assessment to the 3-month post-treatment assessment, the five groups met for ten weeks over a three-month period. From post-treatment through the end of the study, groups continued to meet bi-weekly, then every three weeks, then monthly until the end of the 12 month study. There were four assessments periods: Baseline (before the start of the weight loss group), 3-month post-treatment (the end of the initial 3 months of the program), 6-Month Follow-up (six months after Baseline) and 12-month follow-up (12 months after baseline). Dependent variables included Body Weight (Kg), BMI, and the Greene Climacteric Scores. One and one half hour group sessions were led by Health Psychology graduate students and supervised by the first author, a licensed clinical psychologist. The overriding theme of the program included a “non-dieting” approach with participants making their own choices about the small changes they would make in eating and physical activity over time. Each session covered a specific topic related to weight loss. The format al- lowed for educational and group discussion. In addition, cogni- tive-behavioral techniques were used by the lifestyle coaches to promote weight loss and healthy lifestyles. Active problem solving and implementing coping strategies was also discussed during sessions. Examples of topics covered included: general nutrition, physical activity, body image, mindful eating, social support, stress reduction, and negative thought patterns. Spe- cific interventions for menopausal symptoms were not part of the intervention materials, though participants could have ap- plied the general stress management strategies they learned to reduce such symptoms. Weekly goals for daily calorie con- sumption and red and green food counts were set at the end of each session. Weigh-ins were conducted every two weeks to track weight loss progression from the Baseline to post-treat- ment times and at every session in the Follow-up period. After the 3-month post-treatment assessment (at 3 months), partici- pants were asked to continue monitoring three days a week. Though monitoring was generally less stringent during the fol- low-up period, participants continued to report their general progress at the follow-up group sessions. Statistical Analyses Given the small sample size, two decisions were made with respect to how to judge the statistical results. First, an a priori decision was made to allow for a p < .10 cutoff (one-tailed) to determine statistical significance for all hypothesized relation- ships. For all preliminary analyses a p < .05 cutoff was utilized. Second, Cohen’s (1988) conventions were used to interpret effect size, irrespective of the associated p value (.10 = weak or small association; .30 = moderate correlation; .50 or larger = strong or large correlation). The overall strategy was to exam- ine the data for replicated patterns with non-negligible effect sizes. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 19; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results Participant characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 1. The study sample at Baseline consisted of 45 women who were primarily White and averaged 50.14 years of age. The women in this sample fell into the category of “obese” (BMI ≥ 30) with an average BMI of 33.25, (SD = 5.68), ranging from 25.6 to 52.6. The mean weight of participants was 89.9 kilo- grams. Just under half of the original sample (N = 20) were still participating in the study 12 months after the initial study began, resulting in a 44% retention rate one year later. Finally, a one-way MANOVA was conducted to ascertain if there were differences at Baseline between completers and non- completers on the study variables of body weight, BMI, and GCS scores. The results were found to be nonsignificant, Pil- lai’s Trace F (6, 39) = .44, p = .78. Finally, study variables at all four time points were examined for departures from normal- ity. BMI and the Green Climacteric Scale scores were fairly normally distributed. One variable, body weight, showed some positive skew but fell well within a normal range for skew by six months follow-up. However, given the nature of the group intervention (e.g., weight loss), some positive skew for body weight was expected as the stated criteria for inclusion in the group was that one had to qualify as “overweight”. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 200  S. R. DAISS ET AL. Table 1. Participant’s baseline characteristics (N = 45). Age (years, mean + SD) 50.14 (12.16) BMI (KG/m2) 33.30 (5.70) Weight (kg) 89.90 (17.90) Ethnicity (%) Caucasian 86.70 Hispanic 6.70 American Indian 2.20 Non-Responders 4.40 Education (%) Post High School 24.40 College Degree 31.10 Post Baccalaureate 40.00 Non-Responders 4.40 Marital Status (%) Single 24.40 Married 64.40 Living Together 2.20 Widowed 4.40 Non-Responders 4.40 Family Income per Year <$50,000 22.20 $50 - 75,000 31.10 $75 - 100,000 22.20 >$100,000 22.20 Non-Responder 4.40 Weight Loss and BMI It was hypothesized that the Small Change Intervention (SCI) method of lifestyle modification program, administered weekly over twelve weeks and bi- and tri-weekly, then monthly, for a follow-up period lasting an additional 9 months, would result in a significant reduction in initial body weight and BMI. Based on the previous SCI studies, a body weight change in the range of 5% was expected and found. Average BMI across the twelve-month program decreased from 33.67 (std = 7.03) to 30.90 (std = 6.13). A one-way repeated measure ANOVA was significant, Pillai’s Trace F (3,15) = 4.98, p = .014, ηp2 = .50, revealing that BMI had significantly changed over time. Post- hoc analyses revealed that BMI at the 3 month, 6 month and 12 month assessments were all significantly lower than baseline (ts ranged from 3.67 to 3.87, ps ranged from. 001 to .002). How- ever, there were no significant differences between the BMI scores between the 3, 6, and 12-month assessments (ts ranged from .35 to 1.74, ps ranged from .10 to .74). See Table 2. Average body weight decreased from 90.83 kgs (std = 23.64) to 85.05 kgs (std = 21.55); a total loss of 5.78 kgs, or a 6.4% reduction in body weight. Average body weight was lowest at the six month follow-up (84.55 (std = 21.22) with an average loss of 6.28 Kg or 6.9% reduction in body weight. A one-way repeated measure ANOVA was significant, Pillai’s Trace F Table 2. Means for body weight, BMI, and GCS over 12 months. Time F (3, 15) Baseline3 Months 6 Months 12 Months Body Weight90.83a (23.63) 86.83b (21.90) 84.55c (21.22) 85.05bc (21.56) 13.20** BMI 33.67a (7.03) 31.71b (6.23) 31.09b (7.33) 30.90b (6.13) 5.00** GCS 10.83a (7.38) 7.67b (9.68) 8.22b (10.13) 6.67b (8.06) 5.40** Note: Means (and standard deviations) for post hoc tests. Means with different subscripts differ significantly at p < .10; **p < .01. (3,15) = 13.20, p = .001, ηp2 = .73, revealing that weight had significantly changed over time. Post-hoc analyses revealed that body weight at the 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month assess- ments were all significantly lower than baseline (ts ranged from 4.52 to 6.92, ps = .0001). Weight loss was also significant be- tween the 3 and 6 month assessment, t (1) = 3.06, p = .006). However, there were no significant differences between the weight loss between 3 and 12 month and 6 and 12 months (ts 1.73 and –.66 respectively, ps = .10 and .52 respectively). See Table 2. Menopausal Symptoms In order to assess if BMI and body weight (KG) were associ- ated with greater menopausal symptoms at each assessment point, four sets of correlational analyses were conducted. At baseline, menopausal symptoms were not significantly corre- lated with body weight, r(43) = .08 or BMI, r(43) = −.00. At the three month follow-up, the correlations were small but posi- tive (body weight: r(32) = .22; BMI: r(32) =.16). At the six month follow-up, the correlations were moderate and signifi- cant (body weight: r(25) = .48, p = .016; BMI: r(25) = .36, p = .074). At the nine month follow-up, the correlations remained moderate and significant (body weight: body weight: r(18) = .42, p = .08; BMI: r(18) = .44, p = .07. Taken together, these results indicate that body weight and BMI were weakly to moderately associated with increased menopausal symptoms at the end of the 12 week treatment in this small sample, but con- sistently and significantly related by the six and nine month marks following the treatment intervention. It was hypothesized that the SCI method of lifestyle modification would result in a statistically significant reduction in GCS scores over time. A one-way within-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using GCS scores as the dependent variable. As hypothesized, there was a significant decrease in average CGS scores across the span of the weight loss program. F (3,15) = 5.40, p = .01, partial ηp2 = .52. Post-hoc tests indicated that scores were significantly lower at the 3, 6, and 9 month follow up as compared to baseline scores (ts ranged from 2.00 to 3.38, ps ranged from .06 to .008). There were no statistical differ- ences between the 3, 6, and 9 month assessments (ts ranged -.42 to 1.14, ps ranged .27 to .67). See Table 2. Finally, it was hypothesized that weight loss among over- weight and obese women who completed the SCI program would be associated with lower menopausal symptoms at the 12-month follow-up assessment. To examine these hypotheses, two change scores were computed by subtracting the Baseline measures of body weight and BMI from their respective 12- month, end of study scores. Higher scores on these change Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 201  S. R. DAISS ET AL. variables represented greater weight loss and greater reductions in BMI over time. Next, these two change scores were corre- lated with the 12-month measure of menopausal symptoms. Seen in Table 3, as expected, BMI change scores were found to be significantly and negatively related to GCS scores, r(18) = –.37, p = .07 (one-tailed). That is, participants whose BMI scores had a greater decrease over time also reported fewer menopausal symptoms at the final assessment. The result for weight loss was also in the moderate range for correlations, but due to the small sample size was not significant, r(18) = –.24, p = .17 (one-tailed). See Table 3. Discussion This study examined how psychological principles related to goal-setting and motivation can be applied to a cognitive-be- havioral program designed to reduce the long-term physical and psychological effects of obesity and menopausal symptoms in women. To date, the impact of weight loss and reductions in BMI on women’s experience of menopause has not been widely examined. As hypothesized, results of this study provide further support for the use of an intervention based on sound and well researched literature on effective goal setting. The Small Changes approach, which incorporated self-directed goal setting, expertise, group support, and other program elements designed to increase self-efficacy, coupled with a follow-up period of support, was effective in moderate weight loss of 6.4% initial body weight over a 12-month period. Findings of this study mirror that of previous research using similar meth- odology (Damschroder et al., 2010; Lutes et al., 2012; Lutes, Daiss, et al., 2012; Lutes et al., 2008). A 5% - 10% decrease in body weight has been shown to be beneficial in a variety of health outcomes, as well (Fabricatore & Wadden, 2006; Jeffrey et al., 2000; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1998). Although the women in the sample also evidenced a significant reduction in BMI, their mean BMI scores still placed them in the obese category by their last assessment period (Mean BMI = 30.9). However, it is important to note that a modest 5% de- crease in body weight (which was accomplished in this study) has been shown to provide numerous health benefits, even if the reduction still leaves the individual well above a normal weight range (Fabricatore & Wadden, 2006; Jeffrey et al. 2000, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1998). Results of this study also demonstrate both cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence regarding the relationship between obesity and menopausal symptoms. First, at each assessment period, women with higher body weights and higher BMIs reported more menopausal sym- ptoms. Conversely, and as predicted, women with lower body weights and lower BMIs reported fewer menopausal symptoms. Furthermore, the strength of these relationships increased over time. These results are consistent with findings from earlier re- search about the relationship between menopausal symptoms and Table 3. Correlations among weight and BMI Change variables and GCS at 12 months. Weight Change BMI change GCS 12 month Weight Change - BMI Change .60*** - GCS 12-month –.24 –.37* - *p < .10; ***p < .01. excess body weight (e.g., Freeman et al., 2001; Gold et al., 2000). More importantly, because this study examined these relation- ships longitudinally, the data revealed that women who experi- ence a greater reduction in BMI over the course of the interven- tion report fewer menopausal symptoms at the follow-up as- sessment period. These finding are consistent with the only other study to find reductions in hot flushes over the course of a behavioral weight loss program (Huang et al., 2010). Additionally, the biggest drop in overall menopausal symp- tom scores co-occurred with the biggest decreases in BMI/body weight, during the first three months of the program. This three-month window of assessment may point to a critical pe- riod in which positive physiological and psychological benefits are most likely to occur. It is also the time period in weight loss trials when researchers may expect the largest observations in weight loss. These results underscore the importance of apply- ing psychological principles to real-world problems, and that behavior modification programs based on empirically tested effective forms of goal-setting (and enhanced motivation) may be more effective than programs based on short-term imple- mentation of unrealistic goals. We identify several limitations to this study. The first con- cerns our small sample size. One of the most difficult aspects of long-term weight-loss interventions is minimizing drop out rates. Our retention rate of 44%, obtained over one year’s time, resulted in a small sample size. In the weight loss literature, a 60% retention rate is usually standard, even when extensive follow-up contact measures for no-show participants are used (Ware, 2003). As with other past studies, our attrition was pri- marily among non-white participants (Honas, Early, Frederick- son, & O’Brien, 2003), suggesting an important area for future investigations. Thus, given our attrition rate and small sample size, our findings should be considered preliminary and en- courage future work that examines not only the effectiveness of small change behavioral modification, but also explores the potential causes of attrition among non-white women. Another limitation of our study is the lack of a control group. Although a wait-list control group was planned as part of the study, too few individuals were enrolled to properly complete statistical analyses. Future studies would benefit from the in- clusion of a matched control group. With only one other study (Huang et al., 2010) finding that losing weight and/or attending weight loss groups may be beneficial in the reduction of meno- pausal symptoms, further research with larger sample sizes and control groups is needed to validate these findings. Additionally, symptoms may vary in response to menopausal status (e.g., Laferrére et al. (2000), from periomenopause to menopause to postmenopause, so it would be beneficial to develop and com- pare interventions within these time frames. In spite of the limitations, our study’s strengths include the application of important psychological principles to an inter- vention that has long-term effectiveness for weight loss and menopausal symptom reduction. Given the psychological and physical distress associated with menopausal symptoms, and the relative dearth of studies that specifically examine the link between obesity and menopausal symptoms in women, our study results have important implications for women’s health and well-being. Conclusion Goal setting and task motivation theory argues that success- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 202  S. R. DAISS ET AL. ful formulation and implementation of specific, achievable and relevant goals, in a setting that affirms and increases self-effi- cacy through expert guidance, social support, and success (La- tham, Winters, & Locke 1994; Wood & Bandura, 1989) are central to designing effective diet and exercise protocols. Ac- cordingly, health care professionals are urged to consider the application of existing psychological research that provides evidence that to fight obesity and associated menopausal symp- toms a Small Changes approach is effective. In our SCI ap- proach obese and overweight women were supported and en- couraged to “do their best” for meeting their diet and exercise goals instead of utilizing intervention strategies that encouraged evaluative pressure and performance anxiety which would likely have interfered with effective behavior modification (Early, Connolly, & Ekegren, 1989). Our study results provide further evidence of a significant reduction in menopausal symp- toms for its participants over a 12-month period. Continued attention towards women’s issues in weight loss and meno- pause is needed. REFERENCES Borgmeier, I., & Westenhoefer, J. (2009). Impact of different food label formats on healthiness evaluation and food choice of consumers: A randomized-controlled study. BioMedCentral Pu bl i c H e al t h , 9, 184. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-184 Carpenter, K. M., Hasin, D. S., Allison, D. B., & Faith, M. S. (2000). Relationship between obesity and DSM-IV major depressive disorder, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts: Results from a general popu- lation. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 251-257. Chedraui, P., Aguirre, W., Calle, A., Hidalgo, L., Leon-Leon, P., Mi- randa, O., Martinez, N., Mendoza, M., Narvaez, J., Sanchez, H., Sch- wager, G., Quintero, J. C., Zambrano, B., Aguilar, A., Martinez, M. A., Rivera, R., & Ruilova, I. (2010). Risk factors related to the pres- ence and severity of hot flushes in mid-aged Ecuadorian women. Mauritas, 65, 378-382. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.024 Chen, R., Davis, S., Wong, C., & Lam, T. (2010). Validity and cultural equivalence of the standard Greene Climacteric Scale in Hong Kong. Menopause, 17, 630-635. Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Damschroder, L. J., Lutes, L. D., Goodrich, D. E., Gillon, L., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). A small-change approach delivered via telephone pro- motes weight loss in veterans: Results from the ASPIRE-VA pilot study. Patient Education and Counseling, 79, 262-266. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.025 Earley, P. C., Connolly, T., & Ekegren, G. (1989). Goals, strategy de- velopment and task performance: Some limits on the efficacy of goal setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 24-33. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.1.24 Epstein, L. H., Paluch, R. A., Roemmich, J. N., & Beecher, M. D. (2007). Family-based obesity treatment, then and now: Twenty-five years of pediatric obesity treatment. Health Psychology, 26, 381-391. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.381 Epstine, L. H., & Squires, S. (1988). The stop-light diet for children. Boston: Massachussets. Fabricatore, A. N., & Wadden, T. A. (2006). Obesity. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2 , 357-377. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095249 Freeman, E. W., Sammel, M. D., Grisso, J. A., Battistini, M., Garcia- Espagna, B., & Hollander, L. (2001). Hot flashes in the late repro- ductive years: Risk factors for African American and Caucasian wo- men. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 10, 67- 76. doi:10.1089/152460901750067133 Gallicchio, L., Visvanathan, K., Miller, S. R., Babus, J., Lewis., L. M., Zacur, H., & Flaws, J. A. (2005). Body mass, estrogen levels, and hot flashes in midlife women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gy- necology, 193, 1353-1360. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.04.001 Gold, E., Block, G., Crawford, S., Lachance, L., FitzGerald, G., Mira- cle, H., & Sherman, S. (2004). Lifestyle and demographic factors in realtion to vasomotor symptoms: Baseline results from the study of women’s health across the nation. American Journal of Epidemiol- ogy, 159, 1189-1199. Gold, E., Sternfeld, B., Kelsey, J., Brown, C., Mouton, C., Reame, N., Salamone, L., & Stellato, R. (2000). Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152, 463-473. doi:10.1093/aje/152.5.463 Gorton, D., Mhurchu, C. N., Chen, M. H., & Dixon, R. (2009). Nutri- tion labels: A survey of use, understanding and preferences among ethnically diverse shoppers in New Zealand. Public Health Nutrition, 12, 1359-1365. doi:10.1017/S1368980008004059 Greene, J. G. (1998). Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Mauri- tas, 29, 25-31. ddoi:10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00025-5 Hollis, J. F., Gullion, C. M., Stevens, V. J., Brantley, P. J., Appel, L. J., Ard, J. D., Champagne, C. M., & Svetkey, L. P. (2008). Weight loss during the intensive intervention phase of the weight-loss mainte- nance trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 118-126. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.013 Honas, J., Early, J., Frederickson, D., & O’Brien, M. (2003). Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obesity Re- search, 7, 888-894. doi:10.1038/oby.2003.122 Huang, A. J., Subak, L. L., Wing, R, West, D., Hernandex, A. L., Macer, J., & Grady, D. (2010). An intensive behavioral weight loss intervention and hot flushes in women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170, 1161-1167. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.162 Jeffery, R. W., Drewnowski, A., Epstein, L. H., Stunkard, A. J., Wilson, G. T., & Wing, R. R. (2000). Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychology, 10, 5-16. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.19.Suppl1.5 Laferrére, B., Zhu, S., Clarkson, J. R., Yoshikoka, M. R. M., Kruaskopf, K., Thornton, J. C., & Pi-Sunyer, F. X. (2000). Race, menopause, health-related quality of life, and psychological well-being in obese women. Obesity Research, 10, 1270-1272. doi:10.1038/oby.2002.172 Latham, G. P., & Seijts, G. H. (1999). The effects of proximal and distal goals on performance on a moderately complex task. Journal of Organizational Behavior , 20, 421-429. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199907)20:4<421::AID-JOB896>3.0. CO;2-# Latham, G. P., Winters, D., & Locke, E. (1994). Cognitive and motivi- tional effects of participation: A mediator study. Journal of Organ- izational Behavior, 15, 49-63. doi:10.1002/job.4030150106 Locke, E. A. (2000). Motivation, cognition, and action: An analysis of studies of task goals and knowledge. Applied Psychology: An Inter- national Review, 49, 408-429. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00023 Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory or organizational management. Academy of Management Re- view, 14, 361-384. Lutes, L. D., Daiss, S. R., Barger, S. D., Read, M., & Winett, R. A. (2012). A small change approach promotes initial and continued weight loss with a phone-based follow-up: Nine-month outcomes from ASPIRES American Journal of Health Promotion, 26, 235-238. Lutes, L. D., Winett, R. A., Barger, S. D., Wojcik, J. R., Herbert, W. G., Nickols-Richardson, S. M., & Anderson, E. S. (2008). Small changes in nutrition and physical activity promote weight loss and mainte- nance: 3-month evidence from the ASPIRE randomized trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 25, 351-357. doi:10.1007/s12160-008-9033-z Lutes, L. D., Daiss, S. R., Errickson, M. A., Barger, S. D. & Winett, R. A. (2012). Small changes can promote initial and continued weight loss delivered in person or using the internet: Nine-month results from the ASPIRE III pilot study. In Press. Mokdad, A. H., Marks, J. S., Stroup, D. F., & Gerberding, J. L. (2004). Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 1238-1245. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1238 National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute (NHLBI) (1998). Clinical Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 203  S. R. DAISS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 204 guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of over- weight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. Obesity Research, 6, 51S-210S. National Weight Control Registry (n.d.) URL (last checked 13 March 2013). http://www.nwcr.ws/ Paxman, J. R., Hall, A. C., Harden, C. J., O’Keeffe, J., & Simper, R. N. (2011). Weight loss is coupled with improvements to affective state in obese participants engaged in behavior change therapy based on incremental, self-selected “Small Changes”. Nutrition Research, 31, 327-337. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2011.03.015 Puhl, R. M.., & Brownell, K. D. (2003). Psychosocial origins of obe- sity stigma: Toward changing a powerful and pervasive bias. Obesity Reviews, 4, 213-227. doi:10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00122.x Schilling, C., Gallicchio, L., Miller, S. R., Langenber, P., Zacur, H., & Flaws, J. A. (2007). Relation of body mass and sex steroid hormone levels to hot flushes in a sample of mid-life women. Climacteric, 10, 27-37. doi:10.1080/13697130601164755 Sterns, V., Ullmer, L., Lopez, J. F., Smith, Y., Isaacs, C., & Hayes, D. (2002). Hot flushes. Lancet, 360, 1851-1861. Strychar, I. (2006) Diet and weight loss-response. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 175, 1407. Ware, J. (2003) Interpreting incomplete data in studies of diet and weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2136-2137. doi:10.1056/NEJMe030054 Whiteman, M. K., Staropoli, C. A., Langenberg., P. W., McCarter, R. J., Kjerulff, K. H., & Flaws, J. A. (2003). Smoking, body mass, and hot flashes in midlife women. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 101, 264-272. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02593-0 Williams, R. E., Levine, K. B., Kalilani, L., Lewis, J., & Clark, R. V. (2009). Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US popula- tion-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas, 62, 153-159. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.006 World Health Organization (2013). URL (last checked 13 March 2013). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social-cognitive theory of organiza- tional management. Academy of Management Review, 14, 361-384.

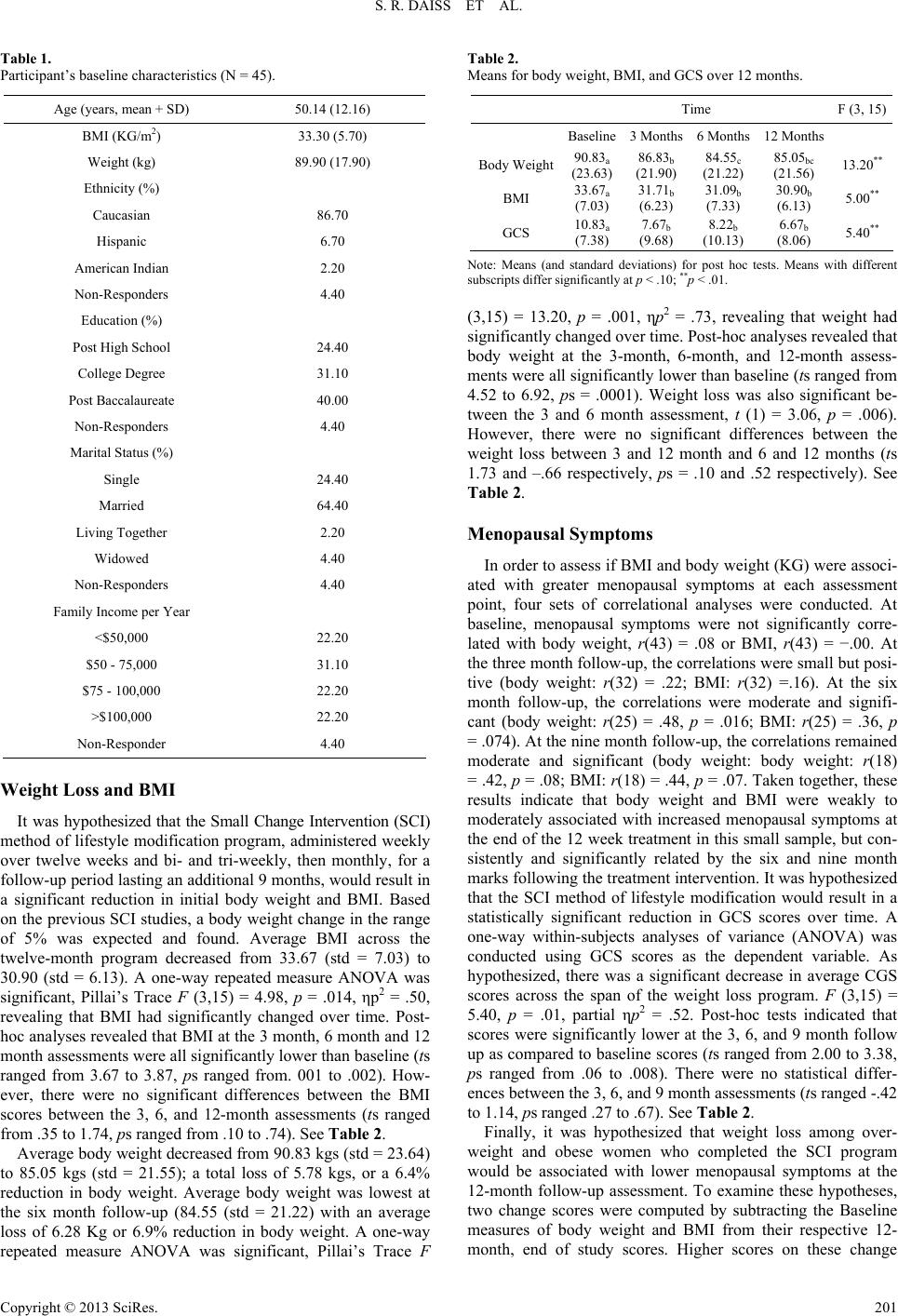

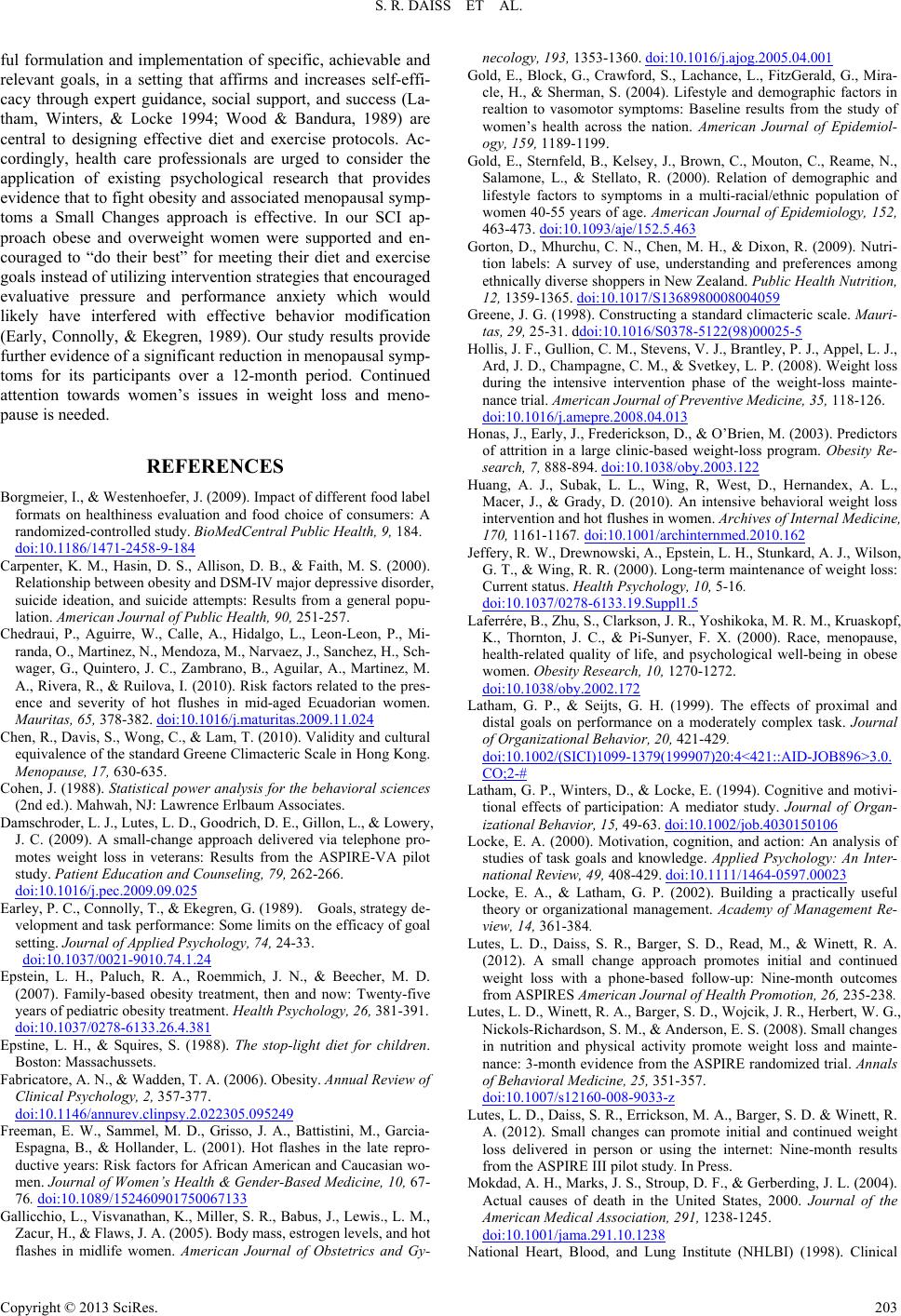

|