Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

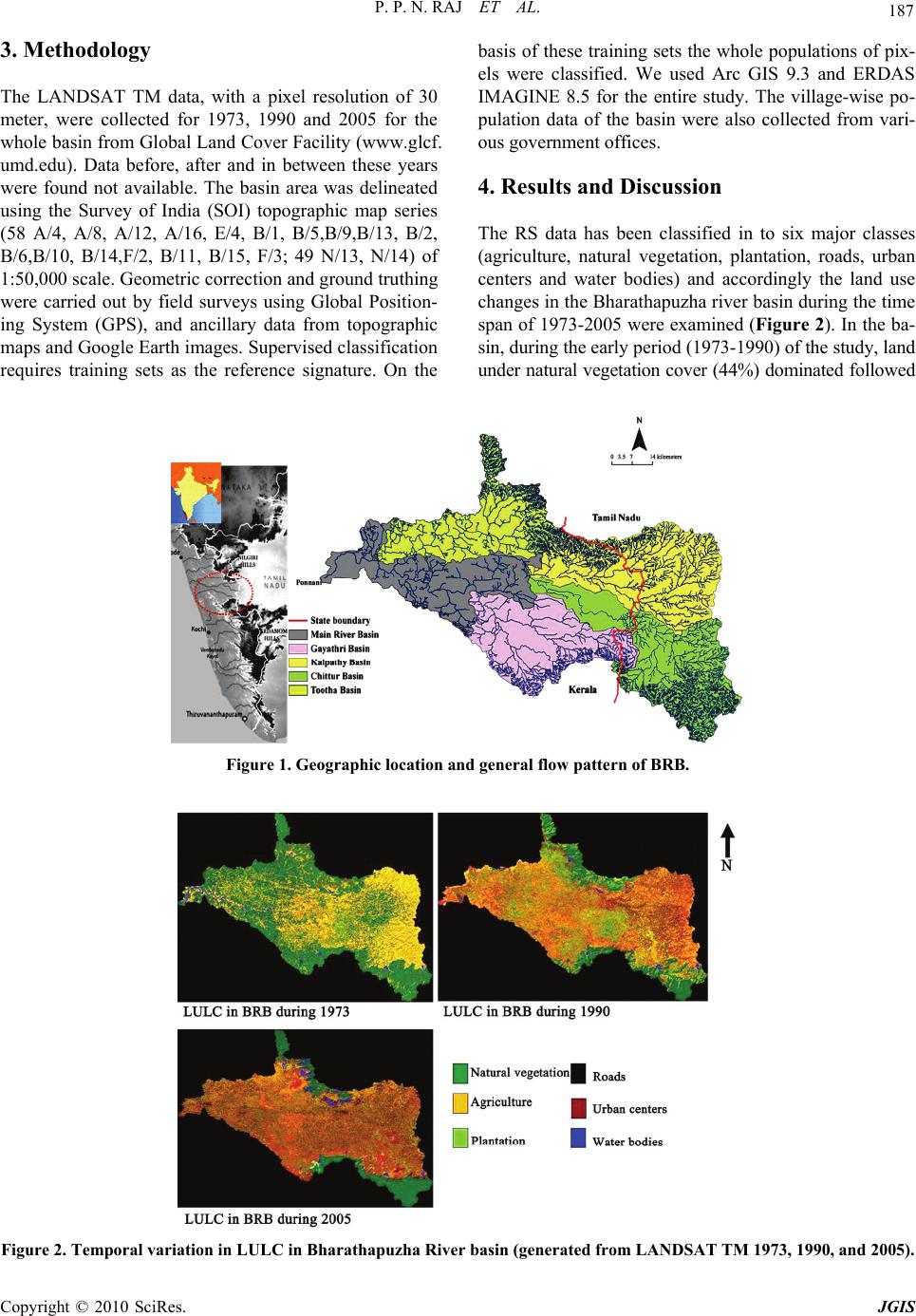

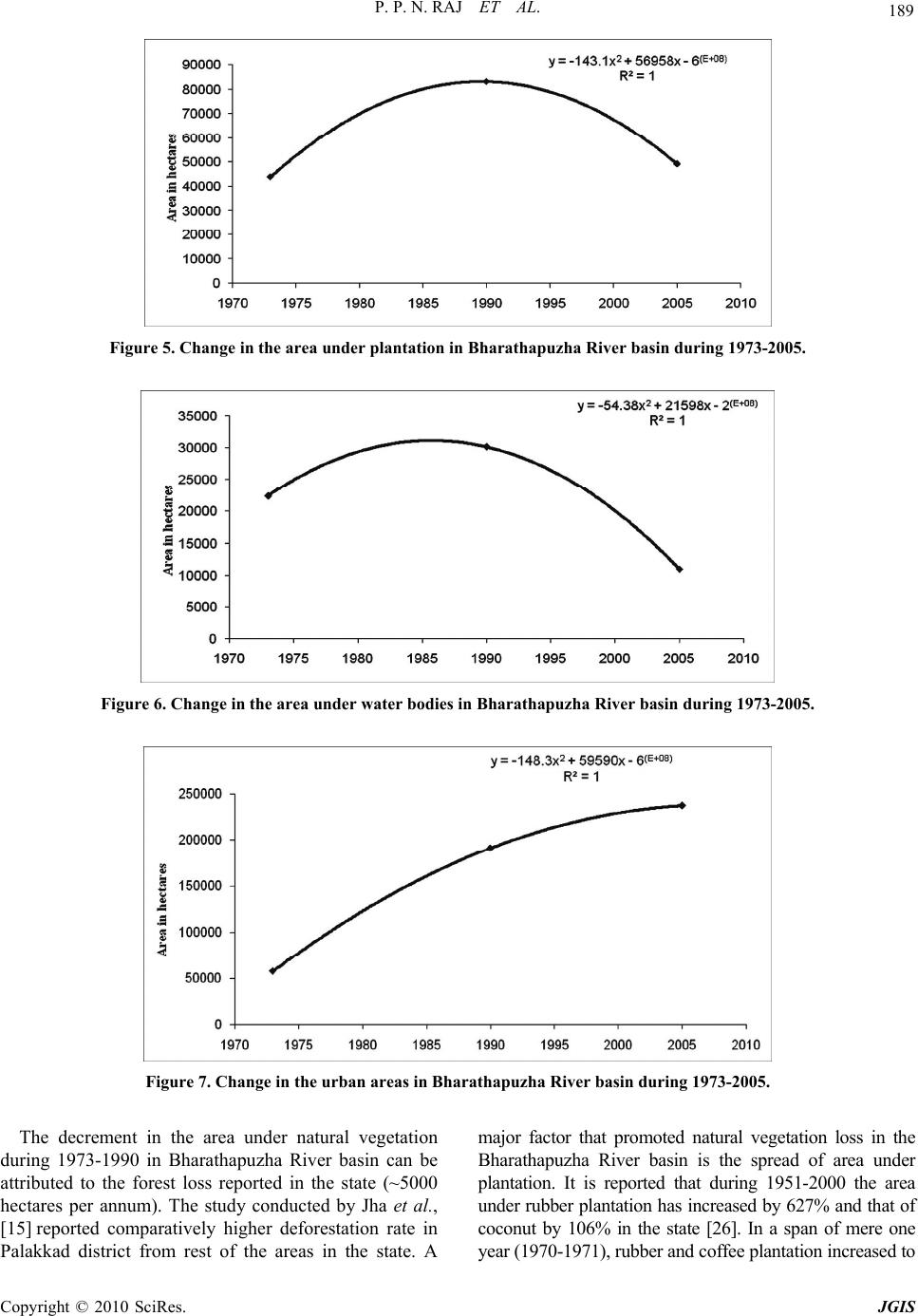

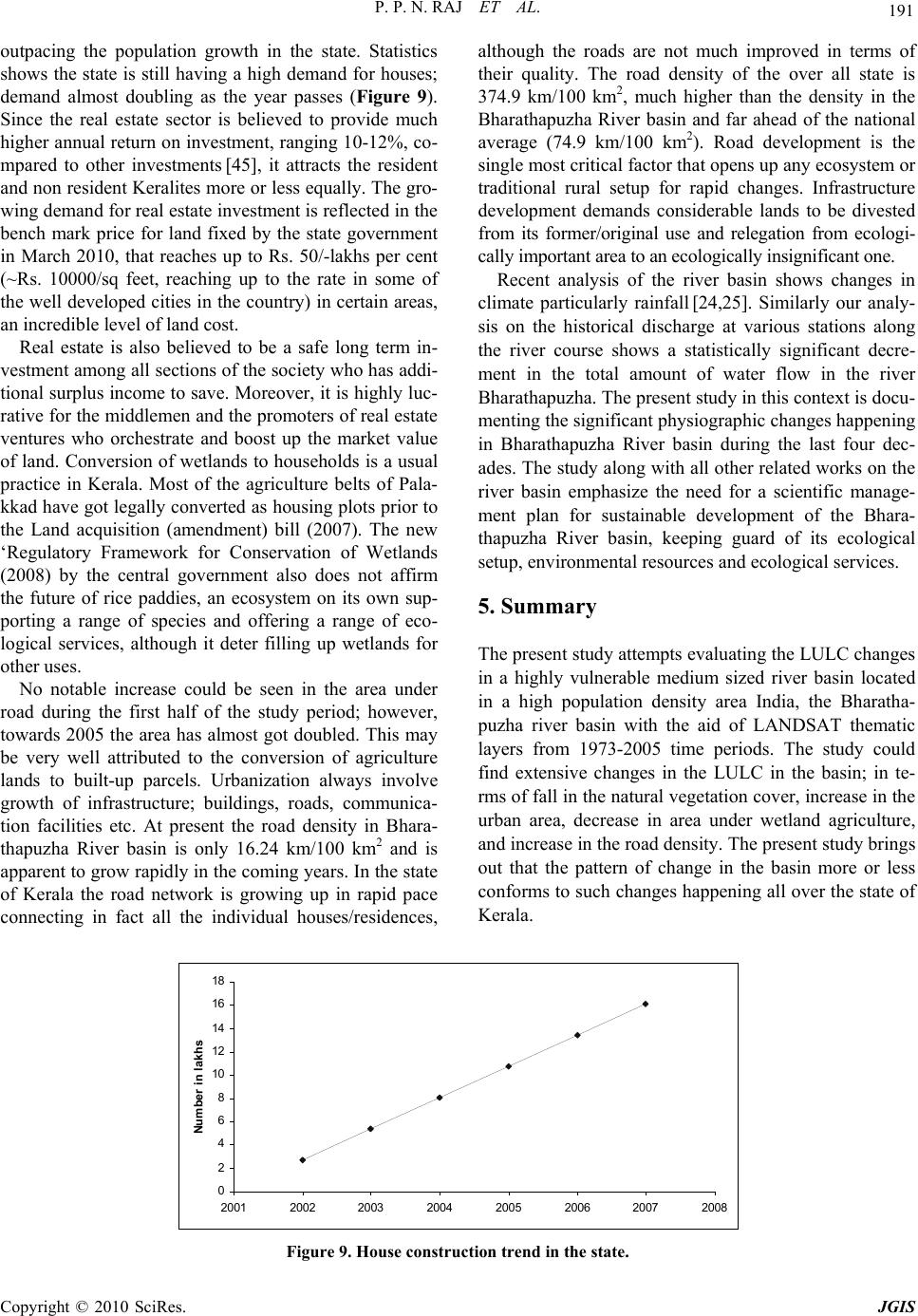

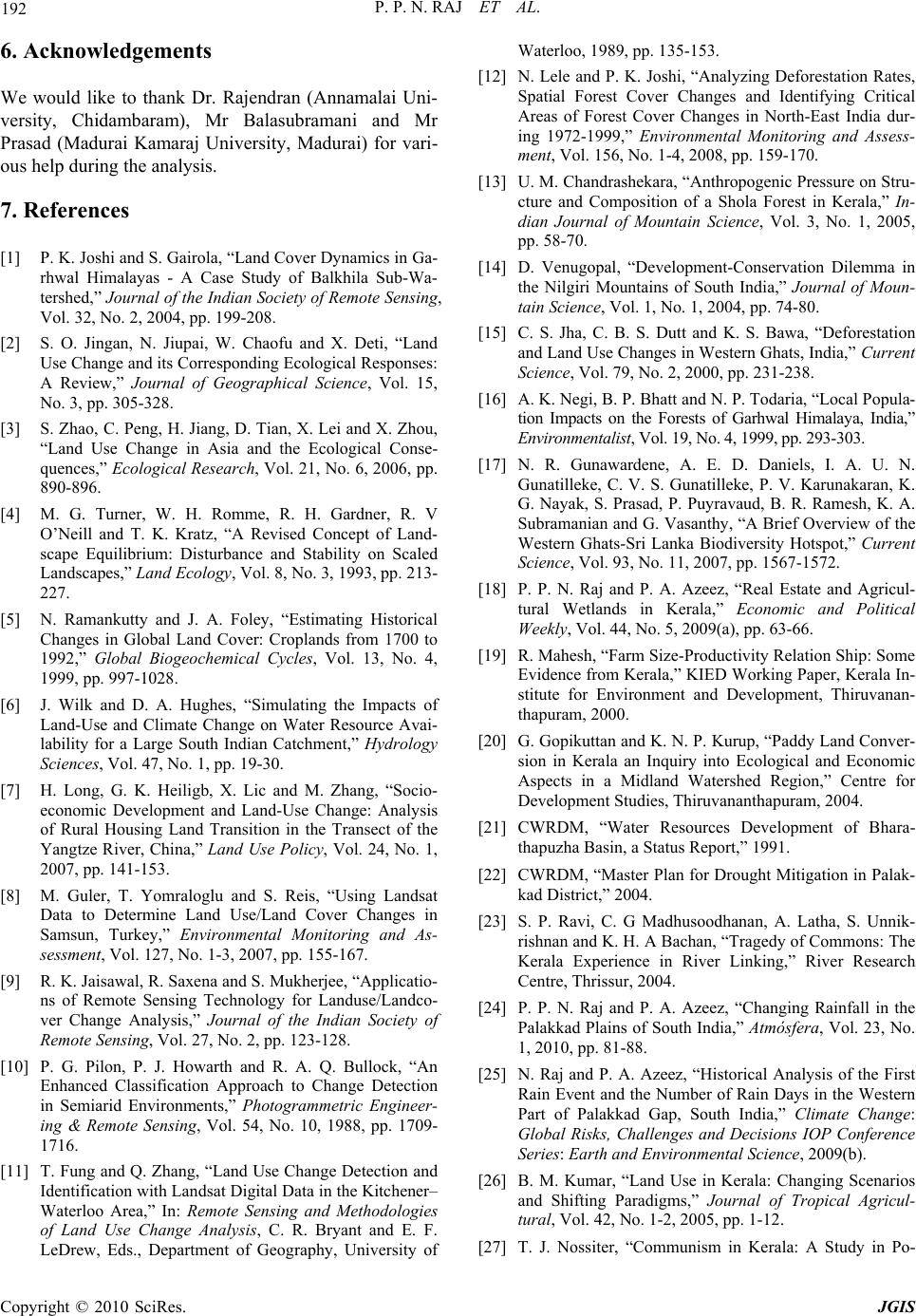

Journal of Geographic Information System, 2010, 2, 185-193 doi:10.4236/jgis.2010.24026 Published Online October 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jgis) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS Land Use and Land Cover Changes in a Tropical River Basin: A Case from Bharathapuzha River Basin, Southern India P. P. Nikhil Raj, P. A. Azeez Environmental Impact Assessment Division, Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History Anaikatty, India E-mail: {ppnraj, azeezpa}@gmail.com Received May 8, 2010; revised June 20, 2010; accepted June 25, 2010 Abstract A study of the spatial and temporal changes in land use and land cover (LULC) was conducted using Remote Sensing and GIS. We analyzed the LULC of Bharathapuzha river basin, south India using multispectral LANDSAT imageries of 1973-2005 time periods. 31% depletion in the natural vegetation cover and 8.7% depletion in wetland agriculture area were seen in the basin during the period. On the other hand the urban spread in the basin increased by 32%. The study highlights the need for a scientific management plan for the sustainability of the river basin, keeping in view the recent climatic anomalies and hydrological conditions of the basin. Keywords: Land Use and Land Covers (LULC), Bharathapuzha River Basin, RS, GIS 1. Introduction Landscape changes, transformations and conversions, are results of various pressures on ecosystems and have been progressing largely in concert with human settlements. All the natural areas including forests, grasslands, wet- lands, and shores around the globe often undergo diverse kinds of transformation and conversion in varying de- grees. The triggering factors for landscape changes may be biophysical, technological, institutional or economical [1-3]. Analyzing the spatial and temporal changes in land use and land cover (LULC) is one of the effective ways to understand the current environmental status of an area and ongoing changes. Urbanization, a major cause of land use changes and land conversions [4], has made natural habitats open to unpredictable and long lasting changes that may later challenge the very existence of the ecosy- stems that offer several known and unknown precious ecosystem goods and services. It is obvious that the world is undergoing a shift from predominantly rural based society to urban. At present in North America, Europe and Latin America more than 70% of population has become urban and in Asia and Africa the figure will be around 40%. According to the Population Reference Bureau (2007), by 2030 more than 60% of the whole world’s population will be urban. Du- ring the last three centuries in the world nearly 1.2 mi- llion km2 of forests and woodlands, 5.6 million km2 of grasslands and pastures have been converted into other types of land use, and the cropland has increased sharply to twelve million km2 during the same time span [5]. However, the blame for such changes and urbanization could not be totally placed on population increase since large proportion of the humankind still remains homeless and with deplorable purchase power to meet their day-to- day survival requirements. Development and welfare have remained alien to the major section of human population of world over largely due to disparities in distribution and access to resources. As far as a river basin is concerned, the spatio-temp- oral changes in land use in the basin have a direct infl- uence on its hydrological realm [6]. Currently fresh wa- ter resources in several parts of the globe is facing severe crisis in availability due to unsustainable water use aggr- avated by the unpredictable and unforeseen changes in the global and local climate. The climate change coupled with urbanization and rampant alterations in land use in the basins made most of the world’s fresh water flow re- gimes under severe pressure and change. Deforestation and conversion of water logged wetlands in to built-up  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 186 areas directly affects the ground water recharging capa- city and natural water flow regimes. Remote Sensing (RS) and GIS have been widely app- lied to understand the LULC changes and is considered to be a powerful tool to document the spatio-temporal changes of an area for the purpose of conservation and management of natural habitats [7,8]. The multispectral satellite images provide satisfactory spectral resolution which in turn offers a reliable means to diagnose LULC changes. Change detection generally employs one of the two basic methods: pixel-to-pixel comparison and post- classification comparison [9]. The post classification me- thod compares two or more separately classified images of different dates [10,11]. In India, large-scale landscape alterations happened just after the independence (www.iipsenvis.nic.in). In this phase ‘development’ was conceived to be the pro- cess of bringing all possible types of lands under plough. Ecological goods and services of the various types of ecosystems and lands were perhaps of little concern or unknown to the then policy makers and advocates of de- velopment. Conservation of ecosystems and species was practically unheard of in practice and its natural areas particularly the forests and wetlands experienced wide spread conversions and modification. Changes have happened both in the plains as well as at higher eleva- tions. The Himalayas [1] and North east India, [12] and Western Ghats are the two major regions in the country that experienced extensive landscape changes [13-16], while these are the two major biodiversity hotspots in the country [17] and vital for the environmental, social and cultural setup of the country. The state of Kerala, flanked by the Western Ghats on its east, is well known for its unique pattern of developm- ent characterized by high level of socio-economic growth. Human resource have been the major asset in the state and non-resident Keralites have been channelizing in large amount of money to the state primarily to support their families back at home [18]. The flow of foreign cur- rency, in recent years to the tune of Indian Rupees 30- 40000 crores per annum, has promoted extensive socio- economic changes and building construction in the state. Profuse landscape changes in Kerala have happened dur- ing the last few decades. Towards the later half of the last century the land use changes were highly associated with the socioeconomic changes that happened in the state such as Land Reform Act (1971) which assured release of huge landholding to the public at large from the hold of feudal landowners [19-20], although the land reforms is blamed to have deprived the indigenous tribes and other such underprivileged and marginal section of their land holdings. The break down of joint families to the growing culture of nuclear family and high popula- tion density coupled with high foreign remittance to the state increased the demand for housing resulting in the process of land conversion becoming more precipitous. In this context the present study was undertaken to eval- uate the LULC change happened in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005. 2. Study Area Bharathapuzha River basin (BRB) is the second longest (209 km) but largest river basin among the west flowing 41 river basins in the Kerala state of India. The river is considered to be one of the east-flowing ‘medium’ rivers of the country. Lying between 10˚ 25' to 11˚15' north and 75˚ 50' to 76˚ 55' east the western most extremity of the Bharathapuzha watershed is located in the Palakkad Gap, the 30 km discontinuity in the other wise continuous Western Ghats. The river originates from different parts of the West- ern Ghats, as small brooks and rivulets which later joins and form four major tributaries namely Kalpathipuzha, Gayathripuzha, Thootha, and Chitturpuzha. The main ri- ver finally discharges to the Arabian Sea at Ponnani on the west coast (Figure 1). The river has a total basin area of 6,186 km2 of which 4,400 km2 falls in the state of Ke- rala and the rest in Tamil Nadu state of India. The river basin covers 1/9 of the total geographical area of the state. The flow regime of the river covers highlands (> 76 m), midlands (76-8 m) and low lands (< 8 m). The surface water potential of the basin is 7478 million m3 and the total utilizable yield is 4,146 million m3 [21]. The river is the life line water resource for a population (approximately four million) residing in four administra- tive divisions, namely Malappuram, Trissur and Palak- kad districts of Kerala and partly Coimbatore, and Thi- ruppur districts of Tamil Nadu. Eleven irrigation projects and several surface dams in the river basin cater 493064 ha agriculture [22,23]. The general land use in the basin varies according to the local physiography. Rice and co- conut are the dominant crops in the costal regions of the basin. In the mid lands the major crops are rice, banana, tapioca, seasonal vegetables and coconut while in the high land region and some of the mid land region rubber plantations and coconut grooves dominates. The river ba- sin experiences more or less a unique climate realm from the rest of the state of Kerala perhaps for its location, beginning in the eastern aspect of the Palakkad plains, in the Palakkad Gap, flanked by mountain ranges of the Western Ghats [24]. Anomalies in the general rainfall [25] and in surface temperature of the region have been ob- served in the last couple of decades. In recent years the river basin is also reported to be facing severe dearth of water and drought conditions.  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 187 3. Methodology The LANDSAT TM data, with a pixel resolution of 30 meter, were collected for 1973, 1990 and 2005 for the whole basin from Global Land Cover Facility (www.glcf. umd.edu). Data before, after and in between these years were found not available. The basin area was delineated using the Survey of India (SOI) topographic map series (58 A/4, A/8, A/12, A/16, E/4, B/1, B/5,B/9,B/13, B/2, B/6,B/10, B/14,F/2, B/11, B/15, F/3; 49 N/13, N/14) of 1:50,000 scale. Geometric correction and ground truthing were carried out by field surveys using Global Position- ing System (GPS), and ancillary data from topographic maps and Google Earth images. Supervised classification requires training sets as the reference signature. On the basis of these training sets the whole populations of pix- els were classified. We used Arc GIS 9.3 and ERDAS IMAGINE 8.5 for the entire study. The village-wise po- pulation data of the basin were also collected from vari- ous government offices. 4. Results and Discussion The RS data has been classified in to six major classes (agriculture, natural vegetation, plantation, roads, urban centers and water bodies) and accordingly the land use changes in the Bharathapuzha river basin during the time span of 1973-2005 were examined (Figure 2). In the ba- sin, during the early period (1973-1990) of the study, land under natural vegetation cover (44%) dominated followed Figure 1. Geographic location and general flow pattern of BRB. Figure 2. Temporal variation in LULC in Bharathapuzha River basin (generated from LANDSAT TM 1973, 1990, and 2005).  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 188 by the area under agriculture. During the second half of the study period land under urban centers became im- portant (32%) followed by the area under plantation. The area under agriculture remained almost same (26%), while the area under natural vegetation cover declined to considerably lower proportion in the total area of the basin. In 2005, the area under urban centers remains as the major land use type in the basin, followed by agri- culture at the second position. In over all, the area under the natural vegetation cover consistently showed a trend of decline. On the other hand a positive trend of growth in urban centers in the basin was observed during the whole period (Table 1). The natural vegetation cover in the basin showed a drastic decline during the first half of the study period; however, it remained almost unvarying during the next half (Figure 3). While the agricultural area in the basin was found remaining to be unchanged during the first half of the study period, it showed a notable fall during the next half (Figure 4). On the other hand, area under plantation and under water resources showed a steep increase during the period 1973-1990. During the next half (1990-2005) a steep decrease was seen in these land use types (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The urban area in the basin showed a consistent increase thorough out the stu- dy period (Figure 7). The area under road that remained more or less invariable during the early period rose during the later stage of the study (Figure 8). Table 1. Total land cover (in %) as a proportion to the total area, and the net change during the study period. 1973 1990 2005Change (%) during 1973-1990 Change (%) during 1990-2005 Change (%) during 1973-2005 Agriculture 27.84 27.54 19.15−0.30 −8.39 −8.69 Natural vegetation43.43 12.07 12.28−31.36 0.21 −31.15 Plantation 7.46 14.20 8.646.74 −5.56 1.18 Roads 7.61 8.40 16.240.79 7.83 8.62 Urban centers 9.83 32.63 41.7622.80 9.13 31.93 Water resources 3.82 5.16 1.931.34 −3.23 −1.89 Figure 3. Natural vegetation cover change in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005. Figure 4. Area under agriculture in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005.  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 189 Figure 5. Change in the area under plantation in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005. Figure 6. Change in the area under water bodies in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005. Figure 7. Change in the urban areas in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005. The decrement in the area under natural vegetation during 1973-1990 in Bharathapuzha River basin can be attributed to the forest loss reported in the state (~5000 hectares per annum). The study conducted by Jha et al., [15] reported comparatively higher deforestation rate in Palakkad district from rest of the areas in the state. A major factor that promoted natural vegetation loss in the Bharathapuzha River basin is the spread of area under plantation. It is reported that during 1951-2000 the area under rubber plantation has increased by 627% and that of coconut by 106% in the state [26]. In a span of mere one year (1970-1971), rubber and coffee plantation increased to  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 190 Figure 8. Area under roads in Bharathapuzha River basin during 1973-2005. 117% [27]. Presently, rubber plantations cover about 18% of the total agricultural land and 11% of the total geog- raphical area of the state [28]. Such expansions happened mainly in the highland areas, since these areas were less occupied than the mid and lowland areas of the state and large chunks of lands were under feudal landowners. The conversion of wetland agriculture to more gainful (at that time) plantation crops particularly coconut and arecanut was also happening during the same period due to the social and economic shifts that happened in the country as well as in the state [29,30]. According to George and Chattopadhyay [31] the def- orestation in the state is mainly due to infrastructure dev- elopment, such as roads, hydroelectric and irrigation pro- jects, and other institutional amenities. The reduction in the natural vegetation in the Western Ghats is notably as- sociated with the implementation of Hydroelectric Pro- jects [32-34]. Hydroelectric projects apart from their direct impact on natural habitats cause much higher col- lateral damages by opening up access to remote wilder- ness [35]. The Kanjirapuzha irrigation project in the Thootha puzha sub basin has happened during the period. The initial growth and later decline in area under planta- tion can be correlated with the social, political and eco- nomical shifts in the state as well as in the country. Dur- ing the early nineties with the liberalization of the coun- try’s economy the planters and agriculturists in Kerala faced huge financial crunch with the crash in the market price of their products [36]. For example, import of coco- nut oil for industrial uses and its culinary cheaper substi- tute the palm oil from East Asian countries was a blow to coconut farmers, while freely available and low-cost spices and allies and rubber was a blow to other farmers. The sharp out growth in urban centers in the basin in the initial years is related with the declining natural veg- etation area and in the later years to the decline in area under agricultural wetlands. According to 1981 census the basin had a population of 2 million people, which has increased to 4.6 millions in 2001 [37-40]. Deforestation processes in other parts of the state also are found corre- lated with population growth and infrastructure devel- opment [41]. During the late 90s wetland agriculture and even plantations crops were loosing their attractiveness in the basin, as was the case in several other parts Kerala [19,30,42]. According to Eapen [29] urban agglomera- tions or out growths were rare in Kerala till 1981 while later on their number have been almost doubling every decade. The recent census shows that 25% of the total population of the state comes under urban category, much closer to the national statistics (27.8%). Meanwhile people were also abandoning their agriculture/plantations due to inadequate returns. However, the sudden rise in the real estate market attracted lots of people to invest money in building construction as well in tourism ven- tures [18]. For the high demand for building construction, largely residences, many low lying lands and wetlands at several locations nearby the main river as well as its tributaries are getting filled up and converted. A rapid Growth in real estate business was observed in the state since late nineties [18]. The declaration of the 8th five year plan during 1998 by the central government that assured private support for ‘national housing and ha- bitat development policy’ gave it a further drive. Signifi- cant changes in the laws and regulations, including the urban land (Ceiling and Regulation) act by the central government and amendment to the National Housing Ba- nk (NHB) act provided attractive climate for foreign in- vestments further pushing up the real estate growth [43]. The rapid development in retail, entertainment sectors, financial institutions, information technology centers and the boom in the tourism sector all enhanced the growth. More over the Kerala Land Reform Act (1971) acted towards abolishing the system of joint family (especially matrilineal) and development of nuclear families [44]. This resulted in the growth of nuclear families, of hus- band and wife and unmarried children, and housing units  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 191 outpacing the population growth in the state. Statistics shows the state is still having a high demand for houses; demand almost doubling as the year passes (Figure 9). Since the real estate sector is believed to provide much higher annual return on investment, ranging 10-12%, co- mpared to other investments [45], it attracts the resident and non resident Keralites more or less equally. The gro- wing demand for real estate investment is reflected in the bench mark price for land fixed by the state government in March 2010, that reaches up to Rs. 50/-lakhs per cent (~Rs. 10000/sq feet, reaching up to the rate in some of the well developed cities in the country) in certain areas, an incredible level of land cost. Real estate is also believed to be a safe long term in- vestment among all sections of the society who has addi- tional surplus income to save. Moreover, it is highly luc- rative for the middlemen and the promoters of real estate ventures who orchestrate and boost up the market value of land. Conversion of wetlands to households is a usual practice in Kerala. Most of the agriculture belts of Pala- kkad have got legally converted as housing plots prior to the Land acquisition (amendment) bill (2007). The new ‘Regulatory Framework for Conservation of Wetlands (2008) by the central government also does not affirm the future of rice paddies, an ecosystem on its own sup- porting a range of species and offering a range of eco- logical services, although it deter filling up wetlands for other uses. No notable increase could be seen in the area under road during the first half of the study period; however, towards 2005 the area has almost got doubled. This may be very well attributed to the conversion of agriculture lands to built-up parcels. Urbanization always involve growth of infrastructure; buildings, roads, communica- tion facilities etc. At present the road density in Bhara- thapuzha River basin is only 16.24 km/100 km2 and is apparent to grow rapidly in the coming years. In the state of Kerala the road network is growing up in rapid pace connecting in fact all the individual houses/residences, although the roads are not much improved in terms of their quality. The road density of the over all state is 374.9 km/100 km2, much higher than the density in the Bharathapuzha River basin and far ahead of the national average (74.9 km/100 km2). Road development is the single most critical factor that opens up any ecosystem or traditional rural setup for rapid changes. Infrastructure development demands considerable lands to be divested from its former/original use and relegation from ecologi- cally important area to an ecologically insignificant one. Recent analysis of the river basin shows changes in climate particularly rainfall [24,25]. Similarly our analy- sis on the historical discharge at various stations along the river course shows a statistically significant decre- ment in the total amount of water flow in the river Bharathapuzha. The present study in this context is docu- menting the significant physiographic changes happening in Bharathapuzha River basin during the last four dec- ades. The study along with all other related works on the river basin emphasize the need for a scientific manage- ment plan for sustainable development of the Bhara- thapuzha River basin, keeping guard of its ecological setup, environmental resources and ecological services. 5. Summary The present study attempts evaluating the LULC changes in a highly vulnerable medium sized river basin located in a high population density area India, the Bharatha- puzha river basin with the aid of LANDSAT thematic layers from 1973-2005 time periods. The study could find extensive changes in the LULC in the basin; in te- rms of fall in the natural vegetation cover, increase in the urban area, decrease in area under wetland agriculture, and increase in the road density. The present study brings out that the pattern of change in the basin more or less conforms to such changes happening all over the state of Kerala. 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 2001 20022003 2004 2005 20062007 2008 Number in lakhs Figure 9. House construction trend in the state.  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 192 6. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Dr. Rajendran (Annamalai Uni- versity, Chidambaram), Mr Balasubramani and Mr Prasad (Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai) for vari- ous help during the analysis. 7. References [1] P. K. Joshi and S. Gairola, “Land Cover Dynamics in Ga- rhwal Himalayas - A Case Study of Balkhila Sub-Wa- tershed,” Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2004, pp. 199-208. [2] S. O. Jingan, N. Jiupai, W. Chaofu and X. Deti, “Land Use Change and its Corresponding Ecological Responses: A Review,” Journal of Geographical Science, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 305-328. [3] S. Zhao, C. Peng, H. Jiang, D. Tian, X. Lei and X. Zhou, “Land Use Change in Asia and the Ecological Conse- quences,” Ecological Research, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2006, pp. 890-896. [4] M. G. Turner, W. H. Romme, R. H. Gardner, R. V O’Neill and T. K. Kratz, “A Revised Concept of Land- scape Equilibrium: Disturbance and Stability on Scaled Landscapes,” Land Ecology, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1993, pp. 213- 227. [5] N. Ramankutty and J. A. Foley, “Estimating Historical Changes in Global Land Cover: Croplands from 1700 to 1992,” Global Biogeochemical Cycles, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1999, pp. 997-1028. [6] J. Wilk and D. A. Hughes, “Simulating the Impacts of Land-Use and Climate Change on Water Resource Avai- lability for a Large South Indian Catchment,” Hydrology Sciences, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 19-30. [7] H. Long, G. K. Heiligb, X. Lic and M. Zhang, “Socio- economic Development and Land-Use Change: Analysis of Rural Housing Land Transition in the Transect of the Yangtze River, China,” Land Use Policy, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2007, pp. 141-153. [8] M. Guler, T. Yomraloglu and S. Reis, “Using Landsat Data to Determine Land Use/Land Cover Changes in Samsun, Turkey,” Environmental Monitoring and As- sessment, Vol. 127, No. 1-3, 2007, pp. 155-167. [9] R. K. Jaisawal, R. Saxena and S. Mukherjee, “Applicatio- ns of Remote Sensing Technology for Landuse/Landco- ver Change Analysis,” Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 123-128. [10] P. G. Pilon, P. J. Howarth and R. A. Q. Bullock, “An Enhanced Classification Approach to Change Detection in Semiarid Environments,” Photogrammetric Engineer- ing & Remote Sensing, Vol. 54, No. 10, 1988, pp. 1709- 1716. [11] T. Fung and Q. Zhang, “Land Use Change Detection and Identification with Landsat Digital Data in the Kitchener– Waterloo Area,” In: Remote Sensing and Methodologies of Land Use Change Analysis, C. R. Bryant and E. F. LeDrew, Eds., Department of Geography, University of Waterloo, 1989, pp. 135-153. [12] N. Lele and P. K. Joshi, “Analyzing Deforestation Rates, Spatial Forest Cover Changes and Identifying Critical Areas of Forest Cover Changes in North-East India dur- ing 1972-1999,” Environmental Monitoring and Assess- ment, Vol. 156, No. 1-4, 2008, pp. 159-170. [13] U. M. Chandrashekara, “Anthropogenic Pressure on Stru- cture and Composition of a Shola Forest in Kerala,” In- dian Journal of Mountain Science, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2005, pp. 58-70. [14] D. Venugopal, “Development-Conservation Dilemma in the Nilgiri Mountains of South India,” Journal of Moun- tain Science, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2004, pp. 74-80. [15] C. S. Jha, C. B. S. Dutt and K. S. Bawa, “Deforestation and Land Use Changes in Western Ghats, India,” Current Science, Vol. 79, No. 2, 2000, pp. 231-238. [16] A. K. Negi, B. P. Bhatt and N. P. Todaria, “Local Popula- tion Impacts on the Forests of Garhwal Himalaya, India,” Environmentalist, Vol. 19, No. 4, 1999, pp. 293-303. [17] N. R. Gunawardene, A. E. D. Daniels, I. A. U. N. Gunatilleke, C. V. S. Gunatilleke, P. V. Karunakaran, K. G. Nayak, S. Prasad, P. Puyravaud, B. R. Ramesh, K. A. Subramanian and G. Vasanthy, “A Brief Overview of the Western Ghats-Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot,” Current Science, Vol. 93, No. 11, 2007, pp. 1567-1572. [18] P. P. N. Raj and P. A. Azeez, “Real Estate and Agricul- tural Wetlands in Kerala,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 44, No. 5, 2009(a), pp. 63-66. [19] R. Mahesh, “Farm Size-Productivity Relation Ship: Some Evidence from Kerala,” KIED Working Paper, Kerala In- stitute for Environment and Development, Thiruvanan- thapuram, 2000. [20] G. Gopikuttan and K. N. P. Kurup, “Paddy Land Conver- sion in Kerala an Inquiry into Ecological and Economic Aspects in a Midland Watershed Region,” Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, 2004. [21] CWRDM, “Water Resources Development of Bhara- thapuzha Basin, a Status Report,” 1991. [22] CWRDM, “Master Plan for Drought Mitigation in Palak- kad District,” 2004. [23] S. P. Ravi, C. G Madhusoodhanan, A. Latha, S. Unnik- rishnan and K. H. A Bachan, “Tragedy of Commons: The Kerala Experience in River Linking,” River Research Centre, Thrissur, 2004. [24] P. P. N. Raj and P. A. Azeez, “Changing Rainfall in the Palakkad Plains of South India,” Atmósfera, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2010, pp. 81-88. [25] N. Raj and P. A. Azeez, “Historical Analysis of the First Rain Event and the Number of Rain Days in the Western Part of Palakkad Gap, South India,” Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2009(b). [26] B. M. Kumar, “Land Use in Kerala: Changing Scenarios and Shifting Paradigms,” Journal of Tropical Agricul- tural, Vol. 42, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 1-12. [27] T. J. Nossiter, “Communism in Kerala: A Study in Po-  P. P. N. RAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JGIS 193 litical Adaptation,” Royal Institute of International Af- fairs, Hurst & Co. Publishers, New York, 1982. [28] S. Chattopadhyay and M. Chattopadhyay, “Sustainable Land Management in Kerala, India-A Bio-Physical Ap- proach,” Proceedings of Geo-Information for Sustainable Land Management (SLM), K. J. Beek, K. D. Bie and P. Driessen, Eds., Enschede ITC Journal, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1997, pp. 165-174. [29] M. Eapen, “Economic Diversification in Kerala: A Spa- tial Analysis,” Centre for Development Studies, Thiru- vananthapuram, 1999. [30] N. Raj and P. A. Azeez, “The Shrinking Rice Paddies of Kerala,” Indian Economic Review, Vol. 6, 2009(c), pp. 176-183. [31] P. S. George and S. Chattopadhyay, “Population and Land Use in Kerala, Growing Populations, Changing Landscapes: Studies from India, China, and the United States,” The National Academy of Sciences, The National Academies Press, Washington, 2001. [32] V. M. Meher-Homji, “Probable Impact of Deforestation on Hydrological Processes,” Climatic Change, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1991, pp. 163-173. [33] A. G. Pandurangan and V. J. Nair, “Changing Pattern of Floristic Composition in the Idukki Hydro-Electric Pro- ject Area, Kerala,” Journal of Economic and Taxonomic Botany, Vol. 21, 1996, pp. 15-26. [34] M. K. Soman, K. K. Kumar and N. Singh, “Decreasing Trend in the Rainfall of Kerala,” Current Science, Vol. 57, No. 1, 1998, pp. 7-12. [35] P. A. Azeez, S. Bhupathy, A. Rajasekharan, P. R. Arun, D. Stephan and D. Kannan, “Comprehensive EIA (Bo- tanical and Zoological Aspects) of the Proposed Puy- ankutty Hydroelectric Project, Kerala,” Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON), Coimba- tore, Tamil Nadu, 1999. [36] P. T. Sunil, “Dimensions of Agrarian Distress: The Case of Wayanad District, Kerala,” Financing Agriculture - Natational Journal of Agriculture & Rural Development, 2007, pp. 7-12. [37] Census of India, “District Census Hand Book Palakkad,” 2001(a). [38] Census of India, “District Census Hand Book Thrissur,” 2001(b). [39] Census of India, “District Census Hand Book Malappu- ram,” 2001(c). [40] Census of India, “District Census Hand Book Coimba- tore,” 2001(d). [41] S. Chattopadhyay, “Deforestation in Parts of Western Ghats Region (Kerala), India,” Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 20, 1985, pp. 219-230. [42] R. M. Raj, “Patterns of Social Change among the Migrant Farmers of Kannur District - A Case Study,” Project Re- port Submitted to Kerala Research Programme on Local Development, Centre for Developmental Studies, Thiru- vananthapuram, 2003. [43] H. Joshi, “Identifying Asset Price Bubbles in the Housing Market in India-Preliminary Evidence,” Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, Vol. 27, No. 1-2, 2006, pp. 73- 88. [44] P. N. Sushama, “Transition from High to Replacement- Level Fertility in a Kerala Village,” Health Transition Review, Office of Population Health and Nutrition, New Delhi, Vol. 6, 1996, pp. 115-136. [45] P. G. Mahurkar and Senthil, “Final Paper on Real Estate Fund Management Indian Perspective,” Asian Real Estate Society, AsRES Conference, New Delhi, 2004. |