Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

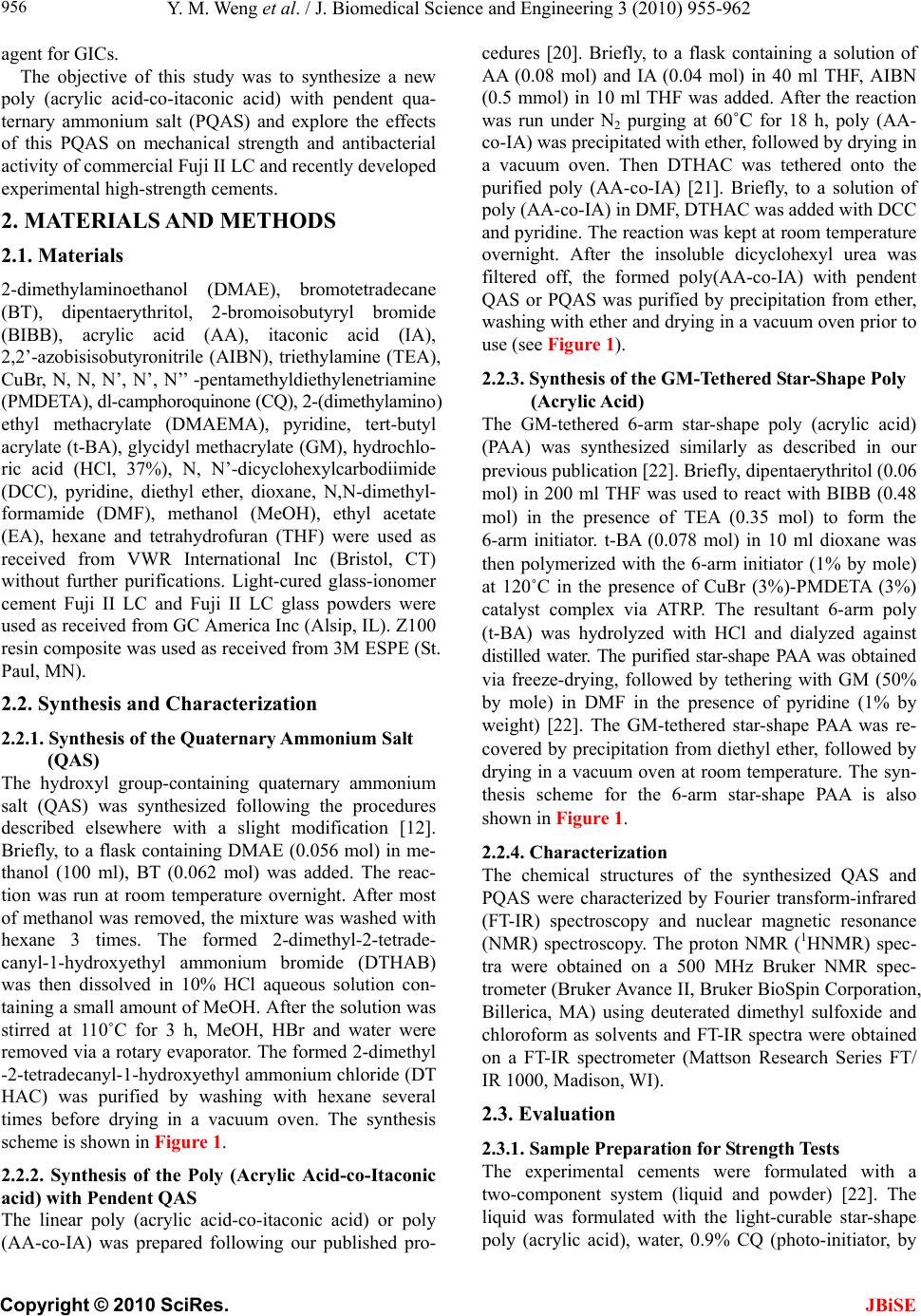

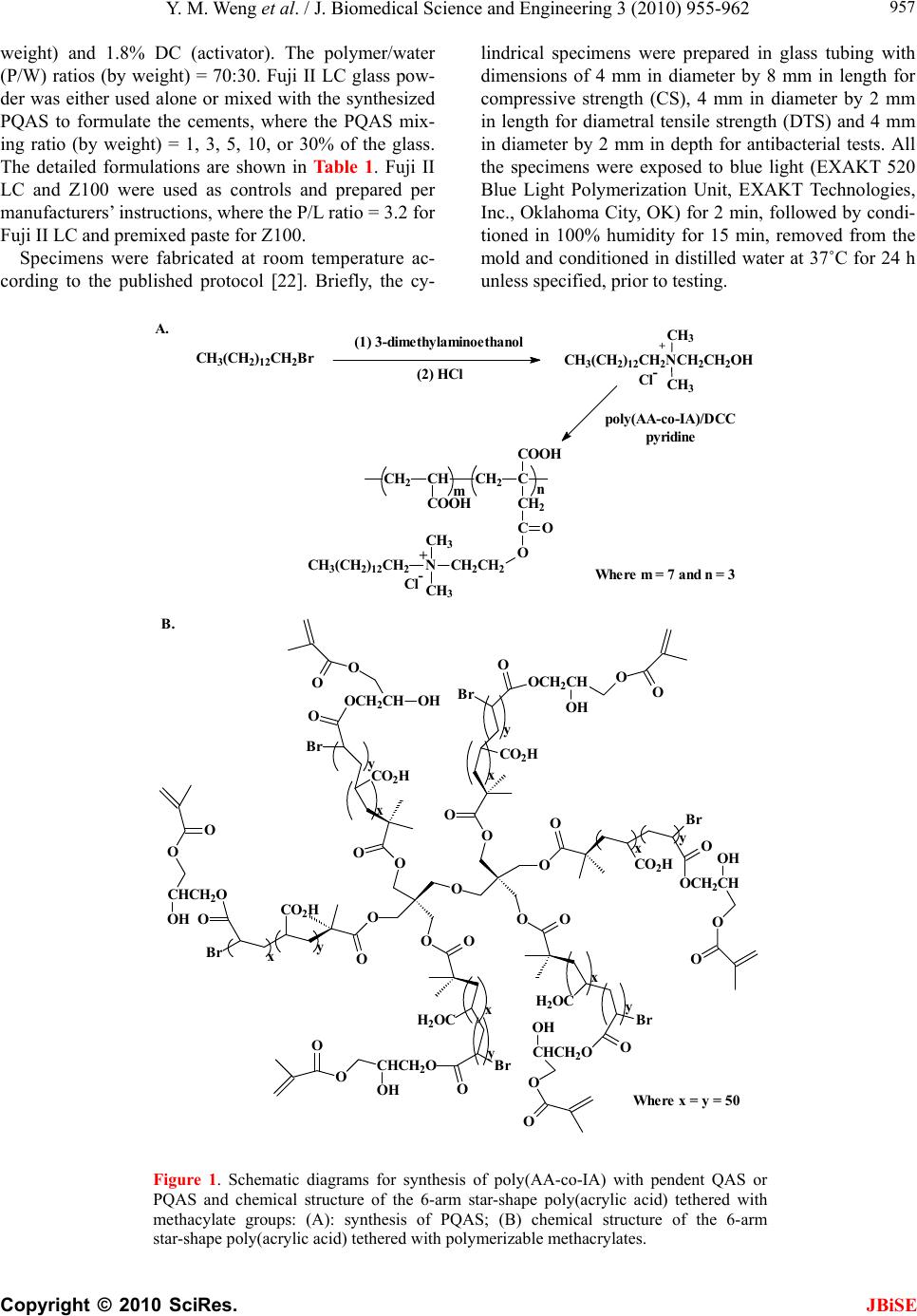

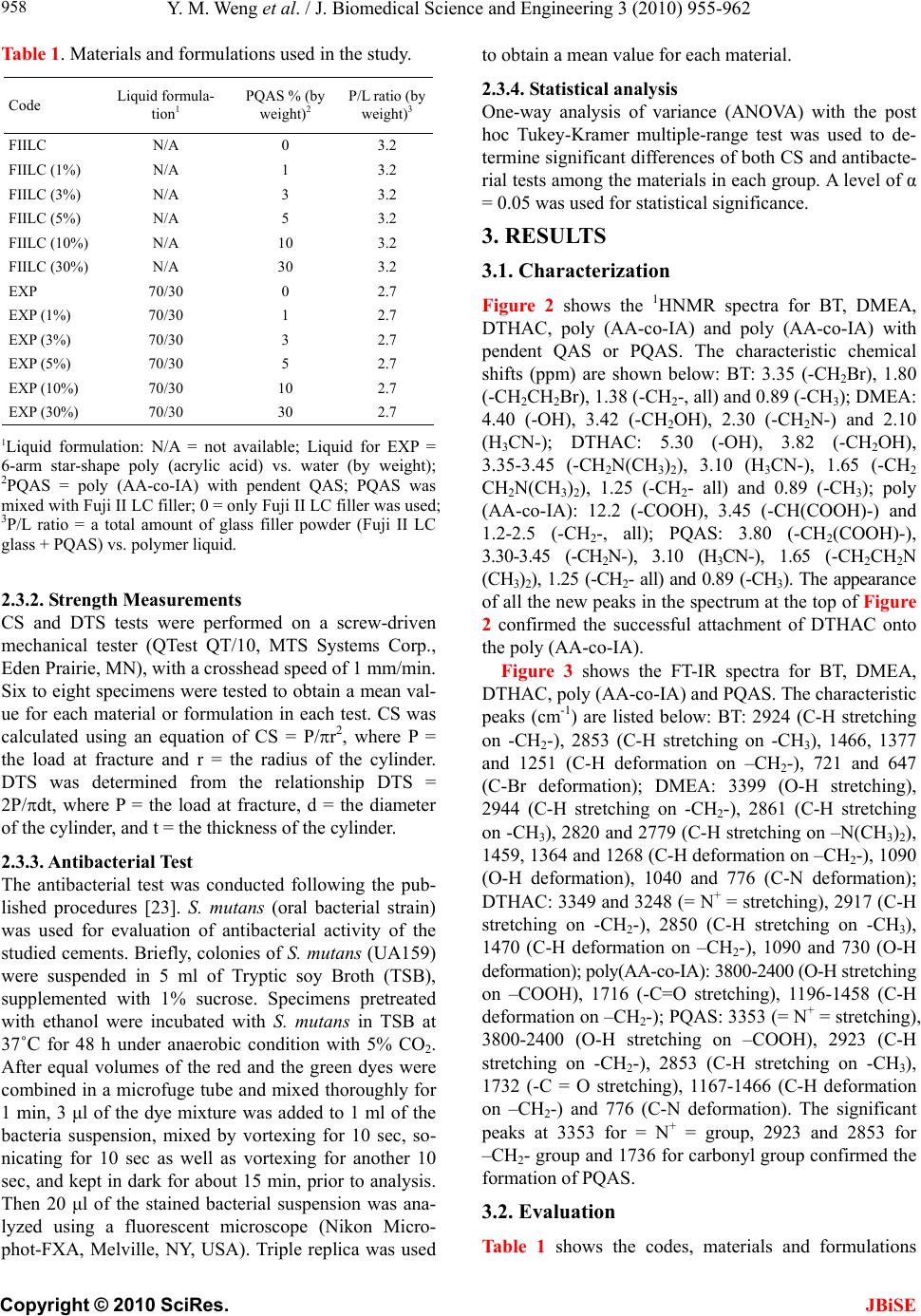

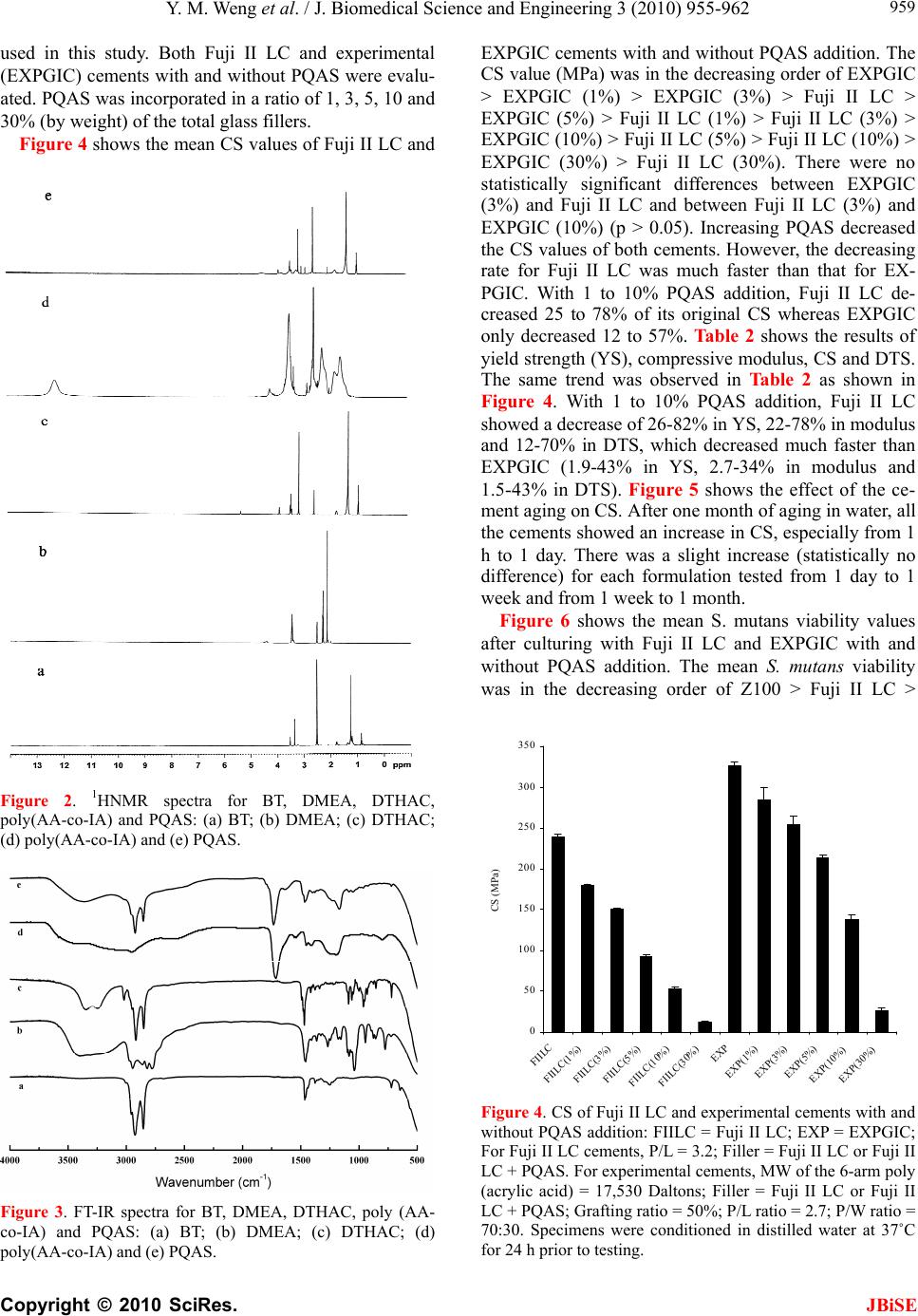

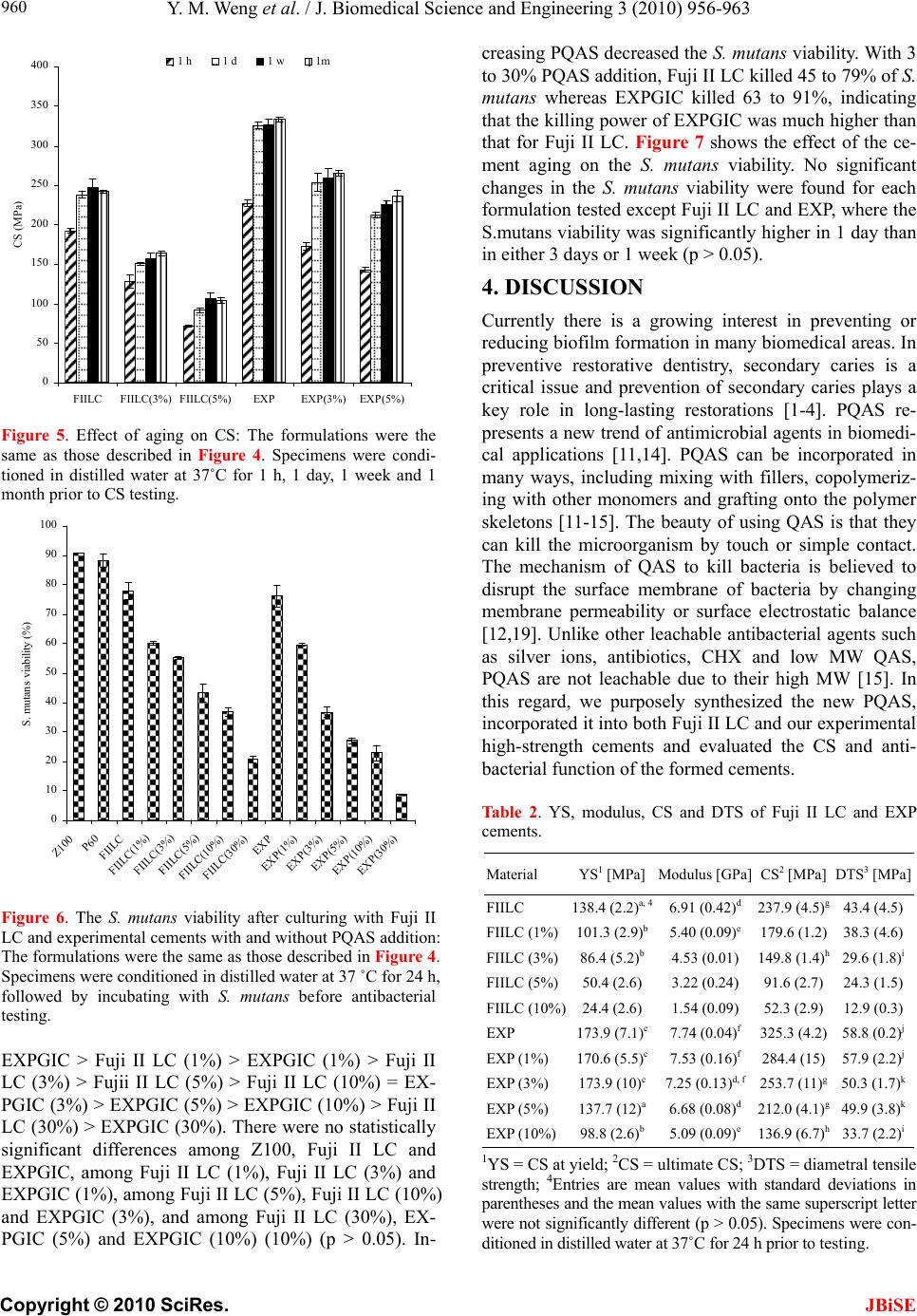

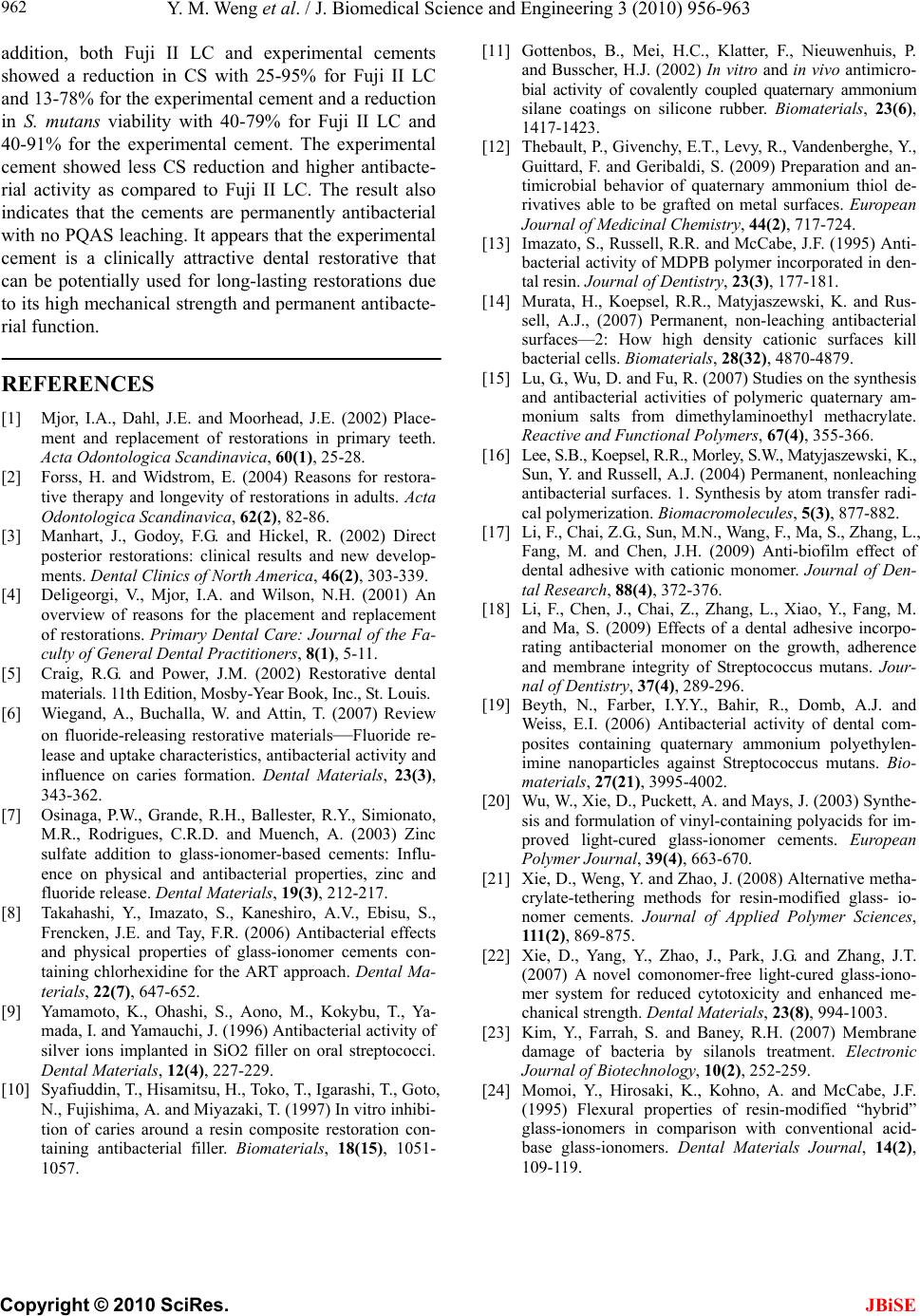

J. Biomedical Science and Engineering, 2010, 3, 955-962 JBiSE doi:10.4236/jbise.2010.310126 Published Online October 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jbise/). Published Online October 20 10 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbise A PQAS-containing glass-ionomer cement for improved antibacterial function Yiming Weng1, Xia Guo1, Jun Zhao1, Richard L. Gregory2, Dong Xie1* 1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue School of Engineering and Technology, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, USA; 2Department of Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, Indiana University, Indianapolis, USA. Email: dxie@iupui.edu Received 5 August 2010; revised 18 August 2010; accepted 26 August 2010. ABSTRACT The novel non-leachable poly (quaternary ammo- nium salt) (PQAS)-containing antibacterial glass- ionomer cement has been developed. Compressive strength (CS) and S. mutans viability were used as tools for strength and antibacterial activity evalua- tions, respectively. All the specimens were condi- tioned in distilled water at 37˚C prior to testing. Commercial glass-ionomer cement Fuji II LC was used as control. With PQAS addition, the studied cements showed a reduction in CS with 25-95% for Fuji II LC and 13-78% for the experimental cement and a reduction in S. mutans viability with 40-79% for Fuji II LC and 40-91% for the experimental cement. The experimental cement showed less CS reduction and higher antibacterial activity as com- pared to Fuji II LC. The long-term aging study in- dicates that the cements are permanently antibac- terial with no PQAS leaching. It appears that the experimental cement is a clinically attractive dental restorative that can be potentially used for long- lasting restorations due to its high mechanical s t r e n g t h and permanent antibacterial function. Keywords: PQAS; Antibacterial; Glass-Ionomer Cement; CS; Aging 1. INTRODUCTION In dental clinics, secondary caries is found to be the main reason to the restoration failure of either composite resins or glass-ionomer cements (GICs) [1-4]. Secondary caries that often occurs at the interface between the res- toration and the cavity preparation is mainly caused by demineralization of tooth structure due to invasion of plaque bacteria (acid-producing bacteria) such as Strep- tococcu mutans (S. mutans) in the presence of ferment- able carbohydrates [4]. Among all the dental restoratives, GICs are found to be the most cariostatic and somehow antibacterial due to release of fluoride, which is believed to help reduce demineralization, enhance remineraliza- tion and inhibit microbial growth [5,6]. However, annual clinical surveys found that secondary caries was still the main reason for GIC failure [1-4], indicating that the fluoride-release from GICs is not potent enough to in- hibit bacterial growth or combat bacterial destruction. Although numerous efforts have been made on improv- ing antibacterial activities of dental restoratives, most of them have been focused on release or slow-release of various incorporated low molecular weight (MW) anti- bacterial agents such as antibiotics, zinc ions, silver ions, iodine and chlorhexidine (CHX) [6-10]. However, re- lease or slow-release can lead or has led to reduction of mechanical properties of the restoratives over time, short-term effectiveness, and possible toxicity to sur- rounding tissues if the dose or release is not properly controlled [6-10]. Macromolecules containing quaternary ammonium (QAS) or phosphonium salt (QPS) groups have been studied extensively as an important antimicrobial mate- rial and used for a variety of applications due to their potent antimicrobial activities [11-15]. These polymers are found to be capable of killing bacteria that are resis- tant to other types of cationic antibacterials [16]. The examples of polyQAS or PQAS used as antibacterials for dental restoratives include incorporation of a metha- cryloyloxydodecyl pyridinium bromide (MDPB) as an antibacterial monomer into composite resins [13], use of DMAE-CB as a component for antibacterial bonding agents [17,18], and incorporation of quaternary ammo- nium polyethylenimine (PEI) nanoparticles into compos- ite resins [19]. All these studies found that PQAS did exhibit significant antibacterial activities. So far there have been no reports on using PQAS as an antibacterial  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 955-962 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 956 agent for GICs. The objective of this study was to synthesize a new poly (acrylic acid-co-itaconic acid) with pendent qua- ternary ammonium salt (PQAS) and explore the effects of this PQAS on mechanical strength and antibacterial activity of commercial Fuji II LC and recently developed experimental high-strength cements. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Materials 2-dimethylaminoethanol (DMAE), bromotetradecane (BT), dipentaerythritol, 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BIBB), acrylic acid (AA), itaconic acid (IA), 2,2’-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), triethylamine (TEA), CuBr, N, N, N’, N’, N’’ -pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA), dl-camphoroquinone (CQ), 2-(dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA), pyridine, tert-butyl acrylate (t-BA), glycidyl methacrylate (GM), hydrochlo- ric acid (HCl, 37%), N, N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), pyridine, diethyl ether, dioxane, N,N-dimethyl- formamide (DMF), methanol (MeOH), ethyl acetate (EA), hexane and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were used as received from VWR International Inc (Bristol, CT) without further purifications. Light-cured glass-ionomer cement Fuji II LC and Fuji II LC glass powders were used as received from GC America Inc (Alsip, IL). Z100 resin composite was used as received from 3M ESPE (St. Paul, MN). 2.2. Synthesis and Characterization 2.2.1. Synthesis of the Quaternary Ammonium Salt (QAS) The hydroxyl group-containing quaternary ammonium salt (QAS) was synthesized following the procedures described elsewhere with a slight modification [12]. Briefly, to a flask containing DMAE (0.056 mol) in me- thanol (100 ml), BT (0.062 mol) was added. The reac- tion was run at room temperature overnight. After most of methanol was removed, the mixture was washed with hexane 3 times. The formed 2-dimethyl-2-tetrade- canyl-1-hydroxyethyl ammonium bromide (DTHAB) was then dissolved in 10% HCl aqueous solution con- taining a small amount of MeOH. After the solution was stirred at 110˚C for 3 h, MeOH, HBr and water were removed via a rotary evaporator. The formed 2-dimethyl -2-tetradecanyl-1-hydroxyethyl ammonium chloride (DT HAC) was purified by washing with hexane several times before drying in a vacuum oven. The synthesis scheme is shown in Figure 1. 2.2.2. Synthesis of the Poly (Acrylic Acid-co-Itaconic acid) with Pendent QAS The linear poly (acrylic acid-co-itaconic acid) or poly (AA-co-IA) was prepared following our published pro- cedures [20]. Briefly, to a flask containing a solution of AA (0.08 mol) and IA (0.04 mol) in 40 ml THF, AIBN (0.5 mmol) in 10 ml THF was added. After the reaction was run under N2 purging at 60˚C for 18 h, poly (AA- co-IA) was precipitated with ether, followed by drying in a vacuum oven. Then DTHAC was tethered onto the purified poly (AA-co-IA) [21]. Briefly, to a solution of poly (AA-co-IA) in DMF, DTHAC was added with DCC and pyridine. The reaction was kept at room temperature overnight. After the insoluble dicyclohexyl urea was filtered off, the formed poly(AA-co-IA) with pendent QAS or PQAS was purified by precipitation from ether, washing with ether and drying in a vacuum oven prior to use (see Figure 1). 2.2.3. Synthesis of the GM-Tethered Star-Shape Poly (Acrylic Acid) The GM-tethered 6-arm star-shape poly (acrylic acid) (PAA) was synthesized similarly as described in our previous publication [22]. Briefly, dipentaerythritol (0.06 mol) in 200 ml THF was used to react with BIBB (0.48 mol) in the presence of TEA (0.35 mol) to form the 6-arm initiator. t-BA (0.078 mol) in 10 ml dioxane was then polymerized with the 6-arm initiator (1% by mole) at 120˚C in the presence of CuBr (3%)-PMDETA (3%) catalyst complex via ATRP. The resultant 6-arm poly (t-BA) was hydrolyzed with HCl and dialyzed against distilled water. The purified star-shape PAA was obtained via freeze-drying, followed by tethering with GM (50% by mole) in DMF in the presence of pyridine (1% by weight) [22]. The GM-tethered star-shape PAA was re- covered by precipitation from diethyl ether, followed by drying in a vacuum oven at room temperature. The syn- thesis scheme for the 6-arm star-shape PAA is also shown in Figure 1. 2.2.4. Characteri zation The chemical structures of the synthesized QAS and PQAS were characterized by Fourier transform-infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The proton NMR (1HNMR) spec- tra were obtained on a 500 MHz Bruker NMR spec- trometer (Bruker Avance II, Bruker BioSpin Corporation, Billerica, MA) using deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide and chloroform as solvents and FT-IR spectra were obtained on a FT-IR spectrometer (Mattson Research Series FT/ IR 1000, Madison, WI). 2.3. Evaluation 2.3.1. Sample Preparati on f or St rength Tests The experimental cements were formulated with a two-component system (liquid and powder) [22]. The liquid was formulated with the light-curable star-shape poly (acrylic acid), water, 0.9% CQ (photo-initiator, by  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 955-962 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 957 weight) and 1.8% DC (activator). The polymer/water (P/W) ratios (by weight) = 70:30. Fuji II LC glass pow- der was either used alone or mixed with the synthesized PQAS to formulate the cements, where the PQAS mix- ing ratio (by weight) = 1, 3, 5, 10, or 30% of the glass. The detailed formulations are shown in Ta b l e 1 . Fuji II LC and Z100 were used as controls and prepared per manufacturers’ instructions, where the P/L ratio = 3.2 for Fuji II LC and premixed paste for Z100. Specimens were fabricated at room temperature ac- cording to the published protocol [22]. Briefly, the cy- lindrical specimens were prepared in glass tubing with dimensions of 4 mm in diameter by 8 mm in length for compressive strength (CS), 4 mm in diameter by 2 mm in length for diametral tensile strength (DTS) and 4 mm in diameter by 2 mm in depth for antibacterial tests. All the specimens were exposed to blue light (EXAKT 520 Blue Light Polymerization Unit, EXAKT Technologies, Inc., Oklahoma City, OK) for 2 min, followed by condi- tioned in 100% humidity for 15 min, removed from the mold and conditioned in distilled water at 37˚C for 24 h unless specified, prior to testing. n m CH2CH CH2C COOH CH2 C COOH O O CH2CH2 N CH3 CH3 CH3(CH2)12CH2+ Cl- (1) 3-dimethylaminoethanol poly(AA-c o-IA)/DCC pyridine A. B. Where m = 7 and n = 3 Where x = y = 50 y x y x x y x y y x y x O O O O O O OO O O OO O CO2H Br OCH2CH O O OH H2OC Br H2OC O Br CO2H O CHCH2O O O Br OOCH2CH OO OH CO2H Br OOCH2CH CO2H O CHCH 2O O O OH Br O CHCH2O O O OH O OOH OH CH3(CH2)12CH2Br CH3(CH2)12CH2NCH2CH2OH CH3 CH3 + Cl- (2) HCl Figure 1. Schematic diagrams for synthesis of poly(AA-co-IA) with pendent QAS or PQAS and chemical structure of the 6-arm star-shape poly(acrylic acid) tethered with methacylate groups: (A): synthesis of PQAS; (B) chemical structure of the 6-arm star-shape poly(acrylic acid) tethered with polymerizable methacrylates.  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 955-962 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 958 Table 1. Materials and formulations used in the study. Code Liquid formula- tion1 PQAS % (by weight)2 P/L ratio (by weight)3 FIILC N/A 0 3.2 FIILC (1%) N/A 1 3.2 FIILC (3%) N/A 3 3.2 FIILC (5%) N/A 5 3.2 FIILC (10%) N/A 10 3.2 FIILC (30%) N/A 30 3.2 EXP 70/30 0 2.7 EXP (1%) 70/30 1 2.7 EXP (3%) 70/30 3 2.7 EXP (5%) 70/30 5 2.7 EXP (10%) 70/30 10 2.7 EXP (30%) 70/30 30 2.7 1Liquid formulation: N/A = not available; Liquid for EXP = 6-arm star-shape poly (acrylic acid) vs. water (by weight); 2PQAS = poly (AA-co-IA) with pendent QAS; PQAS was mixed with Fuji II LC filler; 0 = only Fuji II LC filler was used; 3P/L ratio = a total amount of glass filler powder (Fuji II LC glass + PQAS) vs. polymer liquid. 2.3.2. Strength Measuremen ts CS and DTS tests were performed on a screw-driven mechanical tester (QTest QT/10, MTS Systems Corp., Eden Prairie, MN), with a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. Six to eight specimens were tested to obtain a mean val- ue for each material or formulation in each test. CS was calculated using an equation of CS = P/r2, where P = the load at fracture and r = the radius of the cylinder. DTS was determined from the relationship DTS = 2P/dt, where P = the load at fracture, d = the diameter of the cylinder, and t = the thickness of the cylinder. 2.3.3. Antibacterial Test The antibacterial test was conducted following the pub- lished procedures [23]. S. mutans (oral bacterial strain) was used for evaluation of antibacterial activity of the studied cements. Briefly, colonies of S. mutans (UA159) were suspended in 5 ml of Tryptic soy Broth (TSB), supplemented with 1% sucrose. Specimens pretreated with ethanol were incubated with S. mutans in TSB at 37˚C for 48 h under anaerobic condition with 5% CO2. After equal volumes of the red and the green dyes were combined in a microfuge tube and mixed thoroughly for 1 min, 3 μl of the dye mixture was added to 1 ml of the bacteria suspension, mixed by vortexing for 10 sec, so- nicating for 10 sec as well as vortexing for another 10 sec, and kept in dark for about 15 min, prior to analysis. Then 20 μl of the stained bacterial suspension was ana- lyzed using a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Micro- phot-FXA, Melville, NY, USA). Triple replica was used to obtain a mean value for each material. 2.3.4. Statisti cal analysis One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Tukey-Kramer multiple-range test was used to de- termine significant differences of both CS and antibacte- rial tests among the materials in each group. A level of α = 0.05 was used for statistical significance. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Characterization Figure 2 shows the 1HNMR spectra for BT, DMEA, DTHAC, poly (AA-co-IA) and poly (AA-co-IA) with pendent QAS or PQAS. The characteristic chemical shifts (ppm) are shown below: BT: 3.35 (-CH2Br), 1.80 (-CH2CH2Br), 1.38 (-CH2-, all) and 0.89 (-CH3); DMEA: 4.40 (-OH), 3.42 (-CH2OH), 2.30 (-CH2N-) and 2.10 (H3CN-); DTHAC: 5.30 (-OH), 3.82 (-CH2OH), 3.35-3.45 (-CH2N(CH3)2), 3.10 (H3CN-), 1.65 (-CH2 CH2N(CH3)2), 1.25 (-CH2- all) and 0.89 (-CH3); poly (AA-co-IA): 12.2 (-COOH), 3.45 (-CH(COOH)-) and 1.2-2.5 (-CH2-, all); PQAS: 3.80 (-CH2(COOH)-), 3.30-3.45 (-CH2N-), 3.10 (H3CN-), 1.65 (-CH2CH2N (CH3)2), 1.25 (-CH2- all) and 0.89 (-CH3). The appearance of all the new peaks in the spectrum at the top of Figure 2 confirmed the successful attachment of DTHAC onto the poly (AA-co-IA). Figure 3 shows the FT-IR spectra for BT, DMEA, DTHAC, poly (AA-co-IA) and PQAS. The characteristic peaks (cm-1) are listed below: BT: 2924 (C-H stretching on -CH2-), 2853 (C-H stretching on -CH3), 1466, 1377 and 1251 (C-H deformation on –CH2-), 721 and 647 (C-Br deformation); DMEA: 3399 (O-H stretching), 2944 (C-H stretching on -CH2-), 2861 (C-H stretching on -CH3), 2820 and 2779 (C-H stretching on –N(CH3)2), 1459, 1364 and 1268 (C-H deformation on –CH2-), 1090 (O-H deformation), 1040 and 776 (C-N deformation); DTHAC: 3349 and 3248 (= N+ = stretching), 2917 (C-H stretching on -CH2-), 2850 (C-H stretching on -CH3), 1470 (C-H deformation on –CH2-), 1090 and 730 (O-H deformation); poly(AA-co-IA): 3800-2400 (O-H stretching on –COOH), 1716 (-C=O stretching), 1196-1458 (C-H deformation on –CH2-); PQAS: 3353 (= N+ = stretching), 3800-2400 (O-H stretching on –COOH), 2923 (C-H stretching on -CH2-), 2853 (C-H stretching on -CH3), 1732 (-C = O stretching), 1167-1466 (C-H deformation on –CH2-) and 776 (C-N deformation). The significant peaks at 3353 for = N+ = group, 2923 and 2853 for –CH2- group and 1736 for carbonyl group confirmed the formation of PQAS. 3.2. Evaluation Table 1 shows the codes, materials and formulations  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 955-962 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 959 used in this study. Both Fuji II LC and experimental (EXPGIC) cements with and without PQAS were evalu- ated. PQAS was incorporated in a ratio of 1, 3, 5, 10 and 30% (by weight) of the total glass fillers. Figure 4 shows the mean CS values of Fuji II LC and Figure 2. 1HNMR spectra for BT, DMEA, DTHAC, poly(AA-co-IA) and PQAS: (a) BT; (b) DMEA; (c) DTHAC; (d) poly(AA-co-IA) and (e) PQAS. Figure 3. FT-IR spectra for BT, DMEA, DTHAC, poly (AA- co-IA) and PQAS: (a) BT; (b) DMEA; (c) DTHAC; (d) poly(AA-co-IA) and (e) PQAS. EXPGIC cements with and without PQAS addition. The CS value (MPa) was in the decreasing order of EXPGIC > EXPGIC (1%) > EXPGIC (3%) > Fuji II LC > EXPGIC (5%) > Fuji II LC (1%) > Fuji II LC (3%) > EXPGIC (10%) > Fuji II LC (5%) > Fuji II LC (10%) > EXPGIC (30%) > Fuji II LC (30%). There were no statistically significant differences between EXPGIC (3%) and Fuji II LC and between Fuji II LC (3%) and EXPGIC (10%) (p > 0.05). Increasing PQAS decreased the CS values of both cements. However, the decreasing rate for Fuji II LC was much faster than that for EX- PGIC. With 1 to 10% PQAS addition, Fuji II LC de- creased 25 to 78% of its original CS whereas EXPGIC only decreased 12 to 57%. Ta bl e 2 shows the results of yield strength (YS), compressive modulus, CS and DTS. The same trend was observed in Table 2 as shown in Figure 4. With 1 to 10% PQAS addition, Fuji II LC showed a decrease of 26-82% in YS, 22-78% in modulus and 12-70% in DTS, which decreased much faster than EXPGIC (1.9-43% in YS, 2.7-34% in modulus and 1.5-43% in DTS). Figure 5 shows the effect of the ce- ment aging on CS. After one month of aging in water, all the cements showed an increase in CS, especially from 1 h to 1 day. There was a slight increase (statistically no difference) for each formulation tested from 1 day to 1 week and from 1 week to 1 month. Figure 6 shows the mean S. mutans viability values after culturing with Fuji II LC and EXPGIC with and without PQAS addition. The mean S. mutans viability was in the decreasing order of Z100 > Fuji II LC > 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 FIILC FIILC(1 %) FIILC(3%) FIILC(5%) FIILC(10%) FIILC(30%) EXP EXP(1%) EXP(3%) EXP(5%) EXP(10%) EXP(30%) CS (MPa) Figure 4. CS of Fuji II LC and experimental cements with and without PQAS addition: FIILC = Fuji II LC; EXP = EXPGIC; For Fuji II LC cements, P/L = 3.2; Filler = Fuji II LC or Fuji II LC + PQAS. For experimental cements, MW of the 6-arm poly (acrylic acid) = 17,530 Daltons; Filler = Fuji II LC or Fuji II LC + PQAS; Grafting ratio = 50%; P/L ratio = 2.7; P/W ratio = 70:30. Specimens were conditioned in distilled water at 37˚C for 24 h prior to testing.  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 956-963 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 960 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 FIILCFIILC(3%) FIILC(5%)EXPEXP(3%)EXP(5%) CS (MPa) 1 h1 d1 w1m Figure 5. Effect of aging on CS: The formulations were the same as those described in Figure 4. Specimens were condi- tioned in distilled water at 37˚C for 1 h, 1 day, 1 week and 1 month prior to CS testing. 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Z100 P60 FIILC FIILC(1%) FIILC(3%) FIILC(5%) FIILC(10%) FIILC(30%) EX P EXP(1%) EXP(3%) EXP(5%) EX P(10%) EX P(30%) S. mutans viability (%) Figure 6. The S. mutans viability after culturing with Fuji II LC and experimental cements with and without PQAS addition: The formulations were the same as those described in Figure 4. Specimens were conditioned in distilled water at 37 ˚C for 24 h, followed by incubating with S. mutans before antibacterial testing. EXPGIC > Fuji II LC (1%) > EXPGIC (1%) > Fuji II LC (3%) > Fujii II LC (5%) > Fuji II LC (10%) = EX- PGIC (3%) > EXPGIC (5%) > EXPGIC (10%) > Fuji II LC (30%) > EXPGIC (30%). There were no statistically significant differences among Z100, Fuji II LC and EXPGIC, among Fuji II LC (1%), Fuji II LC (3%) and EXPGIC (1%), among Fuji II LC (5%), Fuji II LC (10%) and EXPGIC (3%), and among Fuji II LC (30%), EX- PGIC (5%) and EXPGIC (10%) (10%) (p > 0.05). In- creasing PQAS decreased the S. mutans viability. With 3 to 30% PQAS addition, Fuji II LC killed 45 to 79% of S. mutans whereas EXPGIC killed 63 to 91%, indicating that the killing power of EXPGIC was much higher than that for Fuji II LC. Figure 7 shows the effect of the ce- ment aging on the S. mutans viability. No significant changes in the S. mutans viability were found for each formulation tested except Fuji II LC and EXP, where the S.mutans viability was significantly higher in 1 day than in either 3 days or 1 week (p > 0.05). 4. DISCUSSION Currently there is a growing interest in preventing or reducing biofilm formation in many biomedical areas. In preventive restorative dentistry, secondary caries is a critical issue and prevention of secondary caries plays a key role in long-lasting restorations [1-4]. PQAS re- presents a new trend of antimicrobial agents in biomedi- cal applications [11,14]. PQAS can be incorporated in many ways, including mixing with fillers, copolymeriz- ing with other monomers and grafting onto the polymer skeletons [11-15]. The beauty of using QAS is that they can kill the microorganism by touch or simple contact. The mechanism of QAS to kill bacteria is believed to disrupt the surface membrane of bacteria by changing membrane permeability or surface electrostatic balance [12,19]. Unlike other leachable antibacterial agents such as silver ions, antibiotics, CHX and low MW QAS, PQAS are not leachable due to their high MW [15]. In this regard, we purposely synthesized the new PQAS, incorporated it into both Fuji II LC and our experimental high-strength cements and evaluated the CS and anti- bacterial function of the formed cements. Table 2. YS, modulus, CS and DTS of Fuji II LC and EXP cements. Material YS1 [MPa] Modulus [GPa] CS2 [MPa] DTS3 [MPa] FIILC 138.4 (2.2)a, 46.91 (0.42)d 237.9 (4.5)g43.4 (4.5) FIILC (1%)101.3 (2.9)b5.40 (0.09)e 179.6 (1.2)38.3 (4.6) FIILC (3%)86.4 (5.2)b 4.53 (0.01) 149.8 (1.4)h29.6 (1.8)i FIILC (5%)50.4 (2.6) 3.22 (0.24) 91.6 (2.7) 24.3 (1.5) FIILC (10%)24.4 (2.6) 1.54 (0.09) 52.3 (2.9) 12.9 (0.3) EXP 173.9 (7.1)c7.74 (0.04)f 325.3 (4.2)58.8 (0.2)j EXP (1%) 170.6 (5.5)c7.53 (0.16)f 284.4 (15) 57.9 (2.2)j EXP (3%) 173.9 (10)c 7.25 (0.13)d, f 253.7 (11)g50.3 (1.7)k EXP (5%) 137.7 (12)a 6.68 (0.08)d 212.0 (4.1)g49.9 (3.8)k EXP (10%)98.8 (2.6)b 5.09 (0.09)e 136.9 (6.7)h33.7 (2.2)i 1YS = CS at yield; 2CS = ultimate CS; 3DTS = diametral tensile strength; 4Entries are mean values with standard deviations in parentheses and the mean values with the same superscript letter were not significantly different (p > 0.05). Specimens were con- ditioned in distilled water at 37˚C for 24 h prior to testing.  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 955-962 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 961 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 FIILC FIILC(5%) FIILC(10%) EXP EXP(5%) EXP(10%) S. mutans viability (%) 1 d3 d1 w1 m Figure 7. Effect of aging on the S. mutans viability after cul- turing with Fuji II LC and experimental cements with and without PQAS addition: The formulations were the same as those described in Figure 5. The specimens were conditioned in distilled water for 1 day, 3 days, 1 week and 1 month, fol- lowed by incubating with S. mutans before antibacterial testing. From the results in Figure 4 and Ta b l e 2 , apparently both Fuji II LC and EXPGIC cements showed a decrease in CS, YS, modulus and DTS with increasing PQAS. This can be attributed to the reason that the incorporated QAS contains a 14 carbon long chain that does not con- tribute to any strength enhancement. On the other hand, EXPGIC showed a slower decreasing pace with nearly 30% less in CS decrease as compared to Fuji II LC (see Figure 4). This result implies that there may be some strong intermolecular interactions between PQAS and star-shape polymers. Furthermore, EXPGIC still kept its CS above 200 MPa at PQAS = 5% or less, which may be attributed to its original high strength (325 MPa). Regarding the antibacterial activity, we also tested a commercial dental composite resin Z100 for comparison. We found that Z100 hardly killed S. mutans. After 48 h incubation with S. mutan s, Z100 only killed 10% S. mu- tans (see Figure 5). Composite resins usually do not have antibacterial functions [5,6]. Both Fuji II LC and EXPGIC cements without PQAS addition killed about 20% S. mutans, which can be attributed to the release of fluoride. It is known that GICs have inhibitory effects on bacteria due to its fluoride release [6]. With PQAS addi- tion, both Fuji II LC and EXPGIC increased their anti- bacterial function significantly. More interestingly, EXP GIC showed an even stronger antibacterial activity than Fuji II LC with 3 to 30% PQAS addition. The possible reason may be explained below. Since PQAS is com- posed of 50% carboxylic acid and 50% QAS and both components are very hydrophilic, they like to have in- teractions with other hydrophilic components from the cement in the presence of water. EXPGIC contains only hydrophilic GM-tethered poly (acrylic acid) (70%) and water (30%), whereas Fuji II LC contains a substantial amount (approximately 25-35%) of 2-hydroxyethyl me- thacrylate (partially hydrophilic) and dimethacrylaye/ oligomethacrylte (very hydrophobic), except for the linear poly (acrylic acid) (20-30%) and water (20-30%) [24]. Therefore, the components in EXPGIC may help the PQAS chains better extend on the surface of the cements but dimethacrylaye/oligomethacrylte and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate in Fuji II LC may restrict or interfere with the extension of the PQAS chains on the surface. Obvi- ously, the more the QAS exposed the higher the antibac- terial activity anticipated. The results imply that to reach the same or similar antibacterial results less PQAS might be required for EXPGIC than Fuji II LC. This outcome is very encouraging because it will allow us to use the minimum amount of PQAS in EXPGIC to obtain the maximum antibacterial activity without significantly reducing mechanical strengths. As previously discussed, most antibacterial dental materials rely on the release of chemicals or antibacterial agents including antibiotics, silver ions, zinc ions, etc [6-10]. However, release or slow-release can lead or has led to reduction of mechanical properties of the restora- tives over time, short-term effectiveness, and possible toxicity to surrounding tissues if the dose or release is not properly controlled [6-10]. Our hypothesis was to develop an antibacterial glass-ionomer cement without leachable. To confirm if the incorporated PQAS was not leachable, we examined both CS and antibacterial func- tion of EXPGIC (containing 5% PQAS) after aging in water for 1 day, 3 days, 1 week and 1 month. The result in Figure 5 showed that there was a slight increase in CS for all the formulations tested after one month of aging, indicating no PQAS leaching. The result in Fig- ure 7 showed that there was no change or reduction in antibacterial function for all the formulations tested, also suggesting no leaching. Otherwise, both strength and antibacterial function would decrease with aging. The reason can be attributed to the fact that the PQAS is the polyacid-containing polymer. It is known that the car- boxylic acid group is the key to GIC setting and salt-bridge formation. The PQAS polymer synthesized in the study not only provided QAS for antibacterial func- tion but also supplied carboxyl groups for salt-bridge formation. The latter helped the PQAS polymer firmly attached to the glass fillers. 5. CONCLUSIONS We have developed novel antibacterial glass-ionomer cement containing non-leachable PQAS. With PQAS  Y. M. Weng et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 956-963 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 962 addition, both Fuji II LC and experimental cements showed a reduction in CS with 25-95% for Fuji II LC and 13-78% for the experimental cement and a reduction in S. mutans viability with 40-79% for Fuji II LC and 40-91% for the experimental cement. The experimental cement showed less CS reduction and higher antibacte- rial activity as compared to Fuji II LC. The result also indicates that the cements are permanently antibacterial with no PQAS leaching. It appears that the experimental cement is a clinically attractive dental restorative that can be potentially used for long-lasting restorations due to its high mechanical strength and permanent antibacte- rial function. REFERENCES [1] Mjor, I.A., Dahl, J.E. and Moorhead, J.E. (2002) Place- ment and replacement of restorations in primary teeth. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 60(1), 25-28. [2] Forss, H. and Widstrom, E. (2004) Reasons for restora- tive therapy and longevity of restorations in adults. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 62(2), 82-86. [3] Manhart, J., Godoy, F.G. and Hickel, R. (2002) Direct posterior restorations: clinical results and new develop- ments. Dental Clinics of North America, 46(2), 303-339. [4] Deligeorgi, V., Mjor, I.A. and Wilson, N.H. (2001) An overview of reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations. Primary Dental Care: Journal of the Fa- culty of General Dental Practitioners, 8(1), 5-11. [5] Craig, R.G. and Power, J.M. (2002) Restorative dental materials. 11th Edition, Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St. Louis. [6] Wiegand, A., Buchalla, W. and Attin, T. (2007) Review on fluoride-releasing restorative materials—Fluoride re- lease and uptake characteristics, antibacterial activity and influence on caries formation. Dental Materials, 23(3), 343-362. [7] Osinaga, P.W., Grande, R.H., Ballester, R.Y., Simionato, M.R., Rodrigues, C.R.D. and Muench, A. (2003) Zinc sulfate addition to glass-ionomer-based cements: Influ- ence on physical and antibacterial properties, zinc and fluoride release. Dental Materials, 19(3), 212-217. [8] Takahashi, Y., Imazato, S., Kaneshiro, A.V., Ebisu, S., Frencken, J.E. and Tay, F.R. (2006) Antibacterial effects and physical properties of glass-ionomer cements con- taining chlorhexidine for the ART approach. Dental Ma- terials, 22(7), 647-652. [9] Yamamoto, K., Ohashi, S., Aono, M., Kokybu, T., Ya- mada, I. and Yamauchi, J. (1996) Antibacterial activity of silver ions implanted in SiO2 filler on oral streptococci. Dental Materials, 12(4), 227-229. [10] Syafiuddin, T., Hisamitsu, H., Toko, T., Igarashi, T., Goto, N., Fujishima, A. and Miyazaki, T. (1997) In vitro inhibi- tion of caries around a resin composite restoration con- taining antibacterial filler. Biomaterials, 18(15), 1051- 1057. [11] Gottenbos, B., Mei, H.C., Klatter, F., Nieuwenhuis, P. and Busscher, H.J. (2002) In vitro and in vivo antimicro- bial activity of covalently coupled quaternary ammonium silane coatings on silicone rubber. Biomaterials, 23(6), 1417-1423. [12] Thebault, P., Givenchy, E.T., Levy, R., Vandenberghe, Y., Guittard, F. and Geribaldi, S. (2009) Preparation and an- timicrobial behavior of quaternary ammonium thiol de- rivatives able to be grafted on metal surfaces. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 44(2), 717-724. [13] Imazato, S., Russell, R.R. and McCabe, J.F. (1995) Anti- bacterial activity of MDPB polymer incorporated in den- tal resin. Journal of Dentistry, 23(3), 177-181. [14] Murata, H., Koepsel, R.R., Matyjaszewski, K. and Rus- sell, A.J., (2007) Permanent, non-leaching antibacterial surfaces—2: How high density cationic surfaces kill bacterial cells. Biomaterials, 28(32), 4870-4879. [15] Lu, G., Wu, D. and Fu, R. (2007) Studies on the synthesis and antibacterial activities of polymeric quaternary am- monium salts from dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate. Reactive and Functional Polymers, 67(4), 355-366. [16] Lee, S.B., Koepsel, R.R., Morley, S.W., Matyjaszewski, K., Sun, Y. and Russell, A.J. (2004) Permanent, nonleaching antibacterial surfaces. 1. Synthesis by atom transfer radi- cal polymerization. Biomacromolecules, 5(3), 877-882. [17] Li, F., Chai, Z.G., Sun, M.N., Wang, F., Ma, S., Zhang, L., Fang, M. and Chen, J.H. (2009) Anti-biofilm effect of dental adhesive with cationic monomer. Journal of Den- tal Research, 88(4), 372-376. [18] Li, F., Chen, J., Chai, Z., Zhang, L., Xiao, Y., Fang, M. and Ma, S. (2009) Effects of a dental adhesive incorpo- rating antibacterial monomer on the growth, adherence and membrane integrity of Streptococcus mutans. Jour- nal of Dentistry, 37(4), 289-296. [19] Beyth, N., Farber, I.Y.Y., Bahir, R., Domb, A.J. and Weiss, E.I. (2006) Antibacterial activity of dental com- posites containing quaternary ammonium polyethylen- imine nanoparticles against Streptococcus mutans. Bio- materials, 27(21), 3995-4002. [20] Wu, W., Xie, D., Puckett, A. and Mays, J. (2003) Synthe- sis and formulation of vinyl-containing polyacids for im- proved light-cured glass-ionomer cements. European Polymer Journal, 39(4), 663-670. [21] Xie, D., Weng, Y. and Zhao, J. (2008) Alternative metha- crylate-tethering methods for resin-modified glass- io- nomer cements. Journal of Applied Polymer Sciences, 111 (2), 869-875. [22] Xie, D., Yang, Y., Zhao, J., Park, J.G. and Zhang, J.T. (2007) A novel comonomer-free light-cured glass-iono- mer system for reduced cytotoxicity and enhanced me- chanical strength. Dental Material s, 23(8), 994-1003. [23] Kim, Y., Farrah, S. and Baney, R.H. (2007) Membrane damage of bacteria by silanols treatment. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 10(2), 252-259. [24] Momoi, Y., Hirosaki, K., Kohno, A. and McCabe, J.F. (1995) Flexural properties of resin-modified “hybrid” glass-ionomers in comparison with conventional acid- base glass-ionomers. Dental Materials Journal, 14(2), 109-119. |