Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 54-60 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2013.31007 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 54 The Views of Spanish Undergraduates on Gender Equality, Parental Responsibilities and Joint-Custody Francisca Fariña1, Ramon Arce2, María José Vázquez1, Mercedes Novo2, Dolores Seijo2 1Department of Psycho-Socio-Educational Analysis and Intervention, University of Vigo, Vigo, Spain 2Department of Social Psychology, University of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain Email: francisca@uvigo.es Received November 17th, 2012; revised December 20th, 2012; accepted January 5th, 2013 In recent years we have witnessed concerted efforts to achieve real equality between men and women through legislative reform in the European Union (i.e., EU Directives 2002/73/EC; 76/207/EEC), and na- tionwide in Spain (e.g., Law 3/2007, of 22 March, for Effective Gender Equality) as well as regional leg- islation (e.g., Law 7/2004, 16 July, Galician Law for the Equality of Women and Men). In view of the principle of equal rights enshrined in legislative reform, one would expect social change entailing the re- moval of existing inequalities on the grounds of sex. In order to explore the views of Spanish youth re- garding gender equality, a pioneering field study was carried out to assess their knowledge of current leg- islation, and to examine their views towards gender equality, particularly in relation to specific issues such as family, divorce, separation, joint-custody, sexual relationships, education, and employment. More- over, perceived or real models of equality were contrasted with ideal or desired models of equality. Thus, a total of 2071 Spanish undergraduates were administered an ad hoc questionnaire. The results reveal the vast majority of undergraduates favoured gender equality, and the equal participation of women and men in family and working life as well as joint-custody in cases of divorce or separation. Nevertheless, differ- ences in gender were observed i.e., more women supported policies promoting the principle of equality than men. The findings underscore the need for implementing intervention strategies designed to foster shared responsibility and address different forms of discrimination based on sex in the family and the workplace and to combat them. Keywords: Spanish Undergraduates; Gender Equality; Joint-Custody; Shared Parenting The Principle of Gender Equality The principle of equality between men and women is en- shrined in a wide array of international treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Adopted by the UN General Assembly in De- cember 1979, and ratified by Spain in 1983; the Nairobi Con- ference, 1985; and the Beijing Declaration, 1995. Likewise, the European Union has adopted a range of measures outlined in the Treaty of Rome, and several recommendations and direc- tives promoting the principle of equality such as Directive 2002/73/CE, Directive 76/207/EEC on equal rights regarding access to employment and vocational training, and Directive 2004/113/CE, implementing the principle of equal treatment between men and women in the access to and supply of goods and services. In Spain, Article 14 of the Constitution declares the right to equality and protects citizens against any form of discrimination, as does Article 9.2 requiring public institutions and government agencies to promote equality in political, eco- nomic, cultural, and social life. Similarly, Law 3/2007, 22 March, implements the Effective Equality between Women and Men in all spheres of society by endorsing protection against discrimination, and enforcing policies promoting equality. By passing this law, Spain, provides legal and constitutional safe- guards guaranteeing the representation of women in public institutions. A further decisive step to combat inequality in Spain is Law 1/2004, de 28 December, on Integrated Protection Measures Against Gender-based Violence that acknowledges that any form of violence exercised against women constitutes a violation of their human rights. Thus Art 1 states that the pur- pose of this Act is to combat the violence exercised against wo- men by their present or former spouses or by men with whom they maintain or have maintained analogous affective relations, with or without cohabitation, as an expression of discrimination, inequality, and the power relations prevailing between the sexes. In 2008, the Spanish Government set up the Ministry of Equal- ity to enforce the laws and policies on equality and the previ- ously mentioned Law Against Gender-based Violence. The role of the Local Authorities and Autonomous Communities in pro- moting equality in recent years is also worthy of mention. In the Autonomous Community of Galicia, Law 7/2004, 16 July, for the Equality of Men and Women provides a legal framework that strives to ensure equality between women and men. Chap- ter II seeks to mainstream gender equality in all spheres of life be it political, social, cultural or artistic. The impact of legislative reform on education and employ- ment (see Spanish Ministry of Equality, 2009), cannot be fully understood without taking into account the accompanying transformation in family structures and parental roles. Gender Equality and the Family Relationships of equality within the family are good indica- tors of social change (Meil, 2006). As for views among the young regarding the family, the recent Youth and Gender  F. FARIÑA ET AL. Equality survey (INJUVE) found that many young people (46%) acknowledged there were difficulties in overcoming gender inequality in the family (López et al., 2008). Most youngsters (60%) mentioned the need to remove existing inequalities at work and in the family, and viewed the ideal family in which both parents work as being based on shared parental responsi- bility in housekeeping and child rearing (CIS, 2007). The ten- dency to consider shared parenting as the ideal family model has steadily increased from 47.7% in the 90s to the current figure of 60% (Navarro, 2006). In reconciling work and family life, some authors have suggested that changing gender roles and legal reform on gender equality have brought about greater parental responsibility for men. Thus, Alberdi and Escario (2007) have drawn attention to the increasing commitment of men in shared parenting and child rearing which contrasts with their own family upbringing. Recommendation 19 (2006) of the Committee of Ministers to Member States of the Council of Eu- rope on policy to support positive parenting strives to elimi- nate obstacles to positive parenting and to reconcile family and working life. With reference to family breakdown, Spain is the EU-27 country with the highest increase in quantitative and qualitative terms of divorce in the last 10 years, and represents 69% of the increase in the EU-15, and 58% of the total of the EU-27 (In- stitute of Family Policy, 2010). Spain registered a total of 110,561 divorces in 2011, an increase of 0.3% with respect to the previous year (INE, 2012). The figures underscore the need for addressing the issue of joint-custody outlined in Law 15/ 2005, 8 July, that amends the Civil Code and the Code of Civil Procedure on matters of separation and divorce, and expounds shared parenting and joint-custody (Bauserman, 2012; Lathrop, 2009). Divorce, Equality and Joint-Custody The Spanish national legislation concerning joint-custody is complemented by regulations and laws pertaining to each au- tonomous community that enforce the principle of equality be- tween men and women. Thus, in the Autonomous Community of Aragón, the preamble of the Law of Equality of Family Re- lationships in situations of Family Breakdown, 2010, declares that social change demands legislative reform regulating child custody to ensure the continued contact of children with both parents and the equality of both parents. Moreover, the law states that joint-custody is to be understood as a progressive system designed to foster shared parenting in the exercise of parental authority on the grounds of gender equality in all spheres of life, to enhance the professional development of wo- men, and to address the demand of men for a greater role in child rearing, a right which has traditionally been the exclusive domain of women. Thus, this law on joint-custody aims to con- tribute to the equality of gender roles, which still has a long road ahead. Similarly, the Autonomous Community Cataluña seeks to foster joint-custody as the preferred option of choice with Law 25/2010, 29 July, that amends the Second Book of the Civil Code of Cataluña regarding the family. The preamble of the said law mentions two innovative proposals regarding parental rights and obligations in circumstances of separation or divorce. The first is that all proposals by either party are subject to a judicial process to establish a parenting plan, which is an instrument designed to specify the parental rights and responsi- bilities concerning the child’s wellbeing, rearing, and education. Secondly, the traditional scenario of child separation from one parent in cases of family breakdown is rejected in favour of joint-custody whereby both parents retain equal or equivalent rights and obligations to ensure that above all the rights and wellbeing of children prevail in all circumstances. The under- lying current of thought is that shared parenting and joint-cus- tody serve the best interests of children by fostering stable rela- tionships with both parents. In addition, the granting of equal parental rights and obligations dispels lingering feeling of win- ners and losers, enhances affective ties and mutual collabora- tion to achieve common educational and economic goals. Hence, Article 233-8 reminds litigating couples that the judicial proc- ess of divorce or separation does not alter or relieve couples from the parental rights and duties described in Article 236- 17.1. Thus, current Spanish legislation takes a pro-active ap- proach to promoting joint-custody as well as equal rights, re- sponsibilities, and parental roles (Coloma, 2011). Furthermore, the literature has reported a plethora of benefits for children living under joint-custody as opposed to those liv- ing the sole-custody of one parent, in particular, the former tend to maintain stable relationships with both parents (Bauserman, 2012; Luepnitz, 1982; Welsh-Osga, 1981), better family rela- tions, ongoing and long-lasting contact with both parents (Bau- serman, 2012; Luepnitz, 1980, 1982; Welsh-Osga, 1981), and are better adjusted than sole-custody children (Buchanan, Mac- coby, & Dornbusch, 1996; Shiller, 1984, 1986), regardless of the degree of previous conflict (Gunnoe & Braver, 2001). In terms of coparenting following divorce or separation, children are better adjusted when both parents maintain a positive rela- tionship and are actively engaged in the child’s upbringing (Amato & Gilbreth, 1999; Lamb, 2002), are more motivated at school (Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1996), and achieve higher academic performance (Bauserman, 2002; Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1991). The benefits of joint-custody are not limited to children only, parent also stand to gain from better child-parent relationships (Bauserman, 2012; Welsh-Os- ga, 1981), greater personal satisfaction (Bredefeld, 1985); and in the long-term averts deteriorating parent-child relationships and reduces conflict (Bauserman, 2012; Pearson & Thoennes, 1990; Yarnoz, 2010). Mothers in joint-custody arrangements have better mental health, greater ability at solving mother- child disputes, receive more social support, and feel less bur- dened and stressed versus sole-custody mothers (Bauserman, 2012; Hanson & Boxett, 1985). In contrast, joint-custody fosters cooperation between both parents (Patrician, 1984); the equal sharing of rights and obli- gations (Bauserman, 2002; Fariña, 2010; Ortuño, 2006), and minimizes the judicialization of parenting (Bauserman, 2012). Notwithstanding, the rulings of the courts in child custody disputes appear to be impervious to recent research findings and guidelines advocating the joint-custody and shared parent- ing of children. The few case studies undertaken in Spain re- vealed the courts continue to grant sole-custody to one parent i.e., a review of 287 court rulings in child custody litigation revealed no joint-custody plans were granted by the courts, and in 91% of cases the mother was granted sole-custody (Catalán et al., 2008). Likewise, a case study of 498 court rulings under Law 15/2005, found joint-custody was granted in only 1.8% of cases of family breakdown (Alonso, 2011). The figures suggest that legislative reform has had little impact on child custody rulings, and traditional views of the mother as the “primary caretaker” of a child remain dominant and unchallenged. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 55  F. FARIÑA ET AL. Bearing in mind recent legislative reform in Spain concern- ing child custody, parenting, and gender equality as well as the findings and guidelines of current research, the aim of this study was threefold: to assess the knowledge of Spanish under- graduates regarding current Spanish legislation; to explore their views towards gender equality, particularly in relation to spe- cific issues such as family, divorce, separation, joint-custody custody, sex, education, and employment; and to gauge the dis- crepancies between perceived levels of equality and ideal levels equality. Method Participants The sample consisted of a random selection of 2071 Spanish undergraduates. The sample reflected the current gender distri- bution of the Spanish undergraduate population i.e., 72.7% wo- men and 27.3% men, aged 18 to 30 years (M = 20.57) (Sx = 2.66). Measures In order to explore their views, undergraduates were admin- istered an ad hoc questionnaire consisting of 24 items with a yes/no response format allocated to three broad categories: 1) Knowledge of the law. Consisting of 3 items designed to assess the participant’s knowledge of the law on gender equal- ity and child protection i.e., Law 3/2007 on Effective Gender Equality, Law 1/2004 for Integrated Protection Measures agai nst Gender Violence, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. 2) Views regarding gender equality. Consisting of 12 items designed to examine discrepancies between perceived equality and ideal models of equality as well as to contrast the rights and obligations women and men in different spheres of life e.g., education, work, sexual relationships, and family). 3) Views regarding gender equality in relation to separation and divorce. Consisting of 9 items designed to explore views regarding joint-custody, and maternal and paternal roles and responsibilities following separation or divorce. Procedure The questionnaire was administered at 5 Spanish universities selected at random by trained and experienced researches dur- ing the 2010-2011 academic year. All of the undergraduates freely volunteered to participate in the study, were informed of the aims of the study, and assured their data would remain anonymous and confidential. Data Analysis Data analysis was undertaken using the SPSS Version 19 statistical software package. The responses to the items on the questionnaire were used to generate the descriptive statistics, and to form contingency tables, chi-square and independent test in repeated measures. Results Knowledge of the Law With reference to knowledge of the law, 50.6% (n = 1045) of subjects stated they were unacquainted with the laws mentioned in the questionnaire, 36.5% were acquainted with at least one law, and 12.9% (n = 266) were acquainted with all of the laws. As shown in Graph 1, women were more acquainted with the current legislation than men, χ2(2, N = 1983) = 11.81, p < .05. Views Regarding Gender Equality 1) Rights and Obligations Though 96.8% (n = 2049) of respondents favoured equal rights for both men and women, more women as opposed to men demanded more rights, χ2(1, N = 1983) = 16.76, p < .01, ϕ = −.094. As for obligations, 95.9% (n = 1960) of subjects fa- voured equal obligations for men and women, but once again more women in contrast to men demanded equal obligations for both genders, χ2(1, N = 1960) = 12.44, p < .01, ϕ = −.081. In terms of concordance, it should be noted that 97.4% (n = 2043) of subjects favoured equal rights and obligations for both men and women, χ2(1, N = 2047) = 334.35, p < .01, ϕ = .41, and non-concordant responses were found according to gender. 2) Views of equality in specific spheres of life Graph 2 shows 80% (n = 1668) of subjects thought there were equal rights in education, 31.4% (n = 650) in sexual rela- tionships, 21.2% (n = 439) in the family, and 10.8% at work (n = 224). According to gender, significant differences were observed between men and women in relation to equality in the family, χ2(1, N = 2062) = 12.36, p < .01, ϕ = .078; sexual relationships, χ2(1, N = 2049) = 6.04, p < .01, ϕ = .054; and work, χ2(1, N = 2065) = 12.95, p < .01, ϕ = .79; with the exception of education, χ2 (1, n = 2059) = .82, ns. In comparison to men, women per- ceived greater levels of gender equality in all spheres of life. 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% Noknowl e dg e oflaw Knowledgeofone law Knowle dgeoftwo laws Kno w ledge ofthree laws 56.7% 19.9% 12.2% 11.2% 48.3% 24.0% 14.2% 13.5% Male Female Graph 1. Knowledge of legislation according to gender. 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% WorkFamilySexual r elationships Education 10.8% 21.2% 31.4% 80% Graph 2. Perceived real equality according to different spheres of life. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 56  F. FARIÑA ET AL. With regards to the ideal family, 98.2% of subjects (n = 2049), stated men and women should have equal rights, a view that was also held for other spheres of life (see Graph 3). However, significant differences were observed according to gender i.e., family, χ2(1, N = 2060) = 156.80, p < .01, ϕ = .27; sexual relationships, χ2(1, N = 2049) = 140.99, p < .01, ϕ = .26; education, χ2(1, N = 2059) = 14.28, p < .01, ϕ = .08; and work, χ2(1, N = 2065) = 106.78, p < .01, ϕ = .22 (see Graph 4). A similar pattern was observed for perceptions of real equality with female undergraduates underscoring the need for greater equality in all contexts. As for the assessment of the degree of concordance between perceptions of real equality and ideal levels of equality, the results reveal significant differences between both, χ2(1, N = 2062) = 26.24, p < .01, ϕ = −.12. Moreover, nonconcordant responses were observed in each sphere of life under study (see Table 1) i.e., nonconcordant perceptions of real equality and perceptions of ideal equality in the family and at work. 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% WorkFamily Sexual relationships Education 98.6% 98.2%97.2% 98.5% Graph 3. Views on ideal levels of equality according to different spheres of life. 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% WorkFamily Sexualrelationships Education 26.8% 27.2% 27.0% 26.8% 73.2% 72.8% 73.0% 73.2% Male Female Graph 4. Ideal levels of equality according to gender. Table 1. Perceptions of equality in specific spheres of life. McNemar Sphere of life χ2 p χ2 p Work 29.99 .001 1797.24 .001 Education .78 .379 363.57 .001 Sexual relationships .22 .636 1337.45 .001 Family 4.77 .005 1573.27 .001 3) Views on equality in reconciling work and family life Only a small number of respondents, 13.6% (n = 279), per- ceived real equality of rights in reconciling work and family life (see Table 2). As shown in Graph 5, of these respondents 54.1% were men (n = 151) and 45.8%, were women (n = 128), with a significant difference between genders, χ2(1, N = 2055) = 116.02, p < .01, ϕ = .24. As for ideal situations of equality, 98.7% of subjects favoured equal rights in reconciling work and family life; however, significant differences were found ac- cording to gender, χ2(1, N = 2056) =12.51, p < .01, ϕ = .08. Graph 5 shows women (n = 1484) were more in favour of equality in reconciling work and family life (73.1%), than men (n = 545) 26.9%. Views on Equality of Parental Roles and Child Care Following Separation or Divorce In cases of family breakdown (see Table 3), 92.7% (n = 1889) respondents identified the mother with the primary role of care and upbringing of children, χ2(1, N = 2037) = 50.80, p < .01, ϕ = −.16, of these 74.7% were women (n = 1412) and 25.3% men (n = 477). This percentage, however, fell to 67.7% (n = 1387) when respondents were asked about the ideal situa- tion i.e., if women should be primarily responsible for the care 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% Thereareequalrights Thereshouldbeequalri g h ts 54.1% 26.9% 45.8% 73.1% Male Fem ale Graph 5. Perceptions of equality in reconciling work and family life according to gender. Table 2. Real and ideal perceptions of equality in reconciling work and family life. Yes (%) No (%) Real equality* 13.6 86.4 Ideal equality** 98.7 1.3 Note: *Men and women have equal rights; **Men and women should have equal rights. Table 3. Real and ideal perceptions of equality in the care and upbringing of children by the father and mother following separation or divorce. Yes (%) No (%) Mother 92.7 73 Is responsible for the care and upbringing of the childFather 54.6 45.4 Mother 67.7 32.3 Should be responsible for the care and upbringing of the child Father 86.3 13.7 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 57  F. FARIÑA ET AL. and upbringing of children, χ2(1, N = 2048) = 71.52, p < .01, ϕ = −.18, of these 78.4% were women (n = 1088) and 21.6% (n = 299). As for the role of the father, 54.6% (n = 1099) of subjects thought the father was the primary carer of children χ2(1, N = 2013) = 2.95, ns, of these 71% were women (n = 780), and 29% men (n = 319) (see Graph 6). In terms of the ideal situation (Graph 7), 86.3% (n = 1768) of subjects thought the father should be the primary carer of children, 74.9% of these respondents were women (n = 1325) and 25.1% men (n = 443), revealing a marked difference be- tween both genders, χ2(1, N = 2049) = 32.73, p < .01, ϕ = −.12. 1) Joint-custody Graph 8 shows 97.2% (n = 2002) of respondents were in favour of joint-custody, of which 73.2% were women (n = 1465), and 26.8% men (n = 537) as illustrated in Graph 9. Differences were found according to gender, χ2(1, N = 2061) = 12.52, p < .01; ϕ = .07). Subjects in favour of joint-custody also believed it fostered gender equality, χ2(1, N = 2027) = 155.64, p < .01, ϕ = .27). However, nonconcordant responses were found, χ2(1, N = 2027) = 80.52, p < .01. Joint-custody (see Graph 10) was understood as a right of parents and children (77.3%) (n = 1552), whereas 15.5% (n = 312) defined it as a right of both parents, and a right of the child 6.8% (n = 137). Other responses obtained residual percentages. In terms of gender, of the 77.3% who thought joint-custody was a right of parents and children, 76.9% were women (n = 1190), and 23.1% men (n = 357); of the 15.5% who defined it as a right of both parents, 60.9% were women (n = 190), and 39.1% men (n = 122), and of the remaining 6.8% who defined it as a 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% Motherisresponsibleforthecare Fatherisres pon si bleforth e care 25.3% 29% 74.7% 71% Male Fema l e Graph 6. Perceptions of real equality in the care and upbringing of children by the father and mother following separation or divorce according to gen- der. 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% Mothe rshouldberespons ib lefor childcare Fathersh oul dberesp onsi bl e for chi l d care 21.6% 25.1% 78.4% 74.9% Male Fe male Graph 7. Perceptions of ideal equality in the care and upbringing of children by the father and mother following separation or divorce according to gen- der. 97.2% 2.8% Yes No Graph 8. Agree with joint-custody following separation or divorce. 26.8% 73.2% Male Female Graph 9. Agree with joint-custody following separation or divorce ac- cording to gender. 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% Parentsandchildren ParentsChildren 77.3% 15.5% 6.8% Graph 10. Joint-custody is a right of… right of the child, 58.4% were women (n = 80), and 41.6% men (n = 57). Discussion Bearing in mind the limitations of this study in relation to sample size, and consequently the ability to draw generaliza- tions to other populations we may consider the following con- clusions: 1) As regards the understanding of the law relating to child protection and gender equality, more than 50% of undergradu- ates were unfamiliar with the current legislation. The results underscore the need for raising social awareness and sensitivity (European Commission of Member States, 2009), thus it is vital that this initiative should be conceived and implemented in terms of a rights-responsibility dichotomy. Strikingly, most un- dergraduates, even those undertaking teacher-training, were un- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 58  F. FARIÑA ET AL. acquainted with basic legislation on child protection such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This highlights the need for tackling these issues in cross curricula topics at higher edu- cation (Aneca, 2011). Though 97.4% of subjects supported equal rights and obliga- tions, the findings of this study show that sexual inequality re- mains widespread in the family and work, underlining the need for intervention programmes in these areas of life. The concor- dance between real versus ideal perceptions of equality in the family and at work was low, which corroborated the findings of previous surveys (e.g., CIS, 2007; López et al., 2008). Accord- ing to the Global Report on Gender Inequality, 2012 (Haus- mann, Tyson, & Zahidi, 2012), Spain has lost headway in its efforts to achieve gender equality in reconciling work and fam- ily life. 2) As for family-breakdown, most undergraduates viewed women as the primary child career and the linchpin of emo- tional support though this was not considered to be the ideal scenario. Thus, parental responsibilities continue to be a source of inequality in situations of family-breakdown. Nevertheless, joint custody was the preferred option by the vast majority (97.2%) of respondents. As previously mentioned, in Spain few studies have been undertaken on views towards joint custody; nevertheless, our results have corroborated the findings of other studies such as the SOS PAPA (2005) in collaboration with Gallup Spain, a survey undertaken on a sample of 964 Spanish adults showing 83.6% favoured joint custody in cases of di- vorce even in cases involving child dispute litigation. A greater number of women 86.6% than men 80.5% were in favour of joint custody even in cases of child custody disputes. The results of this study reveal two prevailing social tenden- cies towards joint custody i.e., it is primarily conceived of as a right of parents and children, and as crucial step towards equa- lity between men and women (Bauserman, 2002, 2012; Fariña, 2010). 3) In terms of gender, female undergraduates had a better understanding of the law, supported more equal rights and ob- ligations, and demanded more rights to reconcile work and family life. Moreover, they favoured shared custody on the grounds that it is a right of parents and children. These demands should be addressed in the design and implementation of pro- grammes and policies on gender equality. Accordingly, the re- port of the European Commission of Member States (2009): policies on reconciling work and family should be focused on men given that promoting gender equality entails social change and fresh opportunities for both sexes. Hence, efforts must be undertaken to promote equality be- tween men and women by fostering shared parenting and the empowerment of women (Zimmerman, 2000). Legislative re- form enables legal equality, but it must to be accompanied by real change in all spheres of life, particularly in reconciling work and family life, to achieve real equality. REFERENCES Alberdi, I., & Escario, P. (2007). Young men and paternity. Madrid: Fundación BBVA. Alonso, M. (2011). The implications of Law 15/2005 on jurisprudence concerning care and custody: An archive study. Unpublished Ma- ster’s Thesis. Santiago de Compostela: University of Santiago de Com- postela. Amato, P., & Gilbreth, J. (1999). Nonresident father and children’s well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 557-573. doi:10.2307/353560 Aneca (2011). Guidebook for designing projects to verify official uni- versity degrees (Bachelors and Masters). http://www.aneca.es/Programas/VERIFICA/Protocolos-de-evaluacio n-y-documentos-de-ayuda/ Bauserman, R. (2002). Child adjustment in joint-custody versus sole custody arrangements: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 1, 91-102. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.1.91 Bauserman, R. (2012). A meta-analysis of parental satisfaction, adjust- ment, and conflict in joint custody and sole custody following di- vorce. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 53, 464-488. doi:10.1080/10502556.2012.682901 Bredefeld, G. (1985). Joint custody and remarriage: Its effects on mari- tal adjustment and children. Dissertation Abstracts International, 46, 952-953. Buchanan, C. M., Maccoby, E. E., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1996). Adole- scents after divorce. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Catalán, M., García, B., Alemán, C., Andreu, P., Esquiva, A., García, M. D., et al. (2008). Joint Custody: Requesting the type of custody in contested and uncontested cases since the approval of the new law on divorce. In F. J. Rodríguez, C. Bringas, F. Fariña, R. Arce, & A. Ber- nardo (Eds.), Forensic psychology: Family and victimology (pp. 123- 129). Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo. CIS (2007). Survey of Spanish youth. Estudio CIS No. 2675. Coloma, A. (2011). Joint care and custody. An equalitarian family measure. Barcelona: Reus. European Commission of Member States (2009). Report from the Com- mission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Eco- nomic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions— Equality between women and men. 2009. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:520 09DC0077:ES:NOT Fariña, F. (2010). Family counselling, a right and a need. In F. Fariña, R. Arce, M. Novo, & D. Seijo (Eds.), Separation and divorce: Pa- rental interference (pp. 207-225). Santiago de Compostela: NINO. Gunnoe, M. L., & Braver, S. L. (2001). The effects of joint legal cus- tody on mothers, fathers and children controlling for factors that pre- dispose a sole maternal versus joint legal award. Law and Human Behavior, 25, 25-43. doi:10.1023/A:1005687825155 Hanson, S. M., &. Boxett, F. W. (1985). Dimensions of fatherhood. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Hausmann, R., Tyson, L., & Zahidi, S. (2012). The Global Gender Gap Report 2012. Ginebra: Worl Economic Forum. INE (2012). Notas de prensa sobre las estadísticas de Nulidades, Separaciones y Divorcios d e l Año 2011. http://www.ine.es/prensa/np735.pdf Instituto de Política Familiar (2010). El divorcio en la Unión Europea. Boletín Monográfico O n l i n e , 8, 1-20. Lamb, M. (2002). Non residential fathers and their children. In C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, & N. Cabrera (Eds.), Handbook of father involve- ment: Multidisciplinary perspective (pp. 169-184). Mahwah, NJ: Law- rence Erlbaum. Lathrop, F. (2009). Joint custody and parental co-responsibility: Judicial and sociological approaches. Diario La Ley, 7206, 1-6. Law 15/2005 (2005). 8 July, that modifies the Civil Code, and the Law on Civil Proceedings regarding separation and divorce. BOE, 163, 24458-24461. Law 2/2010 (2010). 26 May, on equality of family relations within the parental home. BOE, 151, 54523-54533. Law 25/2010 (2010). 29 July, on the Second Book of the Civil Code of Catalonia in relation to people and families. BOE, 203, 73429-73525. Law 7/2004 (2004). 16 July, Galician equality for women and men. BOE, 228, 31571-31580. Law 1/2004 (2004). 28 December, Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence. BOE, 331, 42166-42197. Law 3/2007 (2007). 22 March, for the effective equality of women and men. BOE, 71, 12611-12645. López, A., Gil, G., Moreno, A., Comas, D., Funes, M. J., & Parella, S. (2008). Inform e J u v e n t ud en España. Madrid: INJUVE. Luepnitz, D. (1980). Maternal, paternal and joint custody: A study of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 59  F. FARIÑA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 60 familiar after divorce. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Ann Ar- bor, MI: University of Michigan. Luepnitz, D. (1982). Child custody: A study of families after divorce. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Meil, G. (2006). Parents and children in current society. Barcelona: Fundación Obra Social La Caixa. Spanish Ministry of Equality (2009). Two-year assessment report on the application of Law 3/2007, 22 March for the effective equality of women and men. Navarro, L. (2006). The ideal family model in spanish society. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 43, 119-138. Ortuño, P. (2006). El nuevo régimen jurídico de la crisis matrimonial. Madrid: Civitas. Patrician, M. (1984). Child custody terms: Potencial contributors to cu- stody dissatisfaction and conflict. Mediation Quaterly, 1, 41-57. Pearson, J., & Thoennes, N. (1990). Custody after divorce. Demogra- phical and attitudinal patterns. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 56, 486-489. Recommendation (2006). 19 of the Committee of Ministers of Member States concerning supporting policing for undertaking positive pa- renting. Council of Europe. http://www.parentalidadpositiva.jorfam.es/images/Pdf/Recomendaci on.pdf Shiller, V. (1984). Joint and maternal custody: The outcome for boys aged 6 - 11 and their parents. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Newark, DE: University of Delaware. Shiller, V. (1986). Joint versus maternal custody for families with la- tency age boys: Parent characteristics and child adjustment. Ameri- can Journal of Orthopsychiat ry , 56, 486-489. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1986.tb03481.x SOS PAPA (2005). Encuesta Gallup 20 05 . http://www.federacioncustodiacompartida.org/contenidos/noticia1.html UN (1979). The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discri- mination against Wome n (CEDAW). http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm Welsh-Osga, B. (1981). The effects of custody arrangements on chil- dren of divorce. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Vermillion, SD: University of South Dakota. Yárnoz, S. (2010). Towards post-divorce co-parenting: Perceptions of support from ex-partners in divorced child carers in Spain. Interna- tional Journal of Psycholo gy a nd Health, 2, 295-307. Zimmerman, M. (2000). Empowerment theory. Psychological, organi- zational and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport, & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of Community Psychology (pp. 43-63). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plen.

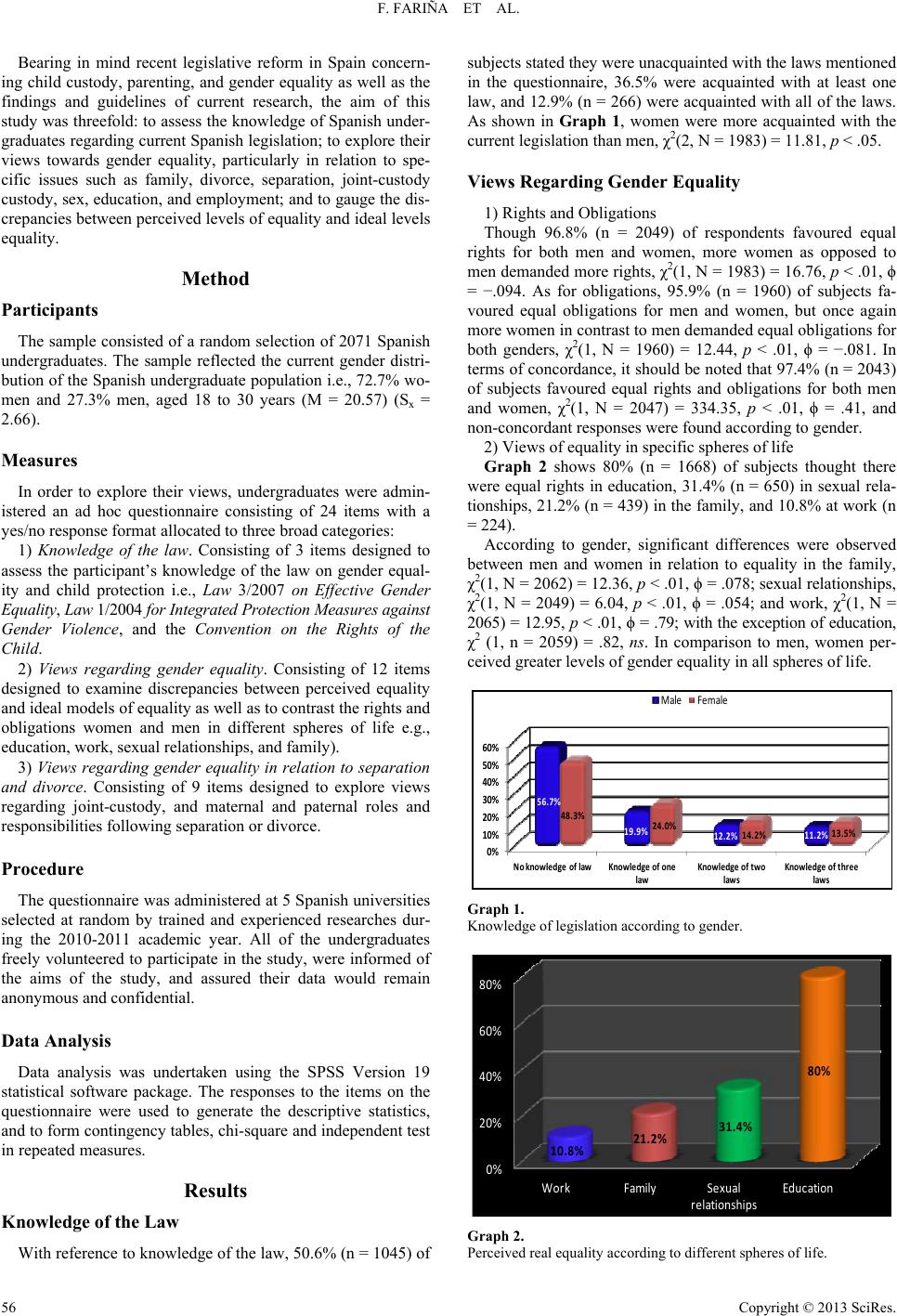

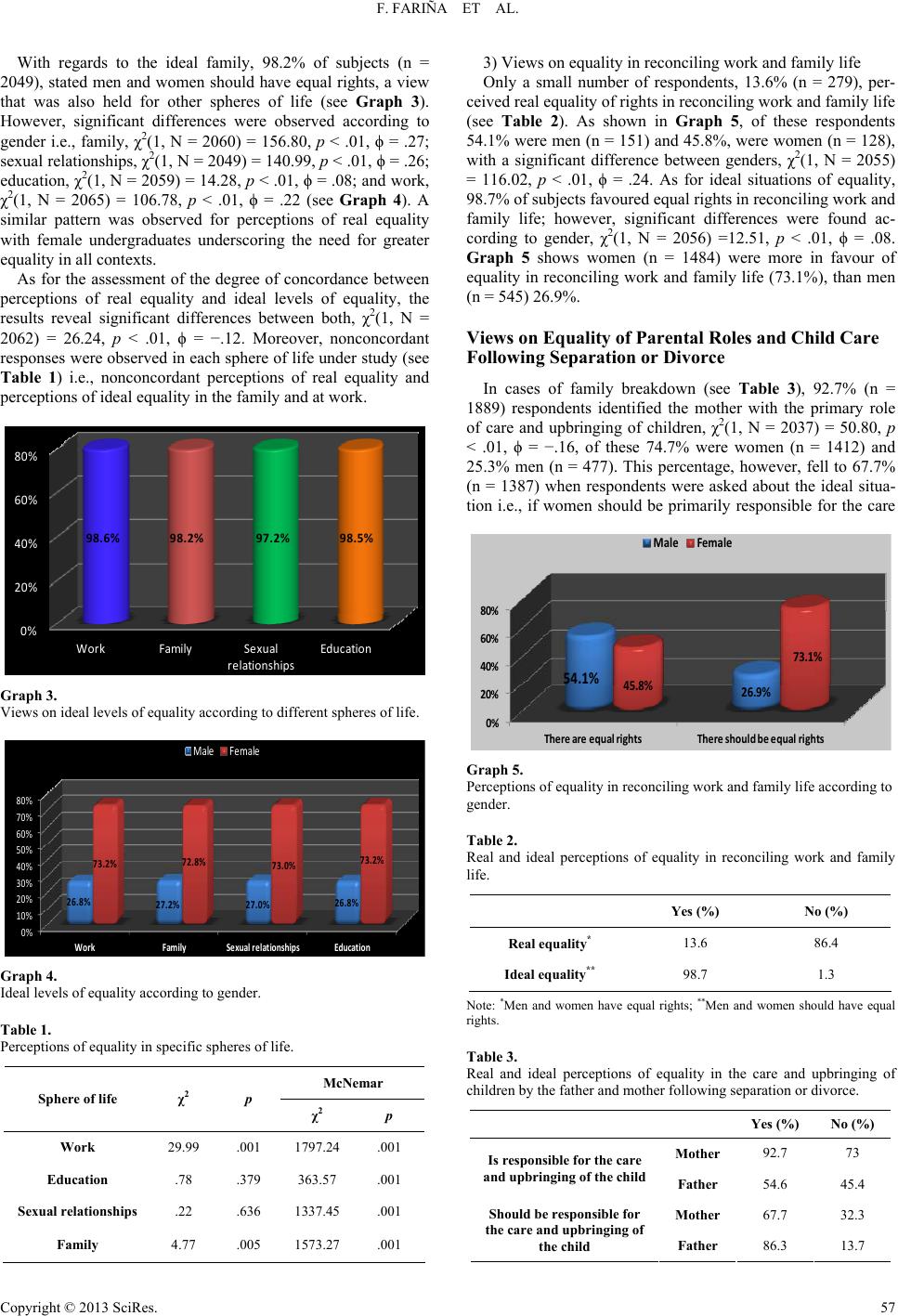

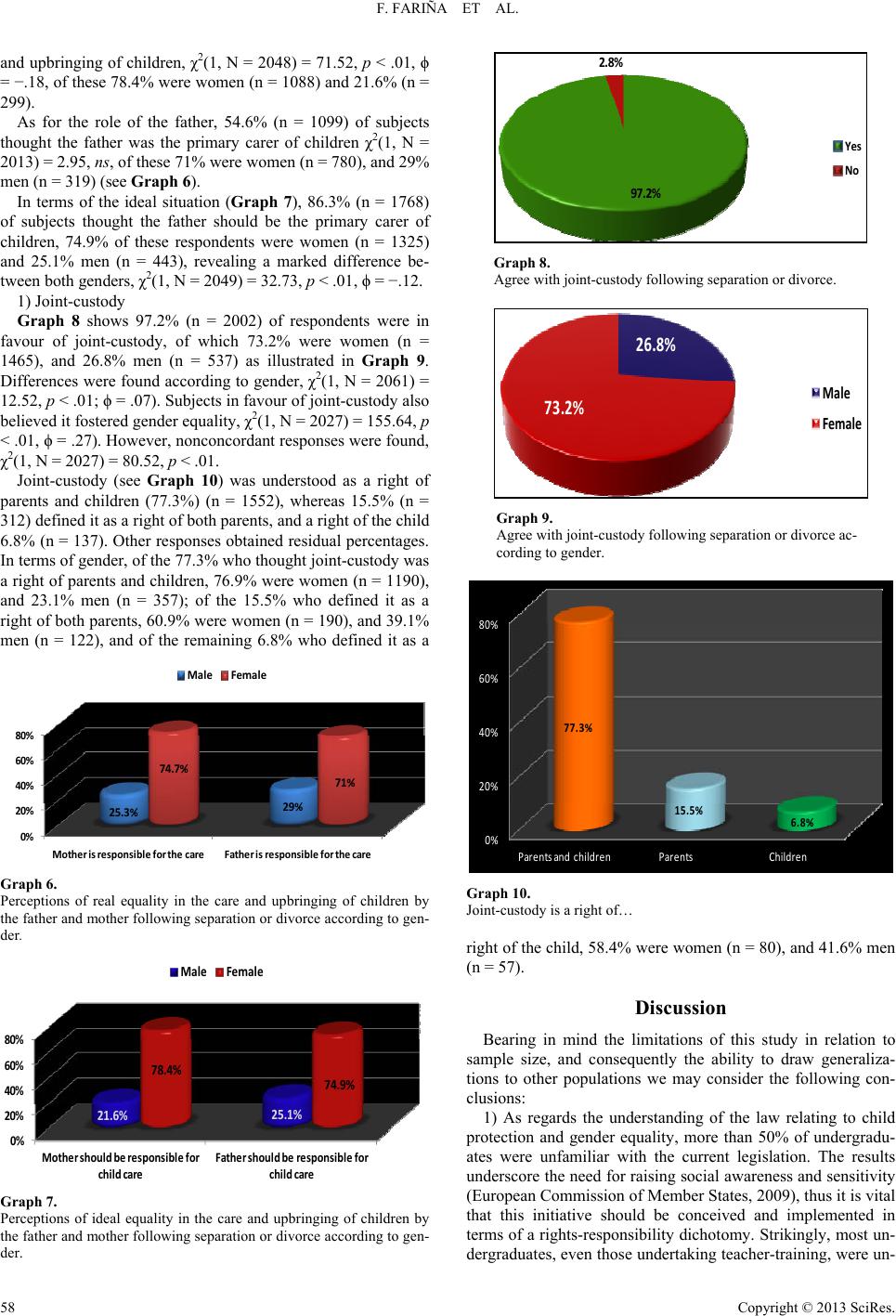

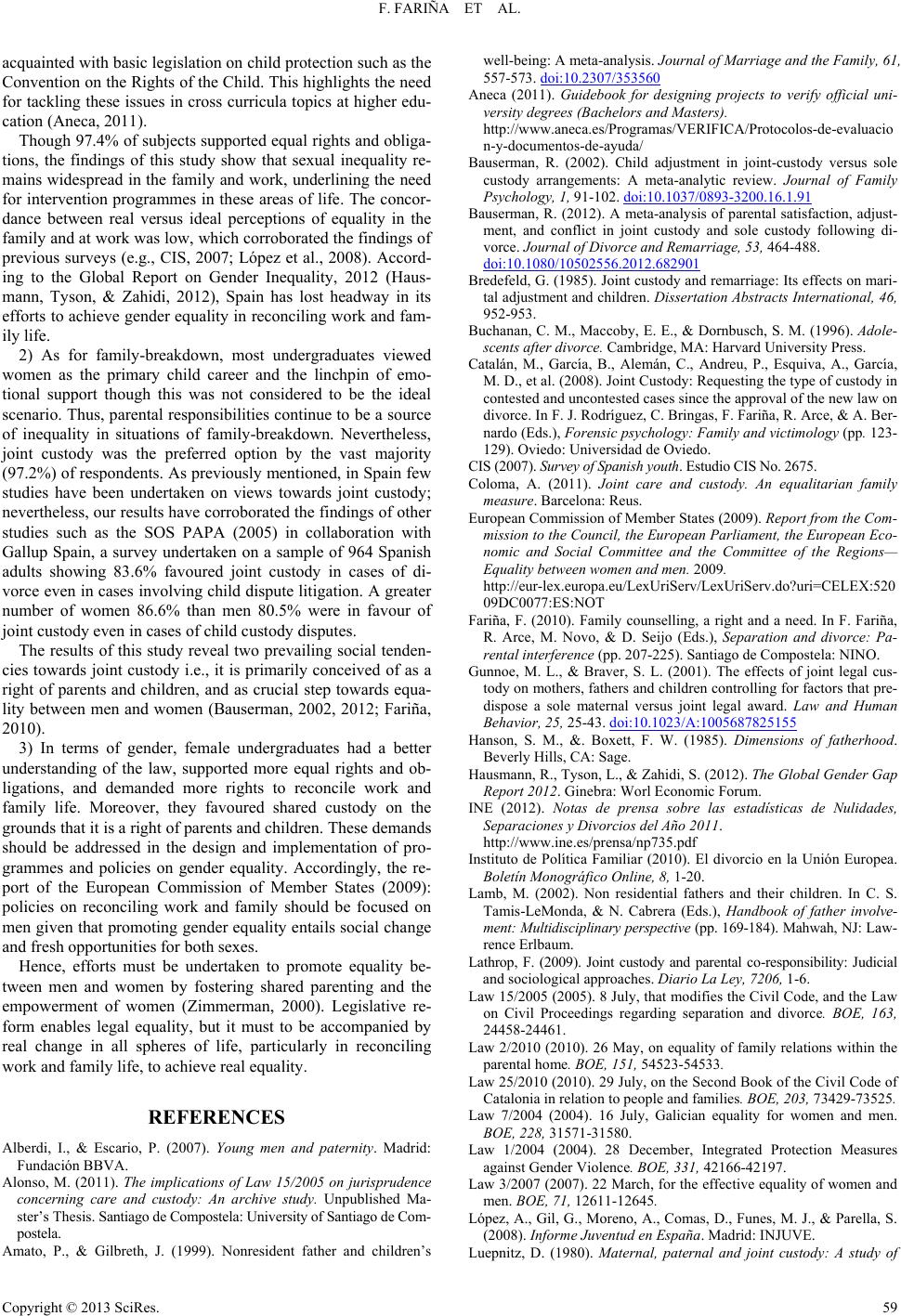

|