Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2013, 4, 233-239 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/fns.2013.43031 Published Online March 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns) Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh* Sumon Kumar Das, Mohammod Jobayer Chisti, Sayeeda Huq, Mohammad Abdul Malek, Mohammed Abdus Salam, Tahmeed Ahmed, Abu Syed Golam Faruque# International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Email: sumon@icddrb.org, chisti@icddrb.org, sayeeda@icddrb.org, mamalek@icddrb.org, masalam@icddrb.org, tahmeed@icddrb.org, #gfaruque@icddrb.org Received December 12th, 2012; revised January 12th, 2013; accepted January 20th, 2013 ABSTRACT There is inadequate information on the etiology of diarrhea in severely malnourished (SM) young children. Thus, the study aimed to determine the etiology of diarrhea among severely malnourished (z score < −3.00 SD) children in rural and urban Bangladesh. From the database (2000-2011) of Diarrheal Disease Surveillance Systems (DDSS) at rural Matlab and urban Dhaka hospitals of icddr,b, 2234 and 3109 under-5 children were found severely malnourished (un- derweight, stunted or wasted) respectively. Two comparison groups [moderately malnourished (MM) and well-nour- ished (WN)] were randomly selected in a ratio of 1:1:1. Children with all categories of SM were more likely to be in- fected with Vibrio cholerae (rural—11%; urban—15%), Shigella (16%; 9%), Salmonella (1%; 2%) and Campylobacter (3%; 4%); and less likely to have rotavirus (25%; 20%) compared to only one SM category. Isolation rate of Vibrio cholerae was significantly higher among SM both in rural and urban children (7%; 13%) than those of MM (5%; 10%) and WN (2%; 8%) and lower for rotavirus (30%; 31%), (34%; 43%), (35%; 47%) respectively (p < 0.01). However, for Shigella it was only higher among rural SM children (11%) [MM (9%), and WN (8%) (p < 0.01)]. The isolation rate of Salmonella in SM (2%) was similar to that in MM (2%; p = 0.72) but significantly higher than that in WN (1%; p < 0.01) among urban children. Isolation rates of bacterial enteric pathogens were higher but rotavirus was lower in SM children in both rural and urban area with geographical heterogeneity. Keywords: Diarrhea; Under-5 Children; Rural; Severe Malnutrition; Urban 1. Introduction Despite reductions in global deaths due to diarrhea in under five children to around 400,000 each year, globally (range, 200,000 to 500,000) during 2000-2010, the mor- tality rate is still high [1] and diarrhea remains the second leading cause of childhood deaths [2]. Malnutrition is associated with both macro-and micronutrient deficien- cies [3], and directly or indirectly related to 35% of all deaths among under-five children [4]. Severe malnutri- tion is often associated with life-threatening consequences such as hypoglycaemia, hypothermia, hypernatremia, se- vere chest infection, sepsis, and severe electrolyte dis- turbances [5]. Childhood malnutrition remains an important public health problem in Asian subcontinent; although most of the countries in this region have experienced rapid eco- nomic development in the recent years [3]. Each of the different types of nutritional deficits such as underweight, stunting and wasting is associated with increased deaths from diarrhea, respiratory infections and other infectious diseases such as measles [6]. A 4-year prospective study among severely acute malnourished children aged 6 months to 12 years, hospitalized with diarrhea experi- enced higher deaths compared to the children who did not have diarrhea during their hospital stay [7]. A cohort study of 430 Zambian children aged 6 - 59 months with severe acute malnutrition noted 2.5 times higher deaths in those with diarrhea on admission compared to those who did not have diarrhea [8]. *There is no potent conflict of interest to declare. All authors confirm that there is no professional affiliation, financial agreement or other involvement with any company whose product figures prominently in the submitted manuscript. #Corresponding author. According to Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011, the prevalence of childhood stunting, un- derweight and wasting were 43%, 41% and 17% respec- tively [9]. Most of the earlier studies have identified as- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS  Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh 234 sociation between malnutrition and diarrhea and exam- ined association of etiologic agents of diarrhea with mal- nutrition [10-12]. However, most of the analyses did not consider geographical diversity. In our analysis, we ex- amined the distribution of the common etiology of diar- rhea among severely malnourished under-five children in two distinct geographical locations. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Study Site The study was conducted among the under-five children visiting the urban Dhaka Hospital and rural Matlab Hos- pital of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). 2.1.1. Dh aka Hospital Established in 1963, the Dhaka Hospital, located in urban Dhaka, currently provides cost free care and treatment to around 140,000 diarrheal patients each year. The hospital maintains a Diarrheal Disease Surveillance System (DDSS) since 1979, and systematically enrolls (2% since 1996) patients attending the facility, irrespective of age and sex. The DDSS provides valuable information to hospital clinicians in their decision-making processes and enables to detect the emergence of new pathogens and in early identification of outbreaks and their locations, thereby alerts the host government to take appropriate preventive and control measures. Extensive microbiological assess- ments of fecal samples (culture, ELISA, and microscopy) are performed to identify diarrheal pathogens. 2.1.2. M atlab Hospi tal icddr,b maintains a treatment facility in rural Matlab (Matlab Hospital), about 55 kilometres from Dhaka, since 1963. It provides free treatment to 12,000 - 15,000 diarrhea patients annually reporting from Health and Demographic Surveillance System area and other ad- joining sub-districts. The Matlab DDSS has been initi- ated in 2000, which enrolls all patients coming from the areas of active Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) of icddr,b. 2.2. Definition Diarrhea was defined as passage of three or more abnor- mally loose or watery stool within last 24 hours. Severe malnutrition was defined (using z-scores) as: severe stunt- ing (SS; height-for-age z-score < −3.00); severe under- weight (SU; weight-for-age z-score < −3.00), and severe wasting (SW; weight-for-height z-score < −3.00), using the World Health Organization reference value [12]. Moderate malnutrition was defined as follows: moderate stunting (height-for-age z-score −3.00 to < −2.00); mod- erate underweight (weight-for-age z-score −3.00 to < −2.00); and moderate wasting (weight-for-height z-score −3.00 to < −2.00). We considered children as well-nour- ished if their z-scores for weight-for-age, height-for-age and weight-for-height z-score were form −2.00 to +1.00. 2.3. Sample Frame From 2000 to 2011, at the rural Matlab Hospital 10,794 under-five children were enrolled in DDSS; and 27,276 under-five children at the urban Dhaka Hospital. Out of all under-5 children, 2234 children in Matlab and 3109 children in Dhaka were severely malnourished defined by any of the above mentioned categories: SU (364 and 518 respectively); SS (449 and 502 respectively); SW (253 and 242 respectively); SU with SS (530 and 929 respectively); SU with SW (456 and 563 respectively); and SU with SS with SW (182 and 355 respectively); but none of them had both SS and SW. For each severely malnourished child, we randomly selected one child with moderate malnutrition and one well-nourished child for comparison from both rural and urban hospitals. 2.4. Data Analysis Data analyses were done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Windows (Version 15.2; Chicago, IL) and Epi Info (Version 6.0, USD, Stone Mountain, GA). Descriptive analysis was employed and Chi-square test was performed for comparing proportions and a probability of <0.05 was considered as statistically sig- nificant. Strength of association was determined by esti- mating odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). 2.5. Ethical Consideration The DDSS of icddr,b is a regular disease monitoring system of the hospitals, which had approval of the Re- search Review Committee (RRC) and Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of icddr,b. 3. Results Children under 5 years, who were severely underweight, wasted and stunted, were more likely to be infected with Vibrio cholerae, Shigella, Salmonella and Campylobac- ter; and less likely to be infected with rotavirus in rural Matlab (Tab le 1). Analogous observation was also found only for rotavirus in the urban Dhaka; however, distribu- tion of other pathogens was found almost similar (Table 2). The isolation rates of Shigella were higher in rural area. However, Vibrio cholerae and Campylobacter were higher among urban severely malnourished children compared Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS  Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS 235 to their rural counterparts (Table 3). Severely malnourished children from rural Matlab were more likely to be infected with Vibrio cholerae than well-nourished and moderately malnourished children. So for Shigella; Shigella flexneri and Shigella dysente- riae were more prevalent among severely malnourished children compared to well-nourished. Conversely, chil- dren with severe malnutrition less likely experienced rota- viral diarrhea compared to well-nourished children, and the proportion was even lower than moderately malnour- ished children (Table 4). On the other hand, in urban Dhaka, similar trend of isolation pattern for Vibrio cholerae and rotavirus was observed among under-5 children with severe malnutri- tion compared to moderately malnourished and well- nourished. Although, isolation rate of Salmonella was very low among all the groups, it was higher among se- verely malnourished children than others (Table 5). The isolation rates of Campylobacter, Entamoeba histolytica, and Giardia lamblia were found to be identical in all the groups (Tables 4 and 5). 4. Discussion Significant variations in isolation pattern of common enteropathogens causing diarrhea among severely mal- nourished under-5 years old children in both rural and urban areas were observed. However, isolation rates were also significantly different between urban and rural area. Vibrio cholerae, Shigella and rotavirus are the major pathogens that cause diarrhea [13]. Children under 5 years of age have the highest burden of cholera in the endemic areas [14,15], and also at risk to have dehydrate- ing diarrhea [16,17]. Study suggested a lack of innate and cell-mediated immune responses among children against V. cholerae [18]. Conversely, malnutrition is a risk factor for shigellosis and children infected with Shigella were also likely to become malnourished [19]. Malnutrition Table 1. Distribution of pathogens by nutritional status category of the under-five children at rural Matlab Hospital (2000-201 1) . Pathogens SU n = 364 (%) SS n = 449 (%) SW n = 253 (%) SU with SS n = 530 (%) SU with SW n = 456 (%) SU with SS with SW n = 182 (%) Vibrio cholerae 23 (6)* 20 (5)* 5 (2)* 47 (9) 39 (9) 20 (11) Overall Shigella 34 (9)* 51 (11) 25 (10)* 63 (12) 48 (11) 29 (16) S. flexneri 26 (7) 37 (8) 18 (7) 46 (9) 38 (8) 20 (11) S. sonnei 1 (0) 2 (0) 4 (2) 8 (2) 3 (1) 2 (1) S. dysenteriae 5 (1) 5 (1) 2 (1) 4 (1) 1 (0) 4 (2) S. boydii 2 (1) 7 (2) 1 (0) 5 (1) 6 (1) 3 (2) Salmonella 7 (2) 4 (1 ) 4 (2) 7 (1) 8 (2) 1 (1) Rotavirus 108 (30) 144 (32) 95 (38)* 135 (26) 141 (31) 46 (25) Campylobacter 7 (2) 5 (1) 8 (3) 14 (3) 12 (3) 5 (3) E. histolytica 1 (0) 3 (1) 1 (0) 9 (2) 1 (0) 0 Giardia lamblia 9 (3) 3 (1) 2 (1) 14 (3) 5 (1) 2 (1) SU, severe underweight; SS, severe stunting; SW, severe wasting. *Values were compared with SU with SS with SW and were significant at 5% level. Table 2. Distribution of pathogens by nutritional status category of the under-five children at urban Dhaka Hospital (2000-2011). Pathogens SU n = 518 (%) SS n = 502 (%) SW n = 242 (%) SU with SS n = 929 (%) SU with SW n = 563 (%) SU with SS with SW n = 355 (%) Vibrio cholerae 63 (12) 61 (12) 39 (16) 124 (13) 62 (11) 54 (15) Overall Shigella 27 (5) 26 (5) 8 (3)* 56 (6) 30 (5) 31 (9) S. flexneri 15 (3) 16 (3) 2 (1) 31 (3) 15 (3) 21 (6) S. sonnei 2 (0) 2 (0) 0 (0) 7 (1) 8 (1) 3 (1) S. dysenteriae 6 (1) 2 (0) 1 (0) 4 (2) 5 (1) 2 (1) S. boydii 4 (1) 6 (1) 5 (2) 14 (2) 2 (0) 5 (1) Salmonella 7 (1) 9 (2) 5 (2) 13 (1) 15 (3) 7 (2) Rotavirus 176 (35)* 208 (42)* 84 (35)* 231 (25)* 177 (32)* 68 (20) Campylobacter 22 (4) 17 (3) 12 (5) 35 (4) 22 (4) 14 (4) E. histolytica 0 (0) 3 (1) 0 (0) 2 (0) 6 (1) 1 (0) Giardia lamblia 2 (0) 4 (1) 0 (0) 6 (1) 3 (1) 1 (0) SU, severe underweight; SS, severe stunting; SW, severe wasting. *Values were compared with SU with SS with SW and were significant at 5% level.  Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh 236 Table 3. Urban-rural differentiation of pathogens among severely malnourished under-5 children (2000-2011). Pathogens Rural; n = 2234 (%) Urban; n = 3109 (%) OR (95% CI) p value Vibrio cholerae 154 (7) 403 (13) 0.50 (0.40, 0.61) <0.001 Overall Shigella 250 (11) 178 (6) 2.07 (1.69, 2.55) <0.001 S. flexneri 185 (8) 100 (3) 2.72 (2.10, 3.51) <0.001 S. sonnei 20 (1) 22 (1) 1.27 (0.66, 2.42) 0.542 S. dysenteriae 21 (1) 20 (6) 1.47 (0.76, 2.82) 0.285 S. boydii 24 (1) 36 (1) 0.93 (0.53, 1.60) 0.877 Salmonella 31 (1) 56 (2) 0.77 (0.48, 1.22) 0.285 Rotavirus 669 (30) 944 (31) 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) 0.766 Campylobacter 51 (2) 122 (4) 0.57 (0.41, 0.81) 0.001 E. histolytica 15 (1) 12 (0) 1.74 (0.77, 3.97) 0.209 Giardia lamblia 35 (1) 16 (1) 3.08 (1.64, 5.82) <0.001 Table 4. Distribution of pathogens among severely malnourished, moderately malnourished and well nourished under-5 chil- dren in rural Matlab Hospital (2000-2011). Pathogens Severely malnourished n = 2234 (%) Moderately malnourished n = 2234 (%) OR (95% CI) p valueaWell nourished n = 2234 (%) OR (95% CI) p valueb Vibrio cholerae 154 (7) 107 (5) 1.47 (1.13, 1.91) 0.00341 (2) 3.969 (2.76, 5.71) <0.001 Overall Shigella 250 (11) 202 (9) 1.27 (1.04, 1.55) 0.019176 (8) 1.47 (1.20, 1.81) <0.001 S. flexneri 185 (8) 157 (7) 1.19 (0.95, 1.50) 1.28136 (6) 1.39 (1.10, 1.76) 0.005 S. sonnei 20 (1) 20 (1) 1.00 (0.51, 1.94) 0.87313 (1) 1.54 (0.73, 3.29) 0.294 S. dysenteriae 21 (1) 12 (1) 1.76 (0.82, 3.80) 0.1626 (0) 3.52 (1.35, 9.75) 0.006 S. boydii 24 (1) 13 (1) 1.86 (0.90, 3.86) 0.09821 (1) 1.14 (0.61, 2.14) 0.764 Salmonella 31 (1) 29 (1) 1.07 (0.62, 1.83) 0.89631 (1) 1.00 (0.59, 1.70) 0.898 Rotavirus 669 (30) 755 (34) 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) 0.006771 (35) 0.81 (0.71, 0.92) 0.001 Campylobacter 51 (2) 44 (2) 1.16 (0.76, 1.78) 0.53338 (2) 1.35 (0.87, 2.11) 0.198 E. histolytica 15 (1) 11 (1) 1.37 (0.59, 3.19) 0.5554 (0) 3.77 (1.17, 13.43) 0.021 Giardia lamblia 35 (2) 36 (2) 0.97 (0.59, 1.59) 1.00035 (2) 1.00 (0.61, 1.64) 0.904 aComparison between severely malnourished vs. moderately malnourished; bComparison between severely malnourished vs. well-nourished. Table 5. Distribution of pathogens among severely malnourished, moderately malnourished and well nourished under-five children at the urban Dhaka Hospital (2000-2011). Pathogens Severely malnourished n = 3109 (%) Moderately malnourished n = 3109 (%) OR (95% CI) p valueaWell nourished n = 3109 (%) OR (95% CI) p value b Vibrio cholerae 403 (13) 317 (10) 1.31 (1.12, 1.54) <0.001248(8) 1.72 (1.45, 2.04) <0.001 Overall Shigella 178 (6) 151 (5) 1.19 (0.95, 1.50) 0.140160 (5) 1.12 (0.89, 1.40) 0.341 S. flexneri 100 (3) 82 (3) 1.23 (0.90, 1.67) 0.20082 (3) 1.23 (0.90, 1.67) 0.200 S. sonnei 22 (1) 23 (1) 0.96 (0.51, 1.78) 1.00029 (1) 0.76 (0.42, 1.36) 0.398 S. dysenteriae 20 (6) 9 (0) 1.06 (0.54, 2.07) 0.9919 (0) 2.23 (0.96, 5.29) 0.062 S. boydii 36 (1) 37 (1) 0.97 (0.60, 1.58) 1.00040 (1) 0.90 (0.56, 1.45) 0.729 Salmonella 56 (2) 38 (1) 1.48 (0.96, 2.29) 0.07730 (1) 1.88 (1.18, 3.01) 0.006 Rotavirus 944 (31) 1328 (43) 0.58 (0.53, 0.65) <0.0011445 (47) 0.50 (0.45, 0.56) <0.001 Campylobacter 122 (4) 143 (5) 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) 0.209124 (4) 0.98 ( 0.76, 1.28) 0.948 E. histolytica 12 (<1) 5 (<1) 2.41 (0.79, 7.82) 0.1453 (<1) 4.01 (1.06, 17.88) 0.038 Giardia lamblia 16 (1) 25 (1) 0.64 (0.32, 1.24) 0.21021 (1) 0.76 (0.38, 1.52) 0.509 aComparison between severely malnourished vs. moderately malnourished; bComparison between severely malnourished vs. well-nourished. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS  Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS 237 causes atrophy and decreased cell proliferation of the Thymus gland resulting in depletion of CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes [20,21]. Thus, there is impaired peripheral immune response that favors the pathogens to become virulent. This might explain the higher rate of isolation of V. cholerae and Shigella among severely malnourished children compared to others. Moreover, severe malnutri- tion leads to atrophy of the gastric mucosa resulting in less production of hydrochloric acid which favors the higher rate of infection due to less infective doses of common bacterial pathogens [22]. On the other hand, rotavirus causes diarrhea either by malabsorption second- dary to enterocyte destruction, a virus-encoded toxin, stimulation of the enteric nervous system (ENS), and villus ischemia [23,24] in malnutrition. Malnutrition causes decreased number of intestinal lining epithelial cells and impair its proliferation [25]. Thus, due to lack of mucosal cells to adhere for rotavirus causing diarrhea would be the possible explanation of lower isolation rate among severely malnourished children. Distinct geographical variation may explain the diver- sity in socio-demographic and cultural factors, water- sanitation practices and also mass rotavirus vaccination in rural Matlab [26] might explain the diverse isolation rates between rural-urban areas in addition to household food security. Recent mass rotaviral vaccination might trigger the other pathogens to become virulent or survive better in environment. Severe malnutrition is a complex phenomenon, in- volving interactions of the biological, cultural and socio- economic factors [27]. Parental education, lower socio- economic status, and poor nutritional characteristics, child- feeding practices, and birth-order have strong association with severe malnutrition [10,27]. Conversely, association with higher family food insecurity, low quality of com- plementary foods and high burdens of intestinal parasitic loads and other infections which are persisting despite improvements in socio-economic conditions over recent years have also been documented [28,29]. Severely mal- nourished children are always vulnerable to any infec- tions including diarrhea due to compromised immune function [30]. Having all the category of severe malnutri- tion, a child would be highly susceptible to serious infec- tions. Severe malnutrition with the co-morbidity of diar- rhea [31,32] is a life threatening condition with high fa- tality rate (20%) [7]; however, the present observation was not aimed to determine the fatal outcome. Other than that, contaminated weaning foods prepared under unhy- gienic conditions is a major risk factor for causing diar- rheal diseases and associated malnutrition [33]. A stan- dardized protocol for management of severe malnutrition with diarrhea among under 5 years old children was in- troduced in the Dhaka hospital of icddr,b that reduced mortality by at least 47% [34,35]; moreover, early detec- tion of entero-pathogens helps the clinicians for rational use of antimicrobials and appropriate management of these high risk severely malnourished children. 5. Limitations Although unbiased systematic sampling method was used to enroll patients into surveillance system irrespective of age, sex, nutritional status, disease severity or socioeco- nomic background and the large dataset with standard laboratory facility were supportive of the strengths of this analysis; however, hospital data might not be representa- tive of the general population. 6. Conclusion Severely malnourished children were more prone to be infected with common bacterial pathogens compared to those without severe malnutrition. Integrated manage- ment with early and appropriate antimicrobial therapy needs to be introduced in addition to other resuscitative measures. Furthermore, round the clock monitoring needs to be continued to observe any changing pattern of isola- tion rates of the common pathogens and also there are needs to determine the frequency of isolation of other pathogens causing diarrhea and fatal outcomes. 7. Acknowledgements Hospital surveillance was funded by icddr,b and the Gov- ernment of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh through IHP-HNPRP. icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh to the Centre’s research efforts. icddr,b also gratefully acknowledges the following donors which provide unrestricted support to the Centre’s research ef- forts: Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Government of the People’s Republic of Bang- ladesh, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (EKN), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Swiss Agency for Development and Co- operation (SDC), and Department for International De- velopment, UK (DFID). REFERENCES [1] L. Liu, H. L. Johnson, S. Cousens, J. Perin, S. Scott, J. E. Lawn, I. Rudan, H. Campbell, R. Cibulskis, M. Li, C. Mathers and R. E. Black, “Global, Regional, and National Causes of Child Mortality: An Updated Systematic Analysis for 2010 with Time Trends since 2000,” Lancet, Vol. 379, No. 9832, 2012, pp. 2151-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1  Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh 238 [2] F. Alkizim, D. Matheka and A. Muriithi, “Childhood Diarrhoea: Failing Conventional Measures, What Next?” Pan African Medical Journal, Vol. 8, No. 51, 2011, p. 47. doi:10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71164 [3] S. R. Pasricha and B. A. Biggs, “Undernutrition among Children in South and South-East Asia,” Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, Vol. 46, No. 9, 2010, pp. 497-503. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01839.x [4] World Health Organization (WHO), “Severe Acute Mal- nutrition,” WHO, Geneva, 2004. [5] World Health Organization (WHO), “Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health: Serious Childhood Problems in Countries with Limited Resources,” WHO, Geneva, 2004. [6] R. E. Black, L. H. Allen, Z. A. Bhutta, L. E. Caulfield, M. de Onis, M. Ezzati, C. Mathers and J. Rivera, “Maternal and Child Undernutrition: Global and Regional Exposures and Health Consequences,” Lancet, Vol. 371, No. 9608, 2008, pp. 243-260. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0 [7] A. Talbert, N. Thuo, J. Karisa, C. Chesaro, E. Ohuma, J. Ignas, J. A. Berkley, C. Toromo, S. Atkinson and K. Maitland, “Diarrhoea Complicating Severe Acute Mal- nutrition in Kenyan Children: A Prospective Descriptive Study of Risk Factors and Outcome,” PLoS One, Vol. 7, No. 6, 2012, p. e38321. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038321 [8] A. H. Irena, M. Mwambazi and V. Mulenga, “Diarrhea is a Major Killer of Children with Severe Acute Malnutri- tion Admitted to Inpatient Set-Up in Lusaka, Zambia,” Nutrition Journal, Vol. 10, 2011, p. 110. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-10-110 [9] “Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey,” 2011. www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/PR15/PR15.pdf [10] M. J. Chisti, M. I. Hossain, M. A. Malek, A. S. Faruque, T. Ahmed and M. A. Salam, “Characteristics of Severely Malnourished Under-Five Children Hospitalized with Diarrhoea, and Their Policy Implications,” Acta Paedia- trica, Vol. 96, No. 5, 2007, pp. 693-696. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00192.x [11] B. Nahar, M. I. Hossain, J. D. Hamadani, T. Ahmed, S. N. Huda, S. M. Grantham-McGregor and L. A. Persson, “Effects of a Community-Based Approach of Food and Psychosocial Stimulation on Growth and Development of Severely Malnourished Children in Bangladesh: A Ran- domised Trial,” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 66, No. 6, pp. 701-709. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2012.13 [12] B. Nahar, T. Ahmed, K. H. Brown and M. I. Hossain, “Risk Factors Associated with Severe Underweight among Young Children Reporting to a Diarrhoea Treatment Facility in Bangladesh,” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 476-483. [13] D. M. Denno, N. Shaikh, J. R. Stapp, X. Qin, C. M. Hutter, V. Hoffman, J. C. Mooney, K. M. Wood, H. J. Stevens, R. Jones, P. I. Tarr and E. J. Klein, “Diarrhea Etiology in a Pediatric Emergency Department: A Case Control Study,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 55, No. 7, 2012, pp. 897-904. doi:10.1093/cid/cis553 [14] J. L. Deen, L. von Seidlein, D. Sur, M. Agtini, M. E. Lucas, A. L. Lopez, D. R. Kim, M. Ali and J. D. Clemens, “The High Burden of Cholera in Children: Comparison of Incidence from Endemic Areas in Asia and Africa,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2008, p. e173. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000173 [15] R. B. Sack, A. K. Siddique, I. M. Longini, Jr., A. Nizam, M. Yunus, M. S. Islam, J. G. Morris, Jr., A. Ali, A. Huq, G. B. Nair, F. Qadri, S. M. Faruque, D. A. Sack and R. R. Colwell, “A 4-Year Study of the Epidemiology of Vibrio Cholerae in Four Rural Areas of Bangladesh,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 187, No. 1, 2003, pp. 96-101. doi:10.1086/345865 [16] D. Legros, M. McCormick, C. Mugero, M. Skinnider, D. D. Bek’Obita and S. I. Okware, “Epidemiology of Cholera Outbreak in Kampala, Uganda,” East African Medical Journal, Vol. 77, No. 7, 2000, pp. 347-349. [17] M. A. Luque Fernandez, P. R. Mason, H. Gray, A. Bauernfeind, J. F. Fesselet and P. Maes, “Descriptive Spatial Analysis of the Cholera Epidemic 2008-2009 in Harare, Zimbabwe: A Secondary Data Analysis,” Tran- sactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Vol. 105, No. 1, 2011, pp. 38-45. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.10.001 [18] D. T. Leung, F. Chowdhury, S. B. Calderwood, F. Qadri and E. T. Ryan, “Immune Responses to Cholera in Children,” Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2012, pp. 435-444. doi:10.1586/eri.12.23 [19] R. N. Mazumder, H. Ashraf, S. S. Hoque, I. Kabir, N. Majid, M. A. Wahed, G. J. Fuchs and D. Mahalanabis, “Effect of an Energy-Dense Diet on the Clinical Course of Acute Shigellosis in Undernourished Children,” The British Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 84, No. 5, 2000, pp. 775-779. [20] W. Savino, “The Thymus Gland Is a Target in Mal- nutrition,” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 56, Suppl. 3, 2002, pp. S46-S49. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601485 [21] W. Savino and M. Dardenne, “Nutritional Imbalances and Infections Affect the Thymus: Consequences on T-Cell- Mediated Immune Responses,” Proceedings of the Nu- trition Society, Vol. 69, No. 4, 2010, pp. 636-643. doi:10.1017/S0029665110002545 [22] R. H. Gilman, R. Partanen, K. H. Brown, W. M. Spira, S. Khanam, B. Greenberg, S. R. Bloom and A. Ali, “De- creased Gastric Acid Secretion and Bacterial Colonization of the Stomach in Severely Malnourished Bangladeshi Children,” Gastroenterology, Vol. 94, No. 6, 1988, pp. 1308-1314. [23] M. E. Conner and R. F. Ramig, “Viral Enteric Diseases,” Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, 1997. [24] O. Lundgren and L. Svensson, “The Enteric Nervous System and Infectious Diarrhea,” Elsevier Science BV, Amsterdam, 2003. [25] E. Guiraldes and J. R. Hamilton, “Effect of Chronic Malnutrition on Intestinal Structure, Epithelial Renewal, and Enzymes in Suckling Rats,” Pediatric Research, Vol. 15, No. 6, 1981, pp. 930-934. doi:10.1203/00006450-198106000-00010 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS  Etiology of Diarrhea among Severely Malnourished Infants and Young Children: Observation of Urban-Rural Differences over One Decade in Bangladesh Copyright © 2013 SciRes. FNS 239 [26] K. Zaman, M. Yunus, S. El Arifeen, T. Azim, A. S. Faruque, E. Huq, I. Hossain, S. P. Luby, J. C. Victor, M. J. Dallas, K. D. Lewis, S. B. Rivers, A. D. Steele, K. M. Neuzil, M. Ciarlet and D. A. Sack, “Methodology and Lessons-Learned from the Efficacy Clinical Trial of the Pentavalent Rotavirus Vaccine in Bangladesh,” Vaccine, Vol. 30, Suppl. 1, 2012, pp. A94-A100. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.117 [27] B. Nahar, T. Ahmed, K. H. Brown and M. I. Hossain, “Risk Factors Associated with Severe Underweight among Young Children Reporting to a Diarrhoea Treatment Facility in Bangladesh,” Joyrnal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, Vol. 28, No. 5, 2010, pp. 476-483. [28] B. S. Schwartz, J. B. Harris, A. I. Khan, R. C. Larocque, D. A. Sack, M. A. Malek, A. S. Faruque, F. Qadri, S. B. Calderwood, S. P. Luby and E. T. Ryan, “Diarrheal Epidemics in Dhaka, Bangladesh, during Three Consecutive Floods: 1988, 1998, and 2004,” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Vol. 74, No. 6, 2006, pp. 1067-1073. [29] P. Sanchez, M. S. Swaminathan, P. Dobie and N. Yuksel, “Un Millennium Project 2005. Halving Hunger: It Can Be Donetask Force on Hunger,” Earthscan, London and Sterling, 2005. [30] J. Picot, D. Hartwell, P. Harris, D. Mendes, A. J. Clegg and A. Takeda, “The Effectiveness of Interventions to Treat Severe Acute Malnutrition in Young Children: A Systematic Review,” Health Technology Assessment, Vol. 16, No. 19, 2012, pp. 1-316. doi:10.3310/hta16190 [31] M. J. Chisti, T. Duke, C. F. Robertson, T. Ahmed, A. S. Faruque, P. K. Bardhan, S. La Vincente and M. A. Salam, “Co-Morbidity: Exploring the Clinical Overlap between Pneumonia and Diarrhoea in a Hospital in Dhaka, Bang- ladesh,” Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, Vol. 31, No. 4, 2011, pp. 311-319. doi:10.1179/1465328111Y.0000000033 [32] M. J. Chisti, T. Ahmed, A. S. Faruque and M. Abdus Salam, “Clinical and Laboratory Features of Radiologic Pneumonia in Severely Malnourished Infants Attending an Urban Diarrhea Treatment Center in Bangladesh,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2010, pp. 174-177. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b9a4d5 [33] Y. Motarjemi, F. Kaferstein, G. Moy and F. Quevedo, “Contaminated Weaning Food: A Major Risk Factor for Diarrhoea and Associated Malnutrition,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, Vol. 71, No. 1, 1993, pp. 79-92. [34] T. Ahmed, M. Ali, M. M. Ullah, I. A. Choudhury, M. E. Haque, M. A. Salam, G. H. Rabbani, R. M. Suskind and G. J. Fuchs, “Mortality in Severely Malnourished Children with Diarrhoea and Use of a Standardised Management Protocol,” Lancet, Vol. 353, No. 9168, 1999, pp. 1919- 1922. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07499-6 [35] T. Ahmed, B. Begum, Badiuzzaman, M. Ali and G. Fuchs, “Management of Severe Malnutrition and Diarrhea,” The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 68, No. 1, 2001, pp. 45-51. doi:10.1007/BF02728857

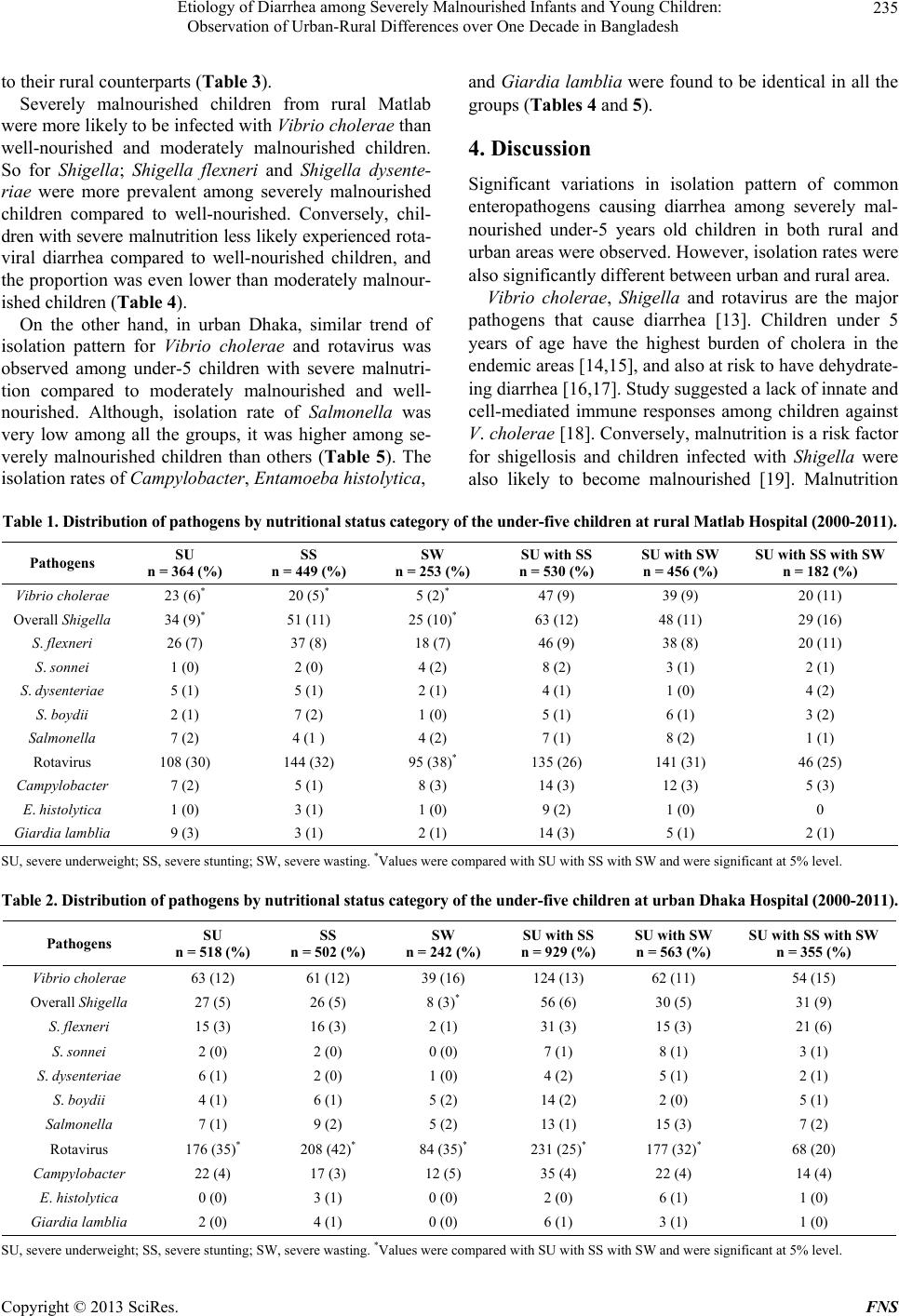

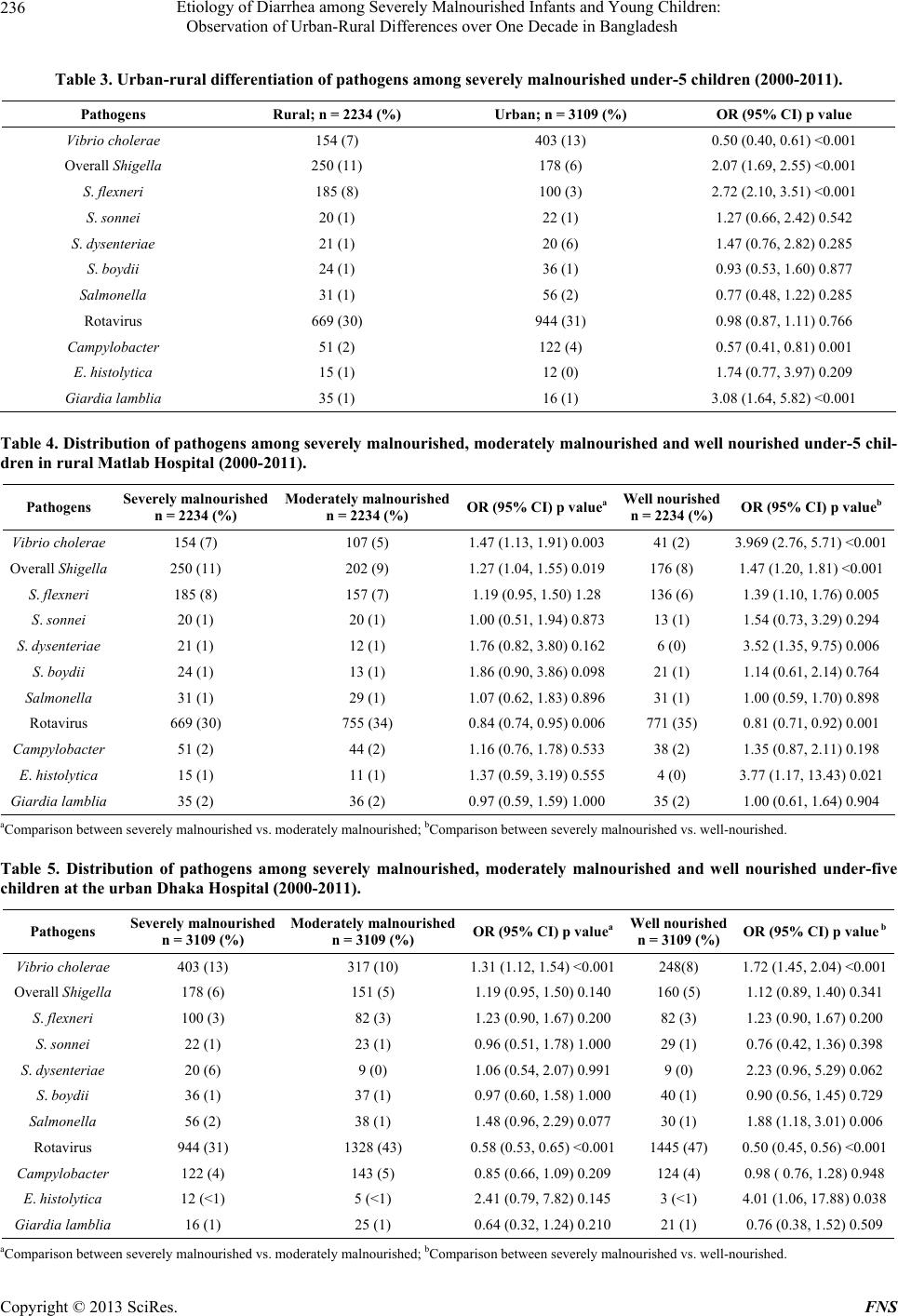

|