Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

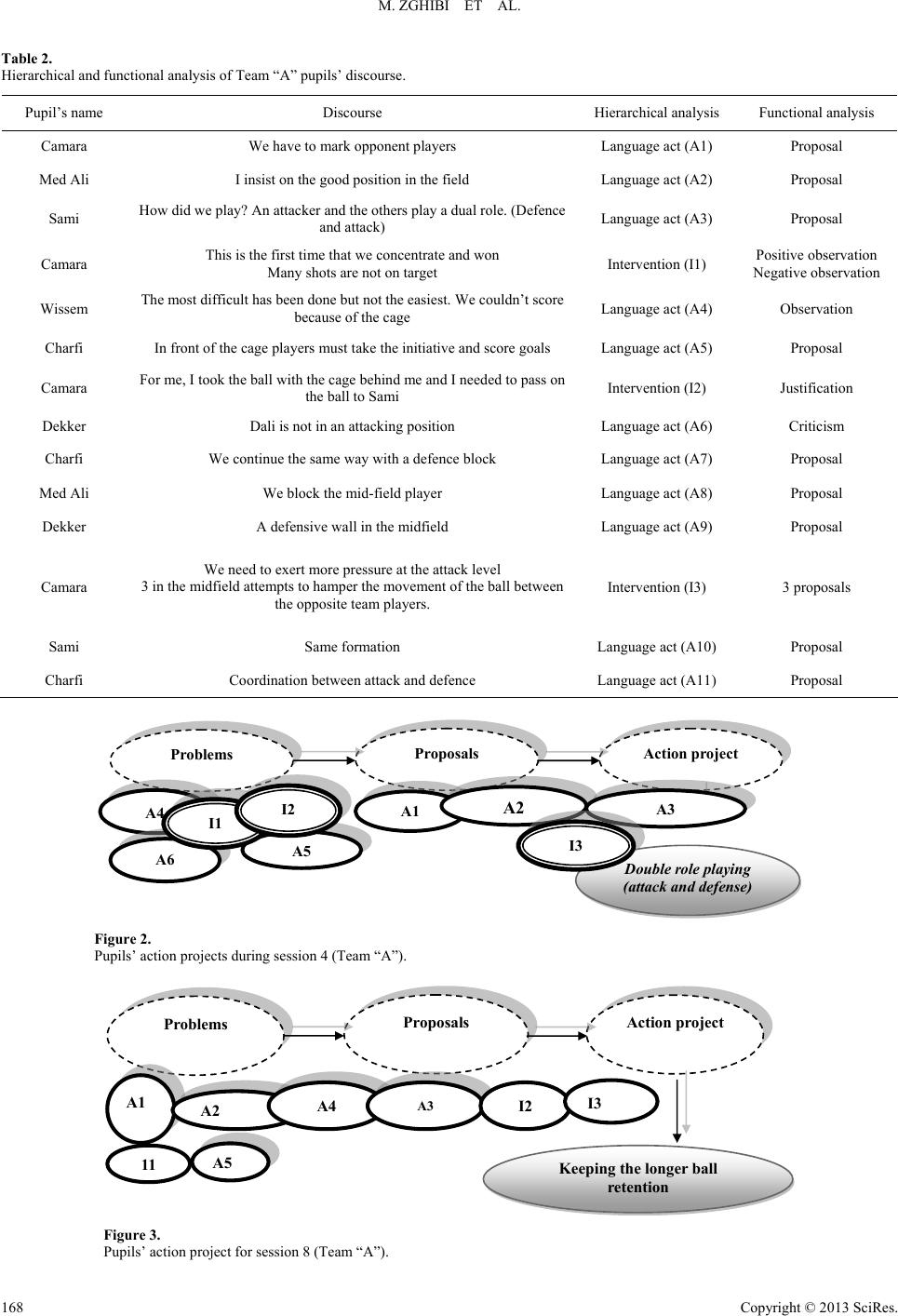

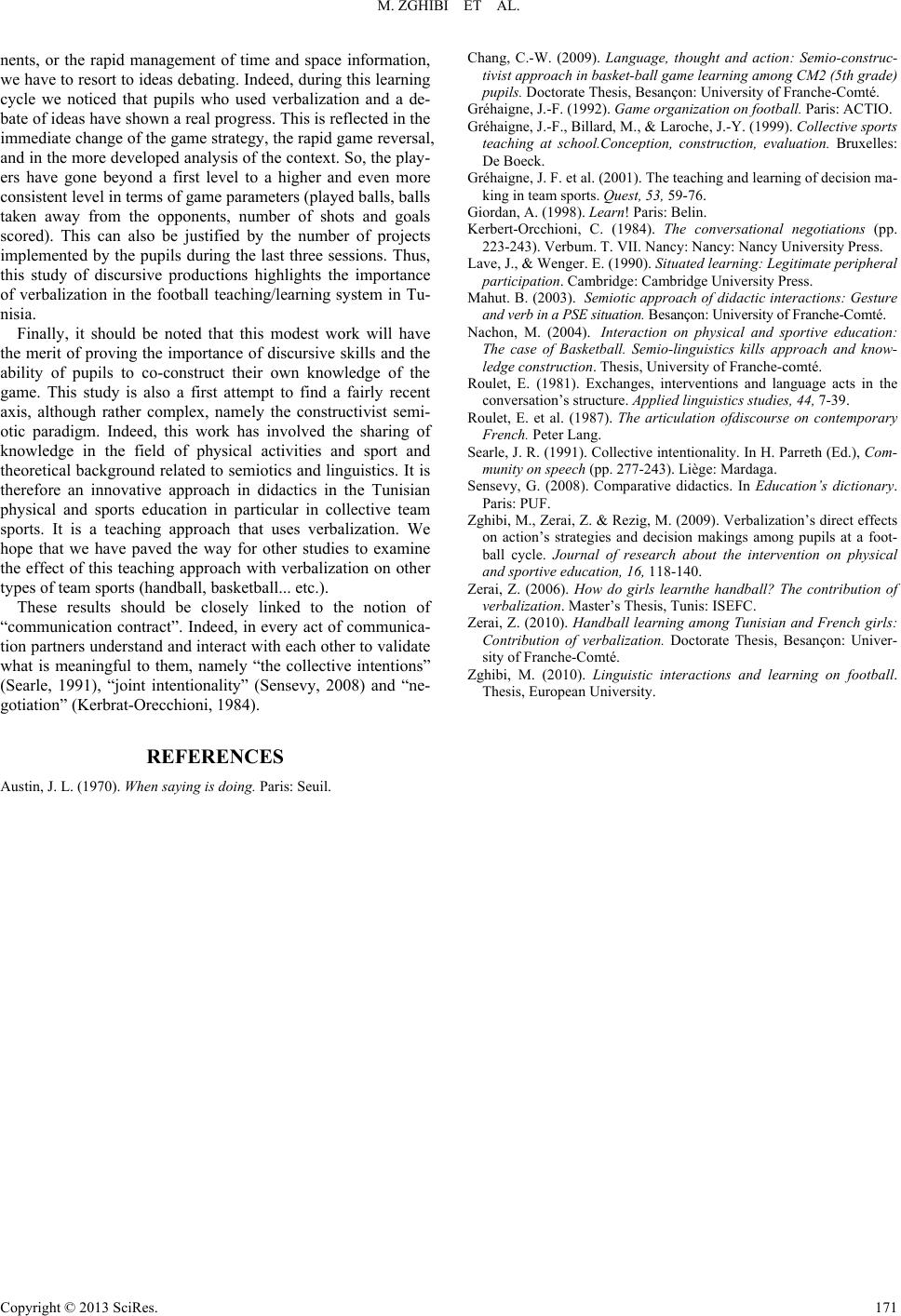

Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.3, 165-171 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) DOI:10.4236/ce.2013.43024 The Pupil’s Discourse and Action Projects: The Case of Third Year High School Pupils in Tunisia Makram Zghibi1, Hajer Sahli2, Nabila Bennour3, Chamseddine Guinoubi2,4, Maher Guerchi2, Moez Hamdi2 1LASELDI, University of Franche-Comté, Besançon, France 2Higher Institute of Sports and Physical Education, Kef, Tunisia 3UMR EFTS, Mirail University of Toulouse I I, Toulouse, France 4Research Laboratory “Sports Performance Optimization”, National Center of Medicine and Science in Sports, Tunis, Tunisia Email: makwiss@yahoo.fr Received January 14th, 2013; revised February 19th, 2013; accepted March 3rd, 2013 The purpose of this paper is to describe the language interaction of pupils in a football game situation and to show how the action plans are implemented. We have opted for a descriptive/exploratory methodology that seeks to convey the pupil’s language typologies: 8 sessions lasting one hour each with 14 boys aged 18 years and T = 8 hours of actual practice. The goal is to help pupils to understand what happens during the play situation in order to co-construct and implement a project of collective action. The study includes: 1) a qualitative analysis (Roulet, 1987) of Team “A” which aims to identify action projects developed by the boys, 2) a quantitative analysis of the same team (Gréhaigne, Billiards, & Laroche, 1999) seeking to check the implementation of these projects. The quantitative study showed that pupils were able to vali- date their action plans during the eight sessions. These results should be linked to the notion of “commu- nication contract”. Indeed, in every act of communication, partners understand and interact with each other by validating what makes sense to them, namely: “the collective intentions” (Searle, 1991), “joint intentionality” (Sensevy, 2008) and “negotiation” (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 1984). Keywords: Oral Verbalization; Action Project; Game; Football Introduction The semio-constructivist approach in physical and sports education and particularly in team sports is a new and innova- tive approach of research in didactics of physical activities and sport. Recent studies carried out in this framework have fo- cused on the main role of language interaction in the co-con- struction of knowledge (Gréhaigne et al., 2001; Wallian, 2003; Mahut, 2003; Nachon, 2004; Zerrai, 2006, 2010; Chang, 2009; Zghibi, 2009, 2010, 2012). These studies have emphasized the importance of verbalization in the teaching/learning process. It is in this context that this study seeks to identify the implemen- tation of action projects developed by pupils in discursive con- text. “If the Tunisian cultural model naturally assigns roles and hierarchies within a given class, pupils can also reinterpret them according to the opportunities for personal enhancement and/or to the power relations during exchanges between peers. In the case of football, more specifically, the interpersonal relation- ships during the match will redefine, during the ball exchanges, actions and their effects, allowing thus during the dialogue and through dialogue a true co-construction of the collective action” (Zghibi, 2012: p. 7). In fact, any formulated wording conveys a definite meaning, obtained by combining the differ ent semantic meaning of the words that constitute it. These words are orga- nized according to strict well defined syntactic rules. Now how about the context? The intervention of the context, i.e. the situation in which the discourse is delivered, radically changes the logic of things, so much that the meaning produced by utterance situation takes over that of the first meaning in the beginning. This difference in meanings, between what is said and what is referred has been a study topic by pragmatics. Consequently this linguistic branch deals with the language elements whose meaning cannot be understood unless the context is known when “saying is doing” (Austin, 1970). In this research we will opt for an illustrative analysis of pu- pil’s discourse during a football cycle, based on discursive ex- amples and which would be done through two conversational analyses: a hierarchical analysis and functional analysis. The objective is to identify qualitatively the pupil’s action project and then check whether quantitatively these projects are vali- dated or not. Methodology In our study we will look at two types of analyses, a qualita- tive and quantitative analyses of verbal outputs of the third year high school pupils who practice football within a civil club (Dahmani Athletic Club, League III, juniors, average age: 18 years). The research protocol proposed in this study consists in or- ganizing a series of a ten session football cycle lasting one ef- fective hour each (eight and a half hours of motor and verbal activity observed and recorded). The teaching process during these sessions will constitute an opportunity for pupils to ex- change ideas freely in order to build action projects. This will encourage pupils to try to find answers for the problems en- countered during the game. This study concerned 14 pupils Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 165  M. ZGHIBI ET AL. from the Dahmani high school. This choice finds its legitimacy in the fact that didactic studies acknowledge that at this level, the pupil is generally able to analyze, understand and especially to problematize independently from his teacher and thus par- ticipate in the knowledge construction process, by referring to the proposed situations and looking for means and ways to address the problems. This is part of the educational principle of Gréhaigne (1992) “understand to succeed” which allows the problematization of the difficulties encountered during action. The situations proposed are founded on a game situation, on a 40 m long and 20 m wide handball court. Each session (ses- sion unit) has two game situations (two games) under the con- trol of the teacher and separated by a five minute time sequence for the exchange of ideas (Gréhaigne et al., 1998) and always monitored by a specialist teacher in this field. In this research we are dealing with a purely descriptive analysis which seeks to convey the pupil’s language typologies through analysis models taken from the sciences of language (Roulet, 1981). The purpose of this experiment is to enable all pupils to take part in the knowledge building process, from situations experienced during the game. They are then re- quested to analyze and understand what is happening during the play situation, to build a plan of action and check whether the project is actually applied in the field or not. Pupils play for ten minutes and then they talk for five minu- tes before they resume the game (10 minutes) to execute the action plan decided by each team. During the verbalization sequences, pupils discuss their proposed action project to solve the problems experienced in the first game situation, discus- sions and debating ideas enable learners to negotiate the mean- ing of the game actions. The second situation seeks to deter- mine whether the proposed action is executed or not. The situa- tion of ideas debating is organized in order to allow pupils to exchange intentions concerning the action, orally (Chang, 2009). In this study, we will opt for two types of analyses: a qualitative analysis interested in how the exchange of ideas took place and a quantitative analysis to check the execution and implementation of such an action project. In other words, we will check whether this project will be implemented or not in the second game situation. This tool was developed to assess the correlation of forces and powers in football in order to have a better description of the evolution of adversarial relationships. These indices are as follows: the game volume, (total number of balls played), defensive capabilities (balls taken away from the opponent), adaptation to the game (number of lost balls), player’s offensive capabilities (penalties) and efficiency index (goals scored) (Gréhaigne, Billiards, & Laroche, 1999). Finally, it should be noted that this analysis will concern the 1st, 4th and 8th sessions. This choice can be justified by the fact that we consider that three sessions are enough and allow us to identify such a discursive progress. Results The Qualitative Analysis, Description and Identification of Pupil’s Action Projects The results of this section highlight the production and ex- traction of action projects during the verbalization sequences. At this level we shall opt for a hierarchical and functional de- scription of the pupil’s verbal outputs (oral verbalization), and subsequently identify the team’s action project during each session. In addition, during the second played situation, pupils try to implement their plan of action which resulted from the debate. The goal is to measure the impact. Session 1 Team “A”: oral verbalization The discourse can be presented in the following Table 1 ac- cording to two types of analyses: hierarchical and functional. As shown in Table 1, for Camara, the team needs to change its game by increasing the marking of the opponent players and facilitating the ball exchanges. According to Charfi, what justi- fies the failure is the lack of connection between the offensive and defensive parts. He suggests a closer link between the two parts. A practical solution formulated later by Charfi consists in two incentives: one fosters a more emphasis on the midfield and the other one consists in keeping the ball longer. Dekker seems to be angry because of the excessive selfishness of play- ers who use individual game excessively. This is why, ac- cording to him, too, the solution is to increase the ball ex- Table 1. Hierarchical and functional analysis of the speech of Team “A”. Pupil’s name Discourse Hierarchical analysis Functional analysis Camara We do not call fo r the ball Language act (A1) Reproach/indicating a cause Charfi There is no link between attack and defence Someone must be in midfield We must keep the ball Intervention (I1) Remarking a cause Suggestion A practical solution Dekker Each one will play separately We give the ball to the closest c o-player and we u se short passesIntervention (I2) Explanatory observation Remediation proposa l Youssef We have lost concentra t ion A language act (A2) An explanation Med Ali We must concentrate more on positions in the field A language act (A3) A proposal Camara Lack of marking of the oppo n e n t t e a m A language act (A4) Observing a shortcoming Youssef We need a defender at the backfield and midfield player. We have to catch the ball in the o p p onent’s camp. B Intervention (I3) 2 team’s remediation propos- als Charfi I would like to insist on short passes A language act (A5) A proposal Camara We have to shoot the ball against opponents’ cage A language act (A6) A proposal Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 166  M. ZGHIBI ET AL. changes and to develop group collective automatisms. Youssef explains the lack of success by the loss of concentration during the game. Expanding Youssef’s explanation, Med Ali proposes the recovery of a better concentration and a better positioning of players on the field. Camara remarked an additional short- coming in the player’s performance. They are not marking the opponent team tightly. Adding to what his teammate Camara said, Youssef proposes placing a backfield defender and a game maker in the midfield in order to recover the ball in the oppo- nent’s camp and exert more pressure. For both of them, ball immediate catching and exerting pressure must be enhanced with exchanging short passes and crowned by shots towards the goal. This discourse can be presented as follows in the Figure 1. It should be noted that in this analysis we shall opt for the same legend: (A: Act of language, I: Intervention and E: Ex- change of words). During the conversational interaction, we have seen that most interventions are of propositional type. More statements are made in order to propose rules of action on short passes as well as ball retention. The proposals are made in one must do this or that” form, which means that the language act indicates an obligation made in the form of a proposal. Each speaker tries to impose himself discursively and impose his point of view to convince his teammates. The exchange dynamics show a different use of the form “I insist”. Therefore there is it sort of interaction seeking a certain tutelage or authority by most pupils during the collective action project construction process. This obligation which is formu- lated and repeated during this discourse reflects the need to study it. Session 4 Team “A”: oral verbalization The discourse presented in Table 2 would account for both analyzes: a hie rarchical and a functio nal. It is half-time now and Team “A” is leading about. As shown in Table 2, all players participate in the discursive exchange, dominated more or less by Camara, but Sami, Wissem and Charfi also produce interesting discourse acts. Camara, who appreciates the effort and concentration and the lead taking advantage, acknowledges however the squandering of shots, which were not made at the goal. He suggests tighter marking of the opponent players and exerting more pressure at the attack level. For Wissem, the most difficult task has been done, however the team needs to use the opportunities to score more goals. Dekker seems to nourish doubt about the efficiency of Mohamed Ali and therefore requests a defensive curtain in the midfield. Charfi suggests a better coordination between the attack and defense and encourages attackers to take more initia- tives to score more goals, an idea which seems to be shared by Mohamed Ali who insists on the importance of good position- ing in the field. This discourse can be analyzed as displayed in Figure 2. The results of the sequence presented in Figure 2 demon- strate a richer exchange, where the majority of players inter- vene either by identifying problems or making solution propos- als. Indeed, some pupils underscore the lack of efficiency due to missed shots. The other pupils tend to make solution sugges- tions, namely a stronger defense and more attacks. Session 8 Team “A”: Oral Verbalization The discourse presented in Table 3 would account for both analyzes: a hie rarchical and a functio nal. The team was again victorious. Players are pleased to have provided a good performance thanks to the effort of Youssef who played collectively and thus relaunched and boosted the game (Testimony by Dekker and Camara). But, as shown in the Table 3, Med Ali advises a more rapid game with more calls for the ball. Camara suggests reducing ball retention in the midfield and playing short passes with the nearest team mate. This can be illustrated as presented in the Figure 3. The discussion of the pupils shows a certain satisfaction with regard to the score during the first game situation; however this does not prevent the existence of some problems. For that rea- son, pupils have decided to keep the ball longer. Quantitative Analysis: Checking the Implementation of Team “A” Pupil’s Action Projects This section focuses on the quantitative verification of the implementation of the action plans developed by the boys. To do this, we have opted for an observation table that shows five parameters namely: the game volume (total number of balls played), defensive capabilities (balls taken away from the Problems Proposals Action project Short passes and balls retention A1 A2 A4 A3 A5 A6 I1 I2 I3 Figure 1. Pupils’ action project during session 1 (team 1). Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 167  M. ZGHIBI ET AL. Table 2. Hierarchical and functional analysis of Team “A” pupils’ d isc ourse. Pupil’s name Discourse Hierarchical analysis Functional analysis Camara We have to mark opponent players Langu a g e a c t (A1) Proposal Med Ali I insist on the good position in the field Language act (A2) Proposal Sami How did we play? An attacker and the others play a dual role. (Defence and attack) Language act (A3) Proposal Camara This is the first time that we concentrate and won Many shots are not o n target Intervention (I1) Positive observation Negative observation Wissem The most difficult has been done but not th e easiest. We couldn’t score because of the cage Language act (A4) Observation Charfi In front of the cage players must take the initiative and score goals Language act (A5) Proposal Camara For me, I took the ba l l w i t h t h e c a g e behind me and I needed to pass on the ball to Sami Intervention (I2) Justification Dekker Dali is not in an attacking position Language act (A6) Criticism Charfi We continue the same way with a defence block Language act (A7) Proposal Med Ali We block the mid-fie ld player Language a c t (A8) Proposal Dekker A defensive wall in the midfield Language act (A9) Proposal Camara We need to exert more pressure at the attack level 3 in the midfield attempts to hamper the movement of the ball betw ee n the opposite team players. Intervention (I3) 3 proposals Sami Same formation Language act (A10) Proposal Charfi Coordination between at tack and defence Language act (A11) Proposal Problems Proposals Action p roject Double role playing (attack and defense) A1 A2 A4 A3 A5 A6 I1 I2 I3 Figure 2. Pupils’ action proje cts during session 4 (Team “A”). Problems Proposals Action pr oj ec t Keeping the longer ball retention A1 A2 A4 A3 A5 11 I2 I3 Figure 3. Pupils’ action project for session 8 (Team “A”). Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 168  M. ZGHIBI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 169 Table 3. Hierarchical and functional analyses of the Team “A” pupils’ discourse. Pupil’s name Discourse Hierarchical analysis Functional analysis Dekker The game im proved when Youssef played collectively Language act (A1) Positive observation Charfi A good passing aroun d of the ball Language act (A2) Positive observation Camara When Youssef received the b a ll , he improved the game We played slowly but surely Intervention (I1) 2 positive o b servations Youssef Goo d , we have to keep playing like this Language act (A3) Encouragement Sami We shot at the goal twice and we scored a goal Language act (A4) Positive observation Med Ali The game m ust be quicker, we h ave to m a ke m ore calls for the b allIntervention (I2) Proposal Camara We have to reduce ba ll retention You have to pass on the ball to the nearest teammate Intervention (I3) 2 proposals Dekker Sami is too far backwar d Language act (A5) Negative observation opponent players), adaptation to the game (number of lost balls) offensive capabilities of the players (penalties) and the index of efficiency (goals scored) (Gréhaigne, Billiards, & Laroche, 1999). It should be noted in this regard that the verification of pu- pil’s actions projects will be independent of the meaning of any statistical processing. This choice can be justified by the fact that the objective is not to prove such a statistically significant difference before/after verbalization for such a setting. But the goal is, rather, to follow descriptively, the quantitative progress of this game indicator (Zerrai, 2010). For example, if the pu- pils’ action project is to increase the number of shots and they manage to make a second shot during the second situation, when compared with the second situation; the action project is thus deemed to be valid. Figure 4. Presents the verification of the Team “A” pupils’ action project, in terms of played balls. Session 1 Figure 4 presents the verification of the Team “A” pupils’ action project, in terms of played balls. The results presented in Figure 4, shown that the number of balls played before the verbalization sequence is (16). After this sequence, it goes down to (15). The proposed action (increasing the number of played balls) already stated by pupils is not thus reached. Session 4 Figure 5 presents the verification of Team “A” pupils’ action project, in terms of balls played and balls taken away from the opponents. If we look at the histogram of the two games, we will note that the number of balls played before this verbalization se- quence is (16), it goes up to (20). As shown in the Figure 5, the number of balls taken away from the opponents after this se- quence of verbalization (11) is below of the one recorded be- fore (17). Thus, the action project regarding increasing the number of played balls has been implemented whereas one concerning the balls taken away from the opponents has not been implemented yet. For that reason, the implementation of the pupils’ collective action project is incomplete and therefore not validated. Figure 5. Verification of Team “A” pupils’ action project, in terms of balls play- ed and balls taken away from the opponents. that the number of balls played before the verbalization se- quence is (32). After the sequence, it goes up to (39). Therefore, the pupils have implemented the collective action project. Session 8 Discussion Figure 6 presents the verification of the Team “A” pupils’ action project, in terms of played balls. Regarding the extraction of the problems to be solved during the latest matches, it should be noted that Team “A” verbaliza- tion has been implemented. Consequently, at the beginning of The above shown diagram shows a difference between the values collected before and after the pupils’ discourse. We note  M. ZGHIBI ET AL. Figure 6. Verification of the Team “A” pupils’ action project, in terms of played balls. the debate cycle the players have often encountered tremendous difficulties in implementing the action projects. The proposals used by the players show an oppositional relationship, in terms of targets, reasoning, and authoritative suggestions. In other words this consists in making a hypothesis about actions during the verbalization sequences and then trying to validate them during the second game situation. The sequence of ideas dis- cussion allows the pupils to have an exchange of ideas and points of view, to express their opinions and to explain their reasoning and the constraints facing the action project and which becomes a tangible reality during the game (Chang, 2009). This evolution can be explained by the awareness about the encountered problems. The importance of the pupil’s dis- course emerges during the implementation of the decisions which have already been taken during the verbalization se- quence. Thus, the players produce language acts so that, later on, they could give a certain meaning to the game. At the end of the cycle, Team “A” becomes more capable to take into consideration the way the opponent team is playing and then suggests adequate technical and tactical solutions to face up the means and capacities of the opponent team. How- ever, the presence of the opponent players, as a problem, emerges in all the verbalization sequences. This proves that the players of this team can indeed take into consideration the op- ponent’s intentionality. The semio-constructivist approach gi- ves importance to the process by which the learner can co-construct his knowledge and actions from his personal ex- perience. Indeed, through these sequences the players try to think about their past experience, to negotiate available solu- tions, and to deconstruct the action rules in the form of action projects, and to implement them during the second game situa- tion. The implementation of the action projects during the latest session could be explained by the fact that the pupils have woven new relationships with their teammates. These relations are founded on a certain understanding which translates into an action project that could be implemented (Lave, & Wenger, 1991). Debating ideas helps players to better manage the informa- tion. It can therefore be concluded that the pupils do not learn by mere chance and that they do not learn passively what others teach them. Learning is the result of experience: it is all- the-more easier when this experience is sought deliberately and systematically by the learner himself. Debating ideas consists, therefore, in a certain interaction between what we personally think and what others think. The match situation underscores the difficulty for one individual player’s decision to make choices and conceive the most adequate response whenever the problematic situation is not familiar or predictable. This makes pupils exchange ideas, which leads to a modification of cogni- tive structures. Language processes promote awareness and the emergence of effective action plans. Thus, learning becomes more predictable and later there will be a better adequacy be- tween responses and the game situation. The interaction between learning and exchange of ideas is of a dynamic nature. It could be suggested that each time we make exchanges; we are more motivated to learn. In other words, the debate of ideas is a process that seeks to help resolve problems. The construction of new knowledge is the result of a long history of interaction between the different responses to prob- lematic situations triggered by the game and action plans en- visaged during verbalization. The interaction between pupils seems to produce the development and modification of indi- vidual representations. By better managing the organization of what we know, we can indefinitely enrich our ability to solve a problem, such as a better understanding and interpreting during the exchange of the ball, the ball pass distance, directions change, and position of the opponent player. If tactical skills are built, partly thanks to these cognitive means, verbal interactions between peers obviously help their development. The analysis of the discourse during the debate of ideas could help pupils better understand whether the proposals are likely to be successful or be doomed to failure. Thus, pupils learn how to define these learning objectives and to have reasonable expec- tations about what they can accomplish. However while learn- ing, pupils do not need to be told what they must do during the game. Learning the game act, along with the emergence of action projects, contributes to the pupil’s cognitive develop- ment, especially in the construction of a well-structured think- ing. Conclusion Linking ideas to action provides researchers with many re- search perspectives about the teaching/learning process. In the current study, players are faced with an adversarial relationship in the form of reduced games where they are called upon to solve a cascade of problems and to make the determining ur- gent decisions. Knowledge consists first of all in being capable to use and explore what we have learned and to mobilize it in order to overcome the encountered problems (Giordan, 1987). It is actually the confrontation of points of view, when debating ideas, which allows the emergence of proposals (rules of action) which are conducive to know-how that translates into efficient action projects. We have observed that the debate of ideas is a means which allows a comparison between individual interpretation and a group interpretation in order to take a collective decision. The execution of this decision was materialized mainly at the end of the cycle, especially during the last session. Following the qualitative and quantitative analyses we can say that the first Team “A” which has benefited from an oral verbal teaching shows a certain progress in the implementation of action pro- jects. However, this progress remains rather limited when the pupils’ language interactions are proportional to the encoun- tered difficulties in the beginning of the game. If we seek a higher level, such as the individual and/or collective tactical construction, triggering uncertainty in the mind of the oppo- Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 170  M. ZGHIBI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 171 nents, or the rapid management of time and space information, we have to resort to ideas debating. Indeed, during this learning cycle we noticed that pupils who used verbalization and a de- bate of ideas have shown a real progress. This is reflected in the immediate change of the game strategy, the rapid game reversal, and in the more developed analysis of the context. So, the play- ers have gone beyond a first level to a higher and even more consistent level in terms of game parameters (played balls, balls taken away from the opponents, number of shots and goals scored). This can also be justified by the number of projects implemented by the pupils during the last three sessions. Thus, this study of discursive productions highlights the importance of verbalization in the football teaching/learning system in Tu- nisia. Finally, it should be noted that this modest work will have the merit of proving the importance of discursive skills and the ability of pupils to co-construct their own knowledge of the game. This study is also a first attempt to find a fairly recent axis, although rather complex, namely the constructivist semi- otic paradigm. Indeed, this work has involved the sharing of knowledge in the field of physical activities and sport and theoretical background related to semiotics and linguistics. It is therefore an innovative approach in didactics in the Tunisian physical and sports education in particular in collective team sports. It is a teaching approach that uses verbalization. We hope that we have paved the way for other studies to examine the effect of this teaching approach with verbalization on other types of team sports (handball, basketball... etc.). These results should be closely linked to the notion of “communication contract”. Indeed, in every act of communica- tion partners understand and interact with each other to validate what is meaningful to them, namely “the collective intentions” (Searle, 1991), “joint intentionality” (Sensevy, 2008) and “ne- gotiation” (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 1984). REFERENCES Austin, J. L. (1970). When saying is doing. Paris: Seuil. Chang, C.-W. (2009). Language, thought and action: Semio-construc- tivist approach in basket-ball game learning among CM2 (5th grade) pupils. Doctorate Thesis, Besançon: University of Franche-Comté. Gréhaigne, J.-F. (1992). Game organization on f ootball. Paris: ACTIO. Gréhaigne, J.-F., Billard, M., & Laroche, J.-Y. (1999). Collective sports teaching at school.Conception, construction, evaluation. Bruxelles: De Boeck. Gréhaigne, J. F. et al. ( 2 00 1 ). The teaching and learning of decision ma- king in team sports. Quest, 53, 59-76. Giordan, A. (1998). Learn! Paris: Belin. Kerbert-Orcchioni, C. (1984). The conversational negotiations (pp. 223-243). Verbum. T. VII. Nancy: Nancy: Nancy University Press. Lave, J., & Wenger. E. (1990). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cmbridge: Cambridge University Press. a Mahut. B. (2003). Semiotic approach of didactic interactions: Gesture and verb in a PSE ituation. Besançon: University of Franche-Comté. s Nachon, M. (2004). Interaction on physical and sportive education: The case of Basketball. Semio-linguistics kills approach and know- ledge construction. Thesis, University of Franche-comté. Roulet, E. (1981). Exchanges, interventions and language acts in the conversation’s st ructure. Applied linguist ics studies, 44, 7-39. Roulet, E. et al. (1987). The articulation ofdiscourse on contemporary French. Peter Lang. Searle, J. R. (1991). Collective intentionality. In H. Parreth (Ed.), Com- munity on speech (p p. 277-243). Li è ge: Mardag a. Sensevy, G. (2008). Comparative didactics. In Education’s dictionary. Paris: PUF. Zghibi, M., Zerai, Z. & Rezig, M. (2009). Verbalization’s direct effects on action’s strategies and decision makings among pupils at a foot- ball cycle. Journal of research about the intervention on physical and sportive education, 16 , 118-140. Zerai, Z. (2006). How do girls learnthe handball? The contribution of verbalization. Master’s Thesis, Tunis: ISEFC. Zerai, Z. (2010). Handball learning among Tunisian and French girls: Contribution of verbalization. Doctorate Thesis, Besançon: Univer- sity of Franche-Comté. Zghibi, M. (2010). Linguistic interactions and learning on football. Thesis, European University. |