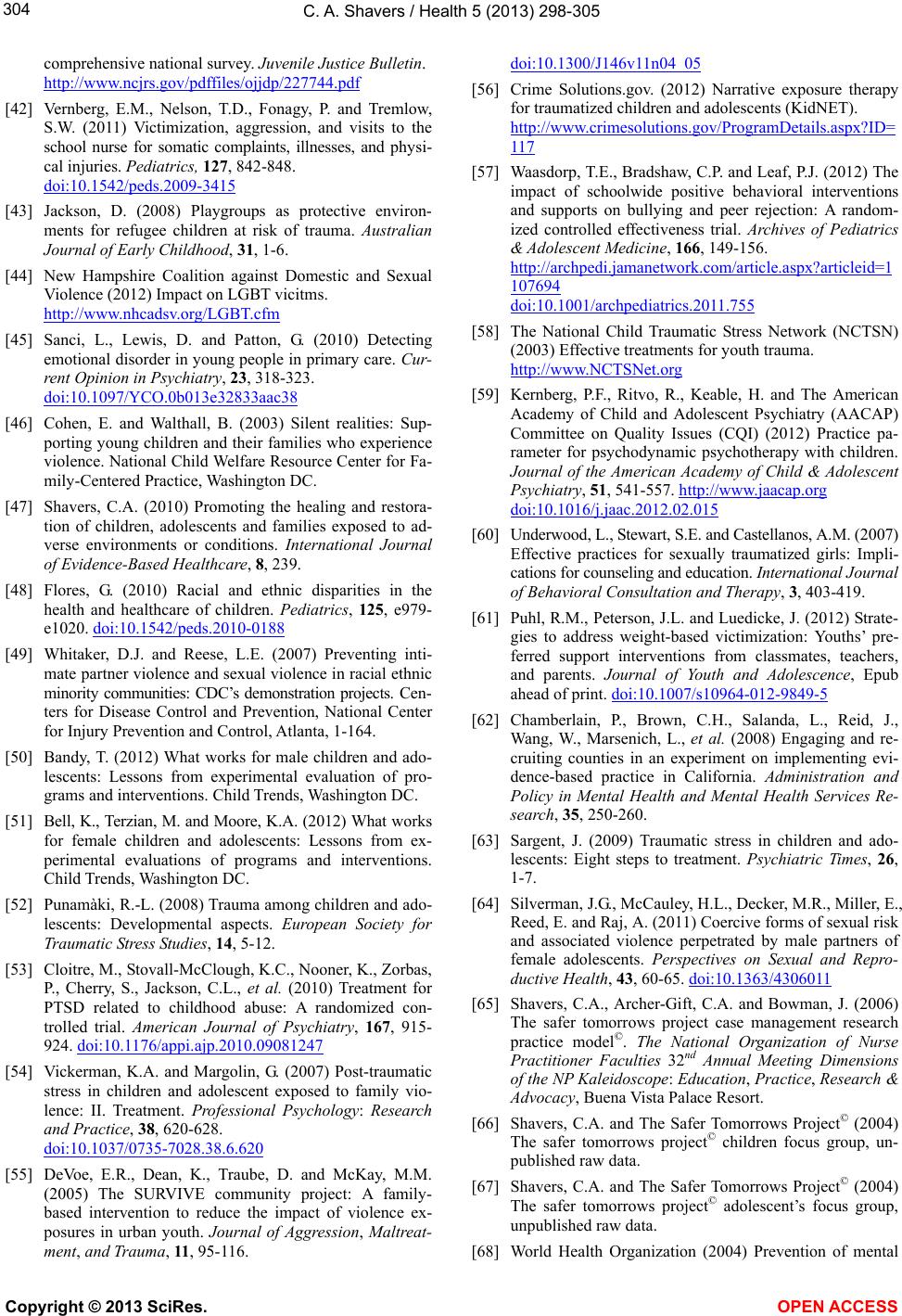

Vol.5, No.2, 298-305 (2013) Health http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/health.2013.52040 Exposures to violence and trauma among children and adolescents Clarissa Agee Shavers The Safer Tomorrows: Injury Prevention and Violence Reduction Project©, Primary Care Office, Detroit, USA; ageeclar@gmail.com Received 18 December 2012; revised 17 January 2013; accepted 24 January 2013 ABSTRACT Children and adolescents (youth) may be ex- posed to various forms of violence and trauma in a number of ways. Research and clinical stud- ies have revealed that youth may be signifi- cantly impacted by isolated, single or repetitive exposures to violence and trauma. Further, these exposures may ultimately impact the overall psycho-social-emotional, and mental health, as well as, the ment al health care of this population of youth who self-report, who are at-risk and who may or may not be at risk for exposure to violence and trauma in their lives. Thus, con- sequently, health care providers (HCP’s) w ho do not view or understand that exposures to vio- lence and trauma among youth, as well as, ex- posures to adverse environments or situations may pose as a serious or potential psycho- social-emotional and mental health care con- sequence for this population of youth may in- advertently impede or delay timely access to appropriate health care for this population. Hence, as a consequence of this delay in timely access to appropriate psycho-social-emotional and mental health care services for this popula- tion of youth, may significantly compromise their overall psycho-social-emotional and men- tal health care status. This article reviews the impact of exposures to violence and trauma among youth, with a focus on current empirical findings noted in the literature regarding vic- timized and traumatized children and adoles- cents, and the implications of these findings in promoting the healing and restoration for this population of youth for HCP’s. In addition, a brief discussion of an empirical evidence-based psycho-social-emotional intervention/project re- ferred to as The Safer Tomorrows: Injury Pre- vention and Violence Reduction Project© which has been designed for children and adolescents who may or may not be at-risk for exposures to violence and trauma is presented. The impor- tance of early identification, screening, assess- ment and treatment among victimized and trau- matized children and adolescents are also ad- dressed. Keywords: Violence; Trauma; Children; Adolescents; Prevention 1. INTRODUCTION Sorrowfully today, millions of children and adoles- cents (youth) in the world reside in neighborhoods or communities where violence or acts related to various forms of violence and trauma occur daily and millions more have been deemed to be at-risk [1-6]. Also, youth exposed to violence and trauma may exhibit adverse psycho-social-emotional, mental, and physical health care problems [5-9]. Research has shown that youth who have experienced directly, indirectly or even witnessing including being a stand-byer of violent or traumatic events may be at-risk for psycho-social-emotional and mental health issues of varying degrees and intensities [9-12]. Similarly, children and adolescents exposed to violence and trauma may b e at-risk for exposure to sexu- ally transmitted infections including chlamydia, gonor- rhea, human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and numerous other adverse conditions or situations including rape and sex- ual abuse [3,13-15]. For these reasons, HCP’s engaged or employed in di- verse ethnic-cultural, geographic, and socioeconomic communities are in a key position to confront and at- tempt to effectively assist children and adolescents who have self-reported actual, previous or past, and who are at-risk and who may or may not be at-risk for exposure to trauma and violence [1,3,8,9]. Likewise, the literature has shown that proactive attitudes of HCP’s and others can also significantly influence access to psycho-social- emotional and mental health services for children and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 299 adolescents residing in adverse or volatile environments, conditions, or situations [16,17]. Moreover, effective out- of-school or after-school evidence-based violence and trauma prevention interventions utilized by HCP’s and others have been found to be beneficial in promoting the psycho-social-e motional and mental health well-being of children and adolescents who may have been actual or potential victims, survivors, bystanders, perpetrators or rescuers in relations to exposures of violence and trauma [18-21]. Thus, the purpose of this paper is three-fold: 1) Pro- vide a succinct overview of the background and scope of the problem pertaining to exposures of violence and trauma among children and adolescents (youth). 2) To highlight some of the challenges and issues that may be encountered or associated with providing psycho-social- emotional and mental health care including clinical ser- vices by HCP’s for children and adolescents who self- report or identify a need for assistance as a result of ac- tual, past or previous, and potential exposures to violence and trauma. 3) Briefly discuss the development of an evidence-based intervention/project referred to as The Safer Tomorrows Project: Injury Prevention and Vio- lence Reduction Project© designed by multidisciplinary HCP’s and interdisciplinary professionals for children and adolescents (youth) who self-report, who are at-risk and who may or may not be at-risk for exposures to vio- lence and trauma. 2. BACKGROUND AND SCOPE OF PROBLEM An alarming increase in the prevalence of violence and trauma in the world has led to a serious pressing global health care concern for the safety and overall well-being of children and adolescents who self-report exposures to violence and trauma [4,5,22,23]. Even more disconcerting, emerging evidence suggest that isolated, acute, repetitive or chronic exposure including poly-vic- timization to violence and trauma may have a profound impact on children and adolescents physical, psycho- social-emotional, and mental health well-being [24-27]. Similarly, sexual violence or assault agains t children and adolescents is a sober health care concern as well due to the risk of adverse responses including the risk of suicide [28]. However, not all children and adolescents may ex- perience serious or adverse effects as a result of expo- sures to violence and trauma for a number of reasons including protective factors such as strong family support and resilience [2,22,29-36]. Yet, in still, the literature continues to acknowledge that globally many recognized or unrecognized victimized and traumatized youth are psycho-socially-emotionally and mentally adversely im- pacted from exposures to violent and traumatic events and reflect a need for preventive and early mental health intervention or treatment [22,29-34,37]. Additionally, research has revealed that thousands of children and adolescents are openly discussing the nega- tive impact of these adverse exposures of violence and trauma on their daily lives including bullying [2,37-41]. In fact, several studies involving youth self-reports of exposures to various forms of violence and trauma have identified that these youth experience a variety of stress- ors including at home and school, various types of bul- lying, a lack of effective coping strategies, and meaning- ful adult support for dealing with the issues surrounding exposures to violence and trauma in their young lives [2,37-41]. Equally HCP’s and others are encouraged by society and today’s youth to be more keenly aware of the existence, nature, and real life dynamics of relationships among youth that include acts of bullying and cyberbul- lying, dating violence, witnessing DV or IPV and family violence as reported or non-by the youth under their care or guidance [5,15,38,40]. So therefore, HCP’s and others are being advised to early identify, screen, treat, and in- corporate evidence-based prevention and health promo- tion interventions to assist in decreasing or eliminating the actual or potential adv erse impact of youth exposures to various forms of violence and traumatic events [5,17, 21,22,39,40]. 3. PROVISION OF SERVICES: CHALLENGES AND ISSUES FOR HCP’s As previously cited, it is important to note that chil- dren and adolescents may experience feelings of anger, anxiety, depression, social isolation and helplessness as a result of being exposed to violence and trauma [7,25, 30,31]. Also, youth victims and survivors of violence and trauma may develop severe mental health problems in- cluding depression and suicide ideation [2,37-41]. Fur- thermore, while not all youth exposed to violence and trauma may need mental health services to effectively deal with the psycho-social-emotional and mental after- math of victimization, there are still many children and adolescents who may need specialized mental health care services to help them heal from these violent or traumatic events [34,42]. Hence, it is imperative that HCP’s recog- nize signs and/or symptoms of psycho-social-emotional, physical and mental trauma in a concerted effort to make appropriate and timely referrals to psycho-social-emo- tional and mental health providers or health service sys- tems for victimized and traumatized youth [34,43,44]. However, access to community based psycho-social- emotional and mental health services or resources con- tinues to be an issue for many victims and survivors of violence and trauma especially those who are residing in Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 300 volatile or traumatic environments, the under or unin- sured, poor and minorities or people of color, children and adolescents [8,15,37,45-47]. As a result, this may significantly impact the efforts of HCP’s seeking to id en- tify, as well as, to make appropriate and timely referrals to community-based psycho -social-emotional and mental health providers or health care systems on behalf of this population of children and adolescents. Moreover, sub- stantial populations of victimized and traumatized chil- dren and adolescents may still not be reached. For re- search has shown that many community-based organiza- tions or facilities which p rovide psycho-social-emotional and mental health services may either 1) not have a suf- ficient range of multid isciplinary services includ ing wrap- around services or 2) funds to meet the diverse needs of youth victims of violence and trauma [22,30,31]. Thus, it is imperative that HCP’s must continue to address and confront these issues in order to promote the healing and restoration of this population of children an d adolescents [47]. Furthermore, HCP’s must keep in mind that less se- vere psycho-social-emotional or mental health care pro- blems including mental illness must be understood in a developmental, ethnic, linguistic, social and cultural con- text in order to meet the health care needs of diverse po- pulations (i.e. victimized and traumatized children or adolescents) [1,48-52]. Also, mental health services must be designed and delivered in a manner by HCP’s that is sensitive to the persp ectives an d needs of racial or p eople of color, and other vulnerable populations including vic- timized or traumatized youth [1,48,49,52]. Nevertheless, there are numerous reported evidence-based interven- tions (i.e. individual-level and group-level risk reduction interventions) that have been proven to be effective and efficacious in the clinical, school, and community-based settings including the systems approach to intervention which may involve working with social services agencies, phase-based skills-to-exposure treatment, case manage- ment, individual and group cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and a combination of optimal medication man- agement regimens with psychosocial interventions [53- 60]. What’s more promisingly, research has shown that evidence-based interventions and treatment models in and out-of-school, as well as, community-based settings including adolescent clinics may prove to be effective in improving the qu ality of services provided for v ictimized and traumatized youth as well [29,61-64]. 4. THE SAFER TOMORROWS: INJURY PREVENTION AND VIOLENCE REDUCTION PROJECT© Thus, in response to the call to assist, build on prior research, and meet the needs of this vulnerable popula- tion of children and adolescents, The Safer Tomorrows: Injury Prevention and Violence Reduction Project©, an evidence-based randomized controlled psycho-social- emotional intervention/project was formally created in 2002 [1,3,16,4 7] . Prese ntly, The Sa fer Tomorrows: I njur y Prevention and Violence Reduction Project© (also re- ferred to as The Safer Tomorrows Project©) in collabora- tion with the Primary Care Office, New Center Commu- nity Mental Health Services, the Michigan Department of Community Health, as well as with other Partners, Volunteers, Collaborating Agencies and Organizations, is presently identifying children and adolescents at-risk for exposure to violence and trauma. This multi-phase and multi-level evidence-based randomized controlled psy- cho-social-emotional intervention/project presently in- volves children, adolescents, parents, teachers, multidis- ciplinary health care providers, interdisciplinary commu- nity-based professionals or providers, and volunteers in the United States of America (USA), Canada, West In- dies Caribbean Trinidad and Tobago. Similarly, the proposed evidence-based 10 week out- of-school and community-based structured curriculum (designed for future implementation during Phase II of The Safer Tomorrows Project©) includes an educational model which focuses on the themes of violence and trauma, injury prevention, and global healthy peaceful conflict resolutions or strategies. In addition, presently, the evidence-based structured curriculum is primarily de- signed for children (pre-teen) aged 8-to-12, or in grades four, five, and six, who have previously or in the past self reported actual or potential exposures to 1) community violence, interpersonal violence, intimate partner vio- lence; 2) trauma; 3) intentional injuries as a result of violence or acts related to violence (e.g. bullying, physi- cal fighting); and 4) unintentional or non-fatal mild traumatic brain injuries (TBI) such as those sustained from sports or aggressive physical contacts, falls from bicycles or skateboarding, pellet guns or firearms. Also, this evidence-based curriculum focuses on a variety of topics (i.e. anger management, bullying) and includes strong connections to the existing educational research based on injury prevention, violence reduction or pre- vention, and global healthy peaceful conflict resolution interventions or strategies for elementary school-aged children. Hence, The Safer Tomorrows Project© has been de- signed to address intervention at various levels for indi- viduals (children and adolescents or youth), families (parents/guardians/primary caregivers), and communities (including teachers and multidisciplinary health care pro- viders) and can be used to individualize the unique needs of each child, adolescent, family, and community. Like- wise, we plan to proactively promote the healing and restoration of this population of children an d adolescents with the use of The Safer Tomorrows Project Case Man- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 301 agement Research Practice Model© [65]. In brief, this evidence-based model consists of a structured format which addresses the issues of 1) safety nets for children and adolescents, 2) access to services, resources, and programs, 3) coordination of services with local multi- disciplinary and interdisciplinary providers or profes- sionals and volunteers, and 4) global health education around the themes of evidence-based injury prevention, violence reduction, and healthy peaceful conflict resolu- tions or strategies [65]. Furthermore, we plan to em- power children and adolescents to effectively address the issues of violence and trauma with the use of The Child- hood Violence Trauma Reduction Model© (see Figure 1) [2,37]. The theoretical constructs for The Childh ood Violence Trauma Reduction Model©, an empirical model (see Figure 1) were derived from an extensive literature re- view, as well as, empirical evidence obtained from se- veral research studies conducted by Shavers and/or in collaboration with other investigators over several years time span which included children, adolescents, par- ent/guardians/caregivers, teachers, multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary professionals or providers, and volun- teers as human participants [2,37,15,16]. In quintessence, the majority of the significant findings from Shavers and/or other colleagues empirical studies revealed that self-reports of various exposures to violence and trauma by the children and ado lescent particip ants assisted in the further development of the evidence-based derived theo- retical constructs and the hypothesized conceptual map- ping noted in Figure 1 [2,15,16,37]. Likewise, many of the significant findings or data collected from the self- report instruments utilized by Shavers and/or other col- leagues identified youth participant self-reports of none to mild-moderate-severe psycho-social-emotional and mental health symptomatology as a result of self-reports of exposures to various forms or related acts of violence and trauma among the hu man research particip ants [2 ,15, 16,37,66,67]. Also, in the studies conducted by Shavers and/or in collaboration with colleagues revealed that the children participants who self-reported exposures to in- timate partner violence (IPV) or domestic violence (DV), often self-reported feelings of anger or mad, and fear [15,37]. In addition, notably, many of the children par- ticipants who self-reported exposures to DV or IPV also revealed feelings of sadness [15,37]. Further, preliminary findings from The Safer Tomorrows Project© pilot of the Focus Group process co nducted in 200 4 revealed th at the adolescent participants reported a higher rate of expo- sures to various acts of violence and trauma versus the children participants [66,67]. Congruently, the hypothesized theoretical and con- ceptual mapping of The Childhood Violence Trauma Reduction Model© presently utilized by The Safer To- *ECV *IPV Trauma Antecedent Childhood Traumatic Str e sso r(s) Including physical injuries PTSD None Mild Moderate Severe Emotional Respon se s Behavioral Patterns *CommunityLevel Vari ab l es Environment‐ Home/Community Fami ly Support Teachers Community Support/Resources *IndividualLevel Var i a bles ChildHealth Language Dev elo p men t a l OrLearning Disabilities (ADHD) Moderato r Vari a bl e s Ethnicity/Culture Gender Age Incom eLevel Peer Relation ships inschool Academic Performance Perf orma nce T HE CHILDHOOD VIO LE NCE TRAUMA REDUCT ION MODEL© Figure 1. Interrelationship of the concepts, mediator, con- founding, and moderator variables: A Hypothesized Conceptual Map© Shavers, C.A. (2000). The interrelationships of expo- sure to community violence and trauma to the behavioral pat- terns and academic performance among urban elementary school-aged children. Dissertation Abstracts International: Vol. 61(4-B), 1876. *Exposure to Community Violence, Interper- sonal Violence, Intimate Partner Violence (Domestic Abuse and Bullying); *Posttra umatic Stress Disorder (PTSD); *Community or County level variable (mediator variable); *Individual level variables (confounding variables). morrows Project Research Team© seen in Figure 1, in- corporates depicting the interrelations among the theo- retical concepts (constructs): 1) childhood exposure to community violence, interpersonal violence and IPV or DV including bullying, 2) trauma including physical in- juries, 3) the antecedent childhood traumatic stressor(s), 4) psychological responses, 5) emotional responses, 6) behavioral patterns, and 7) academic performance and peer relationships. Nonetheless, the investigators for The Safer Tomorrows Project© recognize the fact that no sin- gle risk or protective factor or combination of factors can predict the psychological, emotional, physiological, be- havioral or peer relationships in school, and academic performance with neither absolute accuracy nor linearity. So therefore, due to the nature of the intervention/proj ect, The Safer Tomorrows Project Research Team© decided to use a model/theory building approach with the inter- vention/project. Thus in essence, we have incorporated the utilization of The Childhood Violence Trauma Re- duction Model© in the designing of the intervention/ project in an effort to rigorously evaluate the effective- ness and efficacy of this evidence-based randomized controlled psycho-social-emotional intervention/project over a 10-year period on a local, national and interna- tional level. 5. SUMMARY In summary, childhood and adolescent adverse expo- sures to violence and trauma have been identified as a distressing health care problem for our society [4,8, 10,14]. The literature has noted that evidence-based Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 302 health promotion and prevention of violence and trauma- related interventions have been found to be effective in assisting youth who have been impacted from being ex- posed to various forms of violence and trauma [5,6,68]. HCP’s and others play a significant role in meeting the needs of children and adolescents who self-report expo- sures to violence and trauma [10,17,29,30]. Finally, in collaboration with other Partners, Volunteers, Collabo- rating Agencies and Organizati ons, The Safer Tomo rr ow s: Injury Prevention and Violence Reduction Project© is presently identifying children and adolescents who are at-risk and who may or may not be at-risk for exposure to violence and trauma in their lives to assist in the global efforts to address this persuasive health care pro- blem in our society [3]. 6. CONCLUSION Consequently, as a result of adverse exposures to vio- lence and trauma among children and adolescents, this may result in an unhealthy and vulnerable population of victimized and traumatized youth. However, there is a promisingly dearth of information that exists to assist adults, HCP’s and others in integrating, implementing and evaluating the utilization of appropriate physical, psycho-social-emotional, and mental health services for identified victimized and traumatized yo uth. Addition ally, it is imperative that HCP’s and others engaged or em- ployed in health care, schools or community-based set- tings be actively involved in all endeavors including health policy to promote the overall psycho-social- emotional and mental h ealth of all youth who self-report, who are at-risk and who may or may not be at-risk for exposures to violence and trauma in their young lives. Thus, hopefully these proactive endeavors on behalf of society’s youth will co ntribute to safer and health ier phy- sical, psycho-social-emotional, and mental health care trajectories for today, tomorrow, and the future genera- tion of children and adolescents. 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This article was supported by the Text and Academic Authors Asso- ciation Inc. (TAA) URL: http://www.taaonline.net/membersonly/publication_grants/index.html academic publication grant. Also, the author would like to especially acknowledge the following members of The Safer Tomorrows Project Research Team©: C. A. Archer-Gift, Ph.D., L. M. Green, M.A., L.L.P. C., L.B.S.W., J. E. Onyskiw, Ph. D., and M. Price, Ph.D. and all the mem- bers of The Safer To morrows Project© for their support and dedication to our mission and vision. REFERENCES [1] Shavers, C.A. (2009) Minimize the impact of violence for youth [commentary]. The Clinical Advisor: A Forum for Nurse Practitioners, 74, 4. [2] Shavers, C.A. (2000) The interrelationships of exposure to community violence and trauma to the behavioral pat- terns and academic performance among urban elementary school-aged children. D.N.Sc. Dissertation, The Catholic University of America, Washington DC. [3] Shavers, C.A. (2010) Promoting the health of children and adolescents exposed to trauma and violence [point of view]. http://www.primaryissues.org/pov/post1241885 [4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Sur- veillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Re- porting System. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61, 1-43. [5] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2011) The state of the world’s children 2011: Adolescence and age of opportunity. UNICEF, New York. [6] World Health Organization (2009) Violence prevention: The evidence. Worl d Hea l th Organization, Geneva. [7] Middlebrooks, J.S. and Audage, N.C. (2008) The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta. [8] McDonald, C.C. and Richmond, T.R. (2008). The rela- tionship between community violence exposure and mental health symptoms in urban adolescents. Journal of Psy- chiatric Mental Health Nursing, 10, 833-849. d oi:1 0.1111/ j.13 65-2850.2008.01321.x [9] NCTSN Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task- force (2012) The 12 core concepts: Concepts for under- standing traumatic stress responses in children and fami- lies. Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma, UCLA— Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, Los Angeles. [10] Garbarino, J., Bradshaw, C.P. and Vorrasi, J.A. (2002) Mitigating the effects of gun violence on children and youth. The Future of Children, 12, 73-85. http://www.primaryissues.org/2010/09/ [11] Lee, A.M.R. and Galynker, I.I. (2010) Violence in bipolar disorder: What role does childhood trauma play? Elec- tronic version. Psychiatric Times, 27, 1-7. [12] Children’s Defense Fund (2010) Protect children, not guns 2010. Children’s Defense Fund, Washington DC, 1- 24. [13] Wilson, H.W. and Widom, C.S. (2009) Sexually trans- mitted diseases among adults who had been abused and neglected as children: A 30 year prospective study. Ameri- can Journal of Public Health, 99, S197-S203. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.131599 [14] Turner, H.A., Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A. and Hamby, S. (2012) Recent victimization exposure and suicidal idea- tion in adolescents. Archive of Pediatric Adolescent Medi- cine (Online First), E1-E6. http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/ [15] Shavers, C.A., Levendosky, A.A., Dubay, S.M., Basu, A. and Jenei, J. (2005) Domestic violence research: Meth- odological issues related to a community-based interven- tion with a vulnerable population. Journal of Applied Bio- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 303 behavioral Research, 10, 27-38. d oi:1 0.1111/ j.17 51-9861.2005.tb00002.x [16] Shavers, C.A., Archer-Gift, C.A. and Onyskiw, J.E. (2007) Promoting the psycho-social-emotional health of children. 18th Annual Early Childhood Conference, Kalamazoo. [17] Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2008) Recommendations to reduce psychological harm from traumatic events among children and adolescents. Ameri- can Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 314-316. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.025 [18] Lawrence, A., Brown, J.L., Jones, S.M., Berg, J. and Tor- rente, C. (2011) School-based strategies to prevent vio- lence, trauma, and psychopathology: The challenges of going to scale. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 411-421. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000149 [19] Walton, M.A., Chermack, S.T., Shope, J.T., Bingham, C.R., Zimmerman, M.A., Blow, F.C. and Cunningham, R.M. (2010) Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: A ran- domized control trial. The Journal of the Medical Asso- ciation, 304, 527-535. [20] Wolfe, D.A. and Jaffe, P.G. (1999) Emerging strategies in the prevention of domestic violence. The Future of Chil- dren, 9, 133-144. doi:10.2307/1602787 [21] Valladares, S. and Ramos, M.F. (2011) Latino immigrants and out-of-school time programs. Child Trends, Wash- ington DC. [22] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2012) Pro- gress for children: A report card on adolescents. 10th Edi- tion, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), New York. http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Progress_for_chi ldren_-_No._10_EN_04232012.pdf [23] Hinduja, S. and Patchin, J.W. (2010) Cyberbullying: Iden- tification, prevention and response. Cyberbullying Re- search Center, 1-5. http://www.cyberbullying.us [24] Hodas, G.R. (2006) Responding to childhood trauma: The promise and practice of trauma informed care. Pennsyl- vania Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Ser- vices, Pennsylvania. [25] Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R.K. and Turner, H.A. (2007) Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child vic- timization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 7-26. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008 [26] Miller, R. (2007) Cumulative harm: A conceptual over- view. Best interests series. Victorian Government De- partment of Human Services, Victoria. [27] Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M. and Sprague, C. (2007) Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Focal Point, 21, 4-8. [28] American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) (2008) Child sexual abuse. Facts for Families©, 9, 1-2. [29] Aber, L., Brown, J.L., Jones, S.M., Berg, J. and Torrente, C. (2011) School-based strategies to prevent violence, trauma and psychopathology: The challenges of going to scale. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 411-421. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000149 [30] Adams, E.J. (2010) Healing invisible wounds: Why in- vesting in trauma-informed care for children makes sense. Justice Policy Institute, Washington DC. [31] Stagman, S. and Cooper, J.L. (2010) Children’s mental health: What every policymaker should know. The Na- tional Center for Children in Poverty (NCCP), New York. [32] Felitti, V., Anda, R., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse child- hood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Pre- ventive Medicine, 14, 245-257. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [33] Ybarra, M.L., Mitchell, K.J. and Korchmaros, J.D. (2011) National trends in exposure to and experiences of vio- lence on the internet among children. Pediatrics, 128, e1376-e1386. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/6/e1376. full.html doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0118 [34] American Psychological Association (APA) Presidential Task Force on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Trauma in Children and Adolescents (2008) Children and trauma: Update for mental health professionals. American Psy- chological Association, W ashington DC. http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/children-trauma -update.aspx [35] Edelson, J.L. (2006) Emerging responses to children ex- posed to domestic violence. VAWnet, a Project of the Na- tional Resource Center on Domestic Violence/Pennsyl- vania Coalition against Domestic Violence. http://www.vawnet.org/applied-research-papers/print-doc ument.php?doc_id=585 [36] Osofsky, J.D. (1995) Children who witness domestic vio- lence: The invisible victims. Social Policy Report: Society for Research in Child Development, IX, 1-16. http://www.srcd.org/documents/publications/SPR/spr9-3. pdf [37] Shavers, C.A. (2003) The interrelationships of exposure to intimate partner violence and trauma to the emotional responses and behavioral patterns among children re- stored at a rural safe haven. Michigan Council of Nurse Practitioners (MICNP) 2nd Annual Conference , Dearborn. [38] Carroll-Lind, J., Chapman, J. and Raskauskas, J. (2011) Children’s perceptions of violence: The nature, extent and impact of their experiences. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 37, 1-13. http://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-andour-work/publica- tions-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-jou rnal/spj37/02-Carroll-lind-et-al.pdf [39] Franchek-Roa, K.M. (2012) Childhood exposure to inti- mate partner violence. http://www.uptodate.com [40] Edelson, J.L., Nguyen, H.T. and Kimball, E. (2011) Honor our voices: A guide for practice when responding to chil- dren exposed to domestic violence. Minnesota Center against Violence and Abuse (MINCAVA), Minneapolis. http://www.honorourvoices.org/docs/Guideforp ractice.pdf [41] Finkelhor, D., Turner, J., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S. and Kracke, K. (2009) Children’s exposure to violence: A Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 304 comprehensive national survey. Juvenile Jus tice Bulletin . http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/ojjdp/227744.pdf [42] Vernberg, E.M., Nelson, T.D., Fonagy, P. and Tremlow, S.W. (2011) Victimization, aggression, and visits to the school nurse for somatic complaints, illnesses, and physi- cal injuries. Pediatrics, 127, 842-848. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3415 [43] Jackson, D. (2008) Playgroups as protective environ- ments for refugee children at risk of trauma. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 31, 1-6. [44] New Hampshire Coalition against Domestic and Sexual Violence (2012) Impact on LGBT vicitms. http://www.nhcadsv.org/LGBT.cfm [45] Sanci, L., Lewis, D. and Patton, G. (2010) Detecting emotional disorder in young people in primary care. Cur- rent Opinion in Psychiatry, 23, 318-323. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833aac38 [46] Cohen, E. and Walthall, B. (2003) Silent realities: Sup- porting young children and their families who experience violence. National Child Welfare Resource Center for Fa- mily-Centered Practice, Washington DC. [47] Shavers, C.A. (2010) Promoting the healing and restora- tion of children, adolescents and families exposed to ad- verse environments or conditions. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 8, 239. [48] Flores, G. (2010) Racial and ethnic disparities in the health and healthcare of children. Pediatrics, 125, e979- e1020. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0188 [49] Whitaker, D.J. and Reese, L.E. (2007) Preventing inti- mate partner violence and sexual violence in racial ethnic minority communities: CDC’s demonstration projects. Ce n- ters for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, 1-164. [50] Bandy, T. (2012) What works for male children and ado- lescents: Lessons from experimental evaluation of pro- grams and interventions. Child Trends, Washington DC. [51] Bell, K., Terzian, M. and Moore, K.A. (2012 ) What work s for female children and adolescents: Lessons from ex- perimental evaluations of programs and interventions. Child T rends, Wa shington DC. [52] Punamàki, R.-L. (2008) Trauma among children and ado- lescents: Developmental aspects. European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 14, 5-12. [53] Cloitre, M., Stovall-McClough, K.C., Nooner, K., Zorbas, P., Cherry, S., Jackson, C.L., et al. (2010) Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: A randomized con- trolled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 915- 924. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247 [54] Vickerman, K.A. and Margolin, G. (2007) Post-traumatic stress in children and adolescent exposed to family vio- lence: II. Treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 620-628. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.620 [55] DeVoe, E.R., Dean, K., Traube, D. and McKay, M.M. (2005) The SURVIVE community project: A family- based intervention to reduce the impact of violence ex- posures in urban youth. Journal of Aggression, Maltreat- ment, and Trauma, 11, 95-116. doi:10.1300/J146v11n04_05 [56] Crime Solutions.gov. (2012) Narrative exposure therapy for traumatized children and adolescents (KidNET). http://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID= 11 7 [57] Waasdorp, T.E., Bradshaw, C.P. and Leaf, P.J. (2012) The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: A random- ized controlled effectiveness trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166, 149-156. http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1 107694 doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.755 [58] The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) (2003) Effective treatments for youth trauma. http://www.NCTSNet.org [59] Kernberg, P.F., Ritvo, R., Keable, H. and The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI) (2012) Practice pa- rameter for psychodynamic psychotherapy with children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 541-557. http://www.jaacap.org doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.015 [60] Underwoo d, L., Stewart, S.E. and Castellanos , A .M. (2007) Effective practices for sexually traumatized girls: Impli- cations for counseling and education. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 3, 403-419. [61] Puhl, R.M., Peterson, J.L. and Luedicke, J. (2012) Strate- gies to address weight-based victimization: Youths’ pre- ferred support interventions from classmates, teachers, and parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9849-5 [62] Chamberlain, P., Brown, C.H., Salanda, L., Reid, J., Wang, W., Marsenich, L., et al. (2008) Engaging and re- cruiting counties in an experiment on implementing evi- dence-based practice in California. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Re- search, 35, 250-260. [63] Sargent, J. (2009) Traumatic stress in children and ado- lescents: Eight steps to treatment. Psychiatric Times, 26, 1-7. [64] Silverman, J.G., McCauley, H.L., Decker, M.R., Miller, E., Reed, E. and Raj, A. (2011) Coercive forms of sexual risk and associated violence perpetrated by male partners of female adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Repro- ductive Health, 43, 60-65. doi:10.1363/4306011 [65] Shavers, C.A., Archer-Gift, C.A. and Bowman, J. (2006) The safer tomorrows project case management research practice model©. The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties 32nd Annual Meeting Dimensions of the NP Kaleidoscope: Education, Practice, Research & Advocacy, Buena Vista Palace Resort. [66] Shavers, C.A. and The Safer Tomorrows Project© (2004) The safer tomorrows project© children focus group, un- published raw data. [67] Shavers, C.A. and The Safer Tomorrows Project© (2004) The safer tomorrows project© adolescent’s focus group, unpublished raw data. [68] World Health Organization (2004) Prevention of mental Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  C. A. Shavers / Health 5 (201 3) 298-305 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS 305 disorders: Effective interventions and policy options (sum- mary report). World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Collaboration with the Prevention Research Centre of the Universities of Nijmegen and Maastricht, Nijmegen, Maastricht.

|