Vol.5, No.2, 245-252 (2013) Health http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/health.2013.52033 Direct and indirect effects of multilevel factors on school-based physical activity among Japanese adolescent boys Li He1*, Kaori Ishii2, Ai Shibata2, Minoru Adachi3, Keiko Nonoue4,5, Koichiro Oka2 1Graduate School of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, Tokorozawa, Japan; *Corresponding Author: meethl@moegi.waseda.jp 2Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, Tokorozawa, Japan 3Graduate School of Education, Okayama University, Okayama, Japan 4Sonan Junior High School, Okayama, Japan 5Waseda Institute for Sport Sciences, Tokorozawa, Japan Received 26 October 2012; revised 25 November 2012; accepted 4 December 2012 ABSTRACT Purpose: Background: Physical activity is a complex behavior which involves the intera ctio n of multilevel factors at the individual, social and environmental level. However, previous studies have largely focused on psychological and/or social environmental factors and the direct im- pact of such factors on physical activity. There are few studies having examined how multilevel factors may interact to influence activity level. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine both direct and indirect effects of multilevel factors on school-based physical ac- tivity in Japanese adolescent boys. Methods: In this cross-sectional surv ey of the Japanese ado- lescent lifestyles, 379 junior high school boys were invited to complete self-r epor t measur es of age, grade, weight, height, self-efficacy, social support (family, friends and teachers), school physical environment (equipment, facilities and safety) and average minutes per week of phy- sical activity during lunch time and after-school hours occurring at school. Structural equation modeling analyses controlling for age were uti- lized to examine the effects of body mass index (BMI), self-efficacy, social support and school physical environmental variables on lunchtime and after-school physical activity. Results: Dur- ing lunch time, self-efficacy exhibited direct positive effects on physical activity. BMI, facili- ties, and safety were indirectly associated with lunchtime physi cal a ctivity through s elf -efficacy. However, there were no significant relationships of equipment and social support with lunchtime physical activity. During after-school hours, fa- mily support and facilities directly affected phy- sical activity. Self-efficacy was indirectly related with physical activity through family support. BMI, equipment, and safety indirectly affected physical activity through self-efficacy and/or family support. Conclusion: Effects of multilevel factor on physical activity among adolescent boys differed according to context, which im- plies that interventions to promote physical ac- tivity should be context-specific. Findings en- courage the development of future effective in- terventions to promote physical activity through self-efficacy during lunch time as well as family support during after-school hours. Keywords: Public Health; Physical Activity; Adolescents; Ecological Model; Structur al Equation Modeling 1. INTRODUCTION Regular physical activity during adolescence is known to have both short- and long-term health benefits [1,2]. However, participation in such activity declines dramati- cally during this period of development [3]. The majority of adolescents do not meet the recommended 60 min/day of physical activity [3,4]. Therefore, promoting their physical activity through successful interventions has been a high public health priority. Identifying modifiable correlates of physical activity behavior that could act as mediators is an important step in developing successful interventions. Mediators are the third variables in a causal path that explain how or why effects of initial variables on outcome variables occur [5]. However, the mediated (i.e., indirect) effects of corre- lates on physical activity remain poorly understood in regard to adolescents. Although the social ecological model suggests that physical activity behavior is ex- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 246 plained by the interaction of personal, social, and envi- ronmental factors [6], much research is limited to indi- viduals’ cognitions and perceptions of social environ- mental influences [7-12]. Few researchers have exam- ined both direct and indirect effects of multilevel factors on physical activity across personal, social, and envi- ronmental levels. In this respect, Motl et al. reported that the relations between perceived equipment accessibility at home and in the neighborhood, social support, and self-reported physical activity were accounted for by self-efficacy in adolescent girls [13,14]. In a study by Lubans et al. [15], while social support was not significantly related to physical activity in adolescent girls, school physical en- vironment was found to partially mediate the relation between self-efficacy and objective physical activity. However, those studies focused on overall physical ac- tivity level without distinguishing physical activity in different contexts, for example at school or out of school during after-school hours. As the ecological approach notes, behavior occurs in various “settings or contexts” (i.e., in certain places and at certain times). Thus, exam- ined behaviors should be specific to the relevant envi- ronment (i.e., neighborhood physical environment rele- vant to out-of-school activity; school physical environ- ment relevant to school-based physical activity) [16]. Moreover, in those studies, models were tailored for adolescent girls and did not reflect boys’ specific charac- teristics. Physical activity declines in boys as well as girls during adolescence, although boys are typically more active than girls [17]. Considering that boys and girls are no longer physically well-matched from early adolescence [18], personal, environmental, and beha- vioral characteristics might be unique to different gen- ders. Therefore, interventions targeting adolescent boys as well as girls should be guided by relevant theoretical models. Furthermore, such models provide evidence for targeting self-efficacy or physical environment as possi- ble mediators [13-15]. However, whether social support can account for the associations of self-efficacy and physical environment with physical activity is still un- known. School is an important setting for promoting adoles- cents’ physical activity at the population level. Students spend much of the day during the week at school and have many potential opportunities for daily physical ac- tivity there in addition to physical education class (e.g., break times, including lunch recess and after-school hours). A previous review reported that involvement in physical activity during such non-curricular school time contributes 5% - 40% of the recommended 60 minutes of daily physical activity [19]. However, an understanding of the effects of school environment on such physical activity is limited. Moreover, there are no studies that have comprehensively examined the effects of personal, social, and school physical environmental factors that impact such physical activity among adolescent boys. Consequently, the present study aimed to explore the direct and indirect effects of personal, social, and school physical environmental factors on non-curricular school- based physical activity among adolescent boys. The pri- mary hypothesis was that perceived social support would be a possible mediator of physical activity. The present model that tested effects of multilevel correlates on con- text-specific physical activity among adolescent boys can contribute to the systematic progression of physical ac- tivity research as well as the development of effective school-based interventions for boys. 2. METHODS 2.1. Participants and Data Collection The present study included data on 12 - 15-year-old adolescent boys who participated in a cross-sectional survey of Japanese junior high school students’ lifestyle. The survey aimed to assess the interactions between personal and environmental factors and adolescents’ life- style. A total of 761 students participated, including 379 boys. All participants were asked to complete a question- naire individually during class time. Demographic in- formation such as age, gender, and grade were collected with this questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, guardians, and the school. Partici- pation was voluntary, and confidentiality of the partici- pants was ensured. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of Waseda University. Data collection was conducted between Oct. and Dec. 2010. 2.2. Measures Measures of weight (kg) and height (cm) were col- lected through a height and weight measuring scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Participants were grouped into underweight, normal weight, over- weight, and obese by BMI ranges specific for age and gender using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria [20]. The frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per day) of physical activity at school during lunch re- cess and after-school hours in a usual week were re- ported by adolescents. For analysis, minutes per week of physical activity in two settings were calculated [21]. School environmental characteristics were assessed subjectively, using 10 items. These items comprised 3 factors: 1) “Equipment” (3 items), examining the accessi- bility or usability of physical equipment (e.g., There is enough equipment for physical activity at school); 2) “Facility” (4 items), measuring the accessibility or usabil- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 247 ity of physical activity facilities (e.g., The school ground is wide enough for physical activity); and 3) “Safety” (3 items) investigating perceived safety of physical activity equipment and facilities (e.g., It is safe to engage in phy- sical activity on the grounds and in the gym at school). The factorial reliability (Equipment: Cronbach α = 0.72; Facility: Cronbach α = 0.77; and Safety: Cronbach α = 0.78) of this scale was confirmed by respondents. All items were measured using a four-point scale from 1) strongly disagree to 4) strongly agree. To measure social support for physical activity, stu- dents were asked to rate support from three sources on a four-point scale from 1) no support at all to 4) strongly supported, using the following question: “How do you rate support for engaging in physical activity from 1) family, 2) teachers, or 3) friends?” The measure of self-efficacy (i.e., belief in one’s abi- lity to be active relative to peers) in the present study contained 1 item with response choices ranging from 1) strongly disagree to 4) strongly agree [22]. The statement was “I am able to do physical activities/exercises/sports better than my friends”. 2.3. Data Anal ysis A list-wise deletion procedure was adopted. Means and standard deviations (S.D.) of variables were then calculated through descriptive statistics using SPSS 18.0 software. The size of the final sample was adequate to estimate the models [23]. Finally, structural equation modeling (S.E.M.) analysis with maximum likelihood estimation using Amos 17.0 was performed to test the fit of proposed models. The original model leading to a good fit of the final model is described below. The measurement model in- cluded 1) three latent variables of physical environment: equipment (3 indicators), facilities (4 indicators), and safety (3 indicators); 2) relations between latent vari- ables and their indicators; and 3) correlations between three latent environmental factors. On the basis of the hypothesis, the structural model included 1) paths from perceived physical equipment, facilities, and safety, and BMI to perceived self-efficacy and self-reported physical activity, 2) path from self-efficacy to each source of so- cial support; and 3) paths from self-efficacy and three sources of social support to physical activity. Model fit was assessed using the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Akaike in- formation criterion (AIC). GFI and AGFI are used to measure how well the model fits the data and vary from 0 to 1, with 0.90 indicating an acceptable model fit and 0.95 indicating a good model fit [24,25]. RMSEA is a measure of the discrepancy between a population-based model and a hypothesized model assessed per degree of freedom. There is good model fit if the RMSEA is less than or equal to 0.05 with the upper limit of confidence interval less than 0.08 and the lower 90% confidence limit including or close to 0 [25]. A lower AIC value re- flects a better-fitting model compared with competing models [26]. A model was considered to fit the data when the following criteria were met: GFI > 0.90, AGFI > 0.90 (AGFI < GFI), RMSEA < 0.05, and lower AIC value compared with competing models. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To adjust the original specified model, new free pa- rameters were added based on the modified indices be- fore the Wald test to delete all non-significant free pa- rameters thereby increasing model fitness. Then, only significant causal paths with corresponding standardized regression coefficients (β) were shown in the figures of final structural models that demonstrated a good model fit. With the standardized regression coefficients, the magnitude of each factor could be directly compared with other factors in the model. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Participant Characteristics Of the 379 boys who returned the questionnaire, 300 with complete data (mean age = 13.5, S.D. = 0.96) com- prised the final sample. Mean height and weight were 161.85 cm (S.D. = 8.06) and 50.30 kg (S.D. = 11.77), respectively. The majority of adolescents had normal weight (5 ≤ BMI < 85 percentile, n = 236, 78.7%). More information about the characteristics of studied variables is provided in Table 1. Table 1. Characteristics of participants and physical activity outcome variable. Participants (Na = 300) Mean S.D.a Age (year) 13.49 0.99 Height (cm) 161.85 8.06 Weight (kg) 50.30 11.77 BMI 19.09 3.83 Lunch-time physical activity 16.80 35.88 After-school physical activity282.98 319.03 Grade (N, %) Grade 1 98 32.7% Grade 2 98 32.7% Grade 3 104 34.7% Weight status (N, %) Underweight 27 9.0% Normal weight 236 78.7% Overweight 21 7.0% Obesity 16 5.3% aN: Number; S.D.: Standard deviation. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 248 3.2. Structural Equation Model The final structural model for lunchtime physical ac- tivity in Figure 1 demonstrated a good model fit (GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.03 [90% confidence interval = 0.004 - 0.045]). The value of AIC was reduced from 815.83 to 204.70 after the model modifications. During lunch recess, self-efficacy (β = 0.13) directly and positively affected physical activity. The standardized coefficients for the indirect effect of perceived facilities, safety, and BMI through self-efficacy was –0.03, 0.03 and –0.02, respectively. Their effect sizes on physical activity were generally low. Perceived equipment and social support had neither direct nor indirect effects on lunchtime physical activity. Self-efficacy was the most important factor and mediator affecting lunchtime phy- sical activity. The final structural model for after-school physical ac- tivity presented in Figure 2 demonstrated a good model fit (GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.03 [90% con- fidence interval = 0.017 - 0.047]). The recalculation of the model after addition and deletion of free parameters reduced the AIC value from 859.15 to 237.16. Family support (β = 0.28) was identified as the most influential factor directly affecting physical activity during after- school hours. Self-efficacy (β = 0.06) and perceived equipment (β = 0.04) indirectly affected physical activity through family support. The path coefficient for the in- direct positive effects of perceived safety on physical activity through self-efficacy and family support was 0.02. The total effects of facilities (β = –0.14) on physi- cal activity were partially mediated by self-efficacy and family support. The path coefficient for the indirect negative effects of facilities through self-efficacy and family support on physical activity was –0.02. BMI (β = –0.01) indirectly affected physical activity through self- efficacy and family support. 4. DISCUSSION The present study examined cross-sectional effects of perceived school physical environment, social support, self-efficacy, and BMI on school-based physical activity in Japanese adolescent boys. The findings can support the development of school-based physical activity inter- vention programs meeting specific needs of adolescent boys regardless of age. The primary finding of this study was that the effects of variables on physical activity de- pended on the context, which implies that the develop- ment of effective interventions for promoting physical activity should be tailored for specific contexts. The present study also identified positive direct and indirect associations between self-efficacy and physical activity, although the domain of physical activity exam- ined was different from previous studies [8,10,13-15]. During lunch recess, self-efficacy was identified fully mediating the effects of facility, safety, and BMI on phy- sical activity. This finding supports previous studies showing that environmental factors affect physical activ- ity through psychological factors [13,14]. Both current and previous findings indicate that increasing self-effi- cacy might be a means of directly increasing physical activity during lunch recess. However, there were no sig- nificant associations between social support and physical activity, indicating that social support was not an effec- tive mediator. Therefore, exploring other third variables (e.g., perceived barriers, enjoyment, or friends’ physical activity behavior [9,27,28]) that act as influential factors Figure 1. Effects of personal, social, and physical environ-mental factors on lunch-time physi- cal activity among boys. Only statistically significant paths are indicated in the figure. The sig- nificance level was set at p < 0.05. Digitals in each path represent standardized path coeffi- cients. BMI: body mass index; Family: family support; Teacher: teacher support; Friend: friend support. OPEN ACCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 249 Figure 2. Effects of personal, social, and physical environmental factors on after-school physi- cal activity among boys. Only statistically significant paths are indicated in the figure. The sig- nificance level was set at p < 0.05. Digitals in each path represent standardized path coeffi- cients. BMI: body mass index; Family: family support; Teacher: teacher support; Friend: friend support. mediating the associations between self-efficacy, physi- cal environment, and lunchtime physical activity are warranted in the future. During after-school hours, in line with the hypothesis, family support was found to fully mediate effects of equipment, safety, self-efficacy, and BMI on physical activity. In addition, perceived accessible facilities di- rectly or indirectly affected physical activity through self-efficacy and family support. This finding indicates that increasing perceived family support might serve as a beneficial strategy for increasing physical activity during after-school hours. However, evidence against the hy- pothesis was that support from friends and teachers did not significantly affect such physical activity. Much at- tention has been paid to comparing the influences of family and friends as sources of social support for ado- lescent physical activity [11,29-33]. However, conflict- ing results were found in previous studies [11,29,30, 32,33]. There is a lack of studies taking into account support from teachers when investigating the relative importance of family, friends, and teachers on adolescent boys’ school-based physical activity. Consistent with the study by Hsu et al. [33], the present study identified fam- ily support as significantly influencing boys’ physical activity, while the effect of friend support was not sig- nificant. This finding was explicable based on the sub- stantial reliance of adolescent boys on instrumental or informational and emotional support from family. Boys may follow their friends in joining activities, but family support (e.g., cost of equipment, approval, encourage- ment or praise for behaviors, or talking about activities frequently) might be more important in removing barri- ers to being active, especially in early adolescence [10, 29,33,34]. The latest national report regarding family effects on junior high students’ exercise habits showed that across Japan, 40.8% of junior high boys talked about physical activities with their families at least once weekly [35]. It is understandable that teacher support was not significantly important because after-school hours repre- sent free time in which physical activity becomes a lei- sure choice. The influence of teachers on adolescents might be more significant in physical education courses than during free-time choices. Based on the present findings, designing more effective interventions through family support should involve more in-depth research examining types of family support (e.g., encouragement or tangible assistance) in association with context-spe- cific physical activity. Moreover, it is necessary to un- derstand the interaction effects of family, friends, and teachers (e.g., the combined effect of any two sources and the full interaction of all three sources) on school- based physical activity in the future. Previous research has revealed significant direct and positive influences of some school environmental char- acteristics (e.g., availability of play equipment and facili- ties like playing fields) on overall physical activity or recess physical activity at school [36,37]. However, un- derstanding regarding how various components of the school environment impact school-based physical acti- vity is limited. In this respect, the present study revealed that perceived equipment had neither direct nor indirect effects on lunchtime physical activity, but had indirect effects on after-school physical activity through family support. This difference might be explained by the fact Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 250 that boys are often involved in different types of physical activity in different time periods during weekdays [38]. In Japan, recess after lunch for students is only about 20 minutes, whereas time at school at the end of day is about 3 hours. Boys might tend to engage in physical activities that do not require equipment (e.g., playing or walking between school buildings/classrooms) during the short lunch recess. Accordingly, further studies should take types of activities into account to better understand how the physical environment affects preferred types of activities during different time periods. Against expectation and previous studies [15,39], per- ceived facilities were found to be inversely associated with boys’ physical activity in the present study. It is possible that boys who actually used facilities compared to boys who did not reported lower scores for available facilities because the latter were less aware of the real situation regarding the facilities. Further studies are needed to test whether perceptions of facilities match ob- jective measurements to clarify the influence of facilities on physical activity. In addition, the present study indi- cates that boys who perceived high safety were more active than those who reported low perceptions of safety, regardless of setting. This finding suggests that increas- ing perceptions of safety as well as equipment is a possi- ble way to promote self-efficacy and social support and perhaps ultimately increase physical activity among boys. This highlights the necessity of improving both the ob- jective environment to be more activity-friendly at school and perceptions among students of school resources for physical activity. There are various strategies that might be used to increase the awareness of equipment at school and its safety. For example, school officials might update news of regular maintenance of facilities and equipment in a monthly report distributed to students and parents, or put a sign on school grounds informing students of the available equipment or facilities. Regardless, more in- depth research is necessary in regard to manipulating perceptions of the physical environment to observe changes in self-efficacy and perceptions of social support and physical activity. Finally, the present study indicates that boys with higher BMI were less active than those with lower BMI because they perceived less self-efficacy and family support. Thus, it is important in the future to examine the interventional effects of self-efficacy and family support on physical activity in overweight or obese boys. Con- sidering that factors influencing physical activity might be different in those overweight, obese, or of normal weight, more research is needed to explore correlates/ determinants of physical activity in overweight and obese adolescents. This could facilitate the development of effective strategies for promoting physical activity among this specific at-risk group. 4.1. Strengths The first strength of this study was extending previous research by simultaneously measuring direct and indirect effects of multilevel contributing factors on context-spe- cific physical activity rather than overall physical activity level. Several sources of social support and various school physical environmental attributes were examined concurrently. Second, this study contributed to studies about adolescents by exploring a behavioral model tai- lored for adolescent boys’ physical activity behavior. Finally, this study used SEM, which was helpful in ex- ploring potential mediators that can be intervened upon, and allowed the examination of relative contributions of factors that explain physical activity behavior. 4.2. Limitations One limitation of this study is the use of a self-report measure of physical activity, which is subject to error and bias. Further studies should attempt to combine ex- isting objective and subjective measures to investigate context-specific physical activity more accurately. An- other limitation is the list-wise deletion adopted in the present study that may have biased the data findings. A further limitation is that generalizability of findings be- yond the study location may be limited because data were collected from a single school. However, the pre- valence of overweight and obesity among Japanese jun- ior high students in a national survey (8.4% [40]) was only slightly lower than in the present study (12.3%). Therefore, it is likely that the structural models in this study would fit counterparts across the country. Still an- other limitation was the cross-sectional data that permit- ted only estimates of between-person relations among variables. Therefore, longitudinal or interventional de- signs are warranted in the future. 4.3. Conclusion The present study implies that improvement of self- efficacy and family support can be effective in directly increasing school-based physical activity in adolescent boys. Furthermore, these findings can encourage re- searchers as well as policy makers, both at school and the national level, to consider resources and improvements in school physical environments as a means of increasing perceptions of social support and self-efficacy when de- veloping programs and strategies that are important to increasing physical activity indirectly. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This investigation was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 22700680) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Waseda University Grant for Special Research Projects Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 251 (2010A-095, 2011A-092), and the Global COE Program “Sport Sci- ences for the Promotion of Active Life” from the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. REFERENCES [1] Hallal, P.C., Victora, C.G., Azevedo, M.R. and Wells, J.C. (2006) Adolescent physical activity and health: A system- atic review. Sports Medicine, 36, 1019-1030. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636120-00003 [2] Janssen, I. and LeBlanc, A.G. (2010) Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7, 40. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-40 [3] Biddle, S.J.H. and Mutrie, N. (2008) Psychology of phy- sical activity: Determinants, well-being and interventions. 2nd Edition, Routledge, London and New York. [4] World Health Organization (2012) Global recommenda- tion on physical activity for health. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/97892415999 79_eng.pdf [5] Baron, R. and Kenny, D. (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Con- ceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [6] Sallis, J.F. and Owen, N. (2002) Ecological model of health behavior. In: Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K. and Lewis, F.M., Eds, Health Behavior and Health Education, 3rd Edition, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 462-464. [7] Dishman, R.K., Motl, R.W., Saunders, R., Felton, G., Ward, D.S., Dowda, M., et al. (2004) Self-efficacy par- tially mediates the effect of a school-based physical ac- tivity intervention among adolescent girls. Preventive Me- dicine, 38, 628-636. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.007 [8] Dishman, R.K., Saunders, R.P., Motl, R.W., Dowda, M. and Pate, R.R. (2009) Self-efficacy moderates the relation between declines in physical activity and perceived social support in high school girls. Journal of Pediatric Psy- chology, 34, 441-451. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn100 [9] Dishman, R.K., Dunn, A.L., Sallis, J.F., Vandenberg, R.J. and Pratt, C.A. (2010) Social-cognitive correlates of phy- sical activity in a multi-ethnic cohort of middle-school girls: Two-year prospective study. Journal of Pediatric Psy- chology, 35, 188-198. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp042 [10] Trost, S.G., Sallis, J.F., Pate, R.R., Freedson, P.S., Taylor, W.C. and Dowda, M. (2003) Evaluating a model of pa- rental influence on youth physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 277-282. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00217-4 [11] Wu, T., Pender, N. and Noureddine, S. (2003) Gender differences in the psychosocial and cognitive correlates of physical activity among Taiwanese adolescents: A struc- tural equation modeling approach. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10, 93-105. doi:10.1207/S15327558IJBM1002_01 [12] Motl, R.W., Dishman, R.K., Ward, D.S., Saunders, R.P., Dowda, M., Felton, G., et al. (2005) Comparison of bar- riers self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control for explaining physical activity across 1 year among adoles- cent girls. Health Psychology, 24, 106-111. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.106 [13] Motl, R.W., Dishman, R.K., Ward, D.S., Saunders, R.P., Dowda, M., Felton, G., et al. (2005) Perceived physical environment and physical activity across one year among adolescent girls: Self-efficacy as a possible mediator? Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 403-408. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.004 [14] Motl, R.W., Dishman, R.K., Saunders, R.P., Dowda, M. and Pate, R.R. (2007) Perceptions of physical and social environment variables and self-efficacy as correlates of self-reported physical activity among adolescent girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 6-12. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsl001 [15] Lubans, D.R., Okely, A.D., Morgan, P.J., Cotton, W., Pug- lisi, L. and Miller, J. (2012) Description and evaluation of a social cognitive model of physical activity behaviour tailored for adolescent girls. Health Education Research, 27, 115-128. doi:10.1093/her/cyr039 [16] Rosenberg, D., Ding, D., Sallis, J.F., Kerr, J., Norman, G.J., Durant, N., et al. (2009) Neighborhood environment walkability scale for youth (NEWS-Y): Reliability and relationship with physical activity. Preventive Medicine, 49, 213-218. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.011 [17] Nader, P.R., Bradley, R.H., Houts, R.M., McRitchie, S.L. and O’Brien, M. (2008) Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years. JAMA, 300, 295-305. doi:10.1001/jama.300.3.295 [18] Berk, L.E. (2005) Infants, children and adolescents. 5th Edition, Allyn & Bacon Inc., Bosten. [19] Ridgers, N., Stratton, G. and Fairclough, S. (2006) Physi- cal activity levels of children during school playtime. Sports Medicine, 36, 359-371. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636040-00005 [20] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) About BMI for children and teens. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/children s_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html [21] He, L., Ishii, K., Shibata, A., Adachi, M., Nonoue, K. and Oka, K. (2012) Patterns of physical activity outside of school time among Japanese junior high school students. Journal of School Health, in Press. [22] Ryan, G. and Dzewaltowski, D. (2002) Comparing the relationships between different types of self-efficacy and physical activity in youth. Health Education & Behavior, 29, 491-504. doi:10.1177/109019810202900408 [23] North Carolina State University (2012) Structural equa- tion modeling: Statnotes. http://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/PA765/structur.htm [24] Kline, R.B. (1998) Principle and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford, New York. [25] Schumacker, R.E. and Lomax, R.G. (2004) A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. 2nd Edition, Law- rence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah. [26] Hamparsum, B. (1987) Model selection and Akaike’s in- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  L. He et al. / Health 5 (2013) 245-252 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS 252 formation criterion (AIC): The general theory and its ana- lytical extensions. Psychometrika, 52, 345-370. doi:10.1007/BF02294361 [27] Dishman, R.K., Motl, R.W., Saunders, R, Felton, G., Ward, D.S., Dowda, M., et al. (2005) Enjoyment medi- ates effects of a school-based physical activity interven- tion. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 37, 478-487. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000155391.62733.A7 [28] Jago, R., Page, A.S. and Cooper, A.R. (2012) Friends and physical activity during the transition from primary to se- condary school. Medicine and Science in Sports and Ex- ercise, 44, 111-117. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318229df6e [29] Duncan, S., Duncan, T. and Strycker, L. (2005) Sources and types of social support in youth physical activity. Health Psychology, 24, 3-10. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.3 [30] Hohepa, M., Scragg, R., Schofield, G., Kolt, G.S. and Schaaf, D. (2007) Social support for youth physical activ- ity: Importance of siblings, parents, friends and school support across a segmented school day. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4, 54. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-54 [31] Lubans, D.R., Morgan, P.J., Callister, R., Collins, C.E. and Plotnikoff, R.C. (2010) Exploring the mechanisms of physical activity and dietary behavior change in the pro- gram X intervention for adolescents. Journal of Adoles- cent Health, 47, 83-91. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.015 [32] Patnode, C.D., Lytle, L.A., Erickson, D.J., Sirard, J.R., Barr-Anderson, D. and Story, M. (2010) The relative in- fluence of demographic, individual, social, and environ- mental factors on physical activity among boys and girls. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physi- cal Activity, 7, 79. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-79 [33] Hsu, YW, Chou C.P., Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T., McClain, A.D., Belcher, B.R. and Spruijt-Metz, D. (2011) Influ- ences of social support, perceived barriers, and negative meanings of physical activity on physical activity in mid- dle school students. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 8, 210-219. [34] Ornelas, I.J., Perreira, K.M., and Ayala, G.X. (2007) Pa- rental influences on adolescent physical activity: A lon- gitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nu- trition and Physical Activity, 4, 3. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-3 [35] Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Tech- nology, Japan (2012) 2010’s national survey result of physical and athletic capacity and exercise habits. http://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/sports/detail/_ _icsFiles/afieldfile/2010/12/16/1300103_5.pdf [36] Haug, E., Torsheim, T. and Samdal, O. (2008) Physical environmental characteristics and individual interests as correlates of physical activity in Norwegian secondary schools: The health behaviour in school-aged children study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, 47. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-5-47 [37] Haug, E., Torsheim, T., Sallis, J.F. and Samdal, O. (2010) The characteristics of the outdoor school environment associated with physical activity. Health Education Re- search, 25, 248-256. doi:10.1093/her/cyn050 [38] Stanley, R.M., Ridley, K. and Olds, T.S. (2011) The type and prevalence of activities performed by Australian children during the lunchtime and after school periods. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 14, 227-232. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2010.10.461 [39] Durant, N., Harris, S.K., Doyle, S., Person, S., Saelens, B.E., Kerr, J., et al. (2009) Relation of school environ- ment and policy to adolescent physical activity. Journal of School Health, 79, 153-159. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00384.x [40] Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Tech- nology, Japan (2012) 2010’s national survey result of physical and athletic capacity and exercise habits: (4) physical fitness and BMI. http://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/sports/detail/_ _icsFiles/afieldfile/2010/12/16/1300270_4_1.pdf

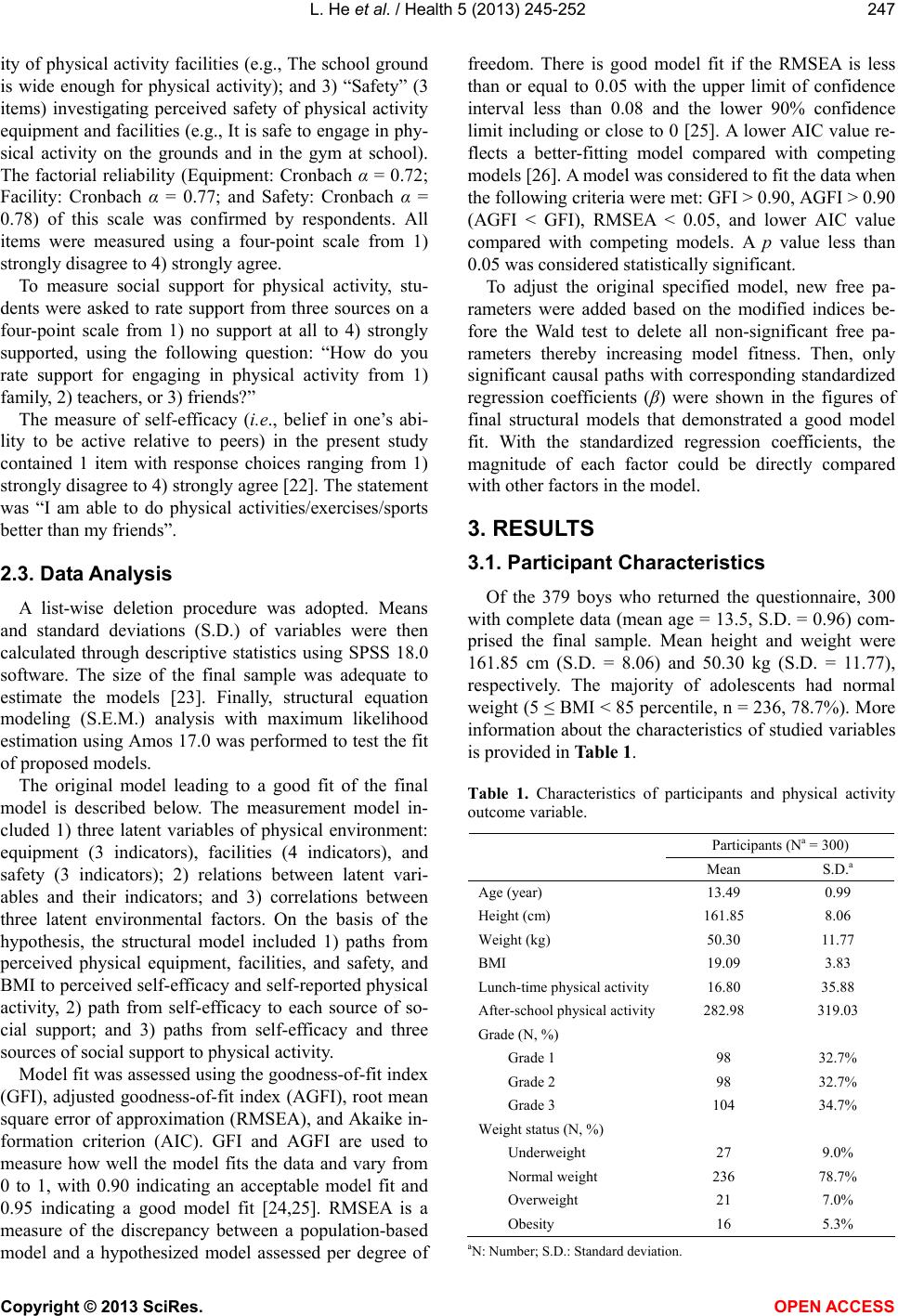

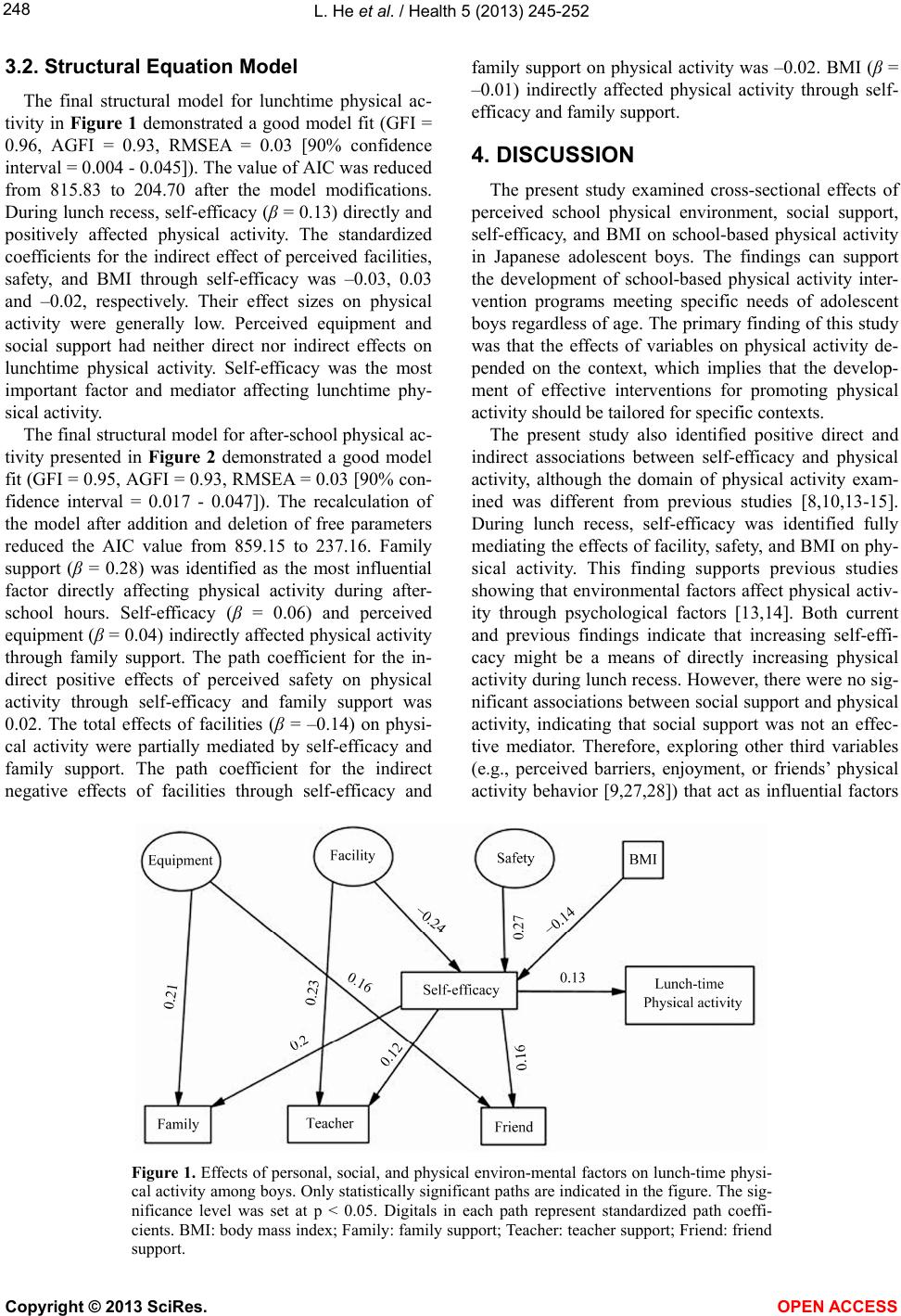

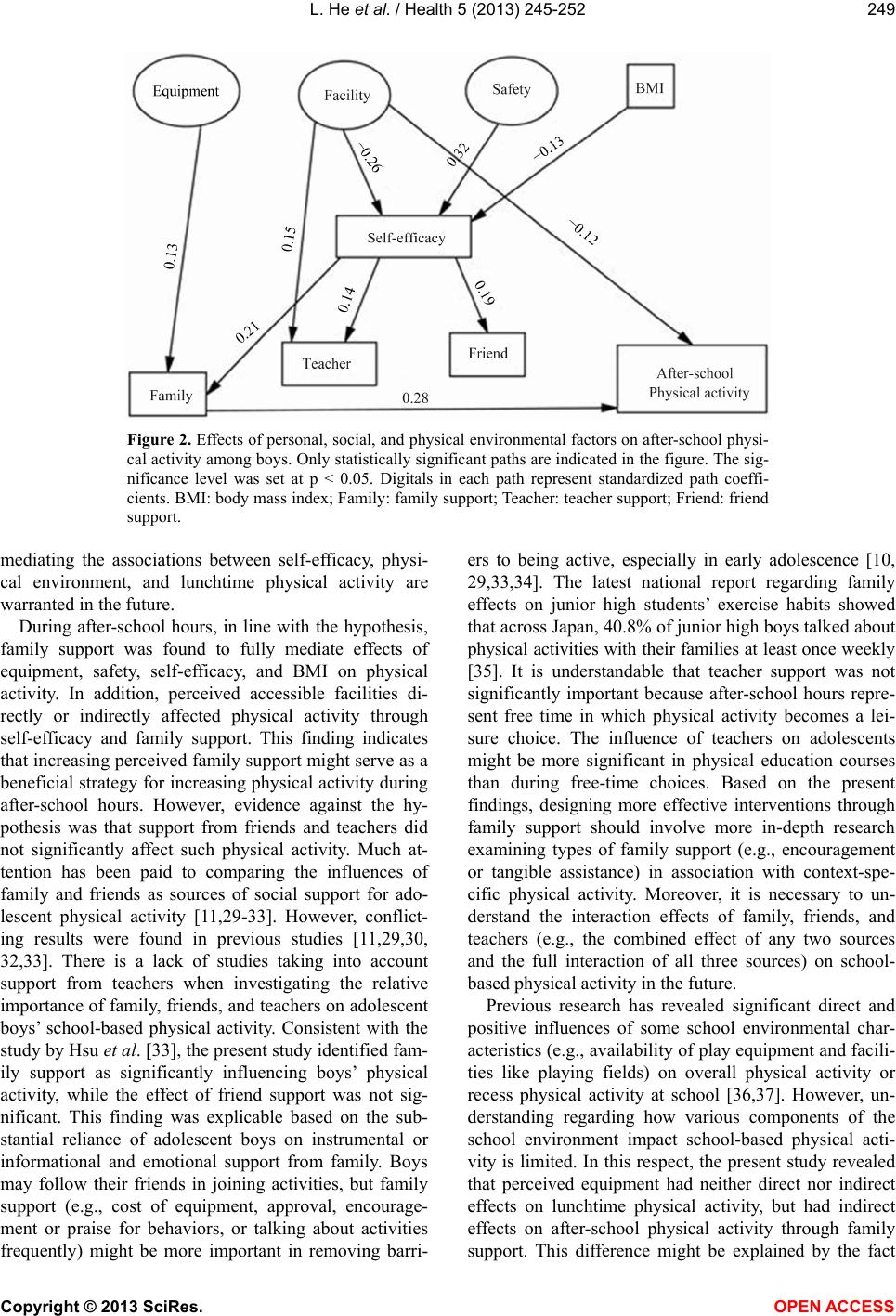

|