Vol.5, No.2, 237-244 (2013) Health http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/health.2013.52032 Impact of postnatal maternal depressive symptoms and infant’s sex on mother-infant interaction among Bangladeshi women Maigun Edhborg1*, Beatrice Hogg1#, Hashima-E-Nasreen2, Zarina Nahar Kabir1 1Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; *Corresponding Author: maigun.edhborg@ki.se 2Research and Evaluation Division, BRAC, Dhaka, Bangladesh Received 14 September 2012; revised 15 October 2012; accepted 22 October 2012 z ABSTRACT Aim: To investigate the impact of postnatal de- pressive symptoms and infant sex on perceived and observed mother-infant interaction among rural Bangladeshi women. Metho ds: Fifty women with depressive symptoms and their infants at 2 - 3 months were compared with 50 women without depressed symptoms and their infants, matched on geographic areas, parity and infant sex. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale assessed depressive symptoms, the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire assessed the mother’s perception of bonding with the infant and mother-infant interactions were videotaped and analyzed with the Global Rating Scale. Results: Mothers with depressive symptoms were poorer, were less educated and rated lower infant bond- ing than mothers without depressive symptoms (p = 0.03), yet objective observation revealed no difference between the two groups regarding maternal interactive behavior (p = 0.57). How- ever, infants, particularly boys (p = 0.002), of mothers with depressive symptoms fretted more in mother-infant interaction than infants of moth- ers without depressive symptoms (p = 0.009). Conclusion: Although mothers with depressive symptoms did not show less sensitivity in in- teractive behavior at 2 - 3 months than those without depressive symptoms, our results indi- cate that infants, particularly boys, of mothers with depressive symptoms may be negatively influenced by depressiv e symptoms. Keyw ords: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms; Mother-Infant Interaction; Bonding; Bangladesh 1. INTRODUCTION Maternal depressive symptoms related to childbirth are common in both high- and low income countries [1, 2]. However, socially disadvantaged populations show higher depression rates than wealthy industrial nations [3]. A systematic review from low- and lower-middle income countries showed a prevalence of 19.8% of com- mon mental disorder postpartum [4]. In South Asia, the prevalence of depression has been reported to be 12% - 28% postpartum, including the low prevalence of 12% found in Nepal [5-8]. Depression is a disabling disorder with symptoms such as low mood, lack of energy and interest, poor concen- tration and sometimes thoughts of suicide or death, all of which are likely to interfere with a mother’s parenting capacity. Indeed, there is convincing evidence that ma- ternal depression during the postnatal period is associ- ated with negative effects on the infant’s mental, cogni- tive and socio-emotional development [9-11]. An expla- nation for these developmental adversities could be dis- turbances in the early mother-infant relationship [12]. The relational behavior of depressed mothers in high- income countries has been characterized by low sensitiv- ity, a restricted range of affective expression and incon- sistent support of the infant’s growing social engagement [13]. A mother’s emotional communicative skill is very important during the first postpartum period to regulate the infant’s states of arousal and emotion. Ineffective regulation generates extreme states of arousal and affect that could disrupt the infant’s engagement with people and the environment [3]. Although there is a mismatch of emotions and intentions in all mother-infant interaction, the mismatch is quickly repaired in normal interactions. Mismatches generate negative affect in the infant, whereas restoration to a matching state is associated with positive affect, leading to a sense of mastery and control [3]. Stein #Formerly Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 238 et al. [13] suggest that maternal preoccupation is a factor that contributes to the adverse effect on development among infants of mothers with depressive symptoms. Preoccupation refers to the process of recurrent negative thinking that is characteristic of depression and interferes with the mother’s attention and responsiveness towards the infant [13]. A study in Bangladesh exploring mater- nal depressive symptoms and infant development re- ported that maternal depressive symptoms interfered with the mothers’ sensitivity and ability to provide stimulating play materials and thus, give the infant few opportunities for exploration and social engagement at home [14]. Only a few studies have investigated mother-infant interactions related to maternal depressive symptoms in low-income countries. In South Africa, Cooper et al. [15] found that depressed mothers in Khayelitsha, a periurban setting in the outskirts of Cape Town with high levels of poverty, were less sensitive to their infants in early face- to-face interactions, and their infants were less positively engaged with their mothers, than infants of non-de- pressed mothers. Although Field [16] claims that interaction distur- bances among depressed mothers and their infants appear to be universal across cultures and socioeconomic groups, the pressure on a mother in conditions of extreme po- verty could differ from those facing a mother in high- income countries. Since several studies have reported on gender preference in favor of boys in some Asian cul- tures [17,18] and how giving birth to a female baby is a risk factor for depressive symptoms [19], it is important to explore if the sex of the infant influences the mother- infant interaction. Therefore, this study aims to investi- gate the relationship between maternal depressive symp- toms and the infant’s sex 2 - 3 months postpartum on perceived and observed mother-infant interaction in rural Bangladesh. 2. METHOD 2.1. Design and Setting This is a nested-case control study of a prospective- cohort study of postnatal depressive symptoms and infant development carried out in two rural subdistricts of the Mymensingh district, 120 km north of the capital city of Dhaka in Bangladesh. This district is typical of deltaic Bangladesh and is a predominantly agricultural commu- nity characterized by homogeneity in terms of ethnicity, culture and language. For the prospective-cohort study, 720 women were recruited during their third trimester of pregnancy, and the women and their infants were fol- lowed up at birth, 2 - 3 months and 6 - 8 months post- partum. At 2 - 3 months postpartum, 673 mothers with infants remained in the study. The reasons for attrition (6.5%) were outmigration (n = 9), maternal death at childbirth (n = 2), stillbirth (n = 25) and neonatal death (n = 11). As in other rural areas of Bangladesh, the ma- jority of the women was poor and had domestic work and child care as their primary occupations. Approxi- mately 40 per cent of the population lived below the poverty line [20]. 2.2. Participants Of the 673 mothers remaining in the cohort study at 2 - 3 months postpartum, 95mothers (14%) showed de- pressive symptoms (i.e., scored 10 or more on the Edin- burgh Postnatal Depression Scale, or EPDS). As soon as a mother was identified as having depressive symptoms at 2 - 3 months, she was approached and asked to par- ticipate together with her infant in a video observation of a mother-infant interaction. In case of consent, a mother without depressive symptoms (control, i.e., scored less than 10 on the EPDS) was identified and requested to participate with her infant. Thus, 50 mothers and their infants were consecutively selected as cases, and 50 as controls. The control mothers were matched with the cases by geographic area, parity and the infant’s sex. All 100 mothers were informed of the aim of the study, pro- cedures of the video recording and that participation was voluntary. None of the mothers declined participation. The sample size was chosen at a significance level of 5 per cent, a power of 80 per cent and an effect size of 60 per cent to detect differences in the mother-infant inter- action between cases and controls. 2.3. Data Collection and Procedures The background data were taken from the prospective cohort study, which was collected by trained, female interviewers through structured interviews in the respon- dents’ homes. These female interviewers were trained over two weeks; all questionnaires were discussed and pretested outside the study site. Information was col- lected during pregnancy on demographics, including maternal age and socioeconomic status (SES) indicated by educational level, primary occupation, involvement in income-generating activities, land ownership by house- hold and daily expenditure on food in the respondent’s household. Obstetric and child information were measured by parity, mean number of living children and having more than four children. Family characteristics and support in- cluded the women’s perceived relationship with husband and mother-in-law and practical help received during pregnancy. Intimate partner violence encompassed phy- sical violence ever and/or during pregnancy and forced sex. At 2 - 3 months postpartum, information was ob- tained on low birth weight of the infant (≤2.5 kg), pre- term delivery (≤37 pregnancy weeks), exclusive breast- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 239 feeding, the mother’s perception of the infant’s care (easy, in-between, difficult), the mother’s bonding with her infant and maternal depressive symptoms. Mother-infant interactions were video recorded. The recording took place at an office in the local setting by two specially trained Bangladeshi social science re- searchers. The mothers were offered transportation and food for their participation. The video sessions lasted for five minutes when the infants were alert and not hungry. The mothers were asked to interact or play with the in- fant as they would do at home. The infants were between 3 - 9 months old when the video recording took place. A camera on a tripod was placed in the room to the right side of a big mirror. The mothers were seated in front of the mirror and had a large pillow on their outstretched legs on which to put the baby, so that the infant’s face and body would be seen in the camera. The camera was to the right of the mother, recording the mother’s face and body to the hips and the infant’s face and body. The mothers were left alone with their infants during the video recording. The Bangladesh Medical Research Council, Bangladesh, and the Regional Ethical Review Board at Karolinska Institute, Sweden, approved the study. 2.4. Instruments The Edinburgh Postnatal Depressive Scale (EPDS) [21] was used to detect depressive symptoms. The EPDS is a 10-item questionnaire that has recently been vali- dated in Bangladesh (EPDS-B), showing a sensitivity of 89 per cent, a specificity of 87 percent and a cutoff score of 9/10 [18]. For this study we used the same cutoff as Gausia et al. [22]. The items of the EPDS were rated on a scale of 0 - 3, and a high score indicated more depres- sive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80 at 2 - 3 months postpartum. The Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) [23,24] was used to assess mothers’ perceptions of their emo- tional bonding with their infants. The PBQ consists of 25 items, rated on a scale of 0 - 5, high scores indicating greater bonding disturbances. Four subscales are in- cluded. Subscale 1 indicates impaired bonding between mother and infant (12 items) with a cutoff score of 11/12 identifying mild bonding problems. Subscale 2 indicates rejection and anger towards the infant (7 items) with a cutoff score of 12/13 identifying mothers with threatened rejection and 16/17 identifying those with established rejection, or more severe bonding problems. Subscale 3 indicates anxiety about the care of the infant (4 items), with a cutoff of 10/11. At subscale 4, there is a risk of abuse of the infant by the mother (2 items). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha on the total PBQ was 0.82, and on the subscales of impaired bonding it was 0.65, rejection and anger 0.60, and anxiety about care 0.44—results that are similar to those reported by Brockington et al. [23]. Risk of abuse showed an excessively low Cronbach’s alpha and was excluded from the analyses. The instru- ment was translated from English into Bangla and back from Bangla into English by two bilingual persons [25]. PBQ has been validated in China and was found to have satisfactory face and content validity and to be sensitive in detecting impairments of the mother-infant relation- ship as perceived by the mother with the cut-off scores suggested by Brockington et al. [26]. Analysis of mother-infant interaction The Global Rating Scale (GRS) of infant-mother in- teraction was used to assess infant-mother interaction [27]. This method has been found to be valid cross-cul- turally in four European countries [28] and in South Af- rica [15]. Two of the authors (ME and BH) were trained in the method at a research centre in Reading, England. The analyses were done blind as to the depressive status of the mothers, based on videos and English verbatim transcripts, which were translated from Bangla to Eng- lish, English to Bangla and back again to English by two bilingual persons to ensure the reliability of the transla- tion. The mothers’ behavior was assessed on 13 items, the infants’ on 7 and dyadic behavior on 5. The items are scored on a 5-point scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (good) and clustered by summing up and form dimensions. 1) The mother’s good-poor dimension (sensitivity) was measured by five items: warmth, acceptance, respon- siveness, non-demanding behavior and sensitivity. 2) The mother’s intrusive dimension was measured by her intrusive or nonintrusive behavior and speech. 3) The mother’s remote dimension was assessed by her remote or non-remote and silent or non-silent behavior. 4) The mother’s affective behavior (depression) was assessed by happiness, energy to engage with the infant, absorption in the infant and whether she was relaxed or tense during the interaction. The infant’s interactive behavior was also measured. 1) The infant’s good-poor dimension (engagement) was measured by attentiveness towards the mother, active communication with body and voice towards the mother and positive vocalization. 2) The infant inert-lively dimension (liveliness) meas- ured the infant’s engagement with the environment, whether he/she was self-absorbed or not and whether or not he/she was lively or inert. 3) The infant distress dimension (fretfulness) was in- dicated by happy or distressed and fretful or non-fretful. Dyadic behavior: 4) The mother-infant interaction dimension was as- sessed by smooth and easy or difficult, fun or serious, mutually satisfying or unsatisfying, involving much en- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS 240 gagement or no engagement and excited engagement or quiet engagement [24]. Two of the authors (BH, ME) rated the videos. Forty- eight videos were rated by consensus and fifty-two indi- vidually. Of those individually rated, nine were coded for internal reliability, with 92 percent of the ratings being found to be in agreement. 2.5. Statistical Analyses The statistical analyses were done using SPSS for Windows, version 18. Differences between the mothers with and without depressive symptoms, infant sex and the PBQ were calculated by two-way multivariate analy- sis of variance (MANOVA). The GRS (assessing mother and infant behavior) was similarly analyzed by two-way MANOVAs, and dyadic behavior was analyzed with a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Cases and con- trols were compared according to the background vari- ables by independent t-test and chi-square. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Description of the Sample As seen in Table 1, compared to mothers without, mothers with depressive symptoms were less educated and poorer in terms of land owned by the household and daily expenditure on food per household member. More mothers with depressive symptoms reported experienc- ing physical violence ever in life and during current pregnancy and had infants with low birth weight com- pared to mothers without depressive symptoms. Mothers Table 1. Information on demographic, socio-economic, obstetric, child, family support and intimate partner violence of the sample (N = 100). Mothers with depressive symptoms N = 50 Mothers without depressive symptoms N = 50 p Age (M ± SD) 26.6 (6.32) 25.6 (6.09) 0.432 Educational level Years of schooling (M ± SD) 1.86 (2.86) 3.22 (3.07) 0.024 Illiterate [N (%)] 38 (78) 10 (28) 0.001 Primary occupation [N (%)] Domestic work 45 (90) 49 (98) 0.092 Land owned by HH [N (%)] 1 - 49 decimal 46 (92) 34 (68) ≥50 decimal 4 (8) 16 (32) 0.003 Per daily household expenditure (in Taka)* on food (M ± SD) 27.4 (11.1) 36.0 (17.3) 0.004 Obstetric and infant data First time mothers [N (%)] 6 (12) 7 (14) 0.766 Number of children (M ± SD) 3.0 (2.3) 2.4 (1.8) 0.130 More than 4 children [N (%)] 19 (38) 12 (24) 0.130 Low birth weight (<2.5 kg) [N (%)] 15 (30) 5 (10) 0.012 Preterm (<37 weeks) [N (%)] 8 (16) 8 (16) 1.000 Still breastfeeding exclusively [N (%)] 16 (32%) 25 (50%) 0.067 Difficult to care for the infant [N (%)] 34 (68%) 20 (40%) 0.019 Family characteristic and support Poor relationship—husband [N (%)] 7 (14) 0 0.012 Poor relationship—mother-in-law [N (%)]** 5 (12.5) 6 (14.3) 0.813 Did not have practical support [N (%)] 11 (22) 16 (32) 0.260 Intimate partner violence Forced sex [N (%)] 44 (88) 37 (74) 0.074 Physical violence ever [N (%)] 46 (92) 34 (68) 0.003 Physical violence during current pregnancy [N (%)] 18 (36) 7 (14) 0.011 *1 US-dollar = approximately 71 Bangladeshi Taka (BDT); **Calculation computed on 82 mothers-in-law.  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 241 with depressive symptoms reported their infants at 2 - 3 months as being significantly more difficult to care for compared to the mothers in the control group (Table 1). The mean EPDS at 2 - 3 months was 11.5 (SD 1.4) among the cases and 4.3 (SD 1.4) among the controls. 3.2. Maternal Perception of Bonding with Infants According to the PBQ A two-way MANOVA showed a main effect of ma- ternal depressive symptoms (F(3,94) = 3.06; p = 0.03) but no effect of infant sex (F(3,94) = 1.96; p = 0.13) on the PBQ, which measures mothers’ perceptions of bonding with their infants. Follow-up ANOVAs indicated that mothers with depressive symptoms reported more im- paired bonding and anxiety about infant care than mo- ther’s without depressive symptoms, but they did not show more rejection and anger towards the infant indi- vidually. Of those individually rated, nine were coded for internal reliability, with 92 percent of the ratings being found to be in agreement. A tendency of interaction effect was observed between depressive symptoms and infant sex (F(3,94) = 2.71; p = 0.051) indicating that mothers without depressive symp- toms expressed more rejection and anger to their daugh- ters than to their sons on the PBQ. However, mothers with depressive symptoms rated rejection and anger equally, regardless of sex of the infant (Table 2). 12% of the mother reported mild impaired bonding to their in- fants. Four mothers reported threatened rejection and one establish rejection i.e. more severe bonding disturbances. The last sentence has disappeared in the text. It is only a descriptive clarification of how many of the mothers who showed bonding disturbances. The whole sentence could be taken away if you want. 3.3. The Mother-Infant Interaction According to the GRS A two-way MANOVA showed that neither maternal depressive symptoms (F(4,93) = 0.74; p = 0.57) nor infant sex (F(4,93) = 0.37; p = 0.83) had any significant main effect on maternal interacting behavior on the GRS. On the other hand, on the GRS, maternal depressive symp- toms (F(3,94) = 3.52; p = 0.02) as well as infant sex (F(3,94) = 3.91; p = 0.01) showed main effects on infant interac- tive behavior. Follow-up ANOVAs indicated that infants, particu- larly boys of mothers with depressive symptoms, were more distressed and fretful, but not less engaged or lively, during the interaction than infants of mothers without depressive symptoms (Table 3). No significant interaction between maternal depressive symptoms and infant sex was found (F(3,94) = 0.69; p = 0.56). Finally, on the GRS, a two-way ANOVA showed no effects of maternal depressive symptoms (F(1,96) = 0.45; p = 0.51) or infant sex (F(1,96) = 0.88; p = 0.35) on dyadic behavior. 4. DISCUSSION The main finding of this study is that mothers with depressive symptoms rated their bonding with their in- fants significantly lower on a self-reported scale than did mothers without depressive symptoms in rural Bangla- desh. However, objective observation of mother-infant interaction did not indicate any significant differences in the interactive behavior of mothers with and without de- pressive symptoms. On the other hand, observation of infant behavior indicated that infants of mothers with depressive symptoms were more distressed and fretful during the interaction than infants of mothers without depressive symptoms. This behavior was more pro- nounced in boys than in girls. The finding that mothers with depressive symptoms rated their bonding lower than mothers without depres- sive symptoms, while their observed interactive behavior did not indicate any difference, was consistent with re- search by Frankel and Harmon [29]. They also found that depressed women reported more negative evaluations of themselves as parents than did non-depressed women, even if no difference was found in observed maternal in- teractive behavior. Similarly, Hornstein et al. [30] found Table 2. Comparisons between mothers with and without depressive symptoms and sex of infant according to parental bonding (N = 100) (Mean, SD). Mothers with depressive symptoms N = 50 Mothers without depressive symptoms N = 50 p-value p-value p-value Boys N = 27 Girls N = 23 Boys N = 28 Girls N = 22 Difference depressive/non depressive symptoms Difference infant’s sex Interaction maternal depr/infant’s sex PBQ-subscale 1 Impaired bonding 8.2 (4.3) 8.5 (4.0) 5.6 (2.8) 6.8 (3.6) 0.005 0.301 0.594 PBQ-subscale 2 Rejection and anger 5.3 (3.1) 5.1 (3.4) 3.1 (2.4) 5.5 (4.1) 0.143 0.088 0.051 PBQ-subscale 3 Anxiety about care 3.9 (2.2) 3.9 (2.4) 3.0 (2.2) 2.8 (2.2) 0.032 0.823 0.719 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 242 Ta bl e 3 . Comparisons between mothers with and without depressive symptoms and sex of the infant according to the dimensions of Global Ratings Scale (N = 100) (Mean, SD). Mothers with depressive symptoms (N = 50) Mothers without depressive symptoms (N = 50) p-value p-value Boy (N = 27) Girl (N = 23)Boy (N = 28)Girl (N = 22)Difference depressive/non depr symptoms Difference infant’s sex Mother’s interactive behaviour Mother’s sensitivity 3.0 (0.8) 3.4 (0.9) 3.4 (0.9) 3.3 (0.9) 0.338 0.372 Maternal intrusiveness 3.4 (1.1) 3.6 (1.3) 3.2 (1.3) 3.6 (1.0) 0.815 0.224 Maternal remoteness 3.3 (1.0) 3.7 (1.0) 3.8 (1.0) 3.5 (1.3) 0.367 0.885 Maternal affective behaviour (depression) 3.0 (1.0) 3.3 (1.0) 3.6 (0.9) 3.3 (1.2) 0.145 0.778 Infant’s interactive behaviour Infant engagement 2.9 (1.0) 3.0 (0.9) 2.9 (0.9) 3.1 (1.1) 0.818 0.355 Infant liveliness 3.0 (0.8) 3.3 (0.9) 3.2 (0.8) 3.4 (1.0) 0.371 0.182 Infant fretfulness 3.4 (0.8) 3.8 (0.8) 3.7 (0.8) 4.3 (0.6) 0.009 0.002 Dyadic behaviour Mother—infant interaction 3.0 (1.0) 3.3 (0.9) 3.3 (0.8) 3.3 (1.2) 0.505 0.350 that depressed mothers rated their emotional bonding lower than psychotic mothers did, but no differences were found in observed mother-infant interaction. This finding was explained by the fact that depressed mothers, contrary to psychotic mothers, may have negative thoughts and low self-esteem due to their depressive symptoms, which might negatively influence their ratings. It is known that depressed mothers appear to focus mostly on the negative aspects of their infants [31], which might influence the mothers’ ratings of bonding. In our Bang- ladeshi sample, mothers with depressive symptoms were less educated and poorer than mothers without depres- sive symptoms, which might have contributed to low self-confidence in mothers with depressive symptoms and the ratings of the PBQ. Low self-esteem and feelings of worthlessness have been associated with both depres- sion and limited literacy [32]. Mothers with depressive symptoms often know that they have not been available enough for their infants, and therefore could try hard to do everything right during the observations. Thus, it may be questioned if a short video- observation is a valid representation of mother-infant interaction. A Finnish study demonstrated that a video- recording of only 5 minutes provided similar information about mother-infant interaction observed, once a week, over a year in the families’ homes during the infant’s first year [33]. Even if a mother with depressive symptoms did eve- rything right during the observation, she might not al- ways have been sensitive to her infant’s cues and as a result the infant might have accumulated negative affect and stress that was later demonstrated by the infant’s distress and fretfulness during the mother-infant interac- tion observation. Another explanation to the distress and fretfulness in the infants of mothers with depressive symptoms could be that the infants of these mothers have a more difficult temperament than infants of mothers without depressive symptoms as reported in several studies [14,34]. In this study, this is indicated by the fact that mothers with depressive symptoms rated their in- fants as more difficult to care for than the mothers in the control group. Although mothers with and without de- pressive symptoms in this sample were rated as equally sensitive, a temperamentally difficult and fussy infant may have been too challenging for the mothers with de- pressive symptoms in everyday life, particularly if the infant was a boy. In a study from Bangladesh, it was found that mothers with depressive symptoms who per ceived their infants to be irritable were less sensitive and provided their infants a less stimulating environment at home than mothers without depressive symptoms who did not perceive their infants as irritable [14]. The finding of no observed difference in interactive behavior with their infants between mothers with and without depressive symptoms is inconsistent with a study by Cooper et al. [15] from a disadvantaged suburban area in South Africa. An explanation of the difference in findings may be that mothers in rural Bangladesh, unlike those in South Africa, had relatively stable situations in terms of their living arrangements in joint families and in a society with low migration. This indicates a social network that is relatively stable and safe for the infants, who can be looked after by relatives and neighbours. Another explanation might be that the depressive symp- toms in this study were self-reported and the cutoff score (9/10) of EPDS rather low in contrast to the clinical di- agnoses according to DSM-IV conducted by Cooper et al. [15], indicating that the Bangladeshi mothers may have Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 243 had fewer depressive symptoms than the South African mothers. Although the families in our sample live in poverty, the relatively stable situation in the family and the transient maternal depressive symptoms might ex- plain the positive behaviour through the mother-infant interaction. 5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS As this case-control study of mother-infant interaction was nested in a cohort, the risk of bias imposed by retro- spective recall was reduced. The instrument, EPDS, used to assess depressive symptoms is validated in Bangla- desh [22]. Another assessment instrument, PBQ, used in this study is validated in several countries including in Asia, e.g. in China [26] and has shown good ability to discriminate between good and poor bonding, even in Bangladesh [25]. The Global Rating Scale (GRS) was chosen as it was developed to assess differences in mother-infant interaction between groups of women with and without postnatal depressive symptoms and has been successfully been used in cross-cultural settings [28]. The coders in the study did not know Bangla, which meant that verbal communications in the video record- ings had to be translated from Bangla into English. This procedure could have led to misunderstandings and in- terpretation problems. However, all translations have been checked against the videos by two bilingual (Bangla and English speaking) researchers (HN and ZNK). Half of the videos were coded in consensus, and differences in the ratings were discussed in detail. Trained Bangladeshi interviewers collected the background data and two spe- cially trained Bangladeshi social science researchers videotaped the mother-infant interactions. 6. CONCLUSION Although the mothers with depressive symptoms were poorer, were less educated and rated the emotional bonding with their infants lower than mothers without depressive symptoms, they were not objectively rated as less sensitive and responsive towards their infants than the control group. However, it should be noted that in- fants in the case group, particularly boys, were more dis- tressed and fretful in the observed interaction than in- fants in the control group. Mothers who were cases also rated themselves less confident as a mother compared to the mothers who were controls. Thus, the results indicate that it is important to identify mothers with depressive symptoms early postpartum and give them support and confirmation to increase their self-confidence as a mother, since depressive symptoms in mothers may have a nega- tive effect on the affective states of their infants. Particu- larly boys seem to be less able to self-regulate their af- fective states during the early interactions. 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Link (2007-25292-51983-33) to Karolinska Institute and the School of Pub- lic Health at BRAC University. We appreciate the help of BRAC in Bangladesh in carrying out the study. We would also like to thank all the women who participated in the study with their infants for gener- ously giving their time and energy. REFERENCES [1] Evans, J., Heron, J., Francomb, H., Oke, S. and Golding, J. (2001) Cohort study of depressed mood during preg- nancy and after childbirth. British Medical Journal, 32, 257-260. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257 [2] Rahman, A. and Creed, F. (2007) Outcome of prenatal depression and risk factors associated with persistence in the first postnatal year: Prospective study from Rawal- pindi, Pakistan. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100, 115- 121. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.004 [3] Tronick, E. and Reck, C. (2009) Infants of depressed mothers. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 17, 14-156. doi:10.1080/10673220902899714 [4] Fisher, J., de Mello, C., Patel, V., Raham, A., Tran, T., Holton, S. and Holmes W. (2012) Prevalence and deter- minants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle income countries: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90, 139-149. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.091850 [5] Patel, V., Rodrigues, M. and De Souza, N. (2002) Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa, India. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 43-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43 [6] Rahman, A., Iqbal, Z. and Harrington, R. (2003) Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: Per- spectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychological Medicine, 33, 1161-1167. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008286 [7] Gausia, K., Fisher, C., Ali, M. and Oosthuizen, J. (2009) Magnitude and contributory factors of postnatal depres- sion: A community-based cohort study from a rural sub district of Bangladesh. Psychological Medicine, 39, 999- 1007. doi:10.1017/S0033291708004455 [8] Regmi, S., Sligl, W., Carter, D., Grut, W. and Seear, M. (2002) A controlled study of postpartum depression among Nepalese women: Validation of the Edinburgh Postpar- tum Depression Scale in Kathmandu. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 7, 378-382. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00866.x [9] Lyons-Ruth, K., Zoll, D., Connell, D. and Grunebaum, H.U. (1986) The depressed mother and her one-year old infant: Environment, interaction, attachment, and infant development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 34, 6-82. [10] Murray, L. and Cooper, P. (1997) Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Archives of Disease Childhood, 77, 99-101. doi:10.1136/adc.77.2.99 [11] Murray, L. (1992) The impact of postnatal depression on Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS  M. Edhborg et al. / Health 5 (2013) 237-244 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN A CCESS 244 infant development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy- chiatry, 33, 543-561. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00890.x [12] Feldman, R., Granat, A., Pariente, C., Kanety, H., Kuint, J. and Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2009) Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psy- chiatry, 48, 919-927. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651 [13] Stein, A., Lehtonen, A., Harvey, A.G., Nicol-Harper, R. and Craske, M. (2009) The influence of postnatal psychi- atric disorder on child development. Psychopathology, 42, 11-21. doi:10.1159/000173699 [14] Black, M., Bagui, A.H., Zaman, K., McNary, S.W., Le, K., El Arifeen, S., Hamadani, J.D., Parveen, M., Yunus, M. and Black, R.E. (2007) Depressive symptoms among ru- ral Bangladeshi mothers: Implications for infant devel- opment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 764-772. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01752.x [15] Cooper, P.J., Tomlinson, M., Swartz, L., Woolgar, M., Murray, L. and Molteno, C. (1999) Post-partum depres- sion and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 554-558. doi:10.1192/bjp.175.6.554 [16] Field, T. (2010) Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting and safety practices: A review. In- fant Behavior and Development, 33, 1-6. [17] Patel, V., DeSouza, N. and Rodrigues, M. (2003) Postna- tal depression and infant growth and development in low income countries: A cohort study from Goa, India. Ar- chives of Disease in Childhood, 88, 34-37. doi:10.1136/adc.88.1.34 [18] Klainin, P. and Arthur, D.G. (2009) Postpartum depres- sion in Asian culture: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 1355-1373. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.012 [19] Gausia, K., Fisher, C., Ali, M. and Oosthuizen, J. (2009) Antenatal depression and suicidal ideation among rural Bangladeshi women: A community-based study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 12, 351-358. doi:10.1007/s00737-009-0080-7 [20] World Bank (2011) World Development Report, 2011. http://wdr2011.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/WDR201 1_Indicators.pdf [21] Cox, J.L., Holden, J.M. and Sagovsky, R. (1987) Detec- tion of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 782-786. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [22] Gausia, K., Hamadani, J.D., Islam, M.M., Ali, M., Algin, S., Yunus, M., Fisher, C. and Oosthuizen, J. (2007) Bangla translation, adaptation and piloting of Edinburgh postna- tal depression scale. Bangladesh Medical Research Coun- cil Bulletin, 33, 81-87. [23] Brockington, I.F., Oates, J., George, S., Turner, D., Vostanis, P., Sullivan, M., Loh, C. and Murdoch, C. (2001) A screen- ing questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Ar- chives of Women’s Mental Health, 3, 133-140. doi:10.1007/s007370170010 [24] Brockington, I.F., Fraser, C. and Wilson, D. (2006) The postpartum bonding questionnaire: A validation. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 233-242. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0132-1 [25] Edhborg, M., Nasreen, H.E. and Kabir, Z.N. (2011) Im- pact of postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms on mothers’ emotional tie to their infants 2 - 3 months post- partum: A population based study in rural Bangladesh. Archives of Women’s Mental Health , 14, 307-316. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0221-7 [26] Siu, B.W.-M., Ip, P., Chow, H.M.-T., Kwok, S.S.-P., Li, O.-L., Koo, M.-L., Cheung, E.F.C., Yeung, T.M.-H. and Hung, S.-H. (2010) Impairment of mother-infant relation- ship. Validation of the Chinese version of postpartum bond- ing questionnaire. Journal of Nervous and Mental Dis- ease, 198, 174-179. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d14154 [27] Murray, L., Fiori-Cowley, A., Hooper, R. and Cooper, P. (1996) The impact of postnatal depression on early mother- infant interaction and later infant outcome. Child Devel- opment, 67, 2512-2526. doi:10.2307/1131637 [28] Gunning, M., Conroy, S., Valoriani, V., Figueiredo, B., Kammerer, M.H., Muzik, M., Glatigny-Dallay, E. and Murray, L. (2004) Measurement of mother-infant interac- tions and the home environment in a European setting: Preliminary results from a cross-cultural study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 38-44. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.46.s38 [29] Frankel, K.A. and Harmon, R.J. (1996) Depressed moth- ers: They don’t always look as bad as they feel. Journal of the Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 289- 298. doi:10.1097/00004583-199603000-00009 [30] Hornstein, C.H., Trautman-Villa, P., Hohn, E., Rave, E., Wortmann-Fleischer, S. and Schwarz, M. (2006) Mater- nal bond and mother-child interaction in severe postpar- tum psychiatric disorders: Is there a link? Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 279-284. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0148-6 [31] Field, T. (1995) Infants of depressed mothers. Infant Be- havior and Development, 18, 1-13. doi:10.1016/0163-6383(95)90003-9 [32] Francis, L., Weiss, B.D., Senf, J.H., Heist, K. and Har- graves, R. (2007) Does literacy education improve symp- toms of depression and self-efficacy in individuals with low literacy and depressive symptoms? A preliminary in- vestigation. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 20, 23-27. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060058 [33] Kemppinen, K., Kumpulainen, K., Räsänen, E., Moilanen, I., Ebeling, H., Hiltunen, P. and Kunelius, A. (2005) Mother-child interaction on video compared with infant observation: Is five minutes enough time for assessment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 69-81. doi:10.1002/imhj.20031 [34] Edhborg, M., Seimyr, L., Lundh, W. and Widström, A.-M. (2000) Fussy child—Difficult parenthood? Comparisons between families with a “depressed” mother and non-de- pressed mother two months postpartum. Journal of Re- productive and Infant Psychology, 18, 225-238. doi:10.1080/713683036

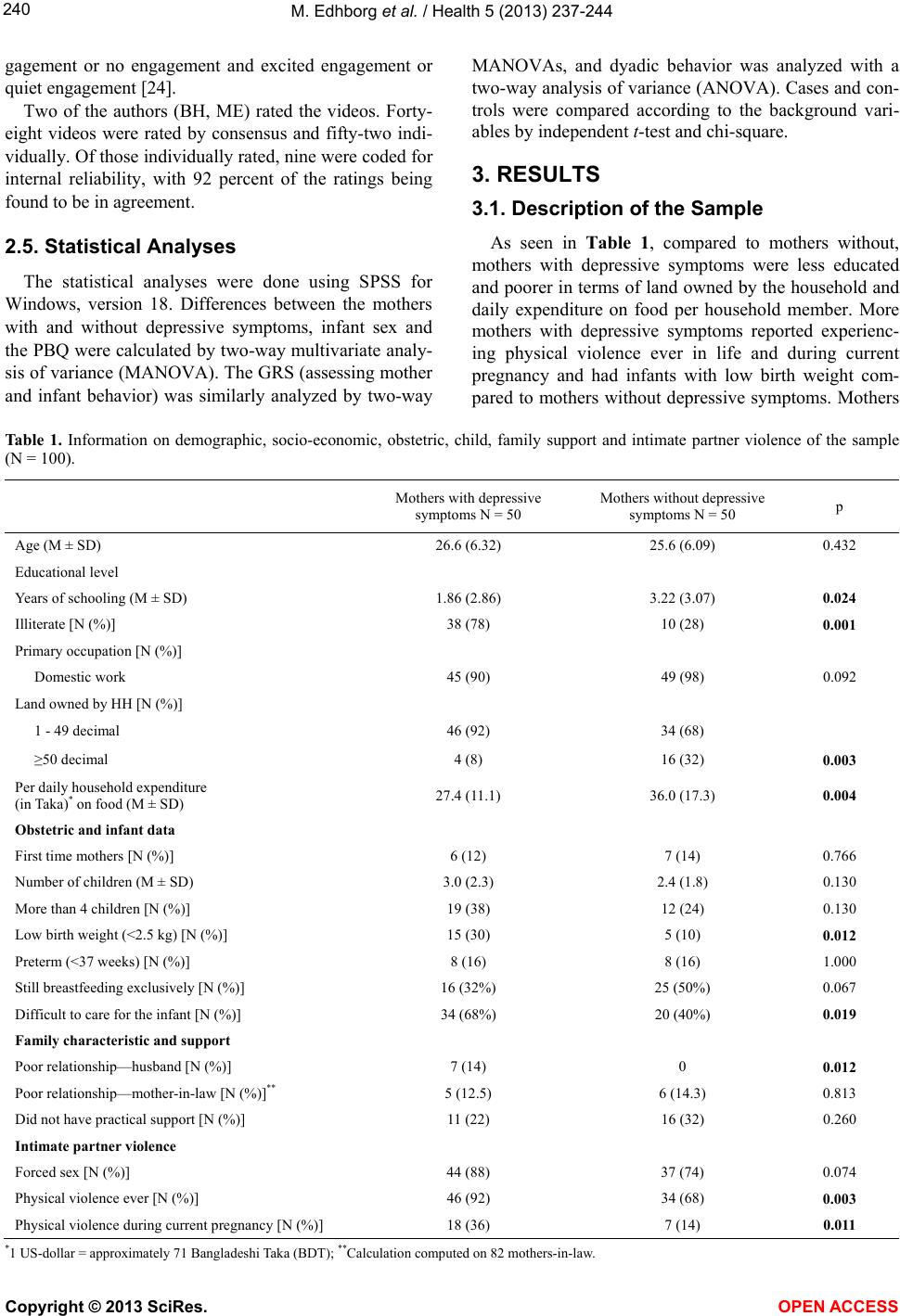

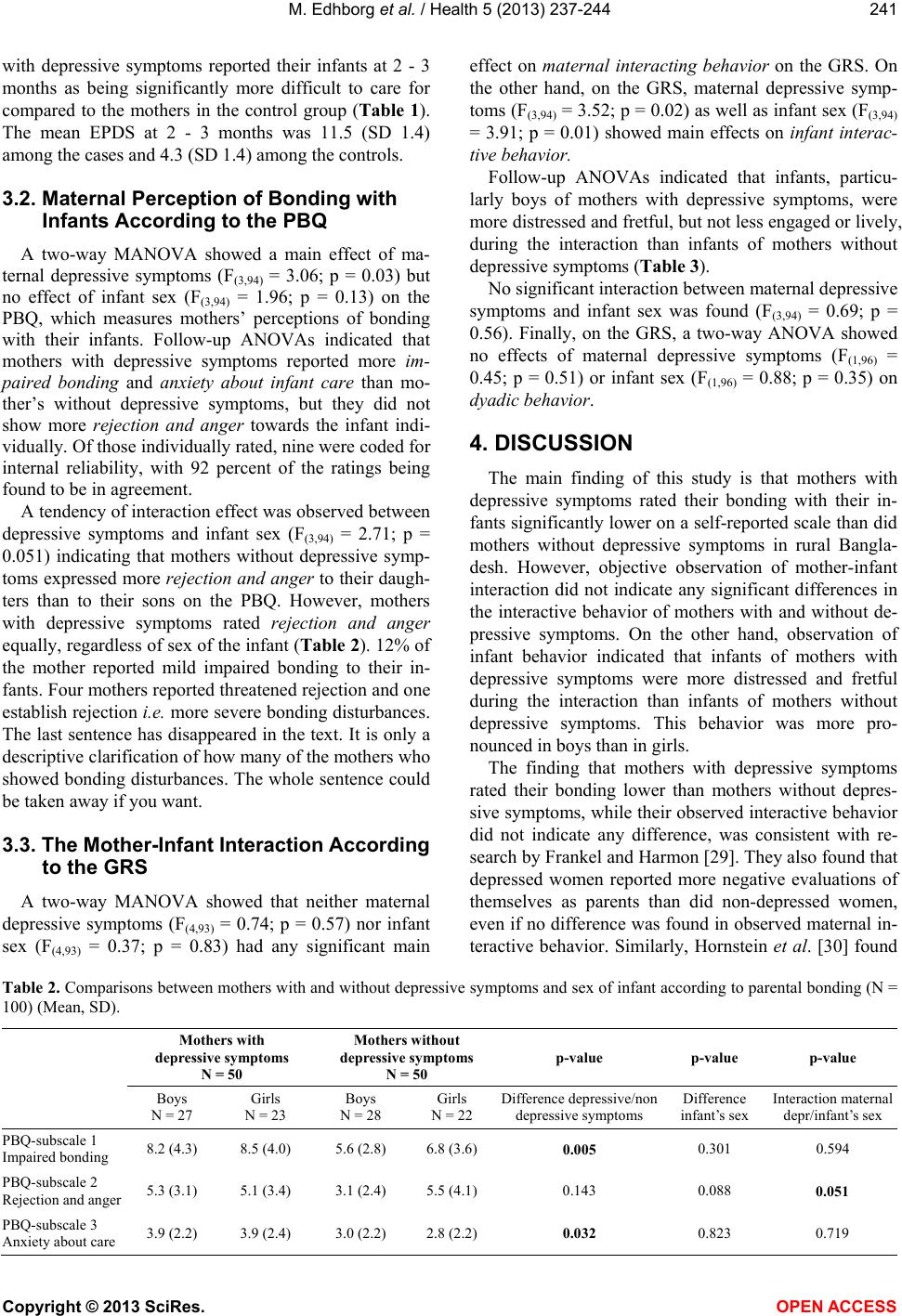

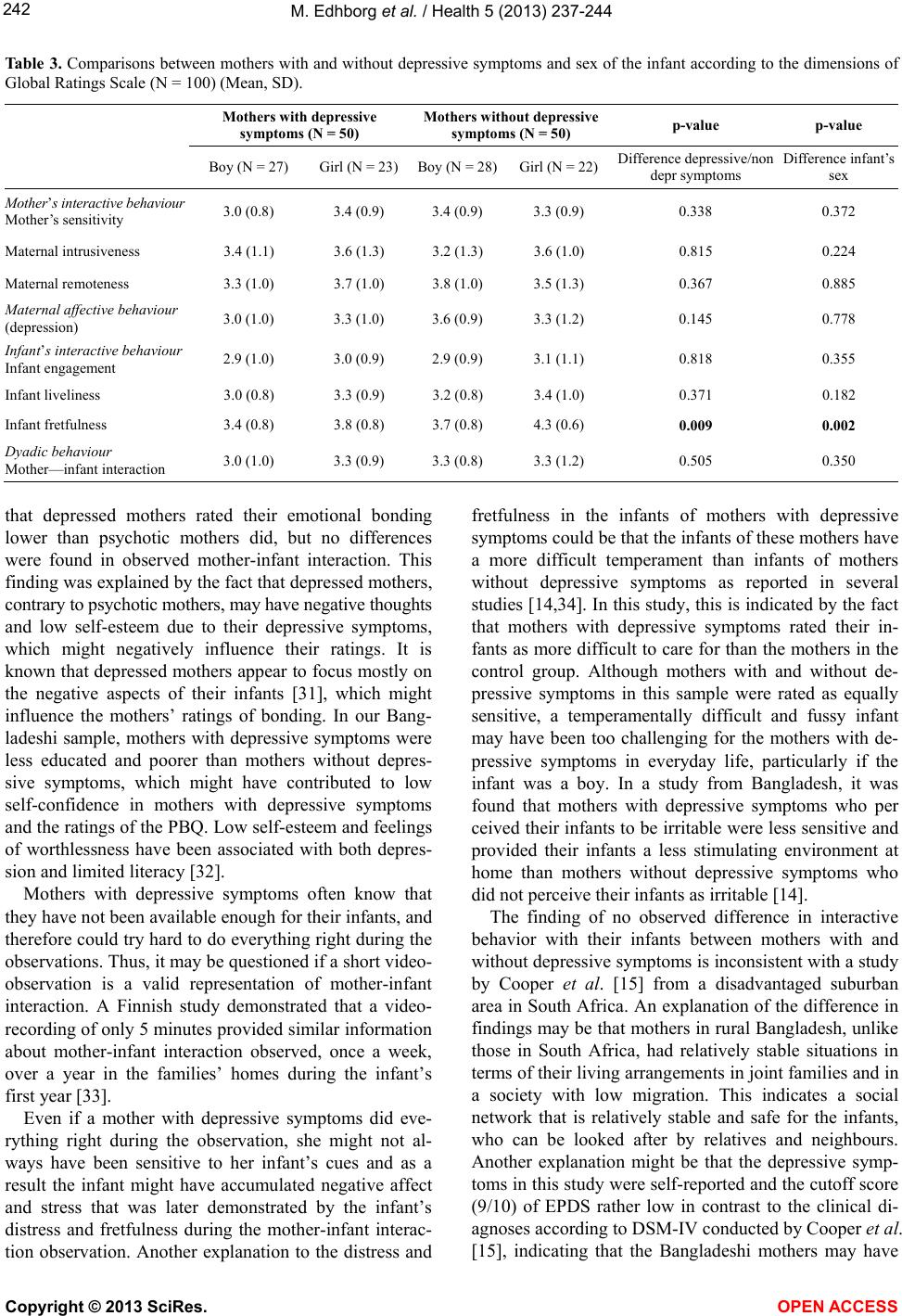

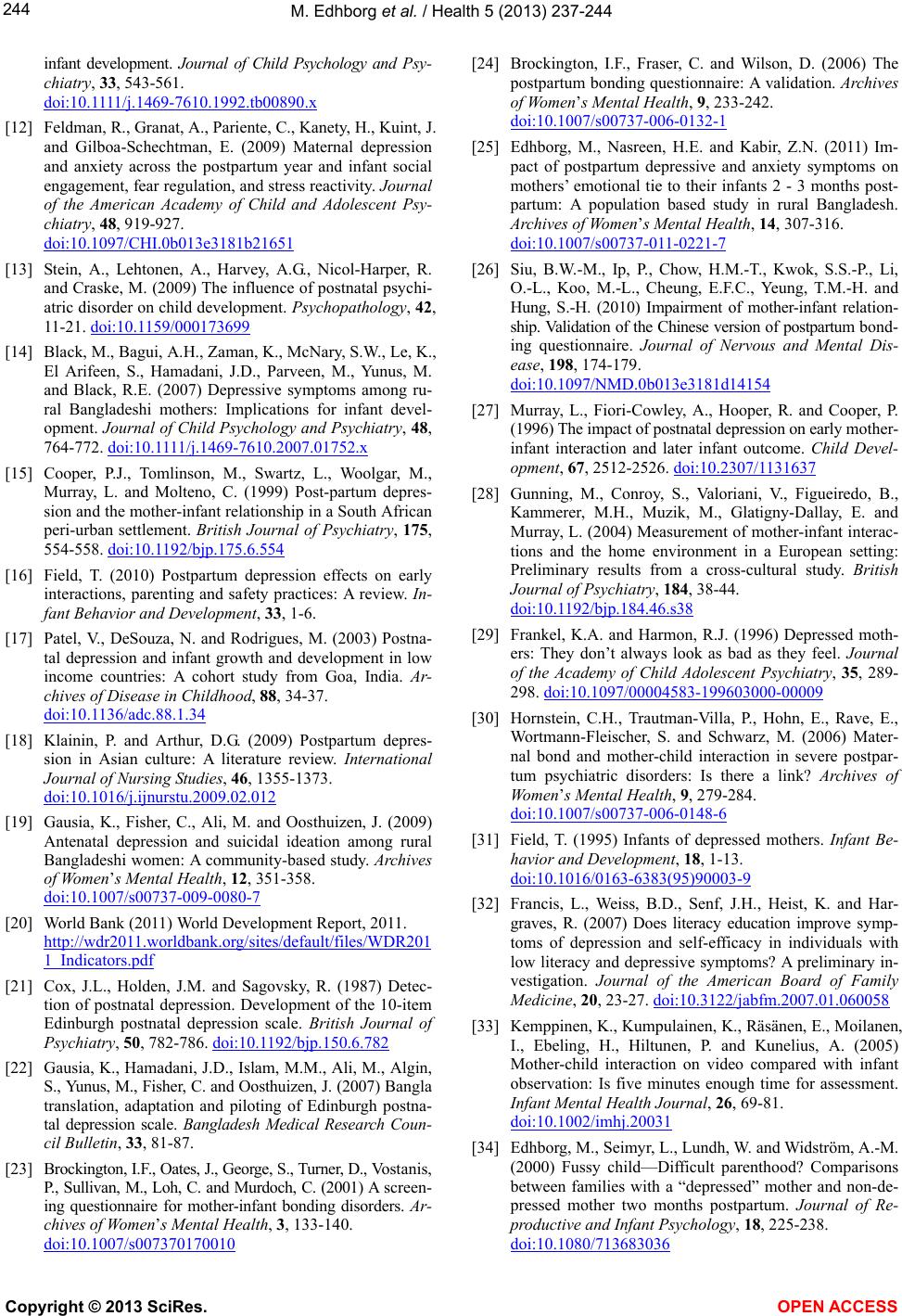

|