Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

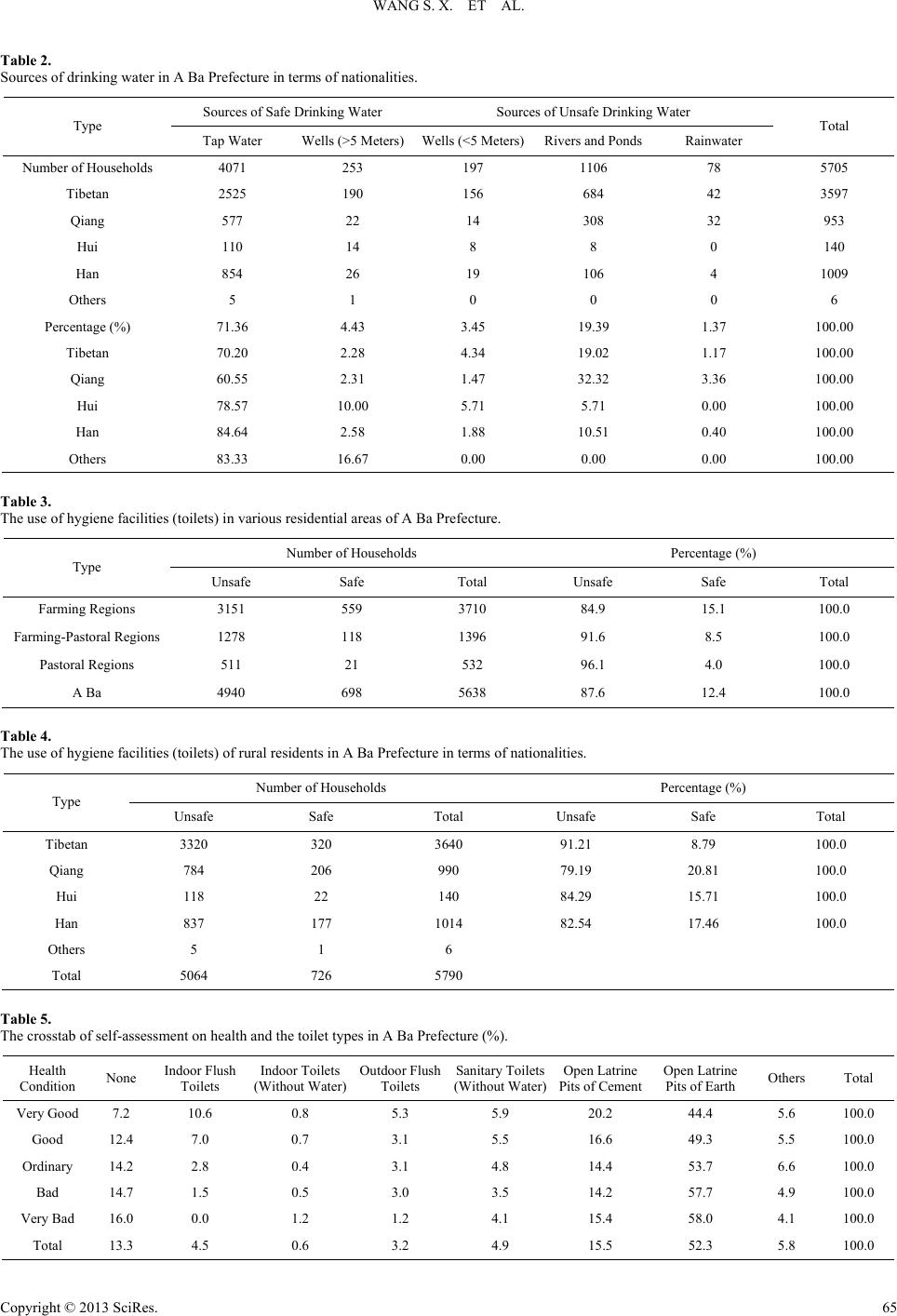

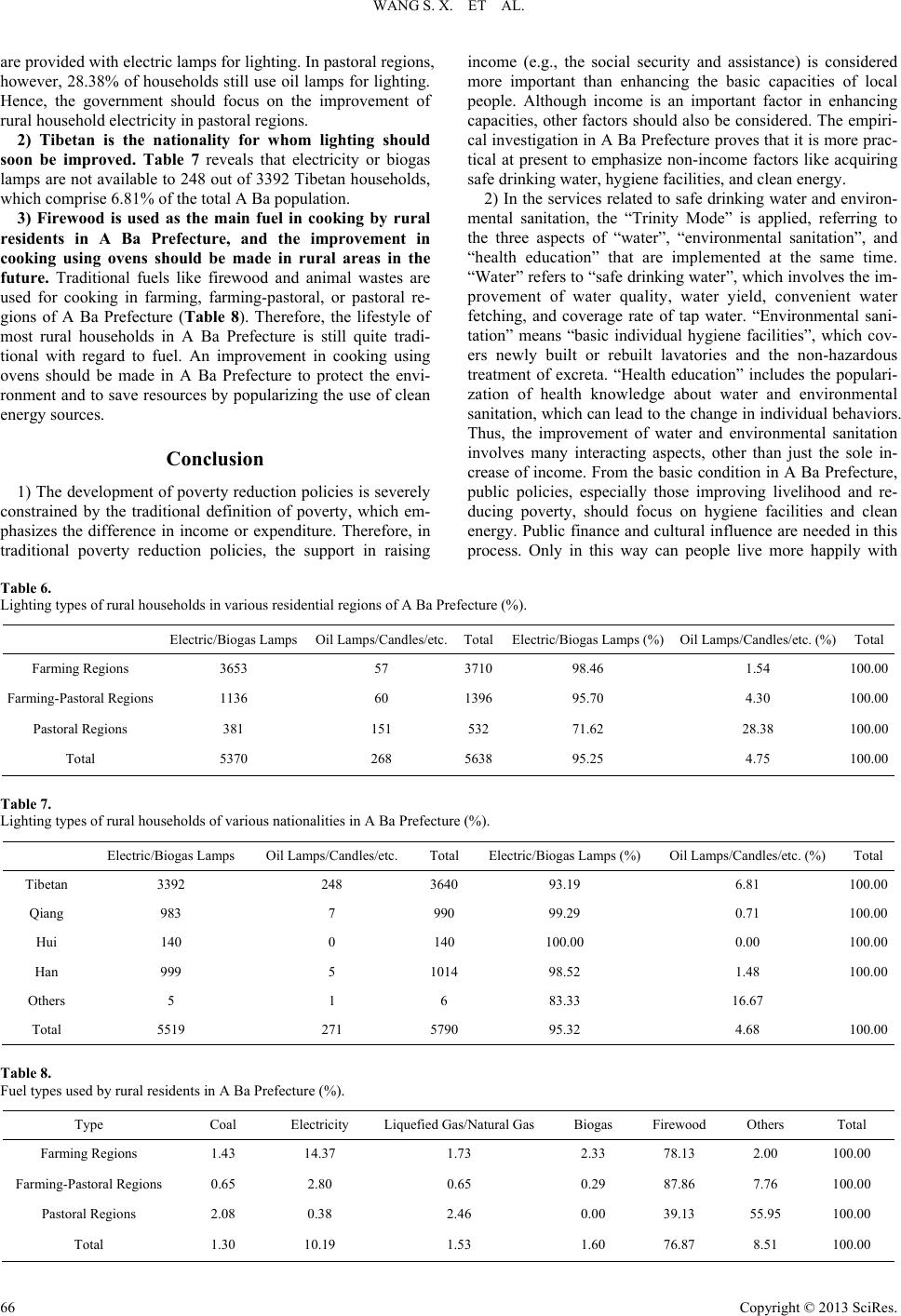

Chinese Studies 2013. Vol.2, No.1, 61-67 Published Online February 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/chnstd) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2013.21009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 61 Poverty Assessment in Terms of Safe Drinking Water, Hygiene Facilities, and Energy of Minority Nationalities* ————A Case Study on the A Ba Autonomous Prefecture of Tibetan and Qiang Nationalities Wang Suxia1, Zhou Xianghong2#, Wang Xiaolin3, Shao Zirui2 1Center for Human and Ec o n omic Development S t u di e s , B e i j in g , China 2Department of Public Management, Tongji University, Shanghai, China 3International Poverty Reduction Center in China, Beijing, China Email: #xhz7@tongji.edu.cn Received November 9th, 2012; revised December 11th, 2012; accepted December 18th, 2012 Since 2002, the Trinity Mode has been adopted in China to include safe drinking water and sanitation ser- vices in order to change the services into public products of rural communities. These products would contain multi-valued attributes of miniature infrastructure constructions, primary health care, and eco- logical protection. Poverty reduction demands different policies with extended connotation and changed features, from increasing income to improving welfare services, from a macroscopic to a microscopic viewpoint, from the national level to that of communities, and from the indistinguishable to an individual. Against such background, A Ba Prefecture is selected as the case study area. Safe drinking water and sanitation services, the most important components of basic public health services, are selected as the re- search object in the study, and both sanitation and health are included in the framework to analyze pov- erty. Altogether, 5637 valid questionnaires of “The Investigation on Poverty Alleviation in A Ba Prefec- ture in 2009” have been carefully studied. The study shows that great achievements have been made in alleviating poverty in A Ba by improving the drinking water in rural areas. However, a huge amount of work is needed to apply hygiene facilities and popularize clean energy. Hence, the government’s antipov- erty policies should be strengthened in the latter two aspects. Keywords: Minority Nationalities; Safe Drinking Water; Hygiene Facilities; Energy; Poverty Introduction As important components of the Millennium Development Goal (MDG), safe drinking water and environmental sanitation were included in the “health-related public services and facili- ties” category of the “Poor Urban Population and Health in Developing Countries” report published in June 2009. As Global Public Goods, services related to water and sanitation have been recognized by various international organizations and have been incorporated into governmental agendas in dif- ferent countries. As early as the 1980s, the effort to improve the services related to safe drinking water and environmental sani- tation has been regarded as an important strategy in alleviating poverty. Related work was later considered to be part of pov- erty reduction in financially supported countries when the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund started the Poverty Reduction Strategy in 1999. Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel Peace Prize Winner, created “Sixteen Decisions” in 1984, which determines whether one client can make a loan from the Grameen Bank and whether clients have successfully reduced poverty. An important index in the criteria of “Sixteen Deci- sions” was the improvement of water and environmental sanita- tion, which is also a main part of the poverty reduction program in China in the mid-1990s. The Poverty Relief Office of the State Council pointed the condition of drinking water for hu- man beings and livestock as one participatory poverty index in the poverty reduction of 27 provinces/autonomous regions, together with the coverage of electricity and roads in villages. In recent years, the improvement of water and environmental sanitation in China has been regarded as the main component of poverty reduction by such organizations as the World Bank, the United Nations Children’s Fund, the Asian Development Bank, and the United Kingdom’s Department for International De- velopment. In this field, the Poverty Relief Office, the National Development and Reform Committee, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Water Resources have increased their sup- port in policy and finance (National Center for Rural Water Supply Technical Guidance, 2006). The improvement of water and sani- tation is mentioned in “The New Scheme of Medical Reform” to promote the equalization of public health services. Poverty caused by the lack of energy has a potential impact on health. Access to safe and reliable energy is necessary in an industrial society, though it is not part of the MDG. Energy has a significant influence on ordinary people’s welfare, such as controlling indoor temperature, watching TV, acquiring drink- ing water and hygiene facilities, and having access to tele- phones and the Internet, all of which can improve their life condition and health status considerably. The lack of energy results in two different aspects of poverty: 1) clean energy like electricity, gas, and solar energy cannot be reached; and 2) energy consumption takes up too much in a Household Con- sumption Expenditure, influencing the effective energy utiliza- *This paper is the initial result from the item of National Natural Science Fundation of China (71073111/G0308) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (20100470142). #Correspo n ding author.  WANG S. X. ET AL. tion. Kaiser and Pulsipher concluded that energy consumption takes up 5% of the family income in middle-high income fami- lies, 10% in low-income families, and as high as 20% in ex- tremely poor families. Low-income families can hardly cope with the fluctuation of petroleum prices. Since the 2008 finan- cial crisis, the petroleum price has risen sharply. Recent con- flicts in Northern Africa and Middle East countries also push the soaring price even higher, thus posing more challenges worldwide for poor families, especially for children (Wang Xiaoling & Shang Xiaoyuan, 2011). The lack of safe drinking water, hygiene facilities, and clean energy seriously threatens the health of poor people. Improving the dr inking water, hygien e facilities, and energy conditions for poor people has become an important strategy for poverty re- duction. Therefore, a case study is conducted in the A Ba Autonomous Prefecture of Tibetan and Qiang Nationalities. Poverty assessment with multidimensional measurement is performed on drinking water, hygiene facilities, and clean en- ergy in the residential regions of Tibetan and Qiang to provide references for formulating antipoverty policies in poverty- stricken areas. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework Literature Review Scholars at home and abroad have noticed the close connec- tion between poverty relief and the improvement of water and environmental sanitation. Services relating to safe drinking water and environmental sanitation are cheap or free public services that can be provided for low-income people, and are an investment-oriented redistribution of income. To date, related studies are being carried out around the following points: 1) The cost-benefit approach and the econometric model can prove that services related to safe drinking water and environmental sanitation possess not only social benefits, but also significant economic benefits. Hutton (National Center for Rural Water Supply Technical Guid- ance, 2006), Fenwick, Sagar, and other scholars from the World Bank, the World Health Organization, and the Asian Develop- ment Bank have assessed the projects that improve water and environmental sanitation in some developing countries in Af- rica and Asia, and have found that all the services have signifi- cant economic benefits. Hutton, Haller, and Bartram have as- sessed the input and output of water and environmental sanita- tion using the cost-benefit approach, and have cited that in cer- tain developing regions, a one-dollar input may bring 5 to 46 dollars in return. With the help of the Bayesian theory, Paul, Hunter, Pond, and Jagals John found that the proportion of benefits to cost is 2.78 in terms of improving safe drinking water and environmental sanitation in some areas in the three developed countries. Using a comparative method and epidemics assessment, do- mestic scholars like Tao Yong (2005), Lu Huang-Xiang, and Zhang Zhi-Yong have analyzed the positive benefits of im- proving water and environmental sanitation, such as preventing diseases, reducing the time for fetching water, enriching the hygiene knowledge of ordinary people. Water conservancy scholars like Yang Xiao-Liu (2004) and Zhang Ji-Jun (2006) have measured the cost and benefits of potable water projects using basic theories in architectural engineering. Based on the observation, economists in agriculture and forestry, like Chen Mo, Zhang Lin-Xiu, Qu Yin-Li, and Luo Ren-Fu, have con- cluded that the enhancement of rural residents’ health is deter- mined by the provision of safe and reliable domestic water. 2) Services related to safe drinking water and environ- mental sanitation play an important role in relieving pov- erty and vulnerability. Peter Harvey based his study in sub-Saharan Africa on lit- erature analysis and empirical study, and found the close con- nection between poverty relief and the improvement of water and environmental sanitation. The sustainable improvement of water and environmental sanitation were highlighted as the keys to relieving poverty. Through abundant empirical study, domestic scholars such as Li Bin, Li Xiao-Yun, and Zuo Ting proved that the lack of safe water and environmental sanitation lessened poverty reduction, and worse, broke its persistence. Zhou Xiang-Hong (2009) probed into the effect of the im- provement of water and environmental sanitation on reducing the vulnerability of poor rural areas in China through literature analysis and case study. Recently, an empirical study on the national conditions survey of Village Li in Jiangsu Province was performed by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The study indicated that besides strengthening infrastructure construction and agricultural insurance, antipoverty policies should involve popularizing knowledge on hygiene, health, nutrition, and childcare, increasing the investment in medical services, improving basic medical treatment and public health, and raising the general level of impoverished people’s health even without enough material conditions. Han Zheng (2004) mentioned that the rural population in China was gradually el imina ting pover ty, b ut was still highly vulnerable. Meanwhile, compared to traditional poverty-reduction policies (e.g., new rural cooperative medical system, social assistance, etc.), ele- mentary health care (e.g., services related to safe drinking water and environmental sanitation) can be realized in advance through interventions. Advance intervention can effectively identify groups that will soon sink into poverty and relieve the long-term poverty of an impoverished population. Moreover, it can raise the effectiveness of policies while reducing the cost. 3) Services related to safe drinking water and environ- mental sanitation can promote the capacity building of an impoverished population. Empowerment was initially regarded as one of the three mainstays of poverty reduction in the World Bank’s “World Development Report of 2000/2001”. Since the report, many scholars have tried to include empowerment in the discussion of poverty reduction. In Measuring Empowerment in Practice: Structuring Analysis and Framing Indicators (WPS 3510), Ruth Alsop and Nina Heinsohn stated that the capacity of individuals and organizations can be enhanced significantly in water and environmental sanitation projects. The United Nations Chil- dren’s Fund and other international organizations have all em- phasized the effect of the Trinity Mode on the capacity building of an impoverished population in improving water and envi- ronmental sanitation in China. Women in the selected villages of Shanxi and Yunnan were observed to have more confidence after joining the work to improve water and environmental sanitation. In rural India, Bennett and Gajurel found that the Dalits and Janajatis women were empowered with the interven- tion of water supply and hygiene projects, and thus enjoyed more social inclusion. 4) The Application of Multidimensional Poverty Meas- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62  WANG S. X. ET AL. urement and the Quantization of its Main Dimensions. Since the 1970s and 1980s, the Physical Quality of Life In- dex, Human Development Index, mode of basic needs, inte- grated rural development, and comprehensive development program have been used widely as multidimensional indicators. These indicators include various dimensions of life—lifespan, knowledge, and dignity, among others—though each compre- hensive indicator has its own focus. Based on the poverty relief practice in Qinghai Province, Hu An-Gang (2004) classified poverty into four classes: income poverty, human poverty, in- formation poverty, and ecological poverty. According to the 17 indicators of the four classes, a comprehensive measurement was formed to conduct a quantitative calculation of poverty reduction in Qinghai. Chen Li-Zhong (2008) chose the Watts Multidimensional Poverty Indicator and its decomposition after co mp a r i ng t he H- M I n de x , HPI Index, CH- M Index, F- M Index, and W-M Index. The multidimensional indicators of knowledge poverty, health poverty, and income poverty were established. The current conditions of some poverty-stricken towns in China were measured using the newly established indicators. Wang Xiao-Lin (2010) measured the multidimensional poverty in urban and rural families in China using the framework in “Counting and Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty” by Alkire and Foster (2008) of Oxford University, and mentioned that other kinds of multidimensional poverty exist besides in- come poverty. In recent years, vulnerability, social capital, and other quan- titative measurements of main dimensions within the multidi- mensional system have become important topics in academic study. In 1995, the World Food Program has proposed an ana- lytical framework of an impoverished population’s vulnerabil- ity, showing that the higher the risk of an impoverished popula- tion, the higher their vulnerability will be. Dercon (2001) cre- ated an analytical framework of risks and vulnerability, in which the farmers’ risks mainly include asset risks (human assets, land assets, material assets, financial assets, public goods, and social assets), income risks (profitable activities, assets returns, assets disposal, savings-investment, remittance transfer, and economic opportunities), and welfare risks (nutria- tion, health, education, social exclusion, and capability depriva- tion). This framework places the farmers’ resources, income, consumption, and corresponding institutional arrangement into one system (Chen Chuang-Bo, 2005). Li Xiao-Yun (2005) studied the qualitative analysis on the vulnerability of impover- ished peasant households using the framework of sustainable livelihood of peasants, and then designed the quantitative study on the livelihood assets of peasant households to perform a quantitative analysis on the peasants’ vulnerability. Theoretical Framework “Poverty” is defined as “one’s state of lacking a certain amount of or acceptable amount of material possessions or money” in Encyclopedia Briton NICA. It is also defined as “the phenomenon of being deprived of welfare” by the World Bank (World Bank, 2009). The definition of “poverty,” therefore, is determined by how many material possessions or money is acceptable in the society. Due to the restriction of the accessi- bility and measurement of data, poverty and welfare have been calculated by the monetary standard of average income or con- sumption. Thus, poverty means that the income or consumption meeting basic needs is lower than a certain amount of money. On account of this logical analysis, antipoverty policies and welfare policies evolve around income-support policies. This logical thinking has seriously confined the development of antipoverty policies. Amartya Sen cited that poverty is more about the deprivation of basic capacities than low income. The deprivation of basic capacities can be manifested by premature mortality rate, evi- dent malnutrition (especially for children), persistent incidences of diseases, and other shortages (Sen, 1985). Both definitions of poverty and the strategies of poverty relief have been extended under Sen’s framework of capacities. In the United Nations’ MDG in 2000, it was clearly stated that “by 2015, the rate of unsustainable access to safe drinking water and basic hygiene facilities should be halved,” which can be regarded as a land- mark. The United Nations regards the lack of safe drinking water and basic hygiene facilities as one primary dimension of poverty. Similarly, the health of an impoverished population is influenced negatively due to the use of animal wastes, straw, firewood, and raw coal as fuel in poverty-stricken households, causing serious damage to the environment. Therefore, the use of clean energy is also an important subject under discussion concerning poverty and development. Since Sen proposed the concept of depriving basic capacities, great progress has been made in the understanding of poverty. In certain regions, however, some major dimensions of poverty, such as hygiene facilities and clean energy, have not been widely accepted in public policies. Safe drinking water, hygiene facilities, and clean energy are the main blocks in building an overall prosperous society and improving living standards, especially in m inority areas. In this article, the logical framework is set as “poverty—the deprivation of welfare—basic needs—basic capacities”. The capacities of acquiring safe drinking water, hygiene facilities, and clean energy are confirmed as the basic capacity to be used as primary dimensions in antipoverty strategies. Under this theoretical framework, the state of poverty in A Ba Autono- mous Prefecture is analyzed in terms of minorities and gender. Data In this article, the survey data of “The Investigation on Pov- erty Alleviation in A Ba Prefecture in 2009” were used, cover- ing the 1351 villages of 13 counties in A Ba Prefecture. Of the 6755 total questionnaires, only 5637 valid questionnaires were returned. Analysis and Results Drinking Water and Health 1) Great achievements in safe drinking water in A Ba Prefecture. In this report, tap water and wells deeper than five meters are considered as sources of safe drinking water, whereas rainwater, rivers, ponds, and wells with depths of less than 5 meters were considered as sources of unsafe drinking water. “The Investigation on Poverty Alleviation in A Ba Pre- fecture in 2009” shows that 75.5% of water sources in A Ba is safe, 71% of which are comprised of households with tap water (Table 1). 2) Great Achievements in Public Investments for Pov- erty-Relief Development. Due to the success of several pro- jects (i.e., the investment for poverty-relief development, the integrated control of the Kaschi disease, the improve- n-Beck Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  WANG S. X. ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64 Table 1. Sources of drinking water in various residential ar eas of A Ba Prefecture. Sources of Safe Drinking Water Sources of Unsa fe Drinking Wa ter Type Tap Water Wells (>5 Me ters)Wells (<5 Meters)Rivers and PondsRainwate r Total Number of Households 3946 248 196 1089 77 5556 Agricultural Regions 2807 94 77 614 58 3650 Farming-Pastoral Regions 981 66 73 243 15 1378 Pastoral Regions 158 88 46 232 4 528 Percentage (%) 71.02 4.46 3.53 19.60 1.39 100.00 Farming Regions 76.90 2.58 2.11 16.82 1.59 100.00 Farming-Pastoral Regions 71.19 4.79 5.30 17.63 1.09 100.00 Pastoral Regions 29.92 16.67 8.71 43.94 0.76 100.00 ment of water and toilets in rural areas), the rate of using tap water in rural areas of A Ba has clearly increased. In the past, people in A Ba’s endemic areas had to drink high-fluorine wa- ter or substandard water. This problem was included in the livelihood project of A Ba in 2008, together with the invest- ments on poverty-relief development and the integrated control of the Kaschin-Beck disease. By the end of November 2008, 521 safe drinking water projects had been completed, providing safe drinking water to 85,000 local people (The Web Portals of the Government of A Ba Prefecture, 2009). 3) Challenges of Safe Drinking Water Supply for Rural Residents. In recent years, 75% of the households have gained access to safe drinking water through poverty-relief develop- ment. However, 24.4% of the households still do not have ac- cess to safe drinking water, 3.53% drink water from wells no deeper than five meters, 19.60% drink water from rivers and ponds, and 1.39% drink rainwater. 4) Pastoral Regions—The Area of Focus in the Improve- ment of Safe Drinking Water Supply. Table 1 shows that a connection exists between drinking water and residential re- gions. Only 29.9% of the households in pastoral regions have access to tap water while 53.4% have to endure unsafe water sources (wells no deeper than five meters, rivers, ponds, and rainwater). This is a serious problem in A Ba prefecture be- cause safe drinking water has a close connection with health. 5) Qiang and Tibetan—The Minority Nationalities fo- cused on in the Improvement of Safe Drinking Water. Ta- ble 2 shows that the condition of safe drinking water in the Han and Hui residential regions is better than those in Qiang and Tibetan. A total 37.5% and 24.53% of households in the resi- dential regions of Qiang and areas of Tibet, respectively, have unsafe drinking water. In Han area, the condition is better, with only 12.79% of households taking unsafe drinking water. The Hui area has the best condition, with only 11.42% of the households taking unsafe drinking water. Hygiene Facilities and Health 1) A small proportion of rural households in A Ba Pre- fecture use safe hygiene facilities. Table 3 shows that the rural households with safe hygiene facilities only take up 12.4%, i.e., 87.6% households have no hygiene facilities. Compared with the data of different residential regions, more households in farming regions adopt safe hygiene facilities than those in pastoral and farming-pastoral regions. However, the general condition of A Ba Prefecture is not satisfactory, and it faces a difficult task of improving toilets in rural areas. Altogether, 87.6% of the households need improvement of toilets, and the rate becomes 96.1% in pastoral regions. 2) In terms of unsafe hygiene facilities, Tibetan residents have the highest rate while Qiang residents have the lowest. The ra t e s o f us i ng un s afe hygiene facilities in Tibetan, Hui, Han, and Qiang residential regions are 91.21%, 84.29%, 82.54%, and 79.19%, respectively. For most urban residents, flush toilets are already a part of their lives, but not for rural residents in A Ba Prefecture. The United Nations regards unsafe hygiene facility as an important factor that endangers health. Therefore, the rate of unsustainable access to basic hygiene facilities in MDG should be halved by 2015. Unfortunately, the use of unsafe hygiene facilities is often underestimated in the public policies of poverty-stricken areas. Unsafe hygiene facility, like unsafe drinking water, is also a main factor that causes epidemic dis- eases such as malaria and dysentery. 3) There is a positive correlation between the type of toi- lets and the health condition of rural residents in A Ba Pre- fecture. Table 5 shows the comparison of the self-assessment of rural residents on their own health based on the types of toilets used. The table shows that the group who chose “very good” for their health conditions has the highest proportion (10.6%) of using indoor flush toilets. In contrast, those who chose “very bad” for their health conditions have the highest proportion of using open latrine earth pits (16.0%) or have no toilets at all (58.0%). Among the 169 households who chose “very bad” for their health conditions, none uses indoor flush toilets. This phenomenon is connected with the economic con- dition, i.e., better-off households tend to use “indoor flush toi- lets.” Therefore, there is a certain connection between the type of toilets and the health condition of rural residents, which proves that government intervention is needed in the improve- ment of lavatories of impoverished rural residents. Lighting and Fuel 1) Electricity for lighting is not available to a quarter of rural residents in pastoral regions of A Ba Prefecture. Ta- ble 6 shows that 95.5% of rural ouseholds in A Ba Prefecture h  WANG S. X. ET AL. Table 2. Sources of drinking water in A Ba Prefecture in terms of nationalities. Sources of Safe Drinking Water Sources of Unsa fe Drinking Wa ter Type Tap Water Wells (>5 Me ters)Wells (<5 Meters)Rivers and PondsRainwate r Total Number of Households 4071 253 197 1106 78 5705 Tibetan 2525 190 156 684 42 3597 Qiang 577 22 14 308 32 953 Hui 110 14 8 8 0 140 Han 854 26 19 106 4 1009 Others 5 1 0 0 0 6 Percentage (%) 71.36 4.43 3.45 19.39 1.37 100.00 Tibetan 70.20 2.28 4.34 19.02 1.17 100.00 Qiang 60.55 2.31 1.47 32.32 3.36 100.00 Hui 78.57 10.00 5.71 5.71 0.00 100.00 Han 84.64 2.58 1.88 10.51 0.40 100.00 Others 83.33 16.67 0.00 0.00 0.00 100.00 Table 3. The use of hygiene facilities (toilets) in various residential areas of A Ba Prefecture. Number of Households Percentage (%) Type Unsafe Safe Total Unsafe Safe Total Farming Regions 3151 559 3710 84.9 15.1 100.0 Farming-Pastoral Regions 1278 118 1396 91.6 8.5 100.0 Pastoral Regions 511 21 532 96.1 4.0 100.0 A Ba 4940 698 5638 87.6 12.4 100.0 Table 4. The use of hygiene facilities (toilets) of rural residents in A Ba Prefecture in terms of nationalities. Number of Households Percentage (%) Type Unsafe Safe Total Unsafe Safe Total Tibetan 3320 320 3640 91.21 8.79 100.0 Qiang 784 206 990 79.19 20.81 100.0 Hui 118 22 140 84.29 15.71 100.0 Han 837 177 1014 82.54 17.46 100.0 Others 5 1 6 Total 5064 726 5790 Table 5. The crosstab of self-assessment on health and the toilet types in A Ba Prefecture (%). Health Condition None Indoor Flush Toilets Indoor Toilets (Without Water) Outdoor F lus h Toilets Sanitary Toilets (Without Water)Open Latrine Pits of CementOpen Latrine Pits of Earth Others Total Very Good 7.2 10.6 0.8 5.3 5.9 20.2 44.4 5.6 100.0 Good 12.4 7.0 0.7 3.1 5.5 16.6 49.3 5.5 100.0 Ordinary 14.2 2.8 0.4 3.1 4.8 14.4 53.7 6.6 100.0 Bad 14.7 1.5 0.5 3.0 3.5 14.2 57.7 4.9 100.0 Very Bad 16.0 0.0 1.2 1.2 4.1 15.4 58.0 4 .1 100.0 Total 13.3 4.5 0.6 3.2 4.9 15.5 52.3 5.8 100.0 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  WANG S. X. ET AL. are provided with electric lamps for lighting. In pastoral regions, however, 28.38% of households still use oil lamps for lighting. Hence, the government should focus on the improvement of rural household electricity in pastoral regions. 2) Tibetan is the nationality for whom lighting should soon be improved. Table 7 reveals that electricity or biogas lamps are not available to 248 out of 3392 Tibetan households, which comprise 6.81% of the total A Ba population. 3) Firewood is used as the main fuel in cooking by rural residents in A Ba Prefecture, and the improvement in cooking using ovens should be made in rural areas in the future. Traditional fuels like firewood and animal wastes are used for cooking in farming, farming-pastoral, or pastoral re- gions of A Ba Prefecture (Table 8). Therefore, the lifestyle of most rural households in A Ba Prefecture is still quite tradi- tional with regard to fuel. An improvement in cooking using ovens should be made in A Ba Prefecture to protect the envi- ronment and to save resources by popularizing the use of clean energy sources. Conclusion 1) The development of poverty reduction policies is severely constrained by the traditional definition of poverty, which em- phasizes the difference in income or expenditure. Therefore, in traditional poverty reduction policies, the support in raising income (e.g., the social security and assistance) is considered more important than enhancing the basic capacities of local people. Although income is an important factor in enhancing capacities, other factors should also be considered. The empiri- cal investigation in A Ba Prefecture proves that it is more prac- tical at present to emphasize non-income factors like acquiring safe drinking water, hygiene facilities, and clean energy. 2) In the services related to safe drinking water and environ- mental sanitation, the “Trinity Mode” is applied, referring to the three aspects of “water”, “environmental sanitation”, and “health education” that are implemented at the same time. “Water” refers to “safe drinking water”, which involves the im- provement of water quality, water yield, convenient water fetching, and coverage rate of tap water. “Environmental sani- tation” means “basic individual hygiene facilities”, which cov- ers newly built or rebuilt lavatories and the non-hazardous treatment of excreta. “Health education” includes the populari- zation of health knowledge about water and environmental sanitation, which can lead to the change in individual behaviors. Thus, the improvement of water and environmental sanitation involves many interacting aspects, other than just the sole in- crease of income. From the basic condition in A Ba Prefecture, public policies, especially those improving livelihood and re- ducing poverty, should focus on hygiene facilities and clean energy. Public finance and cultural influence are needed in this process. Only in this way can people live more happily with Table 6. Lighting types of rural households in vari ou s residential regions o f A Ba Prefecture (%). Electric/Biogas Lamps Oil Lamps/Candles/etc.TotalElectric/Biogas Lamps (%)Oil Lamps/Candles/etc. (%)Total Farming Regions 3653 57 371098.46 1.54 100.00 Farming-Pa storal Regions 1136 60 139695.70 4.30 100.00 Pastoral Regions 3 81 151 532 71.62 28.38 100.00 Total 5370 268 563895.25 4.75 100.00 Table 7. Lighting types of rural households of various nationalities in A Ba Prefecture (%). Electric/Biogas Lamps Oil Lamps/Candles/etc. Total Electric / Biogas Lamps (%)Oil L amps/Candles/etc. (%) Total Tibetan 3392 248 3640 93.19 6.81 100.00 Qiang 983 7 990 99.29 0.71 100.00 Hui 140 0 140 100.00 0.00 100.00 Han 999 5 1014 98.52 1.48 100.00 Others 5 1 6 83.33 16.67 Total 5519 271 5790 95.32 4.68 100.00 Table 8. Fuel types used by rural residents in A Ba Prefecture (%). Type Coal Electricity Liquefied Gas/Natural Gas Biogas Firewood Others To tal Farming Regions 1.43 14.37 1.73 2.33 78.13 2.00 100.00 Farming-Pastoral Regions 0.65 2.80 0.65 0.29 87.86 7.76 100.00 Pastoral Regions 2.08 0.38 2.46 0.00 39.13 55.95 100.00 Total 1.30 10.19 1.53 1.60 76.87 8.51 100.00 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66  WANG S. X. ET AL. more dignity. Against the background of economic globalization, the edu- cational level and health condition of laborers in one country or one region determine not only the material capital investment, but also its market competitiveness. In developing countries, poverty can be lessened with the improvement of the basic capacities of entire laborers through income redistribution and investment in basic education and medical services. The econ- omy may grow with the general development of human re- sources. Drinking water and environmental sanitation are re- garded as important components of public health services in rural areas. Their improvement can directly reduce wa- ter-related diseases and trading hours of labor. Moreover, the ecological environment can be protected, the health cognition of local villagers can be effectively converted, and the villag- ers’ participation in public services can be encouraged as at- tributed to the application of the “Trinity Mode.” The im- provement of water and environmental sanitation becomes increasingly meaningful in improving the quality of life, con- verting the lifestyle, and lessening the poverty of the pov- erty-stricken population in western China. Local governments should include the quality of environmental sanitation into the overall plan of economic and social development, and set an agenda particularly for this issue. The formulation of such poli- cies can guarantee the healthy and sustainable development of the economy and the society. REFERENCES Bennett, L., & Gajurel, K. (2007). Change, gender, and ethnic dimen- sions of empowerment and social inclusion in rural Nepal (non- member draft). Kathmandu: World Bank, 2007. Chen, L.-Z. (2008). Analysis of the trends of urban poverty and its influence factor during Chinese transition. Studies on China’s Spe- cial Economic Zones, 5, 5-9. Chen, M., Zhang, L.-X., Zai, Y.-L., & Luo, R.-F. (2005). Region dis- tributing of investment in drinking water in rural China. Research of Agricultural Modernization, 5, 340-343. Das Gupta, M. et al. (2009). How can donors help building global pub- lic goods in health? The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4907, 2009. Data sources: The web portals of the government of A Ba prefecture. URL (last checked 21 June 2009). www.abazhou.gov.cn Fenwick, M., Subedi, S. P., & Hutton, G. (2007). A cost-benefit analy- sis of national and regional integrated biogas and sanitation pro- grams in sub-Saharan Af r ica. Winrock International. Hu, A.-G., Tong, X.-G., & Zhu, D.-D. (2005). The measurement of four classes of poverty: A case study on the poverty relief in Qinghai province (1978-2007). H u n a n S o c ia l Sciences, 5, 45-52. Hutton, G., & Bartram, J. (2007). Global cost-benefit analysis of water supply and sanitation interventions. Journal of Water and Health, 5, 481-502. Li, B., Li, X.-Y., & Zuo, T. (2004). Research and practice of livelihood approach in rural development. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics, 4, 1-6. Li, X.-Y., Dong, Q., Rao, X.-L., & Zhao, L.-X. (2007). The analytical method of peasants’ vulnerabilities and its localization, Chinese Ru- ral Economy, 4. Li, X.-Y., Li, Z. et al. (2005). The development and verification of participatory povert y index. Chinese Rural Economy, 5, 39-46. National Center for Rural Water Supply Technical Guidance (28 March 2006). Safe drinking water and sanitation for the rural poor final re- port. Metcalf & Eddy Ltd. National Center for Rural Water Supply Technical Guidance (28 March 2006). Safe drinking water and sanitation for the rural poor final re- port. Metcalf & Eddy Ltd., ES- p.1 Office of Rural Water Supply and Environmental Sanitation, the Minis- try of Water Resources (1995). Cooperative project of water supply and environmental sanitation of China/UNICEF. The Special Issue in Memory of the 50th Anniversary of the Foundation of the United Na- tions, 47-49. Paul, R., Kathy, H., Paul, P., & Cameron, J. J. ( 2 009). An assessment of the costs and benefits of interventions aimed at improving rural community water supplies in developed countries. Science of the To- tal Environment, 407, 3081-3085. Peter, H. (2008). Poverty reduction strategies: Opportunities and threats for sustainable rural water services in sub-saharan Africa. New York: SAGE Publications Ruth, A., & Nina, H. (2005). Measuring empowerment in practice: Structuring analysis and framing indicators. Policy Research Work- ing Paper No. 3510 of the World Bank, 2005. The Survey Team of National Conditions (2009). Vulnerability and poverty: Empirical analysis of village LI in Jiangsu province. Mod- ern Economic Research, 7, 44-47. Yunus, & Bao, X.-J. (2008). Social business and the future of capi- talism: Creating a world without poverty. Beijing: China Citic Press, 2008. Zhu, L. (2004). The relationship between public service supply and the lessening of poverty at in grass-root units in Tibetan agricultural and pastoral areas. Management World, 4, 41-50. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67 |