Chinese Studies 2013. Vol.2, No.1, 1-7 Published Online February 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/chnstd) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2013.21001 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 1 Key Dimensions and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Individualism-Collectivism Scale Huang Renzhi1, Yao Shuqiao2*, John R. Z. Abela3, Fallyn Leibovitch3, Liu Mingfan4 1Teaching Science Department, Hunan First Normal University, Changsha, China 2Medical Psychological Research Center, Central South University, Second Xiangya Hospital, Changsha, China 3Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Canada 4Psychology Department, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China Email: *Shuqiaoyao@163.com Received November 12th, 2012; revised December 13th, 2012; accepted December 20th, 2012 A Chinese version of the Individualism-Collectivism Scale (ICS) to assess cultural dimensions was de- veloped and its psychometric properties were evaluated. The English version of the ICS was translated and back translated prior to its administration to 1760 participants who were divided into 5 age groups. Results indicated that the ICS-C exhibited moderate to high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.64 to 0.83. The ICS-C also exhibited strong test-retest reliability with ICCs from 0.45 to 0.80. Confirmatory factor Analyses found the four-factor model was the best fit of the data across gender and age, thus supporting the multi-dimensional perspective of horizontal and vertical indi- vidualism and collectivism. Furthermore, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed a sig- nificant main effect of age and gender. A gradual increase is present in subjective perception of societal emphasis on the cultural dimensions across five age groups, except age groups of 14 - 15 and 16 - 17 in vertical individualism. With respect to gender effect, female students showed a higher perception of the vertical collectivism than male students (p < 0.05). Thus, the results revealed that sufficient support for the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of ICS. Keywords: Individualism; Collectivism; Culture; Chinese Students Introduction Culture is a concept that is widely used but difficult to define. Researchers have accounted for behavioral disparities amongst cultures by conceptualizing such differences in terms of dimen- sions which act as parameters (Aaron & Anat, 2006; Voronov & Singer, 2002; Triandis, 1996). Individualism and collectiv- ism are often considered two of the most prominent examples of such dimensions (Triandis, 2001). Whereas collectivism is characterized by communal goals, interdependence, social norms and relationships, individualism emphasizes personal goals, independence, and autonomy (Triandis, 1996, 2001). Individualists view the self as autonomous from one’s in-group, and personal attitudes and perceived benefits shape the motiv- tion for individualist action (Triandis, 2001). In contrast, col- lectivists view the self as a part of one’s in-group, and collec- tive beliefs and obligations shape behavior (Triandis, 2001). Past research examining the operationalization of individual- ism and collectivism has evolved in three distinct phases. First, Hofstede, in 1984, proposed a uni-dimensional approach whereby individualism and collectivism fell at opposite ends of the same continuum (Charles, 2010; Gouveia, Clemente, & Espinosa, 2003). Individualism and collectivism were charac- terized as a single, bipolar construct and thus, endorsing indi- vidualistic tendencies necessarily required rejecting collecti- vistic ideals (Duan, Wei, & Wang, 2008; Freeman & Bordia, 2001). However, as many researchers believed this perspective to be an oversimplification of a more complex phenomenon, Kâgitçibasi, in 1987, proposed a bi-dimensional approach. In doing so, individualism and collectivism were operationalized dichotomously and were considered separate unipolar con- structs (Freeman & Bordia, 2001). More specifically, collectiv- ism emphasized interpreting the self as an extension of one’s in group, and choosing in-group goals over personal goals. In contrast, individualism interpreted the self as distinct from one’s in-group, and focused on personally satisfying goals over in-group goals. The fundamental difference between the two perspectives is that while uni-dimensionality inherently requires a given culture to be classified as either individualistic or col- lectivistic, bi-dimensionality accepts the possibility of the si- multaneous existence of individualistic and collectivistic ten- dencies in a single context (Fauziah & Kamarnzaman, 2010; Freeman & Bordia, 2001). Last, researchers proposed a multi- dimensional approach in which horizontal and vertical dimen- sions were added as subdivisions of individualism and collec- tivism (Singelis, Triandis, & Gelfand, 1995; Triandis, 1996; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). While horizontality refers to an inherent focus on egalitarianism, verticality stresses the princi- ples of authority, power distance and hierarchy (Chiou, 2001; Triandis, 1996, 2001). The inclusion of horizontality and verti- cality accounts for the potential overlap between individualistic and collectivistic tendencies within a single culture expands the classifications to include: 1) horizontal individualism; 2) verti- *Corresponding author.  HUANG R. Z. ET AL. cal individualism; 3) horizontal collectivism; and 4) vertical collectivism (Gouveia, Clemente, & Espinosa, 2003; Triandis, 1996, 2001; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Whereas horizontal individualism refers to the addition of universalistic values to individualism (Triandis, 1996) and denotes independence in terms of the freedom to be unique, vertical individualism, which is the addition of achievement orientations to individual- ism (Triandis, 1996), emphasizes such independence and in addition, places a premium on status and superiority relating to the in-group as well as surrounding out-groups. In contrast, Triandis (1996) defines horizontal collectivism as the inclusion of benevolent ideologies to collectivistic tendencies and vertical collectivism represents the addition of power to collectivism (Triandis, 1996). More specifically, Oppenheimer (2004) sug- gests that horizontal collectivists identify the self as a function of their in-groups and stress equality amongst members. In contrast, vertical collectivists emphasize the authoritarian structure of their in-group, often to the point of self-sacrifice and competition with out-groups (Oppenheimer, 2004; Triandis, 2001). Therefore, the multidimensional model is considered superior to the uni-dimensional and bi-dimensional models, as it is able to completely encompass constructs as complex as culture, individualism and collectivism. The Individualism & Collectivism Scale (ICS) is one of the primary instruments used to assess the multi-dimensional components of individualism and collectivism. Previous re- search examining the reliability and validity of the ICS supports the use of this scale cross-culturally and across ages (e.g. Op- penheimer, 2004; Gouveia, Clemente, & Espinosa, 2003; Choiu, 2001). Across studies, the ICS has been found to possess mod- erate to strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.63 to 0.89) (Anthony, Rosselli, & Caparyan, 2003; Choiu, 2001; Gouveia, Clemente, & Espinosa, 2003; Oppen- heimer, 2004; Singelis et al., 1995; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Moreover, the ICS has demonstrated strong construct validity, whereby distinct patterns of associations were found between each of the four dimensions of individualism and collectivism, and sociopolitical attitudes related to equality and inequality (Strunk & Chang, 1999). The ICS has also demonstrated gener- ally strong convergent and divergent validity (Triandis & Gel- fand, 1998). More specifically, horizontal and vertical indi- vidualism as well as horizontal and vertical collectivism were negatively correlated. In addition, individuals who exhibited vertical individualistic tendencies endorsed constructs including competition and hedonism; however, individuals who empha- sized horizontal individualism exhibited higher levels of self-reliance without competition (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Furthermore, whereas vertical collectivists scored highly on measures of sociability and family integrity and low on emo- tional distance from one’s in-group, horizontal collectivists stressed interdependence and sociability but did not endorse family integrity (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). From a developmental point of view, the subjective percep- tions of culture dimensions were influenced and formed by the individual’s early living environments and parenting received from it (Oppenheimer, 2004). More specifically, When children enter a competitive environment (i.e. an individual environ- ment), for example, secondary schools or university, from the protective environment of a family (i.e. a collective environ- ment), it is expected that they would perceive the shift of em- phasis from collectivism to individualism and make the corre- sponding adaptation. Therefore, the initial influence of the col- lectivism at the age of 14 would gradually decrease and be replaced by the later perceived strong emphasis on individual- ism. Similarly a shift from horizontality (i.e., equality) to verti- cality (i.e., power distance based on competition) would have taken place. Some researchers (Oppenheimer & Hitteling, 2004) had observed that the parenting way of a family moved from authoritarian with young children to authoritative, and finally to permissive with older children across ages. As far as gender effect is concerned, Oppenheimer (2004) has demonstrated that males show a significantly stronger and rather stable perception of societal emphasis on individualism than females (p < 0.05). In his study examining vertical and horizontal individualism and collectivism in Netherlands, for vertical individualism females indicated a significant increase in their subjective perceptions while this was not the same case for males. Only after the age of 22, males scored lower than females on the subscale of vertical individualism. For subjec- tive perceptions of horizontal individualism again a significant increase is present for females across age, while all ages males perceive a significant higher societal emphasis on horizontal individualism than females. On that subscales of vertical and horizontal collectivism scores did not reveal any significant differences between male and female participants. The objectives of the study were four-fold. First, we aimed to develop a Chinese version of the ICS (ICS-C). Second, we examined the reliability of the ICS-C, specifically internal con- sistency and test-retest reliability. Third, we conducted confir- matory factor analyses in order to determine whether the four- factor model was the best fit of the data. Last, we examined age and gender-related differences in individualism and collectiv- ism as assessed by the ICS-C. Methods Participants Participants were recruited from one university (Hunan Normal University) and two high schools in Hunan Province, China. The final sample consisted of 1760 students (51.4% female and 48.6% male) ranging in age from 14 to 23 years (total = 17.69, SDtotal = 2.10; males = 17.42, SDmales = 1.08; females x = 17.83, SDfemales = 1.04). The sample was 91% Han and 9% ethnic minority. With regard to family composition, 71% of children lived with their nuclear families, 22.3% with their extended families, and 6.7% in single parent homes. Procedure Prior to the initial assessment, letters of informed consent were sent home with students detailing the aim of the present study. More specifically, the informed consent detailed the project aims which included developing a Chinese translation of the ICS and examining the psychometric properties of the questionnaire in a sample of Chinese students. It is important to note that students were only permitted to participate if the pro- ject coordinator received a signed informed consent form. Moreover, if the participant was under the age of 18, a parent was also required to sign the informed consent form. During the initial assessment, students completed the Chinese version of the ICS (ICS-C) with a demographics form. One month later, the ICS-C was re-administered to a subset of the original sam- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 2  HUANG R. Z. ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 3 ple (n = 227) in order to examine test-retest reliability. Measures The ICS-C was developed using the back-translation method. First, the original version was translated into Chinese by one bilingual translator from the psychology department at Central South University (Changsha, Hunan). Next, the Chinese ver- sion was back-translated into English by another bilingual translator from the psychology department at McGill University. Finally, the original version of the ICS was compared with the back-translation. If discrepancies arose in the back-translation, translators worked cooperatively to make corrections to the Chinese version. The Individualism and Collectivism Scale (ICS; Singelis et al., 1995) The ICS is a 32-item self-report measure designed to assess the following dimensions of culture: horizontal individualism, vertical individualism, horizontal collectivism, and vertical collectivism. The scale can be divided in order to separately assess a participant’s endorsement of individualism and collec- tivism, as well as further sub-divided in order to include the sub-dimensions of horizontality and verticality. The first set of sixteen questions represent individualism, whereby the first eight items relate to horizontality and the next eight items relate to verticality. The second set of sixteen questions represents collectivism, whereby the first eight items relate to horizon- tality and the next eight items relate to verticality. Examples of questions include, “I often do my own thing (horizontal indi- vidualism)”, “It annoys me when other people perform better than I do (vertical individualism)”, “The well-being of my co-workers is important to me (horizontal collectivism)”, and “I would sacrifice an activity that I enjoy very much if my family did not approve of it (vertical collectivism)”. Participants were provided with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from totally agree (1) to totally disagree (7), whereby lower scores on a given subscale reflect the participant’s endorsement of that subscale. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the sub- scale of the horizontal individualism, vertical individualism, horizontal collectivism and vertical collectivism were 0.69, 0.64, 0.83 and 0.88 (p < 0.01), respectively, indicating strong internal consistency. The ICS-C also exhibited strong test-retest reliability with mean ICCs from 0.45 to 0.80 for the sample (n = 227) at one month’s interval, p < 0.01. Psychometri c E va l uation Analyses were conducted using SPSS 12.0 and AMOS 5.0 software. In order to evaluate the internal consistency of the ICS-C, we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Pear- son’s correlations were used to analyze the inter-correlations across subscales and the intra-class correlation coefficients were utilized as test-retest reliability. When examining the four- factor model of the Chinese culture, we utilized maximum- likelihood confirmatory factor analyses. one- and two-way analyses of variance (MANOVA) were conducted to evaluate the gender-, age-related effects and interaction of the two inde- pendent variables. Given the large numbers of participants, an alpha of 0.01 was used. The related data on descriptive statistics, means and deviations across gender and reliability of the ICS-C are displayed in Tables 1-3. Results Confirmatory Fact or Analysis As the ICS-C was translated from the English version, we expected to have 1) four first-order factors and 2) one second- order factor. Maximum likelihood confirmatory analysis (CFA) was performed to determine how well the original four-factor model fit the Chinese data. One and two factor models were also examined. To evaluate model fit, four indices were ana- lyzed (values in parentheses denote goodness-of-fit standards): 1) the comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90); 2) the Tucker-Lewis non-normed fit index (NNFI > 0.90); 3) the root means square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.08); and 4) the goodness- of-fit index (GFI > 0.90) (Bollen, 1989; Browne & Cudeck, 1993). These fit indices are presented in Table 4. The chi- square statistic was significant for all three models (p < 0.001), indicating the sensitivity of this statistic to sample size. Degrees of freedom of the three models were 20 (one-factor model), 19 (two-factor model), and 14 (four-factor model). The chi-square of freedom ratios were 36.86 (one-factor model), 29.96 (two- factor model) and 12.54 (four-factor model). While none of the ratios were satisfactory, the four-factor model yielded the best ratio, compared to the one and two-factor models. With respect to GFI, the indices of the three models all exceeded 0.90, and were thus considered satisfactory. Moreover, the GFI of the four-factor model (0.98) was especially higher than those of the other two models. When NNFI and CFI were included in the analysis, the four-factor model (NNFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.93) was superior to the other two models, followed by the two-factor model (NNFI = 0.75, CFI = 0.75), and then the one-factor (NNFI = 0.67, CFI = 0.67). RMSEA values were 0.14 (one- factor model), 0.13 (two-factor model), and 0.08 (four-factor model). As an acceptable RMSEA value must be less than or equal to 0.08, the one and two-factor models did not fit, thus Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the ICS-C by gender. Total (n = 1760) Male (n = 855) Female (n = 905) Subscale Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD η2 Horizontal individualism 5.09 0.74 5.14 0.75 5.04 0.73 0.14 Vertical individualism 4.43 0.79 4.43 0.79 4.42 0.79 0.01 Horizontal collectivism 5.40 0.78 5.41 0.79 5.38 0.77 0.04 Vertical collectivism 4.88 0.72 4.80 0.74 4.96 0.70 0.24 Note: ICS-C = Individualism & Collectivism Scale: Chinese Version. η2 indicates effect size. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.  HUANG R. Z. ET AL. Table 2. Means and standard deviations of five age groups in the ICS-C (N = 1760). Horizontal individualism Vertical individualism Horizontal collectivism Vertical collectivism Age groups Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD 14 - 15 4.94 0.75 4.32 0.84 5.33 0.81 4.82 0.72 16 - 17 5.07 0.77 4.43 0.82 5.37 0.84 4.82 0.77 18 - 19 5.12 0.64 4.42 0.71 5.40 0.66 4.92 0.67 20 - 21 5.15 0.74 4.48 0.75 5.44 0.69 4.98 0.65 22 - 23 5.30 0.78 4.49 0.89 5.68 0.71 5.07 0.65 Note: ICS-C = Individualism and Collectivism Scale: Chinese Version. Table 3. Reliability of the ICS-C (N = 1760). Variable Subscale Sum of squares df Mean squares F p Horizontal individualism 9.04 4 2.26 4.158** 0.002 Vertical individualism 3.839 4 0.960 1.534 0.190 Horizontal collectivism 7.481 4 1.870 3.101* 0.015 Age group Vertical collectivism 11.646 4 2.911 5.702*** 0.000 Horizontal individualism 3.479 1 3.479 6.401* 0.011 Vertical individualism 5.684E−02 1 5.684E−02 0.091 0.763 Horizontal collectivism 0.116 1 0.116 0.192 0.662 Gender Vertical collectivism 12.145 1 12.145 23.786*** 0.000 Note. ICS-C = Individualism and Collectivism Scale: Chinese Version. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Table 4. Model fit statistics for the ICS-C. Model χ2 df GFI NNFI CFI RMSEA (CI for 90%) One-factor model 737.28 20 0.90 0.67 0.67 0.14 (0.13 - 0.15) Male 287.85 20 0.92 0.74 0.75 0.13 (0.11 - 0.14) Female 471.88 20 0.88 0.60 0.61 0.16 (0.15 - 0.17) Two-factor model 569.15 19 0.92 0.75 0.75 0.13 (0.12 - 0.14) Male 230.16 19 0.93 0.79 0.80 0.11 (0.10 - 0.13) Female 359.82 19 0.90 0.69 0.70 0.14 (0.13 - 0.15) Four-factor model 175.60 14 0.98 0.92 0.93 0.08 (0.07 - 0.09) Male 94.54 14 0.97 0.91 0.92 0.08 (0.07 - 0.10) Female 83.98 14 0.98 0.93 0.94 0.08 (0.06 - 0.09) Age group 1 (14 - 15) 41.12 14 0.97 0.90 0.92 0.08 (0.06 - 0.10) Age group 2 (16 - 17) 43.59 14 0.96 0.92 0.93 0.08 (0.06 - 0.09) Age group 3 (18 - 19) 48.57 14 0.98 0.91 0.92 0.08 (0.07 - 0.10) Age group 4 (20 - 21) 44.50 14 0.96 0.92 0.91 0.08 (0.07 - 0.09) Age group 5 (22 - 23) 46.95 14 0.95 0.92 0.91 0.08 (0.07 - 0.09) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 4  HUANG R. Z. ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 5 indicating that the four-factor model was again superior. Fur- thermore, the analysis yielded a reasonable fit (x2(14) = 175.60, p ≤ 0.00, GFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.93) between the four-factor model and the data. The four-factor model was also applicable to both gender groups, as well as the five age groups, with fairly desirable fit indices, as seen in Table 4. ICS-C Subscale Correlations by Gender The two and four-factor model correlation coefficients by gender are displayed in Table 5. The correlation matrices for girls and boys were generally comparable. In the two-factor model, the correlations between individualism and collectivism were 0.31 (male) and 0.25 (female), respectively (p < 0.05). In the four-factor model, the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.07 to 0.45 (male) and 0.01 to 0.31 (female). All of the corre- lation coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.01), with the exception of the correlation between vertical individualism and horizontal collectivism (p > 0.05). Age Differences A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was per- formed on the subscale score of ICS-C as dependent variables and age groups as the independent variable to examine the ex- tent to which the scale captured the age difference among the participants. The results indicated that there was an overall significant effect of age (Wilks’lambda = 0.978, df = 16, F = 2.471, p < 0.01) for the four subscales. Univariate tests further indicated that there were significant age differences in partici- pants’ ratings on all four subscales: Horizontal Individualism (F(4, 1753) = 2.615, p < 0.05), Vertical Individualism (F(4, 1753) = 2.716, p < 0.05). Horizontal Collectivism (F(4, 1753 = 4.681, p < 0.001)) and Vertical Collectivism (F(4, 1753) = 3.058, p < 0.05). Post hoc tests using Scheffe’s criteria revealed that for the Horizontal Collectivism subscales, the mean scores of the five age groups were higher than the mean scores of the other three subscales. For the main effect of age, age group 1 was found to rate the horizontal individualism lower signifi- cantly than both age group 4 (mean difference = 0.2093, p < 0.05) and age group 5 (mean difference = 0.3633, p < 0.05), while age group 2 - 5 did not differ from each other. With re- gard to vertical individualism, results demonstrated that the five Table 5. Factor inter-correlations for the two and four-factor models of the ICS-C. Two-factor model 1 2 1. Individualism - 0.31* 2. Collectivism 0.25* - Four-factor model 1 2 3 4 1. Horizontal individualism - 0.22** 0.34** 0.24** 2. Vertical individualism 0.21** - 0.07 0.18** 3. Horizontal collectivism 0.31** 0.01 - 0.45** 4. Vertical collectivism 0.17** 0.20** 0.40** - Note: ICS-C = Individualism and Collectivism Scale: Chinese Version. Correla- tions that appear above the diagonal denote males, and those below the diagonal denote females. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. age groups also did not differ from each other. In the subscale of horizontal collectivism, only age group 5 scored higher than age group 1 (mean difference = 0.3561, p < 0.05). Moreover, the participants of age group 4 tended to rate the scores higher on the vertical collectivism subscale compared with the par- ticipants of age group 1 (mean difference = 0.1519, p < 0.05). These results indicated that he scale was capturing age effects among the participants. Gender Differences To examine age difference between those male and female participants with respect to their subjective perception on cul- tural dimensions, a one-way MANOVA was performed on the participants’ four subscales scores as dependent variables and their gender as the independent variable. The mean and stan- dard deviations of the sample for each subscales are presented in Table 4. The results showed that there was an overall effect of gender (Wilks’lambda = 0.977, df = 4, F = 10.149, p < 0.001) for the ICS-C. Univariatge tests indicated significant effects for one of the four subscales, the vertical collectivism subscale (F(1, 1756) = 1.117, p < 0.05), with those female students showing a higher perception of the vertical collectivism. Those male and female participants did not differ in their ratings on the other three subscales (p > 0.05). Additional Tests for the Robustness of the ICS-C To seek further evidence for the robustness of this scale in capturing age effects, additional MANOVAs were run across the demographic variable of gender, therefore, separate two- way MANOVAs were run for age group and gender. Wilk’s criteria was performed with age group and gender serving as the independent variables and the four subscales serving as the dependent variables. Except for the significant main effect that found for age group and gender, no interaction was found dur- ing this analysis. In summary, the findings revealed that the 32-item ICS-C is a reliable measure that captures the anticipated age differences. Further analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the demographic variables (gender and age) and par- ticipants’ subscale scores. Results indicated that main age and gender-related effects did exist while the interaction was not detected. Discussion The results of the current study indicate that the ICS-C is a reliable measure of individualism and collectivism. More spe- cifically, the alpha coefficients for each of the four subscales were acceptable, indicating moderate to strong internal consis- tency. Moreover, the intraclass correlation coefficients for each of the four subscales ranged from satisfactory to excellent, in- dicating moderate to strong test-retest reliability. This suggests that individualism and collectivism, as measured by the ICS-C, are relatively stable constructs. The results of this study also indicate that the ICS-C exhibits high levels of validity. All correlations of the total scales were statistically significant, and with the exception of vertical indi- vidualism to horizontal collectivism, all correlations among the four subscales were significant. The correlation between hori- zontal and vertical individualism were small, but significant,  HUANG R. Z. ET AL. and the correlation between vertical and horizontal collectivism was moderate. This indicates that individualism, collectivism and their horizontal and vertical sub-dimensions are independ- ent yet related constructs. The case of low correlation of verti- cal individualism to horizontal collectivism has also been found in a cross-cultural study conducted by Chiou and colleagues (2001). As predicted, the results of the current study revealed four first-order factors and one second-order factor. Maximum like- lihood confirmatory factor analysis supported the four-factor model as superior to the one and two-factor models. While the one and two-factor models were satisfactory in terms of fit with the Chinese data, the four-factor was the best fit. The four- factor model was also found to apply to all groups, yielding fairly desirable fit indices for each of the five age groups, as well as both gender groups. Furthermore, although none of the chi-square ratios were significant, the ratio of the four-factor model was better, compared to the ratios of the one and two-factor models. The RMSEA values are also noteworthy, as the value of the four-factor model was significant, whereas the values of the one and two-factor models were not. Therefore, the results of the current study indicate that the four-factor model is superior to the one and two-factor models. Moreover, the ICS-C subscale correlations in the four factor model were superior to those of the two-factor model. All of the correla- tions were significant, with the exception of vertical individual- ism and horizontal collectivism. Thus, the results of the current study support the four factors of individualism and collectiv- ism. The results provide support for the viewpoint that the ICS-C was capturing age effects among the student participants. Whereas a gradual increase is present in subjective perception of societal emphasis on vertical and horizontal individualism and collectivism across five age groups, only the participants with age of 14 - 15 did the subjective perception of vertical individualism scored a little lower than those with age of 16 - 17. For a developing participant, culture is not a stable and ordered entity with fixed characteristics. Our findings suggest that during adolescence, and also during adulthood, participants continue to construe their understanding of culture. The subjec- tive perception of culture is a dynamic process that is informed by the interaction between the environments in which individu- als directly function and their level emotional and cognitive development such as co-construction (Nachiketa, Sonia, & Jezdimir, 2010; Thao & Gary, 2005; Valsiner, 1998; Valsiner et al., 1997). In Chinese society, the progressive understanding of societal characteristics is most evident for perceived societal emphasis on horizontal collectivism. Or, to put it another way, with in- creasing age, student participants perceive that society puts higher demands on interdependence and egalitarian. With re- spect to individualism, our findings also demonstrated that by the age 14, individualism within the Chinese culture is per- ceived and understood to be emphasized which increased from that age on. Neither vertical individualism nor horizontal indi- vidualism were perceived increasingly, which was definitely different from the findings of the Dutch study (Oppenheimer, 2004). In comparison to subjective perceptions of collectivism, the Dutch adolescents and adults became progressively more aware of societal appeals on individualism. This implies that the understanding and interpretation of culture will and never can be identical to any objective characterization of society because individual, subjective variables modify such features. The results of the current study also indicated noteworthy gender differences in the subscales of the ICS-C. Whereas fe- males scored higher than males on the vertical collectivism subscale, males scored higher than females on the three re- maining subscales. However, only the vertical collectivism gender difference was statistically significant. These findings are curious, as they are in contrast with those found in Oppen- heimer’s (2004) American sample. A possible explanation is that this might reflect a difference found in Chinese culture, whereby Chinese girls might emphasize power distance, or endorse a more hierarchical perspective within their in-groups than Chinese boys. Perhaps Chinese girls are more socialized than Chinese boys during their growth. Some researchers (e.g. Chiu, 1999, Kasser & Ryan, 1993; Landis & Koch, 1977; Singelis, 1994; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) have pointed out that China is not just an “other-directed” society whose members are sensitive to the expectations and preferences of others, but a target-specific society whereby there are different expectations of social behavior for different relationships. Thus, the Chinese girls might be ready to sacrifice their personal and individualis- tic goals and needs for the sake of the in-group. Further inves- tigation should be conducted in order to extrapolate the root causes of this difference. The use of self-report measures as the primary more of data collection might be considered a limitation of the current study, which was criticized by psychologists for the shortcoming of not reflecting actual behavior. However, the aim of the current study was to accrue the participants’ subjective perceptions of these cultural dimensions, as opposed to measuring objective behaviors. Therefore, self-report measures were valuable tools in this study. Overall, the results of the current study indicate that the ICS-C is a reliable and valid measure of the constructs of indi- vidualism and collectivism, as well as their sub-dimensions in the mainland of China. With regard to future research, the next logical step would be conducting studies using the ICS-C in a non-student population. Additionally, such studies should be conducted in a number of other regions of China, outside of the Hunan Province. These studies would enable researchers to better evaluate the ICS-C on a broader spectrum within the Chinese culture. REFERENCES Aaron, C., & Anat, A. (2006). The relationship between individualism, collectivism, the perception of justice, demographic characteristics and organizational citizenship behavior. The Service Industries Journal, 8, 889-901. Anthony, K., Rosselli, F., & Caparyan, L. (2003). Truly evil or simply angry: Individualism, collectivism, and attributions for the events of September 11th. Individual Diff er en ce s Res ea rc h, 2 , 147-157. Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Charles, W. E. (2010). The conflict between individualism and collec- tivism in a democracy: Three lectures. Charlottesville, VA: Univer- sity of Virginia, Barbour-Page Foundation, Biblio Life Press. Chiou, J. S. (2001). Horizontal and vertical individualism and collec- tivism among college students in the United States, Taiwan and Ar- gentina. The Journal of Social Psychology, 5, 667-678. doi:10.1080/00224540109600580 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 6  HUANG R. Z. ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 7 Chiu, C.-Y. (1999). Normative expectations of social behavior and concern for members of the collective in Chinese society. The Jour- nal of Psychology, 1, 103-111. Duan, C. M., Wei, M. F., & Wang, L. Z. (2008). The role of individu- alism-collectivism in empathy: An exploratory study. Asian Journal of Counseling, 1, 57-81. Fauziah, N., & Kamarnzaman, J. (2010). Individualism-collectivism and job satisfaction between Malaysia and Australia. International of Educational Managemen, 2, 159-174. Freeman, M. A., & Bordia, P. (2001). Assessing alternative models of individualism and collectivism: A confirmatory factor analysis. European Journal of Personality, 15, 105-121. doi:10.1002/per.398 Gouveia, V. V., Clemente, M., & Espinosa, P. (2003). The horizontal and vertical attributes of individualism and collectivism in a Spanish population. The Journal o f S oc ia l Psychology, 1, 43-63. doi:10.1080/00224540309598430 Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Kagitçibasi, Ç. (1987). Individual and group loyalties: Are they com- patible? In Ç. Kagitçibasi (Ed.), Growth and progress in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 94-103). Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central lie aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 410-422. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410 Landis, J., & Koch, G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159-174. Nachiketa, T., Sonia, N., Marija, M., Lidtja, R., & Jezdimir, Z. (2010). Assertiveness and personality: Cross-cultural difference in Indian and Serbian male students. Psychological Student, 55, 1-9. Oppenheimer, L. (2004). Perception of individualism and collectivism in Dutch society: A developmental approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 4, 336-346. doi:10.1080/01650250444000009 Shrout, P., & Fleiss, J. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bull, 86, 420-428. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interde- pendent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580-591. doi:10.1177/0146167294205014 Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P. S., & Gelfand, M. J. (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and col- lectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 3, 240-275. doi:10.1177/106939719502900302 Strunk, D. R., & Chang, E. C. (1999). Distinguishing between funda- mental dimensions of individualism-collectivism: Relations to socio- political attitudes and beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 665-671. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00258-X Thao N. L., & Gary, D. S. (2005). Individualism, collectivism and delinquency in Asian American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent P s yc hol og y, 4, 681-691. Triandis, H. C. (1996). Cultural syndromes. American Psychologist, 4, 407-415. Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 6, 907-924. Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Soc ial Psychology, 1, 118-128. Valsiner, J. (1998). The guide mind. A sociogenetic approach to per- sonality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Valsiner, J., Branco, A. U., & Melo Dants, C., (1997). Co-construction of human development: Heterogeneity within parental belief orienta- tions. In J. E. Grusec, & L. Kuczynski (Eds.), Parenting and chil- dren’s internalization of va l u es (pp. 283-304). New York: Wiley. Voronov, M., & Singer, J. A. (2002). The myth of individualism-col- lectivism: A critical review. The Journal of Social Psychology, 4, 461-480.

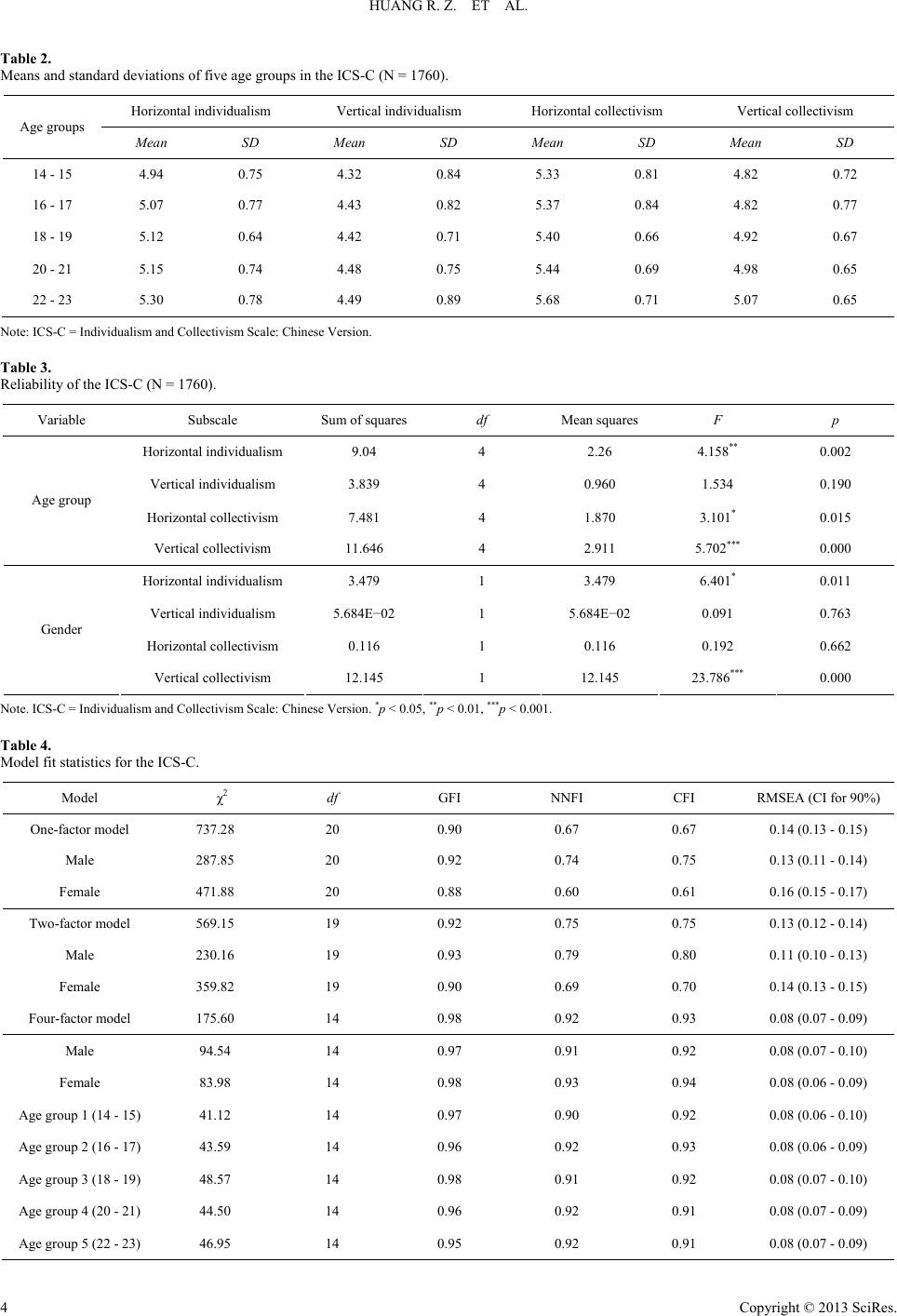

|