Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

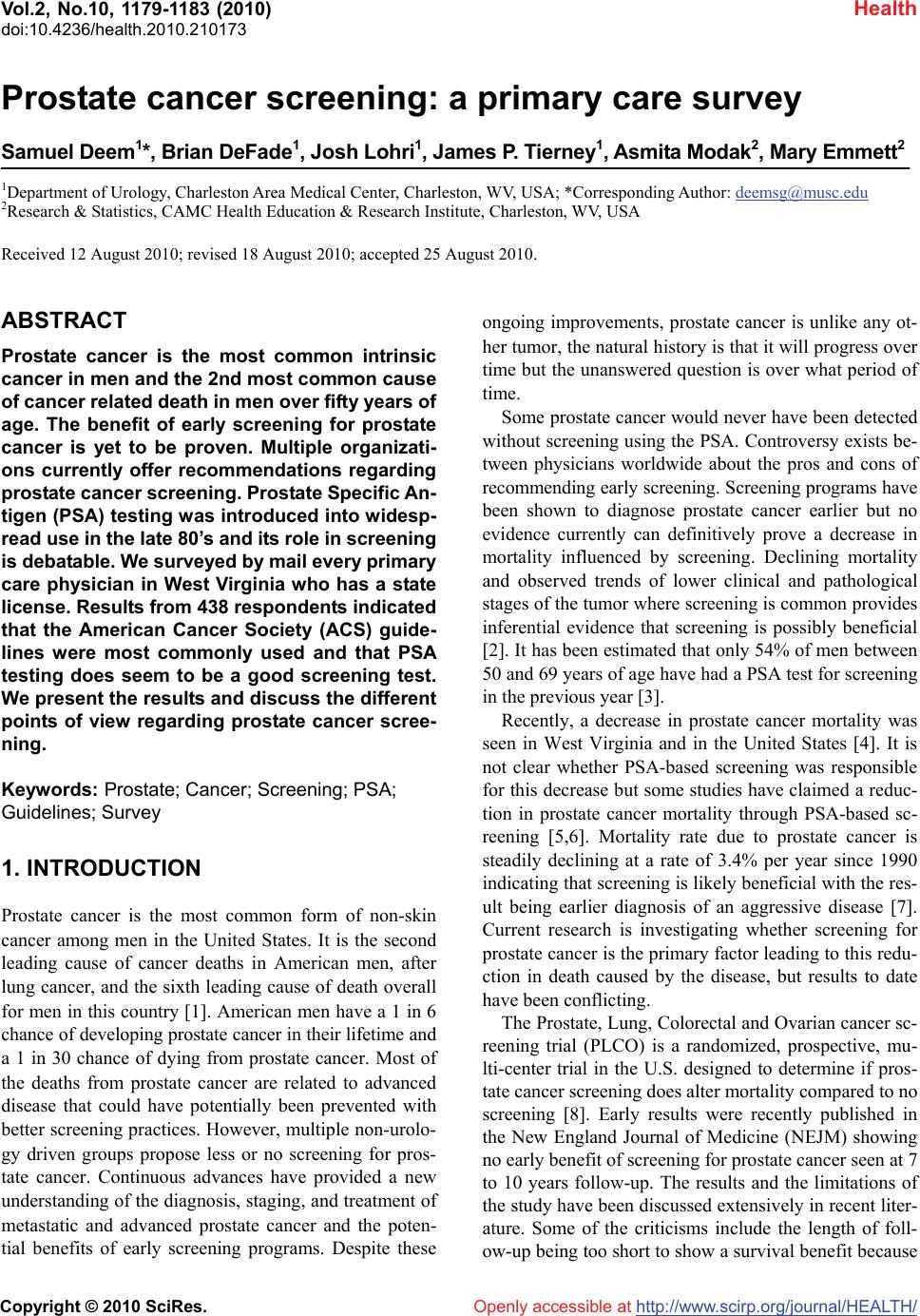

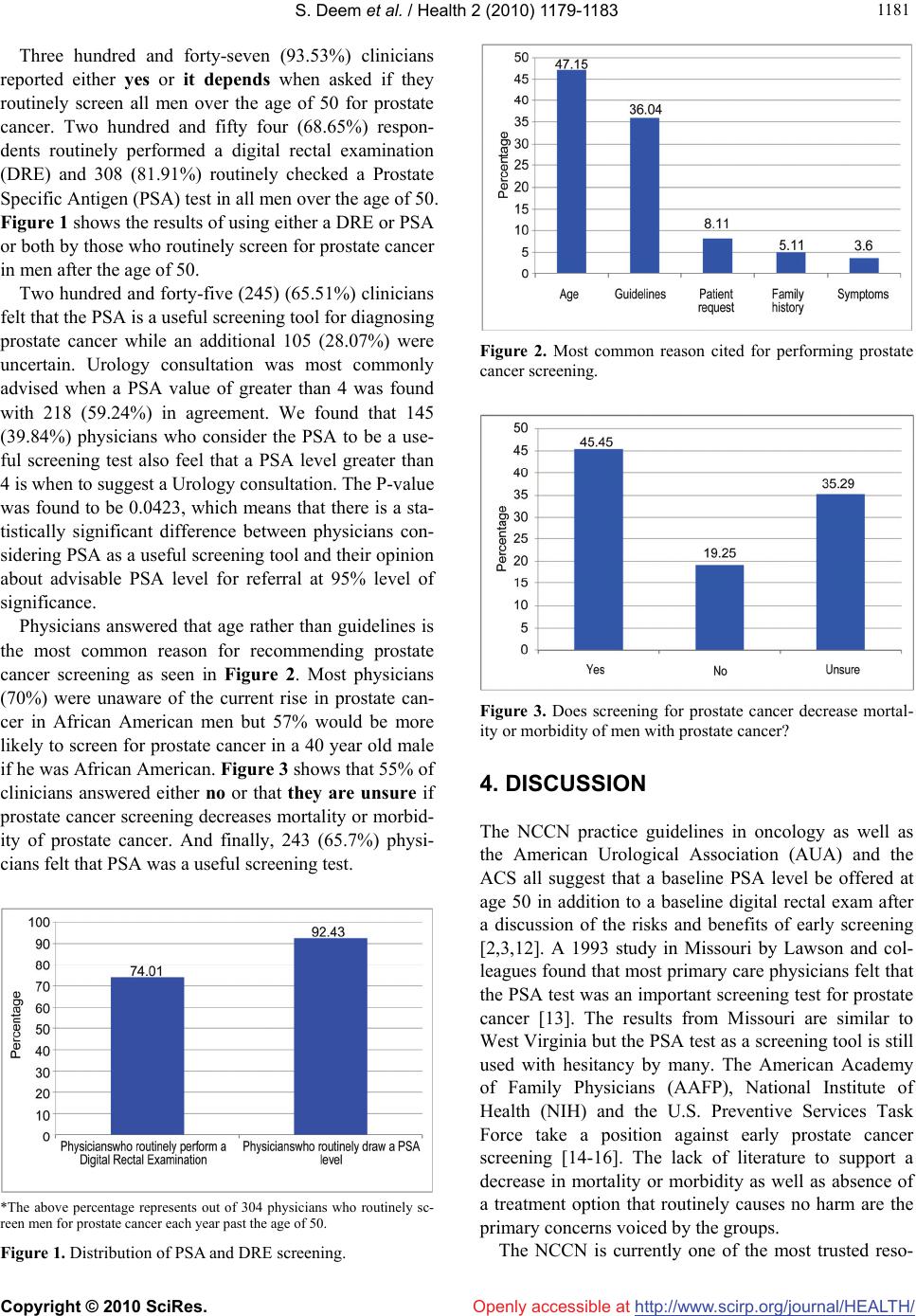

Vol.2, No.10, 1179-1183 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.210173 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Prostate cancer screening: a primary care survey Samuel Deem1*, Brian DeFade1, Josh Lohri1, James P. Tierney1, Asmita Modak2, Mary Emmett2 1Department of Urology, Charleston Area Medical Center, Charleston, WV, USA; *Corresponding Author: deemsg@musc.edu 2Research & Statistics, CAMC Health Education & Research Institute, Charleston, WV, USA Received 12 August 2010; revised 18 August 2010; accepted 25 August 2010. ABSTRACT Prostate cancer is the most common intrinsic cancer in men and the 2nd most common cause of cancer related death in men over fifty years of age. The benefit of early screening for prostate cancer is yet to be proven. Multiple organizati- ons currently offer recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening. Prostate Specific An- tigen (PSA) testing was introduced into widesp- read use in the late 80’s and its role in screening is debatable. We surveyed by mail every primary care physician in West Virginia who has a state license. Results from 438 respondents indicated that the American Cancer Society (ACS) guide- lines were most commonly used and that PSA testing does seem to be a good screening test. We present the results and discuss the different points of view regarding prostate cancer scree- ning. Keywords: Prostate; Cancer; Screening; PSA; Guidelines; Survey 1. INTRODUCTION Prostate cancer is the most common form of non-skin cancer among men in the United States. It is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in American men, after lung cancer, and the sixth leading cause of death overall for men in this country [1]. American men have a 1 in 6 chance of developing prostate cancer in their lifetime and a 1 in 30 chance of dying from prostate cancer. Most of the deaths from prostate cancer are related to advanced disease that could have potentially been prevented with better screening practices. However, multiple non-urolo- gy driven groups propose less or no screening for pros- tate cancer. Continuous advances have provided a new understanding of the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of metastatic and advanced prostate cancer and the poten- tial benefits of early screening programs. Despite these ongoing improvements, prostate cancer is unlike any ot- her tumor, the natural history is that it will progress over time but the unanswered question is over what period of time. Some prostate cancer would never have been detected without screening using the PSA. Controversy exists be- tween physicians worldwide about the pros and cons of recommending early screening. Screening programs have been shown to diagnose prostate cancer earlier but no evidence currently can definitively prove a decrease in mortality influenced by screening. Declining mortality and observed trends of lower clinical and pathological stages of the tumor where screening is common provides inferential evidence that screening is possibly beneficial [2]. It has been estimated that only 54% of men between 50 and 69 years of age have had a PSA test for screening in the previous year [3]. Recently, a decrease in prostate cancer mortality was seen in West Virginia and in the United States [4]. It is not clear whether PSA-based screening was responsible for this decrease but some studies have claimed a reduc- tion in prostate cancer mortality through PSA-based sc- reening [5,6]. Mortality rate due to prostate cancer is steadily declining at a rate of 3.4% per year since 1990 indicating that screening is likely beneficial with the res- ult being earlier diagnosis of an aggressive disease [7]. Current research is investigating whether screening for prostate cancer is the primary factor leading to this redu- ction in death caused by the disease, but results to date have been conflicting. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian cancer sc- reening trial (PLCO) is a randomized, prospective, mu- lti-center trial in the U.S. designed to determine if pros- tate cancer screening does alter mortality compared to no screening [8]. Early results were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) showing no early benefit of screening for prostate cancer seen at 7 to 10 years follow-up. The results and the limitations of the study have been discussed extensively in recent liter- ature. Some of the criticisms include the length of foll- ow-up being too short to show a survival benefit because  S. Deem et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1179-1183 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1180 prostate cancer can be an indolent disease taking several years to become aggressive. The trial included patients in the non-screening arm that were previously screened prior to the trial or were screened during the trial, both of which would include men with a lower risk of develop- ing cancer during the trial. We all await the final results of the trial once long term data has been collected [9]. Results of another trial, the European Randomized Study for Screening of Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), were published in the same issue of NEJM. The authors repo- rted that screening reduced the rate of prostate cancer death by 20 percent but was associated with a higher rate of over-diagnosis. Several criticisms of this study have been discussed and the contrast between the two trials is alarming. Further development of the data is necessary to draw any conclusions from either trial [10]. Another area of research interest includes both patie- nts and health care providers’ knowledge and awareness of prostate cancer screening. These projects will further the efforts to develop and deliver appropriate public hea- lth strategies for prostate cancer, and will improve the sh- aring of screening-related information between providers and their patients [11]. Until further data exists, we must rely on the best evidence available, which currently wo- uld recommend early screening for prostate cancer in a select patient group only after a thorough discussion of the potential risks and benefits of screening with the pa- tient. Educating patients about all options for treatment of prostate cancer including active surveillance may help avoid the unnecessary treatment of some cancers while still screening to find the aggressive types. Our objectives with this study were first to determine the current screening practices of primary care physic- ians in one state (West Virginia) and then to discuss what current best evidence would suggest. 2. METHODS This study was approved by the Institutional Review Bo- ard at Charleston Area Medical Center. We present the data that was collected from a mail survey of all physi- cians identified as primary care practitioners through the West Virginia Board of Medicine and the West Virginia Board of Osteopathy. Questionnaires were mailed out in March of 2008 with a follow-up mailing completed in May of 2008. The questionnaire consisted of thirteen multiple-choice questions using a standardized data col- lection form. The questions focused on the physicians personal practice preferences and their attitudes toward prostate cancer screening and guidelines including the use of PSA and digital rectal examination (DRE) for this screening. Statistical anaylysis was performed by CAMC Health Education and Research Institute, Center for Health Serv- ices and Outcomes Research. Descriptive statistics were used. Chi squared/Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate were used at 95% level of significance for cross tabula- tion analysis after combining different questions. Analy- sis was done using SAS 9.1.3. 3. RESULTS Out of a total of one-thousand five hundred and thirty- six (1536) questionnaires a total of 442 physicians re- sponded to the survey. Of these, 58 had either an incor- rect address or reported that they had retired from gen- eral practice or practiced in a select medical specialty. Four additional responses came in after the data were calculated and therefore are not included in the results. Our results are based on 380 completed questionnaires. The guideline cited as the most used was the Ameri- can Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines with 187 (56.5%) respondents using this in their current practice. Only 9 (2.72%) respondents currently used the National Compr- ehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for pros- tate cancer screening. Table 1 lists each guideline and shows the percentages of respondents who indicated that they used them. This table illustrates the percentage of respondents who feel that PSA is a useful screening tool for prostate cancer and compares this response to which guideline they use. When asked about familiarity with NCCN guidelines in regards to prostate cancer, 157 (42.9%) of the respondents were not at all familiar and 33 (9.02%) did not know about the NCCN guidelines. Only 4 of the 33 physicians who were very familiar with the guidelines actually based their screening on them. Table 1. Distribution of physicians using each guideline and the response to “Is PSA a useful screening test?” based on the guideline used. Is PSA useful Guidelines Undecided No Yes Total American Cancer Society 48 (14.68%) 7 (2.14%) 132 (40.37%) 187 (57.19%) American Urological Association 10 (3.06%) 2 (0.61%) 31 (9.48%) 43 (13.15%) Center for Disease Control 8 (2.45%) 1 (0.31%) 8 (2.45%) 17 (5.20%) National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2 (0.61%) 1 (0.31%) 5 (1.53%) 8 (2.45%) Other/(USPSTF) 26 (7.95%) 13 (3.98%) 33 (10.09%) 72 (22.02%) Total 94 (28.75%) 24 (7.34%) 209 (63.91%) 327 (100.0%)  S. Deem et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1179-1183 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 118 1181 Three hundred and forty-seven (93.53%) clinicians reported either yes or it depends when asked if they routinely screen all men over the age of 50 for prostate cancer. Two hundred and fifty four (68.65%) respon- dents routinely performed a digital rectal examination (DRE) and 308 (81.91%) routinely checked a Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test in all men over the age of 50. Figure 1 shows the results of using either a DRE or PSA or both by those who routinely screen for prostate cancer in men after the age of 50. Two hundred and forty-five (245) (65.51%) clinicians felt that the PSA is a useful screening tool for diagnosing prostate cancer while an additional 105 (28.07%) were uncertain. Urology consultation was most commonly advised when a PSA value of greater than 4 was found with 218 (59.24%) in agreement. We found that 145 (39.84%) physicians who consider the PSA to be a use- ful screening test also feel that a PSA level greater than 4 is when to suggest a Urology consultation. The P-value was found to be 0.0423, which means that there is a sta- tistically significant difference between physicians con- sidering PSA as a useful screening tool and their opinion about advisable PSA level for referral at 95% level of significance. Physicians answered that age rather than guidelines is the most common reason for recommending prostate cancer screening as seen in Figure 2. Most physicians (70%) were unaware of the current rise in prostate can- cer in African American men but 57% would be more likely to screen for prostate cancer in a 40 year old male if he was African American. Figure 3 shows that 55% of clinicians answered either no or that they are unsure if prostate cancer screening decreases mortality or morbid- ity of prostate cancer. And finally, 243 (65.7%) physi- cians felt that PSA was a useful screening test. *The above percentage represents out of 304 physicians who routinely sc- reen men for prostate cancer each year past the age of 50. Figure 1. Distribution of PSA and DRE screening. Figure 2. Most common reason cited for performing prostate cancer screening. Figure 3. Does screening for prostate cancer decrease mortal- ity or morbidity of men with prostate cancer? 4. DISCUSSION The NCCN practice guidelines in oncology as well as the American Urological Association (AUA) and the ACS all suggest that a baseline PSA level be offered at age 50 in addition to a baseline digital rectal exam after a discussion of the risks and benefits of early screening [2,3,12]. A 1993 study in Missouri by Lawson and col- leagues found that most primary care physicians felt that the PSA test was an important screening test for prostate cancer [13]. The results from Missouri are similar to West Virginia but the PSA test as a screening tool is still used with hesitancy by many. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), National Institute of Health (NIH) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force take a position against early prostate cancer screening [14-16]. The lack of literature to support a decrease in mortality or morbidity as well as absence of a treatment option that routinely causes no harm are the primary concerns voiced by the groups. The NCCN is currently one of the most trusted reso-  S. Deem et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1179-1183 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1182 urces available to practitioners for established guidelines regarding screening, diagnosing and treating various typ- es of malignancy. They provide evidence based medic- ine reviews of the current literature and guidelines for multiple cancers. Twenty-one of the most respected ca- ncer centers in the world meet frequently to discuss the literature and establish these guidelines. They are avail- able at no costs to anyone who can access the Internet (http:www.nccn.org) and are reported in the urology literature. The NCCN recommends screening for pros- tate cancer to include annual DRE and PSA in all men after the age of 50 after discussing the risks and benefits of screening with the patient. High risks groups includ- ing African American males and patients with a family history of a first degree relative with prostate cancer should begin screening at age 40. The ACS guidelines are available online and they recommend offering screening similar to the NCCN guidelines in a patient with life expectancy greater than 10 years [2,3]. Performing a DRE prior to checking a PSA level has been proven to be insignificant. If there is no evidence of recent urinary retention or catheterization, acute prostati- tis, prostate needle biopsy, or vigorous therapy that wo- uld include manipulation of the gland (i.e., colonoscopy or anal intercourse) then performing a DRE prior to ch- ecking the PSA level should not affect the results [17]. Patient age and life expectancy, co-morbidities, and his- tory of prostate enlargement or an elevated PSA should all be considered when determining whether or not to obtain urology consultation. When in doubt it is always best to proceed with specialty inclusion in the decision planning. PSA velocity is another method of determining a need for further intervention. Presently a rise in PSA of > 0.75 ng/ml in one year is an indication for prostate biopsy in normal circumstances. The NCCN now advo- cates lowering this threshold to > 0.35 ng/ml in patients with a PSA level < 4(2). The only accepted risk factors for prostate cancer are increased age, African American race, and family histo- ry, which are not modifiable. The American Cancer Soc- iety recommends a diet low in saturated fat and red meat. Selenium and Vitamin E have been reviewed as potential prevention strategies, however, recent literature showed no benefit in prostate cancer prevention [18]. 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (Finasteride and Dutas- teride) have been advocated as a potential chemopreven- tion therapy for prostate cancer. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) randomized men into receiving either Finasteride or placebo and performed biopsy when the PSA rose to a level of 4 or greater or an abnormal di- gital rectal exam was found. Patients were followed for seven years and a 24.8 percent reduction in the preva- lence of prostate cancer was found in the Finasteride arm. However, there was an increase in the number of high risk cancers found in the Finasteride arm [19]. The Re- duction by Dutasteride of prostate Cancer Events (RE- DUCE) trial, showed a 22.8 percent relative reduction in prostate cancer in the Dutasteride arm indicating effecti- veness in chemoprevention of prostate cancer. The AUA and the American Society of Clinical Oncology released guidelines on chemoprevention of prostate cancer rec- ommending a discussion with men who met the criteria on the risks and potential benefits of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors for prevention of prostate cancer [20]. Aside from these recommendations there are no other modifiable risks that have been established in the current literature. This is the basis for why early screening is co- nsidered by most Urology physicians to be such an obv- ious recommendation. We can only hope to diagnose the more aggressive tumors early before they have spread and allow better control and decreased mortality from this peculiar disease. Our goal in supporting prostate cancer screening, as in other types of cancer screening, is to of- fer everyone the opportunity to have their disease diag- nosed before it is problematic. Some limitations of this survey are that it may not be a representative sample of the primary care physician population in the U.S. Only 25% of the surveys were re- turned and some specialty-trained physicians could have returned their results. The length of time since residency training could affect the method of prostate cancer scr- eening to some degree and this was not categorized by the survey. Prostate cancer remains an elusive disease with an un- predictable course causing controversy in screening and treatment recommendations. Screening for prostate can- cer will likely be controversial for many years to come. However, the decline in prostate cancer mortality in the PSA era can not be ignored. Identification of patients with prostate cancer that may benefit from early treatm- ent can only be achieved by following the best evidence we have to date which would support at least some role for early prostate cancer screening. Collaboration amon- gst the various organizations providing guidelines will be necessary to unify the recommendations and standar- dize screening to improve the effectiveness of screening long term. 5. CONCLUSIONS Primary care physicians currently have a broad range of commitment to prostate cancer screening which is in ac- cordance with the lack of quality studies to confirm its efficacy in decreasing mortality and morbidity in the cu- rrent literature. The diversity amongst the various guide- lines and paucity of evidence to support screening cer-  S. Deem et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1179-1183 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 118 1183 tainly makes the task of providing uniform screening rec- ommendations difficult. Universal commitment to prost- ate cancer screening will only be adopted when all guid- eline panels assimilate and the literature can support th- em. But with the lack of quality, long-term, randomized controlled trials to guide the recommendations, we will likely continue with our current individual best practices based solely on practice preferences and individual atti- tudes toward screening. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was supported by the CAMC Foundation, Sarah and Pa- uline Maier Foundation and CAMC Institute, Inc. of Charleston, WV. We would like to thank Suzanne Kemper, MPH for all of her help with this project. REFERENCES [1] U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group (2010) United States cancer statistics: 1999–2006 incidence and mortal- ity web-based report. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, Atlanta. http:www.cdc.gov/ uscs [2] NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (2010) Prostate cancer early detection. http:www.nccn.org [3] Bostwick, D.G., Crawford, E.D., Higano, C.S., Roach, M., Eds. (2005) American cancer society’s complete guide to prostate cancer. American Cancer Society, At- lanta. [4] Fowler, F.J., Bin, L., Collins, M.M., et al. (1998) Pros- tate cancer screening and beliefs about treatment efficacy: a national survey of primary care physicians and urolo- gists. American Journal of Medicine, 104(6), 526-532. [5] Roberts, R.O., Bergstralh, E.J., Katusic, S.K., et al. (1999) Decline in prostate cancer mortality from 1980 to 1997, and an update on incidence trends in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Journal of Urology, 161(2), 529-533. [6] Bartsch, G., Horninger, W., Klocker, H., et al. (2001) Prostate cancer mortality after introduction of pros- tate-specific antigen mass screening in the Federal State of Tyrol, Austria. Urology, 58(3), 417-424. [7] Tarone, R.E., Chu, K.C. and Brawley, O.W. (2000) Im- plications of stage specific survival rates in assessing re- cent declines in prostate cancer mortality rates. Epidemi- ology, 11(2), 167-170. [8] Andriole, G.L., Levin, D.L., Crawford, E.D., et al. (2005) Prostate cancer screening in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: Findings from the initial screening round of a randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 97(6), 433-438. [9] Andriole, G.L., Crawford, E.D. and Grubb, R.L. (2009) Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360(13), 1310-1319. [10] Shroder, F.H., Hugosson, J., Roobol, M.J., et al. (2009) Screening and prostate cancer mortality in a randomized European study. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360(13), 1320-1328. [11] McKnight, J.T., Tietze, P.H., Adcock, B.B., et al. (1996) Screening for prostate cancer: a comparison of urologists and primary care physicians. Southern Medical Journal, 89(9), 885-888. [12] Sirovich, B.E., Schwartz, L.M. and Woloshin, S. (2003) Screening men for prostate and colorectal cancer in the United States, does practice reflect the evidence? Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 1414-1420. [13] Lawson, D.A., Simoes, E.J., Sharp, D., et al. (1998) Prostate cancer screening - A physician survey in Mis- souri. Journal of Community Health, 23(5), 347-358. [14] Hicks, R.J., Hamm, R.M. and Bemben, D.A. (1995) Prostate cancer screening. What family physicians be- lieve is best. Archives of Family Medicine, 4(4), 317-322. [15] Curran, V., Solberg, S., Mathews, M., et al. (2005) Pros- tate cancer screening attitudes and continuing education needs of primary care physicians. Journal of Cancer Education, 20(3), 162-166. [16] Moran, W.P., Cohen, S.J., Preisser, J.S., et al. (2000) Factors influencing use of the prostate-specific antigen screening test in primary care. American Journal of Managed Care, 6(3), 315-324. [17] Stenner, J., Holthaus, K., Mackenzie, S.H., et al. (1998) The effect of ejaculation on prostate-specific antigen in a prostate cancer-screening population. Urology, 51(3), 455-459. [18] Lippman, S.M., Klein, E.A., Goodman, P.J., et al. (2009) Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate can- cer and other cancer – The selenium and vitamin E can- cer prevention trial (SELECT). Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(1), 39-51. [19] Thompson, I.M., Goodman, P.J., Tangen, C.M., et al. (2003) The influence of Finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. The New England Journal of Medi- cine, 349(3), 213-222. [20] Kramer, B.S., Hagerty, K.L., Justman, S., et al. (2009) Use of 5α-Reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer che- moprevention: American society of clinical oncol- ogy/American urological association 2008 clinical prac- tice guideline. Journal of Urology, 181(4), 1642-1657. |