Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

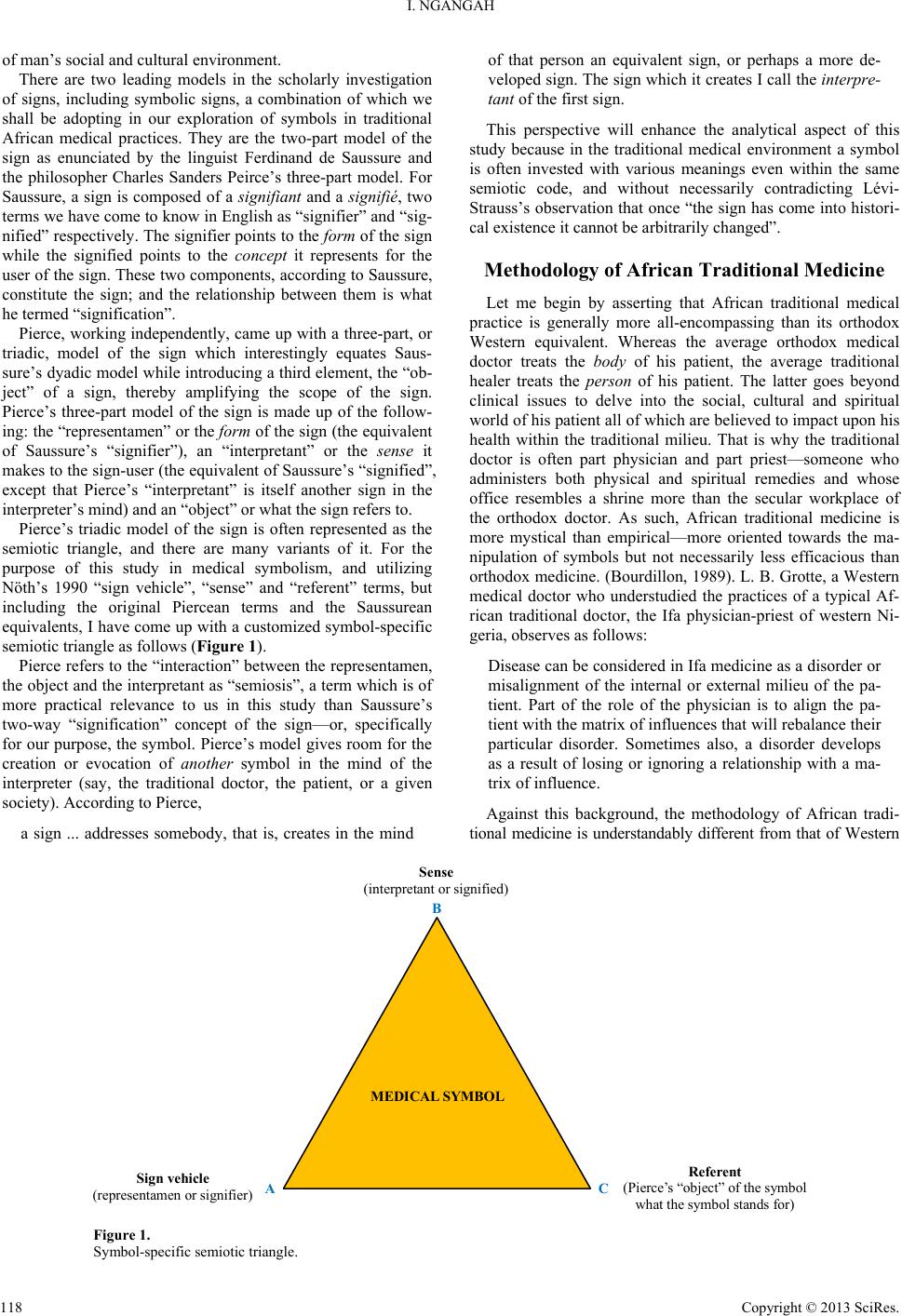

Open Journal of Philosophy 2013. Vol.3, No.1A, 117-121 Published Online February 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2013.31A019 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 117 The Epistemology of Symbols in African Medicine Innocent Ngangah Department of Philosophy, Anambra State University, Igbariam, Nigeria Email: inonganga@ yahoo.com Received December 11th, 2012; revise d J a nu a r y 2013; accepted January 27th, 2013 This article will discuss the epistemology of symbols employed by African traditional medical practitio- ners in treating their patients and the essence of such symbols among traditional communities across the continent. Relying on diverse studies by other researchers and my own investigation conducted among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria, this paper will explore relevant aspects of African traditional medicine as they relate to symbols employed by the practitioners in their effort to offer health care and general well- being to their clients. Keywords: Symbols; African Medicine Introduction Although various studies have been conducted on the subject of symbols and traditional medical practices in African com- munities—and I will be referring to such studies in this dis- course—this article will dwell largely on the semiotic and phe- nomenological implication of African medical symbols. The paper will be divided into three sections. The first sec- tion will dwell on definition and clarification of terms, espe- cially as they touch on the concept and application of symbols in African medicine. Second, the article will present the meth- odology of African traditional medical practices as observed and recorded by ethnographers, philosophers, and social scien- tists who have conducted research in this key area. This section will also underscore the customary nature of traditional medi- cine—which makes the employment of symbols rather impera- tive—by drawing attention to some key differences between traditional and modern medical practices. Third, the article will enumerate some of the key symbols utilized in African tradi- tional medical treatment with a view to extrapolating their symbolic import within the context of a given cognitive system. Although this paper draws its inferences from researches con- ducted across the continent and from my own research in south- eastern Nigeria, I will restrict myself to observed phenomena and will try to avoid sweeping generalisations because of “the diversity of the continent and the attendant whimsical changes in the cultures of the people of Africa” (Isiguzo, 2010). Symbolism Models Employed in This Study Essentially, this paper is exploring the epistemology or knowledge of culture-specific meanings traditional African medical practitioners invest on the herbs, objects, techniques and other tools they employ in their treatment of patients. And when things, including the aforementioned, and as with every spoken or written word, are invested with meaning they become signs. According to Daniel Chandler, We interpret things as signs largely unconsciously by re- lating them to familiar systems of conventions. It is this meaningful use of signs which is at the heart of the con- cerns of semiotics (Chandler, 2012). Such “meaningful use of signs” is also at the heart of this ar- ticle. Because of the nature of this study, we will be concerned specifically with a special group of signs called symbols. N. K. Dzobo thinks that “While signs provide simple information, sym b o ls are used to co mmunicat e complex kno wl edge.” (Dzobo, 1992). But Maduabuchi Dukor has a more elaborate explana- tion: Symbols are cultural realities imbued with cultural mean- ing and any suggestive symbol … is epistemic and the- matic. It is an overt expression of the reality behind any direct act of perception and apprehension, which really possesses scientific connotation outside its normal, obvi- ous or conventional meaning (Dukor, 2006). Symbols in general, in Dukor’s view, refer to that which ex- presses, represents, stands for, reveals, motivates, and makes known another reality. In other words, symbols are tools em- ployed by man for the purpose of understanding the world, himself and his environment, and usually characterized by communicative and cognitive qualities. For the philosopher, Charles Sanders Peirce, a symbol is technically, a sign which refers to the object that it denotes by virtue of a law, usually an association of general ideas, which operates to cause the symbol to be interpreted as referring to that object (Peirce, 1931). He goes further to stress that “The symbol is connected with its object by virtue of the idea of the symbol-using animal, without which no such connection would exist.” (Saussure, 1983). The symbol-using animal Pierce has in mind here is none other than the human being. Symbols are natural to man and had been recognised as such even before the dawn of for- mal language. Man cannot function in his cultural milieu with- out symbols. In fact, the evolution of man cannot be separated from the evolution of symbols. Symbols enable man to under- stand the world around him. They could be seen as a synthesis  I. NGANGAH of man’s social and cultural environment. There are two leading models in the scholarly investigation of signs, including symbolic signs, a combination of which we shall be adopting in our exploration of symbols in traditional African medical practices. They are the two-part model of the sign as enunciated by the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure and the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce’s three-part model. For Saussure, a sign is composed of a signifiant and a signifié, two terms we have come to know in English as “signifier” and “sig- nified” respectively. The signifier points to the form of the sign while the signified points to the concept it represents for the user of the sign. These two components, according to Saussure, constitute the sign; and the relationship between them is what he termed “signification”. Pierce, working independently, came up with a three-part, or triadic, model of the sign which interestingly equates Saus- sure’s dyadic model while introducing a third element, the “ob- ject” of a sign, thereby amplifying the scope of the sign. Pierce’s three-part model of the sign is made up of the follow- ing: the “representamen” or the form of the sign (the equivalent of Saussure’s “signifier”), an “interpretant” or the sense it makes to the sign-user (the equivalent of Saussure’s “signified”, except that Pierce’s “interpretant” is itself another sign in the interpreter’s mind) and an “object” or what the sign refers to. Pierce’s triadic model of the sign is often represented as the semiotic triangle, and there are many variants of it. For the purpose of this study in medical symbolism, and utilizing Nöth’s 1990 “sign vehicle”, “sense” and “referent” terms, but including the original Piercean terms and the Saussurean equivalents, I have come up with a customized symbol-specific semiotic triangle as follows (Figure 1). Pierce refers to the “interaction” between the representamen, the object and the interpretant as “semiosis”, a term which is of more practical relevance to us in this study than Saussure’s two-way “signification” concept of the sign—or, specifically for our purpose, the symbol. Pierce’s model gives room for the creation or evocation of another symbol in the mind of the interpreter (say, the traditional doctor, the patient, or a given society). According to Pierce, a sign ... addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more de- veloped sign. The sign which it creates I call the interpre- tant of the first sign. This perspective will enhance the analytical aspect of this study because in the traditional medical environment a symbol is often invested with various meanings even within the same semiotic code, and without necessarily contradicting Lévi- Strauss’s observation that once “the sign has come into histori- cal existence it cannot be arbitrarily changed”. Methodology of African Traditional Medicine Let me begin by asserting that African traditional medical practice is generally more all-encompassing than its orthodox Western equivalent. Whereas the average orthodox medical doctor treats the body of his patient, the average traditional healer treats the person of his patient. The latter goes beyond clinical issues to delve into the social, cultural and spiritual world of his patient all of which are believed to impact upon his health within the traditional milieu. That is why the traditional doctor is often part physician and part priest—someone who administers both physical and spiritual remedies and whose office resembles a shrine more than the secular workplace of the orthodox doctor. As such, African traditional medicine is more mystical than empirical—more oriented towards the ma- nipulation of symbols but not necessarily less efficacious than orthodox medicine. (Bourdillon, 1989). L. B. Grotte, a Western medical doctor who understudied the practices of a typical Af- rican traditional doctor, the Ifa physician-priest of western Ni- geria, observes as follows: Disease can be considered in Ifa medicine as a disorder or misalignment of the internal or external milieu of the pa- tient. Part of the role of the physician is to align the pa- tient with the matrix of influences that will rebalance their particular disorder. Sometimes also, a disorder develops as a result of losing or ignoring a relationship with a ma- trix of influence. Against this background, the methodology of African tradi- tional medicine is understandably different from that of Western Sense (interpretant or signified) Referent (Pierce’s “object” of the symbol what th e symbol stan ds for) Sign vehicle (representamen or signifier) MEDI CAL SYMBOL C A B Figure 1. Symbol-specific semiotic triangle. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 118  I. NGANGAH medicine. Most of what I noted while enquiring into the tradi- tional medical practices of the typical dibia (native doctor) in various communities of eastern Nigeria coincide with Grotte’s description of the methodology employed by his Ifa counterpart. Grotte’s observation: Utilizing non-familiar forms of diagnosis, such as divina- tion and dream interpretation, in addition to the traditional format of questioning, observation and touching, the Ifa physician may use familiar techniques of dietary therapy, psychotherapy, surgery, and herbal medicine, but may also perform exorcisms, rituals, sacrifices and other pro- cedures which seem more the province of priests than physicians. In other parts of Africa, the priestly or spiritual function is an integral part of the methodology used by traditional healers. The sociologist, M. F. C. Bourdillon, reporting on a similar study among the Shona, observes that, Most traditional healers in Shona society claim to be guided in their art by a helping spirit who takes posses- sion of the healer from time to time, when, according to Shona belief, it is the spirit who speaks through the body of the host ... traditional healers attribute their knowledge of indigenous medicines to the influence of their spirits, who reveal cures in dreams, or guide the healers in the veld to appropriate plants. Other studies, notably those of G. L. Chavunduka, (1988) and V. W Turner’s (1967) among the Ndembu, indicate that the methodology of traditional medicine is similar across Africa. Traditional treatment techniques include, among others, the following: physical and/or spiritual enquiry, observation, touching, dietary prescription, psychotherapy, surgery, herbal medicine, bone-setting (doesn’t necessarily involve surgery), exhuming charms and spiritual objects, extracting confessions from the patient, priestly sacrifices and procedures, traditional vocalizations (mantra), and use of protective charms and amu- lets. Of comparative interest here is a similar study in tradi- tional medical methodology conducted by Alexander K. Smith among the Bon community of India. Symbolism of African Traditional Medicine It is difficult to isolate African traditional medicine from the gamut of other customary practices and beliefs such as ances- tral worship, belief in the cyclical nature of life and the unbro- ken communion between the dead, the living and the unborn—a related feature of which is reincarnation—divination and belief in cosmic laws which govern man’s interaction with both spirits and nature. All of this spurns a series of symbols associated with the gods, with various elements of the observable and invisible world and, interlinked with them, with the wellness of the individual. How the African traditional medical practitioner and his patient evoke and utilize these symbols to redress physical, mental and spiritual maladies will engage our interest in this third section of the study. Although the traditional herbalist is strictly speaking differ- ent from the traditional or ancestral priest, their functions, in practice, so easily overlap that I have combined both roles in this study into what I term the physician-priest. In the tradi- tional setting, the medical symbols employed by the herbalist are drawn from the same traditional belief system superin- tended over by the high priest who serves, like the herbalist, as a healer of first resort and, unlike the ordinary herbalist, as a consultant oracle in personal and communal matters. Both, however, can conduct divinations, hence my decision to merge these two primary actors in traditional healing in the term, phy- sician-priest. The high priest or physician-priest’s role, as Grotte points out below, is that of an interpreter of the visible and invisible causes of the patient’s ma lady. The high priests interpret the factors surrounding a pa- tient’s misalignment by means of their connection to the various oracles of the religion. These reveal themselves through divinatory activity of the priests and an elaborate corpus of oral tradition that interprets the divinatory symbols. The scope of this study will not permit us to investigate this “elaborate corpus of oral tradition” (Mbiti, 1991) alluded to above but we can briefly look at some of the divinatory and other medical symbols employed by the physician-priest. In “Language and Thought in Aquinas: From the Semantics of Being to the Epistemology of Being”, Rosa E. Vargas quotes Aquinas as remarking that “the mode of signification in the terms we impose on things follows on our mode of understand- ing.” She then takes off from there to make a case for the ne- cessity of establishing the “modes of relationship” or “modes of signification” between symbolic vehicles and the sense they make to us. Her observation: Our terms not only signify things in the world, they also signify those things in a certain mode. This mode of sig- nification is grounded in our modes of understanding the things signified by our terms. Thus, for Aquinas the rela- tion between language and world is always mediated by thought. If our modes of signification follow on our modes of understanding, then an analysis of the mode of signification of a term provides an insight into our mode of understanding what is signified by that term. In the light of the above, and utilizing the three “modes of relationship” used by linguists for broad-based categorization of symbols, I have tabulated below some African traditional medical symbols I have identified in the course of this enquiry. The list is by no means exhaustive and the items listed are in- tended to serve as examples. In the notes beneath the Table 1, I have explained how one mode differs from another. What are the implications of these “modes of understanding” for the African traditional medical practitioner (the physi- cian-priest), his patient and the traditional society at large? This will be examined in the rest of this paper. But there is one thing we can immediately deduce from the above table which, I re- peat, is by no means exhaustive: no mode of signification seems to be overwhelmingly dominant within the traditional medical environment. I think this goes to indicate that treating the total man (spirit, soul and body) is of more importance in traditional medicine than paying lopsided attention to the body, like orthodox medicine, at the expense of the spirit and the soul. The symbolic mode of the items listed in the first column of the table points to their conventionality and the regime of spiri- tual and social laws which govern their applicability, meaning and usefulness as instruments for spiritual and medical recon- struction. According to Pierce, symbolic signs such as the ones Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 119  I. NGANGAH Table 1. African traditional medical mode. Symbol (sy mbol ic mode ) Icon (iconic mode) Index (indexical mode) Cowrie Nzu (calabash chalk) Cloth Amulet (or ta li s man) Libation Divination Numbers (in a numerological sense) Earth (land) Kola nut Prophetic utterance Totem/figuring Gong (sound) Colour (red, black, white) Mystical so u nd Herbs (trees/plants) Invocation Animal skin Idol (image) Shrine Cardinal points Animals (owl , cat, dog, etc.) Fire (smoke) Natural events (thunder) Dreams (& interpretation) Sacrifice (animal sacrifice) Ancestral-worship Exorcism Ritual (mode s of ) Medical sym ptoms Note: Explanatory notes to the table: Symbolic mode—in this mode the relationship between the signifier and the signi- fied is essentially arbitrary and conventional in a way which makes it necessary for it to be learnt. The typical examples here are words, numbers, and flags; Iconic mode—in this mode the relationship between the signifier and the signified is based on real or perceived resemblance or imitation. Here the signifier looks, sounds, t astes , etc, like th e signified . Based on “direct percept ion”, typical examples are pictures , signature tunes, metapho r and onomatopoeia; Indexical mode—in this mode the relations hip bet ween the signi fier and the signifi ed is no t arbit rary b ut i s d efined by direct connectio n o cca- sioned by association or a cause-and-effect affiliation . Based on “an act of judgment or inference”, typical examples are medical symptoms, measuring tools, pointers, signals, natural signs, such as thunder, etc. tabulated in this column “direct the attention to their objects by blind compulsion” within the context of this study, Pierce’s “blind compulsion” points to cultural attributes or belief sys- tems imbibed by members of a given community over time. It is this cultural and spiritual sensitivity or faith that the physi- cian-priest rests upon to deliver spiritual and bodily remedy to any afflicted member of the community. This, perhaps, explains why most of the items which fall under this column pertain to the sacred functions (such as using cowries, nzu, numbers, kola nut for divination, and making prophetic pronouncements) tra- ditionally reserved for the priest. Under the iconic mode (Column 2 of the table), we encounter medical symbols governed by “relationship of resemblance”. Three health processes could be evinced here: 1) the physi- cian-priest’s use of all the listed items, except herbs, to appease the ancestors—whom the patient resembles by blood—and to petition the gods, by whom the patient’s spiritual essence is connected to the big invisible God; 2) the use of the herbs’ curative powers to restore the patient’s health—to make him reclaim his health and resemble his wholesome self; 3) the use of relevant colours and mystical sound to attract or repel revi- talizing or destructive forces represented by those colours. Red, for instance, in many African societies, symbolises life and is utilized as such. It is important to note that aside from their physical proper- ties, the symbolic properties of herbs are also taking into ac- count in the physician-priest’s choice of herbs for treating a given ailment. V. W. Turner reports an interesting case: among Zambia’s Ndembu people, a healer told him that he uses the Kapwipu tree (S. madagascariensis) to treat stomach upset in children because the Kapwipu is a hard tree and hardness, for the Ndembu, symbolises strength and health. A similar consid- eration is given to the symbolic properties of cowries. Cowries are viewed as symbols of “womanhood, fertility, birth, and wealth” (Boone, 1986). This explains why they feature promi- nently in divination and fortune-telling routines. Finally, we will take a look at the symbols which fall within the indexical mode (Column 3 of the table). These are medical symbols which are not arbitrarily used because their usage is occasioned by the physician-priest’s effort to manage, induce or perceive a cause-and-effect situation in the life or circum- stances of the patient. Every act here is predictable or, at least, precise in interpretative terms. When the priest, for instance, sees a smoke emerging from his invocative pot, he knows im- mediately that “there is fire on the mountain”—he knows some evil has been devised against the patient. A cloudy wind from the west—where the sun sets—according to Mazi Okeke, a traditional healer from Abatete in south-eastern Nigeria, could be an indication that death is blowing over the head of his pa- tient. Similarly, the cry of an owl spells witchcraft as accurately as the spots on his neighbour’s child tells this healer the child is suffering from chicken pox. Dreams are also amenable to accu- rate interpretation as long as the dreamer can accurately recall all the actors which featured in the dream. Mode of ritual and worship are indexical symbols, as well, because they are not arbitrarily done but are constrained to follow long-standing traditional order. Conclusion In closing, it is important to state that even orthodox medical practitioners often assert that much of what ails their patients are psychosomatic rather than mere afflictions of the body. Since African traditional medical practice is dually oriented towards disorders of the soul and of the body, maybe there are some things both traditions can learn from each other for the overall benefit of the patient. And maybe the easiest way of achieving this much-needed synergy is through a renewed em- phasis on the conscious and subconscious roles traditional medical symbols could play—as they are currently playing in Asia—in Africa’s public health-care system. I modestly hope this paper has, in some way, contributed to the exegetic value of medical symbolism in Africa. REFERENCES Boone, S. A. (1986). Radiance from the waters: Ideals of feminine beauty in mende art. New Haven: Yale University Press. Bourdillon, M. F. C. (1989). Medicines and symbols. Zambezia, 16, 1. Chandler, D. (2012). Semiotics for beginners. An HTML Document Accessed on 2 September 2012. Chavunduka, G. L. (1988). African traditional medicine and modern science. Harare: University of Zimbabwe. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 120  I. NGANGAH Dukor, M. (2006). Theistic, panpsychic animism of African medicine. Essence, 3, 16. Dzobo, N. K. (1992). African symbols and proverbs as sources of knowledge. In K. Wiredu, & K. Gyekye, Person and community: Ghanaian philosophical studies I (Vol. 1). Africa: CRVP Series II. Gelfand, M. et al. (1985). The traditional medical practitioner in Zim- babwe. Gweru: Mambo Press. Isiguzo, A. I. (2010). African culture and symbolism: A rediscovery of the seam of a fragmented identity. Mbiti, J. S. (1991). Introduction to African religion. London: Heine- mann. Smith, A. K. (2011). Remarks concerning the methodology and sym- bolism of bon pebble divination. Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines, 42. Turner, V. W. (1967). Lunda medicine. In Forest of symbols: Aspects of ndembu ritual (p. 316). Ithan: Cornell University Press. Vargas, R. E. (2011). Language and thought in Aquinas: From the semantics of being to the epistemology of being. Milwaukee: Mar- quette University. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 121 |