Vol.3, No.1, 84-98 (2013) Open Journal of Preventive Medicine http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2013.31011 Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HIV/AIDS of Sudanese and Bantu Somali immigrant women living in Omaha, Nebraska* Shingairai Feresu1,2#, Lynette Smith3 1Department of Epidemiolo gy and Biostatistics, Indiana University, School of Public Health, Bloomington, USA; #Corresponding Author: sferesu@indiana.edu 2College of Health Sciences, Walden University, School of Health Sciences, Minneapolis, USA 3Department of Biostatistics, University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Public Health, Omaha, USA Received 27 September 2012; revised 30 October 2012; accepted 8 November 2012 ABSTRACT A needs assessment of the knowledge, attitudes, practices, and beliefs about HIV/AIDS prevention was conducted among 100 Sudanese and Bantu Somali women immigrants aged 19 years and older, recruited through a community organiza- tion between April and July 2006. Information was collected by interview using interpreters to administer a 60-item test and a 116-item ques- tionnaire that had been translated into Nuer and Arabic. Women in this study had low levels of education, poor knowledge about HIV transmis- sion and prev ention and saf er sex pr actices, an d poor attitudes to HIV/AIDS. They believe that HIV/AIDS is a punishment from God, HIV-posi- tive people should be separated from society, carrying a condom indicates having loose mor- als, women should not experience sexual plea- sure, and men should decide when and how to have sexual intercourse. Education, gender, and cultural beliefs are critical in the spread of HIV. Effort s to educate immigrant and displaced popu- lations, particularly women, are essential. Keywords: HIV Infection; HIV Transmission; HIV/AIDS Prevention; Condom Use; Safer Sex; Moral Beliefs about HIV/AIDS 1. INTRODUCTION Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) attacks the immune system and leaves the body vulnerable to AIDS, and to a variety of life-threatening infections and cancers [1,2]. Once a person has AIDS, they are prone infections by common bacteria, yeast, parasites, and viruses that usually do not cause serious disease in people with heal- thy immune systems but can cause fatal illnesses in peo- ple with AIDS [1,2]. The virus HIV has been found in saliva, tears, nervous system tissue and spinal fluid, blood, semen (including pre- seminal fluid, which is the liquid that comes out before ejaculation), vaginal fluid, and breast milk [1,2]. However, only blood, semen, vaginal secretions, and breast milk, have been shown to transmit infection to others. The virus can be transmitted through sexual contact including oral, vaginal, and anal sex; via blood transfusions (now extremely rare in the US) or needle sharing; and from mother to child, (a pregnant woman can transmit the virus to the fetus via the placentas through their shared blood circulation, or via breastfeeding) [1,2]. Other methods of transmitting the virus are rare and include accidental needle injury, artificial insemination with infected donated semen, and organ transpl a nt at i on wi t h in fect ed organs [1,2]. People who are infected with HIV may have no symptoms for 10 years or longer, but they can still trans- mit the infection to others during this symptom-free pe- riod [1-3]. If the infection is not detected and treated, the immune system gradually weakens and AIDS develops. Almost all people infected with HIV, if they are not treated, will develop AIDS [1-3]. Acute HIV infection progresses over time (usually a few weeks to months) to asymptomatic HIV infection (no symptoms) and then to early symptomatic HIV infection. Later, it progresses to AIDS (advanced HIV infection with CD4 T-cell count below 200 cells/mm3) [1-3]. A very small group of pa- tients who develop AIDS very slowly, or never at all. These patients are called nonprogressors, an d many seem to have a genetic difference that prevents the virus from significantly damaging their immune system [1-3]. The symptoms of AIDS are mainly the result of infections, called opportunistic infections, do not normally develop in people with a healthy immune system. People with *Funding source: Minority Health Education and Research Office, at the University of Nebr a ska Medical Center. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 85 AIDS have had their immune system damaged by HIV and are very susceptible to these opportunistic infections, including chills, fever, rash, sweats (particularly at night), swollen lymph glands, weakness and weight loss [1-3]. In terms of signs, CD4 cells commonly known as T cell or “helper cells” are used to diagnose if a person infected with HIV has AIDS or not. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a person may be diagnosed with AIDS if they are HIV-positive and have a CD4 cell count below 200 cells/mm3, even if they don’t have an opportunistic infection 1-3]. AIDS may also be diagnosed if a person develops one of the opportunistic infections and cancers that occur more commonly in people with HIV infection [1-3]. These infections are unusual in people with a healthy immune system. With a CD4 count below 350 cells/mm3, a per- son can develop Herpes simplex virus (causes ulcers/ small blisters in the mouth or genitals, happens more often and usually much more severely in an HIV- infected person than in someone without HIV infection); Herpes zoster (shingles) (ulcers/small blisters over a patch of skin, caused by reactivation of the varicella zoster virus, the same virus that causes chickenpox); Kaposi’s sar- coma (cancer of the skin, lungs, and bowel due to a her- pes virus (HHV-8). It can happen at any CD4 count, but is more likely to happen at lower CD4 counts, and is much more common in men than in women); Non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cancer of the lymph nodes); Oral or vaginal thrush (yeast (typically Candida albicans) in- fection of the mouth or vagina); Tuberculosis (infection by tuberculosis bacteria mostly affects the lungs, but can also affect other organs such as the bowel, lining of the heart or lungs, brain, or lining of the central nervous sys- tem (brain and spinal cord)) [1-3]. With CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3, a person can develop bacillary angiomatosis (skin sores caused by a bacteria called Bartonella, which may be caused by cat scratches) [1-3]; Candida esophagitis (painful yeast in- fection of the tube throu gh which food travels, called the esophagus) [1-3]; Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, “PCP pneumonia,” previously called Pneumocystis cari- nii pneumonia, caused by a fungus [1-3]. With CD4 count below 100 cells/mm3, a person can develop AIDS dementia (worsening and slowing of mental function, caused by HIV); Cryptococcal meningitis (fungal infec- tion of the lining of the brain); Cryptosporidiu m diarrhea (extreme diarrhea caused by a parasite that affects the gastrointestinal tract); Progressive multifocal leukoen- cephalopathy (a disease of the brain caused by a virus (called the JC virus) that results in a severe decline in mental and physical functions); Toxoplasma encephalitis (infection of the brain by a parasite, called Toxoplasma gondii, which is often found in cat feces); causes lesions (sores) in the brain; wasting syndrome (extreme weight loss and loss of appetite, cau sed by HIV itself) [1-3]. And with CD4 count below 50/mm3, the person develops Cy- tomegalovirus infection (a viral infection that can affect almost any organ system, especially the large bowel and the eyes); and Mycobacterium avium (a blood infection by a bacterium related to tuberculosis) [1-3]. In addition to the CD4 count, a test called HIV RNA level (or viral load) may be used to monitor patients. Basic screening lab tests and regular cervical Pap smears are important to monitor in HIV infection, due to the increased risk of cervical cancer in women with a compromised immune system. Anal Pap smears to detect potential cancers may also be important in both HIV-infected men and women [1-3]. There is no cure for AIDS at this time, however, a va- riety of treatments are available that can help keep symptoms at bay and improve the quality and length of life for those who have already developed symptoms [1-3]. Antiretroviral therapy suppresses the replication of the HIV virus in the body. A combination of several antiretroviral drugs, called highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), has been very effective in reducing the number of HIV particles in the bloodstream. This is measured by the viral load (how much free virus is found in the blood) [1-3]. Preventing the virus from replicating can improve T-cell counts and help the immune system recover from the HIV infection [1-3]. HAART is not a cure for HIV, but it has been very effective for the past 12 years. People on HAART with suppressed levels of HIV can still transmit the virus to others through sex or by sharing needles [1-3]. There is good evidence that if the levels of HIV remain suppressed and the CD4 count remains high (above 200 cells/mm3), life can be signifi- cantly prolonged and improved [1-3]. However, HIV may become resistant to one combination of HAART, especially in patients who do not take their medications on schedule every day [1-3]. Genetic tests are now available to determine whether an HIV strain is resistant to a particular drug, information which may be useful in determining the best drug combination for each person, and adjusting the drug regimen if it starts to fail [1-3]. The tests are performed any time a treatment strategy begins to fail, and before starting therapy [1-3]. Immigrants are at a higher risk than the general popu- lation of becoming HIV infected [4-6]. Additionally, immigrants are more likely than the general population to have poor access to HIV education or health services [5-14]. Immigrants are people who go into a foreign country on their own volition to establish permanent residence; refugees are those who are uprooted from their homes when fleeing danger or persecution and who receive special status in order to be given asylum in a host country [15,16]. Although the psychological profile of refugees has little in common with immigrants, there Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 86 is a tendency to group immigrants and refugees together. However, refugees in the United States can adjust their official status to immigrants after a year of residence [15]. The Sudanese and Bantu Somali people in the United States are refugees [17,18], who may or may not have adjusted their status to immigrants; in this paper, they will be considered immigr ants. The Sudanese immigrant population in Omaha, Ne- braska, which is the highest immigrant population from Africa in this state, is estimated at 5000 to 7000 [19], but their HIV prevalence is not known [20]. Sudan is North Africa and the Middle East region’s worst HIV-affected country [9,13,21,22]. The prevalence of HIV infection in Sudan was estimated at 1.6% in 2005, representing nearly 80% of HIV cases in the region [12,22]. About 2% of the adult population in Sudan was estimated to be liv- ing with HIV at the end of 2003 [23]. Sudan’s HIV epi- demic is concentrated in the south of the country, which is where most of the immigrant population in Omaha originated from [19,20]. Studies in Sudan report poor HIV/AIDS knowledge and high-risk behavior among southern Sudan populat i ons [22,24,2 5] . Bantu Somali immigrants in Nebraska are the second highest African immigrant population in the state. Their population in Nebraska is estimated at 2500; only 300 live in Omaha [20]. Bantu Somali people historically were slaves brought to Somalia from Tanzania, Mozam- bique, and Malawi, and they were marginalized in Soma- lia [19,26]. Bantu Somalis therefore have little in com- mon with other Somalis. During the civil war in Somalia in 1991, about 12,000 Bantu Somalis were displaced to Kenya, where they faced mistreatment in camps, includ- ing rape of women and beatings of men. In 1999 their population in the three refugee camps in Kenya was about 133,000 [26]. At that time, the United States des- ignated the Bantu Somali refugees in the camps as per- secuted and possible refugees to the United States, and they started arriving in the United States in 2003[19,26]. Somalia, although ranked among the world’s least-de- veloped countries, has a low prevalence of HIV/AIDS of 0.8% - 0.9% [27], but it is believed that HIV infection among Bantu Somali immigrants could be higher, as is common for refugees from war-torn regions [6,8,24, 28-31]. Estimates of HIV prevalence for Bantu Somali in Kenyan refugee camps or in Nebraska are not known. HIV prevalence is low in Nebraska, estimated at 0.004% [32,33], but the CD C reported that in 2003, 25% of all persons with HIV infection had not sought testing and were unaware of their status [34,35]. Given that HIV incidence is high in war-torn populations and subse- quently in refugee populations [6,24,28,29,31], that Su- dan has high rates of HIV infection, and that the HIV status for immigrants in Nebraska is not known, HIV may be more frequent among these immigrants, particu- larly women. HIV is of increasing concern in women in Africa [36,37] and it could also be worse for women immigrants than for male immigrants [6,37]. Women face a range of HIV-related risk factors and vulnerabili- ties that men and boys do not, many of which are em- bedded in the social relations and economic realities of their societies [36,38-44]. The vulnerability of women and girls to HIV infection stems not simply from igno- rance, but from their pervasive disempowerment [36, 38-40,42-44]. Additionally, most of the transmission in both the Sudanese and Bantu Somali populations is het- erosexual [40]. We therefore carried out this study to assess knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices re- garding HIV infection and prevention among Sudanese and Bantu Somali women immigrants of reproductive age. Because studies of this nature in this population are limited, this study was of critical importance. 2. METHODS 2.1. Study Design A needs assessmen t on the kno wledg e levels, attitud es, beliefs, and practices about HIV infection and AIDS was conducted for 100 Sudanese and Bantu Somali immi- grant women who resided in Omaha, Nebraska, between April and July 2006. An interview and a test were ad- ministered to all eligible women who agreed to partici- pate, had the study explained to them, and initialed an “unsigned” informed consent. With the help of the inter- viewers and interpreters, women first completed a test, and then completed the questionnaire. Two trained re- search assistants administered the questionnaire to the women, usually in their homes, with the help of two in- terpreters, one for Arabic-speaking subjects and the other for Nuer-speaking subjects. Due to the sensitivity of the questions, the interviews were administered to each woman face-to-face in private. Each interview lasted approximately 2 hours. The median time taken to com- plete the questionnaire was 30 minutes and ranged from 15 to 150 minutes. A sample size of 100 women would give us 80% power to detect the difference of 25% in correct knowledge of HIV between demographic groups. Since this study was descr iptive, this number was appro- priate. 2.2. Participants Sudanese and Bantu Somali immigrant women aged 19 years and older who resided in Omaha, Nebraska, were recruited for this study. This population included women born in Africa and first generation children born in the United States. Women were recruited to this study with the assistance of the Southern Sudan Community Association, a local resettlement organization. A con- venience sample of women from local homeless shelters, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 87 refugee resettlement centers, churches, and individual homes was approached to participate in the study. 2.3. Measures Previously validated questionnaires that have been used by organizations such as the World Health Organi- zation, the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, and the CDC, and in similar studies [19,45,46] were adapted for this study. The questionnaire and pretest were trans- lated into Arabic and Nuer and were pilot tested before use. The test contained 50 yes/no questions on mode of transmission of HIV infection, safe sex practices, and beliefs about HIV infection. The questionnaire aimed at soliciting information on the knowledge levels, attitudes, beliefs, and practices about HIV infection and AIDS. The questionnaire contained 116 items and was divided into five major sections: 1) demographic; 2) socioeconomic status; 3) knowledge about HIV/AIDS and safer sex; 4) attitudes about HIV/AIDS, and 5) knowledge about risk behavior. 2.4. Knowledge Scores Knowledge scores were created from the pretest ques- tions for three categories: transmission, safe sex, and protection. The transmission score is the number of cor- rect answers out of 14 possible from questions about HIV/AIDS transmission. The safe sex score is the num- ber of correct answers out of 5 possible from questions about safe sex. The protection score is the number of correct answers out of 9 possible from questions about HIV/AIDS p r o t ect i on. 2.5. Statistical Analysis Fisher’s exact test was used to compare individual questions by de mograph ic groups . The know ledge scores were compared between the groups with either t-tests or ANOVA. If significant differences were found pairwise, comparisons were made, with p-values adjusted for mul- tiple comparisons using Tukey’s method. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). 2.6. Ethical Considerations A letter of support and permission to study this popu- lation was obtained from the Southern Sudan Commu- nity Association, and Institutional Review Board ap- proval was obtained from the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Given the high level of stigma and sen- sitivity of the questions asked in this needs assessment, interviewers emphasized that participants were free to decline to answer any questions anytime during the in- terview. Interpreters were trained regarding confidential- ity. A total of 100 women who met the eligib ility criteria were interviewed face-to-face with the assistance of in- terpreters after an unsigned informed consent form had been explained to them and they had verbally agreed to participate and had in itialed the consent form. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents Demographic characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Of the 100 women who were interviewed, 86 were Sudanese immigrants and 14 were Bantu Somali immigrants. Prominent tribes were Nuer (26%) and Dinka (24%), and most women (64%) had lived in Omaha between 1 and 5 years. About 55% of the women were aged between 25 and 35 years, their median age was 30 years, ranging between 19 and 47 years. About 67% of the women was either married or liv ing as married. Twenty-eight percent of the women had no education, 36% had a primary school education, 22% had a high school education, and 14% had a college education. The number employed (49%) was almost the same as the number who were not employed. A few women (29%) earned $1000 per month and more, and the majority of the women (87%) and their families rented a home. 3.2. Health History and Sexual Patterns Table 2 summarizes the health and sexual history of this study population. In the last year, 24% of the women had not had a regular sex partner, 25% had had two to four sexual partners, and 76% had had one sexual partner. About 71% of the women had been pregnant after com- ing to the United States. Thirty-two percent had not been tested for HIV (n = 10) or were unsure (n = 13) if they had been tested. Seven of these 10 (70%) had not been told where to go to be tested, although 6 of 10 (60%) were interested in having an HIV test, as were 73% of all the women in the study. Two women had been told they had HIV infection, and 3 women had been told they had a sexually transmitted disease. 3.3. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS About 81% of the women knew that HIV causes or leads to AIDS, 61% thought results from HIV tests are always right, and 22% thought HIV/AIDS can be cured. About 76% of the women knew that the right medicines can help people who have HIV/AIDS live longer. Com- pared to Sudanese women, Bantu Somali women were less likely to agree that HIV causes or leads to AIDS (p = 0.010) and were less likely to agree that the right medi- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS 88 Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 100 Sudanese and Bantu Somali women interviewed on the HIV/AIDS Project, 2006. Mean HIV/AIDS knowledge scores are given for each characteristic. Transmission Knowledge S c o reSafe Sex Knowledge Score Protection Knowledge S core Freq.Percent Mean (SD)P-value Mean (SD) P-value Mean (SD) P-value Country of origin Sudan 86 86% 10.2 (2.4) 0.27 3.2 (1.2) 0.0014 6.3 (1.8) 0.56 Somalia 14 14% 9.5 (2.2) 1.3 (1.7) 6.6 (1.6) Tribe Nuer 26 26% 9.7 (1.9) 0.088 3.3 (1.2) <0.0001 6.0 (1. 9) 0.0047 Dinka 24 24% 10.7 (2.5) 2.9 (1.0) 6.9 (1.2) Acholi 7 7% 8.4 (4.5) 2.6 (2.0) 4.4 (3.0) Kiziguwa 9 9% 9.7 (1.8) 2.0 (1.8) 7.3 (1.6) Maimai 5 5% 9.2 (2.9) 0 (0) 5.4 (0.9) Other 29 29% 10.8 (1.7) 3.4 (1.0) 6.7 (1.5) Years lived in Omaha <1 15 15% 10.3 (1.8) 0.77 3.0 (1.2) 0.49 6.9 (1.7) 0.32 1-5 64 64% 10.2 (2.6) 2.8 (1.5) 6.4 (1.7) >=5 21 21% 9.8 (1.9) 3.2 (1.2) 6.0 (2.2) Age group <25 22 22% 10.0 (2.9) 0.96 2.5 (1.6) 0.24 6.6 (2.1) 0.81 25-35 55 55% 10.2 (2.0) 3.0 (1.3) 6.3 (1.6) >35 23 23% 10.1 (2.7) 3.0 (1.4) 6.3 (2.0) Marital status Married/Living together 67 67% 10.4 ( 1.8) 0.27 2.9 (1.5) 0.87 6.6 (1.6) 0.34 Single 11 11% 9.5 (3.7) 2.7 (1.5) 6.3 (2.5) Sepa- rated/Divorced/Widowed 22 22% 9.6 (3.0) 3.0 (1.2) 5.9 (1.9) Education No education 28 28% 9.6 (2.0) 0.055 2.1 (1.6) 0.0010 6.1 (1.7) 0.76 Primary school 36 36% 9.9 (2.4) 3.0 (1.3) 6.6 (2.0) High school 22 22% 10.3 (2.6) 3.1 (1.0) 6.3 (1.7) College 14 14% 11.6 (1.9) 3. 9 (1.0) 6.6 (1.7) Employed Yes 49 49% 10.5 (1.8) 0.096 3.3 (1.0) 0.0094 6.4 (1.7) 0.89 No 51 51% 9.8 (2.7) 2.6 (1.6) 6.4 (1.9) Family income/month <$500 13 13% 9.2 (4.5) 0.062 1.9 (1.2) 0.0095 5.9 (2.4) 0.40 $501 - 1000 21 21% 9.7 (1.9) 3.3 (1.1) 6.0 (1.8) $1001 - 1500 17 17% 10.2 (1.3) 3.2 (1.0) 6.2 (1.3) >$1500 12 12% 11.8 (1.8) 3.6 (1.2) 6.8 (2.2) Unreported 37 37% 10.1 (1. 9) 2.6 (1.6) 6.7 (1.6) Residence Own home 11 11% 10.6 (1.7) 0.42 3.2 (1.1) 0.49 6.5 (2.1) 0.71 Rent 87 87% 10.0 (2.4) 2.9 (1.4) 6.3 (1.8) Other 2 2% Transmission Knowledge Score is scored from 0 to 14. Safe Sex Knowledge Score is scored from 0 to 5. Protection Knowledge Score is scored from 0 to 10.  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 89 Table 2. HIV infection related health history for 100 Sudanese and Bantu Somali women interviewed on the HIV/AIDS project; 2006. Question Frequency Percent Do you have a husband or a re g ula r sex partner? Yes 76 76.0 No 24 24.0 Number of sex partners 0 3 3.0 1 71 71.0 2 - 4 23 23.0 Unreported 3 3.0 How many sex partners have h ad in the p ast 1 year 0 24 24.0 1 76 76.0 Have you been pregnant since you came to the United S tates? Yes 71 71.0 No 26 26.0 Not sure 3 3.0 If you had been pregna n t since coming to the USA, were you e v e r tested for HIV? Yes 47 67.1 No 10 14.3 Not sure 13 18.6 If you had been pregnant since coming to the USA and not tested for HIV, were you told where to go to b e tested for HIV? Yes 6 16.7 No 25 69.4 Not sure 5 13.9 If you were tested for HIV, what was the result? Negative 53 53.0 Not sure 45 45.0 No response 2 2.0 Have you ever been told that you ha ve HIV/AIDS? Yes 2 2.0 No 87 87.0 Not sure 11 11.0 Have you ever been told that you have a sexually transmitted disease such as Chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis Yes 3 3.0 No 94 94.0 Not sure 3 3.0 Would you like to have an HIV test? Yes 73 73.0 No 26 26.0 Not sure 1 1.0 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS 90 cines can help people who have HIV/AIDS live longer (p = 0.024). Women who had no education or a primary school education were more likely than women with a high school or college educatio n to indicate that HIV test results are always right (p = 0.001), while women with a high school or college education were more likely to indicate that there are things one can do to protect one- self against HIV/AIDS (p = 0.018). 3.4. Knowledge about Modes of HIV Transmission Fourteen questions addressed the ways that HIV can be transmitted and knowledge of transmission by bodily fluids [data not shown]. About 50% of the women re- ported that HIV can be transmitted by a mosquito or other insect bite. At least 14% of the women thought HIV can be transmitted by swimming in the same pool as someone who has HIV/AIDS, and 16% were not sure. About 36% of the women thought that HIV can be transmitted by sharing a spoon or fork with someone who has HIV/AIDS. Most women (82%) knew that HIV/AIDS cannot be transmitted by sharing food with someone who has HIV/AIDS. The majority of the women (85%) knew that HIV/AIDS cannot be transmit- ted by shaking hands with someone who has HIV/AIDS. Sixteen percent of the women reported that HIV/AIDS can be transmitted by exposure to the coughing or sneezing of someone who has HIV/AIDS. Regarding whether HIV/AIDS can be transmitted by kissing some- one on the mouth who has HIV/AIDS, 39% agreed, 39% disagreed, and the rest were not sure. About 20% of the women reported that HIV can be transmitted by using a public bathroom. Bantu Somali women were more likely than Sudanese women to indicate that HIV/AIDS can be transmitted by a mosquito bite or other insect bite (p = 0.002), by swimming in the same pool as someone who has the disease (p = 0.0001), by sharing a spoon or folk with someone who has the disease (p = 0.04), by kissing someone on the mouth who has the disease (p = 0.032), and by using a public bathroom (p = 0.042). These find- ings were similar for women of all education levels (p values = 0.001, 0.03, 0.05, and 0.02 for women with no education, a primary school education, a high school education, and a college education, respectively). Unem- ployed women (p = 0.012) were more likely than em- ployed women to indicate that one can get HIV/AIDS from a mosquito bite. In general women had good knowledge on the trans- mission of HIV/AIDS by bodily fluids. The majority of women (93%) knew that HIV/AIDS can be transmitted by sharing a razor for shaving with someone who has HIV/AIDS, by reusing sharp medical equipment that has bodily fluids on it from someone who had HIV/AIDS, and by using the same needle to take drugs as someone who has HIV/AIDS. About 96% of the women knew that HIV/AIDS can be transmitted by getting a blood transfu- sion from someone who has HIV/AIDS. About 77% of the women believed that a mother who has HIV/AIDS can transmit it to her child during childbirth. Bantu So- mali women were less likely than Sudanese women (p = 0.005) to report that a mother can transmit HIV/AIDS to her child during childbirth, as were unemployed com- pared to employed women (p = 0.024). Also, 76% of the women knew that a mother who has HIV/AIDS can transmit it to her child by breastfeeding. The above 14 questions were scored as correct and incorrect responses (Table 1). The overall mean for transmission score was 10.1 (SD = 2.3, range 0 to 14). There were no statistically significant differences in the mean score of women responding co rrectly to HIV /AIDS transmission questions by country of origin, tribe, the number of years lived in Omaha, age group, marital status, education, employment status, family income, or owning or renting their residence. 3.5. Knowledge of Safer Sex Women had mixed views on sexual transmission of HIV/AIDS [data not shown]: 27% did not know that a person can get HIV/AIDS the first time he or she has sex, 24% disagreed or were unsure that safe sex means hav- ing protected sex, and 32% disagreed or were unsure that protected sex means your partner wearing a condom even for foreplay. Seventy-six percent of the women agreed that heterosexual sex means men having sex with a woman, and 43% disagreed or were unsure that homo- sexual sex means men having sex with men or women having sex with women. Women had poor knowledge about anal sex: 13% disagreed that anal sex is performed only when a man is having sex with another man, and 41% were not sure. Women who had a high school or college education were more likely th an women who had no education or a primary school education to agree that safe sex means having protected sex (p = 0.01), protected sex means your partner wearing a condom even for foreplay (p = 0.01), and anal sex is performed only when a man is having sex with another man (p = 0.01). Bantu Somali women were more likely than Sudanese women to agree that safe sex means having protected sex (p = 0.001), protected sex means your partner wearing a condom even for foreplay (p = 0.02), and anal sex is performed only when a man is having sex with another man (p = 0.05). Bantu Somali women were more likely than Su- danese women to report that heterosexual sex is men having sex with women (p = 0.0001) and homosexual sex is men having sex with men and women having sex with women (p = 0.02). Employed women were more  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 91 likely than unemployed women to indicate that safe sex means having protected sex (p = 0.03) and that hetero- sexual sex means men having sex with women, (p = 0.02). Five questions formed the scores on knowledge about safer sex (Ta ble 1). The overall mean for safe sex score was 2.9 (SD = 1.4, range 1 to 5). There were statistically significant differences in the mean score of women get- ting correct responses for knowledge about safer sex by country of origin, tribe, education, employment status, and family income. Tribal differences were found be- tween MaiMai and Acholi, Dinka, Kiziguwa, and Neur. There were marginal group differences for no education compared to a primary school education (p = 0.064) but significant differences between no education compared to a high school education (p = 0.04) and no education compared to a college education (p = 0.001). Also, there were group differences between those with income of <$500 compared to those with in come $501 - $10 00 (p = 0.038) and between those with income < $500 compared to those with income > $1500 (p = 0.021). 3.6. Knowledge about Sexual Protection Nine questions formed the knowledge about sexual protection score, and women had varied responses on these issues. Seventy-six percent knew that wearing an amulet around the waist does not protect a person against HIV/AIDS, only 27% thought that limiting the number of people one has sex with protects a person against HIV/AIDS, and 19% did not know that taking antibiotic drugs before having sex does not protect a person against HIV/AIDS. Thirty-three percent of the women did not know that using a condom during sex protects a person against HIV/AIDS, and 44% of the women disagreed or were unsure that not having sex pro tects a person again st HIV/AIDS. Bantu Somali women were more likely than Sudanese women to believe that wearing an amulet around the waist protects a person against HIV/AIDS (p = 0.01). About 21% of the women agreed or were unsure that having sex only with people who look healthy protects a person against HIV/AIDS, and 29% of the women thought that men who do not have sex with other men are protected against HIV/AIDS. Only 45% of the women believed that not having sex with prostitutes (sex work- ers) protects a person against HIV/AIDS, and about 16% of the women believed that seeing a traditional healer does not protect a person against HIV/AIDS. Women with a high school or college education were more likely than uneducated women or women with a primary school education to believe that not having sex with prostitutes (sex workers) protects a person against HIV/AIDS (p = 0.03). About 55% of the women agreed that using sterile needles to inject drugs protects a person against HIV/ AIDS; 35% di sagr eed, and 10 % we re n ot sure. The overall mean for protection score was 6.4 (SD = 1.8, range 1 to 9). Only the mean scores for tribe were statistically significantly different from each other. The mean score was different for Acholi compared to Dinka, Kiziguwa, and other. There were no statistically signifi- cant differences in mean score of knowledge about pro- tection against HIV/AIDS by country of origin, years lived in Omaha, age group, marital status, education, employment status, family income, or whether they owned or rented their residence. 3.7. Beliefs about Safer Sex In terms of condom use, women were asked several questions about using condoms (Table 3). About 84% had not used a condom, 53% indicated that they would not want to use a condom without spousal or partner ap- proval, and 61% indicated they would still have sex without a condom even if they suspected infidelity. Women were asked about their beliefs on condom use: 36% agreed with the statement, “I believe that that using a condom during sexual intercourse reduces sexual pleasure,” and 25% agreed with the statement, “I believe that if I had sex several times with a man, he would be safe, no need to use condom.” Women with no education or a primary school education were more likely than women with a high school or college education to agree with that statement (p = 0.001). Women who had used a condom were more likely than women who had not used a condom to believe that people can get HIV the first time they have sex (p = 0.018) and that people with HIV should be separated from society (p = 0.018). Women who refused to have sex without a condom if a partner had been unfaithful were more likely than women who used a con dom to agre e that the righ t medici nes can help people live longer (p = 0.010), HIV can be transmitted by sharing needles (p = 0.049), a mother who has HIV/ AIDS can transmit it to her child by breastfeeding (p = 0.031), safe sex means protected sex (p = 0.021), and heterosexual sex means men having sex with women (p = 0.0001). About 59% disagreed with the statement, “I believe that I will be safe if I perform oral sex without protection.” The women’s intentions about safer sex were also solicited (Table 3). Ninety-four percent of the women intended to have sex with one partner. About 27% of the women disagreed with the statement, “I in- tend to and make sure that if I have sex with a new part- ner, they are tested and retested at 6 months,” with Bantu Somali women being less likely th an Sud an ese women to agree with that statement (p = 0.05). 3.8. Moral Beliefs about HIV/AIDS Women were asked to respond to statements on their Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS 92 Table 3. Beliefs safer sex for 100 Sudanese and Bantu Somali women interviewed on the HIV/AIDS project; 2006. Belief Frequency Percent Have you ever used a condom as a means of protection against HIV/AIDS with your sexual partner Yes 13 13.00 No 84 84.00 Not sure 3 3.00 The reason I do not prefer a condom is because my husba nd or partner does not approve of it Agree 53 53.0 Disagree 26 26.0 Not sure 21 21.0 If you suspect that your husband or regular partner is having sex with other women do you refuse to have sex with him without a condom Yes 61 61.00 No 34 34.00 Not sure 5 5.00 I believe that that using a condom during sexual intercourse reduces sexual pleasure Agree 36 36.0 Disagree 18 18.0 Not sure 46 46.0 I believe that if I had se x several times with a man, he would be safe, no need to use condom Agree 25 25.0 Disagree 53 53.0 Not sure 22 22.0 I believe that I will be safe if I perform oral sex wit hout protection Agree 13 13.0 Disagree 59 59.0 Not sure 28 28.0 I believe that only m en who have sex with men and those who use illegal drugs get HIV/AIDS Agree 43 43.0 Disagree 38 38.0 Not sure 19 19.0 I intend to have sex with one partner Agree 94 94.0 Disagree 5 5.0 Not sure 1 1.0 I intend to and make sure that if I have sex with a new partner, they are tested and retested at 6 months Agree 73 73.0 Disagree 16 16.0 Not sure 11 11.0  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 93 Table 4. Moral and gender beliefs about HIV/AIDS for 100 Sudanese and Bantu Somali women interviewed on the HIV/AIDS pro- ject; 2006. Belief Frequency Percent I believe that people ge t HIV/AIDS as a punishm e nt for doing something wrong Agree 38 38.0 Disagree 56 56.0 Not sure 6 6.0 I believe that someone who gets HIV/AIDS deserves to suffer Agree 34 34.0 Disagree 57 57.0 Not sure 9 9.0 I believe that people with HIV/AIDS should be separated from the rest of society Agree 46 46.0 Disagree 45 45.0 Not sure 9 9.0 I believe that getting AIDS is a punishment from God Agree 25 25.0 Disagree 68 68.0 Not sure 7 7.0 I believe that God decid es w h o g e t s HIV/AIDS Agree 11 11.0 Disagree 82 82.0 Not sure 7 7.0 I believe that women should not experience pleasure during s e x Agree 15 15.0 Disagree 63 63.0 Not sure 22 22.0 I believe that men should make the decision about when and ho w t o h a ve se x ua l i n te rcourse Agree 40 40.0 Disagree 53 53.0 Not sure 7 7.0 moral beliefs about HIV/AIDS (Table 4). Thirty-eight percent of the women agreed with the statement, “I be- lieve that people get HIV/AIDS as a punishment for do- ing something wrong”; 34% agreed with the statement, “I believe that someone who gets HIV/AIDS deserves to suffer”; 46% agreed with the statement, “I believe that people with HIV/AIDS should be separated from the rest of society”; and 25% agreed with the statement, “I be- lieve that getting AIDS is a punishment from God.” But, 82% disagreed with the statement, “I believe that God decides who gets HIV/AIDS.” Bantu Somali women were more likely than Sudanese women to agree that God decides who gets HIV/AIDS (p = 0.02). With regards to of how women viewed their role versus men, in terms of sexual intercourse (Table 3 ), at least 15% of the women agreed with the statement, “I believe that women should not experience pleasure dur- ing sex,” and 40% agreed with the statement, “I believe Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 94 that men should make the decision about when and how to have sexual intercourse.” 4. DISCUSSION We had a unique opportunity to interview Sudanese and Bantu Somali immigrant women living in Omaha, Nebraska, on their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs re- garding HIV/AIDS. We found that a quarter of these immigrant women had more than one sex partner and that about 70% had not been tested for HIV but ex- pressed a desire to be tested. Employment rate was high among this group. The education level was low among this group and is of great concern, as it seems to impact knowledge about HIV infection and its transmission. Condom use among these women was very low and is another source of concern, particularly because 25% had more than one sex partner. Moral issues and gender dis- parities as they relate to sex and acquiring HIV infection still play a significant role in this population. Many women in this group had a regular sex partner, but a worrisome 23% of the respondents had two to four sex partners. This is not an uncommon finding for immi- grant populations, given the difficult situation they find themselves in, which makes them prone to promiscuous behavior, as was reported in other studies [24,31,46-48]. A significant number of women had been pregnant after they came to the United States, most of who had not been tested for HIV infection, did not know where they could be tested, wanted to be tested. Systems factors in Omaha may have affected the women’s ability to access volun- tary counseling and testing for HIV. Often, structural, cultural, and linguistic barriers; stigma; discrimination; xenophobia; and exploitation decrease or discourage ac- cess to HIV/AIDS education or health services [6,15-19, 47-53]. The employment rate is quite high for this population, where 50% were employed compared to 26.5% of women in Sudan being in the labor force and 7.6% formally em- ployed in professional jobs in 2004 [54]. Refugees in Nebraska can get cash assistance and medical assistance only for the first eight months after they arrive in the United States and get a certain percent of benefits on a sliding scale thereafter only if they are employed or at- tending school [55]. Therefore, most women have to work. The available benefits are minimal and the salaries in general are very low (29% earned $1000 per month or more). Unemployment can result in risky sexual behavior, sex in return for favors, and prostitution. Studies have shown that lack of employment, economic difficulties, and poverty, are risk factors for risky sexual behavior and HIV [47,56-58]. We found that the level of education among this group was low, a significant cause of concern. A significant proportion of the study population (36%) had only a primary school education, 28% had no education at all, 22% had a high school education, and only 14% had at- tended college. A low level of education is common in refugee populations [19,46] and in African countries, where the average literacy rate was 60%, adult literacy at 46%, in 2000 [59] In most African countries, education of women is nonexistent or minimal. According to World Bank estimates for 2002, the literacy rate in adults aged 15 years and older was 60 percent. In 2000 the compara- ble figure was almost 58 percent (69 percent for males, 46 percent for females); youth illiteracy (ages 15 - 24) was estimated at 23 percent, and a gender gap of 23% [60]. Somalia, although not necessarily representative of Bantu Somali immigrants, has not reported its literacy level since 1990 [60]. The link between education and risk of HIV is unclear. Studies in Africa have linked higher education level with increased risk of HIV infec- tion [61-63]. In essence, having an education cannot be interpreted as having significant knowledge of HIV and its transmission. However, other studies have found a protective effect of a higher education level [36,62,64, 65]. Although the role of higher education in understanding HIV infection is debatable, education may facilitate be- havior change and promote the adoption of safer sexual behaviors, including condom use [36,51,63]. In their review, Hargreaves and Glynn concluded that new HIV infections were increasingly seen among less educated women [61]. There was a general lack of knowledge among the women in this study about HIV/AIDS and whether it could be cured, thus was more evident among Bantu Somali and less educated women had poor knowledge. Bantu Somali women have lived in refugee camps since the 1990s [18,26], where there would have been little opportunity to learn about health issues relating to HIV infection. Conflicting notions exist on the relationship between lack of knowledge and HIV/AIDS infection, with some studies some studies reporting a connection [24,43-46,49,56], while others studies not finding that relationship [6,66]. In general, this study population had poor knowledge about HIV transmission. Regarding the common HIV transmission myths, there was poor knowledge on HIV transmission for Bantu Somali, less educated, unem- ployed women, and newer immigrants. These results show a lack of knowledge and understanding of HIV transmission, poses a significant risk for acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Some studies found similar findings to ours [19,24,43,45,46], some found mixed results [ 24,49-50,64 ], while other s found no relationship [6,67]. Knowledge among this study’s participants on trans- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 95 mission by bodily fluids was encouraging, and this find- ing is consistent with other studies [49,68]. Half of the women knew that using sterile needles could protect a person against HIV infection, but this mode of transmis- sion is responsible for fewer cases of HIV transmission than other modes. Knowledge of mother-to-child trans- mission was fair, an uncommon finding by other studies [67], and three quarters of the single and unemployed and Bantu Somali women had the poorest knowledge. On scoring of the 14 questions on HIV transmission, there were differences among these women by socio- demographic characteristics. Less educated, unemployed, and Bantu Somali women had poor knowledge of safer sex. Differences for this population in knowledge of safer sex were also seen based on tribe and income level. About 25% of the women did not understand the meaning of protected sex. Oral sex was seen as protective. The poor knowledge on safer sex is consistent with other studies [19,44,46]. Some of the women had a moderate amount of knowl- edge about sexual pro tection myths, as has been reported by other studies [19,46,58,68], but Bantu Somali women and newer immigrant women had poor knowledge on this issue. Many study participants judged a HIV risk by a person’s appearance and whether a person engaged in prostitution. Newer immigrant women still believe that people can protect themselves against HIV infection by consulting a traditional healer. Tribal differences were seen in responses to sexual protection questio ns. The low rates of condom use in this group are another source of concern: 84% of the women had never used a condom. Of these, 53% do not use a condom because their partner does not approve, and 25% believe that having sex several times with a man reduces the chances of getting infected. Only two-thirds of the women would refuse to have sex if they suspected that their husband was promiscuous. Use of condoms with regard to HIV infection prevention has always been challenging, as reported by other studies from Africa [40,43,44,66-68], and from other refugee populations [6,19,46,49]. The finding that condoms were thought to reduce sexual pleasure is in agreement with findings from other studies [40,45,46,48,49,66]. More worrisome was that a quarter of the women reported that if they had used condoms during sex for a period of time with a partner, they would feel safe. Moral issues played a significant role in this popula- tion: over a third of the women connected acquiring HIV infection to immorality and saw HIV infection as a pun- ishment from God, although a few saw this as God’s will. Other studies have found similar findings [43,51,66]. Men were seen as having control during sex. This finding is common in African countries, which are patriarchal and where women are not empowered, including about having control over their bodies [40,44,66]. Intentions toward safer sex for the most part were positive, but ex- cept among Bantu Somali, separated, divorced, and widowed wom e n. 5. STRENGTH OF THE STUDY Nonetheless, this study is one of the few to be carried out in this population and the first women-only study in this population. This study under scores th e importance of women in immigrant populations, as women’s views and knowledge tend to affect the health of families in a given population. The study is the first step in identifying needs for HIV/AIDS education, and if followed by targeted health education messages, will be critical for preventing HIV/AIDS burden in similar populations. 6. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY This study had some limitations. A potential difficulty was the language barrier, which was minimized by em- ploying a Sudanese student, using interpreters, and trans- lating the consent form and questionnaires. It is possible that just by explaining some of the survey items during the interviews could have influenced the responses to- wards more positive picture about the knowledge of HIV/AIDS. Another concern was the sensitiv ity of ques- tions asked, which was overcome by using interviewers who were mature black females and recent immigrants from the same or an adjacent country as the study popu- lation. A convenience sample was drawn for this study, and thus may not be representative of the Sudanese and Bantu Som a l i wome n in Omaha, Nebraska. 7. CONCLUSION In conclusion, our results suggest that a lower level of education impacts knowledge of transmission and pre- vention of HIV. Therefore there is need to develop an education program to specifically target these women and educate them about HIV transmission and the means by which they can protect themselves. The fact that few women had been tested for HIV and that the majority of these women expressed the desire to be tested may indi- cate some disconnect between the needs and the delivery system priorities, and thus needs to be addressed. Lim- ited data, particularly for women, on HIV/AIDS exists in this population. This stud y underscores the need to shape policy regarding access to care for immigrants. Thus, studies such as this one will assist policy makers and resettlement agencies to plan for interventions in these communities. Although our study interviewed 100 women, there is need to expand services to more immi- grant women in Nebraska. Health education programs which are culturally sens itive will help reduce barriers to HIV/AIDS education in this immigrant po pulation and in similar settings. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 96 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The project was funded through the Minority Health Education and Research Office at the University of Ne- braska Medical Center. The authors acknowledge Mr. Tor Kuet of the Southern Sudan Community Association and his staff; Anna Odipo-Nyambok, and Christine Ross who were research assistants; and Richard Stacy, professor of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, College of Education, University of Nebraska at Omaha, for the work they did on the project. We also acknowledge Ireen Bwalya, graduate assistant, for helping with preparation of this manuscript, and Sue Nardie for editing this manuscript. REFERENCES [1] UNAIDS (2000) Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS. Migrant populations and HIV/AIDS. The development and implementation of programmes: Theory methodology and practice. Geneva. http://data.unaids.org/publications/IRC-pub01/jc397-migr antpop_en.pdf [2] UNAIDS (2001) Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS. Population mobility and AIDS. UNAIDS technical update. http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub02/JC513-Pop Mob-TU_en.pdf [3] Rosenthal, L., Scott, D.P., Kelleta, Z., Zikarge, A., Mo- moh, M., Lahai-Momoh, R.M.W. and Baker, A. (2003) Assessing the HIV/AIDS health services needs of African immigrants to Houston. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 570-580. doi:10.1521/aeap.15.7.570.24047 [4] UNAIDS (2004) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Migrants’ right to health. Unaids/Iom State- ment on HIV/AIDS-related travel restrictions. UNAIDS technical update. http://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/site/myjahiasite/shared/ shared/mainsite/activities/health/UNAIDS_IOM_stateme nt_travel_restrictions.pdf [5] UNAIDS (2004) Report on the global HIV/AID epidemic: 4th global report. http://data.unaids.org/Global-Reports/Bangkok-2004/unai dsbangkokpress/gar2004html/gar2004_00_en.htm http://www.un.org.np/sites/default/files/report/tid_107/Gl obal_Report_2004.pdf [6] UNAIDS/WHO (2004) AIDS epidemic update. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/data import/pub/report/2004/2004_epiupdate_en.pdf [7] UNIADS (2005) AIDS epidemic update. http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub06/epi_update 2005_en.pdf [8] UNAIDS (2006) REPORT on the global aids epidemic global report chapter 2: Overview of the global AIDS epidemic. http://data.unaids.org/pub/GlobalReport/2006/2006_gr_c h02_en.pdf [9] UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS (2006) Epidemic update. http://data.unaids.org/pub/EpiReport/2006/2006_EpiUpda te_en.pdf [10] UNAIDS/WHO (2006) Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections. http://www.who.int/globalatlas/predefinedReports/EFS20 06/EFS_PDFs/EFS2006_SD.pdf [11] UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS (2007) Epidemic update. http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdat e_en.pdf [12] Segal, U.A. and Mayadas, N.S. (2005) Assessment of issues facing immigrant and refugee families. Child Wel- fare, 84, 563-583. [13] Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (2007) Refugee resettlement program population defini- tions. http://dhhs.ne.gov/children_family_services/Pages/refuge es_definitions.aspx [14] Jaranson, J.M., Butcher, J., Halcon, L., Johnson, D.R., Robertson, C., Savik, K., Spring, M. and Westermeyer, J. (2004) Somali and Oromo refugees: Correlates of torture and trauma history. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 591-598. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.4.591 [15] Owens, C.W., Johnson, B. and Iman, H. (2003) Somali bantu refugees. Notes from the Refugee Community Building Conference, Sea Tac. http://ethnomed.org/cultures/somali/somali_bantu.html [16] Tompkins, M., Smith, L., Jones, K. and Swindells, S. (2006) HIV education needs among Sudanese immigrant and refugees in the Midwestern United States. AIDS and Behavior, 10, 319-323. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-9060-8 [17] (2003) Nebraska department of health and human ser- vices system. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. http://dhhs.ne.gov/Documents/AIDSSurv06.pdf [18] UNIADS and WHO (2005) Middle East and North Africa fact sheet. http://data.unaids.org/Publications/Fact-Sheets04/fs_men a_nov05_en.pdf [19] UNIAIDS AIDS Update (2006) Middle East and North Africa. http://data.unaids.org/pub/epireport/2006/2006_epiupdate _en.pdf [20] UNIADS and World Health Organization (WHO) (2004) Sudan: Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections 2004 update. Fact sheet. http://data.unaids.org/Publications/Fact-Sheets01/sudan_e n.pdf [21] Holt, B.Y., Brady, W., Belay, E., Toole, M., Effler, P., Friday, J. and Parker, K. (2003) Planning STI/HIV pre- vention among refugees and mobile populations: Situa- tion Assessment of Sudanese refugees. Disasters, 27, 1- 15. doi:10.1111/1467-7717.00216 [22] Kaiser, R., Kedamo, T., Lane, J., Kessia, G., Handzel, T. et al. (2004) HIV/STI prevalence and risk factor surveys in Yei and Rumbek, South Sudan, 2002/2003. 15th Inter- national AIDS Conference, Bangkok, 11-16 July 2004, Abstract T uPeC4 739. [23] Lacey, M. (2001) Somali Bantu, trapped in Kenya, seek a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 97 home. The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/ gst/f ullpag e.ht ml?re s=9A03E5 DB1E3CF93AA35751C1A9679C8B63 [24] UNIADS and World Health Education. Somalia (2006) HIV epidemic and its response 2003-2005, draft report on the UNGASS declaration of commitment. December, summary country profile for HIV/AIDS treatment scale-up. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2006/2006_country_pro gress_report_somalia_en.pdf [25] UNAIDS (2000) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Migrant populations and HIV/AIDS. UN- AIDS technical update. http://data.unaids.org/publications/IRC-pub01/jc397-migr antpop_en.pdf [26] UNAIDS (2001) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Edited by Margaret Duckett, Migrants’ right to health. http://data.unaids.org/publications/IRC-pub02/jc519-migr antsrighttohealth_en.pdf [27] UNIADS (2006) Country progress report 2006 Somalia (952K) monitoring the declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS—2005 country progress reports. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2006/2006_country_pro gress_report_somalia_en.pdf [28] Hankins, C.A., Friedman, S.R., Zafar, T. and Strathdee, S.A. (2002) Transmission and prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in war settings: Implica- tions for current and future armed conflicts. AIDS, 16, 2245-2252. doi:10.1097/00002030-200211220-00003 [29] (2004) Nebraska department of health and human ser- vices system. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. http://nlc1.nlc.state.ne.us/epubs/H8220/B002-2004.pdf [30] (2006) Nebraska department of health and human ser- vices system. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. http://dhhs.ne.gov/Documents/AIDSSurv06.pdf [31] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005) Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses-33 States, 2001-2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 54, 1149-1153. [32] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008) Per- sons tested for HIV-United States 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Wee kly Report, 57, 845-849. [33] UNAIDS (2005) Uniting the world against AIDS: Women. http://www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/200605-FS_SubSaha ranAfrica_en.pdf [34] UNAIDS Global Coalition on Women and AIDS (2005) Empowering women, fighting aids. Economic security for women fights AIDS. Issue 3. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/data import/publications/irc-pub07/ jc1251-keepingpromise-small _en.pdf [35] Krishnan, S., Dunbar, M.S., Minnis, A.M., Medlin, C.A., Gerdts, C.E. and Padian, N.S. (2007) Poverty, gender in- equities and women’s risk of HIV/AIDS. Scientific ap- proaches to understanding and reducing poverty. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1-18. [36] Rankin, S.H., Lingren, T., Rankin, W.W. and Ngoma, J. (2005) Donkey Work: Women, religion, and HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Health Care for Women International, 26, 4- 16. doi:10.1080/07399330590885803 [37] UNAIDS Global Coalition on Women and AIDS (2007) Increase women’s control over HIV prevention fight AIDS. Newsletter Issue 4. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/data im- port/publications/irc-pub07/jc1237-gcwa-prevention-4_en .pdf [38] UNAIDS/WHO (2004) Women and AIDS, and extract from December 2004 epidemic update. http://data.unaids.org/gcwa/jc986-epiextract_en.pdf [39] Ackermann, L. and de Klerk, G.W. (2002) Social factors that make South African women vulnerable to HIV infec- tion. Health Care for Women International, 23, 163-172. doi:10.1080/073993302753429031 [40] Duffy, L. (2005) Culture and context of HIV prevention in rural Zimbabwe: The influence of gender and inequal- ity. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 16, 25-31. doi:10.1177/1043659604270962 [41] Harrison, A., O’Sullivan, L.F., Hoffman, S., Dolezal, C. and Morrell, R. (2006) Gender role and relationship norms among young adults in South Africa: Measuring the context of masculinity and HIV risk. Journal of Ur- ban Health, 83, 709-722. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9077-y http://www.springerlink.com/content/h074pg77g4t41726/ fulltext.html [42] Mbirimtengerenji, N.D. (2007) Is HIV/AIDS epidemic outcome of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa? Croatian Medical Journal, 48, 605-617. [43] Wang, J., et al. (2001) Level of AIDS and HIV knowl- edge and sexual practices among sexually transmitted disease patients in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 28, 171-175. doi:10.1097/00007435-200103000-00009 [44] Lazarus, J.V., Himedan, HM., ØStergaard, LR and Lil- jestrand, J. (2006) HIV/AIDS knowledge and condom use among Somali and Sudanese immigrants in Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 34, 92-99. doi:10.1080/14034940510032211 [45] Foley, E.E. (2005) HIV/AIDS and African American immigrant women in Philadelphia: Structural and cultural barriers to care. AIDS Care, 17, 1030-1043. doi:10.1080/09540120500100890 [46] Organista, P.B., Organista, K.C. and Solof, P.R. (1998) Exploring AIDS related knowledge, attitudes, and behav- iors of female Mexican migrant workers. Health and So- cial Wo rk, 23, 96-103. doi:10.1093/hsw/23.2.96 [47] Laverentz, M.L., Cox, C.C. and Jordan, M. (1991) The Nuer education program: Breaking down cultural barriers. Health Care for Women International, 20, 1-6. [48] Worth H., Denholm N. and Bannister J. (2003) HIV/ AIDS and the African refugee education program in New Zealand. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 346-356. doi:10.1521/aeap.15.5.346.23819 [49] Ebrahim, S.E., Anderson, J.E., Weidle, P. and Purcell, D.W. (2004) Race/ethnic disparities in HIV testing and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Feresu, L. Smith / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 84-9 8 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS 98 knowledge about treatment for HIV/AIDS: United States, 2001. AIDS Patient Care and STD’s, 18, 27-33. [50] Lawrence, J and Kearns, R. (2005) Exploring the fit be- tween people and providers: Refugee health needs and health care services in Mt. Roskill, Auckland, New Zea- land. Health and Social Care in the Community, 13, 451- 461. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00572.x [51] Elfadil Wafaa (2005) WFP Sudan gender national office. Sudan gender profile. Available at: Foley, E.E. HIV/AIDS and African American immigrant women in Philadelphia: Structural and cultural barriers to care. AIDS Care, 17, 1030-1043. doi:10.1080/09540120500100890 [52] Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (2007) Refugee resettlement program funding. http://dhhs.ne.gov/children_family_services/Pages/refuge es_funding.aspx [53] Kalichman, S.C., Simbayi, L.C., Kagee, A., Toefy, Y., Jooste, S., Cain, D. and Cherry, C. (2006) Associations of poverty, substance use and HIV transmission risk behav- iors in three South African communities. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 1641-1649. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.021 [54] Mabunda, G. (2004) HIV knowledge and practices among rural South Africans. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36, 300-304. d oi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04055.x [55] Wagner, D., Coordinated by The United Nations Educa- tional Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Literacy and adu lt e duc ation. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001233/123333e. pdf [56] Shedlin M.G., Decena C.U. and Olivier-Velez D. (2005) Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97, 32S-37S. [57] Library of Congress (2004) Federal research division country profile: Sudan. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Sudan.pdf [58] Hargreaves, J.R. and Glynn, J.R. (2002) Educational at- tainment and HIV 1 infection in developing countries: A systematic review. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 7, 499-498. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00889.x [59] Hargreaves, J.R., Bonell, C.P., Boler, T., Boccia, D., Bird- thistle, I., Fletcher, A., et al. (2008) Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educa- tional attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub- Saha- ran Africa. AIDS, 22, 403-414. [60] UNAIDS (2000) The relationship between sexual behav- iour and level of education in developing countries (UN- AIDS—Best practice digest, 3 Pages. http://www.greenstone.org/greenstone3/nzdl;jsessionid=2 0143F6FE9D4BE45751F5675DD988BEA?a=dandd=HA SH010746d58add0714a1d98354andc=unaidsandsib=and ed=1andp.s=ClassifierBrowseandp.sa=andp.a=bandp.c=u naids [61] Michelo, C., Sandøy, I.F., and Fylkesnes, K. (2006) Marked HIV prevalence declines in higher educated young people: Evidence from population-based surveys (1995-2003) in Zambia. AIDS, 20, 1031-1038. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000222076.91114.95 [62] Mmbaga, E.J., Leyna, G.H., Mnyika, S.K., Hussain, A. and Klepp, K. (2007) Education attainment and the risk of HIV-1 Infections in Rural Kilimanjaro Region of Tan- zania, 1991-2005: A reversed association. Sexually Trans- mitted Diseases, 34, 1-7. [63] Bloom, S.S., Banda, C., Songolo, G., Mulendema, S., Cunningham, A. and Boerma, J.T. (2000) Looking for change in response to the AIDS epidemic: Trends in AIDS knowledge and sexual behavior in Zambia, 1990 through 1998. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromesd, 25, 77-85. doi:10.1097/00126334-200009010-00011 [64] Yazdi, C.A., et al. (2006) Knowledge, attitudes and sources of information regarding HIV/AIDS in Iranian adolescents. AIDS Care, 18, 1004-1010. doi:10.1080/09540120500526284 [65] Hesketh, T., Duo, L. and Tomkins, A.M. (2005) Attitudes to HIV and HIV testing in high prevalence areas of China: Informing the introduction of voluntary counseling and testing procedures. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81, 108-112. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.009704 [66] Lugalla, J., Emmelin, M., Mutembei, A., Sima, M., Kwe- sigabo, G., Killewo, J. and Dahlgren, L. (2004) Social, cultural and sexual behavioral determinants of observed decline in HIV infection trends: Lessons from the Kagera region, Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 185- 198. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.033 [67] Cleland, J. and Ali, M.M. (2006) Sexual abstinence, con- traception, and condom use by young African women: A secondary analysis of survey data. Lancet, 368, 1788- 1783. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69738-9 [68] Gausset, Q. (2001) AIDS and Cultural practices in Africa: The case of the Tonga (Zambia). Social Science and Medicine, 52, 509-518. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00156-8

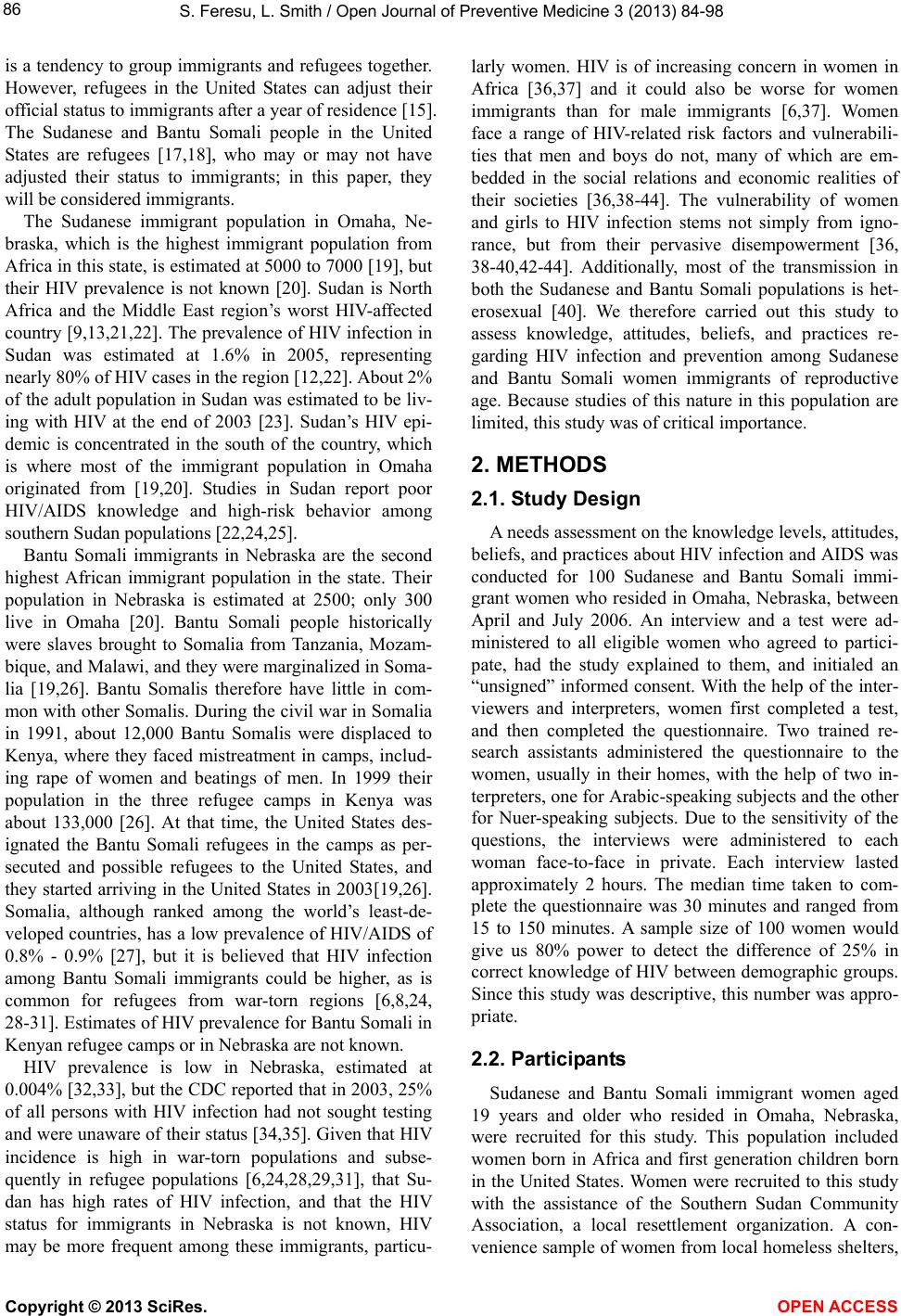

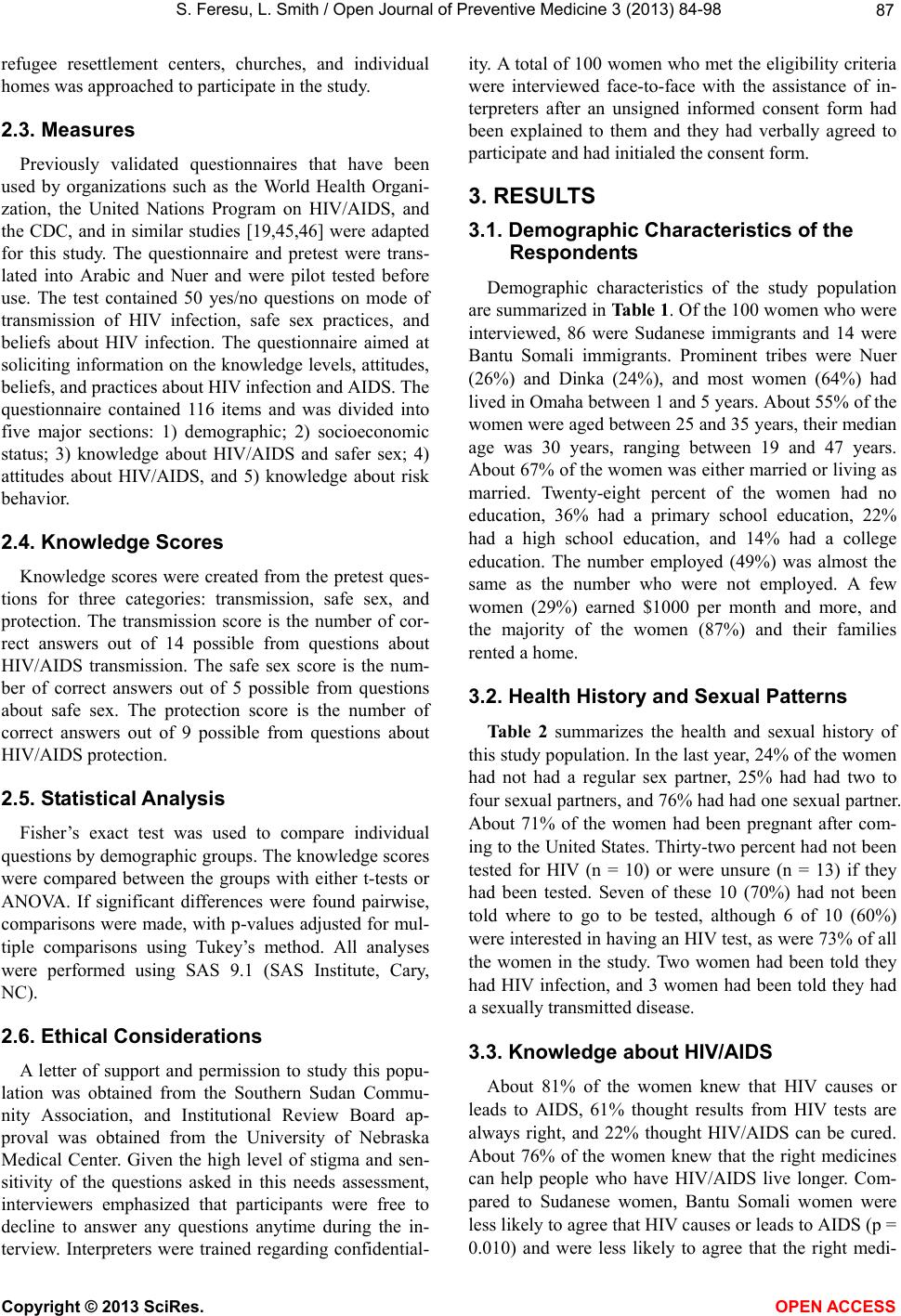

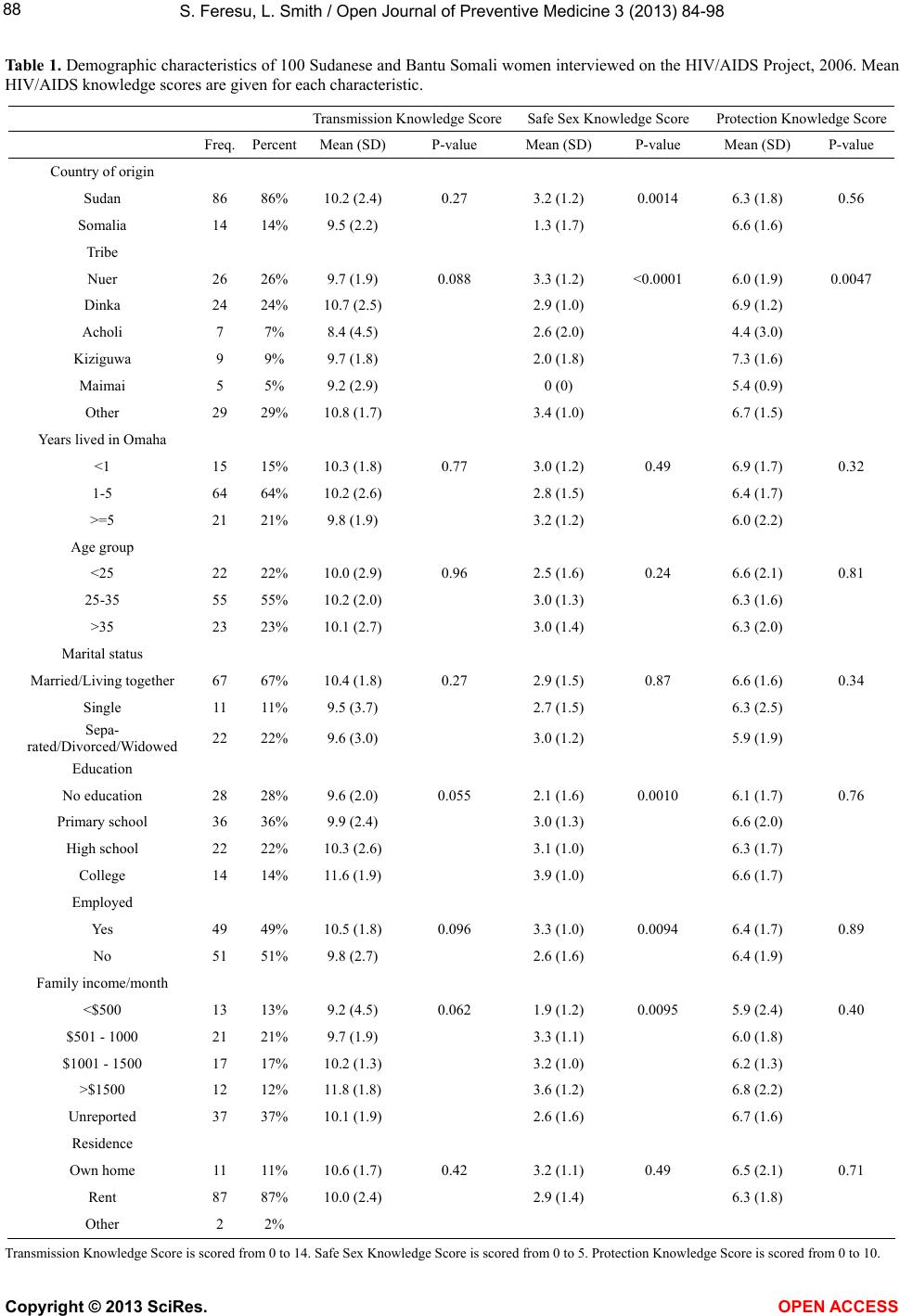

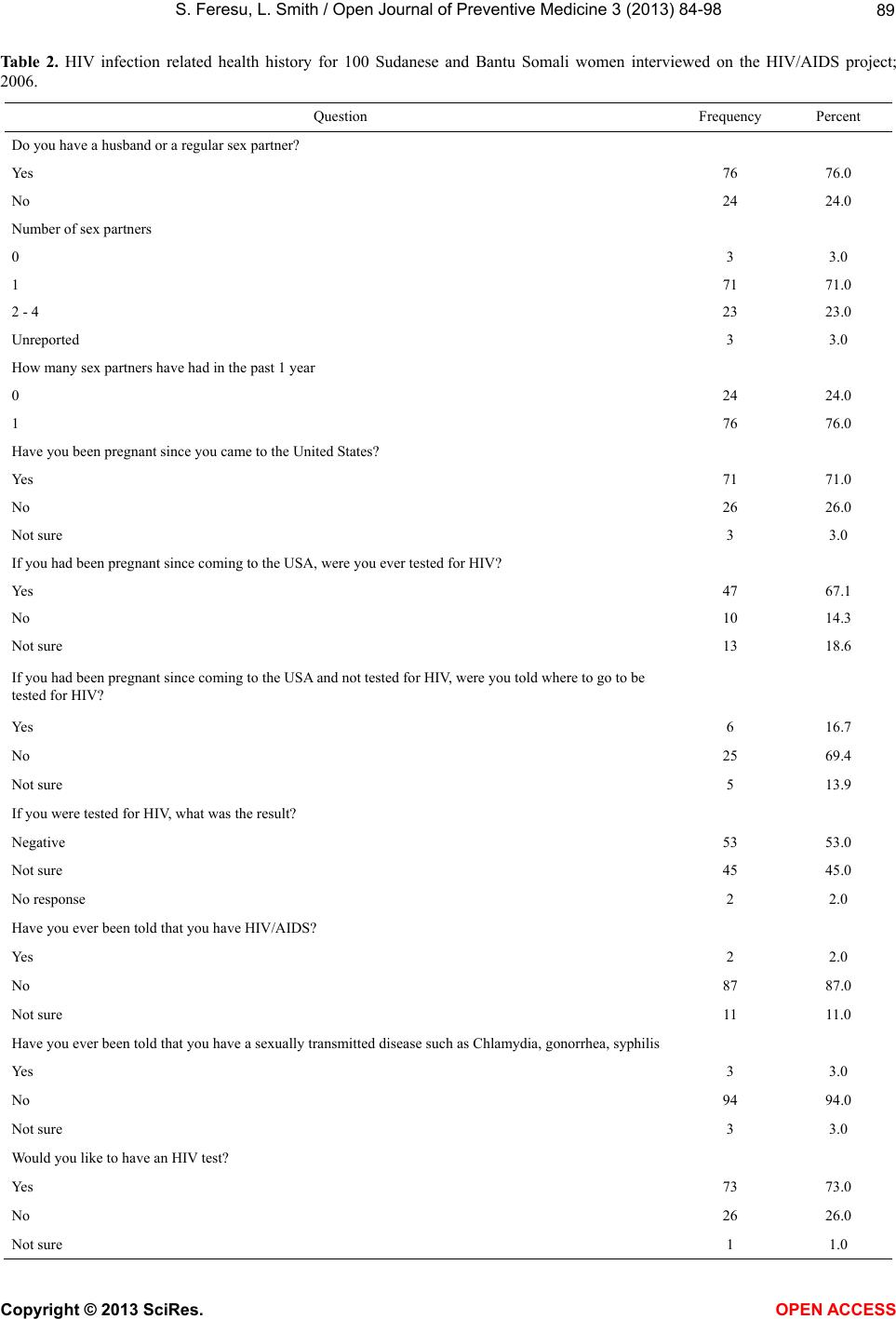

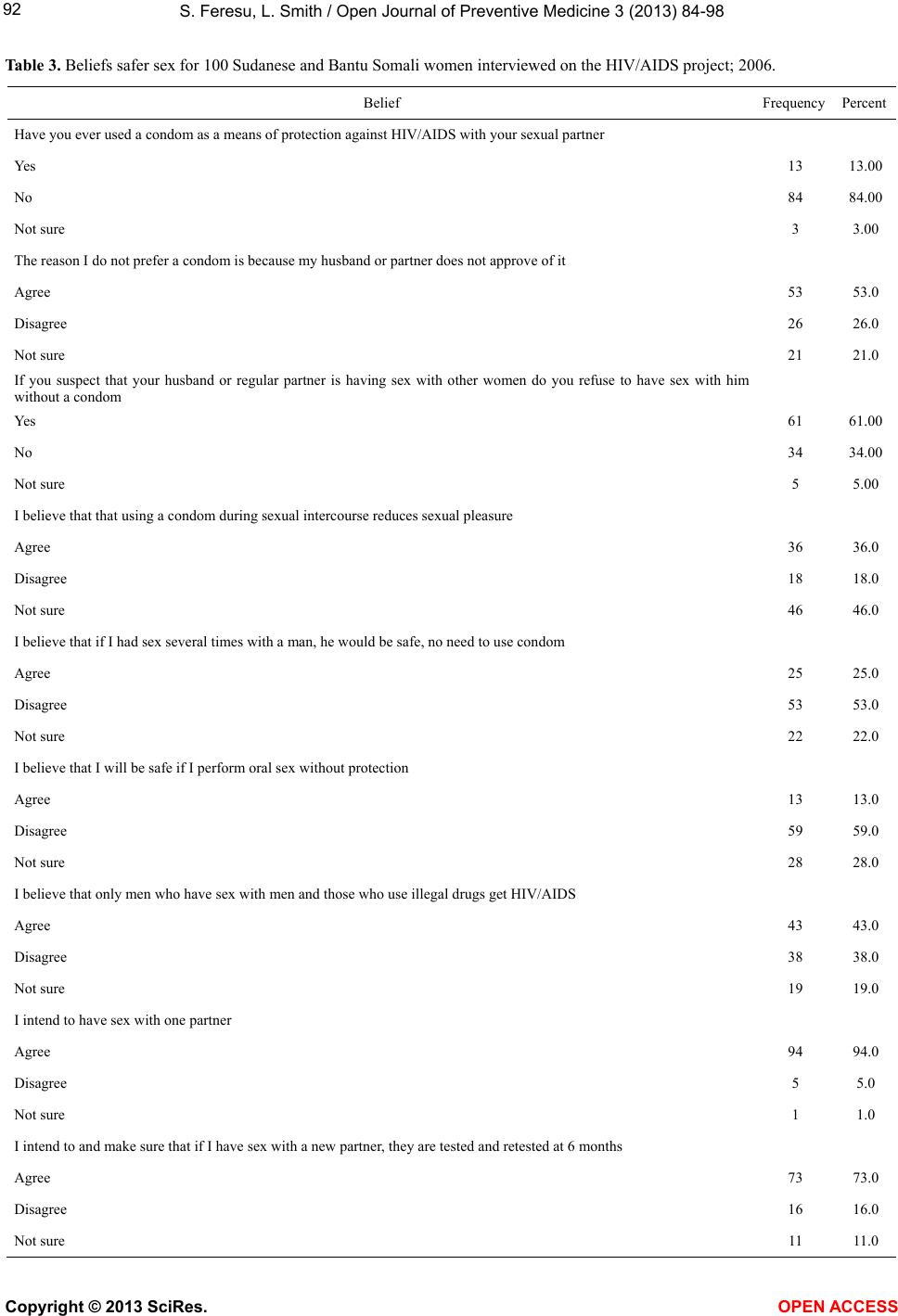

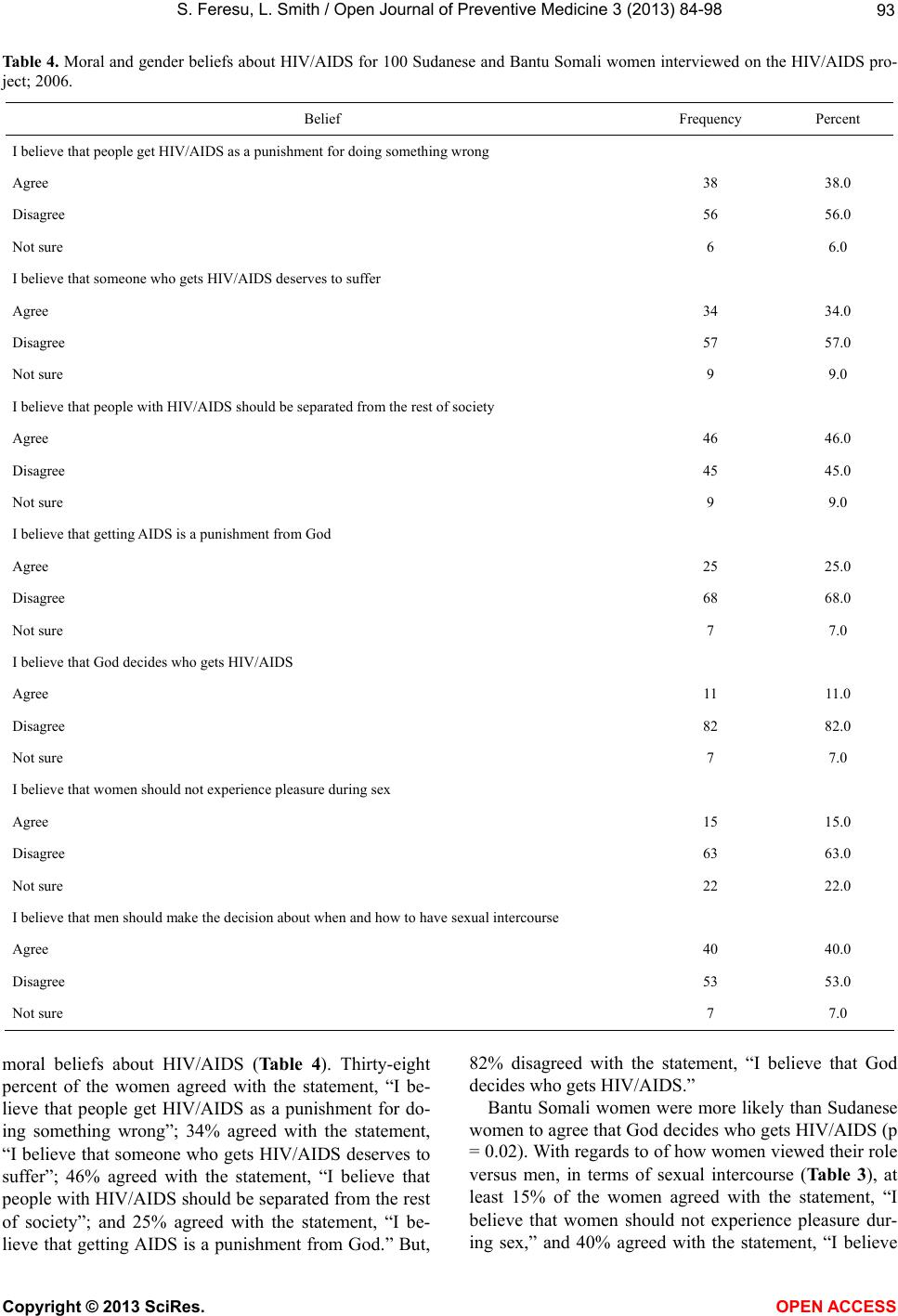

|