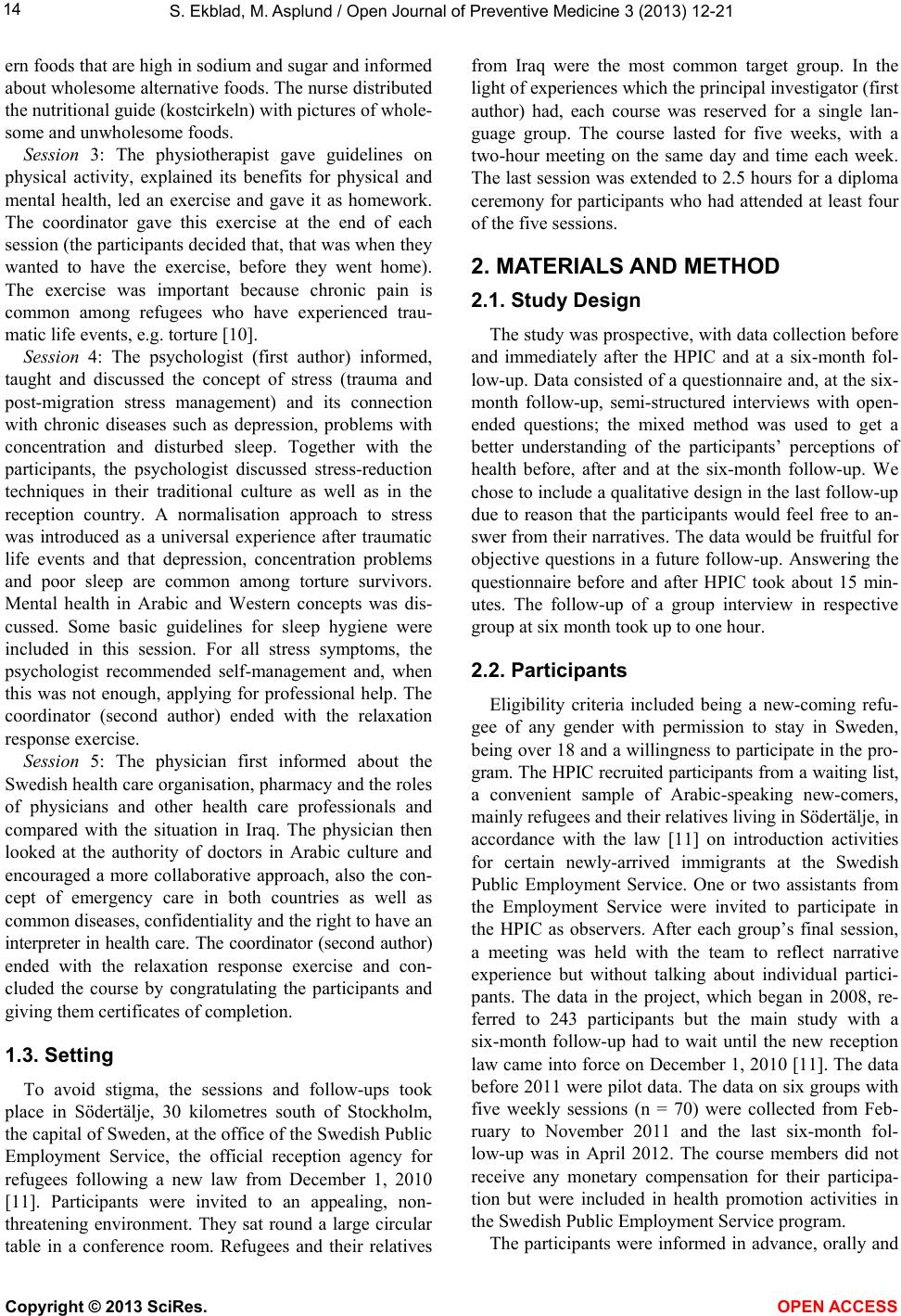

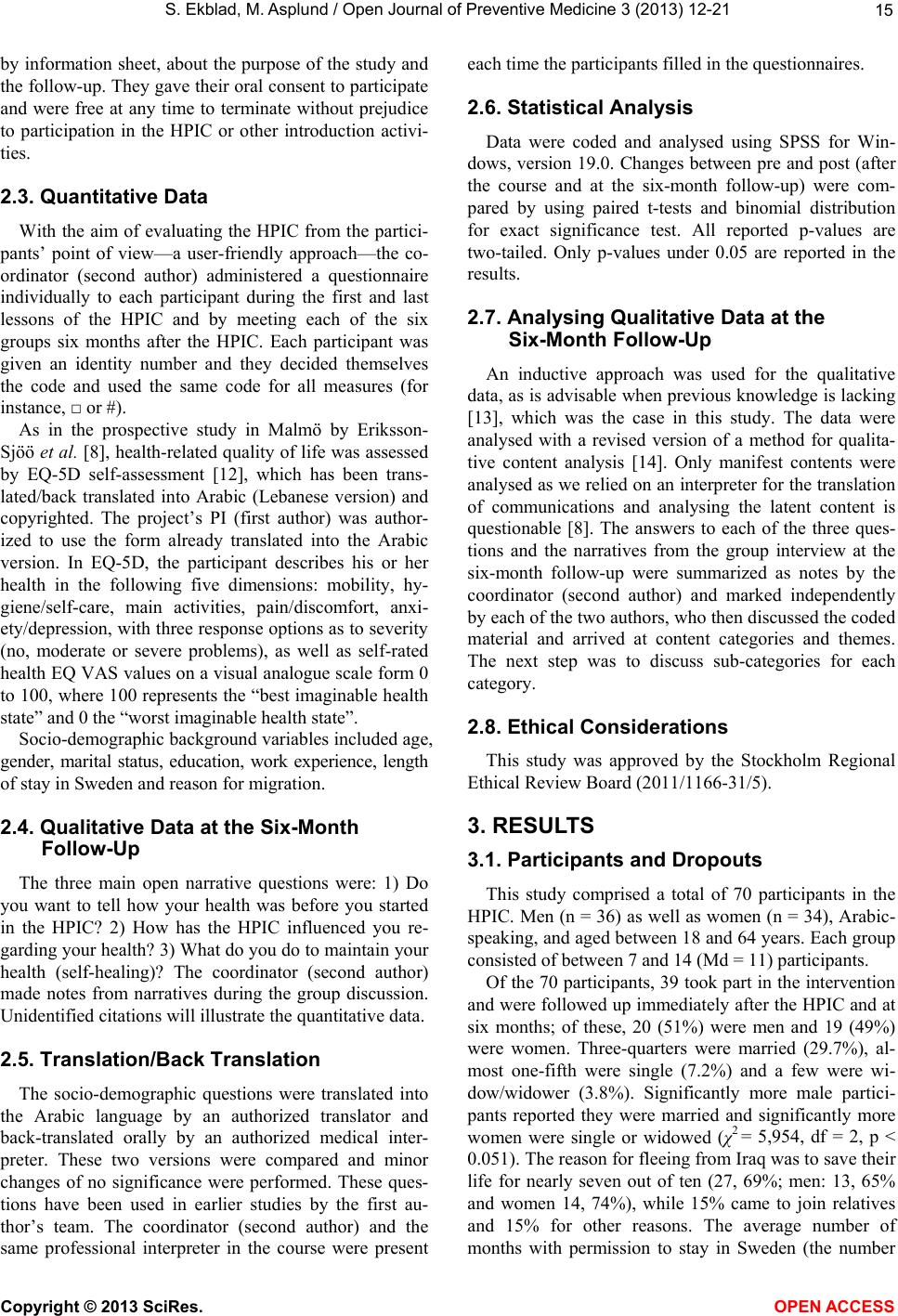

Vol.3, No.1, 12-21 (2013) Open Journal of Preventive Medicine http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2013.31002 Culture- and evidence-based health promotion group education perceived by new-coming a dult Arabic-speaking male and female refugees to Sweden—Pre and two post assessments* Solvig Ekblad#, Maria Asplund Cultural Medicine Unit, Department of Learning Informatics, Management and Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; #Corresponding Author: Solvig.Ekblad@ki.se Received 20 August 2012; revised 23 September 2012; accepted 30 September 2012 ABSTRACT Objective: According to a theoretical approach, events that elicit stress after arrival in the re- ception country, i.e., post-migration stress, have a negativ e impact on health-relate d quali ty o f life among newly-arrived refugees. With the aim of paying attention to such symptoms, a revised culturally-tailored clinical health promotion model developed at Harvard Program in Refugee Trau- ma was used for invited groups of new-coming adult refugees in a town south of the Swedish capital. Methods: A coordinator administered the five-weekly sessions, 2 hours/week, with a professional interpreter. It covered major topics from Western and Arabic worldviews: 1) intro- duction; 2) health care: organisation and access to; 3) exercises; 4) stress management and coping, 5) medical doctor-patient communica- tion. Each topic was led by a nurse, a physio- therapist, a psychologist and a physician with experience of encounters with this target group in health care. Data cover results from 70 par- ticipants attending six groups; 39 participants with pre-course findings and, post-course and six-month follow-ups. There were no significant differences in background factors between the participants and the drop-outs. Results: Partici- pants’ perceptions of their health, measured by EQ-5D, changed positively over time, above all immediately after the course, with no significant differences between the two follow-ups. In the follow-ups, female participants perceived their health as significantly worse than males. Quali- tative data at the six-month follow-up assessed the course as useful but expressed a wish to continue a similar course with a focus on post- migration stress. Conclusion: The results sup- port earlier findings. A course, administered to a small group in a dialogue setting, has value for the participants’ empowerment and perception of health. It is recommended that reception be more adapted to coping of pos t-migration stress of new-coming refugees. Practical Implications: The results have implications for education in clinical health promotion, intercultural commu- nication and inter-professional collaboration in refugee reception. Keywords: Health Promotion; Refugees; Arabic-Speaking; Health-Related Qu ality of Life 1. INTRODUCTION A systematic review shows that compared with age- matched general populations in Western countries, refu- gees could be around ten times more likely to have Post- traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which is the most common form of mental illness among refugees [1]. The second most common is mood disorders [2]. There is co-morbidity between these two disorders [3] and a dose-effect relationship, i.e., increasing levels of trauma lead to higher rates of the symptoms. A study by Kinzie et al. [4] shows that PTSD increases the risk of public health diseases, e.g., hypertension, cardiovascular dis- ease and diabetes, diseases that may be prevented or ameliorated through education and advice. According to a theoretical approach by Silove [5], events that elicit stress after arrival in the reception country, i.e., post- migration stress, have a negative impact on health-re- lated quality of life (HRQoL) among newly-arrived re- fugees [6]. To promote self-care and a proper use of the health care system by new-coming refugees in the recep- *Competing interests: the authors have no competing interests. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 13 tion country, culturally tailored evidence-based knowl- edge of clinical health promotion and communication in health care and other educational information on health issues are of significance not only for the individual and relatives but also for health care and society as a whole. This project adapted the model which the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma (HPRT) (www.hprt-cambridge.org) had used since 2000 for Cambodian survivors of torture, in the form of a Health Promotion Program with a 5-session group format [7]. The Swedish reception system and the Health Promotion Intervention Course (HPIC), its contents and structure have been described in detail elsewhere [8]. In this article we use HPRT’s definition of health, which perceives health as an active, dynamic process where the members of the target group are the key agents in encouraging self-healing [9, cited in 7]: “Health is a personal and social state of balance and well-being in which people feel strong, active, wise and worthwhile; where their diverse capacities and rhythms are valued; where they may decide and choose, express themselves, and move about freely” (p. 5). With this theoretical approach, it is natural to use a curriculum during the first session of the course to pene- trate the participants’ potential personalized power to themselves, prevent illness and promote health in the short and longer run. Further, the health promotion ap- proach is an active approach, in which the participants can have a dialogue with the multidisciplinary team, i.e., ask questions about healthy living and their own deci- sions concerning their individual targets for a healthy lifestyle. In addition, the group dynamic generates peer recommendations, which may be more influential than individual sharing. During the health promotion course, the multidiscipli- nary team is sensitive and adapts the curriculum’s peda- gogical technique to the Arabic-speaking participants. Each of the five sessions with 10 - 14 male and female participants was coordinated by a Swedish registered nurse (second author) and health practitioners (a physio- therapist and a psychologist, both ethnic Swedes, and a medical doctor born in an Arabic country who speaks Swedish during the course), with the same interpreter. The team aimed to integrate the participants’ health con- cepts and knowledge about a healthy life style with evi- dence-based health data and encouraged them to absorb the information and the active approach to their personal health and well-being. According to the health promotion groups, the plans for the lesson were developed and designed to be few and simple; the two hours were divided into one for in- formation, followed by a short coffee-break and fruits, free of charge, and one for dialogue about whether the content was personally relevant and culturally meaning- ful for the participants. In addition, a copy of the power- point presentations with illustrations and other material was given to each participant as a hand-out. It was im- portant to have not just text but also illustrations as some participants may have a low educational background and a history of trauma that makes it difficult to concentrate. The material was in Swedish, which provided an oppor- tunity to learn practical Swedish about health issues. During the session, humour and the ability to laugh were an advantage; clinical experience has shown that healing is promoted by stimulating positive physiological and immune responses. 1.1. Aim and Research Questions This study aimed to assess self-perceived health-re- lated quality of life among newly-arrived adult Arabic- speaking refugees, before and after they participated in a HPIC [7,8]. As in the earlier studies, we were interested in how participants perceived their health before and after participating in HPIC. The research questions were: How do HPIC partici- pants assess their health before and after HPIC and at a 6-month follow-up? How do the participants describe their experiences of participating in HPIC? 1.2. Curriculum The approach focused on the following key health promoting behaviours, which according to the literature [1,8] prevent post-migration stress symptoms among new-coming refugees: nutrition, physical activity, stress and coping, and doctor-patient communication. Session 1: the coordinator (second author) introduced the five-session course by taking up the concepts of health promotion and disease prevention by informing about risk and protective factors for specific illnesses. The coordinator encouraged the participants to have dia- logue from their own healing perspectives and Arabic cultural and spiritual history and informed and explained the structure of the course, its expected benefits and what the interdisciplinary team expected of the participants. It was important to create a neutral atmosphere in which participants could feel comfortable about asking ques- tions and sharing old and new experiences right from the first session. Session 2: The nurse (second author) introduced ac- cess to and the organisation of health care, as well as basic principles of nutrition and their connection to dis- ease prevention. These guidelines were explained in the context of Arabic cuisine. For example, when teaching about sodium reduction for blood pressure control and sugar reduction for weight loss, the team recommended limiting the consumption of traditional Arabic and West- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 14 ern foods that are high in sodium and sugar and informed about wholesome alternative foods. The nurse distributed the nutritional guide (kostcirkeln) with pictures of whole- some and unwholesome foods. Session 3: The physiotherapist gave guidelines on physical activity, explained its benefits for physical and mental health, led an exercise and gave it as homework. The coordinator gave this exercise at the end of each session (the participants decided that, that was when they wanted to have the exercise, before they went home). The exercise was important because chronic pain is common among refugees who have experienced trau- matic life events, e.g. torture [10]. Session 4: The psychologist (first author) informed, taught and discussed the concept of stress (trauma and post-migration stress management) and its connection with chronic diseases such as depression, problems with concentration and disturbed sleep. Together with the participants, the psychologist discussed stress-reduction techniques in their traditional culture as well as in the reception country. A normalisation approach to stress was introduced as a universal experience after traumatic life events and that depression, concentration problems and poor sleep are common among torture survivors. Mental health in Arabic and Western concepts was dis- cussed. Some basic guidelines for sleep hygiene were included in this session. For all stress symptoms, the psychologist recommended self-management and, when this was not enough, applying for professional help. The coordinator (second author) ended with the relaxation response exercise. Session 5: The physician first informed about the Swedish health care organisation, pharmacy and the roles of physicians and other health care professionals and compared with the situation in Iraq. The physician then looked at the authority of doctors in Arabic culture and encouraged a more collaborative approach, also the con- cept of emergency care in both countries as well as common diseases, confidentiality and the right to have an interpreter in health care. The coordinator (second author) ended with the relaxation response exercise and con- cluded the course by congratulating the participants and giving them certificates of completion. 1.3. Setting To avoid stigma, the sessions and follow-ups took place in Södertälje, 30 kilometres south of Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, at the office of the Swedish Public Employment Service, the official reception agency for refugees following a new law from December 1, 2010 [11]. Participants were invited to an appealing, non- threatening environment. They sat round a large circular table in a conference room. Refugees and their relatives from Iraq were the most common target group. In the light of experiences which the principal investigator (first author) had, each course was reserved for a single lan- guage group. The course lasted for five weeks, with a two-hour meeting on the same day and time each week. The last session was extended to 2.5 hours for a diploma ceremony for participants who had attended at least four of the five sessions. 2. MATERIALS AND METHOD 2.1. Study Design The study was prospective, with data collection before and immediately after the HPIC and at a six-month fol- low-up. Data consisted of a questionnaire and, at the six- month follow-up, semi-structured interviews with open- ended questions; the mixed method was used to get a better understanding of the participants’ perceptions of health before, after and at the six-month follow-up. We chose to include a qualitative design in the last follow-up due to reason that the participants would feel free to an- swer from their narratives. The data would be fruitful for objective questions in a future follow-up. Answering the questionnaire before and after HPIC took about 15 min- utes. The follow-up of a group interview in respective group at six month took up to one hour. 2.2. Participants Eligibility criteria included being a new-coming refu- gee of any gender with permission to stay in Sweden, being over 18 and a willingness to participate in the pro- gram. The HPIC recruited participants from a waiting list, a convenient sample of Arabic-speaking new-comers, mainly refugees and their relatives living in Södertälje, in accordance with the law [11] on introduction activities for certain newly-arrived immigrants at the Swedish Public Employment Service. One or two assistants from the Employment Service were invited to participate in the HPIC as observers. After each group’s final session, a meeting was held with the team to reflect narrative experience but without talking about individual partici- pants. The data in the project, which began in 2008, re- ferred to 243 participants but the main study with a six-month follow-up had to wait until the new reception law came into force on December 1, 2010 [11]. The data before 2011 were pilot data. The data on six groups with five weekly sessions (n = 70) were collected from Feb- ruary to November 2011 and the last six-month fol- low-up was in April 2012. The course members did not receive any monetary compensation for their participa- tion but were included in health promotion activities in the Swedish Public Employment Service program. The participants were informed in advance, orally and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 15 by information sheet, about the purpose of the study and the follow-up. They gave their oral consent to participate and were free at any time to terminate without prejudice to participation in the HPIC or other introduction activi- ties. 2.3. Quantitative Data With the aim of evaluating the HPIC from the partici- pants’ point of view—a user-friendly approach—the co- ordinator (second author) administered a questionnaire individually to each participant during the first and last lessons of the HPIC and by meeting each of the six groups six months after the HPIC. Each participant was given an identity number and they decided themselves the code and used the same code for all measures (for instance, □ or #). As in the prospective study in Malmö by Eriksson- Sjöö et al. [8], health-related quality of life was assessed by EQ-5D self-assessment [12], which has been trans- lated/back translated into Arabic (Lebanese version) and copyrighted. The project’s PI (first author) was author- ized to use the form already translated into the Arabic version. In EQ-5D, the participant describes his or her health in the following five dimensions: mobility, hy- giene/self-care, main activities, pain/discomfort, anxi- ety/depression, with three response options as to severity (no, moderate or severe problems), as well as self-rated health EQ VAS values on a visual analogue scale form 0 to 100, where 100 represents the “best imaginable health state” and 0 the “worst imaginable health state”. Socio-demographic background variables included age, gender, marital status, education, work experience, length of stay in Sweden and reason for migration. 2.4. Qualitative Data at the Six-Month Follow-Up The three main open narrative questions were: 1) Do you want to tell how your health was before you started in the HPIC? 2) How has the HPIC influenced you re- garding your health? 3) What do you do to maintain your health (self-healing)? The coordinator (second author) made notes from narratives during the group discussion. Unidentified citations will illustrate the quantitative data. 2.5. Translation/Back Translation The socio-demographic questions were translated into the Arabic language by an authorized translator and back-translated orally by an authorized medical inter- preter. These two versions were compared and minor changes of no significance were performed. These ques- tions have been used in earlier studies by the first au- thor’s team. The coordinator (second author) and the same professional interpreter in the course were present each time the participants filled in the questionnaires. 2.6. Statistical Analysis Data were coded and analysed using SPSS for Win- dows, version 19.0. Changes between pre and post (after the course and at the six-month follow-up) were com- pared by using paired t-tests and binomial distribution for exact significance test. All reported p-values are two-tailed. Only p-values under 0.05 are reported in the results. 2.7. Analysing Qualitative Data at the Six-Month Follow-Up An inductive approach was used for the qualitative data, as is advisable when previous knowledge is lacking [13], which was the case in this study. The data were analysed with a revised version of a method for qualita- tive content analysis [14]. Only manifest contents were analysed as we relied on an interpreter for the translation of communications and analysing the latent content is questionable [8]. The answers to each of the three ques- tions and the narratives from the group interview at the six-month follow-up were summarized as notes by the coordinator (second author) and marked independently by each of the two authors, who then discussed the coded material and arrived at content categories and themes. The next step was to discuss sub-categories for each category. 2.8. Ethical Considerations This study was approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethical Review Board (2011/1166-31/5). 3. RESULTS 3.1. Participants and Dropouts This study comprised a total of 70 participants in the HPIC. Men (n = 36) as well as women (n = 34), Arabic- speaking, and aged between 18 and 64 years. Each group consisted of between 7 and 14 (Md = 11) participants. Of the 70 participants, 39 took part in the intervention and were followed up immediately after the HPIC and at six months; of these, 20 (51%) were men and 19 (49%) were women. Three-quarters were married (29.7%), al- most one-fifth were single (7.2%) and a few were wi- dow/widower (3.8%). Significantly more male partici- pants reported they were married and significantly more women were single or widowed (χ2 = 5,954, df = 2, p < 0.051). The reason for fleeing from Iraq was to save their life for nearly seven out of ten (27, 69%; men: 13, 65% and women 14, 74%), while 15% came to join relatives and 15% for other reasons. The average number of months with permission to stay in Sweden (the number Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS 16 of months as asylum seekers were not collected) was 5 (range 1 - 34; male participants: 5, range 1 - 34; female participants 4.5, range 1 - 13). The overall mean age was 41 years (range 20 - 61 years); the male participants were slightly older on aver- age than the female participants (44 and 39 years, re- spectively). A majority of the participants stated that they had children. The overall median number of children was 2 (range 0 - 8); male participants had more children than female participants (3, range 0 - 5, and 1.5, range 0 - 8). The overall average number of years in school was 11 (range 2 - 18). Male participants had on average rather more years in school than female participants (12, range 2 - 18 years, and 10, range 5 - 18). The average number of years in the work force was 11 (range 0 - 32). Male participants (mean 17, range 0 - 32) had significantly more years in the work force than fe- male participants (mean 6, range 0 - 32), (t = 3.344, df = 36, p < 0.002). Six of the 70 participants were drop-outs at the end of the course and a total of 31 (44.3%) were drop-outs at the six-month follow-up (Table 1). The drop-outs oc- curred due to difficulties in contacting participants. They moved due to dwelling difficulties, to other cities and other unknown reasons. There were no significant dif- ferences in background factors between the participants and the drop-outs. 3.2. Assessment of Perceived Health by EQ-5D 3.2.1. At Baseline In the EQ-5D questionnaire at the start of the course (Table 2) the participants reported the following health problems, with no significant differences between male and female participants: Movement: Four out of ten (42%) perceived that they moved without any difficulty, six out of ten (58%) with some difficulty. Hygiene: The majority had no problem with hygiene (84%), the rest (16%) had some problems. Activities: Almost six out of ten (58%) perceived that they could do their activities without any problems, 37% had some problems and 5% could not do their ac- tivities. Pain: About one in ten (13%) perceived no pain, nearly two-thirds (66%) felt some pain and one-fifth (21%) had severe pain. Depression: Almost a quarter (23%) felt no problems, over half had some problems and 15% had severe de- pression. 3.2.2. Changes from before to after the Cour se The EQ-5D total scores (Table 2) for “No problems” improved in trends as regards mobility, hygiene, pain and depression and deteriorated slightly for activities but with no significant differences. 3.2.3. Change s f rom Baselin e t o after the C o urse and the Six-Month Follow-Up The scores for all participants (Table 2) show that for mobility the proportion with no problems increased to 54% at the six-month follow-up. For hygiene and de- pression the proportion had improved at the end of the course but decreased six months later. For pain, the pro- portion with no problems had also improved at the end of the course but deteriorated to the baseline level six months later. For activities, the proportion with no prob- lems decreased continuously from baseline to the six- month follow-up. Table 1. Socio-demographic data on participants and drop-outs: mean age, number of children, years in school and in work, months in Sweden. Total (n = 39) Male (n = 20) Female (n = 19) Drop-outs Total (n = 31) Mean age (sd) 41.46 (11.357) 44.05 (2.566) 38.74 (2.492) 37.77 (10.497) Min-max 20 - 61 20 - 61 20 - 56 21 - 56 Number of children, Md) 2 3 1.5 1 Min-max 0 - 8 0 - 5 0 - 8 0 - 7 Mean years (sd) in school 10.82 (4.046) 11.55 (4.322) 10.00 (3.662) 11.55 (4.545) Min-max 2 - 18 2 - 18 5 - 18 0 - 19 Mean years (sd) in work before arrival 11.34 (11.560) 16.89 (9.933) 5.79 (10.533) 7.60 (9.796) Min-max 0 - 32 0 - 32 0 - 32 0 - 20 Mean months (sd) in Sweden with permission 4.74 (5.510) 4.95 (1.678) 4.53 (0.681) 6.43 (9.712) Min-max 1 - 34 1 - 34 1 - 13 1 - 40  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 17 Table 2. EQ-5D at baseline, after the course and at six-month follow-up. (n = 39) Baseline N (%) After the course N (%) Six-month follow-up 2 N (%) EQ-5D Total 39 Men (n = 20) Women (n = 19) Total 39 Men (n = 20) Women (n = 19) Total 39 Men (n = 20) Women (n = 19) Mobility No problems Some problems Large problem 16 (42%) 22 (58%) - 9 (47%) 10 (53%) - 7 (37%) 12 (63%) - 19 (50%) 19 (50%) - 10 (53%) 9 (47%) - 9 (47%) 10 (53%) - 21 (54%) 18 (46%) - 11 (55%) 9 (45%) - 10 (53%) 9 (47%) - Hygiene No problems Some problems Large problem 31 (84%) 6 (16%) - 16 (84%) 3 (16%) - 15 (83%) 3 (17%) - 33 (92%) 3 (8%) - 18 (95%) 1 (5%) - 15 (88%) 2 (12%) - 33 (89%) 3 (8%) 1 (3%) 17 (94%) 1 (6%) - 16 (84%) 2 (11%) 1 (5%) Activities No problems Some problems Large problem 22 (58%) 14 (37%) 2 (5%) 12 (60%) 7 (35%) 1 (5%) 10 (56%) 7 (39%) 1 (6%) 20 (55%) 15 (42%) 1 (3%) 14 (74%) 4 (21%) 1 (5%) 6 (35%) 11 (65%) - 17 (44%) 21 (54%) 1 (3%) 10 (50%) 9 (45%) 1 (5%) 7 (37%) 12 (63%) - Pain No problems Some problems Large problem 5 (13%) 25 (66%) 8 (21%) 2 (11%) 12 (63%) 5 (26%) 3 (16%) 13 (68%) 3 (16%) 7 (19%) 25 (68%) 5 (13%) 5 (28%) 9 (50%) 4 (22%) 2 (11%) 16 (84%) 1 (5%) 5 (13%) 28 (74%) 5 (13%) 4 (21%) 13 (68%) 2 (11%) 1 (5%) 15 (79%) 3 (16%) Depression No problems Some problems Large problem 9 (23%) 24 (62%) 6 (15%) 5 (25%) 12 (60%) 3 (15%) 4 (21%) 12 (63%) 3 (16%) 16 (43%) 16 (43%) 5 (14%) 10 (55%) 5 (28%) 3 (17%) 6 (32%) 11 (58%) 2 (10%) 12 (32%) 22 (58%) 4 (10%) 9 (47%) 7 (37%) 3 (16%) 3 (16%) 15 (79%) 1 (5%) As shown in Table 3, on the health rating scale (0 - 100), which reflects the self-perceived health state, the participants’ mean scores improved from baseline to the end of the course but deteriorated slightly at the six- month follow-up. There were no significant differences. 3.2.4. Gender Differences At the end of the course, female participants had sig- nificantly more problems with activities than male par- ticipants (χ2 = 7.378, df = 2, p < 0.025). At the six-month follow-up, some problems with depression were twice as common among female participants compared with male participants, a difference that is significant (χ2 = 6.909, df = 2, p < 0.032). The health rating scale showed higher mean values for male participants after the course as well as at the six-month follow-up but for female participants the mean values had increased after the course but fell back close to baseline at the six-month follow-up. There were no significant differences. 3.3. Qualitative Findings at the Six-Month Follow-Up According to Table 4, there was one general theme: The group participants had different backgrounds and needs but answered that the dialogue had given them valuable general health information, though they wanted to continue with future focused courses. This theme as- sesses three categories: before the course, impact of the course and future stress management and coping. These categories have 10 sub-categories. Before the course: as new-comers to Sweden, some participants had been separated from family members and had poor bad housing. They felt that access to health care was very difficult and found it hard to understand the health system. Opinions differed as to when they wanted to have this health information; some preferred early, others later but the majority wanted to have two-hour meetings in the group for a longer period and to learn more from clinical health professionals and sup- port each other as new-comers. During the six months after the course they felt there had been few improve- ments in the reception program and they also wanted more opportunities to talk Swedish. One of the coordi- nators (second author) considered that the participants had forgotten the Arabic version of “Vårdguiden” on the web with information about access to health care. At the six-month follow-up, the coordinator brought a plastic body Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 18 Table 3. VAS at baseline, after the course and at six-month follow-up. Baseline mean (sd) (n = 39) After course mean (sd) (n = 39 ) T-test Df P Six-month follow-up mean (sd) (n = 39) T-test Df p Total n = 39 57.21 61.41 −0.905 37 0.371 59.33 −0.347 37 0.730 Male n = 20 60.70 61.90 −0.184 19 0.856 64.70 −0.516 19 0.612 Female n = 19 53.33 60.89 −1.632 17 0.121 53.68 0.252 17 0.804 Table 4. Overview of general theme, three categories and ten sub-categories. General Theme Categories Sub-categories Received valuable general health information in dialogue but wish for more and focused courses Before the course _____________________ Impact of the course _____________________ Future stress management and coping Chaos and insecurity Illness Problems with teeth ____________________ Increased knowledge Increased security Motivation to be active Wish to continue ____________________ Preventive tools Knowledge Empowerment doll and gave a lecture about important organs and their functions. The participants were very excited. Further, not having health information and adequate knowledge about health, some participants felt chaotic with concen- tration problems, others were anxious, mentally tired and insecure or felt illness or pain from unhealthy teeth; at the same time, negative attitudes to medicine for their symptoms were common as the root cause was often existential stress: -Before seven months I did not feel OK and very tired and I had too much thoughts. Impact of the course: The majority of participants mentioned that they felt the course had had a positive impact on their perceived health and that it played a ma- jor role in providing advice to new-coming refugees, how to maintain health and how to use primary health care and mental health staff to solve mental and physical problems. Those who had health care needs had a better understanding of the encounter with health care after the course as they knew more about the system. The peda- gogic and the group setting for men and women together enabled them to share important experiences. As the group content was confidential, they developed trust during the sessions in the group. Several mentioned that they wanted to continue the course to get more relevant information, for instance, separate courses on how to rear children in Sweden, cultural information about Swedish society, information about first aid, self-care (e.g. how to check body temperature, blood pressure and how to use clothes in Sweden), dentist, eye specialist, mental health promotion, mental health treatment, nutrition, tattooing, skin diseases and severe diseases. -We need more knowledge about how to handle chil- dren and how to rear them. Especially, as they are in a society (Swedish) which is quite different from Arabic society. The family needs advice. Future stress and management coping: At the six- month follow-up, several participants mentioned that they continued to use the knowledge and tools from the course for stress management and coping. They felt more empowered when they get knowledge and can handle their health situation in a proper way. They know more about how to get access to health care when needed, they and their family felt more secure. One of the participants mentioned that in the Arabic tradition (as well as in the West) there is a saying that “using preventive methods is much better than receiving treatment.” -Before, I could not walk a long distance. But nowa- days I can walk daily 2.5 and 3 hours. -The information about health has had an impact on me, what I can do to stay healthy and sometimes I do relaxation. -I had elevated cholesterol and fat and used advice and exercise and increased other activities, but not with Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 19 the help of medicine. The nurse has taken new tests which showed reduced cholesterol. I followed a food program (diet circle) and with all this advice I have lost weight. Now I feel active. 4. DISCUSSION 4.1. Discussion of the Results With the aim to assess self-perceived health-related quality of life among newly-arrived Arabic-speaking refugees, before and after they participated in a HPIC, the results show that prior to the course, participants perceived illness and that such a health promotion inter- vention shortly after resettlement for new-coming refu- gees is relevant and useful for stress management, coping, empowerment and to build up trust. The baseline data shows a similar level of “no problems” as in the study with such a course with Arabic-speaking refugees in Malmö, southern Sweden [8], but far more perceived illness compared with responses of newly-arrived Iraqis with residence permits in Sweden, regardless of health problems [15], who responded to the Swedish postal questionnaire. This study and the one in Malmö [8] per- ceived a need for health education but the participants were not identified as patients. In keeping with the lit- erature, the data indicate that our target group needs tai- lor-made and culturally-sensitive mental health promo- tion programs in order to respond to their health needs [8]. Responses of “no problems” to four of the five health state issues (mobility, hygiene, activities, pain and depression) had improved immediately after the course, although the changes are not significant. This indicates that the identification of post-migration stress problems, such as pain, depression and activities should be a part of an early medical examination of newly-arrived refugees [16]. Further, the data shows that female participants perceived significantly worse health than male partici- pants. This finding is supported by Swedish epidemiol- ogical data showing that female refugees are a risk group for mental illness [17]. It is therefore important to ask new-comers about the reason for migration and not mainly about the country they were born in. The results are also in line with Eriksson-Sjöö et al. [8] in Malmö in that a majority of the participants described not only post-migration stress but also a lack of trust in the Swedish health care system because they found it hard to access it. In a meta-analysis study, Porter and Haslam [18] showed a correlation between psychosocial factors and poorer mental illness among asylum seekers and refugees and concluded that prevention of psychoso- cial shortcomings may have a positive influence on refu- gees’ mental health. Psychological acculturation, which may be prevented refers to the dynamics process that the new-coming refugees experience as they adapt to the new reception culture [19]. According to Silove [5], the structure and content of the HPIC have resulted in a sense of security, less stress and improved perceived health. At the same time, the course, with a relatively small and preventive investment, can accomplish quick changes for both the target group and society. However, from a longitudinal phase, the participants showed on the last follow-up after six months that their improvements in EQ-5D decreased (not significant) after the first follow up. It can be interpreted that the post-migration stress influenced them and they needed regular support from a HPIC. These signs showed face validity during the six group interviews as they wanted to continue the course in a group with the focus on special content, they felt engaged and con- firmed. They felt secure in the group and the opportunity to build up a more or less new social network to com- pensate for lost ones was important for being perceived by others. Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg [20] found in a study on male refugees from Iraq that a social network after reception in a host country was central for preven- tion of mental illness. For those who are not working or studying Swedish, for instance, away from home, this social support group, meeting an optimal number during five weeks, may also prevent isolation and marginalisa- tion. The participants’ needs and possibilities for post-mi- gration stress management do not seem to be in line with the new refugee reception law [11]. The results are sup- ported by a Swedish government report about how the authorities have implemented the introduction reform [21]. The report shows, for instance, that “activities are not sufficiently adapted to the target group needs and requirements” (page 8). 4.2. Discussion of the Methods Methodological limitations of this study are the ab- sence of a control group and the selection bias because we could not control who was invited from the Swedish Public Employment Service. However, it seemed that the participants obtained support from the Service’s assis- tants, who became more sensitive to the impact of post- migration stress as they participated as observers in the HPIC. The target group was small and a single language was used. Outside control of the present project, the tar- get group is less settled than the general population, which influenced the high numbers of drop-outs, but the drop-out is in line with other prospective studies [8] and there were no significant differences in background fac- tors between the participants and the drop-outs. Another limitation of the qualitative data is that we communi- cated through a professional interpreter and because of the challenges with translated research data [22] we were unable to analyse latent data. Further, we cannot con- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 20 clude that the changes in perceived health were a result of the HPIC. However, the study has strength in that it is prospective, used an established instrument in Arabic (EQ-5D) and is based on both quantitative and qualita- tive data, partly mixed-method design as qualitative data was only used at the six months’ follow up. The qualita- tive data explored the quantitative data at the six months follow up and showed that having the health promotion course was relevant and user-friendly for the target group, and the narrative interview group data had face validity with the quantitative data. Due to the sixth months’ fol- low up data from the group interviews, in the future some objective questions may be developed regarding future stress management and coping after HPIC. A key unanswered question is whether or not the benefits last for more than 6 months. A related question is what is required to maintain these benefits over time. At the six-month follow-up, the participants mentioned several post-migration stress factors that was beyond their con- trol but had an impact on their perceived health. In gen- eral, altering attitudes is very difficult but information may change a person’s inner welfare, which in a next step, influences that person’s behaviour in a way that improves his or her perceived health and health-related beliefs [23]. 5. CONCLUSION Our findings contribute to the small but growing body of evidence that a relatively short and culturally tailored health promotion education, with clinically interdiscipli- nary health professionals, a coordinator and an inter- preter, strengthens the prerequisites for new-coming re- fugees, who are a risk group for poor health, especially mental, and at risk of marginalisation, to improve their post-migration stress management and coping and pre- vent poor access to health care. Health is a human right and knowledge heightens empowerment. The data are in line with the literature that healthy new-comers will be productive members of the host country. Practical Implications Such a preventive approach should be incorporated in a comprehensive model of community-based health pro- motion and integrated patient-centred primary care. Fur- ther, an interdisciplinary and intercultural approach for collaboration between service reception staff and clinical staff is recommended [24]. These interventions should also be spread to other social and economic disadvan- taged groups at risk of poor health and be accompanied by regular evaluation and quality improvement. Despite the limitations mentioned above, this study provides sufficient evidence to assert that the relatively short health promotion courses for unidentified patients are a promising intervention worthy of further imple- mentation and investigation. However, in order to be- come more efficient, reception staff both with and with- out medical training need to be trained in how to col- laborate in the short and long term in intercultural and interdisciplinary communication. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Professor Richard Mollica, MD, and his team for introducing us to the health promotion course. We also thank physiotherapist Niklas Johnson and Gona Jafaar, MD, for their great contribution as team leaders in the course. The project was financed by a public health budget (Folkhälsoanslaget), Stockholm county council (HSN 0803-0349, 2008-2011). Special thanks to Mr. Patrick Hort for language editing of the text. REFERENCES [1] Fazel, M., Wheeler, J. and Danesh, J. (2005) Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries. A systematic review. Lancet, 365 1309- 1314. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6 [2] Carta, M.G., Bernal, M., Hardoy, M.C. and Haro-Abad, J.M. (2005) Migration and mental health in Europe (the state of the mental health in Europe working group: Ap- pendix 1). Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 1, 1-13. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-1-13 [3] Mollica, RF., Kirschner, K.E. and Ngo-Metzger, Q. (2011) The mental health challenges of immigration. In: Thor- nicroft, G.., Szmukler, G., Mueser, K.T. and Drake, R.E., Eds., Oxford Textbook of Community Mental Health, Ox- ford University Press, Oxford, 95-103. [4] Kinzie, J.D., Riley, D., McFarland, B., Hayes, M., Boehnlein, J., Leung, P. and Adams, G. (2008) High pre- valence rates of diabetes and hypertension among refugee psychiatric patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196, 108-112. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318162aa51 [5] Silove, D. (1999) The psychosocial effects of torture, mass human rights violations and refugee trauma—To- ward an integrated conceptual framework. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 200-207. doi:10.1097/00005053-199904000-00002 [6] Ekblad, S., Abazari, A. and Eriksson, N.-G. (1999) Mi- gration stress-related challenges associated with per- ceived quality of life. A qualitative analysis of Iranian and Swedish patients. Transcultural Psychiatry, 36, 329-345. doi:10.1177/136346159903600307 [7] Berkson, S., Daimyo, S., Lavelle, J., Tor, S. and Mollica, R. (2012) Healing body, mind and spirit. The Impact of Health Promotion and Cambodian Survivors of Torture. Submitted. [8] Eriksson-Sjöö, T., Cederberg, M., Östman, M. and Ekblad, S. (2012) Quality of life and health promotion intervene- tion—A follow up study among newly-arrived Arabic speaking refugees in Malmö, Sweden. International Jour- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS  S. Ekblad, M. Asplund / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 12-21 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCE SS 21 nal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 8, 112-126. [9] Capoor, I. (2001) Power of definition in global health fulbright new century scholars program. 29 October-11 November, Bellagio. [10] Olsen, D.R., Montgomery, E., Carlsson, J. and Foldspang, A. (2006) Prevalent pain and pain level among torture survivors: A follow-up study. Danish Medical Bulletin, 53, 210-214. [11] Lagen om etableringsinsatser för vissa nyanlända in- vandrare. SFS 2010, 197 (In Swedish). [12] EuroQoL Group, Totterdam. http://euroqol.org [13] Elo, S. and Kyngäs, H. (2007) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107- 115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [14] Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research; concepts procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Edu- cation, 2, 105-112. [15] Sundell Lecerof, S. (2010) Olika villkor-olika hälsa. Hälsan bland irakier i åtta av Sveriges län 2008. Malmö Högs- kola, Lunds Universitet, Uppsala Universitet (In Swe- dish). http://www.mah.se/upload/Foroveove, skningscentrum/MIM/MIM/IMHAd%20rapport%20SSL %2010%2002%2005,%202.pdf [16] Socialstyrelsen (2011) Nationella riktlinjer för sjukdoms- förebyggande metoder. Tobaksbruk, riskbruk av alkohol, otillräcklig fysisk aktivitet och ohälsosamma matvanor. Stöd för styrning och ledning (In Swedish). http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2011/2011-11- 11/ [17] Hollander, A-C, Bruce, D., Burström, B. and Ekblad, S. (2011) Gender-related mental health differences between refugees and non-refugee immigrants—A cross-sectional register-based study. BMC Public Health, 24, 180. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/180 [18] Porter, M. and Haslam, N. (2005) Predicplacement and postdiscplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta- analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294, 602-612. doi:10.1001/jama.294.5.602 [19] Berry, J.W. (1980) Acculturation as varieties of adapta- tion. In: Padilla, A., Ed., Acculturation: Theory, Models and Findings, Westview, Boulder, 9-25. [20] Gorst-Unsworth, C. and Goldenberg, E. (1998) Psycho- logical sequelae of torture and organised violence suf- fered by refugees from Iraq. Trauma-related factors com- pared with social factors in exile. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 90-44. [21] Statskontoret (2012) Etableringen av nyanlända. En up- pföljning av myndigheternas genomförande av etablerings- reformen. 2012:22 (In Swedish). [22] Ingvarsdotter, K., Johnsdotter, S. and Östman M. (2010) Lost in interpretation: The use of interpreters in research on mental ill health. International Journal of Social Psy- chiatry, 58, 34-40. http://sagepub.com doi:10.1177/0020764010382693 [23] Tengland, P.-A. (2006) The goals of health work: Quality of life, health and welfare. Medici ne , Health Care and Philosophy, 9, 155-167. doi:10.1007/s11019-005-5642-5 [24] Ekblad, S. and Forsström, D. (2012) Inter-professional and inter-cultural competence training as a preventive strategy to promote collaboration in encountering new- coming refugees in the reception programme—A case study. In: Olisah, V., Ed., Essential Notes in Psychiatry, InTech, Rijeka, 313-332. http://www.intechopen.com/books/essential-notes-in-psyc hiatry/inter-professional-and-inter-cultural-competence- training-as-a-prevention-strategy-to-promote-collab

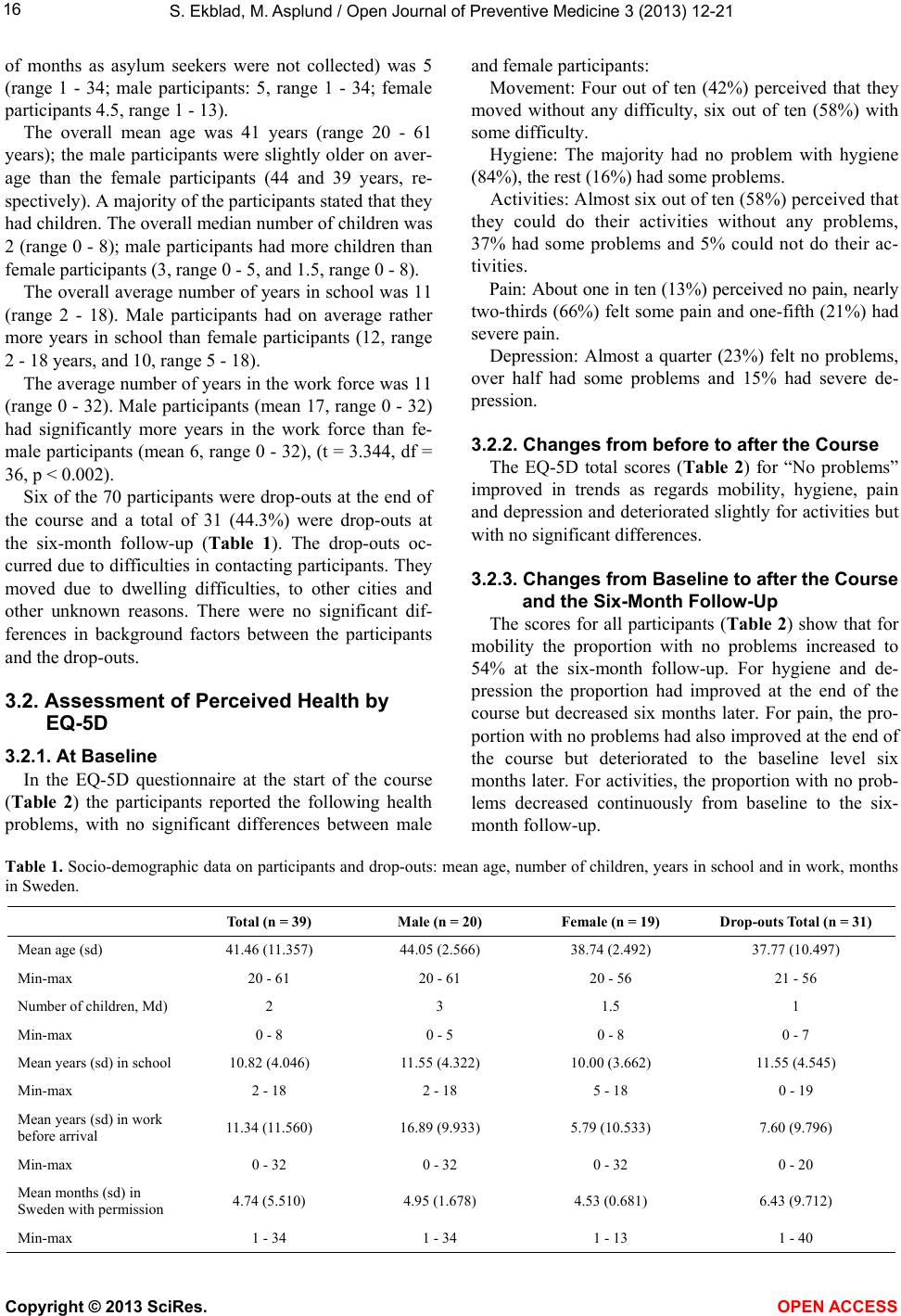

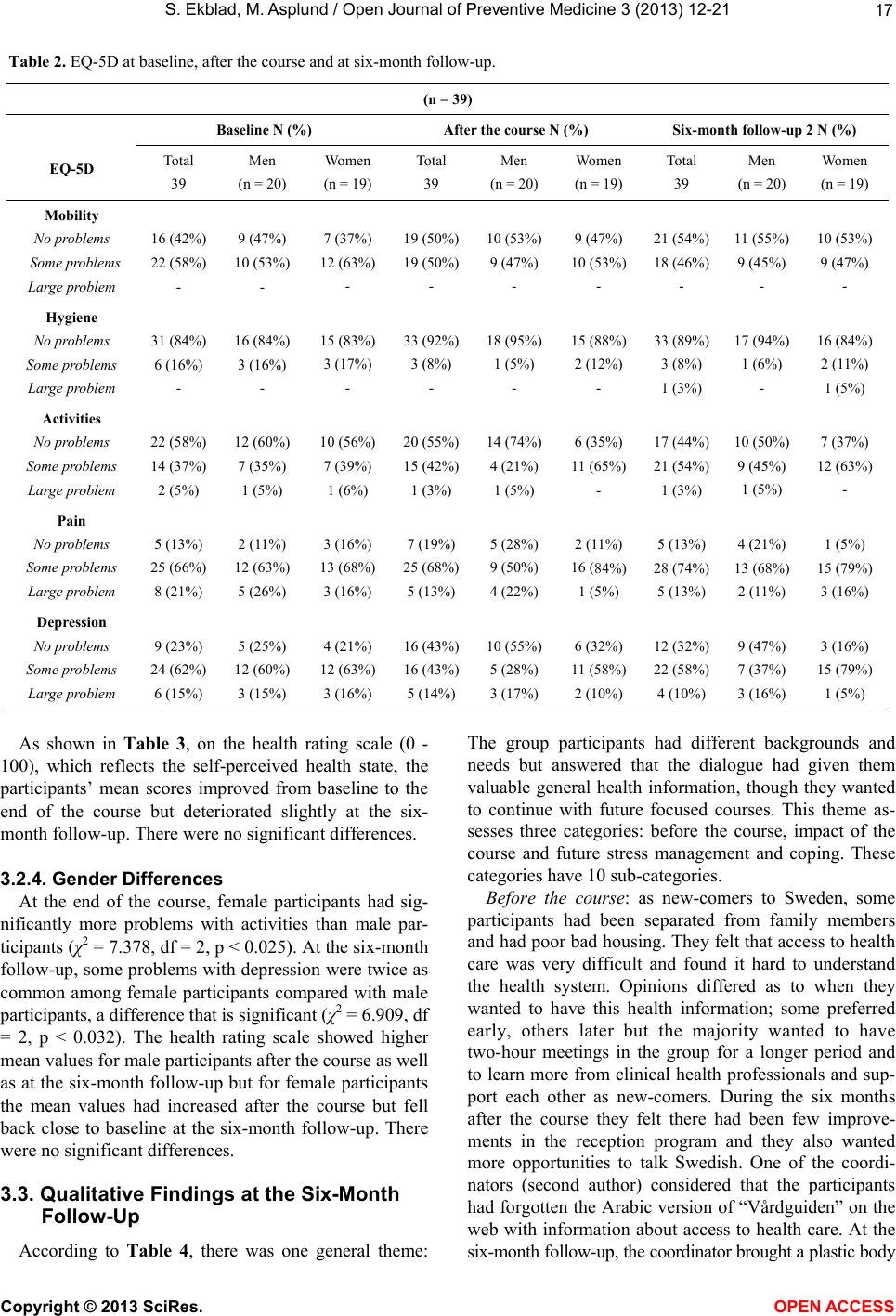

|