Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.2, 88-95 Published Online February 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.42012 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 88 Relationships between Personality and Coping with Stress: An Investigation in Swedish Police Trainees Jörg Richter1*, Lars Erik Lauritz2, Elizabeth du Preez3, Nafisa Cassimjee4, Mehdi Ghazinour5 1Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Eastern and Southern Norway, Oslo, Norway 2Basic Training Program for Police Officers, University of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden 3Division of Public Health and Psychosocial Studies, School of Psychology, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand 4Department of Psychology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA 5Department of Social Work, University of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden Email: *jrichterj@web.de, larserik.lauritz@polis.umu.se, elizabeth.dupreez@aut.ac.nz, nafisa.cassimjee@up.ac.za, mehdi.ghazinour@socw.umu.se Received November 13th, 2012; revised December 12th, 2012; accepted January 7th, 2013 The aim was to investigate relationships between personality characteristics derived from Cloninger’s personality theory and ways of coping. We investigated 103 police trainees by the Temperament and Character Inventory and Ways of Coping Checklist. There were several particularities characterising trainees within various personality profiles relating to coping. Each WoC scale was significantly predicted by varying personality subscales with temperament subscales mainly contributing to the prediction. Only personality domains harm avoidance, reward dependence, and self directedness could significantly be predicted by coping scales. Some coping behaviours often jointly occur depending on the specific stress- ful situation; and these combinations are related to particular personality trait constellations. Keywords: Ways of Coping; Psychobiological Theory of Personality; Temperament; Character; Police Trainees Introduction Since Lazarus and colleagues developed the concept of cop- ing with stress (Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Folkman & Lazarus, 1980, 1985) in the early 1980s much re- search has been conducted in order to understand the complex- ity and patterns of coping processes. Coping represents proc- esses of perception, evaluating and managing circumstances, making efforts to solve problems, or seeking to master, mini- mize, reduce or tolerate stress. “Coping is defined as cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or in- ternal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person.” (Hancock & Desmond, 2001: p. 85) The core aim of coping is “change” (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985) of external or internal conditions in order to achieve a state of wellbeing or to avoid emotionally negative conditions and maintaining positive psychological states. These changes need to occur despite enduring stress (Folkman, 1997) caused by intentional, conscious, and goal-directed stress-management (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Folkman and Lazarus (1985) referred to relationships be- tween personality and coping early in the development of their coping theory by differentiating between dispositional and epi- sodic variables affecting coping, with personality traits repre- senting enduring dispositions and coping itself understood as specific behaviour applied in particular situations. However, individuals were found to relatively consistently prefer and em- ploy particular coping behaviour across a wide range of situa- tions (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Since then, various attempts have been made to conceptualise and to investigate relationships between personality and coping with statements ranging from: personality and coping represent comprehensive and closely interrelated constructs, but are not identical (Fick- ova, 2001; McWilliams, Cox, & Enns, 2003; Murberg, 2009); their indicators are interrelated; personality and coping repre- sent parts of a continuum based on adaptation (Costa, Somer- field, & McCrae, 1996; Maltby, Day, McCutcheon, Gillett, Houran, & Ashe, 2004); there are structural similarities between measures of personality and coping behaviour; personality in- fluences the appraisal process and consequently the choice of coping style; personality affects coping strategy selection (Bol- ger & Zuckerman, 1995); certain personality traits are likely to facilitate particular coping behaviours (Vollrath, 2001; Suls & Martin, 2005); personality influences effectiveness of coping (Bolger & Zuckman, 1995; DeLongis & Holtzman, 2005); per- sonality and coping partly share their genetic basis (Kato & Pedersen, 2005; Jang, Thordarson, Stein, Cohan, & Taylor, 2007); coping as “personality in action under stress” (Bolger, 1990: p. 525); coping responses are only epiphenomena of personality traits, with no causal status independent of personality traits (McCrae & Costa, 1986); to “coping ought to be redefined as a personality process” (Vollrath, 2001: p. 341). Characteristics of individuals who cope with stress positively or negatively have long been investigated (Snyder et al., 2005; Antonovsky, 1987; Taylor & Brown, 1994; Folkman, 1997). For example, individuals scoring high on the neuroticism di- mension of the “Big Five” personality model are more often en- gaged in passive or maladaptive coping behaviours such as *Corresponding author.  J. RICHTER ET AL. hostile reactions, escape fantasies, self blame, withdrawal, wishful thinking, indecisiveness, or other types of passivity, whereas those scoring high in extraversion more often used active, approaching and rational problem solving behaviours or substitution (McCrae & Costa, 1986; Lau, Hem, Berg, Ekeberg, & Torgersen, 2006). Individuals scoring high in conscientious- ness have also been characterised by active coping and refrain- ing from passive coping (Vollrath, Torgersen, & Alnæs, 1998). Similar but more differentiated findings were reported applying a personality typology based on high or low scorers on the three above mentioned personality characteristics by Vollrath and Torgersen (2000). Even though the correlation between par- ticular personality characteristics and particular coping behav- iours were often found of low to moderate effect size (Con- nor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007), the variance of personality ex- plained about 25% of the variation in coping. Therefore, the investigation of just one particular coping behaviour or one separated personality characteristic might not be appropriate. However, “despite hundreds of studies, the influence of per- sonality on coping, and of both on outcomes, is only partly understood.” (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010: p. 695). For ex- ample, the following problems and questions remain: What happens to personality and coping under certain circumstances? How do various personality characteristics interact when an individual is confronted with a particular stressful situation? What determines our (coping) behaviour under certain circum- stances? How inter- and intra-individually consistent and gen- eralizable are these interactions in relation to coping? How reliable is our (coping) behaviour under certain circumstances? As both are partly shaped and developed by life-long learning processes, are they subject to change by training procedures or therapies? Furthermore, the impact of coping upon personality is very rarely conceptualized, and then primarily only in rela- tion to mastery and self-esteem. The primary aim of the present study was to investigate rela- tionships between personality characteristics derived from Clon- inger’s personality theory (Cloninger, Svrakic, & Przybeck, 1993) and ways of coping. Considering some of the shortcom- ings of previous research we focused on the interplay between various temperament and character domains and ways of cop- ing 1) based on similarities on personality between individuals; 2) based on relationships between variables similar to Ferguson (1991) who applied joint factor analysis to personality and coping data; and 3) on regression of personality to coping and vice versa; as well as 4) on relationships of both personality characteristics and coping with gender, alcohol use and suicide attempts in the past. Methods Sample Since the police is commonly described as a profession ex- posed to high levels of occupational stress (Chopko, 2010; Morash, Haarr, & Kwak, 2006; Stinchcomb, 2004) caused by sudden events of usually short duration which almost immedi- ately lead to psychological and physiological reactions, we in- vestigated police trainees from one of the three Swedish police academies at intake. 103 police trainees voluntarily participated in the research project within the first 2 weeks after intake. There were substantially more male (n = 68) than female (n = 35) trainees in the sample with males being older than females. Most of the participants were single and had already gained some other university education prior to starting police training. The trainees received information about the aims prior to the investigation and gave written consent before the start of the investigation. Participants were asked to complete a socio- demographic form and the Temperament and Character Inven- tory (TCI), the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R), the Ways of Coping Checklist (WoC) and the State Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI-II). The completion of the four question- naires took about one hour and the assessment was performed in the police academy’s rooms. However, the present analysis was only based on socio-demographic data, the TCI and WoC. The research project was approved by Regional Ethics Com- mittee at Umeå University (Sweden). This article forms the third scientific report about findings from a longitudinal re- search program on Swedish police officers’ personality devel- opment (du Preez, Cassimjee, Ghazinour, Lauritz, & Richter, 2009; Ghazinour, Lauritz, du Preez, Cassimjee, & Richter, 2009; Ghazinour & Richter, 2009). Instruments Temperament and Character Inventory The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (Cloninger, Przybeck, Svrakic, & Wetzel, 1994) was used to assess person- ality characteristics according to Cloninger’s bio-psychosocial theory. Cloninger’s psychobiological model of personality (Clon- inger, Svrakic, & Przybeck, 1993) refers to four independent, largely genetically determined dimensions of temperament: 1) novelty seeking (NS), a tendency toward exhilaration in re- sponse to novel stimuli or cues; 2) harm avoidance (HA), a heritable bias in the inhibition or cessation of behaviour; 3) reward dependence (RD), the tendency to maintain or pursue ongoing behaviours; and 4) persistence (PS), a tendency of perseverance in behaviour despite frustration and fatigue; and to three character dimensions, which are supposed to be pre- dominantly determined by socialisation processes during the lifespan: self-directedness (SD), the extent to which a person identifies the self as an autonomous individual; cooperativeness (CO), the extent to which a person identifies himself or herself as an integral part of the society as a whole; and self-transcen- dence (ST), the intensity of identification with unity of all things. The Swedish TCI version, version 9 (Brändström, Sig- vardsson, Nylander, & Richter, 2008), consists of 238 true/false items covering these seven personality dimensions by 26 sub- scales: exploratory excitability (NS1), impulsiveness (NS2), extravagance (NS3), disorderliness (NS4), anticipatory worry (HA1), fear of uncertainty (HA2), shyness (HA3), fatigability (HA4), sentimentality (RD1), attachment (RD3), dependence (RD4), responsibility (SD1), purposefulness (SD2), resource- fulness (SD3), self-acceptance (SD4), enlightened second na- ture (SD5), social acceptance (CO1), empathy (CO2), helpful- ness (CO3), compassion (CO4), integrated conscience (CO5), self-forgetful (ST1), transpersonal identification (ST2), and spiritual acceptance (ST3). Persistence is assessed by an eight items single dimension. Ways of Coping (WoC) Ways of Coping is a questionnaire with items representing a wide range of thoughts and acts that people use to deal with the internal and/or external demands of specific stressful encoun- ters (Folkman, 1985). The instrument consists of 66 items to be Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 89  J. RICHTER ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 90 answered on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = does not apply and/or not used; 3 = used a great deal) which are combined to eight scales (confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, plan- ful problem-solving, positive reappraisal). Usually an encounter is described by the subject in an inter- view or in a brief written description saying who was involved, where it took place and what happened. Sometimes a particular encounter, such as medical treatment or an academic examina- tion, is selected by the investigator as the focus of the ques- tionnaire (Folkman, 1985: p. 1). Therefore a stressful scenario that will frequently be encountered by police officers was pre- sented as the basis for responding to the WoC. The participants were encouraged to read the scenario: “Last week you were called to a car accident and you found a small child bleeding heavily”. Statistics A cluster analysis, Ward’s method, squared Euclidian dis- tances with standardised z-scores by variable, was performed in order to define groups of individuals of similar personality characteristics based on TCI domains. Means and sds of TCI domains and WoC scales were presented by cluster. MANO- VAs based on TCI domains and WoC scales were calculated testing for differences between clusters and for the impact of gender. Factor analysis, principal axis factoring, varimax rota- tion, based on TCI domains and WoC scales and based on TCI subscales and WoC scales were carried out searching for groups of related variables. To test for predictability between personality and coping scales sets of multiple regression analy- ses were performed firstly with WoC scales as independent variables and TCI domains and subscales as dependent vari- ables; and secondly with TCI subscales as independent and WoC scales as independent variables. Non-parametric tests were applied in testing for relationships of personality and cop- ing variables, gender and dichotomised variables suicide at- tempt in the past—yes versus no—and self reported alcohol consumption, never or seldom versus sometimes or often. Since this represented an explorative study, no correction for multiple testing was done. Results Cluster analyses were performed on TCI dimensions with solutions between 3 and 7 clusters. The 5-cluster solution was chosen to reflect the differences between these clusters best. We decided on 5 clusters because of the relatively equal sizes of all groups (13.5%, 21.2%, 32.7%, 16.3%, 16.3%, respec- tively). Furthermore, the change between every successive cluster was considerable from 3-cluster solution to 5 clusters, but the difference between 5-cluster solution and 6-cluster was small, therefore we decided on the 5-cluster solution as most adequate. The police trainees in the various clusters can be characterised as follows (Table 1): - Cluster 1: highest scores on SD (SD1 - SD5), lowest on ST (ST1 - ST3) compared to the others combined with medium scores on NS (high: NS1, NS4, medium: NS2, NS3), PS, and CO (CO1) and lowest scores on HA (lowest: HA1, HA3, HA4, low: HA2) and RD (RD1, RD3, RD4); - Cluster 2: highest score on PS and lowest on NS (NS2, NS3, NS4, low: NS1), medium scores on all other personality dimensions (except for high CO2); - Cluster 3: highest score on RD (RD3, RD4, high: RD1), low on HA (lowest: HA2, HA4, low: HA1, HA3), high scores on SD (highest: SD1, SD3, SD4, high: SD2, SD5), high scores on CO (highest: CO1, CO2, CO3, high: CO4, CO5) and high scores on NS (highest: NS1, high: NS3, me- dium: NS2, NS4) combined with medium scores on PS and ST (medium: ST1, ST3, low: ST2); - Cluster 4: highest score on NS (NS1, NS3, NS3, high: NS2), CO (CO2, CO4, CO5, high: CO1, CO3) and ST (ST1 - ST3), high scores on RD (highest: RD1, high: RD3, me- dium: RD4), high scores on SD (highest: SD2, SD4, high: SD3, medium: SD1, SD5) and medium on HA (medium: HA2, HA3, HA4, low: HA1) combined with low PS; - Cluster 5: highest score on HA (HA1 - HA4), lowest scores on PS, SD (SD1 - SD5) and CO (lowest: CO1, CO3, CO4, CO5, medium: CO2), high scores on NS (highest: NS2, NS4, high: NS3, lowest: NS1) combined with medium scores on RD (high: RD4, medium: RD1, low: RD3) and ST (ST1 - ST3) (Table 1). A MANOVA with TCI domains as dependent variables and cluster as fixed factor revealed that the main effect on all TCI domains were significantly different between clusters with high effect size (Pillai’s trace = 2.02; F(28/304) = 13.92; p < .001; 2 = .504; with high effect sizes for tests of between-subject-ef- fects ranged from .349 for CO to .469 for RD). The proportion of males and females significantly differed among clusters (contingency coefficient = .36; p-value = .005). All police trainees in group1 were men; groups 2 and 5 were mostly men (about three quarters of the clusters) whereas there was no difference in gender-ratio in group 3 and 4. A MANOVA with coping scales as dependent variables and cluster as fixed factor did not support a main effect of cluster (Pillai’s trace = .34; F(32/390) = 1.11; p = .323; .2 = .085). However, there was a significant difference between the clus- ters on scale positive reappraisal of medium effect size with Table 1. TCI dimensions by cluster (mean ± SD). Cluster NS HA RD PS SD CO ST 1 21.1 ± .92 7.3 ± 1.04 12.6 ± .53 4.0 ± .42 38.0 ± 1.10 33.6 ± .77 5.6 ± 1.00 2 16.7 ± .73 10.0 ± .83 16.2 ± .42 6.5 ± .34 35.5 ± .88 36.3 ± .61 11.0 ± .78 3 22.9 ± .59 7.5 ± .67 18.0 ± .34 5.5 ± .27 37.0 ± .71 37.4 ± .49 8.9 ± .63 4 25.5 ± .83 10.1 ± .95 17.9 ± .48 3.9 ± .38 36.5 ± 1.00 38.1 ± .70 16.4 ± .89 5 22.2 ± .83 16.7 ± .95 15.4 ± .48 3.1 ± .38 27.7 ± 1.00 32.5 ± .70 11.8 ± .89 Note: NS: Novelty Seeking; HA: Harm Avoidance; RD: Reward Dependence; PS: Persistence; SD: Self-Directedness; CO: Cooperativeness; ST: Self-Transcendence.  J. RICHTER ET AL. significant higher scores for cluster 4 compared to cluster 1 and 2 (test of between-subject-effect: F(4) = 3.29; p = .014; 2 = .117) and a tendency for scale escape avoidance. Neverthe- less, there were some particularities characterising the indi- viduals within the various clusters relating to coping (Table 2): - Cluster 1: lowest scores on confronting coping, highest on distancing, and lowest on accepting responsibility, escape avoidance and positive reappraisal; - Cluster 2: highest scores on distancing combined with low- est scores on escape avoidance and planful problem solv- ing; - Cluster 3: lowest scores on self control and escape avoid- ance; - Cluster 4: highest scores on confronting coping, support seeking, accept responsibility, and planful problem solving, and positive reappraisal combined with lowest scores on distancing and self control; - Cluster 5: highest scores on self control and escape avoid- ance combined with lowest scores on support seeking. Furthermore, in a MANOVA with coping scales as depend- ent variables and gender, age, marital status and educational level as fixed factors, the results were as follows: Age, educational level and marital status found to be non- significant factors relating to coping scales. There was only a significant main effect of large effect size (Pillai’s trace = .24; F(8/94) = 3.60; p = .001; 2 = .235) for gender based on the impact on distancing, self control and positive reappraisal. Men were found to score higher on distancing and self-control while women had higher score on positive reappraisal. Both, the Kaiser-Guttman criterion and the scree plot of the joint factor analysis based on TCI domains and WoC scales suggested a five-factor solution explaining 62.6% of the vari- ance in the data with two exclusive coping factors, two exclu- sive personality factors (SD, -HA, and CO/-NS and PS), and only one mixed factor with RD, HA, CO and negative loadings for distancing and self-control. A seven-factor solution was preferable for joint analysis based on the TCI subscales and WoC scales, explaining 53.8% of the variance in the data. Two were mixed factors (first: all HA subscales with negative load- ing, four SD subscales with positive loading, and a positive loading for distancing; sixth: all ST subscales and PS positively with self control negatively); two clear coping factors (second: accept responsibility, escape avoidance, positive reappraisal, and confronting coping all with positive loadings; fourth: plan- ful problem-solving, support seeking, self control, and con- fronting coping); and three clear personality factors (third: positively all RD, four CO, and two SD subscales; fifth: all RD, two SD, and all RD subscales; seventh: three NS subscales combined with negatively loading PS). When testing the predictive power of personality subscales relating to WoC scales in multiple regression analyses, variance of the personality variables could explain significant variation only in confrontive coping and distancing when all personality subscales were used simultaneously (method: enter 11% and 14%, respectively) (Table 3). If the program is permitted to reduce the number of personality variables (method: stepwise), each of the WoC scales can be significantly predicted explain- ing between 4% (positive reappraisal by RD1) and 13% (dis- tancing by NS3 and HA2, and escape avoidance by RD1 and HA2) of the variance, with temperament subscales mainly con- tributing to the prediction. Only accept responsibility was ex- clusively determined by character subscales SD1 and CO5 and on confrontive coping and self control a mix of temperament and character subscales (SD1 and CO4, respectively) were of impact. From the opposite perspective, only the personality domains HA, RD, and SD could significantly be predicted by coping scales (between 9%—RD and 17%—SD) (Table 4). Domains NS and CO could not even be predicted by applying a stepwise method. Variance in coping scales distancing and escape avoid- ance was mainly responsible for prediction of variation in tem- perament subscales, particularly in HA, whereas variance in self control and confronting mainly contributed to the explana- tion of variation in character subscales, especially in SD sub- scales combined with a negative impact of escape avoidance coping. Positive reappraisal significantly contributed to the exclusive explanation of variation on ST subscales, whereas support seeking was predictive for RD and CO subscales. One third of those trainees who reported a suicide attempt once during their lifetime were categorised in cluster 3 and one fourth of them belonged to cluster 2, whereas only one trainee with a suicide attempt was in cluster 1. Those individuals who reported a suicide attempt in the past showed higher HA (HA1, HA3, and HA4), lower SD (SD2, SD5) combined with a ten- dency to more escape avoidance (Mann-Whitney U-test, exact significance: .027, .022, and .085, respectively) than those without such an event. The distribution relating to drinking alcohol never or seldom versus sometimes or often did not differ across clusters 1, 2, and 4. However, trainees in cluster 3 (60% versus 40%) and 5 (87% versus 13%) more often reported drinking alcohol some- times or often than drinking never or seldom. When comparing police trainees who reported drinking alcohol never or seldom with those reported as drinking alcohol sometimes or often, the latter showed higher NS (NS2, NS4) and lower PS combined with more self controlling coping and more escape avoidance (Mann-Whitney U-test, exact significance: .042, .013, .024 and .062, respectively). There was a significant relationship Table 2. Coping scales by personality cluster (mean ± SD). Cluster Confr. Dist. S. C. S. S. A. R. E. A. P. P. S. P. R. 1 6.8 ± .66 6.6 ± .76 12.0 ± .78 11.1 ± .63 3.6 ± .50 5.9 ± .78 11.5 ± .70 8.9 ± .68 2 7.0 ± .53 6.6 ± .60 11. 5 ± .62 12.2 ± .51 3.8 ± .40 5.9 ± .62 10.9 ± .56 9.7 ± .55 3 7.1 ± .42 5.8 ± .49 11.1 ± .50 11.9 ± .41 3.9 ± .32 5.9 ± .50 11.8 ± .45 10.6 ± .44 4 8.4 ± .60 5.6 ± .69 11.1 ± .71 12.5 ± .58 4.3 ± .46 6.9 ± .71 11.9 ± .63 11.9 ± .62 5 8.2 ± .60 5.8 ± .69 12.6 ± .71 10.9 ± .58 3.9 ± .46 7.6 ± .71 11.0 ± .63 10.8 ± .62 Note: Confr.—Confrontive; Dist.—Distancing; S. C.—Self Control; S. S.—Seeking Social Support; A. R.—Accept responsibility; E. A.—Escape Avoidance; P. P. S.—Planful Problem-Solving; P. R.—Positive Reappraisal. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 91  J. RICHTER ET AL. Table 3. Multiple regressions with personality subscales as independent and coping scales as dependent variables (1st row: method enter; further rows: method stepwise). Independent Dependent Standardized β t p Adjusted r2 F p Personality RD1 SD1 Confronting .21 −.23 2.24 −2.40 .027 .018 .11 .06 .11 7.15 7.15 .001 .001 Personality NS3 HA2 Distancing −.31 −.20 −3.40 −2.22 .001 .028 .14 .10 .13 1,70 8.87 .040 <.001 Personality PS Support seeking .26 2.70 .008 .05 .06 1.20 7.28 .268 .008 Personality RD3 CO4 Self control −.27 −.21 −2.94 −2.22 .004 .028 .03 .08 .12 1.13 7.83 .329 .001 Personality SD1 CO5 Accept responsibility −.281 .20 −2.92 2.09 .004 .024 .04 .05 .08 .85 5.42 .663 .006 Personality RD1 HA2 Escape avoidance .28 .21 2.94 2.29 .004 .024 .10 .09 .13 1.47 8.56 .102 <.001 Personality NS1 Planful problem solving .24 2.49 .014 .06 .05 1.26 6.19 .221 .014 Personality RD1 Positive reappraisal .22 2.30 .024 .02 .04 1.08 5.27 .388 .024 between the personality clusters and the dichotomised alcohol drinking variable (Fisher’s exact test = 7.71; p = .049) mainly caused by the fact that there were substantially more individu- als in cluster 5 who reported drinking alcohol sometimes or often rather than never or seldom (87% versus 13%). Discussion The major aim of the present study was to investigate the complex interplay between personality characteristics derived from Cloninger’s personality theory (1993) and ways of coping in police trainees shortly after admission to the police academy. The relationship coefficients were not as high as expected but only somewhat lower than reported in the literature (for exam- ple, Murberg, 2009). There are various possible reasons for this negative finding. First of all, the trainees were asked to respond to a theoretical event when answering the WoC even though there is a reasonable likelihood that they had already experi- enced such an event. Moreover, various variables other than personality characteristics might impact upon the choice of coping behaviours such as gender, professional experience, having children. Furthermore the findings may be biased by the sample that was highly selected and dominated by healthy, male and highly educated individuals compared to the Swedish general population (Ghazinour et al., 2009), which might have let to smaller variance in the variables. The low correlations were consequently reflected by the lack of a substantial specificity of relationships between personality clusters and coping behaviours, by the small overlap between personality variables and coping scales in joint factor analyses, and by non-significant regression coefficients or coefficients of low effect size. However, there were several remarkable ten- dencies and some particularities caused by the predefined situa- tion presented in the application of the WoC. The main finding was that the use of some coping behaviours often jointly occur, in the sense that a coping style and a com- bination of personality characteristics seem to be related to the “coping styles” described below. Overall, seeking support and planful problem solving were the most often applied and escape avoidance, accept responsibility, and distancing the less often used coping behaviours. This combination matches the implicit demands of the particular situation offered to the participants. When analysing in more detail the complex interplay be- tween coping behaviour and personality based on personality clusters in the particular situation of a child bleeding heavily after a car accident the following picture could be observed: Those trainees (Cluster 1) who tried the hardest to stay de- tached from the situation (distancing) compared to the others, were also those who took the lowest risk in changing the situa- tion (confronting); acknowledged their role in the situation (accept responsibility) to the lowest level; and showed the low- est tendencies to wishful thinking (escape avoidance). This combination of coping behaviour expressions was related to the most relaxed, courageous, composed and optimistic tendencies (lowest HA) combined with the most practical and tough minded attitudes (lowest RD). Additionally, they were charac- terised by the most intensive impatience and rationalism (low- est ST) but also the most maturity, responsibleness, goal-ori- entedness, and integrity (highest SD). When the most intensive detachment from the situation (dis- tancing) was combined with the lowest levels of situational avoidance or wishful thinking (escape avoidance) and the least problem-focused efforts to alter the situation (planful problem solving), trainees were on average characterised by the slowest engagement in new activities, mainly sticking with familiar routines (NS) combined with the most intensive persistence, stability despite frustration, and perfectionism (Cluster 2). The highest level of deliberate problem-focused efforts or analytic approach (planful problem solving) was substantially related to the lowest efforts to escape or to avoid the problem (escape avoidance); and the lowest efforts to regulate one’s own feelings were substantially associated with the highest sensitive- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 92  J. RICHTER ET AL. Table 4. Multiple regressions with coping scales as independent and personality variables as dependent variables (1st row: method enter; further rows: method stepwise). Independent Dependent Standardized β t p Adjusted r2 F p Coping Planful problem solving Self control NS1 .37 −.35 3.80 −3.58 <.001 .001 .14 .05 .15 3.20 6.65 10.11 .003 .011 <.001 Coping NS2 .04 .46 .879 Coping Distancing NS3 −.33 −3.50 .001 .07 .10 1.99 12.23 .056 .001 Coping NS4 .01 1.14 .346 Coping NS .02 1.30 .251 Coping Distancing HA1 −.20 −2.04 .044 .02 .03 1.29 4.14 .259 .044 Coping Escape avoidance Distancing Planful problem solving HA2 .29 −.24 −.19 3.12 −2.64 −2.09 .002 .010 .039 .15 .06 .12 .15 3.24 7.91 8.01 6.98 .003 .006 .001 <.001 Coping Escape avoidance Distancing HA3 .22 −.21 2.34 −2.22 .021 .029 .04 .03 .07 1.51 4.39 4.75 .164 .039 .011 Coping Escape avoidance HA4 .20 2.07 .041 .01 .03 .95 4.27 .481 .041 Coping Escape avoidance Distancing HA .31 −.26 .001 .005 .11 .08 .14 2.62 9.30 9.05 .012 .003 <.001 Coping Escape avoidance Distancing Support seeking RD1 .33 −.21 .19 3.59 −2.31 2.14 .001 .023 .035 .15 .09 .12 .15 3.44 11.44 8.25 7.22 .002 .001 <.001 <.001 Coping Self control RD3 −.32 −3.38 .001 .06 .09 1.78 11.41 .090 .001 Coping Accept responsibility Confronting RD4 .26 −.25 2.68 −2.51 .009 .014 .08 .03 .08 2.12 4.02 5.27 .042 .048 .007 Coping Distancing Positive reappraisal Self control RD −.19 .22 −.21 −2.00 2.32 −2.15 .048 .023 .034 .09 .04 .07 .10 2.22 5.29 4.74 4.82 .033 .023 .011 .004 Coping Support seeking PS .27 2.87 .005 .02 .07 1.22 8.22 .296 .005 Coping Confronting SD1 −.29 −3.08 .003 .08 .08 2.15 9.46 .039 .003 Coping Self control SD2 −.26 −2.75 .007 .06 .06 1.88 7.54 .072 .007 Coping Escape avoidance SD3 −.32 −3.36 .001 .08 .09 2.08 11.27 .046 .001 Coping Confronting Planful problem-solving Self control SD4 −.26 .29 −.20 −2.56 2.87 −2.00 .012 .005 .048 .09 .05 .09 .12 2.33 6.22 6.06 5.49 .025 .014 .003 .002 Coping Distancing Escape avoidance SD5 .31 −.30 3.34 −3.31 .001 .001 .13 .07 .15 2.93 8.89 1.35 .006 .004 <.001 Coping Escape avoidance SD −.39 −4.31 <.001 .17 .15 3.69 18.57 .001 <.001 Coping CO1 .02 .725 .669 Coping CO2 .01 1.11 .361 Coping Seeking support CO3 .20 2.01 .048 .03 .03 1.34 4.02 .234 .048 Coping Self control CO4 −.26 −2.68 .009 .03 .06 1.40 7.19 .206 .009 Coping CO5 .04 .54 .825 Coping CO .03 1.38 .214 Coping Confronting ST1 .27 2.85 .005 .03 .07 1.42 8.11 .199 .005 Coping ST2 .02 1.31 .250 Coping Positive reappraisal Distancing Self Control ST3 .28 −.20 −.19 3.00 −2.08 −2.02 .003 .040 .046 .09 .05 .10 .12 2.28 6.21 6.42 5.78 .028 .014 .002 .001 Coping Positive reappraisal ST .25 2.65 .009 .06 .06 1.80 7.02 .086 .009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 93  J. RICHTER ET AL. ity to social cues facilitating warm relationships and under- standing of others’ feelings (RD) in combination with high responsibility for one’s own behavioural choices, reliability and trustworthiness (SD), high acceptance of other people, empathy, tolerance, compassion, and service-mindedness (CO), and highly relaxed, courageous, composed and optimistic feelings (HA) (Cluster 3). Individuals in Cluster 4 were characterised by the most com- plex interplay of coping behaviours as well as of associated expressions of personality characteristics. Their coping efforts represented a combination of the highest tendencies in risk taking (confrontation), the highest commitment in trying to put things right (accept responsibility), the highest level of prob- lem-focused efforts to alter the situation (problem solving), and the highest efforts to view the situation positively by focusing on their personal growth (positive reappraisal), associated with the most intensive seeking of social support (support seeking), the lowest efforts to minimise the significance of the situation (distancing) and regulate their own feelings (self controlling). Consequently they are characterised by the highest level of excitability, exploration, enthusiasm, and impulsiveness (NS), the highest social sensitivity, emotional warmth, and sociability (RD), the highest identification with and acceptance of others, empathy, and compassion (CO), and the highest levels of pa- tience, selflessness, and creativity (ST). The opposite emotional and behavioural tendencies in RD and ST might possibly de- termine the opposite coping tendencies relating to confronting coping, distancing, and positive reappraisal among those indi- viduals grouped in cluster 1. The highest efforts to regulate one’s own feelings and actions (self controlling), the most intensive wishful thinking and ten- dencies to escape the situation (escape avoidance) combined with the lowest efforts in social support seeking (seeking sup- port) were associated with the highest levels of cautiousness, fearfulness, nervousness, and discouragement (HA), the highest inactivity, unstableness, and unreliability (PS), the weakest, most destructive, ineffective, and unreliable behavioural ten- dencies (SD), as well as the most self absorbed, unhelpful, lacking empathy and compassion (CO) (cluster 5). This “self- ish” coping style corresponds perfectly to the rather neurotic personality characteristics. Interestingly, most of the trainees in this cluster comprised about one sixth of the sample reporting relatively high alcohol consumption levels. The complexity of the associations between personality characteristics and coping behaviour can be observed, for ex- ample, when analysing differences between trainees from clus- ter 1 compared to trainees in cluster 2. They both share the lowest scores on distancing and escape avoidance coping, but when these coping behaviours were associated with the lowest accept responsibility and positive reappraisal behaviours, the trainees are characterised by lowest HA, lowest RD, lowest ST, and highest SD (the latter seemingly an expression of over- evaluation) (cluster 1), whereas the highest PS and lowest NS were related to the combination with the lowest planful prob- lem solving. Another example can be seen in the differentiation between trainees from cluster 3 and 4 who share the lowest scores on self controlling and highest scores on planful problem solving. When this condition was related to high SD and low HA, es- cape avoidance coping was rarely preferred (cluster 3). When it was related to very high confrontive coping and very high ac- ceptance of responsibility, then highest scores on NS and ST were characteristic. Unexpectedly, temperament subscales were mainly of pre- dictive impact upon coping behaviours. However, acknowl- edging one’s own role in the problem (accept responsibility) was substantially determined exclusively by character subscales responsibility (SD1) and integrated conscience (CO5) reflecting reliability and trustworthiness combined with honesty and sta- ble ethical principles. Confrontive coping in a sense of aggres- sive efforts to alter the situation and some risk taking was pre- dicted by responsibility (SD1) combined with preference for intimacy in social relationships (RD3), whereas self control, in the sense of making an effort to regulate one’s own feelings and actions, was explained by compassion and benevolence com- bined with sentimentality and sympathy (RD1). Cognitive efforts to detach oneself from the problem or to minimise the significance of the situation (distancing) in com- bination with wishful thinking and behavioural efforts to escape from the situation or to avoid the problem (escape avoidance) were mainly predictive for temperament subscales, particularly for HA subscales. Support seeking coping efforts were mean- ingfully predictive for the RD and CO subscales, whereas ef- forts to develop a positive meaning of the stress (positive reap- praisal) substantially explained variance in ST subscales. Summarising the findings of the presented investigation we conclude that the detailed analysis of the complex interplay between coping and personality based on TCI subscales relating to a specific stressful, profession-related situation could make an important and meaningful contribution to the understanding of both phenomena in a particular group (police trainees) that may be generalisable to other samples and situations. However, the interpretation of the present findings is limited by the ex- plorative nature of the study, the small sample size limiting the possibilities of statistical analysis. Even though the presentation of a standardised stressful situation as target stimulus for as- sumed personal coping behaviour implied the possibility of a direct comparison and group analysis on coping, the theoretical nature of the situation can be evaluated as a disadvantage of the study because of the many controllable variables that might have biased the responses to the WoC items (for example, the current emotional state of the trainee, prior experience of such a situation, or his or her ability to imagine the presented situa- tion). Furthermore, the exclusive use of self report data cer- tainly represents a limitation of the study. Our findings support once again that 1) personality and cop- ing are comprehensively interrelated (Fickova, 2001; McWilliams, Cox, & Enns, 2003; Murberg, 2009); 2) that some coping be- haviours often jointly occur depending on the specific stressful situation, event or a class of events, and that these combinations are related to particular personality trait constellations; 3) that structural similarities exist between personality and coping; 4) that certain personality traits are likely to facilitate particular coping behaviours and, thereby affect coping strategy selection (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Vollrath; 2001; Suls & Martin, 2005); but 5) our findings do not support the suggestion that coping responses are only epiphenomena of personality traits (McCrae & Costa 1986). REFERENCES Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health. San Fran- cisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Bolger, N. (1990). Coping as a personality process: a prospective study. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 94  J. RICHTER ET AL. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 525-537. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.525 Bolger, N., & Zuckerman, A. (1995). A framework for studying per- sonality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 69, 890-902. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.890 Brändström, S., Sigvardsson, S., Nylander, P. O., & Richter, R. (2008). The Swedish version of the temperament and character inventory (TCI): A cross-validation of age and gender influences. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 24, 14-21. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.24.1.14 Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 679-704. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352 Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Per- sonality and Social Psychology, 56, 267-283. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267 Chopko, B. (2010). Posttraumatic distress and growth: An empirical study of police officers. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 64, 55-72. Cloninger, C. R., Przybeck, T. R., Svrakic, D. M., & Wetzel, R. D. (1994). The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. St. Louis, MO: Center for Psychobiology of Personality. Cloninger, C. R., Svrakic, D. M., & Przybeck, T. R. (1993). A psycho- biological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50, 975-990. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008 Connor-Smith, J., & Flachsbart, C. (2007). Relations between personal- ity and coping: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 1080-1107. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080 Costa Jr., P. T., Somerfield, M. R., & McCrae, K. R. (1996). Personal- ity and coping: A reconceptualization (pp. 44-61). In M. Zeidner, & N. S. Endler (Eds.). Handbook of coping: Theory, research, appli- calions. New York: Wiley. De Longis, A., & Holtzman, S. (2005). Coping in context: The role of stress, social support, and personality in coping. Journal of Personal- ity, 73, 1633-1656. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00361.x Du Preez, E., Cassimjee, N., Ghazinour, M., Lauritz, L. E., & Richter, J. (2009). Personality of South African police trainees. Psychological Reports, 105, 539-553. doi:10.2466/pr0.105.2.539-553 Ferguson, E. (2001). Personality and coping traits: A joint factor analy- sis. British Journal of Health Psychology, 6, 311-325. doi:10.1348/135910701169232 Fickova, E. (2001). Personality regulators of coping behavior in ado- lescents. Studia Ps y chol ogic a, 43, 321-329. Folkman, S. (1985). Ways of coping (revised). San Francisco, CA: Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at UCSF. Folkman, S. (1997). Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Sciences and Medicine, 45, 1207-1221. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3 Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a mid- dle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239. doi:10.2307/2136617 Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping three stages of a collage examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150-170. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150 Ghazinour, M., Lauritz, L. E., du Preez, E., Cassimjee, N., & Richter, J. (2009). An investigation of mental health and personality in Swedish police trainees upon entry to the police academy. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 25, 34-42. doi:10.1007/s11896-009-9053-z Ghazinour, M., & Richter, J. (2009). Anger related to psychopathology, temperament and character in healthy individuals—An explorative study. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 37, 1197-1212. doi:10.2224/sbp.2009.37.9.1197 Hancock, P., & Desmond, P. (2001). Stress, workload, and fatigue. London: LEA Jang, K. L., Thordarson, D. S., Stein, M. B., Cohan, S. L., & Taylor, S. (2007). Coping styles and personality: A biometric analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping, 20, 17-24. doi:10.1080/10615800601170516 Kato, K., & Pedersen, N. L. (2005). Personality and coping: A study of twins reared apart and twins reared together. Behavior Genetics, 35, 147-158. doi:10.1007/s10519-004-1015-8 Lau, B., Hem, E., Berg, A. M., Ekeberg, Ø., & Torgersen, S. (2006). Personality types, coping, and stress in the Norwegian police service. Personality and individual Differences, 41, 971-982. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.006 Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill. Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. Maltby, J., Day, L., McCutcheon, L. E., Gillett, R., Houran, J., & Ashe, D. D. (2004). Personality and coping: A context for examining ce- lebrity worship and mental health. British Journal of Psychology, 95, 411-428. doi:10.1348/0007126042369794 McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1986). Personality, coping, and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. Journal of Personality, 54, 385-405. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x McWilliams, L. A., Cox, B. J., & Enns, M. W. (2003). Use of the cop- ing inventory for stressful situations in a clinically depressed sample: Factor structure, personality correlates, and prediction of distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 423-437. doi:10.1002/jclp.10080 Mitchell, J. T., & Bray, G. (1990). Emergency services stress. Engle- wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Morash, M., Haarr, R., & Kwak, D. (2006). Multilevel influences on police stress. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 22, 26-43. doi:10.1177/1043986205285055 Murberg, T. A. (2009). Associations between personality and coping styles among Norwegian adolescents. Journal of Individual Differ- ences, 30, 59-64. doi:10.1027/1614-0001.30.2.59 Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Suls J., & Martin R. (2005). The daily life of the gar- den-variety neurotic: reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of Personality, 73, 1485-1509. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00356.x Stinchcomb, J. B. (2004). Searching for stress in all the wrong places: Combating chronic organizational Stressors in policing. Police Prac- tice and Research, 5, 259-277. doi:10.1080/156142604200227594 Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1994) Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 21-27. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.21 Vollrath, M. (2001). Personality and stress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 335-347. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00245 Vollrath, M., & Torgersen, S. (2000). Personality types and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 18, 117-125. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)00110-E Vollrath, M., Torgersen, S., &Alnæs, R. (1998). Neuroticism, coping and change in MCMI-II clinical syndromes: Test of a mediator model. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 39, 15-24. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00051 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 95

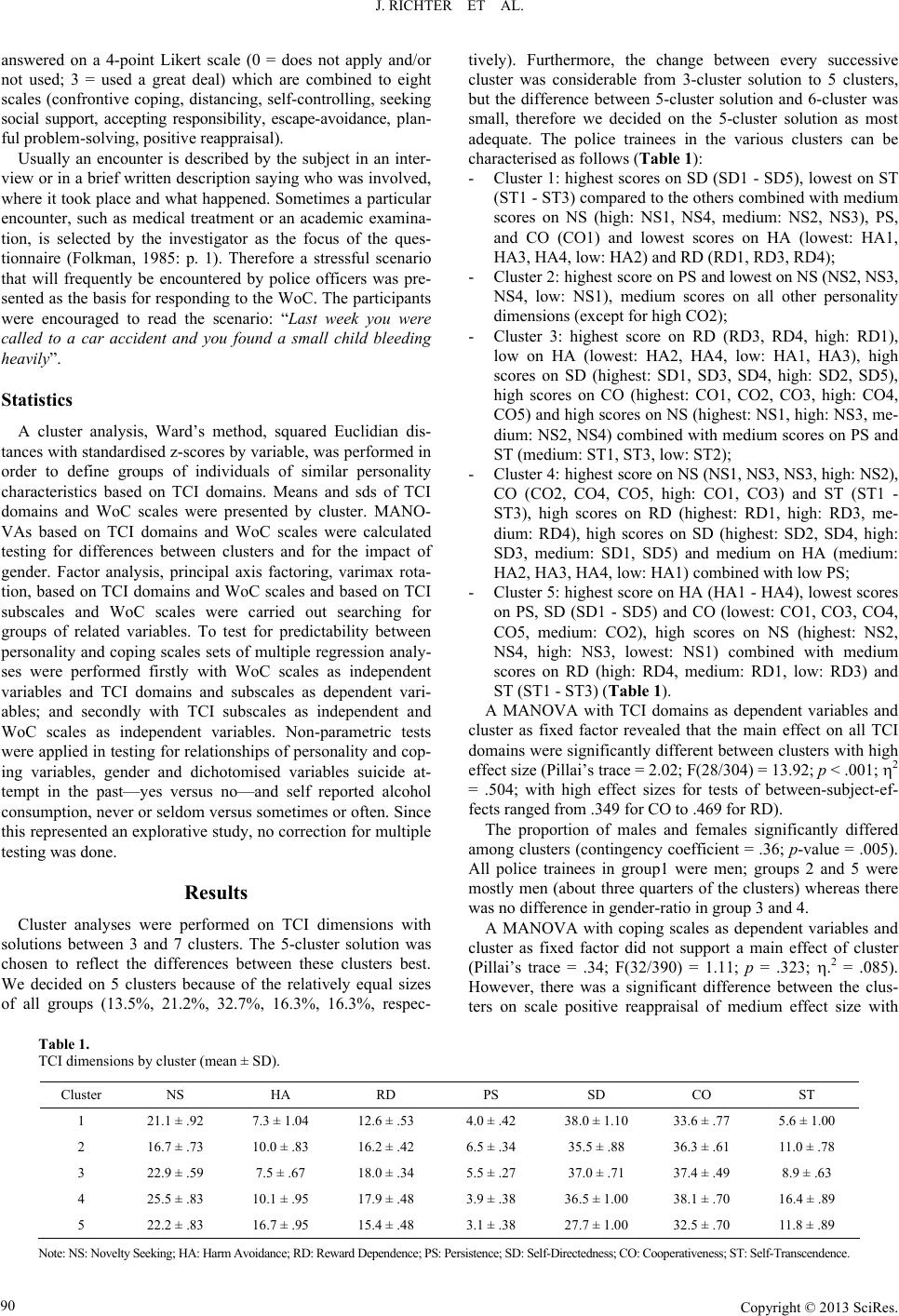

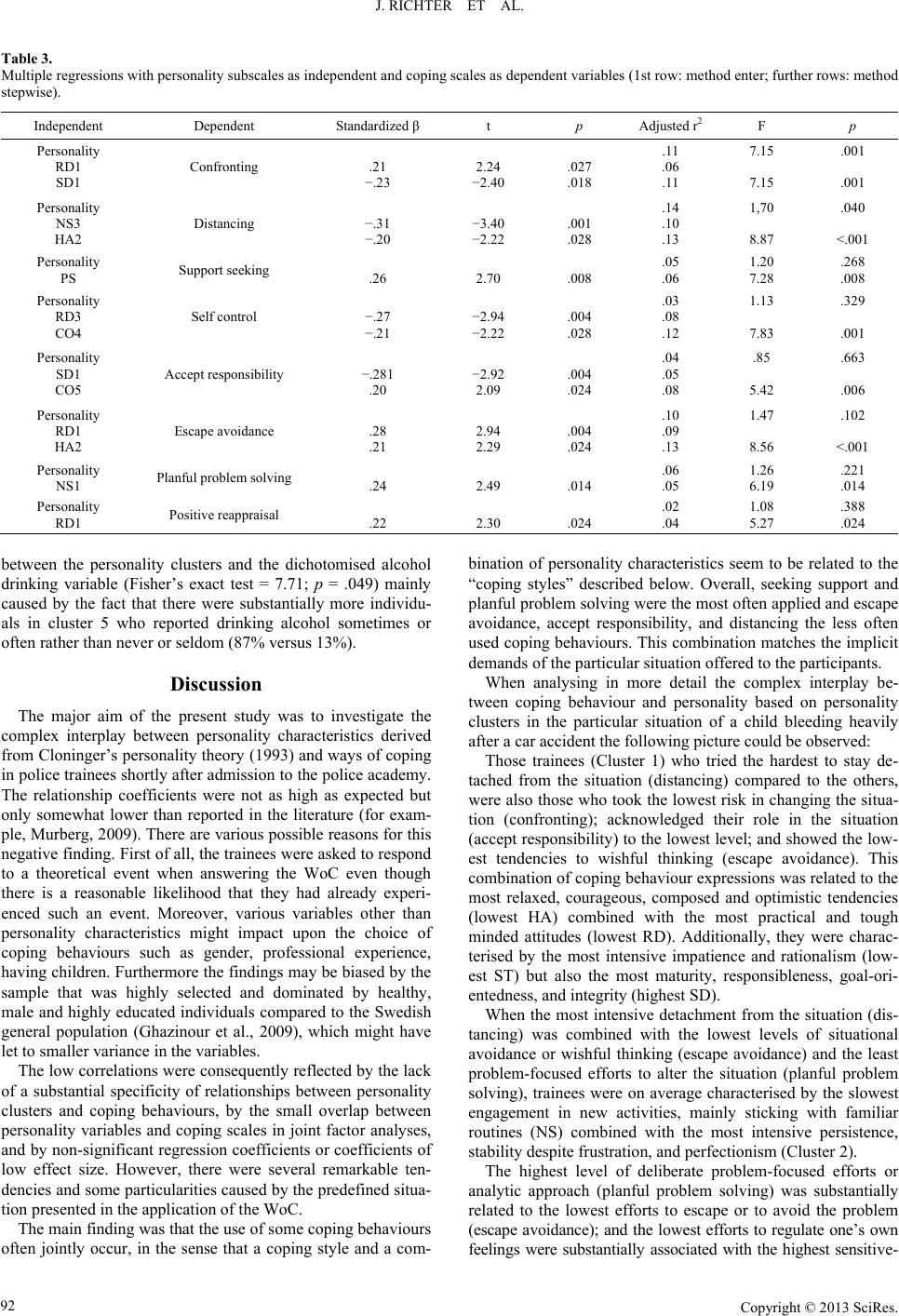

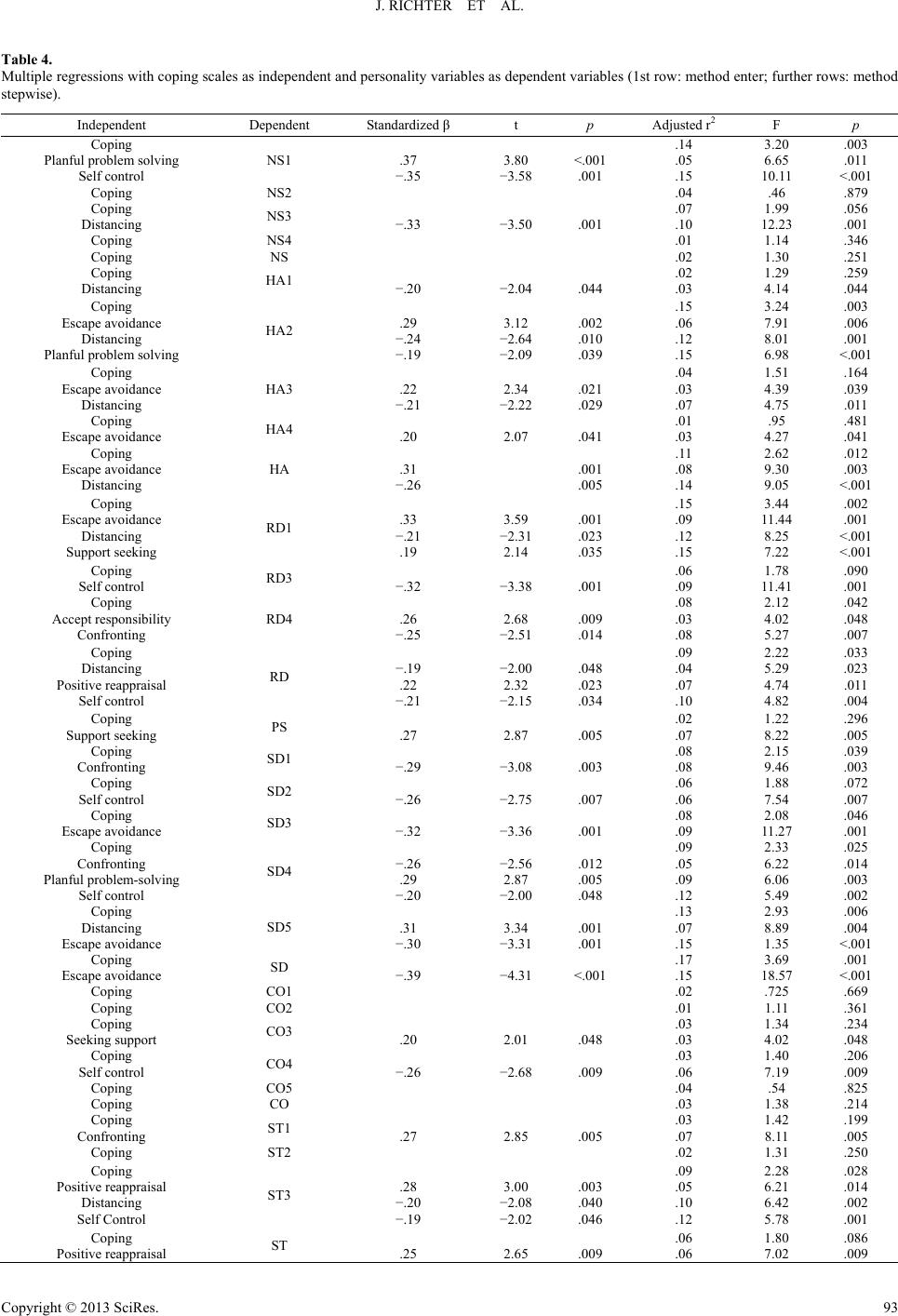

|