Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.2, 101-109 Published Online February 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.42015 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 101 Relationships between Playfulness and Creativity among Students Gifted in Mathematics and Science Cheng-Ping Chang Department of Education, National University of Tainan, Tainan, Taiwan Email: justin23@mail.nutn.edu.tw Received November 19th, 2012; revised December 22nd, 2012; accepted January 4th, 2013 Globalization and the multitude of technological changes that have affected societies in recent years have introduced complex and diverse problems into the daily lives of individuals. Indeed, great effort is ex- pended to create rich and abundant lives, especially in the age of the knowledge economy. In this context, “creativity” has come to be seen as the most precious human asset. Many scholars have suggested that foundational knowledge in certain academic fields is necessary for creative thinking. Thus, this study will focus on creativity in the field of mathematics. Additionally, many studies have found that playfulness enhances creativity and exploration. This study sought to explore the role of playfulness learning mathe- matics to gain in-depth understandings of the relationship between playfulness and creativity as well as the effect of playfulness on creativity. This study used questionnaires to collect data relating to the play- fulness and creativity of junior high school students who were gifted in mathematics and science. Data were analyzed using SPSS17.0 to explore the relationships among dimensions. This study used a ran- dom-sampling approach to select a sample of junior high school students who were gifted in mathematics and science. A total of 360 questionnaires were distributed, and our valid return rate was 94%. This study confirmed that playfulness enhances individual creative performance and that personal playfulness can predict and has a positive influence on creativity. Keywords: Students Gifted in Mathematics and Science; Playfulness; Creativity Introduction As science and technology have come to exert increasingly greater influence on the daily lives of people, mathematics education has also becomes increasingly important (Lofland, 1993). Mathematics is not only the basis of science but also plays a foundational role in the development of technology and thought and serves as an index and promoter of the evolution of civilization. Mathematics education is an important way to inspire students to develop the ability to think independently and logically. The curricula and educational policies in Taiwan emphasize mathematics education; beginning in the 2012 aca- demic year, junior high and elementary schools implemented the “nine-year uniform” curriculum. Mathematics courses can contribute the following to the education of students: 1) its emphasis on exploration and research can inspire curiosity, observation, active exploration, identification of problems, and application of learning in one’s life; 2) its reliance on inde- pendent thinking and problem-solving can nurture abilities to practice independent thinking and reflection, engage in the systematic evaluation of problems, and participate in efforts to effectively resolve problems and conflicts. Thus, mathematics is not only of theoretical interest but is also a tool that can be used in daily life to resolve problems. The mental development of students, including the ability to think and deduce, are cen- tral to resolving the mathematical problems that arise in daily life. Mathematics is also closely related to career development and the complete realization of one’s potential (Wei, 1996). In the context of globalization and technological change, people encounter more complex and diverse problems on a daily basis. To solve these complex issues, people continue to attempt to use their creativity to establish rich lives filled with abundance. Guilford (1967) suggested that creativity and the ability to solve problems are the two most complex types of human mental ability; in the age of the knowledge economy, especially, creativity has come to be seen as the most precious human asset. Sternberg (2001) indicated that wisdom seeks balance between the novel and the conservative. Wise people have intelligence as well as creativity, and when solving prob- lems, they can seek the optimal compromise between stability and change in the context of their social culture. Thus, creativ- ity and innovation are very important aspects of human per- formance. Personal problem-solving abilities, technological renewal and development, and reform and innovation related to social culture and organization are closely connected with hu- man creativity. Many factors affect the development of creativity. Most lit- erature on the development of creativity underscores the roles of “intelligence,” “knowledge,” “social environment,” “forms of thought,” “motivation,” “personality traits,” and “cultural contexts”. Student creativity is related to personal characteris- tics. Amabile (1996) indicated that work-related motivation can enhance creativity and those individuals who are motivated to work focus on their activities with rational playfulness. Play- fulness can help individuals to be engaged in work or learning and to experience enjoyment in the process. Indeed, many studies have found that playfulness has a beneficial effect on creativity and exploration. Amabile (1996) proposed that tasks are seen as “work” from the perspective of extrinsic motivation, whereas they are seen as “play” from the perspective of intrin-  C.-P. CHANG sic motivation. Thus, it is predictable that greater creativity would be manifested in the latter pursuits. Yu (2005) noted that individuals would be expected to experience deep autonomous devotion, high levels of concentration, enjoyment in the process, stress relief, and relaxation in the context of high levels of playfulness; these factors may contribute to unusually good performance. Thus, it is necessary to understand the relation- ship between playfulness and work, especially in the context of the significant levels of academic stress in which junior high students show enhanced indicators of depression. This study sought to understand the role of students’ playfulness, to ex- plore the relationship between playfulness and creativity, and to clarify the effect of playfulness on creativity. Research Goal Based on the aforementioned considerations, the purposes of this study were as follows: 1) To use on-site measurement to understand the conditions under which junior high school students who are gifted in mathematics and science demonstrate playfulness and creativity. 2) To use on-site measurement to analyze the correlation between playfulness and creativity among junior high school students who are gifted in mathematics and science. 3) To identify the factors that predict the effect of playfulness on the creativity of junior high school students who are gifted in mathematics and science. Literature Review Gifted Students in Mathematics and Science Giftedness is an abstract and complex concept with no fewer than 100 definitions. The term gifted may by defined on the basis of external behaviors or internal characteristics (Sternberg & Davidson, 1986), and definitions have been grounded in quantitative, trait-oriented, environment-oriented, and educa- tion-oriented psychological perspectives (Feldhusen & Jarwan, 1993). However, despite differences in perspective, interna- tional researchers studying the concept of giftedness in aca- demic contexts have extended this concept to cover a variety of developmental domains. Among the best known of these mul- tifaceted approaches is the “structure of intellect” proposed by Guilford (1965), who argued that intelligence consists of 180 abilities. The most frequently cited research on the characteristics of gifted students was performed by Terman, who conducted a longitudinal study of 1500 children of high intelligence. This study identified that gifted students 1) started to read earlier, read more, used language with greater proficiency, and demon- strated a more sophisticated vocabulary compared with their non-gifted peers; 2) performed with excellence in tasks involv- ing mathematical deductive ability and scientific performance; 3) had broad interests in languages, sciences, and art; 4) were objective-oriented and motivated to pursue achievement, and they tended to persevere until reaching their goal; 5) were more accomplished in academic fields and seemed to be headed for success in professional fields; and 6) were self-confident and able to tolerate failure (Davis & Rimm, 1994). Wu (2006) and Kuo (2000) found that students gifted in mathematics and science 1) had displayed curiosity and interest in information relating to numbers since they were young; 2) understood concepts related to numbers and demonstrated strong abilities with respect to logical thinking, summarization, and deductive reasoning; 3) engaged in flexible thinking and used diverse reasonable and effective methods to solve prob- lems; 4) were willing to attempt to solve mathematics or sci- ence questions that were novel or beyond their age level; and 5) used symbols and images to represent and simplify complex information. Playfulness Playfulness can be interpreted in terms of abilities such as emotional expression and the use of intrinsic motivation as well as in terms of characteristics and behaviors such as naturalness, a sense of freedom, happiness, being childlike, playing, or be- ing funny. However, a more concrete definition of playfulness derives from Webster’s definition of “free inclination,” which appeared in the context of a 1953 explanation of the features of leisure activities. Webster defined the free qualities of leisure or games as 1) an element of an intrinsic attitude; 2) containing the characteristics of freedom; and 3) affecting the player’s leadership, control, satisfaction, and happiness in the game (Liberman, 1976). Early playfulness research focused on the education of chil- dren. In a 1965 study about divergent thinking in kindergarten children, Liberman clearly defined the dimensions and opera- tional definitions of playfulness and asserted that playfulness is a necessary intrinsic characteristic for infants to engage in games or leisure activities, especially when playing in natural contexts. Woszczynski, Roth, and Segars’ (2002) review of recent re- search discussed playfulness as an enduring personal character- istic that represents an important variable in the prediction of behavior. Some scholars have studied playfulness in terms of both situational factors and character traits and have found that playfulness is affected when the environment changes. This finding contradicted the notion that playfulness constitutes an enduring quality, regarding it instead as a state or situation in which interactions between subjects and the external environ- ment play an important role. Playfulness has been defined in terms of the extent of engagement in play itself and the result- ing pleasurable feelings experienced by the participants. Finally, scholars have combined considerations of character and situa- tion in their construct of playfulness as a stable and long-term personal characteristic that incorporates environment as well as character, just as anxiety derives from both personal character- istics and external pressures. Thus, playfulness research can be divided into three categories: studies adopting the character view, those adopting the situation view, and those adopting the character-situation-interaction view. Rogers and Sluss (1999) analyzed Einstein’s creativity and inventiveness and concluded that his childhood playfulness was related to his general character and creative ability. Lieberman (1977) reported that playfulness in childhood stimulated the playfulness of many scholars. Barnett (1990) replicated Lie- berman’s research and reported several new findings, specifi- cally, that playfulness constituted an intention and a personal characteristic; thus, it was an intrinsic factor that stimulated playing as well as an attitude leading to participation in play. Creativity Studies of creativity have generated a wide range of defini- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 102  C.-P. CHANG tions. Indeed, more than 225 ways to define and measure crea- tivity exist (Cropley, 2000; Runco, 2007). Several concepts define creativity as a characteristic of a person, and others iden- tify it as a process (Amabile, 1988). For example, Kirton (1976) included ideas of adaptation, improvement, and application. Rogers (1983) operationally defined a creative individual as one who initially performs the creative work. In her definition of creativity, Amabile (1983) included the idea of group inter- actions that produced novel and useful ideas. Kanter (1988) described creativity as a multistep procedure, only one step of which involved the generation of new ideas. Woodman, Sawyer, and Griffin et al. (1993) defined creativity as the generation of available and useful new products or services, the process by which ideas are developed, and the process by which individu- als work together in a complex social system. Therefore, most contemporary researchers and theorists have adopted a defini- tion that focuses on the product or the outcome of a prod- uct-development process (Amabile, 1983, 1988; Shalley, 1991; Woodman et al., 1993; Zaltman, Duncan, & Holbek, 1973). Chapter 1 of the Handbook of Creativity by Sternberger and Lubart (1999), “The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Para- digms,” lists seven research approaches to creativity, including those involving mysticism, that were used before scientific methods. The more recent, scientific methods include prag- matic approaches popular in the corporate world and the market, psychodynamic approaches that tend to rely on case studies, psychometric approaches that bring creativity research into the scientific laboratory, cognitive approaches that rely on psycho- logical activity and information processing, social and person- ality approaches that focus on environmental and individual differences, and confluence approaches that have received the most emphasis in the recent years. Recently, scholars have turned their attention to the reasons for the occurrence of crea- tivity because creative products emerge not only from the crea- tive subject but also from local environmental and cultural in- fluences. Thus, most recent studies have adopted the confluence approach, which views creativity as a composite that requires consideration of various individual, environmental, and cultural factors. This perspective entails the integration of various theo- ries to account for the various facets of creativity to produce a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. Studies on the Relationship between Playfulness and Creativity Many recent studies have noted that playfulness plays an important role in work. For the individual, playfulness can en- hance personal learning (Liberman, 1977), have a positive im- pact on emotions, degree of engagement, and satisfaction (Webster & Martocchoio, 1992), and promote the ability to adapt and react to the environment (Starbuck & Webster, 1991). Glynn and Webster (1992) have also asserted similar views. Their study of 300 adults residing in different areas of the United States found a positive correlation among playfulness, cognitive spontaneity, and creativity and reported that creativity can effectively predict work attitudes and performance. How- ever, the first task of students is to learn, and an attitude of playfulness toward learning will be very helpful to their educa- tional achievement. Creativity has frequently been connected to playfulness (Amabile, 1988; Liberman, 1977), and scholarly observations have shown that playfulness is indeed a necessary component of creative thought (Liberman, 1977). A study about creativity conducted by Fix (2003) suggested a significant correlation between playfulness and creativity as well as a frequent con- ceptual overlap between the two notions. Taylor and Rogers (2001) observed 164 children and used qualitative data to demonstrate that playfulness and creativity may occur jointly. Fix (2003) noted that the personal expression of playfulness has a significant influence on creativity. Liu (1994) cited a study by Barnett (1991) to suggest a positive correlation between play- fulness and infant creativity. The aforementioned research results indicate that creativity is closely connected to playfulness. Thus, on the basis of this research background, review of extant literature, and research goals, we propose the following research hypotheses: Hypothesis 1. Playfulness and creativity are correlated among students gifted in mathematics and science. Hypothesis 2. The playfulness of students gifted in mathe- matics and science predicts their creativity. Research Method Research Method This section is divided into discussions of the research scope and subjects, research tools, and data analysis. Research Scope and Subjec ts This study used questionnaires to investigate the playfulness and creativity of junior high school students who were gifted in mathematics and science. The data were analyzed using SPSS17.0 to explore the relationship between these constructs. 1) Pre-test subjects and sample design The scale used in this study was compiled and modified by scholars native to Taiwan. We distributed 67 pre-test question- naires to two classes of students with good grades in mathe- matics at two junior high schools in Tainan City. A total of 67 were retrieved, yielding a retrieval rate of 100%. The retrieved pre-test questionnaires were subjected to reliability and validity analyses before the official questionnaire was finalized. 2) Questionnaire and sample design This study selected junior high school students who were gifted in mathematics and science as research subjects via ran- dom sampling. A total of 360 questionnaires were sent to schools, and teachers were asked to assist in the testing; 342 questionnaires were retrieved, yielding a retrieval rate of 95%. After discarding 21 incomplete or invalid questionnaires, 321 valid questionnaires remained, reflecting a valid retrieval rate of 94%. Research Tools This study used two questionnaires as the primary measure- ment tools, the Personal Playfulness Scale and the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet. 1) Questionnaire content a) Personal playfulness scale The Personal Playfulness Scale used in this study was based on the Personal Playfulness Scale developed by Yu et al. (2003). It included 25 items that were divided into six dimensions: enjoyment of the process, taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems, relaxation in the service of free expres- sion, humor and ease with enjoyable experiences, having a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 103  C.-P. CHANG childlike sense of enjoyment and interest, and persevering until completion. This measure used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). Higher scores indicate greater playfulness. b) Williams creativity assessment packet To measure creativity, this study used the scale published by Psychology Publishing. This instrument includes 50 items ad- dressing adventurousness, curiosity, imagination, and dealing with challenges; it contains 42 positive items and eight negative items. The test uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). Items 4, 9, 12, 17, 29, 35, 45, and 48 are negative items. Thus, the maximum score is 250, and the minimum score is 50. Eleven items address ad- venturousness, 14 address curiosity, 13 address imagination, and 12 address dealing with challenges. 2) Pre-test results We based the Personal Playfulness Scale used in this study on our research framework, the related literature, and the extant Personal Playfulness Scale. To ensure the accuracy and validity of the scale, we used the pre-test to identify inappropriate items via reliability testing; these were then eliminated from the final questionnaire. a) Personal Playfulness Scale i) Item analysis SPSS17.0 was used for item analysis of the data obtained in the pre-test. This procedure identifies the critical ratios (CRs) of individual items on the questionnaire. Two indices of internal consistency (discrimination analysis and item-total score anal- ysis (homogeneity testing)) were employed for the item analy- sis of the pre-test questionnaire. We found that the 25 items had CRs greater than 3, and the modified total score–item correla- tions were all greater than .3. These results demonstrated the internal consistency of the questionnaire, and these 25 items were therefore retained. ii) Reliability analysis Reliability analysis relied on Cronbach’s α coefficients and showed internal consistency. The reliability of the scale was confirmed by correlational analyses, and the reliability coeffi- cient verified the scale’s internal consistency and stability. The pre-test of the Personal Playfulness Scale yielded an overall Cronbach’s α of .912, which indicated good internal consis- tency. b) Williams Creativity Assessment Packet i) Source Use of the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet (CAP) published by Psychology Publishing enabled this study to em- ploy the Creativity Assessment Packet developed by F. E. Wil- liams and modified by Hsing-tai Lin and Mu-rong Wang. This packet was designed for students between the fourth grade of elementary school and the third year of high school. Students with unique capabilities and creativity and those who were selected to participate in creativity-development projects or in educational projects targeted at gifted individuals were selected for inclusion. ii) Reliability and validity analysis The research norms were established with samples that had been stratified by the population and size of urban or rural loca- tions. In total, 2283 valid questionnaires were collected for “creative-thinking activities,” and 2294 were collected for “creative inclinations.” Norms for students from elementary to high school were established at the end of 1994. The internal consistency coefficients were .401 - .877; the test-retest reli- ability was .489 - .810; the inter-rater reliability was .878 - .992; all coefficients reached the .05 level of significance. Coefficients for the creativity scale were .550 - .909, which were all significant at the .001 level. The α values for compari- sons among dimensions were .624 - .801. Results This section presents the results of the data analysis, which was conducted using SPSS17.0. The analysis and discussion were focused on the research goals. Analysis of the Association of High Achievement in Mathematics and Science with Playfulness and Creativity 1) Descriptive analysis of demographic data of students with high achievement in mathematics The sample included 321 respondents in this category; 258 of these attended public schools (80.40%), and 63 attended private schools (19.60%). Seventy-seven were in the first grade (24.00%), 155 were in the second grade (48.00%), and 89 were in the third grade (27.70%); overall 179 were male (55.80%) and 142 were female (44.20%). 2) Current status of personal playfulness We used mean values and standard deviations to analyze the playfulness of students with high achievement in mathematics as assessed by the Personal Playfulness Scale; the results pre- sented in Table 1 range between 1 and 5 points. Students ranked their playfulness in terms of enjoyment of the process (mean = 4.64), persevering until completion (mean = 4.12), sense of humor and ease of enjoyment (mean = 4.08), childlike enjoyment and interest (mean = 3.96), relaxation in the service of free expression (mean = 3.84), and taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems (mean = 3.74). The highest mean score was for enjoyment of the process, and the lowest mean was for taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems. The overall mean was 4.11, which indicates that students were moderately inclined to engage in personal play- fulness. 3) Current status of creativity Means and standard deviations were used to analyze data on creativity in students with high achievement in mathematics as measured with the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet analysis. The results, shown in Table 1, range from a maximum of 5 points to a minimum of 1 point. According to Table 1, curiosity had the highest mean score at 3.92, dealing with chal- lenges had a mean score of 3.91, adventurousness had a mean score of 3.58, and imagination had a mean score of 3.41. Curi- osity had the highest mean score, and imagination had the low- est mean score. The overall mean was 3.71, which indicates a moderate degree of creativity among the students. Reliability Analysis of the Scale This study used Cronbach’s α coefficient in the reliability analysis to confirm the internal consistency, internal correla- tions, and stability of each scale. This questionnaire was divided into two portions. The reli- ability analysis for the first portion, which addressed personal playfulness, is presented in Table 2; the overall Cronbach’s α of this portion was .892. The reliability analysis for the second portion of the scale, which addressed creativity, showed a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 104  C.-P. CHANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 105 Table 1. Analysis of current personal playfulness and creativity. Dimension (personal playfulness) Mean Standard Deviations (Creativity ) Mean Standard Deviations Enjoyment in the process 4.64 .41 Adventurousness 3.58 .43 Happy to create and resolve problems 3.74 .7 Curiousness 3.92 .47 Relax oneself for free expression 3.84 .92 Imagination 3.41 .48 Humorous and at ease in enjoyment 4.08 .53 Challenging 3.91 .39 Childlike heart enjoys fun and interest 3.96 .8 Overall 3.71 .36 Persevering oneself until active completion 4.12 .73 Overall 4.11 .47 Table 2. Reliability analysis. Scale Cronbach’s α Personal playfulness .892 Creativity .877 Cronbach’s α of .877. Correlation Analysis This study used Pearson's product-moment correlations to analyze relationships between playfulness and creativity among students with high achievement in mathematics; these data are shown in Table 3. 1) Correlation between the overall construct of personal play- fulness and the overall construct of creativity Table 3 shows a significant correlation between the overall score on the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet, which measures the construct of personal playfulness and on the Per- sonal Playfulness Scale, which measures the overall construct of creativity (r = .742, p < .01). The significant positive corre- lation between the overall score for personal playfulness and that for creativity shows that high levels of personal playfulness were associated with high levels of creativity. Thus, hypothesis 1, that we would find a correlation between playfulness and creativity in students with high achievement in mathematics, was confirmed. 2) Correlation between the overall score for personal play- fulness and scores for aspects of creativity As shown in Table 3, the correlation coefficients between the overall score for personal playfulness and certain aspects of creativity (adventurousness, curiosity, imagination, dealing with challenges) were between .538 and .679, and all reached the level of significance. Thus, personal playfulness was posi- tively correlated with adventurousness, curiosity, imagination and dealing with challenges. Adventurousness (r = .679) showed the highest correlation, indicating that high levels of personal playfulness were associated with high levels of ad- venturousness. 3) Correlation between the overall score for creativity and elements of personal playfulness Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients between the over- all score for creativity and various aspects of personal playful- ness (enjoyment of the process, taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems, relaxation in the service of free expression, humor and ease of enjoyment, childlike enjoyment and interest, and persevering until completion), which ranged from .429 to .681; these values represent significant positive correlations for all pairs. Taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems (r = .681) was most strongly correlated with creativity, indicating that high levels of creativity were associated with taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems. Multiple Stepwise Regressions Scores for personal playfulness and for creativity among students demonstrating high achievement in mathematics were significantly positively correlated with each other. This section discusses the results of multiple regression analysis to under- stand whether personal playfulness can predict creativity. 1) Prediction of overall creativity on the basis of personal playfulness among students demonstrating high achievement in mathematics Table 4 showed that three of the potential predictor variables had significant (p < .001) predictive power for overall creativity; taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems, childlike enjoyment and interest, and relaxation in the service of free expression, in that order, accounted for 57.5% of overall variance. Taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems explained 46.4% of the variance and was the best predictor variable. The regression coefficients for taking pleas- ure in the creation and resolution of problems (β = .554), child- like enjoyment and interest (β = .235), and relaxation in the service of free expression (β = .191) indicated that they also had positive effects on overall creativity. Thus, hypothesis 2 (that the playfulness of students with high achievement in mathematics would predict creativity) was verified. Data from the regression analysis on the predictive power of personal playfulness with respect creativity are presented in Table 4. Table 5 shows that five variables have significant predictive ability (p < .001) with respect to adventurousness; they are (in order) taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of prob- lems, relaxation in the service of free expression, persevering until completion, enjoyment of the process, and humor and ease of enjoyment. The overall variance was 48.3%, and the dimen- sion of taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of prob- lems was the best predictor of adventurousness, explaining 32.4% of the variance. The regression coefficients for taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems (β = .325), relaxation in the service of free expression (β = .205), perse- vering until completion (β = .172), enjoyment of the process (β = .132), and humor and ease of enjoyment (β = .114) also re- flected their positive effects on adventurousness.  C.-P. CHANG Table 3. Analysis of personal playfulness and creativity. Variable Adventurousness Curiousness Imagination Challenge Overall Enjoyment in the process .451** .387** .310** .369** .459** Happy to create and resolve problems .569** .641** .457** .560** .681** Relax oneself for free expression .507** .361** .403** .436** .514** Humorous and at ease in enjoyment .467** .394** .337** .464** .500** Childlike heart enjoys fun and interest .373** .321** .377** .334** .429** Persevering oneself until active completion .467** .362** .372** .439** .494** overall .679** .602** .538** .628** .742** Note: **The level of significance was set at .01 (two-tailed). Table 4. Regression analysis of the predictive power of personal playfulness on overall creativity (n = 321). Variable Multiple correlation coefficient Coefficient of determination R squared Increased explained variance (%) F changeOriginal regression coefficient (β) Standardized regression coefficient (β) Happy to create .681 .463 .464 276.57.288 .554 Childlike heart .741 .547 .085 60.28 .107 .235 Relax oneself .759 .576 .026 19.27 .076 .191 Table 5. Regression analysis for personal playfulness and adventurousness (n = 321). Variable Variable Variable Variable Variable Variable Variable Create .569 .322 .324 152.78 .199 .325 Relax oneself .643 .413 .09 48.608 .096 .205 Persevering oneself .676 .451 .043 25.064 .101 .172 Enjoyment in the process .689 .468 .018 10.779 .138 .132 Humorous and at eas .694 .474 .008 4.681 .075 .114 Table 6 shows that three variables had significant (p < .001) predictive ability with respect to curiosity; these were (in order) taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems, childlike enjoyment and interest, and enjoyment of the process. The overall variance was 45.6%; taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems explained 41.1% of the variance making it the primary predictor variable. The regression coeffi- cients for talking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems (β = .564), childlike enjoyment and interest (β = .164), and enjoyment of the process (β = .109) also reflected positive effects on curiosity. Table 7 shows that four variables showed significant (p < .001) predictive ability for curiosity; they were (in order) taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems, childlike enjoyment and interest, relaxation in the service of free expression, and persevering until completion. The overall variance was 32.1%, and taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems was the strongest predictor of imagina- tion, explaining 20.9% of the variance. The regression coeffi- cients for taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems (β = .311), childlike enjoyment and interest (β = .199), relaxation in the service of free expression (β = .154), and per- severing until completion (β = .112) also indicated positive effects on imagination. Table 8 shows that three variables had significant (p < .001) predictive ability with respect to dealing with challenges; they were (in order) taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems, humor and ease in enjoyment, and persevering until completion. The overall variance was 42.5%, and the taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems explained 31.4% of the variance, making it the primary predictor variable. The regression coefficients for taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems (β = .383), humor and at ease in enjoyment (β = .246), and persevering until completion (β = .220) also showed positive effects on adventurousness. Research Hypotheses, Analysis, and Discussion The previous six sections discussed and analyzed data related to the confirmation of the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1. The playfulness and creativity of students gifted in mathematics and science would be correlated with each other. This hypothesis was confirmed. Hypothesis 2. The playfulness of students gifted in mathe- matics and science would be predictive of their creativity. This hypothesis was confirmed. Analysis of Aspects of Playful ne ss This analysis of scores on the playfulness measure produced an overall mean of 4.11, with he means of various aspects t Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 106  C.-P. CHANG Table 6. Regression analysis of personal playfulness and curiosity (n = 321). Variable Multiple correlation Coefficient Coefficient of determination R squared Increased explained variance (%) F change Original regression coefficient (β) Standardized regression coefficient (β) Happy to create .641 .409 .411 222.53 .377 .564 Childlike heart .669 .444 .036 20.771 .096 .164 Enjoyment in the process .675 .451 .009 5.339 .124 .109 Table 7. Regression analysis of personal playfulness an imagination (n = 321). Variable Multiple correlation Coefficient Coefficient of determination R squared Increased explained variance (%) F change Original regression coefficient (β) Standardized regression coefficient (β) Happy to create .457 .206 .209 84.18 .216 .311 Childlike heart .54 .287 .083 37.068 .121 .199 Relax oneself .558 .305 .02 9.404 .082 .154 Persevering oneself .566 .312 .009 4.138 .074 .112 Table 8. Regression analysis of personal playfulness and challenge (n = 321). Variable Multiple correlation Coefficient Coefficient of determination R squared Increased explained variance (%) F change Original regression coefficient (β) Standardized regression coefficient (β) Happy to create .56 .312 .314 145.83 .216 .383 Humorous and at eas .621 .381 .071 36.94 .15 .246 Persevering oneself .652 .42 .04 22.28 .119 .22 ordered as follows: enjoyment of the process (mean = 4.64), persevering until completion (mean = 4.12), humor and ease of enjoyment (mean = 4.08), childlike enjoyment and interest (mean = 3.96), relaxation in the service of free expression (mean = 3.84), and taking pleasure in the creation and resolu- tion of problems (mean = 3.74). The highest mean was associ- ated with enjoyment of the process and the lowest was associ- ated with taking pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems. Overall, these data indicate that students were mod- erately inclined toward playfulness. The overall mean on the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet was 3.71, and the aspects of creativity were ranked as follows: curiosity (mean = 3.92), challenge (mean = 3.91), ad- venturousness (mean = 3.58), and imagination (mean = 3.41). The most highly ranked aspect was curiosity, and imagination received the lowest ranking. Overall, these data indicate that students demonstrated a moderate degree of creativity. The Playfulness and the Creativity of Students with High Achievement in Mathematics Were Correlated with Each Other Substantial evidence of a relationship between play and crea- tivity has been found with respect to common behavioral and contextual influences (Dansky, 1980; Perpler & Ross, 1981; Singer & Rummo, 1973). In the United States, Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford, who were known for their creative contributions to society, were highly playful individu- als (John-Steiner, 1985). The first research goal of this study was to explore the corre- lation between the playfulness and the creativity of students demonstrating high achievement in mathematics. This goal was met by data showing a significant positive correlation between the overall scores for playfulness and those for creativity (r = .742, p < .01). The correlations between overall scores for personal playfulness and various aspects of creativity were between .538 and .679, and all reached the level of significance. The correlation coefficients for the relationships between the overall scores for creativity and various aspects of personal playfulness were between .429 and .681, and all reached the level of significance. This study verified that playfulness is indeed beneficial for individual creative performance, which is consistent with much previous research (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, 1997; Glynn, 1988; Webster, 1989). Additionally, Taylor and Rogers’ (2001) qual- itative study of 164 children found that playfulness and creativ- ity may occur at the same time, and the studies conducted by Barnett (1991) and Taylor (1992) reported a positive correlation between playfulness and creativity. In other words, those with high playfulness, who frequently demonstrate behavior reflect- ing freedom, voluntary action, enthusiasm, happiness, humor, and joy and who bring an interesting and playful attitude to work and relationships demonstrated greater creativity. Thus, schools and teachers should offer some degree of flexibility and freedom, provide help with dealing with failure, cultivate play- fulness, and nurture the expression of humor in the classroom to enhance the creativity of students showing high achievement in mathematics. In the past, Chinese society has held a negative Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 107  C.-P. CHANG view of playfulness, believing that “play diminishes ambition,” “work improves with practice and deteriorates with play,” or that play is bad and not serious. In the modern era, which val- ues creativity, we should consider play to be a serious matter and address the issues entailed in the question of how to engage in creative play while avoiding the negative effects of playful- ness. The Playfulness of Students with High Achievement in Mathematics Can Predict Their Creativity Personal playfulness can predict and have a positive influ- ence on creativity; personal playfulness explained the variance in the overall scores for creativity and its dimensions as follows: 57.5% of the variance in overall scores for creativity, 48.3% of the variance in adventurousness, 45.6% of the variance in curi- osity, 32.1% of the variance in imagination, and 42.5% of the variance in dealing with challenges. These data show that per- sonal playfulness can be used to predict creativity. This finding is consistent with that reported by Wang (2007), who conducted research on 394 third- and fifth-grade elemen- tary school students and found that playfulness was an impor- tant variable that affected technological creativity. It is also consistent with the study conducted by Fix (2003), who re- ported that individual playfulness had a significant effect on creativity. Thus, relaxation and free expression have an effect on overall creativity. At present, although the Taiwanese edu- cational system no longer emphasizes rote learning, the empha- sis on academic advancement remains. Students still experience massive amounts of academic stress and feel highly anxious, which frequently decreases their playfulness. The creation of interesting and lively educational environments without undue spatial restrictions or the organization of regular activities or competitions that facilitate creativity and relaxation should promote joyful learning and free thinking, which should greatly enhance students’ creativity. Conclusion This study initially reviewed the extant relevant literature, integrated different concepts of creativity, and noted that crea- tivity consists of fluency, flexibility, originality, the ability to elaborate, and so on. Students in this study demonstrated moderate overall play- fulness; they were most likely to enjoy the process of creativity and least likely to take pleasure in the creation and resolution of problems. They also demonstrated a moderate degree of crea- tivity, and among the elements of creativity, they were most likely to show curiosity and least likely to show imagination. This finding is more specific than those of past studies in terms of the individual variables contributing to students’ playfulness and creativity. Additionally, most previous studies focused on the behaviors of children. This study broke with that tradition by extending the focus to students who were gifted in mathematics and sci- ence. Based on Glynn and Webster’s (1992) theory of adult playfulness, we further integrated and developed the Personal Playfulness Scale for use in this study. However, few studies have focused on understanding how playfulness is related to creativity. Indeed, no previous studies have analyzed the con- nection between playfulness and creativity among students gifted in mathematics and science. This research was novel in its attempt to analyze the relationship between playfulness and creativity among students gifted in mathematics. In conclusion, the results indicate that creativity is enhanced in the context of playfulness. The playfulness and creativity of this sample of students with high achievement in mathematics were positively correlated. Playfulness has direct predictive power in relation to students’ creativity. REFERENCES Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity. New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5533-8 Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in or- ganizations. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 10, pp. 123-167). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Oxford: West View Press. Barnett, L. A. (1990). Playfulness: Definition, design and measurement. Play & Culture, 31, 319-336. Barnett, L. A. (1991). Characterizing playfulness: Correlates with indi- vidual attributes and personality traits. Play and Culture, 4, 371-393. Cropley, A. J. (2000). Defining and measuring creativity: Are creativity tests worth using? Roeper Review, 23, 8. doi:10.1080/02783190009554069 Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Fran- cisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Perennial. Dansky, J. L. (1980). Make-believe: A mediator of the relationship between play and associative fluency. Child Development, 51, 576- 579. doi:10.2307/1129296 Davis, G. A., & Rimm, S. B. (1994). Education of the gifted and tal- ented. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Feldhusen, J. F., & Jarwan, F.A. (1993). Identification of gifted and talented youth for educational programs. In K. A. Heller, F. J. Monks, & A. H. Passow (Eds.), International handbook of research and de- velopment of giftedness and talent. Oxford: Pergamon Press Ltd. Fix, G. A. (2003). The psychometric properties of playfulness scales with adolescents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Fairleigh Dickinson. Glynn, M. A. (1988). The perceptual structuring of tasks: A cognitive approach to understanding task attitudes and behavior. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, New York: Columbia University. Glynn, M. A., & Webster, J. (1992). The adult playfulness scale: An initial assessment. Psychological Reports, 71, 83-103. doi:10.2466/pr0.1992.71.1.83 Guilford, J. P. (1965). Fundamental statistics in psychology and educa- tion. New-York: McGraw-Hill. Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligent. New York: McGraw-Hill. John-Steiner, V. (1985). Notebooks of the mind: Exploring of thinking. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Kanter, R. (1988). When a thousand flowers bloom: Structural, collec- tive, and social conditions for innovation in organizations. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behav- ior (Vol. 10, pp. 169-211). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Kirton, M. (1976). Adaptors and innovators: A description and measure. Journal of Applied P s y c h o l og y , 61, 622-629. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.61.5.622 Kuo, C. C. (2000). Identifying gifted students who will benefit from accelerated education. Monthly Release of Gifted Education, 76, 1-6. Lieberman, J. N. (1976). Playfulness: Its relationship to imagination and creativity. Waltham, MA: Academic Press. Lieberman, J. N. (1977). Playfulness. New York: Academic Press. Liu, H. C. (1994). The study of relationship between young children’s playfulness and peer play. Chinese Culture University Graduate In- stitute of Child Welfare. Lofland, A. (1993). Mathematics and gender: An analysis of student attitudes toward mathematics at the University of Hawaii, Manona Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 108  C.-P. CHANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 109 Compous. Dissertation Abstracts Interna tional, 53, 235-253. Pepler, D., & Ross, H. (1981). The effect of play on convergent and divergent problem-solving. Child Development, 52, 1202-1210. doi:10.2307/1129507 Rogers, E. (1983). Diffusion of innovations (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press. Rogers, C. S., & Sluss, D. J. (1999). Play and inventiveness: Revisiting Erikson’s views on Einstein’s 36 playfulness. Play and Cultural Studies: Play Cont exts Revisited, 2, 3-24. Runco, M. A. (2007). Achievement sometimes requires creativity. High Ability Studies, 18, 3. doi:10.1080/13598130701350791 Shalley, C. E. (1991). Effects of productivity goals, creativity goals, and personal discretion on individual creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 179-185. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.179 Singer, J., & Rumons, J. (1973). Ideational creativity and behavioral styles in kindergarten age children. Developmental Psychology, 8, 154-156. doi:10.1037/h0034155 Starbuck, W. H., & Webster, J. (1991). When is play productive? Ac- counting, Management, and Information Technolo g y , 1, 71-90. doi:10.1016/0959-8022(91)90013-5 Sternberg, R. J. (2001). What is the common thread of creativity: It’s dialectical relation to intelligence and wisdom. American Psycholo- gist, 56, 360-362. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.4.360 Sternberg, R. J., & Davidson, J. E. (1986). Conceptions of giftedness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Taylor, S. I. (1992). The relationship between playfulness and creativity of Japanese preschool children. Unpublished Doctorate Dissertation, Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Taylor, S. I., & Rogers, C. S. (2001). The relationship between play- fulness and creativity of Japanese preschool children. International Journal of Early Childhood, 33, 43-49. doi:10.1007/BF03174447 Wang, H. H. (2007). The relationships among reading environment, playfulness, creative parenting and technological creativity of the third and fifth graders. Tainan: National Chengchi University Gradu- ate Institute of Early Childhood Education. Webster, J. (1989). Playfulness and Computers at work. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, New York: New York University. Webster, J., & Martocchoio, J. J. (1992). Microcomputer playfulness: Development of a measure with workplace implications. MIS quar- terly, 16, 201-227. doi:10.2307/249576 Wei, L. M. () The effects of self-regulated learning and affective factors on mathematics achievement of primary students and the effective- ness of strategies training. Doctoral Dissertation, Taipei City: Na- tional Taiwan Normal University Graduate Institute of Education Psychology and Counseling. Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18, 293-321. doi:10.5465/AMR.1993.3997517 Woszczynski, A. B., Roth, P. L., & Segars, A. H. (2002). Exploring the theoretical foundations of playfulness in computer interactions. Com- puters in Human Behavior, 1 8, 369-388. doi:10.1016/S0747-5632(01)00058-9 Wu, K. S. (2006). Guided independent study of gifted students. Journal of Education Research, 143, 71-81. Yu, P. (2004). Enjoy fun at work: An explorative study of organiza- tional playfulness. Kaohsiung Normal University Journal, 6, 19-37. Yu, P. (2005). Facilitating playfulness at work. Research in Applied Psychology, 26, 73-94. Yu, P., Wu, J. J., Lin, W. W., & Yang, C. H. (2003). The development of adult playfulness scale and organizational playfulness climate questionnaire. Psychological Testing of Chinese Association of Psy- chological Testing, 50, 73-110. Zaltman, G., Duncan, R., & Holbek, J. (1973). Innovations and or- ganizations. London: Wiley.

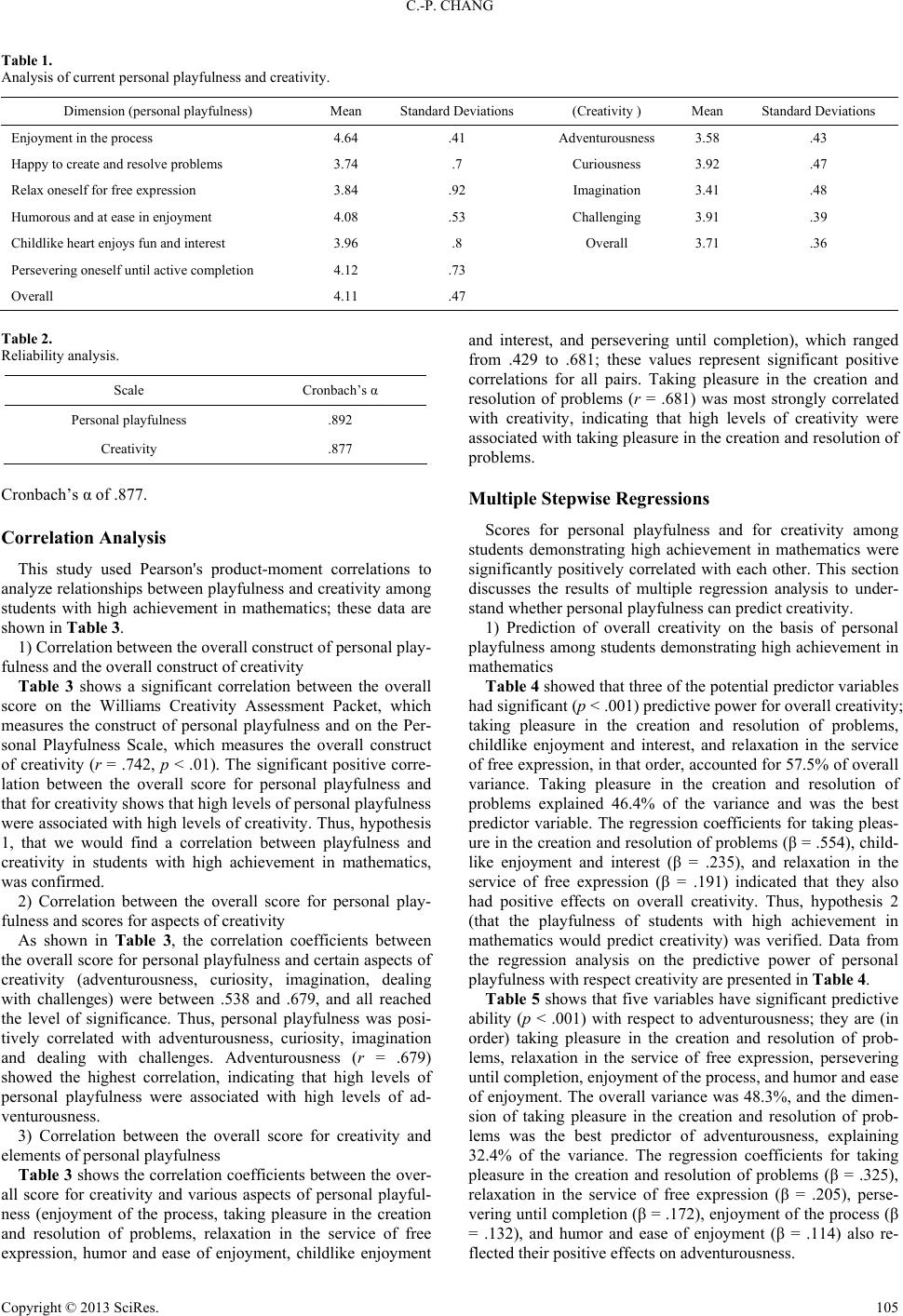

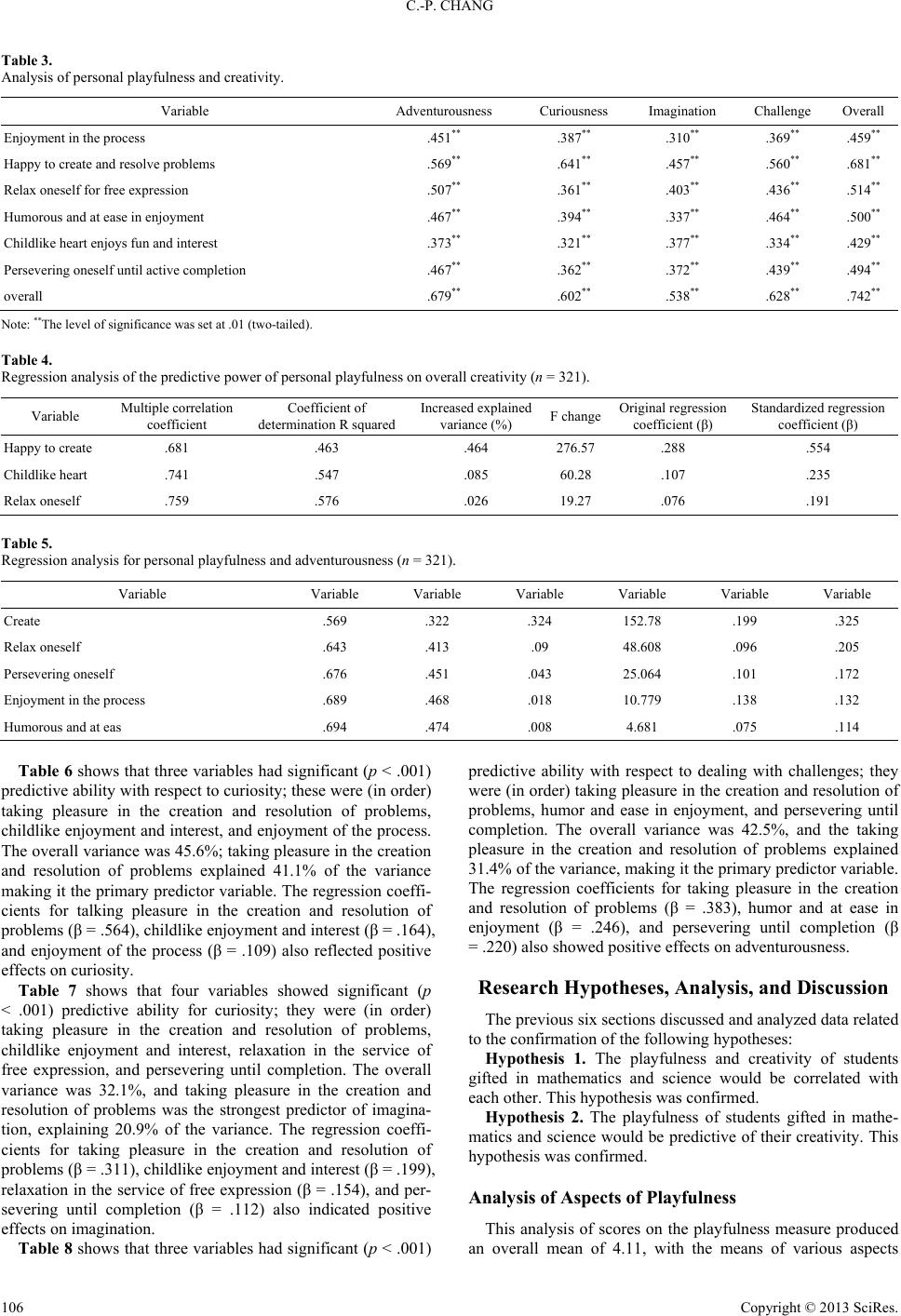

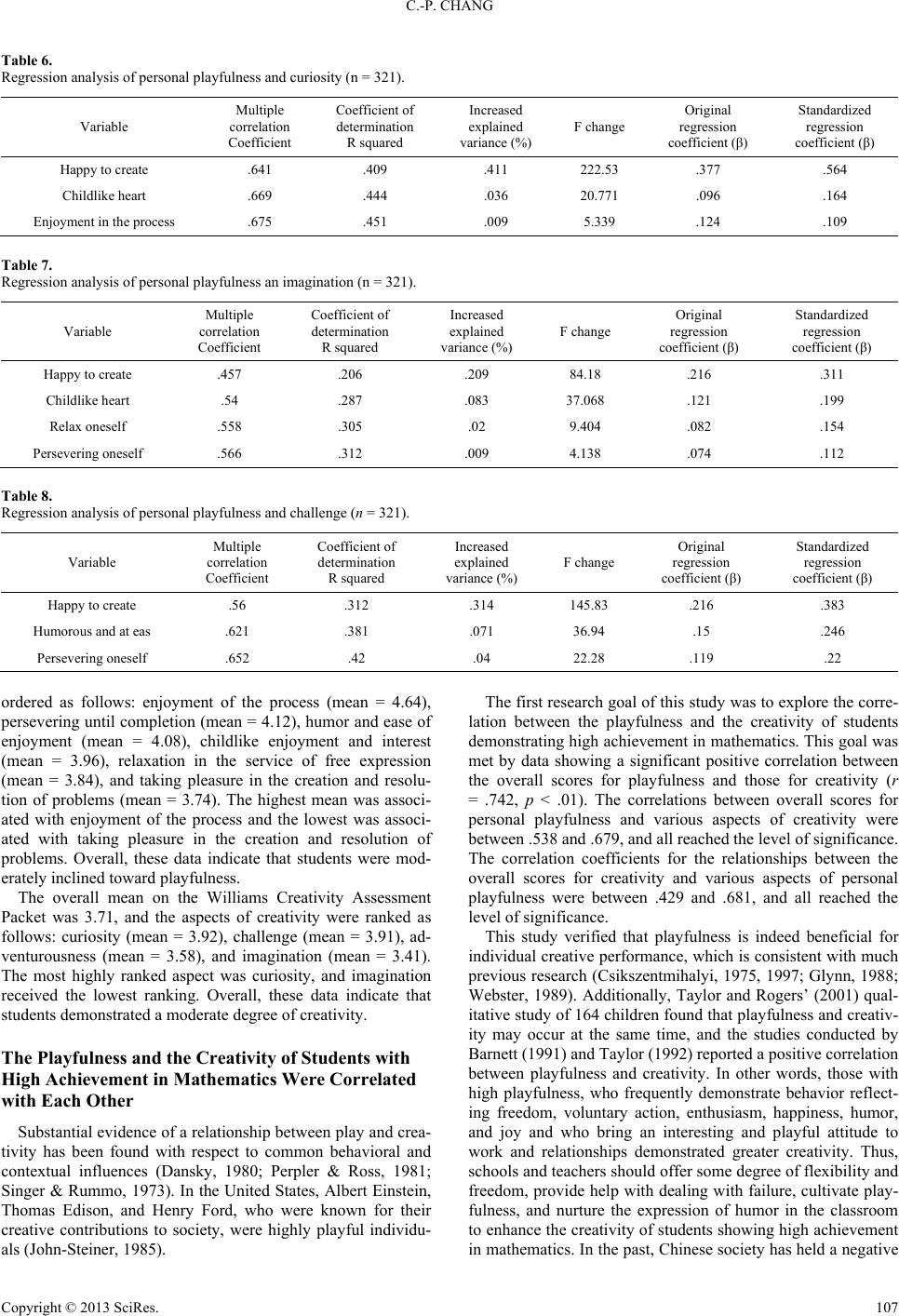

|