Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

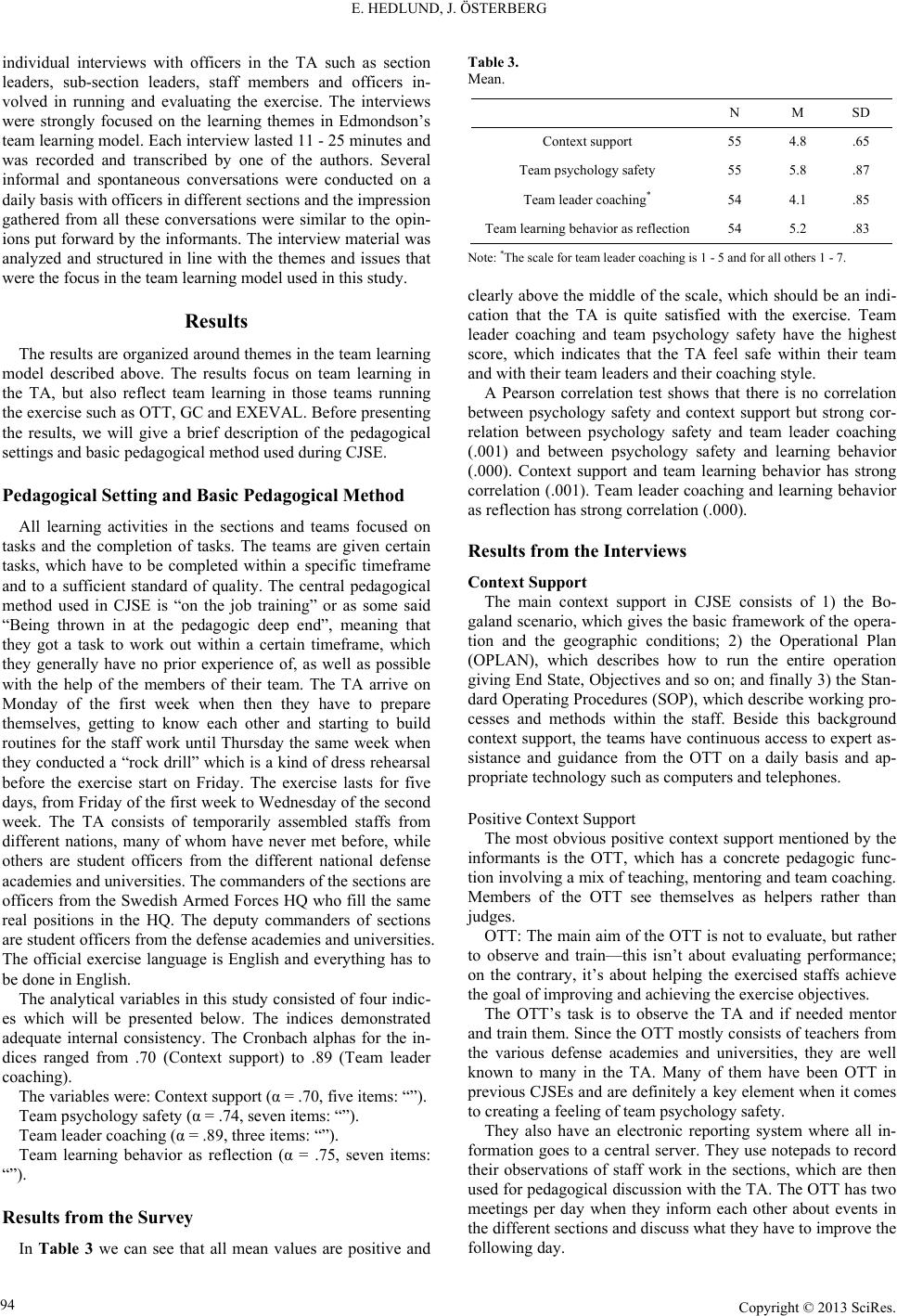

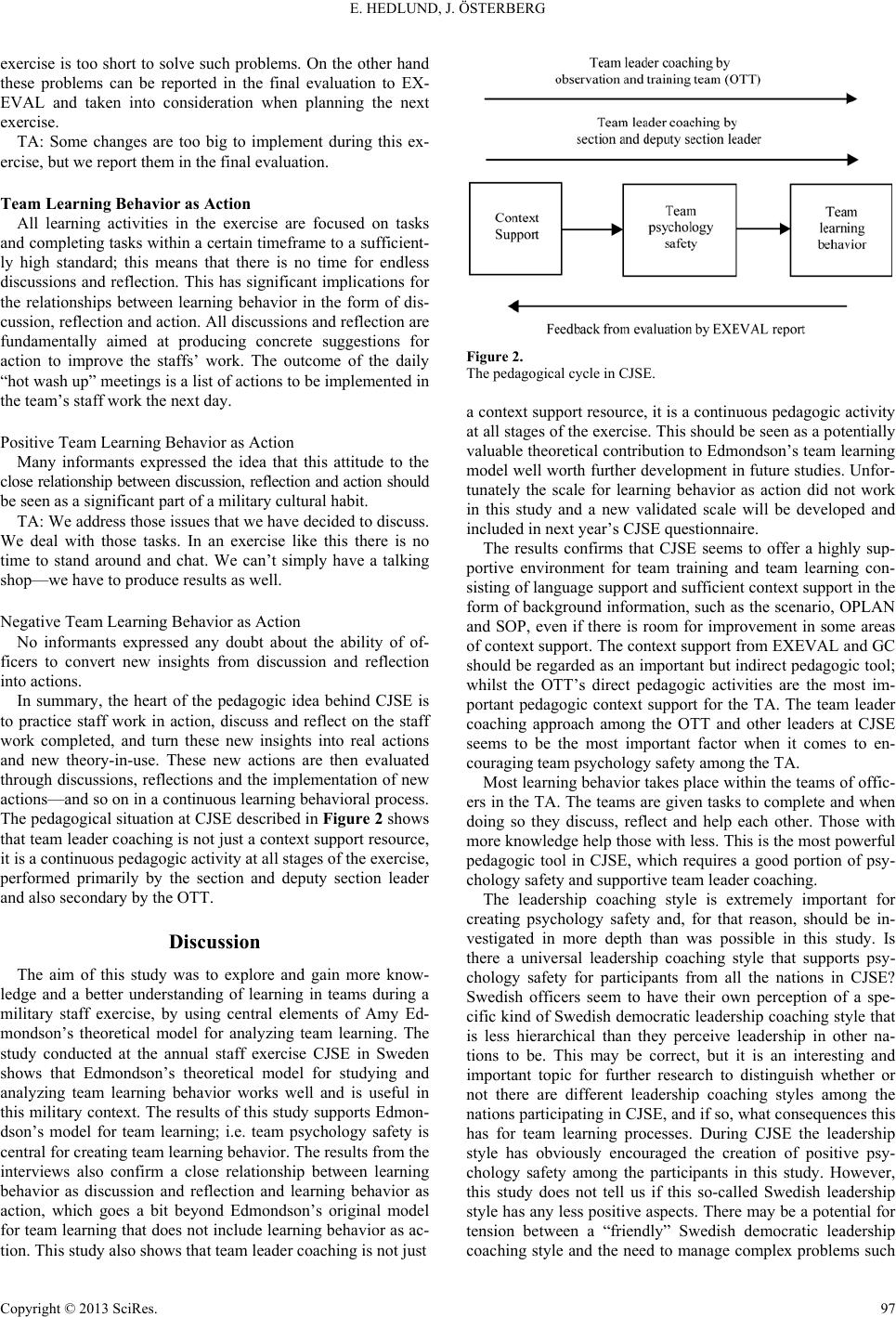

Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 89-98 Published Online January 2013 in S ci Res (http://ww w.scirp.org/journal/sm) DOI:10.4236/sm.2013.31014 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 89 Team Training, Team Learning, Leadership and Psychology Safety: A Study of Team Training and Team Learning Behavior during a Swedish Military Staff Exercise Erik Hedl und, Johan Österberg The Swedish National Defence College, Stockholm/Karlstad, Sweden Email: erik.hedlund@fhs.se, johan.osterberg@fhs.se Received October 10th, 2012; revised November 21st, 2012; accepted December 11th, 2012 The critical dependence of armed forces on teams carrying out tasks in a continuously changing, uncertain and often dangerous environment, raises questions about how to better understand factors that enable or hamper effective team learning. So far there is no developed field of research into team learning in the Swedish Armed Forces. This is the first of several studies within the Swedish Armed Forces to explore and gain a better understanding of team learning. In this first study of team learning we followed a mili- tary staff exercise. The theoretical base in this study is Amy Edmondson’s theoretical model for studying and analyzing team learning. The model consists of context support, team leader coaching, team psy- chology safety and team learning behavior. The results of this study supports the theoretical model of team learning and describe factors that are important for creating good conditions for team learning beha- vior. Keywords: Team Learning; Context Support; Team Leader Coachi ng; Psychology Safety; Learning Behavior Introduction The critical dependence of armed forces on teams carrying out tasks in a continuously changing, uncertain and often dan- gerous environment, raises questions about how to better un- derstand factors that enable or hamper effective team learning in organizations. Learning in organizations has been explored for several decades (e.g. Argyris & Schön, 1978; Hayes et al., 1988; Levitt & March, 1988; Stata, 1989; Senge, 1990; Schein, 1993; Garvin, 2000) and is related to the concept of collective learning, which is quite a broad term that refers to learning between dyads, teams, organizations, communities of practi ces, and societies. There are many suggestions and examples of how to study phenomena linked to conceptions of collective learning (McCarthy & Garavan, 2008) and team training such as task or team work processes and team performance (Salas et al., 2008). Most concepts of collective learning include organizational learning (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Senge, 2006; Gavin, 2006), team learning (Edmondson, 1999/2002; McCarthy & Garavan, 2008; Senge 2006) collective strategic leadership (Vera & Crossan, 2004) communities of practice (Wenger, 199 8; Brown & Duguid, 2001) and organizational-led collective learning (Thomas, Sussman, & Henderson, 2001). The basic interest in organizational learning and team learn- ing stems from the idea that organizations can develop and improve their actions and performance by learning from pre- vious and current work actions. According to Fiol & Lyles (1985) and Garvin (2000) organizational learning is a process of improving and changing organizational actions through bet- ter knowledge, whereas or Argyris & Schön (1978) say that organizational learning occurs when members of the organiza- tion detect and correct errors in organizational theory-in-use, and embed the results in private images and shared maps of organization. This means that an organization learns when its actions are modified through discussion and reflection on new knowledge or insights (Edmondson, 2002) i.e. not when organ- izations only gain new knowledge, without taking new actions. Therefore, an essential element of organizational learning is the interplay between discussion, reflection and action. Discussion and reflection include behavior such as sharing information, seeking feedback, discussing errors, and analyzing past perfor- mance, while actions are decisions, changes, improvement, implementation of new ideas, and transferring new information within the organiza tion that actually fallout as a result of change s to theory-in-use. Although literature on organizational learning is emerging, there is little knowledge about how successful organizations are at learning (Edmondson, 2002; Senge, 2006). Team learning is poorly understood and will remain somewhat mysterious until there is robust theory about what happens when teams learn (Senge, 2006). In this study we will take a group level perspective on inter- personal process es that influence organiza tional learning thro ugh actions and interactions between people working in small teams. A substantial amount of work is carried out by teams in organ- izations (Osterman, 1994) and the context for organizational learning is often a team. Teams can be viewed as the funda- mental learning unit in an organization and team learning is a process of aligning and developing the capacity of teams to im- prove their performance and results (Senge, 2006). Teams are important in that individual team members’ cognition and beha- vior are shaped by the social influences of the attitudes and behavior of other team members with whom they work closely (Argyris, 1982; Argyris & Schön, 1978; Hackman , 1992; Salanick &  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 90 Pfeffer, 1978). By studying teams that make appropriate cha nges to their work and actions, as a consequence of discussion and reflections on their work processes and performance, it should be possible to study team learning. Like all kinds of learning, team learning requires training and practice. Military staff exercises are practice and can be seen as a central pedagogic training program in the armed forces’ stra- tegy for organizational and team learning, which aims to im- prove the individual competence of officers, as well as the col- lective competence of teams and the organization itself. In the military and many other sectors, such as healthcare and aviation, team training is a common tool used to develop and improve teamwork and team performance. Through team training, teams and individuals are supposed to improve their knowledge, skills, and attitudinal competences (KSA) as well as team processes and performance (Salas et al., 2008). Teams can improve their communication skills, decision processes, decision making and their ability to deal with and perform under stress. Team train- ing is aimed at improving task work, teamwork and process skills (Goldstein & Ford, 2002). Team learning is built on shared visions and personal mastery, but what really matters is that the team can play together (Senge, 2006). Team learning can be defined as a process in which a team takes action, obtains and reflects upon feedback and makes changes to adapt or improve (Argote et al., 2000; Argyris, 1982; Argyris & Schön, 1972; Edmondson, 1999; Senge, 2006). Stu- dying team learning is not the same as studying organizational or individual learning; it is another level of analysis. While organizational learning is on a macro level and individual learning is on a micro level, team learning is a meso level ap- proach to organizational learning (Edmondson, 1999). Team learning at the meso level may not translate into the organiza- tional macro level. Often groups fail to communicate with oth- ers in the organization (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992), or are una- ble to convince others in the organization to adopt new ways of working (Roth & Kleiner, 2000). Research also shows that instituting new work practices in one part of an organization can give rise to a phenomenon whereby other or ganizational groups’ envy of the success of one group can lead to other groups rejecting the changes (Walton, 1975). Individual level theories point to the limited effects in- dividual learning has on effective organizational change. Indi- viduals also tend to hold tacit theories (“theories-in-use”) that disable their own and others learning (Argyris & Schön, 1978). Organizational learning often remains locally driven by the goals and concerns of individuals, groups and teams rather than serving organizational goals (Edmondson, 2002). Learning in teams is driven by interpersonal perceptions and concerns; a lack of psychology safety in these teams can inhibit experi- menting, admitting mistakes, or questioning current team prac- tices (Edmonton, 1999). Team learning breaks down when teams fail to reflect on their own actions or when they do reflect, but fail to make changes following discussion and reflection. Team learning can be of two different types—exploitation and exploration (March, 1991); first and second order learning (Lant & Mezias, 1992); single and double-loop learning (Argy- ris, 1982); Learning I and Learning II (Bateson, 1972), incre- mental and radical learning (Miner & Mezias, 1996). The for- mer is characterized by improving existing routines or capabili- ties and the latter by reframing a situation, developing new capabilities, or solving ambiguous problems. Since team learning is a fundamentally collective process, aiming to improve the competence of both the individual and the team, there is a need for a process that makes it possible to tap the potential for many minds to be more intelligent than one mind (Senge, 2006). According to Senge (2006), this process is the dialog. The purpose of a dialog is to go beyond any one individual’s understanding to gain access to a larger “pool of common meaning” which cannot be accessed individually. In dialog, contrary to discussion, people are not in opposition and no one strives to win, everyone is a winner. In dialog the team explores complex issues from many points of view and indi- viduals gain insights that could not be achieved individually. Dialog is playful and requires a willingness to play with new ideas, to examine them and test them. Some basic conditions for a genuine and fruitful dialog are that individuals must re- gard one another as equals, suspend their assumptions and communicate their assumptions freely with the aim of bringing the full depth of people’s experience and thought to the surface, and there must be a facilitator who has the ability to create and support a culture of free flow of meaning within the team (Senge, 2006). However, according to Argyris (1999, 1990, 1982), there are threats to genuine dialog where teams trap themselves in “defensive routines”. Defensive routines are en- trenched habits we use to protect ourselves from the embar- rassment and threat that may come from exposing our think- ing—a protective shell around our deepest assumptions. The source of defensive routines is fear of exposing the thinking that lies behind our views because we are afraid that people will find errors in it. Defensive routines can be a strategy for teams to avoid conflict within the team and team members might be- lieve that they must suppress their conflicting views in order to maintain a “smooth surface” to the team. Even when team members share a common vision, they might ha ve diffe rent ideas about how to achieve that vision. A free flow of conflicting ideas is a necessary condition for critical, reflective and creative dialog. Conflicts are thus a natural part of an ongoing dialog. By using defensive routines, teams insulate their mental models and assumptions from examination; this will result in the de- velopment of a “skilled incompetence” to learn and the team remains incompetent at improving its performance and produc- ing high quality results. Defensive routines are so diverse and so commonplace that they usually go unnoticed (Senge, 2006). In this study we will use a model for team learning devel- oped by Amy Edmondson that focuses on team learning as a process, which can be studied and analyzed in terms of context support, team leader coaching, team psychology safety and team learning behavior (Edmondson, 1999). Team learning is a process of discussion, reflection and action that serves as an incremental learning goal (being better at what you are already doing) and/or a radical learning goal (doing things in a new way). Both are essential for effective organizational learning and adaptation. In a study focusing on team learning, a signifi- cant indicator of learning is when discussion and reflection brings about changes in actions, routines and theory-in-use (Argyris & Schön, 1978). The Aim of the Study So far there is no developed field of research into team learning in the Swedish Armed Forces. This is the first of sev- eral studies within the Swedish Armed Forces to explore and gain a better understanding of team learning. In this first study on team learning we are following a military staff exercise.  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 91 There are many different definitions of teams, but in this study of military staffs we found the definition by Salas et al. (Salas et al., 1992: p. 906) very appropriate. “Teams are a set of two or more individuals who interact dynamically, adaptively, and interdependently; who share common goals or purpose; and who have specific roles or functions to perform.” This defini- tion and features of teams coincide very well with the features and functions of a military staff team. The teams in military staff exercises are traditionally structured in sections with clearly defined tasks, membership, and shared responsibility. Team training and team learning can consist of learning a s a n outcome (Lewitt & March, 1988: p. 320) or as a process of de- tecting and correcting errors (Argyris & Schön, 1978) aiming at adaptation, change, developing shared knowledge and skills, at- titudes and improvements in actions and performance1. In this study we will use the central elements of Amy Edmondson’s theoretical model for studying and analyzing team learning. The model consists of context support, team leader coaching, team psychology safety and team learning behavior. In this study we only focus on how context support, team leader coaching and team psychology safety will affect team learning behavior, i.e. we are not studying the performance or outcome of the staff work. The major reason for this is that the purpose of this staff exercise is simply individual and team learning and team learning behavior—so there are no developed instruments or criteria for evaluating performance or outcome. In future studies our intention is to follow the whole process from context support, through team leader coaching, team psy- chology safety and team learning behavior, to team perfor- mance and out come. A Model of Team Learning Context Support Context support concerns resources that enable the team to accomplish their task effectively and to a high degree of quality. Context support includes adequate resources and appropriate technology; it also includes open, sufficient and correct infor- mation to enable the team to accomplish their task. It includes readily available expert assistance when situations arise that the individual or team is unable to deal with. Furthermore, good context support provides good opportunities to learn on the job, which, combined with supportive team leader behavior, such as coaching and direction, have been shown to support team psy- chology safety (Edmondson, 1999) and increase team effective- ness (Hackman, 1987; Wageman, 1988). Context support had both quantitative and qualitative results indicating that context support has an impact on variations in learning behavior, but it does not give a complete explanation (Edmondson, 1999). High-learning teams were initially less dependent on appropriate context support and possessed team strengths that helped them to confront, work with, improve, and overcome context support obstacles. In contrast, low-learning teams that lacked appropriate context support were far more likely to get stuck and be unable to improve and alter their con- text support situation without external intervention. Team Leader Coaching The team leader is probably the most significant person when it comes to creating an atmosphere and learning culture that promote team learning behavior. Team leader behavior and coaching style is a salient and important influence on team psychology safety. The team members are particularly aware of the behavior of the leader (Tyler & Lind, 1992). If the leader is supportive, coaching oriented and responds positively to ques- tions and challenges, it will enhance psychology safety, which in turn will support learning behavior. The team leader is, or at least should be, a role model that sets standards within the team. Team leaders that encourage team members to ask for help if they are unable to solve a problem, to reveal and discuss errors, and have an open minded approach to discussing and solving problems, will create a culture of team psychology safety. If, on the other hand, team leaders act in an authoritarian and punitive manner, it can create a team culture of insecurity, resulting in team members tending to act in ways that inhibit learning when they face the possibility of threat and embarrassment (Argyris, 1982). Edmondson’s study (2002) revealed that in teams in which discussion, reflection and change occurred, power dis- tances (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005) were either absent or nar- rowed by the leader. Team leaders who could mitigate the po- tential for fear, due to their relative power over team members, might elicit a more fruitful learning environment. Team leaders can also encourage and enhance team learning behavior by having an explicit strategy and operational plan for implementing and accomplishing activities, which aim to make team learning a systematic, planned intervention designed to facilitate the acquisition of job-related KSAs (Goldstein & Ford, 2002) focused on improving how individuals work together effectively as a team. Team learning behavior includes such activities as continuously seeking improvement, lessons learned, mutual performance monitoring, feedback, communication, co- ordination, and decision making (Cannon-Browers et al., 1995; Stagl, Salas, & Fiore, 2007). Such behavior also requires atti- tudes that support dialog and open communication and colla- borative learning, i.e. using the team members as a source of knowledge for the rest of the team (Bresó, Gracia, Latorre, & Peiró, 2008). A good team leader must be a facilitator who holds the context of the dialog (Senge, 2006). Team Psychology Safety Team learning behavior depends strongly on team psycholo- gy safety. A team level perspective calls for attention to group processes and perceptions of interpersonal risk in hindering team learning. Edmondson (1999) defines team psychology sa- fety as a shared belief about the consequences of interpersonal risk-taking, i.e. when team members feel safe or unsafe about interpersonal risk-taking. Within a team there is often a general, tacit belief and sense of confidence that team members will not attack, embarrass, reject, punish or bully each other when speaking up or admitting errors. There is a mutual confidence that stems from mutual respect and trust among the team mem- bers. T eam psychology safety is significantly different from the concept of cohesiveness, which can result in a “groupthink” culture that can reduce the confidence and willingness to speak up and disagree. The concept of team psychology safety is closely related to the concept of trust, defined as the expecta- tion that others’ future actions will be favorable to one’s inter- ests, whereby one is willing to be vulnerable to those actions (Meyer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995; Robinson, 1996). Howev- er, team psychology safety goes beyond interpersonal trust and 1Also John Dewey (1922) viewed learning as a continuous process of de- signing, carrying out, reflecting, and modifying actions.  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 92 describes a team culture and climate characterized by interper- sonal trust and mutual respect in which the team members feel confident and comfortable being themselves (Edmondson, 1999). To become a real group phenomenon, not just on the individual team member level, team psychology safety must be a belief shared by the team members. Previous work on learn- ing has found that it is difficult to try new ideas in organiza- tions without psychology safety (Schein, 1993; Edmondson, 1999). Poor psychology safety will doubtless result in what Argyris (1982) calls defensive routines, mentioned earlier in this article. Team Learning Behavior Amy Edmondson’s (1999) concept of team learning behavior as a process, rather than an outcome, focuses on behavior and activities that encourage and promote learning behavior, rather than outputs in terms of cognition and behavior, such as KSA. These team learning activities and behavior “conceptualize learning at the group level of analysis as an ongoing process of discussion, reflection and action, characterized by asking ques- tions, seeking feedback, experimenting, reflecting on results, and discussion of errors or unexpected outcomes of actions” (p. 353). There is interplay between team learning behavior in the form of reflection and team learning involving action. Learning behaviors such as discussion and reflection are team behaviors that include sharing information, seeking feedback and discus- sion of errors; these all promote reflection and new insights, but not necessarily actions and new theory-in-use. Learning beha- vior occurs as action when decisions are actually made as a result of these new insights; these decisions then change and improve the team’s performance (Edmondson, 2002). Team learn- ing behavior is closely related to Senge’s (2006) concept of dia- log as the fundamental means for team learning. To summarize (Figure 1) context support and team leader coaching are essential for creating and maintaining team psy- chology safety which is vital for creating team learning beha- vior. Psychology Safe ty as the Centre of Gravity for Team Learning The most striking result in Edmondson’s (1999) study shows that the “centre of gravity” for team learning is psychology safety, i.e. the most important variable, among all those con- nected with the encouragement and achievement of learning behavior, is team psychology safety. There are substantial and highly empirical relationships between team psychology safety and learning behavior in Edmondson’s data, which displayed strong evidence of links between a coherent interpersonal cli- mate (characterized by the presence of a blend of trust, respect for each other’s competence, and caring about each other as people) and team psychology safety. The implication of this result is that people’s beliefs about how others will respond— if they engage in behavior for which the outcome is uncer- tain—affects their willingness to take interpersonal risks (Ed- mondson, 1999). Edmonson also found evidence that a lack of team psychology safety contributed to a reluctance to ask for help and an unwillingness to question the team goal for fear of sanction by management. Learning behavior in social settings can be risky, but can be mitigated by a tolerance of imperfec- tion and error. Context Support Team leader coaching Team psychology safety Team learning behavior Figure 1. A model of team learning2. Edmondson also showed the importance of a leadership style that supports learning behavior by creating psychology safety among the team members. Team leaders whose behavior en- courages input and discussions can create a perception of psy- chology safety that results in a positive cycle of discussion, reflection and action that enables progress in team learning and team learning behavior. Edmondson’s study shows that psychology safety is the cen- tre of gravity for team learning. This is a very important point because it highlights the enormous potential to create and in- crease team psychology safety by developing appropriate lea- dership coaching styles and providing relevant, high quality con- text support, both of which can be define d and enhanced in team training exercises and in real military operations. Methods With the aim of studying team learning in a military staff ex- ercise and testing Edmondson’s team learning model we de- cided to study a military staff exercise that takes place in late spring every year3. The Research Site4 The research site was the Combined Joint Staff Exercise (CJSE) which is a multinational exercise run by the Swedish Armed Forces (450 officers) in co-operation with the Swedish National Defence College (65 teachers and 143 students) with participants from the Baltic Defence College (15 teachers and 70 students), the Finnish National Defence University (15 tea- chers and 90 students), the Norwegian Defence Command and Staff College (5 officers), Norwegian Operational Headquarters (5 - 10 officers) and the Swiss Armed Forces Headquarters (20 officers). 60 civilians from the Swedish Women’s Voluntary Defence Service and other voluntary organizations also took part and about 10 civilians from the Folke Bernadotte Acade- my5. Altogether there were about 1000 people involved in the exercise. The training audience (TA) that took part in this study consisted of about 300 hundred officers from the participating Defense Colleges/Universities (captains and majors). The aim of the exercise is to prepare the participants for 2This is a slightly revised model of Edmondson’s model of work-team learn- ing adjusted to suit this specific study where we don’t study the team per- formance, for the ori ginal model see, Edmondson (1999: p. 357) . 3Every year the SAF runs a large military staff exercise—either the Com- bined Joint Staff Exercise (CJSE) or Exercise VI KING, which is a similar, but larger exercise. This study was conducted at CJSE 2012. 4This information is from is taken from the Swedish Armed Forces Headq u- aters compen dium EXSPEC, Exer cise Specificat ion for the Combi ned Joint Staff Exercise 2012 (CJSE 12) (2011-06-17) . 5The Folke Bernadotte Academy (FBA) is a Swedish govern ment agency dedicated to improving the quality and effective ness of international peace interv entio n .  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 93 work in a multifunctional and multinational staff with a focus on training in staff methods and procedures. The exercise is part of the Swedish Partnership for Peace Goals 2202 and Eng- lish is the official exercise language. The exercise scenario is based on a UN Chapter VII6 mandated NATO led Crisis Re- sponse Operation. Team Learning in CJSE CJSE is created for individual learning, team training and team learning for military staffs. The staffs consist of a number of headquarters: BOGALAND Forces (BFOR HQ), Land Com- ponent Command (LCC), Maritime Component Command (MCC), an Air Component Command (ACC), 19 Mechanized Brigade (MECH BDE) and a Special Operations Component Command (SOC). The staffs are based at three different loca- tions in Sweden, but in this study four staffs took part—BFOR, LCC, MECH BDE and SOCC. These staffs were based in Enköping some 70 kilometers north west of Stockholm; the Maritime Component Command and Air Component Command were not included in this study. Besides the different staffs there are three teams in the exer- cise organization that have an indirect or direct pedagogic in- fluence on the TA and which can be seen as important context support for the TA. Firstly, there is the Observer and Training Team (OTT), which works in direct contact with the TA and is involved in direct pe dagogic act ivities with the m. The role of the OTT is t o sit with the sections and observe their work, giving advice and if necessary train individuals, groups, sections or the whole staff. The OTT is the main pedagogic instrument for helping the TA during the exercise. They are experts on all elements of staff work and most of them are experienced officer teachers from the participating nations Defense Academies or Universi- ties. The OTT also includes a group of English language teach- ers who provide language support and feedback, primarily to the TA, but also to others involved in the exercise, if required. Secondly, there is Game Control (GC) whose function, based on the exercise training objectives, is to implement “injects” into the scenario that will “force” the staff and sections to act in such a way that they are training and achieving the training objectives. GC also has response cells that are in direct contact with the TA and respond to TA actions or act as the enemy. Therefore, GC plays both an indirect and direct pedagogic role for the training audience. Thirdly, there is the Exercise Evaluation Team (EXEVAL), which is responsible for evaluating the entire exercise by ques- tionnaire, interviews and collecting written reports from the dif- ferent staffs, sections and teams involved in CJSE. EXEVAL plays no direct and active pedagogic function for the training audience during the exercise, but is probably the most impor- tant part in improving and developing CJSE over the longer term. Some weeks after the completion of CJSE EXEVAL ar- range a Post Exercise Discussion with all teams involved in organizing and running the exercise. The conclusions from this meeting and the evaluation completed by EXEVAL are docu- mented in a Final Exercise Report, which is one of the most important inputs into the planning of the next CJSE. Sample The study involved both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods with the aim of gaining a comprehensive understanding of team learning. Table 1 shows the sample in this study. Data Collection The quantitative part of the study was conducted as a survey using Edmondson’s (1999) original questionnaire. Because we wanted to differentiate between learning behavior as reflection and learning behavior as action, we tried to develop an addi- tional scale with questions on the subject of learning behavior as action. However, this showed insufficient internal consis- tency so it was deleted from the study. The questionnaires were distributed electronically to all staff members in the TA. Be- cause the official language of the exercise is English, we made the reasonable assumption that the participants from various countries would have sufficient proficiency in the English lan- guage to understand the questions in the questionnaire, which are not overly complex. Table 2 shows demographics. Interviews The qualitative part of the study involved l ength y, se mi-structured, Table 1. The sample. Interviews Exercise management Observer and training team (OTT) 3 Game control team 1 EXEVAL team 1 Training audience staffs BFOR 4 LCC 2 MECH BDE 4 SOCC 4 N 19 Question na ire Respondent s from training audience staffs N 58 Table 2. Demographic. n % Gender Mal e 52 93 Female 4 7 Nationality Swedish 41 Other 14 Age 30 - 39 31 ≥40 25 Position Section member 35 Section or subsection command er 20 Service Army 32 Other 24 6Chapter VII: Action with respect to threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression. (http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter/ chapter7.shtml) (2012-05-11).  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 94 individual interviews with officers in the TA such as section leaders, sub-section leaders, staff members and officers in- volved in running and evaluating the exercise. The interviews were strongly focused on the learning themes in Edmondson’s team learning model. Each interview lasted 11 - 25 minutes and was recorded and transcribed by one of the authors. Several informal and spontaneous conversations were conducted on a daily basis with officers in different sections and the impression gathered from all these conversations were similar to the opin- ions put forward by the informants. The interview material was analyzed and structured in line with the themes and issues that were the focus in the team learning model used in this study. Results The results are organized around themes in the team learning model described above. The results focus on team learning in the TA, but also reflect team learning in those teams running the exercise such as OTT, GC and EXEVAL. Before presenting the results, we will give a brief description of the pedagogical settings and basic pedagogical method used during CJSE. Pedagogical Setting and Basic Pedagogical Method All learning activities in the sections and teams focused on tasks and the completion of tasks. The teams are given certain tasks, which have to be completed within a specific timeframe and to a sufficient standard of quality. The central pedagogical method used in CJSE is “on the job training” or as some said “Being thrown in at the pedagogic deep end”, meaning that they got a task to work out within a certain timeframe, which they generally have no prior experience of, as well as possible with the help of the members of their team. The TA arrive on Monday of the first week when then they have to prepare themselves, getting to know each other and starting to build routines for the staff work until Thursday the same week when they conducted a “rock drill” which is a kind of dress rehearsal before the exercise start on Friday. The exercise lasts for five days, from Friday of the first week to Wednesday of the second week. The TA consists of temporarily assembled staffs from different nations, many of whom have never met before, while others are student officers from the different national defense academies and universities. The commanders of the sections are officers from the Swedish Armed Forces HQ who fill the same real positions in the HQ. The deputy commanders of sections are student officers from the defense academies and universities. The official exercise language is English and everything has to be done in English. The analytical variables in this study consisted of four indic- es which will be presented below. The indices demonstrated adequate internal consistency. The Cronbach alphas for the in- dices ranged from .70 (Context support) to .89 (Team leader coaching). The variables were: Context support (α = .70, five items: “”). Team psychology safety (α = .74, seven items: “”). Team leader coaching (α = .89, three items: “”) . Team learning behavior as reflection (α = .75, seven items: “”). Results from the Survey In Table 3 we can see that all mean values are positive and Table 3. Mean. N M SD Context support 55 4.8 .65 Team psychology safety 55 5.8 .87 Team leader coaching* 54 4.1 .85 Team learning behavior as reflection 54 5.2 .83 Note: *The scale for team leader coaching is 1 - 5 and for all others 1 - 7. clearly above the middle of the scale, which should be an indi- cation that the TA is quite satisfied with the exercise. Team leader coaching and team psychology safety have the highest score, which indicates that the TA feel safe within their team and with their team leaders and their coaching style. A Pearson correlation test shows that there is no correlation between psychology safety and context support but strong cor- relation between psychology safety and team leader coaching (.001) and between psychology safety and learning behavior (.000). Context support and team learning behavior has strong correlation (.001). Team leader coaching and learning behavior as reflection has strong correlation (.000). Results from the Interviews Context Support The main context support in CJSE consists of 1) the Bo- galand scenario, which gives the basic framework of the opera- tion and the geographic conditions; 2) the Operational Plan (OPLAN), which describes how to run the entire operation giving End State, Objectives and so on; and finally 3) the Stan- dard Operating Procedures (SOP), which describe working pro- cesses and methods within the staff. Beside this background context support, the teams have continuous access to expert as- sistance and guidance from the OTT on a daily basis and ap- propriate technology such as computers and telephones. Positive Context Support The most obvious positive context support mentioned by the informants is the OTT, which has a concrete pedagogic func- tion involving a mix of teaching, mentoring and team coaching. Members of the OTT see themselves as helpers rather than judges. OTT: The main aim of the OTT is not to evaluate, but ra ther to observe and train—this isn’t about evaluating performance; on the contrary, it’s about helping the exercised staffs achieve the goal of improving and achieving the exercise objectives. The OTT’s task is to observe the TA and if needed mentor and train them. Since the OTT mostly consists of teachers from the various defense academies and universities, they are well known to many in the TA. Many of them have been OTT in previous CJSEs and are definitely a key element when it comes to creating a feeling of team psychology safety. They also have an electronic reporting system where all in- formation goes to a central server. They use notepads to record their observations of staff work in the sections, which are then used for pedagogical discussion with the TA. The OTT has two meetings per day when they inform each other about events in the different sections and discuss what they have to improve the following day.  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 95 OTT: We have a few meetings during the day where we re- port back. It’s not a standalone process—we need to have a dis- cussion with others in the OTT. You can’t do your own thing— you have to listen to others, which helps increase your own un- derstanding. The OTT not only has a daily loop of learning behavior in the form of discussion, reflection and incremental actions on a daily basis, but also year on year. Another important form of context support is GC, whose task is to play injects into the scenario with the aim of guiding the TA to practice the training objectives. GC has frequent contact with OTT where they carry out short evaluations of the TA’s response to injects and decide if they can proceed as planned or if something needs to be changed. GC also has response cells, whose task is to respond to the TA’s responses to injects. Like OTT GC has their own daily meetings where they inform each other about the day’s events and what has to be improved the following day. GC also has a learning loop of learning behavior in the form of discussion, reflection and incremental action on a daily basis, but also changes and improvements to injects from exercise to exer cise. The third and final form of context support, which has con- siderable pedagogic influence on the whole exercise and the training audience, is EXEVAL, whose evaluations are the fun- damental input in the effort to improve and develop all ele- ments of future CJSEs. EXEVAL: Our role is to evaluate the entire exercise. This is done through a Final Exercise Report (FER). This contains a number of conclusions about what worked during the exercise and what did not work and is directed at the exercise “owners”. They then write a directive saying how the next exercise should be conducted. We then follow the entire planning process for the next exercise. EXEVAL has daily learning behavior meetings to discuss, reflect and improve via incremental actions. EXEVAL has no direct pedagogic influence on the TA. Negative Context Support There were three negative aspects regarding context support mentioned by the informants. Firstly, some thought the information about the scenario, the OPLAN and SOPs that they received before the exercise was not of an appropriate standard. The opinion was that this part of the context support required significant improvement. OTT: Preparation needs to be improved—it’s OK now, but can be better. It should be possible to produce better documents, plans and a better situational scenario. TA: What surprised me most was the amount of friction and lack of clarity about the start situation. How things should be when we started—all the confusion. For example—it was D + 10. What did this mean to us and what should happen? Secondly, the TA has insufficient time or opportunity to prepare properly before the exercise. EXEVAL: It’s on the wish list that pre-training should be better. We’ve said that it would be desirable if participants did some sort of certification before the exercise—some easy training packa ge so t hey can a t least get into the exercise before they arrive. OTT: It might be possible to link some sort of ADL (Ad- vanced Distance Learning) course—so that you c an go into some web site in advance. The third and final problem mentioned concerned the scena- rio. The scenario is not a problem in itself, but this scenario has been used so many times in CJSE and in another regular staff exercise named Viking, that many in the TA have strong pre- conceptions about the scenario and injects, which had a nega- tive impact on their staff work. During this CJSE the GC tried to introduce new injects with the aim of making the TA identify a threat in another geographic area than the usual one, but the TA did not trust that information and stayed in the wrong geo- graphic area waiting for the usual scenario and injects to hap- pen. GC: Preconceptions about the old exercise play are so strong that it’s difficult to get them to change course and take other decisions. They think we’re trying to fool them. These three context support weaknesses pose some pedago- gic challenges and probably have some negative influence on the psychology safety feeling among the TA but not too much; it seemed rather to produce some frustration. Team Leader Coaching The team leader function in the sections is shared between the section commander and the deputy section commander. The section commander’s main responsibility is to interact with the world outside the section and with other section commanders, while the deputy section commander’s main responsibility is to organize and direct the work within the section, i.e. responsibil- ity for the team leader coaching function focused on in this study. Positive Team Leader Coaching The general opinion seems to be that the leadership and team leader coaching in this exercise is excellent. The mean score in the survey is 4.1 of 5 and all the informants interviewed are evi- dently positive about the leadership style and leadership coach- ing. TA: He is the boss, but there’s no prestige involved and he always listens when I have something to say. When interviewing team leaders it seems obvious that they have a clear pedagogic idea behind their coaching approach where they try to maximize learning for as many as possible. TA: I think individual learning is also important. You could always give the task to someone who has the necessary know- ledge, but that’s not the point of this exercise—we should be able to play the role we are given, be that boss or analyst. Eve- ryone should learn something during the exercise. For example, we’ve just given a task to the assessment team, which could be completed by one person, but we’ve split it between three people so that they all feel responsible for a task. I know that others do likewise because everyone has to be involved and feel part of the team—otherwise, it would not be an exercise for everyone. This way everyone goes home saying they learnt something, rather that some people doing lots of work and oth- ers nothing at all. That could easily happen if you only focus on the outcome. There seems to be a general opinion among the informants that there is a kind of typical and significant democratic Swe- dish leadership style that coincides well with what is described as a positive leadership coaching style in Edmondson’s team learning model with features like team leaders encouraging team members to ask for help, to reveal and discuss errors, and have an open minded approach to discussing and solving problems.  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 96 TA: And the strength of the learning is the group discus- sions—we can think one way, but we can also think another way. Not getting locked into a sort of cultural norm where “this is the way to do things and it’s always right”. Being open- minded, listening and taking things in; saying to yourself—aha, I hadn’t thought about that. Adopting a certain modesty a nd be- ing able to change your ideas, broaden your thinking and think outside the box. It is also very important that you do not be- come locked in your thinking and the only way to achieve that is for everyone to work together with all minds focused on the same thing. The right leadership style is essential in creating a culture of team psychology safety. The informants also mentioned the leadership doctrine Mis- sion Command as typical of the leadership style in the Swedish and other armed forces. Mission Command means that the com- mander gives a broad order and the subordinates are trusted to complete the task without over-supervision by their commander, which is unlike the command and control leadership doctrine in some armed forces. This leadership style is also fruitful when it comes to creating a culture of team psychology safety. TA: There are differences between various cultures. Some are us e d t o thei r commanders working one way—some are used to other ways. Give someone a task and let them take the re- sponsibility for seeing it through. This goes without saying for us. Negative Team Leader Coaching None of the informants made any negative comments about the leadership or leadership coaching. Team Psychology Safety Team psychology safety is essential in a military staff exer- cise like CJSE in order for the exercise to be successful. There are some major challenges to meet when trying to create psy- chology safety during CJSE. Firstly, the staffs and headquarters are temporarily assembled with participants from about twenty nations. Secondly, there are quite big differences in English language skills and professional backgrounds; some officers are students, while others are filling their usual positions as sec- tions leaders in the Swedish Armed Forces HQ. Positive Psychology Safety The informants express a fundamental feeling of team psy- chology safety in the interviews. This is strongly supported by the survey where the score for team psychology safety is 5.8 in a scale to 7. They say that they are not afraid of owning up to errors or admitting that they do not know everything; they can ask team members, deputy section commanders or OTT for help. TA: You feel that there is room for mistakes without a feel- ing that you are under-performing or bad at your job; everyone knows it’s difficult, because we’re all knew to our posts. I was not worried abou t my performance when I got he re because I’ve never worked in a brigade HQ before—and on that basis you can set your own objectives. The section commanders, deputy section commanders and OTT also frequently highlight the need to create a strong feel- ing of psychology safety in the team if you wish to create a successful and effective team. Creating team psychology safety seems to be a hallmark of Swedish leadership style and culture. Negative Psychology Safety The informants made no negative comments about individual or team psychology safety in this exercise. Team Learning Behavior as Discussion and Reflection Team learning behavior in the sections takes the form of daily discussions and reflection on when, how and who is going to deal with a task, or which procedures are adequate or which should be changed. And the team members learn a lot from each other. TA: Those with less experience who do this exercise learn a great deal. What I see as a great benefit of this exercise is that you learn from one another. Most teams in the sections have at least one team meeting every day, and all sections have a daily meeting called a “hot wash up” at the end of the day. The basic idea behind the “hot wash up” is that everyone in the section should feel free and confident to speak up and say what is good and what is bad and what should be changed or adjusted during the next day’s work. TA: We finish the day with “hot wash ups”—everyone’s there and it isn’t only the bosses who speak. Everyone explains what they’ve done today, what they have learnt today and what they’re going to do tomorrow. It’s a good way to get people to think through and reflect on what they’ve done. Nobody’s input is more important than anyone else’s. Everyone can have their say and everyone generally has something to say. Interestingly, some can say “today I attended a lot of meetings and didn’t really understand what I did, but maybe things will be clearer later” and two days later they say that things have become clearer. The “hot wash up” is usually led by the deputy commander, but in many sections the section commander also attends the meeting. Some of the sections decided to document the out- come of “hot wash ups” so they can be useful input to the final exercise evaluation and report. Other sections have the policy of no documentation because it risks undermining team mem- bers’ willingness to speak freely. Positive Learning Behavior as Discussion and Reflection Almost all informants interviewed in this study expressed not only very positive experiences of team learning be havior through discussion and reflection in their own specific teams and sec- tions, but also on the entire exercise. They say that they never hesitated in speaking freely at the “hot wash ups” and they had all a strong conviction that the main purpose of the exercise is learning and learning behavior and not to produce outstanding performances and perfect outcomes. TA: I think the climate is good with lots of room for expres- sion. It’s not a “production” exercise and you’re not criticized if your English wasn’t good enough—the focus was on how to improve things next time. This was also confirmed by the OTT. OTT: CJSE can be seen as an exercise where all participants learn something—i.e. not only those who are there to practice staff work, but also those involved in the planning and running of the exercise; lessons are learnt about how to make the exer- cise better next time. Negative Learning Behavior as Discussion and Reflection One negative statement concerning learning behavior through discussion and reflection was that there was no point in raising problems that were too complex at “hot wash ups” because the  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 97 exercise is too short to solve such problems. On the other hand these problems can be reported in the final evaluation to EX- EVAL and taken into consideration when planning the next exercise. TA: Some changes are too big to implement during this ex- ercise, but we report them in the final evaluation. Team Learning Behavior as Action All learning activities in the exercise are focused on tasks and completing tasks within a certain timeframe to a sufficient- ly high standard; this means that there is no time for endless discussions and reflection. This has significant implications for the relationships between learning behavior in the form of dis- cussion, reflection and action. All discussions and reflection are fundamentally aimed at producing concrete suggestions for action to improve the staffs’ work. The outcome of the daily “hot wash up” meetings is a list of actions to be implemented in the team’s staff work the next day. Positive Team Learning Behavior as Action Many informants expressed the idea that this attitude to the close relation ship between discussion, reflection and actio n should be seen as a significant part of a military cultural habit. TA: We address those issues that we have decided to discuss. We deal with those tasks. In an exercise like this there is no time to stand around and chat. We can’t simply have a talking shop—we have to produce results as well. Negative Team Learning Behavior as Action No informants expressed any doubt about the ability of of- ficers to convert new insights from discussion and reflection into actions. In summary, the heart of the pedagogic idea behind CJSE is to practice staff work in action, discuss and reflect on the staff work completed, and turn these new insights into real actions and new theory-in-use. These new actions are then evaluated through discussions, reflections and the implementation of new actions—and so on in a continuous learning behavioral process. The pedagogical situation at CJSE described in Figure 2 shows that team leader coaching is not just a context support resource, it is a continuous pedagogic activity at all stages of the exercise, performed primarily by the section and deputy section leader and also secondary by the OTT. Discussion The aim of this study was to explore and gain more know- ledge and a better understanding of learning in teams during a military staff exercise, by using central elements of Amy Ed- mondson’s theoretical model for analyzing team learning. The study conducted at the annual staff exercise CJSE in Sweden shows that Edmondson’s theoretical model for studying and analyzing team learning behavior works well and is useful in this military context. The results of this study supports Edmon- dson’s model for team learning; i.e. team psychology safety is central for creating team learning behavior. The results from the interviews also confirm a close relationship between learning behavior as discussion and reflection and learning behavior as action, which goes a bit beyond Edmondson’s original model for team learning that does not include learning behavior as ac- tion. This study also shows that team leader coaching is not just Figure 2. The pedagogical cycle in CJSE. a context support resource, it is a continuous pedagogic activity at all stages of the exercise. This should be seen as a potentially valuable theoretical contribution to Edmondson’s team learning model well worth further development in future studies. Unfor- tunately the scale for learning behavior as action did not work in this study and a new validated scale will be developed and included in next year’s CJSE questionnaire. The results confirms that CJSE seems to offer a highly sup- portive environment for team training and team learning con- sisting of language support and sufficient context support in the form of background information, such as the scenario, OPLAN and SOP, even if there is room for improvement in some areas of context support. The context support from EXEVAL and GC should be regarded as an important but indirect pedagogic tool; whilst the OTT’s direct pedagogic activities are the most im- portant pedagogic context support for the TA. The team leader coaching approach among the OTT and other leaders at CJSE seems to be the most important factor when it comes to en- couraging team psychology safety among the TA. Most learning behavior takes place within the teams of offic- ers in the TA. The teams are given tasks to complete and when doing so they discuss, reflect and help each other. Those with more knowledge help those with less. This is the most powerful pedagogic tool in CJSE, which requires a good portion of psy- chology safety and supportive team leader coaching. The leadership coaching style is extremely important for creating psychology safety and, for that reason, should be in- vestigated in more depth than was possible in this study. Is there a universal leadership coaching style that supports psy- chology safety for participants from all the nations in CJSE? Swedish officers seem to have their own perception of a spe- cific kind of Swedish democratic leadership coaching style that is less hierarchical than they perceive leadership in other na- tions to be. This may be correct, but it is an interesting and important topic for further research to distinguish whether or not there are different leadership coaching styles among the nations participating in CJSE, and if so, what consequences this has for team learning processes. During CJSE the leadership style has obviously encouraged the creation of positive psy- chology safety among the participants in this study. However, this study does not tell us if this so-called Swedish leadership style ha s any less positi ve aspects. There may be a potential for tension between a “friendly” Swedish democratic leadership coaching style and the need to manage complex problems such  E. HEDLUND, J. ÖSTERBERG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 98 as power struggles and conflict within a team or between sec- tions and teams. This issue should be followed up in future studies. In addition, the interactions among individuals within teams, between teams, sections and staffs, and between officers from the different nations should be studied more closely. Finally, there may be considerable risk that teams, to some extent, are using what Argyris (1982, 1990, 1999) calls defen- sive routines to avoid exposing their ideas or lack of compe- tence in front of their team members, or to avoid conflict within or between teams. It would not be too surprising if there were more conflict and tension than discovered in this study in a staff exercise with several hundred participants of over 20 different nationalities7. Limitations This study was exploratory and its findings are limited in several ways. Firstly, the survey sample is too small to give any solid re- sults and cannot be regarded a s solid validation of Edmondson’s team learning model. It can only be seen as giving a prelimi- nary indication of what the results might be. The reason for the small sample is that we were unsure about how to administer the questionnaire during the exercise. It was placed on the ex- ercise network, but few people knew about it before it was tak- en away. We have learnt from this experience and will admi- nister the questionnaire differently next time in order to get a more comprehensive and solid sample. Secondly, we need to complement the interviews with ob- servations from the sections and meetings such as the “hot wash ups” to get a deeper understanding of the leader coaching style and other factors affecting team psychology safety and learning behavior. Thirdly, the relationship between learning behavior in the form of discussion and reflection versus learning behavior in the form of action has to be explored in more depth. Fourthly, we have to develop tools and criteria to evaluate the performance and outcome of the team learning behavior. There is no real point in devoting much effort to team learning behavior, if it does not result in improved performance and out- come. Fifthly, the study gives no specific knowledge about officers from other participating nations in terms of cultural differences and other factors that may influence their perception of context support, team leader coaching styles, psychology safety and team leader behavior such as discussion, reflection and action. Finally, the study gives no knowledge about potential differ- ences between sections in terms of the time perspective in which they work. Some sections work in a current time pers- pective while other sections work in mid to long term perspec- tives, which give different conditions, and probably different needs in terms of context support, leadership coachi ng and learn- ing behavior. Conclusion This study should be regarded as an important first attempt to open a research field of team learning in the Swedish Armed Forces. The study has already given some important insights into the subject, but there is much more to learn. It is clear that Edmondson’s team learning model works well and will be used for future studies. Notably, one unexpected, but most interesting finding was that it is not only the training audience that is involved in team learning during CJSE. It is apparent that all teams involved in the organization and running of CJSE are working very hard on team learning and, like the TA, have a good psychology safety environment for learning behaviors both through discussion and reflection as well as action and performance. REFERENCES Argyris, C. (1990). Overcoming organizational defenses: Facilitating organizational learning. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Agyris, C. (1999). On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Oxford: Black- well Publishing. Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, learning and action: Individual and organizational. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Bresó, I., Gracia, F. J., La torre, F., & Peiró, J . M. (2008). Development and validation of the team learning questionnaire. Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão, 14, 145-160. Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A so- cial-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12, 40-57. Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Tannenbaum, S. I., Salas, E., & Volpe, C. E. (1995). Defining team competencies and establishing team training requirements. In R. Guzzo, E. Salas, & Associates (Eds.), Team ef- fectiveness and decision making in organizations (pp. 333-380). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Dewey, J. (1922). Human nature and conduct. New York: Holt. Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administration Science Quarterly, 4, 350-383. Edmondson, A. C. (2002). The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: A group-level perspective. Organization Science, 13, 128-146. Garavan, T. N., & McCarthy, A. (2008). Collective learning processes and human resource development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10, 451. Goldstein, I. L., & Ford, J. K. (2002). Training in organizations: Needs assessment, development, and evaluation (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations— Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill. Salas, E., Di azGranados, D., Klein , C. C., Burk e, S., Sta gl, K. C., Good- win, G. F., & H alp in , S. M. (2008). Does team training impro ve team performance? A meta-analysis. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 50, 903. Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of learning organizations. New York: Random House. Stagl, K. C., Salas, E., & Fiore, S. M. (2007). Best practices in cross trainin teams. In D. A. Nembhard (Ed.), Workforce cross training handbook (pp. 156-175). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Thomas, J. B., Sussman, S. W., & Henderson , J. C. (20 0 1 ). Understand- ing strategic learning: Linking organizational learning, knowledge manageme nt and sensemaking. Organization Science, 12, 331-345. Tyler, T., & Lind, A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. Advances in Experimental Psychology, 25, 115-191. Vera, D., & Crossan, M. (20 04 ). St ra tegic lead ersh ip and organizational learning. Academy of Management Review, 29, 222-240. Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, CA: Cambridge University Press. 7During the exercise we asked students from the Swedish National Defence College to carry out analyses of their own staff as part of their studies. In these anal yses we fo und that th ere seemed to be some t ensions between di f- ferent sections in the staff because some sections are regarded as more important than others. The exercise play is also more adapted to some sec- tions than others. Some students also said that it was okay to bring up and discuss minor issues, but because of the time limitations of the exercise it was not the right time to bring up and address more challenging issues. These analyses could not be used in this study because of ethical considera- tions and this analysis task was not part of any research. |