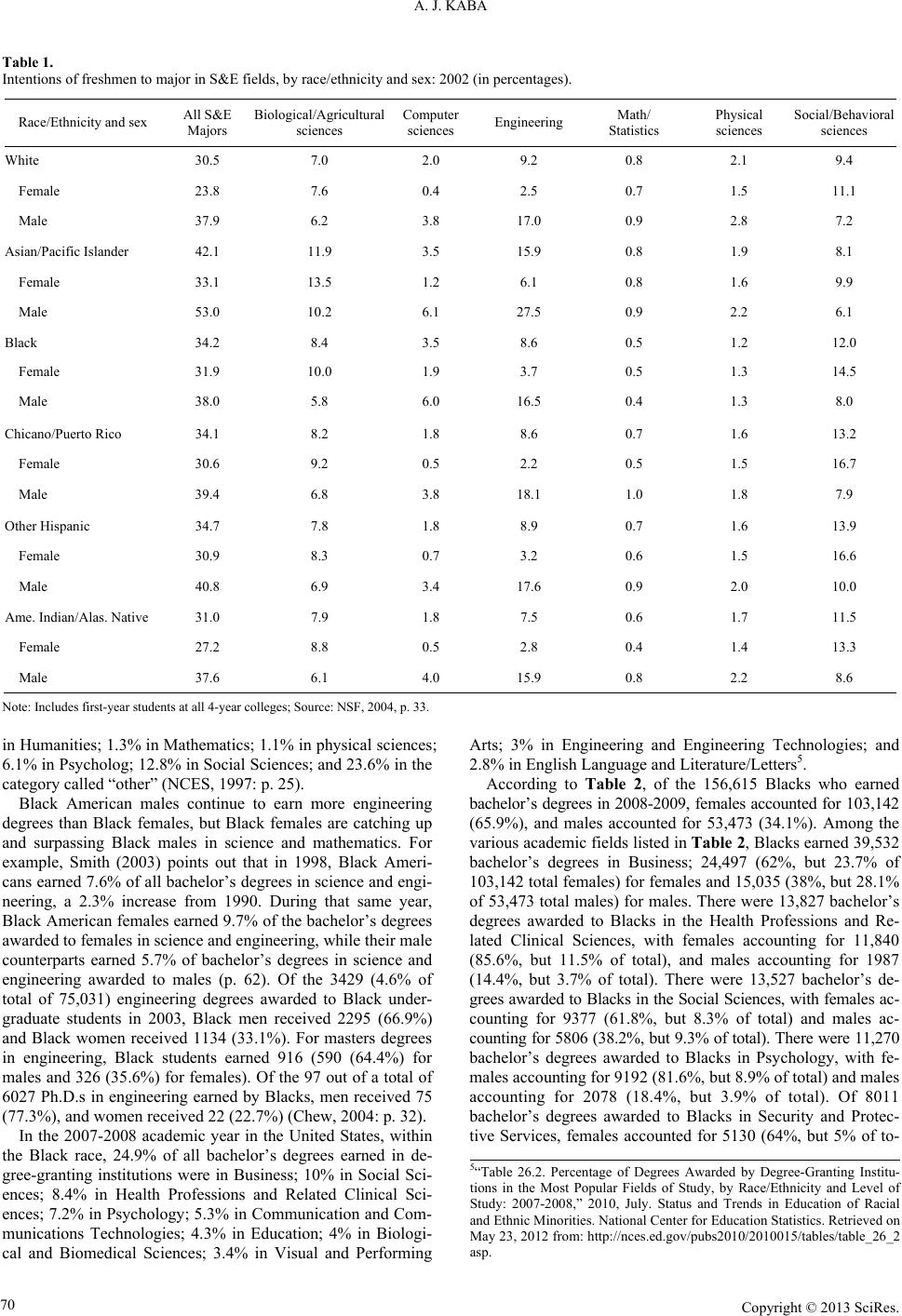

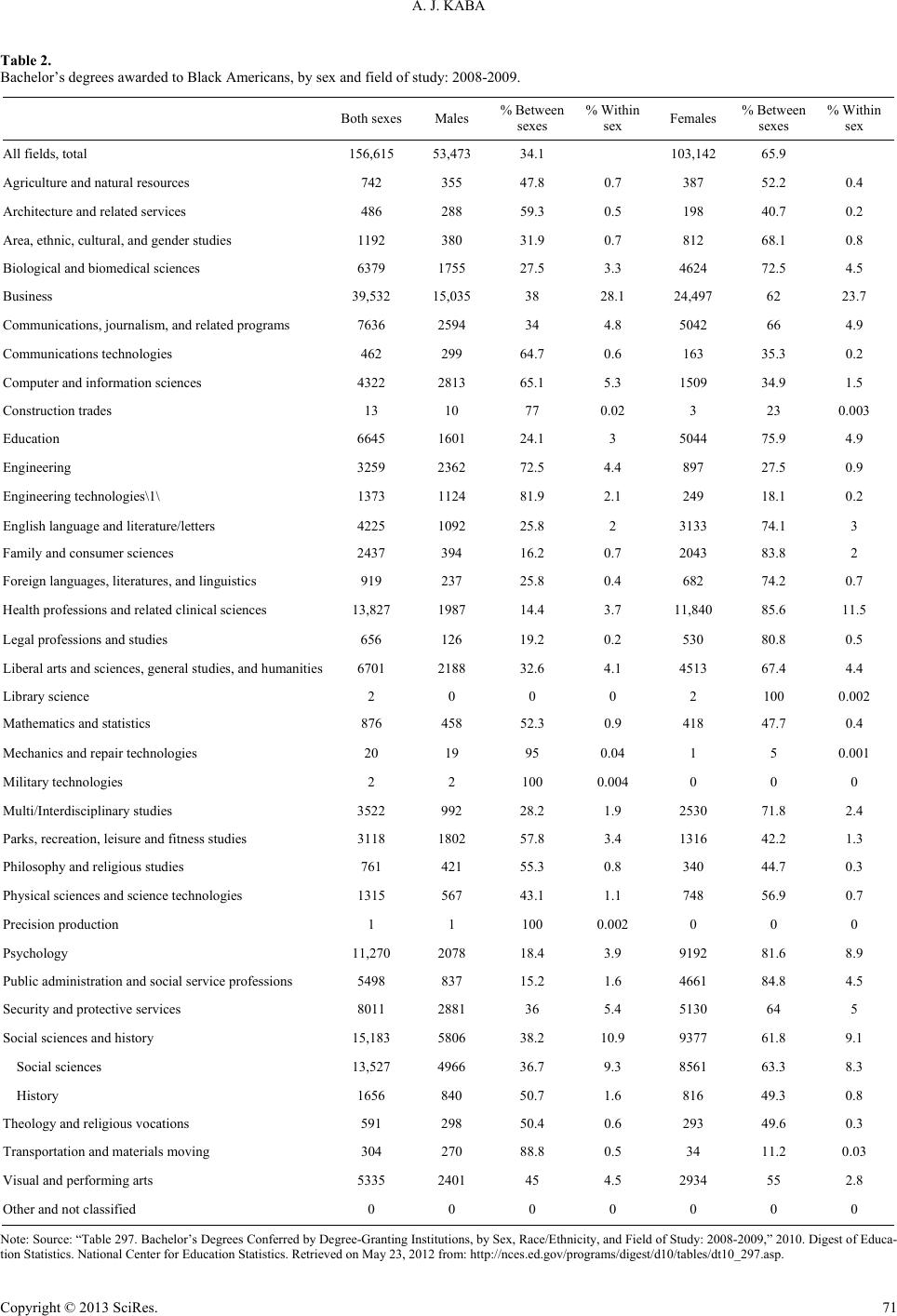

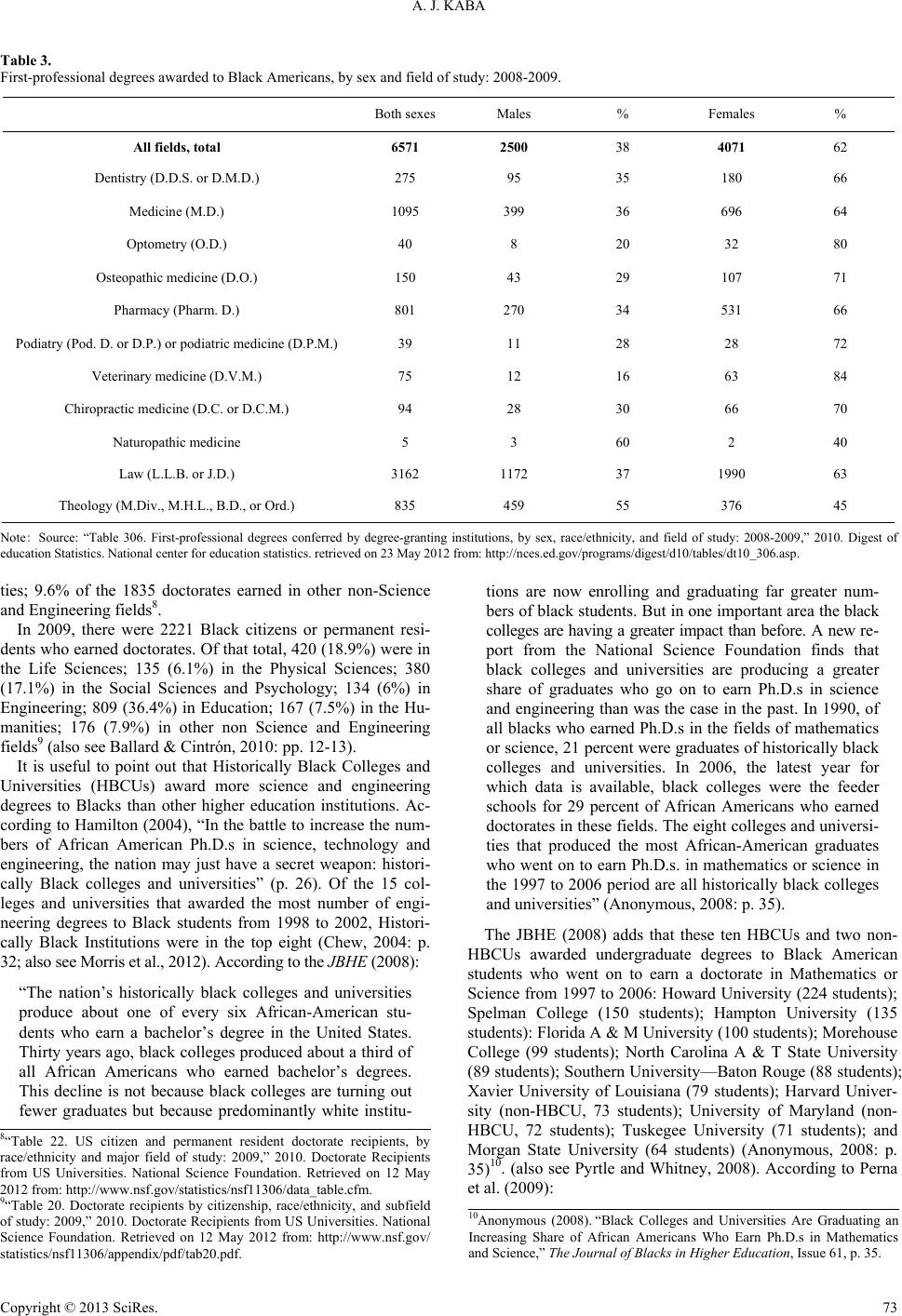

Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 67-82 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2013.31012 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67 Black Americans, Gains in Science and Engineering Degrees, and Gender Amadu Jacky Kaba Department of Sociology, An thropology and Social Work Se t on Hall University, South Orange, USA Email: kabaamad@shu. edu Received November 15th, 2012; r e v ise d De cember 14th, 2012; accepted December 26th, 2012 This article is divided into three parts. First, it presents the most recent data on Black Americans’ higher education enrollment and degree attainment rates, and overall numbers of earned college degrees at all levels. Second, the article presents data on the most recent enrollment rates and total numbers of science and engineering degrees earned by Black Americans. Finally, the article presents a number of factors that have contributed to the gains in earned science and engineering degrees by Black Americans, and also factors that have contributed to their slow rate of progress in these academic fields. Keywords: Black Americans; Science and Engineering; Mathematics; Gender; Progress Introduction In a very short period from the 1970s to present, people of Black African descent in the United States have made substan- tial progress in many important sectors of the society. For ex- ample, by 2001, there were 9101 Black Elected Officials in the United States; 5881 (64.6%) were men and 3220 (35.4%) were women (Kaba, 2012a: p. 8). By 2013, a man of Black African descent, Barack Obama, was in his second four-year term as the President of the United States and he appointed another Black man, Eric Holder as Attorney General, a position one could argue to be second only to the Presidency in terms of power or authority. A Black woman, Oprah Winfrey was listed on For- bes magazine in 2011 as one of the 400 richest billionaires in the world, with an estimated $2.7 billion. During the fall se- mester of 2009, there were 2,782,149 professional staff in de- gree granting institutions in the United States and of that total, Blacks accounted for 207,335 (7.45%). Of the 1,439,144 fac- ulty (instruction/research/public service) in those same institu- tions in the United States during that same year, 95,095 (6.6%) were Black (“Employees in degree-granting institutions, by race/ethnicity and primary occupation: Fall 2009,” 2011). There were 2.29 million employed Blacks with at least a bachelor’s degree in the United States by 2000 (Kaba, 2012a: p. 8). In addition, there are substantial numbers of Blacks in the enter- tainment industry, business, law, sports, etc. The primary reason or the engine behind this extraordinary success of Black Americans is their participation in the higher education institutions of the United States and elsewhere— college enrollments and degree attainment. Masse y (2003) points out that: “… African-Americans of both genders have benefited from increased opportunities in higher education” (p. 38). For example, in an article that examines the backgrounds of the 2011 Root magazine’s 100 most influential young Black Ame- ricans aged 25 to 45, Kaba (2012a) finds that 70% of the 100 had already earned at least a bachelor’s degree (p. 16), com- pared with 19.8% of Black Americans aged 25 and over, and 30.3% of White Americans in 2010. President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama, Attorney General Eric Holder, Oprah Winfrey, the great Hollywood actor Denzel Washington and the great actress Angela Basset, are all highly educated with at least a bachelor’s degree earned from some of the most highly ranked colleges and universities in the United States. Most importantly, the biggest gain that Black Americans have made as a result of their gains in higher education is their sub- stantial increase in life expectancy at birth. For example, in 2003, the life expectancy at birth of non-Hispanic Black fe- males was 75.7 years (80.3 years for non-Hispanic White Fe- males) and 68.8 years for non-Hispanic Black males (75.6 years for non-Hispanic White males). By 2008, it was 77.5 years for non-Hispanic Black females (81.2 years for non-Hispanic White females) and 70.8 years for non-Hispanic Black males (76.2 years for non-Hispanic White males) (Harper et al., 2012: p. 2258). This article presents the current status of higher education attainment of Black females and Black males in the United States. The article begins by presenting the most recent data on Black Americans’ higher education enrollment and degree at- tainment rates, and overall numbers of earned college and uni- versity degrees at all levels, starting with bachelor’s degrees. Next, the article presents data on the most recent enrollment rates and total numbers of science and engineering degrees earn - ed by Black Americans. Finally, the article presents some fac- tors that have contributed to the gains in earned science and engineering degrees by Black Americans and also some factors cited for the slow growth in these academic fields. Let us now begin by examining higher education enrollment and degree attainme nt rates of Black Amer i can females a n d mal es. Black Americans and College Enrollment Rates In 1970, there were 378,000 Black Americans enrolled in higher education institutions (Franklin and Moss, 1994: p. 9). In 2000, there were 1,505,216 Black citizens enrolled in under- graduate programs in US colleges and universities (National Science Foundation (NSF), 2004: p. 26). In 2010, there were  A. J. KABA 3.25 million Blacks mixed with another race enrolled in col- leges and universities in the United States (“School Enrollment in the United States: 2010,” 2012). Within the Black population in the United States, however, there now exists a major gender gap in educational attainment between Black females and their male counterparts. As Massey (2003) notes: “… over the past several years, it has become clear that despite these opportunities, the educational achieve- ment of African-American men lags severely behind every other group in America” (p. 38). Moreover, the college enroll- ment rates of Black females are not only higher than those of their male counterparts, but also higher than those of other ra- cial/cultural groups and sub-groups. Of the 1,505,216 Black citizens enrolled in undergraduate programs in US colleges and universities in 2000, females comprised 928,866 (62%), and males comprised 576,350 (38%) (NSF, 2004: p. 26). According to the United States Census Bu- reau, in October 2010, there were 292,233,000 people in the United States aged 3 and over. Of that total, 20,275,000 (6.9%) were enrolled in college (undergraduate or graduate); 9,007,000 (6.3%) out of 42,999,000 for males and 11,268,000 (7.6%) out of 149,234,000 for females. For Blacks mixed with another race, it was 1,241,000 (6.9%) out of 18,012,000 for males; 2,009,000 (9.6%) out of 20,939,000 for females; and 3,250,000 (8.3%) out of 38,951,000 for both sexes. For Blacks alone as a single race, it was 1,058,000 (6.3%) out of 16,759,000 for males; 1,831,000 (9.4%) out of 19,548,000 for females; and 2,889,000 (8%) out of 36,303,000 for both sexes. For non-Hispanic Whites, it was 5,673,000 (6.1%) out of 93,085,000 for males; 6,940,000 (7.1%) out of 97,268,000 for females; and 12,613,000 (6.6%) out of 190,353,000 for both sexes. For Asians alone as a single race, it was 647,000 (9.8%) out of 6,587,000 for males; 676,000 (9.5%) out of 7,097,000 for females; and 1,322,000 (9.7%) out of 13,685,000 for both sexes. For Asians mixed with another race, it was 740,000 (10.2%) out of 7,278,000 for males; 727,000 (9.4%) out of 7,732,000 for females; and 1,467,000 (9.8%) out of 15,010,000 for both sexes. For Hispanics of any race, it was 1,302,000 (5.5%) out of 23,864,000 for males; 1,576,000 (7%) out of 22,538,000 for females; and 2,879,000 (6.2%) out of 46,402,000 for both sexes (“School Enrollment in the United States: 2010,” 2012). Black Americans and Degree Attainment Rates The Black population in the United States has also made substantial progress in college or university degree attainment. By 2011, there were 3.437 million Blacks (or mixed with an- other race) aged 18 and over with at least a bachelor’s degree. Of that total, 2.028 million (59%) were women and 1.409 mil- lion (41%) were men. Of the 1.275 million with master’s de- grees, 808,000 (63.4%) were women and 467,000 (36.6%) were men. Of the 189,000 with professional degrees (such as Juris Doctorates and Medical Doctorates), 119,000 (63%) were wo- men and 70,000 (37%) were men. Finally, of the 181,000 with doctorate degrees, 79,000 (43.6%) were women and 102,000 (56.4%) were men1. This means that in 2011, there were 3.437 million Blacks (or mixed with another race) aged 18 and over who held 5.082 million bachelor’s, master’s, professional and doctorate degrees combined, with 3.034 million (59.7%) com- bined degrees for Black women, and 2.048 million (40.3%) combined degrees for Black men. Glazer (2003) points to a study that showed that “… more blacks than whites get law degrees… and more whites than blacks get doctoral degrees (7 percent to 4 percent)” (p. 80). In 1999, 1145 Black females earned doctorates in the United States. In 2009, that figure increased to 16052. In 1999, 908 Black males earned doctorates in the United States. In 2009, that figure increased to 10943. It is important to note that Black Americans, especially Black females, go deep into debt to pay for their higher education. For example, “The average cumulative debt (undergraduate and graduate) of those who earned doctorates in 2009 was $41,018 for Blacks… and $22,518 for Whites. In addition, 27.1% of the Black graduates had debt of $70,001 or more; [but] 10.5% of Whites…” (Kaba, 2012b: p. 138). It is also useful to point out that young Black Americans are doing a very good job of attaining doctorates in their twenties or younger, while older Black Americans in their fifties or older are also going to college to earn their bachelor’s degrees, which were once denied to them. For example, in 2009, there were 17,000 (14.5% of 117,000 total in the United States) Blacks alone or in combination with another race aged 25 - 29 with earned doctorates, with Black females accounting for 13,000 (76.5%, but 11.1% of all 117,000 total), and Black males ac- counting for 4000 (23.5%, but 3.4% of all 117,000 total). The 17,000 Blacks alone or in combination with another race with doctorates in 2009 constituted 0.56% of the 3,012,000 aged 25 - 29. The 13,000 Black females alone or in combination with another race with doctorates in 2009 constituted 0.82% of the 1,592,000 Black females in that age group, and the 4000 Black mal es a lone in that age group with doctorates is 0.28% of Black males aged 25 - 29 (“Census Bureau Reports Nearly 6 in 10 Advanced Degree Holders,” 2011). Finally, in 2008, there were 14,000 individuals in the United States aged 18 - 24 with earned doctorates. In 2008, there were 4,112,000 Blacks alone aged 18 - 24, with males accounting for 1,973,000 (48%) and females accounting for 2,138,000 (52%). Of the 4000 doctor- ates (28.6% of the 14,000 doctorates) earned by Blacks alone in 2008, Black females accounted for all of them (Kaba, 2012a: pp. 14-16). In October 2010, of the 58.1 million non-Hispanic Whites aged 55 and over, 259,000 (0.4%) were enrolled in college (undergraduate or graduate). For 6,915,000 Blacks alone aged 55 and over, 59,000 (0.9%) were enrolled in college (“Table 1. Enrollment Status of the Population 3 Years Old and Over, by Sex, Age, Race,” 2012). The median age when doc- torates were earned in 2009 for all graduates was 32.2 years; 36.5 years for Blacks; 32.2 years for Whites; and 32 years for those who are two or more races (“Table 66. Statistical profile of doctorate recipients, by race/ethnicity and citizenship: 2009,” 2011). Many factors have been cited for the widening gap in educa- tional attainment between Black females and Black males. Kaba (2005) presents six factors that have contributed to the 2“Table 19. Female doctorate recipients, by race/ethnicity and citizenship: 1999-2009,” National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 17 May2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/data_table.cfm. 3“Table 18. Male doctorate recipients, by race/ethnicity and citizenship: 1999-2009,” National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 17 May 2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/data_table.cfm. 1“Table 1. Educational Attainment of the Population 18 Years and Over, by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2011,” 2012. Educational Attainment in the United States: 2011—Detailed Tables. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on February 25, 2012 f r om: http://www.census. gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/2011/tables.html. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68  A. J. KABA gap in higher educational attainment between Black females and Black males. They are: 1) significant high school dropout and low college graduation rates for Black males; 2) high pro- portion of Black males in the United States military; 3) more Black females within the total Black population than Black males; 4) Black males entering the workforce at an early age instead of college; 5) the high death rate of college aged Black males; and 6) the disproportionately high number of Black males in local jails and federal and state prisons (also see Franklin & Mizell, 1995: pp. 5-18). Let us now turn to Black Americans and their gains in science and engineering education. Enrollment and Degree Attainment Rates of Black American Females and Males in Science and Engineering Enrollment in Science and Engineering Black Americans are among those minorities who have made substantial progress in science and engineering since the 1970s. The evidence shows that Black American students are showing interest in science and engineering beginning in K-12 education. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (JBHE) (1996) notes that in science and mathematics, young Black students are improving their standardized tests scores at twice the rate of their White counterparts. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (1997), the proportion of Black high school graduates taking the “New Basics” curriculum (“a core curriculum comprising 4 units of English and 3 units each of science, social studies, and mathematics recommended by the National Commission on Excellence in Education in A Nation at Risk.”) in 1982, 1987, 1990, and 1994, was 11.5%, 24.1%, 41.5%, and 44.7% respectively. For Whites, it was 15.5%, 29.3%, 40.6%, and 53.6% respectively. For Hispanics, it was 6.7%, 16.8%, 30.4%, and 43.8% respectively (p. 5). In 1982, the percentage of Black high school graduates taking selected mathematics and science courses in high school was 22% for Algebra II, 6% for Trigonometry, 2.2% for Analysis/ pre-calculus, 1.3% for Calculus, 0.3% for AP calculus, 19.7% for biology and chemistry, 4.8% for biology, chemistry, and physics. In 1994, it was 43.7%, 13.6%, 9.8%, 3.8%, 2%, 42%, and 13% respectively (p. 7). The average SAT scores of Black test-takers have increased 24 points on the verbal section and 34 points on the mathematics section (NCES, 1997: p. 11). Ac- cording to the JBHE (1996), in 1992, the proportion of nine- year-old Blacks achieving the level of basic understanding of science on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test improved by 24% since 1997. During that same period, Black students improved their mathematics scores by 18 percent (p. 30). Hanson (2004) points out that in 8th grade, young Black female students are more likely to be in advanced, enriched, or accelerated science courses than their young White female peers (40% vs. 24%) (al so see Sullivan & Haskins, 2001: p. 103; Trusty, 2002). Let us examine the trends in college en- rollment and degree attainment in science and engineering of Black Americans in the post-1960s period. According to Hurtado et al. (2009), “In 2005, the same per- centage of African American and White (44%) college-bound high school students indicated their intent to major in science and engineering fields” (p. 191). Table 1 shows the proportion of college freshmen students (by race/ethnicity and sex) with intentions to major in science and engineering fields in 2002. A careful observation of the table shows that although a higher proportion of males than females in all of the racial and ethnic groups tend to major in science and engineering, the gap (6 percentage points) between Black males and Black females is closest than all the other groups (each with at least 9 percentage points), with double figure gaps for Whites (14 points), Asian/Pacific Islanders (20 points) and American India ns/Alaskan Natives (10 point s). How- ever, for the six fields listed (Biological/agricultural sciences, computer sciences, engineering, math/statistics, physical sci- ences and social and behavioral sciences), Black females lead in three (Biological/agricultural sciences, math/statistics, and social and behavioral sciences) and tie with Black males in one field (physical sciences) (Table 1). In 2006, among Black male college freshmen, 36.3% in- tended to major in Science and Engineering: 1.8% in the Physical Sciences; 6.8% in Biological/Agricultural Sciences; 0.8% in Mathematics/Statistics; 3.8% in Computer Science; 8.7% in Social/Behavioral Sciences; and 14.4% in Engineering. Among Black females, 32.1% intended in majoring in Science and Engineering: 1.6% in the Physical Sciences; 11% in Bio- logical/Agricultural Sciences; 0.4% in Mathematics/Statistics; 1.1% in Computer Science; 15.7% in Social/Behavioral Sci- ences; and 2.3% in Engineering4. The data above show that black females are on pace to either catch up or surpass their males counterparts in almost all of these fields listed under science and engineering. It is noted that: “… less than one percent of all African- American college students major in the physical sciences. Also, less than one percent major in mathematics” (Anonymous, 2009: p. 36; also see Marra et al., 2012). Morris et al. (2012) point out that in 2002, there were 266 Black students enrolled in science and engineering fields in graduate schools; 270 in 2003; 261 in 2004 and 262 in 2005 (p. 46). Degree Attainment in Science and Engineering Due to a relatively large increase in its total population and more economic and other opportunities for Black Americans and people of Black African descent, their proportions and actual numbers with science and engineering degrees have in- creased substantially, although as we shall learn later, these degrees are not as high as other racial groups. “Large numbers of blacks now major in biology and health sciences while in college. The number of blacks earning Ph.D.s in science and engineering appears to be increasing each year. Many young blacks are beginning to make great strides in fields that histori- cally have been nearly totally closed to African Americans” (“Young Blacks are beginning to Break Negative Stereotypes,” 2009: p. 36). Slaton (2010) points out “… that the 1930 US census re- ported only 500 black-engineers and architects in the entire country” (p. 17). In 1993, the proportion of bachelor’s degrees conferred to Blacks in Biological/life sciences was 3.6%; 24.6% in Business management; 2.9% in Computer and infor- mation science; 7.2% in education; 3.4% in engineering; 3.9% in English language and literature; 6.1% in health science; 3.5% 4“Appendix Tables 2-15. Freshmen Intending S&E major, by sex, race/eth- nicity, and field; Selected years, 1985-2006,” Chapter 2. “Higher Education in Science and Engineering,” in Science and Engineering Indicators 2008. Retrieved on 23 May 2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind08/c2/ c2h.html. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 69  A. J. KABA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 70 Table 1. Intentions of fres hmen to major in S&E fie lds, by race/ethnicity and sex: 2002 (in percentages). Race/Ethn icity and sex All S&E Majors Biological/Agricultural sciences Computer sciences Engineering Math/ Statistics Physical sciences Social/ B ehavioral sciences White 30.5 7.0 2.0 9.2 0.8 2.1 9.4 Female 23.8 7.6 0.4 2.5 0.7 1.5 11.1 Male 37.9 6.2 3.8 17.0 0.9 2.8 7.2 Asian/Pacific Islander 42.1 11.9 3.5 15.9 0.8 1.9 8.1 Female 33.1 13.5 1.2 6.1 0.8 1.6 9.9 Male 53.0 10.2 6.1 27.5 0.9 2.2 6.1 Black 34.2 8.4 3.5 8.6 0.5 1.2 12.0 Female 31.9 10.0 1.9 3.7 0.5 1.3 14.5 Male 38.0 5.8 6.0 16.5 0.4 1.3 8.0 Chicano/Puerto Rico 34.1 8.2 1.8 8.6 0.7 1.6 13.2 Female 30.6 9.2 0.5 2.2 0.5 1.5 16.7 Male 39.4 6.8 3.8 18.1 1.0 1.8 7.9 Other Hispanic 34.7 7.8 1.8 8.9 0.7 1.6 13.9 Female 30.9 8.3 0.7 3.2 0.6 1.5 16.6 Male 40.8 6.9 3.4 17.6 0.9 2.0 10.0 Ame. Indian/Alas. Native 31.0 7.9 1.8 7.5 0.6 1.7 11.5 Female 27.2 8.8 0.5 2.8 0.4 1.4 13.3 Male 37.6 6.1 4.0 15.9 0.8 2.2 8.6 Note: Includes first-year students at all 4-year colleges; Source: NSF, 2004, p. 33. in Humanities; 1.3% in Mathematics; 1.1% in physical sciences; 6.1% in Psycholog; 12.8% in Social Sciences; and 23.6% in the category called “other” (NCES, 1997: p. 25). Black American males continue to earn more engineering degrees than Black females, but Black females are catching up and surpassing Black males in science and mathematics. For example, Smith (2003) points out that in 1998, Black Ameri- cans earned 7.6% of all bachelor’s degrees in science and engi- neering, a 2.3% increase from 1990. During that same year, Black American females earned 9.7% of the bachelor’s degrees awarded to females in science and engineering, while their male counterparts earned 5.7% of bachelor’s degrees in science and engineering awarded to males (p. 62). Of the 3429 (4.6% of total of 75,031) engineering degrees awarded to Black under- graduate students in 2003, Black men received 2295 (66.9%) and Black women received 1134 (33.1%). For masters degrees in engineering, Black students earned 916 (590 (64.4%) for males and 326 (35.6%) for females). Of the 97 out of a total of 6027 Ph.D.s in engineering earned by Blacks, men received 75 (77.3%), and women received 22 (22.7%) (Chew, 2004: p. 32). In the 2007-2008 academic year in the United States, within the Black race, 24.9% of all bachelor’s degrees earned in de- gree-granting institutions were in Business; 10% in Social Sci- ences; 8.4% in Health Professions and Related Clinical Sci- ences; 7.2% in Psychology; 5.3% in Communication and Com- munications Technologies; 4.3% in Education; 4% in Biologi- cal and Biomedical Sciences; 3.4% in Visual and Performing Arts; 3% in Engineering and Engineering Technologies; and 2.8% in English Language and Literature/Letters5. According to Table 2, of the 156,615 Blacks who earned bachelor’s degrees in 20 08-2009, females accounted for 10 3,142 (65.9%), and males accounted for 53,473 (34.1%). Among the various academic fields listed in Table 2, Blacks earned 39,532 bachelor’s degrees in Business; 24,497 (62%, but 23.7% of 103,142 total females) for females and 15,035 (38%, but 28.1% of 53,473 total males) for males. There were 13,827 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in the Health Professions and Re- lated Clinical Sciences, with females accounting for 11,840 (85.6%, but 11.5% of total), and males accounting for 1987 (14.4%, but 3.7% of total). There were 13,527 bachelor’s de- grees awarded to Blacks in the Social Sciences, with females ac- counting for 9377 (61.8%, but 8.3% of total) and males ac- counting for 5806 (38.2%, but 9.3% of total). The re were 11,270 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Psychology, with fe- males accounting for 9192 (81.6%, but 8.9% of total) and males accounting for 2078 (18.4%, but 3.9% of total). Of 8011 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Security and Protec- tive Services, females accountedfor 5130 (64%, but 5% of to- 5“Table 26.2. Percentage of Degrees Awarded by Degree-Granting Institu- tions in the Most Popular Fields of Study, by Race/Ethnicity and Level o Study: 2007-2008,” 2010, July. Status and Trends in Education of Racial and Ethnic Minorities. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved on May 23, 2012 from: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2010/2010015/tables/table_26_2 asp.  A. J. KABA Table 2. Bachelor’s degrees awarded to Black Am ericans, by sex and field of study: 2008-2009. Both sexesMales % Between sexes % Within sex Females % Between sexes % Within sex All fields, t o tal 156,615 53,473 34.1 103,142 65.9 Agriculture and natural resources 742 355 47.8 0.7 387 52.2 0.4 Architec t ur e and rel ated servic es 486 288 59.3 0.5 198 40.7 0.2 Area, et hnic, cultural, and gender studie s 1192 380 31.9 0.7 812 68.1 0.8 Biological and biomedical sciences 6379 1755 27.5 3.3 4624 72.5 4.5 Business 39,532 15,035 38 28.1 24,497 62 23.7 Communications, journalism, and related pro grams 7636 2594 34 4.8 5042 66 4.9 Communications technologies 462 299 64.7 0.6 163 35.3 0.2 Computer and inform ation scienc es 4322 2813 65.1 5.3 1509 34.9 1.5 Construction trades 13 10 77 0.02 3 23 0.003 Education 6645 1601 24.1 3 5044 75.9 4.9 Engineering 3259 2362 72.5 4.4 897 27.5 0.9 Engineering technologies\1\ 1373 1124 81.9 2.1 249 18.1 0.2 English language and literature/letters 4225 1092 25.8 2 31 33 74.1 3 Family and consumer sciences 2437 394 16.2 0.7 2043 83.8 2 Foreign languages, literatures, and linguistics 919 237 25.8 0.4 682 74.2 0.7 Health profe ssions and related clinical sciences 13,827 1987 14.4 3.7 11,840 85.6 11.5 Legal profes sions and studies 656 126 19.2 0.2 530 80.8 0.5 Liberal arts and sc i ences, general studies, and humanities 6701 2188 32.6 4.1 4513 67.4 4.4 Library science 2 0 0 0 2 100 0.002 Mathematics and statistics 876 458 52.3 0.9 418 47.7 0.4 Mechanics and repair technologies 20 19 95 0.04 1 5 0.001 Military technologies 2 2 100 0.004 0 0 0 Multi/Interdisciplinary studies 3522 992 28.2 1.9 2530 71.8 2.4 Parks, recr eation, leisure and fitne ss studies 3118 1802 57.8 3.4 1316 42.2 1.3 Philosophy and religious studies 761 421 55.3 0.8 340 44.7 0.3 Physical sciences a nd science technologies 1315 567 43.1 1.1 748 56.9 0.7 Precision production 1 1 100 0.002 0 0 0 Psychology 11,270 2078 18.4 3.9 9192 81.6 8.9 Public administration and social service professions 5498 837 15.2 1.6 4661 84.8 4.5 Security a n d p rotective s ervices 801 1 288 1 36 5.4 5130 64 5 Social sciences and history 15,183 5806 38.2 10.9 9377 61.8 9.1 Social sciences 13,527 4966 36.7 9.3 8561 63.3 8.3 History 1656 840 50.7 1.6 816 49.3 0.8 Theology a nd religious vocations 591 298 50.4 0.6 293 49.6 0.3 Transporta tion and materials moving 304 270 88.8 0.5 34 11.2 0.03 Visual and performing arts 5335 2401 45 4.5 2934 55 2.8 Other and not classified 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Note: Source: “Table 297. Bachelor’s Degrees Con ferred by Deg ree-Granting Ins tituti ons , b y Sex, Race/Eth ni cit y, and Fi eld of Study: 2 008-2009,” 2010. Di gest o f Edu c a- tion Statistics. National Center for Education Statistic s. Retrieved on May 23, 20 12 from: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_297.asp. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 71  A. J. KABA tal), and males accounted for 2881 (36%, but 5.4% of total). Of the 7636 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Communica- tions, Journalism, and Related Programs, females accounted for 5042 (66%, but 4.9% of total) and males accounted for 2594 (34%, but 4.8% of total). Of the 6701 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in the Liberal Arts and Sciences, General Studies, and Humanities, females accounted for 4513 (67.4%, but 4.4% of total), and males accounted for 2188 (32.6%, but 4.1% of total). Of the 6645 bachelor’s degrees awarded in Education, females accounted for 5044 (75.9%, but 4.9% of total) and males accounted for 1601 (24.1%, but 3% of total). In science, mathematics and engineering fields males con- tinue to earn more degrees in mathematics and engineering (Freeman et al., 2005; also see Ma, 2009), which is also ob- served in Table 2. Of the 6379 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Bio- logical and Biomedical Sciences, females accounted for 4624 (72.5%, but 4.5% of total), and males accounted for 1755 (27.5%, but 3.3% of total). Of the 4322 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Computer and Information Sciences, males accounted for 2813 (65.1%, but 5.3% of total) and fe- males accounted for 1509 (34.9%, but 1.5% of total). Of the 3259 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Engineering, males accounted for 2362 (72.5%, but 4.4% of total), and fe- males accounted for 897 (27.5%, but 0.9% of total). Of the 876 bachelor’s degrees awarded to Blacks in Mathematics and Sta- tistics, males accounted for 458 (52.3%, but 0.9% of total), and females accounted for 418 (47.7%, but 0.4% of total) (Table 2; also see Eugene & Clark, 2012: pp. 45-46). For master’s degrees, during the 2007-2008 academic year, Blacks earned 31.6% in Business; 27.7% in Education; 9.4% in Health Professions and Related Clinical Sciences; 4.5% in Psychology; 2% in Social Sciences and History; 1.9% in Engi- neering and Engineering Technologies; 1.7% in Computer and Information Services; 1% in Visual and Performing Arts; and 0.9% in Biological and Biomedical Sciences6. Research has shown that females are gaining grounds in academic fields that were once dominated by males (England et al., 2007; also see Perna et al., 2009: p. 2). According to Table 3, of the 6571 First-Professional degrees awarded to Blacks in 2008-2009 academic year, females accounted for 4071 (62%) and males accounted for 2500 (38%), with females having more degrees in 9 of the 11 academic fields listed. Among the vari- ous academic fields listed in Table 3, Blacks earned 3162 de- grees in Law, with females accounting for 1990 (62.9%), and males accounting for 1172 (37.1%). Of the 1095 degrees awarded to Blacks in Medicine, females accounted for 696 (63.6%), and males accounted for 399 (36.4%). Of the 835 degrees awarded to Blacks in Theology, males accounted for 459 (55%), and females accounted for 376 (45%). Of the 801 degrees awarded to Blacks in Pharmacy, females accounted for 531 (66.3%), and males accounted for 270 (33.7%). Of the 275 degrees awarded to Blacks in Dentistry, females accounted for 180 (65.5%), and males accounted for 95 (34.5%). Of the 150 degrees awarded to Blacks in Osteopathic Medicine, females accounted for 107 (71.3%), and males accounted for 43 (28.7%). Of the 94 degrees awarded to Blacks in Chiropractic Medicine, females accounted for 66 (70.2%), and males ac- counted for 28 (29.8%). Of the 75 degrees awarded to Blacks in Veterinary Medicine, females accounted for 63 (84%), and males accounted for 12 (16%). Of the 40 degrees awarded to Blacks in Optometry, females accounted for 32 (80%), and males accounted for 8 (20%). Of the 39 degrees awarded to Blacks in Podiatry or Podiatric Medicine, females accounted for 28 (71.8%), and males accounted for 11 (28.2%). Of the 5 degrees awarded to Blacks in Naturopathic Medicine, males accounted for 3 (60%), and females accounted for 2 (40%) (Table 3). For doctorate degrees, during the 2007-2008 academic year, Blacks earned 36.8% in Education; 11.7% in Health Profes- sions and Related Clinical Sciences; 9.2% in Psychology; 6.2% in Biological and Biomedical Sciences; 5.8% in Business; 4.7% in Social Sciences and History; 3.6% in Engineering and Engi- neering Technologies; 2.4% Physical Sciences and Science Tech- nologies; 1.1% in Visual and Performing Arts; and 0.8% in Computer and Information Sciences7. Solorzano (1995) points out that from 1980 to 1990, a total of 278,905 doctorates were produced by United States universi- ties. Among the 106,592 doctorates awarded to women during that period, 5823 (5.5%) were Black American women. Among the 172,313 doctorates awarded to males, 5394 (3.1%) were Black American males. Black American females earned an ave- rage of 12.1% of the 30-to-34-year-old female cohort, while their male peers earned an averaged of 10.6% of the total male cohort during that same period (p. 18; also see Perna et al., 2009: p. 2). Of the 11,217 doctorates earned by Black Americans from 1980 to 1990, Black females comprised 52 percent (p. 19). The breakdown for individual majors is as follows: (Engineering; Black women, 288, Black men, 262); (Physical Science; Black women, 409, Black men, 331); (Life Science, Black women, 1004, Black men, 561); (Social Science, Black women, 2210, Black men, 1134); (Humanities, Black women, 960, Black men, 487) (Education, Black women, 5533, Black men, 2216); (pro- fessional degrees, Black women, 813, Black men, 403) (Solor- zano, 1995: p. 19). In 2002, among US citizens, of the doctorates awarded to Blacks, women received 63.1%, and 36.9% for Black men: Hispanic, 56.5% for women and 43.5% for men: Asian, 45.2% for females and 54.8% for males: American Indian, 54.1% for females and 45.9% for males: White, 49.7% for females and 50.3% for men (Hoffer et al., 2003: p. 17). Hanson (2004) points out that Black females comprise a much larger percentage of Black American scientists (36%) than is the case for White females (22%) (p. 100). In 2009, of the 32,231 doctorates earned by US citizens and permanent residents, 6.9% were earned by Blacks. Of the 7783 doctorates earned in Life Sciences, 5.4% were earned by Blacks; 3.1% of the 4414 doctorates in Physical Sciences; 6.8% of the 5605 doctorates in the Social Sciences; 4.3% of 3148 doctorates earned in Engineering; 14.5% of the 5566 doctorates earned in Education; 4.3% of the 3880 doctorates earned in the Humani- 6“Table 26.2. Percentage of Degrees Awarded by Degree-Granting Institu- tions in the Most Popular Fields of Study, by Race/Ethnicity and Level o Study: 2007-2008,” 2010, July. “Status and Trends in Education of Racial and Ethnic Minorities,” National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved on May 23, 2012 from: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2010/2010015/tables/table_ 26_2.asp. 7“Table 26.2. Percentage of Degrees Awarded by Degree-Granting Institu- tions in the Most Popular Fields of Study, by Race/Ethnicity and Level o Study: 2007-2008,” 2010, July. Status and Trends in Education of Racial and Ethnic Minorities. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved on May 23, 2012 from: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2010/2010015/tables/table_26_ 2.asp. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 72  A. J. KABA Table 3. First-professional degrees awarded to Black Am ericans, by sex and field of study: 2008-2009 . Both sexes Males % Females % All fields, total 6571 2500 38 4071 62 Dentistry (D.D.S. or D.M.D.) 275 95 35 180 66 Medicine (M.D.) 1095 399 36 696 64 Optometry (O.D.) 40 8 20 32 80 Osteopathic medicine (D.O.) 150 43 29 107 71 Pharmacy (Pharm. D.) 801 270 34 531 66 Podiatry (Pod. D. or D.P.) or podiatric me d icine (D.P.M.) 3 9 11 28 2 8 72 Veterinary medicine (D.V.M.) 75 12 16 63 84 Chiropract ic medicine (D.C. or D.C.M.) 94 28 30 66 70 Naturopathic medicine 5 3 60 2 40 Law (L.L .B. or J.D.) 3162 1172 37 1990 63 Theology (M. Div., M.H .L., B.D. , or Ord.) 835 459 55 376 45 Note: Source: “Table 306. First-professional degrees conferred by degree-granting institutions, by sex, race/ethnicity, and field of study: 2008-2009,” 2010. Digest of education Statistics. National center for education statistics. retrieved on 23 May 2012 from: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_306.asp. ties; 9.6% of the 1835 doctorates earned in other non-Science and Engineering fields8. In 2009, there were 2221 Black citizens or permanent resi- dents who earned doctorates. Of that total, 420 (18.9%) were in the Life Sciences; 135 (6.1%) in the Physical Sciences; 380 (17.1%) in the Social Sciences and Psychology; 134 (6%) in Engineering; 809 (36.4%) in Education; 167 (7.5%) in the Hu- manities; 176 (7.9%) in other non Science and Engineering fields9 (also see Ballard & Cintrón, 2010: pp. 12-13). It is useful to point out that Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) award more science and engineering degrees to Blacks than other higher education institutions. Ac- cording to Hamilton (2004), “In the battle to increase the num- bers of African American Ph.D.s in science, technology and engineering, the nation may just have a secret weapon: histori- cally Black colleges and universities” (p. 26). Of the 15 col- leges and universities that awarded the most number of engi- neering degrees to Black students from 1998 to 2002, Histori- cally Black Institutions were in the top eight (Chew, 2004: p. 32; also see Morris et al., 2012). According to the JBHE (2008): “The nation’s historically black colleges and universities produce about one of every six African-American stu- dents who earn a bachelor’s degree in the United States. Thirty years ago, black colleges produced about a third of all African Americans who earned bachelor’s degrees. This decline is not because black colleges are turning out fewer graduates but because predominantly white institu- tions are now enrolling and graduating far greater num- bers of black students. But in one important area the black colleges are havi ng a greater impact than before. A new r e- port from the National Science Foundation finds that black colleges and universities are producing a greater share of graduates who go on to earn Ph.D.s in science and engineering than was the case in the past. In 1990, of all blacks who earned Ph.D.s in the fields of mathematics or science, 21 percent were graduates of historically black colleges and universities. In 2006, the latest year for which data is available, black colleges were the feeder schools for 29 percent of African Americans who earned doctorates in these fields. The eight colleges and universi- ties that produced the most African-American graduates who went on to earn Ph.D.s. in mathematics or science in the 1997 to 2006 period are all historically black colleges and universities” (Anonymous, 2008: p. 35). The JBHE (2008) adds that these ten HBCUs and two non- HBCUs awarded undergraduate degrees to Black American students who went on to earn a doctorate in Mathematics or Science from 1997 to 2006: Howard University (224 students); Spelman College (150 students); Hampton University (135 students): Florida A & M University (100 students); Morehouse College (99 students); North Carolina A & T State University (89 students); Southern University—Baton Rouge (88 students); Xavier University of Louisiana (79 students); Harvard Univer- sity (non-HBCU, 73 students); University of Maryland (non- HBCU, 72 students); Tuskegee University (71 students); and Morgan State University (64 students) (Anonymous, 2008: p. 35)10. (also see Pyrtle and Whitney, 2008). According to Perna et al. (2009): 8“Table 22. US citizen and permanent resident doctorate recipients, by race/ethnicity and major field of study: 2009,” 2010. Doctorate Recipients from US Universities. National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 12 May 2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/data_table.cfm. 9“Table 20. Doctorate recipients by citizenship, race/ethnicity, and subfield of study: 2009,” 2010. Doctorate Recipients from US Universities. National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 12 May 2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/ statistics/nsf11306/app endix/pdf/tab20.pdf. 10Anonymous (2008). “Black Colleges and Universities Are Graduating an Increasing Share of African Americans Who Earn Ph.D.s in Mathematics and Science,” The Journal of Bl acks in Hi g her Education, Issue 61, p. 35. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 73  A. J. KABA “… colleges and universities that serve predominantly Black populations and/or women appear to be dispropor- tionately effective in promoting the educational attain- ment of these groups overall, and in STEM fields in par- ticular… of the top 20 leading producers of African American bachelor’s degrees in STEM [Science, Tech- nology, Engineering, and Mathematics] fields, all but three are HBCUs… nationwide in 2004, HBCUs were the source of 22% of all bachelor’s degrees to Blacks but 30% of the bachelor’s degrees to Blacks in STEM fields. HBCUs are also a relatively more important source of STEM degrees for Black women than Black men. Analy- ses of IPEDS data also reveal that 33% of the bachelor’s degrees awarded to Black women in STEM fields in 2004 were from HBCUs, compared to only 26% of the bache- lor’s degrees in STEM fields for Black men” (p. 5). While Black students have made real gains in science and engineering in the United States, many scholars and other au- thors have highlighted the low rates of degree attainment in many of those academic fields by Black students. The next section of this article will focus on these two contradictory aspects of the gradual progress of people of Black African de- scent in science an d engineering education in the Unit e d States. Factors Responsible for Gains in Earned Science and Engineering Degrees by Black American Females and Males and Factors Respo n sible for Their Slow Growth in the Gains in Science and Engineering Degrees In attempting to understand the progress of Black Americans in science and engineering education, one must examine it in two forms. First, compared to 1900, 1950 and 2000, Black Americans have made substantial progress in science and engi- neering education. Second, a closer examination of the data also reveals that relative to the over 42 million Black Ame- ricans by 2011, these numbers are not large enough. Also, rela- tive to other racial groups in the United States, Black Ameri- cans are earning fewer science and engineering degrees. This section of this article will then present examples from both perspectives. Factors Responsible for Gains in Earned Science and Engineering Degrees by Black American Females and Males Among the factors responsible for the success of Black Americans in science and engineering is that Black American parents continue to encourage their daughters and sons to enroll in these academic fields. For example, according to poll results of 1000 parents released by the US Department of Education on March 16, 2004, nearly 75% of the Black American parents surveyed rated science as “very important” to their child’s edu- cation. Moreover, 71% of those parents said that science educa- tion was crucial in a globally competitive workforce (US De- partment of Education, 2004: p. 1; also see Williams, 2004). In addition, Smith (2003) presents other factors that have helped to ignite interests in science and engineering among minorities and Black Americans in particular. According to Smith (2003), part of the reasons for the increasing interest in science by mi- norities is that “… many foundations and governmental agen- cies are beginning to take proactive stances by helping colleges and universities with their efforts to produce more mathematic- cians, scientists, and engineers” (p. 62). Smith (2003) adds that these organizations provide financial support and other kinds of services such as job internships, mentoring and research to universities for the purpose of introducing programs that ad- dress the problems of low representation of minorities and women in engineering and other science programs (p. 62). It has been noted that Black students have succeeded in the top colleges and universities in the United States while major- ing in challenging academic fields. Barinaga (1998) points out that, Black students have shown great success in the nation’s top universities by majoring in “tough majors.” Barinaga (1998) notes that at such institutions, 20% each of Black and White students majored in science and engin eering” (p. 1778). In explaining why some Black American males are excelling in engineering, Smith (2003) points out that persistence play an important role. According to Smith, a big difference between persistent and non-persistent students is that non-persistent students allow negative experiences, perceptions or attitudes to affect their drive and academic performance. In the case of the Black male students in Smith’s (2003) study, their “… spirit of the prove-them-wrong syndrome” is crucial in their success. In Smith’s (2003) study, those Black male students who succeed in engineering “developed coping mechanisms that manifested into positive vigor in spite of adversity” (p. 65). The students held a belief that they controlled their destiny in the pursuit of their engineering degrees, and that they “… assumed a more assertive academic posture and a stronger sense of purpose, commitment, and confidence in their academic persistence and performance” (p. 66). Smith (2003) quoted one Black American male engineering student as saying: “Being poor in college really hurts you... I remember one semester, for at least four weeks, I didn’t have many of my books, so I used to go to the bookstore and read my homework assignments. There are a lot of factors that you have to overcome to be successful in aca- demics” (p. 66). Another Black male engineering student was quoted as saying: “You have to have tenacity and dedication in engineering. You also have to make sacrifices, like when you choose to complete your engineering project versus going to play basketball” (p. 66; also see Davis, 1999; Hurtado et al., 2009: pp. 205-208). As the data above has illustrated, the gains in enrollment and degree attainment in science and engineering by women have also contributed to the increase in the number of these degrees in the Black American population, since women were influ- enced by society to major in non-science and engineering aca- demic fields. According to Perna et al. (2009): “Other research suggests the historical and current role of women’s colleges in promoting the attainment of women in science and engineering careers. In an historical ex- amination of Mount Holyoke Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College) between 1837 and 1941… the institu- tion’s success in educating women for science careers was attributable to an institutional climate where focusing on science was “the norm.” Among the important character- istics of this climate were the presence of substantial numbers of women who served not only as institutional leaders and faculty but also as role models, the college’s reputation as a leader in providing science education, the tendency of students interested in science to choose to at- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 74  A. J. KABA tend the institution, and the college’s “collaborative re- search orientation”… “the relatively high” rate of entrance into science careers among students who graduated with a science or math major from one women’s college suggests the positive role of single-sex colleges in promoting the attainment of women in STEM careers” (p. 5). According to Malcom and Malcom (2011): “In 1975, women earned just below 20 percent of all doc- torates awarded to African Americans, Latinos, and Ame- rican Indians. By 2008, this figure had risen dramatically, to more than 57 percent… White women, however, con- tinue to earn less than half of STEM doctorates awarded to the White population. Though the fact that minority women earn a majority of STEM doctorates awarded to underrepresented minorities appears to be positive on its face, much of this progress is an artifact of the minority male crisis in higher education; there is a significant de- cline in participation levels and degree attainment, espe- cially among African American males… For example, African American women achieved parity with their male counterparts in receipt of MD degrees in the late 1980s; but these women now constitute a supermajority, receiv- ing over 66 percent of total MDs awarded to African Americans in the class of 2010…” (pp. 166-167). In addition, the increase in the foreign-born Black population in the United States from Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, Asia and Latin America have also contributed to the visible increase in the attainment of science and engineering degrees by Black Americans. For example, from 1999 to 2001, of the 34,649 non US-citizen doctorate recipients in the United States, 1515 (4.4%) were from Africa, and from 2002 to 2008, of the 89,323 non US-citizen (excluding Permanent Residents) doctorate recipe- ents in the United States, 3305 (3.7%) were from Africa. Also, there were 37,796 students from sub-Saharan Africa in the United States during the 2007-2008 academic year (Kaba, 2011a: p. 188; also see Baker & Lutz, 2009). One major criticism of women, minorities and Blacks in par- ticular in higher education in the United States has been that they tend to earn most of their degrees in the field of education and not the “hard sciences” or engineering. McKillip (2001) notes that: “… minority graduate students have traditionally not done doctoral work in the sciences and humanities but have concentrated in education” (p. 2). Kulis et al. (2000) note that: “Black students earning doctorates remain heavily concentrated in just a few fields, especially education, psychology, certain social sciences, and biology” (p. 191). Kulis et al. (2000) con- tinued by explaining that in 1976, 59% of doctorates awarded to Blacks were in education, and that by 1995, it declined to 42 percent. In the natural sciences, they note that the figures were small in both percentages and actual numbers. “Even in the early and mid-1990s, fewer than a dozen black Ph.D.s gradu- ated annually in the fields of physics/astronomy, geoscience, mathematics, and most branches of engineering” (p. 191). Throughout the 1980s 2092 Ph.D.s were awarded in computer science and that Black students earned only 14 of that total (p. 191). Some authors have observed, however, that there have been so much emphasis placed on achievement in science and engi- neering that many predominantly Black schools lack the neces- sary numbers of teachers. Writing on the decline of the number of minority school teachers, Place et al. (1996) point out that just as a lower proportion of Black students enroll in college, so also are fewer of those in college major in the field of education. They point out that the proportion of Black undergraduate stu- dents who majored in education declined from 23% in 1966 to 6.8% in 1978 (p. 44). Place et al. (1996) also claim that per- sonal satisfaction was among the reasons provided by minority students for majoring in education (p. 48). Shipp (1999) also adds that education majors choose their careers in order to con- tribute to society (p. 346). According to Shipp (1999), research shows that the decline in enrollment of Black students in edu- cation is due to the increase in career opportunities that are now available in other fields “… considered more lucrative and prestigious than teaching” (p. 343). Shipp (1999) notes of one major negative stigma that has been placed on Black students who major in the field of education: “Furthermore, to many of today’s African American college students, a career in teaching is perceived as a career of a bygone era that reflected a lack of options…” (pp. 343-344). Thompson (1994) points out that Black students attaining master’s degrees in education declined by a third between 1981 and 1991, but the number of those who majored in engineering increase by 80 percent. For those majoring in master’s degree programs in business, their numbers increased by 50%, while it increased by 18% for those in master’s in health-related profes- sions (p. 10). Factors Responsible for the Slow Growth in the Gains in Science and Engineering Degrees by Black Americans Scholars and authors have pointed out, however, that despite the progress Black Americans have made in higher education, they continue to lack adequate representation in a number of important fields including science and engineering. Solorzano (1995) points out that “… Blacks are underrepresented in all fields of graduate school, especially the sciences and engineer- ing…” (p. 16). Kulis et al. (2000) point out that: “Although black students are earning an ever expanding share of bacca- laureate degrees granted in the United States, most fields show only minuscule improvements in their sparse representation among graduate degree recipients” (p. 187). According to Perna et al. (2009): “Even with this growth, however, African Ameri- cans continue to represent a smaller share of bachelor’s degree recipients in science and engineering fields than of all bache- lor’s degree recipients… Moreover, the representation of Afri- can Americans declines as degree level increases” (p. 2; also see Eugene & Clark, 2012: pp. 45-48). An extensive research of scholarly or academic articles by this author identified over two dozen interrelated or intercom- nected factors that have been cited for what many consider a slow rate of progress by Blacks in science and engineering education in the United States. Among these interrelated factors are: the history of Slavery of Black Africans and Jim Crow in the United States and the entire Americas and Colonialism in Africa; wealth accumulation or family income/poverty; inade- quate scientific equipments or tools or facilities; admission policies; weeding out of science courses; hidden curriculum; culture; faculty mentor; research experience; financial support such as grants; retention; science and engineering climate, cul- ture or environment for Black students; feeling of not belonging; scientific self-efficacy or academic sense of self; college major Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 75  A. J. KABA choice; personal drive or efforts; high school preparation or achievement in science and engineering; early interest as a young person and aspirations; peer support or collaboration with peers or faculty; social and racial stigma; science stigma; psychological barriers; academic support services or enrich- ment programs; family and community support; family aca- demic background including science and engineering or parents involvement; science and engineering mentorship and role models; and networking or outreach (Ashby, 1964; Beoku- Betts, 2004; Bozick, 2007; Eugene & Clark, 2012; Green & Glasson, 2009; Haynes, 2002; Hurtado et al., 200 9; JBHE, 2002; Kerlin, 1995; Kulis et al., 2000; Livingston & Wirt, 2004; Mal- com & Malcom, 2011; Ma, 20091; Marra et al., 2012; Mullen, 2003; Ong et al., 2011; Perna et al., 2009; Porter and Bronzaft, 1995; Shipp, 1999; Slaton, 2010; Slovacek et al., 2011; Smith, 2003). Let us examine some of these factors. In some instances some of these interrelated factors are merged. History of Slavery of Black Africans and Jim Crow in the United States and the Entire Americas and Colonialism in Africa Due to Slavery, Jim Crow and Colonialism, most Blacks in the United States were prevented by law to attain education. This means that once they had the opportunity, it would take a substantial period of time for them to catch up especially with their White counterparts. Even when they began attending schools after the Civil War, many of the Black schools lacked the types of academic equipments, resources and facilities (such as biology, physics and chemistry laboratories) needed to be successful or proficient in science and engineering. The inte- gration of schools and colleges in the post-World War II period helped to improve their condition, but as the data show, to be forced to start several hundreds of years behind all racial groups makes it extremely difficult to catch up. Black people in Africa and other parts of the world and people in the developing world also experienced similar situation where lack of school materi- als led to underperformance in science and engineering, but they were very successful in producing social scientists or hu- manists (Ashby, 1964; Beoku-Betts, 2004; Slaton, 2010). For example, Beoku-Betts (2004) claimed that the continuous poor quality of science education and the insufficient numbers of professors in African universities are significant contributors to the lack of inadequate numbers of scientists in those African societies. “On many university campuses, classes are overcrow- ded and students have to stand outside lecture halls or report early to their classrooms in order to secure a seat” (pp. 117- 118). Smith (2003) points out that among the many explana- tions that have been provided for the under representation of Black American males in particular in science, mathematics and engineering is “inadequate secondary education facilities and resources” (p. 62). In their study of minority students and their involvement in science and engineering education, Hur- tado et al. (2009) present this account of a Black student from Xavier University, an HBCU located in New Orleans, Louisi- ana: “A student at Xavier spoke of the frustrations he has had in dealing with others who underestimate the value of his education at an HBCU. While he attended another institu- tion after Hurricane Katrina, he found himself talking about different types of campuses with peers at his surro- gate university: ‘[T]hey brought up the difference between HBCUs and Ivy League schools or regular schools and that’s when it first hit me I guess… generally HBCUs may not get as much funding as state [schools or other places], so they’re not as equipped as other schools and you see that. When I went from… the lab in Xavier’s classroom… to [a university in Texas] and I go to the lab in their classroom, they [had] an in- cubator almost the size of half of our class [at Xa- vier]… so there’s definitely a difference.’” (pp. 206- 207). Haynes (2002) notes that because it was relatively recently that higher education was mostly closed off to people of color, it should not be a surprise that so few of them sought doctorate degrees in programs such as biology, physics or computer sci- ence. Instead, according to Haynes, they choose degrees in “… business/management, engineering, law and medicine—careers that often posses deeper historical ties to communities and a tradition of advocacy for social and political change for all Americans” (p. 4). According to the JBHE (2002), throughout the history of the United States, it is unlikely for one to find Black Americans on any list of potential young scientists. Part of the reason is that for a long period of time, Blacks were al- most absent in the hard sciences in graduate programs. “Instead, young blacks with scientific inclination were funneled into graduate programs in education where in many cases they would be trained to teach other blacks” (p. 55; also see Slaton, 2010). For those Blacks who majored in the hard sciences, they enrolled mostly in medical school where they were trained as physicians to care for other Blacks in the inner cities or the rural Southern United States. “Rarely was a black person en- couraged to pursue doctoral studies in physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, mathematics, or computer science” (JBHE, 2002: p. 55). Wealth Accumulation or Family Income/Poverty Just as participating in certain sports (example, Golf and Polo) can cost substantial amounts of money or financial in- vestments, so too one must expect to invest in studying science and engineering fields. According to Kaba (2008), of the 37 million people in poverty in the United States in 2004, 9 mil- lion (24.3%) were Black (pp. 316-317; also see Kaba, 2011b). In 2009, of the 96.190 million households with White males, 20.216 million (21%) had income under $10,000; 35.137 mil- lion (35.4%) out of 99.380 million households with White fe- males; 6.167 million (38.4%) out of 16.054 million households with Black females; and 5.020 million (37.7%) out of 13.314 million households with Black males11. Livingston and Wirt (2004) point out that in 1999-2000, high school students in high poverty schools were more likely than their peers in low-poverty schools to be taught English, Science, and Mathematics by teachers without a major in the field. It was a similar situation with students in high-minority schools compared with their peers in low-minority schools (p. 14). Ac- 11“Table 705. Money Income of People—Number by Income Level and by Sex, Race and Hispanics origin: 2009,” 2011. Statistical Abstract of the United States. US Census Bureau. Retrieved on 7 June 2012 from: http:// www.census.gov/compend i a/statab/2012/tables/12s0705.pdf. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 76  A. J. KABA cording to Eugene and Clark (2012), “One factor is that learn- ers of African descent do not always begin at the same place as middle-class White students” (p. 47; also see Bozick, 2007; Mullen et al., 2003). Ma (2009) points out that: “Cumulative research has highlighted the consistent role of family SES [Socioeconomic Status] in maintaining educational advantages for children. In the area of educa- tional transition… research has found that family influ- ences remain strong at the higher levels of educational transitions. Within the same level of education, studies on secondary school tracking attest to the similar role of fam- ily SES in maintaining education advantages… Socio- economically advantaged parents can secure for their children the best positions within the educational tracking structure” (p. 213; also see Smith, 2003: p. 62). In is useful to point out that due primarily to economic hard- ship, in the 1980s, there was a significant decline in graduate degree attainment of Black Americans, especially Black males. In 1978, 4.3% Black Americans earned doctorates, and by 1993, it declined to 4.2 percent (Kerlin, 1995: p. 12). Porter and Bronzaft (1995) point out that: “From 1982 to 1992, the num- ber of Black men earning doctorates declined by 20%…” (p. 162). These declines have an impact on the rate of earned sci- ence and engineering degrees by Black Americans. Student-Faculty Relations/Mentorship and Role Models Student-faculty relations and mentorship have been cited as important contributors to improving the slow growth in the earning of science and engineering degrees by Blacks in the United States. Students can gain research experience with fac- ulty mentors and faculty can also serve as role models. Faculty mentors can also help students identify additional role models. In the instance of doctoral education, this could be identifying members of a student’s dissertation committee. As Ong et al. (2011) note, “The literature presented a mixed review of stu- dent-faculty relationships. For some women of color, their gender, race, and ethnicity were seen as major barriers to being perceived as serious students by their professors… For other women, professors played a critical role in making a STEM career a reality” (p. 185). Smith (2003) points out that another factor contributing to the slow progress of Blacks earning sci- ence and engineering degrees is “a shortage of positive mentors to promote their interests in mathematics, science, and engi- neering” (p. 62). Malcom and Malcom (2011) also point out that: “In the original publication of The Double Bind, a great deal of emphasis was placed on increasing the number of minority women postsecondary faculty in STEM fields. Doing so, it was believed, would result in a greater num- ber of role models for minority women (and for minority men and White women) undergraduate and graduate stu- dents pursuing STEM, thereby facilitating their retention, persistence, and degree completion. Census data from 1970, the only faculty data available at the time of the publication of the report, reveal that just over 1400 mi- nority women taught in the STEM fields in US colleges and universities” (pp. 167-168). According to Slovacek et al. (2011): “Multiple studies… stress the importance of student-fac- ulty interaction on retention and student success. As with the research experiences themselves, relationships with faculty mentors can aid in the incorporation of students into the academic/scientific community. For minority stu- dents whose mentor is also a minority, that relationship can serve as a powerful reminder that the prevailing stereotypes of minorities in the sciences can be overcome” (p. 6). It is noted that: “An important factor in increasing the num- ber of blacks in the sciences is the establishment of role models and mentors. Black faculty members in the hard sciences at our top universities serve to encourage black students to enter and succeed in these fields” (Anonymous, 2009: p. 36). Hurtado et al. (2009) present this quote from a male student in their study: “Indeed, participants across all focus groups were quick to acknowledge the role of research programs in allowing them not only to gain experience, but to do so at a high level, perhaps higher than what they would otherwise be afforded. According to a male… student: I mean, it’s not like we wouldn’t ever have been able to get experience in a lab without the MARC or IMSD programs… but… they definitely provide us this research experience… it’s a more directed re- search experience. Instead of just helping out some dude with his research, we’re being taught this with the intent of us eventually being the ones coming up with these questions, writing these grants, and sub- mitting papers for publication” (p. 198). Of the 1986 Black American citizens and Black permanent residents who earned their doctorates in 2009 in the United States, 11.9% had research assistantships/traineeship; 22.2% out of 22,933 White citizens and White permanent residents; and 32.1% out of 2514 Asian American citizens and Asian American permanent residents. Also, 9.5% of Black citizens and Black permanent residents had teaching assistantships; 17.8% for White citizens and White permanent residents; and 14.8% for Asian American citizens and Asian permanent resi- dents12. Perna et al. (2009) present this account about Spelman Col- lege (an all Black women’s institution) students and their ac- cess to role models: “After enrolling, students continue to see examples of Spelman’s success in educating African American women in STEM fields. For example, a few participants note that some faculty members illustrate Spelman’s success by in- viting alumnae ‘to come back and tell the other sisters what they are doing now.’ Among other potential benefits, these alumnae visits convey to current students that Spel- man provides high-quality preparation for graduate and professional school in STEM fields. In the words of a par- ticipating faculty member: We have students who come back and there’s al- ways talk about how students can look back and see 12“Table 32. Doctorate recipients’ primary source of financial support, by broad field of study, sex, citizenship, and race/ethnicity: 2009,” Doctorate Recipients from US Universities. National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 12 May 2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/appendix/pdf/ tab32.pdf. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 77  A. J. KABA that he or she [a particular instructor] was not that hard—they were demanding—but when they get there with students from other institutions they find out that they can compete, that they have been ex- posed to some of the same things” (p. 9). Perna et al. (2009) continue by presenting this account on support from faculty at Spelman College: “Participants uniformly report that Spelman’s faculty members ‘do everything they can’ to promote the attain- ment of African American women in STEM fields. A re- view of participants’ comments suggests at least five ways that Spelman faculty members encourage students’ aca- demic success. First, faculty members assume that all Spelman students in STEM courses can achieve their educational goals. In a representative comment from one faculty participant, ‘I feel that if they have been admitted to Spelman, they are capable.’ Second, faculty members not only believe that all Spelman women can be aca- demically successful but also intentionally work to ensure that students share this belief. A math professor suggests that such efforts are particularly important given stereo- types about women’s ability to be successful in math and science fields. In the professor’s words: I want to build their self-esteem and their self-con- fidence. Math is one of those fields that, sometimes, women can be intimidated by and I need to let them know that they can do math. They can do anything they set their minds to” (p. 13; also see Towns, 2010). Science and Engineering Culture/Climate and Sense of Belonging One of the most common factors cited as contributing to the slow success in science and engineering degree attainment by Black Americans is the culture, climate or environment of those academic fields, and Blacks’ sense of belonging in them—the ever prevalence of culture and race in human existence. Marra et al. (2012) point out that: “The perceived ‘climate’ in engineering programs con- tributes to students’ feelings of belongingness and can be either detrimental or enabling to their retention in those programs. Climate may be described in several ways. Campus climate refers to the attitudes, perceptions, and expectations associated with an institution… [they cited a group of scholars by explaining that] In engineering, … the term “chilly climate”… [describes] educational prac- tices and environments that treat women and men differ- ently and that have an adverse impact on women and oth- ers… Our finding of lack of belonging as a factor contrib- uting to students’ decisions to leave engineering may be related to students’ feelings of their self-efficacy (or the lack of efficacy) in engineering” (pp. 8 & 19). According to Hurtado et al. (2009): “The emergent ‘culture of science’ may inhibit the devel- opment of URM [Underrepresented Minorities] research scientists, especially when it affects their notions of com- petence that are central to their developing identity of ‘becoming a scientist’ (i.e., the potentially adverse impact of negative external messages on URM academic success). It is important to study how underrepresented students successfully navigate exclusion and their unique repre- sentation in science on their path toward becoming a sci- entist” (p. 193). Hurtado et al. (2009) point out that: “When describing the competitive nature within the culture of science, students high- lighted both positive and negative experiences. A number of students referenced how peers in different majors are more competitive than others” (p. 203). They continue by pointing out that: “Competitive and academically intimidating cultures of science were not unexpected given the reputation of scie- nce teaching and learning processes… Indeed, students further experience and face social stigma, particularly as it relates to their racial/ethnic background and aspirations as scientists. Students in our focus groups identified at least three types of stigma-related challenges they face that mainly refer to external, negative perceptions or judg- ments that others may hold of them. These include the negative associations stemming from students’ involve- ment in minority-based science research programs, feeling the general need to validate their academic competence as URM students, and the specific need to affirm their iden- tities as science students” (p. 204). Hurtado et al. (2009) point out that: “Another male student explained the uniqueness of at- tending an HBCU for him by recounting his transfer to Xavier from a predominantly White university: I felt so disconnected from everybody, not necessar- ily because it was a racial difference, but just the motivational factor. I didn’t feel motivated, I felt as if I was just a social security number, so I decided to come to Xavier and that’s when I felt at home, you know, because I got individual attention, I got moti- vation, I was able to see professors that were African American, biochemistry Ph.D. professors, people that look like me, which motivated me to say, ‘OK, I can do this. It’s possible for me not only to get an undergraduate degree, but also to pursue a higher level degree,’ so it’s the motivational factor that I would say an HBCU provides” (p. 207). On the issue of gender and science and engineering, Ong et al. (2011) note that: “Many of the studies we found highlighted measures of the STEM climate as central to the experience of women of color pursuing undergraduate STEM majors. Theoreti- cal discussions of climate-often described as ‘chilly’-ad- dressed evidence that women were treated differently from men by science faculty and peers… Yet the inclu- sion of racial and ethnic discrimination presents an ever more complicated environment for women of color. Sev- eral studies specifically demonstrated the gender and ra- cial/ethnic bias that women of color experience on a day-to-day basis as STEM majors, situating them in a unique position of confronting multiple systems of op- pression” (p. 182; also see Eugene & Clark, 2012: pp. 46- 47). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 78  A. J. KABA High School Preparation and Academic Course Selection High School preparation, including strategic course taking has been identified as a contributing factor to increasing the rates in enrollment and degree attainment in science and engi- neering degrees by Black Americans and students in general. Marra et al. (2012) point out that: “Preparation for difficult course material. Concerns re- garding students’ level of preparation for engineering pro- grams have been long considered in the literature… preparation in quantitative and analytical skills in high school was a strong indicator of interest in an engineering career… The perception that high school preparation is related to the academic factors is in alignment with prior research that shows the importance of students’ prepara- tion for studying engineering” (pp. 8 & 20). Hurtado et al. (2009) note of the students in their study: “A majority of the participants described their predispo- sitions toward science as occurring before college entry (although, as will be discussed later, the college experi- ence has greatly influenced students’ continued interest and retention in these fields). Many students had an initial fascination with some facet of science (e.g., stars or but- terflies developing in cocoons), which sparked intellectual curiosity at an early age. As one MIT female explained, ‘I was just always interested in how things worked and I al- ways… I guess I dreamed of getting to a point where I didn’t have to ask people how things worked… so I wanted to get the tools to be able to figure that stuff out on my own… As expressed by an MIT female student, ‘Along the way, I had a couple of teachers, particularly some female teachers, that really encouraged me to get into science and math.’ This encouragement offered by teachers perhaps strengthened students’ self-efficacy, en- couraging students to eventually pursue science majors in college” (p. 198). According to Perna et al. (2009): “Educational attainment in a STEM field depends, at least in part, on the adequacy of prior academic preparation and achievement. … efforts to ensure the readiness of the US workforce for the projected growth in science and engi- neering occupations must include improvements in K-12 math and science preparation. Two sources that contribute to low levels of math and science preparation especially for minority and low-income students are the insufficient availability of rigorous math and science coursework and a dearth of qualified math and science teachers in the high school attended…” (p. 3). According to Ong et al. (2011): “A common finding across empirical research on women of color in graduate STEM pro- grams is that the students were active, or planned on being ac- tive, in reaching out to other women-younger students and fel- low women of color-to draw them into and retain them in STEM fields” (pp. 195-196). Ong et al. (2011) also quoted a scholar discussing the efforts of a Black American doctoral student in engineering to motivate young high school students: “Grace believes in being a role model… for those coming up die ranks in engineering. She knows just how impor- tant it is to encourage younger women of color to fields in STEM. She is excited about teaching and embraces the challenge and joy that comes in helping others to realize their dreams as her own dreams become a reality” (pp. 195-196; also see Ma, 2009). It has also been noted that: “From an early age black students appear to be directed away from the study of the hard sciences. Many white teachers and guidance counselors continue to believe that black students do not possess sufficient cognitive abilities to comprehend advanced scientific concepts. As a result, African Americans are steered away from courses in which their teachers and counselors believe the black stu- dents would not be able to compete on a level playing field with their white peers” (Anonymous, 2009: p. 36). According to Smith (2003), another factor contributing to the underrepresentation of Blacks in science and engineering is “low expectations from teachers and school counselors regard- ing their academic abilities” (p. 62). Family and Community Support Family and community support are cited as contributing fac- tors to Black Americans’ effort to increase their degree attain- ment rates in science and engineering. According to Hurtado et al. (2009): “From not being expected to excel in the sciences, to not having full familial support, to being branded as a ‘sci- ence nerd,’ several students expressed the difficulties of developing a solid science identity. For instance, a male student… recounted: In my own experience, I find that… where I was raised, you weren’t expected to get a Ph.D. or any- thing like that. Just you were expected to work hard. You know, the best you could do was maybe get a job with the government, but that expectation wasn’t there. In fact, you were expected not to do that well… and everything was like a pecking order and then the guy that always got the straight A’s, he was the one that was going to go to med school or get his PhD or go into engineering, but that expectation was never there [for me]. And then when I started going to college, I started getting a lot more self-confi- dence in myself, especially when I saw how well I did in my classes. A female… student spoke about having to explain to her family her goals to pursue an advanced degree in science: “Why would you want to be in school that long? That’s too much hard work. Why would you do that?” is what I get from my family mostly, other than my mother… she’s gone to college, she’s the only one that’s gone to college… who can see that I should do more… more school is better, but I get a lot of the just… they don’t understand why I would want to do it. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 79  A. J. KABA A male Xavier student shared, “I guess in general with people, they seem to kind of have a puzzled look on their face when I tell them what I want to do. It’s like, ‘OK, a chemist. Really? Really?’” Another Xavier student talked about the reactions she has seen from friendly acquaint- ances: [T]he people at the beauty shop, they’re like, “So you’re going to be a doctor, right?” I’m like, “Yeah, I’ll be a doctor [as in Ph.D.]. Now if you get sick, I can’t help you. I mean, maybe I could synthesize some drug, and that’s a big maybe, but outside of that, you should go to the hospital,” and they’re like, “Oh, OK.” It’s like they don’t understand” (pp. 208- 209). According to Ong et al. (2011): “Family and community support is perhaps the most sali- ent and influential factor that women of color identify as encouraging to their completion of a STEM degree… Fa- milial support, however, can also be seen as a force that pulls women away from STEM. Some students found that their families questioned their long-term goals of becom- ing a scientist, and they also faced pressure to contribute to the family financially, to provide child care, and/or to uphold traditional female ideals of marrying and raising a family… science identity model for women of color stresses the importance of recognition by others as mean- ingful in women’s lives. These “others” could be those in the scientific community, but, for some women, their fa- milies and communities played a dominant role in how they saw and pushed themselves to succeed. One of the women in the study stated: We have the pressure from our communities, so it’s really hard for me to go home with bad grades. And that’s the pressure people of color have, is we have to bring something back to our community that will be helpful… They’re watching us. We have that pressure to do well. And that’s a good pressure” (pp. 186-187; also see Ma, 2009). Financial Support/Grants Financial support in the form of grants or graduate assistant- ships have also contributed to the slow growth in degree at- tainment in science and engineering by Black Americans. Ac- cording to Slovcek et al. (2011): “Financial support is of particular importance, given that while URMs are more likely to receive aid than their Caucasian or Asian peers, the aid they receive is on aver- age less… in investigating the factors related to retention in the engineering program at Michigan State University, reported that African American students on average worked twice as many hours outside the university to finance their education, which negatively impacted their studies as a result” (p. 6). Of the 1986 Black American citizens and Black permanent residents who earned their doctorates in 2009 in the United States, 32.9% had fellowships/grants; 28.8% out of 22,933 White citizens and White permanent residents; and 34% out of 2514 Asian American citizens and Asian American permanent residents. Also, 40% of Black citizens and Black permanent residents used their own resources to earn their degrees; 26.1% for White citizens and White permanent residents; and 15% for Asian American citizens and Asian permanent residents13. According to Perna et al. (2009): “Participants [in their study] identify four types of challenges that limit the educational and occupational attainment of Black women in STEM fields: aca- demic, psychological, social, and financial… Financial chal- lenges may be especially great for the small share of Spelman students who are “non-traditional,” e.g., commuting rather than residential students; students who are financially independent rather than dependent on their parents; and students who trans- fer into Spelman” (pp. 9-11). According to Ong et al. (2011): “The costs associated with graduate education (e.g., tuition, textbooks) as well as costs of living while in graduate school (e.g., housing, meals, and, in some cases, child care) are impor- tant factors in recruiting and retaining students in STEM” (p. 192; also see Ma, 2009). Personal Drive/Weeding Out Science Courses/Hidden Curri culum Finally, it has also been noted that Personal Drive, Weeding Out Science Courses, Admission Policies, and Hidden Cur- riculum all contribute to whether Black Americans make sub- stantial achievements in science and engineering education. Pertaining to Personal Drive, Ong et al. (2011) point out that: “… the personal agency and drive of women of color develop greatly during the undergraduate years. … African American women… expressed their persistence in math as having to do with personal interests and agency” (p. 88). According to Perna et al. (2009), studies have illustrated: “… that selfefficacy is positively related to students’ expectations of earning a bache- lor’s degree in engineering, interest in engineering-related ac- tivities, and plans to major in engineering” (p. 4). Pertaining to Weeding Out Science Courses, Green and Glasson (2009) point out that: Regardless of the factors, the talents of many African Americans who would have majored and persisted in sci- ence-related majors are wasted due to institutional factors that discourage their involvement at predominately white institutions. For example, many freshmen who declare scientific majors at predominately white institutions find themselves struggling due to a design that “weeds” them out… The design is hierarchical in nature because it is structured to only let the best students continue on, while simultaneously weeding out those students whose aca- demic abilities are allegedly deficient. These students ei- ther fail or change majors altogether… (p. 367). Finally, on the issue of a Hidden Curriculum, Green and Glasson (2009) also point out that: “The hidden curriculum includes influential messages about the norms of society and people’s positions within society, and many times these subtle messages accompany the required curriculum in many class- rooms” (p. 370). Green and Glasson (2009) quoted a scholar 13“Table 32. Doctorate recipients’ primary source of financial support, by broad field of study, sex, citizenship, and race/ethnicity: 2009,” Doctorate Recipients from US Universities. National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 12 May 2012 from: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/appendix/pdf/ tab32.pdf. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 80  A. J. KABA who noted that: “Since the hidden curriculum is taught (implicitly) through the kinds of participatory mechanisms that work so pow- erfully in out-of-school contexts, it is not surprising that sometimes the messages about social class and social roles in the hidden curriculum are understood by students more deeply than the messages about scientific concepts in the explicit curriculum…” (p. 370). Conclusion This article began by pointing out that Black Americans have made substantial progress in the post 1960s era. It claims that today Black Americans can be found in almost all important sectors of American society, including the office of the Presi- dency of the country. The article notes that the most important achievement of all is the substantial increase in the life expec- tancy of Black Americans. The primary reason behind this ex- traordinary progress of Black Americans is higher education attainment. The article presents college enrollment data of Black Ameri- cans, illustrating that by 2010, not only have their college en- rollment rates increased substantially, but that Black females are second only to Asian males in enrollment among all groups and sub-groups in the country. The college degree attainment data showed that by 2011, there are over 3.2 million Black people in the United States with at least a bachelor’s degree. The article also points out that Black Americans have made substantial gains in increasing their college enrollment and degree attainment rates in science and engineering. The article presents the factors responsible for this progress in science and engineering. Finally, the article also notes that although Black Americans have made substantial gains in science and engi- neering, their growth in these fields is relatively low compared with other racial and cultural groups in the country. A number of factors are then presented for this low growth in science and engineering college degree attainment of Black Americans. REFERENCES Ashby, E. (1964). African universities and western tradition. Cam- bridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Baker, P. R., & Lutz, A. (2009). How African American is the net black advantage? Differences in college attendance among immigrant blacks, native blacks, and whites. Sociology of Education, 82, 70- 100. doi:10.1177/003804070908200104 Ballard, H. E., & Cintrón, R. (2010). Critical race theory as an ana- lytical tool: African American male success in doctoral education. Journal of College Teaching and Learning, 7, 366-374. Barinaga, M. (1998). Graduate admissions down in minorities. Science, 281, 1778. doi:10.1126/science.281.5384.1778 Beoku-Betts, J. (2004). African women pursuing graduate studies in the sciences: Racism, gender bias, and third world marginality. NWSA Journal, 16, 116-135. doi:10.2979/NWS.2004.16.1.116 Bozick, R. (2007). Making it through the first year of college: The role of students’ economic resources, employment, and living arrange- ments. Sociology of Education, 80, 261-285. doi:10.1177/003804070708000304 United States Cens us Bureau (2011). Census women. URL (last checked 20 April to 26 April 2011). http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/education/cb10-55. html Chew, C. M. (2004). Howard University engineers success. Black Is- sues in Higher Education, 21, 30-32. Davis, L. E. (1999). Working with African American males: A guide to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. National Center for Education Statistics (1997). US Department of Education. URL (last checked 9 January 2012). http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=61 England, P., Allison, P., Li, S., Mark, N., Thompson, J., Budig, M. J., & Sun, H. (2007). Why are some academic fields tipping toward fe- male? The sex composition of US fields of doctoral degree receipt, 1971-2002. Sociology of Education, 80, 23-42. doi:10.1177/003804070708000102 Eugene, W., & Clark, K. (2012). E-learning, engineering, and learners of African descent: A needs analysis. Journal of STEM Education: Innovation and Research, 13, 45-57. Franklin, J. H., & Moss, A. A. (1994). From slavery to freedom: A history of African America n s (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Franklin, C. W., & Mizell, C. A. (1995). Some factors influencing suc- cess among African-American men: A preliminary study. Journal of Men’s Studies, 3, 191. Freeman, C. E., Snyder, T. D., & Connolly, B. (2005). The impact of degree field on the earnings of male and female college graduates. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13, 1-19. Glazer, N. (2003). Nathan glazer explains the Black faculty gap. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 40, 80. doi:10.2307/3134053 Green, A., & Glasson, G. (2009). African americans majoring in sci- ence at predominantly white Universities (a review of the literature). College Student Journal, 43, 366-374. Hamilton, K. (2004). Is there a doctorate in the house. Black Issues in Higher Education, 21, 26-29. Hanson, S. L. (2004). African American women in science: Experi- ences from high school through the post-secondary years and beyond. NWSA Journal, 16, 96-115. doi:10.2979/NWS.2004.16.1.96 Haynes, D. M. (2002). History: The missing link in making young scientists and scholars. Black Issues in Higher Educ ation, 19, 1-4. Herper, S., Rushani, D., & Kaufman, J. S. (2012). Trends in the Black- White life expectancy gap, 2003-2008. JAMA, 307, 2257-2259. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5059 Hoffer, T. B., Sederstrom, S., Selfer, L., Welch, V., Hess, M., Brown, S., Reyes, S., Webber, K., & Guzman-Barron, I. (2003). Doctorate recipients from United States Universities: Summary report 2002. Chicago, IL: National Opi n i on Re s e arch Center. Hurtado, S., Cabrera, N. L., Lin, M. H., Arellano, L., & Espinosa, L. L. (2009). Diversifying science: Underrepresented student experience in structured research programs. Research in Higher Education, 50, 189-214. doi:10.1007/s11162-008-9114-7 Anonymous (2008). Black colleges and universities are graduating an increasing share of African Americans who earn Ph.D.s in mathe- matics and science. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 61, 35. (2002). No African Americans on MIT’s list of 100 leading science and technology innovators. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 37, 55. (1996). A science degree is the big ticket for black college students. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Educ at io n, 30-32. Kaba, A. J. (2012a). Talented tenth: An analysis of the 2011 root magazine’s 100 most influential young Black Americans. Interna- tional Journal of Humaniti e s and Social Science, 2, 1-31. Kaba, A. J. (2012b). The exclusion of black women from national lead- ership positions in t he United States: Taxation with limited represent- tation. Sociology Mind, 2, 133-140. doi:10.4236/sm.2012.22017 Kaba, A. J. (2011a). The status of Africa’s emigration brain drain in the 21st Century. Western Journal of Black Studies, 35, 187-207. Kaba, A. J. (2011b). Explaining the causes of the black-white wealth gap in the United Sta tes. Sociology Mind, 1, 138-143. doi:10.4236/sm.2011.13017 Kaba, A. J. (2008). Race, gender and progress: Are Black American wo- men the new model minority? Journal of African American Studies, 12, 309-335. doi:10.1007/s12111-008-9043-8 Kaba, A. J. (2005). Progress of African Americans in higher education attainment: The widening gender gap and its current and future im- plications. Educati o n Policy Analysis Archives, 13, 1-34. Kerlin, S. P. (1995). Pursuit of the Ph.D.: “Survival of the fittest. Or is Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 81  A. J. KABA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 82 it time for a new approach? Education Policy Analysis Archives, 3, 1-30. Kulis, S., Shaw, H., & Chong, Y. N. (2000). External labor markets and the distribution of black scientists and engineers in academia. The Journal of Higher Education, 71, 187-233. Livingston, A., & Wirt, J. (2004). The condition of education 2004 in brief. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. NCES 2004-076. http:/ /nces.ed.gov/pubs2004/2004076.pdf Ma, Y. Y. (2009). Family socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and college major choices—Gender, race/ethnic, and nativity pat- terns. Sociological Perspectives, 52, 211-234. doi:10.1525/sop.2009.52.2.211 Malcom, L., & Malcom, S. M. (2011). The double bind: The next gen- eration. Harvard Education R evi ew, 81, 162-171. Marra, R. M., Rodgers, K. A., Shen, D. M., & Bogue, B. (2012). Leavi ng engineering: A multi-year single institution study. Journal of Engi- neering Education, 101, 6-27. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.tb00039.x Massey, W. E. (2003). Education dedicated to black males still relevant. Network Journal, 10, 38. McKillip, J. (2001). Affirmative action at work: Performance audit of two minority graduate fellowship programs, Illinois’ IMGIP and ICEOP. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 9, 1-21. Morris, V. R. Joseph, E., Smith, S., & Yu, T.-W. (2012). The Howard University Program in Atmospheric Sciences (HUPAS): A program exemplifying diversity and opportunity. Journal of Geoscience Edu- cation, 60, 45-53. doi:10.5408/10-180.1 Mullen, A. L., Goyette, K. A., & Soares, J. A. (2003). Who goes to graduate school? Social and academic correlates of educational con- tinuation after college. Sociology of Education, 76, 143-169. doi:10.2307/3090274 National Center for Education Statistics (1997). Minorities in higher education. Washington DC: US Department of Education Office of Educational Research and Improvement. National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. (2004). Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering. [NSF 11-309] (Report). Arlington, MA: Academic Institutions of Minority Faculty with Science, Engineering, and Health Doctorates. Ong, M., Wright, C., Espinosa, L. L., & Orfield, G. (2011). Inside the double bind: A synthesis of empirical research on undergraduate and graduate women of color in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Harvard Educational Review, 81, 172-207. Perna, L., Lundy-Wagner, V., Drezner, Noah D., Gasman, M., Yoon, S., Bose, E., & Gary, S. (2009). The contribution of HBCUS to the pre- paration of African American women for stem careers: A case study. Research in Higher Education, 50, 1-23. doi:10.1007/s11162-008-9110-y Place, A. W., Payne, C., & Rinehart, J. (1996). An investigation of rea- sons for professional career choice among African-American college students. Education, 117, 43-50. Porter, M., & Bronzaft, A. L. (1995). Do the future plans of educated black women include black mates. The Journal of Negro Education, 64, 162-170. doi:10.2307/2967239 Pyrtle, A. J., & Whitney, V. A. W. (2008). To attract, engage, mentor and sustain: Outcomes from the Minority Students Pursuing Higher Degrees of Success (MSPHD’S) in earth system science pilot project. Journal of Geoscience Education, 56, 24-32. School Enrollment in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. URL (last checked 11 January 2012). http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/education/cb12-t ps02.html Shipp, V. H. (1999). Factors influencing the career choices of African American collegians: Implications for minority teacher recruitment. The Journal of Negro Education, 68, 343-351. doi:10.2307/2668106 Slaton, A. E. (2010). Engineering segregation: The University of Maryland in the twilight of jim crow. Magazine of History, 24, 15-23. doi:10.2307/maghis/24.3.15 Smith, D. M. (2003). To prove-them-wrong syndrome: Voices from unheard African-American males in engineering disciplines. Journal of Men’s Studies, 12, 61-70. doi:10.3149/jms.1201.61 Solorzano, D. G. (1995). The doctorate production and baccalaureate origins of African Americans in the sciences and engineering. Jour- nal of Negro Education, 64, 15-32). doi:10.2307/2967281 Slovacek, S. P., Whittinghill, J. C., Tucker, S., Rath, K. A., Peterfreund, A. R., Kuehn, G. D., & Reinke, Y. G. (2011). Minority students se- verely underrepresented in science, technology engineering and math. Journal of STEM Education: Innova tions an d Research, 12, 5-16. Sullivan, O. R., & Haskins, J. (2001). African American Women scien- tists & inventors. New York: John Wil ey and Sons. Table 1 (2012). Enrollment status of the population 3 years old and over, by sex, age, race, hispanic origin, foreign born, and foreign- born parentage: October 2010School enrollment in the United States: 2010 United States bureau. URL (last checked 11 January 2012). http://www.census.gov/hhes/school/data/cps/2010/tables.html Table 66 (2011). Statistical profile of doctorate recipients, by race/ ethnicity and citizenship: 2009. Doctorate Recipients from US Uni- versities: 2009. URL (last checked 8 January 2012). http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/. Thompson, G. L. (1994). Engineering, business majors grow among blacks: But study finds deep disparities between enrollments, degrees. Black Issues in Higher Education, 11, 10-11. Towns, M. H. (2010). Where are the women of color? Data on African American, Hispanic, and Native American Faculty in STEM. Journal of College Science Teaching, 39, 8-9. Trusty, J. (2002). Effects of high school course-taking and other va- riables on choice of science and mathematics college majors. Journal of Counseling and Deve lo p m en t , 80, 464-474. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00213.x United States Department of Education (2004). African American par- ents consider science important part of children’s education. URL (last checked 13 February 2005 ). http://www.ed.gov/news/pressrelease/2004/03/03162004a.html Williams, B. (2004). Faces of science: African Americans in the sci- ences. School Library Journal, 50, 54. Anonymous (2009). Young Blacks Are Beginning to Break Negative Stereotypes of a Racial Deficiency in the Sciences. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 65, 36- 37.