Circuits and Systems, 2013, 4, 49-57 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/cs.2013.41009 Published Online January 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/cs) Thermal Defect Analysis on Transformer Using a RLC Network and Thermography Geoffrey O. Asiegbu¹, Ahmed M. A. Haidar², Kamarul Hawari1 1Faculty of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, University Malaysia Pahang, Kuantan, Malaysia 2School of Electrical, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia Email: geoffasi@yahoo.com Received August 2, 2012; revised September 2, 2012; accepted September 10, 2012 ABSTRACT Electrical transformers are vital components found virtually in most power-operated equipments. These transformers spontaneously radiate heat in both operation and steady-state mode. Should this thermal radiation inherent in trans- formers rises above allowable threshold a reduction in efficiency of operation occurs. In addition, this could cause other components in the system to malfunction. The aim of this work is to detect the remote causes of this undesirable ther- mal rise in transformers such as oil distribution transformers and ways to control this prevailing thermal problem. Oil transformers consist of these components: windings usually made of copper or aluminum conductor, the core normally made of silicon steel, the heat radiators, and the dielectric materials such as transformer oil, cellulose insulators and other peripherals. The Resistor-Inductor-Capacitor Thermal Network (RLCTN) model at architectural level identifies with these components to have ensemble operational mode as oil transformer. The Inductor represents the windings, the Resistor representing the core and the Capacitor represents the dielectrics. Thermography of transformer under various loading conditions was analyzed base on Infrared thermal gradient. Mathematical, experimental, and simulation results gotten through RLCTN with respect to time and thermal image analysis proved that the capacitance of the dielectric is inversely proportional to the thermal rise. Keywords: Thermal Radiation; RLC Thermal Network; Thermography; Defect Analysis 1. Introduction Sustainability is the intermediary that runs between manufacturers of electrical equipments and her end-users. For sustainability to achieve its desired goal, electrical power facilities should be able to satisfy the demands of the users. These does not mean that faults cannot occur in equipments at any given time, however, certain electrical faults can be avoided while causes of the rest can be mi- nimized if attention to thermal effect is considered with utmost importance. In order to throttle thermal variations in transformers within a safe-steady-state, such current dependent equipments also known as thermal producers should be monitored and assisted to function efficiently within their life span. The aim of using the Resis- tor-Inductor-Capacitor Thermal Network (RLCTN) is to track equipments exceeding thermal rise as early as pos- sible by examining effects of thermal capacitance and thermal resistance on oil transformers. Secondly, to de- velop a mathematical model that helps in the study of thermal characteristics of oil distribution transformer components. Nearly every component gets hot before it fails [1]. Therefore, abnormal thermal rise of even minor piece of component could result to sudden failure and great setback on production. So, causes of abnormal thermal rise have to be addressed without hesitation. Hence, RLCTN model is one of the appropriate measures taken to ensure equipment durability. Until date, many researchers have been battling with heat management in electrical equipments, which are a vital phenomenon affecting equipments performance, sustainability and overall system efficiency. Generally, increasing current 2 R that generates undesirable ther- mal consequence in electrical equipments mainly occur due to high current, and in some situations in the form of free convection during thermal variations in the internal and external surfaces of the current conducting parts un- der different electrical loads and environment conditions [2]. In many manufacturing operations, electrical power systems have been the fundamental pillars whose contri- butions cannot be overemphasized; adherence to IEEE thermal evaluation regulations [3] will create an enabling environment for electrical facilities to function maxi- mally. Obviously, most system faults were discovered when thermal variation significantly deviates from its normal thermal value(s). This can be figured out using delta T C opyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. 50 criteria (∆T) [4], which are of two folds first: The thermal value of equipment without thermal fault considered as reference point is compared with other ensemble equip- ment having similar load and similar environment condi- tion [5]. Next is where thermal variation (∆T) of electri- cal equipment is compared between equipment and its ambient temperatures [6,7]. In RLCTN, various thermal nodes will be examined and analyzed with respect to time until stability is maintained at certain thermal thre- shold value. The eagerness that lead to the RLCTN re- search came as a result of backdrops of some previous researches [8-11] on electrical defect detection where critical sustaining issues where neither properly ad- dressed nor attended at all. Thermal fault detection is one issue and detection of remote cause of the thermal fault is another, the latter thermal problem is the focus of this paper. At architecture design level, RLCTN will contribute to the development of mathematical algorithm to study the thermal characteristics of oil distribution transformers base on the Resistance-Inductance-Capacitance network [12]. The thermal fault model for transformers includes abnormal thermal gradient caused by failures of capaci- tance of dielectric property in the form of transformer oil, cellulose paper and other insulators. The second impact is in showing the application of RLCTN as a base foun- dation for extensive projects. To achieve the desired re- sult and bring the proposition of this work to a logical conclusion, this model is implemented into a simulator to study the effect of thermal events on the design of abnor- mal thermal detection mechanism in a soft-real-time en- vironment such as electrical power distribution substation. Common methods of fault localization are reviewed such as digital control and advanced signal analysis algo- rithms-based; this concentrates on the incorporation of digital control, communications, and intelligent algo- rithms into power electronic devices such as direct-cur- rent-to-direct-current converters and protective switch- gears. These, enables revolutionary changes in the way electrical power systems are designed, developed, con- figured, and integrated in aerospace vehicles and satel- lites [13], an active “collaboration” among modular com- ponents to improve performance and enable the use of common modules, thereby reducing costs was developed. The performance improvement goals include active cur- rent sharing, load efficiency optimization, and active power quality control. Artificial Intelligence (AI) was another method developed to monitor, predict and detect faults at an early stage in a particular section of power system. Here the detector only takes external measure- ments from input and output of the power system that was simulated using Artificial Neural Networks equiva- lent circuit developed to predict and detect fault [14]. Every electrical thermographic examination aimed at lightly scrutinizing appropriate electrical equipment in order to pinpoint defective components and make ambi- ent temperatures evaluations of the power distribution system. Should there be any thermal anomalies untimely detected and uncorrected, such can be potentially haz- ardous both to the equipment and to the user resulting to system shutdown or failure [15]. This work presents a heat management system using RLCTN algorithm for pre-fault analysis of transformers and other similar electrical equipments under various operating conditions. It was also targeted such that, the gap between system components and thermal defect monitoring against breakdown of system itself that defi- nitely affects production is timely bridged. Hence, pre- vention is better than cure. The proposed work takes the advantage of using simple components comprising resis- tors, inductors and capacitors electrically connected to model the thermal effect on distribution transformer components such as windings, core, and dielectrics dur- ing operation and steady state. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents an overview of RLCTN equivalent network and real time dynamic thermal gra- dient. RLCTN thermal gradient and frequency responds analysis and nodal analysis as it applies to transformer are explained in Sections 3 and 4. Section 5 is all about validation results and discussion of the proposed model while Section 6 concludes the work. 2. RLCTN Equivalent Analysis The RLCTN analysis is derived from a simple RLC elec- trical network. Table 1 shows the equivalence of con- cepts of the thermal RLCTN and the electrical RLC net- work. Taking current {I} to represent heat transfer rate q usually, current sources are heat producers, Volt- age {V} to represent Temperature Variation {T}, Resis- tance {R} represents the Thermal Resistance T, transformer oil and other dielectrics accounts for Ther- mal capacitance T THT Cwhich is the active heat absorber (storage) while the transformer radiators represents the passive heat absorber like heatsink. This analogy is pos- sible because the same Equations apply in each model. As an example: In Ohms law V = IR has an equivalent thermal Equation as qR . A thermal resistance represents the difference in tem- perature necessary to transfer a certain amount of heat; the unit for thermal resistance is ˚C/Watt. Physical prop- erties such as composition of the components in the sys- tem, shape, surface area and the volume of the compo- nents have big impacts on this value. A heat sink is de- signed as thermal radiators, is a passive heat absorber element that radiate heat to the ambient through the body of oil distribution transformer. This should have a mini- mal thermal resistance value so that it can transfer a sub- stantial amount of heat without requiring a large differ- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. 51 ence in temperature. Because of this, the air gap or space between the radiator fins, type of material and size are importantly considered. Capacitor in this thermal analy- sis network plays the role of active heat absorber meas- ured in Joule per degree centigrade, i.e., J/˚C. The ca- pacitance is a measure of the amount of thermal energy that is stored or removed to increase or decrease the thermal flow within the oil distribution transformer that depends largely on the heat absorbent or storage capacity, type of materials such as oil viscosity, quality of cellu- lous paper and conductor insulators, then volume and size of the oil container. The above analogy describes the thermal properties as a system of linear differential equa- tions that will be detailed in the subsequent sections of this paper; a popular technique widely adopted in most circuitries, mainly in electrical and electronic engineering designs. This very simple thermal RLCTN can analyze and predict the dynamic behavior of real-time oil distri- bution transformer as shown in Figure 1 [16]. 3. Thermal Gradient Analysis RLCTN approach is used for instantaneous thermal analysis of electrical distribution substation transformer. The idea of using RLCTN for analyzing thermal effect is Table 1. Comparison of thermal network to electrical net- work. Thermal Network Electrical Network Temperature (˚C) TVoltage V (Volt) Heat Transfer Rate q (Watt) Current I (Ampere) Thermal Resistance T (˚C/Watt) Resistance R (Ohms) Thermal Inductance T C T S T S Inductance L (Henry) Thermal Capacitance (J/˚C) Capacitance C (Coulomb/Volt) Temperature Source Voltage Source Heat Source Current Source Figure 1. Dynamic thermal gradient of oil transformer. not new but an analytical algorithm that describes every individual component with respect to the thermal char- acteristics of most current dependent or current sourcing equipment such as oil distribution transformer. In every electrical distribution substation, there exists lots of heat dissipating components comprising of instantaneous elements arranged for efficient generation of electric power. RLCTN as the name implies is reasonably less cumbersome and less complexity due to small number of components are used, which is quite imperative for on- line computation and for prediction of future thermal variations at all levels. This thermal analysis incorporates heat producers for example, transformer windings repre- sented as inductors; core represented as resistors and heat absorbers such as transformer oil, cellulous insulators and other dielectric materials represented as capacitors. This thermal model analysis focuses on second-order thermal networks, which are a set of component parame- ters that help to define the behaviors of individual com- ponents of the system (oil transformer) consisting of re- sistors, inductors and capacitors. By measuring the steps and thermal behaviors, the heat transfer functions can be determined. The ideology of RLCTN that depicts the thermal characteristics of oil transformer and its ambient temperature is diagrammatically illustrated in Figure 2. By varying the time and capacitance values, the circuit bode plot can be generated. Referring to Figure 2, RLCTN consist of a resistor of thermal resistance T, a coil of thermal inductance T, a capacitor of thermal ca- pacitance C and a temperature source S T connected in series. If the quantity of heat absorbed by the capacitor is Q and the rate of heat flow in the thermal network is T T q , the temperatures across T, TC qR , and T are; T, d d q L Tt andQ C T T respectively. Using thermal equivalent of Kirchhoff’s Law, the temperature difference between any two points has to be independent of the path used to travel between the two points; the Equation (1) is of the form: LL Q qT qTS C T tH ttTt T , , (1) Assuming that LC and S T are known, this is a differential equation in two unknown quantities, q TTT and . However, the two unknown quantities are Q T Figure 2. Ideology of RLCTN applied to transformer. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. CS 52 related by Copyright © 2013 SciRes. d d Q T q tt t so that, QS C tT t Q T LQ RQ T TT tTT tT (2) or, differentiating with respect to and then substi- tuting in Qq tH t d d T t, qS C tTt S T 0 sintEt Lq Rq H TH tTH tT (3) For an alternating temperature source , choosing the initial time so that 00 , SS TT and the differential equation is of the form, sin o t Et q Lq RqC H TH tTH tT sinA t (4) Taking general solution of (4) by considering q HPt with the thermal rise (A) and the thermal gradient to be determined. That is, guessing that the RLCTN responds to an oscillating ap- plied temperature source with a heat flow that oscillates with the same rate [17]. For q Pt to be a solution, temperature at node “P” (see Figure 2) has to be consid- ered in Equation (5) as, q Lq RqC HP THPt THPtt Tcos o E t (5) 2sin cos cos cos LR oo TA tTA t EtEt sin C At T (6) Hence, 2 1sin cossin sin L C oo TA tT T Et E cos R A t t sin t (7) Matching coefficients of cos t and on the left and right hand sides yields, 21 L C TA Tsin o E cos Ro TA E (8) (9) Now values of and A can be computed which is the thermal frequency and thermal gradient in the oil transformer analyzed in the RLCTN. Dividing Equation (8) by (9), 2 1 11 tan tan LC L RRRC TT T TTTT x T ,,mno R T ,,mno C T,, Rmno x T H ,,mno R (10) 4. RLCTN Nodal Analysis Applying nodal analysis to the RLCTN, this will make it possible to compute the heat flow rate at each junction of the RLCTN as a function of load and steady state, as- suming a linear relationship between load and power dissipated with respect to time. From Figure 3, let t be time, temperatures at node m, n and o at instant x. ,,mno the thermal resistance between nodes m, n, o, and the thermal capacitance at node m, n, o. the heat flowing through thermal resistance T between node m, n, o at instant x, the heat flowing through thermal inductance T , Cmn x T H T,,mno H H ,, ,,,, 0 CCL mno mno xxx TTTmno HHHH at instant x and ,othe heat flowing through thermal capacitance ,,mno C at instant x and is heat flow rate across the nodes [18]. For each node except the reference node (G), the rate at which heat is flowing,,mnoin and out of each node is expressed as the algebraic sum of the heat flowing in or out of a node equals zero. (By algebraic sum, it means that the quantity of heat flowing into a node is to be con- sidered as the same quantity negative heat flowing out of the node). (12) Equation (14) represents the conservation of heat energy, it means that heat can neither be created nor destroyed ra- ther can be converted from one form to another in a node hence heat cannot be bunched up. Expressing the heat at junction m and the entire junction o in terms of the nodal temperature at each end of the junction using Ohm’s Law VR thermal equivalent qR TT where q is the Heat flow rate, T is the temperature and T is the thermal resistance. Equation (13) is of the form, ,, ,, ,, Rmno mno mno x qT R T HT (13) 2 2 2 22 2 22 1 1 o LL o R LC R E TTTAEA TTT (11)  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. 53 Figure 3. RLCTN nodal analysis. As well, the resultant temperature can be computed as follows: ,, ,,mno mno xx T R THT ,, x mn T ,, mno (14) From Equations (13) and (14) above there is relation between the thermal resistance, temperature and heat flow rate. In other words, the rate at which heat flows downward out of node (m, n and o) for instance depends on the temperature difference o and the corre- sponding thermal resistance T,,mno Rcomponent at each junction. Taking the first order differential Equation, the heart flowing through thermal capacitors as well as their respective dissipated temperatures are computed as shown in Equation (15). Heat flowing through capacitor at node m, n and o is, ,, ,, d d mno Cmno x C TC T t ,,mno x HT (15) Equation (16) is a discrete variable from Equation (15). Equation (16) will be used to compute the temperature at instant x + 1 from the temperature at instant x. Equation (16) is constantly repeated for each interval ∆t, for all nodes in the system, until a threshold is reached at an instant. Equation (16) expresses the behavior and storage capacity of the energy component (capacitor) used in this model with respect to time, that is, the ability of the component to absorb heat under load and steady state. Equation (16) will be used to compute the temperature at instant x + 1 from the temperature at instant (x). To com- pute the temperature of a node, this process (Equation (16)) is constantly repeated for each interval ∆t, for all nodes in the system, until a threshold is reached at an instant. ,, ,, Cm n o mno x T oC 1 ,, ,, xx mno mn t T , TT (16) 5. Results and Discussion 5.1. Experimental Validation The experiment to validate this model involves the fol- lowing: a 3-phase electrical module of purely resistive, inductive and capacitive load with the following specifi- cations: 7 heating elements rated value 2 KW each, 7 inductors with rated value 2 KVA each and 7 capacitors with rated value 2 KVAR each (see Figure 4). There are 7 load steps ranging from step one to step seven, loads are increased after 300 seconds time interval. A Ti25 fluke thermal camera is used to obtain the thermal effect on the inductors and the corresponding thermal values respectively. Other numerical values such as heat flow rate and quantity of heat absorbed or removed by the dielectric (capacitance C) components are read through the external LCD on the module panel. The experimental numerical values are tabulated in Tables 2-5 as well as the graphical bode plot in Figures 4-9. Often times, vali- dation procedures suffer inconsistencies in the model, in the measurements, and in the assigned values of the con- stants. The mathematical model suggests that the tem- perature changes transiently. Corresponding bode plot are made on the collected Land C temperatures as well as the heat flow rate across nodes m, n, and o. It was observed that the graphs replicate what the mathe- matical model suggests. After the adjustments of the thermal capacitance parameters, the system was moni- tored closely with different loads, initial temperatures, TT T Figure 4. 3-phase electrical module of purely resistive, ca- pacitive and inductive load. Table 2. A RLC experimental thermal analysis result. Quantity of Heat (J ) Time (s) C T (j/˚C) R L C 0 149.4 10 0 10 300 132.8 20 5 20 600 116.2 30 5 30 900 83 40 5 40 1200 66.4 45 10 50 1500 49.8 55 10 55 1800 32.2 60 10 65 2100 16.6 60 10 65 Table 3. A LC experimental thermal analysis result. Heat Flow Rate (W) Time (s) C T (j/˚C) m n o 0 149.4 20 10 20 300 132.8 30 25 30 600 116.2 40 35 40 900 83 55 55 55 1200 66.4 65 60 65 1500 49.8 80 80 80 1800 32.2 95 90 85 2100 16.6 95 90 85 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. 54 Table 4. A LC experimental thermal analysis result. Quantity of Heat (J ) Time (s) C T (j/˚C) R L C 0 149.4 0 0 0 300 132.8 1 10 10 600 116.2 1 10 10 900 83 1 10 10 1200 66.4 2 20 20 1500 49.8 2 20 20 1800 32.2 2 20 20 2100 16.6 3 30 20 Table 5. A RL experimental thermal analysis result. Quantity of Heat (J ) Time (s) C T (j/˚C) R L C 0 149.4 20 30 3 300 132.8 40 60 5 600 116.2 90 60 8 900 83 80 120 11 1200 66.4 90 150 13 1500 49.8 110 180 15 1800 32.2 130 200 18 2100 16.6 130 200 21 Figure 5. Effect of heat absorbed by dielectric C T R T and core on the winding. Figure 6. Heat flow rate across nodes m, n, o in the RLCTN. different time intervals and different environment condi- tions. All the validations were much similar to the mathe- matical model. Figure 7. Effect of insufficient thermal resistance R T on the winding L. Figure 8. Effect of thermal capacitance degradation on the winding C T L. Figure 9. Thermal gradient with respect to time at . C,C 498J14 kWand14 CR L TT T T . The experimental values in Table 2 show the effect of varying the thermal capacitance on the RLC components, the higher thermal capacitance value the lower heat dis- sipation on the RLCTN components and vice vase. More explanation about this is graphically illustrated in Figure 5. This Figure shows the effect of quantity of heat ab- sorbed by the dielectric (C) components on winding (L). As defined in Section 2, the combination of thermal components: the dielectric materials Cand the core T resulted in logarithmic drop of winding tempera- ture T. Hence, more heat is been radiated to the am- bient through the transformer radiator as illustrated in Figure 2. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. 55 The values in Table 3 also show the effect of varying thermal capacitance on the thermal nodes (m, n, and o) as shown in Figure 3. This explains the higher thermal ca- pacitance the slower heat flow rate to the node junc- tions and vice vase. In the case transformers, this reduces the risk of arc flash between phases or phase and neutral [19-21]. Figure 6 replicates the nodal analysis method well defined in Section 3 and thermal equivalent of Kir- chhoff’s Law, stating that temperature difference be- tween any two points has to be independent of the path used to travel between the two points. Figure 6 graphi- cally illustrates that the heat flow rate across the nodes were linearly increased and stabilized at about 1750 sec time interval. In Table 4, it is seen that there was insufficient ther- mal resistance T C T T T which represent the transformer core. Here it was observed that the transformer winding (L) temperature increased to about 30˚C irrespective of the high thermal capacitance value . Figure 7 shows the graphical illustration. The experimental value in Table 5 shows the effect of thermal capacitance C degradation, which represents the dielectrics of a transformer such as oil. Here also it is seen that the transformer dielectric Cmaterials have decreased in its heat absorption capacity causing the winding temperature to rise so high up to 180˚C at 1500 sec irrespective of the high thermal resistance value L T C . Figure 8 graphically show the effect of thermal ca- pacitance degradation. T 5.2. Verification of Simulation The RLCTN was simulated with Multisim software in order to verify the results of the experiment performed in the power system laboratory using RLC electrical mod- ule and thermal imager. Comparing Figures 9-11 it is obvious that the lager the thermal capacitance slower the transient response time that is, the rate at which tem- perature rises is much slower and vice vase. With refer- ence to the model in Figure 2, the effect of RLC pa- rameters used are considered with three different values of thermal capacitance at constant thermal resistance and thermal inductance values: 49.8 J/˚C, 199.2 J/˚C, 348.6 J/˚C and 14 k˚C/W and 14 T for thermal capacitance of transformer components for instance winding, core, oil and radiator. For this simulation, there are set initial con- ditions namely, the winding temperature = 38˚C, the core surface temperature = 25˚C, the oil temperature = 15˚C and radiator temperature = 8˚C. These mentioned schemes shows the rate of temperature rise of an oil transformer that means the higher the thermal capacitance the slower the rate of temperature rise. In other words, the capacity of the oil and radiators to absorb heat emitted by the winding and core depends on the dielectric property such as volume, type of material, air space, and other proper- ties. In these scenarios, the time constant (i.e., the time it takes for the transformer winding to achieve its highest stable temperature) changes from 0 second to 10 seconds as shown in Figures 9-11, respectively, even though the final temperature is the same. Statistically, in consumer or industrial applications, a transformer temperature rise of about 40˚C to 50˚C may be acceptable, resulting in a maximum internal temperature of about 100˚C (trans- formers’ temperature rise limit). However, it may be wiser to increase the capacitance as well as the core size in other to obtain reduced temperature rise and reduced losses for better power supply efficiency. Figure 10. Thermal gradient with respect to time at C, C 199.2J14kWand14 CR L TT T. Figure 11. Thermal Gradient with respect to time at C, C 348.6J14kW and14 CR L TT T. Figure 12. IRT color gradient of 7 transformers depicting Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. 56 gradual degradation of dielectric materials . C T 5.3. Thermal Gradient An analytical IRT thermography is characterized with a thermogram showing visible spectrum image, as indi- cated in Figure 12. As stated in Section 3, thermal im- ages of pure inductive load were captured from real time operating transformers during validation process. This shows the effect of dielectric failure (thermal capacitance fault) on transformers. It was observed that as the ther- mal capacitance value is decreasing, the transformer temperature increase and vice vase. The color gradients of the IRT image in Figure 12 depict severity of dielec- tric abnormal condition that is thermal capacitance fault. This also shows how suitable dielectric materials can improve efficiency transformers by removing substantial amount of heat emitted by winding and core to the am- bient through the transformer radiators. 6. Conclusion In this paper, a mathematical model capable of describe- ing thermal characteristics of oil transformer was pre- sented. The model can adequately represent thermal cha- racterristics of each component in the transformer under load, steady state operation, and abnormality in the di- electric components such as the transformer oil, cellulose insulator, and other peripherals. This model is simple, accurate and easy to be applied for measuring the thermal impact on transformer. It provides an easy way of pre- dicting transformer’s thermal status. So, it allows me- chanisms like thermal throttling and load balancing to be more dynamic, rather than merely reacting to the situa- tion when the temperature reach a critical point. Fur- thermore, the algorithm is efficient enough to allow dy- namic recomputation of the transformer temperatures during operation. The captured thermal image brings the qualitative thermal image analysis of the model showing the thermal effect of gradual degradation of dielectric materials been represented as thermal capacitance TC in the RLCTN. Within the limits of experimental errors, it was observed that the RLCTN model effectively ana- lyzed the thermal degradation of transformer dielectrics with respect to time. Also the mathematical results repli- cate the simulation and experimental results, as it showed that thermal capacitance of dielectrics is inversely pro- portional to the transformer thermal rise. REFERENCES [1] D. Susa, M. Lehtonen and H. Nordman, “Dynamic Ther- mal Modeling of Distribution Transformers,” IEEE Trans- actions on Power Delivery, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2005, pp 1919-1929. http://www.ndted.org/EducationResources/CommunityCo llege/Other%20Methods/IRT/IR_Applications.htm [2] M. Matian, A. J. Marquis and N. P. Brandon, “Applica- tion of Thermal Imaging to Validate a Heat Transfer Model for Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 35, No. 22, 2010, pp 12308-12316. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.08.041 [3] Infraspection Institute, “Standard for Infrared Inspection of Electrical Systems & Rotating Equipment,” In: Infras- pection Institute, Infrared Training and Infrared Certifi- cation, Infraspection Institute, Burlington, 2008. [4] T. M. Lindquist, L. Bertling and R. Eriksson, “Estimation of Disconnectors Contact Condition for Modeling the Ef- fect of Maintenance and Ageing,” Power Tech IEEE Conference, St. Petersburg, 27-30 June 2005, pp. 1-7. [5] N. Rada, G. Triplett, S. Graham and S. Kovaleski, “High-Speed Thermal Analysis of High Power Diode Arrays,” Solid-State Electronics ISDRS, Vol. 52, No. 10, 2008, pp. 1602-1605. doi:10.1016/j.sse.2008.06.009 [6] Y. Cao, X. M. Gu and Q. Jin, “Infrared Technology in the Fault Diagnosis of Substation Equipment,” China Inter- national Conference on Electricity Distribution, Guang- zhou, 10-13 December 2008, pp. 1-6. [7] A. M. A. Haidar, G. O. Asiegbu, K. Hawari and F. A. F. Ibrahim, “Electrical Defect Detection in Thermal Image,” Advanced Materials Research, Vol. 433-440, 2012, pp 3366-3370. [8] Y. Cao, X. M. Gu and Qi Jin, “Infrared Technology in the Fault Diagnosis of Substation Equipment,” Technical Session 1 Distribution Network Equipment, Shanghai Electric Power Company Shanghai Branch Southern Power, 200030, SI-17 CP1377, CICED2008. [9] J. G. Smith, B Venkoba Rao, V. Diwanji and S. Kamat, “Fault Diagnosis—Solation of Malfunctions in Power Transformers,” Tata Consultancy Services Limited, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2009, pp. 1-12. [10] R. M. Button, “Soft-Fault Detection Technologies De- veloped for Electrical Power Systems,” 2005. http://powerweb.grc.nasa.gov/elecsys/ [11] Martin Technical Electrical Safety & Efficiency, “Infra- red Thermography Inspection,” 2012. http://www.martechnical.com/infrared_inspections/electri cal_infrared_inspection_service.php [12] G. Biswas, R. Kapadia, D. Xu and W. Yu, “Combined Qualitative—Quantitative Steady-State Diagnosis of Con- tinuous-Valued Systems,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics—Part A: Systems and Humans, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1997, pp. 167-185. doi:10.1109/3468.554680 [13] N. Radaa, G. Tripletta and S. Graham, “High-Speed Thermal Analysis of High Power Diode Arrays,” Solid- State Electronics ISDRS, College Park, 12-14 December 2007. [14] K. C. P. Wong, H. M. Ryan and J. Tindle, “Power System Fault Prediction Using Artificial Neural Networks,” In- ternational Conference on Neural Information Processing, Hong Kong, 24-27 September 1996, Article ID: 17762. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS  G. O. ASIEGBU ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. CS 57 [15] M. S. Jadin, S. Taib, S. Kabir and M. A. B. Yusof, “Im- age Processing Methods for Evaluating Infrared Thermo- graphic Image of Electrical Equipment,” Progress in Electromagnetics Research Symposium Proceedings, Marrakesh, 20-23 March 2011, p. 1299. [16] Electric Power Engineering Center “Guide to Power Transformer Specification Issues,” University of Canter- bury, 2007. http://www.scribd.com/doc/65031914/EPECentre-Guide- to-Transformer-Specification-Issues [17] K. Harwood, “Modeling a RLC Circuit’s Current with Differential Equations,” 2011. http://home2.fvcc.edu/~dhicketh/DiffEqns/Spring11proje cts/Kenny_Harwood/ACT7/KennyHarwoodFinalProject. pdf [18] A. P. Ferreira, D. Mossé and J. C. Oh, “Thermal Faults Modeling Using a RC Model with an Application to Web Farms,” 19th Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Sys- tems (ECRTS 07), Pisa, 4-6 July 2007, pp. 113-124. [19] M. Holt, “Understand the National Electricity Codes,” Cengage Learning, Delmar, 2002. [20] R. W. Hurst, “Electrical Safety and Arc Flash Hand- book,” Vol. 6, Electricity Forum, 2007. http://www.meisterintl.com/PDFs/Electrical-Safety-Arc-F lash-Handbook-Vol-5.pdf [21] T. Crnko and S. Dyrnes, “Arcing Flash/Blast Review with Safety Suggestions for Design and Maintenance,” Pro- ceeding of the IEEE conference on Industry Technical, Atlanta, 19-23 June 2000, pp. 118-126.

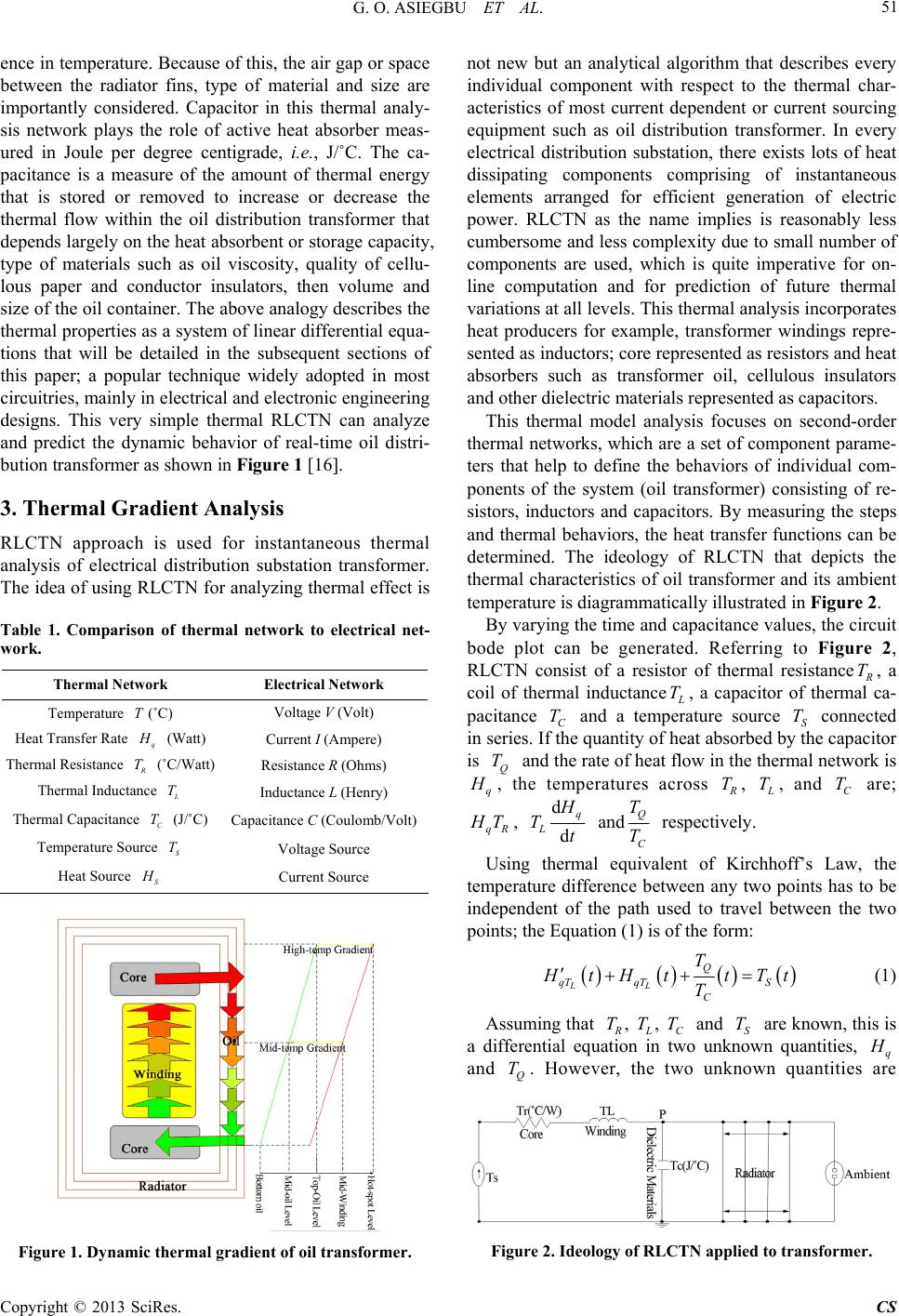

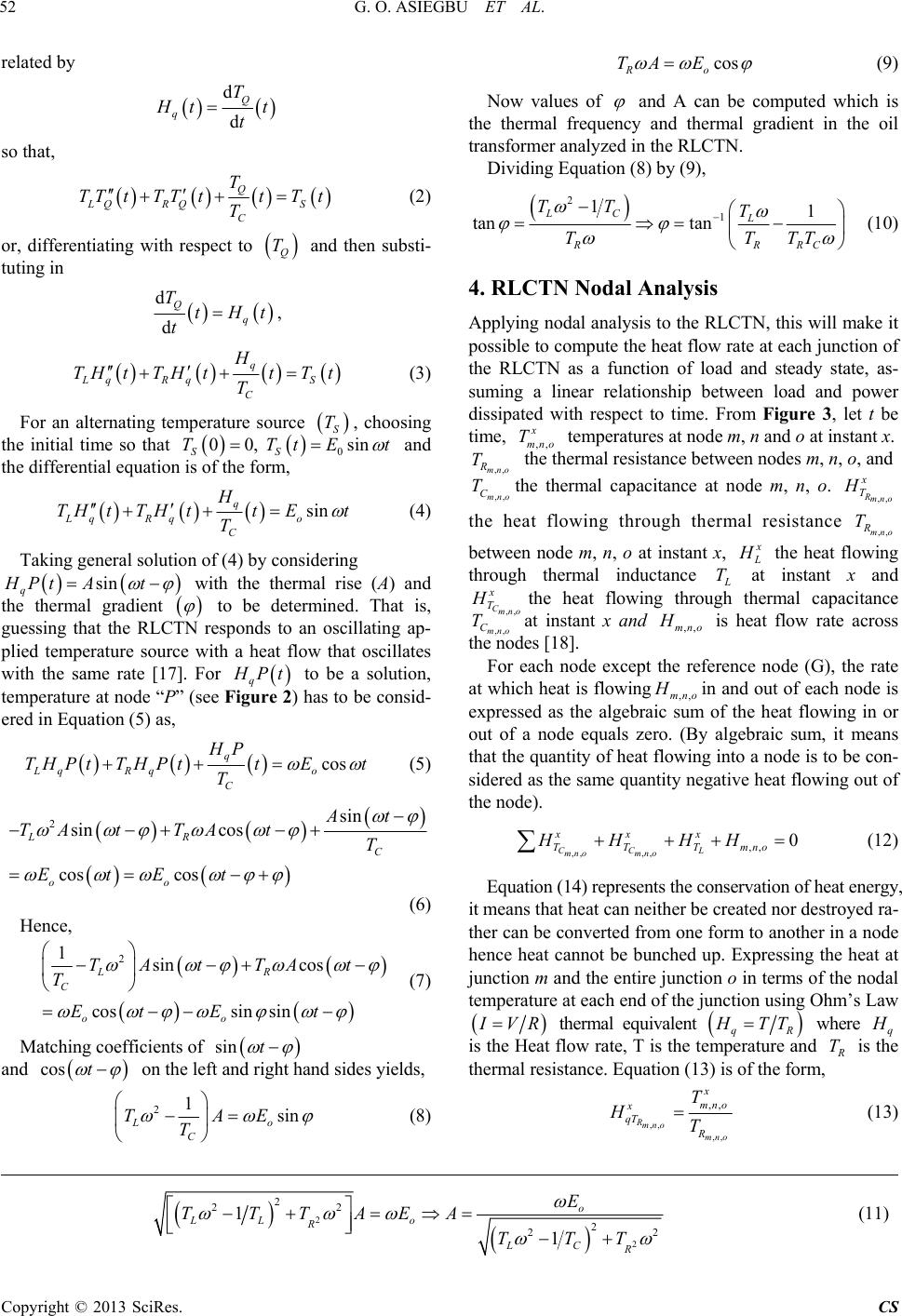

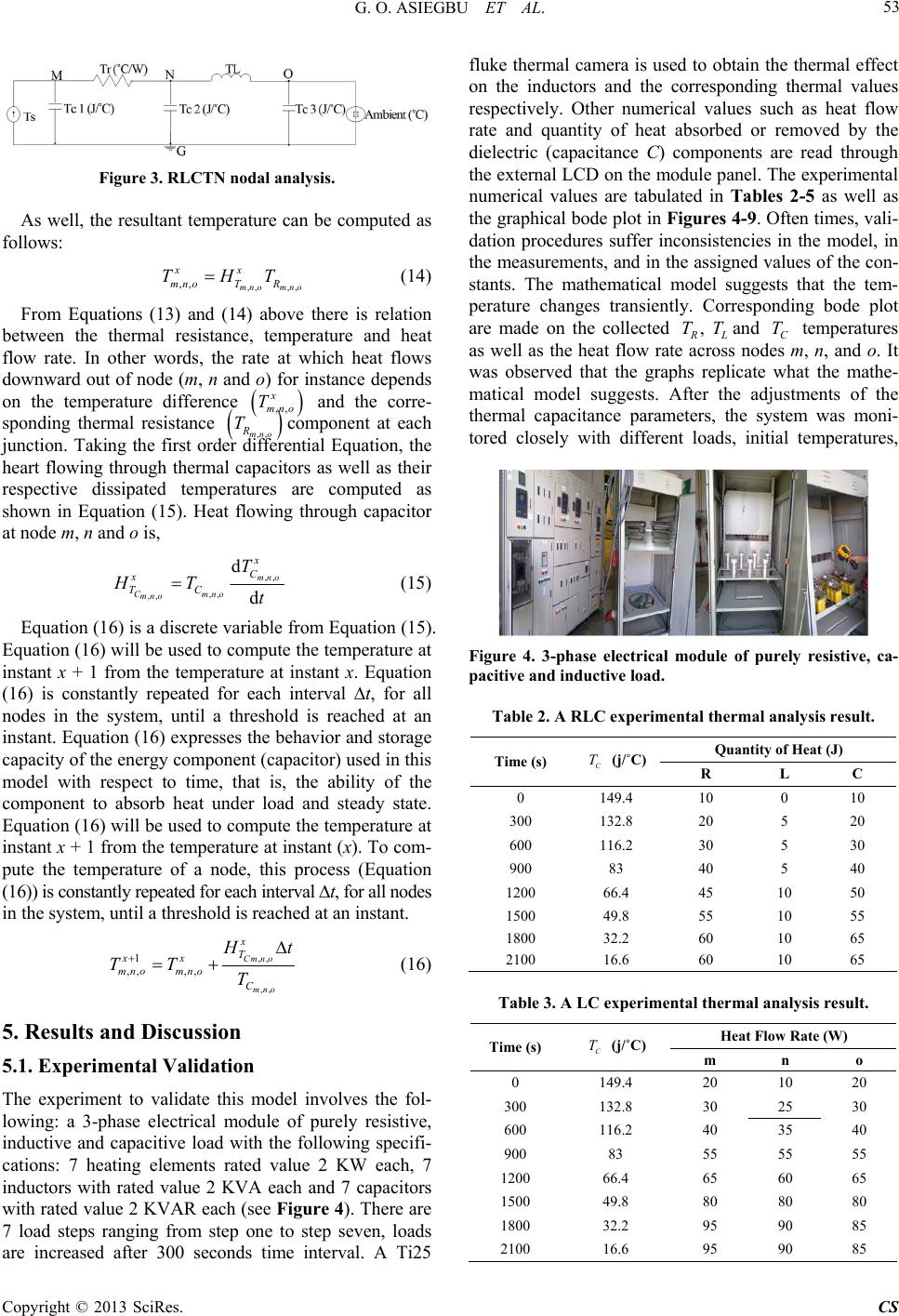

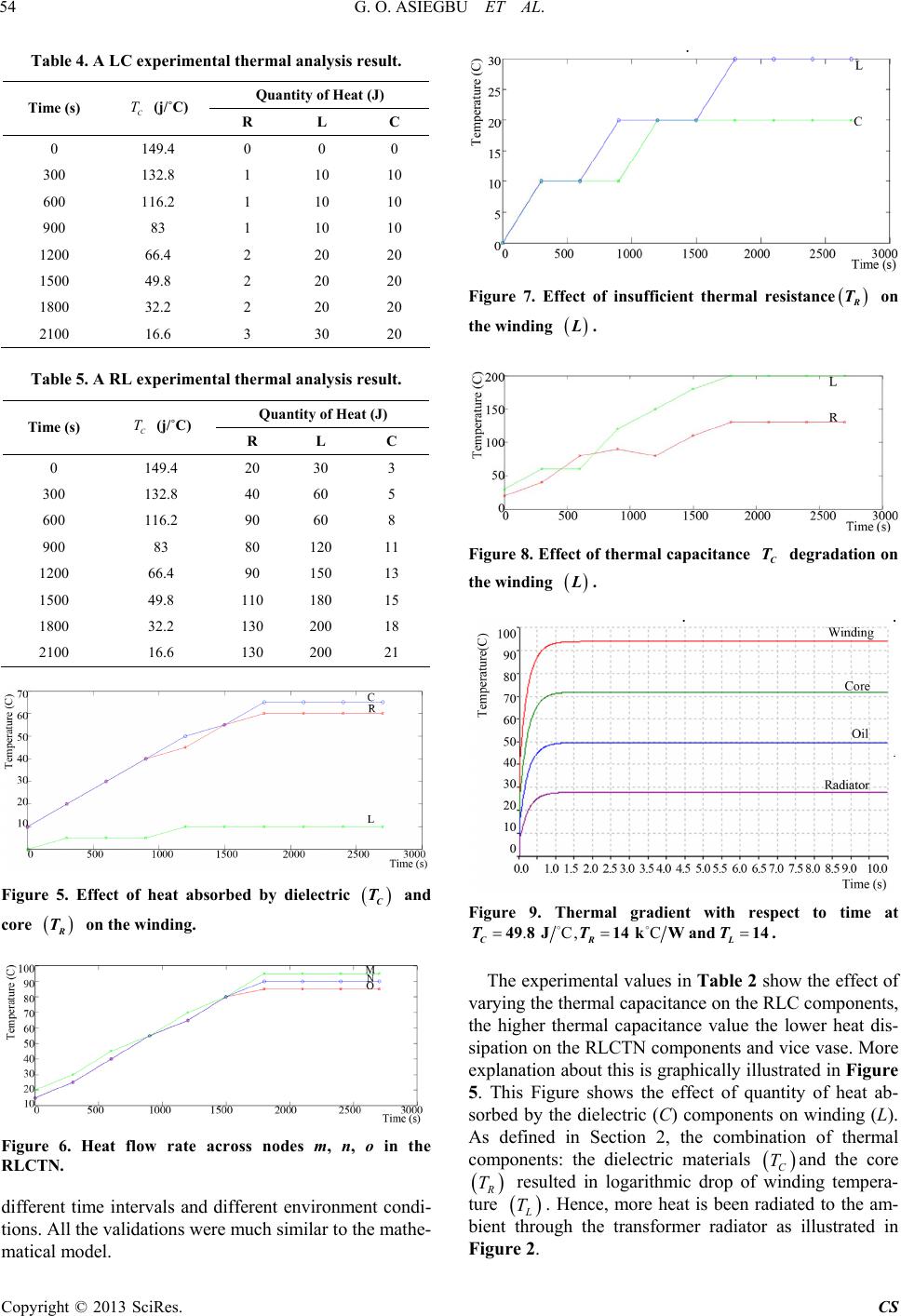

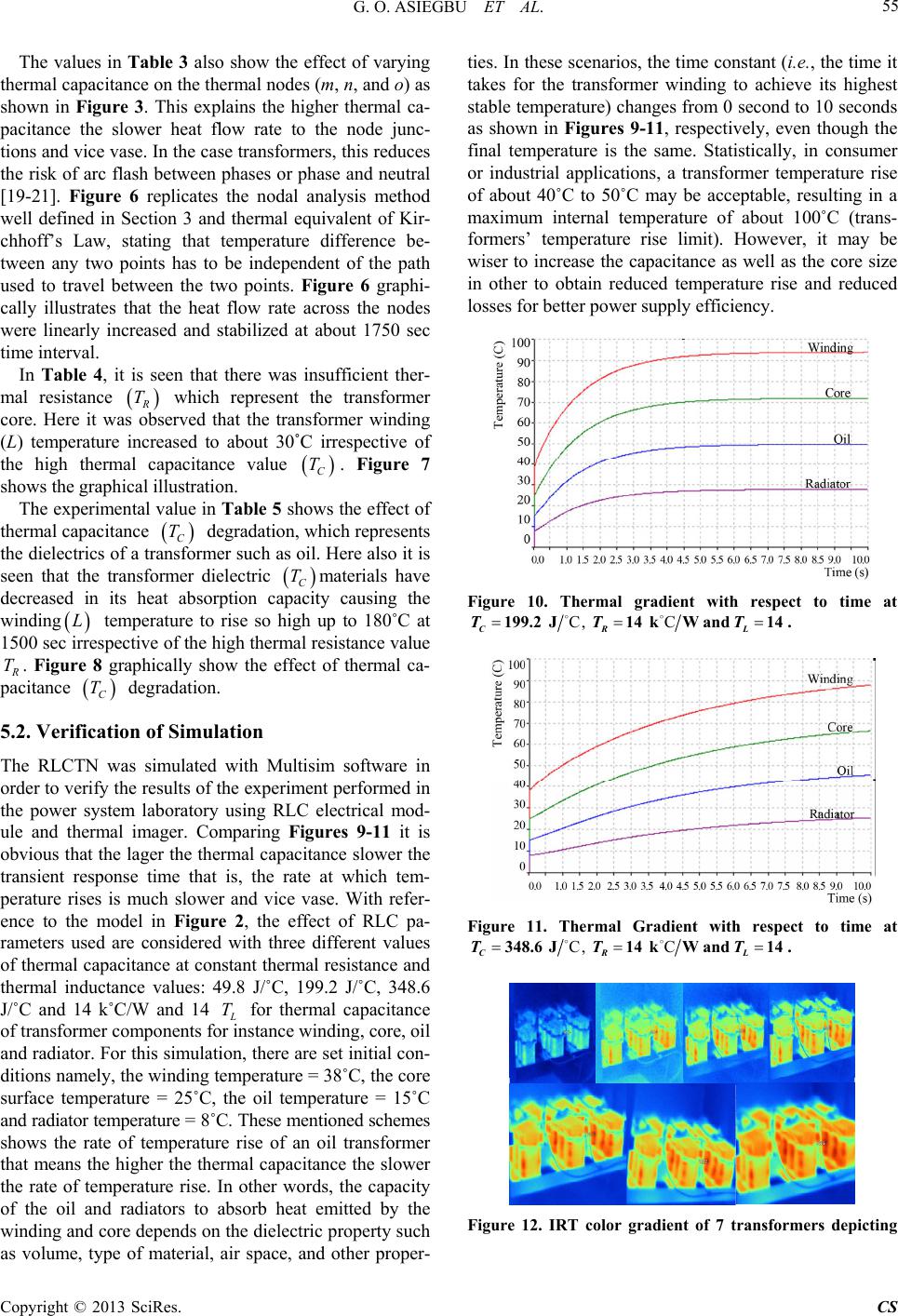

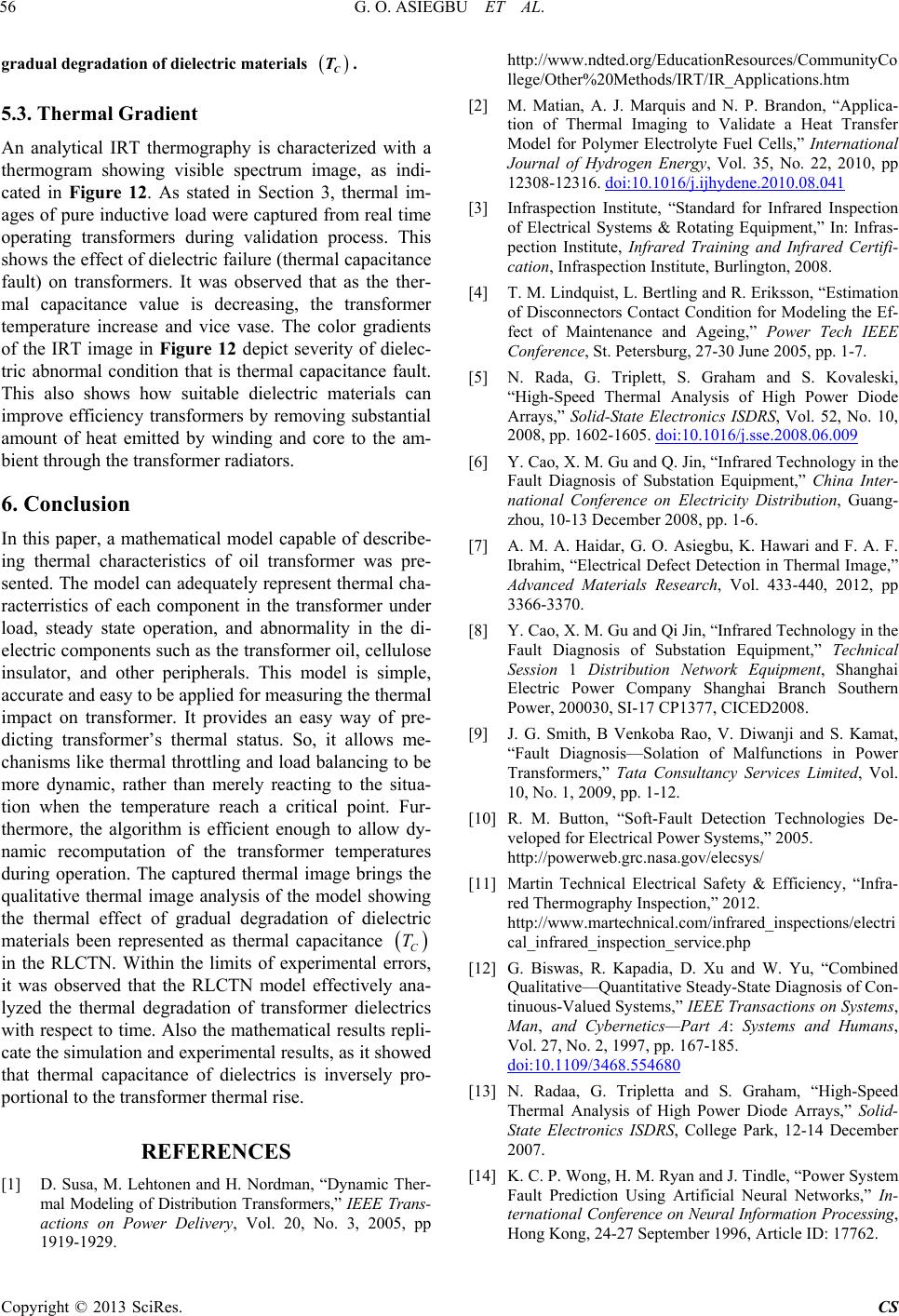

|