Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.1, 73-82 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.41010 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 73 Validity and Reliability of the Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory (STBI) Janne Pietarinen1*, Kirsi Pyhältö2, Tiina Soini3, Katariina Salmela-Aro4 1School of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland 2University of Helsinki Centre for Research and Development of Higher Education, Institute of Behavioural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 3School of Education, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland 4Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Email: *janne.pietarinen@uef.fi Received October 1st, 2012; revised November 7th, 2012; accepted December 7th, 2012 Recent research on teacher burnout has advanced our understanding of its dimensions and contributing factors. However, the complexity and dynamics of the social working environments in schools has often been neglected in teacher burnout studies, and hence a valid and reliable context-sensitive instrument for studying teacher burnout in terms of social interaction in schools is needed. This study examined the de- velopment of the Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory (STBI), its validity as well as reliability, among Finnish teachers (n = 2310). The validity and reliability of the items composing the STBI were determined based on the confirmatory factor analysis. The results showed that the correlated three-factor solution and second-order-factor solution fitted the data. More specifically, teacher exhaustion, cynicism towards the teacher community and inadequacy in the pupil-teacher relationship were found to be closely related but separate constructs. The results also supported the main hypothesis that teacher burnout can be examined in terms of interpersonal problems in an individual’s transactions with others in the workplace. Therefore the sources of teacher burnout may vary not only between schools but also between the social working contexts within a single school. The instrument introduced in this study is a potentially useful tool for exploring interpersonal teacher burnout. Keywords: Teacher Burnout Inventory; Occupational Well-Being; School; Social Working Contexts; Confirmatory Factor Analysis; Construct Validity Introduction Teacher burnout has been recognised as a serious occupa- tional problem (e.g. Borg & Riding, 1991; Loonstra, Browers, & Tomic, 2009; Kinnunen, Parkatti, & Rasku, 1994; Rudow, 1999). In comparison with other academic client-related pro- fessions, teachers have been found to surpass the average levels of stress (Travers & Cooper, 1993). In particular, they have been found to experience high levels of exhaustion and cyni- cism, both of which constitute the core dimensions of burnout (Kalimo & Hakanen, 2000; Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Re- cent research on teacher burnout has enhanced our understand- ing of its levels and dimensions and the factors that contribute to it (Dorman, 2003; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2009). However, the complexity and dynamics of the social working environments in schools has often been neglected in studies and measure- ments of burnout among teachers (Devos, Dupriez, & Paquay, 2012; Leiter & Maslach, 1988), and hence a valid and reliable context-sensitive instrument for examining teacher burnout in terms of social interactions within schools is needed. School as a complex working environment that includes multiple social contexts impose at least partly unique demands on teachers’ occupational well-being (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010; Pyhältö et al., 2011). This study reports on the development of an instru- ment for measuring teacher burnout within the social contexts of a teacher’s working environment. The developed instrument builds on one of the most commonly used Maslach and Jack- son’s (1981) burnout inventory. Teacher Burnout Burnout develops gradually as a consequence of prolonged and extensive work-related stress (Freudenberg, 1974; Holland, 1982; Peeters & Rutte, 2005). The syndrome has three distinct symptoms, exhaustion (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001), cynicism (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, 2008; Maslach & Leiter, 2005; Maslach & Leiter, 1999; Schaufeli & Buunk, 2003) and professional inadequacy (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Hakanen, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2006; meta-analysis by Mont- gomery & Rupp, 2005). Exhaustion means a lack of emotional energy, and feelings of being strained and tired at work (Maslach et al., 2001), whereas cynicism means indifference or aloofness towards work in gen- eral, and also a disaffected or acerbic attitude towards students, parents or colleagues, as well as low organisational commit- ment (Schaufeli & Buunk, 2003). Professional inadequacy, referring to feelings of insufficient competence, encompasses both social and non-social aspects of occupational accom- plishments (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Hakanen et al., 2006; meta-analysis by Montgomery & Rupp, 2005). Burnout as a social problem in many service professions has been the impe- tus for the much earlier research (Maslach, 2003). However, the *Corresponding author.  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. role played by social behaviour has been largely neglected, even though burnout was identified as a social problem by both workers and social commentators (Maslach, 2003) long before it became a focus of systematic empirical study. In fact, since the concept emerged, burnout has been presented not as an individual stress response, but rather in terms of interper- sonal problems in an individual’s transactions with others in the workplace, and theories of social comparison (Buunk, Ybema, Gibbons, & Ipenburg, 2001; Festinger, 1954) and so- cial exchange (Adams, 1965) provided an early framework (Buunk & Schaufeli, 1993; Geurts, Schaufeli, & De Jonge, 1998; Schaufeli, Van Dierendonck, & van Gorp, 1996), whereas more recent studies have focused on social support as a buffering resource (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007). Social interrelations are very frequent in the working envi- ronment of teachers within the school community. For example, during a school day teachers often work with different pupil groups and various members of the professional community. The destructive friction and other problems in the working environments of schools, such as lack of social support, per- ceived inequity and a poor sense of community (Santavirta, Solovieva, & Theorell, 2007; Milfont, Denny, Ameratunga, Robinson, & Merry, 2008; Sharplin, O’Neill, & Chapman, 2011) have been suggested to be central sources of exhaustion and stress for teachers. As well, unresolved confrontations, complex social interactions have been suggested to contribute to teachers feeling burdened (Cano-Garcia, Padilla-Munoz, & Carrasco-Ortiz, 2005; Dorman, 2003; Leung & Lee, 2006; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). This indicates that the sources of teacher burnout may vary not only between schools but also between the social working contexts within a single school (see also Kokkinos, 2007; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2009; Fernet, Guay, Senégal, & Austin, 2012). However, thus far the role of differ- ent social contexts in teacher burnout has been neglected in the research. The authors’ previous study on teacher burnout showed that it is situated primarily in social interactions within the school community. More specifically, the professional community and teacher-pupil interaction are the primary arenas of teacher burnout, particularly in terms of perceived inadequacy and cynicism (Pyhältö, Pietarinen, & Salmela-Aro, 2011). However, an inventory is lacking on teacher burnout in its social context. Hence, this study analyses the teacher burnout experience em- bedded in teacher-pupil and teacher-community interactions, and aims to develop such an inventory. Work Environment and Teacher Burnout Previous studies have shown that gender, school size and academic level have an influence on teacher burnout. Female teachers, for instance, have been found to have a higher risk for exhaustion in comparison to male colleagues (Tatar & Horenc- zyk, 2003; Antoniou, Polychroni, & Vlachakis, 2006; Fernet et al., 2012). Moreover, evidence shows that teachers who work in large school tend to receive less social support from the pro- fessional community compared to those working in smaller schools. School size has been reported to play a role in teacher burnout as manifested in decreased job satisfaction, lower ac- complishment and sense of depersonalization (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010). Further, some indicators show that the school level at which a teacher works, i.e. primary or secondary school, may also be associated with teacher exhaustion and lower job satisfaction (Jepson & Forrest, 2006). In this regard, pupil age is signifi- cant (Klassen, 2010; Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003; Wolters & Daugherty, 2007). Accordingly, the working environment at different school levels is likely to place at least partly unique demands on teacher groups, including class, subject and special education teachers, working at those particular levels (Byrne, 1993; Antoniou et al., 2006; Jepson & Forrest, 2006; Embich, 2007). The Present Study This study examined the development of the Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory (STBI), its validity as well as reli- ability, among class, subject and special education teachers in Finland. The aim was first to determine the construct validity of the developed instrument. In the light of previous research on teacher burnout (Byrne, 1993; Maslach & Leiter, 1999; Lau, Yuen, & Chan, 2005; Pyhältö et al., 2011) the structure of the STBI was tested by analysing the goodness-of-fit of the three-factor model of teacher burnout. It was expected that a model consisting of three correlated factors measuring exhaust- tion, cynicism towards the teacher community and sense of inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction would describe the phenomenon of teacher burnout embedded in key social con- texts of teachers’ work (Pyhältö et al., 2011; Salmela-Aro, Rantanen, Hyvönen, Tilleman, & Feldt, 2011). Moreover, a second-order-factor model existing behind the three-factor model was also expected. These two models were expected to describe the phenomenon of socio-contextual teacher burnout better than a one-factor model representing overall burnout. In addition, various aspects of reliability of the STBI, i.e. item reliability and scale reliability, were investigated. Finally, the socio-contextual sensitivity of the STBI was investigated by examining the observed differences in class, subject and special education teachers’ perceived exhaustion, cynicism towards the teacher community and sense of inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction. The first hypothesis was that teachers’ experienced exhaust- tion, cynicism towards the teacher community and inadequacy in the pupil-teacher relationship were closely related but sepa- rate constructs (e.g. Maslach & Leiter, 1999; Lee & Ashforth, 1996). Hence, the three-factor model (M1) was selected as a primary model (see Figure 1). Previous studies suggest that these socio-contextual components of teacher burnout should also indicate teachers’ overall risk for burnout (Byrne, 1993; Pyhältö et al., 2011; Salmela-Aro et al., 2011). For this reason, the second-order model (M2) was also expected to fit the data (hypothesis 2). Moreover, it was expected that gender, educa- tional background, school size and partly specified pedagogical tasks at different academic levels would influence teachers’ experienced exhaustion, cynicism towards the teacher commu- nity and inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction (hypothesis 3). Methods Participants Altogether 2310 Finnish comprehensive school teachers, in- cluding primary (n = 815; 35%), subject (n = 729; 32%), and special education teachers (n = 761; 33%) completed the survey. A probability sampling method (N = 6000) was used. The total Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 74  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 75 Figure 1. Three-factor (model M1), second-order (model M2) and one-factor (model 3) factorial structures of the Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory (STBI). EXH exhaustion, CYN cynicism towards professional community, INAD inadequacy in teacher-pupil in- teraction and OB overall socio-contextual burnout. Table 1. response rate was 39%. All respondents had MA degrees, and all were in various phases of their careers. Hence the response rates of class, subject, and special education teachers were not biased. Moreover, the schools in which the participants worked varied both in size and in terms of grades that were taught. The specified non-response analysis is presented in Table 1 . The non-response analysis. Sample statistics *National statistics n = 2310 teachers N = 36,890 teachers Gender Female 81% 73% Male 19% 27% Teachers’ age <40 years 38% 32% 40 - 49 years 30% 33% ≥50 years 32% 35% The analysis showed that the representativeness of the sam- ple was plausible (see Table 1). The mean age of the respon- dents was 45.3 years (SD = 9.84; Min/Max: 25/68 years). Hence in terms of age the sample was well-representative of the Finnish teacher population (see also National Board of Educa- tion, 2010). The majority of the respondents were women (n = 1878) and the minority men (n = 429). Accordingly, female teachers were slightly over-represented in the sample (see Ta- ble 1). Measures Note: *(National Board of Education, 2010). The Socio-contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory (STBI) was developed by the authors. It draws on both Maslach and Jack- son’s (1981) burnout scale and Elo, Leppänen and Jahkola’s (2003) single-item stress scale in terms of measuring teachers’ perceived exhaustion. The STBI was constructed by specifying the social contexts of experienced cynicism and inadequacy (Soini, Pyhältö, & Pietarinen, 2010; Pyhältö et al., 2011). The STBI included the 9 items that had the highest reliability scores and that best suited the social working environments within the school1. The inventory consists of nine items measuring three factors of socio-contextual teacher burnout: a) exhaustion (3 items), b) cynicism towards the teacher community (3 items), and c) inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction (3 items). All items were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) (excluding the stress item that was rated on a 10-point scale). The final ver- sion of the STBI items is shown in Table 2. Control Variables for Analysing the Finnish Teachers’ Soci o- Con textual Burnout Symptoms The teachers’ educational background was measured by asking participants to identify their professional qualifications, i.e. whether they had class teacher, subject teacher, class and subject teacher or special education teacher qualifications. In Finland, all comprehensive school teachers hold a Master’s degree either in educational sciences or some other domain such as mathematics or biology, with compulsory additional studies (35 credits) in educational science. Class teachers who typically work (primary school) in grades (0) 1-6 have an MA degree in educational science, with the main subject being ap- plied educational sciences or e ucational psychology, while 1Due to the preliminary reliability analyses two exhaustion items with insuf- ficient internal consistencies-one, cynicism towards the professional com- munity, and two, inadequacy in the teacher-pupil interaction-were excluded from the inventory. d  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. Table 2. The final version of the socio-contextual teacher burnout inventory (STBI) (translated from Finnish). Please choose the alternative that best describes your current situation at work. Completely disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Completely agree 7 1. I’m disappointed in our teacher community’s ways of handling our shared affairs. (CYN) 2. Dealing with problem situations considering my pupils often upsets me. (INAD) 3. I feel burnt out. (EXH) 4. I often feel like an outsider in my work community. (CYN) 5. The challenging pupils make me question my abilities as a teacher. (INAD) 6. With this work pace I don’t think I’ll make it to the retiring age. (EXH) 7. In spite of several efforts to develop the working habits of our teacher community they haven’t really changed. (CYN) 8. I often feel I have failed in my work with pupils. (INAD) 9. Stress means a situation in which a person feels tense, restless, nervous or anxious or is unable to sleep at night because his/her mind is troubled all the time. Do you feel this kind of work-related stress? (EXH)* Note: *For single stress item the scale is from one to ten: not at all 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 very much. subject teachers who typically teach grades 7-9 (secondary school) usually have an MA in some subject with an additional compulsory one year of study in educational science. Special education teachers who teach in both primary and secondary schools in grades (0) 1-9 have an MA in educational science, with the main subject being special education. The socio-contextual factors of the teacher’s working envi- ronments were measured with two items. The school size was identified by asking about the number of pupils in the school where the teacher currently worked. The classification of the school size item included five categories: less than 100 pupils, 101 - 300 pupils, 301 - 450 pupils, 451 - 600 pupils and over 600 pupils. The academic level was measured by identifying the grades that were taught in the school. Three academic levels were categorised for further analysis: primary school (grades 0- 1-6), secondary school (grades 7-9) and combined school (grades 0-1-9). Hence by using these control variables the socio-contextual value of the developed teacher burnout invent- tory was more specifically tested. Analytic Strategy In the first phase of analysis the structure and construct va- lidity of the STBI were determined. Three alternative theoretic- cal models were estimated separately (M1-M3). A three-factor model (M1) assumed that three correlated latent factors, namely exhaustion, cynicism towards the teacher community and in- adequacy in teacher-pupil interaction, underlie the STBI items. The M1 was extended to a second-order-factor model (M2) that assumed one overall latent factor behind the three latent factors identified in the M1 model. However, to have sufficient validity and reliability, the scale of the second-order latent factor meas- uring overall socio-contextual teacher burnout required rela- tively high correlations between first-order factors (Sal- mela-Aro et al., 2011). Finally, a one-factor model (M3) that assumed there is one latent factor behind all nine items was also tested. All three models (M1-M3) are data-equivalent and in- clude the same number of estimated parameters (e.g. Feldt, Leskinen, Kinnunen, & Ruoppila, 2003; Salmela-Aro et al., 2011). All theoretical models are presented in Figure 1. The validity and reliability of the items composing the STBI were determined based on the confirmatory factor analysis. The analyses were performed using an Mplus statistical package (version 6.1; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010) and a miss- ing-data method. This method uses all data that are available in order to estimate the model without inputting data. Because the socio-contextual teacher burnout sub-scales were skewed, the parameters of the models were estimated using an MLR proce- dure, which produces maximum likelihood estimates with standard errors and 2 test statistics that are robust to non-nor- mality (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Leskinen, & Nurmi, 2009). The goodness-of-fit of the esti- mated standardised model was evaluated by an Chi-Square test, the Comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewin Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardised Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (SRMR). A non-significant Chi-Square value, CFI and TLI values above .95, a RMSEA value below .06 and SRMR value below .08 indicated a good fit with the data (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010, Salmela-Aro et al., 2009). Finally, the model fit was estimated with a relative goodness-of-fit Normed Fit Index (NFI ≥ .95) that takes into account large sample sizes (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Item reliability was measured by estimating the reliability coefficients (i.e., the squared correlation between the item and the factor, see Bollen, 1989; Liukkonen & Leskinen, 1999). The structural validity of the items was measured by estimating the standardised validity coefficients (i.e., standardised factor loadings), which indicate direct structural relations between the factor and the item (Bollen, 1989; Salmela-Aro et al., 2011). The internal consistency of the inventory was examined by estimating the factor score scale reliabilities (squared correla- tions between the factor score scale and the latent factor) and Cronbach’s alphas. Finally, on the basis of the three-factor model the sum scores for each factor were constructed and analysed in terms of teacher gender, educational background, school size and academic level variables. The observed mean differences between the groups were measured by t-test and one-way analysis of variance. Results The main aim of the study was to determine the construct va- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 76  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. lidity of the developed STBI instrument. The means, variances and the correlations are presented in Table 3. The validity and reliability of the instrument were estimated with three exhaust- tion items, three cynicism items and three inadequacy items. As shown in Table 4, the three-factor primary model (M1) fits the data. The three latent factors were correlated as ex- pected [r (exhaustion with cynicism) = .45, p < .001: r (ex- haustion with inadequacy) = .61, p < .001 and r (cynicism with inadequacy) = .34, p < .001]. The goodness-of-fit criteria sug- gested that the nine items, three-factor model described the whole data, i.e. the model fit the class, subject and special edu- cation teachers’ groups (see also Byrne, 1993; Hakanen et al., 2006). The Normed Fit Index was exploiting to compensate for the sensitivity of the Chi-Square test to a large sample size. In addition, the NFI suggested that the model fit the data. The second-order factor model (M2) fit the data with identi- cal goodness-of-fit statistics compared with the M1 model. Although all models (M1-M3) were data-equivalent, the one- factor model (M3) did not sufficiently fit the data (see Table 4). The results confirmed that teachers’ sense of work-related ex- haustion was related to cynicism towards the teacher commu- nity and inadequacy in the pupil-teacher relationship. Moreover, teachers’ overall socio-contextual burnout could be measured with three latent factors and nine items. On the basis of the goodness-of-fit criteria, further reliability analyses were con- ducted for the three-factor (M1) and second-order factor models (M2). The item reliability, standardised validity coefficients (i.e. factor loadings) and internal consistency (i.e. Factor determina- cies and Cronbach’s alphas) values are shown in Table 5. The results confirmed that the items included in the final three- factor model (M1) were valid indicators for latent factors, as the factor loadings were ≥.60 and Cronbach’s alphas ≥.70 (Salmela-Aro et al., 2011). Moreover, the item reliability, stan- dardised validity coefficients and internal consistency were also sufficient for the second-order-factor model (M2), i.e. overall socio-contextual teacher burnout. The construct validity and reliability analyses confirmed that the three-factor model (M1) was the most acceptable construct for exploiting the developed instrument. The compact con- text-sensitive teacher burnout inventory seemed to adequately measure two essential social contexts in which the teachers’ work-related well-being is challenged. To analyse the socio- contextual sensitivity of the developed inventory, the relations to the teachers’ background information and work environment variables, i.e. teachers’ qualification, gender, school size and academic level, were analysed. Finally, teachers’ gender, educational background, school size and academic level were used as control variables for ana- lysing the context sensitivity of the STBI. As shown in Table 6, the STBI provides a potential instrument for analysing the socio-contextual sources of teacher burnout, not only between schools but also between the social working contexts within a single school (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010; Pyhältö et al., 2011). The results suggest that teachers’ perceived exhaustion was de-contextual rather than associated with the context-sensitive burnout indicator (see Table 6). In terms of perceived exhaust- tion, the differences between class, subject and special educa- tion teachers or between academic levels were not statistically significant. However, teachers working in large schools (over 600 pupils) were more likely to experience exhaustion than those working in small schools (less than 100 pupils). These results suggested that the structural characteristics of the school are also risk factors for experiencing socio-contextual teacher burnout symptoms. The STBI was especially developed for identifying the socio- contextual nature of teachers’ experienced cynicism and inade- quacy at work. The results show that class teachers experienced less cynicism towards the professional community than subject and special education teachers did. Moreover, teachers who worked in small school communities (less than 100 pupils) or primary schools (grades (0-1-6) did not experience cynicism towards professional communities to a similar extent as their colleagues working in bigger schools and in more diverse pro- fessional environments. Teachers’ sense of inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction differed between the teacher groups and academic levels (see Table 6). All teacher groups differed statistically significantly from each other. Subject teachers had the highest level of ex- perienced inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction. In turn, spe- cial education teachers reported the lowest levels of experi- enced inadequacy. Further investigation showed that secondary school teachers (grades 7-9) differed from both primary (gra- des 1-6) and combined school teachers (grades 1-9) in terms of experienced levels of inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction. School size was not found to be a significant factor in teachers’ perceived inadequacy concerning their work with pupils. Teachers overall risk for burnout in terms of gender, educa- tional background, school size and academic level was also analysed. The results showed that there were not statistically significant (p level ≤ .01) gender differences in teachers ex- perienced overall burnout. However, the differences between teacher groups remained. Subject teachers’ risk for overall burnout was statistically significantly (p level ≤ .01) higher than the class and special education teachers. Moreover, the differ- ences in experienced burnout symptoms in terms of school size and between academic levels increased (p level ≤ .01). Teach- ers working in small schools (less than 100 pupils) experienced less burnout symptoms than teachers operating in the medium size (301 - 450 pupils) or big schools (over 600 pupils). The academic level, i.e. working environment was also statistically significant determinant ((p level ≤ .01) for teachers experienced overall burnout symptoms. Teachers working in the secondary school experienced more overall burnout symptoms than teach- ers in other working environments. Discussion Limitations of the Study The construct validity of the developed Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory was found to be sufficient. How- ever, thus far the instrument has not been validated in other coun- tries, school systems or teachers’ work environments. Further- more, the data used in this study was cross-sectional. Therefore additional construct validation of the STBI is needed. This re- quires longitudinal research designs employed in different con- texts, educational systems and cultures (Elo et al., 2003; Sal- mela-Aro et al., 2011). Moreover, in further studies the concur- rent validity (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009) of the identified three- factor model should be tested with covariates other than the work environment variables used in this study (e.g. gender and educational background). For instance, the relation between indi- vidual teacher’s perceived strategies for regulating their well- being in different social contexts, (e.g. experienced self-efficacy Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 77  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 78 Table 3. Correlation matrix of socio-contextual teacher burnout inventory items, item means, and variances. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 1) EXH11 1.000 2) EXH12 .619 1.000 3) EXH13 .609 .658 1.000 4) CYN21 .237 .302 .129 1.000 5) CYN22 .253 .290 .147 .680 1.000 6) CYN23 .297 .275 .187 .468 .465 1.000 7) INAD31 .347 .343 .381 .164 .196 .213 1.000 8) INAD32 .322 .350 .281 .183 .195 .260 .537 1.000 9) INAD33 .377 .310 .444 .147 .170 .201 .477 .442 1.000 Means 4.69 2.28 3.00 3.22 3.36 2.34 3.46 2.10 2.90 Variances 6.06 2.52 4.07 3.18 2.87 2.67 3.37 1.56 2.43 Note: All the correlations were significant at p level < .001. Table 4. Goodness-of-fit criteria for the estimated models. Chi-Square df p RMSEA SRMR CFI TLI NFI M1: Three-factor model 156.37 24 .000 .05 .04 .98 .97 .97 M2: Second-order-factor model 156.37 24 .000 .05 .04 .98 .97 .97 M3: One-factor model 1903.17 27 .000 .17 .11 .67 .56 .67 Note: The modification indices (MI) were not used to improve the model fit. Table 5. Estimated item reliability, standardised validity coeffients, factor determinancies, and Cronbach’s alphas for the nine-item, three-factor, and corre- sponding second-order factor for the Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory. Indicators Second-order-factor model Three-factor model Overall burnout Exhaustion Cynicism Inadequacy 1) Exhaustion11 .58 (.76) - - - 2) Exhaustion12 .66 (.82) - - - 3) Exhaustion13 .65 (.80) - - - 4) Cynicism21 - .67 (.82) - - 5) Cynicism22 - .67 (.82) - - 6) Cynicism23 - .34 (.58) - - 7) Inadequacy31 - - .54 (.73) - 8) Inadequacy32 - - .52 (.72) - 9) Inadequacy33 - - .41 (.64) - EXHAUSTION - - - .81 (.90) CYNICISM - - - .25 (.50) INADEQUACY - - - .46 (.68) Factor determinacy .92 .91 .88 .86 Cronbach’s α .81 .77 .74 .82 Note: A count without parenthesis refers to the estimated item reliability of an indicator, and a count in parenthesis to standardised validity coeffients, that is, the factor loading of each indicator.  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. Table 6. Teacher gender, educational background, school size and academic level as control variables for analysing socio-contextual teacher burnout. Control variables Exhaustion Cynicism Inadequacy M SD p M SD p M SD p Gender (t-test) a) Female (n = 1878) 1.04 5.27 .01 8.91 4.25 ns 8.52 3.79 ns b) Male (n = 429) 9.26 5.18 - 8.89 4.19 - 8.07 3.69 - Educational background (one-way anova) a) Class teacher (n = 815) 9.72 5.18 ns 8.16 4.30 .00bc 8.53 3.76 .01bc b) Subject teacher (n = 729) 1.14 5.30 ns 9.30 4.04 .00a 9.09 3.85 .01ac c) Special education teacher (n = 761) 9.80 5.29 ns 9.39 4.27 .00a 7.73 3.58 .00ab School size (one-way anova) a) Less than 100 pupils (n = 273) 9.22 5.10 ns 7.58 4.43 .00bcde 8.16 3.80 ns b) 101 - 300 pupils (n = 836) 9.83 5.26 ns 8.82 4.26 ns 8.49 3.65 ns c) 301 - 450 pupils (n = 659) 1.07 5.18 ns 9.30 4.20 ns 8.65 3.88 ns d) 451 - 600 pupils (n = 289) 9.69 5.30 ns 9.15 4.12 ns 8.18 3.78 ns e) over 600 pupils (n = 206) 1.83 5.48 .01a 9.47 3.98 ns 8.54 3.86 ns Academic level (one-way anova) a) Primary school (0-1-6), (n = 1014) 9.72 5.14 ns 8.45 4.35 .00bc 8.33 3.65 .01b b) Secondary school (7-9), (n = 445) 1.24 540 ns 9.74 4.04 .01a 9.00 3.94 .01ac c) Combined school (0-1-9), (n = 638) 9.86 5.32 ns 9.09 4.20 .01a 8.24 3.83 .01b Notes: EXH (range 3 - 24), CYN and INAD (range 3 - 21) are sum variables constructed on the basis of the three-factor model. Mean differences were significant at p level ≤ .01. in receiving and giving social support) and teacher’s experi- enced socio-contextual burnout symptoms need to be re- searched more deeply (Soini et al., 2010; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010). The study’s response rate was moderate. However, the rep- resentativeness of the sample was plausible. Previous studies (Krosnick, 1999; Cook, Heath, & Thompson, 2000) have shown that the representativeness of samples is a much more important criterion for evaluating the validity of a study than the response rate, particularly if a probability sampling method is used. In this study the sample was not biased in terms of the teachers’ perceived socio-contextual burnout. More specifically, teachers who experienced high levels exhaustion, cynicism towards the teacher community and inadequacy in the teacher- pupil interaction also responded to the questionnaire. Conclusion The study aimed at developing a context-sensitive instrument to study teacher burnout by testing the validity and reliability of the Socio-Contextual Teacher Burnout Inventory with a sample of Finnish teachers. Moreover, the study took a social and in- terpersonal approach to teacher burnout (Masclach, 2003; Buunk & Schaufeli, 1993; Geurts et al., 1998; Schaufeli et al., 1996; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Our main hypothesis was that teacher burnout is situated primarily in social interactions within the school community (Pyhältö et al., 2011). Therefore the sources of teacher burnout may vary, and not only between schools but also between the social working contexts within a single school (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2009; Fernet et al., 2012). The results showed that the correlated three-factor solution and second-order-factor solution fitted the data. Hence the re- sults supported hypotheses 1 and 2 by showing that teachers’ experienced exhaustion, cynicism towards the teacher commu- nity and inadequacy in the pupil-teacher relationship were closely related but separate constructs. The findings indicate that these components are ingredients of teacher’s overall socio-contextual burnout. The findings are also in accordance with those of previous work-related teacher burnout studies (Byrne, 1993; Maslach & Leiter, 1999). Moreover, the results supported the main hypothesis that teacher burnout can be ex- amined in terms of interpersonal problems in an individual’s relations with others in the workplace (Buunk et al., 2001; Fer- net et al., 2012). This study focused on developing measures for exploring teacher burnout in terms of primary social working environ- ments i.e. teacher-pupil and professional community interact- tions within the school (Soini et al., 2010). In further studies the socio-contextual components of the teacher burnout invent- tory could be expanded to multiple social contexts which may Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 79  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. also play a role in teacher burnout including collaboration with parents or other stakeholders in the educational system (e.g. Pillay, Goddard, & Wilss, 2005; Milfont et al., 2008). More detailed research evidence concerning the significance and emphasis of different social contexts with respect to teacher exhaustion, cynicism and inadequacy is also needed (Pyhältö et al., 2011). In line with previous studies, the results showed that female teachers’ were more likely to experience exhaustion than their male colleagues (Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003; Antoniou et al., 2006). However, no gender differences were noted in terms of perceived inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction or cynicism towards the professional community. Further, class, subject and special education teachers’ experienced inadequacy in teacher- pupil interaction and cynicism towards the professional com- munity differed from each other. The academic level, moreover, at which teachers work was found to affect the perceived in- adequacy and cynicism. These results supported hypothesis 3 by indicating that partly specified pedagogical tasks and educa- tional expertise at different academic levels (i.e. class, subject and special education qualification) contribute to teacher burn- out in the social settings of a school. The developed inventory can be utilised in the field of school development and teacher learning research. Previous studies have suggested that perceived work-related well-being is a pre- condition for teachers’ learning and sense of agency in terms of educational innovations (Vermunt & Endedijk, 2011; Soini et al., 2010; Pyhältö, Pietarinen, & Soini, 2012). Hence the STBI could be used as a measure to explore the relationship between socio-contextual burnout and teachers’ learning. Moreover, for teacher communities the STBI provides a tool for identifying and analysing the significance of varying social contexts to teachers’ perceived work-related well-being (see Table 2). Finally, the complexity of gradually developing teacher burnout in multiple social contexts has not been studied exten- sively. The instrument introduced in this study has the potential to contribute to interpersonal teacher burnout research in the future (see also Fernet et al., 2012). Moreover, it seems that reducing socio-contextual burnout symptoms, i.e. teacher cyni- cism in terms of professional community and inadequacy in the teacher-pupil interaction, requires context-sensitive and adap- tive strategies adopted by teachers that enable not only the ac- cess to the resources of the community (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) but also have potential to contribute to further devel- opment of the environment. Acknowledgements This research is funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture and Academy of Finland (research project: 259489). REFERENCES Adams, J. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267-299). New York: Academic press. Antoniou, A.-S., Polychroni, F., & Vlachakis, A.-N. (2006). Gender and age differences in occupational stress and professional burnout between primary and high-school teachers in Greece. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 682-669. doi:10.1108/02683940610690213 Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2002). Validation of the maslach burnout inventory—General survey: An internet study. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 15, 245-260. doi:10.1080/1061580021000020716 Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psy- chology. Work & Stress, 22, 187-200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649 Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588 Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Borg, M. G., & Riding, R. J. (1991). Towards a model for the determi- nants of occupational stress among schoolteachers. European Jour- nal of Psychology of Education , 6, 355-373. doi:10.1007/BF03172771 Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 239-253. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8 Buunk, B., Ybema, J., Gibbons, F., & Ipenburg, M. (2001). The affec- tive consequences of social comparison as related to professional burnout and social comparison orientation. European Journal of So- cial Psychology, 31, 337-351. doi:10.1002/ejsp.41 Buunk, B. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1993). Professional burnout: A per- spective from social comparison theory. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Mareks (Eds.) Professional burnout: Recent devel- opments in theory and research (pp. 53-69). Washington DC: Taylor & Francis. Byrne, B. (1993). The Maslach burnout inventory: Testing for factorial validity and invariance across elementary, intermediate and secon- dary teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psy- chology, 66, 197-212. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1993.tb00532.x Cano-Garcia, F. J., Padilla-Muñoz, E. M., & Carrasc o-Ortiz, M. A. (2005). Personality and contextual variables in teacher burnout. Per- sonality and Individual Differences, 38, 929-940. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.018 Cook, C., Heath, F., & Thompson, R. L. (2000). A meta-analysis of response rates in web- or internet-based surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 6 0 , 821-836. doi:10.1177/00131640021970934 Devos, C., Dupriez, V., & Paquay, L. (2012). Does the social working environment predict beginning teachers’ self-efficacy and feelings of depression? Teaching and Teacher Educat ion, 28, 206-217. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.09.008 Dorman, J. P. (2003). Relationship between school and classroom en- vironment and teacher burnout: A LISREL analysis. Social Psychol- ogy of Education, 6, 107-127. doi:10.1023/A:1023296126723 Elo, A.-L., Leppänen, A., & Jahkola, A. (2003). Validity of a single- item measure of stress symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29, 444-451. doi:10.5271/sjweh.752 Embich, J. L. (2001). The relationship of secondary special education teachers’ roles and factors that lead to professional burnout. Teacher Education and Special E duc ation, 24, 58-69. doi:10.1177/088840640102400109 Feldt, T., Leskinen, E., Kinnunen, U., & Ruoppila, I. (2003). The sta- bility of sense of coherence: comparing two age groups over a 5-year follow-up study. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 1151- 1165. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00325-2 Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intra- individual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Educa- tion, 28, 514-525. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013 Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117-140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202 Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 159-165. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x Geurts, S., Schaufeli, W., & De Jonge, J. (1998). Burnout and intention to leave among mental health-care professionals: A social psycho- logical approach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17, 341-362. doi:10.1521/jscp.1998.17.3.341 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 80  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. Hakanen, J., Bakker, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2006). Burnout and engage- ment among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 495-513. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001 Holland, R. P. (1982). Special educator burnout. Educational Horizons, 60, 58-64. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in co- variance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alterna- tives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 Jepson, E., & Forrest, S. (2006). Individual contributory factors in teacher stress: The role of achievement striving and occupational commitment. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 183- 197. doi:10.1348/000709905X37299 Kalimo, R., & Hakanen, J. (2000). Työuupumus. In T. Kauppinen, P. Heikkilä, S. Lehtinen, K. Lindström, S. Näyhä, A. Seppälä, J. Toik- kanen, & A. Tossavainen (Eds.), Työ ja terveys Suomessa v.200. (pp. 119-126). Helsinki: Työterveyslaitos. Kinnunen, U., Parkatti, T., & Rasku, A. (1994). Occupational well- being among aging teachers in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 38, 315-332. doi:10.1080/0031383940380312 Klassen, R. M. (2010). Teacher stress: The mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. The Journal of Educational Research, 103, 342-350. doi:10.1080/00220670903383069 Kokkinos, C. M. (2007). Job stressors, personality and burnout in pri- mary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 229-243. doi:10.1348/000709905X90344 Krosnick, J. A. (1999). Survey research. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 537-567. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537 Lau, P. S. Y., Yuen, M. T., & Chan, R. M. C. (2005). Do demographic characteristics make a difference to burnout among Hong Kong sec- ondary school teachers? Social Indicators Research, 71, 491-516. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3602-7_17 Lee, R., & Ashforth, B. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 123-133. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123 Leiter, M., & Maslach, C. (1988). The impact of interpersonal environ- ment on burnout and organizational commitment. Journal of Organ- izational Behavior, 9, 297-308. doi:10.1002/job.4030090402 Leung, D. Y. P., & Lee, W. W. S. (2006). Predicting intention to quit among Chinese teachers: Differential predictability of the component of burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 19, 129-141. doi:10.1080/10615800600565476 Liukkonen, J., & Leskinen, E. (1999). The reliability and validity of scores from the children’s version of the perception of success ques- tionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59, 651-664. doi:10.1177/00131649921970080 Loonstra, B., Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2009). Feelings of existen- tial fulfillment and burnout among secondary school teachers. Teach- ing and Teacher Education, 25, 752-757. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.002 Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and inter- ventions. Current Di r e ctions in Psychological Science, 12, 189-192. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01258 Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journa l of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99-113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205 Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2005). Banishing burnout: Six strategies for improving your relationship with work. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass. Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W., & Leiter, P. (2001). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psy- chological Science, 12, 189-192. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01258 Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (1999). Teacher burnout: A research agenda. In R. Vandenberg & A. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and pre- venting teacher burnout (pp. 295-303). Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press. Milfont, T. L. Denny, S., Ameratunga, S., Robinson, E., & Merry, S. (2008). Burnout and wellbeing: Testing the Copenhagen burnout in- ventory in New Zealand teachers, Social Indicators Research, 89, 169-177. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9229-9 Montgomery, C., & Rupp, A. A. (2005). A meta-analysis for exploring the diverse causes and effects of stress in teachers. Canadian Journal of Education, 28, 458-486. doi:10.2307/4126479 Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2010). Mplus users guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. National Board of Education (2010). Opettajat Suomessa [Teachers in Finland]. URL (last checked 3 April 2012). http://www.oph.fi/julkaisut/2011/opettajat_suomessa_201. Peeters, M., & Rutte, C. G. (2005). Time management behavior as a moderator for the job demand-control. Interaction Journal of Occu- pational Health Psychology, 10, 64-75. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.1.64 Pillay, H., Goddard, R., & Wilss, L. (2005). Well-being, burnout and competence: Implications for teachers. Australian Journal of Tea- cher Education, 30, 22-33. Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2011). Teacher-working environment fit as a framework for burnout experienced by Finnish teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 1101-1111. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.05.006 Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2012). Do comprehensive school teachers perceive themselves as active agents in school re- forms? Journal of Educational Change, 13, 95-116. doi:10.1007/s10833-011-9171-0 Rudow, B. (1999). Stress and burnout in the teaching profession: Euro- pean studies, issues, and research perspectives. In R. Vanderbergue, & M. A. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A source book of international practice and research (pp. 38-58). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511527784.004 Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. (2009). School burnout inventory: Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25, 48-57. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.48 almela-Aro, K., Rantanen, J., Hyvönen, K., Tilleman, K., & Feldt, T. (2011). Bergen burnout inventory: Reliability and validity among Finnish and Estonian managers. International A tional and Environmental He al th , S rchives of Occupa- 84, 635-645. doi:10.1007/s00420-010-0594-3 antavirta, N., Solovieva, S., & Theorell, T. (2007). The association between job strain and emotional exhaustion in a cohort of 1028 Fin- nish teachers. British Journal of Educational P S sychology, 77, 213- 228. doi:10.1348/000709905X92045 chaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A mu study. Journal of Org S lti-sample anizational Behavior, 25, 293-437. doi:10.1002/job.248 chaufeli, W. B., & Buunk, B. P. (2003). Burnout: An overview of 25 years of research in theorizing. In M. J. Winnubst, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The handboo S k of work and health psychology (pp. 383-425). S study S odel. Work & Chichester: Wiley. chaufeli, W., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to and practice: A critical analy s i s. London: Taylor and Francis. chaufeli, W., van Dierendonck, D., & van Gorp, K. (1996). Burnout and reciprocity: Towards a dual-level social exhange m Stress, 10, 225-237. doi:10.1080/02678379608256802 harplin, E., O’Neill, M., & Chapman, A. (2011). Coping strategies for adaptation to new teacher appointments: Interve Teaching and Teacher Educatio S ntion for retention. n, 27, 136-146. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.010 kaalvikS nd job satisfaction. Teaching and Sd Teacher Education, , E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2009). Does school context matter? Relations with teacher burnout a Teacher Education, 25, 518-524. kaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and tea- cher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching an 26, 1059-1069. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.12.006 oini,T., Pyhältö, K., & Pietarinen, J. (2010). Pedagogical well-being— Reflecting learning and well-being in teache S rs’ work. Teaching and Tut among ion, 19, 397-408. teachers: Theory and practic e , 16, 765-782. atar, M., & Horenczyk, G. (2003). Diversity-related burno teachers. Teaching and Teacher E ducat doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(03)00024-6 ravers, C. J., & Cooper, C. L. (1993). Mental health, job satisfaction T Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 81  J. PIETARINEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 82 ers. Work and Stress, 7, 203- and occupational stress among UK teach 219. doi:10.1080/02678379308257062 ermunt, J. D., & Endedijk, M. D. (2011). Patterns in teacher learning in different phases of the professional Vdivid-career. Learning and In ual Differences, 21, 294-302. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.019 olters, C. A., & Daugherty, S. G. (2007). Goal structures and teach- ers’ sense of efficacy: Their relation and association to teaching ex- perience and academic level. Journal of Ed W ucational Psychology, 99, 181-193. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.181 anthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resource model. International Journal of St X s ress Management, 14, 121-141. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

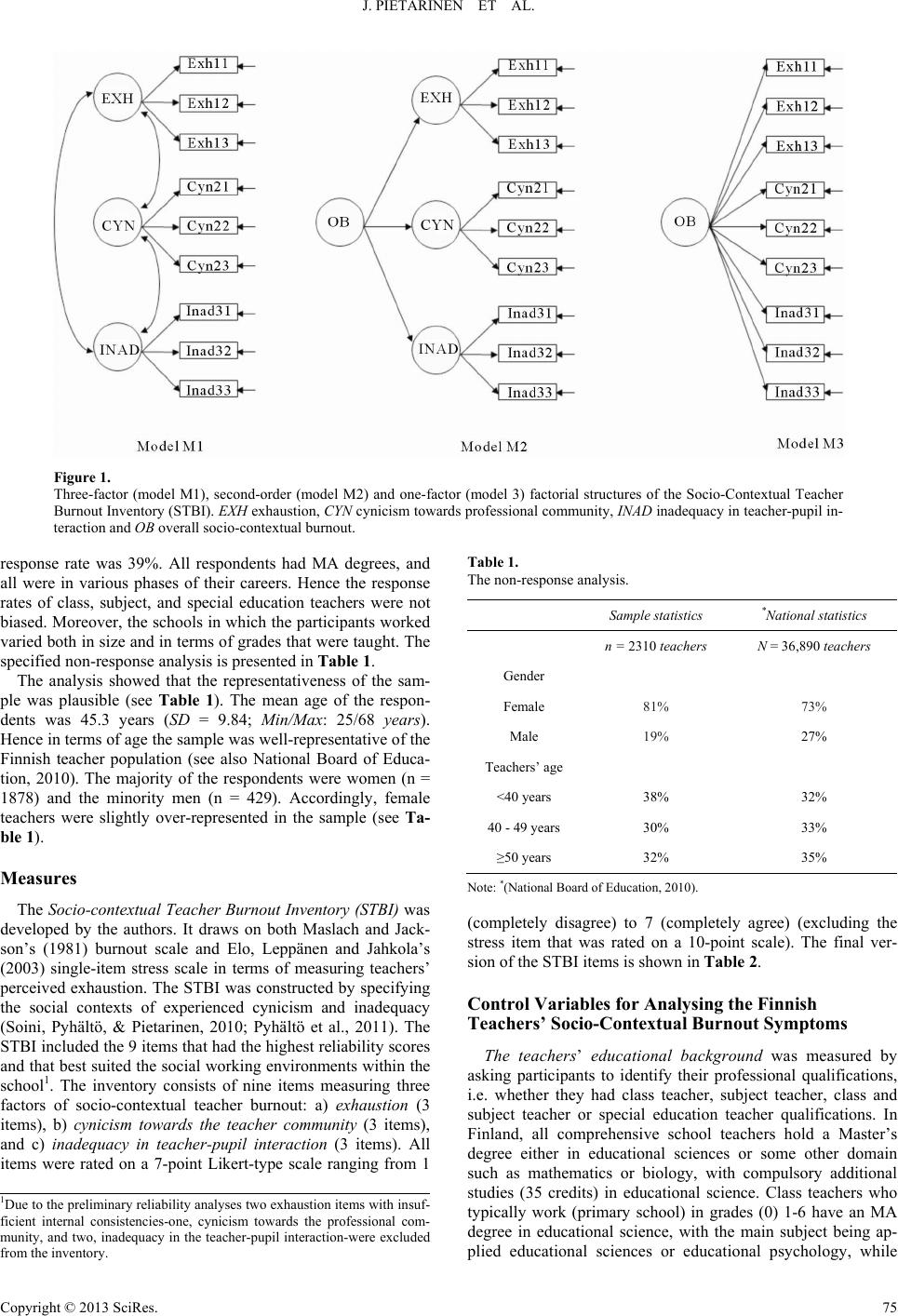

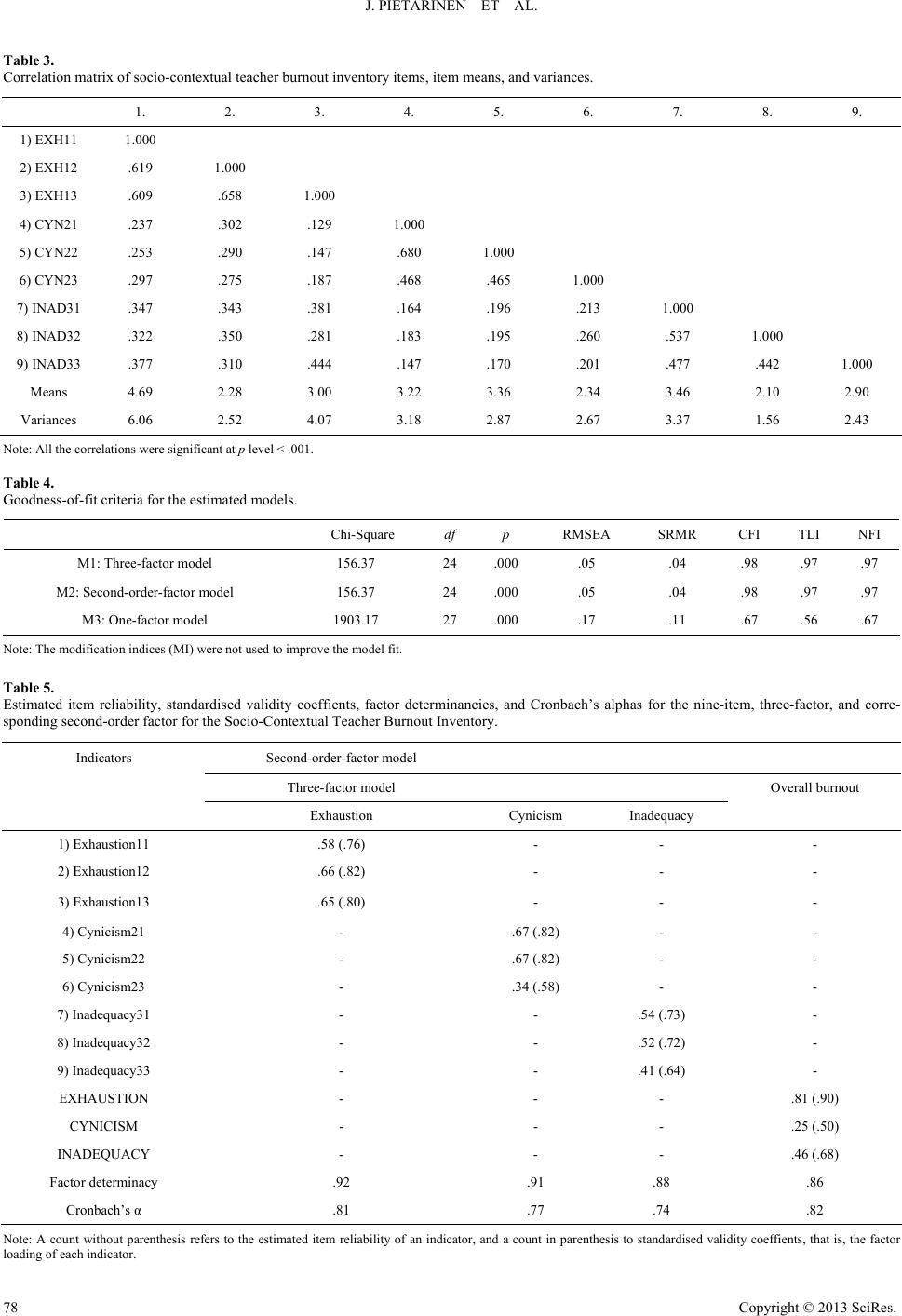

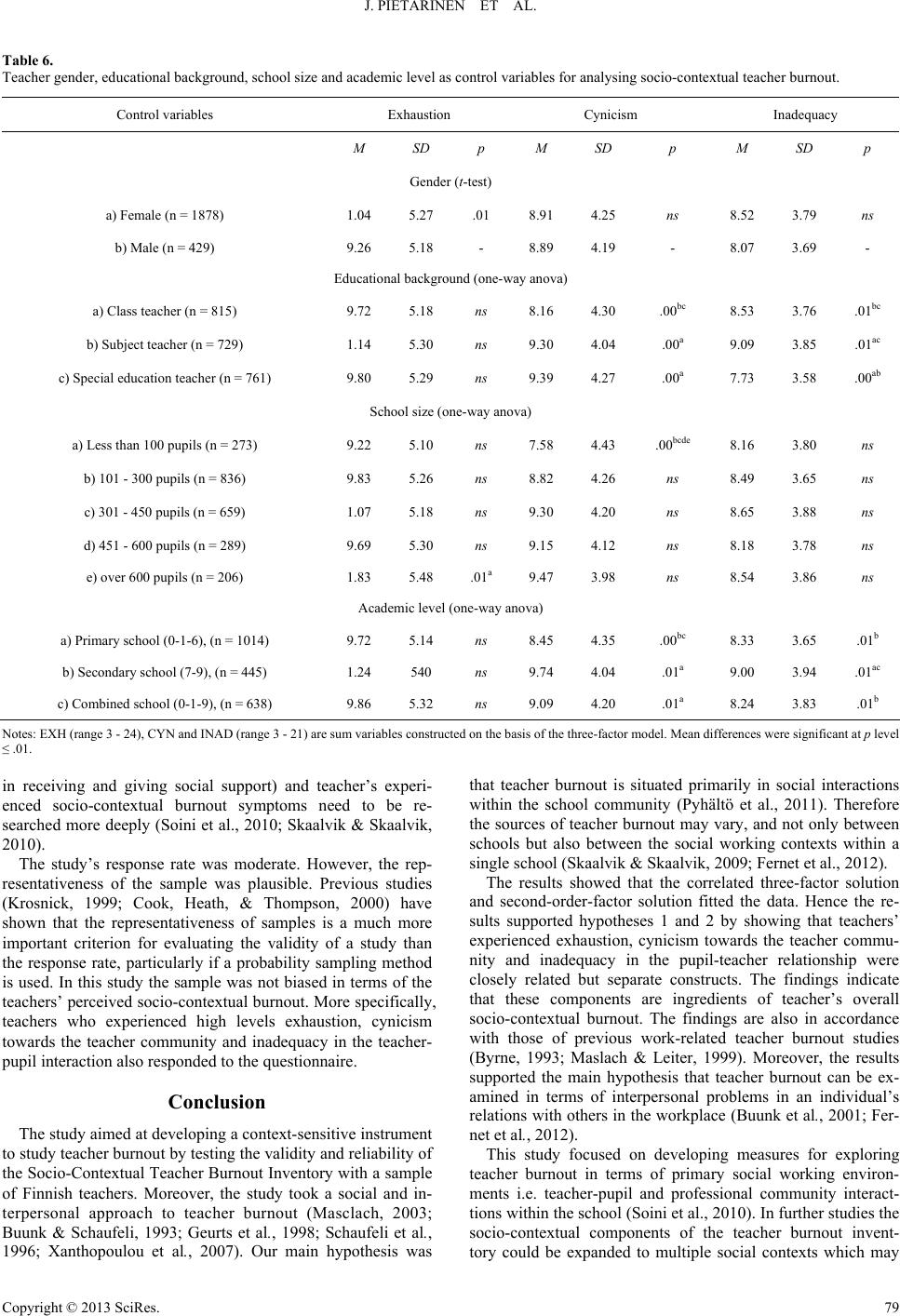

|