Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.1, 67-72 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.41009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67 Competitive Orientations and Women’s Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Bill Thornton1, Richard M. Ryckman2, Joel A. Gold2 1Department of Psychology, University of Southern Maine, Portland, USA 2Department of Psychology, University of Maine, Orono, USA Email: thornton@usm.maine.edu Received November 17th, 2012; revised December 15th, 2012; accepted January 5th, 2013 Women are presumed to compete intrasexually primarily on the basis of physical attractiveness. As such, in efforts to enhance their appearance, women may strive to achieve unrealistic cultural ideals of attrac- tiveness promulgated in the media with potentially negative implications (e.g., body dysmorphic disorder, eating disorders, and cosmetic surgery). The present study considered the implications of two forms of competitive orientation on women’s acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Findings indicated that a hypercom- petitive orientation (psychologically unhealthy) was a better predictor of acceptance of cosmetic surgery than body dysmorphia. Personal development competitiveness (psychologically healthy) was not related to either body dysmorphia or cosmetic surgery acceptance. Implication of these results and direction for further research are considered. Keywords: Appearance; Attractiveness; Body Image; Competitiveness; Cosmetic Surgery Introduction Physical attractiveness in general, and body satisfaction in particular, have long been identified as significant components of a woman’s self-concept and have important implications for interpersonal relations (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986; Franzoi & Shields, 1984). Women in Western societies are exposed to sociocultural norms for an ideal appearance from an early age and come to place an inordinate value on their physical ap- pearance as a means of achieving success in competition against other females for desirable mates. As Brownmiller (1984) observed, “How one looks is the chief weapon in fe- male-against-female competition. Appearance, not accomplish- ment, is the feminine demonstration of desirability and worth” (p. 50). Indeed, Darwin (1871) had observed that such intrasexual competition whereby women compete with other women through their appearance was a behavioral adaptation for at- tracting mates. Because males place high value on a woman’s physical attractiveness with regard to mate selection (Buss, 1989), women therefore would be expected to, and are reported to, compete intrasexually through self-promotion involving the enhancement of one’s physical characteristics or appearance (Fisher, 2004; Fisher & Cox, 2011). Considering “the politics of appearance,” a woman’s appearance may be her most im- portant commodity for social and economic survival within a culture (Chapkis, 1986; Rothblum, 1994; Seid, 1994; Wolf, 1991). The mass media (magazines, television, movies, and internet) are pervasive and continual purveyors of this not-so-implicit message for women to aspire to a cultural ideal of attractiveness and to be competitive through efforts that enhance their attrac- tiveness (Bessenoff, 2006; Derenne & Beresin, 2006). These ideals may become internalized and women may come to self-objectify and begin to critically evaluate themselves on the basis of these “appearance standards” (Franzoi, 1995; Fredrick- son & Roberts, 1997). Such pressures, both external and inter- nal, may create an onerous burden for women and further exac- erbate their feeling inadequate, anxious, and even depressed about their appearance and/or body when they do not measure up to these idealized cultural standards. As such, the emphasis on women’s appearance may not only contribute to the over- representation of women for body-image disorders and eating disorders (Derenne & Beresin, 2006; Striegel-Moore & Cache- lin, 1999; Veale, 2004), but also to increased acceptance and consideration of cosmetic surgery in order to enhance their self-esteem and improve their social and career potential (Cal- laghan, Lopez, Wong, Northcross, & Anderson, 2011; Calogero, Pina, Park, & Rahemtulla, 2010; Henderson-King & Brooks, 2009). The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS, 2011) re- ported recently that there were 19.3 million cosmetic and re- constructive surgery procedures performed annually in the United States. The majority of these were cosmetic surgeries (72%), elective procedures performed to improve appearance and self-esteem, and the majority of these were performed by women (91%); and there’s been a 90% increase in such en- hancements since 2000. The top five procedures were breast augmentation, facelifts, nose, liposuction, and tummy tucks. Reconstructive surgeries (28%), on the other hand, are per- formed for physical reasons to improve function and appear- ance due to congenital or developmental deformities, infection or disease, or trauma. While gender differences in these proce- dures were not reported on, it presumably was not as disparate as with elective cosmetic surgery. However, considering the implications of “competition” in this regard, Burckle, Ryckman, Gold, Thornton, and Audesse (1999) made an important point that not every form of competi- tive orientation may predispose women to have negative emo- tional reactions to one’s own body that result in feelings of  B. THORNTON ET AL. inadequacy, anxiety, and/or depression leading to disordered eating. Following Horney’s (1937) distinction between two competitive orientations, one that is psychologically unhealthy (i.e., hypercompetitiveness) and the other that is psychologi- cally healthy (i.e., personal development competitiveness), Burckle et al. observed that a hypercompetitive orientation was associated with disordered eating, whereas a personal develop- ment competitive orientation was not. The interest of the pre- sent study was to examine further the relationship these differ- ent competitive orientations have with body dysmorphia and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery for purposes of appearance enhancement among women. Hypercom p et itive Orientation According to Horney (1937), hypercompetitiveness is the neurotic need by individuals to be successful in various en- deavors and life areas “at all costs” and entails a willingness to manipulate and exploit other people in the pursuit of attaining a personal goal. She believed that such an extreme competitive attitude was an “unfailing center of neurosis” and highly detri- mental to the individual’s personality development and func- tioning. Horney proposed that this hypercompetitive orientation originated in childhood as a result of verbally and/or physically abusive relationships with authoritarian parents and was cou- pled with a strong parental emphasis on personal success in an achievement-oriented society such as ours. She maintained that children subjected to such abuse experienced feelings of pow- erlessness and insignificance which lead them to develop a need to win at all costs in order to feel more powerful and good about themselves. Also, by derogating, manipulating, and/or controlling others, hypercompetitive individuals are able to cope neurotically with their feelings of inadequacy and main- tain an otherwise fragile self-esteem. Research has indicated that hypercompetitive individuals are indeed highly neurotic and that these neurotic tendencies are based in anger and hostility toward others (Ross, Rausch, & Canada, 2003). In addition, they evidence other negative, un- healthy personality and social characteristics including low self-esteem, high anxiety, narcissism, dogmatism, a need to control and dominate, strategically manipulate self-impressions, and Machiavellianism (Dru, 2003; Ryckman, Hammer, Kaczor, & Gold, 1990; Ryckman, Libby, van den Borne, Gold, & Lindner, 1997; Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994; Ryckman, Thornton, Gold, & Burckle, 2002; Thornton, Lovley, Ryckman, & Gold, 2009; Watson, Morris, & Miller, 1998). Thus, it is not surprising that hypercompetitiveness has negative implications for romantic, family, and peer relationships (Ryckman, Thorn- ton, Gold, & Burckle, 2002; Thornton, Ryckman, & Gold, 2011a). Moreover, in relation to two components of the Type A behavior pattern that have differential implications for achieve- ment performance and health, hypercompetitiveness is not re- lated to Achievement Strivings or actual academic achievement, but was positively correlated with Impatience-Irritability, the “toxic factor” as far as increased risk for coronary heart disease is concerned, and greater self-reported health problems (Thorn- ton, Ryckman, & Gold, 2011b). Personal Development Co mpetitive Orientation In contrast to hypercompetitiveness, personal development competitiveness reflects an alternative healthy, positive com- petitive orientation (Ryckman & Hamel, 1992; Ryckman et al., 1996, 1997). Those characterized by this competitive orienta- tion are highly motivated to win and succeed; however, it would not be at any cost or at the expense of others. Indeed, these individuals compete with (rather than against) others in order to achieve their personal goals, and they focus less on the task outcome (i.e., win or lose) and more on the enjoyment inherent in the task itself (i.e., task mastery and the self-dis- covery, self-improvement, and personal growth gained through competition). As with hypercompetitiveness, Horney (1937) traced the origin of these healthy competitive strivings to early childhood experiences where children were afforded warm, supportive, yet authoritative (not authoritarian) treatment by their parents. Because their parents were responsive, trustwor- thy, and satisfied their need for basic security, she posited such children would be open to developing trusting and affectionate attitudes toward others. As such, they should be capable of healthy interpersonal relationships and be able to focus on the achievement of their competitive goals within a context of mu- tual respect and trust of others. Indeed, this personal development competitive orientation is associated with various indicators of psychological and social health. Research has shown it correlates positively with per- sonal and social self-esteem, achievement, affiliation, concern for the welfare of others, the ability to be altruistic in social relationships and the ability to forgive others for transgressions; and it is negatively correlated with neuroticism, dominance, and aggressiveness (Collier, Ryckman, Thornton, & Gold, 2010; Ryckman & Hamel, 1992; Ryckman, Hammer, Kaczor, & Gold, 1996; Ryckman, Libby, van den Borne, Gold, & Lindner, 1997). Individuals with this perspective are clearly motivated to exert maximum effort to win in competition, but in an honest and straightforward manner. They view other competitors as facili- tators who provide them with opportunities for self-discovery and personal growth and development (Burkle et al., 1999). And, with regard to the Type A behavior pattern, personal de- velopment competitiveness correlates positively with the Achi- evement Strivings component, as well as actual academic achi- evement; it does not correlate with Impatience-Irritability (the “toxic factor”), but is negatively associated with self-reported health problems (Thornton et al., 2011b). Competitive Orientation , B o dy Dys morphia, and Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Just as there are many negative personality and social impli- cations for individuals who have a hypercompetitive orientation, there are also many positive attributes and implications for those having the more psychologically healthy personal devel- opment competitive attitude. It is interesting to note that many of the negative personality attributes associated with hyper- competitiveness have been reported among women prone to disordered eating (Burckle et al., 1999) and vain, materialistic women who are favorably disposed toward cosmetic surgery (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005; Henderson-King & Brooks, 2009). Moreover, given the emphasis placed on appearance in competing against other women for the attention of men, women engaged in intrasexual competition utilize many of the same behaviors as hypercompetitive individuals, including self-promotion, demeaning and derograting a rival, bullying, and exclusion (Fisher & Cox, 2011). All things considered, hypercompetitive women may be pre- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68  B. THORNTON ET AL. disposed to work toward unrealistic standards of physical ap- pearance in order to overcome their feelings of inadequacy by achieving superiority over female rivals in physical appearance. As such, hypercompetitiveness was expected to be positively associated with greater body dysmorphia as well as greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery for enhancing one’s appearance. In contrast, those characterized by a personal development competitive orientation are not likely to see other females as rivals for male companionship who must be surpassed at all costs. Thus, personal development competitive attitudes would be unrelated, or perhaps negatively related, to body image dys- phoria and cosmetic surgery acceptance. Method Participants and Procedure Participants consisted of a nonclinical sample of 139 Cauca- sian female undergraduates at a public university in the north- eastern United States. Their mean age was 24.35 (SD = 7.98) and ages ranged from 18 to 58. In group sessions participants completed a set of questionnaires for the stated purpose of ob- taining baseline data for comparison purposes in subsequent research. In addition to assessments of competitive orientations, body-image, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery (described below), students provided height and weight with which to compute a body mass index (BMI; mean BMI was 24.64, and ranged from 17 to 42). Participation was voluntary and in ex- change for extra credit in their psychology course. Assessment Instruments Hypercompetitive Attitude (HCA). The 26-item HCA scale is a reliable and valid instrument that assesses individual dif- ferences in hypercompetitive attitudes (Ryckman et al., 1990; Ryckman et al., 1994). Sample items are “Winning in compete- tion makes me feel more powerful as a person,” and “If you don’t get the better of others, they will surely get the better of you.” Participants responded to items on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Scores can range from 26 to 130, with higher scores indicating a stronger hypercompetitive orientation. The internal consistency of this scale in the present study was adequate (α = .73). Personal Development Competitive Attitude (PDCA). This 15-item PDCA scale is a reliable and valid assessment of a psychologically healthy competitive orientation concerned more with personal growth and development than individual attainment (Ryckman et al., 1996; Ryckman et al., 1997). Sam- ple items are “I value competition because it helps me to be the best that I can be,” and “I enjoy competition because it brings me and my competitors closer together as human beings.” Indi- vidual items are responded to on a 5-point scale, strongly dis- agree (1) to strongly agree (5). Scores can range from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicative of a greater personal development competitive attitude. The internal consistency of this scale in the present study was adequate (α = .90). Situational Inventory of Body-Image Dysphoria (SIBID). The 20-item short form of the SIBID is a reliable and valid instru- ment that assesses individual differences in the extent to which people experience negative feelings about their bodies (Cash, 2002). Sample items are “I have negative emotional experi- ences when I look in the mirror,” and “I have negative emo- tional experiences when I am trying on new clothes at the store.” Items are responded to using a 5-point scale ranging from never (0) to almost always (4). Scores can range from 20 to 80, with higher scores reflecting greater body-image dyspho- ria. This scale had adequate internal consistency in the present study (α = .97). Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery (ACS). The ACS scale is a reliable and valid 15-item measure that assesses participants’ attitudes regarding acceptance of, and propensity for, cosmetic surgery (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005). Sample items are “I would consider having cosmetic surgery as a way to change my appearance so that I would feel better about my- self,” and “If I was offered cosmetic surgery for free, I would consider changing a part of my appearance that I do like.” Par- ticipants responded to the items on a 5-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (5). Scores can range from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicating greater acceptance of, and interest in having, cosmetic surgery. The internal consistency of the scale in the present study was adequate (α = .95). Social Self-Esteem. The Texas Social Behavior Inventory (TSBI; Helmreich & Stapp, 1974) is a reliable and valid 16- item assessment of an individual’s self-esteem as a function of one’s perceived level of social comfort and competence. Sam- ple items are “I feel secure in social situations,” and “I enjoy social gatherings with other people.” Item responses used a 5- point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (5) charac- teristic of me. Scores could range from 16 to 80 with higher scores indicative of greater social self-esteem. Internal consis- tency of this measure in the present study was adequate (α = .86). Social Desirability (SD) Assessment. Reynolds’ (1982) 13- item short-form of the Marlowe-Crowne SD scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1964) is a reliable and valid instrument that measures individual differences in approval seeking by endorsing state- ments that are socially desirable. Sample items are “I am al- ways willing to admit it when I make a mistake” and “I’m al- ways courteous, even to people who are disagreeable.” Indi- vidual items were responded to on a 5-point scale, ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). Total scores could range from 13 to 65, with higher scores indicative of a greater need for approval and the tendency to respond in a socially desirable manner. Internal consistency of the scale in present study was adequate (α = .77). Results Correlat ional Analyses Pearson correlation coefficients were computed among the different variables and are presented in Table 1. Social desir- ability response bias was apparent for individual difference assessments. As such, those with a greater predisposition to respond in a socially desirable manner were likely to report somewhat higher self-esteem (r = .35, p < .001) and more of a personal development competitive orientation (r = .17, p < .05), both of which are positive attributes. In contrast, those predis- posed to social desirability tended to under-report on negative attributes such as body dysmorphia (r = −.27), acceptance of/interest in cosmetic surgery (r = −.28), and hypercompeti- tiveness (r = −.42; all ps < .001. In consideration of the rela- tionships between the different individual difference variables, partial correlations controlling for social desirability response bias did not differ appreciably (in magnitude or significance) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 69  B. THORNTON ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 70 Table 1. Intercorrelations among study variables. SD AGE BMI TSBI SIBID ACSS HCA PDCA SD - .16 .07 .35c −.27c −.28c −.42c .17a AGE - .30c .30c −.16 −.01 −.32c .12 BMI - .05 .16 −.04 −.10 −.02 TSBI - −.46c −.07 −.16 −.34c SIBID - .24b .23b −.14 ACSS - .32c −.11 HCA - .08 Note: n = 139. ap < .05; bp < .01; cp < .001. from the zero-order correlations presented in Table 1. An interesting pattern of associations was apparent involving women’s age. While older women tended to have a greater BMI (r = .30, p < .001), they also had somewhat less situational body dysmorphia (r = −.16, p = .06) and higher social self- esteem (r = .30, p < .001). However, BMI and self-esteem were not related at all (r = .05), yet self-esteem negatively correlated with body dysmorphia (r = −.46, p < .001). These findings are rather anomalous given the concern women express about their appearance and weight across the life span (e.g., Pliner, Chaikin, & Flett, 1990) and that women’s self-esteem is highly related to body satisfaction (e.g., Franzoi & Shields, 1984). However, older women were also less hypercompetitive (r = −.32, p < .001) and may have less concern with intrasexual competition. Indeed, hypercompetitiveness was correlated positively with both body dysphoria (r = .23, p < .01) and acceptance of cos- metic surgery (r = .24, p < .01). This, perhaps, suggests that intrasexual competitional issues may be less of a concern for older women, yet remain an area of apprehension among younger women. Finally, age was essentially unrelated to per- sonal development competitiveness (r = .12), and personal de- velopment competitiveness was unrelated to body dysphoria (r = −.14) and acceptance of cosmetic surgery (r = .11) as conjec- tured earlier (ps > .05). Regression Analysis In further consideration of the distinction between the two competitive orientations and acceptance of cosmetic surgery, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with attitudes toward cosmetic surgery as the criterion. These results are pre- sented in Table 2. Initially, social desirability, age, BMI, and social self-esteem were entered as a block to control statistic- cally for individual differences on these variables (R2 = .08, p < .01), although social desirability was the only statistically significant contributor (t = −3.24, p < .01). This was followed by a stepwise consideration of body dysmorphia, hypercom- petitiveness, and personal development competitiveness. Hy- percompetitiveness was identified as the next best significant contributor to the prediction equation (R2 = .14, p < .001), and was then followed by the inclusion of body dysmorphia which also enhanced the regression (R2 = .18, p < .001). Personal de- velopment competitiveness did not contribute significantly to the regression and was excluded from entry. Discussion The results of the present study, both in correlations and re- gression, clearly indicate that the two competitive orientations are differentially related to acceptance of cosmetic surgery among women. As expected, hypercompetitiveness was posi- tively related to cosmetic surgery acceptance, whereas personal development competitiveness was unrelated in this regard. This distinction is consistent with that reported previously with re- gard to disordered eating (Burckle et al., 1999) and suggests that hypercompetitive women may be predisposed to compete intrasexually on the basis of appearance in ways that are poten- tially harmful to themselves in a quest to achieve unrealistic expectations regarding one’s appearance. The present results also indicated that women’s negative emotional feelings about their body image were more strongly accepting of cosmetic surgery to help improve their appearance and functioning. This is consistent with other research whereby cosmetic surgery is viewed as a means to enhance their self-esteem and improve their social and career potential (e.g., Callaghan et al., 2011; Calogero et al., 2010; Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005; Sarwer & Crerand, 2004). However, what is most interesting is that hypercompetitiveness was shown to be a better predictor of cosmetic surgery acceptance than body dysphoria. This suggests that the desire to compete against and triumph over other women (i.e., rivals) in the race for physical appearance superiority is paramount for them, and independent of whether they experience body dysphoria or not. While the findings of the present study have extended our knowledge of the areas in which hypercompetitive women play out their need to compete and “win at all costs” in an intrasex- ual arena against potential female rivals on the basis of physical attractiveness, the study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. In particular, the research was correlational in nature, not causal; and the sample here consisted of university women who were homogeneous in regard to race and social class. Thus, research among a variety of other populations of women is needed to increase our confidence in the generaliza- bility of the present findings. Given the maladaptive nature of hypercompetitiveness, one in- teresting question that emerges centers on the issue of identifying  B. THORNTON ET AL. Table 2. Regression analysis for acceptance of cosmetic surgery. VARIABLE β t R2 ΔR2 Step 1 .08b Age .05 .49 BMI −.03 −.37 SD −.29 −3.24b TSBI .02 0.22 Step 2 .14c .06 Age .13 1.37 BMI −.03 −0.41 SD −.17 −1.83 TSBI .00 0.01 HCA .29 3.12b Step 3 .18c .04 Age .14 1.50 BMI −.08 −0.96 SD −.15 −1.66 TSBI .09 0.94 HCA .26 2.81b SIBID .22 2.34a Note: Variable excluded at Step 3: PDCA, β =.12, t < 1.3, ns. ap < .05; bp < .01; cp < .001. the conditions under which individuals’ hypercompetitiveness can be reduced or eliminated. In the current study, the finding that hypercompetitiveness was negatively related to age suggests a potentially interesting avenue for future research. Allport (1961) surmised that many people free themselves of earlier selfish motives as they age and begin a movement toward psychologi- cal maturity, developing and refining personality characteristics that are antithetical to those characteristic of hypercompetitive- ness. Whereas hypercompetitive individuals are defensive in their relations to others and lack insight into themselves, they typically are unable to form healthy interpersonal relationships, treating family, friends, and others generally with mistrust, hostility, arrogance, criticism, and impatience. Allport’s mature people have more accurate, realistic perceptions of their abili- ties and limitations and are better able to deal effectively with life’s difficulties, relate to others, and have real concern for the welfare of others (see Ryckman, 2013). Future research could examine the relationships among competitive attitudes and various characteristics of psychological maturity as a function of age. Relatedly, examination of the social conditions that contribute to the development or reduction of maladaptive com- petitive attitudes would seem indicated as well. Moreover, given the present results speak of women, perhaps future research should consider similar implications of hyper- competitiveness for men. Although concerns with physical attracttiveness and body-appearance are more characteristic among women, there may be increased incidence in body-im- age disturbances, disordered eating (including supplement and steroid use), and utilizing cosmetic surgery for appearance and self-esteem enhancement among men associated, in part, with men become increasingly evaluated on the basis of their ap- pearance rather than their achievements with increased empha- sis in the various media on men’s appearance and methods for enhancing it (Derenne & Beresin, 2006; Hesse-Biber, 1996). As with women, men may not only feel less attractive and have reduced self-esteem following exposure to images of at- tractive males, but also have increased self-consciousness and heightened social-anxiety (Thornton & Moore, 1993). And, while women may report the experience more often than men, self-objectification, appearance and body-image concerns and self-evaluations, and consequent negative implications for self- esteem, body dysmorphia, and dietary abuse are evident among men as well (Cash, 2000; Moradi & Huang, 2008; Muth & Cash, 1997). As for implications for the consideration of cos- metic surgery for appearance and social/career enhancement, the proportion of men undergoing such elective procedures has increased 16% since 2000 (ASPS, 2011). It would appear that striving to achieve a societal ideal of male attractiveness may have similarly negative consequences for men as well. In this regard, further research might consider whether men’s competi- tive orientations, particularly hypercompetitiveness, have simi- lar associations with a predisposition to cosmetic surgery. In conclusion, with the societal/media emphasis on physical attractiveness for women, and the internalization of these cul- tural expectations, attractiveness remains a primary means of intrasexual competition among women in general. In particular, the present findings indicate that a hypercompetitive orientation may contribute further to women’s efforts to enhance their physical appearance in ways that may prove detrimental to themselves. Consideration as to how such a maladaptive orien- tation and consequent behaviors may be tempered or reduced certainly seems warranted. And, perhaps attention should be directed toward men to see whether similar relationships may be emerging for them as increased societal/media emphasis on a masculine appearance ideal intensifies. REFERENCES Allport, G. W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2011). Plastic surgery statistics report. URL (last checked 3 January 2013). http://www.plasticsurgery.org/News-and-Resources/2011-Statistics-. html Bessenoff, G. R. (2006). Can the media affect us? Social comparison, self-discrepancy, and the thin ideal. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 239-251. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00292.x Brownmiller, S. (1984). Femininity. New York: Simon & Schuster. Burckle, M. A., Ryckman, R. M., Gold, J. A., Thornton, B., & Audesse, R. J. (1999). Forms of competitive attitude and achievement orienta- tion in relation to disordered eating. Sex Roles, 40, 853-870. doi:10.1023/A:1018873005147 Callaghan, G. M., Lopez, A., Wong, L., Northcross, J., & Anderson, K. R. (2011). Predicting consideration of cosmetic surgery in a college population: A continuum of body image disturbance and the impor- tance of coping strategies. Body Image, 8, 267-274. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.002 Calogero, R. M., Pina, A., Park, L., & Rahemtulla, Z. (2010). The role of sexual objectification in college women’s cosmetic surgery atti- tudes. Sex Roles, 63, 32-41. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9759-5 Cash, T. F. (2000). Manuals for the appearance schemas inventory, body image ideals questionnaire, multi-dimensional body-self rela- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 71  B. THORNTON ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 72 tions questionnaire, and situational inventory of body-image dyspho- ria. URL (last checked 3 January 2013). http://www.body-images.com Cash, T. (2002). The situational inventory of body-image dysphoria: Psychometric evidence and development of a short form. Interna- tional Journal of Eating Disorde rs , 32, 362-366. doi:10.1002/eat.10100 Chapkis, W. (1986). Beauty secrets: Women and the politics of ap- pearance. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. Collier, S. A., Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., & Gold, J. A. (2010). Competitive personality attitudes and forgiveness of others. Journal of Psychology, 144, 535-543. doi:10.1080/00223980.2010.511305 Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirabil- ity independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychol- ogy, 24, 349-354. doi:10.1037/h0047358 Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray. doi:10.1037/12293-000 Derenne, J. L., & Beresin, E. V. (2006). Body image, media, and eating disorders. Academic Psychiatry, 30, 257-261. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.257 Dru, V. (2003). Relationships between an ego orientation scale and a hypercompetitive scale: Their correlates with dogmatism and au- thoritarianism factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 1509-1524. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00366-5 Fisher, M. (2004). Female intrasexual competition decreases female facial attractiveness. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 271, S283-S285. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0160 Fisher, M., & Cox, A. (2011). Four strategies used during intrasexual competition for mates. Personal Relationships, 18, 20-38. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01307.x Franzoi, S. (1995). The body-as-object versus the body-as-process: Gender differences and gender considerations. Sex Roles, 33, 417- 437. doi:10.1007/BF01954577 Franzoi, S., & Shields, S. A. (1984). The body esteem scale: Multidi- mensional structure and sex differences is a college population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 173-178. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4802_12 Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: To- ward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology o f Women Quarterly, 21, 173-206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x Hatfield, E., & Sprecher, S. (1986). Mirror, mirror... The importance of looks in everyday life. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Helmreich, R., & Stapp, J. (1974). Short forms of the Texas social behavior inventory (TSBI), an objective measure of self-esteem. Bulletin of the Psychonomi c Society, 4, 473-475. Henderson-King, D., & Henderson-King, E. (2005). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Scale development and validation. Body Image, 2, 137-149. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.003 Henderson-King, D., & Brooks, K. D. (2009). Materialism, sociocul- tural appearance messages, and parental attitudes predict college women’s attitudes about cosmetic surgery. Psychology of Women’s Quarterly, 33, 133-142. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01480.x Hesse-Biber, S. (1996). Am I thin enough yet? New York: Oxford Uni- versity Press. Horney, K. (1937). The neurotic personality of our time. New York: Norton. Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377-398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x Muth, J. L., & Cash, T. F. (1997). Body-image attitudes: What differ- ence does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 1438-1452. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01607.x Pliner, P., Chaikin, S., & Flett, G. L. (1990). Gender differences in concern with body weight and physical appearance over the life span. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 263-273. doi:10.1177/0146167290162007 Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28, 119-125. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<119::AID-JCLP2270380118> 3.0.CO;2-I Ross, S. R., Rausch, M. K., & Canada, K. E. (2003). Competition and cooperation in the five-factor model: Individual differences in achievement orientation. Journal of Psychology, 137, 323-337. doi:10.1080/00223980309600617 Rothblum, E. D. (1994). “I’ll die for the revolution but don’t ask me not to diet”: Feminism and the continuing stigmatization of obesity. In P. Fallon, M. A. Katzman, & S. C. Wooley (Eds.), Feminist perspec- tives on eating disorders (pp. 53-76). New York: Guilford Press. Ryckman, R. M. (2013). Theories of personality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. Ryckman, R. M., & Hamel, J. (1992). Female adolescents’ motives related to involvement in organized team sports. International Jour- nal of Sport Psychology, 23, 147-160. Ryckman, R. M., Hammer, M., Kaczor, L. M., & Gold, J. A. (1990). Construction of a hypercompetitive attitude scale. Journal of Per- sonality Assessment, 55, 620-629. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5503&4_19 Ryckman, R. M., Hammer, M., Kaczor, L. M., & Gold, J. A. (1996). Construction of a personal development competitive attitude scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 374-386. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6602_15 Ryckman, R. M., Libby, C. R., van den Borne, B., Gold, J. A., & Lind- ner, M. A. (1997). Values of hypercompetitive and personal devel- opment competitive individuals. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69, 271-283. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6902_2 Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., Gold, J. A., & Burckle, M. A. (2002). Romantic relationships of hypercompetive individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical P s ych olo gy , 21, 517-530. doi:10.1521/jscp.21.5.517.22619 Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., & Butler, J. C. (1994). Personality correlates of the hypercompetitive attitude scale: Validity tests of Horney’s theory of neurosis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62, 84-94. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6201_8 Sarwer, D. B., & Crerand, C. E. (2004). Body image and cosmetic medical treatments. Body Image, 1, 99-111. doi:10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00003-2 Seid, R. P. (1994). Too “close to the bone”: The historical context for women’s obsession with slenderness. In P. Fallon, M. A. Katzman, & S. C. Wooley (Eds.), Feminist perspectives on eating disorders (pp. 3-16). New York: Guilford Press. Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Cachelin, F. M. (1999). Bod image concerns and disordered eating in adolescent girls: Risk and protective factors. In N. G. Johnson, M. C. Roberts, & J. Worell (Eds.), Beyond ap- pearance: A new look at adolescent girls (pp. 85-108). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10325-003 Thornton, B., Lovley, A., Ryckman, R. M., & Gold, J. A. (2009). Play- ing dumb and knowing it all: Competitive orientation and impression management strategies. Individual Differences Research, 7, 265-271. Thornton, B., & Moore, S. (1993). Physical attractiveness contrast effect: Implications for self-esteem and evaluations of the social self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 474-480. doi:10.1177/0146167293194012 Thornton, B., Ryckman, R. M., & Gold, J. A. (2011a). Hypercompeti- tiveness and relationships: Further implications for romantic, family, and peer relationships. Psychology: Individual Development, 2, 269- 274. Thornton, B., Ryckman, R. M., & Gold, J. A. (2011b). Competitive orientations and the type A behavior pattern. Psychology: Individual Development, 2, 411-415. Veale, D. (2004). Advances in a cognitive behavioral model of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 1, 113-125. doi:10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00009-3 Watson, P. J., Morris, R. J., & Miller, L. (1998). Narcissism and the self as continuum: Correlations with assertiveeness and hypercom- petitiveness. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 17, 249-259. doi:10.2190/29JH-9GDF-HC4A-02WE Wolf, N. (1991). The beauty myth: How images of beauty are used against women. NY: William Morrow and Company.

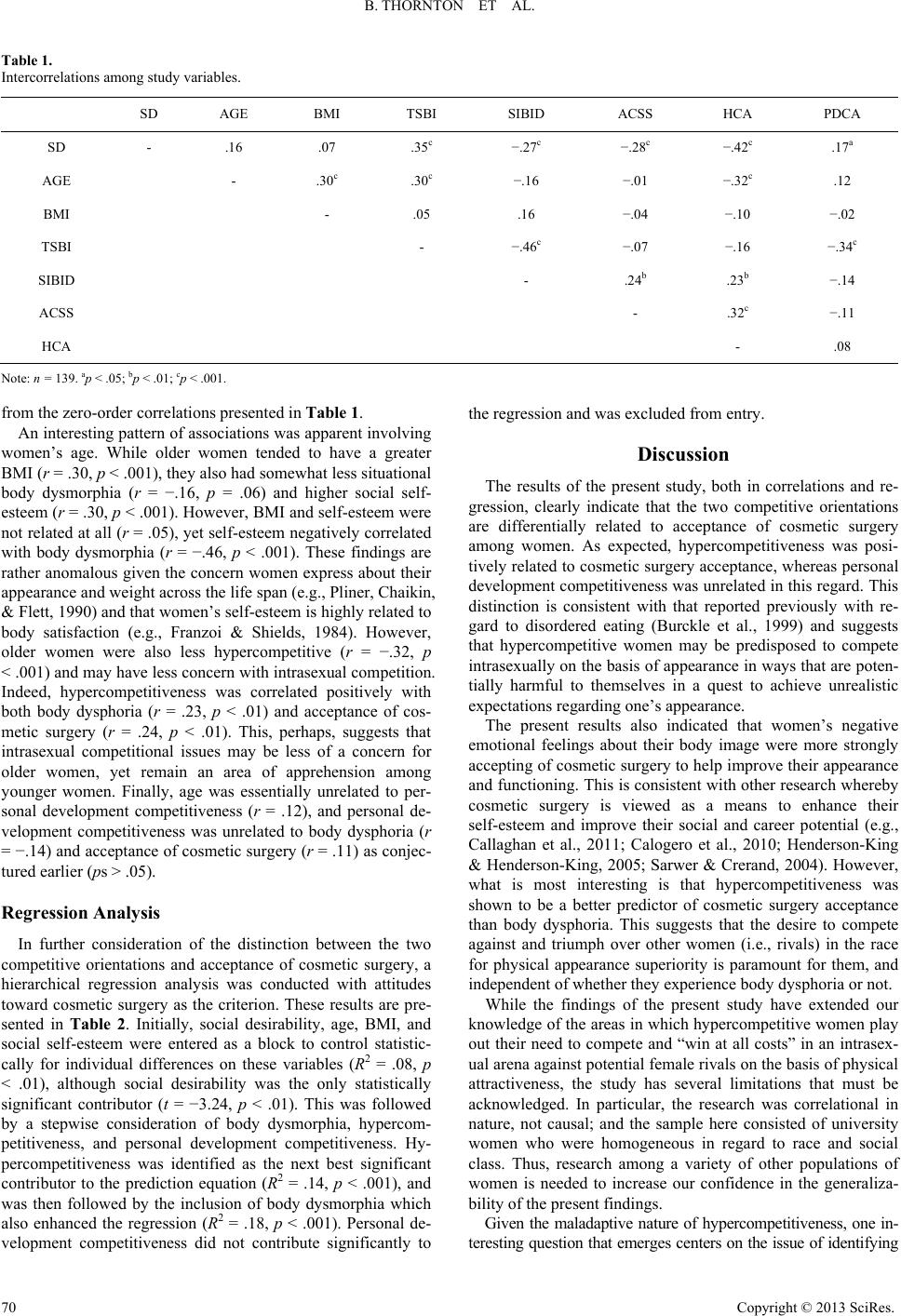

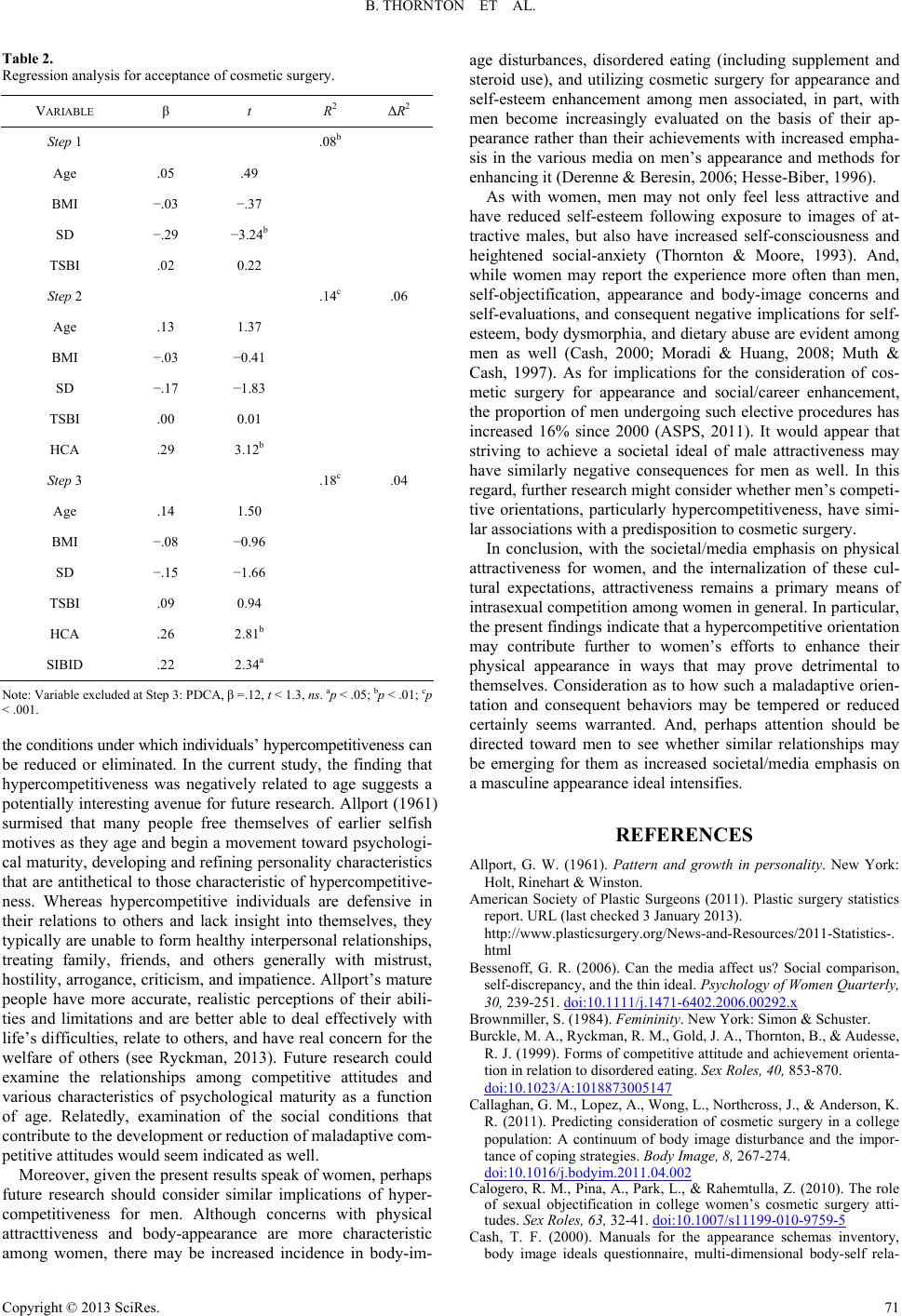

|