Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.1, 50-58 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.41007 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 50 Adolescent Adjustment: The Hazards of Conflict Avoidance and the Benefits of Conflict Resolution Megan E. Ubinger1, Paul J. Handal2, Carrie E. Massura2 1Department of Psychology, SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center, St. Louis, USA 2Department of Psychology, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, USA Email: mubinger@gmail.com Received October 16th, 2012; revised November 12th, 2012; accepted December 17th, 2012 Current literature provides strong support for the relationship between perceived family conflict (i.e., dis- agreements, expressed anger, and/or aggression) and adolescent maladjustment (i.e., internalizing, exter- nalizing, and/or physiological symptoms). Moreover, research indicates that successful conflict resolution (i.e., “behaviors that regulate, reduce, or terminate conflicts,” Davies & Cummings, 1994) decreases the adverse impact family conflict has on children. Many researchers have treated conflict resolution as a di- chotomous variable (e.g., resolved or unresolved), but there may be different approaches to conflict reso- lution. Only one dimensional measure of conflict resolution has been developed in the literature, and it has only been used in a sample of young adults. Recent research has also underscored the importance of assessing conflict avoidance (i.e., indirect efforts to alter stressful situations). Unfortunately, there are limited studies on conflict avoidance and its impact on psychological adjustment, none of which use an adolescent sample. The primary purpose of the current study was to determine whether the relationship between conflict resolution, conflict avoidance, and adjustment would extend to adolescents using a di- mensional measure of conflict resolution. Second, the current study aimed to develop and pilot a dimen- sional measure of conflict avoidance. One hundred two adolescents between the ages of 14 and 19 were recruited from four parochial high schools in a large Midwestern city. The participants completed self-report measures regarding perceived family conflict, conflict resolution, avoidant behaviors, and psychological adjustment. Results paralleled the findings of previous research in a young adult sample regarding the impact of conflict resolution on adjustment. In addition, after considering perceived family conflict, the presence of conflict avoidance added significantly to the prediction of adolescents’ psycho- logical symptoms. These findings suggest that assessing for conflict avoidance in addition to family con- flict and conflict resolution may have important implications for the screening and assessment of adoles- cent psychological health. Keywords: Family Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Avoidance; Adolescent Adjustment; Assessment Introduction During the last two decades the relationship between conflict and adjustment has been extensively investigated and research has revealed a clear relationship between these two variables. Initially, results of research concerning inter-parental conflict indicated a negative effect on the adjustment of children when inter-parental conflict was present. This finding has been sup- ported in two major meta-analyses (Amato, 2001; Emory, 1999). Additionally, family conflict (i.e., discord, disagree- ments, expressed anger, and/or aggression) and its relationship to the adjustment (i.e., degree of internalizing symptoms, ex- ternalizing symptoms, and/or physiological arousal) of children, adolescents, and young adults has been extensively investigated with consistent findings demonstrating that high levels of per- ceived family conflict are associated with children, adolescents, and young adults manifesting psychological distress and mal- adjustment (Borrine, Handal, Brown, & Searight, 1991; Dancy & Handal, 1984; Enos & Handal, 1986; Kleinman, Handal, Enos, Searight, & Ross, 1989). The investigation of perceived family conflict is particularly salient given the rise of sin- gle-parent families as a consequence of rising divorce rates in the United States. Unlike family conflict, conflict resolution (i.e., “behaviors that regulate, reduce, or terminate conflicts;” Davies & Cum- mings, 1994), and its relationship to adjustment has not been as widely investigated. The limited empirical research investigat- ing conflict resolution and its effects on adjustment appears to indicate conflict resolution is associated with a decrease in negative reactions in children (Davies & Cummings, 1994), and a decrease in aggression and expressed anger by children (Cummings, Iannotti, & Zahn-Waxler, 1985). It is notable that the bulk of research in the area of conflict resolution and its effects on adjustment has been conducted in a laboratory setting and measured dichotomously, with conflict being defined as either resolved or unresolved. As is noted by Davies and Cummings (1994), conflict reso- lution is not a dichotomous variable, as many researchers have treated it. Instead, there may be different means of measuring conflict resolution, or perhaps non-resolution. For example, when a conflict occurs among family members, behaviors such as yelling, fighting, and/or arguing suggest that the conflict remains unresolved. In addition, avoidance of the problem may suggest that the conflict is not resolved. It has been argued that active avoidance of a conflict indicates a failure to resolve the conflict situation (as cited in Johnson, LaVoie, Spenceri, &  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. Mahoney-Wernli, 2001). More recently, Roskos, Handal, and Ubinger (2010), after reviewing the literature on conflict resolution, also indicated a need for a measure of conflict resolution that was not dichoto- mous, but rather dimensional, as well as the need for a measure that would tap conflict resolution as perceived by the child, adolescent, or young adult. In order to remedy this deficit, Roskos et al. (2010) developed a dimensional measure of con- flict resolution, and investigated conflict resolution’s relation- ship to perceived family conflict, as well as to adjustment in a sample of young adults. They found that young adults who reported low levels of perceived family conflict resolution re- ported significantly more distress than did young adults who reported high levels of perceived family conflict resolution. In fact, the young adults who reported low levels of conflict reso- lution had an aggregate mean score on an epidemiological measure of distress and need for treatment that exceeded the clinical cutoff score for the presence of distress, while those individuals who reported high levels of perceived conflict resolution had an aggregate mean score below that cutoff score. In essence, Roskos et al. (2010) reported both statistical sig- nificance and clinical meaningfulness for their findings. Unfor- tunately, conflict resolution and its impact on psychological adjustment have not been examined in an adolescent population using a dimensional measure of conflict resolution such as the FCRS (The Family Conflict Resolution Scale). The FCRS includes one item assessing whether families avoid conflicts. Serendipitously, Roskos et al. (2010) found that young adults who reported that their families primarily dealt with conflict through the use of avoidance, and as such were classified as avoidant of conflict, reported maladjustment scores that were significantly higher than those individuals who re- ported that their families tended to resolve conflict. This finding also was statistically significant and clinically meaningful and indicates that the continued presence of either conflict or con- flict avoidance (i.e., indirect efforts to alter stressful situations) is equally deleterious to the mental health of young adults. Furthermore, the young adults who reported that their family uses avoidance as a coping method did not differ from a group of young adults who reported, via measures of psychological symptomatology, that their families primarily employed con- tinued yelling. Interestingly, the avoidant group reported con- flict scores on the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1994) equal to the mean for the standardization sample. In other words, if one only considered these subjects’ reports of perceived family conflict, these individuals would never have been flagged as at-risk for adverse mental health issues. This finding underscores the importance of investigating all of the possible ways an individual could manage conflict, ranging from continuing to maintain high conflict, through avoidance of conflict, to addressing conflict by resolving it. To the authors’ knowledge, there is only one study that specifically examines the relationship between conflict avoidance and maladjustment, and unfortunately, the sample only included 4th and 8th grade students (Johnson et al., 2001). Additionally, the lack of re- search on conflict avoidance, suggests there is a need to de- velop dimensional measures of conflict avoidance (as opposed to one item). The current study had two primary aims. First, the authors’ sought to determine whether the relationship between conflict resolution, conflict avoidance, and adjustment, as reported by Roskos et al. (2010), would extend downward to adolescents. Specifically, the authors hypothesized that family conflict re- solution, as measured by the Family Conflict Resolution Scale (FCRS; Roskos et al., 2010) would be negatively correlated with family conflict, as measured by the FES (Moos & Moos, 1994). Additionally, the authors predicted that low levels of family conflict resolution would be significantly related to higher levels of psychological maladjustment, as measured by the Langer Symptom Survey (LSS; Langner, 1962), and lower levels of positive adjustment, as measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffen, 1985). Third, the authors hypothesized that conflict avoidance, as measured by the Avoidant Conflict Behavior Scale (ACBS), would be significantly predictive of higher levels of psycho- logical maladjustment and lower levels of positive adjustment. Secondly, the present investigation aimed to develop a di- mensional measure of conflict avoidance as opposed to the one- item assessment used in previous research (Roskos et al., 2010). It was designed to define specific behaviors that characterize conflict avoidance, as well as to provide a more thorough evaluation of avoidance. The authors collected information with regards to the measure’s psychometric properties including: sample mean and standard deviation, internal consistency, sam- ple cutoff scores, and factor analytic properties. Methodology Participants Approximately 700 students were recruited from four paro- chial high schools in a large Midwestern city. The final sample included 102 adolescents (14.6% return rate). The participants were between the ages of 14 to 19 (M age = 16.58 years, SD = 1.36). The sample consisted of 64 females (62.7%) and 38 males (37.3%) participants. The racial/ethnic composition of the sam- ple was predominantly Caucasian (95.1%). The remaining ra- cial/ethnic distribution was as follows: African American (n = 0, 0%), Hispanic (n = 1, 1%), Asian American (n = 0, 0%), Native American (n = 1, 1%), and Other (n = 3, 2.9%). Although ado- lescents in grades 9 through 12 were represented, the partici- pants were primarily in grade 12 (n = 47, 46.1%). The remain- ing grades were represented as follows: 9th grade (n = 15, 14.7%), 10th grade (n = 17, 16.7%), and 11th grade (n = 23, 22.5%). Socioeconomic status was assessed by examining re- ported maternal and paternal income, educational level, and employment status. The maternal median income for those reporting (n = 81, 79.4%) was $30,001 to $40,000, while the paternal median income for those reporting (n = 83, 81.4%) was $50,001 to $70,000. The median parental educational level for those reporting was college graduate for both mothers (n = 98, 97.1%) and fathers (n = 98, 96.1%). The median parental employment status for those reporting was full-time for both mothers (n = 100, 98%) and fathers (n = 100, 98%). Measures Conflict Scale of The Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1994). The FES is a 90-item true-false instru- ment that yields standard scales on 10 subscales designed to assess family environment. Of these 90 items, the nine items that comprise the conflict scale were used to assess the amount of expressed anger, aggression, and conflict among family members. Items endorsing family conflict are scored as 1, while items that do not endorse family conflict are scored as zero. The Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 51  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. items are summed to yield a total score, with higher scores indicating high levels of family conflict. This measure has fre- quently been utilized with adolescent populations (Dancy & Handal, 1984; Enos & Handal, 1986; Gregory, Caspi, Moffitt, & Poulton, 2006; Kleinman et al., 1989; Ross, Marrinana, Schattner, & Gullone, 1999). Validated cutoff scores for the conflict scale have been de- veloped to categorize high, middle, and low conflict families. High conflict families fall more than one standard deviation above the mean, middle conflict families fall within one stan- dard deviation of the mean; low conflict families fall more than one standard deviation below the mean (Kleinman et al., 1989). In the current sample, high conflict families reported scores greater than six, middle conflict families reported scores be- tween 2 and 5, and the low conflict families reported scores of either 0 or 1. In a normative sample, the mean score on the conflict subscale was 3.18 (SD = 1.91), the internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) was α = .75, and the two-month test-retest reliability was .85 (Moos & Moos, 1994). The Family Conflict Resolution Scale (FCRS)—Family Resolution scale. This is an 18-item self-report scale devel- oped by Roskos et al. (2010) in order to assess conflict resolu- tion within the family system. The subscale was initially de- veloped as a component of a broader measure for use with a college-age sample. The measure’s items were generated through both empirical and rational methods. First, the re- searchers conducted a literature search and included items from instruments such as the Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC; Grych, Seid, & Fincham, 1992), the FES, and the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979), which tapped into the construct of conflict resolution. Items that appeared appro- priate from these measures were included in the FCRS. Second, items were generated by Roskos, a fellow student, and a re- search supervisor. Items were rationally constructed and ap- peared content valid. Roskos (2010) conducted a pilot study of the measure with 10 people. Of the 18 items, 14 are answered using a true/false response format. Responses endorsing resolution items are scored as a 1, while responses endorsing non-resolution items are scored as 0. Participants rate items 15, 16, and 17 on a 7-point Likert scale; anchors for the items range from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Items 1 to 17 are summed to provide the score for conflict resolution, with higher scores indicating higher levels of conflict resolution. Item 18 is a categorical self-report item that requires partici- pants to best describe how disagreements among family mem- bers are typically handled. Only the first 17 items were used in the present study. Roskos et al. (2010) developed cutoff scores in order to categorize high, middle, and low levels of family conflict reso- lution utilizing his study sample (N = 332). High levels of fam- ily conflict resolution fell more than one standard deviation above the mean, middle family conflict resolution fell within one standard deviation of the mean, and low family conflict resolution fell more than one standard deviation below the mean. The mean score of Roskos et al.’s (2010) sample on the scale was 20.43 (SD = 6.74), and they reported an internal con- sistency of α = .87. To date, the FCRS and its cutoff scores have not been validated. Although the FCRS was originally developed for use with a college-age sample, the authors were interested in evaluating the use of the FCRS in an adolescent population. The authors believed that the FCRS items would be valuable in measuring family conflict resolution in the current study because it pro- duced strong results in the Roskos et al.’s (2010) study. There- fore, the authors believed the measure would potentially pro- duce strong results in the current study because the adolescents were currently living with their families, as opposed to the col- lege students. Avoidant Conflict Behavior Scale (ACBS). The ACBS is a pilot measure developed for use in the current study, which includes 15 true-false-items assessing avoidant behaviors. The study conducted by Roskos et al. (2010) suggested that current measures of family conflict and resolution are not adequately screening for avoidance of conflict; they believed this is a po- tential problem and proposed further definition of avoidant conflict behavior. This measure is an attempt to further define and adequately assess for conflict avoidance. The author of this measure derived items from the avoidant coping and conflict resolution literature that reflected a range of avoidant behaviors and had originated within the following instruments: Response to Stress Questionnaire (Connor-Smith et al., 2000), the Coping Across Situations Questionnaire (Seif- fge-Krenke, 1995), a measure of conflict tactics (Feldman & Gowen, 1998), a measure of conflict resolution (Owens, Daly, & Slee, 2005), and an interpersonal conflict style inventory (Rahim, 1983). The author also rationally derived additional items that appeared content valid. Examples of items include: “In my family, we avoid discussing differences;” “In my family, when we have a disagreement we leave the room;” “In my fam- ily, we avoid disagreements.” Responses endorsing avoidant conflict behavior were scored as a 1, while responses endorsing non-avoidant behaviors were scored as 0. The items were then summed, with higher scores indicating higher levels of avoidant conflict behaviors. Cutoff scores were developed to categorize high, middle, and low levels of avoidant conflict behavior. High levels of avoidant conflict behavior fell more than one standard deviation above the mean, middle levels of avoidant conflict behavior fell within one standard deviation of the mean, and low levels of avoidant conflict behavior fell more than one standard deviation below the mean. The mean score of the current sample on the ACBS was 3.85 (SD = 2.69), and the internal consistency was α = .69. Langner Symptom Survey (LSS; Langner, 1962). The LSS was used as a measure of current psychological adjustment. It is comprised of 22 self-report items that represent symptoms of depression, anxiety, social isolation or withdrawal, and psy- chophysiological complaints. Each item is scored either 0 (ab- sence of symptoms) or 1 (presence of symptoms). Higher scores indicate greater psychological distress or impairment. Langner (1962) reported the mean score on the measure in various treatment groups: outpatients (M = 4.78, SD = 3.27), ex- patients (M = 4.20, SD = 3.35), and non-patients (M = 2.60, SD = 2.67). The LSS has a reported internal consistency of α = .80 (Dohrenwend et al., 1980). Furthermore, a cutoff score of 4 or more has been reported to differentiate patients from non-patients and correctly identify 84% of those with psycho- logical difficulties (Langner, 1962). The measure is correlated nega- tively with a measure of well-being, which supports its concur- rent validity. The cutoff score of 4 has been validated for adolescents. The LSS accurately identified 82% of adolescents never in treat- ment, 76% of adolescents in outpatient treatments, and 79% of adolescents in inpatient treatment (Handal, Gist, Gilner, & Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 52  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. Searight, 1993). Therefore, a cutoff score of 4 was used to de- termine the presence of psychological symptoms. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). This is a 5-item measure that as- sesses a person’s global judgment of life satisfaction. Roskos et al. (2010) used the Flanagan Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (FLSQ; Flanagan, 1978) as a measure of positive adjustment. Unfortunately, the FLSQ has never been used in samples of adolescents, and the authors felt it more appropriate to use the SWLS, which has been widely used and validated in interna- tional samples of adolescents. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Total scores indicate whether an individual is satisfied (scores between 26 and 30), slightly satisfied (scores between 21 and 25), equally satisfied and dissatisfied (score of 20), slightly dissatisfied (scores between 15 and 19) or extremely dissatisfied (scores between 5 and 9; Pavot & Diener, 1993). Mean scores for American students range from 23.0 to 25.2 (SD = 6.4 to 5.8; Pavot & Diener, 1993). The instrument shows strong internal consistency (α = .80) and a 2-month test-retest reliability of .82 (Diener et al., 1985). However, the test-retest reliability falls over longer periods of time. In addition, the SWLS has generally been found to be unrelated to gender and age (Pavot, Diener, Colvin, & Sandvik, 1991). Demographic Questionnaire. A demographic questionnaire was included in order to gather information regarding the par- ticipants’ sex, race, age, grade, and their families’ income, education level, and employment status. Procedure Approval was obtained from the Saint Louis University In- stitutional Review Board (IRB) prior to participant recruitment. Data collection occurred from October 2007 to February 2008. Participants were recruited from four parochial high schools in a large Midwestern city. The study investigators initially visited the high schools in order to introduce themselves, brief the students on the purpose of the study, explain the nature of par- ticipation, and to answer any questions the students had. Pack- ets were distributed to approximately 75% of the participants to take home that included a) a cover letter for the adolescent and his/her parent(s) or legal guardian(s) to read, containing a brief description of the study; b) an explanation of the con- sent/assent required to participate in the study; and c) the con- sent/assent form. The remaining participants received the same packet plus the questionnaires. In order to control for the possi- bility that sequencing of measures might influence responding, two forms were used: A and B. Form A had items related to psychological symptoms and life satisfaction first with items relating to family conflict and conflict resolution appearing second. Form B began with family conflict and resolution items, which were followed by the psychological symptoms and life satisfaction measures. To accommodate the requests of the administrative personnel at each of the four high schools, two separate procedures were employed. For the first group, the study investigators collected returned consent/assent forms and distributed questionnaires to the students for completion at school. For the other participants, the participants returned completed consent/assent forms and completed questionnaires to their school within 10 days. In order to guarantee confidentiality for this group, the partici- pants returned completed materials in a sealed envelope to a drop box in the main office. Furthermore, when the completed questionnaires were collected, the consent/assent forms were immediately separated from the response sheets in order to ensure that there was no identifiable information connected to individual data points. Only those questionnaires accompanied by signed consent/assent forms were included in the data analy- sis. Results Demographic Variabl e s and Dependen t Variables In order to determine whether item order had a significant effect on responding, a one-way multivariate analysis of vari- ance (MANOVA) was conducted using form A (N = 49) and form B (N = 53) as the fixed factor and the measure of conflict (FES), the two measures of conflict resolution (FCRS and ACBS), and the two adjustment measures (LSS and SWLS) as the dependent variables (DVs). The analysis resulted in a non-significant MANOVA (Wilks’ λ = .973, F6,95 = .443, p = .848). As a consequence, data from form A and for B was collapsed for further analyses. In order to determine whether the participants’ sex or grade level significantly affected their responses on the conflict measure (FES), the two measures of conflict resolution (FCRS and ACBS), and the two adjustment measures (LSS and SWLS), a 2 × 4 factorial MANOVA was conducted. The analysis revealed no significant main effects for either sex (Wilks’ λ = .954, F6,89 = .716, p = .637) or grade level (Wilks’ λ = .862, F18,252.215) = .757, p = .750), and no significant sex by grade level interaction was found (Wilks’ λ = .843, F18,252.215 = .875, p = .609). As a result, data for males and females and for all grade levels was collapsed in further analyses. The means and standard deviations for all variables in the collapsed sample are shown in the upper portion of Table 1. As can be seen, the sample mean for the FES (M = 3.70) was simi- lar to the mean reported by Moos and Moos (1994) in the man- ual (M = 3.90). Similarly, the FCRS sample mean (M = 19.75) was comparable to that reported by Roskos et al. (2010; M = 20.43). The LSS sample mean (M = 3.75) was similar to the previous reports for adolescents not currently in outpatient or inpatient treatment (Handal et al., 1993; Enos & Handal, 1986; Kleinman et al., 1989). Finally, the SWLS sample mean (M = 24.86) lies within the range of means reported by Pavot and Diener (1993; M = 23.0 to 25.2). The intercorrelations among all variables are presented in the bottom portion of Table 1. As can be seen, family conflict, as measured by the FES, is positively and significantly correlated with the LSS, which replicates previous findings and indicates that the more family conflict that is present in the home, the more likely an adolescent is to experience psychological symp- toms. On the other hand, the FCRS was negatively and signifi- cantly correlated with the LSS, which is not unlike findings with young adults in Roskos et al.’s study (2010). This indi- cates that when families are unable to resolve conflict, adoles- cents tend to experience more psychological symptoms. Finally, the ACBS was positively and significantly correlated with the LSS and inversely and significantly correlated with the SWLS, which suggests that when families employ more avoidant be- haviors during conflict, adolescents tend to experience greater psychological symptomatology and lower levels of satisfaction with life. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 53  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. Table 1. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelation matrix. Dependent Va iable M SD FES 3.70 2.23 FCRS 19.75 5.86 ACBS 3.85 2.69 LSS 3.75 3.42 SWLS 24.86 6.73 FES FCRS ACBS LSS SWLS FES - −.563*** .212* .454*** −.339*** FCRS - −.305** −.379*** .366*** ACBS - .299*** −.217* LSS - −.578*** SWLS - Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; FES = family environment scale; FCRS = family conflict resolution scale—family conflict scale; ACBS = avoidant conflict behavior scale; LSS = langner symptom survey; SWLS = satisfaction with life scale. Perceived Family Conflict, Family Conflict Resolution, and Adolescent Adjustment In order to determine whether the previously reported rela- tionship between conflict and adjustment could be replicated, and to determine whether Roskos et al.’s (2010) relationship between conflict resolution and adjustment could be extended downward to adolescents, two separate MANOVAs were per- formed. Low, middle, and high conflict groups were developed on the basis of the FES sample mean. The low conflict group (N = 15) consisted of participants with a score of 1 or 0 (1 SD below the mean); the middle conflict group (N = 66) consisted of participants whose scores ranged from 2 to 5 (within one SD above and below the mean); the high conflict groups (N = 21) consisted of participants with a score of 6 or greater (1 SD above the mean). Similarly, low, middle, and high conflict resolution groups were developed on the basis of the FCRS sample mean. The low conflict resolution group (N = 14) con- sisted of participants with a resolution score of 1 to 13 (1 SD below the mean); the middle conflict resolution group (N = 73) consisted of participants whose scores ranged from 14 to 25 (within one SD above and below the mean); the high conflict resolution group (N = 15) consisted of participants with a con- flict resolution score of 26 or greater (1 SD above the mean). The results of the first analysis examining the relationship of conflict to adjustment yielded a significant MANOVA (Wilks’ λ = .800, F4,196 = 5.780, p < .001, eta squared = .10). Sufficient power was demonstrated (observed power = .981). Univariate F statistics were significant for both the LSS (F = 9.333, p < .001, eta squared = .159) and the SWLS (F = 8.385, p < .001, eta squared = .145). Tukey HSD post hoc analyses revealed that low and middle conflict groups did not differ from each other but both differed significantly (p ≤ .001) from the high conflict group on both the LSS and SWLS. These results are not only statistically significant but are clinically meaningful, as well, because the high family conflict group exceeded the cutoff score of 4 on the LSS (M = 6.29), while both the low family conflict group and middle family conflict group were below the cutoff on the LSS (M = 2.13, 3.30 respectively). Consistent with the current literature, these results suggest that the high family conflict group has clinically meaningful levels of psy- chological symptoms and lower levels of life satisfaction com- pared to adolescents in the low and middle family conflict groups. The results of the second analysis for the relationship of con- flict resolution to psychological symptoms and life satisfaction yielded a significant MANOVA (Wilks’ λ = .888, F4,196 = 3.006, p < .05, eta squared = .058). Results demonstrated insufficient power of the test (observed power = .792) Univariate F statis- tics were significant for both the LSS (F = 3.709, p < .05) and the SWLS (F = 4.442, p = .01). Tukey HSD post hoc analyses revealed that the middle (M = 3.56) and high (M = 2.67) con- flict resolution groups (p < .01) did not differ significantly from each other on the LSS but both differed significantly from the low (M = 5.86) conflict resolution group. On the SWLS, the middle and the high conflict resolution groups did not signifi- cantly differ from each other; however, only the high conflict resolution group significantly differed from the low conflict resolution group. These results suggest that the low conflict resolution group has clinically meaningful levels of psycho- logical symptomatology compared to those in the middle and high conflict resolution groups, and significantly lower levels of life satisfaction than those in the high conflict resolution group. Moreover, the results paralleled Roskos et al.’s (2010) findings in young adults. In order to determine whether family conflict resolution and conflict avoidance help predict adolescents’ psychological symptoms and life satisfaction above and beyond the informa- tion provided by perceived family conflict, several hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. The first set of hierarchical regression analyses investigated the predictive value of family conflict resolution and conflict avoidance on adolescents’ psy- chological symptoms. In the first hierarchical regression analy- sis, perceived family conflict was entered first, with conflict avoidance and family conflict resolution entered second and third, respectively, in order to predict psychological symptoms. Please see the upper portion of Table 2 for the results of this analysis. A second hierarchical regression analysis that was identical to the first analysis except that it reversed the order of the latter two independent variables, with family conflict reso- lution being entered second and conflict avoidance entered third, was also conducted. The results of the second analysis were comparable to those of the first analysis, and so they are not reported here. In general, the first set of analyses demonstrates that, after considering perceived family conflict, conflict avoi- dance adds significantly to the prediction of adolescents’ psy- chological symptoms, whereas family conflict resolution does not. The second set of hierarchical regression analyses was con- cerned with the predictive value of family conflict resolution and conflict avoidance in regard to adolescents’ life satisfaction. The third hierarchical regression analysis included perceived family conflict, conflict avoidance, and family conflict resolu- tion entered first, second, and third into the equation, respec- tively. Please see the lower portion of Table 2 for the results of this analysis. Similar to the process described above, a fourth hierarchical regression analysis that reversed the order of the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 54  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 55 Table 2. Hierarchical Regression Analyses FES, ACBS, and FCRS’ Prediction of LSS. B SE B β ∆R2 F Model 1 .21 25.949*** FES .70 .14 .45 ACBS FCRS Model 2 .04 5.705* FES .63 .14 .41 ACBS .27 .11 .21 FCRS Model 3 .01 1.450 FES .52 .16 .34 ACBS .24 .12 .19 FCRS −.08 .06 −.13 FES, ACBS, and FCRS’ Prediction of SWLS B SE B β ∆R2 F Model 1 .12 12.958*** FES −1.02 .28 −.34 ACBS FCRS Model 2 .02 2.518 FES −.92 .29 −.31 ACBS −.38 .24 −.15 FCRS Model 3 .04 5.142* FES −.52 .33 −.17 ACBS −.25 .24 −.10 FCRS .30 .13 .26 Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p< .001; FES = family environment scale; FCRS = family conflict resolution scale—family conflict scale; ACBS = avoidant conflict behavior scale; LSS = langner symptom survey; SWLS = satisfaction with life scale. latter two independent variables was also conducted. The re- sults of this fourth analysis were equivalent to those of the third analysis, and they are also not reported here. The second set of analyses indicates that when examining adolescents’ life satis- faction, family conflict resolution is a significant predictor, even after considering perceived family conflict. In these analyses, conflict avoidance did not significantly add to the prediction of adolescents’ life satisfaction. ACBS Factor Analyses Finally, in further evaluating the Avoidant Conflict Behav- iors Scale (ACBS) in terms of its item content, factor analytic techniques were employed. A principal components analysis using a varimax rotation was utilized. The analysis extracted factors based on eigenvalues with a value greater than 1.0. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .687, and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < .001), suggesting that there is reasonable correlation among the items and that the factors extracted are viable. The eigenvalue greater than one criterion was utilized to choose factors in each case. A cutoff of .30 was used to determine items that loaded onto each given factor. Four interpretable factors were extracted. All together the four factors accounted for 55.66% of the total variance after varimax rotation. All 15 items included in the analysis loaded  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. onto a factor, with three items loading onto more than one fac- tor. The first factor included items that addressed denial that conflict exists, and after rotation it accounted for 17.22% of the total variance. The second factor consisted of items that ad- dressed walking away from conflict or pretending conflict does not exist; this factor accounted for 15.42% of the total variance. The third factor included items such as “in my family we do not talk about taboo topics,” suggesting a lack of communication. This factor accounted for 12.23% of the total variance. The fourth factor accounted for 10.80% of the total variance and included items that addressed behaviors such as the silent treatment and avoiding talking. Table 3 provides the rotated factor loadings and a summary of the principal component analysis. Discussion Overall, the results of the current study replicated the exist- ing literature that demonstrated a well-established relationship between family conflict and adolescents’ psychological symp- toms and life satisfaction. More specifically, high levels of family conflict were significantly related to greater psycho- logical symptomatology and reduced life satisfaction in both a statistically and clinically meaningful manner. More importantly, to the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the first study to assess adolescents’ perceptions of conflict resolution within the family and its relationship to ado- lescents’ psychological adjustment using a dimensional meas- ure of conflict resolution. Much of the previous research has been conducted in laboratory setting with younger children using dichotomous measures of conflict resolution. A dimen- sional measure of conflict resolution was developed to remedy the use of dichotomous measures (Roskos et al., 2010), but unfortunately prior to this study it had not been implemented in a population of young adults. Table 3. Rotated factor matrix avoidant conflict behavior scale. ACBS Items Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Communalities Item 3: in my family we do not fight. .820 .018 −.160 .038 .700 Item 8: in my family we do not argue. .750 .085 −.152 .192 .630 Item 14: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we only make positive comments. .736 .086 .218 −.228 .648 Item 10: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we avoid saying negative things. .692 −.111 .086 .010 .498 Item 2: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we walk away and do not discuss the disagreement later on. .072 .804 .127 .012 .669 Item 5: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we pretend the conflict does not exist. .155 .654 .073 .068 .461 Item 12: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we leave the room. −.161 .589 −.237 .463 .643 Item 13: in my family we avoid sharing feelings. −.093 .483 .314 .036 .342 Item 7: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we talk about things we disagree on. −.221 .220 .694 −.042 .581 Item 4: in my family we do not talk about taboo topics. .257 .005 .673 .191 .555 Item 6: in my family we talk about conflict. −.135 .553 .556 −.046 .636 Item 1: in my family we avoid disagreements. .202 −.112 −.016 .762 .580 Item 9: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we get cool and distant (i.e. silent treatment). −.114 .460 .108 .568 .559 Item 11: in my family we avoid discussing differences. .070 .102 .495 .517 .528 Item 15: in my family, when we have a disagreement, we speak directly with one another. −.268 .203 .232 .389 .318 Rotated λ (eigenvalues) 2.583 2.312 1.843 1.620 % of total variance each component accounts for after the rotation 17.22 15.42 12.23 10.80 Note: varimax rotation solution presented. The extracted factors were named as follows: Factor 1: denial of conflict; Factor 2: ignoring a conflict/feelings; Factor 3: lack of communication; Factor 4: behavioral avoidance. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 56  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. Low levels of conflict resolution were significantly related to a greater presence of psychological symptoms in a group of adolescents. Furthermore, medium and high levels of family conflict resolution were significantly related to lower levels of psychological symptoms in both a statistically and clinically meaningful manner. More specifically, the medium and high conflict resolution groups attained mean LSS scores below 4, while the low family conflict resolution group attained a mean LSS score above 4, which is the cutoff for determining which adolescents are distressed and in need of treatment. Addition- ally, it was demonstrated that, after controlling for family con- flict, degree of family conflict resolution is a significant pre- dictor of adolescents’ life satisfaction, whereas conflict avoid- ance is not. These results highlight the importance of further assessing adolescents’ perceptions of family conflict resolution because the resolution of a conflict, or the lack thereof, has consequences for adolescents’ mental health. This will be an important area of continued research, and, in particular, further validation of the FCRS in adolescent populations may be a focus of future research. This study also highlights the importance of assessing a par- ticular approach to conflict resolution, avoidance. The assess- ment of avoidant or passive approaches to family conflict has been neglected in the current literature. The current study is also the first, to the authors’ knowledge to examine the rela- tionship between family conflict avoidance and adolescents’ psychological adjustment. As predicted, higher levels of con- flict avoidance were significantly related to higher levels of psychological symptoms, while it was significantly and nega- tively correlated with family conflict resolution and with life satisfaction. This indicates that individuals who report high levels of conflict avoidance report low levels of conflict resolu- tion in their families and experience deleterious consequences (i.e., reduced life satisfaction and more psychological symp- toms). In addition, the results underscore the importance of the assessment of conflict avoidance above and beyond the level of family conflict because conflict avoidance added significantly to the prediction of adolescents’ psychological symptoms even after considering perceived family conflict, whereas family conflict resolution did not. Overall, this suggests that high lev- els of conflict avoidance are as deleterious to adolescents’ mental health as is the presence of high levels of family con- flict. The current study is also the first to develop and pilot a di- mensional measure of conflict avoidance in an adolescent population. Examination of the item content of the Avoidant Conflict Behavior Scale (ACBS) revealed four interpretable factors (i.e., denial of conflict, ignoring conflict/feelings, no communication, and behavioral avoidance). However, several of the items included in the ACBS appear to be redundant. For example, the items “in my family we do not fight” and “in my family we do not argue,” or, “in my family we avoid disagree- ments” and “in my family we avoid discussing differences” are very similar to one another. In developing the measure the goal was to include more items than may be needed in order to de- termine which items would best measure avoidant conflict be- haviors. Future research employing further trials of this meas- ure may consider consolidating or revising the items. It is promising that the results of the current study closely mirrored the results of Roskos’ et al. (2010) study, suggesting that the ACBS deserves further study to refine and validate the measure in other populations of adolescents. Taken together, the present findings have important implica- tions for screening adolescents for degree of life satisfaction and presence of psychological symptoms. Adolescents in fami- lies who handle conflict with avoidance appear to be at risk for a greater degree of psychological symptoms whereas adoles- cents whose families consistently practice conflict resolution tend to report greater life satisfaction. This unique pattern of relationships suggests that a multidimensional assessment mea- suring both conflict resolution and conflict avoidance is neces- sary in order to obtain the most informative evaluation of an adolescent’s adjustment. In other words, the findings suggest that using measures of family conflict or conflict resolution alone may overlook a group of adolescents who are at risk for psychological symptoms. This study provides initial support for use of the ACBS as a means of identifying adolescents at risk for more severe psychological symptoms, a group that has been previously neglected in the literature. Strengths and Limitatio ns The most significant limitation of the present study was the limited sample size. However, analyses of power suggest that we can have some confidence in the results found, despite the small sample size. Additionally, the study utilized a mono- method approach. The data consisted of self-report information; therefore, there is no way to ensure that the adolescents were reporting entirely accurate levels of family conflict, conflict resolution, life satisfaction, and psychological symptoms. Despite the given limitations, this study has several meth- odological strengths. First, the well-established relationship between family conflict and greater psychological symptoma- tology demonstrated in previous research was replicated. Sec- ond, despite a small sample size, the present results closely mirror the results of a similar study conducted by Roskos et al. (2010) in a college population. Therefore, in combination with the results of Roskos et al. (2010), the current project has the potential to contribute important information that will lead to the examination of previously unexplored dimensions of family conflict. Finally, the sample means on all measures were at or near the normative means for the instruments, which provides greater confidence in the generalization of the results of this study. REFERENCES Amato, P. R. (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990’s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psy- chology, 15, 255-370. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.15.3.355 Borrine, L. M., Handal, P. J., Brown, N. Y., & Searight, H. R. (1991). Family conflict and adolescent adjustment in intact, divorced, and blended families. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 246-250. Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Ps ycho logy , 68, 976-992. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.976 Cummings, E. M., Iannotti, R. J., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (1985). The in- fluence of conflict between adults on the emotions and aggression of young children. Developmental Psychology, 21, 495-507. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.21.3.495 Dancy, B.L., & Handal, P.J. (1984). Perceived family climate, psycho- logical adjustment, and peer relationships of black adolescents: A function of parental marital statusor perceived family conflict? Journal of Community Psychology , 12, 222-228. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 57  M. E. UBINGER ET AL. doi :10.1 0 0 2 /15 2 0 - 6 62 9 ( 1 9 8407)12:3<222::AID-JCOP2290120306> 3.0.CO;2-9 Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulle- tin, 116, 387-411. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387 Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 Dohrenwend, B. P., Dohrenwend, B. S., Gould, M. S., Link, B., Neugebauer, R., & Wunsch-Hitzig, R. (1980). Mental Illness in the United States: Epidemiological Estimates. New York: Praeger. Emery, R. E. (1999). Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Enos, D. M., & Handal, P. J. (1986). The relation of parental marital status and perceived family conflict to adjustment in white adole- scents. Journal of Co n s u l t i ng and Clinical Psychology , 5 4 , 820-824. Feldman, S. S., & Gowen, L. K. (1998). Conflict negotiation tactics in romantic relationships in high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27, 691-717. doi:10.1023/A:1022857731497 Flanagan, J. C. (1978). A research approach to improving our quality of life. American Psychologist, 33, 126-147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.33.2.138 Gregory, A. M., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Poulton, R. (2006). Family conflict in childhood: A predictor of later insomnia. Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorder Research, 29, 1063-1067. Grych, J. H., Seid, M., & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The children’s perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Development, 63, 558-572. doi:10.2307/1131346 Handal, P. J., Gist, D., Gilner, F. H., & Searight, H. R. (1993). Prelimi- nary validity for the langner symptom survey and the brief symptom inventory as mass-screening instruments for adolescent adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 22, 382-386. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2203_9 Johnson, H. D., LaVoie, J. C., Spenceri, M. C., & Mahoney-Wernli, M. A. (2001). Peer conflict avoidance: Associations with loneliness, so- cial anxiety, and social avoidance. Psychological Reports, 88, 227- 235. doi:10.2466/pr0.2001.88.1.227 Kleinman, S. L., Handal, P. J., Enos, D., Searight, H. R., & Ross, M. J. (1989). Relationship between perceived family climate and adoles- cent adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18, 351-359. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1804_9 Langner, T. S. (1962). A 22-item screening score of psychiatric symp- toms indicating impairment. Journal of Health and Human Behavior, 3, 269-276. doi:10.2307/2948599 Moos, R. H., & Moos, B. S. (1994). Family Environment Scale manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Owens, L., Daly, A., & Slee, P. (2005). Sex and age differences in victimization and conflict resolution among adolescents in a south australian school. Aggressive Behavior, 31, 1-12. doi:10.1002/ab.20045 Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164-172. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164 Pavot, W., Diener, E., Colvin, C. R., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Per- sonality Assessment, 28, 1-20. Rahim, M. A. (1983). A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 368-376. doi:10.2307/255985 Roskos. P. T., Handal, P. J., & Ubinger, M. (2010). Family conflict resolution: Its measurement and relationship with family conflict and psychological adjustment. Psychology, 1, 370-376. doi:10.4236/psych.2010.15046 Ross, R. D., Marrinana, S., Schattner, S., & Gullone, E. (1999). The relationship between perceived family environment and psychologi- cal wellbeing: Mother, father, and adolescent reports. Australian Psychologist, 34, 58-63. doi:10.1080/00050069908257426 Seiffge-Krenke, I. (1995). Stress, coping, and relationships in adole- scence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and Family, 41, 75-88. doi:10.2307/351733 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 58

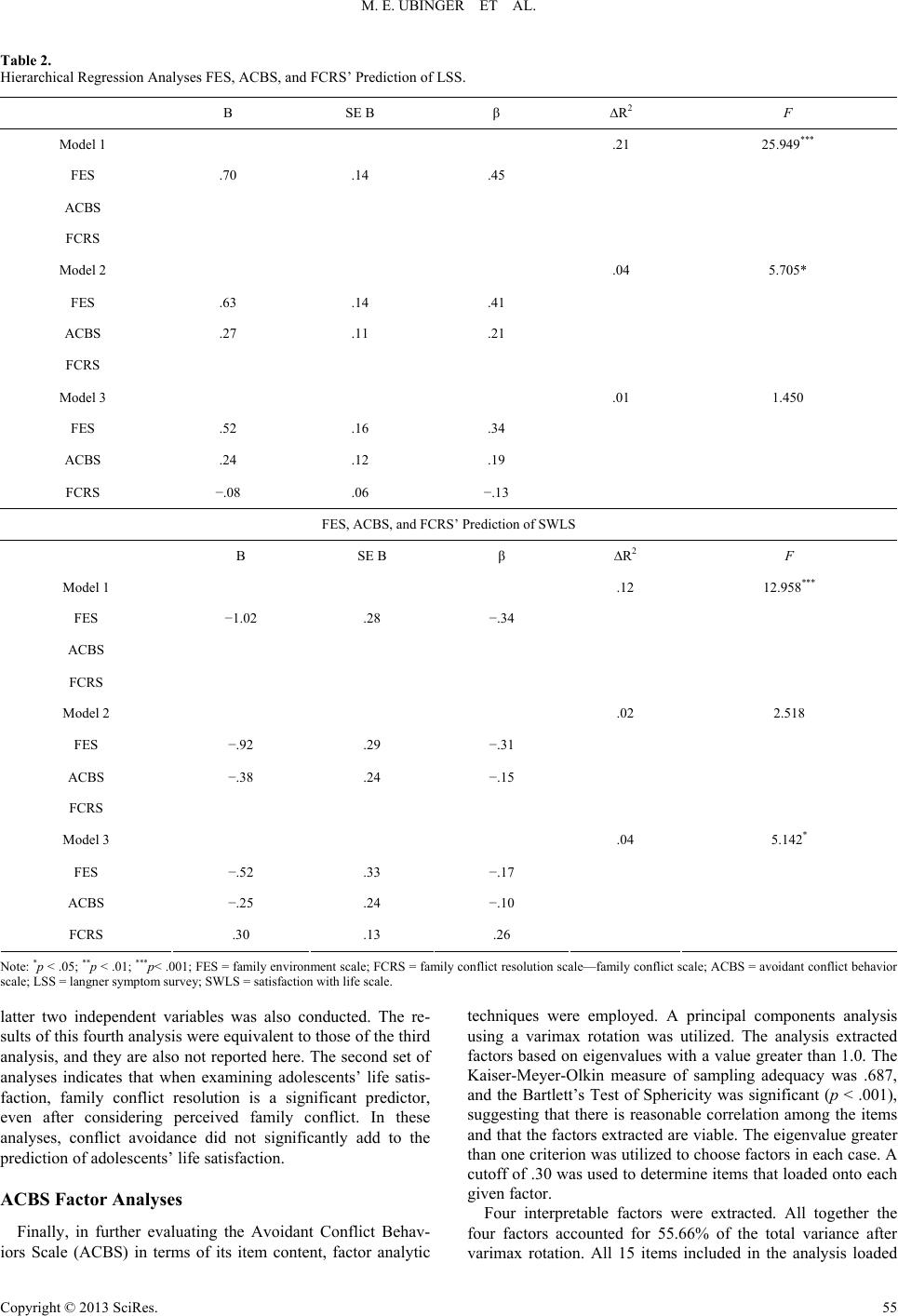

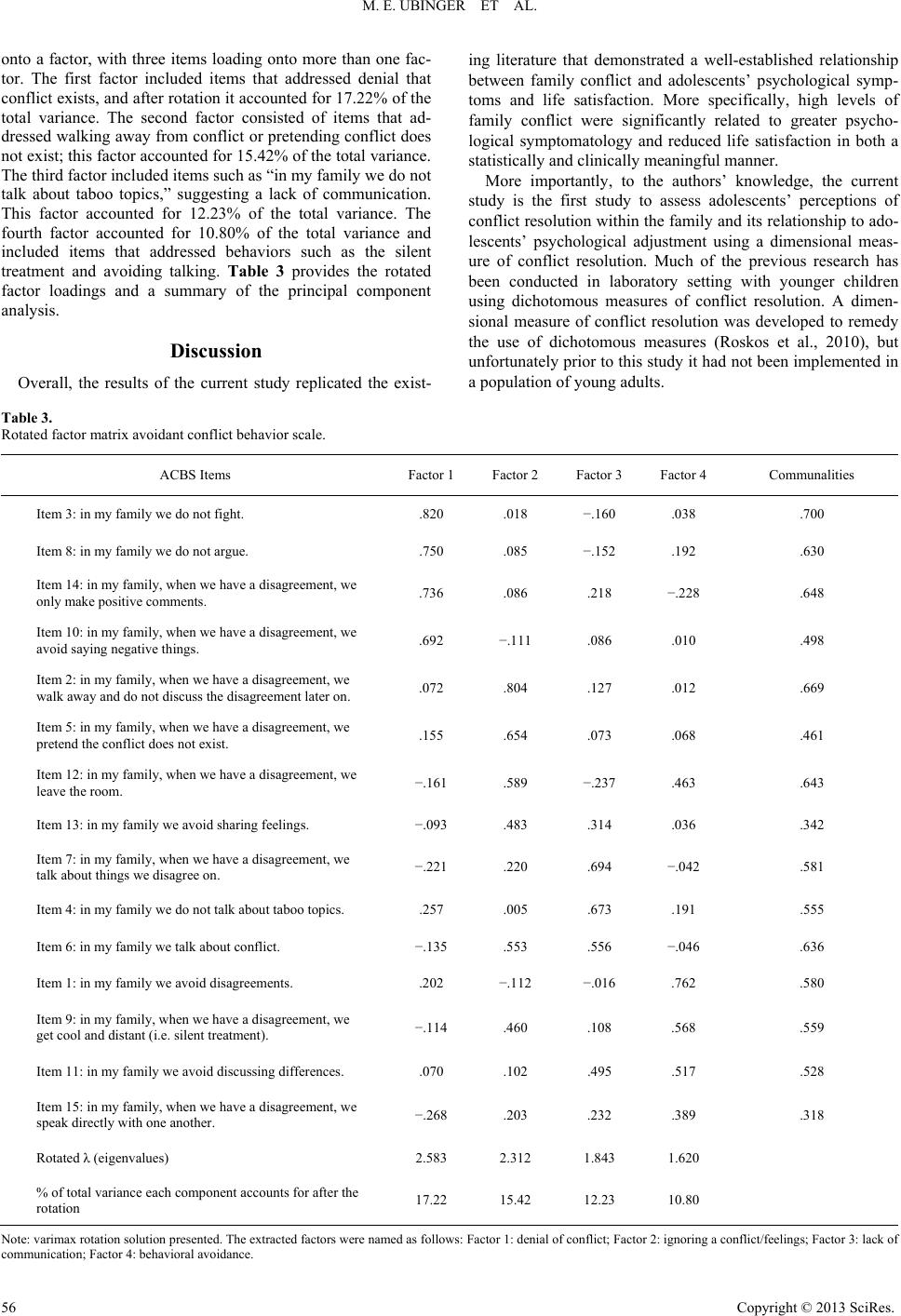

|