Open Journal of Forestry 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 1-7 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojf) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2013.31001 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 1 Forest-Climate Politics in Bangladesh’s Media Discourse in Comparison to Global Media Discourse Md. Nazmus Sa da t h1,2, Max Krott1, Carsten Schusser1 1Chair of Forest and Nature Conservation Po l i c y, Georg August University Goettingen, Goettingen, G e r many 2Forestry and Wood T ech nol og y Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna, Bangladesh Email: mnsadath@yahoo.com, nsadath@gwdg.de Received September 7th, 2012; r evised November 3rd, 2012; accepted November 19th, 2012 Forest and climate issues are prominent within the policies and media in Bangladesh, as well as on the global level. In this study, media discourses from 1989 to 2010 from the “International Herald Tribune” and “The Daily Ittefaq” of Bangladesh are analyzed. Quantitative content analysis classifies 16 frames of the forest and climate issue and 17 political actors. Substantial differences between the forest and climate discourses of the national and international media have been discovered. The national print media reports that the forest is in a crisis due to climate change, whereas the international print media describes the for- est as a solution opportunity to climate change. The hypothesis that the international media drives the na- tional media discourse is rejected. The national media forest and climate discourse in Bangladesh began five years earlier than in the international media, and the different framing of the forest and climate issues can be explained by the influence of strong actors on both the national and international level. Journalists and politicians are the strongest influences in the national print media (The Daily Ittefaq) and primarily frame the discussion around the adverse impact of climate change on the forest in Bangladesh, a country that faces potentially severe effects from climate change. By stressing that climate change has caused a forest crisis, the national media brings attention to a threat that they are not responsible for. Scientists, Non-Governmental Organizations and international organizations are the major voices in the international print media (International Herald Tribune). They shape the global forest and climate media discourse around the wider scope of forests’ role in climate change. International scientists and NGOs present themselves as problem solvers of climate change by framing the discussion around the mitigating role of the forests. These strategic arguments explain the differences in media discourse. Keywords: Climate Change; Forest-Climate Discourse; Political Actor; Media Framing Introduction: The Dynamic Media Discourse about Climate Change and the Forest In the last century, deforestation, desertification and forest degradation have been major environmental problems that have diminished sustainable forest use and caused a significant loss of biodiversity, including the extinction of both flora and faunal species. This loss of biodiversity is the sixth largest species loss in the earth’s history (Leakey & Lewin, 1995; Pimm & Brooks, 2000). Additionally, global warming is magnifying these envi- ronmental threats for the forest. Now that it has become a global issue in political discourse, forest issues are no longer a concern of individual nations. Despite several global initiatives such as FSC, IPF and UNFF, the forest sector did not reach its goal of a united global forest regime or policy. However, in 2008, the forestry sector did find a niche within the already existent climate change regime, and a significant step was made for establishing a global forest regime within the climate change regime (Levin et al., 2008). This new global forest and climate regime (Levin et al., 2008) has contributed to the emer- gence of a forest and climate discourse in the scientific and political arenas at both the global and national levels. There has been rigorous discussion at the international level on creating global initiative to tackle forest climate issue but there has also long been a national perspective to the forest and climate issue, even though the problem exists beyond the na- tional state boundary, in part because there are countries such as Bangladesh that will be affected by this global problem more than others. Bangladesh is located on a delta and faces various adverse impacts from climate change, including on the cur- rently stressed forest sec tor. A major portion of forested land in Bangladesh is situated within the coastal region. The world’s largest single mangrove area, identified as “the Sundarbans”, is a biodiversity hot spot with one of the richest gene pools in the world, but it is directly under threat from sea level rise under various scenarios of climate change (Ali, 1999). Climate chan- ge’s impact on agriculture and the hydrological system will also pose an indirect anthropogenic threat to the existing natural forest of Bangladesh (Huq et al., 1999). Because of the issue’s immense scope, it involves a diverse group of stakeholders at different political levels both nationally and globally. These di- verse stakeholders utilize the media as a platform to spread their viewpoints with the purpose of exerting influence on en- vironmental politics and public opinion; simultaneously, the media assists in the aggregation of interests within the political process, providing a channel for communication and facilitating the revision of shared goals and policies (Curran, 2002). To some extent, the media performs these functions for the public sphere because it provides more open access to various actors (Kleinschmit, 2012). The mass media also plays a crucial role  MD. N. SADATH ET AL. in mediating the process of public deliberation and in the diffu- sion concerns and opinions (Hardt, 2004). In today’s modern complex democratic society, the media is one of the most im- portant sources of information for individuals other than elec- tions and opinion polls; thus, the media reflects the public opinion (Kleinschmit & Krott, 2008). The media has an impor- tant place in both the national and international political level, as it provides the place where different actors build on their arguments with the interest of legitimizing their policies or decisions. By keeping in mind the accelerating political issue of climate change and forests in Bangladesh and the active politi- cal role of the media in forest policy, the study investigates how the media has reported on climate change and the forest issue since its first mention in the late 80s and early 90s. The com- parison between the national and international levels of media is of special interest. Finally, if we find differences between the media, we will look for explanations. Given this background, the following section will organize the research question into three hypotheses guiding the empirical media analysis. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Media Discou rse and th e Framing of the Forest and Climate Issue Discourse is a social construction of reality; that is, discourse produces a specific picture of the issue of forest and climate change (Fairclough, 1995). Keller (1997) approaches discourse as a specific content that is a thematically institutionalized form of text production, comprising public discussions on certain political and/or environmental issues delivered through the me- dia where the conversation and exchange of opinion between relevant actors has occurred. In this study, the forest and cli- mate media discourse is understood as the communication about topics and actors present in the print media that are rele- vant to both the forest and climate change. In the media, the specific topic of climate change and its ef- fects on forests can be viewed from many different perspectives. This phenomenon is addressed by the theory of “framing”. According to Chong and Druckman (2007: p. 104), “the major principle of framing theory is that an issue can be construed as having implications for multiple values or considerations. Fra- ming refers to the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or re-orient their thinking about an issue”. Therefore, to make framing work, one must select specific “aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communication text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, casual interpretation, moral eva- luation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item de- scribed” (Entman, 1993). Framing highlights particular pieces of information about the subject, thereby assigning more impor- tance to those pieces than to others (Prittwiz, 1990; Entman, 1993). The framing of the topic by different actors in the media on the national and international political levels may be different, as the problem’s definition, perception and interest for a single state that is heavily impacted by climate change might be dif- ferent from an international perspective (Takahashi, 2008). Although existing literature was not found regarding this exact phenomenon, Kingdon (2003) mentioned in his policy agenda setting theory that public opinion on a particular issue may differ with location (Kingdon, 2003). In addition, the audience of the global media is different from that of the national media, and every media outlet is very careful to satisfy their audience or readership; thus, the framing of similar issues (Gerhards, 1994; Boykoff & Boykoff, 2004) may be different in the print media at the international level when compared to the national print media. Therefore, this study’s first hypothesis as follows: “The media actively frames forest and climate change issues. Therefore, how the issue is presented depends on the media; hence, the framing of national media is different than that of international media.” National and International Me dia This study’s objective is to analyse the difference in media discourse at both the international and national levels; therefore, it is imperative to explain the globalization of the media. Al- though the media is highly recognized as a driving force of globalization (Kleinschmit & Krott, 2008), the literature on the international or global media lacks a common definition. Many scholars refer to the international media within a technical con- text, e.g., new communications technologies or multi-national media industries (Held et al., 1999). In regard to the topics on which international media reports, the definitions become more abstract, referring to the scope and composition of the audience (McQuail, 2010). We follow the definition of Reese (2010), stating that trans- or international media are those who can ob- tain news from transnational boundary sources and can address a wider audience beyond national boundaries, such as the “In- ternational Herald Tribune” or the “Financial Times” (Reese, 2010). In contrast, national media such as “The Daily Ittefaq” of Bangladesh is characterized by content with respect to lan- guage and substance, which provides the public sphere with a national perspective on Bangladesh (Rahman, 2010). In recent years, he international and national media have shifted their focus from more local and regional environmental issues to more global issues, such as global warming, ozone layer deple- tion and the extinction of species (Mazur & Lee, 1993). Be- cause of this shift in environmental reporting, it is important to question whether there is any link between the international and national media. It is clear that international print media such as the “International Herald Tribune” have more resources to co- ver global events and, as a result, have a larger news pool (Wu, 1998). In contrast, national media, such as “The Daily Ittefaq” of Bangladesh, lack the resources to cover global environmen- tal issues first hand and tend to depend on international sources for their stories. Therefore, there is a greater chance that na- tional print media will follow international print media in re- porting global environmental issues such as forest and climate politics (Mazur & Lee, 1993). Based on this globalization of news, this study’s second hypothesis as follows: “International media claims to address important global issues first. Therefore, the forest and climate change issue is mentioned in the interna- tional media prior to the national media of Bangladesh.” Explaining Framing by Political Actors Framing is part of the communicative strategy of political actors. It is influenced by the strengths of the actors, which is not only limited to their status and resources but also depends on how much value they bring to forest and climate issues. By combining these three factors, the standing of a certain actor or a group of actors is determined in the media discourse, i.e., t he strength of a certain actor or group of actors having a voice in the media in comparison to others (Feindt & Kleinschmit, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 2  MD. N. SADATH ET AL. 2011). In this study, we used speakers as political actors. The frequency of the appearance of a certain actor in the media as a speaker on a certain topic or field is a good indicator of media standing. The higher standing of certain actors in forest and climate media discourse provides that speaker with more op- portunities to shape and/or frame the discourse in accordance with his or her interests or viewpoint (Sadath et al., 2012). In depicting certain events, the speaker stresses some aspects of a situation and downplays other aspects (e.g., Schäfer, 2008), which in turn has implications for how the speaker might bene- fit from specific frames (Sadath et al., 2012). Based on this strategic framing theory, this study’s last hypothesis is as fol- lows: “Topics and framing within the media are influenced by the actors that speak in the media. Therefore, strong actors and their interests can explain the content and the timing of frames in both the national and international media.” Methodology Two reputable daily newspapers, “The Daily Ittefaq” and “International Herald Tribune”, were selected to represent the national and international print media, respectively, for the analysis. The Daily Ittefaq was selected because of the news- paper’s popularity in Bangladesh and its ability to reach Bang- ladeshi political elites and decision-makers (Sadath et al., 2012). The print media selection for international media is critical, as the definition of global media is not very clear among scholars (Park, 2009). Following UNESCO (1997) and Sparks (1998), The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Interna- tional Herald Tribune are considered to be reputable interna- tional publications (UNESCO, 1997; Sparks, 1998). The first two print media do not focus on environmental issues, but rather focus on financial and economic reporting. The Interna- tional Herald Tribune publishes articles with a broader range of issues and subjects, including the environment, politics, culture and sports. In addition, two thirds of the readers of the Interna- tional Herald Tribune are non-American, and the newspaper is sold in more than 160 countries and territories (IHT, 2012). Therefore, the “International Herald Tribune” was selected to represent the print media discourse at an international level (Sadath et al., 2012). Relevant articles of the “International Herald Tribune” were identified using the LexisNexis database, and the relevant arti- cles from the national newspaper “The Daily Ittefaq” were collected manually using the national library archive of Bang- ladesh. The search was limited to the years between 1989 and 2010 because since 1989, the climate change issue had gained momentum in international and national environmental discus- sions and subsequently international negotiation had begun. The database search for relevant articles was performed using the keywords “Climate change” and “Forest”. The resulting ar- ticles were then screened to obtain the relevant articles with the screening criterion containing at least one paragraph within the article that linked the forest to climate change. As a result, a number of articles were identified and in this sample: the “In- ternational Herald Tribune” yielded 90 articles with 149 state- ments, and the “The Daily Ittefaq” of Bangladesh yielded 49 articles with 52 statements. Quantitative-qualitative content analysis was then performed on these newspaper articles to determine their general impres- sion regarding forest issues connected to climate change and how these topics are framed. Content analysis is the method used for elevating social reality, utilizing both a manifest and non-manifest context. According to Krippendorff (1980), con- tent analysis is the research technique for making valid, expli- cative inferences from data about their context. In addition, content analysis is the appropriate method for objectively iden- tifying significant text within a large volume of newspaper text (Neuman, 2006). A coding system was developed to interpret the data. This coding system used two units of analysis: the article and the statement. A statement refers to what has been spoken by a certain actor or speaker on the selected issue. Every speaker may have been coded in more than one place in the same article, but all of his or her discussions was coded together as one statement. The selected articles were first coded according to date, media sources, news factors, events and newspaper sections. Then, at the statement level, each speaker was coded according to their typology: politicians, civil ad- ministration, forest and environment administration, scientists, journalists, forest enterprises, forest and non-forest non-gov- ernmental organizations (NGO), interstate organizations (such as the UN and EU), the World Bank, local individuals and ex- perts. This speaker classification is based on the various types of involved stakeholders or actors in the forest and climate change issues (Park, 2009; Real, 2009). The next step was to determine the frames from each statement made by the indi- vidual speakers. Framing is the process of highlighting certain aspects of the forest and climate problem in terms of its causal interpretation (i.e., diagnostic frame), graveness and urgency of the issue (i.e., motivational frame) and/or solution suggestions (i.e., prognostic frame) (Feindt & Kleinschmit, 2011; Park, 2009; Entman, 1993; Bendford & Snow, 2000; Semetko & Val- kenburg, 2000). Based on these framing elements, this study formulates 24 frame categories covering the aspects of how the forest was related to climate change. For example, in using the forest as a carbon sink, the frames are the forest’s use of CO2, climate change and forest productivity, climate change and bio- diversity, sea level rise and forest cover and climate change in relation to wildlife conflicts. These frames are drawn from the literature review on forest and climate change issues at the glo- bal level (Real, 2009; Etkin & Ho, 2007) and from the Bangla- desh climate change assessment report (MoEF, 2008). Then, the statements made by each actor/speaker were categorized ac- cording to the ways they related the forest with climate change. Several roles of the forest were framed for mitigating global warming or climate change by explaining how several forest issues such as deforestation and illegal logging are contributing to climate change and how climate change will affect the forest and biodiversity (Park, 2009; Kleinschmit et al., 2009). Results: The Two Worlds of National and International Media Discourse Framing of the Forest within the Climate Change Media Discourse The analysis of framing the forest issues within climate change discourse using the different speakers indicated differ- ences between the two media. The frequencies of specific fra- mes are measured by the percentage of the total number of statements about forest and climate frames in each of the media (i.e., the “International Herald Tribune” (n = 149) and the “The Daily Ittefaq” (n = 52)). In total, 16 frames were found from the 24 pre-fixed frames. This reduction indicates that media does not report on every aspect of the forest and climate issues; Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 3  MD. N. SADATH ET AL. rather, they are selective in choosing the frames that pass th- rough their selection filter. The 16 frames found are not equally represented in both media, but both international and national print media each stressed some of these frames. The national print media stressed on more motivational frames (i.e., the gra- veness and urgency of the issue), whereas the international print media stressed on prognostic frames (i.e., problem solving sug- gestions). In the national print media, motivational frames are dominant (see Figure 1), which depict the adverse impact of climate change on the forest, e.g., the loss of forest land due to sea level rise (34.62%), the forest’s difficulty in coping against climate change (17.31%) and climate change’s effect on biodi- versity (3.85%). In addition, prognostic frames, which talk about the forest’s role in adapting to climate change, are also present in the national media but in a smaller percentage, as the forest’s positive role as a carbon sink (11.54%) and the role of affore- station in the adaptation against climate change (13.46%). An- other share of frames (13.46%) are diagnostic frames that de- pict deforestation as a contributor to climate change, with 5.77% of the frames found in the national print media agreeing that REDD is the right instrument to handle the situation (see Figure 1). In the national print media, the frames are more inclined to support the crisis argument that the forests of Bang- ladesh are facing an imminent threat from the global environ- mental problem of climate change. This kind of framing in the national media may have resulted from the tendency to shift responsibility outside the national boundary in order to obtain more international assistance in solving the problem. Figure 1. Forest frames in the climate change media discourse (by share of all statements about frames in %). The media frames within the international media highlighted th , framing mostly highlights the po ortance of the forest within the climate dis- co e forest’s role in mitigating climate change, where the forest as a carbon sink was the most dominant frame with 21.52%; the use of the forest for mitigating and adapting CO2 (8.86% and 11.39%, respectively) were also mentioned. While the potential threat of climate change to forests is present in a smaller per- centage, with 0% of sea level rise as a threat to forest cover, the forest’s difficulty to adapt against climate change represents 7.59%, and climate change’s effect on biodiversity represents 3.80%. However, 7.59% of frames in the international media did conclude that REDD is the right instrument for reducing emissions from deforestation. In international print media tential role of the forest in mitigating climate change prob- lems and downplays the potential threat of climate change to the forest and its biodiversity. On the contrary, in national me- dia, the framing of the forest and climate issue is characterized as the traditional forest in crisis. For example, Ataur Rahman, an environmental activist, used the forest in crisis argument in his framing of the forest and climate issue: “13% of Bangladesh coast with the Sundarbans may go under water during the next 50 years” (The Daily Ittefaq, 10.11.2007). The empirical find- ings support the first hypothesis, which states that the framing of the forest within climate change discourse is quite different in international print media when compared to the national print media of Bangladesh. Early Forest and Climate Discourse in the National Media The relative imp urse is reflected in the growing attention it has received in the national and international print media between 1989 and 2010 (Figure 2). A total of 49 newspaper articles dealing with the forest and climate change issue were found in the national newspaper, The Daily Ittefaq. In the international media, i.e., the International Herald Tribune, 90 articles resulted from the collection. The reporting on the forest and climate issue in the national media was first observed in 1989 and 1990. Sporadic reporting was found until it increased beginning in 2006 and peaking in 2010. However, in the International Herald Tribune, reporting on forest and climate issues were first observed in 1995, reaching a strong peak in 2007 (23) with significant re- porting in 2009 (14) and in 2010 (15). This analysis revealed that forest issues were not present in the climate change discus- sion prior to 1999-2000 in international media. However, a small amount of sporadic reporting was found in national media between 1989 and 2000. The trend shows that after 2007, forest issues are more prominent in the climate discussion in the na- tional print media. Figure 2. ticles addressing climate change and forest s. Frequency of ar Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 4  MD. N. SADATH ET AL. The comparison of the frequency of articles proves that the att ces in the content and in the timing of na- tio Strategic Framing by Political Actors in dia, journa lists (46.2%) are the dominant sp journalists are dominant in the national print ention drawn from the national and international media to the forest issues within the climate discussion shows a difference in timing (i.e., the national media linked the forest with global warming or climate change issues before the international me- dia). Five articles were found in the national print media during the first 5 years in The Daily Ittefaq, which primarily expresses the grim danger global warming could bring to the forests of Bangladesh. For instance, the environment minister of Bangla- desh tells the media that “Shundarban will be lost to the sea in the course of time due to sea-level rise” (The Daily Ittefaq, 13. 03.1989). Similarly, an environment staff reporter of The Daily Ittefaq reported that “lowlands of Bangladesh are under a seri- ous threat including the world’s largest mangrove forest” (The Daily Ittefaq, 18.07.1990). An identical statement from the en- vironment minister Mr. Abdullah Al Noman was published: “low-lying coastal land of Bangladesh will be flooded by the year 2050 if the sea-level rose to 32 cm due to global warming and this affects the forest in terms of biodiversity and produc- tion” (The Daily Ittefaq, 28.02.1996). However, the forest as a topic gained more momentum in the climate change discourses after 2006 in both print media where the national media has a consistent growing trend, but in the international media, forests have been mentioned inconsistently in climate change topics; therefore, the empirical findings reject the second hypothesis as the Bangladeshi print media reported before the global media on new global issues, such as the relationship between climate change and forests. There are differen nal and international media discourse. Our next hypothesis provides an explanation by referring to the strategic framing by political actors in the media. Media Discourse In the nat ional me eakers, followed by politicians (28.8%) and scientists (11.5%). Single individuals or communities (5.8%), NGOs (1.9%), de- velopment consultants (1.9%), interstate organizations (1.9%) and administrations (1.9%) represent the rest of the speakers in the national media. However, scientists (34.2%) have dominant standing in the international media, followed by the forest NGOs and other NGOs (22.1%), journalists (12.7%) and inter- state organizations (8.7%). Politicians (6%) and the World Bank (5.4%) are the other two prominent speakers who shape the international forest and climate discourse (see Figure 3). It is evident that the national print media discourse is mostly shaped by the politicians and journalists; thus, the discourse is primar- ily a political one. In the national print media, the discourse is driven by the actors, who need to legitimize their policy deci- sions or need to create a public opinion in favour of their inter- ests. This supports the argument of Bendford and Snow (2000) that framing processes are strategic, deliberative and goal ori- ented, which means that actors frame a certain issue within an broader discourse to pursue their interests (Bendford & Snow, 2000; Somorin et al., 2011). In contrast, the international media is dominated by scientists and NGOs. In this media, the mini- mal presence of politicians is evident. The differential standing of actors in both print media leads to different framings of the forest issue. Politicians and Figure 3. both media. edia, using the forest in crisis frame and stressing the adverse Os focus the global perspective on the for- es Speaker in m impact of climate change on forests, which is beyond their con- trol, as it was in the case of forest dieback in Germany during the 1980s (Glück, 1986; Krott, 2005; Holzberger, 1995). This kind of cr isis framing co mplies with the c oncept of the “pa ra- dox of disaster” in the media, which supports their policy stand- point and interest to scale up the potential danger to the forest from climate change. Such a framing helps the politician’s at- tempts to mobilize public opinion and voters in favour of their policy interests by providing information in a particular order (Kleinschmit & Krott, 2008; Jacoby, 2000). In addition, it also legitimizes the argument that the degrading forest situation of Bangladesh needs foreign help and financing for its conserva- tion (MoEF, 2008). Scientists and NG t as a potential mitigator, representing the solution of global warming in the international print media. However, REDD and afforestation issues have recently been given importance by strong actors in national media, which indicates the motivation for the change of national political actors towards the current forest and climate issues that can bring international finance to the national sector; thus, they are now consistent with the glo- bal forest and climate discourse. That shift in focus supports Hajer’s concept of discourse coalition, i.e., when political ac- tors shift from one discourse coalition to another and adopt a different framing strategy based on the same issues because their interests have shifted or the new framing is more suitable Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 5  MD. N. SADATH ET AL. for their cause (Hajer, 1995). For instance, the prime minister of Bangladesh, ShiekhHasina showed the government’s inten- tion to participate in the REDD process: “Bangladesh is now ready to participate in REDD process under CDM” (The Daily Ittefaq, 01.06.2010). Similarly, Mr.SalemulHuq, a development consultant, stated that “Afforestation is a solution for global warming and could also provide opportunity to Bangladesh”. These two examples along with other similar statements made by actors in the national media during last 3 years indicate a shift in the framing of forest and climate politics from crisis argumentation to the forest as a solution to climate change. The empirical findings show that the powerful political actors are able not only to frame but also re-frame issues and discourses (Arts et al., 2010). Hence, the third hypothesis of the study is supported by the empirical findings. The topics and framing within the media is influenced by actors who speak in the me- dia. Therefore, strong actors and their interests can explain the content and timing in the national and international media. Conclusion: The Different Worlds of The analysis revences between the fo at interna- tio ed by the influence of tudy period, i.e. 2008 and 2009, th analyses show that the media discourse exists on multi- pl Acknowledgements I would like to tmit of SLU, Swe- de REFERENCES Ali, A. (1999). Climateaptation assessment in Media Discourse ealed substantial differ rest and climate discourse of the national and international media. The first hypothesis is supported, which states that there are differences in framing. In national print media, the domi- nant frames exist around the forest in crisis due to climate change arguments (i.e., motivational framing), while in interna- tional print media, the dominant frames describe the forest as a solution to climate change (i.e., prognostic framing). The second hypothesis is rejected, which states th nal media are driving the national media discourse. In the national media of Bangladesh, the forest/climate discourse be- gan five years earlier than in the international media. This ini- tial national media discourse does not mean that international political discourse could not have been influential in Bangla- desh. This may have occurred through political discourse but was not used directly on the media level. The differences in framing can be explain strong actors at the national and international levels. Jour- nalists and politicians are the strongest speakers in the national print media (The Da ily Ittefaq), and they framed the discussion primarily around the adverse impacts of climate change on the forests in Bangladesh, a country that will face severe impacts of climate change. The potential loss of the forest due to a rise in sea level is a major discussion in the national forest and climate discourse. Scientists, NGOs and international organizations are the major speakers in the international print media (Interna- tional Herald Tribune). They shape the global forest and cli- mate media discourse around the larger scope of the forest within climate change. International scientists and NGOs pre- sent themselves as problem solvers in the climate change issue by framing the mitigating role of forests. This solves problems solely on the global level but not for Bangladesh, where the danger of increasing sea level is a primary concern. The scien- tists and NGOs thus adopt the role of global helpers, therefore establishing the third hypothesis, which is that the framing of forest and climate politics is influenced by the speakers who follow their strategic interests. In addition, at the end of the s e powerful actors of Bangladesh (politicians and administra- tion) emphasized the potential use of forest plantations and REDD+ for mitigation. This indicates that the politicians of Bangladesh sense opportunities to obtain financial resources from these global initiatives. This also supports the third hypo- thesis, which is that the strong actors are able to re-frame the media discourse according to the shift of their interests over time. The e levels, is diverse and offers different support for specific policies. However, support by the media for either crisis policy or mitigation policy has not yet induced policy change. In addi- tion to the media discourse, many other factors influence policy making. Our media analysis allows for further research on whe- ther the media discourse reflects and supports different forest and climate policies on the national and international levels. hank Dr. Daniela Kleinsch n, and Mi Sun Park for their help in preparation of the coding book for the content analysis. I am also grateful to the TIFF and SUFONAMA Class of 2011 from Georg-August University and the Students of FWT Discipline of Khulna University Ban- gladesh for coding the sample article. Finally, I would like to thank DAAD for financing my PhD project. change impacts and ad Bangladesh. Climate Research, 12, 109-116. doi:10.3354/cr012109 rts, B., Appelstrand, M., Kleinschmit, D., Pülzl,A H., Visseren-Ha- B Bkoff, J. M. (2004). Balance as bias: Global war- makers, I. et al. (2010). Discourses, actors and instruments in inter- national forest governance. In: J. Raynor, A. Buck, & P. Katila (Eds.), Embracing complexity: Meeting the challenges of international for- est governance. IUFRO. endford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Soci- ology, 26, 611-639 . oykoff, M. T., & Boy ming and the US prestige press. Global Environmental Change, 14, 125-136. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001 hong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annual Review C 05.103054 of Political Science, 10, 103-126. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.0728 Cork: Routledge. ed Eions and discourses urran, J. (2002). Media and power. London/New Y Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractur paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51-58. tkin, D., & Ho, E. (2007). Climate change: Percept of risk. Journal of Risk Research, 10, 623- 641. doi:10.1080/13669870701281462 airclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analyssFi: A critical study of F. (2011). The BSC crisis in German language. London: Longman. eindt, P. H., & Kleinschmit, D newspapers: Reframing responsibility. Science as Culture, 20, 183- 208. doi:10.1080/09505431.2011.563569 erhards, J. (1994) Politische öffentlichkeit. Ein system und akteurs- G G Hronmental discourse. Oxford: He world: New perspectives in the humani- theoretischer bestimmungsversuch. In F. Neidhardt (Ed.), Öffentli- chkeit, öffentliche meinung, soziale bewegungen, kölner zeitschrift für soziologie und sozialpsychologie, sonderheft 34/1994 (pp. 77- 105). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. lück, P. (1986). Seminar “Waldsterben und öffentlichkeitsarbeit”. Allgemeine Fosrtzeitung, 97, 359-364. ajer, M. A. (1995). The politics of envi Oxford University Press. ardt, F. (2004). Mapping th ties and social sciences. Tübingen: F rancke Verlag. Held, D., McGrew, A. et al. (1999). Global transformations: Politics, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 6  MD. N. SADATH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 7 Press. atreute: Hnd adaptation to climate change for Bangladesh. Dordrecht: IH 59755/iht2064_short_history_2012-5. Ja . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. : Leske Und Budrich. and Economic, Knance and social visibility. In T. Sikor (Ed.), Public and Ksis on forest climate policies: A thematic coading book. economics and culture. Stanford: Stanford University Holzberger, R. (1995). Das sogenannte waldsterben. Zur Karrier eines klisches: Das thema wald im journalistischen diskurs. Berg Eppe . uq, S., Karim, Z., Asaduzzaman, M., & Mahtab, F. (1999). Vulner- ability a Kluwer Academic Publishers. T (2012). A short history on the international herald tribune. URL. http://www.ihtinfo.com/media/ pdf coby, W. (2000). Imitation and politics; redesigning modern Ger- many Keller, R. (1997). Diskursanalyse. In R. Hitzler, & A. Honer (Eds.), Sozialwissenschaftliche h e rmeneutik, Opladen Kingdon, J. W. (2003). Agendas, alternatives and public policies. New York: Addison-Wesley Educati on al P ub lis he rs Inc. Kleinschmit, D. (2012). Confronting the demands of a deliberative public sphere with media constraints. Forest Polica 16, 71-80. leinchmit, D., & Krott, M. (2008). The media in forestry: Govern- ment, gover private in natural resource governance: A false dichotomy? London: Earthscan. leinschmit, D., Sadath, N., Park, M. S., & Real, A. (2009). Mthods for media analy Working Paper. Göttingen: Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Institue, Georg August University Göttingen. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2010.02.013 ippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis an intr odology. London: Sage. Kr oduction to its Meth- L. The sixth extinction: Biodiversity and ions from deforesta- Krott, M. (2005). Forest policy analy si . New York: Springer. eakey, R., & Lewin, R. (1995) its survival. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Levin, K., McDermott, C., & Cashore, B. (2008). The climate regime as globel forest governance: Can reduced emiss tion and forest degradation (REDD) initiatives pass a “dual effec- tiveness” test? International Forest Review, 10, 538-549. doi:10.1505/ifor.10.3.538 azur, A., & Lee, J. (1993). Sounding the global alarm: Envi issues in the US national Mronmental news. Social Studies of Science, 23, 681- 720. doi:10.1177/030631293023004003 cQuail, D. (1994). Mass communication theory: An introduction. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAG mE. d.) (pp. 247-270). Los M Nmethods qualitative and quan- Pcation: The P. M. (2000). The sixth extinction: How large, P Theo- Rmass media of Rof global and Rectives on media and Rology Compass, McQuail, D. (2010). Global mass communication. In D. McQuail (Ed.), McQuail’s mass communication theory (6th e Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Wa shington DC: SAGE . oEF (2008). Bangladesh climate change strategy and action plan 2008. Dhaka: Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. euman, W. L. (2006). Social research titavie approach (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson. ark, M. S. (2009). Media discourses in forest communi issue of forest conservation in the Korean and global media. Göttin- gen: Cluvillier Verlag. imm, S. L., & Brooks, T howsoon, and where? Nature and human society: The quest for a sustainable world. Washington DC: Na t io na l A ca dem y Press. rittwiz, V. (1990). Das Katastrophen-Paradox, Elemente einer rie der Umvelt politik. Oplade n: Leske Und Budrich. ahman, M. (2010). Climate change coverage on the Bangladesh. Global Media Journal pakistan edition, 3. eal, A. (2009). Discourses and distortions: Dimensions national forest science communication. Göttingen: Faculty of Forest Science, Georg August University Göttingen. eese, S. D. (2001). Framing public life. Persp our understanding of the social world. Mahwah. eese, S. D. (2010). Journalism and globalization. Soci 4, 344-353. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00282.x adath, M. N., Kleinschmit, D., & Giessen, L. (2012). FrSaming the tiger: S8). Medialisierung der wissenschaft? Empirische Se. (2000). Framing European politics: Sown, H. C., Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., Sonwa, D. J., Sublic sphere? In D. K. Thussu Ting climate change: A comparitive analysis Uallenge of the new tecnology. Wrminants of international news Incongruent media discourses at different political levels as an obsta- cle for biodiversity governance. Forest Policy and Economics (in Re- view Process). chäfer, M. (200 untersuchung eines wissenschaftssoziologischen konzept. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 37, 2006-225. metko, H., & Valkenburg, P. M Acontent analysis of press and television news. Journal of Commu- nication, 93-109. morin, O. A., Bro Arts, B., & Nkemd, J. (2011). The Congo Basin forests in a changing climate: Policy discourses on adaptation and mitigation (REDD+). Global Environmental Change, 22. parks, C. (1998). Is there a global p (Ed.), Electronic empires: Global media and resistance (pp. 108- 124). London: Arnold. akahashi, B. (2008). Fram of a US and a Canadian newspaper. International Journal of Sus- tainability Communication, 152-170. NESCO (1997). The media and the ch World Communicat io n Rep ort, Paris. u, H. D. (1998). Investigating the dete flow: A media analysis. International Communication Gazette, 60, 493-506. doi:10.1177/0016549298060006003

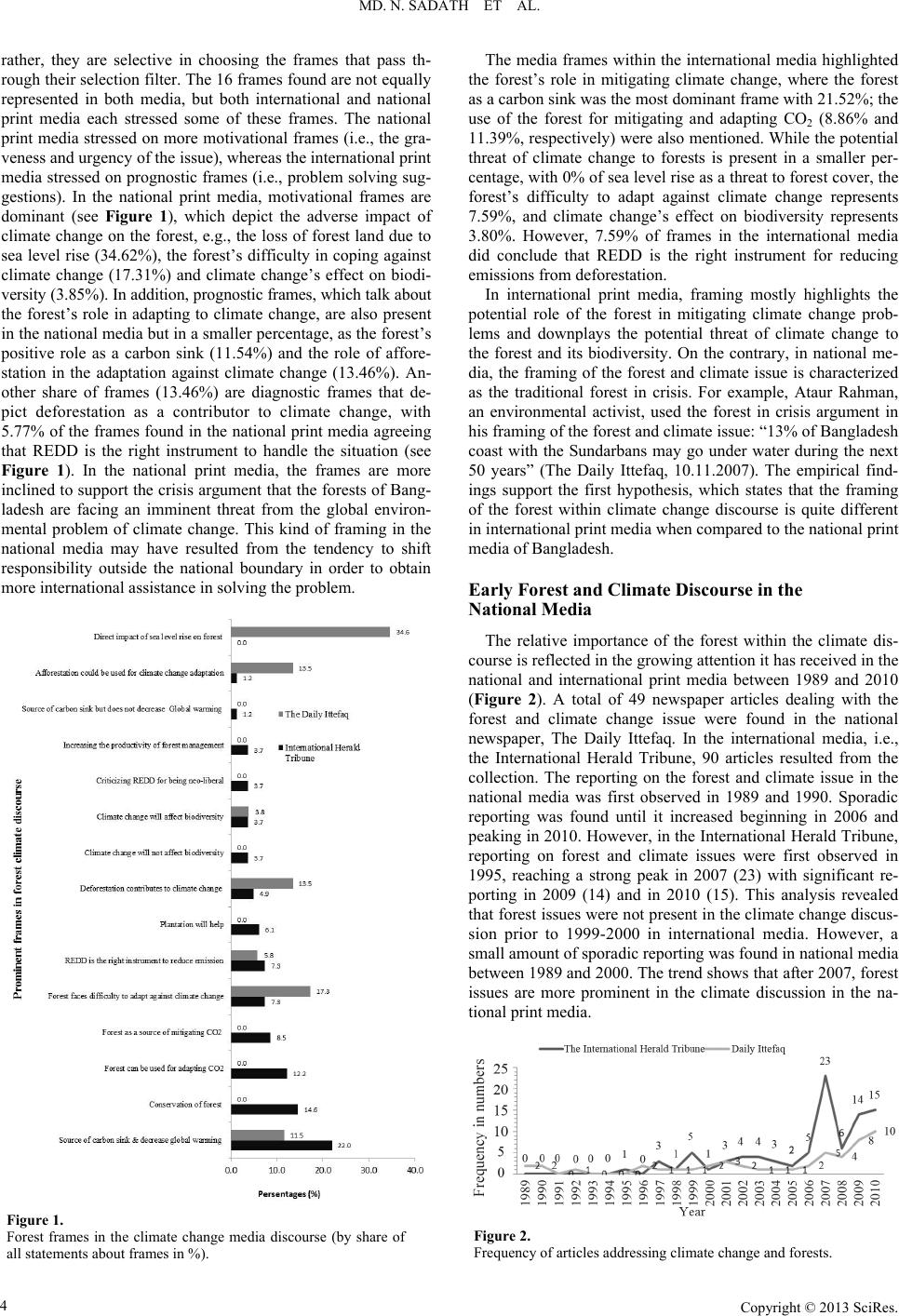

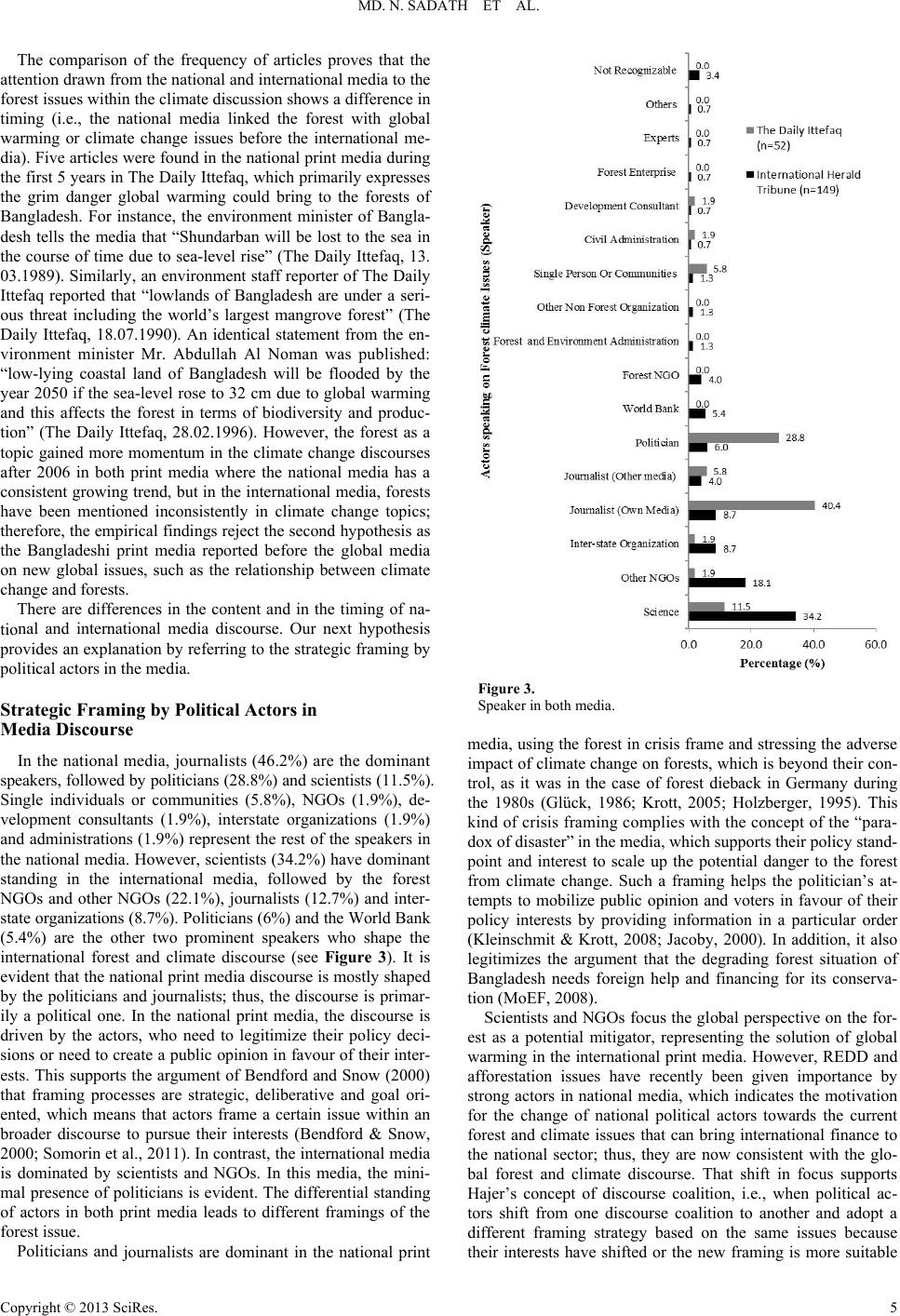

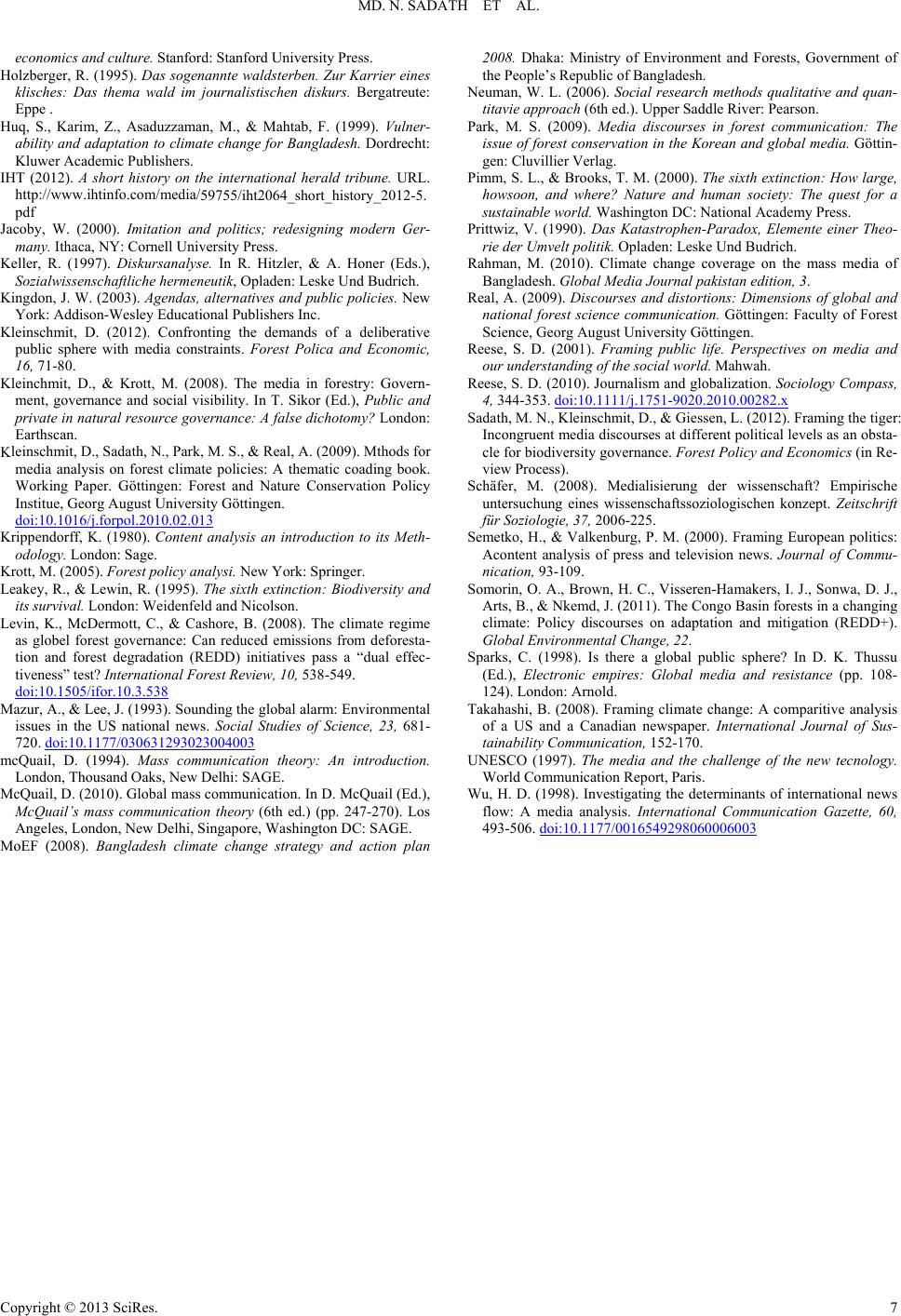

|