Paper Menu >>

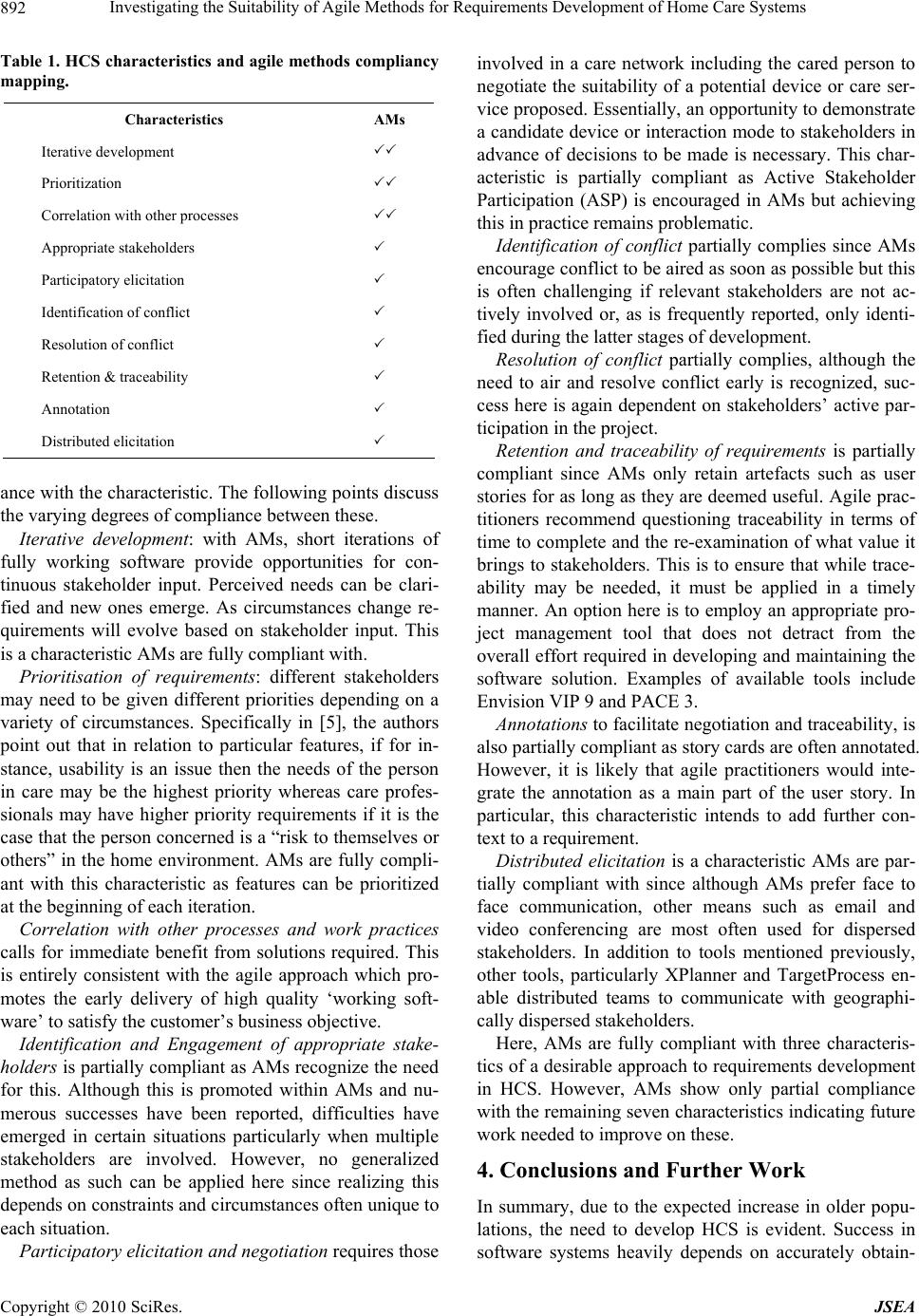

Journal Menu >>

J. Software Engineering & Applications, 2010, 3, 890-893 doi:10.4236/jsea.2010.39104 Published Online September 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jsea) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA Investigating the Suitability of Agile Methods for Requirements Development of Home Care Systems Sandra Kelly, Frank Keenan Dundalk Institute of Technology, Dundalk, Ireland. Email: {sandra.kelly, frank.keenan}@dkit.ie ABSTRACT The ageing population in developed countries brings many benefits but also many challenges, particularly in terms of the development of appropriate technology to support their ability to remain in their own home environment. One par- ticular cha llenge reported for such Home Care Systems (HCS) is the identification of an approp riate requirements de- velopment technique for dealing with the typical diverse stakeholders involved. Agile Methods (AMs) recognize this challenge and propose techn iques that could be useful. This paper examines the desirable characteristics identified for requirements development in HCS and investigates the extent to which agile practices conform to these. It also sets out future work to improve the situation for the non compliant points found. Keywords: Home Care Systems (HCS), Agile Methods, Requirements Development 1. Introduction According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the population of over 60s in developing countries is ex- pected to triple from “400 million to 1.7 billio n” over the next forty years [1]. Rising healthcare costs and lack of resources in terms of hospitals and the availability of skilled doctors and nurses mean that by 2050, this situa- tion will become unsustainable. In Ireland 11% of the population is currently over 65 and this is expected to double over the next 25 years, in particular a threefold increase in those aged 80 and above is expected [2]. Ac- commodating the ageing population is and will continue to be an increasing challenge. For example, Technology Research for Independent Living (TRIL) report that 40% of older people are prematurely institutionalised due to injuries sustained from falls in the home [3]. In general it is beneficial to develop alternative approaches to prevent or delay the institutionalisation of older people, enabling the elderly to remain at home. This has subsequently required an increase in the need to develop HCS. HCS is defined as “a potentially linked set of services including social care and health care that provide or support the provision of care in the home” [4]. Along with the cared person, many other stakeholders are in- volved including family members, social care, home help, health nurses and GPs. Given such diversity of back- ground, perspective and experience, and perhaps geo- graphic distribution, identification, access to and en- gagement of the appropriate stakeholders to identify re- quirements is difficult. To complicate things further, modes of interaction are expected to be subject to con- tinuous change over time as the condition of the home dweller may change [5]. Identification of a more suitable approach for requirements development is necessary. Despite the numerous techniques that exist for re- quirements development [6] and, indeed, efforts made to classify them [7,8] it is claimed that current techniques are inadequate, while McGee-Lennon suggests that a novel approach is required. Despite this, it is acknowl- edged that potential does exist if techniques could be modified to deal with a “combination of multiple distrib- uted and possibly conflicting stakeholder needs” along with “long term configuration and evolution of these needs” [5]. In general, for HCS, any approach should be “lightweight enough to be useable yet rigorous so as to be justifiable” [4]. A potential solution may however be offered through the principles and practices suggested by agile develop- ment. The Agile Manifesto promotes values of close and continuous interaction between all interested stake- holders, including the customer and development team, very short iterations of fully working, and tested, soft- ware, which provides the ability to easily accommodate changing requirements [9]. At an initial inspection it appears that the characteristics of agile development closely match those identified for HCS. This paper compares the desirable characteristics of  Investigating the Suitability of Agile Methods for Requirements Development of Home Care Systems Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 891 requirements development in HCS identified by [5] with the general approach recommended for handling re- quirements in agile development. Section 2 looks at how requirements are developed in an agile setting, Section 3 compares the characteristics of HCS with AMs, while Section 4 concludes th e paper and outlines future work. 2. Agile Requirements Development AMs recommend a highly participative and iterative ap- proach to requirements development [10]. Initially, re- quirements are briefly documented, typically through user stories. Usually for user stories a high level user request is written on an index card or post-it note. Along with specific functionality required, other relevant in- formation such as story title, release date, order of prior- ity, author’s initials and time estimates to complete can also be included. During development, each story is used to provoke an in-depth discussion between developers and other stakeholders to examine each requirement in detail [11]. Initially, collectively, user stories identify a high level plan for each release of the project. The customer priori- tizes each story according to business value. Attention is then focused on the first release with a number of priori- tized stories used to identify the first short iteration. Typically this is a week or two in length [10]. Developers further divide the stories into tasks and estimate a time- frame to complete each task. It is expected that each story is considered to be a placeholder, indicating that an in-depth analysis will be con ducted during the iteration. User stories and their associated tasks are placed to- gether on a publicly-visible story board. The board fre- quently referred to as “the wall” by [12], is the main fo- cal point of the room. Developers choose a story to com- plete from the board and commit to this by signing their initials on the story card and taking it from the board for development. When the user story is complete, the de- veloper ticks the card and returns it to a new position on the story board. Alternatively, if the story is not fully complete, the card is considered to be still pending and is returned to the same position on the board. Complete stories become features of the system where they can be further developed in upcoming iterations. The story board provides a clear indication of what work has been done and what has yet to be completed. Stories placed with their tasks also allow developers to envisage dependencies, essentially providing a visual representation of the work plan to the team. The colour of a card can also be used to convey specific meaning and can indicate warning signs. Some examples from [12] showed: Green cards signified stories, white for tasks; Blue cards related to features for staff; Orange flags indicated incomplete acceptance tests; Pink cards desc ribed bugs. The positioning of the cards on the story board can also communicate specific meaning. The top three rows for instance in [13] contained recently completed stories. To the left of the board were scheduled stories and to the right were unscheduled stories. 2.1. The Customer Role A key role for successful requirements development within AMs is that of the customer, which differs from that expected in a traditional development project, for example with the waterfall approach the customer is in- volved at the beginning of a project and the relationship between the customer and the development te am th rou gh- hout the project is contractual, whereas AMs prefer the customer to be continuously involved for the duration of the project. However, a misconception with early AMs is that customer involvement was often reduced to a single on-site customer with little guidance provided on how to implement this role. In distinguishing between traditional and agile Re- quirements Engineering (RE) practice in industry, Cao & Ramesh found that the “inability to gain access to the customer and obtaining consensus among stakeholder groups” were the most common challenges experienced [14]. Martin et al. report eight practices that were used in successful projects to enable real customer involvement [15]. The authors illustrate the complexity of customer representation, identifying ten roles on a customer team, these were informally created with little prior guidance to support the customer role. Each person on the customer team negotiates with and represents a widely diverse group of stakeholders. Many authors have expressed the importance of hav- ing the appropriate and relevant stakeholders on board. In examining critical success factors in software develop- ment, Boehm and Turner found that the customer role should comprise of individuals who are Collaborative, Representative, Authorized, Committed and Knowl- edgeable (CRACK), deeming these crucial attributes stakeholder representatives should possess in imple- menting the customer role [16]. Hence, performing the customer role in agile projects is a challenging task, fre- quently taken for granted. 3. Agile Methods for HCS? McBryan et al. identify ten desirable characteristics an RE method should possess for HCS [5]. Table 1 summa- rizes these characteristics in column 1 with an indication of how AMs match these in column 2. Two ticks indicate that AMs comply fully with the characteristic, one tick indicates partial compliance and ‘x’ indicates no compli-  Investigating the Suitability of Agile Methods for Requirements Development of Home Care Systems Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 892 Table 1. HCS characteristics and agile methods compliancy mapping. Characteristics AMs Iterative development Prioritization Correlation with other processes Appropriate stakeholders Participatory elicitation Identification of conflict Resolution of conflict Retention & traceability Annotation Distributed elicitation ance with the characteristic. The following poin ts discuss the varying degrees of compliance between these. Iterative development: with AMs, short iterations of fully working software provide opportunities for con- tinuous stakeholder input. Perceived needs can be clari- fied and new ones emerge. As circumstances change re- quirements will evolve based on stakeholder input. This is a characteristic AMs are fully compliant with. Prioritisation of requirements: different stakeholders may need to be given different priorities depending on a variety of circumstances. Specifically in [5], the authors point out that in relation to particular features, if for in- stance, usability is an issue then the needs of the person in care may be the highest priority whereas care profes- sionals may have higher priority requirements if it is the case that the person concerned is a “risk to themselves or others” in the home environment. AMs are fully compli- ant with this characteristic as features can be prioritized at the beginning of each iteration. Correlation with other processes and work practices calls for immediate benefit from solutions required. This is entirely consistent with the agile approach which pro- motes the early delivery of high quality ‘working soft- ware’ to satisfy the customer’s business objective. Identification and Engagement of appropriate stake- holders is partially compliant as AMs recognize the need for this. Although this is promoted within AMs and nu- merous successes have been reported, difficulties have emerged in certain situations particularly when multiple stakeholders are involved. However, no generalized method as such can be applied here since realizing this depends on constraints and circumstances often unique to each situation. Participatory elicitation and negotiation requires thos e involved in a care network including the cared person to negotiate the suitability of a potential device or care ser- vice proposed. Essentially, an opportunity to demonstrate a candidate device or interaction mode to stakeholders in advance of decisions to be made is necessary. This char- acteristic is partially compliant as Active Stakeholder Participation (ASP) is encouraged in AMs but achieving this in practice remains problematic. Identification of conflict partially complies since AMs encourage conf lict to be aired as soon as possible but this is often challenging if relevant stakeholders are not ac- tively involved or, as is frequently reported, only identi- fied during the latter stages of development. Resolution of conflict partially complies, although the need to air and resolve conflict early is recognized, suc- cess here is again dependent on stakeholders’ active par- ticipation in the project. Retention and traceability of requirements is partially compliant since AMs only retain artefacts such as user stories for as long as they are deemed useful. Agile prac- titioners recommend questioning traceability in terms of time to complete and the re-examination of what value it brings to stakeholders. This is to ensure that while trace- ability may be needed, it must be applied in a timely manner. An option here is to employ an appropriate pro- ject management tool that does not detract from the overall effort required in developing and maintaining the software solution. Examples of available tools include Envision VIP 9 and PACE 3. Annotations to facilitate negotiation and traceability, is also partially compliant as story cards are often anno tated. However, it is likely that agile practitioners would inte- grate the annotation as a main part of the user story. In particular, this characteristic intends to add further con- text to a requirement. Distributed elicitation is a characteristic AMs are par- tially compliant with since although AMs prefer face to face communication, other means such as email and video conferencing are most often used for dispersed stakeholders. In addition to tools mentioned previously, other tools, particularly XPlanner and TargetProcess en- able distributed teams to communicate with geographi- cally dispersed stakeholders. Here, AMs are fully compliant with three characteris- tics of a desirable approach to requirements development in HCS. However, AMs show only partial compliance with the remaining seven characteristics in dicating future work needed to improve on these. 4. Conclusions and Further Work In summary, due to the expected increase in older popu- lations, the need to develop HCS is evident. Success in software systems heavily depends on accurately obtain-  Investigating the Suitability of Agile Methods for Requirements Development of Home Care Systems Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 893 ing requirements from stakeholders. It is also difficult to identify access, engage and support continuous negotia- tion of requirements amongst relevant stakeholders. De- spite the numerous elicitation techniques available, ac- commodating diversity amongst multiple stakeholder groups remains a key challenge. Suggestions made to improve on this include a new or adaptive approach to requirements development, However it is not entirely clear how this could be achieved. AMs may provide a solution but particularly, an important concern here is in effective implementation of the customer role. This paper compared the desirable characteristics for RE in HCS with agile methods and indicates that there is a close match. However, challenges still exist as AMs are only partially compliant with many of the remaining charac- teristics. Future work will investigate how this position can be further i mproved. REFERENCES [1] World Health Organization (WHO), “Public Health Impli- cations of Global Ageing,” 2010. http://www.who int/fea- tures/qa/42/en/index.html [2] S. Roberts, T. Basi, A. Drazin and J. Wherton, “Connec- tions: Mobility and Quality of Life for Older People in Rural Ireland” Intel Corporation, America, 2007. [3] Technology Research for Independent Living (TRIL) “Falls Prevention,” 2010. http://www.trilcentre.org/falls_ prevention/falls_prevention.474.html [4] M. R. McGee-Lennon, “Requirements Engineering for Home Care Technology,” Proceeding of the 26th Annual SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 2008, pp. 1439-1442. [5] T. McBryan, M. R. McGee-Lennon and P. Gray, “An Integrated Approach to Supporting Interaction Evolution in Home Care Systems,” Proceedings of the 1st interna- tional Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related To Assistive Environments, Athens, July 2008, pp. 1-8. [6] A. Davis, O. Dieste, A. Hickey, N. Juristo and A. M. Moreno, “Effectiveness of Requirements Elicitation Techniques: Empirical Results Derived from a Systematic Review,” Proceedings of 14th IEEE International Con- ference of Requirements Engineering, Minneapolis, Sep- tember 2006, pp. 179-188. [7] H. Van Vliet, Ed., “Software Engineering Principles and Practice,” John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, 2000. [8] B. Nuseibeh and S. Easterbrook, “Requirements Engi- neering: A Roadmap,” Proceedings of International Con- ference on Software Engineering, ACM Press, Limerick Ireland, 2000. [9] K. Beck, et al. “The Agile Manifesto,” 2001. http://www. agilealliance.com [10] S. W. Ambler, “Agile Modeling: Effective Practices for Extreme Programming and the Unified Process,” John Wiley & Sons Inc., Chichester, 2002. [11] D. Astels, G. Miller and N. Miroslav, “A Practical Guide to Extreme Programming,” Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2002. [12] H. Sharp, H. Robinson, J. Segal and D. Furniss, “The Role of Story Cards and the Wall in XP teams: A Distrib- uted Cognition Perspective,” Proceedings of Agile, IEEE Computer, Society Press, Washington, DC, 2006, pp. 65- 75. [13] W. Pietri, “An XP Team Room,” 2004. http://www.scis- sor .com/resources/teamroom [14] L. Cao and B. Ramesh, “Agile Requirements Engineering Practices: An Empirical Study,” Software, IEEE, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2008, pp. 60-67. [15] A. Martin, R. Biddle and J. Noble. “XP Customer Prac- tices: A Grounded Theory,” Proceedings of Agile Con- ference, agile, Chicago, August 2009, pp. 33-40. [16] B. W. Boehm and R. Turner, “Using Risk to Balance Agile and Plan-Driven Methods,” Computer, Vol. 36, No. 6, 2003, pp. 57-66. |