Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

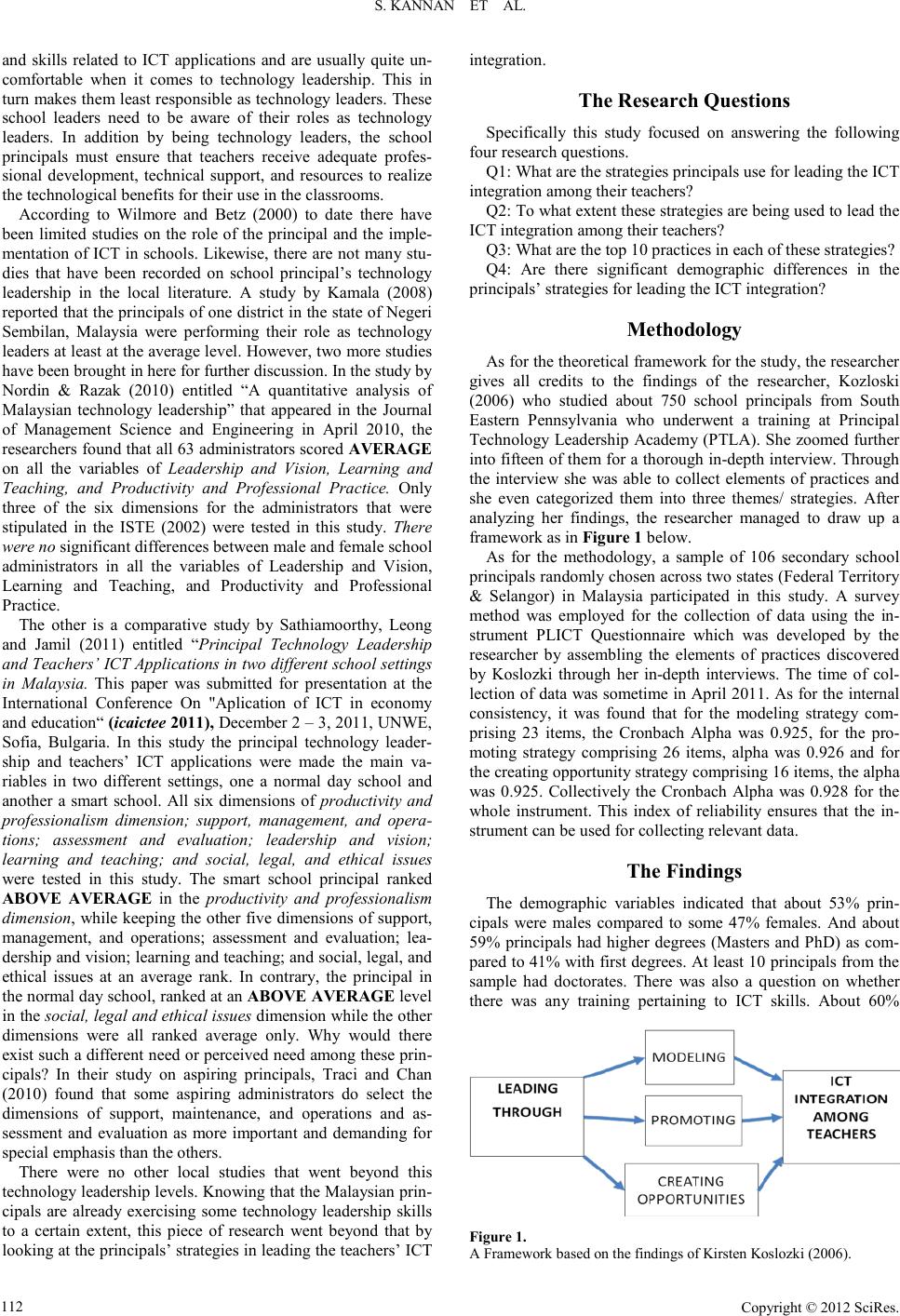

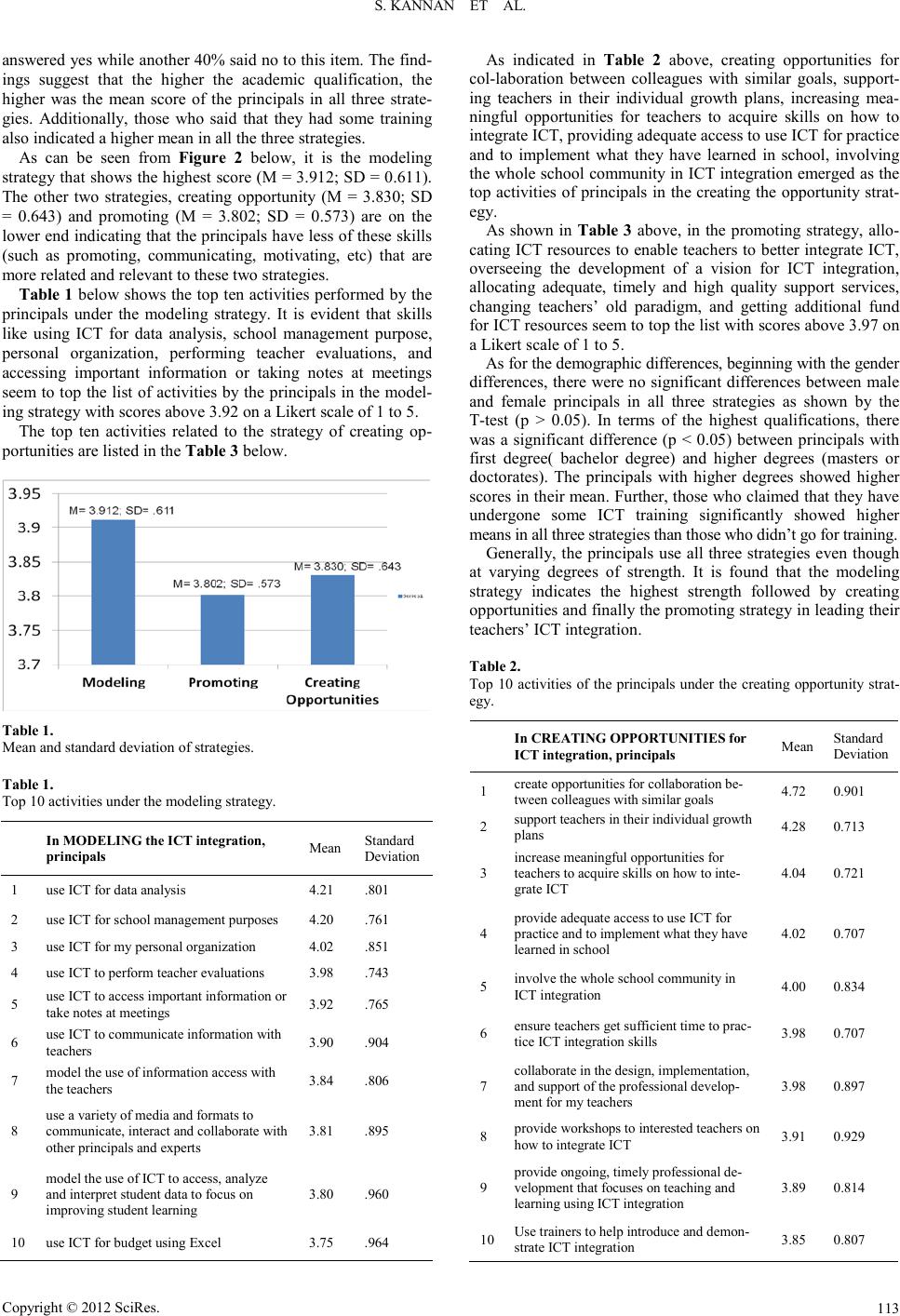

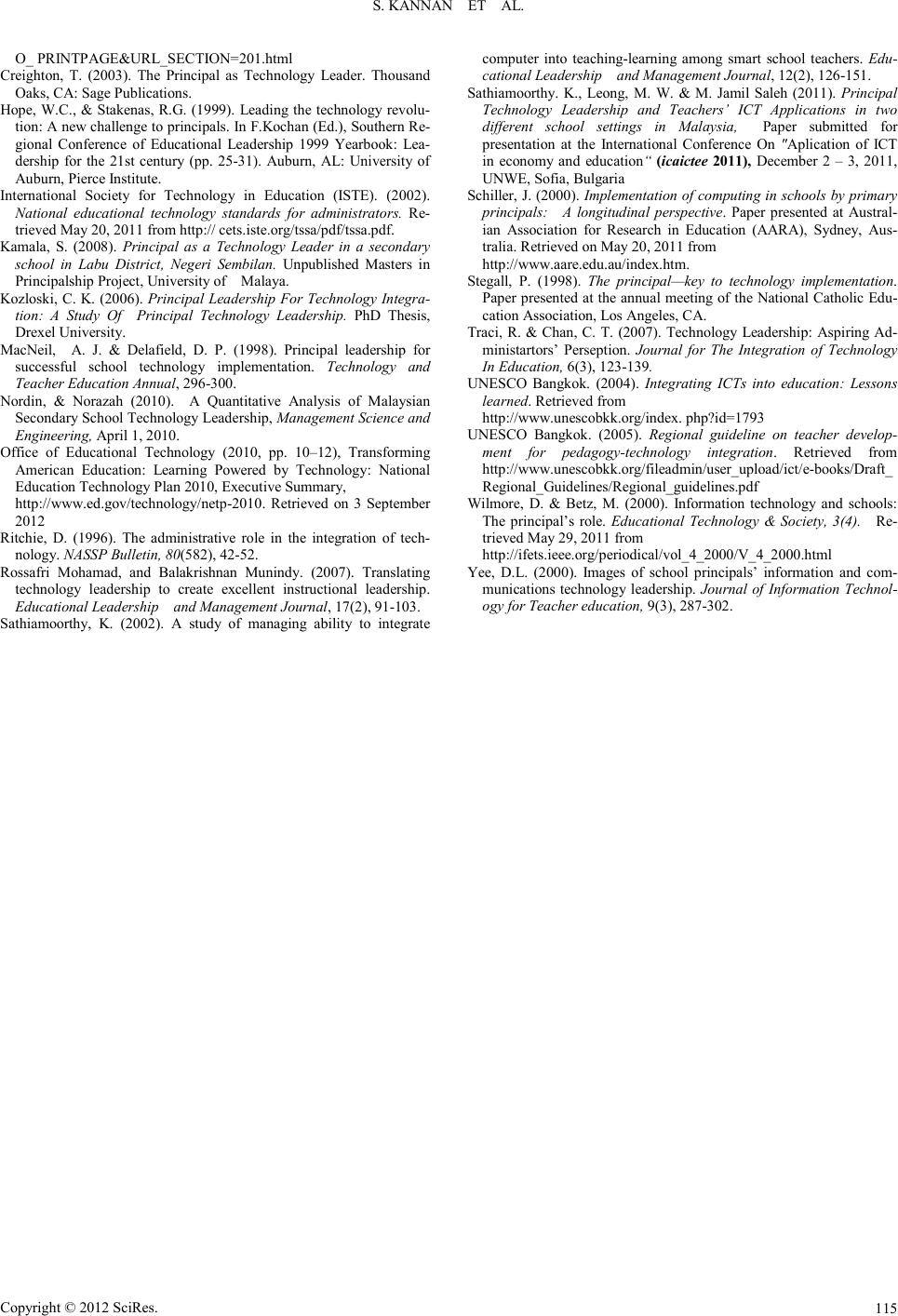

Creat ive Educati on 2012. Vol.3, Supplement, 111-115 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) DOI:10.4236/ce.2012.38b023 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 111 Principal’s Strategies for Leading ICT Integration: The Malaysian Perspective Sathiamoorthy Kannan, Sai lesh Shar ma, Zurai dah Abdull ah Institute of Educational Leadership, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Email: drsathia@um.edu.my, sharmuco@um.edu.my, zuraidahab@um.edu.my Received 20 1 2 This s tudy is the fi rst of its ki nd in the nati on to examine t he strat egies used by pr incipals in leading t he ICT integration among their teachers. It also attempted to study the extent to which these strategies are being used, the top ten practices in each of these strategies, and whether there exist demographic differ- ences in the use of the strategies. A survey method, using the Principal Leading ICT Integration Ques- tionnaire (PLICTQ), was employed to capture all the relevant information. A sample of 106 princi-pals from two nei ghbouri ng stat es in Malaysi a particip ated in this st udy. The findings indicat e that prin-cipals use all the three strategies (modeling, promoting and creating opportunities) but at varying degrees of str engths. The model ing i s f ound to be t he str ategy w ith t he high est de gree of str ength foll owed b y creat- ing opp ort uniti es, and fi nally pr omoting st rategy. As for the de mograp hic variab les, the f ind-ings i ndica te significant differences for the academic qualifications (first degree and post graduate) and the training (yes and no). However, gender differences were not significant in the analysis. This study suggests that the higher the academic qualifica tion, the bett er the p rincipals i n understandi ng and show-ing good tech- nology lea der ship . Those w ho said tha t they had s ome trai ning indi ca ted a higher mean in a ll thr ee strate- gies. One important suggestion that can be drawn from here is that if these principals are provided with the appropriate professional development in technology leadership, then they can really excel to even higher levels in exhibi ting ICT lea dership for their teachers. Key words: Principals’ Strategies; ICT Integrati on; Leading; M odeling; Creat ing Opportunity; Promoti ng Introduction Many researches on technology best practices for teaching and learning indicate that principals are a key to sustained technology integration in any school building. And that prin- cipals express a strong interest in developing instructional lea- dership skills for the integration of technology into teaching and learning. In her research on principals’ leadership and ICT integration, Yee (2000) found that the schools that integrated ICT in the most constructive way were those where the princi- pals shared an unwavering vision that ICT had the potential to improve student learning. These principals also portrayed pas- sionate commitment to providing professional development to enhance their teachers’ ICT skills. Schiller (2000), talks about the key roles that the principals need to play such as highlight- ing supporting technology, and facilitating change and inter- vention strategies in the teaching and learning process. Schools with the highest technology use shared the characteristic of a strong, enthusiastic principals supporting their convictions about technology by allocating resources and scheduling pro- fessional development in ICT for their teachers (Stegall, 1998). Effective principals need to be actively involved with technol- ogy, including modeling the technology use and helping to implement ongoing curriculum-integrated technology staff development. While discussing the role of the administrator in technology integration, Ritchie (1996) states that principals must mobilize their teachers to create a technology culture. Indeed, Hope and Stakenas (1999) suggested three primary roles for the principal as technology leaders for better ICT inte- gration among their teachers: role model, instructional leader, and visionary. In order for successful implementation of ICT applications among teach ers, Macneil and Delafield (1998) commented that principals need to use their existing resources wisely and crea- tively. They ought to “think outside the box’ and they must think in a fluid environment. In addition, they need to establish a vision for the school, a context for technology in the school to empower teachers and help students become more technology literat e (Brockmeier, S ermon, & Hope, 20 05). In a study of the correlation between teachers’ perceptions of principal’s tech- nology leadership and the integration of educational technology, Rogers (2000) found that teachers who had positive perceptions about the principal’s role in supporting the integration of tech- nology were more likely to integrate t echnology themselves. The Setting Malaysia is a fast developing nation and aspires to be a de- veloped nation by 2020. It is actually investing a lot of money in developing the infra structure as well as in building the teachers’ skills in ICT because it believes that with ICT as an enabler in the classroom instruction, it can enhance the student learning and finally achieve its ultimate goal of being a devel- oped nation by 2020. However, many of the country’s princip- als are not fully aware of their role as technology leaders. In some of the studies that were conducted in the nation, it could be seen that they were practicing only some of the technology leadership skills. They are probably doing it quite unknowingly. Rossafri and Balakrishnan (2007), noted that most of these school leaders are at the lower end in terms of the knowledge  S. KANNAN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 112 and skills related to ICT applications and are usually quite un- comfortable when it comes to technology leadership. This in turn makes them least responsible as technology leaders. These school leaders need to be aware of their roles as technology leaders. In addition by being technology leaders, the school principals must ensure that teachers receive adequate profes- sional development, technical support, and resources to realize the technological benefits for t heir use i n the classrooms. According to Wilmore and Betz (2000) to date there have been limited studies on the role of the principal and the imple- mentation of ICT in schools. Likewise, there are not many stu- dies that have been recorded on school principal’s technology leadership in the local literature. A study by Kamala (2008) reported that the principals of one district in the state of Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia were performing their role as technology leaders at least at th e average le vel. However, two more studies have been brought in here for further discussion. In the study by Nordin & Razak (2010) entitled “A quantitative analysis of Malaysian technology leadership” that appeared in the Journal of Management Science and Engineering in April 2010, the researchers found that all 63 administrators scored AVERAGE on all the variables of Leadership and Vision, Learning and Teaching, and Productivity and Professional Practice. Only three of the six dimensions for the administrators that were stipulated in the ISTE (2002) were tested in this study. There were no sign ificant differences bet ween male and female school administrators in all the variables of Leadership and Vision, Learning and Teaching, and Productivity and Professional Pract i ce. The other is a comparative study by Sathiamoorthy, Leong and Jamil (2011) entitled “Principal Technology Leadership and Teachers’ ICT Applications in two different school settings in Malaysia. This paper was submitted for presentation at the International Conference On "Aplication of ICT in economy and edu cation “ (icaictee 2011), December 2 – 3, 2011, UNWE, Sofia, Bulgaria. In this study the principal technology leader- ship and teachers’ ICT applications were made the main va- riables in two different settings, one a normal day school and another a smart school. All six dimensions of productivity and professionalism dimension; support, management, and opera- tions; assessment and evaluation; leadership and vision; learning and teaching; and social, legal, and ethical issues were tested in this study. The smart school principal ranked ABOVE AVERAGE in the productivity and professionalism dimension, while keeping the other five dimensions of support, management, and operations; assessment and evaluation; lea- dership and vision; learning an d teaching; an d soci al, legal, an d ethical issues at an average rank. In contrary, the principal in the normal day school, ranked at an ABOVE AVERAGE level in the social, legal and ethical issues dimension while the other dimensions were all ranked average only. Why would there exist such a different need or perceived n eed among thes e prin- cipals? In their study on aspiring principals, Traci and Chan (2010) found that some aspiring administrators do select the dimensions of support, maintenance, and operations and as- sessment and evaluation as more important and demanding for special emphasis than the others. There were no other local studies that went beyond this technology leadership levels. Knowing that the Malaysian prin- cipals are already exercising some technology leadership skills to a certain extent, this piece of research went beyond that by loo king at the princi pals’ strat egies in leadi ng the teach ers’ ICT integration. The Research Ques tion s Specifically this study focused on answering the following four research questions. Q1: What ar e the strategies principals use for leading the ICT integrat ion among their teachers? Q2: To what extent th ese str ategies are b ein g u sed to lead the ICT integration amon g t heir teacher s ? Q3: What ar e the top 10 practices in each of these strategies? Q4: Are there significant demographic differences in the principals’ strategies for leading the ICT integration? Methodology As for t he t heo reti cal fra mewor k for th e stu dy, th e rese arch er gives all credits to the findings of the researcher, Kozloski (2006) who studied about 750 school principals from South Eastern Pennsylvania who underwent a training at Principal Technology Leadership Academy (PTLA). She zoomed further into fifteen of them for a thorough in-depth interview. Through the interview she was able to collect elements of practices and she even categorized them into three themes/ strategies. After analyzing her findings, the researcher managed to draw up a framework as i n Figure 1 below. As for the methodology, a sample of 106 secondary school prin cipals ran domly chosen across two s tates (Fed eral Terr itor y & Selangor) in Malaysia participated in this study. A survey method was employed for the collection of data using the in- strument PLICT Questionnaire which was developed by the researcher by assembling the elements of practices discovered by Koslozki through her in-depth interviews. The time of col- lection of data was sometime in April 2011. As for the internal consistency, it was found that for the modeling strategy com- prising 23 items, the Cronbach Alpha was 0.925, for the pro- moting strategy comprising 26 items, alpha was 0.926 and for the creating opportunity strategy comprising 16 items, the alpha was 0.925. Collectively the Cronbach Alpha was 0.928 for the whole instrument. This index of reliability ensures that the in- strument can be used for collect ing relevant data. The Findings The demographic variables indicated that about 53% prin- cipals were males compared to some 47% females. And about 59% principals had higher degrees (Masters and PhD) as com- pared to 41% with first degrees. At least 10 principals from the sample had doctorates. There was also a question on whether there was any training pertaining to ICT skills. About 60% Figure 1. A Framework based on the findings of Kirsten Koslozki (2006).  S. KANNAN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 113 answered yes while another 40% said no to this item. The find- ings suggest that the higher the academic qualification, the higher was the mean score of the principals in all three strate- gies. Additionally, those who said that they had some training also indicated a h igher mean in all the three strategies. As can be seen from Figure 2 below, it is the modeling strategy that shows the highest score (M = 3.912; SD = 0.611). The other two strategies, creating opportunity (M = 3.830; SD = 0.643) and promoting (M = 3.802; SD = 0.573) are on the lower end indicating that the principals have less of these skills (such as promoting, communicating, motivating, etc) that are more related an d relevant t o these two strat egi es. Table 1 below shows the top ten activities performed by the principals under the modeling strategy. It is evident that skills like using ICT for data analysis, school management purpose, personal organization, performing teacher evaluations, and accessing important information or taking notes at meetings seem to top the list of activities by the principals in the model- ing strategy with scores above 3.92 on a Likert scale of 1 to 5. The top ten activities related to the strategy of creating op- portunities are listed in the Table 3 below. Tabl e 1. Mean and standard devi ation of strategies. Table 1. Top 10 activities under the modeling strategy. In MODELING the ICT integrat ion, principals Mean Standard Deviation 1 use ICT for data analysis 4.21 .801 2 use ICT for school manage ment purposes 4.20 . 761 3 use ICT for my personal or ganization 4.0 2 .851 4 use ICT to perform teache r evaluations 3 .98 .743 5 use ICT to access importan t informati on or take notes at meetings 3.92 .765 6 use ICT to communicate information with te acher s 3.90 .904 7 model the use of information access with the teachers 3.84 .806 8 use a variety of media and forma ts to communicate, interact and collaborate with other principals and experts 3.81 .895 9 model the use of ICT to access, analyze and interpret studen t data to focus on improving student learning 3.80 .960 10 use ICT for budget using Exce l 3.75 .964 As indicated in Table 2 above, creating opportunities for col-laboration between colleagues with similar goals, support- ing teachers in their individual growth plans, increasing mea- ningful opportunities for teachers to acquire skills on how to integrat e ICT, providing adequate access to u s e I CT for practice and to implement what they have learned in school, involving the whole school community in ICT integration emerged as the top activities of principals in the creating the opportunity strat- egy. As shown in Table 3 above, in the promoting strategy, allo- cating ICT resources to enable teachers t o better in tegrate ICT, overseeing the development of a vision for ICT integration, allocating adequate, timely and high quality support services, changing teachers’ old paradigm, and getting additional fund for ICT resources seem to top the list with scores above 3.97 on a Likert scale of 1 to 5. As for the demographic differences, beginning with the gender differences, there were no significant di fferences bet ween male and female principals in all three strategies as shown by the T-test (p > 0.05). In terms of the highest qualifications, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) between principals with first degree( bachelor degree) and higher degrees (masters or doctorates). The principals with higher degrees showed higher scores in t heir mean. Further , those who claimed that they have undergone some ICT training significantly showed higher mea ns in a l l thre e s trat eg ies tha n those who didn’t g o for training. Generall y, the principals use all three strategies even though at varying degrees of strength. It is found that the modeling strategy indicates the highest strength followed by creating opportunities and finally the promoting strategy in leading their teachers’ ICT integration. Table 2. Top 10 activities of the principals under the creating opportunity strat- egy. In CREATING OPPORTUNITIES for ICT integration, principals Mean Standard Deviation 1 create opportunities for collaboration be- tween colleagues with simi lar goals 4.72 0.901 2 support te achers in their individual gr owth plans 4.28 0.713 3 increas e meaningful oppor tunities for teachers to acquire skills on how to inte- grate ICT 4.04 0.721 4 provide adequate access to use ICT for practice and to implement what they have lear ned in sc ho ol 4.02 0.707 5 involve the whole school com munity in ICT integration 4.00 0.834 6 ensu r e teache rs get sufficient t ime to pra c- tice ICT integration skills 3 .98 0.707 7 collaborate in the design, implementation, and support of the professional develop- men t for my teachers 3.98 0.897 8 provide workshops to inte rested teachers on how to integ rate ICT 3.91 0.929 9 provide ongoing, timely professional de- velopment that focus es on teaching and learning using ICT integration 3.89 0.814 10 Use trainers to help introduce and demon- strate ICT integrat ion 3.85 0.807  S. KANNAN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 114 Tabl e 3. Top 10 activities of the principals under the promoting strategy. In PR OMOTING IC T inte gration, principals Mea n Standard Deviation 1 allocate ICT resourc es to enable teachers to better integrat e ICT 4.05 .821 2 oversee the developm ent of a vision for ICT integration by working w it h s ta ff/ICT committee 4.03 .749 3 allocate adequate , timely and high quality support services for ICT integration 4.01 .845 4 change teachers’ old pa radigm 3.99 .737 5 get additional fund for ICT resources 3.97 .668 6 provide additional hardware such as inter- active whiteboard & LCD projector 3.97 .845 7 assist teachers in using ICT to access, analyze and interpret student performance 3.95 .809 8 obtain additional ha rdware for ICT int egra- tio n p urpose s 3.94 .645 9 facilitate ICT integration for teach ers 3.94 .741 10 use te chnology to change and reinforce new communication meth od (e.g. e mail) 3.92 .880 Discussion and Conclusion Though the study finds that it was the modeling strategy that indicated a higher intensity in terms of the mean score, almost all the skills that are listed under this modeling strategy resem- ble the basic technological skills usually utilized by the prin- cipals. For example, using ICT for data analysis, school man- agement purpose, personal organization, and accessing impor- tant information or taking notes at meetings recall the basic competencies of the principals in relation to ICT usage. Koz- loski (2006) found that many of the principals she interviewed advocate that modeling is one of the best ways to show teachers to follow their lead in technology, though in some cases the teachers do not have the same perspective as the principals do in their use of ICT applications. Hope and Stakenas (1999) too cont ent ed that one o f th e three p rimary rol es for t he p rin cipal as technology leaders for better ICT integration among their teachers is role modeling. Further, the Office of Educational Technology (2010) describes the following as the main tasks of technology leadership: modeling the use of technology, sup- porting technology use in the school, engaging in professional development activities that focus on technology and integration of technology in student learning activities, securing resources to support technology use and integration in the school, and advocating for technology use that supports student learning. In fact, creating opportunities and promoting strategies are also equally important as they allow the principals to provide teach- ers with access to technology resources within the school, have them work with colleagues in technology- supported instruc- tional design projects, give them time and recognition for their participation (UNESCO Bangkok, 2004; 2005). Teachers need to be given time to participate in training activities and they need to be given time to try out what they have learned in the classroo m. Hence, the sch ool administrators’ lower intensity in these two strategies is an indication that there is a strong need for related training and exposure to these principals in per- forming their role as better technology leaders in their organi- zations. Integrating ICT requires teachers to possess the right skills and attitude for doing that (Carlson and Gadio, 2002). And very often, t he teachers are foun d to be relating t heir performance to the leadership of their schools. When they perceive a good leadership from their principals, they seem to be actively in- volved in the programmes that are developed by the leadership to enhance their ICT skills. In other words, they try to imitate their role models who can be their own principals (Sathiamoorthy, 2002). If only school leaders realize their role as technology leaders and show better leadership and vision for technology, they can inspire their teachers in the quest for more knowledge and skills and be able to ensure complete and sustained implementation of the vision (Creighton, 2003). At the same time principals can provide the alignment between technology and instructional practices, and some real time collaboration for teachers in the area of technology integration, and just in time professional development (Yee, 2000). And it is highly possible to talk about real technology leadership when these principals show high competency in the leadership and vision dimension (Banoglu, 2011). The integration of ICT into teaching and learning seems one worthy effort by the Ministry of Education, Malaysia (MOE) in making the integration of ICT a norm in every school if not most schools. Continuous efforts towards that are being taken to enhance teachers’ ICT skills in all schools in the Malaysian context. In line with that, it would be fruitful for the Ministry of Education and its training arms if they become more aware of the need to prepare and equip the existing principals to be better technology leaders with strong skills to use strategies such as modelling, creating opportunity and promoting to foster and lead b etter ICT integration among their teach ers. Many school leaders are uncomfortable providing leadership in technology areas. They may be uncertain about implement- ing effective technology leadership strategies in ways that will improve learning. They may even believe that their own know- ledge of technology is inadequate to make meaningful recom- mendations. However, among such a group of leaders, this study has brought to the surface that there are principals who claim that they have undergone some training, may be just technological skills training and not technology leadership skills per se, who sho w that they have an advant age in empl oy- ing the strategies. Based on the findings of the study, it can be assumed further that by providing the appropriate technology leadership skills to these principals, we could generate a lot more real technology lead ers that can easily lead teach ers’ ICT integration for better student learning. REFERENCES Banoglu, K. (2011). School principals’ technology leadership compe- tenc y and technolog y coordinat orship. Edu cational Scie nces: Theor y & Pr at ice, 11 (1), 208 -213. Brockmeier, L.L., Sermon, J.M., & Hope, W.C. (2005). Principal’s relationship with computer technology. NASSP Bulletin, 89 (643), 45-63. Carlson, S. and C.T. Gadio. (2002). Teacher professional development in the use of technology. In W.D. Haddad and A. Draxler (Eds), Technologies for education: Potentials, parameters, and prospects. Paris and Washington, DC: UNESCO and the Academy for Educa- tional Development. Retrieved 10 August 2011 from http://portal.unesco.or g/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=22984&UR L_DO=D  S. KANNAN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 115 O_ PRINTPAGE&URL_SECTION=201.html Creighton, T. (2003). The Principal as Technology Leader. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Hope, W.C., & Stakenas, R.G. (1999). Leading the technology revolu- tion: A new challenge to principals. In F.Kochan (Ed.), Southern Re- gional Conference of Educational Leadership 1999 Yearbook: Lea- dership for the 21st century (pp. 25-31). Auburn, AL: University of Auburn, Pierce Institute. International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). (2002). National educational technology standards for administrators. Re- trieved May 20, 2 01 1 fr o m ht tp: // cets.is te .org/tssa/pdf/tssa.pdf. Kamala, S. (2008). Principal as a Technology Leader in a secondary school in Labu District, Negeri Sembilan. Unpublished Masters in Principalship Project, University of Malaya. Kozloski, C. K. (2006). Principal Leadership For Technology Integra- tion: A Study Of Principal Technology Leadership. PhD Thesis, Drexel University. MacNeil, A. J. & Delafield, D. P. (1998). Principal leadership for successful school technology implementation. Technology and Teacher Education Annual, 296-300. Nordin, & Norazah (2010). A Quantitative Analysis of Malaysian Secondary School Technology Leadership, Management Science and Engineering, April 1, 2010. Office of Educational Technology (2010, pp. 10–12), Transforming American Education: Learning Powered by Technology: National Educ ation Techn ology Plan 2010, Executive Summ ary, http://www.ed.gov/technology/netp-2010. Retrieved on 3 September 2012 Ritchie, D. (1996). The administrative role in the integration of tech- nology. NASSP Bulletin, 80(582), 42-5 2. Rossafri Mohamad, and Balakrishnan Munindy. (2007). Translating technology leadership to create excellent instructional leadership. Educational Leadership and Management Journal, 17(2), 91-103. Sathiamoorthy, K. (2002). A study of managing ability to integrate computer into teaching-learning among smart school teachers. Edu- cati onal Lea d er ship and Man a gement J ournal, 12(2), 126-151. Sathiamoorthy. K., Leong, M. W. & M. Jamil Saleh (2011). Principal Technology Leadership and Teachers’ ICT Applications in two different school settings in Malaysia, Paper submitted for presentation at the International Conference On "Aplication of ICT in economy and education“ (icaictee 2011 ) , December 2 – 3, 2011, UNWE, Sofia, Bulgaria Sch iller, J. ( 2000). Impl ementation of computing i n sch ool s by prim ary principals: A longitudinal perspective. Paper presented at Austral- ian Association for Research in Education (AARA), Sydney, Aus- tralia. Retrieved on May 20, 2011 fr om http://www.aare.edu.au/index.htm. Stegall, P. (1998). The principal—key to technology implementation. Pap er presen ted at the an nual m eeting of th e Nationa l Catholi c Edu- cation Association, Los Angeles, CA. Traci, R. & Chan, C. T. (2007). Technology Leadership: Aspiring Ad- ministartors’ Perseption. Journal for The Integration of Technology In Educ ation, 6(3) , 123-139. UNESCO Bangkok. (2004). Integrating ICTs into education: Lessons learned. Retrieved from http://www.unescobkk.org/index. php?id=1793 UNESCO Bangkok. (2005). Regional guideline on teacher develop- ment for pedagogy-technology integration. Retrieved from http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ict/e-books/ Dr aft_ Regional_Guidelines/Regional_guidelines.pdf Wilmore, D. & Betz, M. (2000). Information technology and schools: The principal’s role. Educational Technology & Society, 3(4). Re- trieved May 29, 2011 f rom http://ifets .ieee.org/periodi ca l/vol_4_2000 /V_4_2000.html Yee, D.L. (2000). Images of school principals’ information and com- munica tions techn ology leadersh ip. Journal of Information Technol- ogy for Teac her education, 9(3), 287 -302. |