Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 19-24 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2013.31004 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 19 Workplace Identities of Women in the US Labor Market Dina Banerjee Department of Sociology, Anthropology Shippensburg University, Shippensburg, USA Email: dbanerjee@ship.edu Received November 13th, 2012; revised December 12th, 2012; accepted December 23rd, 2012 In this paper, I examine the effects of gender and race/ethnicity on American workers’ workplace identi- ties. Literature on gender, work, and occupation suggests that gender and race are significant predictors of workers’ workplace identities. Literature also posits that self-perceived competency and reflected ap- praisals from others in workplaces also contribute considerably to workers’ workplace identities. How- ever, there exists hardly any empirical study that explores the impacts of gender, race, workers’ self-per- ceived competency, and their reflected appraisals altogether on their workplace identities. That is what I accomplished in this study. Deriving the data from the National Study of Changing Workforce (NSCW: 2008) I ask: 1) Do women and men workers in America differ in their perceptions of workplace identities; 2) Do non-white and white workers in America differ in their perceptions of workplace identities; and 3) Do gender and race of the workers impact their workplace identities when self-perceived competency and reflected appraisals enter the equation? Analyses are based on quantitative methods. Results show that workers’ self-perceived competency and their reflected appraisals are more significant predictors of their workplace identities than gender or race. Keywords: Gender; Identity; Workplace; Labor Market Introduction Workplace identities have drawn attention of the researchers on gender, work, and occupation since the advent of women’s movements in the US Workers’ workplace identities have been studied with regards to complex workplace cultures (Kohn & Schooler, 1973); occupational status, and industries (Tharenou & Harker, 1982); work autonomy (Mortimer & Lorence, 1979); decision making abilities within workplace (Staples, Schwalbe, & Gecas, 1984); relationships with coworkers and supervisors (Gardell, 1971); and relationships supervisors and managers (Hackman & Lawler, 1971)1. Scholarship on gender, work, and occupation describes work- place identity as the extent to which workers find their jobs meaningful with regards to their skills, talents, and capabilities (French & Caplan, 1972). This concept also refers to the posi- tive feeling that workers acquire in their workplaces by doing their jobs right and in an ethical way, and also by perceiving themselves as important members of the workforce (Kohn and Schooler, 1973; Staples, Schwalbe, & Gecas, 1984). Workplace identity is also defined as workers’ decision making capabilities in their work settings (Schwalbe & Gecas, 1984). Power of de- cision making of the workers may range from decisions regar- ding what to do on the job to when the job gets done (Schwalbe & Gecas, 1984; Gray-Little & Hafdahl, 2000). Additionally, workplace identity can also refer to workers’ feelings about proper utilization of their skills and talents as well as their loyalty towards their employers (Kohn & Schoo- ler, 1973; Staples, Schwalbe, & Gecas, 1984). Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000) suggest that workers aspire to have stronger workplace identities because that motivates them to perform their tasks more efficiently. This aspiration is found irrespective of gender and race/ethnicity of the workers. A number of empirical studies have addressed the impacts of gender or race/ethnicity on workplace identities of American workers (Schwalbe, Gecas, & Baxter, 1986; Schwalbe, 1988). However, to the best of my knowledge, there is hardly any study that examines the influences of both gender and race/ ethnicity on workplace identity. In this paper, I do so by using a national-level dataset and conducting rigorous quantitative ana- lyses. Literature on gender, work, and occupation that focuses on workers’ workplace identities presents two specific predic- tors of identity (apart from gender and race/ethnicity): self- perceived competence of workers, and reflected appraisals of others (Schwalbe, 1988; Twenge & Crocker, 2002). Yet, self- perceived competence and reflected appraisals together have hardly been taken into consideration by the empirical literature on workplace identity with regards to gender and race/ethnicity. Therefore, in this study, I explore the impacts of gender, race/ ethnicity, self-perceived competence, and reflected appraisals together on workplace identities of workers. This is because all of these factors are important in determining positive workplace identities of workers which in turn increases their efficiency within workplaces (Schwalbe, 1988; Twenge & Crocker, 2002). Deriving the data from the National Study of Changing Workforce (NSCW: 2008)—a nationally representative dateset, I ask: 1) Do women and men workers in America differ in their perceptions of workplace identities; 2) Do non-white and white workers in America differ in their perceptions of workplace identities; and 3) Do gender and race/ethnicity of the workers impact their workplace identities when self-perceived compe- tence of workers, and reflected appraisals of others enter the equation? 1In the literature on gender, work, and occupation, the concepts of “work- place identity,” “self-worth,” and “self-esteem” are often used interchangea- bly. This study intends to extend the literature on gender that fo- cuses on the work-related well-being of the workers by explor-  D. BANERJEE ing workplace identities of American workers. In this study, I use a national-level dataset to conduct rigorous quantitative analyses. Therefore, it is also an attempt to contribute to the empirical literature on gender, work, and occupation that deals with worker’s identities. The paper is organized into four spe- cific sections. The first section presents an overview of the so- ciological and social psychological literature on gender, work, and occupation that highlights workers’ identities. In the second section, I present the details of the data and methods I use to analyze the data. Findings are presented in the third section. Finally, in the conclusion section I interpret the findings in terms of workers’ self-perceived competences and reflected appraisals by others. Review of Literature Workplace identity is viewed as the extent to which workers find their jobs meaningful with regards to their skills, talents, and capabilities (French & Caplan, 1972). Additionally, it also refers to the positive feeling that workers derive in their work- places by doing right things in an ethical way, and also by iden- tifying themselves as imperative members of the workforce (Kohn & Schooler, 1973; Staples, Schwalbe, & Gecas, 1984). Workplace identity is also described as workers’ decision mak- ing abilities (Schwalbe & Gecas, 1984). Decision making capa- bilities of the workers may range from decisions regarding what to do on the job to when the job gets done (Schwalbe & Gecas, 1984; Gray-Little & Hafdahl, 2000). Again, workplace identity can also refer to workers’ perceptions about suitable application of their skills and experiences as well as their faithfulness to- wards their employers (Kohn & Schooler, 1973; Staples, Sch- walbe, & Gecas, 1984). Race/ethnicity and workplace identity of workers have been studied in a number of ways by researchers on gender, work, and occupation (Twenge & Crocker, 2002). Most of the studies suggest that being non-white is associated with weaker work- place identities as compared to being white (Adam, 1978; Pet- tigrew, 1978; Simmons, 1978). However, current research re- veals just the opposite (Scott, 1997). Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000) studied black, white and Hispanic people and found comparable levels of perceived identity in their younger years. Moreover, Blacks had stronger sense of identities than whites as young adults. Scholars have explored the race/ethnic variances on workers’ workplace identities from 2 specific conceptual ideas: self-per- ceived competence of workers, and reflected appraisals of others (Schwalbe, 1988; Twenge & Crocker, 2002). Self-perceived competence of the workers is defined by how workers view themselves in terms of their worth in the labor market (Twenge and Crocker, 2002). Factors like education, occupational status, work-family conflicts, workplace autonomy, and workplace re- wards are considered to be the indicators of self-perceived competency. That is, workers often assess their own perform- ances on the basis of these given indicators (Twenge & Croc- ker, 2002). Reflected appraisals of others determine the degree to which workers see themselves as valued by other people in their work- places (co-workers and supervisors) (Twenge & Crocker, 2002). Twenge and Crocker (2002) suggest that reflected appraisals are often manifested via the supports that workers receive from their workplaces, coworkers, and supervisors. And it also in- cludes whether or not the workers think they are discriminated in their work settings for any reason (Bourguignon, Seron, Yz- erbyt, & Herman, 2006). An interesting meta-analysis shows that Black people derive stronger sense of identities from self-perceived competencies whereas whites derive the same from reflected appraisals of others (Oyserman, Coon, & Kem- melmeier, 2002). The aforementioned conceptual ideas can also be used to understand the dynamics of gender differences as associated with workplace identities of workers. With regards to the pre- dictors of self-identity, Schwalbe and Staples (1991), found that women attached greater importance to their reflected appraisals than did men, and that there was no gender variances for self- perceived competence. Another study (Schwalbe et al., 1986) found that in the workplace, women workers reflected their self-perceived competence to be a more powerful source of their workplace identity than did men. In terms of workers’ workplace identities, previous studies did not find considerable differences between women and men (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974; Whitley, 1983; Wylie, 1979). Sim- mons and Blyth (1987) found that young women’s identities were more dependent on peer-based appraisals than those of young men. Interestingly, another study of middle-aged (58 - 64 years) working women and men did not find any statistically significant difference in their self-reflected identities (Reitzes & Mutran, 1994). Both female and male workers connected their higher levels of self-worth with their self-perceived compe- tences (Reitzes & Mutran, 1994). Empirical scholarship on gender, work, and occupation pays much importance to gender and race/ethnicity as key factors for workplace identity of the workers. Thus, an intersectional ap- proach of gender and race/ethnicity will enhance the understand- ing of workplace identity of the workers. Moreover, exploring the impacts of self-perceived competence and reflected ap- praisal would provide a comprehensive perspective on workers’ workplace identity. This is what I have tried to accomplish in this paper. Along with gender, and race/ethnicity, workers’ self- perceived competencies and reflected appraisals by others, I also examine the influence of workers’ individual characteris- tics of family life, following the work of Hughes and Demo (1989). Data and Methods Data Data for this study are derived from The National Study of Changing Workforce (NSCW: 2008), which was conducted by the Family and Work Institute. The NSCW is a nationally rep- resentative sample of workers across all workplaces in the US. A total of 3502 interviews were completed with a nationwide cross-section of employed adults. Interviews were conducted by using the computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) sys- tem. Calls were made to a stratified (by region) un-clustered random probability sample generated by random-digit-dial me- thods. Sample eligibility was limited to the workers who 1) worked at a paid job or operated an income-producing business; 2) were 18 years or older; 3) were in the civilian labor force; 4) resided in the contiguous 48 states; and 5) lived in a non-institutional residence (household with a telephone). In households with more than one eligible person, one was randomly selected to be interviewed. Although interviewing began in 2007, 88% of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 20  D. BANERJEE interviews were completed in 2008. Thus, this survey is refer- red to as the 2008 NSCW. Of the total 42,000 telephone numbers called, 24,115 were found to be non-residential or non-working numbers and 6970 were determined to be ineligible residences (1389 because no one spoke English or Spanish well enough to be interviewed). Of the remaining telephone numbers, 3547 were determined to represent eligible households, and interviews were completed between November 2007 and April 2008 for 3502 of these—a completion rate of 99%. However, eligibility or ineligibility could not be determined in the remaining 7368 cases. This study focuses on workplace identities of salaried workers ac- counting for gender and race. The total number of salaried male workers in the sample is 1424 and that of female workers is 1345. Also, there are 2233 white and 505 non-white salaried workers. Measurement Dependent Variable Workplace identity: This variable is an index of 8 items. Six of them are: “I have the freedom to decide what I do on my job,” “It is basically my own responsibility to decide how my job gets done,” “I have a lot of say about what happens on my job,” “The work I do is meaningful to me,” “My job lets me use my skills and abilities,” “I feel I am really a part of the group of people I work with.” The responses are: strongly disagree (1); somewhat disagree (2); somewhat agree (3); and strongly agree (4). The 7th item is: “On my job, I have to do some things that really go against my conscience. Response categories are: strongly agree (1); somewhat agree (2); somewhat disagree (3); and strongly disagree (4). The final item asked, “how loyal do you consider yourself to your current employer?” Responses are: not loyal at all (1); not very loyal (2); somewhat loyal (3); and very loyal (4). Alpha for this variable is 0.72. Independent Variables: De mogr aphic s Gender is a dummy variable that is based on the question: “Please excuse me, but I have to ask whether you are a man or woman.” Here “female” is coded as 1. Race is also a dummy variable with “white” coded as 1. The variable is measured by the question: “What is your race?” Response categories are: white (1); black or African American (2); native American or Alaskan native (3); Asian, Pacific Is- lander, or Indian (4); other, including mixed (5). All non-white respondents are grouped together because there are too few from any one category to analyze separately. Partnered family is a dummy variable: “Are you presently married, remarried, living with someone as a couple, single and never married, divorced, widowed, or separated?” The first three categories are coded as 1. Parent to any children is also a dummy variable. It is meas- ured by: “Are you the parent or guardian of any child of any age? Please include your own children, stepchildren, adopted children, grandchildren or others for whom you act as a parent.” Yes is coded as 1. Independent Variables: Self-Perceived Competence Education is determined by the question: “What is the high- est level of schooling you have completed?” The responses are: less than high school (1), high school or GED (2), trade or technical school beyond high school (3), Some college (4), two- year Associate’s degree (5), four/five-year Bachelor’s Degree (6), some college after BA or BS but without degree (7), pro- fessional degree in medicine, law, dentistry (8), Master’s De- gree or Doctorate (9). Education is used as a continuous vari- able. The variable years worked in the current job is measured by the question: “How long have you worked for your current employer or been involved in your main line of job?” This is an interval-level variable. Occupation is a dummy variable measured by the open- ended question: “What kind of work do you do or what is your occupation?” In the dataset there is a variable that has 2 catego- ries of occupation: managerial or professional (1) and others (2). Here “managerial or professional” is coded as 1. Work-family spillover is an index of 4 items: “In the past three months, how often have you NOT had enough time for your family or other important people in your life because of your job?” “In the past three months, how often have you NOT had the energy to do things with your family or other important people in your life because of your job?” “In the past three months how often has work kept you from doing as good a job at home as you could?” “In the past three months, how often have you NOT been in as good mood as you would like to be at home because of your job?” The responses are: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), very often (5). The alpha is 0.59. Satisfaction with income is determined by the question: “How satisfied are you with how much you earn in your main job?” The response categories are: not satisfied at all (1), not too satisfied (2), somewhat satisfied (3), very satisfied (4). Perceived promotional opportunity is measured by the ques- tion: “How would you rate your own chance to advance in your organization?” The responses are: poor (1), fair (2), good (3), excellent (4). This variable is used as a continuous variable. Independent Variables: Re flected Appraisals Supportive workplace culture is a scale of 5 items: “There is an unwritten rule at my place of employment that you can’t take care of family needs on company time.” “At my place of employment, employees who put their family or personal needs ahead of their jobs are not looked on favorably.” “If you have a problem managing your work and family responsibilities, the attitude at my place of employment is: ‘You made your bed, now lie in it!’” “At my place of employment, employees have to choose between advancing in their jobs or devoting attention to their family or personal lives.” Response categories are: strongly agree (1), somewhat agree (2), somewhat disagree (3), and strongly disagree (4). The fifth item is, “At my company or organization where I work, I am treated with respect.” Re- sponses are strongly disagree (1), somewhat disagree (2), some- what agree (3) and, strongly agree (4). The alpha is 0.72. Supportive supervisor is a scale of 10 items: “My supervisor or manager keeps me informed of the things I need to know to do my job well;” “My supervisor or manager has expectations of my performance on the job that are realistic;” “My supervi- sor or manager recognizes when I do a good job;” “My super- visor or manager is supportive when I have a work problem;” “My supervisor or manager is fair and doesn’t show favoritism in responding to employees’ personal or family needs;” “My supervisor or manager accommodates me when I have family or personal business to take care of;” “My supervisor or man- ager is understanding when I talk about personal or family is- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 21  D. BANERJEE Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 22 sues that affect my work;” “I feel comfortable bringing up per- sonal or family issues with my supervisor or manager;” “My supervisor or manager really cares about the effects that work demands have on my personal and family life;” “I consider my supervisor or manager to be a friend both at work and off the job.” The responses are: strongly disagree (1), somewhat dis- agree (2), somewhat agree (3), strongly agree (4). The alpha is 0.90. Coworkers’ support is a scale of 2 items. The questions are: “I have the support from coworkers that I need to do a good job;” and “I have support from coworkers that helps me to ma- nage my work and personal and family life.” The responses are: strongly disagree (1), somewhat disagree (2), somewhat agree (3), and strongly agree (4). The alpha is 0.68. Methods of Analys es Data analyses for this study are based on quantitative meth- ods. The variability of all the variables was tested by running frequency distributions. Variables with more-or-less normal distributions with acceptable skewness and kurtosis were in- cluded. Next, factor analyses were conducted to construct scales for the variables that consist of more than one item. Items with factor loadings greater than 0.50, were included. First, I conducted independent sample t-tests to examine the gender and race-based differences in workplace identity of the workers. Then, I tested the given research questions via OLS regression. In regression analyses the impacts of demographics, self-perceived competence, and reflected appraisals variables on workplace identities of salaried workers were examined by entering one set of variables at a time. Analyses were con- ducted by using SPSS 19. Tables 1(a) and (b) present the results from independent sample t-test, where I compared the means of workers’ work- place identity in terms of their gender and race respectively. Table 1(a) shows that there is no significant difference in work- place identity between women and men workers. However, Table 1(b) demonstrates that white workers have greater work- place identity (mean score = 27.08) than non-white workers (mean score v = 26.85). And this difference is statistically sig- nificant at p < 0.001 level. Next, I present the results of OLS regression of workplace identity on three sets of independent variables (including one set at a time) in Table 2 (please refer to Appendix A). Model 1 shows that, gender per se does not impact the workplace iden- tity considerably. However, white women workers have sig- nificantly stronger sense of identity than non-white women workers (at p < 0.001). This result also reinforces the findings from Table 1(b). Again, women workers with partners (p < 0.05) and those with children (p < 0.05) have significantly stronger workplace identity than women who do not have part- ners and children. When self-perceived competency is included in the regres- sion (Model 2), race continues to be a significant predictor of workplace identity (at p < 0.001). And, women workers with partners (p < 0.05) and those with children (p < 0.001) continue to have stronger workplace identity. It is interesting to note that every variable of self-perceived competency has significant im- pact on worker’s workplace identity at p < 0.001 level. All im- pacts are positive, except for work-family spillover. R2 for workplace identity increases considerably from 0.02 to 0.26 when the set of self-perceived competency is included in the equation. Finally in Model 3, reflected appraisal variables are included in the regression. This model shows that both gender (p < 0.10) and race (p < 0.10) have significant impacts on workers’ iden- tity. Again, all the variables of self-perceived competency still have significant impact workers’ workplace identity (at p < 0.001), all positive effects with an exception for work-family spillover. Furthermore all of the reflected appraisal variables enhance workplace identity of workers considerably (p < 0.001). The R2 increases from Model 2 to Model 3 as 0.26 to 0.43. It is important to note that I have also examined the impact gen- der-race/ethnicity interaction on workplace identities. Since I did not find any significant relationship, I did not include that model in the paper. Conclusion In this paper, I explored how gender and race/ethnicity im- pact workplace identities of American workers. Following the scholarship on gender, work, and occupation, I also examined the impacts of 2 other important factors of workplace identity: self-perceived competence and reflected appraisals, for women and men workers as well as for white and non-white workers. Ac- cordingly, I asked: 1) Do women and men workers in America Table 1. (a) Independent sample t-test comparing workplace identity of women and men workers; (b) Independent sample t-test comparing workplace identity of white and non-white workers. (a) Workers Mean N F t-test (equal variances assumed) t-test (equal variances not assumed) Women 26.93 (4.20) 1328 Men 26.85 (4.12) 1419 0.62 −0.49 −0.49 Note: N is the total number of cases; Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. (b) Workers Mean N F t-test (equal variances assumed) t-test (equal variances not assumed) Whites 27.08 (4.16) 2154 Non-whites 26.07 (4.09) 561 0.16 5.11**** 5.16**** Note: N is the total number of cases; Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations; ****Significance at p < 0.001.  D. BANERJEE Table 2. Unstandardized coefficients from the regression using workplace identity as dependent variable and demographics, self-perceived competence and reflected appraisals as independent variables. Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Demographics Gender (female) 0.06 (0.17) 0.04 (0.15) −0.26* (0.14) Race (white) 0.98**** (0.20) 0.73**** (0.18) 0.32* (0.18) Family (partnered) 0.48** (0.22) 0.43** (0.20) 0.14 (0.20) Being parent (yes) 0.47** (0.21) 0.73**** (0.19) 0.91**** (0.18) Self-Perceived Competence Education 0.13**** (0.04) 0.13**** (0.04) Years in current line of work 0.03**** (0.01) 0.04**** (0.01) Occupation (managerial/professional) 1.14**** (0.18) 0.88**** (0.18) Work-family spillover −0.25**** (0.02) −0.08**** (0.02) Satisfaction with income 0.69**** (0.09) 0.42**** (0.09) Perceived promotional opportunity 1.13**** (0.07) 0.53**** (0.08) Reflected Appraisals Supportive workplace culture 0.22**** (0.03) Supportive supervisor 0.12**** (0.01) Coworkers’ support 0.69**** (0.05) Constant 25.38*** (0.25) 21.91**** (0.44) 11.10**** (0.63) N 2521 2466 2008 F 1.92**** 86.22**** 113.79**** R2 0.02 0.26 0.43 Adjusted R2 0.02 0.26 0.42 Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors; N is total number of cases; ****Significant at p < 0.001; ***Significant at p < 0.01; **Significant at p < 0.05; *Significant at p < 0.10. differ in their perceptions of workplace identities? 2) Do non- white and white workers in America differ in their perceptions of workplace identities? And 3) Do gender and race/ethnicity of the workers impact their workplace identities when self-per- ceived competence of workers, and reflected appraisals of others enter the equation? T-test results show that white workers have a stronger sense of workplace identity than non-white workers (Appendix A: Table 1(b)), however there is no significant difference in work- place identity between women and men workers (Appendix A: Table 1(a)). Results from OLS regression indicate that both self- perceived competency and reflected appraisals have consider- able impacts on American workers’ workplace identities. Inter- estingly, with regards to self-perceived competence, women workers with partners and those with children have a stronger sense of workplace identities than others (Appendix A: Table 2, Model 2). It is possible that because of their household respon- sibilities, women workers with family and/or children are more committed to their workplaces. Thus, they find their jobs more meaningful by properly utilizing their skills and abilities. More- over, these women may realize that their education, experiences, and occupational status are much valued in their workplaces. Hence, they feel more connected to their jobs and create a stronger sense of workplace identity as compared to men. Interestingly, when reflected appraisal of the workers enters the equation (Appendix A: Table 2, Model 3), gender makes a significant impact on their workplace identity with men work- ers having a stronger identity than women workers. Perhaps men workers have greater reflected appraisals in terms of work- place culture and support from their supervisors and coworkers (as compared to women). That is why they express stronger workplace identity than women workers. However, this gender effect on workplace identity is significant only at p < 0.10 level. Moreover, Model 3 demonstrates that with the inclusion of both self-perceived competence and reflected appraisal variables, the impact of race/ethnicity on workplace identity of workers also reduces considerably from p < 0.001 (Model 2) to p < 0.10 (Model 3). It is possible that in today’s workplaces, workers are more concerned about their perceptions regarding income and re- wards, and the supportive work environment. And, these issues are more significant to them for experiencing strong workplace identities than mere demographic details of their characteristics. These findings are consistent with those of Schwalbe and his colleagues (Schwalbe, 1988; Schwalbe et al., 1986). I do not intend to contradict with the literature that suggests Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 23  D. BANERJEE that gender and race/ethnicity are vital determinants of workers’ workplace identities (Schwalbe & Staples, 1991). However, this study shows that in today’s labor market, factors like educa- tional attainment, occupational status, work-family conflicts, satisfaction with income and rewards, and support from work- place people are more important aspects of consideration to address workers’ identities in their workplaces. Perhaps with continued success in different feminist and workers’ move- ments across the nation, workers are becoming increasingly aware of their workplace rights and privileges. Today, they create a stronger sense of identity when they receive the respect and rewards that they deserve from their workplaces. Thus, policies and programs that address workers’ workplace-related well-being should pay more attention to concerns like providing better educational and training programs for workers and creat- ing a supportive network among them to enhance their self-per- ceived competence and reflected appraisals. In conclusion, this study highlights a number of factors that addresses American workers’ well-being in today’s labor mar- ket. Today workers realize that having a better education or grea- ter job autonomy are more important to them than their gender or race/ethnicity to find their jobs meaningful. I consider this phenomenon as a consciousness-raising among the workers that facilitates their understanding of their workplace rights and in- tegrities. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Carolyn C. Perrucci, Professor, Depart- ment of Sociology, Purdue University, and Dr. Allison Carey, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropol- ogy, Shippensburg University for their valuable comments and suggestions while writing this paper. REFERENCES Adam, B. D. (1978). Inferiorization and self-esteem. Social Psychology, 41, 47-53. doi:10.2307/3033596 Bourguignon, D., Seron, E., Yzerbyt, V., & Herman, G. (2006). Perceived group and personal discrimination: Differential effects on personal self-esteem. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 773-789. doi:10.1002/ejsp.326 French, J. R. P., & Caplan, R. D. (1972). Organization stress and strain. In A. J. Marrow (Ed.), The failure of success (pp. 30-66). New York: Amacom. Gardell, B. (1971). Alienation and mental health in the modern indus- trial environment. London: Oxford University Press. Hackman, J. R., & Lawler, E. E. (1971). Employee reactions to job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55, 259-286. doi:10.1037/h0031152 Hughes, M., & Demo, D. (1989). Self-perceptions of black Americans: Self-esteem and personal efficacy. American Journal of Sociology, 95, 132-159. doi:10.1086/229216 Kohn, M. L., & Schooler, C. (1973). Occupational experience and psy- chological functioning: An assessment of reciprocal effects. Ameri- can Sociological Review, 38, 97-118. doi:10.2307/2094334 Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1974). The psychology of sex differ- ences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Mortimer, J. T., & Lorence, J. (1979). Occupational experience and self-concept: A longitudinal study. Social Psychology Quarterly, 42, 307-323. doi:10.2307/3033802 Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assump- tions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3-72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3 Pettigrew, T. F. (1978). Placing Adam’s argument in a broader perspec- tive. Social Psychology, 4 1, 58-61. doi:10.2307/3033598 Reitzes, D. C., & Mutran, E. J. (1994). Multiple role and identities: Factors influencing self-esteem among middle-aged working men and women. Social Psycholog y Qu a rt e r ly , 57, 313-325. doi:10.2307/2787158 Schwalbe, M. L. (1988). Sources of self-esteem in work. Work and Occupations, 15, 24-35. doi:10.1177/0730888488015001002 Schwalbe, M. L., Gecas, V., & Baxter, R. (1986). The effects of occu- pational conditions and individual characteristics on the importance of self-esteem sources in the workplace. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 7, 63-84. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0701_5 Schwalbe, M. L., & Staples, C. L. (1991). Gender differences in the sources of self-esteem. Soc i al Psychology Quarterly, 54, 158-168. doi:10.2307/2786933 Scott, D. M. (1997). Contempt and pity: Social policy and the image of the damaged black psyche, 1880-1996. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/uncp/9780807846353 Simmons, R. G. (1978). Blacks and high self-esteem: A puzzle. Social Psychology, 41, 54-57. doi:10.2307/3033597 Simmons, R. G., & Blyth, D. A. (1987). Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change an d school context. New York: Aldine. Staples, C. L., Schwalbe, M. L., & Gecas, V. (1984). Social class, oc- cupational conditions, and efficacy-based self-esteem. Sociological Perspectives, 27, 85-109. doi:10.2307/1389238 Tharenou, P., & Harken, P. (1982). Organizational correlates of em- ployee self-esteem. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 797-805. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.67.6.797 Twenge, J. M., & Crocker, J. (2002). Race and self-esteem: Meta-ana- lyses comparing Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on gray-little and hafdahl. Psychological Bul- letin, 128, 371-408. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.371 Whitley, B. E. (1983). Sex role orientation and self-esteem: A critical meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 765-778. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.4.765 Wylie, R. C. (1979). The self-concept: Volume 2. Theory and research on selected topics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 24

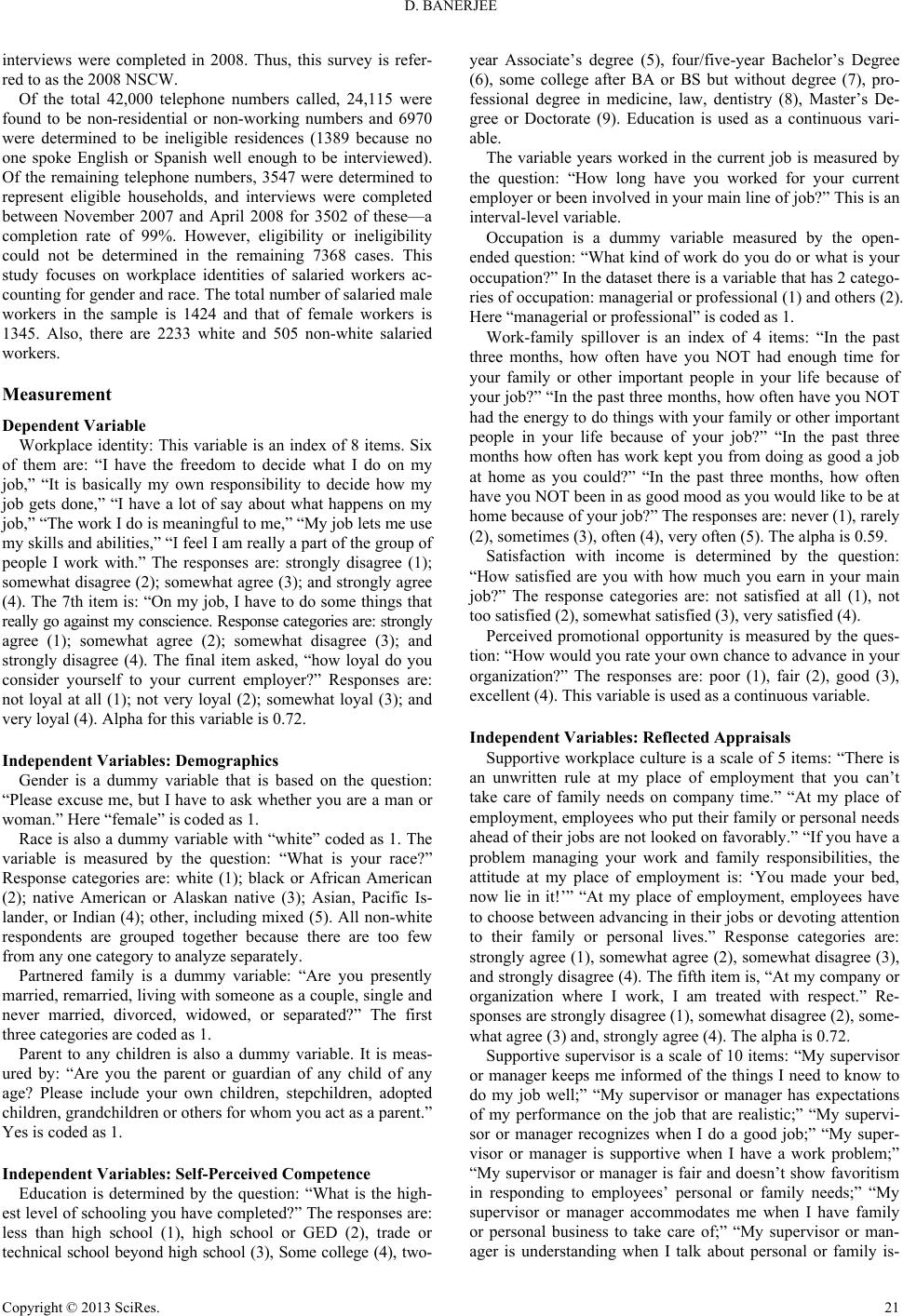

|