Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

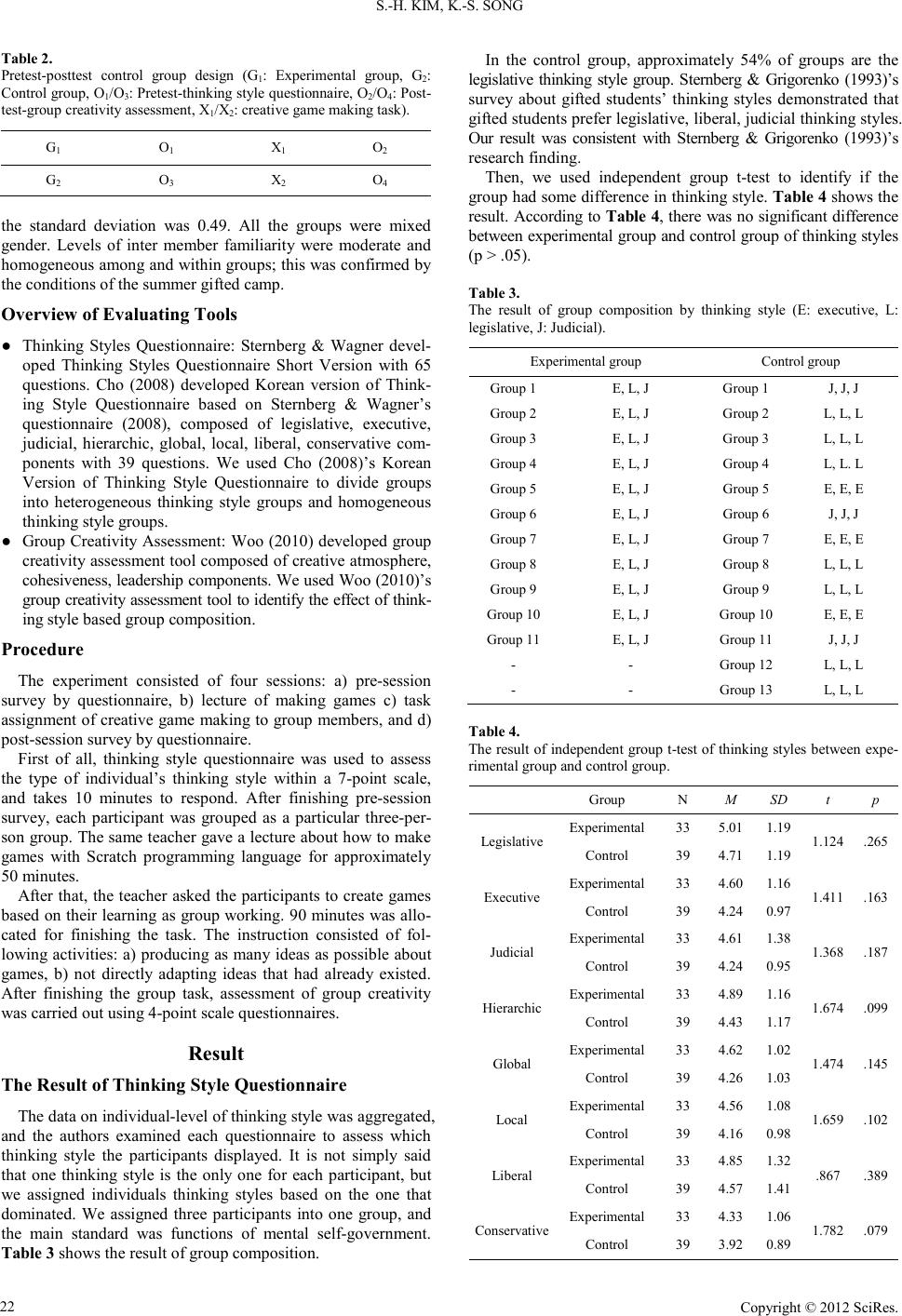

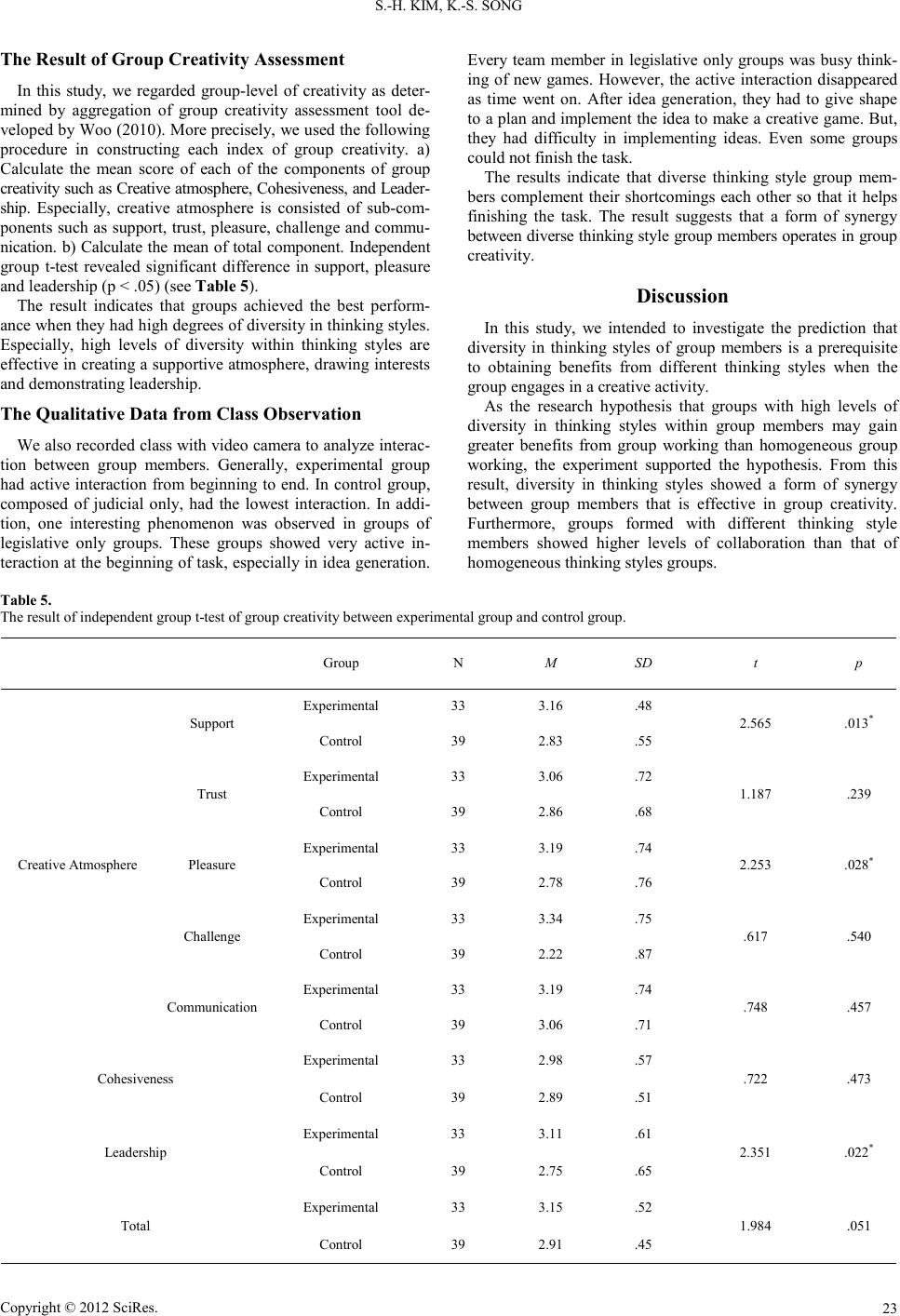

Creat ive Educati on 2012. Vol.3, Supplement, 20-24 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) DOI:10.4236/ce.2012.38b005 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 20 The Effects of Thinking Sty le Based Cooperative Learning on Group Creativity Soon-Hwa Kim1, Ki-Sang Son g2 1Department of Comput er Education for the Gifted, Korea National University of Educat ion, Chung-won, Korea 2Department of Co mputer E d ucation, Korea N ational University of Educat ion, Chung-won, Korea Email: soona6570@gmail.com , kssong@knue.ac.kr Received 20 1 2 Recent s tudies ha ve empha siz ed group cr eati vity withi n a soc io-cul tura l cont ext ra ther than a t an indi vid- ual l evel, but not man y resear cher s report ed stra tegi es for devel oping g roup creat ivity. Thi s p aper ai ms to explore strategies to enhance group creativity based on the theoretical basis of thinking styles by Stern- berg. The hypothesi s was t hat groups wi th members of diverse t hinking st yles w ould show gr eater gai ns in cr eat ive perf ormanc e. In t his s tudy, t he pa rti cipant s (n = 72) w ere divid ed into 24 three-p ers on groups . Each group was given the task to create a game using Scratch programming language. Among the 24 groups, eleven gr oups (n = 33) consi sted of het erogeneous thinking styles, and the other thirteen groups (n = 39) cons isted sol ely of homog eneous thi nking st yles. All divided group s perf ormed same cr eative ta sk. The empi ri c al r es ults supp ort ed the h ypot hesi s tha t group forma ti on of di verse t hink i ng st yle shows b et ter group creati vity. Key words: Group Creati vity; Thinking Style; Socio-Cultural Context Introduction Creativity within groups plays an important role in modern society. Cr eativit y is ac knowledg ed as a cru cial asp ect o f doin g business, research & development, arts and many other social domains. Paulus (2000) suggested that interaction in groups can be an important source of creative ideas and innovations. The products of creativity are main factors in the survival of an organi zat i on. In addition, in this highly specialized age, the collaboration of each group members is becoming important components of work. Generally, creativity is the ability to produce work that is both novel (i.e., original, unexpected) and appropriate (i.e., useful, adaptive when it comes to task constraints) (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). However, creative innovations occur within a socio -cu ltural con text rath er than at an in dividual level. Watso n and Crick’s discovery of the double helix can be a representative historical example. When meeting Crick, Watson (1968, p.31) notes that “Finding someone… who knew that DNA was more important than proteins was real luck.” Thus, we need to empirically evaluate the creative potential (Paulus, 2000) of groups and identify the conditions under which high levels of creativity are realized by group s . Woo, Lee & Kim (2009) suggested that cooperative learning depends on not only group members’ capability but also quantity and quality of interaction. Therefore, appropriate team composition strategies are necessary to enhance creativit y within the group. Man y resear chers have a tentative con clusion t hat heterog eneous group composition is more effective than homogeneous group composition (Sawyer, 2007). Also, group creativity is optimized when group members have different perspectives (Nemeth & Kwan, 1985). There are reports that discordance between team members thinking increases probability of finding novel and appropriate solutions (Nemeth, Personnaz, Personnaz & Goncalo, 2004). However, Woo (2010) warned extreme diversity is harmful to group creativity. Based on his finding, Woo (2010) recommend that group composition through cognitive diversity is one of the most effective methods. Also, Kim (2007) suggested that different wor ki ng styles maximize synergy among group members. In conclusion, heterogeneous group composition creates a complementary relationship among group members so that group creativit y is maxi mized. Ho wever , agreed sp ecific strat egies ar e still absent. Through empirical d ata this paper aims to d iscover specific strategies that lead to a significant improvement in students’ group creativity. We are considering students thinking styles as the parameter of group creativity, and the affect of thinking styles during learning are also discussed in this study. Cooperative Learning Cooperative learning is a teaching and learning method that aims to achieve a common goal through collaboration with group members (Johnson & Johnson, 1999). Cooperative learnin g is an effective teaching method for students to acquire problem-solving skills, critical thinking skills and creativity instead of fragmentary knowledge acquisition. Furthermore, Cooperative learning helps students to develop affective domain such as s elf-esteem, attitude an d social-skills (Johnson, Johnson & Stanne, 2000). The advantage of cooperative learning coincides with contemporary educational goal. Jeong, Park & Hwang (2008) noted that there are lack of studies related to the effective team grouping method although teachers in Korea recognize the necessity of cooperative learning. This is because there is lack of knowledge among teachers in applying the effective model as well aslack of empirical research. When deducting scientific theories, scientists need active collaboration and lively controversy. In the same vein, students need close collaboration with group members when they learn  S.-H. KIM, K.-S. SONG Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 21 something. However, free-ride effect can occur when solving problems with group members. Effective group composition strategies n eed to be stud ied to enhan ce int erdep end ence amon g team members (Johnson & Johnson, 1975). Thinking Styles Thinking styles are the kind of disposition in which people organize or ponder their responses and attitudes toward certain events or work. In other words, thinking styles are the way by which people choose their thought; it does not refer to their capability such as intelligence. It is an issue of whether people want to respond or how they respond to an event. Sternberg expanded the concept of thinking styles upon mental self-government theory; He used this theory to explain the thinking characteristics of creators. He divided thinking styles into 5 main categories and 13 detailed types (Sternberg, 1988; 1990; 1997). Table 1 shows main cate go ries an d detailed types of thinking styles. The functions of mental self-gover nment ar e the t an gib le mental and intellectual reflections of human beings. Generally, a gov- ernment has three function s: legislative, e xecut ive and judicial. Individual’s thinking styles can also be divided into three ana- logous types (Jong, Lin, Wu & Chan, 2006) ● Legislative: This is the inclination to construct one’s own action style and rules as well as the ability to handle unex- pected problems on one’s own, for example, composing ar- ticl es, con du cti n g academic r es e ar c h, and cre ating arti st ic wor k. People of this type are typically good at expressing their creativity. ● Executive: This is the inclination to follow rules, deal with expected problems, and practice duties under existing rules. Examples include applying formula to solve problems, giving a speech or teaching based on manuscripts or outlines. People of this type tend to accept commands and act as requested. ● Judicial: This is the inclination to assess regulations and pro- grams, make regulations, handle analyzable materials or con- ceptual issues. Examples include giving comments, conducting system analysis, and examining plans. People of this type have strong critical analysis skills. Sternberg thought that thinking styles constitute mental self- government. He indicated that the mental operations of human beings are identical to those of governments by using government organization as a metaphor. Just as a government have department Tabl e 1. 5 mai n cat e gories and 13 de t ailed categories of thinking styles. Main categories D etaile d types Functions of mental self-government 1. Executive 2. Legislative 3. Judicial Forms of mental self-government 1. Monarchic 2. Hierarchic 3. Oligarchi c 4. Anarchic Levels of mental self-govern ment 1. Global 2. Local Orientations of ment al self-government 1. Internal 2. External Ideologies of mental se lf-government 1. Liberal 2. Conservative to handle events; the same applies to people with different thinking styles. The three thinking styles mentioned above coexist in each person, but with different levels of portion. Sternberg concluded that a group of people with different thinking styles might per- form better in cooperative activities (Sternberg, 1997). Thus, this study investigated the effects of thinking style based group composition on group creativity for students. Group Creativity The early stages of creativity research focused on the psy- chological determinants for the individual of genius and gif- tedness (Jeffrey & Craft, 2001). But research into creativity in the 1980s and 1990s became rooted in social structures effect on individual creativity (Jeffrey & Craft, 2001). This is so- called social psychology and systems theory. In this context, Sawyer (2003) defined group creativity as ‘two or more people do something together pursuing a novel and appropriate out- come. Also, he insisted that group creativity is not fully under- stood by psychology investigating individuals’ inner side. Siau (1995) illustrated components of group creativity as input, proc- ess, output (see Figure 1.) Based on the framework of group creativity, Fig ure 1, group creativity test was developed by Woo (2010). Method Experimental Design In this study, pretest-posttest control group (groups of dif- ferent thinking style members/groups of same thinking style members) d esign was used and the task of creatin g a game was given to each group. Before beginning the class, a thinking style test was carried out to divide participant into a control group and an experimental group. After completing the class teaching, a group creativity test was given to the participants. Table 2 shows the design of this study. Participants Sevent y three 4 ~6th grade students who joined the university summer gifted camp participated in this study. 33 (22 boys, 11 girls) stu den ts were assigned as experimental group, and 39 (24 boys, 15 girls) were assigned to control group. The mean age of experimental group was 11.97 years old; the standard deviation was 0.97, the mean age of control group was 11.97 years old; Figure 1. Components of group creativity (Siau, 1995).  S.-H. KIM, K.-S. SONG Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 22 Tabl e 2. Pretest-posttest control group design (G1: Experimental group, G2: Cont rol group, O1/O3: Pretes t-t hinking st yle qu esti onnaire, O2/O4: Post- test-group creativity assessment, X1/X2: creat ive gam e makin g task) . G1 O1 X1 O2 G2 O3 X2 O4 the standard deviation was 0.49. All the groups were mixed gender. Levels of inter member familiarity were moderate and homogeneous among and within groups; this was confirmed by the conditions of the summer gifted camp. Overview of Evaluating Tools ● Thinking Styles Questionnaire: Sternberg & Wagner devel- oped Thinking Styles Questionnaire Short Version with 65 questions. Cho (2008) developed Korean version of Think- ing Style Questionnaire based on Sternberg & Wagner’s questionnaire (2008), composed of legislative, executive, judicial, hierarchic, global, local, liberal, conservative com- ponents with 39 questions. We used Cho (2008)’s Korean Version of Thinking Style Questionnaire to divide groups into heterogeneous thinking style groups and homogeneous thinking style groups. ● Group Creativity Assessment: Woo (2010) developed group creativit y assessment tool composed o f creative atmosph ere, cohesiveness, leadership components. We used Woo (2010)’s group creativity assessment tool to identify the effect of th ink- ing style based group composition. Procedure The experiment consisted of four sessions: a) pre-session survey by questionnaire, b) lecture of making games c) task assign ment o f creative game makin g to group members, and d) post-session survey by questionnaire. First of all, thinking style questionnaire was used to assess the type of individual’s thinking style within a 7-point scale, and takes 10 minutes to respond. After finishing pre-session survey, each participant was grouped as a particular three-per- son gro up. The same t eacher gave a l ecture abo ut ho w to make games with Scratch programming language for approximately 50 minutes. After that, the teacher asked the participants to create games based on their lear ning as group wor king. 90 minu tes was allo- cated for finishing the task. The instruction consisted of fol- lowing acti viti es: a) producin g as man y ideas as p ossible abou t games, b) not directly adapting ideas that had already existed. After finishing the group task, assessment of group creativity was carried out using 4-point scale questionnaires. Result The Result of Thinking Style Questionnaire The data on individual-level of thinking style was aggregated, and the authors examined each questionnaire to assess which thinking style the participants displayed. It is not simply said that one thinking style is the only one for each participant, but we assigned individuals thinking styles based on the one that dominated. We assigned three participants into one group, and the main standard was functions of mental self-government. Table 3 shows the result of group composition. In the control group, approximately 54% of groups are the legislative thinking style group. Sternberg & Grigorenko (1993)’s survey about gifted students’ thinking styles demonstrated that gifted students prefer legislative, liberal, judicial thinking styles. Our result was consistent with Sternberg & Grigorenko (1993)’s research fin di ng. Then, we used independent group t-test to identify if the group had some difference in thinking style. Table 4 shows the result. According to Table 4, there was no significant difference between experimental group and control group of thinking styles (p > .05). Tabl e 3. The result of group composition by thinking style (E: executive, L: legisla tive, J: Jud icial). Experimental group Control group Group 1 E, L, J Group 1 J, J, J Group 2 E, L, J Group 2 L, L, L Group 3 E, L, J Group 3 L, L, L Group 4 E, L, J Group 4 L, L. L Group 5 E, L, J Group 5 E, E, E Group 6 E, L, J Group 6 J, J, J Group 7 E, L, J Group 7 E, E, E Group 8 E, L, J Group 8 L, L, L Group 9 E, L, J Group 9 L, L, L Group 10 E, L, J Group 10 E, E, E Group 11 E, L, J Group 11 J, J, J - - Group 12 L, L, L - - Group 13 L, L, L Tabl e 4. The resu lt of independent group t -test of thinking styles between expe- rimental group and control group. Group N M SD t p Legislative Experimental 33 5.01 1.19 1.124 .265 Control 39 4.71 1.19 Executive Experim ental 33 4.60 1 .16 1.411 .163 Control 39 4.24 0.97 Judicial Exper imental 33 4.61 1.38 1.368 .187 Control 39 4.24 0.95 Hierarchic Experimental 33 4.89 1.16 1.674 .099 Control 39 4.43 1.17 Global Experimenta l 33 4 .62 1.02 1.474 .145 Control 39 4.26 1.03 Local Experimenta l 33 4.56 1.08 1.659 .102 Control 39 4.16 0.98 Liberal Expe rimental 33 4.85 1.32 .867 .389 Control 39 4.57 1.41 Conservative Expe rimental 33 4.33 1.06 1.782 .079 Control 39 3.92 0.89  S.-H. KIM, K.-S. SONG Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 23 The Result of Group Creativity Assessment In this study, we regarded group-level of creativity as deter- mined by aggregation of group creativity assessment tool de- veloped by Woo (2010). More precisely, we used the following procedure in constructing each index of group creativity. a) Calculate the mean score of each of the components of group creat ivit y su ch as Cr eative at mosp here, Coh esiv eness, and Lead er- ship. Especially, creative atmosphere is consisted of sub-com- ponents such as support, trust, pleasure, challenge and commu- nication. b) Calculate the mean of total component. Independent group t-test revealed significant difference in support, pleasure and l eadership (p < .05) (see Tabl e 5). The result indicates that groups achieved the best perform- ance when they had high degrees of diversity in thinking styles. Especially, high levels of diversity within thinking styles are effective in creating a su pportive atmosp here, dr awing interests and demonstrating leadership. The Qualitative Data from Class Observation We also recor ded cl ass with video camera to analyze inter ac- tion between group members. Generally, experimental group had active interaction from beginning to end. In control group, composed of judicial only, had the lowest interaction. In addi- tion, one interesting phenomenon was observed in groups of legislative only groups. These groups showed very active in- teractio n at the begin ning of task, esp ecially in id ea generatio n. Every team member in legislative only groups was busy think- ing of new games. However, the active interaction disappeared as time went on. After idea generation, they had to give shape to a plan an d implement the id ea to make a creative game. Bu t, they had difficulty in implementing ideas. Even some groups could not finish the task. The results indicate that diverse thinking style group mem- bers complement their shortcomings each other so that it helps finishing the task. The result suggests that a form of synergy between diverse thinking style group members operates in group creativity. Discussion In this study, we intended to investigate the prediction that diversity in thinking styles of group members is a prerequisite to obtaining benefits from different thinking styles when the group engages in a creat ive activity. As the research hypothesis that groups with high levels of diversity in thinking styles within group members may gain greater benefits from group working than homogeneous group working, the experiment supported the hypothesis. From this result, diversity in thinking styles showed a form of synergy between group members that is effective in group creativity. Furthermore, groups formed with different thinking style members showed higher levels of collaboration than that of homogeneous thinking styles groups. Tabl e 5. The result of independent group t-test of group creativity between experimental group and control group. Group N M SD t p Creative Atmosphere Support Experimen tal 33 3.16 .48 2.565 .013* Control 39 2.83 .55 Trust Experimenta l 33 3.06 .72 1.187 .239 Control 39 2.86 .68 Pleasure Experim ental 33 3.19 .74 2.253 .028* Control 39 2.78 .76 Challenge Experimen tal 33 3.34 .75 .617 .540 Control 39 2.22 .87 Communication Exper imental 33 3.19 . 74 .748 .457 Control 39 3.06 .71 Cohesiveness Experimental 33 2.98 .57 .722 .473 Control 39 2.89 .51 Leadership Expe rimental 33 3.11 .61 2.351 .022* Control 39 2.75 .65 Total Experimenta l 33 3 .15 .52 1.984 .051 Control 39 2.91 .45  S.-H. KIM, K.-S. SONG Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 24 It is interesting that this hypothesis is working at the elemen - tary and middle school level classroom teaching. This implies that the group formation strategies affect overall classroom productivity but needs further studies due to the importance of the K-12 education period of acquiring characters to tolerate and cooperation with others. Acknowledgements This work has been supported by the Korea National Univer- sity of Education Fund in 2012. REFERENCES Cho, K.T. (2008). Relations with Sternberg’s thinking styles, learning styles and probl em solving. Ph.D . Thesis. Chung-Ang University. Jeffrey, B. & Craft, A. (2001). The un iversalization of creativity. In A. Craft, B. Jeffrey, & M. Leibling (Eds.). Creativity in education. London : Continuu m International Publishing Group. Jeong, H.C, Park, Y.S & Hwang, D.J (2008) Analyzing perceptions of small gr ou p in qui ry ac ti vi t y in th e gifted educ ati on of Korea. Journal of the Kore an eart h sci en ce s o cie ty , 2 9(2), 151-162 Johnson, D.W. & Johnson, R.T. (1975) Learning together and alone: cooperation, competition and individualization. Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Pren tice Hall. Johnson, D.W. & Johnson, R.T. (1999) Learning and together and alone : Coope rati ve, compet i tive and indi vidua li stic le arni ng (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T. & Stanne, M.B. (2000). Cooperative learning methods: A meta-analysis. Retrieved january 20th, 2011 from http:// www.tablelearning.com/uploads/File/EXHIBIT-B.pdf Jong, B.S., Lin,T.W., Wu,Y.L., & Chan,T.Y. (2006). Effective two phase cooperative learning on the WEB. Journal of Information Scie nce and En g i n e ering , 22(2), 425-446. Kim, Y.C (2007) Group creativity: How it could be effective? The Korean Journal of Thinking & Problem solving, 3(1), 1-26. Nemeth, C. & Kwan, J.L. (1985) Learning together and alone: cooperation, competition and individualization. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pren tice Hall. Nemeth, C., Personnaz, M., Personnaz, B., & Goncalo, J. (2004) The libera ting role of con flict in group c reat ivity: A cross-cultural study. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 365-374. Paulus, P.B. (2000) Groups, teams, and creativity: The creative potential of idea-generating groups. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49, 237-262. Sawyer, R.K. (2007) Group creativity: Music, theater, collaboration. Mahwah, NJ: Lawence Eribaum. Sawyer. R. K. (2007). Group genius: The creative power of collaboration. New York: Basic Books. Sawyer, R. K. (Editor). (2006). Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. New York: Cambridge U niver sity Press. Siau, K. L. (1995). Group Creativity and Technology. Journal of Creative Behavior, 29( 3) . 2 01-216. Sternberg, R. J. (1988). Mental Self-government: A theory of intellectual styles and their development. Human Development, 31, 197-224. Sternberg, R. J. (1990). Thinking Styles: Keys to understanding student performance. Phi Delta Kappan, 71, 366-371. Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Thinking Styles. New York: Cambridge University Press. Sternberg, R. J., & Wagner, R. K. (1992). Thinking styles inventory. New Haven, Yale University, Unpublished Inventory. Sternberg, R.J. & Grigorenko, E.L. (1995) Thinking style and gifted. Roeper Revi ew, 16(2) , 1 22-130. Watson, J.D. (1968) The double helix: A personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA. New York: New American Li br ary. Woo, S.H, Lee, H.J & Kim, J.W (2009) A method of composing an effictive design cooperative learning group-elementary school students in the early grades, Journal of Korean society of design science, 2 2(4). 93-108. Woo, S.H. (2010) Design coo per ativ e le a rning fo r pr omoti ng creat ivit y on early elementary grades: A method for group composition. Ph.D. Thesis, Yeo n-sae university. |