Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

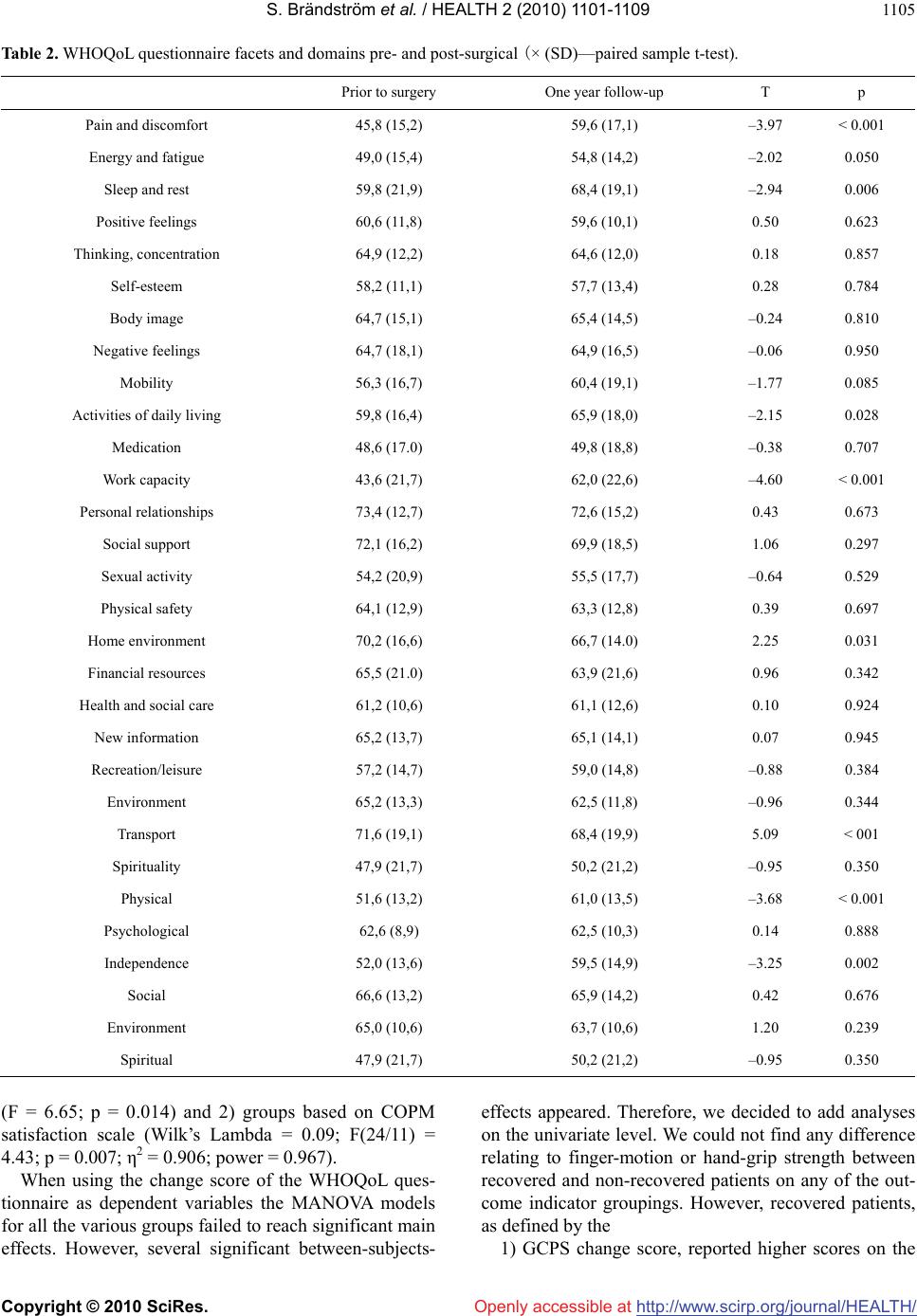

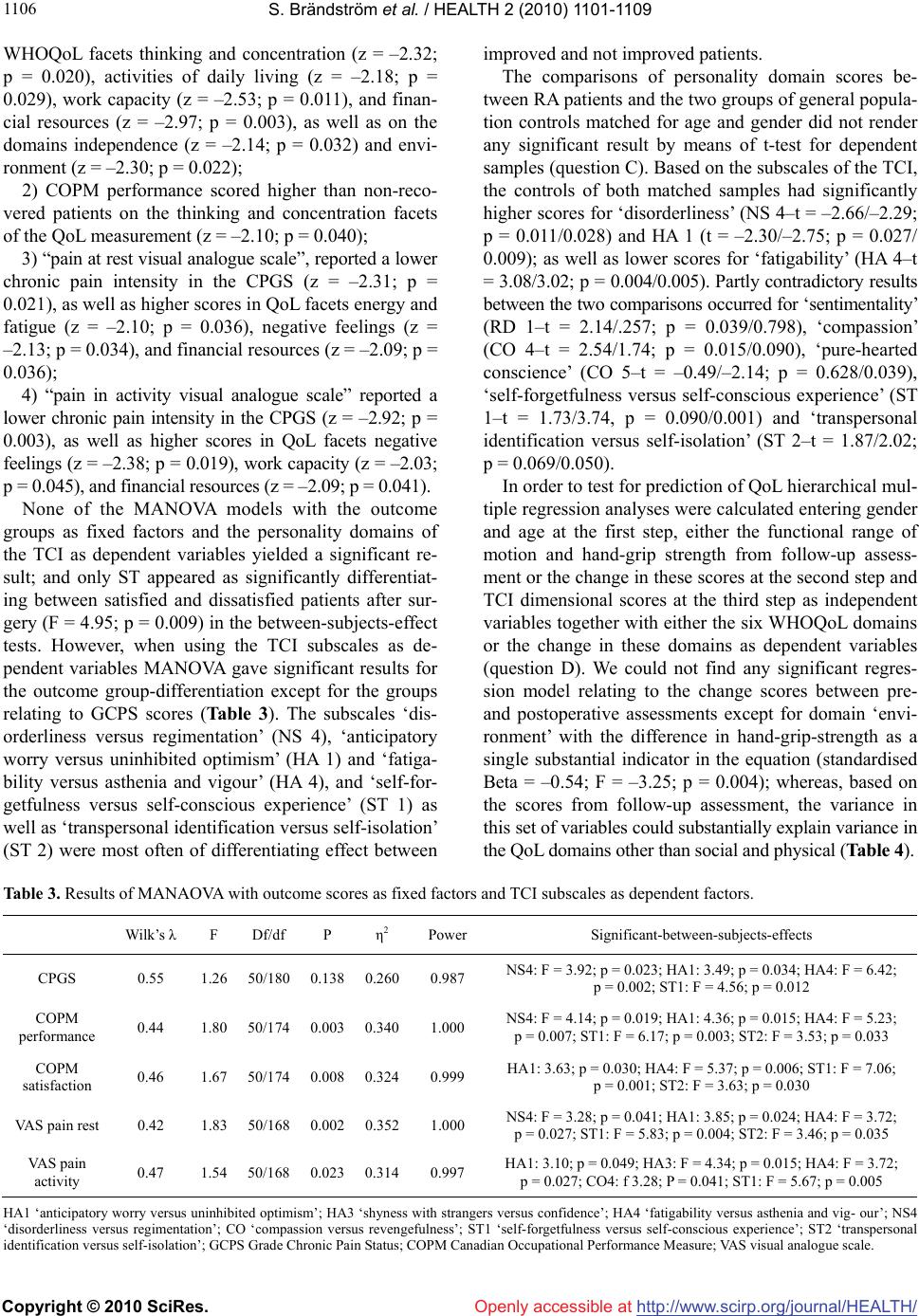

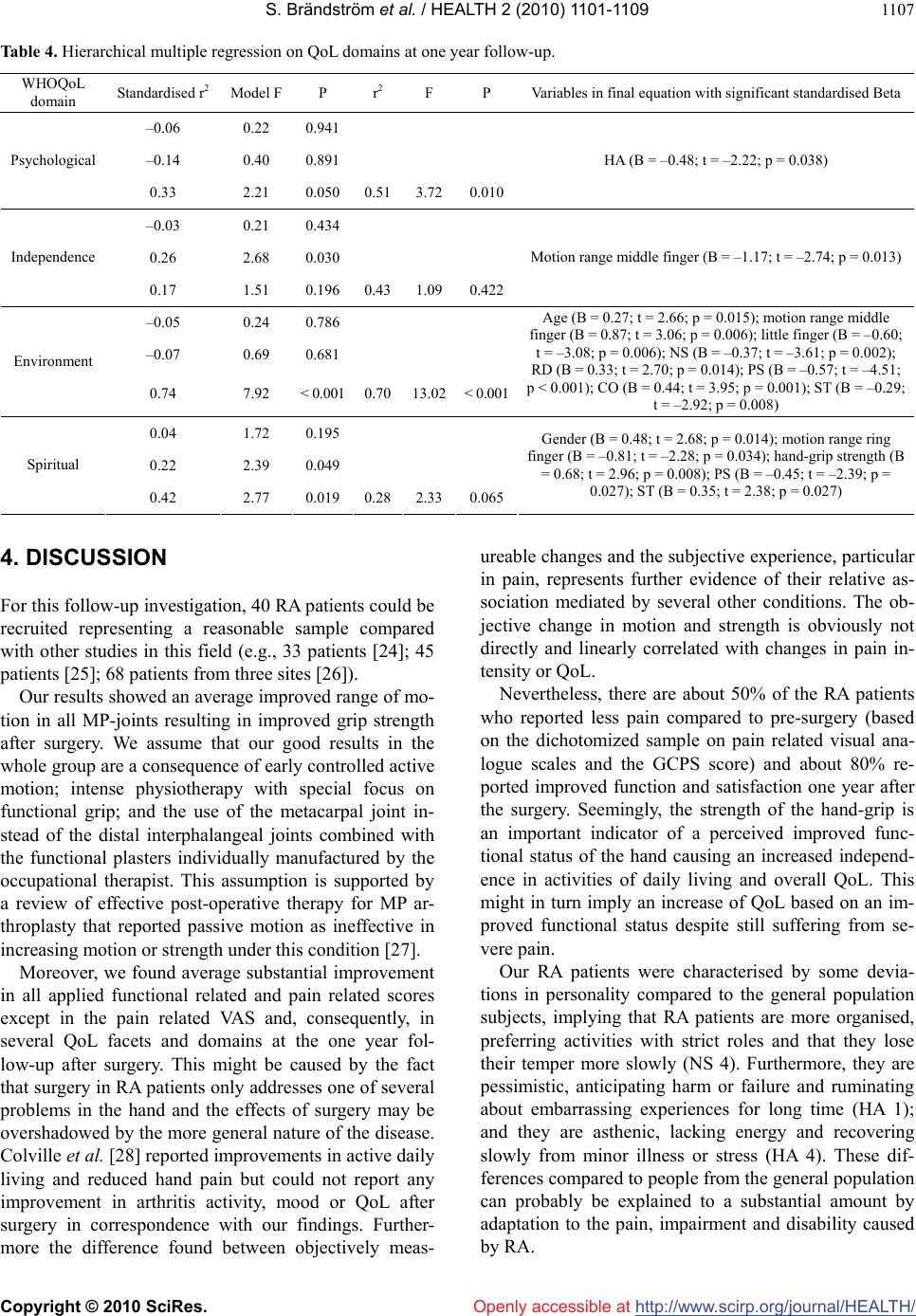

Vol.2, No.9, 1101-1109 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.29163 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Temperament and character as predictor of health related quality of life after metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty ——Personality and MCP joint arthroplasty outcome Sven Brändström1, Kurt Pettersson2, Jörg Richter3* 1Department of Neuroscience and Locomotion, Division of Psychiatry Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; sosb@telia.com 2Department of Hand Surgery, Örebro University Hospital, Örebro, Sweden; kurt.pettersson@orebroll.se 3Department of Psychology, Center for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Oslo, Norway; *Corresponding Author: jrichterj@ web.de Received 30 March 2010; revised 26 April 2010; accepted 28 April 2010. ABSTRACT Purpose: To evaluate personality characteris- tics’ impact upon outcome after silicone-based MP arthroplasty in RA patients. Methods: 40 RA patients who had undergone operations on their MP joints were investigated in a one-year fol- low-up. Objective measurement to assess grip strength and active range of motion—Paper- pencil-tests to assess pain during activity and at rest performance, QoL, and personality. Results: Significant improvement was observed in func- tion and pain related scores except for the pain related VAS and in several QoL facets and do- mains. Patients who experienced improvement reported higher scores on the activities of daily living facet of the WHO QoL questionnaire. Those with lower pain showed more independ- ence. The variance of the QoL domain scores, other than social and physical domains, could substantially and meaningfully be explained by variance of objective measures combined with personality scores. Conclusions: Most RA pa- tients’ QoL can be improved by MP arthroplasty despite remaining substantial level of pain. NS and HA seem to play an important role in the adaptation process during the long term, chronic illness; whereas SD represents a tool of coping with the burden of pain and disability. Personal- ity characteristics are highly predictive for QoL suggesting their important mediating role be- tween experienced pain and disability and HR QoL. Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis; Health Related Quality of Life; MP Joint Arthroplasty; Temperament; Character 1. INTRODUCTION Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients usually suffer from pain, joint or muscle stiffness, and fatigue, causing dis- ability complicated by unpredictable exacerbations [1,2] which impacts upon social and psychological function- ing such as employability, independence, self-concept, mood and subsequently upon general wellbeing in terms of health related quality of life (HRQoL). However, there are patients with objective indications of RA who do not report pain and others who report severe pain without positive immunological parameters [3]. This observed variability in pain experience suggests that other factors might be of importance as mediators be- tween objective measures, such as joint dysfunction or clinical findings in the serum, and pain experience or HRQoL as indicators of well-being. There has been much discussion as to whether patients suffering from RA have a particular personality type. The evidence is not convincing and the role of stress in the aetiology of rheumatoid arthritis is not fully understood [4]. However, coping responses to stress (in the case of RA patients in terms of pain, physical and social disabilities) are deter- mined by several psychological processes including personality characteristics. Therefore, personality is con- sidered to be a major phenomenon impacting upon pain- perception and quality of life. Indeed, Chou and Brauer [1] found negative affect in the sense of Watson’s and Clark’s theory [5] determining subjective health inde- pendent of age, marriage, or length of disease. This might  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1102 be explained by the fact that negative affect is often com- bined with self-focused attention and with a negative memory bias. Self-esteem and adjustment to RA has to be regarded as mediators between RA on the one hand, and subjective experience of pain and psychological well-being on the other hand [2]. Furthermore relating to emotional processing in older women with RA, the variability of pain reactivity was found dependent on both emotional intensity and the ability to regulate emo- tion in a longitudinal investigation by Hamilton, Zautra and Reich [6]. There is general agreement that psychological factors such as personality may influence patients’ adjustment and outcome of surgical interventions [7,8]. For example, dissatisfied patients were characterized by significantly higher aggressiveness, lower extraversion, and more health worries compared to satisfied patients without differences in hallux valgus angle or intermetatarsal angle (I-II) three month after operative hallux valgus correction [9]. In another study, Hyphantis et al. [10] reported that arthri- tis-related pain and hostility were negatively related to both physical as well as psychological health in patients suffering from systemic sclerosis. Silicone-based metacarpophalangeal (MP) arthroplasty still remains the primary treatment for patients with se- vere degenerative destruction of joints. Joint pain and deformity affecting hand function are the two primary indications for performing metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasties. Most rheumatoid patients with significant pain and destroyed MP joints are also noted to have palmar subluxation of the proximal phalanx with ulnar subluxation of the extensor tendon, resulting in a fixed flexed posture of the MP joints, which impairs overall function and reduces power. However, the main disad- vantage is the inability to obtain a postoperative range of motion close to that of the normal hand [11]. Substantial improvement in range of motion, pain, ul- nar deviation and patient satisfaction have been reported as the outcomes of MP arthroplasty with “reported post- operative arcs of motion vary from 38 to 60 degrees” and “extension lags also vary from 9 to 22 degrees” [12]. Rittmeister et al. [13] evaluated the outcome of silicon MP arthroplasty as “good” in 40 joints, as “fair” in 10 joints, and as “poor” in none. In a “formal systematic review of all available world literature” Squitieri and Chung [14] found silicone MP joint arthroplasty to be superior to vascularised toe joints or PyroCarbon joints with a mean active range of motion of 47 +/- 16 degrees and a complication rate of 18%. However, maintenance or recurrence even years later after surgery were re- ported in some patients [12]. The aim of the study was to evaluate if personality cha- racteristics impact upon the outcome of silicone-based MP arthroplasty in RA patients. The following questions were to be answered; 1) Are there differences between recovered and non-recovered patients pre- and post silicone-based MP arthroplasty according to pain severity, movement capacity, HRQoL, and personality? 2) Is the objectively measureable change associated with perceived improvement? 3) Are there differences in personality characteristics between severe RA patients who received silicone-based MP arthro- plasty and healthy individuals? 4) Do psychological or sociodemographic variables predict QoL after silicone- based MP arthroplasty or can related differences between recovered and non-recovered patients be explained by personality characteristics? 2. METHODS 2.1. Sample 40 RA consecutive patients (7 male; 33 female) with an average age of 61.54 ± 9.93 years (range: 32-78) were recruited for this prospective follow-up study. One pa- tient died before follow-up investigation and was there- fore excluded from the analysis. All patients had opera- tions on four MP joints, totalling 156 joints. Indications for surgery were pain and severe deformity of MP joints, which had resulted in severe impairment of hand func- tions in daily life. The MP joints were either volarly subluxated or ulnarly dislocated. No reoperation was per- formed during the study period. In order to control for personality characteristics, data was used from a previous standardisation investigation in northern Sweden [15] investigating the Temperament and Character Inventory [16]. From this data a group of individuals from the general population were matched to the patients, with two individuals matched by age (60.5/ 60.6 ± 10.3 years; range: 30-80) and gender to each pa- tient. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the investigation; and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Umeå University (§127/99 dnr 99-017). 2.2. Measurements 2.2.1. Objective Measurements Preoperatively and postoperatively, all patients were examined by an independent physiotherapist and an oc- cupational therapist. Maximum and mean grip strength was measured with Grippit (AB Detektor, Göteborg, Sw- eden) [17]. The active range of motion was measured with goni- ometry for each phalanx in all joints (MP-metacarpop- halangeal joint, PIP-proximal interphalangeal joint, and  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1103 DIP-distal interphalangeal joint). The active arc of motion was determined by subtract- ing active extension from active flexion. 2.2.2. Rating of Others The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [18] was used to evaluate patient participation in the goal formulation process. It is a semi-structured interview in which the patients identify their problems in occupa- tional performance and rank them. The patients rate their occupational performance related to identified problems and satisfaction with their performance in areas of self- care, productivity, and leisure. Ten-point scales are used ranging from 1—“not able to do it” or “not satisfied at all” to 10—“able to do it extremely well” or “extremely sat- isfied”. 2.2.3. Self-Report Measurements A visual analogue scale (VAS) relating to pain during activities and another concerning pain at rest was applied. The Grade Chronic Pain Status (GCPS—[19]) was developed as “a simple method of grading the severity of chronic pain” (p. 133). Based on the patient’s responses to 7 questions, pain severity is classified into 4 hierar- chical groups: “Grade I, low disability-low intensity; Grade II, low disability-high intensity; Grade III, high disability-moderately limiting; and Grade IV, high dis- ability-severely limiting” (p. 133). Internationally this scale is often used to classify chronic pain combined with pain related disability [10,20,21]. The Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQoL-100 – [22]) consists of 100 items covering six domains (physi- cal health, psychological health, level of independence, social relationships, environment, spirituality, and one general domain - overall quality of life). Each item is measured from 1 to 5 according to four underlying Likert scales referring to intensity, capacity, frequency and eva- luation. All scores are standardized as 0 = worst quality of life to 100 = best quality of life scale. The internal consistency was reported to be 0.97; the test-retest reli- ability was 0.70; and an intensive validation study of the Danish version supports the satisfactory external and dis- criminant validity [23]. A special feature of this WHOQoL questionnaire is its focus on satisfaction with various aspects of life. It cov- ers relevant factors of health related QoL such as pain, physical function, and capacity for work. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-9 version) is a 238 item true-false self-administered paper- and-pencil test based on Cloninger’s biosocial personal- ity theory [16]) and measures the four largely genetically determined and independently inherited temperament dimensions Novelty Seeking (NS—4 subscales); Harm Avoidance (HA—4 subscales); Reward Dependence (RD—3 subscales); and Persistence (PS—single scale) and the three character dimensions Self-Directedness (SD—5 subscales); Cooperativeness (CO—5 subscales); and Self-Transcendence (ST—3 subscales). Tempera- ment refers to individual differences in conditioned emo- tional responses, such as anger, fear, and disgust; and character refers to individual differences in goals, values and self-conscious emotions like shame, guilt and em- pathy [16]. 2.3. Design The RA patients were investigated twice—1) preopera- tive assessment and 2) postoperative assessment after 12 months with all the above described preoperative invest- tigations conducted repeated. Physiotherapeutic treatment and training sessions took place between the two assessments. In postoperative week 6 gradually increased motion was initiated without pressure in radial and ulnar directions. In week 8 daily activities were allowed without weight loading in the ulnar direction. From the postoperative third month no restrictions were set limiting daily activities or work except pain; and finally at 6 months, a clinical evaluation was made and an additional training program, some technical advice or equipment was added or optimised. 2.4. Statistical Analysis Various dichotomous groupings were established relat- ing to the RA patients based on the difference between pre- and postsurgical assessment on several outcome criteria including GCPS, the COPM scores and the vis- ual analogue scales. One group consisted of patients with lower or equal scores (not recovered/not improved) and the other group had higher postoperative scores (recov- ered, improved). The T-test for independent and paired samples was applied in order to test for various group differences for continuous variables on univariate level and MANOVA was calculated on multivariate level. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were calcu- lated in order to test for predictive value of personality scores for QoL post-surgery controlling for age and gender in the first level followed by the measured mo- tion and grip-strength as an control-indicator for object- tive surgery results. 3. RESULTS We found a significant difference between pre- and post- surgical assessment concerning all the parameters meas- ured except for pain. The functional arc of motion in the metacarpal joint changed from 30.8º preoperative to 48.6º one year postoperative (p < 0.001). The active flexion arc changed from 69.4º preoperative to 82.5º (p  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1104 < 0.001). Extension lag improved significantly in all fin- gers between 51.7º to 20.8º (p < 0.001). The range of movement of each of the operated fingers was post- operatively significantly wider than preoperatively (t between 3.15; p = 0.002 for the little finger and 4.16; p < 0.001 for the ring finger). Patients improved signify- cantly in joint mobility and strength (t = 2.57; p = 0.010). The COPM score of performance and satisfaction with occupational performance was significantly higher after surgery. The disability score, number of disability days and the disability points as well as the characteristic pain intensity measured by the GCPS were significantly lower after surgery, whereas the difference in self-evaluation of pain intensity in rest and while active assessed by means of the visual analogue scales did not reach any mean- ingful level of statistical significance (Table 1). On average the scores of the QoL facets pain and dis- comfort, energy and fatigue, sleep and rest, activities of daily living, and work capacity were significantly higher one year after surgery (t between –4.60; p < 0.001 for work capacity and –2.02; 0.050 for energy and fatigue), but the score for home environment and transport de- creased (t = 2.2.5; p = 0.031, t = 5.09; p < 0.001 respec- tively). At the domain level, QoL relating to physical (t = –3.68; p < 0.001) and independence (t = –3.25; p = 0.002) were found to be improved (Table 2). When referring to the dichotomised outcome indica- tors GCPS, COPM performance and satisfaction, as well as the visual analogue scale for pain in rest and in active- ity with constant or lower scores at postsurgical assess- ment were considered to be not recovered and higher scores considered recovered 54%, 78%, 81%, 47%, and 47% respectively were characterised as recovered (ques- tion A). Multivariate analyses of variance were separately cal- culated with groups (recovered versus not recovered) based on every outcome indicator as fixed factor and with the active range of motion of the operated fingers and the strength of the hand grip at the follow-up assessment as well as with the change of these parameters as dependent variables. None of these models proved to be statistically significant (question B). Nevertheless, the model with COPM performance group as a fixed factor demonstrated a significant tendency (Wilk’s Lambda = 0.68; F(5/27) = 2.53; p = 0.053; η2 = 0.319; power = 0.695); and the change in grip strength yielded a significant result in the test of between-subject-effects relating to the COPM per- formance grouping (F = 6.92; p = 0.013) and in the GCPS grouping MANOVA (F = 4.56; p = 0.040), even though the latter overall model was not significant. When referring to the same groups in MANOVA with QoL facets or domains at 12 months after the operation as dependent variables, none of the models showed a significant main effect of the group variable except for 1) the groups based on the COPM performance scale (Wilk’s Lambda = 0.16; F(24/11) = 2.47; p = 0.060; η2 = 0.840; power = 0.762) with the activities of daily living facet showing a significant between-subject-effect test result Table 1. Mean scores (SD) of outcome indicators at baseline and one year follow-up (paired sample t-test) and follow-up scores de- pendent on recovery classification (based on CPGS classification change—no significant differences). n Baseline prior to surgeryOne year after surgeryT p Recovered N = 21 Non-recovered N = 18 COPM performance 36 4.1 (1.8) 6.9 (2.3) –6.050.001 7.0 (2.3) 6.7 (2.2) COPM satisfaction 36 3.5 (2.0) 6.6 (2.5) –6.050.001 6.7 (2.7) 6.5 (2.3) VAS Pain at rest 33 3.7 (3.0) 3.3 (2.6) 0.720.478 3.2 (2.5) 3.2 (2.9) VAS Pain in activity 33 4.1 (2.9) 3.4 (2.7) 1.300.203 3.3 (2.6) 3.2 (2.9) GCPS Classification 39 2.6 (1.2) 1.8 (2.0) 3.520.001 1.7 (1.0) 2.0 (1.3) GCPS Disability points 39 3.1 (2.1) 1.8 (2.0) 3.110.001 1.5 (1.6) 2.2 (2.3) GCPS Disability Days 39 1.4 (1.2) 0.7 (1.1) 2.890.006 0.6 (1.0) 0.9 (1.2) GCPS Characteristic Pain Intensity39 47.9 (19.0) 39.0 (22.0) 2.140.039 34.6 (18.3) 44.1 (25.2) Range of motion forefinger 37 134.9 (47.4) 154.1 (55.4) –3.90< 0.001 154.7 (55.0) 153.3 (57.4) Range of motion middle finger 37 144.6 (45.8) 167.8 (46.0) –5.30< .001 173.2 (47.2) 162.2 (45.5) Range of motion ring finger 35 135.0 (50.0 161.9 (46.7) –5.43< 0.001 163.9 (50.6) 159.7 (43.6) Range of motion little finger 35 126.7 (50.1) 152.6 (54.5) –3.570.001 149.2 (57.8) 156.2 (52.4) Hand-grip strength 35 70.9 (46.4) 87.0 (48.9) –2.170.036 93.8 (61.8) 79.5 (28.6)  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1105 Table 2. WHOQoL questionnaire facets and domains pre- and post-surgical (× (SD)—paired sample t-test). Prior to surgery One year follow-up T p Pain and discomfort 45,8 (15,2) 59,6 (17,1) –3.97 < 0.001 Energy and fatigue 49,0 (15,4) 54,8 (14,2) –2.02 0.050 Sleep and rest 59,8 (21,9) 68,4 (19,1) –2.94 0.006 Positive feelings 60,6 (11,8) 59,6 (10,1) 0.50 0.623 Thinking, concentration 64,9 (12,2) 64,6 (12,0) 0.18 0.857 Self-esteem 58,2 (11,1) 57,7 (13,4) 0.28 0.784 Body image 64,7 (15,1) 65,4 (14,5) –0.24 0.810 Negative feelings 64,7 (18,1) 64,9 (16,5) –0.06 0.950 Mobility 56,3 (16,7) 60,4 (19,1) –1.77 0.085 Activities of daily living 59,8 (16,4) 65,9 (18,0) –2.15 0.028 Medication 48,6 (17.0) 49,8 (18,8) –0.38 0.707 Work capacity 43,6 (21,7) 62,0 (22,6) –4.60 < 0.001 Personal relationships 73,4 (12,7) 72,6 (15,2) 0.43 0.673 Social support 72,1 (16,2) 69,9 (18,5) 1.06 0.297 Sexual activity 54,2 (20,9) 55,5 (17,7) –0.64 0.529 Physical safety 64,1 (12,9) 63,3 (12,8) 0.39 0.697 Home environment 70,2 (16,6) 66,7 (14.0) 2.25 0.031 Financial resources 65,5 (21.0) 63,9 (21,6) 0.96 0.342 Health and social care 61,2 (10,6) 61,1 (12,6) 0.10 0.924 New information 65,2 (13,7) 65,1 (14,1) 0.07 0.945 Recreation/leisure 57,2 (14,7) 59,0 (14,8) –0.88 0.384 Environment 65,2 (13,3) 62,5 (11,8) –0.96 0.344 Transport 71,6 (19,1) 68,4 (19,9) 5.09 < 001 Spirituality 47,9 (21,7) 50,2 (21,2) –0.95 0.350 Physical 51,6 (13,2) 61,0 (13,5) –3.68 < 0.001 Psychological 62,6 (8,9) 62,5 (10,3) 0.14 0.888 Independence 52,0 (13,6) 59,5 (14,9) –3.25 0.002 Social 66,6 (13,2) 65,9 (14,2) 0.42 0.676 Environment 65,0 (10,6) 63,7 (10,6) 1.20 0.239 Spiritual 47,9 (21,7) 50,2 (21,2) –0.95 0.350 (F = 6.65; p = 0.014) and 2) groups based on COPM satisfaction scale (Wilk’s Lambda = 0.09; F(24/11) = 4.43; p = 0.007; η2 = 0.906; power = 0.967). When using the change score of the WHOQoL ques- tionnaire as dependent variables the MANOVA models for all the various groups failed to reach significant main effects. However, several significant between-subjects- effects appeared. Therefore, we decided to add analyses on the univariate level. We could not find any difference relating to finger-motion or hand-grip strength between recovered and non-recovered patients on any of the out- come indicator groupings. However, recovered patients, as defined by the 1) GCPS change score, reported higher scores on the  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1106 WHOQoL facets thinking and concentration (z = –2.32; p = 0.020), activities of daily living (z = –2.18; p = 0.029), work capacity (z = –2.53; p = 0.011), and finan- cial resources (z = –2.97; p = 0.003), as well as on the domains independence (z = –2.14; p = 0.032) and envi- ronment (z = –2.30; p = 0.022); 2) COPM performance scored higher than non-reco- vered patients on the thinking and concentration facets of the QoL measurement (z = –2.10; p = 0.040); 3) “pain at rest visual analogue scale”, reported a lower chronic pain intensity in the CPGS (z = –2.31; p = 0.021), as well as higher scores in QoL facets energy and fatigue (z = –2.10; p = 0.036), negative feelings (z = –2.13; p = 0.034), and financial resources (z = –2.09; p = 0.036); 4) “pain in activity visual analogue scale” reported a lower chronic pain intensity in the CPGS (z = –2.92; p = 0.003), as well as higher scores in QoL facets negative feelings (z = –2.38; p = 0.019), work capacity (z = –2.03; p = 0.045), and financial resources (z = –2.09; p = 0.041). None of the MANOVA models with the outcome groups as fixed factors and the personality domains of the TCI as dependent variables yielded a significant re- sult; and only ST appeared as significantly differentiat- ing between satisfied and dissatisfied patients after sur- gery (F = 4.95; p = 0.009) in the between-subjects-effect tests. However, when using the TCI subscales as de- pendent variables MANOVA gave significant results for the outcome group-differentiation except for the groups relating to GCPS scores (Table 3). The subscales ‘dis- orderliness versus regimentation’ (NS 4), ‘anticipatory worry versus uninhibited optimism’ (HA 1) and ‘fatiga- bility versus asthenia and vigour’ (HA 4), and ‘self-for- getfulness versus self-conscious experience’ (ST 1) as well as ‘transpersonal identification versus self-isolation’ (ST 2) were most often of differentiating effect between improved and not improved patients. The comparisons of personality domain scores be- tween RA patients and the two groups of general popula- tion controls matched for age and gender did not render any significant result by means of t-test for dependent samples (question C). Based on the subscales of the TCI, the controls of both matched samples had significantly higher scores for ‘disorderliness’ (NS 4–t = –2.66/–2.29; p = 0.011/0.028) and HA 1 (t = –2.30/–2.75; p = 0.027/ 0.009); as well as lower scores for ‘fatigability’ (HA 4–t = 3.08/3.02; p = 0.004/0.005). Partly contradictory results between the two comparisons occurred for ‘sentimentality’ (RD 1–t = 2.14/.257; p = 0.039/0.798), ‘compassion’ (CO 4–t = 2.54/1.74; p = 0.015/0.090), ‘pure-hearted conscience’ (CO 5–t = –0.49/–2.14; p = 0.628/0.039), ‘self-forgetfulness versus self-conscious experience’ (ST 1–t = 1.73/3.74, p = 0.090/0.001) and ‘transpersonal identification versus self-isolation’ (ST 2–t = 1.87/2.02; p = 0.069/0.050). In order to test for prediction of QoL hierarchical mul- tiple regression analyses were calculated entering gender and age at the first step, either the functional range of motion and hand-grip strength from follow-up assess- ment or the change in these scores at the second step and TCI dimensional scores at the third step as independent variables together with either the six WHOQoL domains or the change in these domains as dependent variables (question D). We could not find any significant regres- sion model relating to the change scores between pre- and postoperative assessments except for domain ‘envi- ronment’ with the difference in hand-grip-strength as a single substantial indicator in the equation (standardised Beta = –0.54; F = –3.25; p = 0.004); whereas, based on the scores from follow-up assessment, the variance in this set of variables could substantially explain variance in the QoL domains other than social and physical (Table 4). Table 3. Results of MANAOVA with outcome scores as fixed factors and TCI subscales as dependent factors. Wilk’s λ F Df/df P η2 Power Significant-between-subjects-effects CPGS 0.55 1.26 50/180 0.138 0.2600.987 NS4: F = 3.92; p = 0.023; HA1: 3.49; p = 0.034; HA4: F = 6.42; p = 0.002; ST1: F = 4.56; p = 0.012 COPM performance 0.44 1.80 50/174 0.003 0.3401.000 NS4: F = 4.14; p = 0.019; HA1: 4.36; p = 0.015; HA4: F = 5.23; p = 0.007; ST1: F = 6.17; p = 0.003; ST2: F = 3.53; p = 0.033 COPM satisfaction 0.46 1.6750/174 0.008 0.3240.999 HA1: 3.63; p = 0.030; HA4: F = 5.37; p = 0.006; ST1: F = 7.06; p = 0.001; ST2: F = 3.63; p = 0.030 VAS pain rest 0.42 1.8350/168 0.002 0.3521.000 NS4: F = 3.28; p = 0.041; HA1: 3.85; p = 0.024; HA4: F = 3.72; p = 0.027; ST1: F = 5.83; p = 0.004; ST2: F = 3.46; p = 0.035 VAS pain activity 0.47 1.5450/168 0.023 0.3140.997 HA1: 3.10; p = 0.049; HA3: F = 4.34; p = 0.015; HA4: F = 3.72; p = 0.027; CO4: f 3.28; P = 0.041; ST1: F = 5.67; p = 0.005 HA1 ‘anticipatory worry versus uninhibited optimism’; HA3 ‘shyness with strangers versus confidence’; HA4 ‘fatigability versus asthenia and vig- our’; NS4 ‘disorderliness versus regimentation’; CO ‘compassion versus revengefulness’; ST1 ‘self-forgetfulness versus self-conscious experience’; ST2 ‘transpersonal identification versus self-isolation’; GCPS Grade Chronic Pain Status; COPM Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; VAS visual analogue scale.  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1107 Table 4. Hierarchical multiple regression on QoL domains at one year follow-up. WHOQoL domain Standardised r2 Model F P r2 F P Variables in final equation with significant standardised Beta –0.06 0.22 0.941 –0.14 0.40 0.891 Psychological 0.33 2.21 0.050 0.513.720.010 HA (B = –0.48; t = –2.22; p = 0.038) –0.03 0.21 0.434 0.26 2.68 0.030 Independence 0.17 1.51 0.196 0.431.090.422 Motion range middle finger (B = –1.17; t = –2.74; p = 0.013) –0.05 0.24 0.786 –0.07 0.69 0.681 Environment 0.74 7.92 < 0.001 0.7013.02< 0.001 Age (B = 0.27; t = 2.66; p = 0.015); motion range middle finger (B = 0.87; t = 3.06; p = 0.006); little finger (B = –0.60; t = –3.08; p = 0.006); NS (B = –0.37; t = –3.61; p = 0.002); RD (B = 0.33; t = 2.70; p = 0.014); PS (B = –0.57; t = –4.51; p < 0.001); CO (B = 0.44; t = 3.95; p = 0.001); ST (B = –0.29; t = –2.92; p = 0.008) 0.04 1.72 0.195 0.22 2.39 0.049 Spiritual 0.42 2.77 0.019 0.282.330.065 Gender (B = 0.48; t = 2.68; p = 0.014); motion range ring finger (B = –0.81; t = –2.28; p = 0.034); hand-grip strength (B = 0.68; t = 2.96; p = 0.008); PS (B = –0.45; t = –2.39; p = 0.027); ST (B = 0.35; t = 2.38; p = 0.027) 4. DISCUSSION For this follow-up investigation, 40 RA patients could be recruited representing a reasonable sample compared with other studies in this field (e.g., 33 patients [24]; 45 patients [25]; 68 patients from three sites [26]). Our results showed an average improved range of mo- tion in all MP-joints resulting in improved grip strength after surgery. We assume that our good results in the whole group are a consequence of early controlled active motion; intense physiotherapy with special focus on functional grip; and the use of the metacarpal joint in- stead of the distal interphalangeal joints combined with the functional plasters individually manufactured by the occupational therapist. This assumption is supported by a review of effective post-operative therapy for MP ar- throplasty that reported passive motion as ineffective in increasing motion or strength under this condition [27]. Moreover, we found average substantial improvement in all applied functional related and pain related scores except in the pain related VAS and, consequently, in several QoL facets and domains at the one year fol- low-up after surgery. This might be caused by the fact that surgery in RA patients only addresses one of several problems in the hand and the effects of surgery may be overshadowed by the more general nature of the disease. Colville et al. [28] reported improvements in active daily living and reduced hand pain but could not report any improvement in arthritis activity, mood or QoL after surgery in correspondence with our findings. Further- more the difference found between objectively meas- ureable changes and the subjective experience, particular in pain, represents further evidence of their relative as- sociation mediated by several other conditions. The ob- jective change in motion and strength is obviously not directly and linearly correlated with changes in pain in- tensity or QoL. Nevertheless, there are about 50% of the RA patients who reported less pain compared to pre-surgery (based on the dichotomized sample on pain related visual ana- logue scales and the GCPS score) and about 80% re- ported improved function and satisfaction one year after the surgery. Seemingly, the strength of the hand-grip is an important indicator of a perceived improved func- tional status of the hand causing an increased independ- ence in activities of daily living and overall QoL. This might in turn imply an increase of QoL based on an im- proved functional status despite still suffering from se- vere pain. Our RA patients were characterised by some devia- tions in personality compared to the general population subjects, implying that RA patients are more organised, preferring activities with strict roles and that they lose their temper more slowly (NS 4). Furthermore, they are pessimistic, anticipating harm or failure and ruminating about embarrassing experiences for long time (HA 1); and they are asthenic, lacking energy and recovering slowly from minor illness or stress (HA 4). These dif- ferences compared to people from the general population can probably be explained to a substantial amount by adaptation to the pain, impairment and disability caused by RA.  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1108 However, it partly confirms findings of Chou and Brauer [1] of high negative affect in RA patients as well of difficulties in regulating emotions in pain patients by Hamilton et al. [6]. The many anticipatory worries iden- tified, combined with the limited openness and flexibil- ity in their behaviour might in turn cause more self- focussed attention, including attention to pain signals, leading to increased passivity and avoidance of activity in order to prevent increasing pain which in turn would negatively affect QoL. This explanation would argue against an interpretation in favour of a RA personality and only supports the assumption that the identified de- viations in personality characteristics of RA patients compared to healthy people are primarily personality changes due to RA. Interestingly, improved and not improved patients af- ter surgery differ on the same personality characteristics in the same way as the RA patients differ from healthy subjects – namely, a high self-transcendence in the sense of abilities to transcend their boundaries when deeply involved in something or concentrating on the present activity (ST 1) and highly intensive perception and ex- perience of connectedness to the world (ST 2). These self-transcendent skills might enable the patients to be more accepting, better able to cope and to be more satis- fied with their lives than those lacking these abilities. HA as a personality trait reflecting the type or colour of focus and orientation on the world, the ability to deal with uncertainties, strange and unfamiliar situations as well as the overall level of energy was found to be the only substantially predicting variable for ’Psychological health’ as one important domain of QoL after controlling for age, gender and range of motion. This finding was expected because there are many reports in the literature of close relationships between HA and various psycho- pathological manifestations, suggesting a non-specific vulnerable role of HA in relation to psychopathology in general [16]. Interestingly, the QoL domain ’Independ- ence` is substantially predicted by one of the objective indicators implying that the improved movement abili- ties after surgery cause an improved independency in self-care and other general daily living activities. Par- ticular personality characteristics do not increase the prediction of ’Independence. It appears somewhat curious that the QoL ’Environ- ment’ domain is predicted by personality characteristics to the greatest degree; 74% of the variance could be ex- plained and 70% only by personality characteristics in terms of TCI temperament and character domains. This QoL domain integrates several areas of life including the availability of health-care services, possibilities of in- formation and knowledge acquisition, as well as the pos- sibilities of active participation at recreational and lei- sure activities. Even though age and movement abilities are of significant predictive value, a wide range of per- sonality characteristics consisting of NS, RD, PS, CO, and ST is of predictive power; with only HA as less meaningful. The interpretation of the study results is limited by the consecutive nature and the small size of the sample. This might have caused an under-evaluation of findings be- cause of the level of statistical significance. However, well established measurements were applied and the use of two matched general population sample concerning personality measurement can be considered as strength as it allowed a cross-validation of the differences be- tween RA patients and controls to be performed. The combined consideration of objective and subjective in- dicators of surgery outcome and HRQoL can be seen as an additional strength. In summary, RA patients’ QoL can be significantly improved by MP arthroplasty in most cases by improve- ing their movement abilities, despite substantial levels of pain remaining. NS and HA temperament systems of personality seem to play an important role in the adapta- tion process during the long term, chronic illness causing measureable differences compared to general population subjects. However, the character dimension ST repre- sents a tool for coping with the burden of the pain and disability leading to a better experienced QoL after hand- surgery. Finally, personality characteristics are highly predictive of QoL, particularly relating to ‘Environment’ and ‘Psychological Health’ suggesting their important mediating role between experienced pain and disability and HRQoL. REFERENCES [1] Chou, C.Y. and Brauer, D.J. (2005) Temperament and satisfaction with health status among persons with rheu- matoid arthritis. Clinical Nurse Spectrum, 19(3), 94-100. [2] Nagyova, I., Stewart, R.E., Macejova, Z., van Dijk, J.P. and van den Heuvel, W.J. (2005) The impact of pain on psychological well-being in rheumatoid arthritis: The mediating effects of self-esteem and adjustment to dis- ease. Patient Education and Counselling, 58(1), 55-62. [3] Munafò, M.R. and Stevenson, J. (2001) Anxiety and surgical recovery. Reinterpreting the literature. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51(4), 589-596. [4] Anselm, B.M. (1976) Psyche and rheuma. Journal of International Medical Research, 4(Suppl. 2), 50-53. [5] Watson, D. and Clark, L.A. (1984) Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96(3), 465-490. [6] Hamilton, N.A., Zautra, A.J. and Reich, J. (2007) Indi- vidual differences in emotional processing and reactivity to pain among older women with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Journal of Pain, 23(2), 165-172. [7] Dohnke, B., Knäuper, B. and Müller-Fahrnow, W. (2005)  S. Brändström et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1101-1109 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1109 Perceived self-efficacy gained from, and health effects of a rehabilitation program after hip joint replacement. Ar- thritis and Rheumatism, 53(6), 585-592. [8] Weinryb, R.M., Gustavsson, J.P. and Barber, J.P. (2003) Personality traits predicting long-term adjustment after surgery for ulcerative colitis. Journal of Clinical Psy- chology, 59, 1015-1029. [9] Radl, R., Leithner, A., Zacherl, M., Lackner, U., Egger, J. and Windhager, R. (2004) The influence of personality traits on the subjective outcome of operative hallux val- gus correction. International Orthopedics, 28(5), 303- 306. [10] Hyphantis, T.N., Tsifetaki, N., Siafaka, V., Voulgari, P.V., Pappa, C., Bai, M., Palieraki, K., Venetsanopoulou, A., Mavreas, V. and Drosos, A. (2007) The impact of psy- chological functioning upon systemic sclerosis patients’ quality of life. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 37(2), 81-92. [11] Williams, N.W., Penrose, J.M.T. and Hose, D.R. (2000) Computer model analysis of the Swanson and Sutter metacarpophalangeal joint implants. Journal of Hand Surgery, 25(2), 212-220. [12] Blazer, P. E. (1998) Metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty. University of Pennsylvania Orthopaedic Journal, 11, 47-51. [13] Rittmeister, M., Porsch, M., Starker, M. and Kerschbau- mer, F. (1999) Metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: Results of Swanson implants and digital joint operative arthroplasty. Archives of Orthope- dics and Trauma Surgery, 119, 190-194. [14] Squitieri, L. and Chung, K.C.A. (2008) A systematic review of outcomes and complications of vascularized toe joint transfer, silicone arthroplasty, and PyroCarbon arthroplasty for posttraumatic joint reconstruction of the finger. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 121(5), 1697- 1707. [15] Brändström, S., Sigvardsson, S., Nylander, P.-O. and Richter, J. (2008) The Swedish version of the Tempera- ment and Character Inventory (TCI): A cross-validation of age and gender influences. European Journal of Psy- chological Assessment, 24(3), 14-21. [16] Cloninger, C.R., Przybeck, T.R., Svrakic, D.M. and Wet- zel, R.D. (1994) The temperament and character invent- tory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. Center for Psychobiology of Personality Washington University, St.Louis, Missouri. [17] Nordenskiöld, U.M. and Grimby, G. (1992) Grip force in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia and in healthy subjects. A study with the Grippit instrument. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, 22(1), 14-19. [18] Wressle, E., Lindstrand, J., Neher, M., Marcusson, J. and Henriksson, C. (2003) The Canadian Occupational Per- formance Measure as an outcome measure and team tool in a day treatment program. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(10), 497-506. [19] Von Korff, M., Ormel, J., Keefe, F.J. and Dworkin, S.F. (1992) Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain, 50(2), 133-149. [20] Dasch, B., Endres, H.G., Maier, C., Lungenhausen, M., Smektala, R., Trampisch, H.J. and Pientka, L. (2008) Fracture-related hip pain in elderly patients with proxi- mal femoral fracture after discharge from stationary treatment. European Journal of Pain, 12(2), 149-156. [21] Sieben, J.M., Vlaeyen, J.W., Portegijs, P.J., Verbunt, J.A., van Riet-Rutgers, S., Kester, A.D., Von Korff , M., Arntz, A. and Knottnerus, J.A. (2005) A longitudinal study on the predictive validity of the fear-avoidance model in low back pain. Pain, 117(1-2), 162-170. [22] WHOQOL Group. (1998) The World Health Organiza- tion Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL) Develop- ment and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine, 46(12), 1569-1585. [23] Noerholm, V. and Bech, P. (2001) The WHO Quality of Life (WHOQOL) questionnaire: Danish validation study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 55(4), 229-235. [24] Escott, B.G., Ronald, K., Judd, M.G. and Bogoch, E.R. (2010) NeuFlex and Swanson metacarpophalangeal im- plants for rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective randomized, controlled clinical trial. Journal of Hand Surgery, 35(1), 44-51. [25] Chung, K.C., Burns, P.B., Wilgis, E.F., Burke, F.D., Regan, M, Kim, H.M. and Fox, D.A. (2009) A multicenter trial in rheumatoid arthritis comparing silicone metacarpo- phalangeal joint arthroplasty with medical treatment. Journal of Hand Surgery, 34(5), 815-823. [26] Chung, K.C., Kotsis, S.V., Wilgis, E.F., Fox, D.A., Regan, M, Kim, H.M. and Burke, F.D. (2009) A multicenter trial in rheumatoid arthritis comparing silicone metacarpopha- langeal joint arthroplasty with medical treatment. Journal of Hand Surgery, 34, 734-747. [27] Massy-Westropp, N., Johnston, R.V. and Hill, C. (2008) Post-operative therapy for metacarpophalangeal arthro- plasty. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1. [28] Colville, R.J., Nicholson, K.S. and Belcher, H.J. (1999) Hand surgery and quality of life. Journal of Hand Sur- gery, 24(3), 263-266. List of Abbreviations CO Cooperativeness COPM Canadian Occupational Performance Measure GCPS Grade Chronic Pain Status HA Harm Avoidance HRQoL health Related Quality of Life MP Metacarpophalangeal NS Novelty Seeking PS Persistence QoL Quality of Life RA Rheumatoid Arthritis RD Reward Dependence SD Self-Directedness ST Self-Transcendence TCI Temperament and Character Inventory VAS Visual Analogue Scale |