Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

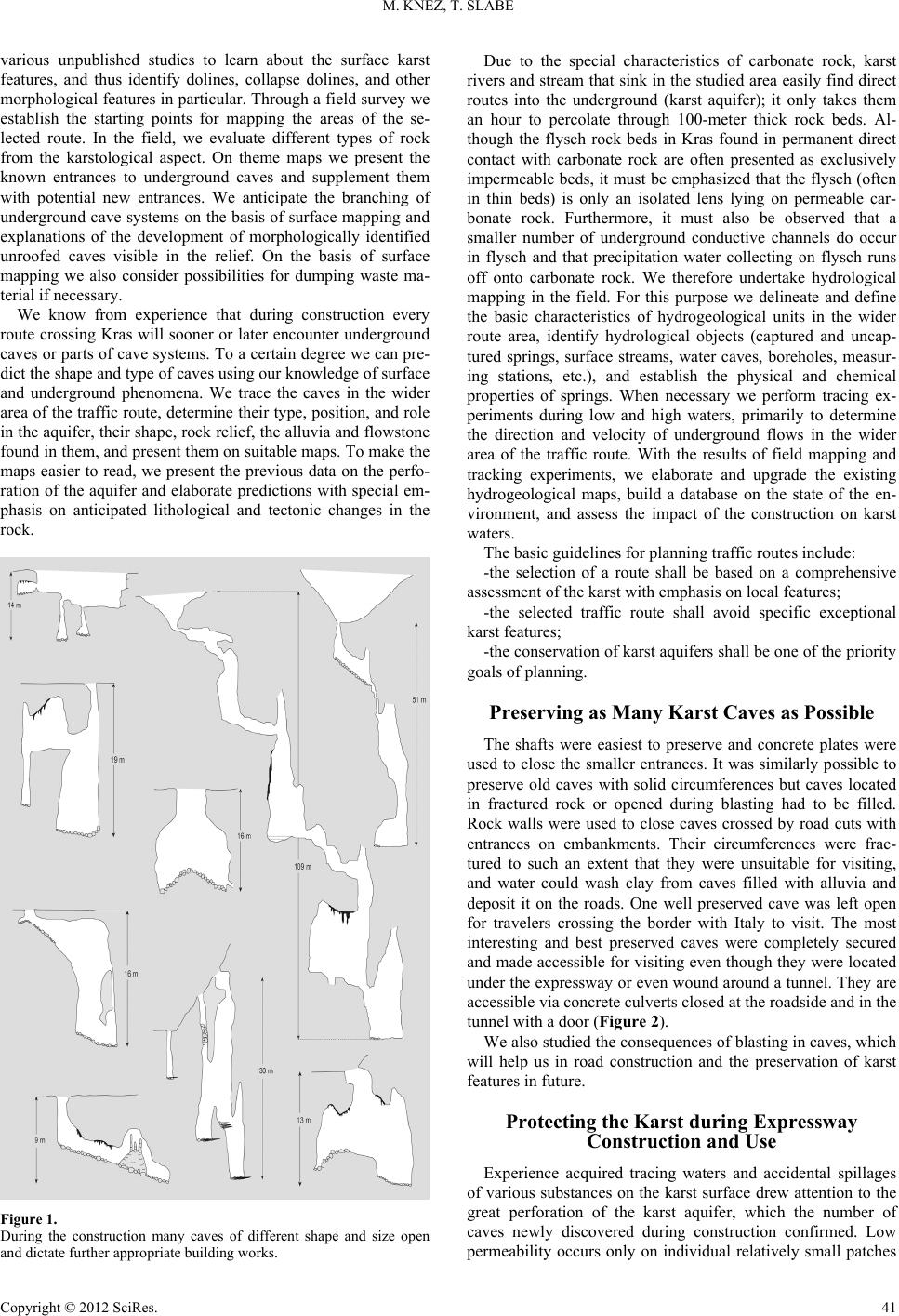

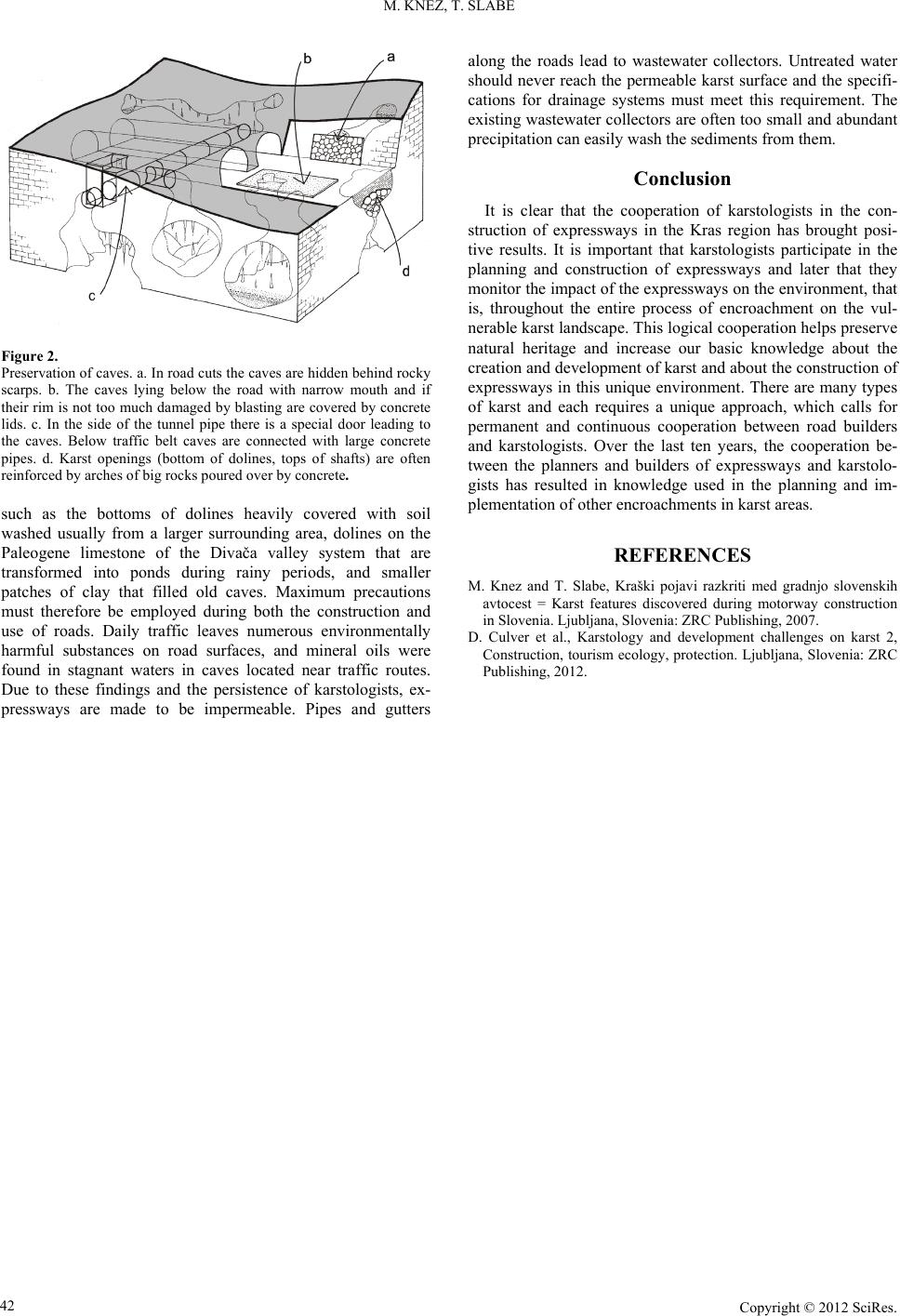

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, Supplement, 39-42 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) DOI:10.4236/ce.2012.37B009 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 39 Planning, Research and Karstological Monitoring of Expressways Crossing Classical Karst (Slovenia) Martin Knez, Tadej Slabe Karst Research Institute, Scientific Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Postojna, Slovenia Email: knez@zrc-sazu.si Received 2012 Over the last fifteen years the construction of modern expressways in Slovenia has been one of the major construction projects aimed at connecting important parts of the country and opening them to Europe. Almost half of Slovenia is karst and more than half of the water for the supply of the population comes from karst aquifers. Slovenia is home to the classical karst region of Kras that gave its name for this unique carbonate rock landscape to numerous world languages and is also the cradle of karstology. We need to better understand this fragile karst landscape and do everything to preserve it since it is an impor- tant part of our natural and cultural heritage. Keywords: Expressways Planning; Karstological Monitoring; Karst Protection; Classical Karst; Slovenia Introduction Special attention is devoted to Kras, a karst plateau rising above the northwesternmost part of the Adriatic Sea that is bordered on the southwest by a vast flysch area with ele vations exceeding 600 meters. Lying between 200 and 500 meters above sea level, the plateau covers 440 square kilometers and in a broad sense belongs to the Outer Dinaric Alps. From the viewpoint of the theory of tectonic plates, the plateau lies at the northern deformed edge of the Adriatic plate and is the result of tectonic overlapping. Only Cretaceous and Paleogenic rocks are found here. They are characterized by exceptionally varied limestone that mostly formed in relatively shallow sedimenta- tion basins with lush fauna and flora. On the Kras plateau there are no remains of the surface waters used in the past to explain the development of the plateau. Originally, the plateau was surrounded and covered with flysch and therefore flooded. Vertica l pe rcol ati on wa s mini mal. The wat e r tabl e late r dropped several hundred meters into the karst. At the contact between the carbonate rock and flysch, surface waters created characte- ristic and extensive contact karst. Today, all Kras rivers sink where they flow from flysch onto limestone bedrock and flow underground toward the springs of the Timava River in Italy. The largest stream is the Reka River, which sinks in the Škocjan Caves, while 65% percent of the water sinks from the surface in a dispersed fashion. From the ecological standpoint, Kras has one of the most vulnerable natural systems in Slove- nia. The low karst of the Dolenjska region is mostly covered with a variety of alluvia under which a unique karst surface formed with stone forests as one of its most distinctive features. The water table is often just below the surface, and the valley sys- tems are occasionally flooded. Karst areas also developed in the breccias that formed from the scree on the slopes of Mount Nanos. They lie on more or less permeable flysch, and water flowing at the contact carved the largest caves in this area. For a number of years, karstologists have cooperated in the planning and construction of expressways in the Kras region [1, 2]. In the selection of expressway and railway routes, the main consideration is the integrity of the karst landscape and there- fore the routes chosen avoid the more important surface karst features (dolines, poljes, collapse dolines, karst walls) and al- ready known caves. Special attention is devoted to the impact of the construction and use of expressways on karst waters. Expressways should therefore be impermeable so that runoff water from the road is first gathered in oil collectors and then released clean onto the karst surface. We studied the impact of traffic routes on karst waters and determined the contents of polluted water flowing daily from the expressways. Small quantities of stagnant water found in caves along the expressways contained traces of mineral oils. During the construction of expressways we also perform karstological monitoring. We study newly revealed karst phe- nomena as an important part of our natural heritage and advise on how to preserve them if the construction work allows it. At the same time our new findings are of great help to the con- struction companies. We have acquired a number of new find- ings on the formation and development of the karst surface, epikarst, and the perforation of the aquifer. Exploring the Karst Surface and New Caves during Expresswa y Constructio n The removal of soil and vegetation from the karst surf a ce a nd of course major earthworks such as the excavation of cuts and tunnels reveal surface, epikarst, and subsoil karst features. Our task is to study these features as part of the natural heritage, advise on how to preserve them, and of course share our new findings with the builders. These findings are used to overcome construction obstacles. The karst surface is dissected by dolines and unroofed caves. Dolines are a sign of the current shaping of the surface by pre- cipitation water that percolates vertically through it and passes  M. KNEZ, T. SLABE Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 40 through the vadose part of the aquifer to the underground water. Some dolines are more distinctly filled with soil than others. There are shafts and fissures at their bottoms through which water flows. The soil must be removed from the dolines and their bottoms reinforced with rocks arranged in a vault-like pattern; the mouths of shafts are often smaller than the cham- bers beneath them. The dolines are then filled with layers of rubble. Unroofed caves have a similar form or are more oblong. These are old caves that appear on the surface due to the lo- wering of the karst surface and no longer have the upper part of their circumference. The fine-grained fill, in this case old cave alluvia, must be removed and replaced with rocks and rubble. Otherwise, water could gradually carry the alluvia away and cause subsidence on the surface. The epikarst is crisscrossed with fissures that are more dis- tinctive in Cretaceous limestone and less so in Paleogenic li- mestone, and many of them open at the bottoms and slopes of dolines. In most cases they are filled with soil and their walls are dissected with subsoil rock relief forms. Due to the lower- ing of the karst surface, many shafts are now located just below the surface. More than 350 caves were opened on the 70-kilometer sec- tion of expressway built in Kras in the last few years. Relative to the development of the aquifer, we distinguish between old caves through which watercourses flowed when the karst aqui- fer was surrounded and covered by flysch and shafts through which water vertically percolates from the permeable karst surface to the underground water. The deepest shaft found measured 109 meters. Some old caves are empty, almost two thirds of them are filled with alluvia, and one third are unroofed caves. Caves are opened when vegetation and soil is removed from the surface, and a large number of caves were opened during the excavation of cuts. Blasting caused their roofs to collapse, and cross sections of passages were preserved in embankments. The most shafts were opened at the bottoms of dolines when the soil and alluvia were removed. We studied all the caves, drew their plans, determined their shape, examined the rock relief, collected samples of alluvia for paleomagnetic and pollen analyses, and sampled flowstone for mineralogical analyses and age determination. We extrapolated the further extent of the caves on the basis of their shapes and the geological conditions, which is especially useful for road builders. Studies that Accompanied Construction Produced New Findings on Karst Development The unroofed cave is a special and frequent karst form. To- day, this significant karst surface feature is a familiar pheno- menon, but it had not been thoroughly studied before the con- struction of the expressway across Kras. Great attention has been devoted to unroofed caves since the occurrence of this phenomena turned out to be considerably higher than previous- ly expected, and numerous articles on unroofed caves and the construction of new expressways are now available. The shape of an unroofed caves is the consequence of the type and shape of the cave and the development of the karst aquifer and its surface in various geological, geomorphological, climate, and hydrological conditions. The distinctiveness of the surface shape of an unroofed cave is dictated by the speed at which the alluvium was washed out of the cave relative to the lowering of the surrounding surface. If the speed was low, we can often see soil and vegetation or areas of alluvium and flowstone on the surface; where it was faster, unroofed caves on the karst surface resemble dolines, a string of dolines, or oblong depressions. Frequently they are an interweaving of various old forms such as caves and recent shaping of the karst with dolines and shafts. A large proportion of the caves were filled with alluvia, in most cases fine-grained flysch alluvia with intervening layers of gravel. We took alluvia samples for paleomagnetic research from caves at Kozina and Divača and determined they origi- nated in the Olduvai period. We therefore concluded that the caves were filled after the Messinian crisis approximately 5.2 million years ago. In short, unroofed caves are an increasingly recognized fea- ture of the karst surface, an important part of the epikarst, and an exceptional trace of the development of the karst aquifer. Determining the age of the alluvia helps us understand the oldest periods of karstification and has proven that the oldest caves in Kras are much older than earlier karstologists thought. Planning Road Construction Before construction starts we verify the accuracy of known data about caves in the field and add possible new measure- ments and explanations of their development. To throw light on the situation we present existing data on perforation of the aquifer and elaborate prognosis subsurface maps with special emphasis on the anticipated lithological and tectonic change s in rock composition and structure. Before the start of construction work we try to present the perforation of the karst as accurately as possible. We can determine the position of underground caves by drilling, and along with measurement indicators we also determine the type of potential fill material (flowstone, alluvia). To a certain extent we can anticipate the shape, type, and occurrence of caves in the vicinity using our knowledge of the known surface and underground features. Perforation (Figure 1) puts a special stamp on the construc- tion of expressways in the Kras region. In addition to its varied development, Slovenia’s karst is marked by tectonic and litho- stratigraphic diversity and it is therefore difficult to determine in advance where caves will occur. As a rule, caves occur more frequently along the contacts of flysch with limestone. The perforation of the karst aquifer is therefore determined primari- ly on the basis of good and comprehensive knowledge of the karst and continuous intensive work in planning and construct- ing the expressways. When planning expressways, the link between surface and underground karst features requires the karstological evaluation of the karst surface as well as the karst underground, the hy- drological situation, and the presented variables. On all the expressway construction sites in Kras we encountered numer- ous karst phenomena including dolines, filled and empty caves, and sections of old and current drainage systems through the karst. The lowering of the karst surface exposed many karst caves that are now visible in the Kras region. In recent years, we have focused on unroofed caves “discovered” during the construction of expressways. We are certain that a quality karstological study of the area where a road is planned enables the better selection of a route and is one of the basic starting points for planning expressway construction in this unique and vulnerable landscape. We begin by assembling published literature, archives, and  M. KNEZ, T. SLABE Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 41 various unpublished studies to learn about the surface karst features, and thus identify dolines, collapse dolines, and other morphological features in particular. Through a field survey we establish the starting points for mapping the areas of the se- lected route. In the field, we evaluate different types of rock from the karstological aspect. On theme maps we present the known entrances to underground caves and supplement them with potential new entrances. We anticipate the branching of underground cave systems on the basis of surface mapping and explanations of the development of morphologically identified unroofed caves visible in the relief. On the basis of surface mapping we also consider possibilities for dumping waste ma- terial if nec es sary. We know from experience that during construction every route crossing Kras will sooner or later encounter underground caves or parts of cave systems. To a certain degree we can pre- dict the shape and type of caves using our knowledge of surface and underground phenomena. We trace the caves in the wider area of the traffic route, determine their type, position, and role in the aquifer, their shape, rock relief, the alluvia and flowstone found in them, and present them on suitable maps. To make the maps easier to read, we present the previous data on the perfo- ration of the aquifer and elaborate predictions with special em- phasis on anticipated lithological and tectonic changes in the rock. Figure 1. During the construction many caves of different shape and size open and dictate further appropriate building works. Due to the special characteristics of carbonate rock, karst rivers and stream that sink in the studied area easily find direct routes into the underground (karst aquifer); it only takes them an hour to percolate through 100-meter thick rock beds. Al- though the flysch rock beds in Kras found in permanent direct contact with carbonate rock are often presented as exclusively impermea ble beds, it must be empha sized that the fly sch (often in thin beds) is only an isolated lens lying on permeable car- bonate rock. Furthermore, it must also be observed that a smaller number of underground conductive channels do occur in flysch and that precipitation water collecting on flysch runs off onto carbonate rock. We therefore undertake hydrological mapping in the field. For this purpose we delineate and define the basic characteristics of hydrogeological units in the wider route area, identify hydrological objects (captured and uncap- tured springs, surface streams, water caves, boreholes, measur- ing stations, etc.), and establish the physical and chemical properties of springs. When necessary we perform tracing ex- periments during low and high waters, primarily to determine the direction and velocity of underground flows in the wider area of the traffic route. With the results of field mapping and tracking experiments, we elaborate and upgrade the existing hydrogeological maps, build a database on the state of the en- vironment, and assess the impact of the construction on karst waters. The basic guidelines for planning traffic routes include: -the selection of a route shall be based on a comprehensive assessment of the karst with emphasis on local features; -the selected traffic route shall avoid specific exceptional karst features; -the conservation of karst aquifers shall be one of the priority goals of planning. Preserving as Many Karst Caves as Possible The shafts were easiest to preserve and concrete plates were used to close the smaller entrances. It was similarly possible to preserve old caves with solid circumferences but caves located in fractured rock or opened during blasting had to be filled. Rock walls were used to close caves crossed by road cuts with entrances on embankments. Their circumferences were frac- tured to such an extent that they were unsuitable for visiting, and water could wash clay from caves filled with alluvia and deposit it on the roads. One well preserved cave was left open for travelers crossing the border with Italy to visit. The most interesting and best preserved caves were completely secured and made accessible for visiting even though they were loca ted under the expressway or even wound around a tunnel. They are accessible via concrete culverts closed at the roadside and in the tunnel with a door (Figure 2). We also studied the consequences of blasting in caves, which will help us in road construction and the preservation of karst features in future. Protecting the Karst during Expressway Construction and Use Experience acquired tracing waters and accidental spillages of various substances on the karst surface drew attention to the great perforation of the karst aquifer, which the number of caves newly discovered during construction confirmed. Low permeability occurs only on individual relatively small patches  M. KNEZ, T. SLABE Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 42 Figure 2. Preservation of caves. a. In ro ad cuts th e caves are hidden behind rocky scarps. b. The caves lying below the road with narrow mouth and if their rim is not too much damaged by blasting a re covered by concrete lids. c. In the side of the tunnel pipe there is a special door leading to the caves. Below traffic belt caves are connected with large concrete pipes. d. Karst openings (bottom of dolines, tops of shafts) are often reinforced by arches of big rocks poured over by concrete. such as the bottoms of dolines heavily covered with soil washed usually from a larger surrounding area, dolines on the Paleogene limestone of the Divača valley system that are transformed into ponds during rainy periods, and smaller patches of clay that filled old caves. Maximum precautions must therefore be employed during both the construction and use of roads. Daily traffic leaves numerous environmentally harmful substances on road surfaces, and mineral oils were found in stagnant waters in caves located near traffic routes. Due to these findings and the persistence of karstologists, ex- pressways are made to be impermeable. Pipes and gutters along the roads lead to wastewater collectors. Untreated water should never reach the permeable karst surface and the specifi- cations for drainage systems must meet this requirement. The existing wastewater collectors are often too small and abundant precipitation can easily wash the sediments from them. Conclusion It is clear that the cooperation of karstologists in the con- struction of expressways in the Kras region has brought posi- tive results. It is important that karstologists participate in the planning and construction of expressways and later that they monitor the impact of the expressways on the environment, that is, throughout the entire process of encroachment on the vul- nerable karst landscape. This logical cooperation helps preserve natural heritage and increase our basic knowledge about the creation and development of karst and about the construction of expressways in this unique environment. There are many types of karst and each requires a unique approach, which calls for permanent and continuous cooperation between road builders and karstologists. Over the last ten years, the cooperation be- tween the planners and builders of expressways and karstolo- gists has resulted in knowledge used in the planning and im- plementation of other encroachments in karst areas. REFERENCES M. Knez and T. Slabe, Kraški pojavi razkriti med gradnjo slovenskih avtocest = Karst features discovered during motorway construction in Slovenia. Ljubljana, Slovenia: ZRC Publishing, 2007. D. Culver et al., Karstology and development challenges on karst 2, Construction, touris m ecology, protection . Ljubljana, Slovenia: ZRC Publishing, 2012. |