Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

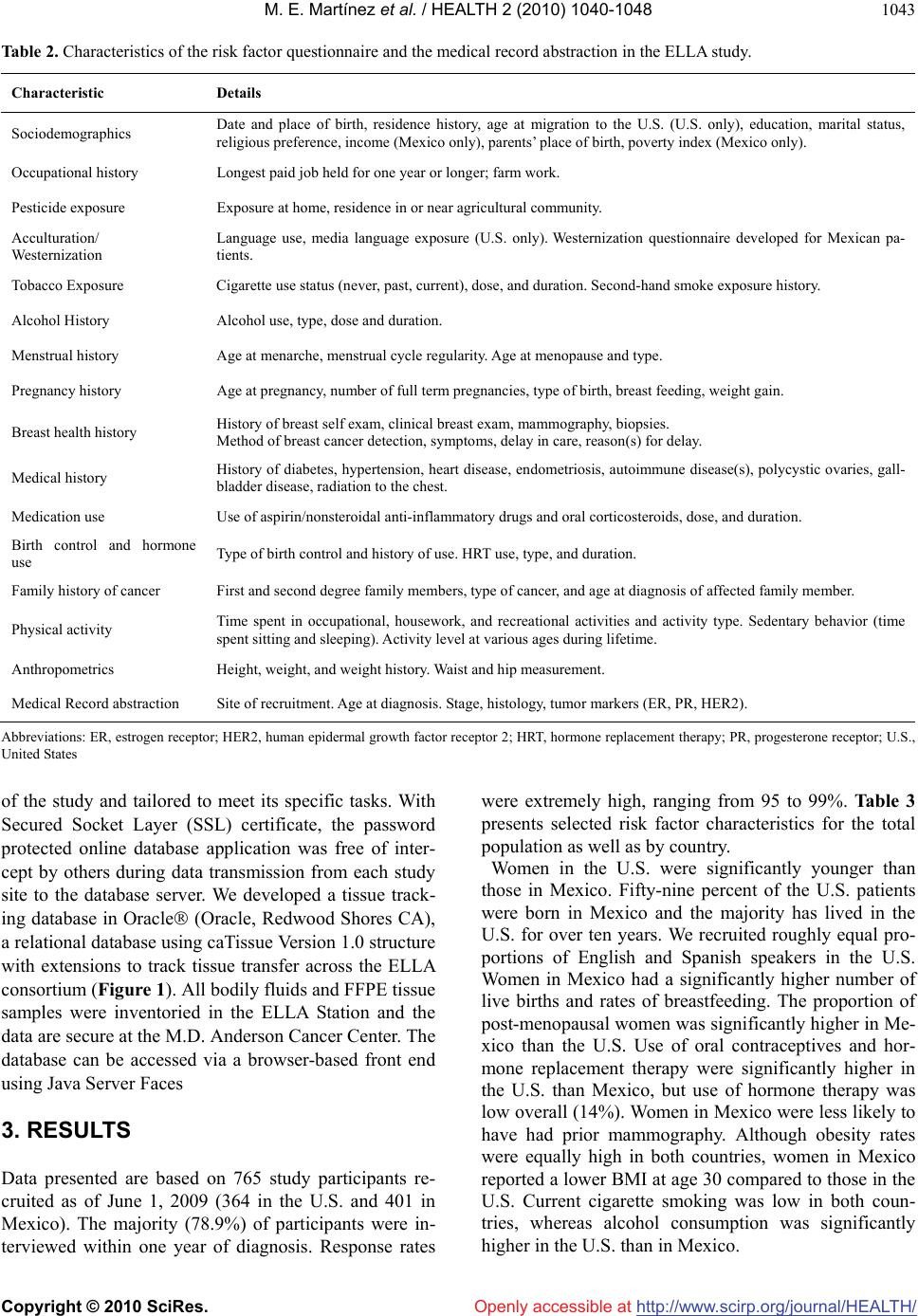

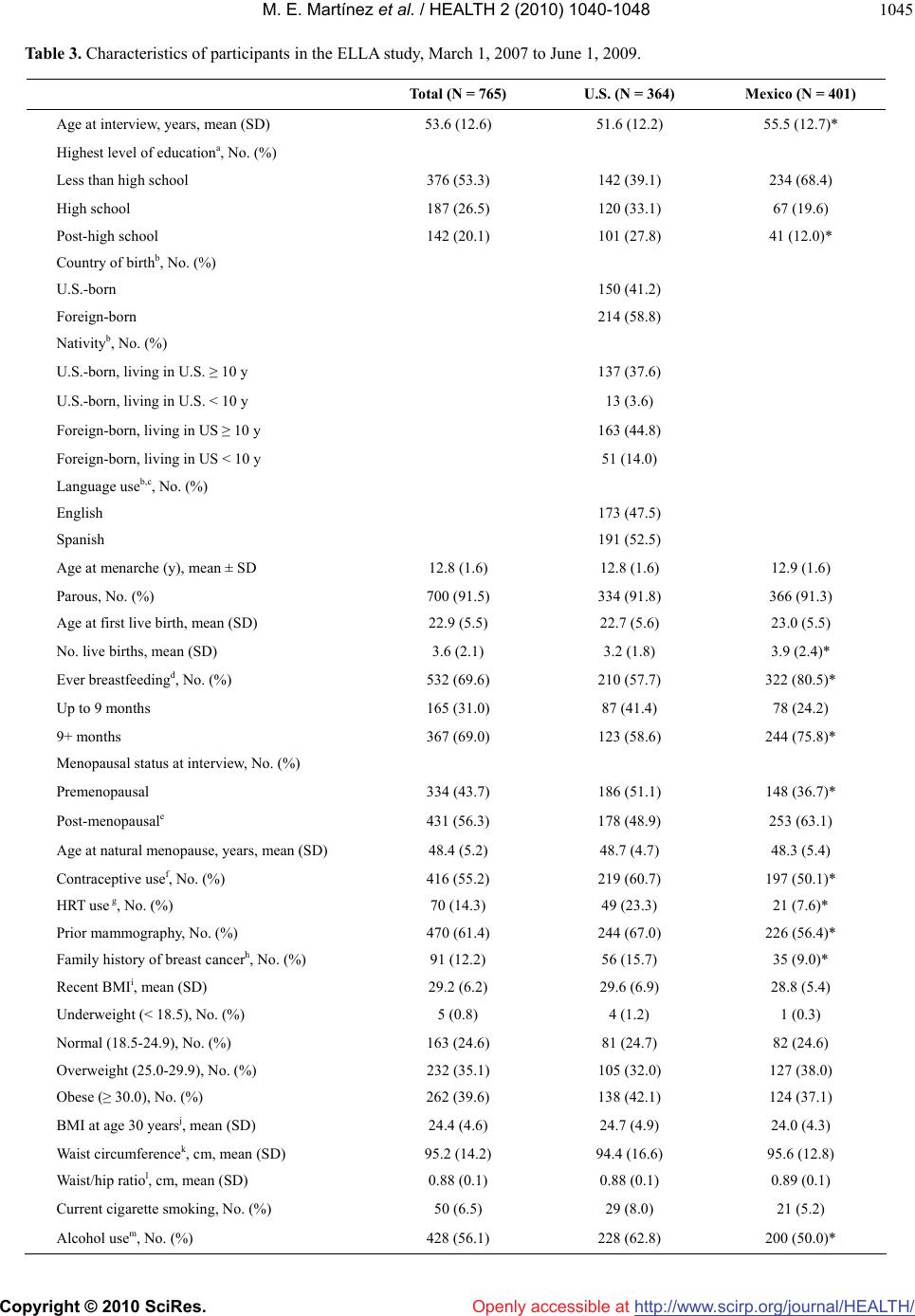

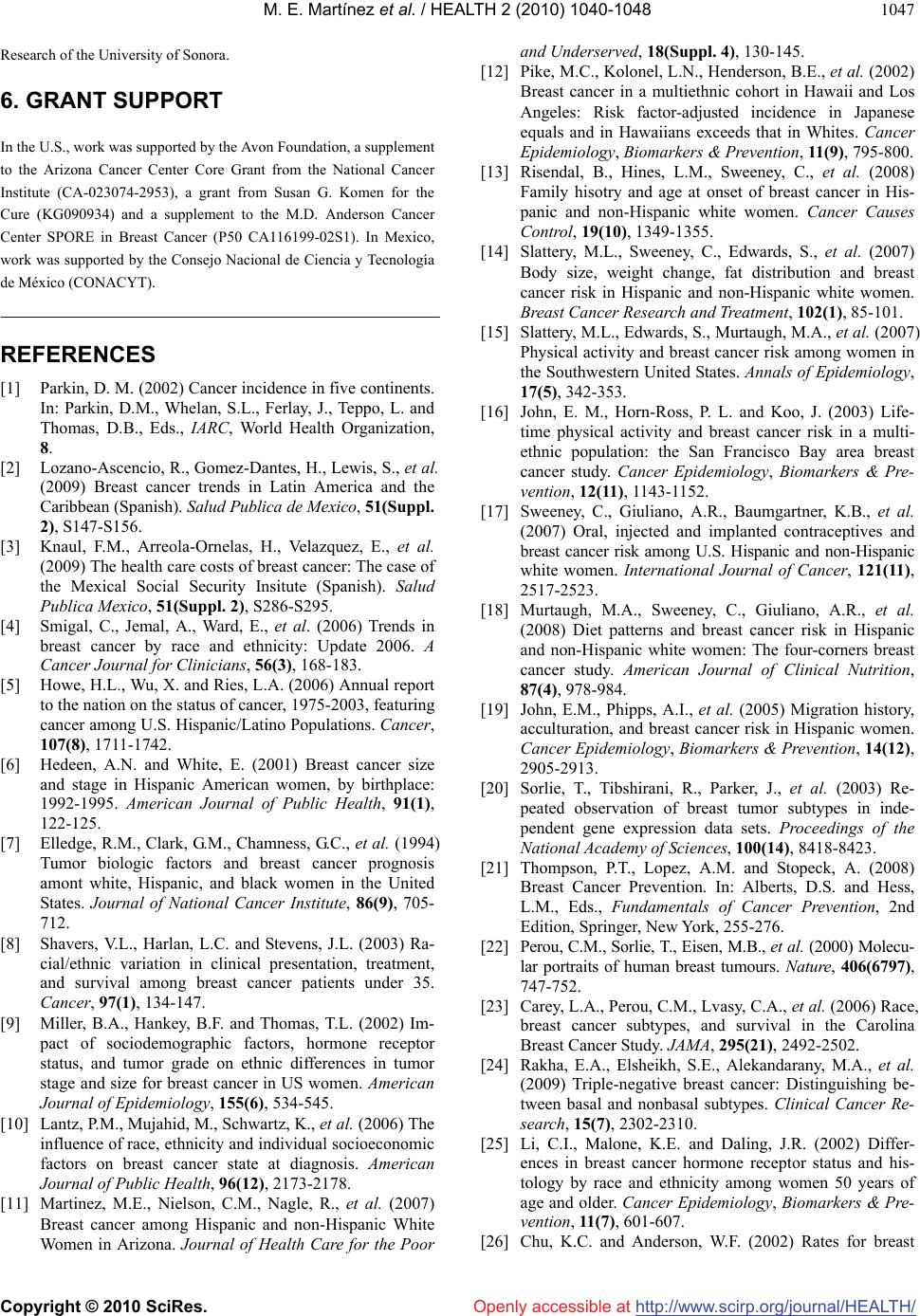

Vol.2, No.9, 1040-1048 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.29153 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Comparative study of breast cancer in Mexican and Mexican-American women María Elena Martínez1*, Luis Enrique Gutiérrez-Millan2, Melissa Bondy3, Adrian Daneri-Navarro4, María Mercedes Meza-Montenegro5, Ivan Anduro-Corona2, Ma Isabel Aramburo-Rubio6, Luz María Adriana Balderas-Peña7, José Adelfo Barragan-Ruiz7, Abenaa Brewster3, Graciela Caire-Juvera8, Juan Manuel Castro-Cervantes7, Mario Alberto Chávez Zamudio9, Giovanna Cruz1, Alicia Del Toro-Arreola4, Mary E. Edgerton3, María Rosa Flores-Marquez7, Ramon Antonio Franco-Topete10, Helga Garcia5, Susan Andrea Gutierrez-Rubio4, Karin Hahn3, Luz Margarita Jimenez-Perez11, Ian K. Komenaka12, Zoila Arelí López Bujanda2, Dihui Lu13, Gilberto Morgan-Villela7, James L. Murray3, Jesse N. Nodora14, Antonio Oceguera-Villanueva15, Miguel Angel Ortiz Martínez13, Laura Pérez Michel13, Antonio Quintero-Ramos9, Aysegul Sahin3, Jeong Yun Shim3, Maureen Stewart3, Gonzalo Vazquez-Camacho7, Betsy Wertheim1, Rachel Zenuk1, Patricia Thompson1 1Arizona Cancer Center and Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA; *Corresponding Author: emartinez@azcc.arizona.edu 2Departamento de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, México 3University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, USA 4Departamento de Fisiología, Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México 5Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora, Ciudad Obregón, México 6Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Hermosillo, México 7Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, CMNO, Guadalajara, Jalisco 8Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, Hermosillo, México 9Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Ciudad Obregón, México 10OPD Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México 11Departamento de Salud Pública, Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México 12Maricopa Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Phoenix, USA 13University of North Carolina, Lineberger Cancer Center, Chapel Hill, USA 14Arizona Cancer Center and Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA 15Instituto Jalisciense de Cancerología, Guadalajara, México Received 25 March 2010; revised 5 May 2010; accepted 7 May 2010. ABSTRACT Breast cancer is the number one cause of can- cer deaths among Hispanic women in the United States, and in Mexico, it recently became the primary cause of cancer deaths. This malign- nancy represents a poorly understood and un- derstudied disease in Hispanic women. The ELLA Binational Breast Cancer Study was es- tablished in 2006 as a multi-center study to as- sess patterns of breast tumor markers, clinical characteristics, and their risk factors in women of Mexican descent. We describe the design and implementation of the ELLA Study and provide a risk factor comparison between women in the U.S. and those in Mexico based on a sample of 765 patients (364 in the U.S. and 401 in Mexico). Compared to women in Mexico, U.S. women had significantly (p < 0.05) lower parity (3.2 vs. 3.9 mean live births) and breastfeeding rates (57.5% vs. 80.5%), higher use of oral contraceptives (60.7% vs. 50.1%) and hormone replacement therapy (23.3% vs. 7.6%), and higher family history of breast cancer (15.7% vs. 9.0%). Re- sults show that differences in breast cancer risk factor patterns exist between Mexico and U.S. women. We provide lessons learned from the conduct of our study. Binational studies are an important step in understanding disease pat- terns and etiology for women in both countries.  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1040-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1041 Keywords: Binational Study; Breast Cancer; Hispanics; Mexico; United States 1. INTRODUCTION Rates of breast cancer in more developed nations have in the past exceeded those in lower-income countries by a factor of five or more [1]. In Mexico, the breast cancer mortality rate has increased by 84% over the last two decades [2,3] and it is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in Mexico [3]. In the United States (U.S.), age-adjusted breast cancer incidence differs sig- nificantly among racial/ethnic groups; rates are higher among non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) and lower among racial/ethnic minorities, including Hispanics [4]. Despite their lower breast cancer incidence rates, Hispanic women are 22% more likely to die of this disease [5]. Published data [6-10], including our own studies in Arizona [11], indicate that Hispanic women present with breast cancer at an earlier age and with larger, more advanced stage disease of higher grade, a profile similar to that observed for African-American women. Relative to other racial/ ethnic groups, few epidemiological studies that focus on breast cancer in Hispanic women have been conducted to date. Published reports have provided data on the role of reproductive factors [12,13], body size and obesity [14], physical activity [15,16], contraceptive use [12,17], diet [18], family history [13], and migration history [12, 19], in relation to breast cancer risk in Hispanic women in the U.S. It is now generally accepted that breast tumors exhibit heterogeneity derived from intrinsic molecular differ- ences that influence their natural history and response to treatment [20]. A number of studies have shown that steroid hormone dependent tumors differ with respect to their biology and their risk factors [21] and that these differences are clinically relevant in terms of treatment selection, response, and patient prognosis [22-24]. In spite of the importance of characterization of breast cancer disease subtypes, no published data exist on the prevalence of the tumor subtypes, such as luminal and basal-like breast tumors in Hispanic women in the U.S. Results of the few population-based studies published to date [25-27], including our own [11], suggest that His- panic women with breast cancer are more likely to be diagnosed with hormone receptor negative tumors and those that do not express human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), compared to NHWs [28,29]. Reasons for breast cancer disparities in Hispanic women likely result from a combination of factors including poor access to health care, less use of mammography screening, genetic susceptibility, and environmental or cultural factors. While there is increasing scrutiny of the validity and theoretical basis of acculturation measures [30-32], adequate and nuanced measurement of accultu- ration could allow for the identification of variables linked to risk-enhancing or protective behaviors associa- ted with breast cancer and its subtypes. The ELLA Binational Breast Cancer Study (hereafter referred to as the ELLA Study) was established to compare risk factor patterns, disease phenotypes, and clinical characteristics between the U.S. and Mexico populations. We hypothesized that the distribution of breast tumor subsets differs between women in Mexico and Mexican-American women residing in the U.S. and that these differences are related to reproductive and lifestyle factor profiles indicative of U.S. lifestyle and cultural influences. Here we describe the design and implementation of this binational study and provide a comparison of risk factor characteristics between the two countries. 2. METHODS 2.1. Study Design and Recruitment The ELLA Study was initiated in 2006 as a pilot effort with the formation of a binational investigative team, comprising three sites in Mexico (Universidad de Gua- dalajara in Guadalajara, Jalisco; Universidad de Sonora in Hermosillo, Sonora; and Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora in Ciudad Obregón, Sonora) and two sites in the U.S. (Arizona Cancer Center, in Tucson, Arizona, which included recruitment sites throughout the state; and at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, which included two additional recruit- ment sites) (See Table 1). An essential component of the ELLA study was the partnership with clinicians and pathologists from health care settings serving the study participants both in Mexico and the U.S. Health care providers included those from Mexico’s nationalized health care system: the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in all three sites and the Hospital Civil and Instituto Jaliscience de Cancerología in Guadalajara. The study was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards, including the IMSS. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. Participants were eligible if they were diagnosed within 24 months of recruitment with invasive breast cancer and were 18 years of age or older. In the U.S., par- ticipants were self-identified as being of Mexican descent. Women with carcinoma in situ and those with recurrent disease were ineligible. A clinic-based approach was the dominant strategy used for recruitment in the study, although the number of recruitment sites and their tactics  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1041-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1042 of identifying patients differed by region (see Table 1). 2.2. Data Collection Participation involved in-person (93%) or telephone ad- ministration (7%) of a risk factor questionnaire. Three comparable questionnaires were created: English and Spanish versions for the U.S. and a separate instrument for Mexico. No differences existed between the two U.S. versions and only minor differences between the U.S. and Mexico questionnaires (see Table 2). All study personnel were jointly trained prior to the initiation of recruitment and continue to receive training as needed. The instrument takes a median of 45.0 min- utes to administer (59.0 minutes for Mexico and 43.2 minutes for the U.S.). As part of data collection, we abstracted the medical records for clinical and histopathological factors, includ- ing predictive and prognostic factors. It is important to note that ER, PR, and HER2 are not uniformly con- ducted in all IMSS institutions in Mexico; marker status is not conducted at all in the Hospital Civil or the Insti- tuto Jaliscience de Cancerología. The Avon Foundation, one of the study’s sponsors, provided additional funding for the breast cancer patients to have consistent tumor marker information that is important for their treatment course. Figure 1 presents the operational structure of the ELLA Study. The organizational structure includes the five recruitment sites, the research core elements, and the Steering and Advisory Committees. Recruitment, data collection, tissue collection, and DNA extraction are conducted at each site. 2.3. Biological Samples An essential component of the ELLA Study was the routine collection of formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tissue including biopsy sample for patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy. FFPE tissue samples were sent to M.D. Anderson Cancer Center for the construction of tissue microarrays (TMAs) (Figure 1). The markers being evaluated in the TMAs were selected to characterize basal and luminal subtypes (ER, PR, and HER2, Ki67, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and basal cytokeratins [CK5 or 6, CK14 and CK17]) for subset delineation by immunohistochemistry as described by Nielsen et al. [33]. Prior to initiation of the ELLA recruitment, special trainings were conducted at Ventana Medical Systems (Tucson, Arizona) that in- cluded all Mexico pathologists involved in the study. To assure uniformity of tumor marker measures of diagno- stic value across community and international laborato- ries, ER, PR, HER2, and Ki67 analyses were repeated on all tumor samples at Ventana Medical Systems with auto- mation and intra- and inter-batch control. We do not present clinical characteristics or marker data due to their premature nature as data derived from Mexico will need to undergo quality control verification. Figure 1 also shows the establishment of a deoxyribo- nucleic acid (DNA) repository with the collection of blood or saliva on all participants. DNA was extracted at each recruitment site from saliva according to manufac- turer instruction for the Oragene saliva kit (DNA Genotek©, Ontario Canada) or from blood using the QIAmp Mini Kit (Qiagen©, Valencia CA). A single DNA aliquot was then sent to the Arizona Cancer Center for study banking with each site retaining the remainder of their study DNA. 2.4. Data Management and Tissue Tracking Data management supporting the risk factor question- naire and medical record abstraction for the ELLA Study was centralized at the Arizona Cancer Center. We de- veloped web-based databases built with two well-establi- shed open-source software systems, providing the capac- ity to allow access from anywhere via the Internet. Da- tabase applications were built around the individual needs Table 1. Recruitment sites in the ELLA study, March 1, 2007 to June 1, 2009. Region Recruitment Sites Arizona (United States) Arizona Cancer Center (Tucson); St. Elizabeth of Hungary Clinic (Tucson); University Physician’s Healthcare Kino Hospital (Tucson); El Rio Community Health Center (Tucson); Arizona Oncology (Tucson); Maricopa Integrated Health System (Phoenix); Mountain Park Community Health Center (Phoenix); Dr. Edward Donahue (Phoenix); Arizona Oncology (Phoenix); Mariposa Community Health Center (Nogales); Regional Center for Border Health (Yuma). Houston, Texas (United States) M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital; The Rose Diagnostic Clinic. Guadalajara, Jalisco (Mexico) Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social; OPD Hospital Civil de Guadalajara; Instituto Jaliscience de Cancerología. Ciudad Obregon, Sonora (Mexico) Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Hermosillo, Sonora (Mexico) Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social.  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1040-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1043 Table 2. Characteristics of the risk factor questionnaire and the medical record abstraction in the ELLA study. Characteristic Details Sociodemographics Date and place of birth, residence history, age at migration to the U.S. (U.S. only), education, marital status, religious preference, income (Mexico only), parents’ place of birth, poverty index (Mexico only). Occupational history Longest paid job held for one year or longer; farm work. Pesticide exposure Exposure at home, residence in or near agricultural community. Acculturation/ Westernization Language use, media language exposure (U.S. only). Westernization questionnaire developed for Mexican pa- tients. Tobacco Exposure Cigarette use status (never, past, current), dose, and duration. Second-hand smoke exposure history. Alcohol History Alcohol use, type, dose and duration. Menstrual history Age at menarche, menstrual cycle regularity. Age at menopause and type. Pregnancy history Age at pregnancy, number of full term pregnancies, type of birth, breast feeding, weight gain. Breast health history History of breast self exam, clinical breast exam, mammography, biopsies. Method of breast cancer detection, symptoms, delay in care, reason(s) for delay. Medical history History of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, endometriosis, autoimmune disease(s), polycystic ovaries, gall- bladder disease, radiation to the chest. Medication use Use of aspirin/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral corticosteroids, dose, and duration. Birth control and hormone use Type of birth control and history of use. HRT use, type, and duration. Family history of cancer First and second degree family members, type of cancer, and age at diagnosis of affected family member. Physical activity Time spent in occupational, housework, and recreational activities and activity type. Sedentary behavior (time spent sitting and sleeping). Activity level at various ages during lifetime. Anthropometrics Height, weight, and weight history. Waist and hip measurement. Medical Record abstraction Site of recruitment. Age at diagnosis. Stage, histology, tumor markers (ER, PR, HER2). Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; PR, progesterone receptor; U.S., United States of the study and tailored to meet its specific tasks. With Secured Socket Layer (SSL) certificate, the password protected online database application was free of inter- cept by others during data transmission from each study site to the database server. We developed a tissue track- ing database in Oracle (Oracle, Redwood Shores CA), a relational database using caTissue Version 1.0 structure with extensions to track tissue transfer across the ELLA consortium (Figure 1). All bodily fluids and FFPE tissue samples were inventoried in the ELLA Station and the data are secure at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. The database can be accessed via a browser-based front end using Java Server Faces 3. RESULTS Data presented are based on 765 study participants re- cruited as of June 1, 2009 (364 in the U.S. and 401 in Mexico). The majority (78.9%) of participants were in- terviewed within one year of diagnosis. Response rates were extremely high, ranging from 95 to 99%. Table 3 presents selected risk factor characteristics for the total population as well as by country. Women in the U.S. were significantly younger than those in Mexico. Fifty-nine percent of the U.S. patients were born in Mexico and the majority has lived in the U.S. for over ten years. We recruited roughly equal pro- portions of English and Spanish speakers in the U.S. Women in Mexico had a significantly higher number of live births and rates of breastfeeding. The proportion of post-menopausal women was significantly higher in Me- xico than the U.S. Use of oral contraceptives and hor- mone replacement therapy were significantly higher in the U.S. than Mexico, but use of hormone therapy was low overall (14%). Women in Mexico were less likely to have had prior mammography. Although obesity rates were equally high in both countries, women in Mexico reported a lower BMI at age 30 compared to those in the U.S. Current cigarette smoking was low in both coun- tries, whereas alcohol consumption was significantly higher in the U.S. than in Mexico.  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1041-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1044 Advisory Committee Steering Committee Principal Investigators US SITES MDACC University of Arizona MEXICO SITES Universidad of SonoraUniversidad de GuadalajaraInstituto Tecnológico de Sonora Tumor Tissue Collection •Collection at each site •TMA construction at MDACC Sample Collection •Blood or Saliva •DNA Extraction at each site IT/Data Management •Questionnaire and Medical Record Data •Web-based database housed at Arizona Tumor Tissue DNA Extraction and Genotyping Blood/Saliva DNA GenotypingStatistics Figure 1. ELLA binational breast cancer study organizational structure. The organizational structure includes the five recruitment sites, the research core elements, and the Steering and Advisory Com- mittees. Recruitment, data collection, tissue collection, and DNA extraction are conducted at each site. Tracking of participants, Risk Factor Questionnaire (RFQ), Medical Record Abstraction (MRA), and biological samples (deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA] and Tissue Microarray [TMA] repositories) are maintained in separate but integrated databases. Databases can be accessed via browser-based front end using Secured Socket Layer certificate. 4. DISCUSSION In 2006, there were 44.3 million Hispanics (14.8 percent of total) in the U.S., with those of Mexican descent comprising 64 percent of the total. It is projected that the Hispanic population will grow to 102.6 million (24.4 percent of total) by 2050 [34], making it the fastest growing racial/ethnic minority group in the U.S. In addi- tion, foreign born individuals from Mexico comprise the largest immigrant group in the U.S. In spite of the con- tinued growth of the Hispanic population in the U.S. (44.3 million in 2006) [34] and the fact that breast can- cer represents the number one cause of cancer deaths in Hispanic women [35], limited data exist on breast cancer risk factors or the breast cancer clinical and tumor marker profile for this underserved population. The binational nature of the ELLA Study and re- cruitment of large numbers of women of Mexican descent in the U.S. and Mexico will provide a unique opportunity to explore a variety of risk and protective factors in relation to breast cancer subtypes, including the cultural impact of the adoption of U.S. lifestyles. Pike et al. [12] proposed that the lower breast cancer risk among Hispanic women compared to NHWs is almost entirely explained by their younger age at first full term pregnancy, higher parity, low use of HRT, and low alcohol consumption. These authors also ob- served a lower risk of breast cancer in foreign-born than U.S.-born Hispanics. The large proportion of foreign-born women in the ELLA Study (59%) will provide unique opportunities to assess residency and migration history in relation to risk factor profiles and disease patterns. Our data show that Mexican women with breast cancer tend to have more children, are less likely to use contraceptives or HRT, and less likely to consume alcohol or smoke cigarettes, as compared to their U.S. counterparts. However, no differences were shown for age at menarche, age at menopause, or age at first birth. Data from the South-west Hormone, In- sulin, Nutrition, and Exercise (SHINE) Study [15,18] show that a later age at menarche and higher parity were shown to be protective, whereas a later age at first birth was associated with higher risk of breast cancer; however, associations were not all statistically  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1040-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1045 Table 3. Characteristics of participants in the ELLA study, March 1, 2007 to June 1, 2009. Total (N = 765) U.S. (N = 364) Mexico (N = 401) Age at interview, years, mean (SD) 53.6 (12.6) 51.6 (12.2) 55.5 (12.7)* Highest level of educationa, No. (%) Less than high school 376 (53.3) 142 (39.1) 234 (68.4) High school 187 (26.5) 120 (33.1) 67 (19.6) Post-high school 142 (20.1) 101 (27.8) 41 (12.0)* Country of birthb, No. (%) U.S.-born 150 (41.2) Foreign-born 214 (58.8) Nativityb, No. (%) U.S.-born, living in U.S. ≥ 10 y 137 (37.6) U.S.-born, living in U.S. < 10 y 13 (3.6) Foreign-born, living in US ≥ 10 y 163 (44.8) Foreign-born, living in US < 10 y 51 (14.0) Language useb,c, No. (%) English 173 (47.5) Spanish 191 (52.5) Age at menarche (y), mean ± SD 12.8 (1.6) 12.8 (1.6) 12.9 (1.6) Parous, No. (%) 700 (91.5) 334 (91.8) 366 (91.3) Age at first live birth, mean (SD) 22.9 (5.5) 22.7 (5.6) 23.0 (5.5) No. live births, mean (SD) 3.6 (2.1) 3.2 (1.8) 3.9 (2.4)* Ever breastfeedingd, No. (%) 532 (69.6) 210 (57.7) 322 (80.5)* Up to 9 months 165 (31.0) 87 (41.4) 78 (24.2) 9+ months 367 (69.0) 123 (58.6) 244 (75.8)* Menopausal status at interview, No. (%) Premenopausal 334 (43.7) 186 (51.1) 148 (36.7)* Post-menopausale 431 (56.3) 178 (48.9) 253 (63.1) Age at natural menopause, years, mean (SD) 48.4 (5.2) 48.7 (4.7) 48.3 (5.4) Contraceptive usef, No. (%) 416 (55.2) 219 (60.7) 197 (50.1)* HRT use g, No. (%) 70 (14.3) 49 (23.3) 21 (7.6)* Prior mammography, No. (%) 470 (61.4) 244 (67.0) 226 (56.4)* Family history of breast cancerh, No. (%) 91 (12.2) 56 (15.7) 35 (9.0)* Recent BMIi, mean (SD) 29.2 (6.2) 29.6 (6.9) 28.8 (5.4) Underweight (< 18.5), No. (%) 5 (0.8) 4 (1.2) 1 (0.3) Normal (18.5-24.9), No. (%) 163 (24.6) 81 (24.7) 82 (24.6) Overweight (25.0-29.9), No. (%) 232 (35.1) 105 (32.0) 127 (38.0) Obese (≥ 30.0), No. (%) 262 (39.6) 138 (42.1) 124 (37.1) BMI at age 30 yearsj, mean (SD) 24.4 (4.6) 24.7 (4.9) 24.0 (4.3) Waist circumferencek, cm, mean (SD) 95.2 (14.2) 94.4 (16.6) 95.6 (12.8) Waist/hip ratiol, cm, mean (SD) 0.88 (0.1) 0.88 (0.1) 0.89 (0.1) Current cigarette smoking, No. (%) 50 (6.5) 29 (8.0) 21 (5.2) Alcohol usem, No. (%) 428 (56.1) 228 (62.8) 200 (50.0)*  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1041-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1046 Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; SD, standard deviation; U.S., United States; *P < 0.05 comparing differences between Mexico and the U.S. Differences in means were determined by t test, and differences in proportions were determined by chi-squared tests; P val- ues are 2 sided; aIncludes 705 participants (363 in the U.S. and 342 in Mexico); bAll Mexican women were born in Mexico had questionnaire administered in Spanish. With the exception of 2 participants, all foreign-born U.S. women were born in Mexico; cBased on language use during the interview.; dIn- cludes 764 participants (364 in the U.S. and 400 in Mexico); ePeriods stopped for at least 12 months due to natural menopause, bilateral oopherectomy, or other reason and age at interview older than mean age of natural menopause; fIncludes 754 participants (361 in the U.S. and 393 in Mexico); gIncludes women reporting periods stopped for at least 12 months; 488 participants (210 in the U.S. and 278 in Mexico); hFamily history of breast cancer in first de- gree relatives. Excludes adopted women who reported not knowing their blood relatives and those who reported not knowing whether any family member had any type of cancer. Includes 746 participants (356 in the U.S. and 390 in Mexico); iWeight (kg)/height (m)2. Defined by self-reported weight and height 1-3 years prior to diagnosis. Includes 662 participants (328 in the U.S. and 334 in Mexico); jWeight (kg)/height (m)2. Includes 542 participants (296 in the U.S. and 246 in Mexico) and excludes women less than 30 years of age; kIncludes 603 participants (208 in the U.S. and 395 in Mexico); lIncludes 599 participants (207 in the U.S. and 392 in Mexico); mIncludes 763 participants (363 in the U.S. and 400 in Mexico). significant, and some varied by pre- and post-menopausal status. Data on the protective effect of breastfeeding have been published, including the most recent recommenda- tions from the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) for breast cancer prevention [36]. Given the high proportion of women who breastfed in the ELLA Study (70%), future studies will be able to explore associations among women by molecular subtype with higher rates of breast- feeding than those reported in the literature. Our data on obesity show that prevalence is equally high in both countries. Obesity in Mexico is a recent major epidemic; in 1988, 33.4 % of adults were classi- fied as overweight/obese and this figure has risen to 71.9% in 2006 [37], with rates higher in women than men. In the U.S., Hispanics suffer disproportionately from obesity [38], albeit foreign-born Hispanics have a lower likelihood of being overweight/obese compared with those born in the U.S. [39]. Although results of the SHINE study showed no deleterious effect of obesity for risk of breast cancer in pre- or post-menopausal Hispanic women [15], a better understanding of its potential ef- fects on the distribution of breast cancer specific pheno- types is needed. Results of two studies found that a higher BMI and/or a high waist-to-hip ratio was associ- ated with an increased risk of basal-like breast cancer [40,41] or triple negative tumors [42]. Data from the ELLA study will allow us to elucidate the relation of obesity measures to disease phenotypes for women of Mexican descent who are disproportionately affected by high rates of overweight and obesity. Reports in the literature show that Hispanic women tend to be diagnosed at a younger age than NHWs [6, 7,43]. Our data based on age at interview are consistent with these findings. Whether or not this lower age pri- marily reflects the age structure of the population is un- clear. In the U.S, Hispanics have a lower median age compared to NHWs (25.8 vs. 38.6 years) [34] and is similar to the median age in Mexico (25 years) [44]. Data on tumor stage show that women in Mexico are diagnosed less frequently with early stage tumors, which is consistent with published reports from Mexico [45]. Results of our study show lower rates of mammography screening in Mexican participants compared to those in the U.S., albeit these are much higher than those re- ported in national surveys for Mexico [46]. Limitations of our study include the lack of a popula- tion-based sample. Both countries included largely a clinic-based recruitment. Given that Mexico does not have a population-based cancer registry, recruitment for the study occurred in the IMSS hospitals in all three sites. IMSS covers approximately 60% of the Mexican popu- lation by providing care to all formally employed indi- viduals and their family members. In Guadalajara, two additional hospitals that serve the unemployed, poorer segment of the population were used for recruitment. Thus, in Mexico, patients seeking care in the private hospital setting are not captured through our recruitment strategies; however, this is likely to represent only ap- proximately 5% of the population [47]. In the U.S., re- cruitment took place at M.D. Anderson, a tertiary refer- ral center, a county hospital, and a clinic serving indigent patients and underserved women. In Arizona, cases were ascertained at the Arizona Cancer Center, county hospi- tals in Tucson and Phoenix, community health centers, and other facilities that serve the Hispanic population in the state. Results of the ELLA Study show that differences exist in breast cancer risk factor patterns between Mexico and the U.S. women. Our experience working with Mexico has shown that logistics related to recruitment, collection of medical record data, and tissue retrieval is less chal- lenging in this country compared to the U.S. Given that our study includes well-characterized populations, with comprehensive epidemiological data linked to well-anno- tated tumor samples and clinical data, future studies will be extremely valuable in understanding the breast cancer burden in Mexican and Mexican-American women. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are indebted to Ana Lilia Amador, Leticia Cordova, Carole Kepler, and Fang Wang from the Arizona Cancer Center as well as Dr. Alejan- dro Gómez-Alcalá from the IMSS in Ciudad Obregon, Sonora for their valuable contribution. We appreciate the support of the Biosciences Graduate Studies of the Department of Scientific and Technological  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1040-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1047 Research of the University of Sonora. 6. GRANT SUPPORT In the U.S., work was supported by the Avon Foundation, a supplement to the Arizona Cancer Center Core Grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-023074-2953), a grant from Susan G. Komen for the Cure (KG090934) and a supplement to the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center SPORE in Breast Cancer (P50 CA116199-02S1). In Mexico, work was supported by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de México (CONACYT). REFERENCES [1] Parkin, D. M. (2002) Cancer incidence in five continents. In: Parkin, D.M., Whelan, S.L., Ferlay, J., Teppo, L. and Thomas, D.B., Eds., IARC, World Health Organization, 8. [2] Lozano-Ascencio, R., Gomez-Dantes, H., Lewis, S., et al. (2009) Breast cancer trends in Latin America and the Caribbean (Spanish). Salud Publica de Mexico, 51(Suppl. 2), S147-S156. [3] Knaul, F.M., Arreola-Ornelas, H., Velazquez, E., et al. (2009) The health care costs of breast cancer: The case of the Mexical Social Security Insitute (Spanish). Salud Publica Mexico, 51(Suppl. 2), S286-S295. [4] Smigal, C., Jemal, A., Ward, E., et al. (2006) Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: Update 2006. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 56(3), 168-183. [5] Howe, H.L., Wu, X. and Ries, L.A. (2006) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2003, featuring cancer among U.S. Hispanic/Latino Populations. Cancer, 107(8), 1711-1742. [6] Hedeen, A.N. and White, E. (2001) Breast cancer size and stage in Hispanic American women, by birthplace: 1992-1995. American Journal of Public Health, 91(1), 122-125. [7] Elledge, R.M., Clark, G.M., Chamness, G.C., et al. (1994) Tumor biologic factors and breast cancer prognosis amont white, Hispanic, and black women in the United States. Journal of National Cancer Institute, 86(9), 705- 712. [8] Shavers, V.L., Harlan, L.C. and Stevens, J.L. (2003) Ra- cial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under 35. Cancer, 97(1), 134-147. [9] Miller, B.A., Hankey, B.F. and Thomas, T.L. (2002) Im- pact of sociodemographic factors, hormone receptor status, and tumor grade on ethnic differences in tumor stage and size for breast cancer in US women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155(6), 534-545. [10] Lantz, P.M., Mujahid, M., Schwartz, K., et al. (2006) The influence of race, ethnicity and individual socioeconomic factors on breast cancer state at diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 96(12), 2173-2178. [11] Martinez, M.E., Nielson, C.M., Nagle, R., et al. (2007) Breast cancer among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White Women in Arizona. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 18(Suppl. 4), 130-145. [12] Pike, M.C., Kolonel, L.N., Henderson, B.E., et al. (2002) Breast cancer in a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: Risk factor-adjusted incidence in Japanese equals and in Hawaiians exceeds that in Whites. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 11(9), 795-800. [13] Risendal, B., Hines, L.M., Sweeney, C., et al. (2008) Family hisotry and age at onset of breast cancer in His- panic and non-Hispanic white women. Cancer Causes Control, 19(10), 1349-1355. [14] Slattery, M.L., Sweeney, C., Edwards, S., et al. (2007) Body size, weight change, fat distribution and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 102(1), 85-101. [15] Slattery, M.L., Edwards, S., Murtaugh, M.A., et al. (2007) Physical activity and breast cancer risk among women in the Southwestern United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(5), 342-353. [16] John, E. M., Horn-Ross, P. L. and Koo, J. (2003) Life- time physical activity and breast cancer risk in a multi- ethnic population: the San Francisco Bay area breast cancer study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Pre- vention, 12(11), 1143-1152. [17] Sweeney, C., Giuliano, A.R., Baumgartner, K.B., et al. (2007) Oral, injected and implanted contraceptives and breast cancer risk among U.S. Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. International Journal of Cancer, 121(11), 2517-2523. [18] Murtaugh, M.A., Sweeney, C., Giuliano, A.R., et al. (2008) Diet patterns and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: The four-corners breast cancer study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(4), 978-984. [19] John, E.M., Phipps, A.I., et al. (2005) Migration history, acculturation, and breast cancer risk in Hispanic women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 14(12), 2905-2913. [20] Sorlie, T., Tibshirani, R., Parker, J., et al. (2003) Re- peated observation of breast tumor subtypes in inde- pendent gene expression data sets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(14), 8418-8423. [21] Thompson, P.T., Lopez, A.M. and Stopeck, A. (2008) Breast Cancer Prevention. In: Alberts, D.S. and Hess, L.M., Eds., Fundamentals of Cancer Prevention, 2nd Edition, Springer, New York, 255-276. [22] Perou, C.M., Sorlie, T., Eisen, M.B., et al. (2000) Molecu- lar portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 406(6797), 747-752. [23] Carey, L.A., Perou, C.M., Lvasy, C.A., et al. (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA, 295(21), 2492-2502. [24] Rakha, E.A., Elsheikh, S.E., Alekandarany, M.A., et al. (2009) Triple-negative breast cancer: Distinguishing be- tween basal and nonbasal subtypes. Clinical Cancer Re- search, 15(7), 2302-2310. [25] Li, C.I., Malone, K.E. and Daling, J.R. (2002) Differ- ences in breast cancer hormone receptor status and his- tology by race and ethnicity among women 50 years of age and older. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Pre- vention, 11(7), 601-607. [26] Chu, K.C. and Anderson, W.F. (2002) Rates for breast  M. E. Martínez et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1041-1048 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1048 cancer characteristically by estrogen and progesterone receptor status in the major racial/ethnic groups. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 74(3), 199-211. [27] Setiawan, V.W., Monroe, K.R., Wilkens, L.R., et al. (2009) Breast cancer risk factors defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status. American Journal of Epi- demiology, 169(10), 1251-1259. [28] Brown, M., Tsodikov, A., Bauer, K.R., et al. (2008) The role of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in the survival of women with estrogen and progesterone re- ceptor-negative, invasive breast cancer. Cancer, 112(4), 737-747. [29] Bauer, K.R., Brown, M., Cress, R.D., et al. (2007) De- scriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and Her2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phe- notype. Cancer, 109(9), 1721-1728. [30] Alegria, M. (2009) The challenge of acculturation meas- ures: What are we missing? A commentary on Thomson and Hoffman-Goetz. Social Science & Medicine, 69(7), 996-998. [31] Hunt, L.M., Schneider, S. and Comer, B. (2004) Should “acculturation” be available in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine, 59(5), 973-986. [32] Carter-Pokras, O. and Bethune, L. (2009) Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. A commentary on Thomson and Hoffman-Goetz. Social Science & Medicine, 69(7), 983-991. [33] Nielsen, T.O., Hsu, F.D., Jensen, K., et al. (2004) Immu- nohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 10(16), 5367-5374. [34] U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic Population of the United States. http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo / hispanic/hispanic_pop_pre sentation.html [35] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Pro- motion, 2009. Cancer among Women. http://www.cdc. gov/cancer/dcpc/data/women.htm [36] World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2007) Food nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: A global perspective. AICR, Washington, D.C. [37] Romieu, I. and Lajous, M. (2009) The role of obesity, physical activity and dietary factors on the risk of breast cancer: Mexican experience. Salud Publica de Mexico, 51(Suppl. 2), S172-S180. [38] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) Dif- ferences in prevalence of obesity among black, white, and Hispanic adults—United States, 2006-2008. MMWR, 58(27), 740-744. [39] Akresh, I.R. (2008) Overweight and obesity among for- eign-born and U.S.-born Hispanics. Biodemography and Social Biology, 54(2), 183-199. [40] Millikan, R.C., Newman, B., Tse, C.K., et al. (2008) Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 109(1), 123-139. [41] Yang, X.R., Sherman, M.E., Rimm, L., et al. (2007) Dif- ferences in risk factors for breast cancer molecular sub- types in a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 16(3), 439-443. [42] Kwan, M.L., Kushi, L.H., Weltzien, E., et al. (2009) Epidemiology of breast cancer subtypes in two prospec- tive cohort studies of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research, 11(3), 1-13. [43] Bayer-Chammard, A., Taylor, T.H. and Anton-Culver, H. (1999) Survival differences in breast caner among ra- cial/ethnic groups: A population-based study. Cancer De- tection and Prevention, 23(6), 463-473. [44] Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. Total population by federal entity: Age displayed and five-year age groups by sex (Spanish). http://www.inegi.org.mx/ est/contenidos/espanol/sistemas/conteo2005/Default.asp [45] Mohar, A., Bargallo, E., Ramirez, M.T., et al. (2009) Available resources for the treatment of breast cancer in Mexico (Spanish). Salud Publica de Mexico, 51(Suppl. 2), S263-S269. [46] Olaiz, G., Rivera, T., Shamah, T., et al. (2006) Health and nutrition national survey 2006 (Spanish). Instituto Na- cional de Salud Publica, Cuernavaca. [47] Frenk, J., Gonzalez-Pier, E, Gomez-Dantes, O., et al. (2006) Health system reform in Mexico 1: Comprehen- sive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico. Lancet, 368(9539), 1524-1534. |