Natural Resources, 2012, 3, 229-239 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/nr.2012.34030 Published Online December 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/nr) 1 Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? Richard R. Marcus International Studies Program, California State University, Long Beach, USA. Email: richard.marcus@csulb.edu Received March 21st, 2102; revised August 9th, 2012; accepted September 14th, 2012 ABSTRACT In Ambovombe-Androy water is scarce, time-consuming to obtain, and expense. Nonetheless, there is little study into the complexity of popular perception of costs for services in Madagascar. This paper addresses this gap. It is based on a district-wide household survey, focus groups, and interviews. It looks at the wide variation in pricing expectations across a number of intra-community demographic groups and economic classes before considering the user perceptions of water markets themselves as determinants of their willingness to pay. It concludes by isolating the determinants un- der which and places in which the new macro-level strategies are likely to be accepted, and work, at the community level in Ambovombe-Androy. Keywords: Madagascar; Water Policy; Water Management; Ambovombe 1. Introduction Ambovombe-Androy is a semi-arid district in Madagas- car’s extreme south1. The relatively homogenous popula- tion survives on a combination of small-holder agricul- ture and pastoral activities. Obtaining water for basic human needs is overwhelmingly the largest concern of the populace. As a hydrologically closed basin with a rapidly growing population water is scarce, expensive, and time-consuming to obtain. The district thus serves as a tremendous test for new state and donor funded initia- tives to increase the percentage of the population with safe water access from 35 percent in 2006 to 65 percent in 2012. Water is integrated into broader decentralizing governance and development strategies. As such, the government has been very articulate on the mechanisms for augmenting water access: build more community wells, set up community-managed integrated water sys- tems, and promote private-public partnerships. What is less well articulated, but nonetheless clear, is how this is to be paid for. As pu t in a recent World Bank water pro- ject document [1], there will be “full cost recovery and acceptable O & M” or even, in another recent World Bank water project document even fu ll co st reco very an d 100% O & M. The presumption is that user fees can drive a s us- tainable water market. While there is some contingent - valuation modeling in Madagascar, from which conclu- sions are extrapolated to the Androy region for policy purposes, there is little study into the contextual factors that drive local willingness-to-pay at the local level in Ambovombe. The gap in contextual knowledge is par- ticularly acute in Southern Madagascar for when it comes to basic needs there tends to be high variation. For instance, a recent JICA (Japanese International Coopera- tion Agency) study of user-fee based health care services in rural Madagascar found that the conditions under which user fees of health care services will improve health ser- vice effectiveness, efficiency and equity are difficult to determine. Based on a robust literature, higher levels of intra-community variation leads to more complex deter- minants of willingness. It thus would seem that willing- ness-to-pay needs to be as much a social measure as an economic one. This paper is such an effort. It is based on a district-wide household survey (n = 521), focus groups, and interviews by the author in 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006, 1In September 2004 President Marc Ravalomanana passed, by decree, a change in local government structure that removed power from the district level and vested it in a newly created region level. There are 22 regions in Madagascar and leadership is appointed by the executive. The change to the region was ratified in a constitutional referendum on 4 April 2007. Changes in power structure in Ambovombe-Androy did not take hold until 2006 when this study was well under way using district delimiters. Thus this study uses the old district boundaries not the region boundaries. The region, Androy, is not hydrologically closed but there also is no river flow. It would be reasonable to expect, there- fore, that the challenges to the 17 communes within Ambovombe dis- trict would be the same but that perhaps some of the other communes in the region might have different challenges. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 230 and 2010. It takes as its starting point the survey finding that 70 percent of district residents are willing to pay on average an extraordinary 101 Ariary per bucket (US$ 3.37 per cm) if it ensures year-round resource availability. It goes on to model the wide variation in that willingness across a number of intra-community demographic groups and economic classes, and the perceptions of that will- ingness-to-pay, before considering the user perceptions of water markets themselves as determinants of their willingness. This paper concludes by isolating the deter- minants under which and places in which the new macro- level strategies are likely to be accepted, and work, at the community level in Ambovombe-Androy. 2. Global Currents in Local Water Management: Integrated Water Resource Management 2.1. Overview From the Industrial Revolution to the 1980s water was thought of as a resource to capture for human needs. If we can just dam it, divert it, move it, and swallow it, then we can not only slake our thirst but increase our agricul- tural productivity and industrial capacity, while moving our b a rg e s with increasing eff iciency. This “hard path” [2] reified engineering as the answer to a natural resource need. The Green Revolution of the 1960s led, with some lag time, to recognition that eng ineering, and particularly dams, lead to grave environmental consequences. The knee-jerk reaction was to engineer around the impact: dams were fitted with “fish ladders” to ensure endan- gered species could make it to spawning grounds, water storage facilities allowed for the harnessing of high sea- son flows to be used in place of streaming surface water in the dry months. A realization followed. Water is a finite resource. As such it is subject to the laws of re- source maximization. We need to manage it with the utmost efficiency. It is possible to create utilitarian mod- els to ensure that each drop is accounted for. It is further possible to create incentives for improved resource use. Economists spent much of the 1990s discussing how we value, evaluate, and create a valuation of water. Water became an economic good. As with any good we want to maximize, we moved away from constant water pricing. Block or scaled pricing became popular. Higher demand in the face of diminished quantity drives water prices higher while more efficient use and expanded supply re- duces the economic burden. The focus on management of water resources came at a time when natural resource approaches opened its eyes to the power of scale inputs. The focus of scholars and practitioners alike was to find ways of integrated stake- holders across scales. In theory this is an outgrowth of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM). CBNRM can be viewed as either a part of or a reaction to the neoliberal economic approaches which reclaimed popularity in the early 1990s [3]. Neoliberal CBNRM approaches focused on the economic good that can be gained from the market implications of local manage- ment. Challenges to neoliberalism from CBNRM looked to contextualize economic difference. Far from new, the basis for neoliberal versions of CBNRM can be traced to Lockean notions of private property. More than a century ago scholars debated the right of Scottish communities to govern natural resources independent of England [4]. The most recent incarnation of community-based natural resource management is thus more about process (how to achieve it) than it is about theoretical invention. Yet, until recently the resource thought of was either land or forest. The discussion about local water governance circled pre- dominantly around irrigation districts and other consum- ptive uses as oppo sed to cross-level governance of an in- tegral supply. Thus the concept of Integrated Water Re- source Management (IWRM) began to be discussed in the 1960s. However, its early incarnations considered only organizational arrangements, not matters of scale [5]. Water wasn’t considered a local—or localizable—good until w e b e g an th i n k in g a b ou t it a s c o mm od i f i ab l e as t wo decades ago. The Fourth World Water Forum (in Mexico City, March 2006) was entitled “Local Actions for a Global Chal- lenge,” yet it was filled by a growing chorus of voices re- flecting a concern that IWRM creates particularized problems for community level action [6]. Perhaps schol- ars calling for a more sophisticated middle lens for view- ing state (and international) action and localized govern- ance needs to be achieved. In her keynote address to that body, Katherine Sierra, World Bank vice President for Infrastructure, articula ted the q uestions th e epistemi c com- munity has been working with: How can water resources be managed and developed to promote growth and alle- viate poverty in a responsible manner? And how can this be done so that environmental resources are not destroyed, and all people can reap the benefits?” Her answer was a common theme in the forum. We must accept the bases of the Dublin Principles [7]: 1) Fresh water is a finite and vulnerable resource, es- sential to sustain life, development and the environment; 2) Water development and management should be based on a participatory approach, involving users, plan- ners and policy-makers at all levels; 3) Women play a central part in the provision, man- agement and safeguarding of water; 4) Water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good. The last of these is central to the thesis of this paper so Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR 231 there are a small number of community wells, boreholes, and rainwater catchment systems funded by international donors and built by non-government organizations. Price is a function of two sources of supply: AES water and private boreholes. AES water is extremely limited. There are no pipelines going into Ambovombe district, indeed no permanent water source at all. There are a small number of AES boreholes but these are limited to Am- bovombe town, depleted in the dry season, and com- monly saline in the wet season. AES water trucks ferry water from Mandrare River (neighboring Amboasary district; see Figure 1). However, this system, founded by JICA in the early 1990s, has decayed. By 2010 a maxi- mum of 36cm per day could be transported by truck and the distribution of this water is corrupted by the person al influence of large landholders and water brokers [8]. The constraint on supply ensures erratic prices and predatory private markets. In the rainy season a bucket of water may cost 50 ariary (US$ 0.03) per 15 liter bucket (US$ 2/cm). In the dry season predatory water markets can drive prices upwards of 500 ariary (US$ 0.28) per bucket (US$ 18.66/cm), just slightly over the average daily it is worth quoting further: “Within this principle, it is vital to recognize first the basic right of all human beings to have access to clean water and sanitation at an affordable price. Past failure to recognize the economic value of water has led to waste- ful and environmentally damaging uses of the resource. Managing water as an economic good is an important way of achieving efficient and equitable use, and of en- couraging conservation and protect ion of water resources.” From this, Sierra and Forum declaration follow, mar- kets are a management tool, not a good in themselves. Thus the state has a role in regulating the market and creating opportunities even while markets and communi- ties have roles in ensuring a price that can lead to sus- tainable infrastructure and regularized water delivery. In the context of Southern Madagascar the planners and po- licymakers are at the national level—primarily within th e Ministry of Energy (formerly Ministry of Energy and Mines) which not only guides policy but overseas the only government source in the region, the AES (Alimen- tation en Eau dans le Sud). Local participation is pre- dominantly comprised of private borehole owners, th ough Figure 1. Ambovombe.  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 232 income. For some comparison, the cost of drinking water in Madagascar from supply sources ranges from US$ 0.39/cm to US$ 1.30/cm [9]. In the United States the average cost is US$ 0.66/cm. The country with the most expensive water in the OECD is Denmark at US$ 2.24/ cm [10]. When considering what people are willing to pay for water Economist most commonly employ a contingent valuation model. The assumption is that an individual’s demand for a good is a function of the price of the good, prices of substitute and complementary goods, the indi- vidual’s income, and the individual’s tastes [11]. Others, however, [12] further divide the concern of influences over willingness-to-pay for water into economic, institu- tional, and political and social concerns. Economic con- cerns are over ability to pay as much as the function of the price. Institutional concerns are commonly tied to public policy. Are there grant programs? Is there a mecha- nism to charge different rates based upon consumer in- come? Is there the ability of th e state to institute taxes to the benefit of water system creation or management? Lead- ing institutional approaches [13] concur that water access is an economic concern, an institutional concern, and a political and social concern. Saleth and Dinar [13] con- sider water as a public good, the nature and ability of private rights systems, water pricing policy structures, market mechanisms, and the like. They agree with Doug- lass North [14] that institutional performance is con- strained by rent-seeking behavior of elites and politicall y powerful groups. However, they see increasing water scar- city, macro-economic challenges, macroeconomic adjust- ment policies, sociopolitical liberalization, reconstruction programs and the rising power of the middle class as all contributing to a reduction in the barriers institutions face. Economic gains, they argue, are likely to be realized from allocation-oriented institutional change are substantial and also increasing with every increase in water scarcity [13]. In Ambovombe there is no allocation-oriented in- stitutional change so the opportunity for those economic gains to flourish are constrained [15]. What is left is whet her user willingness-to-pay can drive institutional change to overcome the challenges to supp ly and, subsequently, the regularization of the water market. Of note, there is an ongoing vociferous debate as to whether there should be water concerns with paying for water at all. Advocates for water as a human right often conclude that the Dublin Principles are flawed and that the commodification of water should be abandoned. The debate has become more complex to include a large vari- ety of opinions that take into account not only a di- chotomous yes-no respon se but co nditions und er which it should be free, and how might prices be structured in such a way to ensure that water is free for those that need it to be free but “real” for those that can afford it. Block pricing schemas of various sorts have come to dominate the literature [2]. Another aspect of this debate focuses on the idea that a scientific d iscourse on the provision of ecologically provided goods is critical but it is also ne- cessary to understand the community’s p erspective. “It is only on this basis that 1) environmental policies can be implemented in modern democracies; 2) the commu- nity’s justice issues can be specifically addressed; and 3) decision makers can be advised on what is a fair decision in the community’s view” [16]. This study is largely in- ductive. The effort to obtain community perspectives necessitates an approach to this question that reflects respondent views rather than a quest to weigh in on this theoretical debate. Interview and focus group responses support the notion of paying for water as a necessity. As put by a young ma n on the outskirt s of Am bovom be town. Water’s rare. Maybe water from Ambovombe [town] comes here sometimes . So the price is 750 [francs; abou t US$ 0.08], but that is not something that you just can find anywhere. You have to try hard to access to a bucket of water because there’s none anywhere. If there is a small quantity in town, everyone just comes there and buys it and then it’s not sufficient for ev eryone… [sic] If ther e’s something like [a regular but expensive water supply] I’m sure we would keep the money for the improvement of people’s lives. Yeah, I’m positive, yeah [regular but expensive water supply] would work and that would bring change for people’s lives. Survey responses indicate that 70 percent of the Am- bovombepopulation are willing not only to pay for water but to pay a higher price for water than they currently do if it ensured a regularity of supply. As a result of this strong finding this study finds the debate over whether water should be f ree to be moot in the Ambovombe con- text. There are no discussions on the horizon that will bring public or donor funds to a model of water delivery that ens ures a free public g ood and, moreover , the public does not expect it. The relevance of the question, there- fore, is the conditions under which people are willing to pay more. If we can understand what motivates a will- ingness-to-pay more than it may be possible to address some of the perceived social and political barriers to payment. This exercise is an effort to go beyo nd the mis- assumption that poor populations are unwilling and un- able to pay for water and c onsider the mechanisms under which they would feel it appropriate to pay for water and how much that cost should be. 2.2. Socio-Economic and Demographic Variables Socioeconomic and demographic variables are a com- mon starting place for determining personal preference. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 233 There may, for instance, be a difference in water usage based upon ethnic difference, those who are more edu- cated might have more novel coping strategies for short- age, and larger families may find themselves more con- strained in their choices. The variables explored included: Age, Sex, Marital Status (controlling for polygamy), Number of Children, Schooling, Literacy, Ethnicity, Al- ternate Identity (kinship group), Primary Sources of In- formation, Religion, Occupation, Household Size (and distribution) This is consistent with other studies conducted in the developing worldwhich “show that willingness-to-pay varies according to household socio-economic character- istics (e.g. level of education, employment in the formal sector, income), and the characteristics of the new and existing water supplies (e.g. reliability, ease of access, quality).” [17] Yet, in the case of Ambovombe these variables prove to be far from holding robust relation- ships with a willingness-to-pay. (See Tabl e 1 ) Th is is not terribly surprising as how one defines community in Ambovombe and the expectations one has for the state in providing key services in Ambovombe are not signifi- cantly influenced by any of these factors with the excep- tion of the size of the kinship group. Of these, the vari- ables that proved to have at least some interaction with willingness-to-pay for water included Age, Size of Kin- ship Group (a derived variable), Occupation, Sex, Mari- tal Status, and Education. 2.3. Income Income is, arguably, the single most common factor in- fluencing a person’s perceptions regardless of perception type. One would clearly expect that someone who has more money would be willing to pay more money to regularize their water supply and pricing. Indeed, a re- cent study of willingness-to-pay for water in Mexico found the most robust predicto rs of willingness-to-pay to ensure supply to be age, sex (women willing to pay more), and income [18]. Measuring income in a rural area comprised of agricultural and pastoral activities can at best be described as challenging. Numerous tactics have been employed by scholars. Anthropologists and practitioners of Rapid Rural Appraisal generally use a list of indicators of relative wealth (such as metal roofs, paddocks, radios, etc.). This works well when consider- ing intra-communal class structures. For the purposes of this study, however, an agricultural economic method was employed. A portion of the survey included vari- ables to ascertain both quantity of goods either owned or harvested and earnings from goods sold. These variables included: Land (ha), Rice harvest (by each season); Other Crops (b ro ken down by type); Earnings from Crop Sales; Collected Items (Broken down by item); Livestock (broken down by type); Earnings from Livestock Sales (broken down by live- stock type); Salaries; Other cash income. Production and livestock variables were valued at av- erage local market prices, standardized, weighted and then constructed into a proxy Income Index. Land was left as an independent variable. In the case of “Income” outliers were explor ed and, if unex plainable, removed. In the case of Land, surveyors conducted interviews in the field and noted discrepancies between their own esti- mates and the respondents (these were rare). Cross- checking between land size and production, comparing to average levels, served as a secondary check of response authenticity. The av erage income and land size, and their correlation with willingness-to-pay is repo rted in Tab l e 2 . Note that both figures are consistent with other studies [19]. Once again it is surprising that neith er inco me n or land interact with a willingness-to-pay. That is, there is no tendency for someone with a higher or income or more land to be willing to pay for more money for regularized water supply than someone with a lower income or a Table 1. Socio-economic and demographic relationships with willingness-to-pay. Variable Response Correlation w/willingness Age 33% (average respondent age) 0.125** Size of kinship group 32% (belong to a large group) –0.152** Occupation (farmer) 97% (self identify as a farmer) –0.03 Sex (male) 58% (of sample is male) –0.104* Marital status 82% (of sample is married) 0.025 Education (years) 24% (have at least a basic education) 0.031 * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 234 small amount of land. This may be explained, in part, by the extrodinarily high av erage willingness. 101 ariary per bucket (US$ 3.37 per cm). For the sake of comparison, the high end used in a recent study of willingness-to-pay in the United States to be $1.59/cm [20]. 2.4. Macro-Structures There is a difference between whether a person is willing to pay for water to ensure the regularity of supply and whether, more philosophically, that person thinks that water should be a free good. It would not be a reach to assume that there would be, nonetheless, a high correla- tion in response. Clos ely tied to the idea of water cost as a function of supply is who is responsible for providing it and who should be. This mandates a look at macro- structural change. A number of variables in this study were employed to probe perceptions of macro-structures and macro-structural change. These include: Should water b e a free good; Whose job is it to provide water; How effective is the AES; Desire to see an increase in Malagasy companies; Desire to see an increase in Foreign companies; Public vs Private source preference; A series of questions about political change (democra- tization, leadership, etc.); A series of questions about the quality of governance. From this a proxy variable of “liberal” was created to hone in on political changes to wards individual response- bility and market integration into domains hitherto con- trolled by the state. The rationale is that someone who is more liberal-minded might be more likely to expect little from the state in the provision of water and more from the market. They might also be willing to pay more for the good as part of their increasing individual role (and, perhaps, in lieu of a large, tax-supported state). Liberal- ism, it turns out, does not correlate with a willingness- to-pay more for water. Indeed, few political perceptions do. The factors that did bear some relationship to will- ingness-to-pay were a perception that water should be free, that the state should be the supplier of water, that an increase in Malagasy companies in the region would be a boon, that an increase in foreign companies in the region would be a boon, and that supplying water through pri- vate trucks (as opposed to the state mechanism, the AES) would be positive. The strength of such views and the correlation to willingness-to-pay are indicated in Table 3. 2.5. Micro-Structures There is a rich and growing body of literature on the im- portance of the way in which we define community. In Ambovombe how one defines community is seminal to how one perceives state actions as well as the potential success of community based programs. Indeed, if “com- munities” are supposed to be more responsible for the delivery of w ater then focusing on, and su pporting a unit as “the community” that is not locally accepted as “com- munity” is a recipe for disaster. Accountability, partici- pation, and trust will all be low. Unfortunately, it ap pears that “community” in Madagascar’s water sector are de- fined at the commune level while communities them- selves self define at the lower fokontanylev el or the most local level of hamlet. This has led to an erosion of virtu- ally every state and donor-funded effort to create not only water users groups but community management of any type. There is reason to contend, therefore, that un- derstanding the micro-level factors that influence will- Table 2. Land and income relationships with willingness-to-pay. Variable Response Correlation w/willingness Land 2.34 ha (average plot size) 0.05 Income 294457 ariary (US$162) Average per household per annum –0.04 Table 3. Macro-structural relationships with willingness-to-pay. Variable Response Correlation w/willingness Water should be free 73% (yes) –0.143** State’s job 14% –0.093* Pro-malagasy companies 74% 0.003 Pro-foreign com panies 72% –0.44 Private trucks 49% (support the idea of private trucks) 0.21** * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 235 ingness-to-pay in Ambovombe are important. As such, a series of questions were explored both in survey and fo- cus group to form the following variables: A series of questi ons aime d at defini ng “communit y”; The role of the Hamlet and the Fokontany (the two most commonly identified levels for “commu nity”; The existence of a community borehole or well (whether public or private); The existence of a water user ’s group; The quantity of water used per day (broken down by season); The amount of water purchased per day (broken down by season); Perceived water shortage (a de ri ved variable ); Water availability for cattle; Perceived need of water for cattle; Sources of water; Time spent collecting water; Perception of quality of live; The existence of NGOs in the area; A series of questions about community associations and the civil society. The importance of community self-definition man- dates its inclusion in any estimation . Other factors which proved important to include are whether there is a bore- hole or well in the community, whether there is a per- ceived need for water for cows, how much water is used in the household, what the perceived water shortage is, and whether there is a functioning water users group in the community. The responses to these questions and the correlation to willingness-to-pay are found in Table 4. Notably, time costs are high and consumption is low. On average respondents said they spend 3.57 hours per day securing water for their families culminating in an aver- age of 59 liters per household per day. When asked in an open response question about their most pressing need, 86 percent responded that water for consumption domi- nated their concerns. The remaining responses included water for agriculture, water for livestock, food, schools, hospitals, electricity, medicine, and a general sufferance. As importance as these factors are, they do not, with the exception of water quantity used, interact greatly with a willingness-to-pay for water to ensure supply. 3. What Influences How Much a Person Is Willing to Pay for Water in Ambovombe? While this author has focused on institution al concerns in Ambovombe’s water sector in other work, the study herein focuses on political and so cial concerns. Is there a large gap between urban and rural services? How press- ing is the concern over water as compared to other basic goods or conditions? What is the perceived willingness- to-pay a higher amount and what drives that perception? The most common tool for measuring of influences on willingness-to-pay is a probit model. For instance, Olm- stead’s [21] dependent variable is the relationship be- tween a user’s likelihood of receipt of water service and the independent variable. She uses a probit model to es- timate two model functions. Herein, however, the de- pendent variable is the amount of money an individual is willing to pay for water. This is a currency figure ex- pressed in Malagasy ariary. It is therefore interval data, not bivariate. As such, the data doesn’t meet the criteria for Logistical or Probabalistic Regression. Linear regres- sion, is therefore employed. This is a common approach to considering impacts on willingness-to-pay under such data criteria [22-26]. The independent variables in this stu dy also vary fro m econometric studies. What is kept as relevant from contingent valuation models are income and socio-economic and demographic variables. Added to these are perceptions of macro-structures, generally political in nature, and perceptions of micro-structures, such as definitions of “community,” perceived water short- age, and the existence of functioning water-users groups. Table 5 depicts 4 models of influences on willing- ness-to-pay broken down by the category types discussed above: micro perceptions, macro perceptions, income, and socio-economic and demographic variables. Model 1 Table 4. Micro-structural relationships with willingness-to-pay. Variable Response Correlation w/willingness Hamlet/fokontany 90% (defined hamlet or fokontany as comm unity) –0.08 Borehole 26% (have a borehole or well in their community) –0.23** Water for cows 73% (have an unfilled need) –0.29** Water quantity used 59 liters (household water use per day) –0.12** Perceived water shortage 62 liters (perceived household water shortage per day) –0.02 Water users group 6% (have a functioning group in their community) –0.08 ** = p < 0.01. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 236 Table 5. What drives a perceived willingness-to-pay for more for water? Category Variable Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Hamlet/fokontany –2.82** –2.16** –2.92*** –2.92*** Borehole –1.10 –1.23 –2.13* –2.13* Water for cows –2.56** –2.64*** –3.53*** –3.55*** Water quantity used –0.20 –0.59 Perceived water shortage 0.43 0.55 Micro-perceptions Water users group –0. 28 –0.56 Macro-perceptions Water should be free –0.30 –0.30 State’s job 2.26** 2.88** 2.49** 2.49** Pro-malagasy companies –0.41 –0.53 Pro-foreign companies –1.28 –0.90 Private trucks 7.25*** 7.55*** 8.05*** 8.06*** Income Income –0.24 –0.03 0.10 Land 1.40 1.42 Age 1.40 1.15 Size of kinship group –1.07 Occupation (farmer) –0.557 Sex (male) 0.11 Marital status 1. 52 Education (years) –0.39 Adj R-sq 0.30 0.27 0.27 0.27 Socio-economic F 7.68*** 9.88*** 25.18*** 30.30*** * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001. includes the most robust variables from each of these categories. Given the correlation findings discussed above in the socio-economic and demographic category section we would not expect these factors to play much of a role influencing individual willingness-to-pay and, indeed, such variables only serve to detract from the model. Model 2 runs the same data but excluding the socioeconomic and demographic variables. This serves to increase the strength of the model by an F value of more than two points. Model 3 takes the next step of consid er- ing the least influential variables in the other three cate- gories. There is little to expect from the income index proxy given the correlations above. However, because it is so counter-intuitive that income would not influence willingness-to-pay Model 3 leaves income in the model. This leaves room for comparison to the identical model but with income removed (Model 4). We find that re- moving does nothing to reduce the amount of the re- sponse the model describes (Adj R-sq = 0.27) while sig- nificantly increasing the power of the model (to F = 30.30 , p < 0.000). Clearly, however counter-intuitive, income just isn’t a factor in whether a person is willing to pay more for water. The factors that are powerful in describing a perceived willingness-to-pay for water if it ensures supply tend to come from micro-perceptions. Someone that perceives the Hamlet or Fokontany, as opposed to the commune, as his or her community is willing to pay less for water. This coincides logically with the macro-perception that it is the state’s job to provide water (which significantly influences a willingness-to-pay). There is an important policy point here. People are willing to pay more if the provision is made at a higher level. Where at present community is being defined by the state and donors as the commune level, those who share that identification are willing to pay more than those who think the institu- tions created for local delivery are misplaced and/or lack accountability. If the service of water is moved up to the state level then people are willing to pay more. The pre- sumption, focus groups make clear, is that there ju st isn’t Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 237 water supply in Ambovombe. State provision for water will somehow have to include a pipeline or other engi- neering response. Their perception is well-founded. A recent in-depth JICA study concludes that the hydrologi- cally closed basin offers no options for community en- terprise or groundw ater r esources to an swer to water call. It proposes an inter-region al pipeline. The other influential factors on willingness-to-pay are equally intuitive. If a person is fortunate to live in one of the minority communities that has a borehole or well it stands to reason that that person will be less likely to want to pay more for water to regularize supply. Supply in these communities (26%) are already more regular. Livestock, and particularly the livestock of choice in the region, cows, propose a dramatic challenge for water supply. There are alternatives. Most notably, cactus fruit (raketa) are eaten by cattle. However, environmental factors and population increases have led to a decline in the cacti that produce raketa [27]. It is more likely today that raketawill be found in neig hboring Tsihombe than in Ambovombe. With decreasing raketathere is an increas- ing need for water for cattle. Where cattle need to drink water consumption per household goes up dramatically. It stands to reason that the higher consumption drives an unwillingness to pay more per unit. Of course, as cham- pioned in the 2006 Human Development Report which focuses on water, there is an important management dis- tinction to be made be tween prowduction water and house- hold water. However, that distinction remains theoretical in Ambovombe. Water sources are the same regardless of the water need and cattle are integral to sustainin g human livelihoods regardless of whether that person considers him or herself a farmer or herder. More cattle in Androy is considered a sign of wealth [8,28]. More wat er n eed for that cattle means more water consumption and less will- ingness-to-pay a higher unit cost. If there is one surprising finding in this study it is the strength of the role of private trucks. While everyone in Ambovombe district dreams of and talks incessantly about the day a pipe will be built, today’s realities are that water coming from outside Androy comes by truck. When asked “who would you rather buy water from” (and presented with public and private options) the an- swer is overwhelmingly “it doesn’t matter”. But, when asked “Do you think it would be an improvement if pri- vate trucks sold water instead of the AES even if the cost was higher?” a shocking 49 percent say “yes”. While the state should be pr oviding water the population is pe rcep- tive enough to note that it isn ’t and isn’t likely to. There- fore, despite a desire for state action, nearly half would pay more to see greater market intervention. Those who are willing to pay more for private water are willing to pay more period. 4. Conclusions Is there a market answer for Ambovombe’s water woes? The answer would seem to be “yes, but”. The “yes” is practical. People are willing to pay tremendous amounts for water. US$ 3.37/cm is significantly higher than aver- age cost of water within Madagascar’s (few) water dis- tricts. It is five times the average price for water in the United States and a third again above the most expensive water in any OECD country (not controlling for pur- chasing power). The factors that influence that willing- ness are decidedly private in nature. People don’t care where the water comes from as long as it comes. Given the current system about half the population wants to see the rise of private water trucks—an astoundingly high percentage in a region where the state has always been the provider and the only experience with the private sector is predatory marketeers (in water, cattle sales, etc.). The state-run AES enjoys little popular faith and is per- ceived as inefficient, corrupt, and short on answers. That said, there is still a desire for state action. Ambovombe-Androy does not have sufficient water resources to slake its populations’ thirst. Fortunately, there are two major river basins, both within semi-humid regions, within 100 km. Ultimately either the population is going to have to move to the water or the water is go- ing to have to be moved to the population. Given land tenure challenges there appears little choice but to em- bark on an in ter-regional water sch eme. Communities are ill-placed to organize across boundaries and fund large scale development projects. They are certainly finan- cially incapable of paying for capital costs. There will have to be macro-level intervention. Yet communities in Ambovombe-Androy would be willing to pay user-fees that would over time cover not only the resource but the infrastructure investments. Indeed, with higher level in- tervention that ensures resource delivery there is a will- ingness-to-pay more. Moreover, it appears that while the community holds a preference for state action it would accept private action if it ultimately delivered the re- source. What communities appear unwilling to accept are micro level answers to macro level problems. They are willing to pay less to community level water managers, part out of lack of faith in community mechanisms and part out of a savvy understanding that community level answers will not ensure a regular supply. There is one caveat: where there is regular supply people want to pay less. Once a regular supply is established there is thus reason to believe willingness-to-pay will decrease. From the perspective of state water policy, and donor financing, that is a reason for concern. For the perspective of private investment it is also a concern th at it will be increasingly difficult to charge rates that will ensure the investment is repaid. Then again, regularization of supply drives down Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? 238 costs [29]. That is why water is so cheap in OECD coun- tries even though so much of flows through the taps. Perhaps that, and not a debate over public versus private delivery, is all that Ambovombe-Androy residents are looking for. 5. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank California State University, Long Beach and the US Southeast Climate Consortium, supported by US NOAA and USDA , fo r ongo ing su ppor t which facilitates this research. REFERENCES [1] World Bank/PAEPAR, “Projet Pilote d’alimentation en eau Potable et Assainissement en Milieu Rural,” Mission de Suivi du 30 avril au 17 mai 2003. Rapport de Mission de Annie Savina, 2003. [2] P. H. Gleick, “Global Freshwater Resources: Soft-Path Solutions for the 21st Century,” Science, Vol. 302, No. 5650, 2003, pp. 1524-1258. doi:10.1126/science.1089967 [3] K. H. Redford and J. A. Mansour, “Traditional Peoples and Biodiversity Conservation in Large Tropical Land- scapes,” The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, 1996. [4] J. Fisher, “The History of Landholding in England,” Tran- sactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 4, No. 12, 1876, pp. 97-187. doi:10.2307/3677922 [5] V. Ostrom, “The Political Economy of Water Develop- ment,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 52, No. 2, 1982, pp. 450-458. [6] International Institute for Sustainable Development, “Mini - sterial Declaration, Fourth World Water Forum, Local Actions for a Global Challenge,” 2006. http://www.iisd.ca/ymb/worldwater4/ [7] ICWE, “The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development,” International Conference on Water and the Environment, Dublin, 26-31 January 1992. [8] R. Marcus, “Where Community Based Water Resource Management Has Gone to Far: Poverty and Disempow- erment in Southern Madagascar,” Conservation and Soci- ety, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2007, pp. 202-231. [9] A. Dinar and A. Subramanian, “Water Pricing Experience: An International Perspective,” Technical Paper No. 386, World Bank, Washington DC, 1997. [10] NUS Consulting Group, “2005-2006 International Water Report & Cost Survey,” A Business of National Utility Service, Inc., Park Ridge, 2006. [11] D. Whittington, J. Briscoe, X. Mu and W. Barron, “Esti- mating the Willingness to Pay for Water Services in De- veloping Countries: A Case Study of the Use of Contin- gent Valuation Surveys in Southern Haiti,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 38, No. 2. 1990, pp. 293-311. doi:10.1086/451794 [12] S. M. Olmstead, “Thirsty Colonias: Rate Regulation and the Provision of Water Service,” Land Economics, Vol. 80, No. 1, 2004, pp. 136-150. doi:10.2307/3147149 [13] S. R. Maria and A. Dinar, “The Institutional Economics of Water: A Cross-Country Analysis of Institutions and Performance,” The Edward Elgar/World Bank, Chelten- ham and Northampton, 2004. [14] D. C. North, “Institutions, Institutional Change, and Eco- nomic Performance,” Cambridge University Press, Cam- bridge, 1990. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511808678 [15] R. Marcus and J. O. Marcus, “Exit the State: Decentrali- zation and the Need for Local Social, Political, and Eco- nomic Consideration in Water Resource Allocati on in Ma- dagascar and Kenya,” Journal of Human Development. Vol. 9, No. 1, 2008, pp. 23-45. doi:10.1080/14649880701811385 [16] G. J. Syme, E. Kals, B. E. Nancarrow and L. Montada, “Ecological Risks and Community Perceptions of Fairness and Justice: A Cross-Cultural Model,” Risk Analysi s, Vol. 20, No. 6, 2000, pp. 905-916.c [17] A. Gadgil, “Drinking Water in Developing Countries,” Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, Vol. 23, No. 1, 1998, pp. 253-286. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.23.1.253 [18] G. S. M. de Oca, I. J. Bateman, R. Tinch and P. G. Mof- fatt, “Assessing the Willingness to Pay for Maintained and Improved Water Supplies in Mexico City,” CSERGE Working Paper ECM 03-11, 2003. [19] Government of Madagascar, “Enquête Périodique Auprès de Ménages 2005: Rapport Principal,” Ministere de l’Eco- nomie, des Finances, et du Budget, Antananarivo: Re- poblikan’iMadagasikara, 2006. [20] R. G. Alcubilla and R. Garcia, “Derived Willingness-to- Pay for Water: Effects of Probabilistic Rationing and Price,” Unpublished, 2005. [21] S. M. Olmstead, “Thirsty Colonias: Rate Regulation and the Provision of Water Service,” Land Economics, Vol. 80, No. 1, 2004, pp. 136-150. doi:10.2307/3147149 [22] M. H. Chan, E. Baru wa, D. Gilbert, K. Frick and N. Cong- don, “Willingness to Pay for Cataract Surgery in Rural Southern China,” Ophthalmology, Vol. 114, No. 3, pp. 411-416, 2006. [23] C. A. Marra, L. Frighetto, A. F. Goodfellow, A. O. Wai, M. L. Chase, R. E. Nicol, C. A. Leong, S. Tomlinson, B. M. Ferreira and P. J. Jewesson, “Willingness to Pay to As- sess Patient Preferences for Therapy in a Canadian Set- ting,” BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2005, p. 43.; [24] N. B. Leigh, S. Tsao, D. L. Zawisza, M. Nematollahi and F. A. Shepherd, “A Willingness-to-Pay Study of Oral Epi- dermal Growth Factor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Ad- vanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Lung Cancer, Vol. 51, No. 1, 2005, pp. 115-121. [25] D. Whittington, J. Briscoe, X. Mu, W. Barron, “Estimat- ing the Willingness to Pay for Water Services in Devel- oping Countries: A Case Study of the Use of Contingent Valuation Surveys in Southern Haiti,” Economic Devel- opment and Cultural Change, Vol. 38, No. 2, 1990, pp. 293-311. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR  Macropolitics and Microperceptions: Is There a Possible Market Answer to Water Woes in Ambovombe-Androy, Madagascar? Copyright © 2012 SciRes. NR 239 [26] E. L. Michalson, “Recreational and Sociological Charac- teristics of Hunters and an Estimate of the Demand for Hunting in the Sawtooth Area of Idaho,” Water Resources Research Institute, University of Idaho, Moscow, 1973. [27] J. C. Kaufmann, “La Que stion des Raketa: Colonial Strug- gles in Madagascar with Prickly Pear Cactus, 1900-1923,” Ethnohistory, Vol. 48, No. 1-2, 2001, pp. 87-121. doi:10.1215/00141801-48-1-2-87 [28] J.-A. Rakotoarisoa, “Mille Ansd’Occupationhumainedans le Sud-Est de Madagascar: Anosy, Uneile au Milieu De- sterres,” L’Harmattan, Paris, 1998. [29] R. Bhatia and M. Falkenmark, “Water Resource Policies and the Urban Poor: Innovative Approaches and Policy Imperatives,” Water and Sanitation Current, UNDP- World Bank Water and Sanitation Program, Washington DC, 1993.

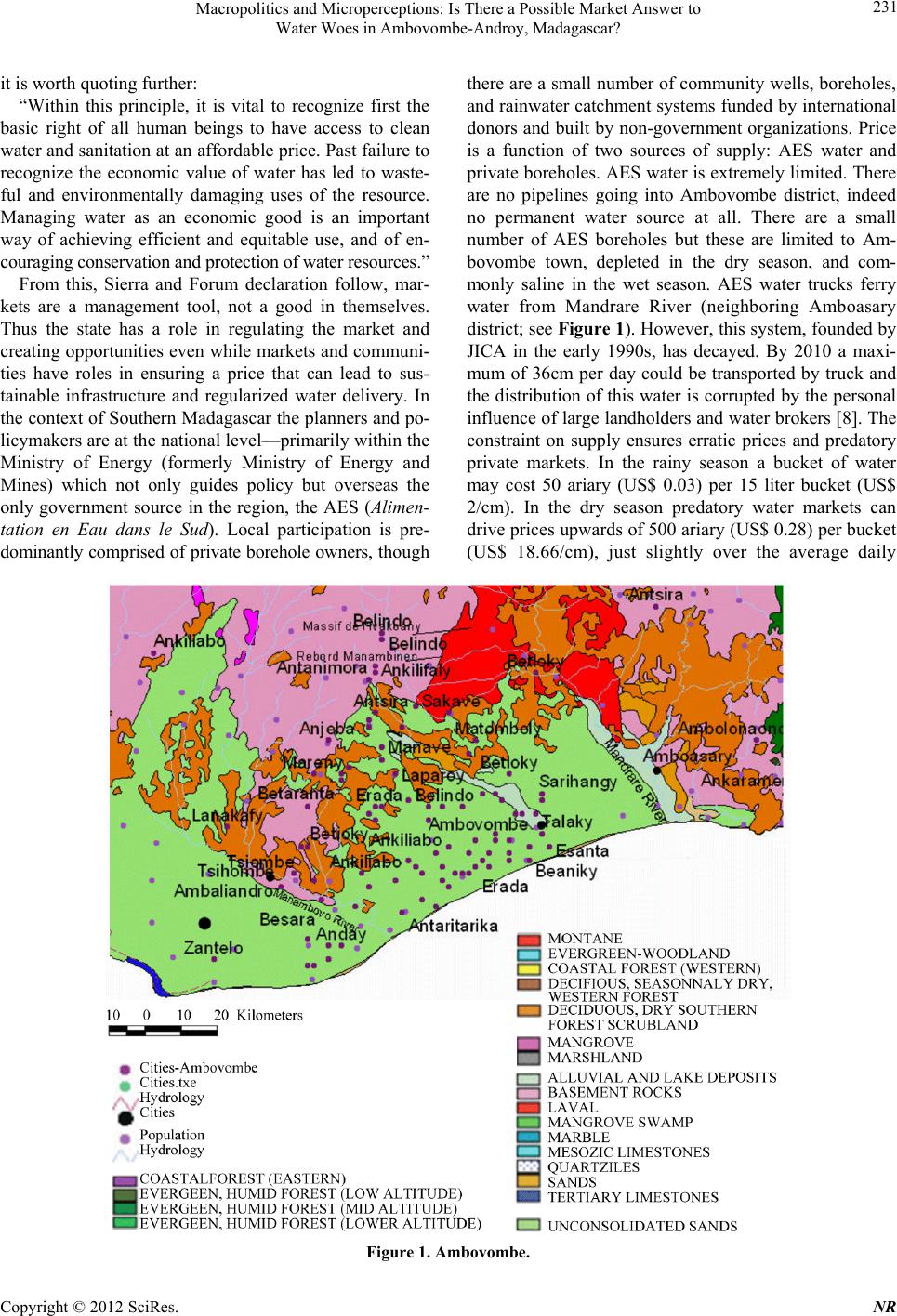

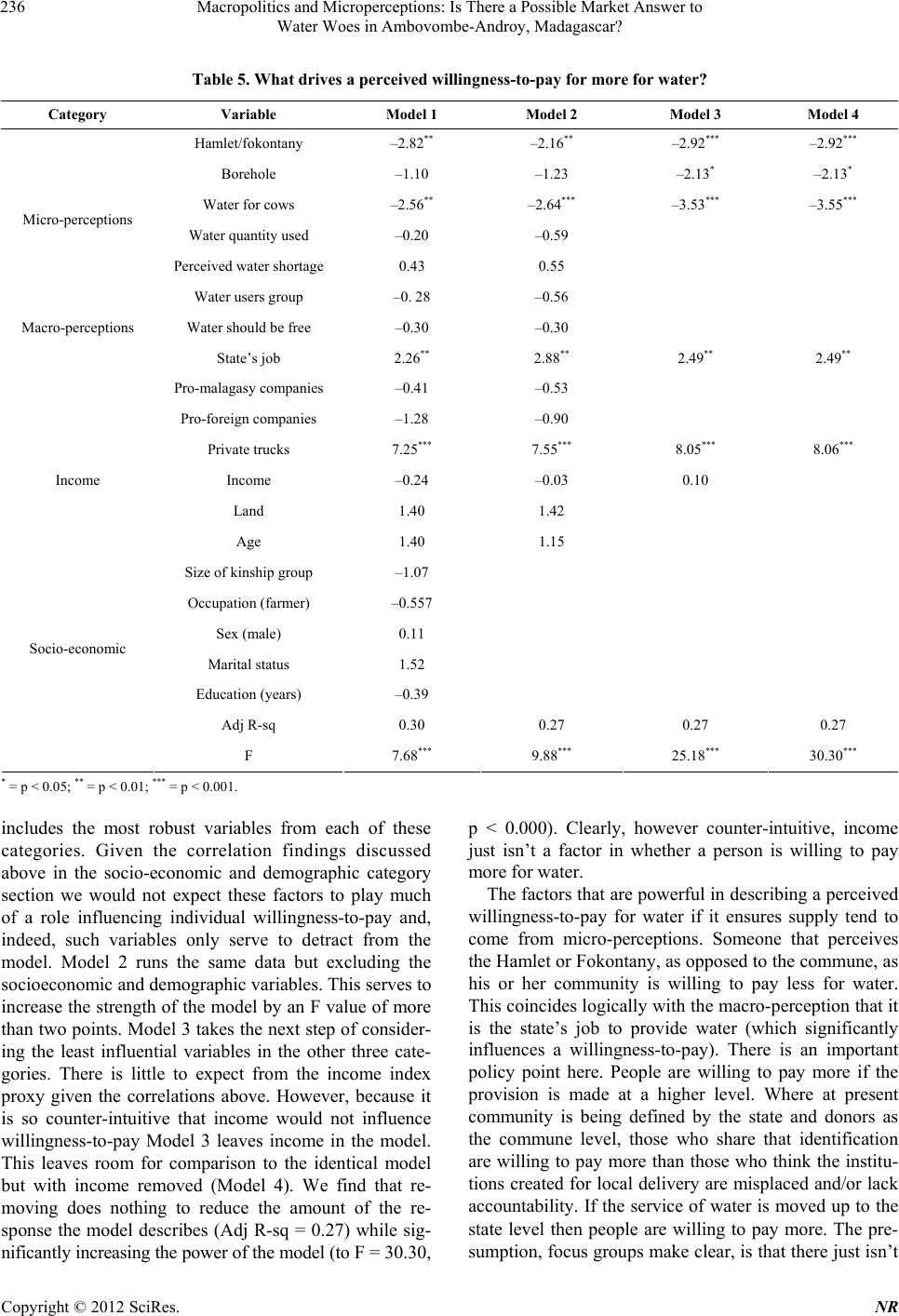

|