Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

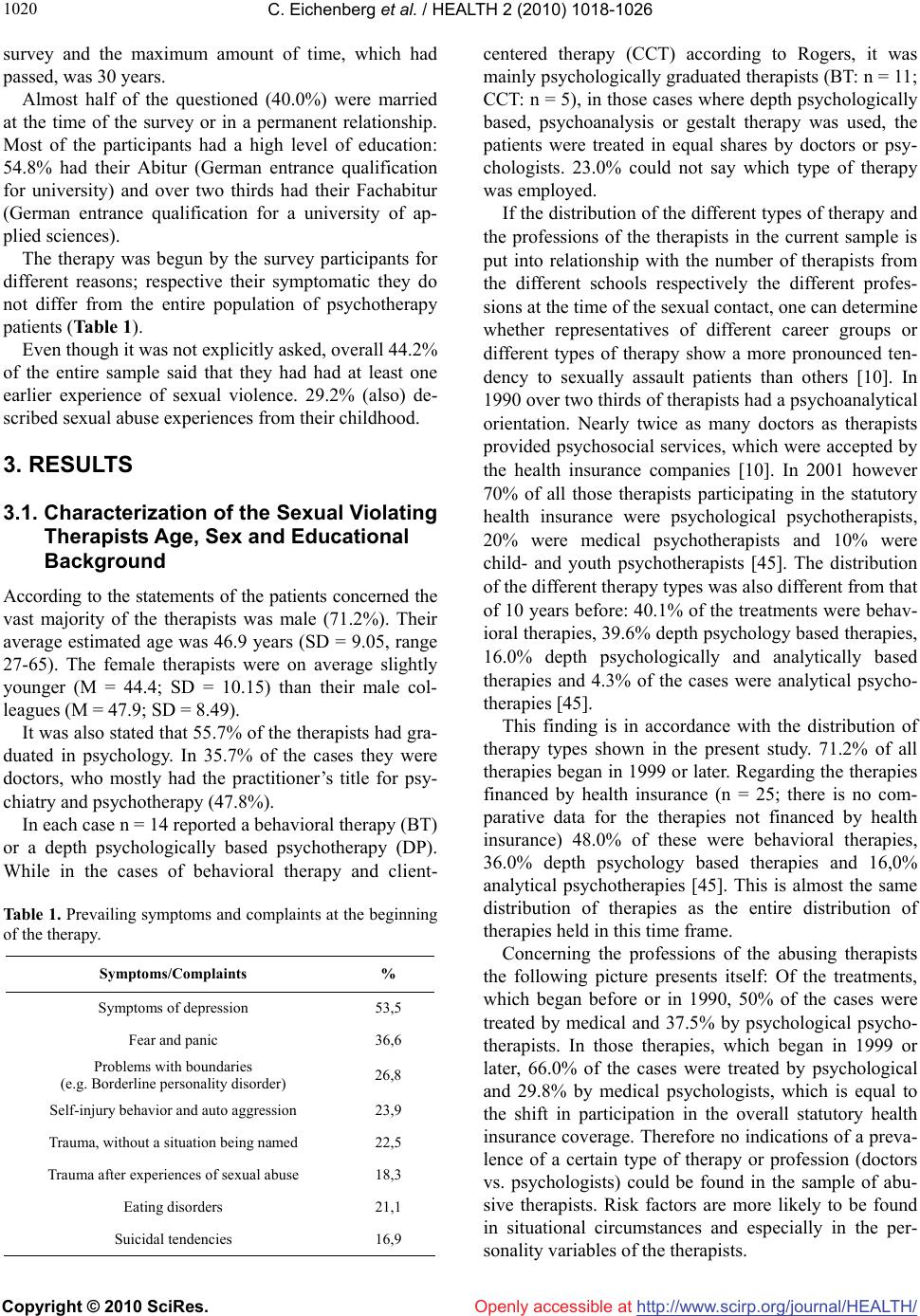

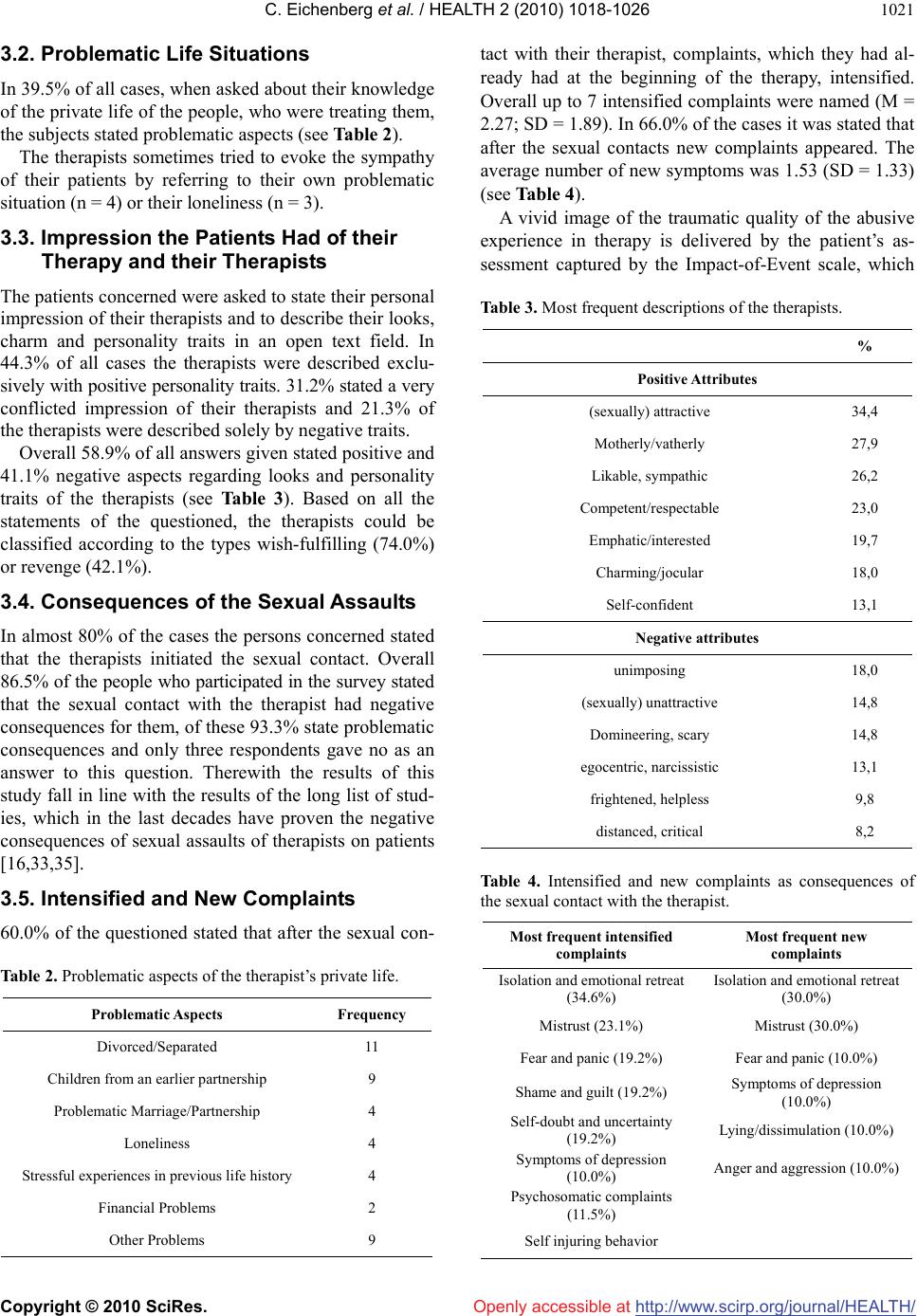

Vol.2, No.9, 1018-1026 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.29150 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Sexual assaults in therapeutic relationships: prevalence, risk factors and consequences Christiane Eichenberg*, Monika Becker-Fischer, Gottfried Fischer German Institute of Psychotraumatology, Cologne, Germany; *Corresponding Author: eichenberg@uni-koeln.de Received 16 April 2010; revised 13 May 2010; accepted 18 May 2010. ABSTRACT A law has been passed in Germany (paragraph 174c StGB), which prohibits therapists from having sexual contact with their patients. This provides the background for a follow-up survey to the previous study completed by Becker- Fischer and Fischer in 1995. The results of this survey are discussed here on the basis of the current status of research concerning preva- lence and risk factors of sexual assaults in therapeutic relationships. The focus of the re- search lies in determining the specific condi- tions of sexual assaults in psychotherapy and psychiatry, risk variables of the therapists and patients, the effects it has on the patients as well as the legal consequences it results in. To en- sure the comparability of the data, an online version of the Questionnaire about Sexual Con- tacts in Psychotherapy and Psychiatry (SKPP; Becker-Fischer, Fischer & Jerouschek) was cre- ated and a survey of N = 77 affected patients was conducted. The majority of the participants in the study reported a serious decline in their overall well being following the incident. How- ever only very few undertook legal steps - only in three cases did it come to a legal procedure. The assumption that sexual contacts in psy- chotherapy result in extremely damaging con- sequences to patients, was affirmed. Despite the changed legal situation, therapists in Ger- many are still not held legally responsible more often than they were 10 years ago. Based on these results a more intensive education of the patients concerning their legal rights is recom- mended. Keywords: Sexual Assaults; Psychotherapy; Patient Abuse; Professional Misconduct 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Prevalence According to the background of the current research si- tuation, it can be assumed that sexual assaults of thera- pists on patients are not isolated cases. On average 10% of the questioned male therapists admitted to having had sexual contact with a patient at least once [1]. However the prevalence rates fluctuate according to the different definitions of what constitutes sexual assault in therapy. When therapists were questioned on average every sec- ond [2-7] up to every fourth [8,9] said that he or she has treated at least one patient that had been exposed to sex- ual abuse in an earlier psychotherapy. Considering the specific problems inherent in determining the prevalence of professional sexual abuse, Becker-Fischer and Fischer [10] assume that there are at least 300 patients, whom this concerns, per year in Germany alone (not including the forms of therapy not accepted by health insurance). All previous research on the subject shows that most of the victims of sexual abuse in psychotherapy and psychiatry are women and most of the perpetrators are men [3,11,12]. The therapists are on average 10-15 years older than their female victims [3,11,13-16]. 1.2. Risk Factors Next to their being male, several other characteristics of abusing therapists, which count as risk factors for sexual abusive behavior to patients, are listed in the relevant literature: the therapists are often respected [13,17], pro- fessionally experienced [11,18], active in their own pri- vate praxis [16,19,20], currently facing difficult life situations [18,21,22], have narcissistic deficits [23-25] and/or have themselves been victims of earlier traumas [27,28]. Based on the results of their survey from the middle of the nineties, Becker-Fischer and Fischer dif- ferentiate [10,29] between the abusing therapists - whose personality is determined by decomposition phenomena in the loosest sense according to the authors - according to psychodynamic aspects. Based on the assumption that  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1019 sexual assaults are repetitions of traumatic events from the therapist’s childhood, differentiation is based on the subconscious motivation for their actions: in the case of wish fulfillment the behavior determining motivation is the denial of the traumatic experience. The denial shows itself in the illusion of a perfect world and the need to be saved by the patient. The actions of the revenge type are motivated by the denial of the traumatic experience and the helplessness experienced in childhood identifying themselves with the former perpetrator. The desire for revenge is then stilled by abusing the patient. 1.3. Consequences for the Patients Concerned The consequences of professional sexual abuses for the patients are consistent in all international literature: all empirical studies that are available to date show very negative consequences for the victims [14,16,30-35]. Named are symptoms such as stronger distrust, isolation, feeling of shame and guilt, fear, depression and suicidal tendencies, anger and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder [36]. Pope [37,38] conceptualizes the conse- quences of sexual contacts in therapeutic relationships with the term “therapist-patient sex syndrome”. Accord- ing to him the negative effects of the therapeutic assaults take the form of a distinctive clinical syndrome, which is partially comparable to the rape syndrome, the reaction to incest, child molestation and a posttraumatic stress disorder. Becker-Fischer and Fischer [10,29] coined the term “professional abuse trauma” on the basis of their research, which in its course manifests the consequences of the sexual contact in the therapeutic relationship. Ac- cording to them a disturbance of the ability to love and to have a relationship can be detected in all the victims. The question of which destructive consequences of sex- ual contacts in therapeutic relationships happen to male victims could not be answered definitively due to the very low number of cases in the available samples. In the thematically relevant literature it is assumed that males suffer from the same consequences of their abuse as women do, but their socialization makes it harder for them to see themselves as victims. In many cases of sexual abuse by professionals neither the following therapist [4] nor the patient [3,6,31] takes legal steps against the abusing therapist. Even if in some more recent surveys of patients the percentage of those who do initiate legal steps, is higher [14,34], it must still be assumed that many of those concerned either do not know that they can sue [39,40] or shrink back from do- ing so, because they are afraid of the strain placed on them by such a procedure [31,39]. Furthermore there is proof that lawsuits do have various disadvantages and difficulties for those concerned [31,32,34], which is par- tially a result of the delinquent orientated nature of the criminal proceedings [41]. 1.4. Objective The aim of this study was to be a follow-up research of the study conducted in the mid-nineties, that was con- ducted by the federal ministry for family, seniors, women and youths [10,29]. Due to the results of the lat- ter survey, the paragraph 174c of the German criminal code was introduced, which since 1998 has stipulated that sexual contacts between therapists and patients con- stitute a criminal offense. As in the earlier study [10,29] people were questioned, who had sexual contact with their therapist during the course of their psychotherapy or psychiatric treatment. The focus of the research was on how the individuals concerned experienced it, the consequences of the sexual contact as well as possible coping measures and legal steps. 2. METHODICAL PROCEDURE 2.1. Data Acquisition For the first survey [10] concerned people were made aware of the study via announcements in newspapers. Currently the research participants are acquired via the internet. The Questionnaire about Sexual Contacts in Psychotherapy and Psychiatry (SKPP; Becker-Fischer, Fischer and Jerouschek) from the earlier study was con- ceptualized as an internet survey in order to enable a relatively cost-effective access to an otherwise hard to reach sample [42,43]. The internet is a valid survey tool. In the current follow-up study the recommendations and rules for conducting online surveys were implemented in their entirety [44]. Webmasters of 94 thematically relevant internet sites (e.g. information sites for patients, homepages of psycho- logical counseling services, self-help pages) were asked to post the request for participation in the survey with a link to the questionnaire on their site. Additionally the request was posted in 6 forums. 2.2. Description of the Sample Of the N = 77 patients 66 were female (85.7%) and 11 male (14.3%). At the time of the interview the subjects were on average 34.82 years old (SD = 11.13; range 15-69). The average age at the time of the sexual contact with the therapist was 28.36 years (SD = 11.2; range 6-63 years). However 10 of the surveyed were minors at the time of the sexual contact with the therapist. Be- tween the time of the sexual contact and the survey on average 6.35 years (SD = 7.48) had passed. For 7 of the questioned less than a year had passed at the time of the  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1020 survey and the maximum amount of time, which had passed, was 30 years. Almost half of the questioned (40.0%) were married at the time of the survey or in a permanent relationship. Most of the participants had a high level of education: 54.8% had their Abitur (German entrance qualification for university) and over two thirds had their Fachabitur (German entrance qualification for a university of ap- plied sciences). The therapy was begun by the survey participants for different reasons; respective their symptomatic they do not differ from the entire population of psychotherapy patients (Table 1). Even though it was not explicitly asked, overall 44.2% of the entire sample said that they had had at least one earlier experience of sexual violence. 29.2% (also) de- scribed sexual abuse experiences from their childhood. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Characterization of the Sexual Violating Therapists Age, Sex and Educational Background According to the statements of the patients concerned the vast majority of the therapists was male (71.2%). Their average estimated age was 46.9 years (SD = 9.05, range 27-65). The female therapists were on average slightly younger (M = 44.4; SD = 10.15) than their male col- leagues (M = 47.9; SD = 8.49). It was also stated that 55.7% of the therapists had gra- duated in psychology. In 35.7% of the cases they were doctors, who mostly had the practitioner’s title for psy- chiatry and psychotherapy (47.8%). In each case n = 14 reported a behavioral therapy (BT) or a depth psychologically based psychotherapy (DP). While in the cases of behavioral therapy and client- Table 1. Prevailing symptoms and complaints at the beginning of the therapy. Symptoms/Complaints % Symptoms of depression 53,5 Fear and panic 36,6 Problems with boundaries (e.g. Borderline personality disorder) 26,8 Self-injury behavior and auto aggression 23,9 Trauma, without a situation being named 22,5 Trauma after experiences of sexual abuse 18,3 Eating disorders 21,1 Suicidal tendencies 16,9 centered therapy (CCT) according to Rogers, it was mainly psychologically graduated therapists (BT: n = 11; CCT: n = 5), in those cases where depth psychologically based, psychoanalysis or gestalt therapy was used, the patients were treated in equal shares by doctors or psy- chologists. 23.0% could not say which type of therapy was employed. If the distribution of the different types of therapy and the professions of the therapists in the current sample is put into relationship with the number of therapists from the different schools respectively the different profes- sions at the time of the sexual contact, one can determine whether representatives of different career groups or different types of therapy show a more pronounced ten- dency to sexually assault patients than others [10]. In 1990 over two thirds of therapists had a psychoanalytical orientation. Nearly twice as many doctors as therapists provided psychosocial services, which were accepted by the health insurance companies [10]. In 2001 however 70% of all those therapists participating in the statutory health insurance were psychological psychotherapists, 20% were medical psychotherapists and 10% were child- and youth psychotherapists [45]. The distribution of the different therapy types was also different from that of 10 years before: 40.1% of the treatments were behav- ioral therapies, 39.6% depth psychology based therapies, 16.0% depth psychologically and analytically based therapies and 4.3% of the cases were analytical psycho- therapies [45]. This finding is in accordance with the distribution of therapy types shown in the present study. 71.2% of all therapies began in 1999 or later. Regarding the therapies financed by health insurance (n = 25; there is no com- parative data for the therapies not financed by health insurance) 48.0% of these were behavioral therapies, 36.0% depth psychology based therapies and 16,0% analytical psychotherapies [45]. This is almost the same distribution of therapies as the entire distribution of therapies held in this time frame. Concerning the professions of the abusing therapists the following picture presents itself: Of the treatments, which began before or in 1990, 50% of the cases were treated by medical and 37.5% by psychological psycho- therapists. In those therapies, which began in 1999 or later, 66.0% of the cases were treated by psychological and 29.8% by medical psychologists, which is equal to the shift in participation in the overall statutory health insurance coverage. Therefore no indications of a preva- lence of a certain type of therapy or profession (doctors vs. psychologists) could be found in the sample of abu- sive therapists. Risk factors are more likely to be found in situational circumstances and especially in the per- sonality variables of the therapists.  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1021 3.2. Problematic Life Situations In 39.5% of all cases, when asked about their knowledge of the private life of the people, who were treating them, the subjects stated problematic aspects (see Table 2). The therapists sometimes tried to evoke the sympathy of their patients by referring to their own problematic situation (n = 4) or their loneliness (n = 3). 3.3. Impression the Patients Had of their Therapy and their Therapists The patients concerned were asked to state their personal impression of their therapists and to describe their looks, charm and personality traits in an open text field. In 44.3% of all cases the therapists were described exclu- sively with positive personality traits. 31.2% stated a very conflicted impression of their therapists and 21.3% of the therapists were described solely by negative traits. Overall 58.9% of all answers given stated positive and 41.1% negative aspects regarding looks and personality traits of the therapists (see Table 3). Based on all the statements of the questioned, the therapists could be classified according to the types wish-fulfilling (74.0%) or revenge (42.1%). 3.4. Consequences of the Sexual Assaults In almost 80% of the cases the persons concerned stated that the therapists initiated the sexual contact. Overall 86.5% of the people who participated in the survey stated that the sexual contact with the therapist had negative consequences for them, of these 93.3% state problematic consequences and only three respondents gave no as an answer to this question. Therewith the results of this study fall in line with the results of the long list of stud- ies, which in the last decades have proven the negative consequences of sexual assaults of therapists on patients [16,33,35]. 3.5. Intensified and New Complaints 60.0% of the questioned stated that after the sexual con- Table 2. Problematic aspects of the therapist’s private life. Problematic Aspects Frequency Divorced/Separated 11 Children from an earlier partnership 9 Problematic Marriage/Partnership 4 Loneliness 4 Stressful experiences in previous life history 4 Financial Problems 2 Other Problems 9 tact with their therapist, complaints, which they had al- ready had at the beginning of the therapy, intensified. Overall up to 7 intensified complaints were named (M = 2.27; SD = 1.89). In 66.0% of the cases it was stated that after the sexual contacts new complaints appeared. The average number of new symptoms was 1.53 (SD = 1.33) (see Table 4). A vivid image of the traumatic quality of the abusive experience in therapy is delivered by the patient’s as- sessment captured by the Impact-of-Event scale, which Table 3. Most frequent descriptions of the therapists. % Positive Attributes (sexually) attractive 34,4 Motherly/vatherly 27,9 Likable, sympathic 26,2 Competent/respectable 23,0 Emphatic/interested 19,7 Charming/jocular 18,0 Self-confident 13,1 Negative attributes unimposing 18,0 (sexually) unattractive 14,8 Domineering, scary 14,8 egocentric, narcissistic 13,1 frightened, helpless 9,8 distanced, critical 8,2 Table 4. Intensified and new complaints as consequences of the sexual contact with the therapist. Most frequent intensified complaints Most frequent new complaints Isolation and emotional retreat (34.6%) Isolation and emotional retreat (30.0%) Mistrust (23.1%) Mistrust (30.0%) Fear and panic (19.2%) Fear and panic (10.0%) Shame and guilt (19.2%) Symptoms of depression (10.0%) Self-doubt and uncertainty (19.2%) Lying/dissimulation (10.0%) Symptoms of depression (10.0%) Anger and aggression (10.0%) Psychosomatic complaints (11.5%) Self injuring behavior  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1022 captures the psychotraumatic quality of an event that occurred in the last 7 days. The results showed that 89.2% were traumatized by the sexual assaults. In over three quarters of all the cases (83.8%) a medium to high trau- matization took place. If one takes a separate look at the symptomatology of the male patients, the following picture presents itself: According to the clinical diagnostic findings, 2 of n = 6 male patients were traumatized medium severely and 2 were highly traumatized. There were however 2 males in the survey, who were classified as clinically incon- spicuous on the basis of the results of the IES-scale. 3.6. Coping and Legal Steps About half (54.0%) of the patients concerned needed another psychotherapy in order to deal with the massive consequences of the sexual contact to their previous therapist. In those cases, where no need for a follow up therapy was stated, the given reason for this was a gen- eral loss of trust in psychotherapists. 25 of the ques- tioned had already completed a follow-up therapy at the time of the survey. It was judged to be very helpful if the following therapist respected borders (professional ab- stinence, for the basic rules of follow-up therapy see [29]). Only very few of the victims of professional sexual abuse considered suing the people who had treated them. Over two thirds (68.8%) stated to have never thought of taking legal steps against their therapist. Mostly this was explained by the questioned as being due to their being afraid of taking these steps or of not having enough courage (n = 5). Also the feeling of complicity stopped them from even thinking of initiating legal steps (n = 4). Three people stated that they saw no point in taking legal action, partially due to either weak evidence or lack of it. In two other cases the patients named the statute of limi- tations as the reason for not having pursued legal options. Those n = 15 persons, who stated having thought of taking legal steps against their therapists, said in most cases that their follow-up therapist provided the impulse for this. Public information on the topic “Sexual Con- tacts in Psychotherapy” provided the impulse for others (n = 5). Another relevant factor was the wish to protect other potential victims (n = 5). In those n = 5 cases, where legal steps were taken, 3 of those cases were criminal lawsuits and 2 were civil law suits. Thus a formal trial only took place or was to take place in three of the cases. At the time of the survey two of the therapists had already been convicted. The third trial has not been held yet. 4. DISCUSSION In by far the largest share of cases (71.2%) the abusing therapists were male. This corresponds to the results of all previous surveys conducted with patients and/or therapists. It is remarkable that in statutory health insur- ance the percentage of practicing female therapists is larger than the percentage of male therapists. For exam- ple in 2003 about 66% of psychotherapists were female [46]. However in the current study in 28.8% of the cases the therapists were female. This comparatively large share can be seen as an indication of the growing amount of sexually abusive female therapists [47] or respectively the fact that more of these cases are being reported. The average age of the therapists was 46.9 (SD = 9.05). The average age of the male therapists does not differ greatly from that of the females. Therefore it is reasonable to assume that in both cases, they are not fresh entrants into the field, but therapists with years of professional experience. This corresponds to the results of the international research literature, which states that most of the abusing therapists are experienced practitio- ners with years of professional experience [18]. An inadequate training of the therapists is not to be discerned in the current sample: in most of the cases the therapists were either university graduated psychologists or doctors (with the relevant practitioner’s title). Fur- thermore the types of therapy that were named most frequently (behavioral therapy and depth psychology based therapy) are all types that are recognized by health insurance. In most of the cases (69.4%) the therapy was also paid for by health insurance, which means that most of the therapists had Approbation (German therapists license necessary for coverage by health insurance). Therefore the scientific literature conclusively shows no indication that abusive therapists have inadequate train- ing. On the contrary it is reported that they are especially well respected and trained [11,13]. Furthermore no indi- cations were found of a prevalence of a certain type of therapy or profession (doctors vs. psychologists). About 40% of the patients concerned knew of current problematic situations in the private life of their thera- pists. In accordance with the international research lit- erature it can be summed up that presumably difficult circumstances in a therapist’s life heighten the risk of sexual contacts with patients. This risk factor however has limited impact on repeat offenders [26], whose se- vere personality disorders are the cause of their behavior. The patients’ evaluations of the looks, charm and per- sonality traits of their therapists show very contradictory findings: A large share of the statements are either con- centrated on very positive or very negative aspects. In 31,2% of the cases the questioned described very con- flicting personality traits of the therapists. It is remark- able that the share of therapists, who are described as having a very ambivalent character, is relatively high.  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1023 Abusing therapists often show dissociative traits [10,29], which is shown by the statements of the surveyed. It can be assumed that the conflicting impression, which the questioned have of their therapist, is less determined by the ambivalent feelings of the patients but rather a result of real decompositions in the personality of the therapist. The fact that current difficult life situations and earlier traumatic experiences are important risk factors of the- rapists is substantiated by the patients’ statements. The different types of therapists discovered by Becker-Fischer and Fischer [10,29] (wish fulfillment and revenge type) can be verified on the basis of the achie- ved results. While male therapists show an equal share of wish fulfillment to revenge type, most of the female therapists fall into the category of wish fulfillment. This result can be explained due to the background of soci- ety’s gender stereotypes: The way that people deal with their own traumatic (childhood) experiences is also de- termined by their gender. It can be assumed that male victims tend more strongly to identify with the perpetra- tors and thus use their patients to still their desire for revenge [29]. The female stereotype is more compatible with the need to be saved by patients as it is characteris- tic for the wish fulfillment type. The described resulting complaints are all part of those of the professional abuse trauma with the leading symptomatic being isolation and emotional retreat, mis- trust, feeling of fear and panic as well as depression, a syndrome that already showed itself in the first survey. In total 86.5% of the people who participated in the sur- vey said that the sexual contact with their therapists had consequences for them. 93.3% of these reported prob- lematic consequences. The described symptoms are com- parable to those, which have been reported in other stud- ies. The basic disturbance of the capacity for love and relationships, which can be determined by those suffer- ing from professional abuse trauma [29], is clearly shown in the named symptoms. Almost 90% of the questioned achieved scores that show an impact on a traumatic scale - a result which is especially precarious, because of the fact that patients of psychotherapy overall and especially those who are vic- tims of sexual abuse during therapy have already had prior traumatic experiences. Often this was sexual abuse in their childhood. In these cases the professional abuse trauma stems from a retraumatization, which leads to an increase of negative consequences. Regarding the consequences of the sexual contacts for male patients it can be stated—although only on the ba- sis of a very small sample—that these basically do not suffer less from the abuse than female victims. In the current study over two thirds of the questioned stated that they never even thought about taking legal steps. Two thirds of those who had thought about initiat- ing legal steps also did nothing. The justification for this was very consistent: Fear of the consequences of such a procedure, the conviction that they would not be be- lieved as well as the assumption that they were complicit in the abuse. These factors were also described by many of those concerned in other surveys of victims [10,31, 39,50]. Furthermore the emotional bond to the abusing therapist in the current results can be seen as a reason for not initiating legal steps. In one case a civil court case was terminated for this reason. According to the background of the descriptions of those concerned in our study it is reasonable to assume, that it is less the lacking knowledge of the possibility of initiating legal steps, which leads to those concerned not employing their legal options [40], but rather emotional factors such as fear and hopelessness, which are respon- sible. Despite the existence of §174c in the StGB the questioned in the current sample only initiated legal steps in n = 5 cases, 3 of which resulted in legal pro- ceedings. Obviously the existence of an applicable para- graph in law does not change much in this regard. It could be understood from the statements of the par- ticipants in the survey that they were filled with a deep mistrust regarding the current legal practices in Germany. Even courts of honor and arbitration boards have the reputation of protecting the therapists in the patients’ opinion. The feeling of having caused the abuse or to be at least partially to blame for it, which is not only present in those, who were victims of sexual abuse in psycho- therapy, but can also be found in many traumatized peo- ple, is not corrected by this situation. In the USA legal options are pursued far more often. A possible explana- tion for this is the establishment of governmental licens- ing agencies, which the victims in the USA mostly turn to first, because they are closest to their interests [10]. They are comprised of a mixture of representatives from members of the respective professions and patients and are lead by civil servants, who decide whether or not the license to practice will be revoked. A comparable body does not exist in Germany. 5. CRITICAL APPRAISEMENT OF METHODS Concerning significance and internal applicability of the results, it must be stated critically that both are depend- ent on the statements of the patients concerned and their subjective assessment. A parallel survey of the relevant therapists however would for obvious reasons meet nearly insurmountable difficulties. With these limitations of the range of significance there is, according to the authors, no further reason not to view the statements of  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1024 the patients as reliable sources of information. The ef- fects of suggestion were eliminated as far as possible in the second survey as well as the first. If one assumes that the only reason for participation is to find a neutral place where one can complain about what happened, then this would lead to a very biased constellation of the sample, for example on the issue of a “tendency to complain”. This conclusion however would only be justifiable if at the same time it were assumed that otherwise motivated people were prevented from participating in the survey or were repelled by it, for example people who were “content” with the sexual contact. There is no reason to assume this. Why should people, who were “content” with the sexual contact not have participated in the sur- vey? Even if for example the call for participation in the survey also appeared in conjecture with content, which negatively depicted sexual contacts in psychotherapy or warned people about it, then this context could just as well have wakened the contradictoriness of the allegedly “content” group. Even for those aggrieved, who have already come to terms with the earlier traumatic experience of sexual abuse in therapy at the time of the survey and whose symptoms have subsided, there are reasons to participate in a survey on this subject. For example the need can exist to use one’s own experiences to contribute to mak- ing the problem public so that other potential victims can be protected from the potentially traumatic consequences of such an event. Finally the detailed congruence of the results of both surveys can also be seen as a criteria for the internal va- lidity of the first and the follow up survey. The alterna- tive explanation for this congruence must be deduced from factors, which are based on suggestibility or in the questioning itself, for which there are no indications. What reason would the participants of an anonymous survey have in describing their experiences so negatively, if this negative depiction were incorrect? Even considering the fact that about 300 new cases of sexual abuse in therapy take place every year, it can be said that a sample size of “only” n = 77 is a good pre- condition for research in a taboo area. It is certainly a sufficient basis for the conclusions, which were drawn in this article. If the number of participants of the first sur- vey is added to that of the current one, then the sample size of n = 138, which is split into 2 separately surveyed partial samples from different points in time, then ac- cording to methodological criteria resilient findings have been achieved. 6. CONCLUSIONS The problem of sexual assaults of therapists on patients and the disastrous consequences for those concerned persists as a constant phenomenon over time, which was shown by the depicted results. The following conse- quences are all among those found in the professional abuse trauma. The findings concerning the situational circumstances of sexual abuse in psychotherapy and psychiatry, which were arrived at in the first research done in the mid-nineties, were also confirmed [10,29]. The conditions in which the surveys were made differ. Nevertheless the same stereotype patterns of interaction between the therapists and the patients, the same risk factors of the therapists and vulnerability factors of the patients as well as the same consequences for those concerned were found. The results suggest a need for more effective informa- tion, prevention and help for the people concerned. Es- pecially the German legal praxis has to be rethought regarding aspects such as statutes of limitations, the cri- teria for reality and truthfulness according to the psy- chology of statements (see [48]) or the perpetrator ori- ented nature of many criminal proceedings (see [41]). Of decisive importance for the prevention of sexual abuse of patients by therapists is the education of experts and the public about the problems inherent in sexual abuse in a therapeutic relationship [41]. This includes the permanent integration of relevant thematic content into the curricula of psychotherapeutic education and training. For prevention it is at least as important to educate potential victims, namely the patients of psy- chotherapy. American authors propose for example leaf- lets with information about patients’ rights as well as ethical guidelines, which contain detailed examples of ethical vs. unethical behavior. These procedural methods would also make sense for Germany. A further contribu- tion can be made by the media by communicating a re- alistic impression of professional goals and aims as well as the borders of psychotherapy [50,51]. REFERENCES [1] Ehlert-Balzer, M. (1999) Fundament in Frage gestellt. Sexuelle Grenzverletzungen in der Psychotherapie. Ma- buse, 121, 47-51. [2] Arnold, E., Vogt, I. and Sonntag, U. (2000) Umgang mit Sexueller Attraktivität und Berichten über Sexuelle Kontakte in Psychotherapeutischen Beziehungen. Zeits- chrift für Klinische Psychologie, Psychiatrie und Psy- chotherapie, 48(1), 18-35. [3] Bouhoutsos, J., Holroyd, J., Lerman, H., et al. (1983) Sexual intimacy between psychotherapists and patients. Professional Psychology Research Practice, 14(2), 185- 196. [4] Gartrell, N., Herman, J., Olarte, S., et al. (1987) Report- ing practices of psychiatrists who knew of sexual mis- conduct by colleagues. American Journal of Orthopsy-  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1025 chiatry, 57(2), 287-295. [5] Koller, R. (1999) Sexuelle Kontakte in der Psychotherapie: Einstellung zu Sexuellen Kontakten und Praktische Erfahrungen mit Sexuellen Kontakten. Unpublished Ma- sterthesis, University Zürich, Zürich. [6] Pope, K. and Vetter, V. (1991) Prior therapist-patient sexual involvement among patients seen by psycholo- gists. Psychotherapy, 28(3), 429-438. [7] Stake, J. and Oliver, J. (1991) Sexual contact and touching between therapist and client: A survey of psychologists’ at- titudes and behavior. Professional Psychology Research Practice, 22(4), 297-307. [8] Kuchan, A. (1990) Survey of incidence of psychothe- rapists’ sexual contact with clients in Wisconsin. In: Schoener, G., Ed., Psychotherapists’ Sexual Involvement with Clients: Intervention and Prevention, Walk-In Counseling Center, Minneapolis, 51-64. [9] Parsons, J. and Wincze, J. (1995) A survey of client- therapist sexual involvement in Rhode Island as reported by subsequent treating therapists. Professional Psychology Research Practice, 26(2), 171-175. [10] Becker-Fischer, M. and Fischer, G. (1997) Sexuelle Übergriffe in Psychotherapie und Psychiatrie. Schriftenreihe des Bundesministeriums für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, Band 107. Kohlhammer, Köln. [11] Gartrell, N., Herman, J., Olarte, S., et al. (1986) Psy- chiatrist-patient sexual contact: Results of a national survey, I: Prevalence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143(9), 1126-1131. [12] Schoener, G., Milgrom, J. and Gonsiorek, J. (1984) Sex- ual exploitation of clients by therapists. Women & Ther- apy, 3(3-4), 63-69. [13] Chesler, P. (1986) Sexuelle Beziehungen zwischen Patientin und Therapeut. In: Chesler, P., Ed., Frauen— das Verrrückte Geschlecht? Rowohlt, Reinbek, 134-157. [14] Disch, E. and Avery, N. (2001) Sex in the consulting room, the examining room, and the sacristy: Survivors of sexual abuse by professionals. American Journal of Or- thopsychiatry, 71(2), 204-217. [15] Somer, E. and Nachmani, I. (2005) Constructions of therapist-client sex: A comparative analysis of retros- pective reports. Sex Abuse, 17(1), 47-62. [16] Somer, E. and Saadon, M. (1999) Therapist-client sex: Clients’ retrospective reports. Professional Psychology Research Practice, 30(5), 504-509. [17] Pope, K. and Bajt, T. (1988) When laws and values con- flict: A dilemma for psychologists. American Psychologist, 43(10), 828-829. [18] Lamb, D., Catanzaro, S. and Moorman, A. (2003) Psy- chologists reflect on their sexual relationships with cli- ents, supervisees and students: Occurrence, impact, ra- tionales, and collegial intervention. Professional Psy- chology Research Practice, 34(1), 102-107. [19] Reschke, K. and Kranich, U. (1996) Sexuelle Gefühle und Phantasien in der Psychotherapie. Verhaltenstherapie und Psychosoziale Praxis, 28(2), 251-271. [20] Thoreson, R., Shaughnessy, P., Heppner, P., Cook, S. (1993) Sexual contact before and after the professional relationship: Attitudes and practices. Journal of Coun- seling and Development, 71, 429-434. [21] Butler, S. and Zelen, S. (1977) Sexual intimacies be- tween therapists and patients. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 14(2), 139-145. [22] Rodolfa, E., Hall, T., Holms, V., et al. (1994) The man- agement of sexual feelings in therapy. Professional Psychology Research Practice, 25(2) , 168-172. [23] Celenza, A. (1991) The misuse of countertransference love in sexual intimacies between therapists and patients. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 8(4), 501-509. [24] Dahlberg, C. (1970) Sexual contact between patient and therapist. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 6, 107-124. [25] Schmidbauer W. (1997) Wenn Helfer Fehler machen. Rowohlt, Reinbek. [26] Wirtz, U. (1994) Therapie als sexuelles Agierfeld. In: Bachmann, K. and Böker, W., Eds., Sexueller Mißbrauch in Psychotherapie und Psychiatrie, Huber, Bern, 33-44. [27] Jackson, H. and Nuttall, R. (2001) A relationship be- tween childhood sexual abuse and professional sexual misconduct. Professional Psychology Research Practice, 32(2), 200-204. [28] Pope, K., Levenson, H. and Schover, L. (1979) Sexual intimacy in psychology training: Results and implications of a national survey. American Psychologist, 34(8), 682- 689. [29] Becker-Fischer, M. and Fischer, G. (1996) Sexueller Missbrauch in der Psychotherapie – was tun? Orien- tierungshilfen für Therapeut und Klientin. Asanger, Heidelberg, 2008. [30] Apfel, R. and Simon, B. (1985) Patient-therapist sexual contact. I.: Psychodynamic perspectives on the causes and results. Psychotherapy Psychosomatics, 43(2), 57- 62. [31] Ben-Ari, A. and Somer, E. (2004) The aftermath of the- rapist-client sex: Exploited women struggle with the consequences. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 11(2), 126-136. [32] Disch, E. (2006) Sexual victimization and revictimiza- tion of women by professionals: Client experiences and implications for subsequent treatment. Women & Therapy, 29(1-2), 41-61. [33] Feldman-Summers, S. and Jones, G. (1984) Psychological impacts of sexual contact between therapists or other health care practioners and their clients. Journal of Con- sulting & Clinical Psychology, 52(6), 1045-1061 [34] Luepker, E. (1999) Effects of practioners’ sexual miscon- duct: A follow-up study. Journal of the American Acad- emy of Psychiatry and the Law, 27(1), 51-63. [35] Moggi, F. and Brodbeck, J. (1997) Risikofaktoren und Konsequenzen von sexuellen Übergriffen in Psycho- therapie. Zeitschrift fur Klinische Psychologie, Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 26(1), 50-57. [36] Wohlberg, J., McCraith, D. and Thomas, D. (1999) Sex- ual misconduct and the victim/survivor: A look from the inside out. In: Bloom, J., Nadelson, C. and Notman, M., Eds., Physician Sexual Misconduct, American Psychiat- ric Press, Washington, D.C., 181-204. [37] Pope, K. (1988) How clients are harmed by sexual con- tact with mental health professionals: The syndrome and its prevalence. Journal of Counseling and Development, 67(4), 222-226. [38] Pope, K. and Bouhoutsos, J. (1992) Als hätte ich mit einem Gott geschlafen. Sexuelle Beziehungen zwischen Therapeuten und Patienten. Hoffmann und Campe, Ham- burg.  C. Eichenberg et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1018-1026 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1026 [39] Benowitz, M. (1991) Sexual exploitation of female Cli- ents by female Psychotherapists: Interviews with clients and a comparison to women exploited by male psycho- therapists. PhD. dissertation, University of Minnesota, Dissertation Abstracts International 52(5-B), AAT9130138. [40] Vinson, J. (1987) Use of complaint procedures in cases of therapist-patient sexual contact. Professional Psy- chology Research Practice, 18(2), 159-164. [41] Tschan, W. (2005) Missbrauchtes Vertrauen. Sexuelle Grenzverletzungen in professionellen Beziehungen. Ur- sachen und Folgen, Karger, Basel. [42] Eichenberg, C. (2007) Das Internet als Medium wissen- schaftlicher Tätigkeit. Eine Untersuchung im Fach Kli- nische Psychologie am deutschsprachigen Universitäten. VDM-Verlag, Saarbrücken. [43] Ott, R. and Eichenberg, C. (2003) Klinische Psychologie und Internet. Potenziale für Klinische Praxis, Interv- ention, Psychotherapie und Forschung. Hogrefe, Göttin- gen. [44] Bandilla, W. (1999) WWW-Umfragen – Eine alternative Datenerhebungstechnik für die empirische Sozialforschung? In: Batinic, B., Werner, A., Gräf, L. and Bandilla, W., Eds., Methoden, Anwendungen und Ergebnisse, Hogrefe, Göttingen, 9-19. [45] Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (2002) Grunddaten zur vertragsärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland 2002. http://www.kbv.de/publikationen/125.html [46] Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (2004). Grunddaten zur vertragsärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland 2004. http://www.kbv.de/publikationen/125.html [47] Gabbard, G. (1994) Psychotherapists who transgress sex- ual boundaries with patients. Bull Menninger Clinic, 58(1), 124-135. [48] Hinckeldey, S. and Fischer, G. (2002) Psycho traumatologie der Gedächtnisleistung. Reinhardt, München. [49] Kagle, J. and Giebelhausen, P. (1994) Dual relationships and professsional boundaries. Social Work, 39(2), 213-220. [50] Simon, R. (1989) Sexual exploitation of patients: How it begins before it happens. Psychiatric Annals, 19(2), 104- 112. [51] Strasburger, L., Jorgenson, L. and Sutherland, P. (1992) The prevention of psychotherapist sexual misconduct: Avoiding the slippery slope. American Journal of Psy- chotherapy, 46(4), 544-555. |