Paper Menu >>

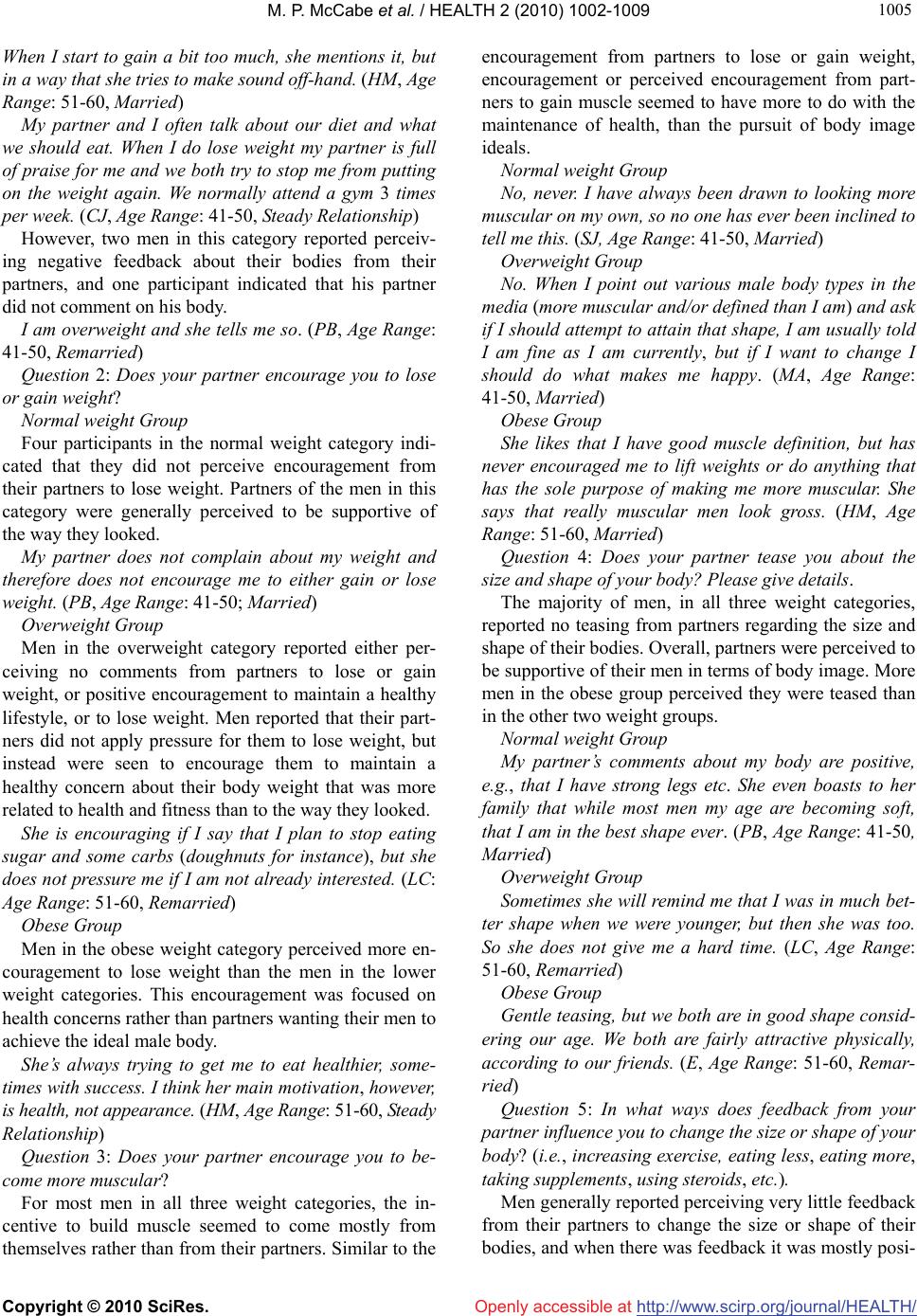

Journal Menu >>

Vol.2, No.9, 1002-1009 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.29148 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ The role of partners in shaping the body image and body change strategies of adult men ——Partners and male body image Marita P. McCabe*, Shauna McGreevy School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia; *Corresponding Author: marita.mccabe@deakin.edu.au Received 30 March 2010; revised 29 April 2010; accepted 5 May 2010. ABSTRACT The current study examined the relationship between perceived messages about the bodies of adult men from their sexual partners and the actual body image of these men. Interviews were conducted among 38 middle-aged men. Feedback from partners was generally compli- mentary, and the men were generally positive about their body image. Partners were seen to be more focused on a healthy body rather than a physically attractive body. The implications of these findings for better understanding the so- cial influence on adult men to obtain a healthy body weight are discussed. Keywords: Men; Body Image; Partners; Qualitative 1. INTRODUCTION A growing body of literature has demonstrated that the ideal body form for males is slim and muscular [1], and that males receive messages from a range of sources to achieve this ideal [2-4]. Most of this past research has been conducted with adolescent boys, and has demon- strated that adolescent boys are particularly focused on obtaining a lean muscular body [5]. Messages to achieve this body shape come from parents, peers and the media [6]. In a recent review of the nature of the body image of males, and the factors that contribute to males’ body image, Gray and Ginsberg [7] found a strong preference for a muscular body among both Western and non- Western males. There have been limited studies on the sociocultural influences on the body image of adult men. The limited research that is available suggests that they are aware of the sociocultural body ideal for men, and they have similar body image concerns to those of adolescent boys [1]. Grogan and Richards [8] found that boys and men in all age groups drew a relationship between muscularity and masculinity. Rather than focusing on appearance in its own right, they focused more on how their bodies looked in relation to function, fitness and health. Grogan [8] expanded this view further in her review of studies of men’s body image and concluded that a large aspect of male body image relates to functionality, rather than appearance. The above research has not examined if the nature of the messages that men receive about their body, in terms of weight and muscularity, are different according to their weight. Certainly, Luciano [10] suggested that body weight would appear to influence the level of body dis- satisfaction experienced by men. Davison and McCabe [1] found that poor body image was related to problems in social and sexual functioning among middle-aged men, and to depression and anxiety among older men. These results suggest that, at least for middle aged men, their sexual partner may play some role in shaping their body image. The current study was designed to explore the nature of the messages from the partner about the man’s body, and how these messages varied according to the man’s body size. Previous research has suggested that sexual partners may provide a significant source of appearance-related information to men [11]. Feedback from significant oth- ers may contribute to men’s perceptions of body image, through criticism or compliments, and partners may pro- vide a point of reference through which men derive their level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their bodies [11]. Sheets and Ajmere [12] also found that male and female romantic partners reported telling each other to lose or gain weight. Women were more likely to tell their male dating partners to gain weight, whereas men would typically tell their female partners to either gain or lose weight. Married men may be more motivated by their own need to possess the ideal male physique than by their wives’ opinion of their bodies [13]. A comparison between mar-  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 100 1003 ried and single couples found that married couples were far less concerned that their husband or wife possessed the ideal body physique than did single couples [13]. Although the above studies examined the nature of messages from partners, very few studies have investi- gated the relationship between men’s body image and how messages from sexual partners are associated with men’s perception of their bodies and how they subse- quently try to change their body shape and weight. Studies have shown that men, like women, place a great deal of importance on their appearance [14,15], and may report dissatisfaction with their bodies if they perceive that their current image does not live up to the socially-acce- pted ideal body for men [16,17]. The use of maladaptive body-change strategies by men, such as steroids and ex- cessive exercise, has increased in recent years, as men attempt to attain and maintain the V-shaped male physique [9,14]. It is therefore important to obtain a better under- standing of the types of messages that men receive about their bodies, and how these messages are interpreted. The aim of the current study was to explore the rela- tionship between perceived messages from sexual part- ners and body image in men. Of particular interest was the nature of the messages that men receive about their bodies from their sexual partners, and how these mes- sages influenced men to change their weight and shape. A qualitative methodology was adopted to obtain a de- tailed understanding of the nature of the messages that men reported they received from their partners. 2. METHODS 2.1. Participants Of the 38 men who participated in this study, 22 were aged 51 to 60 years and 16 were aged between 41 and 49 years. A requirement of the study was that men were currently engaged in a heterosexual relationship. Nine of these men were in a steady relationship, 14 were married for the first time, six were remarried, eight were either divorced or separated, and one was widowed. Twenty two of the participants were employed in a profes- sional/managerial capacity, three worked in education, four were employed in the health sector, five were re- tired, and two were employed in sales. Twenty five of the participants listed their country of birth as the United States of America, and 13 were born in Australia. Al- though it was not possible to formally analyze the dif- ference between the responses of men from the United States and Australia, the manner in which the themes clustered for the two groups did not demonstrate any apparent difference in the responses of men from the two countries. 2.2. Materials The open-ended interviews consisted of eight questions relating to perceived messages about their body received from participants’ sexual partners, the impact of these messages on their body image, as well as questions re- lating to men’s perceptions of the sociocultural pressures on males to conform to idealized standards of the male physique. The questions were developed from the litera- ture and were designed to examine the perceived influ- ence of partners on a man’s body image and his body change strategies. The questions are listed in the Results section. Men were encouraged to expand on their an- swers and provide additional information to support their initial response. 2.3. Procedure Approval to complete the study was obtained from the University Human Ethics Committee. Participants were recruited by placing information about the study on a range of web sites in United States of America and Aus- tralia. Fifty websites were located in each of these two countries, information about the study was provided, and men were asked to complete an anonymous question- naire about the types of messages they perceived their partner’s communicated to them about the body. It was a requirement for the study that the men were between 40 and 60 years of age, and were currently engaged in a relationship. Men were asked to answer the open-ended questions on their body image on line. Participants were advised that participation was voluntary and that they would be able to withdraw from the study at any time. There was no reimbursement for participation in the study. Men were asked to provide their height and weight so that their Body Mass Index (BMI) could be calculated. Men also provided information on their age, marital status, occupation, and country of birth. 3. RESULTS Given the importance of BMI on body dissatisfaction, respondents were organized into three BMI groups: BMI less than 25 (normal weight), BMI 25 to 29.99 (over- weight), and BMI 30 + (obese). There were eight par- ticipants in the normal weight group, 16 participants in the overweight group, and 14 participants in the obese group. For each of the eight questions, the results were organized into the themes that emerged for respondents from each of the three BMI groups. Responses were read by the two authors, and they independently determined the themes that emerged from each question. The themes from each of the questions were considered separately. A grounded theory approach [18] was used to guide the  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1004 interpretation of the data due to the limited previous re- search on partner influence on male body image. Within this approach pre-coded categories are not used. It is the categories that emerge from the narratives that are ex- plored and subsequently coded. The authors then met to discuss the concordance or otherwise of the themes that they determined had emerged from the data. There was a high level of concordance in the nature of these themes, since the questions largely shaped the nature of the themes that emerged from the data. Discussion between the two authors and some re-reading of the transcripts resulted in an agreement on the themes that are reported in this paper. The main themes for each of the questions are included in Table 1. Question 1: Do you receive any feedback from your partner regarding the size and shape of your body? Normal weight Group The perceived feedback from partners (both female and male) was mostly positive for the men in this group, with some men perceiving they received complimentary feedback from partners about their bodies, particularly regarding certain aspects of their bodies such as their abdominal muscles, their buttocks, and their overall muscle tone. I do receive feedback from my partner. Usually it is positive as I am in good shape and I exercise regularly. (PB, Age Range: 41-50, Married) However, even men who were of normal body weight and who perceived positive feedback from their partners were concerned if they perceived that they did not live up to the muscular male body ideal. She says that she likes my body and the way I look. She makes jokes sometimes, and that makes it hard. She’ll say that she likes this other guy’s body, because it is so muscular and he’s so strong. When she says this, I feel bad that I’m not as muscular and strong. (PM, Age Range: 41-50, Steady Relationship) Overweight Group Most of the men’s partners in this group were per- ceived complimentary about their partners’ bodies, or were encouraging of their partners’ strategies to get back into shape (e.g., dieting). The majority of the participants in this group indicated that they were happy with their bodies. Yes—they think I’m hot. The things I might be most self-conscious about are what turn them on the most (my beer belly and being very hairy)! (MH, Age Range: 51-60, Single) My wife generally allows me to take care of what’s mine with minimal interference (and appreciates when I do the same). Even so, she’s commented that she thinks I’m very handsome, likes that I’m tall, has seemed satis- fied with my weight at all points in our relationship. (CC: Age Range: 51-60, Married) Obese Group Comments from partners were perceived to be en- couraging of good health rather than being directed at achieving the muscular male ideal. Participants reported that even when body change strategies were warranted, partners were perceived to be encouraging of their ef- forts rather than disparaging. Yes, my wife of 40 years tells me I’m in great shape. Table 1. Main themes identified by men in different weight categories. Theme Normal weight n = 8 Overweight n = 16 Obese n = 14 Positive feedback 6 14 10 Concern about muscular ideal 2 - 4 Negative feedback - - 2 Encouragement to lose weight 4 2 8 Encouragement to build muscles 3 6 5 Encouragement to be healthy 5 11 10 Teasing 1 3 7 Encouragement to change shape of body 2 4 4 More pressure on men now compared to previously 7 14 13 Pressure coming from media 7 14 13 Pressure coming from friends 1 4 4 Positive body image 7 13 10 Negative body image 1 3 4  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 100 1005 When I start to gain a bit too much, she mentions it, but in a way that she tries to make sound off-hand. (HM, Age Range: 51-60, Married) My partner and I often talk about our diet and what we should eat. When I do lose weight my partner is full of praise for me and we both try to stop me from putting on the weight again. We normally attend a gym 3 times per week. (CJ, Age Range: 41-50, Steady Relationship) However, two men in this category reported perceiv- ing negative feedback about their bodies from their partners, and one participant indicated that his partner did not comment on his body. I am overweight and she tells me so. (PB, Age Range: 41-50, Remarried) Question 2: Does your partner encourage you to lose or gain weight? Normal weight Group Four participants in the normal weight category indi- cated that they did not perceive encouragement from their partners to lose weight. Partners of the men in this category were generally perceived to be supportive of the way they looked. My partner does not complain about my weight and therefore does not encourage me to either gain or lose weight. (PB, Age Range: 41-50 ; Married) Overweight Group Men in the overweight category reported either per- ceiving no comments from partners to lose or gain weight, or positive encouragement to maintain a healthy lifestyle, or to lose weight. Men reported that their part- ners did not apply pressure for them to lose weight, but instead were seen to encourage them to maintain a healthy concern about their body weight that was more related to health and fitness than to the way they looked. She is encouraging if I say that I plan to stop eating sugar and some carbs (doughnuts for instance), but she does not pressure me if I am not already interested. (LC: Age Range: 51-60, Remarried) Obese Group Men in the obese weight category perceived more en- couragement to lose weight than the men in the lower weight categories. This encouragement was focused on health concerns rather than partners wanting their men to achieve the ideal male body. She’s always trying to get me to eat healthier, some- times with success. I think her main motivation, however, is health, not appearance. (HM, Age Range: 51-60, Steady Relationship) Question 3: Does your partner encourage you to be- come more muscular? For most men in all three weight categories, the in- centive to build muscle seemed to come mostly from themselves rather than from their partners. Similar to the encouragement from partners to lose or gain weight, encouragement or perceived encouragement from part- ners to gain muscle seemed to have more to do with the maintenance of health, than the pursuit of body image ideals. Normal weight Group No, never. I have always been drawn to looking more muscular on my own, so no one has ever been inclined to tell me this. (SJ, Age Range: 41-50, Married) Overweight Group No. When I point out various male body types in the media (more muscular and/or defined than I am) and ask if I should attempt to attain that shape, I am usually told I am fine as I am currently, but if I want to change I should do what makes me happy. (MA, Age Range: 41-50, Married) Obese Group She likes that I have good muscle definition, but has never encouraged me to lift weights or do anything that has the sole purpose of making me more muscular. She says that really muscular men look gross. (HM, Age Range: 51-60, Married) Question 4: Does your partner tease you about the size and shape of your body? Please give details. The majority of men, in all three weight categories, reported no teasing from partners regarding the size and shape of their bodies. Overall, partners were perceived to be supportive of their men in terms of body image. More men in the obese group perceived they were teased than in the other two weight groups. Normal weight Group My partner’s comments about my body are positive, e.g., that I have strong legs etc. She even boasts to her family that while most men my age are becoming soft, that I am in the best shape ever. (PB, Age Range: 41-50, Married) Overweight Group Sometimes she will remind me that I was in much bet- ter shape when we were younger, but then she was too. So she does not give me a hard time. (LC, Age Range: 51-60, Remarried) Obese Group Gentle teasing, but we both are in good shape consid- ering our age. We both are fairly attractive physically, according to our friends. (E, Age Range: 51-60, Remar- ried) Question 5: In what ways does feedback from your partner influence you to change the size or shape of your body? (i.e., increasing exercise, eating less, eating more, taking supplements, using steroids, etc.). Men generally reported perceiving very little feedback from their partners to change the size or shape of their bodies, and when there was feedback it was mostly posi-  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1006 tive. A common theme among the three BMI groups was self-motivation to get into/stay in shape, rather than wanting to change their shape for someone else. How- ever, a number of men reported being influenced by their perceptions of their partners’ opinion of their bodies, even if their partner’s opinion was not voiced directly. None of the men, in any of the three BMI groups, re- ported using steroids to change their body shape. Normal weight Group Since she says nothing either complimentary or nega- tive, I do what I think I need to do for good health. I do it for myself and to look good among other men. (HL, Age Range: 51-60, Married) Overweight Group It does not influence me, although I think that it is important for a man to feel that he is attractive to/want- ed by women. I am happy to receive a positive compli- ment and my self-esteem gets a boost. (SB, Age Range: 41-50, Steady Relationship) Obese Group I can tell when she’s checking me out physically. When she compliments my appearance, that’s a big factor in- fluencing me to keep working at it. (HM, Age Range: 51-60, Married) Question 6: Do you think there is more or less pres- sure on men these days to be slimmer and more muscu- lar than ever before? There was a general consensus from the men in all three BMI groups that there is more pressure on men today to conform to a particular body type, i.e., to be slimmer and more muscular or toned. Men generally thought this pressure came from the media: billboards, television, and movies. Some men acknowledged that this pressure had a negative effect on their own body image, in that they felt they had to try to live up to the unrealistic images that they saw displayed in the media. Others indicated that the pressure ‘to be perfect’ had the effect of portraying those who do not fit the ‘profile’ as less than competent or stupid. Some of the men even acknowledged that the pressure on men to conform to a body ideal is similar to the amount of pressure on women to conform to a female body ideal. Normal weight Group More! (pressure). I noticed today the models that clothing companies use to advertise underwear – abso- lutely PERFECT in every way! So even though I know it’s bullshit, there is still a part of me that compares what I see in the mirror with what I see in the media and thinks that I have to live up to it. (NB, Age Range: 41-50 , Divorced/Separated) Overweight group I feel that due to reality TV shows like Survivor and The Biggest Loser there is a standard of male muscular- ity and fitness to be achieved, and that those with less, i.e., the more overweight and less fit, or less ability to hit that standard, are viewed as liabilities to be eliminated. (MA, Age Range: 41-50, Married) Obese Group Yes. I think there is more pressure on men, particu- larly younger men, from movies, TV, and magazines. I know that I feel guilty about being a few kilos over- weight and that my dad or my uncles would never have felt that way at all. Overweight people are often por- trayed as stupid or incompetent or comic. You can’t avoid those enormous outdoor billboards with bulging pecs and bulging briefs. (RM, Age Range: 51-60, Mar- ried) Question 7: Where is this pressure coming from? (i.e., Men’s magazines, Television, Movies, friends, other in- fluences, etc.) Most men saw the added pressure on today’s males as coming from the media, television, movies, and bill- boards. Some men also indicated that pressure has seen to come from both same and opposite sex friends. A few participants thought that there was pressure exerted on men to be healthier due to media health messages to re- duce obesity. Others felt that indirect pressure was ex- erted on men via images of perfect male bodies dis- played in women’s magazines. Normal weight Group All of the above (men’s magazines, television, movies, friends, other influences): part of a total cultural/gene- rational shift. In my opinion, Western culture has reach- ed something of a hiatus, and values espoused are rep- resentative of an increasing shallowness in our culture. (BP, Age Range: 41-50, Steady Relationship) Overweight Group I think the pressure comes mainly from friends, espe- cially the opposite sex. In previous generations, women were more economically dependent on men, and men could attract the attention of women, and status among men, by being financially successful, even if he wasn’t especially fit. Now however, women don’t need men as much for financial reasons, and so men are starting to compete for attention and status in other ways, such as physical fitness. (LM, Age Range: 41-50, Married) Obese Group I would say that the companies who use advertising use every avenue they can to put their products in front of men. Everywhere you look there are ads to improve the styles. All the models are young, fit, and good-looking. My observations suggest that companies are wasting their money. Health and fitness, I am afraid, is not win- ning this contest. (CJ, Age Range: 41-50, Steady Rela- tionship) Question 8: How do you think the pressure on men to  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 100 1007 be slimmer and/or more muscular makes you feel about your body? Answers to this question were mixed. Societal pres- sure to conform to an ideal body type left a majority of these men feeling quite negative about their bodies, while a minority of others reported positive conse- quences. In general, men in the normal weight group felt more positive about their bodies than men in the heavier BMI groups, however, this was not always the case. Some lighter men reported body dissatisfaction, and some heavier men reported being satisfied with their bodies. In some cases, the perceived pressure on men to conform to slimmer/more muscular body ideals had quite a profound, negative effect on men’s perceptions of themselves and their bodies. Normal weight Group I’m aware that I’m relatively ‘skinny’ (6 feet and about 80 kilos) but I feel quite good about my body. (LP, Age Range: 51-60, Divorced/Separated) I sometimes feel ‘lazy’ that I’m not at the gym 3 days a week working to get rid of that extra 4 or 5 pounds. My body is not the ‘enemy’ but media messages keep re- minding me that I’m not doing everything possible to be part of that slim, active, fit demographic. (WB, Age Range: 41-50, Divorced/Separated) Overweight Group I’m more self-conscious that I do not have the ‘per- fect’ male body and women do not see me as attractive, and that makes me feel less needed. It is also a factor in my inability to maintain a relationship with a women. (DN, Age Range: 41-50, Steady Relationship) It makes me feel like I should be in better shape, and have a washboard stomach, and bigger muscles. (RB, Age Range: 51-60, Married) Obese Group I feel that pressure. I feel it in the dating scene. How- ever, for me it is more of a health issue, as I have had a triple by-pass and am in need of losing weight to protect and care for my heart. (BE, Age Range: 51-60, Di- vorced/Separated ) Just fine. I have never been interested in fads or trends and I have never been fashionable, and being me is about all I have time for. (MJ, Age Range: 51-60, Steady Relationship) 4. DISCUSSION All three BMI groups of men indicated that they per- ceived mostly positive feedback about their size and shape from their partners regardless of their body weight. There were no obvious differences in the perception of partner comments in terms of marital status. Men in the normal weight group reported receiving complimentary comments about particular aspects of their bodies (i.e., abdominal muscles, buttocks, muscle tone). Men in the overweight category perceived similar complimentary comments, or partners who were encouraging of men’s strategies to get into shape (e.g., dieting). Men in the overweight group were also generally happy with their bodies. Positive and complimentary comments from partners were similarly reported by the men in the obese weight category, with partners perceived to be encour- aging good health rather than pushing men to attempt to achieve the ideal male body. These results are consistent with Ogden and Taylor’s [11] comments that sexual partners may provide a significant source of appearance- related information to men, and that this feedback is likely to contribute to men’s perceptions of their body image through criticism or compliments, Men in the normal weight group reported that their partners were generally supportive of the way they looked. The men in this group indicated that they did not receive pressure from their partners to lose weight, but instead were encouraged by their partners to maintain a healthy concern about their body weight that was more related to health and fitness than achieving the idealized male physique. Men in the obese group generally per- ceived more encouragement from partners to lose weight than men in the lower weight groups. However, these men also reported that the focus of comments to lose weight from partners was for concerns about health rather than wanting their men to work towards an unob- tainable body shape. These results are inconsistent with previous research by Grogan [9] who found that men were more focused on health than appearances. Further, Sheets and Ajmere [12], who found that dating partners reported telling each other to lose or gain weight: Women were more likely to encourage their male partners to gain weight, while men were more likely to tell their female partners to lose weight. Perhaps the discrepancy between the re- sults from the present study and past research can be explained by age. The majority of men in the present study were aged over 50 years of age and were likely to be in longer-term, more stable relationships than those in Sheets and Ajmere’s [12] study, who were drawn from a college population. Age and length of the relationship may be associated with less concern over appearance and more concern with health and well being. Tom et al. [13] found that having a long-lasting relationship re- duced the importance of body image dissatisfaction as well as the impact of unrealistic body image ideals. Men in all three weight categories reported that the incentive to build muscle came mostly from themselves rather than from their partners. Perceived encouragement from partners seemed to be positive and centered around  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1008 the maintenance of good health rather than the pursuit of a muscular body. The majority of men across the three weight categories reported no teasing from partners about their size or shape. Some men, however, reported that they experienced teasing from partners, ranging from gentle teasing comments to more hurtful remarks. Men in the obese weight category reported more teasing comments than men in the other two weight categories. Further research in this area is needed in order to gain a clearer understanding of the extent of partner teasing on body image and the ways is which this may influence men to use body-change strategies to change their shape. The majority of men in this study, across all three BMI groups, agreed that men are under more pressure now to conform to a particular body type, than in the past. Consistent with a previous review of research ex- amining body image across the lifespan [5], most men thought that this pressure came from the media, adver- tising, billboards, television, magazines, and movies, but not so much from friends or their partner. However, oth- ers implicated same and opposite sex friends as convey- ors of social attitudes about male body image. Consistent with findings by Grogan [9], most men acknowledged that this pressure had a negative effect on their own body image, in that they felt that they were expected to live up to unrealistic images that are portrayed in the media. These results are consistent with findings with women that highlight the important role played by the media in shaping their body image [9]. Overall, the perceived influence of sexual partners on male body image in this study was positive. Most part- ners were perceived to be supportive of men’s actual body shape and/or weight and did not actively encourage the pursuit of the idealized, slim and muscular male physique. If partners were perceived to encourage body change, the reasons were generally motivated by con- cerns for health, rather than appearance, and these mes- sages were perceived to be conveyed through gentle en- couragement rather than through teasing. Very few men reported teasing comments regarding their bodies from partners. Men who did pursue a more muscular or toned body did so as a result of their own desire to be more toned or muscular, rather then being actively persuaded to conform to the idealized male physique by their part- ners. The men in this study almost unanimously agreed that men are generally under a great deal of pressure to conform to the V-shape, muscular male body. However, most men also indicated a positive body image. This is in contrast to research with women that has demon- strated a high level of body dissatisfaction [9]. The results of this study demonstrate the association between perceived messages received by adult men from partners and other sociocultural influences on their body image. The findings indicate that men generally feel quite positive about their bodies, and that strategies to change their bodies are primarily motivated by health related concerns. This finding has important implications for interven- tions to address body image concerns among men. Given that men have such a strong focus on health related con- cerns, and they perceive their partners also to be focused on their health, interventions need to focus on changing men’s bodies to be more healthy rather than more attrac- tive. This approach is quite different from women, who are more focused on the appearance, rather than the function of their body. It is important to replicate this study with a larger sample of adult men, across a broader range of cultural groups, and to determine if these find- ings also apply for homosexual men. Information on the ethnic group of the respondents in the current study, or if they lived in the urban or rural locations was also not provided. It is possible that responses may have varied for men from these different groups. In the current study, men ticked an age category rather than reporting their actual age. Future research should obtain the actual age of participants. The sample in the current study was re- stricted to men who had access to the internet, and so was not representative of many adult men. Future studies also need to determine the level of muscularity of men, since high BMI may be reflective of high levels of mus- cularity and not obesity in some men. It is not possible to generalize these findings to adult men more broadly, and so it is important to investigate the role of partners on men’s body image with a larger, more representative group of men. REFERENCES [1] Davison, T.E. and McCabe, M.P. (2005) Relationships between men’s and women’s body-image and their psy- chological, social and sexual functioning. Sex Roles, 52 (7-8), 463-475. [2] Abrams, L.S. and Cook Stormer, C. (2002) Socio-Cultural variations in the body-image perceptions of urban ado- lescent females. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(6), 443-450. [3] Cusumano, D.L. and Thompson, J.K. (1997) Body-image and body shape ideals in magazines: Exposure, aware- ness and internalisation. Sex Roles, 37(9-10), 701-722. [4] Thompson, J.K. and Cafri, G. (2007) The muscular ideal. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C. [5] McCabe, M.P. and Ricciardelli, L.A. (2004) Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan: A review of past literature. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(6), 675-685. [6] McCabe, M.P. and Ricciardelli, L.A. (2001) Parent, peer and media influences on body image and strategies to both increase and decrease body size among adolescent  M. P. McCabe et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 1002-1009 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 100 1009 boys and girls. Adolescence, 36(142), 225-240. [7] Gray, J.J. and Ginsberg, R.L. (2007) Muscle dissatisfac- tion: An overview of psychological and cultural research and theory. In: Thompson, J. K. and Cafri, G., Eds., The Muscular Ideal, American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., 15-40. [8] Grogan, S. and Richards, H. (2002) Body image: Focus groups with boys and men. Men and Masculinities, 4(3), 219-232. [9] Grogan, S. (2008) Body Image. Routledge, New York. [10] Luciano, L. (2007) Muscularity and masculinity in the United States: A historical overview. In: Thompson, J. K. and Cafri, G., Eds., The Muscular Ideal, American Psy- chological Association, Washington, D.C., 41-66. [11] Ogden, J. and Taylor, C. (2000) Body dissatisfaction within couples. Journal of Health Psychology, 5(1), 25- 32. [12] Sheets, V. and Ajmere, K. (2005) Are romantic partners a source of college students’ weight concern? Eating Be- haviors, 6(1), 1-9. [13] Tom, G., Chen, A., Liao, H. and Shao, J. (2005) Body- image, relationships and time. The Journal of Psychol- ogy, 139(5), 458-468. [14] Pope, H.G., Phillips, K.A. and Olivardia, R. (2000) The adonis complex: The secret crisis of male body obsession. The Free Press, New York. [15] Ridgeway, R.T. and Tylka, T.L. (2005) College men’s perceptions of ideal body composition and shape. Psy- chology of Men & Masculinity, 6(3), 209-220. [16] Furnham, A. and Calnan, A. (1998) Eating disturbance, self-esteem, reasons for exercising and body weight dis- satisfaction in adolescent males. European Eating Dis- orders Review, 6(1), 58-72. [17] Hatoum, I.J. and Belle, D. (2004) Mags and abs: Media consumption and bodily concerns in men. Sex Roles, 51(7/8), 397-407. [18] Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967) The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine, Chicago. |