Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.12A, 1202-1207 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312A178 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1202 Psychological Capital as a Buffer to Student Stress Laura Riolli1*, Victor Savicki2, Joseph Richards3 1College of Business Administration, California State University, Sacramento, USA 2Western Oregon University, Monmouth, USA 3College of Business Administration, California State University, Sacramento, USA Email: *riollil@csus.edu Received September 29th, 2012; revised October 23rd, 2012; accepted November 23rd, 2012 This study examined the influence of psychological capital (PsyCap), on the well-being of university un- dergraduates during an academic semester. PsyCap, a recently developed, higher-order construct, applied to the world of work has been hypothesized to aid employees cope with stressors in the workplace. The current study extends this concept to work in the academic environment. Psychological capital is hy- pothesized to empower students with the necessary metal strength to cope up with adverse circumstances. Among undergraduate students from a university in the Western US, Psychological Capital (PsyCap) me- diated between stress and indices of psychological and physical well-being. In the case of Psychological Symptoms and Health Problems, PsyCap buffered the impact of stress so that the relationship between stress and negative outcomes was reduced. In the case of Satisfaction with Life, PsyCap augmented a positive psychological outcome. We discuss implications for research on resilience to academic stress, the power of the PsyCap construct to effect positive psychological outcomes in a variety of student situations, and implications for educators in developing and promoting positive outcomes based on this valuable personal capital. Keywords: Psychological Capital; Stress; Coping; Positive Outcomes Psychological Capital as a Buffer to Student Stress Academic stressors pose a threat to the psychological and physical well-being to the estimated 19 million college and stu- dents enrolled in college in Fall 2009. College students are particularly prone to stress and there is a clear link between student stress and illness (Houghton et al., 2012). In fact, psy- chological distress among university students was found to be significantly higher than among the general population (Adlaf, Gliksman, Demers, & Newton-Taylor, 2001; Stallman, 2010). College students face a number of stressors ranging from the demands of their academic coursework to challenges in man- aging interpersonal relationships (Houghton et al., 2012). Un- dergraduate students are subject of continuous evaluation such as weekly tests and papers (Wright, 1964). One study suggests that exams and examination results are the most important causes of stress for students (Roddenberry & Renk, 2010). Students are often under high pressure to earn good grades and to obtain a degree (Hirsch & Ellis, 1996). Excessive homework, unclear assignments, and uncomfortable classrooms are other sources of academic stress (Kohn & Frazer, 1986). In addition, relations with faculty members and time pressures may also be sources of academic stress aside academic requirements (Sgan- Cohen & Lowental, 1988). A measure of stress in college stu- dents is the dropout rate. According to US News and World Report (Bowler, 2009), approximately thirty percent of students enrolled in universities drop out after their first year and half never graduate. The college completion rates in the United States have decreased for more than three decades (Bowler, 2009). Clearly academic stressors take a toll on students in a variety of ways. As pointed out by the positive psychology literature, some individuals are unable to curb the psychological impact of stressors and they suffer physical and psychological health symptoms (Youssef & Luthans, 2007). Other individuals have the capacity to rebound and experience little or no change in their capacity to function. According to Tugade & Fredrickson (2004), these latter individuals demonstrate psychological re- siliency; that is, effective adaptation and coping in the face of adversity. Individuals who believe that they can do something about their stress have a more positive psychological adaptation relative to those who do not hold such beliefs (Roddenberry & Renk, 2010). One important research question, then, concerns identifying factors that distinguish those who cope more effec- tively with academic stress. According to previous research, individual differences in resilient aspects of personality, such as dispositional optimism, are favorably associated with psycho- logical adjustment in college students (Brissette, Scheir, & Carver, 2002). However, research has not comprehensively tested the strength of resilient personality on health symptoms, life satisfaction, and psychological symptoms with students. This study examines the relationship between academic stress, health symptoms, life satisfaction, and psychological symptoms and the mediating role of characteristics associated with stress- resisting cognitive strategies in a sample of university students. Individual differences in stress-resilient cognitive strategies are predicted to mitigate the effects of stress on various indices of well-being among college students. The current research addresses the need for research on the experience of academic stress, going beyond previous studies on academic stress such as time management, and leisure satisfaction and other studies about the transitional nature of *Corresponding author.  L. RIOLLI ET AL. freshmen college life (Ross, Niebling, & Heckert, 1999). Study- ing how resilient cognitive factors alleviate students’ reaction to academic stress becomes important to finding ways to reduce academic stress-related problems during their academic careers as well as afterwards (Burris, Brechting, Salsman, & Carlson, 2009). Academic Stress and Psychological Symptoms, Health Symptoms, and Satisfaction with Life A disconcerting trend in college student health is the reported increase in student stress (Sax, 1997; Stallman, 2010). Acade- mic stressors include the student's perception of the extensive knowledge base required and the perception of an inadequate time to develop it (Carveth, Gesse, & Moss, 1996). Each seme- ster students report experiencing academic stress at certain times with the greatest sources of academic stress ensuing from taking and studying for exams, competition, and the large amount of content to master in a small amount of time (Abouserie, 1994). More disconcerting is the finding that stu- dents suffering from psychological distress may consider this condition “normal” and not seek relief (Stallman, 2010). For the purposes of the present study, we adapt from Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, and Boudreau, (2000) the concept of stu- dent challenge stressors which are school-related demands or circumstances that, although potentially stressful, have associ- ated potential gains for individuals. Students exposed to such stressors report adverse physical health outcomes, including poor self-reported health status, a greater number of medical problems and psychological im- pairment (Murphy & Archer, 1996; Stallman, 2010). The lit- erature on stress in adolescent populations is limited by a focus on negative indicators of health (i.e., psychopathology), with less attention paid to important positive indicators of adolescent functioning (e.g., life satisfaction). One model of studying stress includes indicators that measure beyond a negative or neutral point to desirable levels of functioning focusing on adolescent social-emotional development (e.g., subjective well- being) (Roeser, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2000). Using this model, health can be examined in terms of traditional indicators of psychopathology as well as the presence of positive indicators of optimal functioning, such as happiness (i.e., life satisfaction). Such a focus on positive individual traits and experiences is consistent with the intent of the positive psychology movement (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Previous research indi- cates that the more stress students experience, the lower their levels of life satisfaction (Chang, 1998). Adaptive Abilities and Resilient Personalities Academic stressors that may contribute to the development of problems ranging from concentration difficulty, fatigue, and anxiety, to eating disorders, and other illnesses. And yet, whereas many young adults encounter psychological distress which often disrupts the completion of normal developmental and educational tasks, others do not suffer such consequences. What distinguishes young adults who adapt with only limited psychological and physical effects from those who suffer a great deal? One explanation may draw from psychological abilities and traits that facilitate or hamper adjustment to aca- demic stress conditions. Some young adults with more stress-resilient personalities suffer fewer health degradation in response to the same expo- sure. These individuals have “positive” traits and abilities (e.g., optimism, positive emotionality, hardiness, hope, ego resilience) which correlate negatively with physical and psychological health symptoms (Seligman, 1998; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). Psychological capital (PsyCap), is a meta-concept that incorporates various traits that have been found to foster psy- chological resilience. PsyCap is defined as: “an individual’s positive psychological state of development and is characterized by: 1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challeng- ing tasks; 2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; 3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary , redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and 4) when beset by problems and adversity, sus- taining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success.” (Luthans, Youssef, & Avolio, 2007: p. 3). PsyCap is operationalized by combining optimism, hope, ef- ficacy, and ego resilience (Peterson, Walumbwa, Byron, & Myrowitz, 2009). These separate measures have been found to differentiate persons on different criteria of well-being (Block & Kremen, 1996; Scheier & Carver, 1985; Snyder, Irving, & Anderson, 1991). The combination of these capacities have been proposed by Peterson et al. (2009) to comprise a reliable higher-order construct whose composite is a potentially robust predictor of coping and health. Initial research in the Indus- trial-organizational psychology field confirms a positive rela- tionship between PsyCap and well-being (Culbertson, Mills, & Fullagar, 2010) as well as other important work attitudes, be- haviors, and performance (Avey, Reichard, Luthans, & Mhatre, 2011). We predict that students who maintain higher PsyCap will perceive the academic environment as being less distressing and more than likely to see the positive elements that contribute to their overall well-being. For example, despite a very stressful environment, an optimistic, hopeful, efficacious, and ego resil- ient person is likely to believe he or she has sufficient resources to prevent being overwhelmed and experience debilitating dis- tress. We also anticipate that persons scoring high on PsyCap will perceive the environment as maintaining more challenging aspects, with the potential for benefits such as enjoyment, learning, and personal growth. Research suggests that people can be particularly adaptive to demands they find challenging (Lepine, Podsakoff, & Lepine, 2005). More optimistic person- alities tend to see the positive aspects associated with new de- mands. Likewise, hope is associated with the salience of per- sonal goals (hope-path) and with confidence that goal accom- plishment will enable one to improve one’s life (hope-agency). Together, these factors suggest that persons high in PsyCap will more readily withstand stress and maintain physical and psy- chological well-being and happiness in the face of academic stress. These types of resilient adaptive personality and cogni- tive differences have been proposed to mediate the effects of stress on well-being for college students. Thus, if PsyCap actu- ally enhances adaptation to stressors, we should expect to find that among students who are exposed to the same stressful cir- cumstances, those with higher PsyCap will have better health and well-being. This suggests the following hypotheses: Hypotheses The general hypothesis is that psychological capital will Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1203  L. RIOLLI ET AL. mitigate the effects of stress on various indices of psychological well-being. Specifically, we hypothesize the following: Hypothesis 1: Student stress will be significantly related to reports of psychological symptoms (i.e., anxiety, somatic com- plaints, and depression), satisfaction with life, and health pro- blems. H1A: Student Stress will be positively related to psy- chological symptoms H1B: Student Stress will be negatively related to satisfaction with life H1C: Student Stress will be positively related to health problems Hypothesis 2: Psychological Capital will be significantly re- lated to reports of psychological symptoms (i.e., anxiety, so- matic complaints, and depression), satisfaction with life, and health problems. H2A: PsyCap will be negatively related to psychological symptoms H2B: PsyCap will be positively related to satisfaction with life H2C: PsyCap will be negatively related to health problems Hypothesis 3: PsyCap will mediate the effects of student stress on psychological symptoms, life satisfaction, and health problems. Methods Participants Participants were 141 organizational behavior, business stu- dents from a university in the Western US Average age was 23.64 years with a range from 19 to 44 years. Males were 54% and females 46%. The classes were populated mostly by Jun- iors (40.4%), Seniors (30.5%) and fifth year students (23.4%). On average they maintained 15.24 hours per week in outside jobs while in school, and had an average of 5.67 years of pre- vious work history. Measures Student Stress. Student challenge stressors, as defined by Ca- vanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, and Boudreau, (2000) are school- related demands or circumstances that, although potentially stressful, have associated potential gains for individuals; e.g. “Time pressures I experience in school,” and “The number of projects and or assignments I have in school.” This six item scale used a 5 point Likert scale from 1 = Produces no stress, to 5 = Produces a great deal of stress. Alpha for the current sample was .742. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). The SWLS is a five item questionnaire using a seven point Likert scale to rate overall satisfaction with life using questions such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The SWLS can be viewed as a measure of psychological adjustment since the scale demonstrated moderately strong criterion validity with several measures of psychological well- being (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985 pp. 72-73). Alpha for the current sample was .890. Psychological symptoms. Psychological well-being/strain was measured based on the average of four sub-scales from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). The five to six item symptom cluster scales included were Somatization: distress arising from perceptions of bodily dysfunction; Depression: dysphoria and lack of motivation and energy; Anxiety: nervousness, panic attacks, apprehension, dread; and Hostility: thoughts, feelings or actions of anger. Coefficient alphas for the sub-scales were Somatization .845, Depression .852, Anxiety .827, Hostility .802. Health Problems. The physical health questions (25) of the Lifestyle Questionnaire (Engs & Aldo-Benson, 1985) were summed. Students indicated how frequently they suffered the specific health problems over the month previous; e.g. “heada- che,” “cough,” “stomach upset.” The test-retest reliability coef- ficient for this instrument was reported by the authors as .89. Psychological Capital (PsyCap), Psychological capital is conceptualized as a combination of efficacy, optimism, resil- ience, and hope (Luthans, Youssef, & Avolio, 2007). The mea- sure used in this study is the sum of normalized scores from several well-known instruments. Efficacy was drawn from the Professional Efficacy scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Student Survey, MBI-SS) The MBI-SS was constructed by Schaufeli, Martinez, Marques-Pinto, Salanova, and Bakker (2002). It measures students’ feelings while they study. The 6 item Professional Efficacy scale was responded to on 7-point Likert scale is used, from 0 (never) to 6 (always). The alpha for this sample was .778. Dispositional optimism was measured using the 4 item optimism sub-scale of the Life Orientation Test (LOT) (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Alpha for the current sample was .755. Psychological resilience was measured using the Ego-Resiliency Scale (Block & Kremen, 1996) which as- sesses the capacity to respond effectively to changing situ- ational demands, especially frustrating or stressful encounters. This scale consists of 14 items, each responded to on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (applies very strongly) For the current sample, the alpha reliability was .748. Hope was measured using two components of hope developed by Snyder and his colleagues (Snyder, Cheavens, & Sympson, 1997): Hope Agency (four items), the degree to which individuals felt that they might be able to act to achieve a positive outcome, and Hope Path (four items), the degree to which an individual could see a way or path toward a positive outcome. All hope items were rated using an eight point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Definitely false, to 8 = Definitely true. Alphas for the current sample were Hope Agency = .829, Hope Path = .806. Procedures Participants responded to the measures at two different times. First, after mid-term exams, but prior to the deadlines for class papers and final exams. At this time they responded to the PsyCap measures, and reported various demographic informa- tion. The second time point was directly upon completing the class final exam. At this point they responded to the BSI, SWLS, Health Problems, and the Student Stress questions. All responses were kept confidential. Students received extra credit in their classes for their participation. Results Confirmatory Factor An alysis We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to verify the higher-order factor of PsyCap. In this model, the first order indicator variables were the scale items. The secondary-factor model showed good model fit, χ2 = 481.21, df = 197, p < .01; Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1204  L. RIOLLI ET AL. NFI = .96; GFI = .95; CFI = 97; RMSEA = .05. The standard- ized factor loadings for the higher-order factor of trait PsyCap are .63 (optimism), .78 (hope), .87 (efficacy), and .80 (ego re- silience), and the standardized factor loadings for the four first-order factors ranged from .47 to .75. Based on this support for the higher-order PsyCap model, the aggregated means of the four facets were used to index PsyCap in the subsequent analy- ses. Stress, PsyCap, and Psychological and Health Symptoms and Satisfact io n with Life Table 1 illustrates the relation of research variables to each other. An examination of Table 1 shows that hypothesis 1 is supported since Student Stress was significantly positively correlated with psychological symptoms and health problems, and inversely correlated with satisfaction with life. Hypothesis 2 was supported since PsyCap was significantly inversely cor- related with psychological symptoms and health problems, and positively correlated with satisfaction with life. Both student stress and psychological capital operate in the predicted manner. A mediation analysis, following Barron and Kenney (1986) tested impact of individual accumulation of the personal re- sources associated with Psychological Capital. Mediation Analyses Mediation analysis is a two step process commonly under- taken using hierarchical multiple regression. The question an- swered is whether or not a mediating variable, in this case Psy- Cap, accounts for some or all of the variance that relates two other variables. In the current study the independent variable was Student Stress, and the dependent variables were Psycho- logical Symptoms, Satisfaction with Life, and Health Problems. Table 2 shows the results of the mediation analyses. The key to accepting the mediating action of a third variable (PsyCap) is whether or not it is significantly related to both the IV and DV, and if, when added in step 2 of the hierarchical regression, the beta for the IV is reduced because some part of its relationship is accounted for by the mediating variable. As Table 2 reveals, Psychological Capital is a sufficiently strong mediator that it deprives Student Stress of its statistical significance in step 2 of the hierarchical regressions with both Satisfaction with Life, and with Health Problems. With Psychological Symptoms, PsyCap adds to the significance of the regression, but only partially mediates the relationship between Student Stress and Psychological Symptoms. In all three cases, Psychological Capital demonstrates that it mediates between stress and psy- chological or physical well-being. In the case of Psychological Symptoms and Health Problems, PsyCap buffers the impact of stress so that the relationship between stress and negative out- comes is reduced. In the case of Satisfaction with Life, PsyCap augments a positive psychological outcome. In relation to a variety of measures of student well-being, psychological capital shows its mediating power. Additional Results Psychological Capital was not related to any demographic characteristics of the sample; e.g. age, years of work, gender. Yet one interesting finding suggested by Avey, Luthans, Smith, and Palmer (2010) was supported. In a separate analysis of the current sample, PsyCap was significantly related to stress ap- Table 1. Means, SDs, and correlations for major variables. MeanSD 1 2 3 4 Student Stress 3.470.77 Satisfaction with Life 5.05 1.20 –.27** sychological Symptoms 3.29 2.89.31** –.37** ealth Problems 21.9 25.24.21* –.04 .44** sychological Capital 0.00 0.71 –.28** .49** –.29** –.22** Note: *p < .05, **p < .01. Table 2. Mediation analyses for psychological capital with student stress and three well-being measures. Mediation Analyses B SE B Psychologic al Symptoms Step 1 Student Stress 1.156 .293 .318*** Step 2 Student Stress .930 .299 .256** Psychological Capital –.918 .343 –.219** Satisfaction with Life Step 1 Student Stress –.409 .123 –.276*** Step 2 Student Stress –.212 .115 –.143 Psychological Capital .771 .131 .456*** Health Problems Step 1 Student Stress 6.428 2.514 .212** Step 2 Student Stress 4.886 2.589 .161 Psychological Capital –6.285 2.976 –.180* Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. praisals as operationalized by Ferguson, Matthews, and Cox (1999). Psychological Capital showed significant positive cor- relations with the appraisal of Challenge (r = .367, p < .01), and negative correlations with Threat (r = –.240, p < .01), and Loss (r = –.315, p < .01). This finding supports theorizing that higher levels of PsyCap may allow individuals to view events more positively, less negatively, and thus engage in more productive coping styles. This presumed connection must be tested further. Discussion The academic work environment for students contains many of the same difficulties evident in an organizational or business environment. Stressors may manifest in different stripes, but the impact of those stressors on student well-being can have a variety of negative psychological, health, and behavioral effects that may reduce student effectiveness, cause high levels of dis- tress, and in the long run deprive the economy and the nation of valuable, educated contributors. The study of psychological capital, as a potential antidote to the effects of stress, suggests that this higher-order concept may offer an avenue to boost Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1205  L. RIOLLI ET AL. student immunity to stressors, or even to shape the way in which they appraise and define events to reframe them as moti- vational challenges rather than debilitating threats. Each indi- vidual construct of optimism, hope, efficacy, and ego resiliency is imperfect in representing general resilience to stress, and thus their common factor should provide a more complete index of the domain. The current study ported the concept of psycho- logical capital into the student, academic work context. Reports of psychological capital measured well prior to an acute stress situation (final exams and term’s end) correlated as hypothesized to three measures of student well-being (psycho- logical symptoms, health symptoms, and satisfaction with life). In addition, psychological capital buffered stressors with the negative stress outcomes, and augmented the positive outcome. One suggested mechanism for these mediating effects is that psychological capital may be related to more positive and less negative cognitive appraisals of stress. Implications for university educators include a focus on as- pects of psychological capital within the academic curriculum. Psychological capital may be as, or even more, valuable as a resource for students than is traditional academic content, since PsyCap helps students persevere in their studies in a psycho- logically and physically healthier manner. The notion that Psy- Cap can influence the adaptation of students to face stressful events such as exams and tests, is itself a valuable piece of information that could be used for designing customized eva- luation tools that will adapt to each student’s particular circum- stances. Training students to develop more optimistic explanatory styles, lower levels of distressed thinking, and more construc- tive envisioning of the future, that persons scoring high on trait PsyCap engage in naturally, may help less psychologically resilient students. Seligman in his book “learned optimism” talks about developing more optimistic appraisals and to use other strategies that foster resilience (Seligman, 1998). Thus, such training programs might be successful in terms of im- proving students long-term health outcomes and it would sug- gest to universities the benefits of promoting a more “positive” psychological outlook as part of general training that can be administered in the classroom, emphasizing elements of Psy- Cap such as developing an optimistic explanatory style and avoiding distressed thinking. Fortuitously, Luthans, et al., (2006) have demonstrated that PsyCap can be developed in short training classroom interventions, as well as in an online format (Luthans, Avey, & Patera, 2008). One limitation of this study concerns the potential gener- alizability of the findings. The extent to which the current re- sults extend to other organizational settings beyond academia remains to be seen. The academic context of this study is very focused. Our sample was drawn from a single campus; future research should validate our findings with a more diverse sample. As with studies without a true experimental design, it is not possible to assume causality. There is a need to examine how young adults who experience academic stress over a prolonged period of time either adapt to it or fail to cope with it effectively. The current study suggests that the construct of psychological capital may serve a substan- tial role in differentiating those who prove to be more or less adaptive to stressful environments. Luthans, Avolio et al. (2007), suggest that strategies can be developed to better shape these dispositions among young adults and facilitate their cop- ing with stress exposures. REFERENCES Abouserie, R. (1994). Sources and levels of stress in relation to locus of control and self-esteem in university students. Educational Psycho- logy, 14, 323-330. doi:10.1080/0144341940140306 Adlaf, E. M., Gliksman, L., Demers, A., & Newton-Taylor, B. (2001). The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian undergraduates: Findings from the 1998 Canadian campus survey. Journal of American College Health, 50, 67-72. doi:10.1080/07448480109596009 Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., Smith, R. M., & Palmer, N. F. (2010). Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health P sy ch ol og y, 15, 17-28. doi:10.1037/a0016998 Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on em- ployee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource De- velopment Quarterly, 22, 127-152. doi:10.1002/hrdq.20070 Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 1173-1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996). IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 349-361. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349 Bowler, M (2009). Dropouts loom large for schools. US News and World Report. URL (last checked 29 May 2010). http://www.usnews.com/articles/education/best-colleges/2009/08/19/ dropouts-loom-large-for-schools.html Burris, J. L., Brechting, E. H., Salsman, J., & Carlson, C. R. (2009). Factors associated with the psychological well-being and distress of university students. Journal of American College Health, 57, 536-543. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.5.536-544 Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of opti- mism in social network development, coping, and psychological ad- justment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 102-115. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102 Carveth, J. A., Gesse, T., & Moss, N. (1996). Survival strategies for nurse-midwifery students. Journal of Nurse-Midw i f e r y , 41, 50-54. doi:10.1016/0091-2182(95)00072-0 Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 65-74. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65 Chang, E. C. (1998). Does dispositional optimism moderate the relation between perceived stress and psychological well being? A prelimi- nary investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 233- 240. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00028-2 Culbertson, S. S., Mills, M. J., & Fullagar, C. J. (2010). Feeling good and doing great: The relatinship between psychological capital and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 421-433. doi:10.1037/a0020720 Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The brief symptom invent- tory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595-605. doi:10.1017/S0033291700048017 Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 Engs, R. C., & Aldo-Benson, M. (1995). The association of alcohol consumption with self-reported illness in university students. Psy- chological Reports, 76, 727-736. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.76.3.727 Ferguson, E. Matthews, G., & Cox, T. (1999). The appraisal of life events (ALE) scale: Reliability and validity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 97-116. doi:10.1348/135910799168506 Hirsch, J. K., & Ellis, J. B. (1996). Differences in life stress and reasons for living among college suicide ideators and non-ideators. College Student Journal, 30, 377-384. Houghton, J. D., Wu, J. P., Jeffrey, L. G., Christopher, P. N., & Charles, C. M. (2012). Effective stress management. Journal of Management Education, 36, 220-238. doi:10.1177/1052562911430205 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1206  L. RIOLLI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1207 Kohn, J. P., & Frazer, G. H. (1986). An academic stress scale: Identifi- cation and rated importance of academic stressors. Psychological Reports, 59, 415-426. doi:10.2466/pr0.1986.59.2.415 Lepine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lepine, M. A. (2005). A meta-ana- lytic test of the challenge stressor-hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and per- formance. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 764-775. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803921 Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., & Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-inter- vention. Journal of Or gan iza tio nal Behavior, 27, 387-393. doi:10.1002/job.373 Luthans, F., Avey, J.B., & Patera, J. L. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psycho- logical capital. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 7, 209-221. doi:10.5465/AMLE.2008.32712618 Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Posi- tive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with per- formance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541-572. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Murphy, M. C., & Archer, J. (1996). Stressors on the college campus: A comparison of 1985-1993. Journal of College Student Develop- ment, 37, 20-28. Peterson, S. J., Walumbwa, F. O., Byron, K., & Myrowitz, J. (2009). CEO positive psychological traits, transformational leadership, and firm performance in high technology start-up and established firms. Journal of Management, 35, 348-368. doi:10.1177/0149206307312512 Roddenberry, A., & Kimberly, R. (2010). Locus of control and self- efficacy: Potential mediators of stress, illness, and utilization of health services in college students. Child Psychiatry & Human De- velopment, 41, 353-370. doi:10.1007/s10578-010-0173-6 Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (2000). School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional deve- lopment: A summary of research findings. The Elementary School Journal, 100, 443-471. doi:10.1086/499650 Ross, S. E., Niebling, B. C., & Heckett, T. M. (1999). Sources of stress among college students. Col leg e St udent Journal, 33, 316-318. Sax, L. J. (1997). Health trends among college freshmen. Journal of American College Health, 45, 252-262. doi:10.1080/07448481.1997.9936895 Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Marques-Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33, 464-481. doi:10.1177/0022022102033005003 Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985) Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219-247. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219 Seligman, M. E. P. (1998). Learned optimism. New York: Pocket Books. Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psycho- logy: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 Sgan-Cohen, H. D., & Lowental, U. (1988). Sources of stress among Israeli dental students. The Journal of the American College Health Association, 36, 317-321. doi:10.1080/07448481.1988.9939027 Snyder, C. R., Cheavens, J., & Sympson, S. C. (1997). Hope: An indi- vidual motive for social competence. Group Dynamics Theory, Re- search, and Practice, 1, 107-118. doi:10.1037/1089-2699.1.2.107 Snyder, C. R., Irving, L., & Anderson, J. R. (1991). Hope and health: Measuring the will and the ways. In C. R. Snyder, & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health per- spective (pp. 285-305). Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press. Stallman, H. M. (2010). Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist, 45, 249-257. doi:10.1080/00050067.2010.482109 Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional exper- iences. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 86, 320-333. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320 Youssef, C., & Luthans, F. (2007). Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Jour- nal of Management, 33, 774-800. doi:10.1177/0149206307305562 Wright, J. J. (1964). Environmental stress evaluation in a student com- munity. The Journal of the American College Health Association, 12, 325-336.

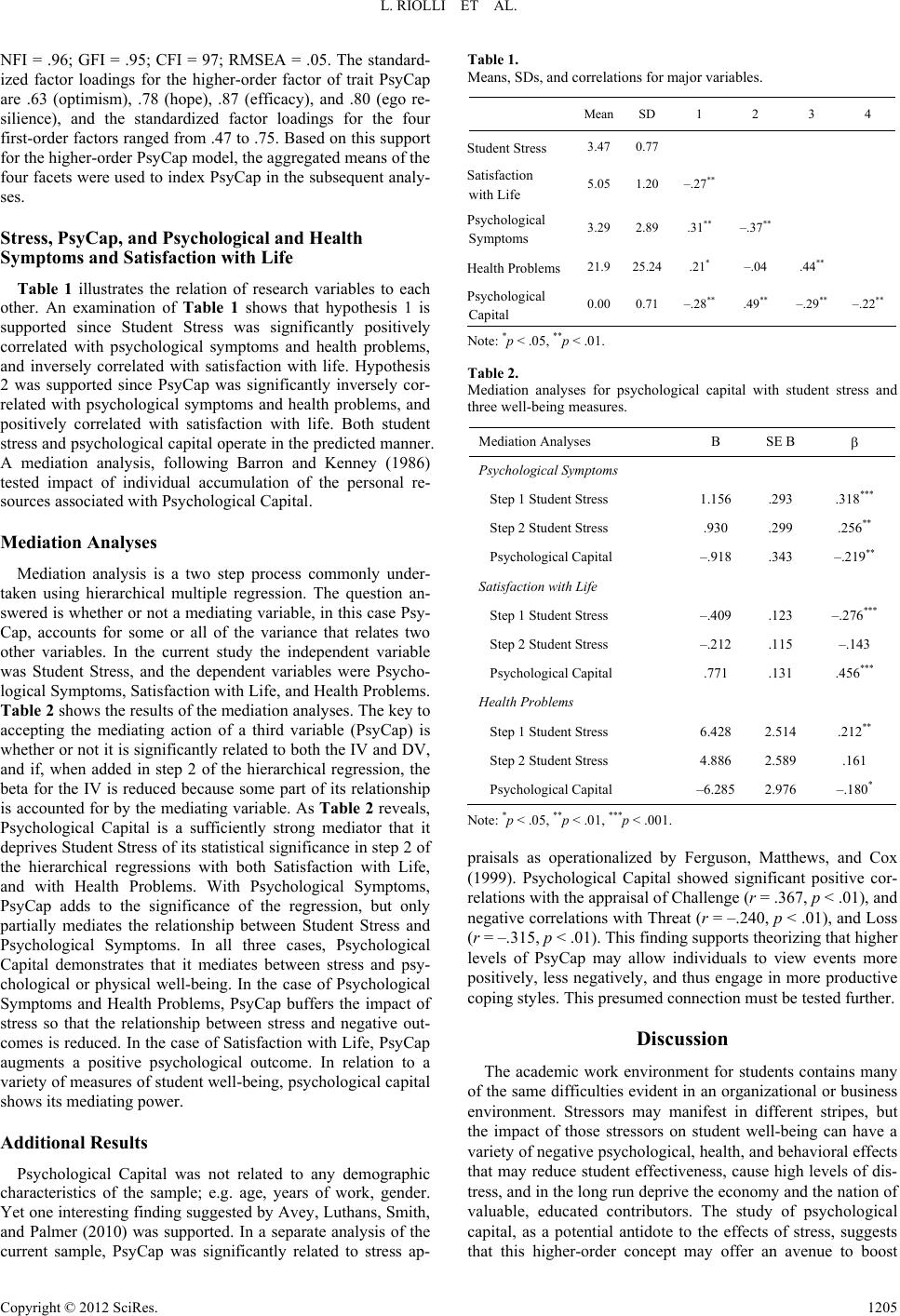

|