Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

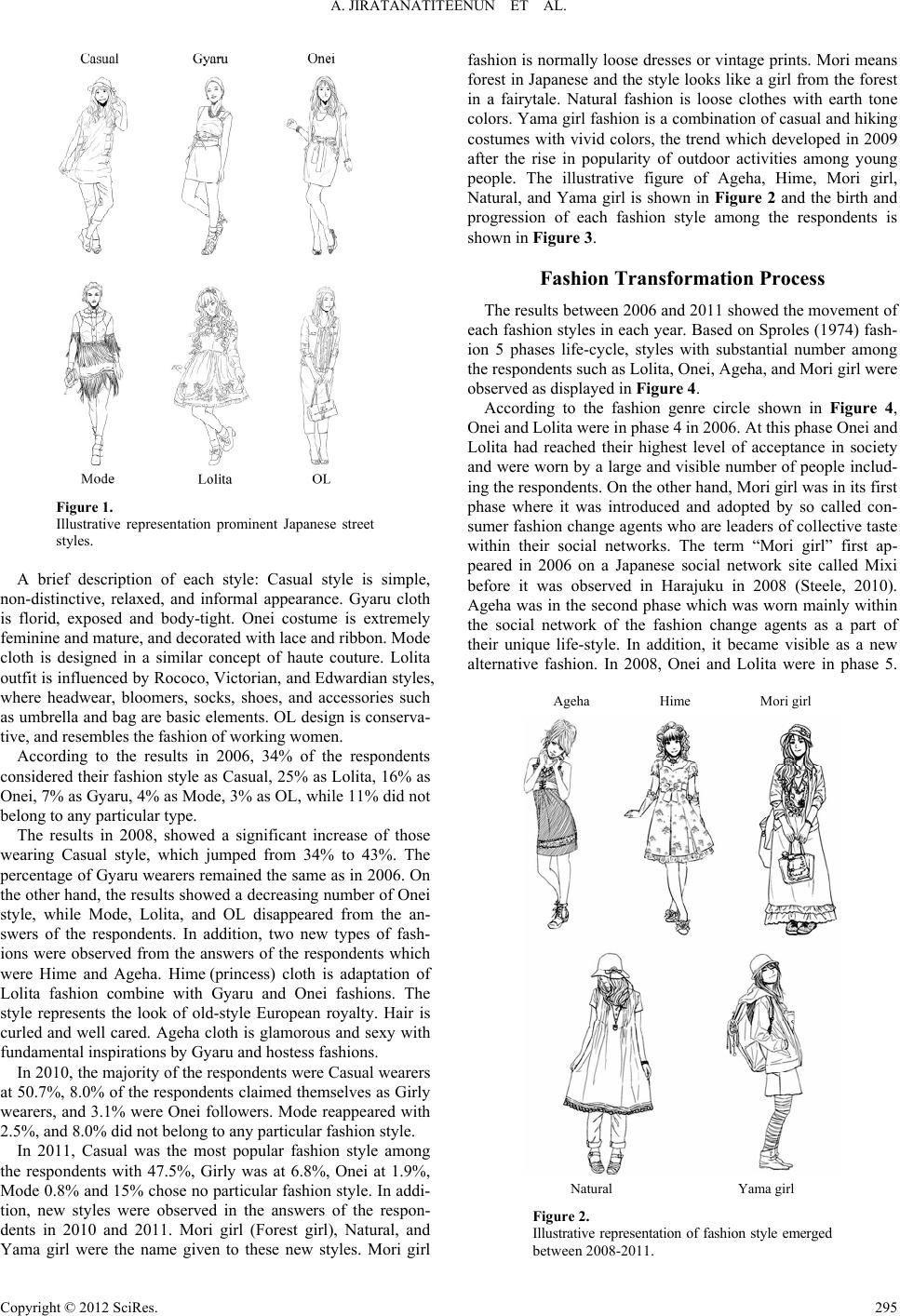

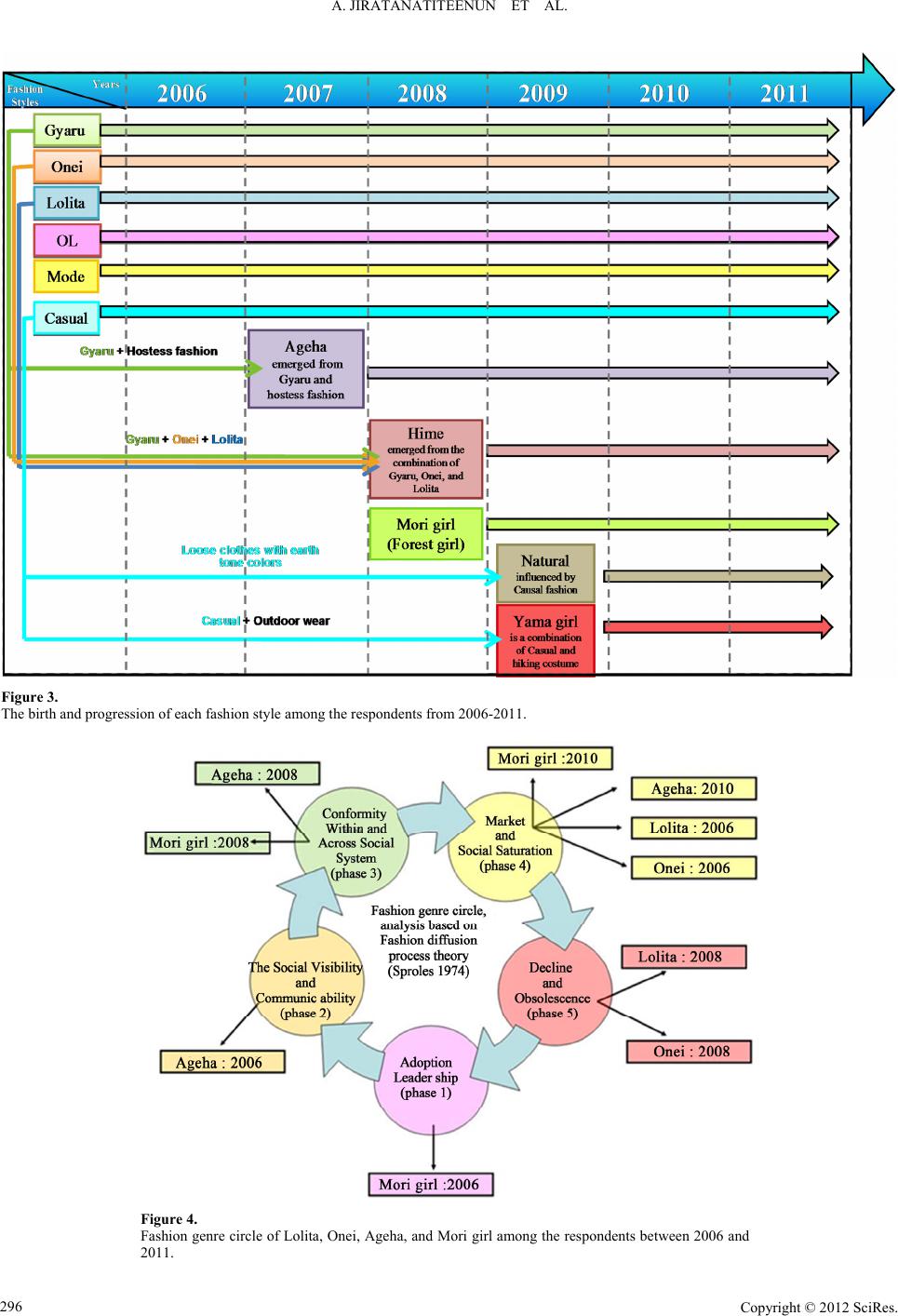

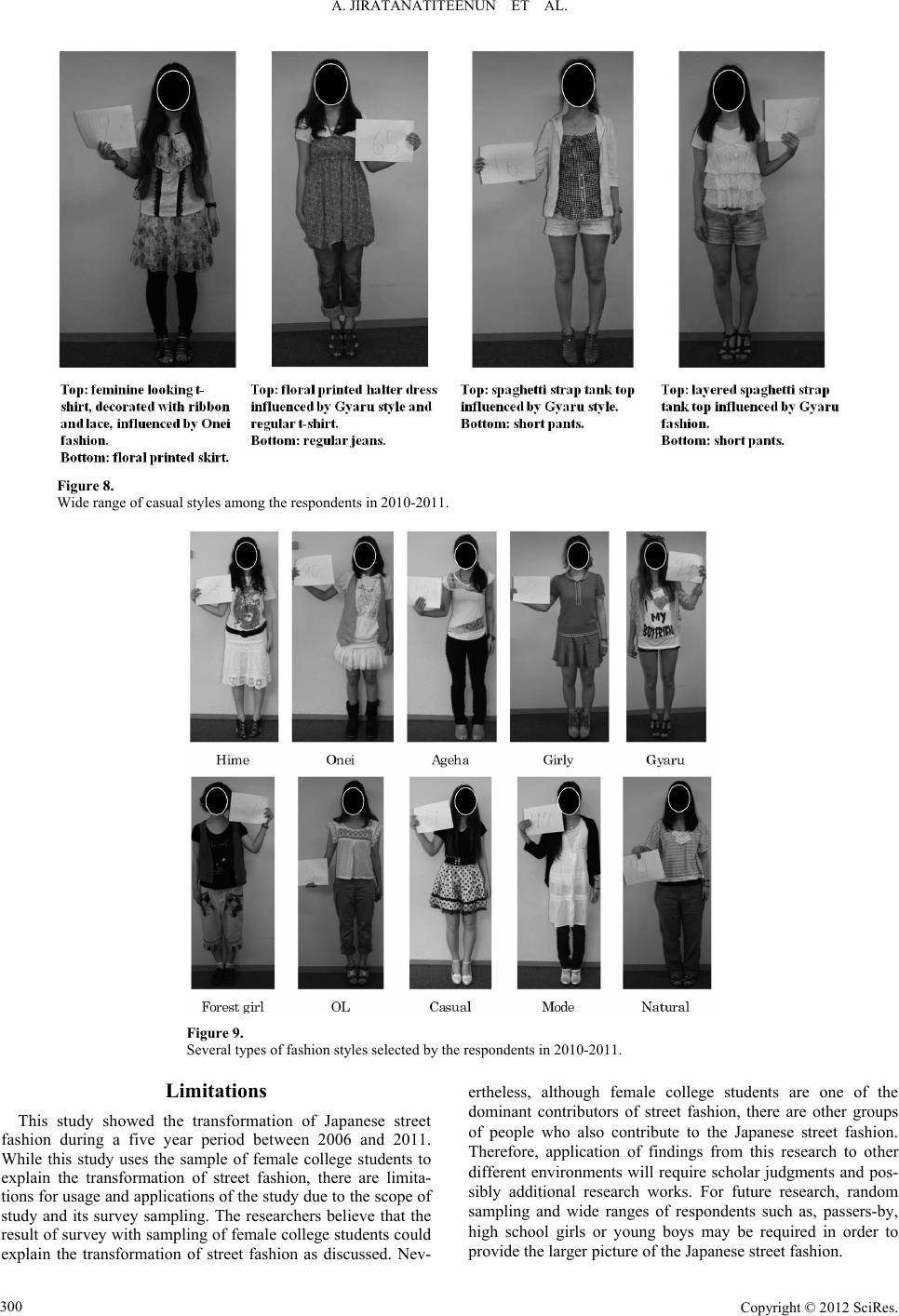

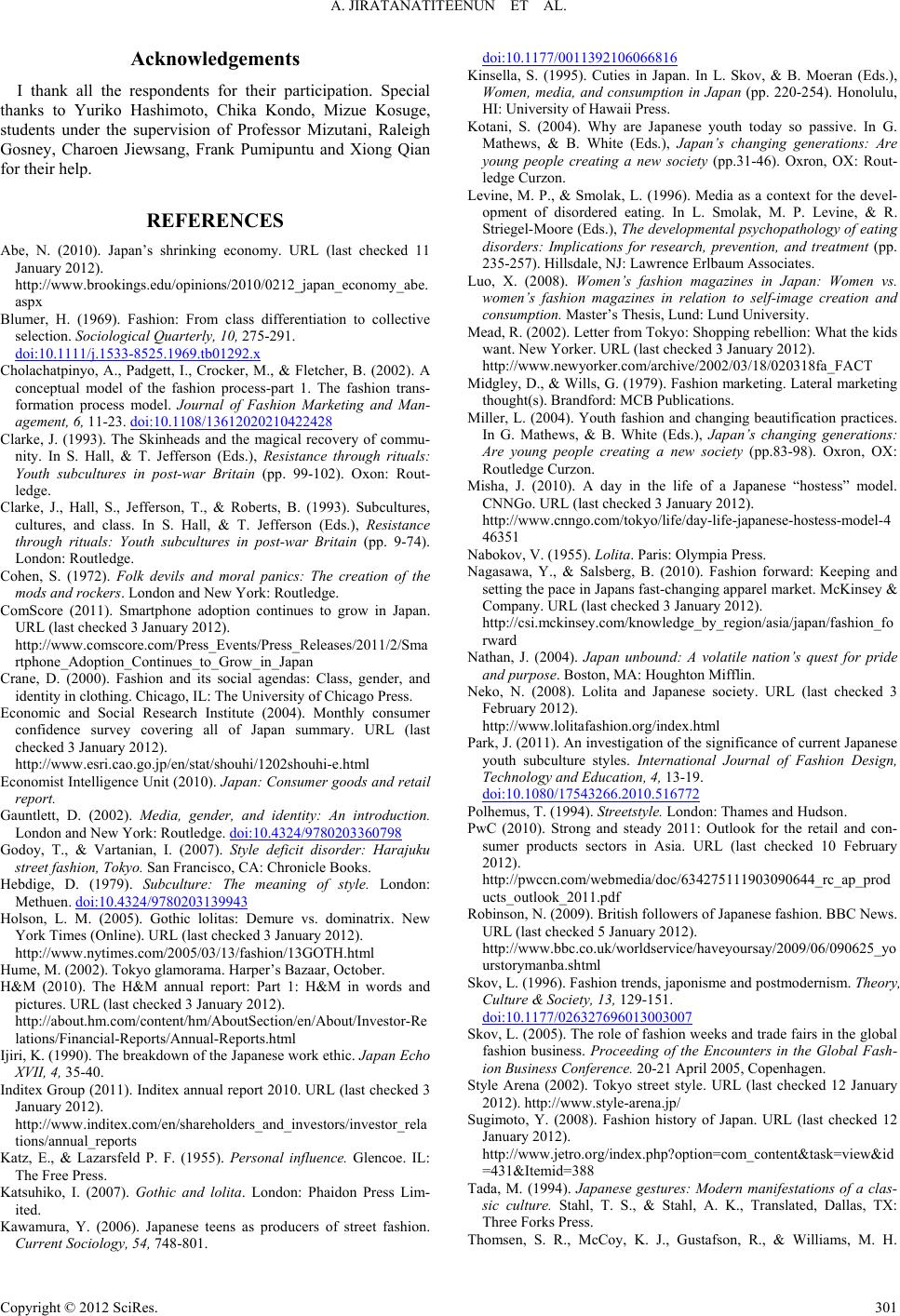

Advances in Applied Sociology 2012. Vol.2, No.4, 292-302 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.24038 Copyright © 2012 SciRes . 292 The Transformation of Japanese Street Fashion between 2006 and 2011 Aliyaapon Jiratanatiteenun1, Chiyomi Mizutani2, Saori Kitaguchi3, Tetsuya Sato3, Kanji Kajiwara 4 1Department of Engineering Design, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan 2Department of Textile and Clothing, Otsuma Women’s University, Tokyo, Japan 3The Center for Fiber and Textile Science, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan 4Fibre Innovation I ncubator, Shinshu Un i v ersity, Nagano, Japan Email: cindy_emailbox@ yahoo.com Received August 13th, 2012; revised September 15th, 2012; accepted September 29th, 2012 The emergence of Japanese street fashion in the 1990s in young girls has created a notion of generation identity and new fashion styles. Although Japanese street fashion was studied by scholars from multi- ple-disciplines, little research has been carried-out on its evolution overtime. This paper aims to examine its transition over a five year period from 2006 to 2011, and to explain the factors that led to these changes. In order to follow the transition of street fashion, survey questionnaires were distributed to a to- tal of 1094 female college students in Tokyo between 2006 and 2011. Further, fashion magazines were studied and surveyed to understand their evolution and the influence on their readers. The findings showed that economic recession in 2007, the fast fashion business, and the fashion models played a sig- nificant role in shifting the popularity of each style, and Casual style became the most popular style throughout the years of the study. In addition, fashion styles have merged and became difficult to differ- entiate by their appearances. Many fashion magazines also added Casual style to their publication. Finally, this paper suggests that teens created their own styles by combining several fashion elements, and as a result new styles such as Ageha and Mori girl were observed in the fashion scenario. Keywords: Street Fashion; Transformation; Japan; Fashion Styles; Youth Culture; Casual fashion Introduction Street fashion referred to fashion styles that were created by general public instead of professional fashion designers or fashion studios. These people have mixed their own styles by using several fashion elements in order to identify themselves from the mainstream. The street fashions could come from any person regardless of class statuses. However, it is notable that in Japan, street fashions are female dominant and it is the girls who control fashion trends. Over the past decade the term “street fashion” has commonly been used around the world as a representation of youth fashion. It is widely accepted that street fashion sprung from youth sub- culture rather than from fashion professionals. In effect, fashion was used as a tool for group identity in order to distinguish the group from the culture at large, and from other groups (Clarke et al., 1993; Polhemus, 1994). Conversely to the classic trickle- down theory (Simmel, 1904; Veblen, 1912), subculture styles became a source of fashion that extended from the street to the designer. In fact, scholars saw subculture styles as fashion in- novation that generated a new process of fashion diffusion. This fashion diffusion is known as trickle up theory or subcultural leadership theory (Midgley & Wills, 1979; Sproles, 1981; Pol- hemus, 1994). In Japan, the street fashion phenomenon was triggered by the economic recession in the 1980s. According to Kawamura (2006), “after the tremendous economic prosperity of the 1980s, followed by Japan’s economic bubble burst, and the country experienced its worst and longest economic recession”. It has been argued that Japanese conformist society may have cracked under the strain of economic stagnation (Nathan, 2004). As a result of this so called societal crack, the Japanese value system such as selfless devotion, respect for seniors and perseverance had changed, especially among teens (Ijiri, 1990). Teens saw the assertion of individual identity as important and meaningful (Kawamura, 2006) and exhibited this through revolutionizing fashion. Under these social and economic conditions, Japanese street fashion became increasingly creative and innovative, as if the teens wanted to challenge and redefine the existing notion of what is fashionable and aesthetic (Kawamura, 2006). This trend was foreseeable since youngsters often construct their personal identities through the consumption of cultural goods such as fashionable clothing, and lifestyles (Crane, 2000). Street fashion started appearing in fashion media and turned to be the focus of fashion media in Japan with magazines such as FRUiTS devoted to this genre (Miller, 2004; Godoy & Varianian, 2007). The street fashion trend continued to spread widely across Japan where rapid adoption by youth has led to the occurrence of fashion identities in each district of Tokyo. Street styles in Japan were categorized according to the shop- ping districts in Tokyo, represented by the name of the district, for example Ginza, Omotesando, and Harajuku fashion. Each area exhibited a different kind of fashion and lifestyle identity. For international contribution, in addition to their luxurious fashion, Japanese street fashion also caught worldwide attention and inspired global trend (Godoy & Varianian, 2007). Many of the Japanese designers such as Kenzo Takada, Hiroshi Fujiwara  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. and Keita Maruyama took part in Paris fashion collections (Su- gimoto, 2008; Godoy & Varianian, 2007; Skov, 1996, 2005). Japanese street fashion, especially its cause of emergence and characteristics, was very appealing to researchers, and was studied by scholars from multiple-disciplines. Miller (2004) saw the emergence of Japanese street fashion as a notion of generational identity, Kawamura (2006) studied on the role of Japanese teens as the producers of street fashion. Godoy and Varianian (2007) provided an insight and subject comprehen- sion of street styles on Harajuku. Park (2011) studied the changes of Japanese street fashion by compared to their mother cultures. However, the research on its movement was slightly untouched. This research is aimed to trace the chronological change of street fashion in Japan and to show the influential factors which transformed the fashion styles between 2006 and 2011. Methodology and Theoretical Framework In order to understand the transition of Japanese street fash- ion, a survey of female undergraduate students aged between 18 - 23 was conducted by questionnaire at a private women’s uni- versity in Tokyo. The group of female undergraduate students was selected as target of the survey due to the fact that Japanese street fashion was female predominant phenomenon. Further- more, this study considers under the assumption that under- graduate students are groups of young Japanese females who are mostly in the stage of developing and creating their own personal fashion styles and lifestyles. At these ages, many of them were responsible for personal allowances and managed their own allowances. These allowances were spent enthusias- tically for fashion and cosmetic items. In addition, the respon- dents were selected from one of the traditional women’s uni- versities which was established around 100 years ago. The stu- dents here have high fashion consciousness and they came from all over Japan. This study was initially conducted in 2006 and repeated in 2008, 2010 and 2011. The numbers of the respondents from each year were as follows; 2006 = 260 people, 2008 = 285 peo- ple, 2010 = 284 people, and 2011 = 265 people. The questionnaire was separated into two sections. The first section consisted of 82 questions asking the respondents about their lifestyles, fashion influences, and buying behaviors by using a five-point scale “Not at all” = 1, “Very” = 5. The sec- ond section asked the respondents to indicate their personal fashion interests, their fashion styles, and their favorite fashion magazines. The purpose of the second section was to investi- gate the popular fashion styles and magazines among the re- spondents. In addition, all respondents were photographed in order to observe their appearances, and to make a comparison with the fashion magazines they chose as their favorite. This paper further examined fashion magazines, analyzing their fashion trends in Japan in 2010 and 2011. The survey result was then concluded and analyzed using the following theories. As to paint a clearer picture on what actually went on in transformation of street fashion during the survey period, Sproles’ (1974) 5 phases of fashion diffusion (Adoption lead- ership, Social visibility and communicability, Conformity within and across social system, Market and social saturation, and Decline and obsolescence) were adopted as the discussion platform. For the cause of transformation, this research analyzed the transformation of fashion trends in Japan through the society (macro) and individual (micro) level perspective employing model proposed by Cholachatpinyo et al. in 2002. The model suggested that fashion transformation could be observed in terms of macro-micro continuum divided into 4 levels namely: 1) macro-subjective level (values on a societal level); 2) macro-objective level (social object); 3) micro-objective level (individual object); and 4) micro-subjective level (individual decision making). Further, the idea surrounding Blumer’s (1969) collective se- lection theory noting that “fashion trends are screened and ma- nipulated into fashion objects, simultaneously, innovative con- sumers may experiment with many possible alternatives, but the ultimate test in the fashion process is the competition be- tween alternative styles for positions of fashionability” was used to understand the apparel industry’s focus on casual styles. Research of Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955), which summarized that regardless of class status, any individual can be the real leadership of fashion due to mass production and mass com- munication in the market, was used to help explain the rapid growth of the fast fashion retail. In order to understand the transformation of Japanese street fashion during the five year period, this research saw impor- tance in discussing background information of Japanese street fashion such as the emergence of Japanese street fashion, the characteristics of Japanese street fashion, and the role of fash- ion magazines, and therefore provided them in the next three sections. The Emergence of Japanese Street Fashion Japanese street fashion became more recognizable in the mid-1990s because of young teenage girls known as Kogal (abbreviated from kokosei gyaru, high school girls), who cen- tered their life around the Shibuya train station. Being a Kogal was a way of expressing a trendy lifestyle or identity that was extraordinarily fashionable. Although this subculture bubbled up from the street to become mainstream like other well-known subcultures in the west such as mods (Cohen, 1972), punks (Hebdige, 1979), rockers (Cohen, 1972), and skinheads (Clarke, 1993), there were two major differences. First, unlike punks, mods, rockers, and skinheads, Kogal was not associated with any violence or moral panic. Secondly, and most importantly, Kogal has been predominantly a female phenomenon, whereas post-war subculture in Europe was predominantly a male phe- nomenon and girls played only a marginal role. As Miller (2004) pointed out youth are enthusiastic in form- ing new fashion by combining aspects of different cultures or historical eras. This has been characterized by process scholars as creolization or hybridity. The Kogal style was similar to school uniforms with short plaid skirts, knee-high white socks, heavy make-up and artificial suntans (Kawamura, 2006). Kogal girls in effect shifted the perspective of their parent culture and established a new youth subculture, where they created a new generation identity to set themselves apart from their elders. Until the mid-1960s, fashion among Japanese women was re- gardless of age or class and beauty ideology was shared be- tween mother and daughter, for example they read the same fashion magazines (Miller, 2004). Miller asserted that the ap- pearance of Kogal not only irritated the older generation, but surprised foreign observers and media pundits, and it surfaced Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 293  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. in Harper’s Bazaar (Hume, 2002) and the New Yorker maga- zine (Mead, 2002) as objects of fascination. The Kogal style was known internationally as one of the Japanese subcultures and gained several followers from around the world especially in Europe (Robinson, 2009). From Kogal, the style spread and escalated to a more ex- treme look with long bleached-blond or dyed brown hair and saddle-brown tans with heavy make-up, brightly colored mini- skirts or short pants and high platform boots known as Ganguro (literally means “black face”). Ganguro led to Amazoness, which was more extreme than ganguro, but it did not last long. In the late 1990s, Yamamba (mountain ogresses) another fash- ion and youth subculture emerged to replace ganguro and ama- zoness. Yamamba developed into Mamba which was the last serial fashion of the Kogal subculture. Although these styles had their distinctive names, the styles were similar and could be differentiated by make-up sty les (Kawamura, 200 6 ). The Characteristics of Japanese Street Fashions At present, Japanese street fashion can be categorized ac- cording to the shopping streets in Tokyo. Ginza, Harajuku, Omotesando, Shibuya, and Daikanyama are the five main shopping districts with street style in Tokyo (Style arena, 2002). The styles vary due to living expenses and lifestyles. However, the most popular street fashion areas among teenagers are Ha- rajuku and Shibuya, where the latest trends with affordable prices are avail able. Harajuku is known as a unique fashion spot that is always crowded with teenagers on weekends. It was here in the late 1980s where the street style began by amateur musicians who created their own fashion styles. These performers gained at- tention for Harajuku, and the area was turned into one of the main fashion districts in Tokyo. Nowadays, Harajuku is filled with small shops that sell Cosplay, Punk, Lolita, and Girly fashions, with Cosplay and Lolita as the most famous. Cosplay (costume play), originated from obsessive fans of anime and manga known as Otaku, first appeared in the early 1970s (Kotani, 2004), is a kind of amateur performance in which peo- ple dress themselves according to a particular fiction character, in order to entertain themselves in the world of imagination. Lolita fashion, developed from Cosplay of J-rock music, was first seen around Harajuku in the late 1990s (Katsuhiko, 2007) and came to its peak of popularity in the mid 2000s. Without any regard to the sexual connotations portrayed by Vladimir Nabokov’s novel “Lolita” (1955), Lolita style repre- sents the look of being cute and elegant. The style is inspired by Rococo, Victorian and/or Edwardian fashion with emphasis on cuteness. The costume was originally characterized by a knee length skirt or dress in a bell shape assisted by petticoats, worn with a blouse, knee high socks or stockings and a headdress. Lolita has various different sub-styles such as Gothic Lolita, Casual Lolita , and Hime Lolita , in which designs a nd colors a re different (Neko, 2008). Lolita is a special fashion style that has a strong subculture and community. According to Holson (2005), Lolita followers have created a community website for members to communicate and maintain their subculture iden- tity. Harajuku is also known for kawaii fashion such as Girly styles. Kawaii means cute in Japanese which can be thought of as precious and adorable. Girly is one of the Casual sub-styles, with casual clothes that emphasized the kawaii concept. Ac- cording to Kinsella (1995), kawaii culture is rooted in Japanese society especially among female, and any product which is considered cute usually sells well in the Japanese market. Girly is one of the long lasting fashion styles in Japan, and its influ- ence is often displayed on popular magazines and the clothes commonly come in floral printed or pale colors. Girls who wear girly styles also wear soft make-up and use accessories with cute cartoon characters. Shibuya, another fashion area close to Harajuku, is also rec- ognized as the birth place of distinctive fashion styles. In the past 20 years, the fashion style in Shibuya has changed occa- sionally from Kogal to Mamba. Although Kogal fashion has more or less disappeared, Gyaru, a dilution of Kogal, exists as one of the mainstream fashions. Gyaru consists of ordinary outfits but the clothing style is sexier than other fashions and the make-up style is heavier than others. Shibuya is also known for its night life where night clubs, bars, lounges, and karaokes are popular. The night life in Shi- buya has created a new fashion style called “Ageha” meaning swallowtail butterfly. Ageha is a fashion style related to a host- ess club culture, and emerged to mainstream attention in late 2007. The costume is similar to Japan’s hostess fashion style but with rather baby-faced look. The emphasis is on eye make- up using heavy liquid eyeliner, false lashes and special contact lenses to make the eyes appear almost inhumanly larger. In addition, Ageha favors pale skin, light hair colors, and volumi- nous hair (Misha, 2010). They adorn their bodies with sparkling accessories and luxury handbags. The Role of Fashion Magazines in Japan Fashion magazines are an important media outlet that intro- duces the latest fashion trends to readers. Normally, magazines are used for several purposes such as self-improvement, inspi- ration, and as a means to understand social behavior (Levine & Smolak, 1996; Thomsen et al., 2002; Tiggemann, 2005). There are over 50 fashion magazines published each month in Japan and these magazines can be categorized according to the fash- ion styles that they present. In general, these magazines are composed of fashion shoots, dress up guidelines, fashion snap shots from local streets, make-up guide s, and trendy hair sty les. At present, Gisele, Koakuma Ageha, Kera, Non-no, Ray, and ViVi are prominent fashion magazines, each presenting a dis- tinctive fashion style. It is widely thought that these magazines play a significant role in guiding the fashion styles of young girl. This seems to be the case especially among secondary school girls imitating the styles found in magazines. Gaunlett (2002) mentioned that teenagers are more engaged with the magazines than older women. “They are in the way of learning how women should be like by women’s magazines, and the fashion magazines give them the inculcation for being body attractive”, but for older age women “they highlighted the importance of being your- self.” Dynamic of Fashion Styles From the 2006 results and from the general acceptance of fashion trends in Japan, this paper categorizes Japanese street fashion mainly into 6 types: Casual, Gyaru, Onei (older sister style), Mode, Lolita, and OL (Office lady). Figure 1 illustrates the different fashion styles. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 294  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. Figure 1. Illustrative representation prominent Japanese street styles. A brief description of each style: Casual style is simple, non-distinctive, relaxed, and informal appearance. Gyaru cloth is florid, exposed and body-tight. Onei costume is extremely feminine and mature, and decorated with lace and ribbon. Mode cloth is designed in a similar concept of haute couture. Lolita outfit is influenced by Rococo, Victorian, and Edwardian styles, where headwear, bloomers, socks, shoes, and accessories such as umbrella and bag are basic elements. OL design is conserva- tive, and resembles the fashion of working women. According to the results in 2006, 34% of the respondents considered their fashion style as Casual, 25% as Lolita, 16% as Onei, 7% as Gyaru, 4% as Mode, 3% as OL, while 11% did not belong to any particul ar t ype. The results in 2008, showed a significant increase of those wearing Casual style, which jumped from 34% to 43%. The percentage of Gyaru wearers remained the same as in 2006. On the other hand, the results showed a decreasing number of Onei style, while Mode, Lolita, and OL disappeared from the an- swers of the respondents. In addition, two new types of fash- ions were observed from the answers of the respondents which were Hime and Ageha. Hime (princess) cloth is adaptation of Lolita fashion combine with Gyaru and Onei fashions. The style represents the look of old-style European royalty. Hair is curled and well cared. Ageha cloth is glamorous and sexy with fundamental inspirations by Gyaru and hostess fashions. In 2010, the majority of the respondents were Casual wearers at 50.7%, 8.0% of the respondents claimed themselves as Girly wearers, and 3.1% were Onei followers. Mode reappeared with 2.5%, and 8.0% did not belong to any particular fashion style. In 2011, Casual was the most popular fashion style among the respondents with 47.5%, Girly was at 6.8%, Onei at 1.9%, Mode 0.8% and 15% chose no particular fashion style. In addi- tion, new styles were observed in the answers of the respon- dents in 2010 and 2011. Mori girl (Forest girl), Natural, and Yama girl were the name given to these new styles. Mori girl fashion is normally loose dresses or vintage prints. Mori means forest in Japanese and the style looks like a girl from the forest in a fairytale. Natural fashion is loose clothes with earth tone colors. Yama girl fashion is a combination of casual and hiking costumes with vivid colors, the trend which developed in 2009 after the rise in popularity of outdoor activities among young people. The illustrative figure of Ageha, Hime, Mori girl, Natural, and Yama girl is shown in Figure 2 and the birth and progression of each fashion style among the respondents is shown in Figure 3. Fashion Transformation Process The results between 2006 and 2011 showed the movement of each fashion styles in each year. Based on Sproles (1974) fash- ion 5 phases life-cycle, styles with substantial number among the respondents such as Lolita, Onei, Ageha, and Mori girl were observed as displayed in Figure 4. According to the fashion genre circle shown in Figure 4, Onei and Lolita were in phase 4 in 2006. At this phase Onei and Lolita had reached their highest level of acceptance in society and were worn by a large and visible number of people includ- ing the respondents. On the other hand, Mori girl was in its first phase where it was introduced and adopted by so called con- sumer fashion change agents who are leaders of collective taste within their social networks. The term “Mori girl” first ap- peared in 2006 on a Japanese social network site called Mixi before it was observed in Harajuku in 2008 (Steele, 2010). Ageha was in the second phase which was worn mainly within the social network of the fashion change agents as a part of their unique life-style. In addition, it became visible as a new alternative fashion. In 2008, Onei and Lolita were in phase 5. Ageha Hime Mori girl Natural Yama girl Figure 2. Illustrative representation of fashion style emerged between 2008-2011. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 295  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 296 Figure 3. The birth and progression of each fashion style am o ng the respondents from 2006-2011. Figure 4. Fashion genre circle of Lolita, Onei, Ageha, and Mori girl among the respondents between 2006 and 2011.  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. At this stage their decline and obsolescence were forced by the new fashion alternatives and the level of popularity decreased. In contrast, Ageha and Mori girl were in phase 3 where they passed the introductory initiation of the fashion process and further gained social acceptance within and across their social network. In 2010, Ageha and Mori girl moved to phase 4, as observed in the survey that they were selected a s personal style s among the respondents. Further, the results showed that there was a significant change in Japanese street fashion since 2008, where the per- centage of casual wearers had significantly increased. 2008 was a turning point behind which the main driving force was thought to be the effect of economic recession. To analyze this change the fashion transformation process model proposed by Cholachatpinyo et al. was employed. By first looking at the cause of the transformation at macro- subjective level, it could be seen that in 2007, Japan suffered from the global economic recession (Abe, 2012) where the Japanese consumer confidence index started to decline in Oc- tober and continued to slide over 29% within the following year (Economic and Social Research Institute, 2004). This drop clearly indicated consumer spending slump for commodities including fashion objects. Extended analysis into the macro- objective level showed, however, that apparel sale was ex- pected to be the most important category of retail sales during the economic downturn (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2010; PwC, 2011). In process by which industrial trend setters chose fashion style for investment, there was a process similar to that suggested by collective selection theory (Blumer, 1969) of which the outcome saw casual fashion as the leading style. As a result, casual fashion was marketed in various forms to adapt to multiple socio-economic classes. At the micro-objective continuum, Leaders of Fashion retail sector, such as western fast fashion companies like Zara and H&M, first opened their Japanese branches in 2005 and 2008 respectively, had continued to expand their branches and sales volume (Inditex Group, 2010; H&M, 2012). These fast fashion companies provided fashionable and quality clothes with af- fordable prices that were suitable for the economic recession period. Their mass production and mass communication strat- egy gave the outcome similar to that suggested by the mass market theory proposed by Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955) by which products were introduced to all socioeconomic classes simultaneously. This practice was successful to help them ex- pand deeper among Japanese consumers and led to the in- creased number of casual wearers. Lastly the analysis into the micro-subjective level showed that, affected by the economic recession, consumers sought to dress economically in a fashionable way by choosing fast fash- ion. This could be observed by the increased number of casual wearers in our survey. Also the emergence of several new styles such as, Ageha, Hime, Mori girl, Natural, and Yama girl were apparent where styles were merged from at least two dif- ferent casual fashion sub-styles. Influence of Fashion Sources One part of the questionnaire asked the respondents what their sources of information on fashion trends were, and how these sources inspired their sense of styles. The mean values of each source of fashion information are shown in Table 1. There were marginal changes in the mean values of all Table 1. Mean values of fashion sources in e a c h year. Year Sources 2006 2008 2010 2011 TV 3.07 3.05 3.04 3.05 Movies 2.20 2.20 2.68 2.66 Newspapers/general magazines2.90 2.80 2.66 2.73 Fashion magazines 4.22 4.30 4.41 4.51 Animated cartoons/comics 1.60 1.65 1.91 1.85 Internet 2.15 2.27 3.21 3.47 Store displays 3.78 3.78 4.07 4.06 Fashion shops 4.01 4.09 4.38 4.38 Passers-by 3.80 3.87 4.08 4.03 Artists 3.24 3.31 3.48 3.53 Fashion shop staff 3.70 3.64 3.95 3.95 Friend’s style 3.40 3.52 3.81 3.74 Family members 2.07 2.11 2.24 2.16 sources when comparing the results over four years, except for the internet. The sources that had mean values below 3 were movies, newspapers/general magazines, animated cartoons/ comics, and family members. Their mean values remained sta- ble from 2006 to 2011 and they didn’t seem to have any strong influences on the respondents’ fashion styles. On the other hand, TV, show windows, passers-by, artists, fashion shop staff, and friend’s styles were the sources that moderately influenced the respondents with mean values in the range of 3 to 4. Fashion magazine and fashion shop were the most influential sources for the respondents and the mean values for these sources were over 4. It can be said that fashion magazines’ influence was high and will remain stable as its mean values only fluctuated slightly. A notable change could be seen in the mean value of the internet which has significantly risen in the past few years, with overall 26% gain in the five year period surveys. The Internet has become an important purchasing channel in Japan with a rapid rise in the number of users each year. PCs and mobile phones were increasingly being used to shop online and to gain access to fashion information. Moreover, the number of Japa- nese Smartphone owners increased by 33.5% from September to December 2010 (ComScore, 2011). In addition, many fash- ion brands and department stores such as, Beams and Takashi- maya were applying e-commerce models to serve their custom- ers (Nagasawa & Salsberg, 2010). Looking from the recent trend it would be fair to say that the internet would become even more important to the fashion business in the near future. Evolution of Fashion Magazines Although the previous section showed that the respondents received information on fashion mainly from three sources; Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 297  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. fashion magazines, followed by fashion shop, and passers-by. However, this research deals mainly with fashion magazines, due to the fact that they were the most influential fashion sources, and they provided fashion view point that could easily be shared and traced between the respondents and the re- searcher. This section is devoted to the result and discussion on transformations related to fashion magazine. From the survey result, in 2010, 63.36% of the respondents had at least two different favorite magazines, and around 42.85% of them read fashion magazines that contained different fashion concepts. The result shown good agreement with Gauntlett (2002) who pointed out that women’s fashion maga- zines are powerful in representing and transmitting the “ideal female” images to their female readers, and they may affect readers’ behaviors in self-image creation and consumption. For these girls, fashion magazines remained the main fashion in- spiration where fashion ideas were taken and developed to their personal styles. The second section of the questionnaire asked the respon- dents to specify their favorite fashion magazines and the results were ranked to five orders as shown in Table 2. These magazines displayed different kinds of fashion styles as follows, Non-no, Mina, PS, Seda, Sweet, and Zipper dis- played Casual fashions. ViVi displayed Gyaru styles, while CanCam and Ray presented Onei fashions. Non-no and ViVi were always popular among the respondents, and ViVi became more popular each year. The popularity of many of the other magazines changed year by year. However, magazines such as CanCam and Mina had significantly lost their popularity among the respondents in the latter years. The ranking of the fashion magazines reflected and also could be used to explain the movement of each fashion style in Japan. When Onei style was very popular among the girls in 2006, CanCam was ranked as the second most popular maga- zines among the respondents. However, in the past few years, the popularity of the Onei style decreased, as well as CanCam magazine which became less popular among the respondents in other years. Another link can be drawn for one of the most famous CanCam’s model, “Ebi chan” or “Yuri Ebihara”, a Japanese model and actress, who was a symbol of Onei fashion, and had had an exclusive contract with CanCam for six years. Like CanCam, most Fashion magazines in Japan commonly employed the same models repetitively for their fashion shoots, and the models came to represent a particular fashion style. Ebi chan gained her highest popularity in 2006, where she appeared in several advertisements, movies, dramas, and magazines. Due to Ebi chan’s numerous appearances in Onei fashion, Onei became one of the most popular styles in Japan. As Ebi chan career began to wind down, so did Onei fashion’s hold on the top place among fashion styles. Now over 30, although she remained one of the Onei fashion’s faces, Ebi chan was no longer the face of CanCam and no longer popular among the survey’s young respondents. A perusal of the magazines showed modifications in the fashion styles over the study period. For example, ViVi’s style became less sexy and more casual, Non-no, PS, Seda, and Zip- per retained their casual concepts but their styles became more decorative and cuter than in the past. CanCam continued its Onei concept and lost popularity among the respondents. In contrast to CanCam, Ray modified its fashion styles by adopt- ing casual and kawaii elements and replaced CanCam’s posi- tion in the magazine ranking. It is fair to say that in recent years Table 2. Ranking of popular fashion magazines among the respondents. Year Magazine ranking2006 2008 2010 2011 1 Non-no Non-no ViVi ViVi 2 CanCamViVi Non-no Non-no 3 PS Sweet Ray Seda 4 ViVi PS Zipper Ray 5 Mina Ray Seda Sweet and zipper magazines have had to adjust to changes in their industry. That is to say, as a result of the economic downturn, the advent of fast fashion, and the increase in popularity of kawaii culture, styles have become increasingly mixed. In addition, many magazines started using the internet as a means of connecting to their readers through webpage that provides beauty tips, blogs, and shopping information. The shopping pages were convenient for the readers to find the items that they like in the magazines, also it was another chan- nel to expand the sale volume for the fashion companies. As model influence was vital to the magazine business, models were connecting with their readers and fans via their blogs where personal information, fashion styles, and activities were posted, this could be one of the magazine strategies to keep it popular among the readers. Fashion Dependency and Self-Expression The respondents were asked to identify their personal styles and their favorite fashion magazines, and a comparison be- tween their answers and their photographs were examined in order to understand the influence of the fashion magazines. In 2006, the respondents followed the fashion styles provided by the magazines and hardly modified the styles that they wore. Therefore, it was not so difficult to distinguish their fashion styles by their appearances. The imitation of the style was eas- ily observed in Lolita fashion, where wearers strictly adhered to the dress code of the style of the original concepts as shown in Figure 5. Luo (2008) also found in her study that Japanese teens were easily affected by the fashion from the magazines and some even copied and dressed exactly like the model in the magazines. In 2010, many of the respondents dressed in con- trast to the style suggested by their favorite magazines as could be seen in Figure 6, especially for the Kera’s readers who did Figure 5. Lolita fashion among the respondents in 2006. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 298  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. Figure 6. Fashion styles of reade rs from different magazines in 2010. not wear Lolita clothes. By 2010, it appeared that young women were using magazines more in a mix and match fash- ions, combining fashion styles from several fashion magazines to create their own identity. As a result, it became difficult to distinguish their styles by their appearances. The transformation of fashion styles could be observed by comparing the photographs of the respondents year by year. Figure 7 showed the movement of Casual styles. Casual style was quite simple in the first two years of the survey, consisting mainly of a t-shirt with any kind of bottom. In 2010 and 2011, the t-shirts came with cute designs and decoration such as car- toon characters, ribbons, and laces. The Casual style moved from very simple to decorative and mixed. In addition, the range of Casual styles became wider and merged with other styles as shown in Figure 8. Figure 9 showed examples of each style asserted by the respondents in 2010 and 2011. The fashion styles selected by the respondents were influenced by casual elements, which made their styles difficult to distinguish at first glance. Besides, many girls decorated themselves with accessories such as cardigans, scarfs, and necklaces to highlight their individualistic styles. Japan is a collectivist society where people respect group processes and decisions, for them keeping a good and harmo- nious relationship within the group is important (Wong & Ahu- via, 1998). Moreover, it is a unique society where imitation is not considered as an inappropriate behavior (Tada, 1994). Un- der this social structure teens were encouraged to be obedient and discouraged to express their individualism in contradiction to social norms. However, teens are generally known for want- ing to change social norms, and for rebelling against the main- stream. The results of 2006 showed that street fashion played a major role in giving teens choices to be different from the mainstream by belonging to a particular fashion group. As the presence of the fashion groups subsided in Japanese society in latter years, and due to the fact that the fashion market has changed and now offered variety of casual clothing more popu- lar than those particular group fashion styles, teens are thus less influenced by group fashion and turned to casual style. How- ever in desperate need to stand out as an individual from the social norm, they have opted to create their uniqueness by mix- ing their experience in the past with what is currently available in the market resulting in even more diversified and unclassi- fied new born styles under the realm of casual fashion. Conclusion Japanese street fashion was generated in the 1990s by teens who wanted to create their generational identity. Later, it was accepted as mainstream fashion and became rooted as a general Figure 7. Casual styles among the respondents from 2006-2010. fashion concept among teenagers in Japan. Since its emergence, street styles have been transforming dynamically as many styles disappeared and new styles emerged in the fashion scenario. This research was undertaken in order to trace the chronologi- cal change of street fashion from 2006 to 2011, and was based on the surveys of female college students in Tokyo. The results were used to show the transformation of street fashion, and to explain how/why casual styles became the key concept for the fashion industry. In 2006, the street styles were categorized mainly into 6 types which were Casual, Gyaru, Onei, Mode, Lolita, and OL. In 2011, these street styles were still apparent among the respondents but the number of casual wearers in- creased around 13.5% comparing to the result in 2006. 2008 was a turning point for Onei and Lolita fashions as they began losing popularity among the respondents. In 2010, several new styles such as Hime, Ageha, and Natural became popular among respondents. To understand the cause of the surge in casual style’s popularity, research into the fashion market throughout the course of 5 years was conducted. It can be con- cluded that the economic recession in 2007 and the growth of fast fashion business were two main factors that led to the radi- cal changes of street fashion, and as a result casual fashion became more popular and new styles were born. Another significant aspect of the study was researched into where respondents obtained fashion information. The findings showed that although fashion magazines remained the most popular fashion source in 2011, they have lessened influence on guiding respondents’ fashion styles. Furthermore, it became obvious that the internet was becoming an important source of fashion information year by year. The result of the magazine ranking survey showed that the fashion magazines that presented casual fashion were always ranked as the most popular magazine among the respondents. In addition, the magazine ranking reflected the popularity of fash- ion styles in each year. A perusal of the magazine showed that many magazines combined casual elements to their original concepts. In 2010, their styles became overlapping and were difficult to classify. The magazines with casual combination remained popular among the respondents. On the other hand, the magazines that maintained their original concepts, for ex- ample CanCam, lost their popularity among the respondents. By 2011 the respondents were relying less and less on fash- ion magazines for their fashion styles. They were more apt to combine different styles which made street fashion difficult to classify by appearance. Teens will more than likely to continue to express identity through fashion and this will invariably be reflected in a variety of new Japanese street fashion style. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 299  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 300 Figure 8. Wide range of casual styles among the respondents in 2010-2011. Figure 9. Several types of fashi o n s tyles selected by the respondents in 2010-2011. Limitations ertheless, although female college students are one of the dominant contributors of street fashion, there are other groups of people who also contribute to the Japanese street fashion. Therefore, application of findings from this research to other different environments will require scholar judgments and pos- sibly additional research works. For future research, random sampling and wide ranges of respondents such as, passers-by, high school girls or young boys may be required in order to provide the larger picture of the Japanese street fashion. This study showed the transformation of Japanese street fashion during a five year period between 2006 and 2011. While this study uses the sample of female college students to explain the transformation of street fashion, there are limita- tions for usage and applications of the study due to the scope of study and its survey sampling. The researchers believe that the result of survey with sampling of female college students could explain the transformation of street fashion as discussed. Nev-  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. Acknowledgements I thank all the respondents for their participation. Special thanks to Yuriko Hashimoto, Chika Kondo, Mizue Kosuge, students under the supervision of Professor Mizutani, Raleigh Gosney, Charoen Jiewsang, Frank Pumipuntu and Xiong Qian for their help. REFERENCES Abe, N. (2010). Japan’s shrinking economy. URL (last checked 11 January 2012). http://www.brookings.edu/opinions/2010/0212_japan_economy_abe. aspx Blumer, H. (1969). Fashion: From class differentiation to collective selection. Sociological Quarterly, 10, 275-291. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1969.tb01292.x Cholachatpinyo, A., Padgett, I., Crocker, M., & Fletcher, B. (2002). A conceptual model of the fashion process-part 1. The fashion trans- formation process model. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Man- agement, 6, 11-23. doi:10.1108/13612020210422428 Clarke, J. (1993). The Skinheads and the magical recovery of commu- nity. In S. Hall, & T. Jefferson (Eds.), Resistance through rituals: Youth subcultures in post-war Britain (pp. 99-102). Oxon: Rout- ledge. Clarke, J., Hall, S., Jefferson, T., & Roberts, B. (1993). Subcultures, cultures, and class. In S. Hall, & T. Jefferson (Eds.), Resistance through rituals: Youth subcultures in post-war Britain (pp. 9-74). London: Routledge. Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: The creation of the mods and rockers. London and New Yor k: Routledge. ComScore (2011). Smartphone adoption continues to grow in Japan. URL (last checked 3 January 2012). http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2011/2/Sma rtphone_Adoption_Continues_to_Grow_in_Japan Crane, D. (2000). Fashion and its social agendas: Class, gender, and identity in clothing. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Economic and Social Research Institute (2004). Monthly consumer confidence survey covering all of Japan summary. URL (last checked 3 January 2012). http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/stat/shouhi/1202shouhi-e.html Economist Intelligence Unit (2010). Japan: Consumer goods and retail report. Gauntlett, D. (2002). Media, gender, and identity: An introduction. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203360798 Godoy, T., & Vartanian, I. (2007). Style deficit disorder: Harajuku street fashion, Tokyo. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. London: Methuen. doi:10.4324/9780203139943 Holson, L. M. (2005). Gothic lolitas: Demure vs. dominatrix. New York Times (Online). URL (last checked 3 January 2012). http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/13/fashion/13GOTH.html Hume, M. (2002). Tokyo glamorama. Harper’s Bazaar, October. H&M (2010). The H&M annual report: Part 1: H&M in words and pictures. URL (last checked 3 Ja nua ry 2012). http://about.hm.com/content/hm/AboutSection/en/About/Investor-Re lations/Financial-Reports/Annual-Reports.html Ijiri, K. (1990). The breakdown of the Japanese work ethic. Japan Echo XVII, 4, 35-40. Inditex Group (2011). Inditex annual report 2010. URL (last checked 3 January 2012). http://www.inditex.com/en/shareholders_and_investors/investor_rela tions/annual_reports Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld P. F. (1955). Personal influence. Glencoe. IL: The Free Press. Katsuhiko, I. (2007). Gothic and lolita. London: Phaidon Press Lim- ited. Kawamura, Y. (2006). Japanese teens as producers of street fashion. Current Sociology, 54, 748-801. doi:10.1177/0011392106066816 Kinsella, S. (1995). Cuties in Japan. In L. Skov, & B. Moeran (Eds.), Women, media, and consumption in Japan (pp. 220-254). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. Kotani, S. (2004). Why are Japanese youth today so passive. In G. Mathews, & B. White (Eds.), Japan’s changing generations: Are young people creating a new society (pp.31-46). Oxron, OX: Rout- ledge Curzon. Levine, M. P., & Smolak, L. (1996). Media as a context for the devel- opment of disordered eating. In L. Smolak, M. P. Levine, & R. Striegel-Moore (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of eating disorders: Implications for research, prevention, and treatment (pp. 235-257). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Luo, X. (2008). Women’s fashion magazines in Japan: Women vs. women’s fashion magazines in relation to self-image creation and consumption. Master’s Thesis, Lund: Lund University. Mead, R. (2002). Letter from Tokyo: Shopping rebellion: What the kids want. New Yorker. URL (l ast c he ck ed 3 Ja nu ary 2012). http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2002/03/18/020318fa_FACT Midgley, D., & Wills, G. (1979). Fashion marketing. Lateral marketing thought(s). Brandford: MCB Publications. Miller, L. (2004). Youth fashion and changing beautification practices. In G. Mathews, & B. White (Eds.), Japan’s changing generations: Are young people creating a new society (pp.83-98). Oxron, OX: Routledge Curzon. Misha, J. (2010). A day in the life of a Japanese “hostess” model. CNNGo. URL (last checked 3 January 2012). http://www.cnngo.com/tokyo/life/day-life-japanese-hostess-model-4 46351 Nabokov, V. (1955). Lolita. Paris: Olympia Press. Nagasawa, Y., & Salsberg, B. (2010). Fashion forward: Keeping and setting the pace in Japans fast-changing apparel market. McKinsey & Company. URL (last checked 3 January 2012). http://csi.mckinsey.com/knowledge_by_region/asia/japan/fashion_fo rward Nathan, J. (2004). Japan unbound: A volatile nation’s quest for pride and purpose. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Neko, N. (2008). Lolita and Japanese society. URL (last checked 3 February 2012). http://www.lolitafashion.org/index.html Park, J. (2011). An investigation of the significance of current Japanese youth subculture styles. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 4, 13-19. doi:10.1080/17543266.2010.516772 Polhemus, T. (1994). Streetstyle. London: Thames and Hudson. PwC (2010). Strong and steady 2011: Outlook for the retail and con- sumer products sectors in Asia. URL (last checked 10 February 2012). http://pwccn.com/webmedia/doc/634275111903090644_rc_ap_prod ucts_outlook_2011.pdf Robinson, N. (2009). British followers of Japanese fashion. BBC News. URL (last checked 5 January 2 0 1 2). http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/haveyoursay/2009/06/090625_yo urstorymanba.shtml Skov, L. (1996). Fashion trends, japonisme and postmodernism. Theory, Culture & Society, 13, 129-151. doi:10.1177/026327696013003007 Skov, L. (2005). The role of fashion weeks and trade fairs in the global fashion business. Proceeding of the Encounters in the Global Fash- ion Business Conference. 20-21 Apri l 2005, Copenhagen. Style Arena (2002). Tokyo street style. URL (last checked 12 January 2012). http://www.styl e -arena.jp/ Sugimoto, Y. (2008). Fashion history of Japan. URL (last checked 12 January 2012). http://www.jetro.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id =431&Itemid=388 Tada, M. (1994). Japanese gestures: Modern manifestations of a clas- sic culture. Stahl, T. S., & Stahl, A. K., Translated, Dallas, TX: Three Forks Press. Thomsen, S. R., McCoy, K. J., Gustafson, R., & Williams, M. H. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 301  A. JIRATANATITEENUN ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 302 (2002). Motivations for reading beauty and fashion magazines and anorexic risk in college-age women. Media Psychology, 4, 113-135. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0402_01 Tiggemann, M. (2005). Television and adolescent body image: The role of program content and viewing motivation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 361-381. doi:10.1521/jscp.24.3.361.65623 Wong, N. Y., & Ahuvia, A. C. (1998). Personal taste and family face: Luxury consumption in confucian and western societies. Psychology & Marketing, 15, 423-441. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199808)15:5<423::AID-MAR2>3.0.C O;2-9 Sproles, G. B. (1974). Fashion theory: A conceptual framework. In S. Ward, & P. Wright (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 1, pp. 463-472). Minnesota: Association for Consumer Research. Sproles, G. B. (1981). Analyzing fashion life cycles-principles and perspectives. Journal of Marketing, 45, 116-124. doi:10.2307/1251479 Simmel, G. (1904). Fashion. International Quarterly, 10, 130-155. Steele, V. (2010). Is Japan still the future. In V. Steele, P. Mears, Y. Kawamura, & H. Narumi (Eds.), Japan Fashion Now. Italy: Conti Tipocolor. Veblen, T. (1912). The theory of the leisure class. New York: Macmil- lan. |