Advances in Applied Sociology 2012. Vol.2, No.4, 280-291 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.24037 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 280 Determinants of Saving among Low-Income Individuals in Rural Uganda: Evidence from Assets Africa Gina A. N. Chowa1*, Rainier D. Masa1, David Ansong2 1School of Social Work, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA 2Brown School of Social Work, Washington University, St. Louis, USA Email: *chowa@email.unc.edu, rmasa@email.unc.edu Received September 8th, 2012; revised October 10th, 2012; accepted October 22nd, 2012 Although research has shown that poor people in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), including those living in ru- ral areas save, little is known about the factors that influence saving and asset accumulation among this population. Using three theoretical perspectives on saving and asset accumulation, this study examines the broader determinants of saving and asset accumulation among low-income individuals in rural Uganda. Compared with the individual-oriented and sociological perspectives, institutional theory explains a large part of the variance in saving outcome among rural, low-income households. Wealth, proximity to finan- cial institutions, financial education, and financial incentives are positively associated with higher saving performance. Findings suggest that poor people can and do save, particularly when institutional barriers to saving are removed. Institutional structures, which encourage low-income individuals to save, may con- tribute to a poverty reduction policy that shifts from just income supplementation to a more inclusive wealth promotion policy that assists people in creating their own pathways out of poverty. Keywords: Saving; Sub-Saharan Africa; Rural Uganda; Theory; Asset Building; Institutional Theory Introduction Numerous reasons, including low and irregular income and lack of access to financial services, have been posited to con- tribute to sub-Saharan Africa’s (SSA) low formal savings rate1. Access to financial services, including deposit or savings ac- counts, remains a privilege for most of the population (Consul- tative Group to Assist the Poor, 2010). In rural Uganda, where 86% of the country’s 31 million people live, only 10% of the population has access to basic financial services (Chemonics International, 2007). Inadequate physical infrastructure, oner- ous documentation requirements and high account fees have been found to be associated with lower levels of formal finan- cial service use in developing regions (Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, & Peria, 2008). In spite of the barriers, empirical research has shown that poor people in SSA, including those living in rural areas, save (Chowa, Masa, & Sherraden, 2012; Collins, Mur- doch, Rutherford, & Ruthven, 2009; Dupas & Robinson, 2009). However, limited empirical research has been conducted to understand the factors that influence saving and asset accumu- lation among rural individuals and households in SSA. Savings and assets are of interest to policymakers and schol- ars across disciplines because of their importance to individuals, households, and the economy. For individuals and households, economic security throughout the life course is inherently linked not only to income but also to asset ownership. Savings and assets are important because, unlike income, they are what individuals and families accumulate and hold over time. Assets, such as savings, also generate returns that generally increase lifetime consumption and improve a family’s well-being over several generations. Savings and assets provide a cushion to fall back on during hard times and emergencies. Asset-poor fami- lies in SSA become more vulnerable to unexpected economic events or natural disasters and as a result, to their long-term adverse consequences (Hoddinott, 2006). For the economy at large, savings represents an important source for the financing of investment in developing countries. The savings rate of a country has been found to be strongly correlated with invest- ment and growth rates (Attanasio & Banks, 2001). Although two decades of experimentation and research on saving and asset building suggest that linking low-income families with saving and asset-building strategies has the poten- tial to positively influence family well-being outcomes, includ- ing economic, educational, and health-related results, (Chowa, Ansong, & Masa, 2010; Chowa, Masa, & Sherraden, 2012; Erulkar & Chong, 2005; Lerman & McKernan, 2010; Schreiner & Sherraden, 2007; Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2009; Williams Shanks, Kim, Loke, & Destin, 2010), most of the studies on determinants of household saving have focused on middle- to upper-income families. Few empirical studies have investigated savings’ determinants among low-income individuals and fami- lies, and those that have have primarily been completed within the United States (Curley, Ssewamala, & Sherraden, 2009; Han & Sherraden, 2009). Building on existing theories and empiri- cal evidence, this study contributes to knowledge in two ways. First, the study explores factors that affect saving among par- ticipants of an asset-building program in rural areas of Uganda. As mentioned earlier, little is known about the factors affecting saving and asset accumulation in rural, low-income populations in developing economies, particularly in SSA. Data used in this study came from an asset-building intervention targeted to low-income individuals in rural communities in a developing 1In SSA, there are 163 bank accounts (compared with 635 bank accounts in other developing regions) and 28 bank loans (compared with 245 bank loans in other developing regions) per 1000 adults (Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, 2010). *corresponding author  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. country. Observed savings determinants from a quasi-experi- mental setting that intentionally provides an opportunity to save or build assets may be quite different than those observed from national data sets. Second, the study examines whether diverse theories of saving, which have been primarily developed in more industrialized societies, can explain savings behavior among low-income households in developing countries. This study adds to a growing body of research (Curley, Ssewamala, & Sherraden, 2009; Han & Sherraden, 2009) that examines competing theories of saving in a single model with a compara- tive approach. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to concurrently examine diverse theories of saving using quasi- experimental household-level data from rural, low-income populations in SSA. Theories of Savings and Evidence from SSA and Other Developing Economies Examining and explaining determinants of saving and asset building have garnered attention from scholars across numerous disciplines. Economic theories put primary emphasis on income and age as predictors of saving and asset accumulation (Modi- gliani & Ando, 1957). Behavioral economists and economic psychologists have recognized the role of self-control, motives, and other personality characteristics on saving (Katona, 1975; Thaler & Shefrin, 1981; Wӓrneryd, 1999). Sociologists have been interested in how class and social stratification influence saving and asset accumulation (D’Souza, 1981; Sorensen, 2000). Social workers have examined the effects of institutional factors such as access, incentives, expectation, and facilitation in promoting saving (Beverly & Sherraden, 1999; Sherraden, 1991; Sherraden, Schreiner, & Beverly, 2003). Similar to Han and Sherraden (2009), this section classifies existing theories into three perspectives: 1) an individual-oriented perspective; 2) a social stratification perspective; and 3) an institutional per- spective. Individual-Oriented Perspectives The individual perspective in this study includes neoclassical economics, economic psychology, and behavioral economics. Neoclassical economic theory assumes that individuals are rational beings who respond in predictable ways to changes in incentives; and assumes that individuals have perfect knowl- edge and access to perfect markets. Two prominent neoclassical economic theories include: 1) the life cycle hypothesis (LCH; Modigliani & Ando, 1957); and 2) the permanent income hy- pothesis (PIH; Friedman, 1957). Both theories assume that individuals and households are concerned about long-term consumption opportunities and therefore, explain saving and consumption in terms of expected future income. The LCH posits that savings will be used to smooth consumption when income varies by age. A main idea of the LCH is that working people are savers, whereas children and retired people are not. Thus, differences in consumption and saving among house- holds are attributed to age differences (Modigliani & Ando, 1957). While people are working, they use their income to pro- vide for the household consumption, while at the same time they are saving to provide for their retirement. On the other hand, the PIH suggests that savings decisions are based on in- come being perceived as either permanent or temporary. Households mainly spend the permanent income, while the temporary or transitory income is channeled into savings; and households are freely able to save and borrow to smooth their consumption (Friedman, 1957). Both economic theories view savings primarily as a function of income. Due to the limited availability of relevant data on low-in- come households in developing economies, literature cited in this study also includes data on middle- to upper-income households. Evidence from SSA and other developing countries, albeit mostly from middle- to upper-income households, sug- gests that income positively influences saving and in ways con- sistent with standard economic theories (Schmidt-Hebbel, Webb, & Corsetti, 2002). In Kenya, household income was found to be a statistically significant predictor of savings among rural farmers, entrepreneurs, and teachers (Kibet, Mutai, Ouma, Ouma, & Owuor, 2009). In Uganda, higher permanent and transitory incomes significantly increased the level of net deposits among households that reported owning bank deposit accounts (Kiiza & Pederson, 2001). Income was also a signifi- cant predictor of improved savings in India (Agrawal, Sahoo, & Dash, 2007; Athukorala & Sen, 2004), Morocco (Abdelkhalek, Arestoff, de Freitas, & Mage, 2009), Pakistan (ur Rehman, Bashir, & Faridi, 2011), and the Philippines (Bersales & Mapa, 2006). These findings suggest that households save a larger share of their income when that income is higher. Aside from income, age, including the age of the head of household and other household members, is an important pre- dictor of saving, according to neoclassical economic theories. Economic researchers commonly use dependency ratio, or those under age 15 and over 65 as a share of the total household composition, as an explanatory demographic variable. In the LCH, households with more children at home may save less until the children leave home, which would raise the per capita income of the household. Thus, higher dependency ratio nega- tively affects savings rates. Evidence from SSA and other de- veloping countries shows contradictory results. An increase in dependency ratio decreased saving, while a decrease in de- pendency ratio increased saving among households in Kenya (Kibet et al., 2009), Indonesia (Johansson, 1998), India (Ang, 2009), China (Ang, 2009), Morocco (Abdelkhalek et al., 2009), and Pakistan (ur Rehman et al., 2011). This result suggests that a reduction in the number of dependents relative to a working age population has eased household budget constraints, thus increasing savings, which is consistent with the LCH. However, other researchers have found no significant relationship be- tween savings rates and dependency ratio in developing coun- tries (Cornia & Jerger, 1982; Deaton, 1992; Schmidt-Hebbel et al., 2002). These nonsignificant findings are similar to Mason’s (1987, 1988) studies, which challenged findings that depend- ency ratio has a strong negative effect on saving. Mason quali- fies the negative effect of dependency ratio on savings by in- troducing the age factor. He demonstrates that, in some cases, the effects of the dependency ratio depend on the age of the dependents. In the Philippines, for instance, researchers found that the percentage of young dependents had a negative effect on savings, whereas, the percentage of the elderly had a sig- nificant positive effect on savings (Bersales & Mapa, 2006). Although evidence suggests that neoclassical economic theo- ries can predict savings behavior of households in developing countries, some researchers have argued that the application of LCH and PIH to explain savings behaviors of low-income households in developing countries can be problematic (Rosenzweig, 2001). For instance, PIH’s assumption that Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 281  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. households are freely able to save and borrow to smooth their consumptions may not be true in developing countries where low-income households have very limited access to a well- developed insurance and credit market (Rosenzweig, 2001). In addition, distinction between permanent and temporary income may not be evident in many parts of the developing countries where household income is minimal and irregular. Savings in low-income settings for long-term purposes, such as retirement, may not be substantial given that many households struggle to meet subsistence consumption level, especially in times of emergencies and other income shocks. Furthermore, the LCH may not effectively predict long-term savings in low-income settings in developing countries because many households, particularly rural households, include more than two adults, and adults of different generations. Since the life-cycle of the household is not the same as the life-cycle of the individual, it is not clear whose age matters for savings decisions (Deaton & Paxson, 2000; Rosenzweig, 2001). In SSA, for instance, evi- dence suggests that households change size and composition in response to income fluctuations (Fafchamps, Udry, & Czukas, 1998). Unlike neoclassical economic theories, the other two indi- vidual perspectives on savings in this study—economic psy- chology and behavioral economics—do not assume that people are rational and all-knowing. These two perspectives assume that personality characteristics and attitudinal variables affect saving and asset accumulation. The inclusion of psychological factors on savings research has been the subject of investiga- tions by early economic thinkers such as Jevons (1965), Mar- shall (1961), and Fisher (1977). Although they recognized that savings depend on economic factors, particularly income and its size and frequency, they also believe that there are various psychological characteristics that influence the temptation to spend and forego saving. Although fewer psychologists have investigated psychological determinants of saving behavior than economists, there are some established psychological models on savings behaviors, including those by Katona (1975), Ölander and Seipel (1970), and Lindqvist (1981). For instance, Katona’s theory of saving (1975) is partly determined by in- come and partly by some independent intervening factors. Two important factors are the ability to save (mostly objective data) and willingness to save (a variety of psychological variables). Ability to save refers to those who can save, whereas willing- ness to save is related to the degree of optimism or pessimism of economic conditions (Katona, 1975). Thus, ability to save does not guarantee savings because savings also depend on an individual’s willingness to save. Due to constraints on the availability of relevant data, there is no evidence thus far on the effects of psychological factors on the saving behavior of low-income households in developing countries. Although some evidence from industrialized countries shows that psy- chological predictors tend to have low explanatory power (Furnham, 1985; Lindqvist, 1981; Lunt & Livingstone, 1991), there is also some evidence suggesting that personality charac- teristics, including optimism/pessimism about economic condi- tion ( Lunt & Livingstone, 1991), perceived locus of control (Lunt & Livingstone, 1991; Perry & Morris, 2005), perceived ability to save (Sherraden & McBride, 2010), and future orien- tation (Webley & Nyhus, 2006) are associated with saving be- haviors. Behavioral economics integrates insights from psychology and economics. Behavioral economics qualifies some of the unrealistic assumptions of standard economic models of human behavior, such as unbounded rationality, unbounded willpower, and unbounded “selfishness” (Shefrin & Thaler, 1988; Thaler, 1994). According to this perspective, common human charac- teristics such as self-control and ability to delay gratification, mental accounting, use of rules-of-thumb, default options, and hyperbolic discounting shape financial behaviors and economic decisions (Ainsle, 1975; Angeletos, Laibson, Repetto, To- bacman, & Weinberg, 2001; Laibson, 1997; Mullainathan & Thaler, 2000; Shefrin & Thaler, 1988; Thaler, 1981). These characteristics can lead households to behave in ways that are inconsistent with their own priorities. However, little is known about the explanatory powers of these factors on savings be- havior of low-income households in developing countries. On the other hand, studies from industrialized countries have shown that self-control (Ameriks, Caplin, Leahy, & Tyler, 2004; Moffitt et al., 2010; Romal & Kaplan, 1995), and use of default options (Madrian & Shea, 2001; Thaler & Benartzi, 2004) shape saving behaviors of middle- and upper-income individu- als and households. Sociological Perspective Social stratification theory refers essentially to a distribution of power in society. The divisions in society, based on eco- nomically conditioned power, are called classes, which refer to any group of people that is found in the same economic situa- tion (D’Souza, 1981; Weber, 1967). Class and social stratifica- tion have strengths in explaining the factors affecting savings behavior among low-income households because class relates to the possession (or lack) of resources (economic or otherwise) necessary for individuals and households to save and build up their assets. Individuals and families in lower economic classes have limited access to information, resources, and services that can help them save and accumulate assets over time. When low-income families have assets, they are less likely to have access to additional resources that they can use to generate positive returns on the assets they already own. The economis- tic approach to class and social stratification suggests that a major explanation of class inequalities rests in the nature of access to, and take up of, material resources, as well as the institutions that govern such access (Crompton, 2008). In addi- tion to control and possession of economic resources, class and social stratification are powerful determinants of outcomes that can further shape saving and asset accumulation patterns. De- mand from social network members, particularly family mem- bers, can make it difficult to save and accumulate assets (Stack, 1974). Evidence suggests that poverty in extended families can impede saving and asset accumulation (Caskey, 1997; Chiteji & Hamilton, 2005; Heflin & Patillo, 2002). Some scholars have attributed asset poverty to other factors beyond the control of an individual, such as cultural origins (Al-Awad & Elhiraika, 2003), gender biased-cultural norms (Chowa, 2008), and finan- cial socialization in families, schools, or communities (Chiteji & Hamilton, 2005; Chiteji & Stafford, 1999; Cohen, 1994), and race (Oliver & Shapiro, 1995; Shapiro, 2004). Evidence from SSA and other developing countries suggests that class-related factors can explain savings behaviors of low-income households. Education has been found to be a sig- nificant predictor of savings in Kenya (Kibet et al., 2009), and the Philippines (Bersales & Mapa, 2006) but not in India (Agrawal et al., 2007). Higher education level translates to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 282  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. higher savings level. Occupation, which can be predicted by a person’s level of education, was also found to be a significant predictor of savings rates in rural Kenya (Kibet et al., 2009). With regard to access to other resources that can increase in- come and generate positive returns on existing assets, evidence from SSA is mixed. In Uganda, increases in the availability of credit resulted in higher savings levels (Kiiza & Pederson, 2001). Households with access to credit consistently hold higher net balances of savings than household without access to credit. However, in rural Kenya, improved access to credit re- sulted in savings reduction (Kibet et al., 2009). The authors cited that this contradictory finding could be due to observed savings being used for consumption purposes and rarely con- verted to income-generating assets. Furthermore, evidence also suggests that class-related factors, such as education, not only affect savings rate but also owner- ship of a formal savings account. In Uganda, the education level of the head of household was found to be a statistically significant predictor on whether a household will acquire a formal savings account (Kiiza & Pederson, 2001). Owing to the sufficiently low-income of many poor households in develop- ing countries, they tend to use informal savings mechanisms, which are less secure and safe than formal savings accounts (Collins et al., 2009). For example, in Pakistan, increases in income led to a higher rate of participation in both formal and informal savings sectors. However, at higher levels of income, formal institutions (such as banks) become more widely used than informal institutions (e.g. bisi, an informal savings com- mittee similar to a rotating-savings-and-credit-association) (Carpenter & Jensen, 2002). Further, the same study found that bank use was strongly influenced by literacy and numeracy, suggesting that access to and use of formal savings institutions could face severe constraints in countries with low educational attainment and literacy rates (Carpenter & Jensen, 2002). Institutional Perspective Institutional theory posits that individuals and households are faced with institutional-level factors that make it impossible or difficult to save. The main hypothesis of institutional theory assumes that low-income individuals and families are unable to save and accumulate assets primarily because they do not have the same institutional opportunities that higher-income indi- viduals and households receive (Beverly & Sherraden, 1999; Sherraden, 1991). Otherwise, given access to the same institu- tional support for saving and asset building that their wealthier counterparts use, low-income families can be in a position to save and accumulate assets. Institutions in the institutional the- ory refer to “purposefully-created policies, programs, products, and services that shape opportunities, constraints, and conse- quences” (Beverly et al., 2008: p. 10). Institutional theory hy- pothesizes that institutions affect worldviews, which in turn, affect financial behaviors and decisions (Beverly & Sherraden, 1999). Seven institutional-level dimensions have been hypothe- sized to influence saving and asset accumulation. These dimen- sions are access, information, incentives, facilitation, expecta- tions, restrictions, and security (Beverly & Sherraden, 1999; Beverly et al., 2008; Sherraden & Barr, 2005; Sherraden et al., 2003; Sherraden, Williams Shanks, McBride, & Ssewamala, 2004). This study focuses on the institutional factors (access, information, incentives and expectations) that have variations in the asset-building program used in the study. Evidence from SSA and other developing countries suggests that institutional factors are associated with saving and asset building. In Uganda, proximity of the financial institution to the household is associated with the probability of whether or not a household will open a formal saving account, as well as the level of net deposits among households owning a bank account (Kiiza & Pederson, 2001). In the same study, urban households were more likely to open a deposit account than their rural counterparts. Higher transaction costs (due to reduced accessi- bility) were also found to have significant negative effects on the level of savings deposits among Ugandan (Kiiza & Peder- son, 2001) and rural Kenyan households (Dupas & Robinson, 2009). Dupas and Robinson (2009) found that subsidizing the opening fees for a savings account on behalf of a random sam- ple of small business owners in rural Kenya increased the sav- ings of women, many of them market vendors who opened the account compared to women who were not offered the account. Also in Kenya, Kibet and colleagues (2009) found that higher transport costs to saving institutions had a negative impact on the saving habits of teachers in rural areas. These results sug- gest that poor people can be better off if it is much cheaper to start a bank account. In these circumstances, accumulation of savings and other assets is not solely based on individual char- acteristics and choices; some people have greater access than others, and this disparity in access is evident in many parts of the developing world. Aside from access, information, particularly general infor- mation about financial institutions and their products and ser- vices, was found to be associated with owning a bank account among households in SSA. In Uganda, researchers found that the likelihood of owning a savings account increases by roughly 33 times when a household becomes well informed about a particular bank and its services (Kiiza & Pederson, 2001). In the Philippines, restrictions (i.e. prohibitions or rules that restrict access to or use of savings or assets) attached to a commitment savings product helped low-income women save (Ashraf, Karlan, & Yin, 2006). However, the impact of other institutional-level factors on saving behaviors among low-in- come households in developing countries is not yet known due to lack of relevant data. This study aims to provide evidence on the impact of two other institutional-level factors: incentives and expectations on savings2. Methodology Data and Sample This paper studies participants of AssetsAfrica program in rural Uganda. AssetsAfrica is a demonstration and research 2Evidence from the United States and other industrialized countries sug- gests that other institutional constructs are associated with financial behav- iors and decisions. Information (or financial education), for instance, has een found to increase participation and contribution in savings plans (Bernheim & Garrett, 2003; Clancy, Grinstein-Weiss, & Schreiner, 2001; yce, 2005). Incentives, particularly in the form of matching contributions, have been found to increase savings (Duflo, Gale, Liebman, Orszag, & Saez 2006; Han & Sherraden, 2009) and participation in savings plan (Duflo, et al., 2006; Nyce, 2005). Research has also found that facilitation (i.e. assis- tance with participation and savings), whether in the form of precommit- ment constraints (Thaler & Benartzi, 2004), automatic enrollment (Madrian & Shea, 2001), or direct deposit (Han & Sherraden, 2009; Sherraden & McBride, 2010) shapes saving and asset accumulation. Evidence also sug- gests that expectations (i.e. implicit or explicit suggestions about desired saving; Han & Sherraden, 2009; Schreiner & Sherraden, 2007) and restric- tions (Sherraden & McBride, 2010) help individual and families increase their savings. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 283  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. initiative designed to test asset-building innovations in Africa. Implemented in Masindi, Uganda between 2004 and 2008, the Ugandan pilot project used a quasi-experimental design, com- paring across treatment and comparison villages. This design was chosen in part because of high risk of contamination across treatment and control subjects if randomly assigned in the same village. The AssetsAfrica study sample consisted of 400 indi- viduals assigned to the intervention group (n = 200) or the comparison group (n =200). Individuals in the intervention group were selected by village committees, (i.e., economically needy individuals in the community were chosen) and offered the opportunity to participate in the project. The intervention implemented in this project was a structured asset-building program offered to half of the study sample for a 3-year period. The intervention comprised a comprehensive program that included matched funds for participants’ savings, financial education, and training on how to manage the asset they planned to acquire with their savings. Treatment group partici- pants opened savings accounts in a commercial bank. Due to the absence of banks in the six intervention-site villages and the distance to the financial institution in the business district of Masindi, Stanbic bank (an international company that operates in 16 African countries) established a mobile bank that visited the villages every week to collect savings. Participants who wanted to complete their own banking transactions could either wait for the weekly mobile bank visit or travel to the bank in the Masindi business district. Deposits had to remain in the accounts for a minimum of 6 months before participants were eligible to receive matched funds. Restrictions were made for lump sum deposits to encourage more regular savings over the participation period. Participants who successfully reached their goals had their savings matched at a ratio of 1:1 after which each participant purchased their desired asset. To encourage sustainability and viability of the assets, only purchases of pro- ductive assets (i.e., those that would generate income) were eligible for matching funds. Data were collected by 12 locally trained interviewers who conducted face-to-face surveys. Questionnaires were adminis- tered twice (baseline and follow-up) over a 13-month interval. Because this study focuses on examining the extent to which different theories of saving explain saving in an asset-building program for low-income households, only participants in the treatment group were used for analysis (n = 200). Missing data on one or more explanatory variables reduced the sample to 127. Given the reduction of sample size, we analyzed the extent to which respondents (n = 127) and nonrespondents (n = 73) dif- fered. Bivariate analyses showed no significant differences (p > .05) between the two groups in all of the demographic and explanatory variables. Data Analysis Through the use of hierarchical multiple regressions (HMR), we assessed the degree to which savings among AssetsAfrica participants could be explained by demographic variables and three theoretical perspectives. HMR allows researchers to de- cide which order to use for a list of explanatory variables by putting the predictors or groups of predictors into blocks of variables. Unlike stepwise regression, the groups of predictors are based on theoretical grounds. Consistent with prior studies (Curley et al., 2009; Han & Sherraden, 2009), we entered the individual-oriented predictors first, followed by sociological predictors, and then the institutional-level predictors. Outcome Variab le The outcome variable in this study was similar to previous evaluations of asset-building programs: the average quarterly net saving (AQNS). We used AQNS to measure saving per- formance at the end of the program. AQNS is defined as net savings per quarter and is calculated by dividing net savings by the number of participation quarters (Schreiner et al., 2001). In this study, the number of participation quarters was 12. Explanatory Variabl e s In this study, we used key constructs of the saving theories discussed in the earlier sections. Aside from the explanatory variables, we also included three demographic variables: gender, marital status, and gender of youngest child. Gender is a di- chotomous variable, having 1 for female and 0 for male. Mari- tal status is also a dichotomous variable, having 1 for married and 0 for not married. Gender of youngest child is a dichoto- mous variable, having 1 for male and 0 for female. Using HMR, four models were estimated in the study. The first model we ran was based on the individual-oriented per- spectives. Controlling for demographic variables, we estimated the impact of explanatory variables based on economic and psychological theories of saving. Age and wealth were used as measures based on neoclassical economic theories. Wealth was used as a substitute for income. Measuring income was a chal- lenge in this study as most respondents were seasonal income earners who only earned income part of the year. As a result, respondents could not accurately recall how much income they earned in a year. Therefore, wealth was used as a substitute as it was easy to measure and could be verified on the spot. Wealth was measured using an index, which included the total value in USD of financial and productive assets reported by participants at baseline survey. Optimism/pessimism about future economic expectation, perceived locus of control, attitude toward saving, and self-control were used to examine how psychological fac- tors and common human characteristics were related to saving. Future economic expectation was measured using a 3-item, 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely worse) to 7 (ex- tremely better). Respondents were asked how well they ex- pected their life and food supply to be next year, in addition to how well they expected to be living next year. Perceived locus of control was also measured using a 3-item, 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Respondents were asked if they felt pretty sure that their lives would work out the way they wanted them to; if they usually performed tasks the way they expected to; and if they always finished doing something once they started it. Attitude toward saving was a dummy variable, with respondents choosing from 1 (agree) that saving takes too long or 0 (do not agree). Self-control was measured using a 1-item, 7-point likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Respondents were asked how often they were hesitant to spend money that they had saved. The second model based on the sociological perspective takes into account class and social stratification variables in addition to the control variables we added in the first model. We included four different predictors to measure the relation- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 284  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. ships between savings and class and social stratification. First, social support was measured using a 3-item, 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no help at all) to 7 (a lot of help). Re- spondents were asked how much help they get to meet the needs of the household from family and friends, from organiza- tions, and from the community. Second, economic strain was measured using a 1-item, 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely hard) to 7 (extremely easy). Respondents were asked how hard or easy it was to meet the needs of their household. Third, education was a dummy variable, with respondents choosing from 1 (secondary education or higher) or 0 (primary education or lower). The dummy education variable was cre- ated based on the frequency distribution of the original variable. And finally, type of employment was a dummy variable, with respondents choosing from 1 (formal employment) and 0 (oth- ers). The third model adds the three institutional theory constructs (access, information, and expectation) to assess the relationship between saving outcomes and institutional factors, after all the predictors in the previous models are taken into account. First, expectation was measured by the total amount of money re- spondents said they would like to save. Second, incentive was measured by the total amount of matching funds that each par- ticipant received at the end of the program. Third, information was measured by the total number of hours that participants spent in financial education. And fourth, access was divided into two sub-domains: ease of visiting financial institutions and ease of depositing money. Both explanatory variables were dummy variables. We created two groups for each access indi- cator: 1 for (easy ratings) and 0 for (hard ratings). In the fourth model, we included incentive as an institutional theory construct to assess the relationship between saving out- comes and financial incentives after all the predictors in the first three models were considered. Incentives were separated from the rest of institutional theory constructs to assess how much of the outcomes are explained by financial incentives when incentives are a key feature of the intervention. The deci- sion to separate incentives was also made because incentives might inflate the AQNS when included and might therefore provide a different picture of the effects on savings. Separating them provided a clearer picture for participants about the actual money being saved without regard to incentives. In HMR, a full model with all theoretical perspectives was compared to models without each block of perspective. Partial F-tests were conducted to determine to what extent each theo- retical perspective explained saving outcomes in an asset- building program. Results of the diagnostic tests and residual analyses showed that the outcome variable and three predictors were highly skewed and not normally distributed. To reduce the influence of extreme observations on regression coefficient estimates, we used two types of data transformation. We trans- formed AQNS and wealth using inverse hyperbolic sine trans- formation to handle observed zero values (Burbidge, Magee, & Robb, 1988). We transformed information (hours of financial education attended) and expectation (desired total amount of money in savings) variables using logarithmic transformation. Further, because the financial incentive variable violated the assumption of constant variance, we used weighted least squares regression in the final model to correct for the bias caused by heteroscedastic data (Kutner, Nachtsheim, & Neter, 2004). For each multi-item predictor, a composite score was calculated by taking the average score of all items. Results Descriptive Results A total of 127 individuals were included in the sample of this study. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the variables in the analysis. The median amount of savings per quarter among AssetsAfrica participants was US $60. The median for savings per quarter are reported because the variables for savings ex- pectations, wealth, number of financial education hours at- tended, and amount of matching funds received are skewed. More females (59.84%) than males (40.16%) are represented in the sample. The sample had more married individuals (79.53%) than unmarried individuals (20.47%). Participants’ youngest children included mostly girls (55.91%) compared to boys (44.09%). Study participants were, on average, was about 35 years old, while their median wealth was valued at US $372. Regarding self-control, 18.90% of participants reported that they were rarely to never hesitant to spend money that they had saved, whereas 30.71% and 50.4% of participants reported that they were sometimes and more than often hesitant to spend their savings. Sixty-four percent of participants agreed that saving takes too long. On average, participants expected that their economic conditions in the following year would be better than the current year. Further, participants, on average, tended to agree that they had control over their lives. On average, AssetsAfrica participants received some help from family, friends, organizations, and the community. Re- garding the ability to meet the needs of their household, 45.7% of the participants reported having some degree of difficulty meeting the needs of the household; 28.3% reported being in the middle, and 26% reported having an easier time meeting their households’ needs (25.98%). Fifty-four percent of the participants had at least a secondary education or higher, whereas 45.67% had a primary education or lower. A lower percentage (20.47%) of participants was formally employed. Regarding institutional features, the median amount of money participants said they wanted to save was US $300. The median number of financial education hours that AssetsAfrica participants attended was 5. A higher percentage (63.78%) of participants reported having a hard time visiting a financial institution. On the other hand, a lower percentage (33.86%) of participants reported having a hard time making deposits. The median matching funds that participants received was US $290. Bivariate tests were conducted to examine the association between AQNS and each explanatory variable. Table 1 shows results of bivariate analysis. Four of five institutional-level predictors were statistically significant (p < .10). However, this analysis only serves an exploratory purpose because it did not control for other explanatory variables. Hierarchical Mul tip l e Regression Anal ysis Table 2 presents results of the HMR analysis. Results indi- cate that a significant amount of variance in savings perform- ance in AssetsAfrica is explained by model 4 or the final model in which all explanatory variables are considered. All R2 values were statistically significant (p < .05). Two R2 increments were also statistically significant (p < .05), (i.e. when institutional theory variables are added in the models). The R2 in the final model indicates that 61% of the variance in an individual’s saving performance can be accounted for by the three theoreti- cal perspectives on saving and demographic characteristics. The Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 285  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. Table 1. Descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis results. Variables % or Ma (SD)AQNS Outcome variable Average quarterly net saving (AQNS) in 2008 US$ 60.00 - Individual-oriented perspective Age 34.91 (10.40).007 Wealth 372.00 .448*** Expectation of future economic condition 5.30 (0.75).254 Perceived locus of control 5.35 (1.08).041 Self-control 4.61 (1.61).216 Rarely to never hesitant to spend savings (%) 18.90 Sometimes hesitant to spend savings (%) 30.70 Often to always hesitant to spend savings (%) 50.40 Attitude toward saving (saving takes too long) (%) 63.78 Sociological perspective Social support 3.79 (1.51).073 Economic strain 3.62 (1.28).009 Education .084 Primary or lower (%) 45.67 Secondary or higher (%) 54.33 Type of employment .121 Formal employment (%) 20.47 Others (%) 79.53 Institutional perspective Savings expectation (in USD) 300.00 .158^ Ease of visiting bank .594^ Easy to visit bank (%) 36.22 Hard to visit bank (%) 63.78 Ease of making deposits −.088 Easy to make deposits (%) 66.14 Hard to make deposits (%) 33.86 Hours of financial education attended 5.00 .508* Financial incentive (match funds received, in USD) 290.00 .004*** Demographics Gender −.270 Female 59.84 Male 40.16 Marital status −.074 Married 79.53 Not married 20.47 Gender of youngest child .344 Male 44.09 Female 55.91 Number of subjects 127 aEach entry is percentage of AssetsAfrica participants in the categorical predictor variable or the mean of the continuous variable. Standard deviations are presented in parentheses. Median is presented for AQNS, wealth, expectations, financial education hours, and financial incentives. ^p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Table 2. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis on average quarterly net sav- ings. Explanatory variables Model 1Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Individual Age .022 .021 .010 .006 Future economic Expectation .364 .476^ .325 .287 Perceived locus of control −.124 −.075 −.095 −.063 Wealth .443*** .470*** .483*** .284*** Self-control .042 .048 −.032 −.011 Attitude toward saving (saving takes too long = 1) .028 −.048 −.324 −.151 Sociological Social support −.095 .004 −.042 Economic strain −.049 −.005 −.059 Education (secondary education or higher = 1) −.358 −.553 −.217 Employment status (formal = 1) .272 .095 .070 Institutional Expectation .144 .013 Ease of depositing (easy =1) −.360 .179 Ease of visiting bank (easy = 1) .598^ .467^ Number of hours of financial education attended .506* .381* Financial incentives (match funds) .003*** Demographics Gender (female = 1) −.205 −.268 −.096 −.228 Marital status (married = 1) −.142 −.189 −.213 −.113 Gender of youngest child (male = 1) .218 .225 .323 .339 F value 3.10** 2.22* 2.40** 9.34*** R2 .1926 .2031 .2722 .6089 Incremental R2 .0105 .0691* .3367*** ^p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, two-tailed test. greatest increase in variance occurred in the final model, which include a financial incentive variable. R2 increased from .2722 in Model 3 to .6089 in Model 4, or a statistically significant increase of .34. Results of each regression model are presented next. When individual-oriented perspective and demographic characteristics are held constant, a test of model fit suggests that there is a regression relation (p < .01) and at least one β is not equal to zero. Among the individual-level predictors, wealth is the only Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 286  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. explanatory variable that is statistically significant (p < .001). For instance, when other variables are held constant, and when wealth increases by 10%, AQNS is expected to increase by about 4%. Consistent with previous research, other individ- ual-oriented variables in the study are not statistically signifi- cant. Model 1 explains 19% of the variance in AQNS. Results of model 2 also showed that the model fits with the data and that there is a regression relation in the population (p < .05). Wealth remains statistically significant (p < .001). When other variables are held constant, and when wealth increases by 10%, AQNS is expected to increase by about 5%. In addition, future economic expectation showed a statistical trend (p < .10). In the study sample, when other variables are held constant, a one-unit increase in future economic expectation, (i.e., when individuals expect next year to be better than the current year), AQNS is expected to increase by 61%. This finding contradicts what economic psychologists have posited, which is that individuals are likely to save more when they expect their economic future to be worse. However, this finding is consistent with neoclassi- cal theory, which posits that when people have more disposable income, they tend to save more. How this translates to expecta- tions of more disposable income rather than actual disposable income requires more research. Further, results of model 2 showed no statistically significant sociological perspective predictors. This finding does not support results of previous studies in developing countries that have shown some socio- logical-oriented variables such as education and employment to be statistically significant predictors of savings. Model 2 ex- plains 20% of the variance in AQNS. However, the incremental R2 between model 2 and model 1 is not statistically significant, suggesting that explanatory variables related to class and social stratification may not be important to saving performance among low-income rural Ugandans who participated in Assets- Africa. Consistent with the first two models, an F test model fit showed that model 3 fit the data, and that there is also a regres- sion relation in the population (p < .01). Model 3 explains 27% of the variance in the outcome variable. The incremental R2 between models 3 and 2 is statistically significant (p < .05); suggesting the importance of information, access, and expecta- tion to the saving performance of low-income rural individuals who participated in AssetsAfrica. Wealth remains statistically significant (p < .001). When other variables are held constant, and when wealth increases by 10%, AQNS is expected to in- crease by 5%. Financial education and ease of visiting a bank (proximity) are also statistically significant. Holding other variables constant, for any 10% increase in the number of fi- nancial education hours attended, AQNS is expected to increase by about 5%. Further, holding other variables constant, the expected increase in AQNS from those individuals who found it hard to visit a bank to those who found it easy to visit a bank is about 82%. This finding showed a statistical trend (p < .10), the two other measures of institutional theory—expectation and ease of depositing—were not statistically significant. Results of the final model showed that the model fit with the data. Overall, all three theoretical perspectives and demo- graphic variables explain 61% of the variance in AQNS. The models also showed that there is a significant regression rela- tion in the population (p < .001). As stated earlier, the greatest variance occurred in the final model, resulting in a statistically significant incremental R2 of .34 between model 3 and 4 (p < .001). This finding suggests the importance of financial in- centive, which in the current study is provided through match- ing funds in the saving performance of low-income individuals in rural Uganda. In the final model, four explanatory variables were statistically significant. When other variables are held constant, and when wealth increases by 10%, AQNS is ex- pected to increase by about 3% (p < .001). This result is 1% to 2% lower than the estimated values from the three earlier mod- els. Similarly, when the number of financial education hours attended increases by 10%, AQNS is expected to increase by about 4%, holding other variables constant (p < .05). Further, the expected increase in AQNS from those individuals who found it hard to visit a bank to those who found it easy to visit a bank is about 60%, holding other variables constant (p < .10). Finally, for a one dollar increase in matching funds received, AQNS is expected to increase by about .3% (p < .001). Discussion Conventional wisdom dictates that saving is more difficult for low-income individuals and households than their wealthier counterparts. However, this study adds evidence that rural, low-income individuals in SSA can and do save, especially when given the opportunities. Further, results of this study pro- vide initial evidence about the factors affecting saving among low-income participants of an asset-building program in rural areas of Uganda. All three theoretical perspectives, albeit in varying degrees, explain variation in saving performance among rural, low-income households. The final model, which includes all three theoretical frameworks and demographics, accounted for the highest variance in AQNS. The statistically significant incremental R2 in models 3 and 4 suggests that in- stitutional theory of saving is important in predicting savings performance in an asset-building intervention for low-income, rural households. Further, the substantial increase in variance that occurred in the final model, which included amount of matching funds, suggests that financial incentives are important in encouraging low-income individuals to save. The strong explanatory power of institutional theory in pre- dicting saving outcomes among participants of AssetsAfrica is not surprising. Institutional theory of saving has been devel- oped with the objective of increasing our knowledge of how individuals, especially the poor, can save (Sherraden, 1991). Although institutional theory emerged primarily from asset- building research in the United States, results of the current study suggest that institutional theory can also explain substan- tially the factors affecting saving performance among rural low-income individuals in SSA. In other words, consistent with results from studies conducted in the United States, institutional factors, such as information, access, and incentives, influence saving behaviors of rural, low-income individuals in Uganda. Thus, saving outcomes among the poor are not solely attributed to individual characteristics and choices. In AssetsAfrica, all participants were required to take financial education, primarily because the intervention was a package that included access, incentives, and information through financial education. A Chemonics International report (2007) cited limited financial information and lack of financial education as the two most common barriers to increasing savings rates in rural Uganda. In this study, results suggest that financial education (one method of providing financial information) is positively associated with higher savings. In other words, offering financial education to low-income individuals in developing countries can lead to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 287  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. positive outcomes, as research on financial behaviors among low-income individuals in the United States have shown (Hirad & Zorn, 2002; Lusardi, 2002). Further, the current study sug- gests that access (or proximity to financial institutions) is also influential in encouraging low-income individuals to save. Dis- tance remains a major barrier to formal financial services and other markets in rural areas in SSA. In rural Uganda, only 10% of the population has access to basic financial services (Chemonics International, 2007). Although 80% of rural Ugandans were active savers, only 13% of those active savers had a savings account in a formal financial institution (Che- monics International, 2007). Even though financial institutions may exist, transaction costs in reaching them can make them unavailable. These transaction costs typically refer to time, effort, and money spent to reach a bank. This finding supports previous findings about the positive association between prox- imity to financial institutions and higher savings in SSA (Kibet et al., 2009; Kiiza & Pederson, 2001). However, unlike prior studies, the current study provides initial evidence that prox- imity to financial institutions also influences positive saving behaviors of low-income individuals in rural SSA. Further, the positive association between proximity and saving suggests that there can be benefits to both financial providers and users when financial services are not only expanded but are easy to access, particularly in rural areas. Finally, financial incentives in the form of matching funds increased AQNS, albeit not as much as expected, among AssetAfrica participants. Schreiner and Sher- raden (2007) argued that matches in asset-building programs may encourage low-income people to save for at least three reasons: 1) matches increase the reward to saving and may help compensate for the sacrifice required to defer consumption; 2) matches may motivate people by translating a given level of saving into a stock of wealth that is large enough to use for a major asset; and 3) matches may be the program feature that catches the participant’s attention and motivates him or her to participate in the first place. The use of matching funds in As- setsAfrica is perhaps the first of its kind in rural SSA. The posi- tive relationship between the matching funds and saving out- come indicates that low-income individuals will respond posi- tively when given the opportunity to save and save more. This finding is identical to other studies in the United States that investigated the role of matching funds on the savings per- formance of low-income individuals (Duflo et al., 2006)The benefits of matching funds to AssetsAfrica participants go be- yond encouraging them to save; individuals are rewarded for saving more. Higher savings mean that low-income individuals and households are better prepared to weather income shocks and other emergencies. Savings are particularly important to families living in developing economies, like Uganda, because formal social safety nets that families in more developed economies can rely on to buffer against emergencies are not widely available. Although saving performance in AssetsAfrica is influenced primarily by institutional factors, wealth is positively associated with savings performance. In all four models, wealth is a statis- tically significant predictor, which suggests that wealth has a strong power in explaining saving among low-income indi- viduals in the AssetsAfrica program. The current study supports the findings of previous studies, albeit mostly on higher income individuals, in developing economies. A majority of studies on saving behaviors in developing economies have included only income in their analyses for various reasons. However, income does not necessarily provide a reliable measure of well-being because many people in developing countries, especially in rural areas, engage in informal labor markets where incomes are often highly variable and can be seasonal. Wealth provides a better and more stable picture of long-term living standards than an income snapshot because wealth or assets are what individuals and households accumulate over time and what last longer. In the final model, other than wealth, no other individ- ual-oriented variables were found to be a statistically significant predictor of saving. These findings are consistent with results of prior studies that found no or weak statistical relationship be- tween individual-oriented (economic and psychological) factors and savings outcome in both developed and developing econo- mies. Further, when sociological variables were added, results showed a statistically nonsignificant incremental R2. This find- ing indicates that the four sociological constructs (education, employment, level of social support, and degree of economic strain) in the study have a weak association in explaining sav- ing among rural, low-income individuals in AssetsAfrica. In other words, results suggest that class and social stratification are less important than wealth and institutional factors to an individual’s saving performance. These findings contradict what other researchers have found. These divergent findings may be attributed to the following: 1) observed savings deter- minants from a quasi-experimental setting that intentionally provides an opportunity to save might be quite different than those observed from national, aggregated data sets; 2) the sam- ple in the current study was primarily rural, low-income indi- viduals, whereas the samples in prior studies included a more representative sample of the general population; and 3) meas- urement-related limitations might have confounded the find- ings. For instance, economic strain is measured by only one question. Limitations and Conclusion There are several limitations to this study. First, participants in AssetsAfrica are not a representative sample of the overall low-income population in Uganda and SSA. Selection bias, particularly self-selection, limits the generalizability of the results. Second, this study examines saving performance only in the account provided by the program. Thus, we cannot say whether this is new savings or whether they have saved in other ways that were not reported in the study. Third, although we used relevant measures of each theory, this study cannot con- firm the validity of each theory especially when tested in a different geographic and socioeconomic population. Results may be an artifact of weak measures of key constructs of the saving theories. Future studies should employ, among other things, a wider range of key measures and more reliable scales to measure important constructs. Fourth, the study’s model specifications may have omitted important predictors. Omission of important predictors may lead to different results. Similarly, the functional form between the outcome and predictors might not have been specified correctly. For most of the variables, a linear relationship with the saving outcome was assumed. Fu- ture studies should also test for interaction effects among con- structs of interest. For instance, it could be that expectations of total savings amount are not predictive in themselves, but the interaction with financial incentives or access might have an effect. Fifth, the study has a small sample size relative to the number of explanatory variables included in the analyses. Thus, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 288  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. the study findings may have been biased because of the rela- tively small sample size. Despite the limitations, some of the findings are statistically and substantively significant. Results provide initial evidence on the factors that affect saving by rural, low-income individu- als. Controlling for other theoretical perspectives, the institu- tional theory of saving has independent and significant ex- planatory power in saving outcomes. Unlike the institutional theory of saving, which emerged from studies of saving behav- iors of low-income individuals and households, individual- oriented and sociological perspectives were not developed to explain saving by low-income populations. Findings also sug- gest that institutional structures of saving matter to low-income individuals in rural Uganda. Given access to the same institu- tional support for saving and asset building that their wealthier counterparts use, low-income individuals can be in a position to save and accumulate assets. Unlike the other theoretical per- spectives that may have limited practical implications, institu- tional theory of saving can directly inform future programs and policies designed to promote financial inclusion and help low-income individuals and families save and build assets. Acknowledgements Support for AssetsAfrica comes from the Ford Foundation. The authors thank Grace Kemirembe for her valuable assistance in AssetsAfrica, and Susan White for her careful review and insightful comments on the manuscript. REFERENCES Abdelkhalek, T., Arestoff, F., de Freitas, N. E. M., & Mage, S. (2009). A microeconometric analysis of households saving determinants in Morocco. The 1st GDRI DREEM Conference, Istanbul, 21-23 May 2009. Agrawal, P., Sahoo, P., & Dash, R. K. (2007). Savings behavior in India: Co-integration and causality evidence. The Singapore Eco- nomic Review, 55, 273-295. doi:10.1142/S0217590810003717 Ainsle, G. (1975). Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsive- ness and impulse control. Psychological Bulletin, 82, 463-496. doi:10.1037/h0076860 Al-Awad, M., & Elhiraika, A. (2003). Cultural effects and savings: Evidence from immigrants to the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Development Studies, 39, 139-151. doi:10.1080/00220380412331333179 Ameriks, J., Caplin, A., Leahy, J., & Tyler, T. (2004). Measuring self- control. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Ang, J. (2009). Household saving behavior in an extended life cycle model: A comparative study of China and India. Journal of Devel- opment Studies, 45, 1344-1359. doi:10.1080/00220380902935840 Angeletos, G. M., Laibson, D., Repetto, A., Tobacman, J., & Weinberg, S. (2001). The hyperbolic buffer stock model: Calibration, simulation, and empirical evaluation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15, 47- 68. doi:10.1257/jep.15.3.47 Ashraf, N., Karlan, D., & Yin, W. (2006). Tying odysseus to the mast: Evidence from a commitment savings product in the Philippines. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 635-672. doi:10.1162/qjec.2006.121.2.635 Athukorala, P., & Sen, K. (2004). The determinants of private saving in India. World Development, 32, 491-503. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.07.008 Attanasio, O. P., & Banks, K. (2001). The assessment: Household sav- ing—Issues in theory and policy. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 17, 1-19. doi:10.1093/oxrep/17.1.1 Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Peria, M. S. (2008). Banking services for everyone? Barriers to bank access and use around the world. World Bank Economic Review, 22, 397-430. doi:10.1093/wber/lhn020 Bernheim, B. D., & Garrett, D. M. (2003). The effects of financial education in the workplace: Evidence from a survey of households. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1487-1519. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00184-0 Bersales, L. G. S., & Mapa, D. S. (2006). Patterns and determinants of household saving in the Philippines (EMERGE Technical Report). Makati City: EMERGE. Beverly, S., & Sherraden, M. (1999). Institutional determinants of saving: Implications for low-income households and public policy. Journal of Socio-Ec o n om i c s, 28, 457-473. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(99)00046-3 Beverly, S., Sherraden, M., Cramer, R., Williams Shanks, T., Nam, Y., & Zhan, M. (2008). Determinants of asset holdings. In S. M. McKer- nan, & M. Sherraden (Eds.), Asset building and low-income families (pp. 89-152).Washington DC: Urban Institute Press. Burbidge, J. B., Magee, L., & Robb, A. L. (1988). Alternative trans- formations to handle extreme values of the dependent variable. Jour- nal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 123-127. doi:10.1080/01621459.1988.10478575 Carpenter, S. B., & Jensen, R. T. (2002). Household participation in formal and informal savings mechanisms: Evidence from Pakistan. Review of Development Economics, 6, 314-328. doi:10.1111/1467-9361.00157 Caskey, J. P. (1997). Beyond cash-and-carry: Financial savings, finan- cial services, and low-income households in two communities. Swarthmore, PA: Swarthmore College. Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (2010). Financial access 2010 report. Washington DC: CGAP. Chemonics International (2007). Improving access to financial services in rural Uganda: Rural SPEED final report. Washington DC: Chemonics. Chiteji, N. S., & Hamilton, D. (2005). Family matters: Kin networks and asset accumulation. In M. Sherraden (Ed.), Inclusion in the American dream: Assets, poverty, and public policy (pp. 87-111). New York: Oxford University Press. Chiteji, N. S., & Stafford, F. P. (1999). Portfolio choices of parents and their children as young adults: Asset accumulation by African- American families. American Eco no m i c Review, 98, 377-380. doi:10.1257/aer.89.2.377 Chowa, G. A. N. (2008). The impacts of an asset-building intervention on rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa (Doctoral Dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database (UMI No. 3332075). Chowa, G. A. N., Ansong, D., & Masa, R. (2010). Assets and child well-being in developing countries: A research review. Children & Youth Services Review, 32, 1508-1519. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.015 Chowa, G. A., Masa, R. D., & Sherraden, M. (2012). Wealth effects of an asset-building intervention among rural households in Sub-Saha- ran Africa. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 3, 329-345. doi:10.5243/jsswr.2012.20 Clancy, M., Grinstein-Weiss, M., & Schreiner, M. (2001). Financial education and savings outcomes in Individual Development Accounts. St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Develop- ment. Cohen, S. (1994). Consumer socialization: Children’s saving and spending. Childhood Education, 70, 244-246. Collins, D., Morduch, J., Rutherford, S., & Ruthven, O. (2009). Portfo- lios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Cornia, G., & Jerger, G. (1982). Rural vs. urban saving behavior: Evi- dence from an ILO collection of household surveys. Development and Change, 13, 123-157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1982.tb00115.x Crompton, R. (2008). Class and stratification. Malden, MA: Polity Press. Curley, J., Ssewamala, F., & Sherraden, M. (2009). Institutions and savings in low-income households. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 36, 9-32. D’Souza, V. S. (1981). Inequality and its perpetuation: A theory of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 289  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. social stratification. New Delhi: Manohar. Deaton, A. (1992). Household saving in LDCs: Credit markets, insur- ance and welfare. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 94, 253-273. doi:10.2307/3440451 Deaton, A., & Paxson, C. (2000). Growth and saving among individu- als and households. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 82, 212-225. doi:10.1162/003465300558740 Duflo, E., Gale, W., Liebman, J., Orszag, P., & Saez, E. (2006). Saving incentives for low- and middle-income families: Evidence from a field experiment with H&R Block. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 1311-1346. doi:10.1162/qjec.121.4.1311 Dupas, P., & Robinson, J. (2009). Savings constraints and microenter- prise development: Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya (NBER Working Paper No. 14693). Cambridge, MA: National Bu- reau of Economic Research. Erulkar, A., & Chong, E. (2005). Evaluation of a savings and micro- credit program for vulnerable young women in Nairobi. Nairobi: Population Council. Fafchamps, M., Udry, C., & Czukas, K. (1998). Drought and saving in West Africa: Are livestock a buffer stock? Journal of Development Economics, 55, 273-305. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(98)00037-6 Fisher, I. (1930). The theory of interest. London: Macmillan. Friedman, M. (1957). A theory of the consumption function. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Furnham, A. (1985). Why do people save? Attitudes to, and habits of saving money in Britain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 15, 354-373. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1985.tb00912.x Kibet, L. K., Mutai, B. K., Ouma, D. E., Ouma, S. A., & Owuor, G. (2009). Determinants of household saving: Case study of smallholder farmers, entrepreneurs and teachers in rural areas of Kenya. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 1, 137-143. Kiiza, B., & Pederson, G. (2002). Household financial savings mobili- zation: Empirical evidence from Uganda. Journal of African Econo- mies, 10, 390-409. doi:10.1093/jae/10.4.390 Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Neter, J. (2004). Applied linear regression models (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. Han, C. K., & Sherraden, M. (2009). Do institutions really matter for saving among low-income households? A comparative approach. Journal of Socio-Ec o n om i c s, 38, 475-483. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2008.07.002 Heflin, C., & Patillo, M. (2002). Kin effects on Black-White account and home ownership. Sociological Inq ui r y , 72, 269-292. doi:10.1111/1475-682X.00014 Hirad, A., & Zorn, P. M. (2002). Prepurchase homeownership counsel- ing: A little knowledge is a good thing. In N. P. Retsinas, & E. S. Belsky (Eds.), Low-income homeownership: Examining the unexam- ined goal (pp. 146-174). Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Hoddinott, J. (2006). Shocks and their consequences across and within households in rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Development Studies, 42, 301-321. doi:10.1080/00220380500405501 Jevons, W. S. (1965). The theory of political econom y (5th ed.). London: Macmillan. Johansson, S. (1998). Life cycles, oil cycles, or financial reforms? The growth in private savings rates in Indonesia. World Development, 26, 111-124. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10011-0 Katona, G. (1975). Psychological economics. New York: Elsevier. Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 443-477. doi:10.1162/003355397555253 Lerman, R. I., & McKernan, S. M. (2009). Benefits and consequences of holding assets. In S. M. McKernan, & M. Sherraden (Eds.), Asset building and low-income families (pp. 175-206). Washington DC: Urban Institute Press. Lindqvist, A. (1981). A note on determinants of household saving be- havior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 1, 37-59. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(81)90004-0 Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (1991). Psychological, social and economic determinants of saving: Comparing recurrent and total savings. Journal of Economic Psychology, 12, 621-641. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(91)90003-C Lusardi, A. (2002). Preparing for retirement: The importance of plan- ning costs. National Tax Association Proceedings (pp: 148-154). Washington DC: National Tax Association. Madrian, B., & Shea, D. (2000). The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1149-1187. doi:10.1162/003355301753265543 Marshall, A. (1961). Principles of economics: An introductory volume (9th ed.). London: Macmillan. Mason, A. (1987). National saving rates and population growth: A new model and new evidence, In D. G. Johnson, & R. D. Lee (Eds.), Population growth and economic development: Issues and evidence (pp. 523-560). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. Mason, A. (1988). Saving, economic growth, and demographic change. Population and Development Review, 14, 113-144. doi:10.2307/1972502 Modigliani, F., & Ando, A. K. (1957). Tests of the life cycle hypothesis of savings. Bulletin o f the Oxford Institute of Statistics, 19, 99-124. Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H. et al. (2010). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 2693-2698. Mullainathan, S., & Thaler, R. (2000). Behavioral economics. Cam- bridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Nyce, S. A. (2005). The importance of financial communication for participation rates and contribution levels in 401(k) plans. Philadel- phia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School, Pension Re- search Council. Ölander, F., & Seipel, C. M. (1970). Psychological approaches to the study of saving (Studies in Consumer Savings No. 7). Urbana- Champaign, IL: Bureau of Economic and Business Research, Uni- versity of Illinois. Oliver, M., & Shapiro, T. (1995). Black wealth/white wealth: A new perspective on racial inequality. New York: Routledge. Perry, V. G., & Morris, M. D. (2005). Who is in control? The role of self-perception, knowledge, and income in explaining consumer fi- nancial behavior. The Journal of C onsumer Affairs, 39, 299-313. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00016.x Romal, J. B., & Kaplan, B. J. (1995). Differences in self-control among spenders and savers. Psychology: A Journal of Human Behavior, 37, 8-17. Rosenzweig, M. R. (2001). Savings behavior in low-income countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 17, 40-54. doi:10.1093/oxrep/17.1.40 Schmidt-Hebbel, K., Webb, S. B., & Corsetti, G. (1992). Household saving in developing countries: First cross-country evidence. The World Bank Economic Review, 6, 529-547. doi:10.1093/wber/6.3.529 Schreiner, M., & Sherraden, M. (2007). Can the poor save? Saving and asset building in Individual Development Accounts. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. Schreiner, M., Sherraden, M., Clancy, M., Johnson, L., Curley, J., Grinstein-Weiss, M. et al. (2001). Savings and asset accumulation in individual development accounts (CSD Report 01-23). St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Development. Shapiro, T. (2004). The hidden cost of being African American: How wealth perpetuates inequality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Shefrin, H., & Thaler, R. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26, 609-643. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1988.tb01520.x Sherraden, M. (1991). Assets and the poor: A new American welfare policy. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Sherraden, M., & Barr, M. (2005). Institutions and inclusion in saving policy. In N. Retsinas & E. Belsky (Eds.), Building assets, building credit: Creating wealth in low-income communities (pp. 286-315). Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Sherraden, M., Schreiner, M., & Beverly, S. (2003). Income, institu- tions, and saving performance in individual development accounts. Economic Development Quarterly, 17, 95-112. doi:10.1177/0891242402239200 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 290  G. A. N. CHOWA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 291 Sherraden, M. S., & McBride, A. M. (2010). Striving to save: Creating policies for financial security of low-income families. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Sherraden, M. S., Williams Shanks, T., McBride, A. M., & Ssewamala, F. (2004). Overcoming poverty: Supported saving as a household development strategy (CSD Working Paper 04-13). St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Development. Sørensen, A. (2000). Toward a sounder basis for class analysis. Ameri- can Journal of Sociology, 105, 1523-1558. doi:10.1086/210463 Ssewamala, F. M., & Ismayilova, L. (2009). Integrating children sav- ings accounts in the care and support of orphaned adolescents in rural Uganda. Social Service Review, 83, 453-472. doi:10.1086/605941 Stack, C. (1974). All our kin: Strategies for survival in a black commu- nity. New York: Harper and Row. Thaler, R. H. (1981). Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsis- tency. Economic Letters, 8, 201-207. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(81)90067-7 Thaler, R. H. (1994). Psychology and savings policies. American Eco- nomic Review, 84, 186-192. Thaler, R. H, & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow: Using be- havioral economics to increase employee saving. Journal of Political Economy, 112, 164-187. doi:10.1086/380085 Thaler, R. H., & Shefrin, H. M. (1981). An economic theory of self- control. Journal of Political Econo my, 89, 392-401. doi:10.1086/260971 ur Rehman, H., Bashir, F., & Faridi, M. Z. (2011). Saving behavior among different income groups in Pakistan: A micro study. Interna- tional Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1, 268-277. Wärneryd, K. E. (1999). The psychology of saving: A study on eco- nomic psychology. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. Weber, M. (1967). Class, status and party. In R. Bendix, & S. M. Lipset (Eds.), Class, status, and power: Social stratification in comparative perspective (pp. 21-28). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Webley, P., & Nyhus, E. (2006). Parents’ influence on children’s future orientation and saving. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 140- 164. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2005.06.016 Williams Shanks, T. R., Kim, Y., Loke, V., & Destin M. (2010). Assets and child well-being in developed countries. Children & Youth Ser- vices Review, 32, 1488-1496. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.011

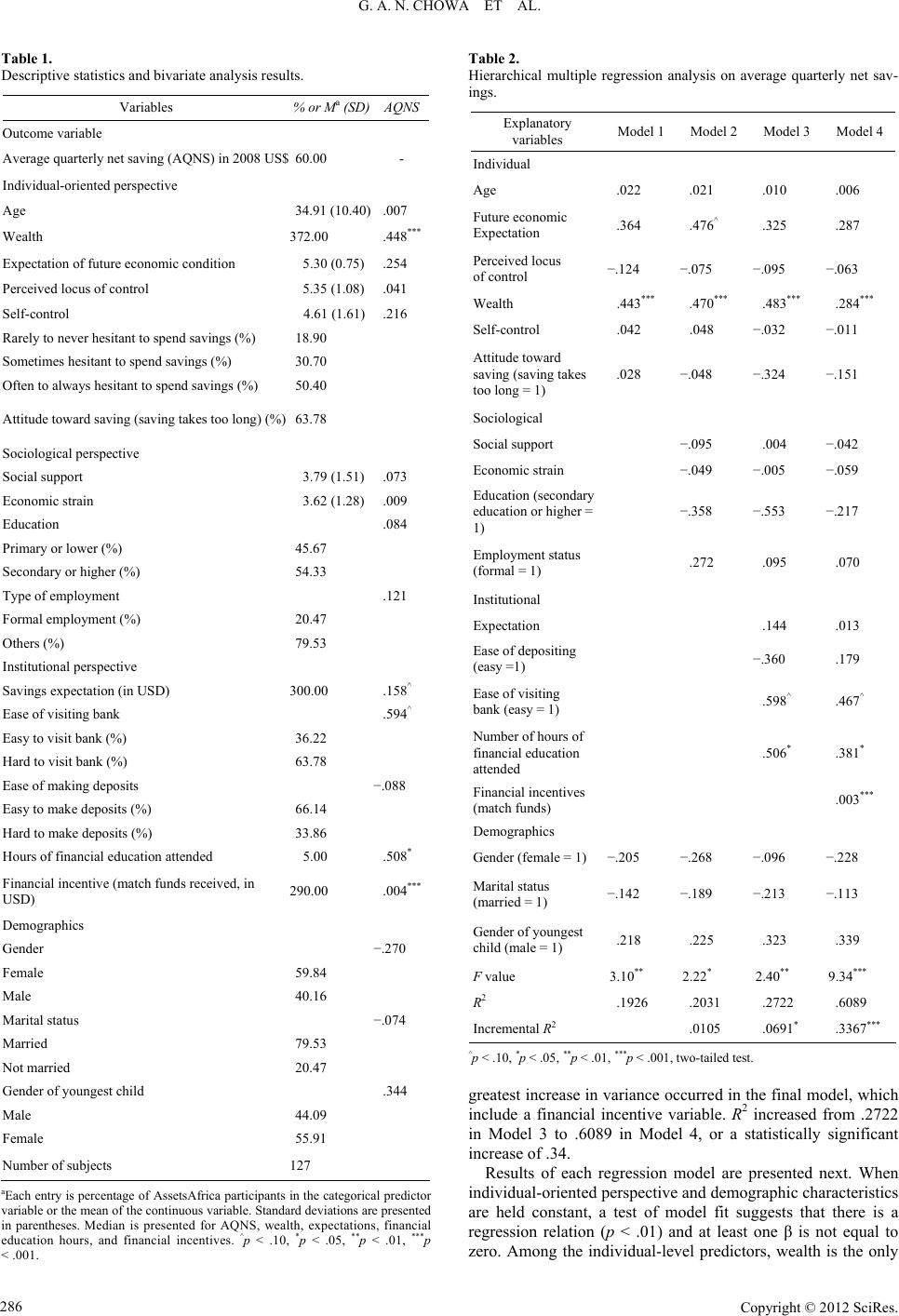

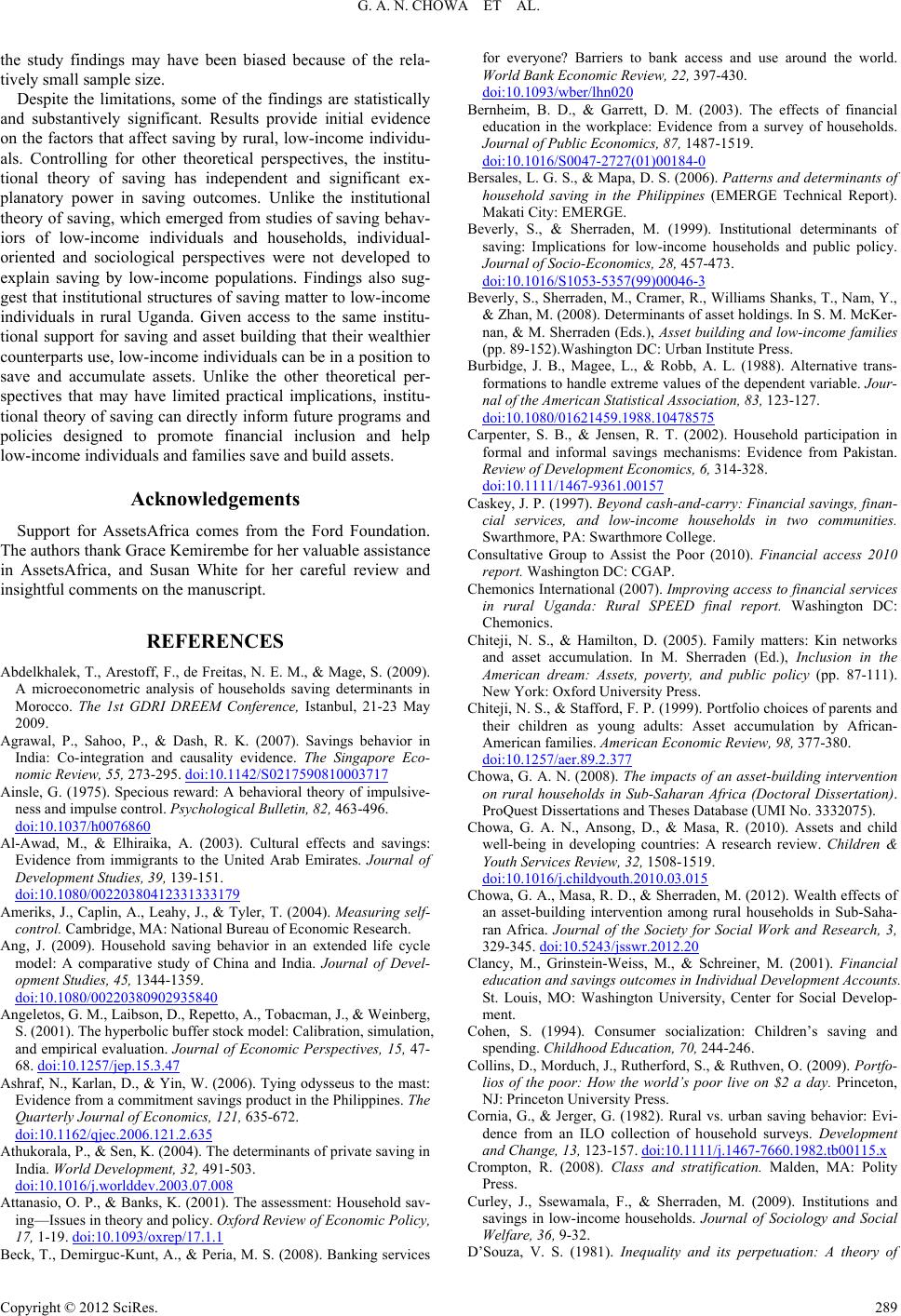

|