Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.12, 1049-1058 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312156 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1049 Resolution Process of Therapeutic Alliance Ruptures: A Review of the Literature Pierre Baillargeon1, Robert Coté2, Lyne Douville1 1Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, Canada 2Université de Laval, Québec, Canada Email: pierre.baillargeon@uqtr.ca, Robert.Cote@ulaval.ca, lyne.douville@uqtr.ca Received September 18th, 2012; revised October 20th, 2012; accepted November 17th, 2012 Adolescents living in youth centers often comply with therapeutic treatment against their will. We think that this forced environment ruptures the therapeutic alliance between adolescents and their therapists and, as such, influences the therapeutic results. It has been reported, however, that therapies evoking rupture of the alliance with its later restoration are more effective than therapies without rupture. We review the lit- erature on models of therapeutic alliance rupture resolution. This review is limited to experimentally- tested models. Firstly, we define the concepts of therapeutic alliance and its rupture. Then, we explore experimental models that quantify therapeutic alliance rupture resolution, describing methods of experi- mental validation, the results of models applied for experimental validation, and analysis of the data thus obtained. Keywords: Therapeutic Alliance; Rupture, Resolving; Literature Review; Psychotherapy Introduction Adolescents in youth centers often submit to treatment against their will. Pauzé, Toupin, Déry and Mercier (2000) and Lessard (2001) report that a large number of adolescents in youth centers were placed there in accordance with the Young Offenders Act or the Youth Protection Act. Lessard (2001) specifies that in 1999-2000, 48.2% of referrals were finalized by a judge. Le Blanc, Girard, Kaspi, Lanctôt and Langelier (1995) note that in the Jesness Personality Inventory, adoles- cents under judicial control have a tendency to be mistrustful and withdrawn in their interactions with others, particularly authority figures. This context may influence the quality of the therapeutic alliance between youths and their caseworkers, and thus affect the results of the intervention. Yet, quality therapeutic alliances are associated with a wide range of positive results. Researchers like Horvath and Sy- monds (1991), Martin, Garske and Davis (2000) and Orlinsky, Grawe and Parks (1994), for example, arrive at this conclusion. These researchers evaluated the short- and long-term effects of psychodynamic, cognitive and experimental therapies with clients whose problems varied. Florsheim, Shotorbani, Guest- Warnick, Barratt and Hwang (2000), on their part, suggest that young delinquents who develop and maintain a positive thera- peutic alliance with their caseworkers show considerable im- provement during treatment and less recidivism in the year following treatment. Ruptures in the therapeutic alliance between youths and their caseworkers seem inevitable in youth center contexts. However, some authors, for example Safran, Crocker, McMain and Murray (1990), argue that therapies that include alliance ruptures appear to be more effective than those without ruptures, on condition, however, that the alliance is restored. This article reviews experimental models of the resolution process of therapeutic alliance ruptures. Experimental models of the resolution process are interesting because they are likely to propose ways of resolving alliance ruptures to caseworkers. Applying one resolution process model would make interven- tions more specific and thus increase its effectiveness. First, we want to remind psychosocial workers of the concepts of thera- peutic alliance and of therapeutic alliance rupture. Next, we will focus on experimental models of alliance rupture resolution, describing experimental investigation methods, the results of experimental investigation of these models, and analysis of the data. The Therapeutic Alliance Concept The therapeutic alliance concept, which has been the subject of research over the past few decades, specifies the importance of the relationship in successful therapy. The first theoretical and experimental studies on the therapeutic alliance originate primarily from psychodynamic approaches (Luborsky, 1976; Zetzel, 1956) and are client-centred (Rogers, 1957; Barrett- Lennard, 1962, 1978, 1986). The more recent investigations stem from cognitive and systemic approaches (Pinsof, 1995; Safran & Muran, 2000). In these studies, there is increasing recognition of the role of the alliance in the effectiveness of therapy. Furthermore, pharmacotherapy considers the alliance as a factor that influences collaboration and, consequently, the results of therapy (Docherty, 1989). Although heterogeneous in terms of change mechanisms, these studies help conceive the importance of the alliance in the change process. Recognition of the importance of the patient therapist alli- ance dates back to Freud. In his first papers, Freud (1913, 1966) proposed that therapists establish a bond with their patients at the outset of the therapeutic relationship. According to Freud, the patient must be allowed time for this bond to be established. If the therapist shows great interest in the patient, eliminates resistances and avoids certain mistakes, the patient will form an  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. attachment to him. This attachment will resemble the one that he has already established with people who have paid attention to him. Freud adds that an intervention can start off badly if, during the first sessions, the therapist does not receive the pa- tient’s point of view with sympathetic understanding. In line with Freud’s ideas, authors like Greenson (1965, 1967), Sterba (1934) and Zetzel (1956) pursued studies on the impact of the patient-therapist alliance on the success of an intervention. Sterba (1934) introduced the ego alliance concept in which he refers to the need for a positive relationship be- tween the patient’s reasonable ego and the therapist’s analyzing ego. The author stresses the importance of the patient’s ability to work towards the success of the intervention. Zetzel (1956) introduced the therapeutic alliance concept, which she believes comprises the patient’s positive relationship and identification with the therapist. She sees the therapeutic alliance as a repetition of the parent-child relationship. Zetzel does not define this concept any further, but sees it as an im- portant element in the success of an intervention. Inspired by Sterba and Zetzel, Greenson (1965, 1967) intro- duced the concept of working alliance, which he uses as a synonym of the therapeutic alliance. Greenson sees the alliance as a positive relationship between patient and therapist and as the patient’s ability to work towards the success of the inter- vention. In addition to acknowledging the patient’s contribution to the alliance, Freud (1913, 1966) advanced that the therapist plays a major role in the establishment of an alliance. Rogers (1957) pursued Freud’s idea of a patient-centred approach. One of the central concepts of the Rogerian approach is formulated as follows: the relationship offered by the therapist is a necessary condition that is sufficient to help patients resolve their prob- lems. Rogers (1957) and Barrett-Lennard (1962, 1978, 1986) presented the conditions involved in a patient-therapist alliance. They proposed the following hypothesis: empathy, congruence and unconditional acceptance from the therapist suffice for the patient to improve. However, authors like Gelso and Carter (1985) and Mitchell, Bozart and Krauft (1977) believe that the conditions described by Rogers and Barrett-Lennard are not sufficient to ensure the success of an intervention. Other authors affirm that the concept of the alliance is neither valid nor useful (Brenner, 1979) or that it can be misleading (Curtis, 1979). Brenner (1979) argues that there is no alliance phenomenon. The patient’s relationship with the therapist is a phenomenon of transference that must be treated as resistance. The patient’s desire to work within treatment can be viewed as a desire to win the approval of a parental figure or to compete with the therapist for his perspicacity. Such transference deter- minants of the patient’s engagement and collaboration in treat- ment are considered difficult to distinguish from non-conflict- ual determinants of the alliance. Curtis (1979) believes that the alliance concept represents a danger of moving away from the analytical concepts of unconscious intrapsychic conflicts, of free association and the interpretation of transfer and resistance. Another controversy pertains to divergent concepts of the al- liance. They can be illustrated by the variability in definitions of the alliance. For example, Luborsky (1976) and Zetzel (1956) described the alliance as the patient’s bond with the therapist and the therapist’s helpfulness as perceived by the patient. However, Frieswyk, Allen, Colson et al. (1986) define the alli- ance as the patient’s active collaboration in treatment tasks. Both definitions of the patient’s collaboration in psychotherapy can be conceived as distinct, but relatively dependent, dimen- sions. The alliance includes the affective aspects of the patient’s collaboration in therapy that are aimed at the therapist’s person and reflect the more skillful aspects of the patient’s collabora- tion that are directed towards treatment tasks. Definition of the Therapeutic Alliance Bordin (1979) proposes the most recognized concept of the alliance. According to Bordin, the 3 main dimensions of con- tent of the therapeutic alliance are tasks, goals and the bond. Pinsof (1995) describes and illustrates each of these dimensions. The task dimension pertains to the activities or main tasks in which the patient and therapist engage during the intervention. Specifically, it refers to the extent to which a patient believes that the tasks meet his expectations and how comfortable he finds them. If the patient expects to have a conversation with the therapist and the therapist rarely speaks, the therapist’s be- haviour does not live up to the patient’s expectations of the intervention. The patient expects a dialogue while the therapist expects the patient to speak with a minimum of feedback on his part. In this situation, the task components of the alliance will be relatively weak. Comfort in the task dimension refers to the degree of well-being or anxiety that the patient experiences relative to the tasks. For example, the therapist can strongly encourage Louise, a 17-year-old woman hospitalized after a suicide attempt, to tell her elder brothers and sisters and her parents that she was sexually abused by her uncle from the ages of 10 to 14 years. If Louise is too afraid to perform this task, she will be in conflict. The therapist’s expectations exceed her comfort threshold. Even if Louise thinks that confiding in her brothers, sisters and parents is a good idea, and even if her ex- pectations for the tasks are congruent with those of the therapist, emotionally, the task may prove beyond her strength at that time. If the therapist insists that she perform this task, the task component of the alliance will be seriously compromised. The second major dimension of the alliance, the goals, refers to the extent to which the patient experiences a therapist who works with him on the problems for which he requests help: “Is the therapist trying to help him attain his goals?” or “Is the therapist pursuing goals that do not interest him?” For example, parents with marital problems seek help for their son’s depres- sion. Since their goal does not consist in improving their mar- riage, prematurely targeting their marital problems would greatly weaken their alliance and compromise the intervention. The last dimension of the alliance, the bond, refers to the af- fective quality of the alliance and includes aspects of the pa- tient-therapist relationship, such as trust, concern and engage- ment. The bond dimension covers the extent to which the therapist becomes a significant person and an emotionally- charged object for the patient and to which the patient feels that the therapist is committed to and concerned about him. The bond is, therefore, the patient’s emotional response to the therapist and his effects. The 3 work alliance dimensions are interdependent. Conse- quently, the quality of the relationship mediates the patient’s and therapist’s ability to negotiate an agreement regarding the intervention tasks and goals. The patient’s ability to negotiate such an agreement also mediates the quality of the bond be- tween them. Predictive Validity of the Therapeutic Alliance The capacity of the therapeutic alliance to predict the success Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1050  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1051 The Concept of Therapeutic Alliance Rupture of a therapy seems to be confirmed. The most frequently-cited meta-analysis of the predictive validity of the alliance is that of Horvath and Symonds (1991). The question at the outset of the meta-analysis is the following: What is the strength of the rela- tionship between the therapeutic alliance and the results of therapy? The study inclusion criteria were the following: 1) the relationship construct measured in the study must be identified by the authors as the working alliance, helping the alliance or therapeutic alliance; 2) the research must concern a quantifiable relationship between the alliance and the indices of subse- quently-measured results; and 3) the studies analyzed must involve at least 5 subjects. Finally, only investigations involv- ing an individual treatment (as opposed to group or family therapies) were included. Twenty-four studies met the above- mentioned criteria. Effect sizes (ES) for all the data were com- bined and a weighted ES was calculated (summarizing the rela- tionship between the therapeutic alliance and the results of the therapy). The combined ES was .26. The size was moderate but very significant (p < .001). According to Pinsof and Catherall (1986), the alliance is a dynamic phenomenon that differs from one therapeutic system to another and changes within the same system during the in- tervention. Usually, as the intervention progresses, the alliance becomes more intense. Different types of interventions and different caseworkers form different types of alliances with similar patients. The alliance varies with the intervention phases. A rupture in the alliance between patient and therapist can occur at any time. The rupture is deterioration stemming either from a disagreement on the goals and tasks or from a problem related to the bond. Such a rupture fractures the alli- ance and creates a decisive moment in the relationship between the patient and therapist. Alliance ruptures can cause the premature end of interven- tions. Disruptions in the alliance may be too great and become irreparable for several reasons. Patients may be too narcissisti- cally vulnerable to manage their disappointment and may reject the treatment. The therapist’s response may not be empathetic enough with the patient’s experience and may thus increase the fracture and sabotage the treatment. Last, the therapist’s mis- take may be so evident and disturbing that the patient’s escape becomes a sound, adaptive response to the therapist’s non-ethi- cal, non-professional or incompetent behaviour (Figure 1). Furthermore, the most extensive survey of the predictive factors of psychotherapy results was carried out by Orlinsky, Grawe and Parks (1994). These authors focus on the relation- ship between the psychotherapeutic approach or specific meas- ures of the therapeutic process and the clinical results. The study inclusion criteria were the following: 1) the studies must comprise real treatments administered to real patients; 2) they must specifically contain therapeutic variables whose changes are measured quantitatively and concomitantly with variations of the results; and 3) they must lend themselves to observation of the relationship between the process and the results. The authors reported 2354 observations on the relationship between the therapeutic process and the clinical results. For the bond and cohesion concepts, 2 concepts of the therapeutic alliance, Orlinsky, Grawe and Parks (1994) listed 132 findings, showing a 66% significant correlation with the treatment data. Types of Ruptures Safran and Muran (2000) identify 2 types of ruptures: with- drawal and confrontation. In withdrawal ruptures, the patient withdraws and partially disengages from the therapist, his own emotions or certain aspects of the therapeutic process. With- drawal ruptures can take different forms. In some cases, the patient has difficulty expressing his concerns or needs in the relationship. For example, one patient expresses his concerns indirectly or attenuates them. In other cases, the patient submits or adapts to the therapist’s desire so subtly that the therapist may have trouble recognizing the patient’s adaptation. More recently, Martin, Garske and Davis (2000) performed a meta-analysis similar to that of Horvath and Symonds (1991). It comprised 79 studies. The combined ES was .22. The size was moderate and significant (p < .05). a P = patient’s behaviour ; b T = therapist’s intervention following the patient’s behaviour Figure 1. Illustrates Model 2.  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. In confrontation ruptures, the patient directly expresses anger or resentment, as well as his dissatisfaction with regard to the therapist or certain aspects of the therapy. For example, one patient has long had a desire for support that has not been filled or a desire to be cared for and a tendency to see the therapist as one more person who will disappoint him. He therefore enters into the therapeutic relationship with a pool of disappointment and rage, waiting to be aroused by the therapist’s inevitable mistakes and limitations. When a confrontation rupture occurs, it may be difficult, if not impossible, for the therapist to avoid responding defensively to the patient’s demands or criticisms; he thus receives the expected response from the other. It often happens that a therapist’s interpretations subtly convey mes- sages of blame and depreciation to his patients, or that these interpretations are complex communications that simultane- ously translate messages of help and of criticism. Withdrawal and confrontation ruptures reflect the various ways that a patient can face tension between the dialecti- cally-opposed needs for individualization and relationships. In withdrawal ruptures, patients fight for the relationship at the expense of their need for individualization or self-definition. In confrontation ruptures, patients negotiate the conflict while favouring the need for individualization or self-definition to the detriment of their need for a relationship. Different patients probably have a predominance for one style of rupture rather than another; this predominance reflects different styles of ad- aptation. Both types of ruptures (withdrawal and confrontation) can emerge during treatment. Given the importance of the therapeutic alliance in the results of therapy, it seems imperative to clarify the process involved in resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures. Experimental Model of Alliance Rupture Resolution The question at the outset of the review is the following: Which models of the alliance rupture resolution process were subjected to experimental investigation? To answer this ques- tion, we performed a computerized search in the following electronic data banks: PsycINFO, ERIC, PsycLIT and Medline. These data banks contain publications from the fields of psy- chology and related sciences. They compile thousands of peri- odicals in several languages from various countries. They refer also to books, theses and technical reports as well as book chapters. The descriptors are: restor* or ruptur* or poor or con- flict* or resolution or problematic or strain* or weak* or viable or repair* or reestablish* and therapeutic alliance or working alliance or helping alliance. Document references are a second source for locating studies. To be included in the review, stud- ies had to present experimental investigation of a model of the alliance rupture resolution process or of the help relationship in a context of psychotherapeutic intervention or psychosocial intervention. The computerized search generated 43 studies. Of this num- ber, 5 met the inclusion criteria: 2 by Safran and Muran (1996), 1 by Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) and 2 by Inck (1995). The particularity of studies that were not retained (n = 38) was that they did not include experimental investigations of a rup- ture resolution process. They were mainly theoretical papers on the therapist-patient relationship or experimental studies on factors that influence the therapist-patient relationship. This review did not consider models such as in Aspland et al. (2008) or Bennett, Parry and Ryle (2006) where they developed only the first steps of the Task analysis by Greenberg (1984b) and Rice and Greenberg (1984). In all studies retained (Safran & Muran, 1996; Safran, Muran, & Samstag, 1994; Inck, 1995), experimental investigation was carried out on the same alliance rupture resolution model: Sa- fran, Muran and Samstag’s Model 2 (1994). Safran, Muran and Samstag’s (1994) Model 2 comprises 4 components. The first, second and fourth include an interven- tion by the therapist that follows behaviour by the patient. The third component includes patient behaviour, an intervention by the therapist and, once again, patient behaviour. The first component (C1, pay attention to the withdrawal rupture indicator) includes P1 (the patient produces a with- drawal rupture indicator) followed by T1 (the therapist focuses the patient on his immediate experience). One patient’s behav- iour suggests that he is avoiding exploration of certain feelings (P1). The therapist draws attention to what is currently happen- ing between them (T1). There are several ways the therapist can conduct this intervention. For example, he may ask questions about the patient’s current experience, such as: “What are you feeling now?” The second component (C2, exploration of the rupture ex- perience) includes P2 (the patient expresses negative feelings mixed with the indicator) followed by T2 (the therapist facili- tates self-affirmation). In response to the therapist’s interven- tion intended to draw the patient’s attention to their current relationship (T1), the patient expresses negative feelings but with some reserve (P2). The therapist intervenes so that the patient expresses his negative feelings more directly (T2). For example, the therapist tells the patient that he feels he has been on the defensive since the beginning of the therapy (T1). The patient then acknowledges that he is starting to feel a bit of anger towards the therapist (P2). The therapist responds to the expression of negative feelings either by showing empathy or by accepting his responsibility for contributing to the interac- tion (T2). For example, in 1 session, the patient asks the thera- pist if he is criticizing him. The therapist admits to having criti- cized him, which can break the impasse. The third component (C3, exploration of avoidance) includes, respectively, P3a (the patient reveals the block), T3 (the thera- pist asks questions about the patient’s block) and P3b (the pa- tient explores the fear that prevents him from expressing nega- tive feelings). In response to the therapist’s intervention in- tended to draw the patient’s attention to their current relation- ship (T1), the patient begins to reveal his hesitations about dis- cussing his negative feelings, either by anticipating this per- spective or by exploring and expressing his experience (P3a). The therapist delves deeper into what is blocking the patient (T3). Typically, in response to the patient’s difficulties ex- pressing his negative feelings (P3a), the therapist directly ques- tions the patient’s fears that block him from expressing his feelings (T3). For example, the patient feels anger towards the therapist but holds back from saying so (P1). In response to the therapist’s questions about what is currently happening between them (T1), the patient indicates that he feels anxiety at the thought of mentioning it (P3a). The therapist then inquires about the nature of this anxiety, asking the patient what is wor- rying him (T3). The therapist’s questioning allows the patient to explore his fear of expressing his negative feelings (P3b). For example, the patient explores his fear of being abandoned by the therapist if he expresses his negative feelings toward Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1052  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. him. The fourth component (C4, self-affirmation) includes P4 (the patient asserts himself) and T4 (the therapist validates the self-affirmation). The patient is then able to express his feelings more directly and self-assertively. For example, the patient expresses, hesitantly, the frustration that he felt during the pre- vious session (P2). The therapist intervenes so that the patient expresses his negative feelings more directly (T2). Gradually, as the patient expresses feelings more directly (P4), the thera- pist approves (T4). The patient thus manages to assert himself in his interactions with the therapist. Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) developed Model 2 with adaptation of the task analysis method employed by Greenberg (1984), Safran, Greenberg and Rice (1988), Rice and Green- berg (1984) and Rice and Saperia (1984). The analysis method comprises 3 major steps. The first step of the analysis method consists in developing a preliminary model of the resolution process based on psychotherapy theories and the researchers’ intuitions (Safran, Segal, Hill, & Whiffen, 1990). In the pre- liminary model, an intervention by the therapist follows the patient’s behaviours. Figure 2 presents the preliminary resolu- tion process model. In the second step, the researchers perform an informal analysis of the preliminary model by comparing it with the content of the psychotherapy sessions in which resolved rup- tures are found (the method for selecting resolved rupture ses- sions will be described in the next section). They identify the gaps between model components and the content of resolved rupture sessions and refine the preliminary model accordingly. They thus obtain Safran, Muran and Samstag’s (1994) Model 1. The researchers develop operational definitions of the compo- nents of Model 1 with a battery of process measurements: sub- scales from the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) (Benjamin, 1974, 1979, 1982), codes from the Patient Experi- encing Scale (P-EXP) (Klein, Mathieu-Coughlan, & Kiesler, 1986) and from the Therapist Experiencing Scale (T-EXP) (Klein, Mathieu-Coughlan, & Kiesler, 1986) and, finally, the tone of voice with the Client Vocal Quality Scale (CVQ) (Rice & Kerr, 1986). Figure 3 presents Model 1. Finally, at the third step, the researchers perform a descrip- tive analysis of Model 1. They analyze 4 resolution sessions and 3 non-resolution sessions by comparing the frequency of the components and subcomponents of the model. The analysis enables them to refine Model 1 and arrive at Model 2. The first refinement of Model 1 for rupture resolution involves the third component (C3, Exploration of the avoidance). In its original design, the component included 2 subcomponents. Analysis suggests the following sequence: recognition of the patient’s block, the therapist’s questions, and the patient’s exploration. The second refinement involves the fourth component (C4, Exploration of the interpersonal pattern). Since the researchers did not find 2 occurrences of this component, they did not con- sider it an essential part of the resolution process. The fourth component becomes the patient’s affirmation. Description of the Experimental Investigation Methods The researchers subject the sequences proposed by Model 2 to experimental investigation. They adopt 2 processes. The first consists in verifying the transitional probabilities of the model only in alliance rupture resolution sessions. Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) engage this process. The second process con- sists of verifying the transitional probabilities of the model in resolution and non-resolution sessions and comparing the re- sults. Safran and Muran (1996) and Inck (1995) used this proc- ess. Table 1 summarizes the methodological elements of the studies. The number of resolution and non-resolution sessions used by the researchers varies between 3 and 4. To evaluate rupture resolution or non-resolution in the sessions, the researchers score 6 items from the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) (Horvath, 1994; Safran, Muran, & Samstag, 1994). After each session, patients and therapists fill out the questionnaire for the beginning, middle and end of the session, for each of the items. When the patient’s and therapist’s evaluations become weaker in the middle than at the beginning and the end of the session (+, −, +), the authors note a deterioration in the relationship and a resolution of the rupture. When the patient’s and therapist’s evaluations become weaker in the middle and at the end than at the beginning of the session (+, −, −), the authors note a dete- rioration in the relationship and rupture resolution. The re- searchers consider differences of more than 20%. Studies by Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) and Inck (1995) involved 3 therapists who held a Ph.D., a master’s de- gree or a clinical psychology license. Safran and Muran (1996) give no information about the therapists. The number of pa- tients varied from 3 to 5 adults. The diagnoses were the fol- lowing: depressive symptoms, major depression, anxiety, dyst- hymia, agoraphobia, cannabis addiction and various personality disorders. Safran and Muran’s (1996) studies do not describe the patients’ diagnoses. Some sessions involve the same thera- pist or patient. Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994), Safran and Muran (1996) and Inck (1995) in their first study employed the same instru- ments to measure the process as those used for Model 1: SASB, P-EXP, T-EXP, CVQ. Inck’s (1995) second study examined an instrument developed by the author: direct identification of the resolution components (DIRC). Weighted coefficients for the resolution and non-resolution sessions vary from .61 to .84 for SASB, from .70 to .95 for P-EXP, from .66 to .80 for T-EXP, from .36 to .55 for CVQ and from .46 to .75 for DIRC. Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994), Safran and Muran (1996) and Inck (1995) for their first study give no indication of the validity of their instruments. In his second study, Inck evaluated the valid- ity of his system of categories by comparing the DIRC codes with the SASB, P-EXP, T-EXP and SVQ codes. Inck gives a validity coefficient varying from .76 to .90 for the DIRC. Results of Transitional Probabilities of the Model Safran and Muran (1996), Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) and Inck (1995) performed sequential analyses to evaluate the transitional probabilities suggested by the model, both within components (P1-T1; P2-T2; P3a-T3-P3b; P4-T4) and between components (C1-C2; C1-C3; C2-C4). Table 2 presents the results of transitional probabilities of the resolution model. The results of Safran, Muran and Samstag’s (1994) sequen- tial analyses do not appear in Table 1 because the authors as- sign z scores rather than probabilities, as in the 4 other studies. Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) performed sequential analyses only on alliance rupture sessions. All sequences within Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1053  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1054 Figure 2. The preliminary resolution process model. Component 1 Attending to the rupture marker Component 2 Exploration of the rupture experienceComponent 3 Exploration of the avoidance Component 4 Exploration of interpersonal schema T1 b Therapist focuses patient on immediate experience P1 a Patient rupture withdrawal marker T3 Therapist probes for fears P3 Patient explores avoidance P4 Patient explores interpersonal schema T2 Therapist empathizes and/or accepts responsibility P2 Patient expresses negative feelings aP = patient’s behaviour b T = therapist’s intervention following the patient’s behaviour. Figure 3. Model 1.  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. Table 1. Methodological elements of the studies. Session Dyads Process measurement instruments2 Studies Processes R1 NRTherapist (T) Patient (P) Reliability Validity Safran & Muran’s (1996) study 1 Compare alliance rupture resolution sessions to non-resolution sessions 4 3 Number and training not available Experiential and cognitive approach Not available SASB .69 - .84 P-EXP .89 - .70 T-EXP .66 - .79 VQC .43 - .55 Not available Safran & Muran’s (1996) study 2 Compare alliance rupture resolution sessions to non-resolution sessions 4 4 Number and training not available Experiential and cognitive approach Not available SASB .61 - .67 P-EXP .89 - .82 T-EXP .70 - .80 VQC .36 - .41 Not available Safran, Muran, & Samstag (1994) Verify the transitional probabilities of Model 2 in alliance rupture resolution sessions 4 T1 Ph.D. and cognitive approach T2 Master’s and cognitive approach T3 Master’s and cognitive approach P1 depression symptoms P2 depression symptoms and anxiety P3 interpersonal problems SASB .69 P-EXP .83 - .95 T-EXP .72 - .79 VQC .55 Not available Inck’s (1995) study 1 Compare alliance rupture resolution sessions to non-resolution sessions 3 3 T1 Ph.D. and cognitive approach T2 Ph.D. and cognitive approach T3 license and cognitive approach P1 depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive and dependent personality. P2 dysthymia, cannabis addiction and personality disorder. P3 major depression, ago- raphobia, obsessive com- pulsive and passive aggres- sive personality. SASB .69 - .78 P-EXP .81 - .92 T-EXP .73 - .78 VQC .38 - .43 Not available Inck (1995) study 2 Compare alliance-rupture resolution sessions 3 3 Same therapists as in Inck’s (1995) study 1 Same subjects as in Inck’s (1995) study 1 DIRC .46 - .75 DIRC .76 - .90 Note: 1R = alliance rupture resolution session; NR = alliance rupture non-resolution session, 2SASB = Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (Benjamin, 1974, 1979, 1982); P-EXP = Patient Experiencing Scale (Klein, Mathieu-Coughlan & Kiesler, 1986); T-EXP = Therapist Experiencing Scale (Klein, Mathieu-Coughlan, & Kiesler, 1986); CVQ = Client Vocal Quality Scale (Rice & Kerr, 1986) Table 2. Results of transitional probabilities of the resolution model. Sequences Safran & Muran (1996) Inck (1995) Study 1 Study 2 Study 1 Study 2 Resolution Non-resolution Resolution Non-resolution Resolution Non-resolution Resolution Non-resolution P1 T1a P2 T2 P3a T3 T3 P3b P4 T4 1.00*** .87*** .58*** .52*** 1.00*** .92** .67*** .10 .00 .00 1.00*** .96*** .83*** .48*** 1.00*** 1.00*** .67*** .27* .19* .00 1.00*** .96*** .83*** .48*** 1.00*** 1.00*** .67*** .27* .19* .00 1.00*** .97*** 1.00*** .84*** 1.00*** 1.00*** .47*** .56** .60*** .00 C1 C2 b C1 C3 C2 C4 .50* .50*** .44** .24 .13 .00 .89* .11 .34** .76 .14 .00 .89* .11 .34* .76 .14 .00 .83* .17 .33* .22 .33* .00 Note: The results of sequential analyses by Safran, Muran and Samstag (1994) do not appear in Table 1. aP1 = the patient produces a withdrawal rupture indicator; T1 = the therapist focuses the patient on his immediate experience; P2 = the patient expresses negative feelings mixed with the indicator; T2 = the therapist facilitates the self-affirmation; P3a = the patient reveals the block; T3 = the therapist asks questions about the patient’s block; P3b = the patient explores the fear that blocks him from expressing negative feelings; P4 = the patient asserts himself; T4 = the therapist validates the self-affirmation. C1 = pay attention to the rupture indicator; C2 = explore the rupture experience; C3 = explore the avoidance; C4 = self-affirmation. ***p < .001 **p < .01 *p < .05. components proved to be significant below .01. z scores varied from 3.01 to 10.06. The significance levels for all sequences between components were below .05. z scores varied from 2.28 to 4.24. Safran and Muran (1996) and Inck (1995) performed sequen- tial analyses of alliance rupture resolution and non-resolution sessions. The first results of sequential analyses by Safran and Muran (1996) and Inck (1995) pertain to sequences within components. Transitional probability for the sequence between P1 (the patient produces a withdrawal rupture indicator) and T1 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1055  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. (the therapist focuses the patient on his immediate experience) was 1.00 (p < .001) in the 4 studies for resolution sessions. For non-resolution sessions, transitional probability was .92 (p < .001) in Safran and Muran’s (1996) first study and 1.00 (p < .001) in the 3 other studies. Transitional probabilities for the sequence between P2 (the patient expresses negative feelings mixed with the indicator) and T2 (the therapist facilitates the self-affirmation) varied from .87 (p < .001) to .97 (p < .001) for resolution sessions and from .42 (p < .001) to .47 (p < .001) for non-resolution sessions. Transitional probability for the se- quence between P3a (the patient reveals the block) and T3 (the therapist asks questions about the patient’s block) varied from .58 (p < .001) to 1.00 (p < .001) for resolution sessions and from .10 to 0.56 (p < .01) for non-resolution sessions. Transitional probability for the sequence between T3 (the therapist asks questions about the patient’s block) and P3b (the patient explores the fear that blocks him from expressing nega- tive feelings) varied from .48 to .84 (p < .001) for resolution sessions and from .00 to .60 (p < .001) for non-resolution ses- sions. Transitional probability for the sequence between P4 (the patient asserts himself) and T4 (the therapist validates the self-affirmation) in the 4 studies was 1.00 (p < .001) for resolu- tion sessions and .00 for non-resolution sessions. The second results of sequential analyses concern sequences between com- ponents. For resolution sessions, transitional probability for the sequence between C1 (pay attention to the rupture indicator) and C2 (explore the rupture experience) varied from .50 (p < .05) to .89 (p < .05) for resolution sessions and from .22 to .76 for non-resolution sessions. Transitional probabilities for the sequence between C1 (pay attention to the rupture indicator) and C3 (explore the avoidance) varied from .11 to .50 (p < .001) for resolution sessions and from .13 to .33 (p < .05) for non-resolution sessions. Transitional probability for the se- quence between C2 (explore the rupture experience) and C4 (self-affirmation) varied from .33 (p < .05) to .44 (p < .01) for resolution sessions. For non-resolution sessions, transitional probabilities were .00 in the 4 studies. The researchers per- formed the sequential analyses with Bakeman’s (1983) Lag 1 software. Results Analysis Generally, the results of sequential analyses confirm both sequence types (within and between components) for resolution sessions more than for non-resolution sessions. However, the results of sequential analyses confirm the hypotheses of se- quences within components more than they do for those be- tween components. In fact, the results of sequential analyses confirm all sequences within the components for resolution and non-resolution sessions alike. Only for resolution sessions do the results confirm sequences between components. The cognitive model of the therapeutic relationship explains these results. Several academics (Horowitz, 1988; Mahoney, 1982; Safran, Vallis, Segal, & Shaw, 1986) suggest that central cognitive structures or patterns organize a patient’s perception of the meaning of other people’s actions. According to Safran (1990) and Safran, Segal, Hill and Whiffen (1990), central cog- nitive structures are conceptualized into generalized expecta- tions regarding a person’s interactions with others or his inter- personal patterns based on past experiences. When these central cognitive structures are dysfunctional, they activate malad- justed interpersonal cognitive cycles where the patient’s expec- tations lead to a behaviour that triggers interpersonal conse- quences, confirming their dysfunctional expectations. For ex- ample, further to numerous abandonments, a person expects to be abandoned by others when beginning new relationships. Consequently, the person acts clingy and dependent, which eventually alienates others and confirms his expectations. An- other person, who lived in a very critical environment, expects others to be critical of him and will therefore act in an ex- tremely self-justifying manner, which irritates others and even- tually provokes the type of criticism that he expects. According to Safran (1990), when the therapist’s actions are consistent with the patient’s dysfunctional interpersonal pattern, he perpetuates a dysfunctional cognitive interpersonal cycle. For example, a therapist who responds to a patient’s hostility with counter-hostility may confirm the patient’s belief that the universe is a hostile place that must be treated with hostility. Furthermore, if the therapist can avoid participating in the pa- tient’s interpersonal cognitive cycle, the patient faces a major experiential challenge to his dysfunctional beliefs. The central mechanism consists of challenging the client’s pathological beliefs. The client interprets the questioning of his dysfunctional beliefs in a way that allows him to collaborate with the therapist. Furthermore, interventions that confirm the client’s dysfunctional beliefs make it difficult to collaborate with the therapist. For example, a client who thinks others will try to dominate him will have difficulty establishing an alliance with a dominant therapist. A client who sees others as being emotionally unavailable will have trouble establishing an alli- ance with a therapist who is withdrawn. Generally, alliance ruptures occur when the therapist’s ac- tions confirm the client’s dysfunctional cognitive structure. A rupture creates a unique situation that allows exploration of the expectations, beliefs, emotions and evaluation processes that play a central role in the client’s dysfunctional interpersonal relationships. For example, a therapist realizes that a client responds to the intervention by withdrawing. Exploring this experience allows the therapist to discover that the client feels he is being treated with condescension, but does not mention it for fear of angering the therapist. Exploring the interpersonal pattern fits in with the entire resolution process proposed by Safran, Muran and Samstag’s (1994) Model 2. The model thus allows the therapeutic alliance to be restored. Conclusion Adolescents in youth centers often undergo treatment against their will. This context seems to make ruptures in the therapeu- tic alliance between youths and their caseworkers inevitable. According to some authors, therapies that include alliance rup- tures appear to be more effective than those without ruptures, on condition, however, that the alliance is restored. The question at the origin of the article is the following: Which models of the alliance rupture resolution process were subjected to experimental investigation? It turns out that very few experimental studies concern models of the resolution process of therapeutic alliance ruptures. Only Safran and Mu- ran’s team conducted a heuristic study on a rupture resolution model that they subjected to experimental investigation. Fur- thermore, the method had limitations. First, in all the studies, the treatment included a very limited number of sessions. The studies involved 6 therapists and the number of patients proved Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1056  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. to be very low, varying from 3 to 5. All these aspects of the method limited generalization of the alliance rupture resolution model. The researchers used a very heavy process analysis method that did not allow a larger sampling. Is replicating studies a way to resolve the problem? Is it possible to simplify the process analysis method? Inck (1995) attempted to remedy this defi- ciency by developing the direct identification of resolution components (DIRC). The idea of directly identifying the com- ponents seems to be an interesting technique. According to Safran (personal communication), the team at- tempts to improve the experimental value of its models by pur- suing its work with other patients and therapists. Safran and Muran (1996, 2000) also turned towards another technique to identify model components: the Core Conflictual Relationship Theme (CCRT) (Luborsky & Crits-Christoph, 1990). The authors of this article also proposed to conduct research that would continue the work by Safran and his colleagues in a psychosocial intervention context among youths with adjust- ment difficulties. They also proposed to rework certain ele- ments of the method, such as the way to select rupture sessions and operationalize model components. REFERENCES Aspland, H., Lewelyn, S., Hardy, Gillian, G. E., Barkham, M., & Stiles, W. (2008). Alliance ruptures and rupture resolution in cogni- tive-behavior therapy: A preliminary task analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 18, 699-710. doi:10.1080/10503300802291463 Bakeman, R. (1983). Computing lag sequential statistics: The ELAG program. Behavior Research Methods and Instrumentation, 15, 530- 535. doi:10.3758/BF03203700 Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1962). Dimension of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic change. Psychological Monographs, 76, 1-36. Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1978). The relationship inventory: Later devel- opment and adaptations (Nos. 8, 68). JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1986). The relationship inventory now: Issues and advances in theory, method, and, use. In L. S. Greenberg, & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research hand- book. New York: Guilford Press. Benjamin, L. S. (1974). Structural analysis of social behavior. Psycho- logical Review, 81, 392-425. doi:10.1037/h0037024 Benjamin, L. S. (1979). Use of structural analysis of social behavior (SASB) and Markov chains to study dynamic interactions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88, 303-319. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.88.3.303 Benjamin, L. S. (1982). Use of structural analysis of social behavior (SASB) to guide intervention in psychotherapy. In J. C. Anchin & D. J. Kiesler (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal psychotherapy (pp. 190-212). New York: Pergamon Press. Bordin, E. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Prac- tice, 16, 252-260. doi:10.1037/h0085885 Brenner, C. (1979). Working alliance, therapeutic alliance, and trans- ference. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 27, 136-158. Bennett, D., Parry, G., & Ryle, A. (2006). Resolving threats to the therapeutic alliance im cognitive analytic therapy of borderline per- sonality disorder: A task analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and practice, 79, 395-418. doi:10.1348/147608305X58355 Curtis, H. C. (1979). The concept of therapeutic alliance: Implications for the “widening scope”. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 27, 159-192. Docherty, J. P (1989). The individual psychotherapies: Efficacy, syn- drome-based treatments, and the therapeutic alliance. In A. Lazare (Ed.), Outpatient psychiatry: Diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed., pp. 624-644). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins Co. Florsheim, P., Shotorbani, S., Guest-Warnick, G., Barratt, T., & Hwang, W.-C. (2000). Role of the working alliance in the treatment of delin- quent boys in community-based programs. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 94-107. doi:10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_10 Freud, S. (1913/1966). On beginning the treatment. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sig- mund Freud. London: Hogarth Press. Frieswyk, S. H., Allen, J. G., Colson, D. B., Coyne, L., Gabbard, G. O., Horowitz, L., & Newsom, G. (1986). Therapeutic alliance: Its place as a process and outcome variable dynamic psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Cli n ic al Psychology, 54, 32-38. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.54.1.32 Gelso, C. J., & Carter, J. A. (1985). The relationship in counseling and psychotherapy: Components, consequences, and theoretical antece- dents. The Counsel i ng Psychologist, 13, 155-243. doi:10.1177/0011000085132001 Greenberg, L. S. (1984). A task analysis of intrapersonal conflict reso- lution. In L. N. Rice, & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Patterns of change: Intensive analysis of psychotherapy process (pp. 67-123). New York: Guilford. Greenson, R. R. (1965). The working alliance and the transference neuroses. Psychotherapy Q u a r te r l y , 34, 155-181. Greenson, R. R. (1967/77). Technique et pratique de la psychanalyse. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. Horvath, A. O. (1994). Empirical validation of Bordin’s pantheoretical model of the alliance: The Working Alliance Inventory perspective. In A. Horvath, & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The working alliance: The- ory, research and practice (pp. 109-128). New York: Wiley. Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and valida- tion of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psy- chology, 36, 223-233. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223 Horvath, A. O., & Symonds, B. D. (1991). Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 139-149. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.38.2.139 Inck, T. A. (1995). Resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures. Unpub- lished Doctoral Dissertation, New York: Adelphi University. Klein, M. H., Mathieu-Coughlan, P., & Kiesler, D. J. (1986). The ex- periencing scales. In L. S. Greenberg, & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 21-71). New York: Guilford. Le Blanc, M., Girard, S., Kaspi, N., Lanctôt, N., & Langelier, S. (1995). Les adolescents en difficulté des années 1990. Rapport no. 3 Adolescents protégés et jeunes contrevenants sous ordonnance de la chambre de la jeunesse de Montréal en 1992-1993. Montréal: École de psychoéducation, Groupe de recherche sur les adolescents en difficulté, Université de Montréal. Lessard, C. (2001). Indicateurs repères sur l’application de la loi sur la protection de la jeunesse 1993-1994 à 1999-2000. Québec: Service des indicateurs et mesure de la performance, Direction de la gestion des information, Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Luborsky, L., & Crits-Christoph, P. (1990). Understanding transfer- ence: The CCRT method. New York: Basic Books. Luborsky, L. (1976). Helping alliance in psychotherapy. In J. L. Cleghhorn (Ed.), Successful psychotherapy (pp. 92-116). New York: Brunner/Mazel. Martin, D. J., Garske, M. J., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-ana- lytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 438-450. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438 Mitchell, K. M., Bozarth, J. D., & Krauft, C. C. (1977). A reappraisal of the therapeutic effectiveness of accurate empathy, nonpossessive warmth, and genuineness. In A. S. Gurman, & A. M. Razin (Eds.), Effective psychotherapy: A handbook of research (pp. 544-565). New York: Pergamon. Moseley, D. C. (1983). The therapeutic relationship and its association with outcome. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Vancouver: University Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1057  P. BAILLARGEON ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1058 of British Columbia. Orlinsky, D. E., Grawe, K., & Parks, B. K. (1994). Process and out- come in psychotherapy—Noch einmal. In A. Bergin, & J. S. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behaviour change (4th edi- tion, pp. 270-378). New York: Wiley. Pauzé, R., Toupin, J., Déry, M., & Mercier, H. (2000). Portrait des jeunes inscrits à la prise en charge des centres jeunesse du Québec et description des services reçus au cours des premiers mois. In D. R. Cloutier (Ed.), Synthèse du rapport: Les soins aux jeunes en difficulté Qc-411 (pp. 1-8). Québec: Centre jeunesse de Québec. Pinsof, W. M., & Catherall, D. R. (1986). The integrative psychother- apy alliance: Family, couple and individual therapy scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 12, 137-151. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1986.tb01631.x Pinsof, W. M. (1995). Integrative problem-centered therapy. New York: Basic Books. Rice, K. S., & Wagstaff, K. (1967). Client voice quality and expressive style as indexes of productive psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 31, 557-563. doi:10.1037/h0025164 Rice, L. N., & Greenberg, L. S. (1984). Future research directions. In L. N. Rice, & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Patterns of change: Intensive analysis of psychotherapy process (pp. 289-308). New York: Guil- ford. Rice, L. N. & Kerr, G. P. (1986). Measures of client and therapist vocal quality. In L. S. Greenberg, & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psycho- therapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 73-105). New York: Guilford. Rice, L. N. & Saperia, E. P. (1984). Task analysis of the resolution of problematic reaction. In L. N. Rice, & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Pat- terns of change: Intensive analysis of psychotherapy process (pp. 67-123). New York: Guilford. Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of thera- peutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95-103. doi:10.1037/h0045357 Safran, J. D. (1990). Towards a refinement of cognitive therapy in light of interpersonal theory: I. Theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 10, 87-105. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(90)90108-M Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (1996). The resolution of ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 64, 447-458. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.447 Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alli- ance: a relational treatment g uide. New York: Guilford. Safran, J. D., Crocker, P., McMain, S., & Murray, P. (1990). Therapeu- tic alliance rupture as a therapy event for empirical investigation. Psychotherapy, 27, 154-165. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.27.2.154 Safran, J. D., Greenberg, L. S., & Rice, L. N. (1988). Integrating psy- chotherapy research and practice: Modeling the change process. Psychotherapy, 25, 1-17. doi:10.1037/h0085305 Safran, J. D., Muran, J. C., & Samstag, L. W. (1994). Resolving thera- peutic alliance ruptures: A task analytic investigation. In A. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The working alliance: Theory, research and practice (pp. 225-255). New York: Wiley. Safran, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Hill, C., & Whiffen, V. (1990). Refining strategies for research on self-representations in emotional disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 143-160. doi:10.1007/BF01176206 Safran, J. D., Vallis, T. M., Segal, Z. V., & Shaw, B. F. (1986). As- sessment of core cognitive processes in cognitive therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10, 509-526. doi:10.1007/BF01177815 Sterba, R. (1934). The fate of the ego in analytic therapy. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 15, 117-126. Zetzel, E. R. (1956). Current concepts of transference. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 37, 369-376

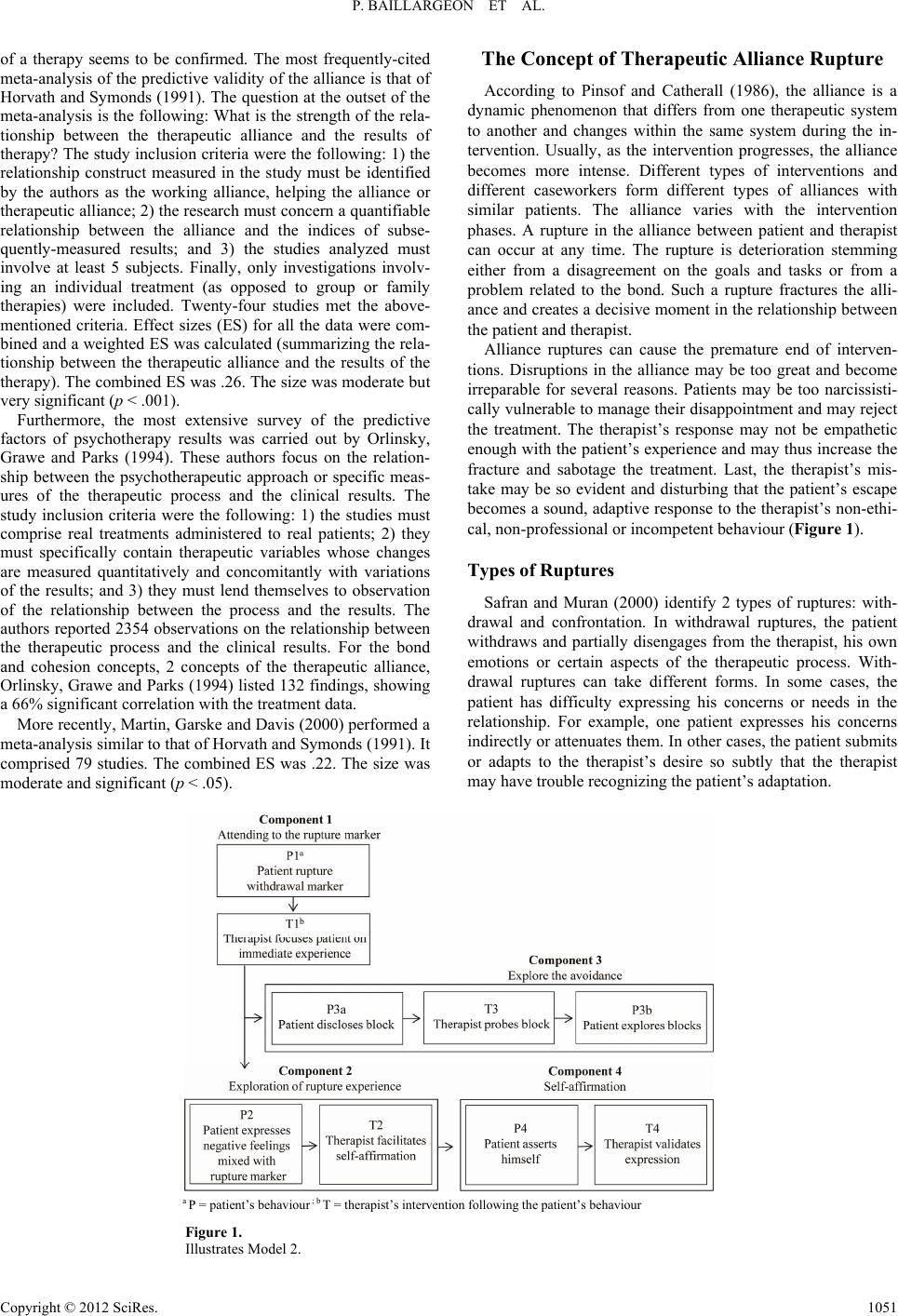

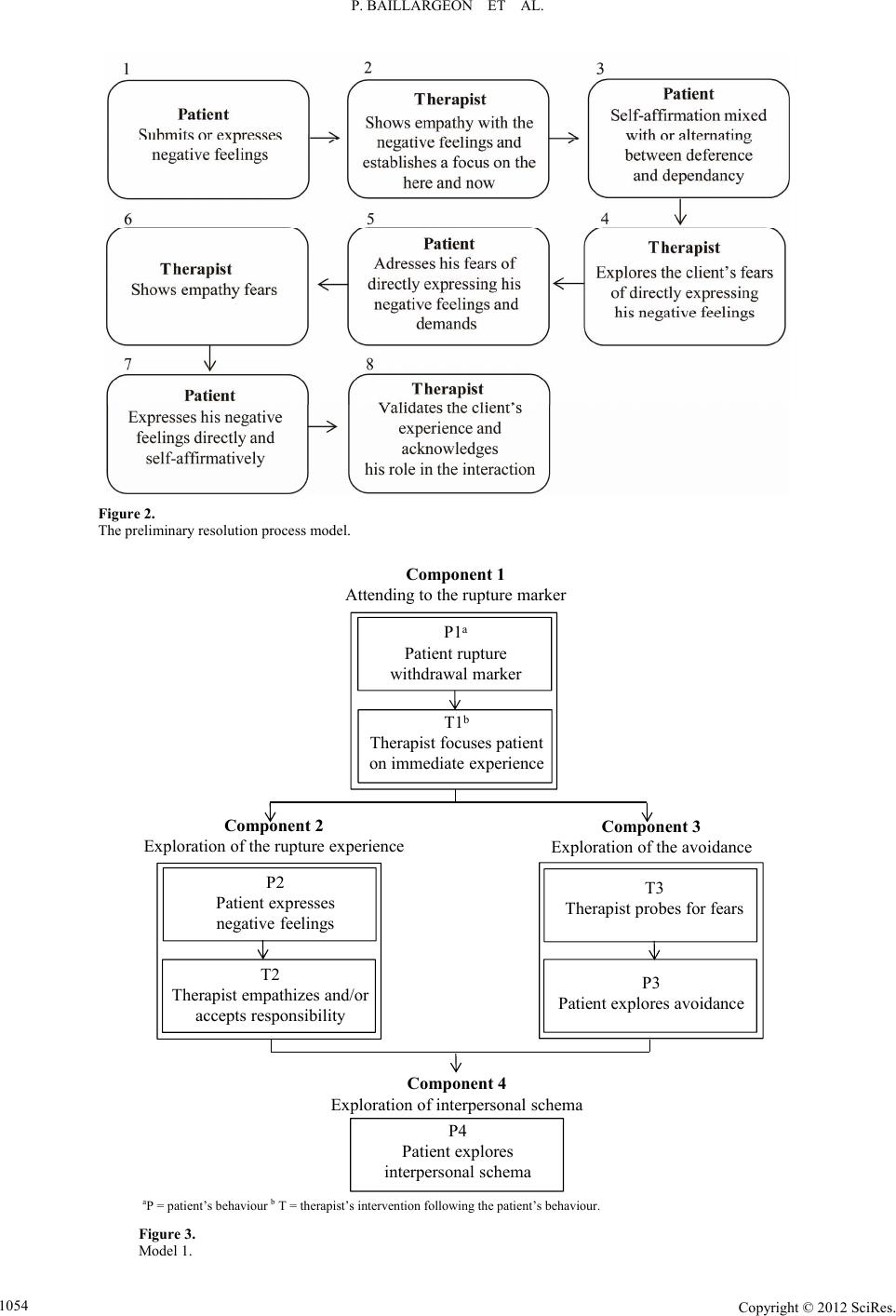

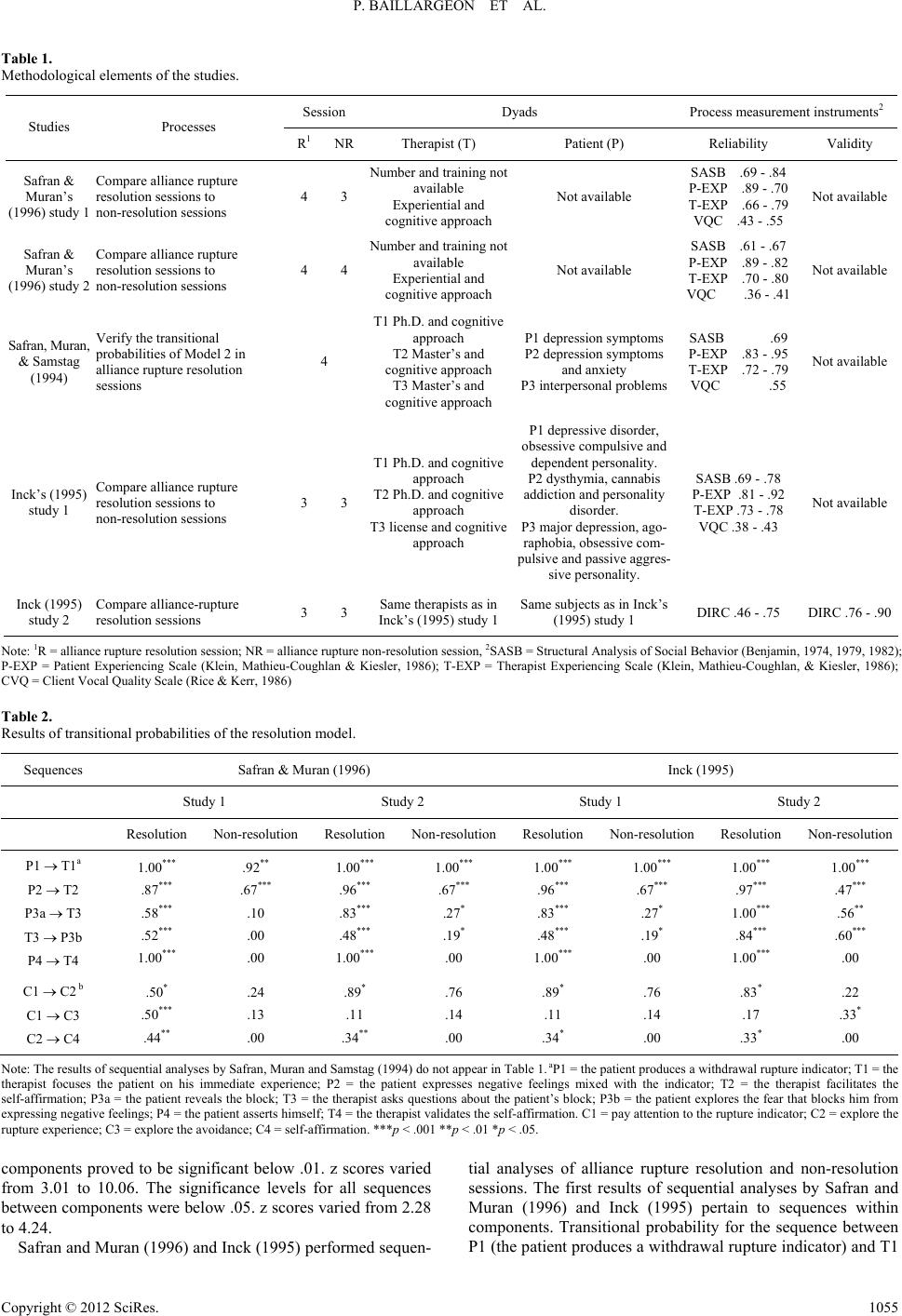

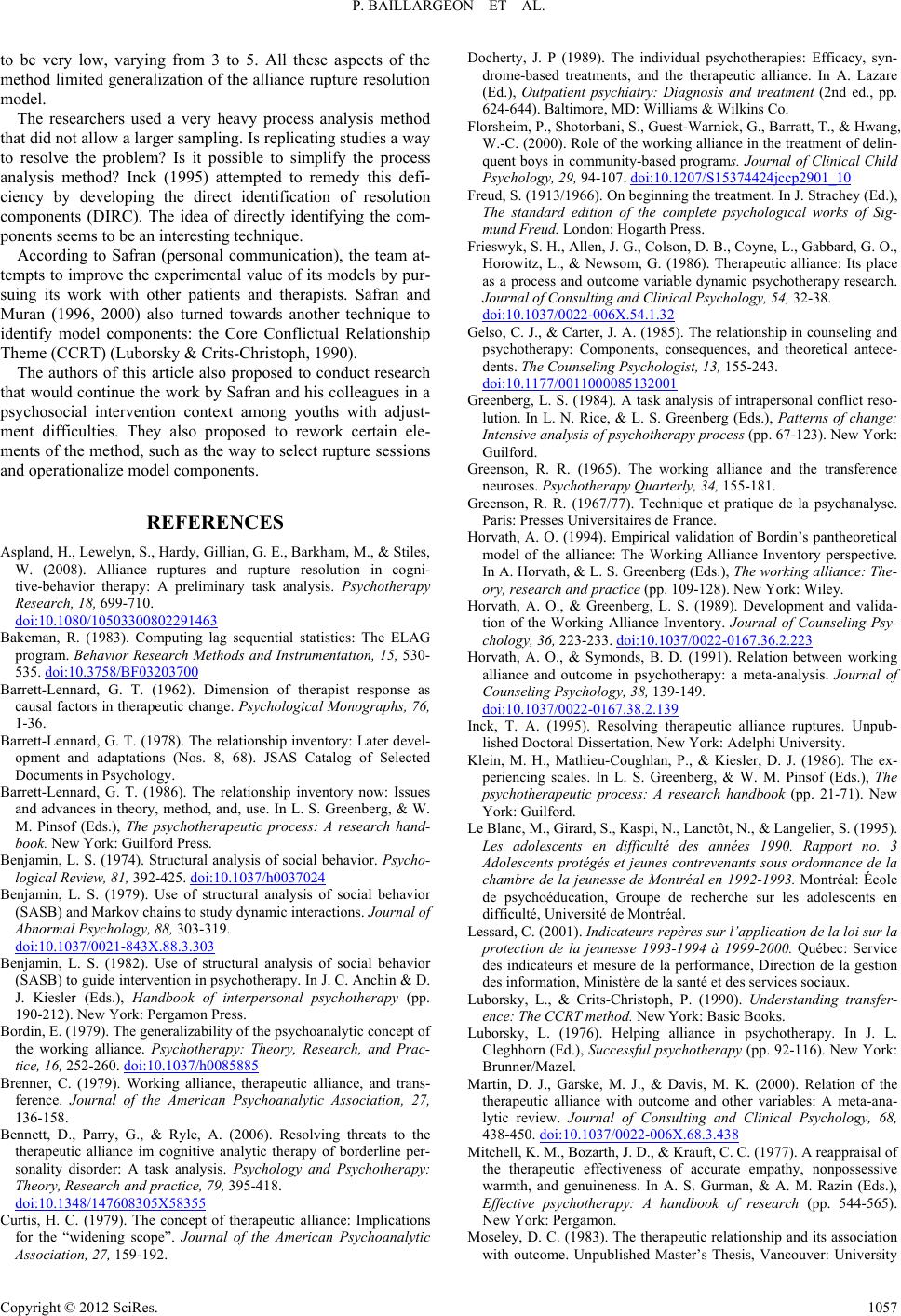

|