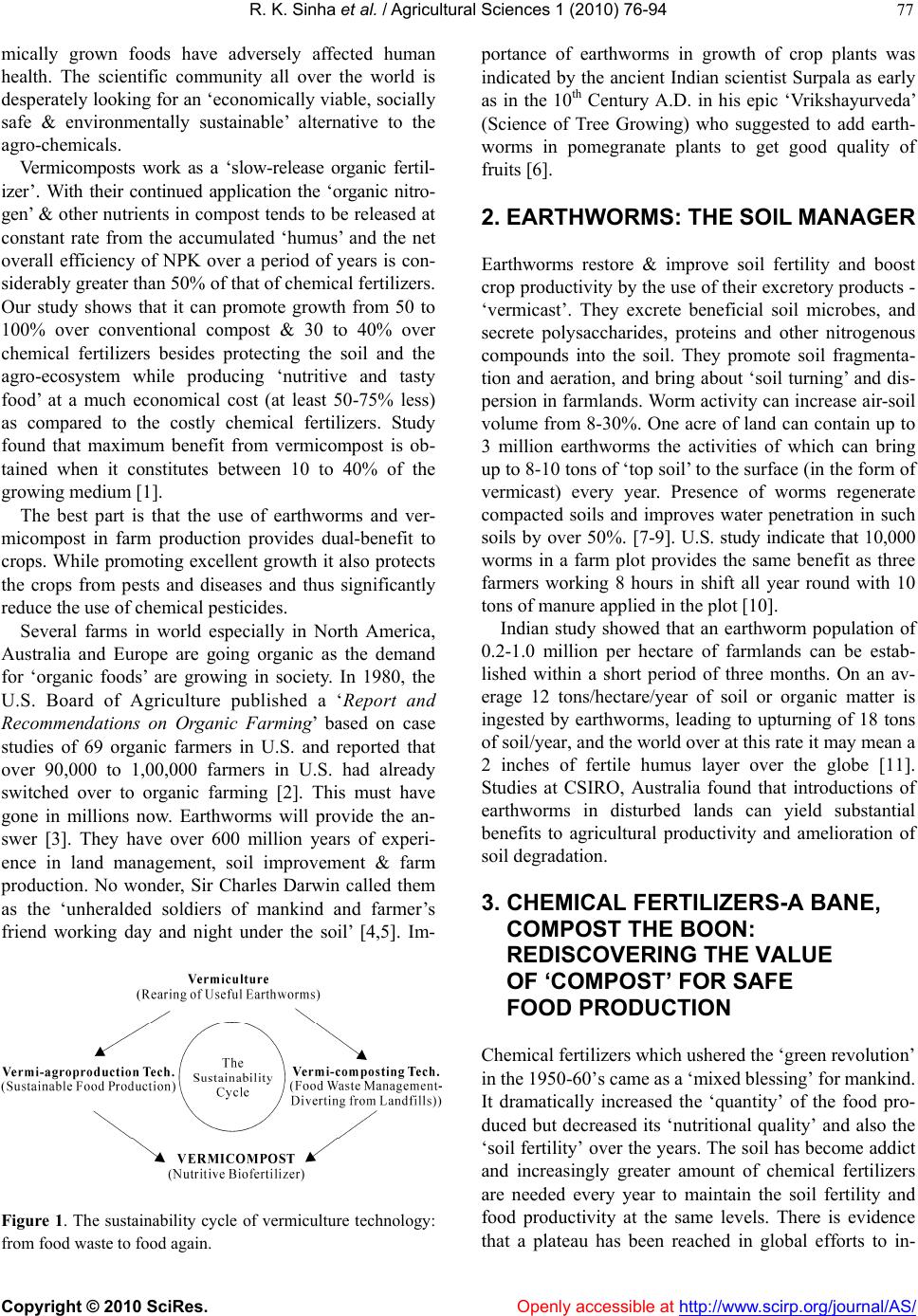

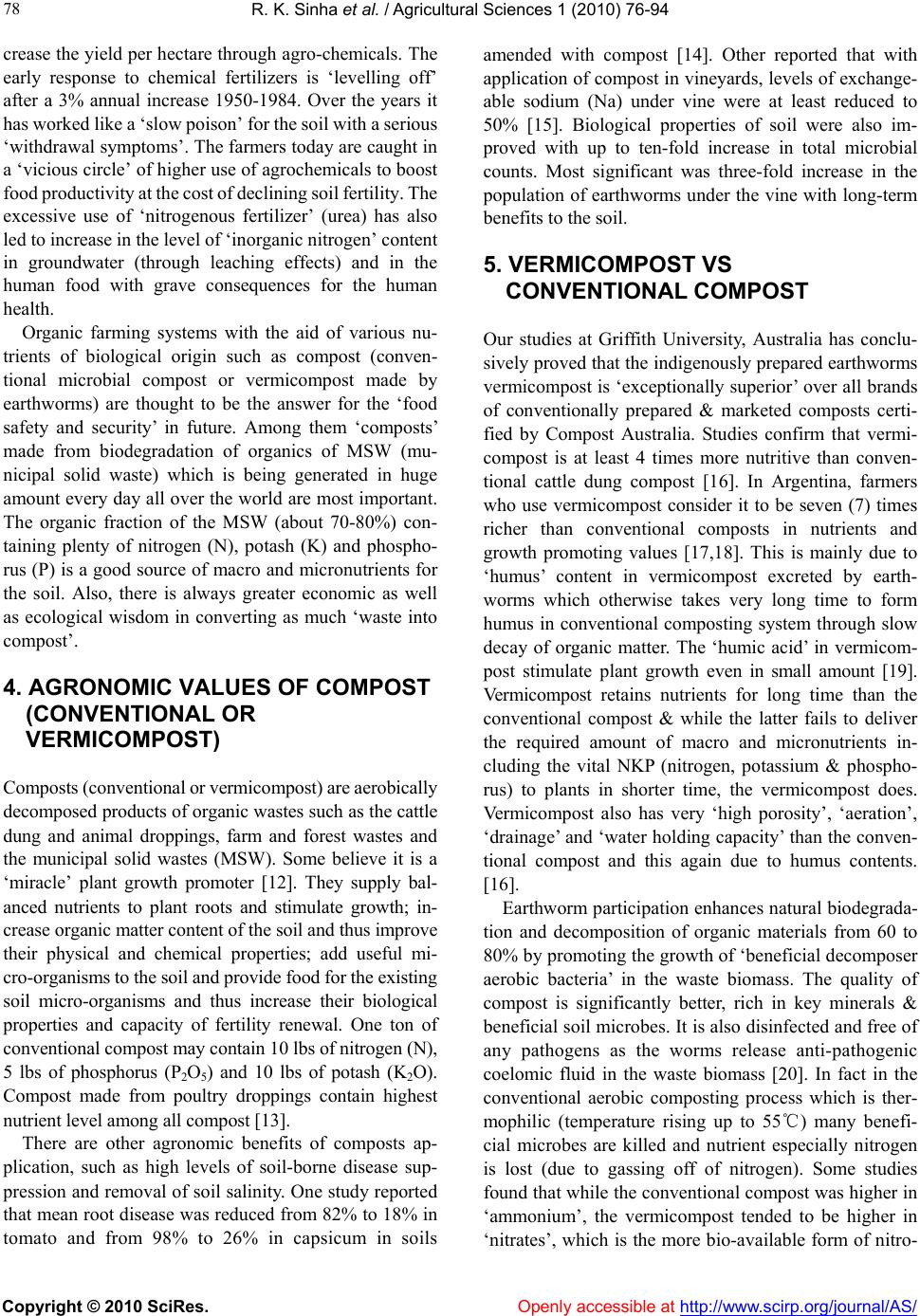

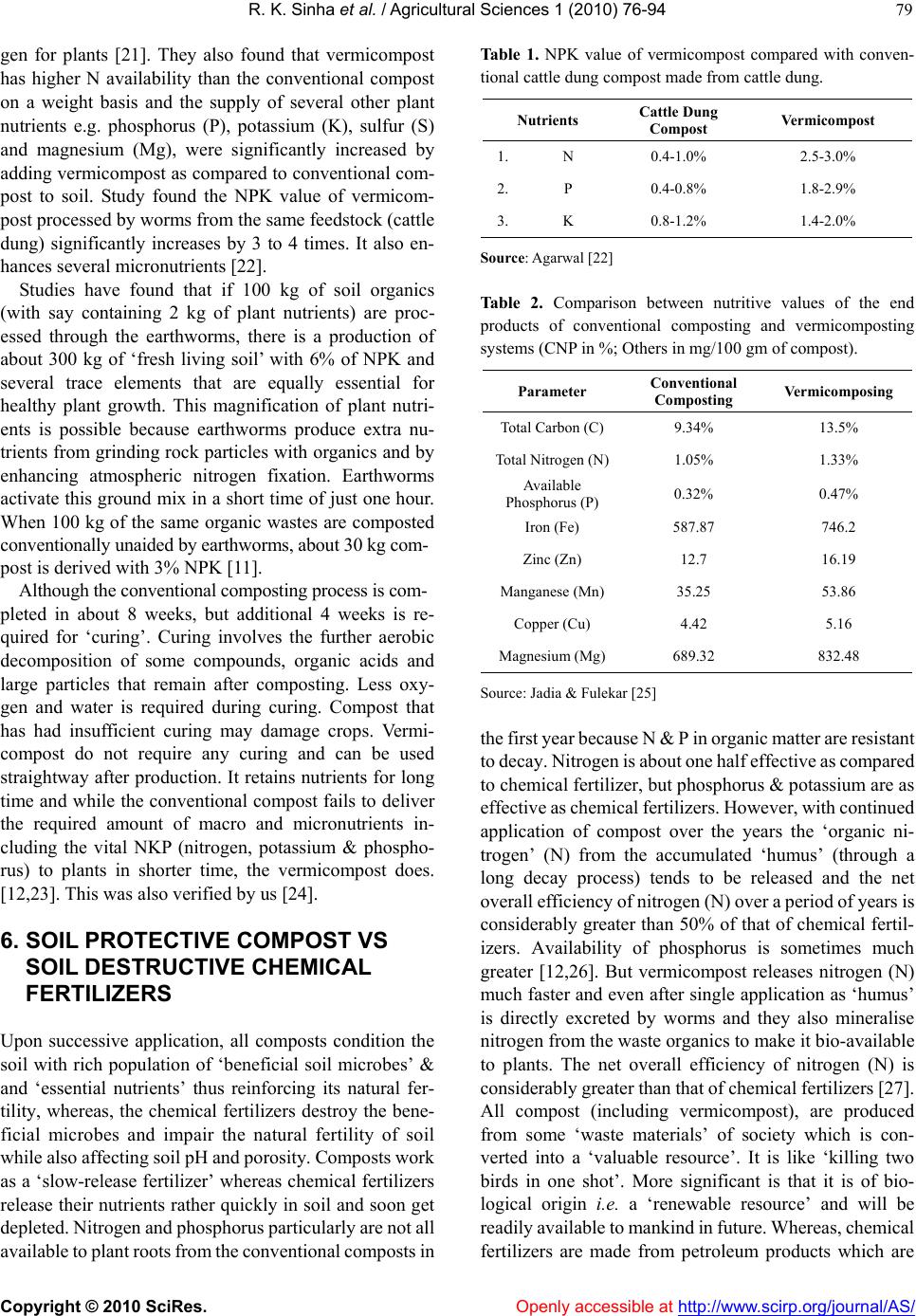

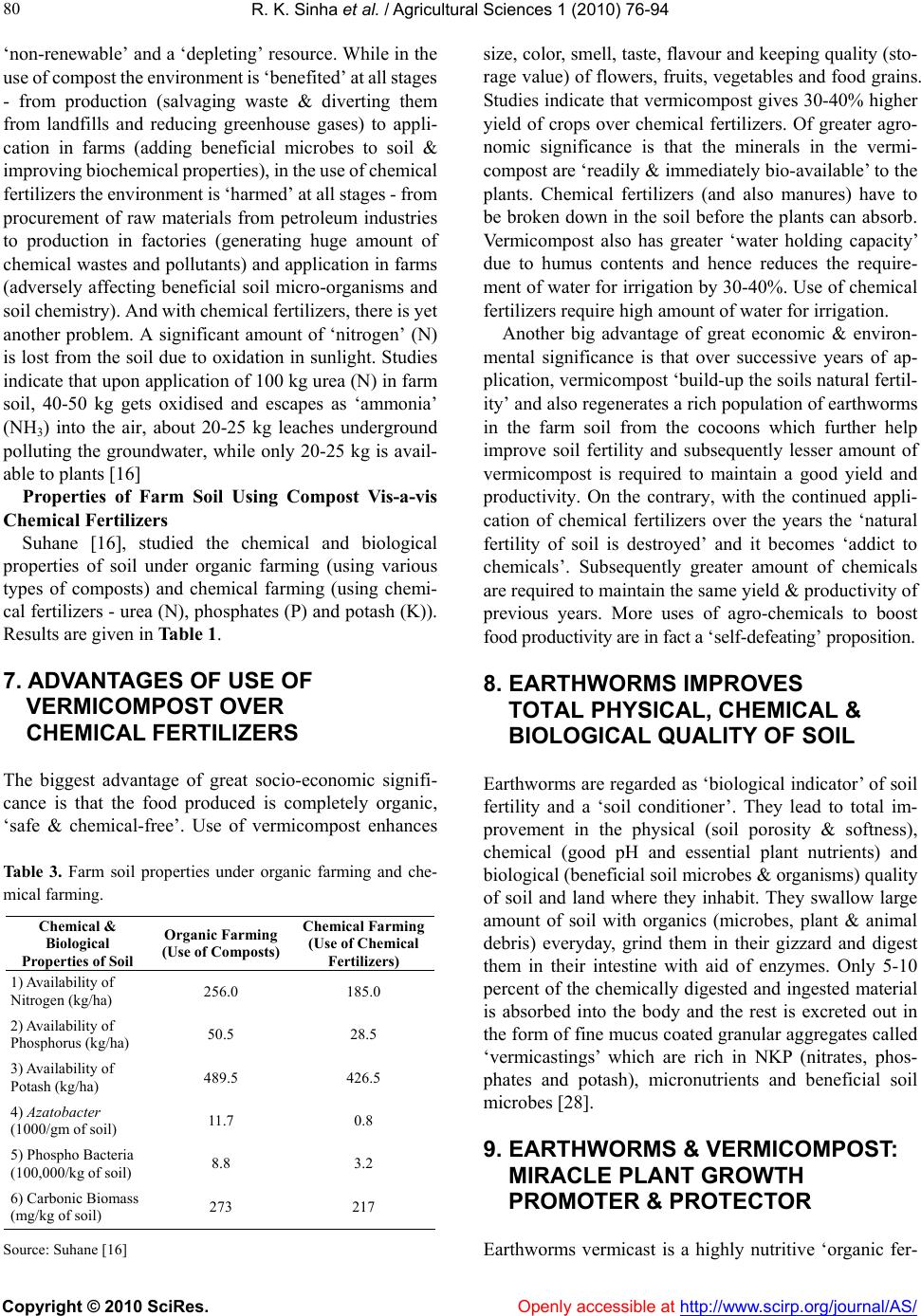

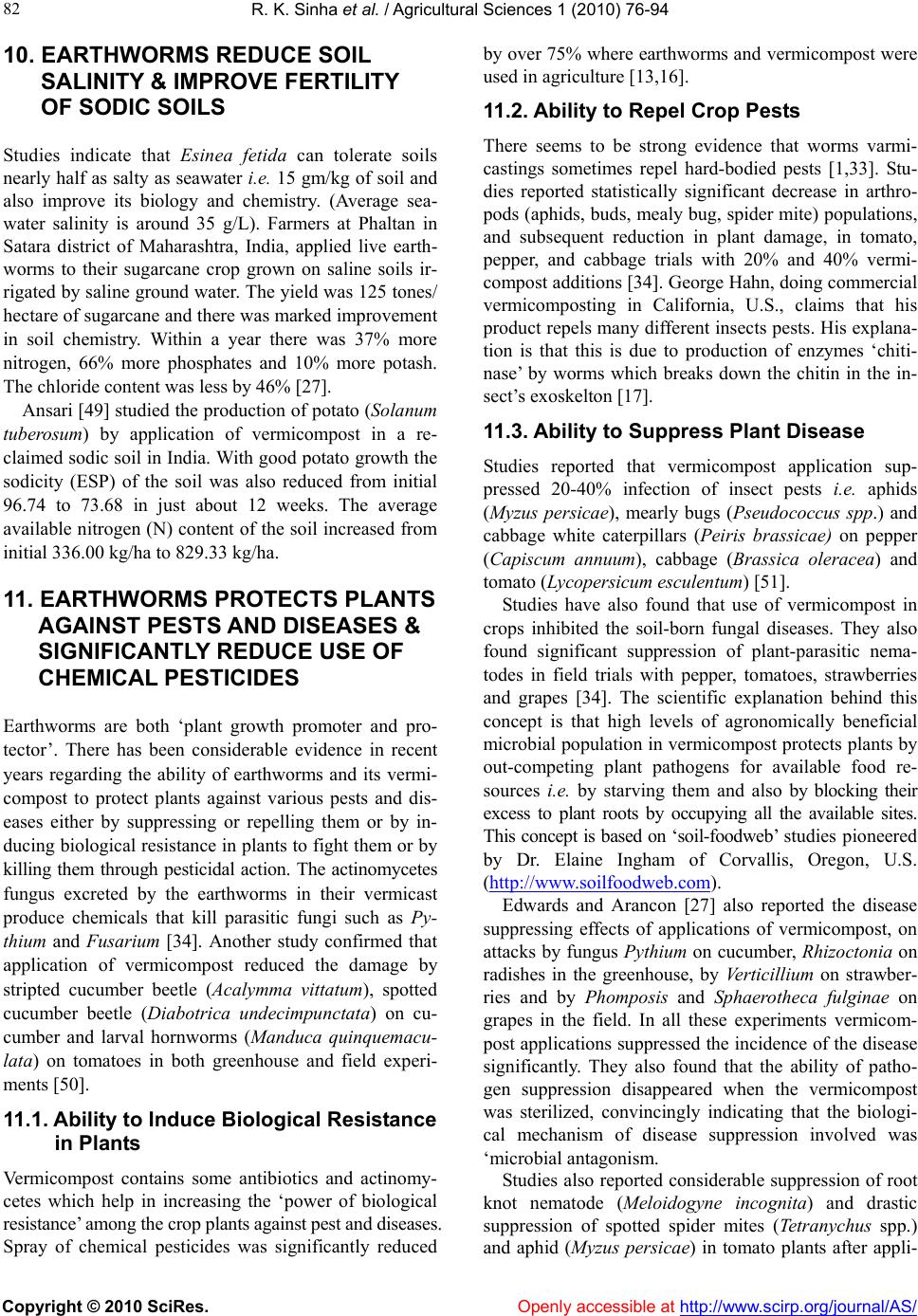

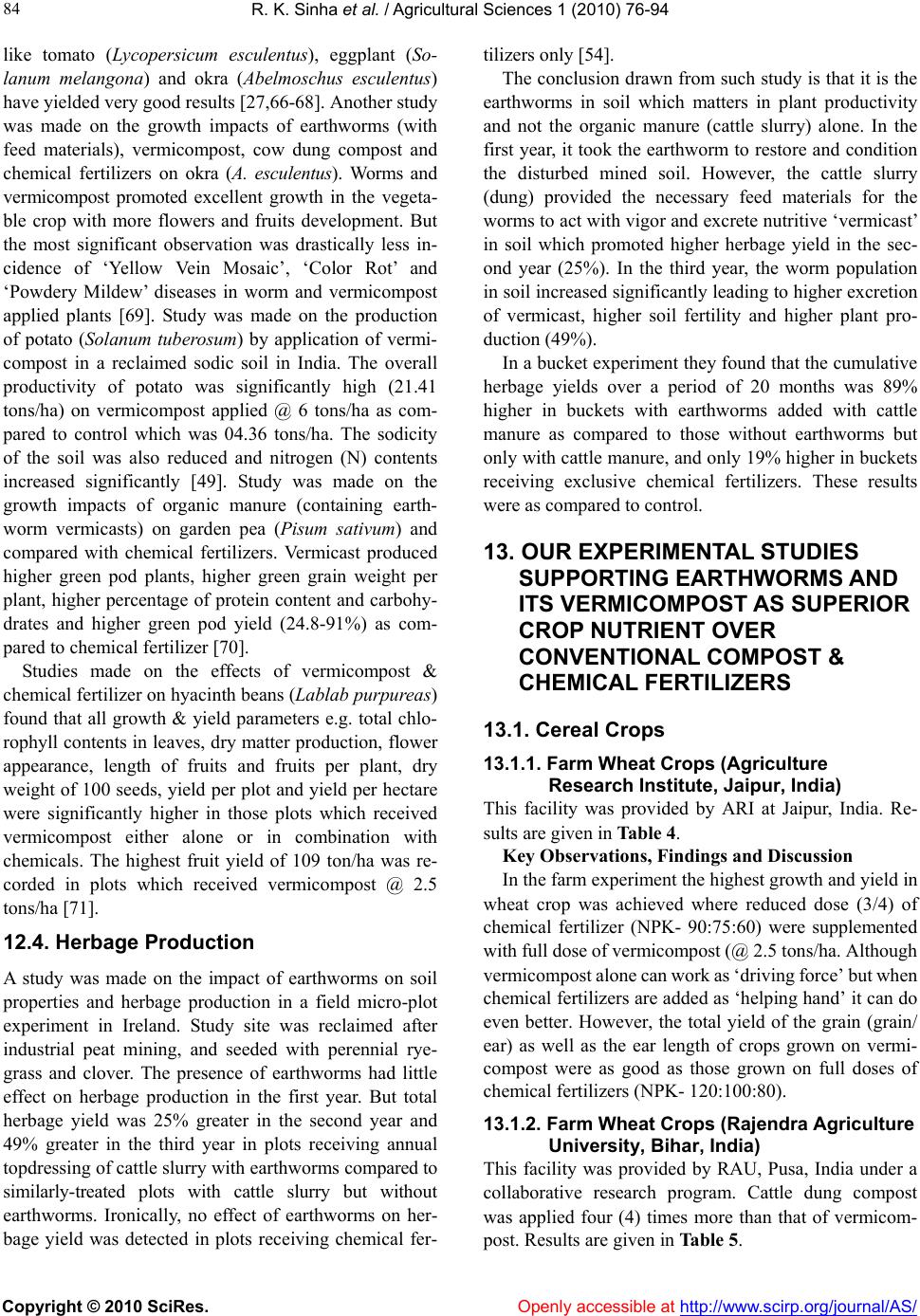

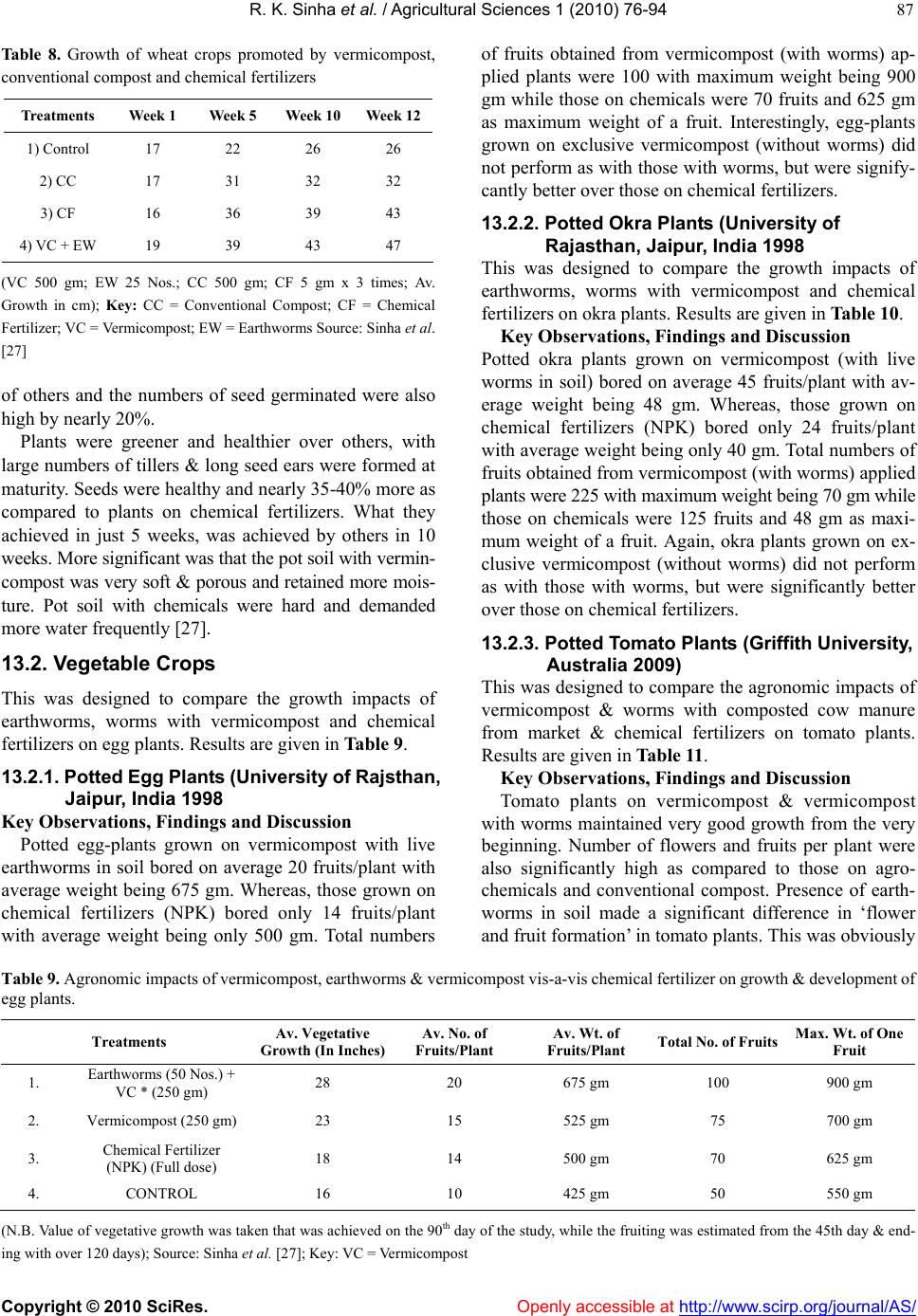

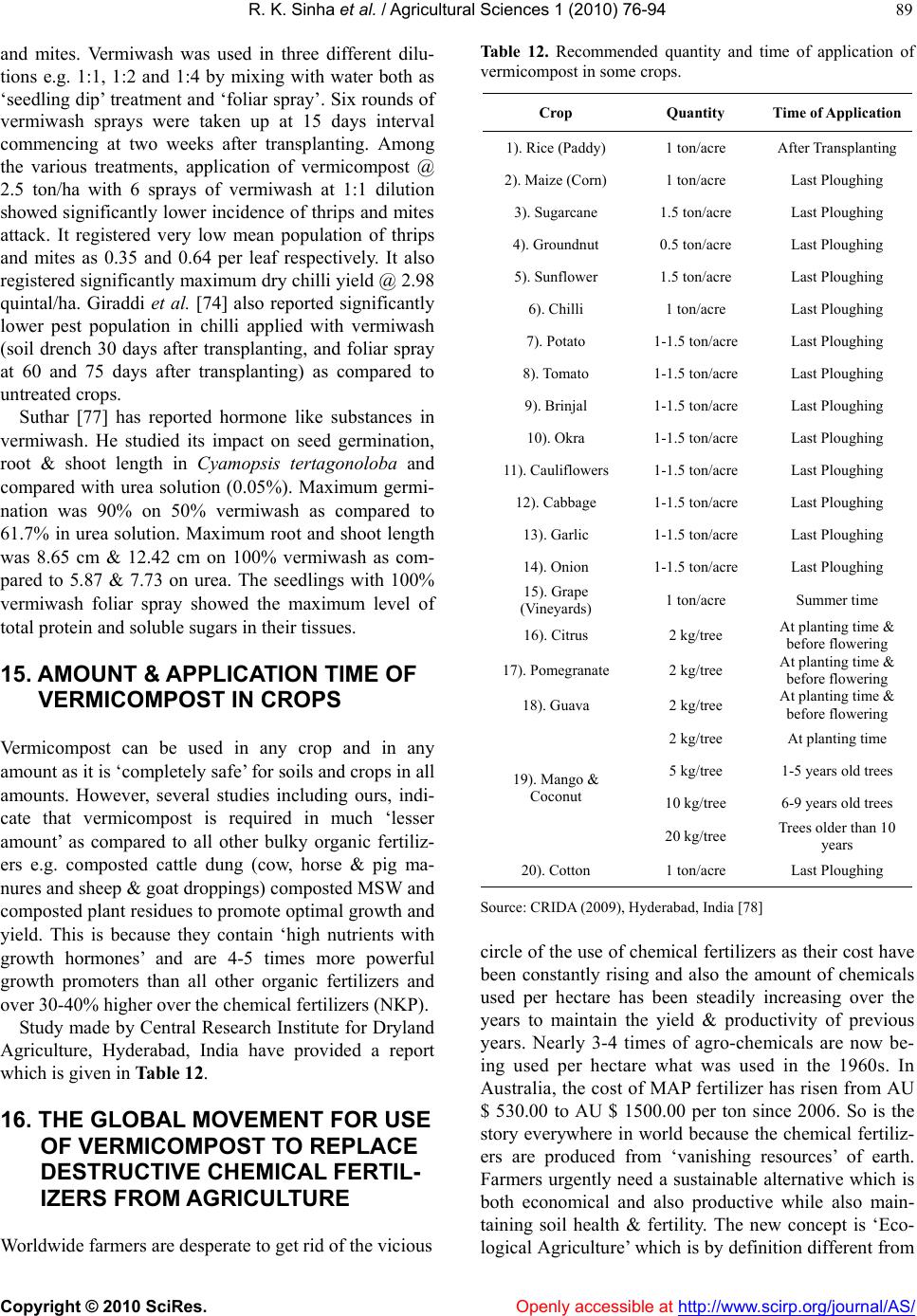

Vol.1, No.2, 76-94 (2010) doi:10.4236/as.2010.12011 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ Agricultural Sciences The wonders of earthworms & its vermicompost in farm production: Charles Darwin’s ‘friends of farmers’, with potential to replace destructive chemical fertilizers from agriculture Rajiv K. Sinha1, Sunita Agarwal2, Krunal Chauhan3, Dalsukh Valani3 1Visiting Senior Lecturer, School of Engineering (Environment), Griffith University, Nathan Campus, Brisbane, Australia; Corresponding Aut hor: Rajiv.Sinha@griffith.edu.au 2Home Science, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, India 3Research Assistant Worked on Vermiculture Projects, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia Received 15 April 2010; revised 2 June 2010; accepted 30 June 2010. ABSTRACT Earthworms and its excreta (vermicast) prom- ises to usher in the ‘Second Green Revolution’ by completely replacing the destructive agro- chemicals which did more harm than good to both the farmers and their farmland. Earth- worms restore & improve soil fertility and sig- nificantly boost crop productivity. Earthworms excreta (vermicast) is a nutritive ‘organic fertil- izer’ rich in humus, NKP, micronutrients, bene- ficial soil microbes—‘nitrogen-fixing & phos- phate solubilizing bacteria’ & ‘actinomycet s’ and growth hormones ‘auxins’, ‘gibberlins’ & ‘cyto- kinins’. Both earthworms and its vermicast & body liquid (vermiwash) are scientifically prov- ing as both ‘growth promoters & protectors’ for crop plants. In our experiments with corn & wheat crops, tomato and egg-plants it displayed excellent growth performances in terms of height of plants, color & texture of leaves, ap- pearance of flowers & fruits, seed ears etc. as compared to chemical fertilizers and the con- ventional compost. There is also less inci- dences of ‘pest & disease attack’ and ‘reduced demand of water’ for irrigation in plants grown on vermicompost. Presence of live earthworms in soil also makes significant difference in flow er and fruit formation in vegetable crops. Com- posts w ork as a ‘slow-release fertilizer ’ w hereas chemical fertilizers release their nutrients rather quickly in soil and soon get depleted. Signifi- cant amount of ‘chemical nitrogen’ is lost from soil due to oxidation in sunlight. However, with application of vermicompost the ‘organic nitro- gen’ tends to be released much faster from the excreted ‘humus’ by worms and those mineral- ised by them and the net overall efficiency of nitrogen (N) is considerably greater than that of chemical fertilizers. Availability of phosphorus (P) is sometimes much greater. Our study sh- ows that earthworms and vermicompost can promote growth from 50 to 100% over conven- tional compost & 30 to 40% over chemical fer- tilizers besides protecting the soil and the agro- ecosystem while producing ‘nutritive and tasty food’ at a much economical cost (at least 50- 75% less) as compared to the costly chemical fertilizers. Keywords: A Slow Release Fertilizer; Vermicompost – Miracle Growth Promoter; Rich in Nutrients; H umus & Hormones; Vermicompost Induce Biological Resistance in Plant; Suppress & Repel Pest Attack 1. INTRODUCTION A revolution is unfolding in vermiculture studies for vermicomposting of diverse organic wastes by waste eater earthworms into a nutritive ‘organic fertilizer’ and using them for production of ‘chemical-free safe food’, both in quantity & quality without recourse to agro- chemicals. Heavy use of agro-chemica ls since the ‘green- revolution’ of the 1960’s boosted food productivity, but at the cost of environment & society. It killed the benefi- cial soil organisms & destroyed their natural fertility, impaired the power of ‘biological resistance’ in crops making them more susceptible to pests & diseases. Che-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 77 mically grown foods have adversely affected human health. The scientific community all over the world is desperately looking for an ‘economically viable, socially safe & environmentally sustainable’ alternative to the agro-chemicals. Vermicomposts work as a ‘slow-release organic fertil- izer’. With their continued application the ‘organic nitro- gen’ & other nutrien ts in compost tends to be released at constant rate from the accumulated ‘humus’ and the net overall efficiency of NPK over a period of years is con- siderably greater than 50% of that of chemical fertilizers. Our study shows that it can promote growth from 50 to 100% over conventional compost & 30 to 40% over chemical fertilizers besides protecting the soil and the agro-ecosystem while producing ‘nutritive and tasty food’ at a much economical cost (at least 50-75% less) as compared to the costly chemical fertilizers. Study found that maximum benefit from vermicompost is ob- tained when it constitutes between 10 to 40% of the growing medium [1]. The best part is that the use of earthworms and ver- micompost in farm production provides dual-benefit to crops. While promoting excellent growth it also protects the crops from pests and diseases and thus significantly reduce the use of chemical pesticides. Several farms in world especially in North America, Australia and Europe are going organic as the demand for ‘organic foods’ are growing in society. In 1980, the U.S. Board of Agriculture published a ‘Report and Recommendations on Organic Farming’ based on case studies of 69 organic farmers in U.S. and reported that over 90,000 to 1,00,000 farmers in U.S. had already switched over to organic farming [2]. This must have gone in millions now. Earthworms will provide the an- swer [3]. They have over 600 million years of experi- ence in land management, soil improvement & farm production. No wonder, Sir Charles Darwin called them as the ‘unheralded soldiers of mankind and farmer’s friend working day and night under the soil’ [4,5]. Im- Figure 1. The sustainability cycle of vermiculture technology: from food waste to food again. portance of earthworms in growth of crop plants was indicated by the ancient Indian scientist Surpala as early as in the 10th Century A.D. in his epic ‘Vrikshayurveda’ (Science of Tree Growing) who suggested to add earth- worms in pomegranate plants to get good quality of fruits [6]. 2. EARTHWORMS: THE SOIL MANAGER Earthworms restore & improve soil fertility and boost crop productivity by th e use of their excr etory products - ‘vermicast’. They excrete beneficial soil microbes, and secrete polysaccharides, proteins and other nitrogenous compounds into the soil. They promote soil fragmenta- tion and aeration, and bring about ‘soil turning’ and dis- persion in farmlands. Worm activity can increase air-soil volume from 8-30%. One acre of land can contain up to 3 million earthworms the activities of which can bring up to 8-10 tons of ‘top soil’ to the surface (in the form of vermicast) every year. Presence of worms regenerate compacted soils and improves water penetration in such soils by over 50%. [7-9]. U.S. study indicate that 10,000 worms in a farm plot provides the same benefit as three farmers working 8 hours in shift all year round with 10 tons of manure applied in the plot [10]. Indian study showed that an earthworm population of 0.2-1.0 million per hectare of farmlands can be estab- lished within a short period of three months. On an av- erage 12 tons/hectare/year of soil or organic matter is ingested by earthworms, leading to upturning of 18 tons of soil/year, and the world over at this rate it may mean a 2 inches of fertile humus layer over the globe [11]. Studies at CSIRO, Australia found that introductions of earthworms in disturbed lands can yield substantial benefits to agricultural productivity and amelioration of soil degrad ation. 3. CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS-A BANE, COMPOST THE BOON: REDISCOVERING THE VALUE OF ‘COMPOST’ FOR SAFE FOOD PRODUCTION Chemical fertilizers which ushered the ‘green revolution’ in the 1950-6 0’s cam e as a ‘m ixed ble ssin g’ for m anki nd. It dramatically increased the ‘quantity’ of the food pro- duced but decreased its ‘nutritional quality’ and also the ‘soil fertility’ over the years. The so il has become addict and increasingly greater amount of chemical fertilizers are needed every year to maintain the soil fertility and food productivity at the same levels. There is evidence that a plateau has been reached in global efforts to in-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 78 crease the yield per hectare through agro-chemicals. The early response to chemical fertilizers is ‘levelling off’ after a 3% annual increase 1950-1984. Over the years it has worked like a ‘slow poison’ for the soil with a serious ‘withdrawal symptoms’. The farmers today are caught in a ‘vicious circle’ of higher use of agrochemicals to boost food productivity at the cost of declining soil fertility. The excessive use of ‘nitrogenous fertilizer’ (urea) has also led to increase in the level of ‘inorganic nitrogen’ content in groundwater (through leaching effects) and in the human food with grave consequences for the human health. Organic farming systems with the aid of various nu- trients of biological origin such as compost (conven- tional microbial compost or vermicompost made by earthworms) are thought to be the answer for the ‘food safety and security’ in future. Among them ‘composts’ made from biodegradation of organics of MSW (mu- nicipal solid waste) which is being generated in huge amount every day all over the world are most important. The organic fraction of the MSW (about 70-80%) con- taining plenty of nitrogen (N), potash (K) and phospho- rus (P) is a good source of macro and micronutrients for the soil. Also, there is always greater economic as well as ecological wisdom in converting as much ‘waste into compost’. 4. AGRONOMIC VALUES OF COMPOST (CONVENTIONAL OR VERMICOMPOST) Composts (con ventional or ve rmicompost) are aerobically decomposed products of organic wastes such as the cattle dung and animal droppings, farm and forest wastes and the municipal solid wastes (MSW). Some believe it is a ‘miracle’ plant growth promoter [12]. They supply bal- anced nutrients to plant roots and stimulate growth; in- crease organic matt er content of t he soil and thus improve their physical and chemical properties; add useful mi- cro-organisms to the soil and provide food for the existing soil micro-organisms and thus increase their biological properties and capacity of fertility renewal. One ton of conventional compost may contain 10 l bs of nitrogen (N), 5 lbs of phosphorus (P2O5) and 10 lbs of potash (K2O). Compost made from poultry droppings contain highest nutrient level among all compost [13]. There are other agronomic benefits of composts ap- plication, such as high levels of soil-borne disease sup- pression and removal of so il salinity. One study reported that mean root disease was reduced from 82% to 18% in tomato and from 98% to 26% in capsicum in soils amended with compost [14]. Other reported that with application of compost in vineyards, levels of exchange- able sodium (Na) under vine were at least reduced to 50% [15]. Biological properties of soil were also im- proved with up to ten-fold increase in total microbial counts. Most significant was three-fold increase in the population of earthworms under the vine with long-term benefits to the soil. 5. VERMICOMPOST VS CONVENTIONAL COMPOST Our studies at Griffith University, Australia has conclu- sively proved that the indigenously prepared earthworms vermicompost is ‘exceptionally superior’ over all brands of conventionally prepared & marketed composts certi- fied by Compost Australia. Studies confirm that vermi- compost is at least 4 times more nutritive than conven- tional cattle dung compost [16]. In Argentina, farmers who use vermicompost consider it to be seven (7) times richer than conventional composts in nutrients and growth promoting values [17,18]. This is mainly due to ‘humus’ content in vermicompost excreted by earth- worms which otherwise takes very long time to form humus in conventional composting system through slow decay of organic matter. The ‘humic acid’ in vermicom- post stimulate plant growth even in small amount [19]. Vermicompost retains nutrients for long time than the conventional compost & while the latter fails to deliver the required amount of macro and micronutrients in- cluding the vital NKP (nitrogen, potassium & phospho- rus) to plants in shorter time, the vermicompost does. Vermicompost also has very ‘high porosity’, ‘aeration’, ‘drainage’ and ‘water holding capacity’ than the conven- tional compost and this again due to humus contents. [16]. Earthworm participation enhances natural biodegrada- tion and decomposition of organic materials from 60 to 80% by promoting the growth of ‘beneficial decomposer aerobic bacteria’ in the waste biomass. The quality of compost is significantly better, rich in key minerals & beneficial soil microbes. It is also disinfected and free of any pathogens as the worms release anti-pathogenic coelomic fluid in the waste biomass [20]. In fact in the conventional aerobic composting process which is ther- mophilic (temperature rising up to 55℃) many benefi- cial microbes are killed and nutrient especially nitrogen is lost (due to gassing off of nitrogen). Some studies found that while the conventional compost was higher in ‘ammonium’, the vermicompost tended to be higher in ‘nitrates’, which is the more bio-available form of nitro-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 79 gen for plants [21]. They also found that vermicompost has higher N availability than the conventional compost on a weight basis and the supply of several other plant nutrients e.g. phosphorus (P), potassium (K), sulfur (S) and magnesium (Mg), were significantly increased by adding vermicompost as compared to conventional com- post to soil. Study found the NPK value of vermicom- post processed by worms from the same feedstock (cattle dung) significantly increases by 3 to 4 times. It also en- hances several m i cron ut ri ent s [2 2] . Studies have found that if 100 kg of soil organics (with say containing 2 kg of plant nutrients) are proc- essed through the earthworms, there is a production of about 300 kg of ‘fresh living soil’ with 6% of NPK and several trace elements that are equally essential for healthy plant growth. This magnification of plant nutri- ents is possible because earthworms produce extra nu- trients from grinding rock particles with organics and by enhancing atmospheric nitrogen fixation. Earthworms activate this ground mix in a short time of just one hour. When 100 kg of the same organic wastes are composted conventionally unaided by earthworm s, about 30 kg com - post is derived with 3% NPK [11]. Although the conventional com posting process i s com- pleted in about 8 weeks, but additional 4 weeks is re- quired for ‘curing’. Curing involves the further aerobic decomposition of some compounds, organic acids and large particles that remain after composting. Less oxy- gen and water is required during curing. Compost that has had insufficient curing may damage crops. Vermi- compost do not require any curing and can be used straightway after production. It retains nutrients for long time and while the conven tional compost fails to deliver the required amount of macro and micronutrients in- cluding the vital NKP (nitrogen, potassium & phospho- rus) to plants in shorter time, the vermicompost does. [12,23]. This was also verified by us [2 4] . 6. SOIL PROTECTIVE COMPOST VS SOIL DESTRUCTIVE CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS Upon successive application, all composts condition the soil with rich population of ‘beneficial soil microbes’ & and ‘essential nutrients’ thus reinforcing its natural fer- tility, whereas, the chemical fertilizers destroy the bene- ficial microbes and impair the natural fertility of soil while also affecting soil pH and porosity. Composts work as a ‘slow-release fertilizer’ whereas chemical fertilizers release their nutrients rather qu ickly in soil and soon get depleted. Nitrogen and phosphorus particularly are not all available to plant roots from the conventional composts in Ta b l e 1 . NPK value of vermicompost compared with conven- tional cattle dung compost made from cattle dung. Nutrients Cattle Dung Compost Vermicompost 1.N 0.4-1.0% 2.5-3.0% 2.P 0.4-0.8% 1.8-2.9% 3.K 0.8-1.2% 1.4-2.0% Source: Ag arwal [22] Table 2. Comparison between nutritive values of the end products of conventional composting and vermicomposting systems (CNP in %; Others in mg/100 gm of compost). Parameter Conventional Composting Vermicomposing Total Carbon (C) 9.34% 13.5% Total Nitrogen (N)1.05% 1.33% Available Phosphorus (P) 0.32% 0.47% Iron (Fe) 587.87 746.2 Zinc (Zn) 12.7 16.19 Manganese (Mn) 35.25 53.86 Copper (Cu) 4.42 5.16 Magnesium (Mg) 689.32 832.48 Source: Jadia & Fulekar [25] the first year because N & P in orga nic matter are resi stant to decay. Nitrogen is about one half effective as com pared to chemical fertilizer, but phosphorus & potassium are as effective as chemical fertilizers. However, with continued application of compost over the years the ‘organic ni- trogen’ (N) from the accumulated ‘humus’ (through a long decay process) tends to be released and the net overall effi ciency of nit rogen (N) over a period of year s is considerably greater than 50% of that of chemical fertil- izers. Availability of phosphorus is sometimes much greater [12,26]. But vermicompost releases nitrogen (N) much faster and even after single application as ‘humus’ is directly excreted by worms and they also mineralise nitrogen from the waste organics to make it bio -available to plants. The net overall efficiency of nitrogen (N) is considerably greater than that of chemical fertilizers [27]. All compost (including vermicompost), are produced from some ‘waste materials’ of society which is con- verted into a ‘valuable resource’. It is like ‘killing two birds in one shot’. More significant is that it is of bio- logical origin i.e. a ‘renewable resource’ and will be readily available to mankind i n future. Whereas, chem ical fertilizers are made from petroleum products which are  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 80 ‘non-renewable’ and a ‘depleting ’ resource. While in the use of com post the environment is ‘benefited’ at all stages - from production (salvaging waste & diverting them from landfills and reducing greenhouse gases) to appli- cation in farms (adding beneficial microbes to soil & improvin g biochem ical properti es), in the u se of chem ical fertilizers the environment is ‘harmed’ at all stages - from procurement of raw materials from petroleum industries to production in factories (generating huge amount of chemical wastes and pollutants) and application in farms (adversely affecting beneficial soil micro-organisms and soil chemistry). And with chemical fertilizers, there is yet another problem. A significant amount of ‘nitrogen’ (N) is lost from the soil due to oxidation in sunlig ht. Studies indicate that upon application of 100 kg urea (N) in farm soil, 40-50 kg gets oxidised and escapes as ‘ammonia’ (NH3) into the air, about 20-25 kg leaches underground polluting the groundwater, while only 20-25 kg is avail- able to plants [16] Properties of Farm Soil Using Compost Vis-a-vis Chemical Fertilizers Suhane [16], studied the chemical and biological properties of soil under organic farming (using various types of composts) and chemical farming (using chemi- cal fertilizers - urea (N), phosphates (P) and potash (K)). Results are given in Table 1. 7. ADVANTAGES OF USE OF VERMICOMPOST OVER CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS The biggest advantage of great socio-economic signifi- cance is that the food produced is completely organic, ‘safe & chemical-free’. Use of vermicompost enhances Ta bl e 3. Farm soil properties under organic farming and che- mical farming. Chemical & Biological Propertie s o f S o il Organic Farming (Use of Composts) Chemical Farming (Use of Chemical Fertilizers) 1) A vail ability of Nitrogen (kg/ha) 256.0 185.0 2) A vail ability of Phosphorus (kg/ha) 50.5 28.5 3) A vail ability of Potash (kg/ha) 489.5 426.5 4) Azatobacter (1000/gm of soil) 11.7 0.8 5) Phospho Bacteria (100,000/kg of soil) 8.8 3.2 6) Carbonic Biomass (mg/kg of soil) 273 217 Source: Suhane [16] size, color, smell, taste, flavour an d keeping quality (sto - rage value) of flowers, fruits, vegetables and food grains. Studies indicate that vermicompost gives 30-40% higher yield of crops over chemical fertilizers. Of greater agro- nomic significance is that the minerals in the vermi- compost are ‘readily & immediately bio-available’ to the plants. Chemical fertilizers (and also manures) have to be broken down in the soil before the plants can absorb. Vermicompost also has greater ‘water holding capacity’ due to humus contents and hence reduces the require- ment of water for irrigation by 30-40%. Use of chemical fertilizers require high amount of water for irrigation. Another big advantage of great economic & environ- mental significance is that over successive years of ap- plication, vermicompost ‘build-up the so ils natural fertil- ity’ and also regenerates a rich population of earthworms in the farm soil from the cocoons which further help improve soil fertility and subsequently lesser amount of vermicompost is required to maintain a good yield and productivity. On the contrary, with the continued appli- cation of chemical fertilizers over the years the ‘natural fertility of soil is destroyed’ and it becomes ‘addict to chemicals’. Subsequently greater amount of chemicals are required to maintain the same yield & productiv ity of previous years. More uses of agro-chemicals to boost food productivit y are in fact a ‘self-defeat ing’ proposi tion. 8. EARTHWORMS IMPROVES TOTAL PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL & BIOLOGICAL QUALITY OF SOIL Earthworms are regarded as ‘biological indicator’ of soil fertility and a ‘soil conditioner’. They lead to total im- provement in the physical (soil porosity & softness), chemical (good pH and essential plant nutrients) and biological (beneficial soil microbes & organisms) quality of soil and land where they inhabit. They swallow large amount of soil with organics (microbes, plant & animal debris) everyday, grind them in their gizzard and digest them in their intestine with aid of enzymes. Only 5-10 percent of the chemically digested and ingested material is absorbed into the body and the rest is excreted out in the form of fine mucus coated granular aggregates called ‘vermicastings’ which are rich in NKP (nitrates, phos- phates and potash), micronutrients and beneficial soil microbes [28]. 9. EARTHWORMS & VERMICOMPOST: MIRACLE PLANT GROWTH PROMOTER & PROTECTOR Earthworms vermicast is a highly nutritive ‘organic fer-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 81 tilizer’ rich in humus, NKP (nitrogen 2-3%, potassium 1.85-2.25% and phosphorus 1.55-2.25%), micronutrients, beneficial soil microbes like ‘nitrogen-fixing bacteria’ and ‘mycorrhizal fungi’ and are scientifically proving as ‘miracle growth promoters’. [29-31]. One study reports as high as 7.37% nitrogen (N) and 19.58% phos- phorus as P2O5 in worms vermicast [32]. Another study showed that exchangeable potassium (K) was over 95% higher in vermicompost [16]. There are also good amount of calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg). Vermi- compost has very ‘high porosity’, ‘aeration’, ‘drainage’ and ‘water holding capacity’. More important is that it contains ‘plant-available nutrients’ and appears to in- crease & retain more of them for longer period of time. A matter of still greater agronomic significance is that worms & vermicompost also increases ‘biological resis- tance’ in plants (due to Actinomycetes) and protect them against pest and diseases either by repelling or by sup- pressing them [1,34,35]. 9.1. High Levels of Bio-Available Nutrients for Plants Earthworms miner alize the nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) and all essential organic & inorganic elements in the compost to make it bio-available to plants as nutrients [36]. They recycle nitrogen in soil in very short time ranging fro m 20 to 200 kg N/ha/year & increase nitrogen contents by over 85% [37]. After 28 weeks the soil with living worms contained 75 ppm of nitrate nitrogen (N), compared with the controlled soil which had only 45 ppm [38]. Worms increase nitrogen levels in soil by adding their metabolic & excretory products (vermicast), mucus, body fluid, enzymes and decaying tissues of dead worms [39,40]. Lee [41] suggests that the passage of organic matter through the gut of worm results in phosphorus (P) converted to forms which are more bio-available to plants. This is done partly by worm’s gut enzyme ‘phosphatases’ and partly by the release of phosphate solubilizing microorganisms in the worm cast [42]. 9.2. High Level of Beneficial and Biologically Active Soil Microorganisms Among beneficial soil microbes stimulated by earth- worms are ‘nitrogen-fixing & phosphate solubilizing bacteria’, the ‘actinomycetes’ & ‘mycorrhizal fungi’. Stu dies found that the total bacterial count was more than 1010/gm of vermicompost. It included Actinomycetes, Azotobacter, Rhizobium, Nitrobacter & Phos-phate Solu- bilizing Bacteria ranges from 102-1 0 6 per gm of vermi- compost [16]. 9.3. Rich in Humus: Key to Grow th and Survival of Plants Vermicompost contains ‘humus’ excreted by worms which makes it markedly different from other organic fertilizers. It takes several years for soil or any organic matter to decompose to form humus while earthworms secrete humus in its excreta. Without humus plants cannot grow and survive. The humic and fulvic acids in humus are essential to plants in four basic ways – 1) Enables plant to extract nutrients from soil; 2) Help dissolve unresolved minerals to make organic matter ready for plants to use; 3) Stimulates root growth; and, 4) Helps plants overcome stress. Presence of humus in soil even help chemical fertilizers to work better [43]. This was also confirmed by other study [44]. One study found that humic acids isolated from vermicompost enhanced root elongation and formation of lateral roots in maize roots. Humus in vermicast also extracts ‘tox- ins’, ‘harmful fungi & bacteria’ from soil & protects plants [19]. 9.4. Rich in Plant Growth Hormones Some studies speculated that the growth responses of plants from vermicompost appeared more like ‘hor- mone-induced activity’ associated with the high levels of nutrients, humic acids and humates in vermicompost [21, 45]. Researches show that vermicompost use further stimulates plant growth even when plants are already receiving ‘optimal nutrition’. It consistently improved seed germination, enhanced seedling growth and devel- opment, and increased plant productivity significantly much more than would be possible from the mere con- version of mineral nutrients into plant-available forms. Some studies have also reported that vermicompost con- tained growth promoting hormone ‘auxins’, ‘cytokinins’ and flowering hormone ‘gibberlins’ secreted by earth- worms [16,47,48]. 9.5. Enzymes for Improving Soil Nutrients & Fertility Vermicompost contain enzymes like amylase, lipase, cellulase and chitinase, which continue to break down organic matter in the soil (to release the nutrients and make it available to the plant roots) even after th ey have been excreted. [30,31]. They also increases the levels of some important soil enzymes like dehydrogenase, acid and alkaline phosphatases and urease. Urease play a key role in N-cycle as it hydrolyses urea and phosphatase bioconvert soil phosphorus into bio-available form for plants.  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 82 10. EARTHWORMS REDUCE SOIL SALINITY & IMPROVE FERTILITY OF SODIC SOILS Studies indicate that Esinea fetida can tolerate soils nearly half as salty as seawater i.e. 15 gm/k g of soil and also improve its biology and chemistry. (Average sea- water salinity is around 35 g/L). Farmers at Phaltan in Satara district of Maharashtra, India, applied live earth- worms to their sugarcane crop grown on saline soils ir- rigated by saline ground water. The yield was 125 tones/ hectare of sugarcane and there was marked improvement in soil chemistry. Within a year there was 37% more nitrogen, 66% more phosphates and 10% more potash. The chloride content was less by 46% [27]. Ansari [49] studied th e production of potato (Solanum tuberosum) by application of vermicompost in a re- claimed sodic soil in India. With good potato growth the sodicity (ESP) of the soil was also reduced from initial 96.74 to 73.68 in just about 12 weeks. The average available nitrogen (N) content of th e soil increased from initial 336.00 kg/h a to 829.33 kg/ha. 11. EARTHWORMS PROTECTS PLANTS AGAINST PESTS AND DISEASES & SIGNIFICANTLY REDUCE USE OF CHEMICAL PESTICIDES Earthworms are both ‘plant growth promoter and pro- tector’. There has been considerable evidence in recent years regarding the ability of earthworms and its vermi- compost to protect plants against various pests and dis- eases either by suppressing or repelling them or by in- ducing biological resistance in plants to fight them or by killing them through pesticidal action. The actinomycetes fungus excreted by the earthworms in their vermicast produce chemicals that kill parasitic fungi such as Py- thium and Fusarium [34]. Another study confirmed that application of vermicompost reduced the damage by stripted cucumber beetle (Acalymma vittatum), spotted cucumber beetle (Diabotrica undecimpunctata) on cu- cumber and larval hornworms (Manduca quinquemacu- lata) on tomatoes in both greenhouse and field experi- ments [50]. 11.1. Ability to Induce Biological Resistance in Plants Vermicompost contains some antibiotics and actinomy- cetes which help in increasing the ‘power of biological resistance’ among the crop plants against pest and di seases. Spray of chemical pesticides was significantly reduced by over 75% where earthworms and vermicompost were used in agriculture [13,16]. 11.2. Ability to Repel Crop Pests There seems to be strong evidence that worms varmi- castings sometimes repel hard-bodied pests [1,33]. Stu- dies reported statistically significant decrease in arthro- pods (aphids, buds, mealy bug, spider mite) populations, and subsequent reduction in plant damage, in tomato, pepper, and cabbage trials with 20% and 40% vermi- compost additions [34]. George Hahn, doing commercial vermicomposting in California, U.S., claims that his product repels many different insects pests. His explana- tion is that this is due to production of enzymes ‘chiti- nase’ by worms which breaks down the chitin in the in- sect’s exoskelton [17]. 11.3. Ability to Suppress Plant Disease Studies reported that vermicompost application sup- pressed 20-40% infection of insect pests i.e. aphids (Myzus persicae), mearly bugs (Pseudococcus spp.) and cabbage white caterpillars (Peiris brassicae) on pepper (Capiscum annuum), cabbage (Brassica oleracea) and tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum) [51]. Studies have also found that use of vermicompost in crops inhibited the soil-born fungal diseases. They also found significant suppression of plant-parasitic nema- todes in field trials with pepper, tomatoes, strawberries and grapes [34]. The scientific explanation behind this concept is that high levels of agronomically beneficial microbial population in vermicompost protects plants by out-competing plant pathogens for available food re- sources i.e. by starving them and also by blocking their excess to plant roots by occupying all the available sites. This concept is based on ‘soil-foodweb’ stu die s pio ne ered by Dr. Elaine Ingham of Corvallis, Oregon, U.S. (http://www.soilfoodweb.com). Edwards and Arancon [27] also reported the disease suppressing effects of applications of vermicompost, on attacks by fungus Pythium on cucumber, Rhizoctonia on radishes in the greenhouse, by Verticillium on strawber- ries and by Phomposis and Sphaerotheca fulginae on grapes in the field. In all these experiments vermicom- post applications suppressed the incidence of the disease significantly. They also found that the ability of patho- gen suppression disappeared when the vermicompost was sterilized, convincingly indicating that the biologi- cal mechanism of disease suppression involved was ‘microbial antagonism. Studies also reported considerable suppression of root knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) and drastic suppression of spotted spider mites (Tetranychus spp.) and aphid (Myzus persicae) in tomato plants after appli-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 83 cation of vermicompost teas (vermiwash liquid) [52]. They are serious pests of several crops. 12. SOME KEY STUDIES SUPPORTING SOIL FERTILITY IMPROVEMENT AND GOOD CROP PRODUCTION BY EARTHWORMS AND VERMICOMPOST OVER CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS There have been several reports that earthworms and its vermicompost can induce excellent plant growth and enhance crop production. 12.1. Cereal Crops Glasshouse studies made at CSIRO Australia found that the earthworms (Aporrectodea trapezoids) increased growth of wheat crops (Triticum aestivum) by 39%, grain yield by 35%, lifted protein value of the grain by 12% & also resisted crop diseases as compared to the control. The plants were grown in a ‘red-brown earth’ with poor nutritional status and 60% moisture. There was about 460 worms m-2 [53]. They also reported that in Parana, Brazil invasion of earthworms significantly altered soil structure and water holding capacity. The grain yields of wheat and soybean increased by 47% and 51%, respectively [54]. Some studies were made on the impact of vermicom- post and garden soil in different proportion on wheat crops in India. It was found that when the garden soil and vermicompost were mixed in 1:2 proportions, the growth was about 72-76% while in pure vermicompost, the growth increased by 82-89% [55]. Another study reported that earthworms & its vermicast improve the growth and yield of wheat by more than 40% [56]. Other studies also reported better yield and growth in wheat crops applied with vermicompost in so il. [57-59]. Studies made on the agronomic impacts of vermi- compost on rice crops (Oryza sativa) reported greater population of nitrogen fixers, actinomycetes and my- corrhizal fungi inducing better nutrient uptake by crops and better growth [60]. Another study was made on the impact of vermicompost on rice-legume cropping system in India. Integrated application of vermicompost, chemi- cal fertilizer and biofertilizers (Azospirillum & phospho- bacteria) increased rice yield by 15.9% over chemical fertilizer used alone. The integrated application of 50% vermicompost, 50% chemical fertilizer and biofertilizers recorded a grain yield of 6.25 and 0.51 ton/ha in the rice and legume respectively. These yields were 12.2% and 19.9% higher over those obtained with 100% chemical fertilizer when used alone [61]. Studies made in the Philippines also reported good response of upland rice crops grown on vermicompost [62]. 12.2. Fruit Crops Study found that worm-worked waste (vermicompost) boosted grape yield by two-fold as compared to chemi- cal fertilizers. Treated vines with vermicompost pro- duced 23% more grapes due to 18% increase in bunch numbers. The yield in grapes was worth additional value of AU $ 3,400/ha [63]. Farmer in Sangli district of Ma- harashtra, India, grew grapes on ‘eroded wastelands’ and applied vermicasting @ 5 tons/ha. The grape harvest was normal with improvement in quality, taste and shelf life. Soil analysis showed that within one year pH came down from 8.3 to 6.9 and the value of potash increased from 62.5 kg/ha to 800 kg/ha. There was also marked improvement in the nutritional quality of the grape fruits [27]. Study was made on the agronomic impacts of vermi- compost and inorganic (chemical) fertilizers on straw- berries (Fragaria ananasa) when applied separately and also in combination. Vermicompost was applied @ 10 tons/ha while the inorganic fertilizers (nitrogen, phos- phorus, potassium) @ 85 (N)-155 (P)-125 (K) kg/ha. Significantly, the ‘yield’ of marketable strawberries and the ‘weight’ of the ‘largest fruit’ was 35% greater on plants grown on vermicompost as compared to inorganic fertilizers in 220 days after transplanting. Also there were 36% more ‘runners’ and 40% more ‘flowers’ on plants grown on vermicompost. Also, farm soils applied with vermicompost had significantly greater ‘microbial biomass’ than the one applied with inorganic fertilizers [7]. Studies also reported that vermicompost increased the yield of strawberries by 32.7% and also drastically reduced the incidence of physiological disorders like albinism (16.1% 4.5%), fruit malformations (11.5% 4%), grey mould (10.4% 2.1%) and diseases like Botrytis rot. By suppressing the nutrient related disor- ders, vermicompost use increased the yield and quality of marketable strawberry fruits up to 58.6% [64]. Studies made on the agronomic impact of vermicom- post on cherries fo und that it increased yield of ‘cherries’ for three (3) years after ‘single application’ inferring that the use of vermicompost in soil builds up fertility and restore its vitality for long time and its further use can be reduced to a minimum after some years of application in farms. At the first harvest, trees with vermicompost yielded an additional $ 63.92 and $ 70.42 per tree re- spectively. After three harvests profits per tree were $ 110.73 and $ 142.21 respectively [65]. 12.3. Vegetable Crops Studies on the production of important vegetable crops  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 84 like tomato (Lycopersicum esculentus), eggplant (So- lanum melangona) and okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) have yielded very good results [27,66-68 ]. Another study was made on the growth impacts of earthworms (with feed materials), vermicompost, cow dung compost and chemical fertilizers on okra (A. esculentus). Worms and vermicompost promoted excellent growth in the vegeta- ble crop with more flowers and fruits development. But the most significant observation was drastically less in- cidence of ‘Yellow Vein Mosaic’, ‘Color Rot’ and ‘Powdery Mildew’ diseases in worm and vermicompost applied plants [69]. Study was made on the production of potato (Solanum tuberosum) by application of vermi- compost in a reclaimed sodic soil in India. The overall productivity of potato was significantly high (21.41 tons/ha) on vermicompost applied @ 6 tons/ha as com- pared to control which was 04.36 tons/ha. The sodicity of the soil was also reduced and nitrogen (N) contents increased significantly [49]. Study was made on the growth impacts of organic manure (containing earth- worm vermicasts) on garden pea (Pisum sativum) and compared with chemical fertilizers. Vermicast produced higher green pod plants, higher green grain weight per plant, higher percentage of protein content and carbohy- drates and higher green pod yield (24.8-91%) as com- pared to chemical fertilizer [70]. Studies made on the effects of vermicompost & chemical fertilizer on hyacinth beans (Lablab purpureas) found that all growth & yield parameters e.g. total chlo- rophyll contents in leaves, dry matter production, flower appearance, length of fruits and fruits per plant, dry weight of 100 seeds, yield per plot and yield per hectare were significantly higher in those plots which received vermicompost either alone or in combination with chemicals. The highest fruit yield of 109 ton/ha was re- corded in plots which received vermicompost @ 2.5 tons/ha [71]. 12.4. Herbage Production A study was made on the impact of earthworms on soil properties and herbage production in a field micro-plot experiment in Ireland. Study site was reclaimed after industrial peat mining, and seeded with perennial rye- grass and clover. The presence of earthworms had little effect on herbage production in the first year. But total herbage yield was 25% greater in the second year and 49% greater in the third year in plots receiving annual topdressing of cattle slurry with earthworms compared to similarly-treated plots with cattle slurry but without earthworms. Ironically, no effect of earthworms on her- bage yield was detected in plots receiving chemical fer- tilizers only [54]. The conclusion drawn from such study is that it is the earthworms in soil which matters in plant productivity and not the organic manure (cattle slurry) alone. In the first year, it took the earthworm to restore and condition the disturbed mined soil. However, the cattle slurry (dung) provided the necessary feed materials for the worms to act with vigor an d excrete nutritive ‘vermicast’ in soil which promoted higher herbage yield in the sec- ond year (25%). In the third year, the worm population in soil increased sign ificantly leading to higher excretion of vermicast, higher soil fertility and higher plant pro- ducti on (49%). In a bucket experiment they found that the cumulative herbage yields over a period of 20 months was 89% higher in buckets with earthworms added with cattle manure as compared to those without earthworms but only with cattle manure, an d only 19% higher in buckets receiving exclusive chemical fertilizers. These results were as compared to control. 13. OUR EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES SUPPORTING EARTHWORMS AND ITS VERMICOMPOST AS SUPERIOR CROP NUTRIENT OVER CONVENTIONAL COMPOST & CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS 13.1. Cereal Crops 13.1.1. Farm Wheat Crops (Agriculture Research Institute, Jaipur, India) This facility was provided by ARI at Jaipur, India. Re- sults are given in Table 4. Key Observ at ion s, F in di ngs and Discussion In the farm experiment the highest growth and yield in wheat crop was achieved where reduced dose (3/4) of chemical fertilizer (NPK- 90:75:60) were supplemented with full dose of vermicompost (@ 2.5 tons/ha. Although vermicom post alone can work as ‘driving force’ but when chemical fertilizers are added as ‘helping hand’ it can do even better. However, the total yield of the grain (grain/ ear) as well as the ear length of crops grown on vermi- compost were as good as those grown on full doses of chemical fertilizers (NPK- 120:100:80). 13.1.2. Farm Wheat Crops (Rajendra Agriculture University, Bihar, India) This facility was provided by RAU, Pusa, India under a collaborative research program. Cattle dung compost was applied four (4) times more than that of vermicom- ost. Results are given in Table 5. p  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/Openly accessible at 85 Table 4. Agronomic impacts of earthworms, vermicompost vis-a-vis chemical fertilizers on farm wheat crops. Treatments Shoot Length (cm) Ear Length (cm)Root Length (cm)Wt. of 1000 grains (In grams) Grains/Ear 1. Vermicompost (@ 2.5 t/ha) 83.71 13.14 23.51 39.28 32.5 2. Earthworms (1000 Nos.) In 25 × 25 m farm land 67.83 9.85 18.42 36.42 30.0 3 NPK (90:75:60) (Reduced Dose) + VC (Full Dose) (2.5 t/ha) 88.05 13.82 29.71 48.02 34.4 4 NPK (120:100:80) (Full Dose) 84.42 14.31 24.12 40.42 31.2 5. CONTROL 59.79 8.91 12.11 34.16 27.7 Source: Ph. D Thesis (Reena Sharma [72]); University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, INDIA; Key: VC = Vermicompost; N = Urea; P = Phosphate; K = Potash (In Kg/hectare). Table 5. Agronomic impacts of vermicompost, cattle dung compost & chemical fertilizers in exclusive applications & in combinations on farmed wheat crops. Treatment Input/Hectare Yield/Hectare 1) CONTROL (No Input) 15.2 Q/ha 2) Vem icompost (VC) 25 Quintal VC/ha 40.1 Q/ha 3) Cattle Dung Compost (CDC) 100 Quintal CDC/ha 33.2 Q/ha 4) Chemical Fertilizers (CF) NPK (120:60:40) kg/ha 34.2 Q/ha 5) CF + VC NPK (120:60:40) kg/ha + 25 Q VC/ha 43.8 Q/ha 6) CF + CDC NPK (120:60:40) kg/ha + 100 Q CDC/ha 41.3 Q/ha Source: Sinha et al. [27]; Key: N = Urea; P = Phosphate; K = Potash (In Kg/ha) Key Observations, Findings & Discussion Exclusive application of vermicompost supported yield comparable to rather better than chemical fertiliz- ers. And when same amount of agrochemicals were sup- plemented with vermicompost @ 25 quintal/ha the yield increased to about 44 Q/ha which is over 28% and nearly 3 times over control. On cattle dung compost applied @ 100 Q/ha (4 times of vermicompost) the yield was just over 33 Q/ha. Application of vermicompost had other agronomic benefits. It significantly reduced the demand for irrigation by nearly 30-40%. Test results indicated better availability of essential micronutrients and useful microbes in vermicompost applied soils. Most remark- able observation was sign ificantly less incid ence of pests and disease attacks in vermicompost applied crops. 13.1.3. Potted Corn Crops (Griffith University, Australia) Study 1: This was designed to compare the agronomic impacts of earthworms, vermicompost & worms with chemical fertilizers on corn plants. Results are given in Table 6. Key Observ at ion s, F in di ngs and Discussion Corn plants with earthworms and vermicompost in soil achieved very good growth and were better over chemical fertilizers studied until week 19. While the plants on chemicals grew only 5 cm (87 cm to 92 cm) in 7 weeks those on vermicompost grew by 15 cm (90 cm to 105 cm) within the same period. But plants with earthworms only (without feed) failed to perform. Most significant finding was that plants on vermicompost de- manded less water for irrigation. Study 2: This was designed to test the growth pro- moting capabilities of earthworms added with feed ma- terials and ‘vermicompost’, as compared to ‘conventional compost’. The doses of vermicompost & conventional compost were ‘doubled’ (400 gm). Crushed dry leaves were used as feed materials (400 gm). Results are given in Table 7. Key Observ at ion s, F in di ngs and Discussion Corn plants with vermicompost in soil achieved rapid and excellent growth and attained maturity very fast. Plants in soil with conventional compost could not achieve maturity until the period of study (week 14). Plants with worms (provided with feed) performed better than those of conventional compost. A significant find- ing was that when the dose of vermicompost was dou- bled from 200 grams (Study 1) to 400 grams (Study 2), it simply enhanced total plant growth to almost two-fold (from average 58 cm on 200 gm vermicompost to aver- age 104 cm on 400 gm vermicompost) within the same period of study i.e. 6 weeks. Corn plants with double dose of vermicompost achieved maturity in much shorter time. However, our subsequent studies on potted and farmed wheat crops showed that once the ‘natural fertil- ity’ of the soil is restored with vermicompost application it no long requires higher doses of vermicompost subse- quently to maintain or enhance productivity [27 ].  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 86 Table 6. Agronomic impacts of earthworms, worms with vermicompost vis-a-vis chemical fertilizers on corn plants (average growth in cm). Parameters Studied CONTROL (No Input) Treatment 1 EARTHWORMS Only (25 Nos.) (Without Feed) Treatment 2 Soluble CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS Treatment 3 EARTHWORMS + VERMICOMPOST (200 gm) Seed Sowing 29th July 2007 Do Do Do Seed Germination 9th Day 7th Day 7th Day 7th Day Avg. Growth in 4 wks 31 40 43 43 Avg. Growth in 6 wks 44 47 61 58 App. Of Male Rep. Organ (In wk 12) None None Male Rep. Organ Male Rep. Organ Avg. Growth in 12 wks 46 53 87 90 App. Of Female Rep. Organ (In wk 14) None None None Female Rep. Organ Avg. Growth in15 wks 48 53 (App. Of Male Rep. Organ)88 95 App. Of New Corn (In wk 16 ) None None None New Corn Avg. Growth in 19 wks 53 56 92 105 Color & Texture of Leaves Pale & thin leaves Green & thin Green & stout leaves Green, stout & broad leaves Source: Sinha et al. [27] Table 7. Agronomic impacts of earthworms (with feed), vermicompost vis-a-vis conventional compost on corn plants (average growth in cm) Parameters Studied Treatment 1 Earthworms (25) With Feed (400 gm) Treatment 2 Conventional COMPOST (400 gm) Treatment 3 VERMICOMPOST (400 gm) Seed Sowing 9th Sept. 2007 Do Do Seed Germination 5th Day 6th Day 5th Day Avg. Growth In 3 wks 41 42 53 Avg. Growth In 4 wks 49 57 76 App. of Male Rep. Organ (In wk 6) None None Male Rep. Organ Avg. Growth In 6 wks 57 70 104 Avg. Growth In 9 wks 64 72.5 120 App. of Female Rep. Organ (In wk 10) None None Female Rep. Organ App. of New Corn (In wk 11) None None New Corn Avg. Growth In 14 wks 82 78 135 Color & Texture of Leaves Green & thick Light green & thin Deep green, stout, thick & broad leaves Source: Sinha et al. [27] 13.1.4. Potted W h e at Crops (Griffith University, Australia) This was designed to compare the agronomic impacts of vermicompost with conventional compost & chemical fertilizers on wheat crops. Results are given in Table 8. Key Observations, Findings & Discussion Wheat crops maintained very good growth on vermin- compost & earthworms from the very beginning & achieved maturity in 14 weeks. The striking rates of seed germination were very high, nearly 48 hours (2 days) ahead  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 87 Table 8. Growth of wheat crops promoted by vermicompost, conventional compost and chemical fertilizers Treatments Week 1 Week 5 Wee k 10 Week 12 1) Control 17 22 26 26 2) CC 17 31 32 32 3) CF 16 36 39 43 4) VC + EW 19 39 43 47 (VC 500 gm; EW 25 Nos.; CC 500 gm; CF 5 gm x 3 times; Av. Growth in cm); Key: CC = Conventional Compost; CF = Chemical Fertilizer; VC = Vermicompost; EW = Earthworms Source: Sinha et al. [27] of others and the numbers of seed germinated were also high by nearly 20%. Plants were greener and healthier over others, with large numbers of tillers & long seed ears were formed at maturity. Seeds were healthy and n early 35-40% more as compared to plants on chemical fertilizers. What they achieved in just 5 weeks, was achieved by others in 10 weeks. More significant was t hat th e po t soil with v er min- compost was very soft & porous and retained more mois- ture. Pot soil with chemicals were hard and demanded more water frequently [27]. 13.2. Vegetable Crops This was designed to compare the growth impacts of earthworms, worms with vermicompost and chemical fertilizers on egg plants. Results are given in Table 9. 13.2.1. Potted Egg Plant s (University of Rajsthan, Jaipur, India 1998 Key Observ at ion s, F in di ngs and Discussion Potted egg-plants grown on vermicompost with live earthworms in soil bored on average 20 fruits/plan t with average weight being 675 gm. Whereas, those grown on chemical fertilizers (NPK) bored only 14 fruits/plant with average weight being only 500 gm. Total numbers of fruits obtained from vermicompost (with worms) ap- plied plants were 100 with maximum weight being 900 gm while those on chemicals were 70 fruits and 625 gm as maximum weight of a fruit. Interestingly, egg-plants grown on exclusive vermicompost (without worms) did not perform as with those with worms, but were signify- cantly better over those on chemical fertilizers. 13.2.2. Potted Okra Plants (University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, India 1998 This was designed to compare the growth impacts of earthworms, worms with vermicompost and chemical fertilizers on okra plants. Results are given in Table 10. Key Observ at io n s, F in di ngs and Discussion Potted okra plants grown on vermicompost (with live worms in soil) bored on average 45 fruits/plant with av- erage weight being 48 gm. Whereas, those grown on chemical fertilizers (NPK) bored only 24 fruits/plant with average weight being only 40 gm. Total numbers of fruits obtained from vermicompost (with worms) applied plants were 225 wit h m a ximum weight being 70 gm while those on chemicals were 125 fruits and 48 gm as maxi- mum weight of a fruit. Again, okra plants grown on ex- clusive vermicompost (without worms) did not perform as with those with worms, but were significantly better over those on chemical fertilizers. 13.2.3. Potted Tomato Plants (Griffith University, Australia 2009) This was designed to compare the agronomic impacts of vermicompost & worms with composted cow manure from market & chemical fertilizers on tomato plants. Results are given in Table 11. Key Observ at ion s, F in di ngs and Discussion Tomato plants on vermicompost & vermicompost with worms maintained very good gro wth fro m the very beginning. Number of flowers and fruits per plant were also significantly high as compared to those on agro- chemicals and conventional compost. Presence of earth- worms in soil made a significant difference in ‘flower and fruit formation’ in tomato plan ts. Th is was obv iously Table 9. Agrono mic im pacts of vermicom post, ea rthworms & verm icompost vi s-a-vis chem ical f ertilizer on growth & dev elopment of egg plants. Treatments Av. Vegetative Growth (In Inches)Av. No. of Fruits/Plant Av. Wt. of Fruits/Plant Total No. of Fruits Max. Wt. of One Fruit 1. Earthworms (50 Nos.) + VC * (250 gm) 28 20 675 gm 100 900 gm 2. Vermicompost (250 gm) 23 15 525 gm 75 700 gm 3. Chemical Fertilizer (NPK) (Full dose) 18 14 500 gm 70 625 gm 4. CONTROL 16 10 425 gm 50 550 gm (N.B. Value of vegetative growth was taken that was achieved on the 90th day of the study, while the fruiting was estimated from the 45th day & end- ing with over 120 days); Source: Sinha et al. [27]; Key: VC = Vermicompost  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 88 Table 10. Agronomic impacts of vermicompost, worms with vermicompost vis-a-vis chemical fertilizer on growth & development of okra plants. Treatment Av. Vegetative Growth (In Inches) Av. No. of Fruits/Plant Av. Wt. of Fruits/Plant To tal No. of Fruits Max. Wt. of One Fruit 1. Earthworms (50 Nos.) + VC* 39.4 45 48 gm 225 70 gm 2. Vermicompost (250 gm) 29.6 36 42 gm 180 62 gm 3. Chemical Fertilizer (NPK) (Full dose) 29.1 24 40 gm 125 48 gm 4. CONTROL 25.6 22 32 gm 110 43 gm (N.B. Value of vegetative growth was taken that was achieved on the 90th day of the study, while the fruiting was estimated after 45th day and ending with over 120 days); Source: Sinha et al. [27] Ta ble 11. Growth of tomato plants promoted by vermicompost, vermicompost with earthworms, conventional compost (composted cow manure) & chemical fertilizers (All seedlings measured 5 cm; Average growth in cm). Parameters Studied Control Chemical Fertilizers (5 gm × 3 times) Composted Cow Manure (500 gm) Vermicompost (250 gm) Vermicompost (250 gm) + Earthworms (50) 1).Avg. Growth in 2 Wks. 10 16 16 18 19 2). Avg. Growth in 4 Wks. 30 49 35 60 60 3). Number of flowers (Wk.5) 8 17 10 27 31 4). Avg. Growth in 6 Wks. 40 70 51 118 125 5). Avg. Growth in 8 Wks. 48 108 53 185 188 6). Number of fruits (Wk. 9) 4 16 6 22 27 7). Avg. Growth after 10 Wks. 50 130 53 207 206 Source: Sinha & Valani [27] due to more ‘growth & flowering hormones’ (auxins and gibberlins) available in the soil secreted by live earth- worms. Very disappo inting was the results of composted cow manure obtained from the market with branded name. It could not compete with vermicompost (indige- nously prepared from food waste) even when applied in ‘double dose’. 14. VERMIWASH: A NUTRITIVE GROWTH PROMOTING PESTICIDAL LIQUID PRODUCED DURING VERMICOMPOST PRODUCTION The brownish-red liquid which collects in all vermcom- posting practices is also productive and protective for farm crops. This liquid partially comes from the body of earthworms (as worm’s body contain plenty of water) and is rich in amino acids, vitamins, nutrients like nitro- gen, potassium, magnesium, zinc, calcium, iron and cop- per and some growth hormones like ‘auxins’, ‘cytokinins’. It also contains plenty of nitrogen fixing and phosphate solubilising bacteria (nitrosomonas, nitrobacter and ac- tinomycetes). Vermiwash has great ‘growth promoting’ as well as ‘pest killing’ properties. Study reported that weekly application of vermiwash increased radish yield by 7.3% [73,74]. Another study also reported that both growth and yield of paddy increased with the application of vermiwash and vermicast extracts [75]. Farmers from Bihar in North India reported growth promoting and pesticidal properties of this liquid. They used it on brinjal and tomato with excellent results. The plants were healthy and bore bigger fruits with unique shine over it. Spray of vermiwash effectively controlled all incidences of pests and diseases, significantly re- duced the use of chemical pesticides and insecticides on vegetable crops and the products were significantly dif- ferent from oth ers wi t h hi g h m a rket val ue. George [76] studied the use of vermiwash for the management of ‘Thrips’ (Scirtothrips dorsalis) and ‘Mites’ (Polyphagotarsonemus latus) on chilli amended with vermicompost to evaluate its efficacy against thrips  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 89 and mites. Vermiwash was used in three different dilu- tions e.g. 1:1, 1:2 and 1:4 by mixing with water both as ‘seedling dip’ treatment and ‘foliar spray’. Six rounds of vermiwash sprays were taken up at 15 days interval commencing at two weeks after transplanting. Among the various treatments, application of vermicompost @ 2.5 ton/ha with 6 sprays of vermiwash at 1:1 dilution showed significantly lower incidence of thrips and mites attack. It registered very low mean population of thrips and mites as 0.35 and 0.64 per leaf respectively. It also registered significantly maximum dry chilli yield @ 2.98 quintal/ha. Giraddi et al. [74] also reported significantly lower pest population in chilli applied with vermiwash (soil drench 30 days after transplanting, and foliar spray at 60 and 75 days after transplanting) as compared to untreated crops. Suthar [77] has reported hormone like substances in vermiwash. He studied its impact on seed germination, root & shoot length in Cyamopsis tertagonoloba and compared with urea solution (0.05%). Maximum germi- nation was 90% on 50% vermiwash as compared to 61.7% in urea solution. Maximum root and shoot length was 8.65 cm & 12.42 cm on 100% vermiwash as com- pared to 5.87 & 7.73 on urea. The seedlings with 100% vermiwash foliar spray showed the maximum level of total protein and soluble sugars in their tissues. 15. AMOUNT & APPLICATION TIME OF VERMICOMPOST IN CROPS Vermicompost can be used in any crop and in any amount as it is ‘completely safe’ for soils and crops in all amounts. However, several studies including ours, indi- cate that vermicompost is required in much ‘lesser amount’ as compared to all other bulky organic fertiliz- ers e.g. composted cattle dung (cow, horse & pig ma- nures and sheep & goat droppings) composted MSW and composted plant residues to promote optimal growth and yield. This is because they contain ‘high nutrients with growth hormones’ and are 4-5 times more powerful growth promoters than all other organic fertilizers and over 30-40% higher over the chemical fertilizers (NKP). Study made by Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad, India have provided a report which is given in Table 12. 16. THE GLOBAL MOVEMENT FOR USE OF VERMICOMPOST TO REPLACE DESTRUCTIVE CHEMICAL FERTIL- IZERS FROM AGRICULTURE Worldwide farmers are desperate to get rid of the vicious Table 12. Recommended quantity and time of application of vermicompost in some crops. Crop Quantity Time of Application 1). Rice (Paddy) 1 ton/acre After Transplanting 2). Maize (Corn) 1 ton/acre Last Ploughing 3). Sugarcane 1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 4). Groundnut 0.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 5). Sunflower 1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 6). Chilli 1 ton/acre Last Plo u g h ing 7). Potato 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 8). To mato 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 9). Brinjal 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 10). Okra 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 11). Cauliflowers 1-1.5 to n/acre Last Ploughing 12). Cabbage 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 13). Garlic 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 14). Onion 1-1.5 ton/acre Last Ploughing 15). Grape (Vineyards) 1 ton/acre Summer time 16). Citrus 2 kg/tree At planting time & before flowering 17). Pomegranate 2 kg/tree At planting time & before flowering 18). Guava 2 kg/tree At planting time & before flowering 2 kg/tree A t plant ing time 5 kg/tree 1-5 years old trees 10 kg/tree 6-9 years old trees 19). Mango & Coconut 20 kg/tree Trees older than 10 years 20). Cotton 1 ton/acre Last Ploughing Source: CRIDA (2009), Hyderabad, India [78] circle of the use of chemical fertilizers as their cost hav e been constantly rising and also the amount of chemicals used per hectare has been steadily increasing over the years to maintain the yield & productivity of previous years. Nearly 3-4 times of agro-chemicals are now be- ing used per hectare what was used in the 1960s. In Australia, the cost of MAP fertilizer has risen from AU $ 530.00 to AU $ 1500.00 per ton since 2006. So is the story everywhere in world because the chemical fertiliz- ers are produced from ‘vanishing resources’ of earth. Farmers urgently need a sustainable alternative which is both economical and also productive while also main- taining soil health & fertility. The new concept is ‘Eco- logical Agriculture’ which is by definition different from  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 90 ‘Organic Farming’ that was focused mainly on produc- tion of chemical-free foods. Ecological agriculture em- phasize on total protection of food, farm & human eco- systems while improving soil fertility & development of secondary source of income for the farmers. UN has also endorsed it. Vermiculture provides the best answer for ecological agriculture which is synonymous with ‘sus- tainable agriculture’. A movement is going on in India, China, Philippines, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Australia, U.S., Canada, Rus- sia and Japan to vermicompost the organic fractions of all their municipal solid wastes (MSW) and among the farmers to vermicompost their farm wastes and use them as a complete ‘organic fertilizer ’ for crops as an alterna- tive to the chemical fertilizers or supplement them with highly reduced doses of chemical fertilizers. Municipal councils, NGOs and composting companies are also participating in vermicomposting business, composting all types of organic wastes on commercial scale and selling them to the farmers. This has dual benefits. Cut- ting cost on landfill disposal of waste while earning revenues from sale of worms & vermicompost [17, 27,79]. ‘Vermicycle Organics’ in the U.S. produces 7.5 million pounds of vermicompost every year in high-tech greenhouses and sell to the farmers. Its sale of vermi- compost grew by 500% in 2005. ‘Vermitechnology Un- limited’ in U.S. has doubled its business every year since 1991 [80]. A ‘Vermiculture Movement’ is going on in India with multiple objectives of community waste management, highly economical way of crop production replacing the costly chemical fertilizers and poverty eradication pro- grams in villages [81]. 17. IMPORTANT FEEDBACKS FROM FARMERS USING VERMICOMPOST IN INDIA Farmers in India are being motivated to embrace ver- miculture in farming. This is mainly in the States of Karanatka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Punjab, Harayana, Himachal Pradesh and Bihar. Apple growers in Himachal are using vermicompost on large scale with very good profit. A number of villages in the districts of Samastipur, Hazipur and Nalanda in the State of Bihar have been designated as ‘Bio-Village’ where the farmers have completely switched over to organic farming by ver- micompost and h ave given up the use of che mical fertil- izers since 2005. Some of them asserted to have har- vested three (3) different crops in a year (reaping 2-3 times more harvest) due to their rapid growth & maturity, and reduced harvest cycle. (Authors takes pride in moti- vating farmers in Bihar through personal contacts under a collaborative research program between Griffith Uni- versity, Australia and Rajendra Agriculture University, Bihar). Some of the important revelation by farmers about use of vermicompost were 1) Reduced use of ‘water for irrigation’; 2) Reduced ‘pest attack’ (by at least 75%) especially after spray of vermiwash (liquid drained during vermi- composting); 3) Reduced ‘termite attack’ in farm soil especially where worms were in good population; 4) Reduced ‘weed growth’; 5) Faster rate of ‘seed germination’ and rapid seed- lings growth and development; 6) Greater numbers of fruits per plant (in vegetable crops) and greater numbers of seeds per ear (in cereal crops), heavier in weight—better in both, quantity and quality as compared to those grown on chemicals; 7) Fruits and vegetables had ‘better taste’ and texture and could be safely stored up to 6-7 days, while those grown on chemicals could be kept at the most for 2-3 days; 8) Fodder growth was increased by nearly 50% @ 30 to 40 quintal/hectare; 9) Flower production (commercial floriculture) was increased by 30%-50% @ 15-20 quintal/hectare. Flower blooms were more colorful and bigger in size; 18. ENVIRONMENTAL-ECONOMICS OF FOOD PRODUCTION BY VERMICOMPOST VIS-À-VIS CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS A matter of considerable economic and environmental significance is that the ‘cost of food production’ by ver- micompost (produced locally on-farm from organic wastes diverted from landfill disposal at high cost) will be significantly low by more than 60-70% as compared to chemical fertilizers (produced in factories from van- ishing petroleum products using huge electricity) and the food produced will be a ‘safe chemical-free food’ for the society. Due to enhanced colour, taste, smell and flavour of food products f armers gets higher price for their farm products. It is a ‘win-win’ situation for both producers (farmers) and the consumers (feeders). And with the growing global popularity of ‘organic foods’ which became a US $ 6.5 billion business every year by 2000, there will be great demand for vermicom- post in future. US Department of Agriculture estimates 25% of Americans purchase organically grown foods at least once a week. The cost of production of vermicom-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 91 post is simply insignificant as compared to chemical fertilizers. While the vermicompost is produced from ‘human waste’—a raw material which is in plenty all over the world, chemical fertilizers are obtained from ‘petroleum products’ which is a vanishing resource on earth. Vermicompost can be produced ‘on-farm’ at low- cost by simple devices, while the ch emical fertilizers are high-tech & high-cost products made in factories [17, 82]. Use of vermicompost in farm soil eventually leads to increase in the number of earthworm population in the farmland over a period of time as the baby worms grow out from their cocoons. It infers that slowly over the years, as the worms build up the soil’s physical, chemi- cal & biological properties, the amount of vermicompost can be slowly reduced while maintainin g the same yield. The yield per hectare may also increase further as the soil’s natural fertility is restored & strengthened. On the contrary, in chemical agriculture, the amount of chemi- cals used per hectare has been steadily increasing over the years to maintain the same yield as the soil became ‘addict’. Nearly 3-4 times of agro-chemicals are now being used per hectare what was use d in the 19 6 0s. Vermicompost is able to retain more soil moisture and also protects crops from pests & diseases thus reducing the demand of water for irrigation by nearly 30-40% and pest & disease control by almost 75%. This significantly cut down on the cost of production. As it also helps the crops to attain maturity and reproduce faster, it shortens the ‘harvesting time’. This further cuts on the cost of production and also adds to the economy of farmers as they can grow more crops every year in the same farm plot. While vermicompost production & use is an ‘envi- ronmentally friendly’ practices (salvaging waste & im- proving soil properties), production of chemical fertiliz- ers is ‘environmentally damaging’ (generating hazardous wastes & pollutants and greenhouse gases) in its entire life-cycle, since harnessing of raw materials from the earth crust, to their processing in factories (generating huge waste and pollution) and application in farms (pol- luting soil & killing beneficial organisms) with severe economic & environmental implications. Production and use of 1 kg of chemical nitrogen fertilizer emits 2,500 gm of CO2, 10 gm N2O & 1 gm CH4. Molecule to molecule, N2O and CH4 are 310 & 22 times more pow- erful GHG than CO2. Earthworms converts a product of ‘negative’ economic & environmental value i.e. ‘waste’ into a product of ‘highly positive’ economic & environ- mental values i.e. ‘highly nutritive organic fertilizer’ (brown gold) and ‘safe food’ (green gold). Vermiculture can maintain the global ‘human sustainability cycle’— producing food back from food & farm wastes. Earthworms biomass comes as a valuable by-product in all vermicomposting practices and they are good source of nutritive ‘worm meal’. They are rich in pro- teins (65%) with 70-80% high quality essential amino acids ‘lysine’ and ‘methionine’ and are being used as feed material to promote ‘fish ery’ and ‘poultry’ industry. They are also finding new use as a source of ‘bioactive compounds’ (enzymes) for production of modern medi- cines for cardiovascular diseases and cure for cancer in the making of ‘antibiotics’ from the ceolomic fluid as it has anti-pathogenic properties. On commercial scale tons of worm biomass can result every year as under favorable conditions worms ‘double’ their number at least every 60-70 days. If vermi-products (worms, vermicompost & vermi- wash) are able to replace agrochemicals in food produc- tion and protein rich worms provide nutritive feeds for fishe ry an d pou ltry produ ction it wo uld t ruly help achie ve greater sustainability in production of ‘safe food’ for mankind in future [83,84]. 19. CONCLUSIONS AND REMARKS Our studies and those of other learned authors have con- clusively proved that earthworms and its excreta (ver- micast) or even its body fluids (vermiwash) have tre- mendous crop growth promoting and protecting potential and may work as the main ‘driving force’ in sustainable food production while maintaining soil health and fertil- ity and can completely replace the use of agro-chemicals from farm production or just require them as ‘helping hand’ [83,84]. Vermicompost also reinforce plants phy- siologically to attain maturity and reproduce faster, thus reducing the ‘life-cycle’ of crops and also shortening the ‘harvesting time’. Reduced incidence of ‘pest and dis- ease attack’, ‘controlling pests without pesticides’ and ‘better taste of chemical-free organic food pr oducts esp e- cially ‘fruits and vegetables’ grown with earthworms and vermicompost are matter of great socio- economic and environmental significance. In case of fruits and vegetable crops presence of earthworms in soil make a big difference in growth per- formance. It looks worms have more positive impacts on flowering of horticultural crops and significantly aid in fruit development obviously due to secretion of growth hormones ‘auxins’ and ‘gibberlins’ [22,69,85]. No won- der then, Surpala, in 10th century A.D. recommended to add earthworms in pomegranate plants to obtain good fruits. Use of vermicompost in farm soil eventually leads to increase in the number of earthworm population in the farmland over a period of time as the baby worms grow out from their cocoons. Slowly over the years, as the  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 92 worms & vermicompost build up the soil’s physical, chemical and biological properties of soil and restore its natural fertility, reduced amount of vermicompost will be required to maintain productivity. This is contrary to those with chemical fertilizers whose amount of use has gradually increased over the years. More studies is required to develop the potential of ver- micompost teas (vermiwash) as a sustainable, non-toxic and environmentally friendly alternative to ‘chemical pest control’ or at least its application in farming prac- tices can also lead to significant reduction in use of chemical pesticides. Earthworms are truly justifying the beliefs and fulfill- ing the dreams of Sir Charles Darwin who called earth- worms as ‘unheralded soldiers’ of mankind’ and ‘friends of farmers’. It is also justifying the beliefs of Dr. Anatoly Igonin one of the great contemporary vermiculture sci- entist from Russia who said ‘Earthworms create soil & improve soil’s fertility and provides critical biosphere’s functions: disinfecting, neutralizing, protective and pro- ductive’ [86]. REFERENCES [1] Arancon, N. (2004) An interview with Dr. Norman Ar- ancon. Casting C a ll, 9(2), http://www.vermico. com [2] US Board of Agriculture, (1980) Report and recom- mendations on organic farming—case studies of 69 or- ganic farmers in USA. Publication of U.S. Board of Ag- riculture. [3] Kale, R.D. (1998) Earthworm cinderella of organic far- ming. Prism Book Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, 88. [4] Martin, J.P. (1976) Darwin on earthworms: The forma- tion of vegetable moulds. Bookworm Publishing, On- tario. [5] Satchell, J.E. (1983) Earthworm ecology-from darwin to vermiculture. Chapman and Hall Ltd., London. [6] Sadhale, N. (1996) Recommendation to incorporate earthworms in soil of pomogranate to obtain high quality fruits. Surpala’s Vrikshay urveda, Verse 131. The Science of Plant Life by Surpala, 10th Century A.D. Asian Agri-History Bulletin, Secunderabad. [7] Bhat, J.V. and Khambata, P. (1996) Role of earthworms in agriculture. Pub. Of Indian Council of Agriculture Re- search (ICAR), 22, New Delhi, India, 36. [8] Ghabbour, S.I. (1973) Earthworm in agriculture: A mod- ern evaluation. Indian Review of Ecological and Bio- logical Society, 111(2), 259-271. [9] Capowiez, Y., Cadoux S., Bouchand P., Roger-Estrade, J., Richard G. and Boizard, H. (2009) Experimental evi- dence for the role of earthworms in compacted soil re- generation based on field observations and results from a semi-field experiment. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 41(4), 711-717. [10] Li, K.M. (2005) Vermiculture Industry in Circular Economy, Worm Digest. http://www.wormdigest.org/con tent/view/135/2/ [11] Bhawalkar, V.U. and Bhawalkar, U.S. (1993) Vermicul- ture: The bionutrition system. national seminar on in- digenous technology for sustainable agriculture. Indian Agriculture Research Institute (IARI), New Delhi, 1-8. [12] Bombatkar, V. (1996) The miracle called compost. The Other India Press, Pune. [13] Singh, R.D. (1992) Harnessing the earthworms for sus- tainable agriculture. Publication of Institute of National Organic Agriculture, Pune, 1-16. [14] Ayres, M. (2007) Suppression of soil—born plant disease using compost. 3rd National Compost Research and De- velopment Forum Organized by COMPOST Australia, Murdoch University, Perth. Ayres. Matthew@saugov.sa. gov.au [15] Webster, K. (2007) Compost as part of a vineyard salinity remediation strategy. 3rd National Compost Research and Development Forum Organized by COMPOST Aus- tralia, Murdoch University, Perth. www.compostforsoils. com.au [16] Suhane, R. K. (2007) Vermicompost. Publication of Ra- jendra Agriculture University, Pusa, Bihar, India, 88. info@kvksmp.org [17] Munroe, G. (2007) Manual of On-farm Vermicomposting and Vermiculture. Publication of Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada, Nova Scotia. [18] Pajon, S. (2007) The Worms Turn-Argentina. Intermedi- ate Technology Development Gr oup. Case Study Series 4; Quoted in Munroe. http:// www.tve.org./ho/doc.cfm?aid= 1450&lang=Engl ish [19] Canellas. L.P., Olivares, F.L., Okorokova, A.L. and Fa- canha, R.A. (2002) Humic Acids Isolated from Earth- worm Compost Enhance Root Elongation, Lateral Root Emergence, and Plasma Membrane H+ - ATPase Activity in Maize Roots. Journal of Plant Physiology, 130(4), 1951-1957. [20] Pierre, V, Phillip, R. Margnerite, L. and Pierrette, C. (1982) Anti-bacterial activity of the haemolytic system from the earthworms Eisinia foetida Andrei. Invertebrate Pathology, 40(1), 21-27. [21] Atiyeh, R.M., Subler, S., Edwards, C.A., Bachman, G., Metzger, J.D. and Shuster, W. (2000) Effects of Vermi- composts and Composts on Plant Growth in Horticultural Container Media and Soil. Pedobiologia, 44(5), 579-590. [22] Agarwal, S. (1999) Study of vermicomposting of domes- tic waste and the effects of vermicompost on growth of some vegetable crops. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ra- jasthan, Jaipur. [23] Tognetti, C., Laos, F., Mazzarino, M.J. and Hernandez, M.T. (2005) Composting vs. vermicomposting: A com- parison of end product quality. Journal of Compost Sci- ence & Utilization, 13(1), 6-13. [24] Sinha, R. K. and Gokul, B. (2007) Vermiculture revolu- tion: rapid composting of waste organics with improved compost quality for healthy plant growth while reducing ghg emissions. 3rd National Compost Research and De- velopment Forum Organized by COMPOST Australia, Murdoch University, Perth. http:// www. compostforsoils. com.au [25] Jadia, C.D. and Fulekar, M.H. (2008) Vermicomposting of vegetable wastes: A biophysiochemical process based on hydro-operating bioreactor. African Journal of Bio- technology, 7(20), 3723-3730.  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessi ble at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 93 [26] Reganold, J.P., Papendick, R.I.P. and James, F. (1990) Sustainable Agriculture. Scientific American, 262(6), 112-120. [27] Sinha, R.K., Herat, S., Valani, D. and Chauhan, K. (2009) Vermiculture and sustainable agriculture. American- Eurasian Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Sci- ences; IDOSI Publication, 1-55. www.idosi.org [28] Scheu, S. (1987) Microbial activity and nutrient dynam- ics in earthworms casts. Journal of Biological Fertility Soils, 5(3), 230-234. [29] Binet, F., Fayolle, L. and Pussard, M. (1998) Signifi- cance of earthworms in stimulating soil microbial activity. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 27(2), 79-84. [30] Chaoui, H.I., Zibilske, L.M. and Ohno, T. (2003) Effects of earthworms casts and compost on soil microbial activ- ity and plant nutrient availability. Soil Biology and Bio- chemistry, 35(2), 295-302. [31] Tiwari, S.C., Tiwari, B.K. and Mishra, R.R. (1989) Mi- crobial populations, enzyme activities and nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium enrichment in earthworm casts and in surrounding soil of a pineapple plantation. Journal of Biological Fertility of Soils, 8(1), 178-182. [32] Kale, R.D. and Bano, K. (1986) Field trials with vermi- compost, an organic fertilizer. Proceeding of National Seminar on ‘Organic Waste Utilization by Vermicom- posting, GKVK Agricultural University, Bangalore. [33] Anonymous (2001) Vermicompost as Insect Repellent. Biocycle. [34] Edwards, C.A. and Arancon, N. (2004) Vermicompost Supress Plant Pests and Disease Attacks. Rednova News, http://www.rednova.com/display/ [35] Rodríguez, J.A., Zavaleta, E., Sanchez, P. and Gonzalez, H. (2000) The effect of vermicompost on plant nutrition, yield and incidence of root and crown rot of Gerbera (Gerbera jamesonii H Bolus). Fitopathologia, 35(2), 66-79. [36] Buchanan, M.A., Russel, E. and Block, S.D. (1988) Chemical characterization and nitrogen mineralisation potentials of vermicompost derived from differing or- ganic wastes. In: Edward, C.A. and Neuhauser, E.F., Eds., Earthworms in Waste and Environmental Management, SPB Academic Publ i s hing, The Hague, 231-240. [37] Patil, B.B. (1993) Soil and Organic Farming. Proceeding of the Training Program on ‘Organic Agriculture, Insti- tute of Natural and Organic Agriculture, Pune. [38] Barley, K.P. and Jennings A.C. (1959) Earthworms and soil fertility III; The influence of earthworms on the availability of nitrogen. Australian Journal of Agricul- tural Research, 10(3), 364-370. [39] Dash, M.C. and Patra, U.C. (1979) Worm cast production and nitrogen contribution to soil by a tropical earthworm population from a grassland site in Orissa. Indian Review of Ecological and Biological Society, 16(4), 79-83. [40] Whalen, J.K., Parmelee, W.R., McCartnney, A.D. and Vanarsdale, J.L. (1999) Movement of nitrogen (n) from decomposing earthworm tissue to soil microbial and ni- trogen pools. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 31(4), 487-492. [41] Lee, K.E. (1985) Earthworms, their ecology and rela- tionships with soil and land use. Academic Press, Syd- ney. [42] Satchel, J.E. and Martin, K. (1984) Phosphatase activity in earthworm feces. Journal of Soil Biology and Bio- chemistry, 16(2), 191-194. [43] Li, K. and Li, P.Z. (2010) Earthworms helping economy, improving ecology and protecting health. In: Sinha, R.K. et. al., Eds. Special Issue on ‘Vermiculture Technology’, International Journal of Environmental Engineering, In- derscience Pub. (Accepted). [44] Tomati, V., Grappelli, A. and Galli, E. (1985) Fertility factors in earthworm humus. Proceedings of Interna- tional Symposium on ‘Agriculture and Environment: Prospects in Earthworm Farming, Rome, 49-56. [45] Edwards, C.A. and Burrows, I. (1988) The potential of earthworms composts as plant growth media. In: Edward, C.A. and Neuhauser, E.F. Eds., ‘Earthworms in Waste and Environmental Management’, SPB Academic Pub- lishing, The Hague, 21-32. [46] Neilson, R.L. (1965) Presence of plant growth substances in earthworms. Nature, 208(5015), 1113-1114. [47] Tomati, U. Grappelli, A. and Galli, E. (1987) The Pres- ence of Growth Regulators in Earthworm-Worke d Wastes. Proceeding of International Symposium on ‘Earthworms’, Bologna-Carp i, 423-436. [48] Tomati, V., Grappelli, A. and Galli, E. (1995) The Hor- mone like Effect of Earthworm Casts on Plant Growth. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 5(4), 288-294. [49] Ansari, A.A. (2008) Effect of Vermicompost on the Pro- ductivity of Potato (Solanum tuberosum) Spinach (Spin- acia oleracea) and Turnip (Brassica campestris). Wor ld Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 4(3), 333-336. [50] Yardim, E.N., Arancon, N.Q., Edwards, C.A., Oliver, T.J. and Byrne, R.J. (2006) Suppression of tomato hornworm (Manduca quinquemaculata) and cucumber beetles (Aca- lymma vittatum and Diabotrica undecimpunctata) popu- lations and damage by vermicomposts. Pedobiologia, 50(1), 23-29. [51] Arancon, N.Q., Edwards, C.A. and Lee, S. (2002) Man- agement of plant parasitic nematode population by use of vermicomposts. Proceedings of Brighton Crop Protec- tion Conference-Pests and Diseases, Brighton, 2002, 705-716. [52] Edwards, C.A., Arancon, N.Q., Emerson, E. and Pulliam, R. (2007) Suppressing plant parasitic nematodes and ar- thropod pests with vermicompost teas. BioCycle, 48(12), 38-39. [53] Baker, G.H., Williams, P.M., Carter, P.J. and Long, N.R. (1997) Influence of lumbricid earthworms on yield and quality of wheat and clover in glasshouse trials. Journal of Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 29(3/4), 599-602. [54] Baker, G.H., Brown, G., Butt K., Curry, J.P. and Scullion, J. (2006) Introduced earthworms in agricultural and re- claimed land: Their ecology and influences on soil prop- erties, plant production and other soil biota. Biological Invasions, 8(6), 1301-1316. [55] Krishnamoorthy, R.V. and Vajranabhaiah, S.N. (1986) biological activity of earthworm casts: An assessment of plant growth promoter levels in the casts. Proceedings of Indian Academy of Sciences (Animal Science), 95(3), 341-351. [56] Palanisamy, S. (1996) Earthworm and plant interactions. ICAR Training Program, Tamil Nadu Agricultural Uni- versity, Coimbatore. [57] Roberts, P, Jones, G.E. and Jones, D.L. (2007) Yield re-  R. K. Sinha et al. / Agricultura l Sciences 1 (2010) 76-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/Openly accessible at 94 sponses of wheat (Triticum aestivum) to vermicompost. Journal of Compost Science and Utilization, 15(1), 6-15. [58] Suthar, S. (2005) Effect of vermicompost and inorganic fertilizer on wheat (Triticum aestivum) production. Na- ture Environment Pollution Technology, 5(2), 197-201. [59] Suthar, S. (2010) Vermicompost: An environmentally safe, economically viable and socially acceptable nutri- tive fertilizer for sustainable farming; In: Sinha, R.K. et al., Eds. Special Issue on ‘Vermiculture Technology, Journal of Environmental Engineering; Inderscience Pub. (Accepted). [60] Kale, R.D., Mallesh, B.C., Kubra, B. and Bagyaraj, D.J. (1992) Influence of vermicompost application on the available macronutrients and selected microbial popula- tions in a paddy field. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 24(12), 1317-1320. [61] Jeyabal, A. and Kuppuswamy, G. (2001) Recycling of organic wastes for the production of vermicompost and its response in rice—legume cropping system and soil fertility. European Journal of Agronomy, 15(13), 153- 170. [62] Guerrero, R.D. and Guerrero, L.A. (2008) Effect of ver- micompost on the yield of upland rice in outdoor con- tainers. Asia Life Sciences, 17(1), 145-149. [63] Buckerfield, J.C. and Webster, K.A. (1998) Worm- worked waste boost grape yield: Prospects for vermi- compost use in vineyards. The Australian and New Zea- land Wine Industry Journal, 13(1), 73-76. [64] Singh, R., Sharma, R.R., Kumar, S., Gupta, R.K. and Patil, R.T. (2008) Vermicompost substitution influences growth, physiological disorders, fruit yield and quality of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch), Bioresource Technology, 99(17), 8507-8511. [65] Webster, K.A. (2005) Vermicompost increases yield of cherries for three years after a single application. EcoR e- search, South Australia. http://www.ecoresearch.com.au [66] Atiyeh, R.M., Subler, S., Edwards, C.A. and Metzger, J.D. (1999) Growth of Tomato Plants in Horticultural Potting Media Amended with Vermicompost. Pedobiolo- gia, 43(4), 1-5. [67] Gupta, A.K., Pankaj, P.K. and Upadhyava, V. (2008) Effect of vermicompost, farm yard manure, biofertilizer and chemical fertilizers (N, P, K) on growth, yield and quality of lady’s finger (Abelmoschus esculentus). Pollution Re- search, 27(1), 65-68. [68] Guerrero, R.D. and Guerrero, L.A. (2006) Response of eggplant (Solanum melongena) grown in plastic contain- ers to vermicompost and chemical fertilizer. Asia Life Sciences, 15(2), 199-204. [69] Agarwal, S, Sinha, R.K. and Sharma, J. (2010) Ver- miculture for sustainable horticulture: Agronomic impact studies of earthworms, cow dung compost and vermi- compost vis-à-vis chemical fertilizers on growth and yield of lady’s finger (Abelmoschus esculentus). In: Sinha, R.K. et al., Eds., Special Issue on ‘Vermiculture Technology’, International Journal of Environmental Engineering, Inderscience Pub. [70] Meena, R.N., Singh, Y., Singh, S.P., Singh, J.P. and Singh, K. (2007) effect of sources and level of organic manure on yield, quality and economics of garden pea (Pisum sa- tivam L.) in eastern uttar pradesh. Vegetable Science, 34(1), 60-63. [71] Karmegam, N. and Daniel, T. (2008) Effect of vermi- compost and chemical fertilizer on growth and yield of Hyacinth Bean (Lablab purpureas). Dynamic Soil, Dy- namic Plant, Global Science Books, 2(2), 77-81. kanishka rmegam@gmail.com [72] Sharma, R. (2001) Vermiculture for sustainable agricul- ture: study of the agronomic impact of earthworms and their vermicompost on growth and production of wheat crops, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur. [73] Buckerfield, J.C., Flavel, T.C., Lee, K.E. and Webster, K.A. (1999) Vermicompost in solid and liquid forms as a plant—growth promoter. Pedobiologia, 43(6), 753-759. [74] Giraddi, R.S. (2003) Method of extraction of earthworm wash: A plant promoter substance. VIIth National Sympo- sium on Soil Biology and Ecology, Bangalore. [75] Thangavel, P., Balagurunathan, R., Divakaran, J. and Prabhakaran, J. (2003) effect of vermiwash and vermi- cast extract on soil nutrient status, growth and yield of paddy. Advances of Plant Sciences, 16(1), 187-190. [76] Saumaya, G., Giraddi, R.S. and Patil, R.H. (2007) Utility of vermiwash for the management of thrips and mites on chilli (capiscum annum) amended with soil organics. Karnataka Journal of Agriculture Sciences, 20(3), 657- 659. [77] Suthar, S. (2010) Evidence of plant hormone like sub- stances in vermiwash: An ecologically safe option of synthetic chemicals for sustainable farming. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 36(8), 1089-1092. [78] CRIDA (2009) Vermicompost from Waste; Pub. Of Cen- tral Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture; Hydera- bad, (Unit of Indian Council for Agricultural Research). [79] Lotzof, M. (2000) Vermiculture: An Australian Technology Success Story. Waste Management Magazine. [80] NCSU (1997) Large Scale Vermi-composting Operations —Data from Vermicycle Organics, Inc., North Carolina State University, Raleigh. [81] White, S. (1997) A Vermi-adventure in India. Journal of Worm Digest, 15(1), 27-30. [82] Bogdanov, P. (2004) The single largest producer of ver- micompost in world. In: Bogdanov, P. Ed., Casting Call, 9(3). http://www.vermico.com [83] Sinha, R.K. (1998) Embarking on the second green rev- olution for sustainable agriculture in India: A judicious mix of traditional wisdom and modern knowledge in ecological farming. Journal of Agricultural & Environ- mental Ethics, Kluwer Acad. Pub., Dordrecht, 183-197. [84] Sinha, R.K. (2004) Sustainable Agriculture. Surabhee Publication, Jaipur, 370. [85] Grappelli, A., Tomati, V., Galli, E. and Ve rgari, B. (1985) Earthworm Casting in Plant Propagation. Journal of Horticultural Science, 20(5), 874-876. [86] Appelhof, M. (2003) Notable Bits. WormEzine, 2(5), http://www.wormwoman.com