Open Journal of Social Sciences

Vol.2 No.4(2014), Article ID:44982,10 pages DOI:10.4236/jss.2014.24041

Asymmetric Oil Price Shock Response: A Comparative Analysis

Olukorede Abiona

Department of Economics, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

Email: olukoredeabiona@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 5 March 2014; revised 9 April 2014; accepted 16 April 2014

ABSTRACT

This paper extends the literature on the effects of oil-price shocks using United States, Norway and South Africa as case studies between 1980 and 2010. The Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) and Panel VAR methodologies are employed as an extension to the conventional unrestricted Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model. Results show that the developed economies (United States and Norway) stick to the non-linear oil-price shock specifications as argued in the literature. However, these are not feasible within the context of the emerging net-oil importing economy. Furthermore, Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) model decisively restricts the oil-price shock effects while the effects intended to be captured may have been overruled by the identification restrictions imposed. Nevertheless, the Panel VAR methodology is able to accommodate all oilprice shock specifications. The claim that there exists a transmission mechanism through which positive oil price shock accruals can be beneficial to the global community was empirically verified using Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as a proxy. In the other way round, there is suggestive evidence of possible unprecedented and unsatisfactory effects during negative oil-price shock periods.

Keywords:Oil-Price Shock; Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) Model; Panel VAR Methodology; Foreign Direct Investment (FDI); Identification Restrictions

1. Introduction

Oil-shock effect on macroeconomic activities has been an interesting research area in energy economics over the past decades. This is partly as a result of recessions experienced by the developed economies aftermath of the early 1970’s oil shock. It is also attributable to the difficulty with the discovery of a perfect and suitable alternative replacement for crude oil’s industrial use in the present world. However, there is a need to have a broader understanding of the effects of oil price shocks which will accord importance to oil price shock effects in both developing and developed economies under the same platform. In this direction, the implementation of alternative Vector Autoregressive methodologies, simultaneously applied on a mixture of contextual development framework, is plausible.

Apparently, the basis for oil shocks is oil price volatility which has become considerably sustained within OPEC session in the oil market. There is a consensus of three distinct epochs of crude oil price behaviour, of persistence and volatility, in the literature. Evidence shows clearly that the OPEC era displays the most volatile epoch of oil price movements between 1861 and 2011. A large spectrum of literature has continually examined the effects of oil-shocks on economic activities in various dimensions. Many studies have established affirmatively the existence of an inverse relationship between economic activities and oil price shocks.

Although, it is difficult to establish a model for global market of crude oil since there are different stands of various strands in the literature [1] . However, economic fundamentals (demand for and supply of crude oil) remain the most fundamental channel of movements in the world oil price. Therefore, a considerable number of studies have tried to empirically establish a relationship between oil price, oil supply and/or oil demand shocks, with others engaged in establishing how these altogether affect some macroeconomic variables [2] . Also, it must be emphasised that in the relation of oil price shocks with economic fundamentals, supply shock is given more priority relative to demand shock. This is due to its historic prevalence in obstructing crude oil prices in the oil market which has actually led some researchers to examine the effects of oil supply shocks on certain economies. However, in recent times, oil demand shocks are increasingly becoming more relevant in oil price movements in the global oil market [1] 1.

In general, the trend in oil price shock studies over the years has revealed expansion in the scope and coverage of oil price shock activities. [3] argued that historic correlation between oil price increase and economic recession is not a statistical coincidence with empirical support from [4] . However, [5] deviated from this strand of literature by confirming the disruptive effects of real oil price on employment through sectoral shifts, in particular labour reallocation process. As a flavour to oil-price shock studies, a new trend of asymmetric effects established by [6] modified by [7] -[9] have since then been prevalent in numerous studies including those in recent times [10] .

2. Motivation for the Study

Given the differences in growth patterns and macro fundamentals across emerging and developed world, it is important to understand the effect of oil-price shocks in respective countries. Essentially, developed countries may be capable of shielding against negative oil-price shocks relative to the developing countries and this call for an empirical investigation. The United States of America (USA), Norway and South Africa have been chosen as case studies given the global representation these economies have regarding oil trade categories. Basically, Structural VAR and Panel VAR methodologies have been used in addition of unrestricted VAR to establish the effect of imposition of identification restriction and pooled data on oil price shock studies.

Our results show that the developed economies (United States and Norway) stick to the non-linear oil-price shock specifications argued in the literature. However, these are not feasible within the context of the emerging net-oil importing economy, South Africa. Furthermore, Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) model decisively restricts the oil-price shock effects while the effects intended to be captured may have been overruled by the identification restrictions. However, the Panel VAR methodology is able to accommodate all oil-price shock specifications. There is an evidence of a transmission mechanism in support of benefit from positive oil price shock accruals to the global community using Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as a proxy. In the other way round, there is suggestive evidence of possible unprecedented and unsatisfactory effects during negative oil-price shock periods.

3. Related Literature

[3] served as the pioneer oil price macroeconomic relationship investigation in the literature. Consequent studies on the United States in the early 1980s by [4] and [11] confirmed the earlier documented inverse relationship between oil prices and aggregate economic activities in the theoretical literature. Furthermore, a generalization of similar relationship was evident in the documentation of countries other than the United States in the studies conducted by [12] [13] .

3.1. Mechanisms of Transmission of Oil Price Shocks to Macro Economic Variables

The channels earlier argued for the inverse relationship between oil price movements and the aggregate economic fundamentals have been modified as soon as oil price movements encountered radical trends during unprecedented global recessions. Oil-price shocks (volatility) have been documented to particularly have the four major potential channels to impacting macroeconomic variables:

3.1.1. The Classical Supply-Side Effect

The classical supply-side effect hinges on reduced availability of basic production inputs, as a result of rising oil prices.

3.1.2. The Income Transfer Effect

The income transfer effect is representative of the demand-side channel of oil price shocks.

3.1.3. Monetary Policy Response

The break down in conventional oil-price shocks effects led to trying to assess additional channels, revealing how induced monetary policy through the central banks influence oil-price macroeconomic relationship.

3.1.4. The Real Balance Effect

The rigidity of the monetary authority to meet up with increased money demand as a result of increase in oil price will lead to retardation in economic growth.

3.2. Oil Price Shocks and Asymmetric Effects on the Economy

Associated with the oil price shock (volatility) is the asymmetric effect of remarkable and significant recession from oil price increase relative to insignificant boom associated with oil price falls. In particular, the 1980s and 1990s featured increased apparent asymmetric response of the United States’ macro-economic variables to oil price shocks. The uncertainty effect and the reallocation effect are basically at play in the asymmetric response of macroeconomic variables to oil price shocks. They magnify the response of macroeconomic aggregates during oil price increases while response to oil price falls are retarded. Among the early studies for the documentation of asymmetric effects are [6] -[9] [14] . In addition to solely monetary policy, some literature have proposed monetary policy and asymmetry; adjustment costs and asymmetry; and gasoline market structure and asymmetry as possible channels of asymmetry.

3.3. Oil Price Shocks: Co-Examining Developing and Developed World

Most oil price studies in the past have separately considered a group of industrialized economies [15] [16] , studied industrial economy independently [17] [18] or individually examined non-OECD economies [10] [19] . With this approach, results have largely been dichotomized along the net oil-importing or net oil-exporting economic classifications. Analysis concerning individual economies have shown that each of the categories have certain unique characteristics in common in reaction towards oil price shocks. For instance studies conducted by [10] and [19] respectively on Venezuela and Nigeria which are both developing economies have confirmed asymmetric response of growth, although in different dimensions; conventional and unconventional asymmetries respectively. Also, developed economies have been justified to react more maturely to oil price shocks probably due to safeguarding structures and signaling indicators they take seriously before oil-shocks. Apart from the support of asymmetry, several studies on the United States among other developed countries have reflected that sound monetary policy stance of the Central Bank of those economies; have been helpful in supporting the economies against the effect of positive oil price shocks [16] .

3.4. Empirical Literature

Recently, scholars have broadened the analysis of macroeconomic impacts of oil prices. [16] examined why the macroeconomic effects of oil-price shocks in the last decade differ from that of the 1970s. There was a conclusion using the G7 countries that improvement in monetary policy, more flexible labour market, smaller share of oil in production and good luck were responsible for this difference. A comparative study of aggregate demand, aggregate supply and oil-price shocks was carried out by [2] with the conclusion that oil-price fluctuation was mainly responsible for affecting the economic activities. [15] and [20] among others using different countries or group of countries and different methodologies are some of the studies that established asymmetric relationship between oil-price shocks and economic activities (GDP growth in some cases).

Also, another strand of research linking oil-price shocks and economic growth in inflation targeting given technological status was carried out by [21] . The United States was used as a case study and it was deduced from the study that intense technological advancement would make an economy less vulnerable to oil-price fluctuations. [22] investigated Norway between 1979 and 1985. It was established that negative effects from lower foreign demand and higher interest rates crowded out the windfalls from oil shock accruable to Norway as an oil exporter. However, the application of an expansionary fiscal policy with spending cuts within the economy during that period stabilized the macro-economic variables.

Also a spectrum of country-specific investigation of the effect of oil-price shocks, each using a number of carefully selected macroeconomic variables of interest exists in the literature. This include, [19] [23] . Results from the aforementioned support the existence of asymmetric effect of oil-price shocks on certain variables albeit in a direction contrary to economic theoretical a priori expectation. In a similar direction, [17] presents oil price shocks previously undermined, as becoming more pervasive and of greater prominence after structural shifts were accommodated within the models used. [24] empirically investigate how China’s macro-economy relates with global oil-price shocks. It proposes through his study that there is a significant non-linear relationship existing between oil-price shocks and China’s macro-economy with the conclusion that China’s different economic era is not capable of affecting the world oil price simultaneously.

Lastly, the gap to be filled is the scarcity of developing net-oil importing literature in oil price shock studies. Attention has been side-lined from this category based on the assumption that they have no unique role in the determination of world oil price. This paper will emphatically investigate the authenticity of this notion and South Africa has been spotted as an eligible2 case study of net oil-importing developing economies for that purpose. This will be co-examined with the developed world net oil importing (United States) and exporting (Norway) respectively.

4. Empirical Strategy

The methodological framework that will be used in this study is Vector Autoregressive Model. It will adopt both the linear and the non-linear model specifications in capturing the intensity of the impacts of oil-price shocks on quarterly selected macroeconomic variables which are real GDP (RGDP), Inflation rate proxied by consumer price index (INFCPI), Interest Rate (INT), Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The approach used by the studies conducted by [19] [20] and [24] is followed. The linear benchmark specification entails the spot oil-price linearly denoted by OIL specifying both increase and decrease in oil-price. The three representations of oil-price shocks under the non-linear specifications are derived as follows:

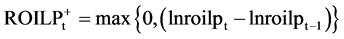

[6] claimed that asymmetries exist in how increase and decrease in oil-prices will impact an economy under consideration and so separated positive oil-price shocks from negative oil-price shocks. Mork’s positive and negative Real Oil Price shocks are respectively denoted by  and

and  and these are obtainable in the following ways.

and these are obtainable in the following ways.

where ln is natural logarithm; roilpt and roilpt-1 are known as the real oil price at times t and t − 1 respectively.

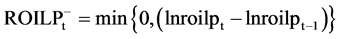

[8] ’s non-linear specification of oil price shocks argues that, in order to know the extent the extent to which oil-price shocks affects consumption and investment decisions, current oil-prices are not expected to be compared with the immediate previous quarter, but with previous four quarters. This implies that Net Oil Price Increase (NOPI) is defined as the percentage increase in the current price of oil over the price of the previous four quarters if it is positive and zero applicable otherwise. This is mathematically written as

where ln is natural logarithm; oilt and oilt−i are known as the real oil price at times t and t − i respectively.

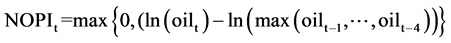

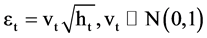

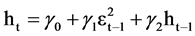

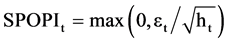

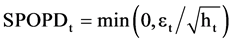

[7] argued that an oil-price change is likely to have a greater impact on real GDP in an environment where oil prices have been previously stable than in an environment where the oil prices have been erratic. GARCH (1,1) model was employed to capture oil shock in different environments with different backgrounds in the following ways:

where SOPIt and SOPDt are used as measures of non-linear effects of oil-price volatility and are defined respectively as positive and negative scaled oil-price measures.

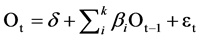

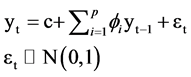

In summary, The general framework of a pth-order VAR model that is adopted for analysis in this study is

(4.1)

(4.1)

The order-p of the VAR model is established following [17] in which maximum lags are determined by lag length criteria from E-views.

4.1. Models for Estimation

4.1.1. Unrestricted VAR Model

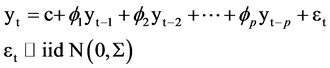

The general VAR model of pth order can be literally written as

(4.2)

(4.2)

where yt is a n × 1 vector of variables at time t and c is an intercept.

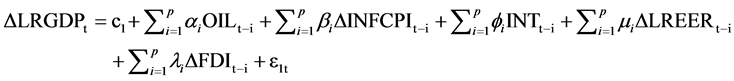

Whereas, considering the multivariate models under consideration we have the following as pth-order oil price shock multivariate model for estimation in each country.

Model 1.

Model 1.

The granger causality3 is examined with more focus on the extent to which oil-price shocks cause the considered macroeconomic variables with different oil-price shock sessions during the period under examination.

4.1.2. Structural VAR Model

Structural VAR model is a restricted version of the VAR model in which identification restriction is imposed on the VAR model to be estimated. Majorly, the kind of identifying restriction on dynamics among which structural VAR falls favours imposition of identification restrictions on the matrix of contemporaneous coefficients, variance-covariance matrix (Σ) or long run coefficients (Lack and Lenz, 2000). In the present study with an assumption of n variables, n2 independent restrictions on parameters of the structural form are required for an exact identification of the system.

Furthermore, the reason for imposing the identification restriction is to limit the interaction/direction of causality among variables of concern. In structural VAR literature, these restrictions are usually taken from economic theory and are intended to represent meaningful short-run or long-run relationship between the variables and the structural shocks. Short-run restrictions are allowed directly on reduced VAR to show forth the contemporaneous reaction of variables to structural innovations. For a six variable case of Structural VAR model, the minimum identification restriction that can be imposed is 21 making the model an exactly identified model. Using the cholesky-decomposition of errors imposes an ordering where structural shocks contemporaneously affects only succeeding variables in a pre-specified order. The format of a six variable structural VAR model exactly identified through the identification scheme is as follows:

μOIL = ЄOIL

μRGDP = c21 μOIL + ЄRGDP

μINFCPI = c31 μOIL + c32 μRGDP + ЄINFCPI

μINT = c41 μOIL + c42 μRGDP + c43 μINFCPI + ЄINT

μREER = c51 μOIL + c52 μRGDP + c53 μINFCPI + c54 μINT + ЄREER

μFDI = c61 μOIL + c62 μRGDP + c63 μINFCPI + c64 μINT + c65μREER + ЄFDI

where μ = Observed residual Є = Structural innovations/shocks or fundamental shocks.

4.1.3. Panel VAR Model

This methodology helps in pooling of the macroeconomic variable series of the different economies together. The dynamic fixed-effect Panel estimation which is recommended for a situation where it is uncertain if errors and variables of interest are uncorrelated is used.

5. Results

5.1. Data Description, Unit Root and Stability Tests

The data sets used in this section are gathered from IMF’s International Financial Statistics database and BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2011). Carefully examining the unit root tests’ results, it can be extracted that all variables are stationary at their first difference except oil price shock measures. In addition, The data shows an insignificance of the structural break points located by the Quandt-Andrews unknown structural break point tests in the United States and Norway for all oil shock measures4 under consideration. However, South African economy displays a specific structural break date of 1993q02 in all the oil price shock series particularly when examined independently of all other variables. The structural break date is exogenously adjusted-for using a dummy imposition5.

In explicit terms, it is important to note that Real Gross Domestic Product and Real Effective Exchange Rate are actually inputted as first log-difference. Inflation, Interest Rate and Foreign Direct Investment are allowed in the models in their first difference forms. The major reason for first log-difference Real Gross Domestic Product is to capture business cycle growth rate. This approach is an idea borrowed from [17] and [20] .

5.2. Presentation and Interpretation of Results

5.2.1. Granger Causality from Unrestricted VAR Models

In Table 1, the United States’ results comply with the literature and a priori theoretical expectation of asymmetry. This is evident in virtually all the three non-linear specifications as causality probabilities in positive oil price shocks are relatively more significant and more pronounced than in negative oil price shocks. Although, asymmetric relationship exists through other non-linear specifications in Table 2 as indicated, the claim of [7] does not seem to be appropriate for Norway. In addition, [10] have specifically ascertained that the oil price shock considered for oil exporting economies is the NOPI. This is supported by the result above with Norway’s business cycle demonstrating an asymmetric response with regard to NOPI. Hence, results in United States and Norway comply with a priori expectation of asymmetry as in the literature.

Furthermore, the above results show with persistent significance that there is an indication that the Real Effective Exchange Rate of net-oil producing economies (Norway) responds significantly to oil-price shock series. This was not evident in the net oil-importing economies (United States and South-Africa) in Table 1 and Table 3 respectively. It shows forth that most oil producing economies are actually affected by the activities of the world oil market. Particularly, this is an indication that the weight ascribed to their economy at a point in time is majorly determined by whether there is positive or negative oil price shock. Also, the claim that accruable funds from crude oil transactions is beneficial not only to the oil producing economies, but to the whole world through foreign investment or transfers has been established. This can be extended to incorporate the fact that negative oil price shock would also have a conspicuous effect in the world financial market through the inability of the net oil exporting economies to support the market’s essential liquidity requirements for investment purposes.

5.2.2. Structural VAR Model Results

The results, shown in Tables 4-6, using the Structural VAR model are not favourable to non-linear specifications, which is one of the emphasis of this paper. The developed countries (United States and Norway) used as

Table 1. Granger causality of oil price shock measures on variables in United States.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

Table 2. Granger causality of oil price shock measures on variables in Norway.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

Table 3. South africa’s oil granger causality.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

case studies do not tend to support the literature concerning the asymmetric response6 of economic growth to oil price shocks using this particular methodology. The inability of the model to support the non-linear specifications would be attributed to the restrictions imposed on the inter-relatedness of residual series of the oil shock and variables. It ensures that only the effects of (diverse) oil price shock measures are relevant on all other variables, while none of the macroeconomic variables are considered to have any reciprocal effect on oil price shocks.

This approach proclaims a sort of strict exogenous nature of the oil price shock measures against which [1] has emphatically argued. This implies that [1] was probably right as oil price shock measures are not meant to be completely determined outside the model but should be considered within the model, which was satisfied to a large extent with the use of unrestrictive oil price shock models. However, a model which would amplify a complete endogeneity of oil price shock measures is much awaited in the oil-price shock literature.

5.2.3. Panel VAR

Table 7 shows that the establishment of asymmetric response is unable to nullify the continuous existence of linear model when the interrelatedness of the economies is considered using Panel VAR. Generally, the results derived from specified models for the whole world scenario is quite insightful. Despite strong evidence in support of non-linear specifications by the OECD economies, linear specification by the non-OECD still holds. Specifically, different economic category is accountable for the establishment of linear and/or non-linear specification for business cycle growths in their respective cases.

Table 4. Structural var results of oil price shock measures on variables in United States.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

Table 5. Structural var results of oil price shock measures on variables in norway.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

Table 6. Structural var results for south africa.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

Table 7. Wald joint significance test of oil price shock measures on pooled series.

*, ** and *** represents 10%, 5% and 1% levels of significance respectively.

5.2.4. Diagnostic Tests

The normality, serial correlation and residual autocorrelation tests are respectively investigated. It is evident that the models have similar behaviour across countries. The behaviour that the models elicit with respect to normal test is quite unique as the models are basically multivariate normal with five variables, while there is an indication that an additional sixth variable is responsible for the deviation of some models from multivariate normality. The Foreign Direct Investment which is purely determined outside each economy is mostly responsible for this deviation. However, with the serial correlation test, the models behave quite satisfactorily. Also, all the residual autocorrelation tests are fit and support the chosen lags for models.

In addition, the wald F-statistic is used to test for the joint significance of lagged oil shock measures on economic growth. The outcomes are consistent with the granger causality results. In summary, most preferred specifications using the diagnostic and wald tests, for United States, Norway and South Africa are respectively ROILPI/ROILPD, NOPI and OIL.

6. Conclusions

This paper aims at investigating the effects of oil price shocks on selected economies. The inclusion of developing economies in cross country oil-price shock studies has previously been overlooked in the literature and this research seeks to contribute some understanding to this gap in knowledge. In addition, the application of Structural and Panel VAR models are major extension to the literature on cross-border oil-price shock studies which have limited its use to unrestricted VAR model among other methodologies. In another dimension, the theoretical argument of an extended global beneficial scenario for positive oil price shock cases, as proposed by [1] , was put to empirical test.

Results show that asymmetric response of major macroeconomic variables continues to hold in selected OECD countries in the present paper. This is consistent with literature [20] . On the other hand, evidence from South Africa is inconsistent with the literature of oil price shocks on emerging countries. Also, the application of Structural VAR has proven largely inefficient in oil shock studies. This is evident by the findings that proceed from Structural VAR models which fall short of the expectation of a priori causalities of oil shocks. However, Panel VAR methodology supports the efficacy of both symmetric and asymmetric nature of oil price shocks. In conclusion, the imposition of identification restrictions is not recommended for studies on oil-price shock effects.

References

- Kilian, L. (2010) Oil Price Volatility: Origins and Effects. World Trade Organisation Staff Working Papers.

- Bjornland, H.C. (2000) The Dynamic Effects of Aggregate Demand, Supply and Oil Price Shocks—A Comparative Study. The Manchester School, 68, 578-607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9957.00220

- Hamilton, J.D. (1983) Oil and the Macroeconomy since World War II. Journal of Political Economy, 91, 228-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/261140

- Gisser, M. and Goodwin, T.H. (1986) Crude Oil and the Macroeconomy: Tests of Some Popular Notions. Journal of Credit Money and Banking, 18, 95-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1992323

- Loungani, P. (1986) Oil Price Shocks and the Dispersion Hypothesis. Revision of Economic Statistics, 68, 536-539. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1926035

- Mork, K.A. (1989) Oil and the Macroeconomy When Prices Go up and down: An Extension of Hamilton’s Results. The Journal of Political Economy, 97, 740-744. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/261625

- Lee, K., Ni, S. and Ratti, R.A. (1995) Oil Shocks and the Economy: The Role of Price Variability. Energy Journal, 16, 39-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol16-No4-2

- Hamilton, J.D. (1996) This Is What Happened to the Oil Price-Macroeconomy Relationship. Journal of Monetary Economics, 38, 215-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(96)01282-2

- Hamilton, J.D. (2003) What Is an Oil Shock? Journal of Econometrics, 113, 363-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(02)00207-5

- Mendora, O. and Vera, D. (2010) The Asymmetric Effect of Oil Shocks on An Oil-Exporting Economy. Cuaderno De Economica, 47, 3-13.

- Hickman, B., Huntington, H. and Sweeney, J. (1987) Macroeconomic Impacts of Energy Shock. North Holland, Amsterdam.

- Darby, M. (1982) The Price of Oil and World Inflation and Recession. American Economic Review, 25, 459-484.

- Burbidge, J. and Harrison, A. (1984) Testing for the Effects of Oil-Price Rises Using Vector Autoregression. International Economic Review, 25, 459-484. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2526209

- Mory, J.F. (1993) Oil Prices and Economic Activity: Is the Relationship Symmetric? The Energy Journal, 14, 151-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol14-No4-10

- Lardic, S. and Mignon, V. (2006) The Impact of Oil Prices on GDP in European Countries: An Empirical Investigation Based on Asymmetry Cointegration. Energy Policy, 34, 3910-3915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2005.09.019

- Banchard, O. and Gali, J. (2008) The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Why Are the 2000s So Different from the 1970s? Forthcoming in: Gali and Gertler (Eds.). University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Gausden, R. (2010) The Relationship between the Price of Oil and Macroeconomic Performance: Empirical Evidence for the UK. Applied Economic Letters, 17, 273-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504850701720130

- Kormilitsina, A. (2011) Oil Price Shocks and the Optimality of Monetary Policy. Review of Economic Dynamics, 14, 119-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2010.11.001

- Iwayemi, A. and Fowowe, B. (2011) Impact of Oil Price Shocks on Selected Macroeconomic variables in Nigeria. Energy Policy, 39, 603-612. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.10.033

- Jimenez-Rodriguez, R. and Sanchez, M. (2005) Oil Price Shocks and Real GDP Growth: Empirical Evidence for Some OECD Countries. Applied Economics, 37, 201-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0003684042000281561

- Doroodian, K. and Boyd, R. (2003) The Linkage between Oil Price Shocks and Economic Growth with Inflation in the Presence of Technological Adavances: A CGE Model. Energy Policy, 31, 989-1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(02)00141-6

- Eika, T. and Magnussen, K.A. (2000) Did Norway Gain from the 1979-1985 Oil Price Shock? Economic Modelling, 17, 107-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0264-9993(99)00023-1

- Aydin, L. and Acar, M. (2011) Economic Impact of Oil Price Shocks on the Turkish Economy in the Coming Decades: A Dynamic CGE Analysis. Energy Policy, 39, 1722-1731. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.12.051

NOTES

1This new development basically establishes how oil flow demand shocks fundamentally differs to oil demand and oil supply shocks from theoretical perspective.

2South Africa is considered eligible due to the proximity of its economic structure to those of the comparable advanced countries in this paper and data availability for the estimation.

3The impulse response function and variance decomposition analysis of the VAR outcome are equally important are co-examined in this section with granger causality but unreported in this paper due to space limitation.

4This is investigated considering the series of each oil price shock measure with other variables of estimation and independent of other variables of estimation.

5This is unlike other studies example of which is in which the structural break date discovery led to the separation of the estimation period into two different estimations.

6United States displayed an unconventional asymmetric economic growth response along ROILPD path while ROILPI was unable to trigger any form of relationship.