Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.11, 991-996 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.311149 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 991 Mortality Salience and Metabolism: Glucose Drinks Reduce Worldview Defense Caused by Mortality Salience Matthew T. Gailliot Psychology Department, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nac o g doches, USA Email: mgailliot@gmail.com Received August 23rd, 2012; revised September 23rd, 2012; accepted October 21st, 2012 The current work tested the hypothesis that a glucose drink would reduce worldview defense following mortality salience. Participants consumed either a glucose drink or placebo, wrote about either death or dental pain, and then completed a measure of worldview defense (viewing positively someone with pro-US views and viewing negatively someone with anti-US views). Mortality salience increased world- view defense among participants who consumed a placebo but not among participants who consumed a glucose drink. Glucose might reduce defensiveness after mortality salience by increasing the effectiveness of the self-controlled suppression of death-related thought, by providing resources to cope with mortality salience and reducing its threatening nature, or by distancing the individual from actual physical death. Keywords: Mortality Salience; Glucose; Metabolism; Worldview Defense Introduction Reminders of mortality are commonplace, yet people often avoid thinking about death because thoughts of dying can be personally threatening (e.g., Aries, 1981; Becker, 1973). The threatening nature of mortality triggers defensive reactions that function to reduce awareness of death (e.g., Florian & Miku- lincer, 1997; Greenberg et al., 1990; Heine, Harihara, & Niiya, 2002; Landau et al., 2004; Ochsmann & Mathey, 1994). The current work focused on the biology of responses to death re- minders. It is posited that avoiding thoughts of death is de- manding, psychological work that requires additional metabolic energy. When metabolic energy is low, death should be more threatening. The prediction therefore was that lower glucose— the primary energy for the brain—would increase defensive responding to mortality reminders. There are at least three reasons why low glucose should be linked with increased defensiveness after mortality salience. One is that low glucose might impair the effortful, controlled suppression of death thoughts and thus increase defensive reac- tions to death reminders. Thoughts of death are avoided and suppressed (e.g., Aries, 1981; Becker, 1973; Feifel & Brans- comb, 1973; Greenberg, Pyszczynski, Solomon, Simon, & Breus, 1994; Harmon-Jones, Simon, Greenberg, Pyszczynski, Solomon, & McGregor, 1997; Pollak, 1979, 1980). The avoid- ance or suppression of death thoughts is effortful and demand- ing (Arndt et al., 1997; Greenberg et al., 2001), and requires controlled or executive processes (Greenberg et al., 1994; Harmon-Jones et al., 1997; Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solo- mon, 1999; Wegner, 1994). For instance, after thinking about mortality, death thoughts are suppressed and less accessible to awareness (e.g., Arndt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, & Simon, 1997; Greenberg et al., 1994; Harmon-Jones et al., 1997). Factors that impair controlled or executive processing (e.g., a cognitive load) undermine such suppression, however, and increase the accessibility of death thoughts (Arndt et al., 1997; Greenberg, Arndt, Schimel, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 2001; Smart & Wegner, 1999; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994; Wen- zlaff & Wegner, 2000). In particular, thought suppression requires self-control (e.g., Baumeister, Tice, & Heatherton, 1994; Wegner, 1994). Thus, people with good (v. poor) trait self-control appear less suscep- tible to thinking about death (Gailliot, Schmeichel, & Bau- meister, 2006). Ample evidence indicates that exerting self- control impairs subsequent self-control (for reviews, see Bau- meister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000; Gailliot, 2009). Consistent with these findings, suppressing thoughts impairs subsequent self-control (e.g., Gordijn, Hin- driks, Koomen, Dijksterhuis, & Van Knippenberg, 2004; Mu- raven et al., 1998), as does mortality salience. Mortality Sali- ence has been found to impair performance on tasks requiring self-control, such as the Stroop task, solving anagrams, and effortful persistence tasks (Gailliot et al., 2006; Gailliot et al., 2007). The idea is that, after thinking about death, people use self-control to suppress thought related to death, and this im- pairs subsequent self-control. One study found that regulating emotions increased death thoughts among participants with poor trait self-control but not among participants with good trait self-control (Gailliot, Schmeichel, & Maner, 2007). Regulating emotions weakened self-control, thereby increasing the acces- sibility of death-related thought, except among people with dispositionally good self-control. These findings indicate that self-control allows for the suppression of death related thought. Self-control, controlled processing, and effortful exertion use a relatively large amount of glucose, are better with optimal glucose levels in the bloodstream, and are impaired by low glucose or other metabolic problems (DeWall, Baumeister, Gailliot, & Maner, 2008; Fairclough & Houston, 2004; Gailliot, 2008; Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007; Gailliot et al., 2007; Gail- liot, Peruche, Plant, & Baumeister, 2009; Masicampo & Bau- meister, 2008). This indicates that the suppression of death- related thought after mortality salience is improved by glucose and impaired by low glucose or metabolic problems. Consistent with this rationale, mortality salience impaired self-control (i.e.,  M. T. GAILLIOT it reduced persistence at solving word fragments) in one study among participants who had consumed a placebo but not a glu- cose drink (Gailliot et al., 2007). The glucose drink presumably provided metabolic energy for self-control that had been de- pleted by suppressing thoughts of death. A few studies suggest that mortality salience might increase attempts to increase one’s metabolic energy, such as increasing the desire to buy food and to increase eating (Friese & Hofmann, 2008; Mandel & Smeest- ers, 2008; cf. Goldenberg, Arndt, Hart, & Brown, 2005). Per- haps mortality salience increases rating because people seek energy that can be used t o avoid thinking abou t death. Effortful thought suppression reduces the implicit and ex- plicit accessibility of suppressed thoughts (Anderson & Green, 2001; Arndt et al., 1997; MacLeod, 1989; McBride & Dosher, 1997; Pyszczynski et al., 1999). Individuals with optimal glu- cose levels therefore should be more successful in suppressing death thoughts. When mortality is salient, people respond de- fensively by increasing support for their worldviews, such as by reacting more positively toward people who support their cul- tural norms and values and more negatively toward those who disagree with their cultural norms and values (e.g., Florian & Mikulincer, 1997; Greenberg et al., 1990; Heine, Harihara, & Niiya, 2002; Landau et al., 2004; Ochsmann & Mathey, 1994). Because glucose might enable more effective suppression of death thoughts and reduce their accessibility, then it should reduce defensive reactions to mortality salience. Consistent with this hypothesis, consuming food (v. eating nothing) re- duced worldview defense caused by mortality salience, in the form of less negative judgments of worldview transgressions (Hirschberger & Ein-Dor, 2005). The food provided glucose that may have enabled more effective suppression of death- related thought and consequently less worldview defense. A second reason that glucose should influence worldview defense following mortality salience is derived from research on personal threat. Perceptions of threat tend to occur when the demands of the threat exceed resources available to cope (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Blascovich & Mendes, 2000). Glucose is one resource used to cope with (i.e., suppress or avoid) thoughts of death. When it is low, death reminders should be more threatening. Defensive reactions therefore should be stronger. It is possible that mortality salience might increase eating (Friese & Hofmann, 2008; Mandel & Smeesters, 2008) partly because individuals seek metabolic resources (e.g., glucose) to cope with the threat of death. The third reason that glucose should reduce defensive reac- tions to death reminders is that glucose is one substrate that determines both the physical and psychological threat of death. When glucose is low, physical death is more likely (e.g., from starvation, a weakened immune system, or a reduced capacity for energy demanding thought and behavior that aids in sur- vival) and death is more threatening psychologically, as the individual should be less able to cope. Death reminders there- fore should be more threatening both physically and psycho- logically when glucose is low, thereby leading to stronger de- fensive reactions. Thus, defensive reactions to mortality salience should be re- duced with additional glucose. Glucose might enable more effective suppression of death-thoughts and/or reduce the extent to which death is perceived as physically or psychologically threatening. To test this hypothesis, participants wrote about either death or a control topic, consumed a glucose drink or placebo, and then completed a measure of worldview defense. The prediction was that mortality salience would increase worldview defense but that this effect would be attenuated among participants who consumed a glucose drink. Method Participants The final sample included 93 college undergraduates (73 women, 20 men) who participated in exchange for extra credit toward a course grade. Excluded from this sample were 8 par- ticipants who failed to complete the required experimental ma- terials and 13 participants who failed to drink the assigned bev- erage. The dependent measure of worldview defense pertained to American values and attitudes toward foreigners, and so 19 participants of non-US (foreign) ethnic cities were excluded from the final sampl e . Materials and Procedure Participants first consumed 14 ounces of lemonade sweet- ened with either sugar (glucose condition) or a sugar substitute (placebo condition). The glucose drink contained approxi- mately 140 calories, whereas the placebo contained 0 calories. Participants and the experimenter were blind to condition. Next, participants wrote about either death or a control topic (dental pain). Participants in the mortality salience condition were asked to describe the emotions, the thought of their own death aroused in them and to write about what would happen to their bodies as they physically die (Rosenblatt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, & Lyon, 1989). Participants in the den- tal pain condition answered the same questions except they were about dental pain rather than death. The effects of the mortality salience manipulation used typi- cally emerge only after a short delay or distraction (Pyszczyn- ski et al., 1999). To provide this delay and distraction, and to allow sufficient time for the glucose (if any) in the drinks to be metabolized, participants completed measures of liking and taste for the drinks and a measure of mood and arousal. Spe- cifically, they indicated the extent to which the drink tasted good, sweet, bitter, and salty, had good texture and appearance, was difficult to drink, was pleasant to drink, and how much they liked the drink. They then completed the Brief Mood In- trospection Scale (BMIS; Mayer & Gaschke, 1988). The BMIS contains 20 items indicative of mood (e.g., happy, sad) and arousal (e.g., peppy, drowsy). Participants rated each item to indicate how they were feeling at the present moment, using a scale from 1 (definitely do not feel) to 7 (definitely feel). Last, partic ipants comple ted a measure of worldvi ew defense. Specifically, participants read two handwritten essays about the United States that were ostensibly written by two foreigners (borrowed from Greenberg, Simon, Pyszczynski, Solomon, & Chatel, 1992). The order of the two essays was counterbalanced across participants. One essay was pro-US and praised Ameri- cans, whereas the other essay was anti-US and criticized Americans. Participants evaluated the truth and validity of the essay and the likeability, intelligence, and knowledge ability of each essay’s author on 9-point scales. The summed evaluations of each essay served as the measures of favorability toward worldview-consistent and worldview-inconsistent opinions, re- spectively. In accord with past research (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1994), worldview defense was defined as the difference be- tween these two measures. Larger differences indicate more Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 992  M. T. GAILLIOT pronounced worldview defense. Results A 2 (Drink condition: Glucose drink vs. placebo) × 2 (Essay condition: Mortality salience vs. dental pain) analysis of vari- ance (ANOVA) on worldview defense scores indicated a sig- nificant interaction, F(1,89) = 4.04, p < .05. See Figure 1 for means. Tests of simple effects indicated that mortality salience, compared to dental pain salience, increased worldview defense in the placebo condition, F(1,42) = 4.2 3, p < .05, but not in the glucose-drink condition, F < 1, ns. Thus, mortality salience did not increase worldview defense among participants who con- sumed a glucose drink. Analyses indicated that these results were not attributable to differences in taste, appearance, or likeability between the two drinks or to mood or arousal. Specifically, separate 2 (Drink condition: Glucose drink vs. placebo) × 2 (Essay condition: Mortality salience vs. dental pain) ANOVAs on taste, sweet- ness, bitterness, saltiness, texture, appearance, pleasantness, and likeability of the drink, as well as on how difficult the drink was to consume and on mood indicated no significant interac- tions, Fs < 2.03, ps > .15. A 2 × 2 ANOVA on arousal indi- cated a marginally significant interaction, F = 3.26, p = .07, suggesting the highest arousal among participants in the pla- cebo condition who wrote about death. The 2-way interaction between drink and essay conditions on worldview defense re- mained marginally significant when controlling for arousal, F = 3.20, p = .08, however, indicating that the effects were not driven by arousal. Discussion Consistent with past work, the current study found that mor- tality salience increased worldview defense. This effect oc- curred only among participants who consumed a placebo, however, and not among participants who consumed a glucose drink. The rationale was that glucose would reduce worldview defense because it allows for more effective suppression of death-related thought via self-control, is a resource used to cope with death (thus the threatening nature of mortality salience 1 2 3 Worldview Defense Dental Pain Mortality Salience Glucose Placebo Glucose Drink Condition Figure 1. Worldview defense as a fu n ct i o n of essay and drink conditions. should be reduced), and/or is a signal that death is more threat- ening physically and thus psychologically. Glucose reduces defensive reactions to mortality salience, whereas low glucose predisposes individuals to increased defensiveness after mortal- ity salience. Past work has shown that mortality salience has a cognitive cost. It activated controlled suppression mechanisms that impair self-control afterwards (Gailliot et al., 2006; Gailliot et al., 2007). The current work suggests that mortality salience might also have metabolic costs. Suppressing thoughts of death could plausibly reduce glucose faster than it is replenished. Another implication is that glucose can be used as an aid to help people cope with death or suppress or avoid death-related thought. Rather than respond defensively, which can often en- tail derogating others, a glucose drink might quell at least some of the potential terror elicited by thoughts of death. Metabolic problems aside from low glucose (e.g., hunger, malnourishment) might also moderate defensive reactions to death. Diabetes and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, two metabolic disorders, have been linked with reduced aggres- sive restraint (DeWall, Gailliot, Deckman, & Bushman, 2009), one form of self-control, suggesting that these disorders might relate to reactions to mortality salience as well. The amount of metabolic energy that can be used during a given amount of time is limited (Klieber, 1961). A large body of evidence demonstrates that energy used by one process therefore can be diverted away from others (Gailliot, Hilde- brandt, Eckel, & Baumeister, 2009). Hence, processes that in- fluence glucose (e.g., immune defense, biological reproductive activity, stress) could also influence defensive responding to mortality salience. Cancer cells, for instance, use a dispropor- tionately large amount of glucose (Schoen et al., 1999; Weber et al., 2003; Younes, Lechago, Somoano, Mosharaf, & Lechago, 1996). Some evidence suggests that their metabolic-energy use might divert energy away from and thereby impair frontal lobe functioning (Cleeland et al., 2003; Meyers, Albitar, & Estey, 2005; Meyers, Byrne, & Komaki, 1995). Individuals with can- cer therefore might especially struggle to avoid thinking about death or engaging indefensive responses not only because of their potentially terminal condition but also because the cancer cells might divert metabolic energy away from the suppression of death-related thought or contribute to low glucose levels that predispose toward heightened defensivene ss. Metabolic a ctivity increases in the ovaries during premenstrual syndrome, and these increases appear to divert energy from and impair self- control (Gailliot et al., 2009). Women therefore might be espe- cially likely to engage in defensive responding to mortality salience while experiencing premenstrual syndrome symptoms. Evidence indicates that the psychological capacity for some processes operates through the existence of earlier, biological systems (e.g., morality and disgust, Wheatley & Haidt, 2005; emotional and physical pain, DeWall & Baumeister, 2006; Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004; Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Processes enact- ing self-control rely heavily on glucose levels (e.g., Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007; Gailliot et al., 2007). If metabolite levels are indicative of survival capacity, with low glucose indicating a greater threat of death (e.g., increased weakness and hunger), then it is possible that the capacity for self-control operates on a preexisting metabolic system that alerts one to the threat of death. Thus, it is the same system that alerts one to the possibil- ity of physical death and that manages psychological thoughts Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 993  M. T. GAILLIOT of death. Work from evolutionary psychology suggests that people think and behave in ways functional to goal attainment, such as perceiving increased threat from others when afraid or in- creased sexual interest when sexually aroused (Maner, Gailliot, & DeWall, 2007; Maner et al., 2005). The current findings suggest a functional response concerning low glucose and mor- tality. When glucose is low, the individual is in a weaker, more vulnerable state, and thoughts of death might come to mind more readily. The thoughts of death function to increase the individual’s connection to culture, which facilitates survival. It is functional that, in a weakened state, thoughts of death might increase so as to mesh the individual in a stronger system that facilitates survival. Evolution is viewed mostly in terms of natural selection based on survival and reproduction. One underemphasized view is that natural selection operates in terms of energy (Gilliland, 1978; Lotka, 1922; Odum, 1995). Organisms that acquire, use, and control larger amounts of energy tend to survive and re- produce, as will those that are more efficient. Organisms that do not maximize energy are selected against. Over time, species increase their capacity to process or control larger amounts of energy. People have evolved so as to be capable of sustaining and being part of a larger cultural system (Baumeister, 2005). Culture clearly is a high energy system, providing people with energy (e.g., oil, food) or energy-saving devices (e.g., machines for transportation, vaccines that aid in immune defense). It is fitting that people strengthen their ties to culture after mortality salience when their biological energy (glucose) is low. When personal energy is low, people seek a system that provides en- ergy, consistent with the idea that thoughts and behaviors have been naturally selected to promote the control of higher amounts of energy. Future work on the topic of glucose and mortality salience should examine what mediates the current effects. Theoretical and empirical arguments suggest that glucose reduces world- view defense after mortality salience because people are more effective at the self-controlled suppression of death-related thought, less threatened by death, or more distant from actual physical death. Any of these could potentially mediate the cur- rent effects. Humans are metabolic organisms. Life is a process of ac- quiring and using metabolic energy. To stop the metabolic flow is to end life, to reduce the metabolic flow is to tend closer to death. Likewise, when glucose is low, death might be more threatening in that people respond more defensively to mortal- ity reminders. This new perspective on the management of mor- tality concerns and metabolism raises numerous exciting ave- nues for future research. REFERENCES Anderson, M. C., & Green, C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control. Nature, 6826, 366-369. doi:10.1038/35066572 Aries, P. (1981). The hour of our death. New York: Oxford University Press. Arndt, J., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Simon, L. (1997). Suppression, accessibility of death-related thoughts, and cul- tural worldview defense: Exploring the psychodynamics of terror management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 5- 18. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.5 Baumeister, R. F. (2005). The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning, and social life. New York: Oxford. Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). Strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 351-355. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. New York: Academic Press. Blascovich, J., & Mendes, W. B. (2000). Challenge and threat apprais- als: The role of affective cues. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Feeling and thinking: The role of affect insocial cognition (pp. 59-82). New York: Cambridge. Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1996). The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 1-51. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60235-X Cleeland, C. S., Bennett, G. J., Dantzer, R., Dougherty, P. M., Dunn, A. J. et al. (2003). Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biologic mechanism? A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer, 97, 2919-2925. doi:10.1002/cncr.11382 DeWall, C. N., & Baumeister, R. F. (2006). Alone but feeling no pain: Effects of social exclusion on physical pain tolerance and pain threshold, affective forecasting, and interpersonal empathy. Journal of Personality and Social Ps y c h o l o g y , 91, 1-15. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.1 DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M. T., & Maner, J. K. (2008). Depletion makes the heart grow less helpful: Helping as a function of self-regulatory energy and genetic relatedness. Personal- ity and Social Psychology Bullet in , 34, 1653-1662. doi:10.1177/0146167208323981 DeWall, C. N., Deckman, T., Gailliot, M. T., & Bushman, B. J. (2009). Sweetenedblood cools hot tempers: Physiological self-control and aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 73-80. doi:10.1002/ab.20366 Eisenberger, N. I., & Lieberman, M. D. (2004). Why rejection hurts: The neurocognitive overlap between physical and social pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 294-300. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.010 Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290- 292. doi:10.1126/science.1089134 Fairclough, S. H., & Houston, K. (2004). A metabolic measure of men- tal effort. Biologica l Psychology, 66, 177-190. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001 Feifel, H, & Branscomb, A. B. (1973). Who’s afraid of death? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 81, 282-288. doi:10.1037/h0034519 Florian, V., & Mikulincer, M. (1997). Fear of death and the judgment of social transgressions: A multidimensional test of terror manage- men t the ory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 369- 380. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.369 Friese, M., & Hofmann, W. (2008). What would you have as a last supper? Thoughts about death influence evaluation and consumption of food products. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1388-1394. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.06.003 Gailliot, M. T., Peruche, B. M., Plant., E. A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Stereotypes and prejudice in the blood: Sucrose drinks re- duce prejudice and stereotyping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 288-290. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.09.003 Gailliot, M. T. (2008). Unlocking the energy dynamics of executive functioning: Linking executive functioning to brain glycogen. Per- spectives on Psychological Science, 3, 245-263. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00077.x Gailliot, M. T. (2009). The effortful and energy-demanding nature of prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Proso- cial motives, feelings, and behavior—The better angels of our nature. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Gailliot, M. T., & Baumeister, R. F. (2007). The physiology of will- power: Linking blood glucose to self-control. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 303-327. doi:10.1177/1088868307303030 Gailliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., D eWall, C . N., Maner, J. K. , Plant, E. A., Tice, D. M., Brewer, L. E., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2007). Self- control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 325-336. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 994  M. T. GAILLIOT Gailliot, M. T., Hildebrandt, B., Eckel, L. A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2010). A theory oflimited metabolic energy and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms—Increased metabolic demands during the luteal phase divert metabolic resourcesfrom and impair self- control. Review of General Psychology, 14, 269-282. doi:10.1037/a0018525 Gailliot, M. T., Schmeichel, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2006). Self-regulatory processes defend against the threat of death: Effects of self-control depletion and trait self-control on thoughts and fears of dying. Journal of P e r sonality and Social Psychology, 91, 49-62. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.49 Gailliot, M. T., Schmeichel, B. J., & Maner, J. K. (2007). Differentiat- ing the effects of self-control and self-esteem on reactions to mortal- ity salience. Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, 43, 894-901. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.011 Gilliland, M. W. (1978). Energy analysis: A new public policy tool. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Goldenberg, J. L., Arndt, J., Hart, J., & Brown, M. (2005). Dying to be thin: The effects of mortality salience and body mass index on re- stricted eating among women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1400-1412. doi:10.1177/0146167205277207 Gordijn, E. H., Hindriks, I., Koomen, W., Dijksterhuis, A., & Van Knippenber, A. (2004). Consequences of stereotype suppression and internal suppression motivation: A self-regulation approach. Person- ality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 212-224. doi:10.1177/0146167203259935 Greenberg, J., Arndt, J., Schimel, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (2001). Clarifying the function of mortality salience-induced world- view defense: Renewed suppression or reduced accessibility of death-related thoughts? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 70-76. Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Rosenblatt, A., Veeder, M., Kirkland, S., & Lyon, D. (1990). Evidence for terror management theory II: The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who threaten or bolster the cultural worldview. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 308-318. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.2.308 Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Simon, L., & Breus, M. (1994). Role of consciousness and accessibility of death-related thoughts in mortality salience effects. Journal of Personality and So- cial Psychology, 67, 627-637. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.627 Greenberg, J., Simon, L., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Chatel, D. (1992). Terror management and tolerance: Does mortality salience always intensify negative reactions to others who threaten one’s worldview? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 212- 220. Harmon-Jones, E., Simon, L., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & McGregor, H. (1997). Terror management theory and self-es- teem: Evidence that increased self-esteem reduces mortality salience effects. Journal of Personality and S ocial Psychology, 72, 24-36. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.24 Heine, S. J., Harihara, M., & Niiya, Y. (2002). Terror management in Japan. Asian Journal of S oci al Psychology, 5, 187-196. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00103 Hirschberger, G., & Ein-Dor, T. (2005). Does a candy a day keep the death thoughts away? The terror management function of eating. Ba- sic and Applied Social Psychology, 27, 179-186. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2702_9 Kleiber, M. (1961). The fire of life: An introduction to animal energet- ics. New York: Krieger. Landau, M. J., Sol omon, S., Greenberg, J., Coh en, F., Pyszczynski, T., Arndt, J. et al. (2004). Deliver us from evil: The effects of mortality salience and reminders of 9/11 on support for President George W. Bush. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1136-1150. doi:10.1177/0146167204267988 Lotka, A. J. (1922). Contribution to the energetics of evolution. Pro- ceedings of the National Academy of Science, 8, 147-151. doi:10.1073/pnas.8.6.147 MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2005). Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 202-223. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202 MacLeod, C. M. (1989). Directed forgetting affects both direct and indirect tests of memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cogniti on, 15, 13-21. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.15.1.13 Mandel, N., & Smeesters, D. (2008). The sweet escape: Effects of mortality salience on consumption quantities for high- and low-self- esteem consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 309-323. doi:10.1086/587626 Maner, J. K., Kenrick, D. T., Neuberg, S. L., Becker, D. V., Robertson, B., Hofer, B., Delton, A., Butner, J., & Schaller, M. (2005). Func- tional projection: How fundamental social motives can bias interper- sonal perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 63-78. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.63 Maner, J. K., Gailliot, M. T., & DeWall, C. N. (2007). Adaptive atten- tional attunement: Evidence for mating-related perceptual bias. Evo- lution and Human Behavior, 28, 28-36. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.05.006 Masicampo, E. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2008). Toward a physiology of dual-process reasoning and judgment: Lemonade, willpower, and expensive rule-based analysis. Psychological Science, 19, 255-260. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02077.x Mayer, J. D., & Gaschke, Y. N. (1988). The experience and meta- experience of mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 102-111. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.102 McBride, D. M., & Dosher, B. A. (1997). A comparison of forgetting i n an implicit and explicit memory task. Journal of Experimental Psy- chology: General, 126, 371-392. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.126.4.371 Meyers, C. A., Albitar, M., & Estey, E. (2005). Cognitive impairment, fatigue, and cytokine levels in patients with acute myelogenous leu- kemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer, 104, 788-793. doi:10.1002/cncr.21234 Meyers, C. A., Byrne, K. S., & Komaski, R. (1995). Cognitive deficits in patients with small cell lung cancer before and after chemotherapy. Lung Cancer, 12, 231-235. doi:10.1016/0169-5002(95)00446-8 Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and deple- tion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psy- chological Bulletin, 1 2 6 , 247-259. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247 Muraven, M., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Person- ality and Social Psychology, 74, 774-789. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.774 Ochsmann, R., & Mathey, M. (1994). Depreciating of and distancing from foreigners: Effects of mortality salience. Unpublished Manu- script, Mainz: Universitat Mainz. Odum, H. T. (1995). Self-organization and maximum empower. In C. A. S. Hall (Ed.), Maximum power: The ideas and applications of H. T. Odum. Colorado: Colorado University Press. Pollak, J. M. (1980). Correlates of death anxiety: A review of empirical studies. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 10, 97-121. doi:10.2190/4KG5-HBH0-NNME-DM58 Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1999). A dual process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: An extension of terror management theory. Psychological Review, 106, 835-845. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.835 Rosenblatt, A., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Lyon, D. (1989). Evidence for terror management theory I: The effects of mor- tality salience on reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 681-690. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.681 Schoen, R. E., Tangen, C. M., Kuller, L. H., Burke, G. L., Cushman, M., Tracy, R. P. et al. (1999). Increased blood glucose and insulin, body size, and incident colorectal cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 91, 1147-1154. doi:10.1093/jnci/91.13.1147 Smart, L., & Wegner, D. M. (1999). Covering up what can’t be seen: Concealable stigma and mental control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 474-486. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.3.474 Weber, W. A., Petersen , V., Burkh ard, S., Tyndale-Hines, L., Link, T., Peschel, C., & Schwaiger, M. (2003). Positron emission tomography in non-small-cell lung cancer: Prediction of response to chemother- apy by quantitative assessment of glucose use. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21, 2651-2657. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.12.004 Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychologi- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 995  M. T. GAILLIOT Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 996 cal Review, 101, 34-52. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.34 Wegner, D. M., & Zanakos, S. (1994). Chronic thought suppression. Journal of Personality, 62, 615-640. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00311.x Wenzlaff, R. M., & Wegner, D. M. (2000). Thought suppression. An- nual Review of Psychology, 51, 59-91. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.59 Wheatley, T., & Haidt, J. (2005). Hypnotically induced disgust makes moral judgments more severe . Psychological Science, 16, 780-784. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01614.x Younes, M., Lechago, L. V., Somoano, J. R., Mosharaf, M., & Lechago, J. (1996). Wide expression of the human erythrocyte glucose trans- porter Glut1 in human cancer s. Cancer Research, 56, 1164-1167.

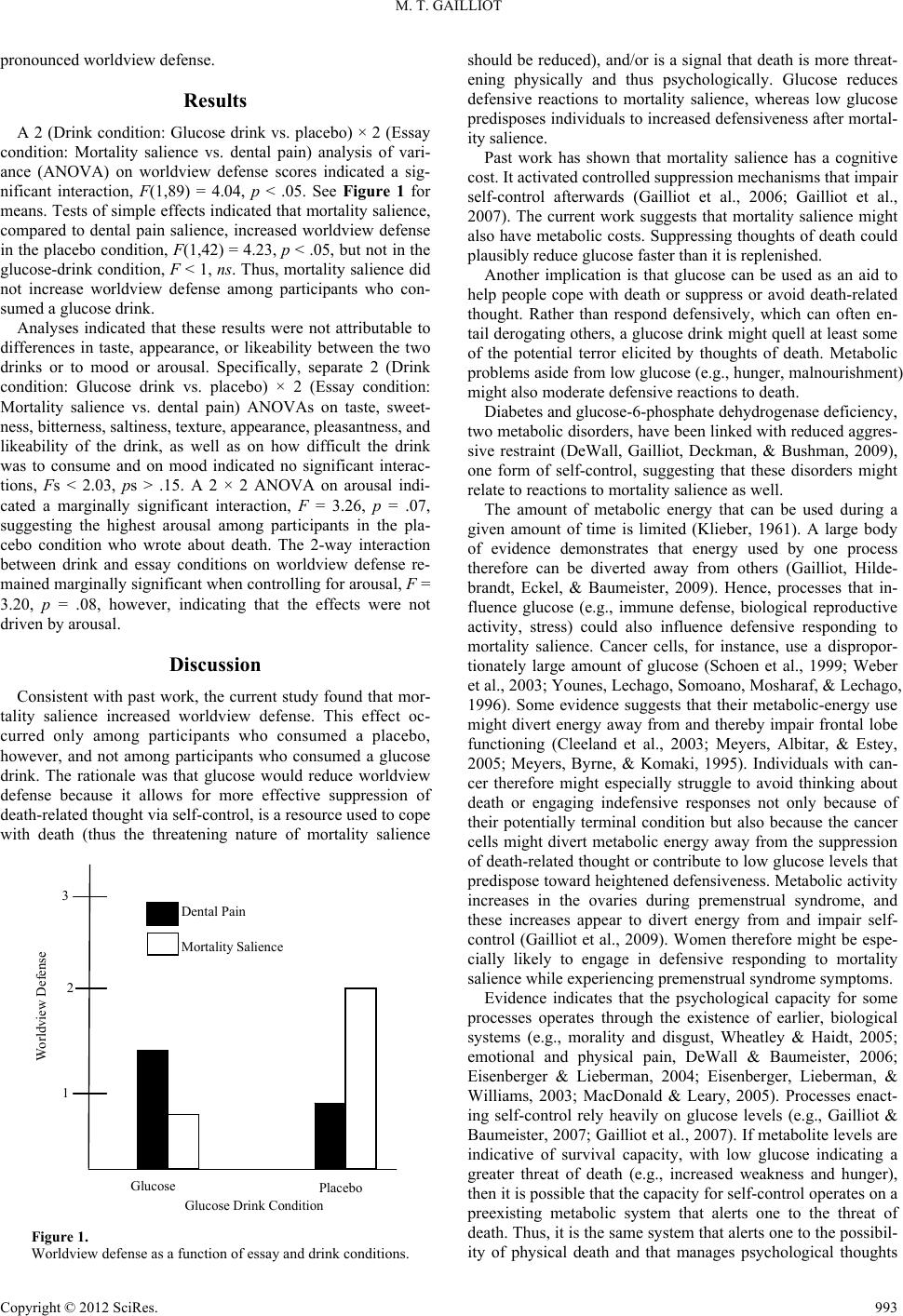

|