Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.7, 1269-1280 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.37186 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1269 Exploring Tutor and Student Experiences in Online Synchronous Learning Environments in the Performing Arts Susi Peacock1, Sue Murray1, John Dean2, Douglas Brown3, Simon Girdler2, Bianca Mastrominico2 1Centre for Academic Practice, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK 2Division of Media, Communication and Performing Arts, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK 3Salzburg University, Salzburg, Austria Email: speacock@qmu.ac.uk, smurray@qmu.ac.uk, jdean@qmu.ac.uk, douglas.brown@sbg.ac.at, sgirlder@qmu.ac.uk, bmastrominico@qmu.ac.uk. Received September 5th, 2012; revised October 2nd, 2012; accepted October 19th, 2012 High levels of student dissatisfaction and attrition persist in blended and online distance learning pro- grammes. As students and tutors become more geographically dispersed with fewer opportunities for face-to-face contact emergent technologies like Online Synchronous Learning Environments (OSLEs) may provide an interactive, connected learning environment. OSLEs, such as Blackboard Collaborate and Adobe Connect, are web-based, computer-mediated communication programs typically using video and audio. This article reports the findings of an exploratory, nine-month study in the performing arts in which tutors used an OSLE for dissertation supervision, pastoral support and performance feedback. Gar- rison & Anderson’s (2003) Community of Inquiry (COI) framework was used as the basis for evaluation of student and tutor experiences to explore in what ways learning could be supported when using the OSLE. Our findings indicate significant benefits of OSLEs including convenience, immediacy of com- munication and empowerment of learners, even for our rehearsal-based case study. For students, it was important to see and talk with each other (peers and tutors), share and discuss developing ideas and check understanding through the video and audio media. Tutors reported that OSLEs required them to re-think the design of the learning environment, re-visit how they facilitated discourse and re-examine their com- munication skills especially with regard to feedback on student performance. Technical limitations such as poor quality audio and video, lack of system robustness, and the need for turn-taking did impact on learning; however, it was accepted that OSLE-technology was improving, and rapidly so. Despite the limitations of the study, the evaluation using the COI framework demonstrated that learning had been supported and that use of an OSLE could support all three elements of the framework: social, cognitive and tutor presence. Also, it was apparent that the tutors and most of the students were extremely commit- ted to using the OSLE believing it offered a lively, personal and dynamic learning space. Keywords: Online Synchronous Learning Environment; Community of Inquiry; Virtual Classroom; Performing Arts Introduction Drivers for encouraging use of an online web-based environ- ment for synchronous communication such as Blackboard Col- laborate, Adobe Connect and Skype within higher education are social, political, economic, and environmental (Laubach & Little, 2009; Cornelius & Gash, 2012). The higher education student population in many countries, including the United Kingdom, consists of a diverse demographic at any time in- cluding school leavers, distance learners, part-time learners and mature learners, as well as international students. All learners have competing demands on their time, such as work, family and/or caring commitments, which they need to manage along- side their studies. In addition, many learners are required to undertake a work-practice placement as part of their higher education experience frequently involving being physically located at a distance from their institution. Tutors within higher education are also facing lifestyle changes, with many now job-sharing or balancing professional and academic responsi- bilities, as well as supporting students based outwith their in- stitution (full or part-time). These factors increase the challenge of maintaining learning support and communities of learners when either the students and/or the tutors are away from the institution. Appropriate and flexible methods of providing ac- cess to learning environments for this ever-changing, highly mobile student profile are thus essential. Traditional methods such as face-to-face lectures and seminars are, in many cases, no longer appropriate (Laubach & Little, 2009). More sophisticated, flexible, robust and accessible learning technologies such as managed learning systems, ePortfolios, wikis, blogs, e-assessment and e-submission systems are now widely embedded within the curriculum in the tertiary sector (Browne, Hewitt, Jenkins, Voce, Walker, & Yip, 2010). Predo- minately used for supporting information delivery and asyn- chronous communication in blended and distance learning en- vironments, the advantages of these learning technologies have included: convenience and flexibility; enabling students to fit learning around work and external commitments; and affording learners more time to reflect when participating in online dis- cussions about complex issues (JISCinfoNet, 2012). Sometimes student engagement and interaction may increase with online  S. PEACOCK ET AL. learning (Rogoza, 2007; Falloon, 2011). However, notable chal- lenges persist. As demonstrated by the numerous case studies conducted in this field, use of online and blended learning en- vironments can lead to: higher levels of student attrition; lower levels of engagement; limited motivation; student frustration and feelings of isolation (Porto, 2006; Butler & Sullivan, 2007). This has resulted in many students avoiding heavily blended or completely online distance learning programmes and taking them only when there is no practical alternative (Porto, 2006; Rogoza, 2007; Butler & Sullivan, 2007; McBrien & Jones, 2009). Use of video conferencing has had some success in ad- dressing such issues but sophisticated, expensive equipment is required as well as training and on-going support (Laubach & Little, 2009; Abbass et al., 2011). Synchronous learning may offer a viable alternative especially with its focus on interaction and emphasis on promoting student engagement in the learning process (Skylar, 2009; Falloon, 2011). It may be particularly useful for those subject areas where communication through speech and body language are required as in rehearsal-based areas like performance arts. This paper explores whether, and in what ways, OSLEs sup- port learning in the performing arts in blended learning pro- grammes. It also seeks to provide a snapshot of student and staff experiences of OSLEs. The evaluative tool used to frame the findings and discussions is the Community of Inquiry fra- mework. The paper will be of interest to a wide ranging audi- ence within the field of higher education in general such as, tu- tors, placement supervisors, subject mentors, educational tech- nologists, staff developers, learning technologists, support staff, researchers, and also students. It is particularly relevant as OSLE-adoption moves from initial enthusiasts to institution- wide implementation (Falloon, 2011). Background Studies are emerging which report on the use of synchronous learning in higher education for both online distance and blen- ded learning (Falloon, 2011). Much of this work has focused on using chat-type tools within or outwith an institution’s virtual learning environment. However, as technologies have advanced, more case studies and exemplars of using synchronous com- munication are appearing. Such technologies can provide an online learning environment with audio and video functionality, as well as communication tools such as hand raising and voting, and opportunities for group break-outs, creating an online class- room where communities of learners could thrive. This study focussed on embedding an online synchronous learning envi- ronment (OSLE) within blended learning programmes in the subject area of performing arts. What Is an Online Synchronous Learning Environment (OSLE)? Typically an OSLE consists of hardware and software com- ponents which support auditory, visual and textual channels of communication through Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), as well as providing functionality to use digital materials for the purpose of sharing and discussing in a range of learning and teaching settings. For example, it is anticipated that an OSLE facilitates use of word processed documents, spread sheets, presentations, images, web-based materials and video recor- dings (see Figure 1). In most cases, due to technological limi- tations, voice communication is not usually spontaneous but speakers must wait their “turn” to participate in the dialogue: the real-time communication is limited to one voice talking at a time. Carbonaro, King, Taylor, Satzinger, Snart and Drummond (2008) compared this with the Aboriginal sharing circle where a talking stick is used. An OSLE is accessed through Internet browsers such as Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome or Safari. The most commonly used commercial products for education are Blackboard Collaborate (which has recently brought to- gether Illuminate and Wimba), Webex and Adobe Connect. Such tools have been developed with group collaboration in mind allowing multiple video feeds, shared workspaces (break- out rooms) and group decision-making tools like polling. Online synchronous learning environments have been refer- red to as web conferencing, webinars, webcasting or virtual classrooms amongst others. Underlying such terms is the idea of providing a face-to-face classroom-like environment online (Chatterton, 2010). However, de Freitas and Neumann (2009) prefer the term “synchronous audiographic conferencing” which they consider to be more neutral. For the purpose of this study we use the term “OSLE” and define it to be: a web-based, computer mediated communication (CMC) program, which enables any combination of learners, tutors, and subject experts to meet “virtually”, in “real time”, for the purpose of natural interaction and shared communication, in respect of a learning activity (Peacock, Murray, Girdler, Brown, Dean, & Mastrominico, 2011). Our emphasis is on interactive learning rather than using these tools in a broadcast mode for presentations and transmis- sion modes of teaching. We accept that the tools may be used in this way and in a broader way for e-administration, marketing (DiMaria-Ghalili, Ostrow, & Rodney, 2005), and research but this was not the focus of our study. However, like de Freitas and Neumann (2009), we accept that our proposed term, like those associated with learning with technology in general, is still very much “under discussion”. Online Synchronous Learning Environments in Higher Education A wide variety of case studies investigating the use of OSLEs have emerged over the last few years. These are at both post and undergraduate levels and are typically in Canada Figure 1. Example of communication opportunities via an OSLE. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1270  S. PEACOCK ET AL. (Abbass et al., 2011; Carbonaro, King, Taylor, Satzinger, Snart, & Drummond, 2008) Australia (Rushle & Loch, 2008) and the United States (Abbass et al., 2011; DiMaria-Ghalili, Ostrow, & Rodney, 2005; Laubach & Little, 2009; McBrien & Jones, 2009; Dammers, 2009). Such studies have focussed predominantly on supporting distance learners in remote geographic locations (Abbass et al., 2011; DiMaria-Ghalili, Ostrow, & Rodney, 2005) but blended learning examples are now appearing (Carbonaro, King, Taylor, Satzinger, Snart, & Drummond, 2008; Laubach & Little, 2009; McBrien & Jones, 2009). There are also a few examples in which an OSLE is used to connect learning for face-to-face and distance students. In such cases, some students are situated physically with the tutor whilst others online are connected from either a different campus or from their home (Laubach & Little, 2009). OSLE case studies are in subjects as diverse as: psychotherapy (Abbas et al., 2011); nursing (Di- Maria-Ghalili, Ostrow & Rodney, 2005); education (McBrien & Jones 2009); health (Carbonaro, King, Taylor, Satzinger, Snart, & Drummond, 2008; Valaitis, Akhtar-Danesh, Levinson, & Skylar, 2009; Wainman, 2007); sociology (Laubach & Little, 2009); mathematics (Skylar, 2009); psychology (McBrien & Jones, 2009); and music (Dammers, 2009). Usage is varied, ranging from online tutorials, seminars and lectures, to sup- porting mentoring, coaching and virtual office hours, as well as providing access to guest speakers (Chatterton, 2010). In the case studies mentioned previously, learners reported finding OSLEs very convenient, improving access to study, reducing travel time (and associated costs) and having envi- ronmental benefits (DiMaria-Ghalili, Ostrow, & Rodney, 2005; Chatteron, 2010; Abbass et al., 2011; McBrien & Jones, 2009; Dammers, 2009). Critically, OSLEs were perceived to offer a friendlier, warm, sociable learning environment helping to alle- viate feelings of isolation commonly reported by students using asynchronous environments. Learners particularly welcomed the opportunities for real-time visual interactive discussions with tutors and peers which sometimes lead to the development of an online learning community (Porto, 2006; Chatteron, 2010; Abbass et al., 2011; Carbonaro, King, Taylor, Satzinger, Snart, & Drummond, 2008). Students liked the opportunities for im- mediate clarification and feedback resulting in improved under- standing (DiMaria-Ghalili, Ostrow, & Rodney, 2005; Ostrow & DiMaria-Ghalili, 2005; Olaniran, 2006; Skylar, 2009). Increa- sed learner arousal, motivation, participation, interaction and engagement have been reported as well as improvements in critical decision-making and reflective skills (Porto, 2006; Fal- loon, 2011; Abbass et al., 2011). Recording of sessions was notable in supporting reflection and review at a time and pace convenient for learners (Carbonaro, 2008; Laubach & Little, 2009). Students also felt using the OSLE had improved tech- nology skills (Skylar, 2009; Falloon, 2011) and confidence in communication skills in a different media (Carbonaro, 2008). Such skills could be readily applied in the workplace (Ostrow & DiMaria-Ghalili, 2005). However, many technical challenges remain with use of OSLEs. These are cited all too often in the case studies and include: poor access to appropriate, reliable equipment; fire- walls limiting access to OSLEs; poor audio and video function- ality because of time lag and poor and/or variable network con- nectivity; lack of institutional funding for appropriate equip- ment, software and support (Abbass et al., 2011; Laubach & Little, 2009; Butler & Sullivan, 2007; Falloon, 2011). Conse- quently, many tutors and students are online at least 30 minutes prior to a session to ensure technical hitches are resolved. The impact is that many distance learners have felt more rather than less isolated. Other challenges relate to the demands placed on users of the system compared with face-to-face teaching. For tutors, this has meant more thorough planning, for example, in the organisation and running of group tasks in OSLEs (Dammers, 2009; Falloon, 2011). It has also challenged tutors to communicate and prob- lem solve in a wider range of subjects, including technical ones since university technical support is often not available for sessions which typically occur in the evening and at the week- end (Laubach & Little, 2009). Greater flexibility is also re- quired to adjust and cope with last minute changes due to the technology. Consequently, many tutors have fallen back on the familiar and comfortable broadcast approach to using OSLEs rather than exploiting the interactive group opportunities pre- sented by the tools (Porto, 2006; Butler & Sullivan, 2007; Chat- teron, 2010; Falloon, 2011). For learners too there are challenges. Many stated that even when OSLEs did work, they missed “human interaction”— there was still a sense of distance and disconnectedness (Mc- Brien & Jones, 2009; Dammers, 2009; Chatterton, 2010). Lear- ners often found it difficult to accommodate specific times for OSLE meetings when located in different time zones (Skylar, 2009; Falloon, 2011; Abbass et al., 2011) and there was a re- luctance to use OSLEs in a public place such as an Internet café (Cornelius & Gash, 2012). Furthermore, learners found it more difficult to engage in dialogue stating that they were too scared to ask questions, lacked knowledge of the subject area or nee- ded time to reflect. Such issues inhibited engagement (Falloon, 2011; McBrien & Jones, 2009). Many compared the dynamic communication in face-to-face learning with that in an OSLE and found it wanting. The Performing Arts and Online Synchronous Learning “Performing arts” is an umbrella-term for subjects including performance, drama, dance and their production and manage- ment. By nature, interdisciplinary, the boundaries of these sub- jects are particularly fluid because they call heavily on a range of media, digital arts and emerging technologies (Quality As- surance Agency for Higher Education, 2007). Consistent across most courses are the challenges presented due to the rehearsal- based nature of the subject and the importance of visual com- munication. Nevertheless, like other subjects, students will spend long periods physically located away from the institution for placement experiences and also for dissertation completion. There are few examples in areas related to performance. One notable example is in music when trumpet lessons were con- ducted through Skype (Dammers, 2009). The small study de- monstrated that it was indeed possible to teach at a basic level but also that there were limitations especially since the tech- nology did not support the tutor and learner playing together in time. However, it was accepted that: Synchronous online instruction is likely to expand and sup- plement music instruction but not revolutionize it. (Dammers, 2009: p. 22). Videoconferencing, however, has been trialled in the per- forming arts. The ANNIE (Accessing and Networking with National and International expertise) Project utilised both syn- chronous (videoconferencing) and asynchronous environments Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1271  S. PEACOCK ET AL. in theatre studies to support research-led teaching and access to national and international experts (Childs, 2003). Challenges included lack of gestural cues due to restricted views, time delays and the difficulty of working with large groups. How- ever, in both small and large group sessions, the level of learner and tutor concentration was elevated and tutors reported that multi-site tutoring sessions were more focused and democratic. Childs (2003) suggests that the lack of a tutor’s physical pres- ence appeared to make students focus their attention more than in traditional face-to-face sessions. Two other examples report use of videoconferencing for dance in rural areas. The Performance Lab (TPL) in Minnesota used elaborate set ups of equipment including fixed and hand- held cameras to enable students’ movements to be filmed from a variety of angles. Students liked to “…see themselves being corrected from three dimensions” (Janson, 2004: p. 47) and despite sound delays and loss of visual signal were positive about their experiences and impact on learning (Janson, 2004). In another example, videoconferencing provided opportunities for students to interact with national specialists without having to travel away from the classroom or studio (Parrish, 2008). Pedagogical Frameworks as Evaluative Tools to Explore Tutor and Student Experiences of Learning in OSLEs Whilst case studies reviewing OSLE-usage in tertiary educa- tion have regularly appeared over the last ten years, it is only recently that pedagogical frameworks and models have been used as tools to evaluate synchronous learning environments. Most notable has been Moore’s (1993) theory of transactional distance. Predominantly used in distance education, it considers the “sense of distance” and “disconnectedness” a student feels during the learning process (McBrien & Jones, 2009: p. 3). Al- though extremely illuminating as the basis for evaluation of studies, some have found this model requires re-thinking espe- cially since technologies such as synchronous online learning environments were not available when the model was originally conceived (Falloon, 2011; McBrien & Jones, 2009). de Freitas and Neumann (2009) provide an extensive over- view of pedagogic strategies which have been or could be broadly applied to OSLE-type technologies. They specifically focus on the Community of Inquiry model of Garrison and Anderson (2003) with its emphasis on interaction, discourse and a collaborative constructivist view of learning and teaching. This conceptual framework has been used extensively to inter- pret findings in e-learning (Garrison, 2011). The framework proposes three elements which harness the benefits of working online (distance and blended) and address the issues of the iso- lated learner. Strongly influenced by the work of Dewey, Garrison defines an online community of inquiry as: a group of individuals who collaboratively engage in pur- poseful critical discourse and reflection to construct meaning and confirm mutual understanding. (Garrison, 2011: p. 15). Garrison and Anderson (2003) believe learning and teaching to be a complex, iterative interplay between individual, per- sonal meaning making and the social environment: While knowledge is a social artefact, in an educational con- text, it is the individual learner who must grasp its meaning or offer an improved understanding. (Garrison, 2001: p. 13). At its heart, for Garrison and Anderson (2003) the educa- tional experience consists of: The private personal experience in which the individual is constructing and reconstructing knowledge; The social experience in which the individual is refining and confirming their developing knowledge through dis- course with a community of learners. The learning environment, as a consequence, must facilitate individual knowledge construction and meaning-making. It must also provide a supportive social environment in which di- vergent views, ideas and perspectives can flourish, be explored, investigated, reviewed, reflected upon and challenged. It is to this environment that learners must bring their emergent ideas and knowledge and discuss with other learners in the commu- nity. Over the last decade, the Community of Inquiry framework has been extended and refined (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007; Garrison, 2011). Currently the three overlapping elements which are the basis for the Framework are: Cognitive presence. This addresses how the learning envi- ronment supports the student to meet the learning outcomes of any educational experience. At its core is critical think- ing and reflection which allows the learner to probe existing knowledge and build upon this to develop new knowledge (Garrison, 2011). This recursive process moves the learner from a state of puzzlement to potential testing of solutions but this is not a linear process and in some cases will not lead to resolution. Social presence. This refers to the opportunities available for learners to present themselves as “real” people in what- ever medium of communication is required (Garrison & Anderson, 2003). Indicators of social presence include: in- terpersonal communication, open communication and cohe- sive communication (Garrison, 2011). Teaching presence focuses on the design and management of the learning environment, facilitation of critical discourse and correction of misconceptions. Usually the tutor takes the lead in this presence but students too can support the teaching presence. Although originating from the analysis of text-based online communication, there are now many examples of the CoI being used to understand and evaluate blended learning (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). We hoped the Framework would provide the basis for an in-depth exploration of the potential of an OSLE in the performing arts to support learning. The basis of the Framework—the interplay between individual meaning-making and the social environment—is highly suitable for our case studies in the performing arts. The Study The aim of the study was to investigate whether, and in what ways, tutors and learners engage with online synchronous learning environments (OSLEs), to further our understanding of the role of OSLEs in learning and to develop practical guide- lines. An in-depth, comparative study of tutor and learner ex- periences of using an OSLE was conducted in order to explore if OSLEs could enhance the learning environment for heavily blended learning courses where tutors and learners were fre- quently off-campus. The study was conducted at Queen Margaret University (QMU), Edinburgh, Scotland, over a period of nine months. QMU is a small institution which gained University title and Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1272  S. PEACOCK ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1273 MP3 or MP4 files. Figure 2 provides an example of the Wimba interface with a video screen in use. For all three of the case studies, students and tutors were introduced to the OSLE early in the academic calendar. moved to a new campus in 2007. Most undergraduate pro- grammes offered at QMU involve four years of study and stu- dents typically start such courses from the age of 17 years on- wards; each year of study in a programme is referred to as a level. Many of the students participating in this study were located at a distance from the institution at some stage of their programme. Similarly the tutors involved in the study were at times travelling and based away from the institution. So, al- though QMU was the physical setting for the study, in reality the OSLE itself was the virtual setting where much of the re- search data were collected. Context of Use Our OSLE was trialled within three programme areas for three very different purposes, as illustrated in Table 1. Method This was a qualitative study and followed a mixed method approach to data collection. A collective case study design (Stake, 2000) was employed which enabled a holistic examina- tion of three very different learning and teaching contexts which were making use of an OSLE within the subject area of performing arts. Qualitative research is recognised as having the strength of generating rich data (Glazier, 1992) and it was anticipated that studying these cases in-depth would enable generalisations from our findings to be applied to a wider population (Stake, 2000; Bryman, 2001), for example, across other performing arts subject areas. Each case was selected purposefully on the basis of relevance to the focus of our re- search (Gomm, Hammersley, & Foster, 2000). To assist in de- termining relevance, tutors from five programme areas were invited to complete an online questionnaire at the preliminary stage of the project in order to gather background information about each potential case and cohort, as well as expectations regarding use of the OSLE. Three cases were selected purpose- fully on the basis of these data. Two were discounted as either The System The OSLE used during this study was Wimba Classroom version 5 and was hosted on a server provided by Wimba in the United States of America. Wimba Classroom allows learners and tutors to log into a secure, online classroom, where audio and digital materials, such as PowerPoints, images, WORD and EXCEL documents, websites, and video clips can be shared and discussed in large plenary groups or in smaller breakout groups. Tutors and students can talk to each other in real time through the OSLE interface and can supplement this using a text chat tool. Students can indicate when they wish to ask a question, when they understand an explanation, or when they are confused, by selecting an appropriate symbol, for example, a “thumbs-up” or a “thumbs-down”. A video of the speaker is shown, but it is not possible in this particular OSLE system for videos of other participants logged into the session to be shown at the same time. Sessions can be recorded and archived for later use, and either accessed through a URL or downloaded as Figure 2. Example of Wimba interface with video screen in use.  S. PEACOCK ET AL. the tutors did not wish to engage with an OSLE after further discussions and/or felt that the use of OSLE was inappropriate with most students being campus-based. Ethical approval was gained from the institution. Three methods of data collection were employed in order to access a wide range of perspectives regarding use of the OSLE and these were: self-completion questionnaires, the recording of video diaries by participants, and semi-structured interviews. Pre- liminary, background data were gathered from students and tutors via web-based self-completion questionnaires. For the tutors this related to their anticipated use of the OSLE within their programme area, perceptions regarding the benefits and limitations of using an OSLE tool, and also details of any prior experiences they may have had in using synchronous environ- ments. The student questionnaire data provided an indication of their levels of computer skills and experience of synchronous environments generally and also provided an insight into the students’ perceptions regarding the introduction and use of the OSLE. Tutors and students were invited to create video diaries within the OSLE about their experiences of using the OSLE. Partici- pants were requested to archive their diaries and to notify the researcher when a diary was available. It was hoped that using the OSLE to record diary accounts would be a convenient way for tutors and students to reflect on their experiences and that using the same OSLE would enable diaries to be created as soon after actual episodes of use as possible, prompting recall of particular features or issues worthy of discussion. The re- searchers anticipated that gathering audio and visual responses together in a diary form would assist them in gaining a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under investigation, as well as aiding engagement with data. Interview data were gathered via the OSLE since it was con- sidered to be convenient for the researcher to meet with the tutors and students in this way for interview, particularly as several participants were away from the institution. It was be lieved that using the OSLE for the purpose of conducting an interview would aid the participants in recalling their experi- ences of using the OSLE within the learning and teaching con- text and enable them to demonstrate ideas and opinions more easily. Also it was hoped that using this approach would assist the researcher in experiencing the environment under investiga- tion and developing an understanding of its use. Further infor- mation about using OSLEs as a research tool is available else- where (Murray & Peacock, 2012). Participation in the research was voluntary and as Table 1 illustrates, only a small number of students participated. Al- though all four tutors (including the two tutors in case study 2) wished to use the OSLE with their students, some students preferred the telephone and email whilst others lived near to the University and wished for a face-to-face meeting with their tu- tors. Other students used the OSLE but did not opt to be inter- viewed or to record a video diary (see Table 2). Data Analysis The data analysis was undertaken in two stages. Analysis took place as soon as possible after data were collected to assist subsequent stages of data collection. First, an iterative and interpretive process of analysis was employed, enabling the value and shortcomings of using an OSLE to be identified from the tutor and student perspectives. Data were reviewed by two members of the research team to facilitate cross checking and to increase the quality and rigour of the findings (see Figure 3). It was only later that data were interrogated again using the CoI framework for evaluation. In this case, one researcher re- visited the data collected and reviewed looking for key themes that resonated with the three elements of the CoI as undertaken in previous studies (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). A full outline of the method and analysis is available else- where (Peacock, Murray, Girdler, Brown, Dean, & Mastromi- nico, 2011). Findings and Discussions In this section, we report the findings of the study and then discuss them in relation to the Community of Inquiry frame- work. Our study demonstrates that OSLEs can be used to sup- port learning in three diverse case studies in performing arts. In all three case studies, the tutors and students were positive about using the OSLE and about the role of the OSLE in main- taining contact between students and tutors. For example, use of the OSLE helped maintain, to some degree, the learning connection which had been established in the face-to-face meetings: I always finished the session feeling that I’d made a connec- tion. There was a certain amount of intimacy there at a dis- tance if you like and therefore it was valuable to use (Tutor; Case study 1). Table 1. Context of OSLE use across the three case studies. Case study Programme and level of studyContext of use Tutor group Student location 1 MA Arts and Cultural Management PG level 2 For conducting mainly one-to-one tutorials and occasional group meetings between tutor and students in order to suppor dissertation completion. One tutor (m) · Greece (n = 1 f) · Bahrain (n = 1 f) · South Korea (n = 1 f) 2 BA (Honours) Drama and Theatre Arts UG year 3 · As a vehicle for students to demonstrate performance rehears- als with peers and tutors who were away from the institution; · As an environment for tutors to provide feedback to students on their performance rehearsals—both individually and i groups. Two tutors (1 f; 1 m) · Edinburgh (n = 7) (5 f; 2 m) 3 BA (Honours) Performing Arts Management UG year 3 A means of providing one-to-one developmental sup ort fo students who were away from the institution on work place- ment experience. One tutor (m) · London (n = 1 m) · Edinburgh (n = 2) (1 f; 1 m) Note: PG = Postgraduate; UG = Undergraduate; f = Female; m = Male. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1274  S. PEACOCK ET AL. Figure 3. Overview of the data analysis process. Table 2. Demonstrating participant numbers for each data collection method. Questionnaires Video diaries Interviews Tutors n = 4 n = 3 n = 4 Students n = 5 n = 4 n = 5 The participants liked using the OSLE, and this was evident from the very first sessions. They found it was an easy to use, flexible, accessible and convenient tool, providing instant visual and audio communication between tutors and students, reflect- ing case studies reported in the literature (Porto, 2006; Dam- mers, 2009; Abbass et al., 2011, Falloon, 2011). [OSLES will] give us more flexibility. At the moment I have to fit those academic tutorials into a working day… my work- ing day can be really what I want so if a student wants to do a [session] with me at 7 o’clock in the evening, then I’m happy to do that, it’s part of my working day. You know, it gives me freedom to plan my week and gives students freedom to plan those academic tutorials… It’s just shifting… boundaries shift- ing, perceptions shifting. I don’t see it as making work harder, making it more difficult. I see it as making things easier (Tutor 3; Case study 3). Moreover, the tutors believed that OSLEs had the potential to change significantly the educational experience for them—it offered a new and more exciting way, of doing the business of education in the 21st century—it was possibly a step-change. Such findings echo case studies previously cited such as Valaitis et al., 2007; Butler & Sullivan, 2007; McBrien & Jones, 2009; Reushle & Loch, 2008. The OSLE was considered to be a more dynamic, interactive, personal, student-centric, and fun learning environment, which could “free participants” from the constraints of the current physical learning environment of the campus in Edinburgh and help them to balance their varied work commitments and study/life responsibilities: It’s been of enormous benefit. Not only the new skills aspect of it which is enormously important, but for me as a human being and the work-life spans. It’s given a completely new di- mension to my working life which is quite phenomenal really… wherever anyone is in the world to be able to communicate and to teach students, to mentor students and to have that freedom away from the desk which is something we were promised for years would happen, has had a huge effect on my psyche. I feel very free, which is an extraordinary thing to say. I don’t feel chained to my desk.. (Tutor 3; Case study 3). All the tutors referred to the OSLE as empowering learners and perhaps providing learners with some measure of control and responsibility. In case study 2, for example, the tutors de- scribed when they first entered the online room whilst they were physically located in Italy and their students in Scotland. The tutors realised that the students had organised their physi- cal and online space, determined how they would run the ses- sion and how they would work with their tutors. Using the OSLE made the students think about how they wanted to use the tutors to meet the educational requirements for their studies and how they could engage in critical discourse with their tutors to check current knowledge and develop new understanding. This theme of empowerment, noted in other studies such as Olaniran (2006), was noticeable in the two other case studies where the tutors believed that the OSLE gave their learners “a sense of responsibility,” deciding when they wanted to contact their tutors and most importantly, what they wanted to discuss. This would provide a springboard for the tutors to facilitate a critical discussion which would allow the learner to refine and confirm their developing knowledge through discourse with themselves and in some cases, other learners. However, for some learners, the tutor noted, this sense of responsibility would take longer to develop than others. In some cases, as reported earlier in the literature review, the technology did impact on the learning and there was frustration at its lack of robustness and limited functionality. However, the tutors enthusiasm and commitment to using OSLEs remained throughout the study and most worked around the technology, similar to the examples reported in the study by Abbass et al. (2011), and there was an acceptance that the technology was improving significantly and quickly: as the technology improves the work will reap the benefits of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1275  S. PEACOCK ET AL. what we’ve been discussing, but it’s a slow start because that kind of quality holds us back at the moment (Tutor 2a; Case study 2). Although tutors and students were very positive about using OSLEs, it is important for us, as educators, to know how and in what ways using an OSLE facilitates individual knowledge construction and meaning-making. What, if any, impact did the OSLE have on the students’ learning? In the next section we use the three elements of the Community of Inquiry framework as the basis for our evaluation of learning in our three case studies. Cognitive Presence Not only did the instant audio and visual communication in the OSLE ensure that the strong learning connection made on campus could be maintained but this technology also facilitated dialogue for inquiry and debate which tutors felt supported the students in acquiring high-order knowledge. In two of our case studies, the tutors used the OSLE as a learning space where students could discuss with them and their peers their emergent understanding and engage in debate and sharing: Sharing… in a way that’s what our conversations are about, I’m sharing my thoughts on their work and they were sharing their thoughts with me, but you can share work, you can share images, pictures and desktops. It’s a place for sharing quite easily and I think for drama teachers that’s probably quite a nice word to hear (Tutor 1; Case study 1). For the future, as with the video-conferencing case studies cited earlier (Parrish, 2008), it was also anticipated that use of an OSLE would improve access to, and dialogues with, experts which would allow students to interrogate and extend their existing knowledge: And I suspect this is why the project has been so fascinating, because the doors it opens … the choices, being able to have students speaking to practitioners all over the world is phe- nomenal and I suspect that that’s… I mean obviously it will be the same in business and any other aspect… health sciences as well, being able to speak to practitioners from all over the world without having to fly them in. Having that access, in- stantaneous access is pretty amazing (Tutor 3; Case study 3). The OSLE was also used asynchronously as a reflective tool. Synchronous online learning is often praised for its immediacy of response and faster pace but criticised for reducing the op- portunities for reflection, unlike text-based asynchronous communication. In case study 2, working with the archive tool in the OSLE, individual learners could revisit their recordings of performances, reflect upon these, create online reflective video diaries in which they articulated their developing under- standing and then use these as a springboard to prepare for discussions with tutors and peers. This helped the learners in the performing arts to see their work as work in progress which they would then move forward with after receiving feedback and reflection: They have to develop their work in… solitude. They’re in a sort of loneliness which provides the chance for them to grow independently, so we need to look at that material maybe af- terwards… (Tutor 2b; Case study 2). The OSLE was supporting both private reflection and public discourse (Garrison, 2011) particularly through the use of the archive tool as explained by Tutor 2a: the possibility of archiving, revisiting work, storing it, going back and being able to examine in detail, in our own time, in our own place… that’s been extraordinarily valuable and has set off a train of thoughts about the potential for the future (Tutor 2a; Case study 2). In some cases, the OSLE impacted negatively on cognitive presence especially through the requirement for turn-taking when speaking. Participants compared the OSLE with Skype, where turn-taking is not required and where more spontaneous communication is supported: When I recently used Skype I found … I didn’t have to push a button—they could already hear me and it was a lot more re- laxed—it was like you are just in a room chatting instead of having to push the button down …that way I guess I could make notes as well, instead of having to reach over and press a button—it would be a bit more relaxed (Student 5; Case study 3). Tutors disliked the turn-taking and felt that they needed the same functionality in Skype where they “…could have those kinds of overlapping conversations that make human conversa- tion human.” (Tutor 2a; Case study 2) Precious time for peer and tutor interaction was also wasted due to the time required to prepare and log into the system: I know we’ve had many sessions which took us a good 15 or 20 minutes just to set up things ready to use it in the room, …(Tutor 2a; Case study 2). Also, some students and tutors found that the system was not intuitive and the interface was often described as “overwhelm- ing” resulting in less frequent use of the system. Here the stu- dent describes trying to archive: it took me a long time to figure out… how to record because it wasn’t clear and as I said the tutorials didn’t help because they are like half an hour long—each one of them and you don’t know where the information you’re looking for is because there are loads of different tutorials and it could take days until I find the information I was looking for. (Student 1; Case study 2). Such technical issues limited the quality of the discourse (in- ternal and external) and impacted on learning. In case study 2, where the OSLE was used for performance practice and group sessions, specific challenges emerged; however, for each issue, the tutors found benefits by addressing the challenges: Physicality constraints. It was not possible for tutors to make physical corrections of students’ poses, such as moving an arm into an alternative posi- tion. The tutors initially found this restrictive as stated in the early video-conference examples (Parrish, 2008; Janson, 2004). However, after a few sessions, the tutors altered their commu- nication style and found they could demonstrate the moves through the OSLE. Constrained performance space due to the camera and what the camera could show. Tutor 2 recalls that the learners had to remember to organise their performance space for the camera. This meant that ulti- mately the students limited which aspect of their performance was recorded for feedback through an OSLE. The tutors re- minded the students that this was useful experience as they might frequently in the future be working with cameras and not performing for a live audience. Equality of communication with large groups. As stated by Tutor 2a: this needed to be considered in the planning process: Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1276  S. PEACOCK ET AL. If somebody isn’t sitting next to the computer, say if you have a group of seven, only one or two people can have their hands on the talk button. If it’s a discussion with us it makes life po- tentially difficult if you wish to interject or how do you put your hand up? Do you physically put your hand up? …but again if your colleagues are sitting in a place where they can’t see you… there are difficulties… (Tutor 2a; Case study 2). Social Presence The ability to see and talk with the tutor or students instan- taneously was crucial for all: they could see each other as ‘real’ people with whom they could discuss their work, their ideas and their developing understanding: We felt good about the session—it was certainly good to connect and see each other and speak to each other. In a way it was like a phone call, but was a wee bit more personal if you like (Tutor 1; Case study 1). The immediacy of the communication link allowed the tutor to check directly if their message had been understood and to probe further or progress the discourse as appropriate, mirror- ing findings reported in the Annie project (Childs, 2003) and Abbass et al.’s case study (2011). It seemed that the sessions had enhanced the working relationship, maybe through helping the tutors gain a better insight into the learners’ environment and getting “a sense of their students as people” (Tutor 1; Case study 1). Tutor 1 discusses the impact of talking to his students when they were celebrating New Year in South Korea, or ex- periencing the riots in Athens; it provided him with a sense of where his students were and what they were experiencing. These discussions were also relevant to their area of study. The facility to hear and see instantaneously also differenti- ated the OSLE from other forms of communication, such as telephone or email: “it helps to use your visual senses as well as just listening” (Tutor 1; Case study 1). In most cases the immediacy and visual/audio communication channels helped build and maintain social presence: I can use email to ask his ideas, but when I’m using Wimba he can explain his ideas … why should I go ... how could I… It’s different, he can use paper and he can use the letter, but when he speak to me and we seeing faces, with the smile, then it’s more… we’re close and it’s helpful using Wimba with the movie (Student 3; Case study 1). Using the OSLE also helped to remind the students of work- ing and studying in an educational environment. It removed the disconnectedness often referred to in distance learning pro- grammes, reinforcing what was expected of them as students studying at a university and their responsibilities to other learn- ers. However, the technology could become a barrier to learn- ing and disrupt the development of social presence. In all three cases, technical challenges were experienced, most notable of which was poor video and audio quality: The quality issues … they’re off-putting. You don’t want to be looking at blurry images or not be able to make out half the words, to struggle to hear what your colleagues or lecturers or the performers in the space are saying or doing, makes the whole exercise somewhat redundant (Tutor 2a; Case study 2). The quality was very poor and her video appeared for one second only. The sound quality was also very poor (Tutor 3; Case study 3). Although Abbass et al. (2011) state that there is little re- search evidence that using web-conference technology causes learner anxiety, some of our learners did not relish the idea of seeing themselves on a video. Furthermore, after discussions with students, tutors became very aware that they could be talking with students in their bedrooms since this was where students’ computers were often located. For some this could be a barrier to using OSLEs: You are coming into someone’s space and you’re aware of, you know, that you might have a bedroom or sitting room that’s piled high with things. You know, you wouldn’t necessarily invite someone into that… you’d have a good old tidy …it’s pretty much going into someone’s personal space. (Tutor 3; Case study 3). Tutor Presence Throughout the interviews and in the diaries, the four tutors continuously reflected on how use of the OSLE impacted on the way they worked with their learners and how they organised the learning environment. They were considering if, and in what ways, the OSLE affected “teaching presence” and more pre- cisely how it changed their role from lecturer to facilitator. As Cornelius and Gash state: Teachers taking on the challenge of virtual classrooms should be prepared to be unsettled by the experience; they need to be ready to question and reflect on their practice…” (Corne- lius & Gash, 2012, p. 4). We have summarised our tutors’ reflections into three sec- tions, mirroring the three indicators used by Garrison and Anderson (2003) to describe tutor presence. 1) The design and organisation of the learning environment Tutors particularly reflected on how the OSLE impacted on: Preparation. In Falloon’s study (2011), tutors were not sufficiently prepared for the online environment and so read from notes and did not plan for interactive sessions. In comparison, our tutors to support student learning prepared and organized highly interactive sessions and tasks, often mirroring the “practical inquiry” model suggested by Gar- rison (2011). Students were expected to ask, answer, chal- lenge, respond and debate as in their face-to-face sessions. In case study 1, the tutor would send comments on drafts of the dissertations and then plan how he would probe the stu- dents' understanding. In case study 2, the tutors explained what they wanted the sessions to achieve but the students determined how they wanted to use the OSLE for this. Also, because the students already knew each other and their tu- tors, there was less time required for the ‘participatory moves’ so common in asynchronous communication where by posts are made to establish a learner’s presence (Paulus & Phipps, 2008). However, in the first few sessions, tutors were unprepared for the technical issues that they needed to handle and troubleshoot (as noted in previous case studies), for example, explaining to students how to activate their webcams. Pacing. Tutors became increasingly aware that working in the online environment was very demanding: it was more intense and required more concentration mirroring other studies such as the Annie project (Childs, 2003). Therefore, tutors would ensure that the length of sessions was carefully organized with, if necessary, breaks and break-out sessions. 2) The facilitation of discourse Reflecting their approaches to learning and teaching, in all three case studies it could be seen that the tutors had planned Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1277  S. PEACOCK ET AL. that the OSLE sessions should support various types of dia- logue enabling the development of social and cognitive pres- ences (Garrison, 2011). Often sessions would start with general conversations, for example about the weather, but this would rapidly progress to focussed discourse about their studies. In essence the discussions would move through and between the four types of dialogue outlined by Burbules (1993): casual con- versation; inquiry; debate and instruction, even in case study 3. All of the tutors had assumed that the OSLE technology would be an easy medium to facilitate sustained discourse with their students and one in which the learners would be happy to use for discussion. They were, however, surprised and unpre- pared when the students were initially uncomfortable at using the technology for learning. The learners were looking to the tutors to “… lead them into the OSLE and make them feel com- fortable” (Tutor 1; Case study 1). Thus, in their interviews, the tutors started to reflect upon their communication skills which had been developed and honed in the more traditional face-to- face learning environment and considered how they needed to refine these for the online synchronous learning environment: it’s different than a classroom and it can throw up some dif- ferent useful pointers to your own communication and lecturing skills (Tutor 1; Case study 1). 3) Direct instruction In the three very different case studies, the tutors wanted to use the OSLE as a tool to correct misconceptions and misun- derstandings. Most felt that the OSLE was much better at this than other synchronous alternatives such as Skype, or the tele- phone, or asynchronous options such as email. Nevertheless, the tutors realised that the OSLE impacted on how they tutored students; it was important that communications were more pre- cise and less verbose: Probably the main aspect of learning that comes up here is about communication skills and lecturing skills. The talking skills, the listening skills… and that is because it is similar to the classroom situation, but the pace is quite different and so you find that you need to express yourself perhaps a bit more clearly, or consider what you’re saying a bit more because feedback does come back and they can ask you questions (Tutor 1; Case study 1). Also, as mentioned earlier, tutors had to convey information which they would normally support with non-verbal communi- cation or physical correction, for example, tutors in case 2 had to explain how an arm needed to be moved and to demonstrate whereas in the face-to-face environment they would have been able to physically move the learner’s arm. All the tutors considered that working through the OSLE had impacted on the way they worked in face-to-face sessions. This is known as the “reverse impact” phenomenon (Cornelius & Gash, 2012) whereby improving approaches to learning and teaching online leads to enhancements in face-to-face learning environments. Limitations Our small collective study had limitations such as low levels of student participation at each stage of the data collection as well as technical issues in using the OSLE which impacted on data collection in relation to the creation of video diaries. These are described elsewhere (Peacock, Murray, Girdler, Brown, Dean, & Mastrominico, 2011). Such small numbers meant that we could not do justice to the notion of exploring a true com- munity of inquiry as outlined by Garrison and Anderson (2011) and thus, can only hint at the possibility of the role of an OSLE in supporting a group of learners engaging in critical discourse and reflection. The CoI framework nevertheless provided us with an evalua- tive tool that demonstrates the learning that had been supported when using the OSLE. However, one notable exception was the lack of consideration by the Framework to multi-modality which perhaps reflects the development of the CoI from asyn- chronous online discussions. However, the theory of multi- modality would seem highly applicable to OSLEs (de Freitas & Neumann, 2009). As reported by McBrien & Jones (2009), this issue was raised by a tutor who stated: one [problem] was the confusion that resulted from too many simultaneous interactions such as audio, typed chat, and white- board/PowerPoint or group questions that could be answered using emoticons, Yes/No, or multiple choice responses. (Mc- Brien & Jones, 2009: p. 29). This is echoed in our study: There’s a lot to look at and I felt like I was an air traffic controller where I had to look out the window, or in this case look at the students and looking could mean communicating with the students as well as keep an eye on all the buttons and gadgets… (Tutor 1; Case study 1). Future work on OSLEs will certainly need to explore this area in more depth. It is also suggested that the 34-item Com- munity of Inquiry framework survey instrument could be used amongst others to interrogate data in future studies (Garrison, 2011). Conclusion Online synchronous learning environments are an emerging and rapidly advancing technology which have potential to con- nect our learners and tutors wherever they may be and whatever their personal responsibilities and commitments. Our findings concur with many other case studies that OSLEs can offer a lively, personal and dynamic learning space. For our rehearsal- based case study 2, the use of the OSLE echoed many of the findings of the ANNIE project and video-conference projects within dance but each of the challenges could be addressed and positively so. However, use of the OSLE also had an unex- pected benefit since it allowed students to record their rehears- als and then watch these alone and/or with their tutors, sup- porting both personal reflection and social discourse. Tutors also felt that the OSLE gave the learners vital experience of working in a different media which was essential for students in drama reflecting the fluidity of the subject and importance of technology: Certainly for drama students working with media, especially new media for our particular specialism which is in Contem- porary Performance, looking at experimental and often hybrid performance forms which involve multi-media work, it’s very important indeed, so getting them to become hands-on and empowered with technology which allows them to manipulate media, manipulate the way they present themselves in media, learn how that impacts on their performance work and how they can mix and play with technology within their live work, is very exciting indeed which is one of the things which led us to want to be a part of this project in the first place. As a result, the students this year have had a much more fluid relationship with technology. (Tutor 2a; Case Study 2). By using the CoI framework, we could explore in greater Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1278  S. PEACOCK ET AL. depth the potential of an OSLE to support learning in the per- forming arts. The basis of the framework—the interplay be- tween individual meaning making and the social environment— was highly suitable for our subjects. We found that the OSLE provided a convenient and easy to use tool, which enabled our tutors to reach out to their learners and develop a strong social presence, supporting learning wherever the students and tutors were physically located. The framework also helped us to see some of the issues where the OSLE challenged learners and tutors, for example, not everyone liked the video option, while the variable quality of the audio and video meant that the OSLE sometimes restricted social presence. The turn-taking necessary to avoid audio “squeal” also limited spontaneous debate and discussion where a community could probe a learner’s emer- gent understanding. Exploring the tutor presence with regard to the CoI was particularly useful since it provided structure to interrogate our findings and supported the development of guidelines for using OSLEs which are available elsewhere (Murray & Peacock, 2011). Research in this area is still in its infancy (Skylar, 2009). We suggest that further studies are needed to explore additional ways in which OSLEs can be used to support learning and teaching, especially in other subject areas, and potentially in conjunction, with a wider range of media, such as mobile tech- nologies. It is also recommended that longitudinal studies are undertaken which can chart the development of a more com- plex understanding of OSLEs and their role in the learning and teaching process. Furthermore, one of the most challenging areas will be the use of OSLEs or equivalent for merging face-to-face and online students in the virtual and physical classrooms. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those who have contrib- uted towards this project. In particular, we would like to thank our funders, PALATINE, the Higher Education Academy Sub- ject Centre for Dance, Drama and Music, as well as the students and tutors at Queen Margaret University who have generously given their time to participate in this study. We would also like to thank colleagues at the Higher Education Academy (HEA), the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC), and the Re- gional Support Centre (RSC) Scotland North and East, who have provided valuable guidance and support. We especially extend our thanks to all those who attended the dissemination event ‘Crossing Virtual Boundaries—Teaching and Research with Online Synchronous Learning Environments’ at the e-Sci- ences Institute, Edinburgh on 10th June 2011. Finally, we would also like to thank Dr Kate Morss and our colleagues in the Cen- tre for Academic Practice at QMU for their continued support. REFERENCES Abbass, A., Arthey, S., Elliott, J., Fedak, T., Nowoweiski, D., Markovski, J., & Nowoweiski, S. (2011). Web-conference supervision for ad- vanced psychotherapy training: A practical guide. Psychotherapy, 48, 109-118. doi:10.1037/a0022427 Browne, T., Hewitt, R., Jenkins, M., Voce, J., Walker, R., & Yip, H. (2010). 2010 Survey of technology enhanced learning for higher edu- cation in the UK. URL (last checked 26 August 2012). http://www.ucisa.ac.uk/~/media/groups/ssg/surveys/TEL%20survey %202010_FINAL Bryman, A. (2001). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford Univer- sity Press. Burbules, N. (1993). Dialogue in teaching: Theory and practice. New York: Teachers College Press. Butler, J., & Sullivan, M. (2007). Pitfalls, perils, and profound pleas- ures of live elearning. Distance Learning, 4 , 31-36. Carbonaro, M., King, S., Taylor, E., Satzinger, F., Snart, F., & Drum- mond, J. (2008). Integration of e-learning technologies in an inter- professional health science course. Medical Teacher, 30, 25-33. doi:10.1080/01421590701753450 Chatterton, P. (2010). Designing for participant engagement with black- board collaborate. URL (last checked 26 August 2012). http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/elearning/Colla borateguidance/Blackboard%20Collaborate%20Good%20Practice% 20Guide.pdf Childs, M. (2003). E-tutoring in synchronous and asynchronous envi- ronments. Interactions Journal, 7. URL (last checked 26 August 2012). http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/services/ldc/resource/interactions/archiv e/issue20/childs Cornelius, S., & Gash, D. (2012). How do you know if anyone is there? Questions from teachers new to virtual classrooms. Educational De- velopments, 13, 1-7. de Freitas, S., & Neumann, T. (2009). Pedagogical strategies supporting the use of synchronous audiographic conferencing: A review of the literature. British Journal of Educational Technolo gy, 40, 980-998. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00887.x Dammers, R. (2009). Utilizing Internet-based video conferencing for instrumental music lessons. Applications of Research in Music, 28, 17- 24. doi:10.1177/8755123309344159 DiMaria-Ghalili, R. A., Ostrow, L., & Rodney, K. (2005). Webcasting: A new instructional technology in distance graduate nursing educa- tion. Journal of Nursi ng Education, 44, 11-18. Falloon, G. (2011). Making the connection: Moore’s theory of transac- tional distance and its relevance to the use of a virtual classroom in postgraduate online teacher education. Journal of Research on Tech- nology in Education, 43, 187-209. Garrison, D. R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century. A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-Learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. London: Routledge/Falmer. doi:10.4324/9780203166093 Garrison, R., & Arbaugh, J. (2007) Researching the community of in- quiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10, 157-172. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001 Glazier, J. D. (1992). Qualitative research methodologies for library and information science: an introduction. In J. D. Glazier, & R. R. Powell (Eds.) Qualitative research in information management (pp. 1-13). Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited. Gomm, R., Hammersley, M., & Foster, P. (2000). Case study and gen- eralization. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, & P. Foster (Eds.), Case study method (pp. 98-115). London: Sage. Janson, M. (2004). Distance makes the dancer grow stronger. Dance Teacher, 26, 46-48. JISCinfoNet. (2012). Effective use of virtual learning environments. URL (last checked 1 September 2012). http://www.jiscinfonet.ac.uk/InfoKits/effective-use-of-VLEs Laubach, M., & Little, L. (2009). Trials and triumphs: Piloting a web conference system to deliver blended learning across multiple sites. Journal of the Research Centre for Educational Technology, 5, 56- 67. McBrien, J., & Jones P. (2009). Virtual spaces: Employing a synchro- nous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10, 1-17. Murray, S., & Peacock, S. (2011). Recommendations and guidelines for tutors using online synchronous learning environments (OSLE). URL (last checked 29 August 2012). http://www.qmu.ac.uk/palatine/documents/KeyRecommendations.pdf Murray, S., & Peacock, S. (2012). The video diary as a method of data collection in qualitative educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. In progress. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1279  S. PEACOCK ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1280 Olaniran, B. (2006). Applying synchronous computer-mediated com- munication into course design: Some considerations and practical guides. Campus-Wide Information Syst e m s , 23, 210-220. doi:10.1108/10650740610674210 Ostrow, L., & DiMaria-Ghalili, R. A. (2005). Distance education for graduate nursing: one state school’s experience. Journal of Nursing Education, 44, 5-10. Parrish, M. (2008). Dancing the distance: iDance Arizona videoconfer- encing reaches rural communities. Research in Dance Education, 9, 187-208. doi:10.1080/14647890802087811 Paulus, T., & Phipps, G. (2008). Approaches to case analyses in syn- chronous and asynchronous environments. Journal of Computer- Mediated Communication, 13, 459-484. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00405.x Peacock, S., Murray, S., Girdler, S., Brown, D., Dean, J., & Mastro- minico, B. (2011). An exploration of learner and tutor experience in using online synchronous learning environments (OSLEs) across disciplines within the School of Drama and Creative Industries. URL (last checked 26 August 2012). http://www.qmu.ac.uk/palatine/documents/OSLE.pdf Porto, S. (2006). Synchronous online conferencing. DE Oracle @ UMC. URL (last checked 26 August 2012). http://deoracle.org/online-pedagogy/synchronous-communication/sy nchronous-conferencing.html Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (2007). Drama, dance and performance. URL (last checked 26 August 2012). http://www.qmu.ac.uk/futurefocus/EmployabilityProfiles/Dance%20 Drama%20and%20Performance%20Employability%20Profile.pdf Rogoza, C. (2007).Wimba live classroom. A case study of diffusion of innovation. Distance learning, 4, 48-56. Rushle, S., & Loch, B. (2008). Conducting a trial of web conferencing software: Why, how, and perceptions from the coalface. Turkish On- line Journal of Distance Education, 9, 19-28. Stake, R. (2000). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 435-454). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Skylar, A. (2009) A comparison of asynchronous online text-based lec- tures and synchronous interactive web conferencing lectures. Issues in Teacher Education, 18, 69-84. Valaitis, R., Akhtar-Danesh, N., Eva, K., Levinson, A., & Wainman, B. (2007). Pragmatists, positive communicators, and shy enthusiasts: Three viewpoints on web conferencing in health sciences education. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 9. URL (last checked 26 Au- gust 2012). http://www.jmir.org/2007/5/e39

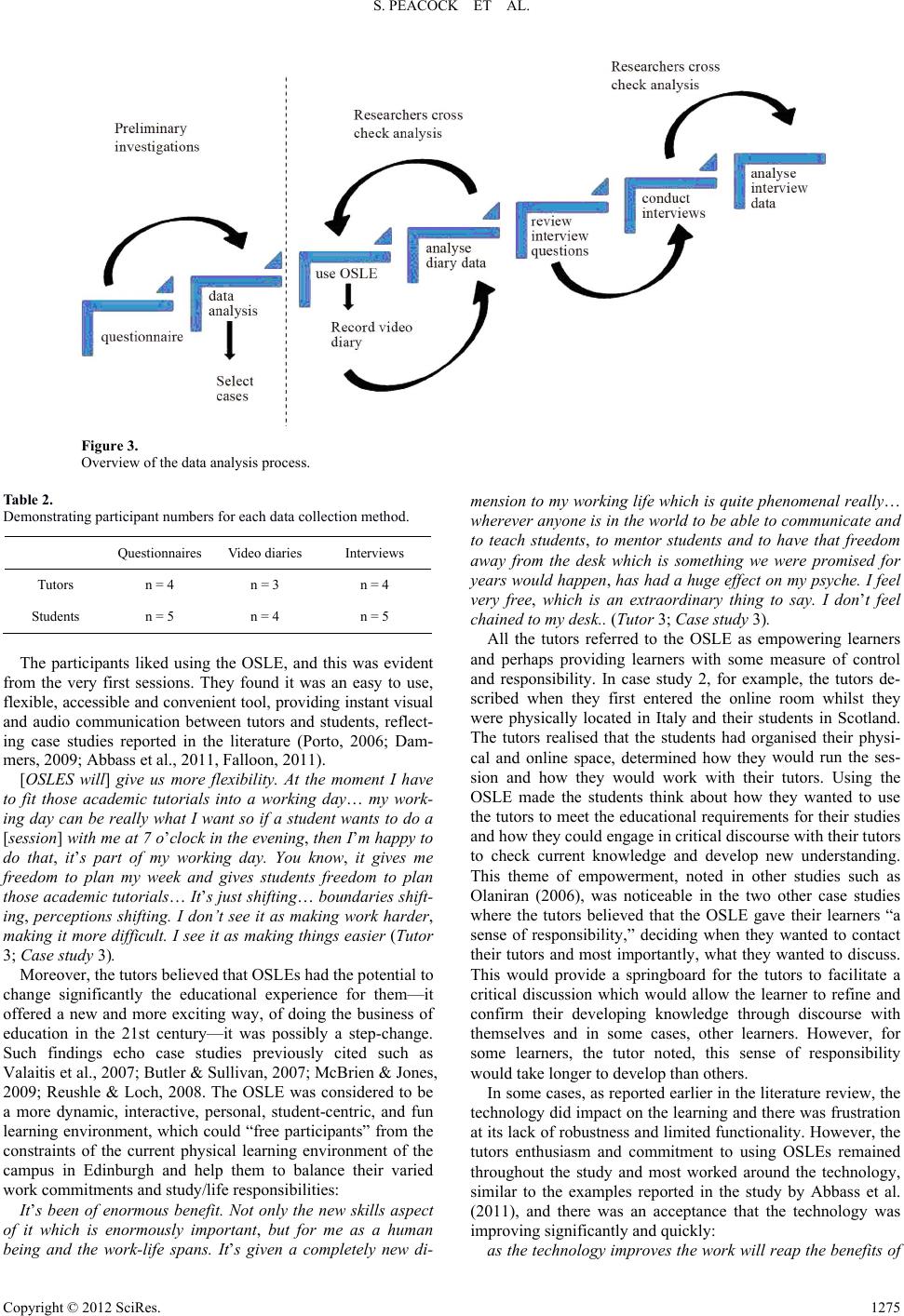

|